- Daily Crossword

- Word Puzzle

- Word Finder

- Word of the Day

- Synonym of the Day

- Word of the Year

- Language stories

- All featured

- Gender and sexuality

- All pop culture

- Writing hub

- Grammar essentials

- Commonly confused

- All writing tips

- Pop culture

- Writing tips

Advertisement

noun as in consequence, effect

Strongest matches

conclusion , event , fallout , issue , reaction , result

Strong matches

aftereffect , aftermath , end , payback , payoff , score , sequel , upshot

Weak matches

blowoff , causatum , chain reaction , end result

Discover More

Example sentences.

Cassandra, whose hair has already begun to fall out from her court-mandated chemotherapy, could face a similar outcome.

The possibility that the same outcome could happen another way -- namely a guy asks me out -- keeps me from taking action.

In Rome, he writes, the chicken “predicted the outcome of battles.”

We stand by our filmmakers and their right to free expression and are extremely disappointed by this outcome.

The outcome of the rum feud is critical for both Bacardi and Pernod Ricard, because the winner could net billions in future sales.

The poverty of earlier days was the outcome of the insufficiency of human labor to meet the primal needs of human kind.

The vision itself is an outcome of that divine discontent which raises man above his environment.

This, thought I, is a dismal-looking outcome—two men and a dead horse left high and dry on the sun-flooded prairie.

The outcome of the wrangle was a purely personal accommodation of an essentially momentary character.

They had awaited the outcome of the Sands-Chester transaction rather from curiosity than any doubt as to the result.

Related Words

Words related to outcome are not direct synonyms, but are associated with the word outcome . Browse related words to learn more about word associations.

noun as in situation following an event, occurrence

- after-effects

- chain reaction

- consequences

- eventuality

noun as in fate, luck

- coincidence

- contingency

- destination

- even chance

- heads or tails

- in the cards

- lucky break

- peradventure

- stroke of luck

- throw of the dice

- turn of the cards

- way the cookie crumbles

- wheel of fortune

noun as in end

- consequence

- culmination

- development

- end of the line

- termination

noun as in tally; number

- calculation

- computation

- enumeration

noun as in conclusion; resolution reached

- accommodation

- adjudication

- adjudicature

- arbitration

- arrangement

- declaration

- determination

- prearrangement

- reconciliation

- understanding

Viewing 5 / 41 related words

On this page you'll find 64 synonyms, antonyms, and words related to outcome, such as: conclusion, event, fallout, issue, reaction, and result.

From Roget's 21st Century Thesaurus, Third Edition Copyright © 2013 by the Philip Lief Group.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 27 July 2021

Conceptualizing the elements of research impact: towards semantic standards

- Brian Belcher ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7356-745X 1 , 2 &

- Janet Halliwell ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4224-9379 3

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 8 , Article number: 183 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

7302 Accesses

10 Citations

10 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Complex networks

- Development studies

- Science, technology and society

Any effort to understand, evaluate, and improve the impact of research must begin with clear concepts and definitions. Currently, key terms to describe research results are used ambiguously, and the most common definitions for these terms are fundamentally flawed. This hinders research design, evaluation, learning, and accountability. Specifically, the terms outcome and impact are often defined and distinguished from one another using relative characteristics, such as the degree, directness, scale, or duration of change. It is proposed instead to define these terms by the kind of change rather than by the degree or temporal nature of change. Research contributions to a change process are modeled as a series of causally inter-related steps in a results chain or results web with three main kinds of results: (i) the direct products of research, referred to as outputs; (ii) changes in the agency and actions of system actors when they are informed/influenced by research outputs, referred to as outcomes; and (iii) tangible changes in the social, economic, environmental, or other physical condition, referred to as realized benefits. Complete definitions for these terms are provided, along with examples. This classification aims to help focus research evaluation appropriately and enhance appreciation of the multiple pathways and mechanisms by which scholarship contributes to change.

Introduction

There are high expectations from the public, research funding agencies, and researchers themselves to contribute to and document impact resulting from their research (Bornmann, 2012 ; Edler et al., 2012 ; Wilsdon et al., 2015 ). Any effort to understand, evaluate, and improve the impact of research must begin with clear concepts and definitions. Currently there is a debilitating lack of clarity and consistency in the use of key terms that describe the results of any intervention, including changes engendered by research. The terms output, outcome, and impact, which are terms used in a typical logic model, are used ambiguously and the most common definitions for these terms are fundamentally flawed (Belcher and Palenberg, 2018 ). This hinders evaluation, learning, and accountability in academic research as much or more than in any other field. This essay, based on the authors’ experience with conceptualizing and assessing research impact in the social sciences and humanities, applied research, and research-for-development contexts, takes a systems perspective on research impact and offers precise sub-categories of impact to improve clarity.

Established concepts used in research evaluation such as “impact factor” and “high impact research” refer to measures of publication and citations of research, but do not measure actual use or value beyond the academic realm (DORA, 2012 ; Hicks et al., 2015 ). There has been increasing attention to the non-academic impacts of research (Bornmann, 2012 ; Oancea, 2019 ; Williams, 2020 ). Alla et al. ( 2017 ) conducted a systematic review of definitions of research impact, finding 108 definitions in 83 publications. However, they noted a dominance of what they called bureaucratic definitions and a widespread failure to actually define the term explicitly. The most highly cited definitions were those of the Research Excellence Framework (“an effect on, change or benefit to the economy, society, culture, public policy or services, health, the environment or quality of life, beyond academia” (REF, 2011 , p. 26)), the Research Councils of the UK (“the demonstrable contribution that excellent research makes to society and the economy” (Economic and Social Research Council, 2021 , para.1)), and the Australian Engagement and Impact Assessment framework (“the contribution that research makes to the economy, society, environment or culture, beyond the contribution to academic research” (Australian Research Council, 2018 , p. 5)). While these broad, all-encompassing concepts give attention to societal benefits beyond academia, they all lack precision and require further classification to be useful analytically. They also fail to recognize that research typically contributes to change within complex social, economic, technical, and environmental systems, in conjunction with many other factors. Based on their review, Alla et al. ( 2017 ) re-emphasize the need for conceptual clarity, while offering their own definition specific to the mental health field: “Research impact is a direct or indirect contribution of research processes or outputs that have informed (or resulted in) development of new (mental) health policy/practices, or revisions of existing (mental) health policy/practices, at various levels of governance (international, national, state, local, organizational, health unit)” (p. 9).

Gow and Redwood ( 2020 ) also give considerable attention to the lack of clarity in interpretation of impact. They devote a chapter to discuss impact terminology and suggest a four-part impact typology: Instrumental; Conceptual; Capacity Building, and Procedural. They do not provide precise definitions for these sub-components of impact, and the authors themselves note that the categories are not mutually exclusive.

The term outcome is also widely used to refer to a step in a results chain. Like impact, outcome is also used ambiguously to refer to everything from the products of research to intermediate and shorter-duration changes stimulated by research, and it is often used as a synonym for impact. Most results chains conceptualize outcomes as resulting from outputs and as precursors to impact. The terms outcome and impact are typically distinguished from one another relatively, based on the degree, directness, scale, or duration of change. For example, the influential OECD ( 2010 ) glossary of evaluation terms defined outcomes as “The likely or achieved short-term and medium-term effects of an intervention’s outputs” (p. 28) and impacts as “Positive and negative, primary and secondary long-term effects produced by a development intervention, directly or indirectly, intended or unintended” (p. 24). As Belcher and Palenberg ( 2018 ) discuss in detail, these definitions do not support clear, unambiguous distinctions between the terms or the concepts they are intended to define. Of particular relevance is the fact that the temporal dimension of these definitions is not helpful for analytical purposes such as research design, evaluation, learning, and accountability.

All the above impact definitions refer to a ‘contribution’ made by research, but devote most of their attention to the locus of change (i.e., beyond academia). They offer little to help specify, understand, or analyze the nature of the contribution research makes, or to ascertain definitively what is included and what is excluded in the definition. To help clarify the concept and advance thinking about research impact, we therefore propose two more precise sub-categories of impact that are defined absolutely, by the kind of change, rather than relatively, by the degree or temporal nature of change. We recognize that change processes happen in complex systems. Research contributes to a change process within a system and can be modeled as a series of causally inter-related steps in a results chain or results web. There are three main kinds of results from research: (i) the products and services of research, produced directly by a research program, which we refer to as outputs; (ii) changes in the agency of other actors when they use and/or are influenced by research outputs, which we refer to as outcomes; and (iii) tangible changes in the social, economic, environmental, or other physical condition, which we refer to as realized benefits. Complete definitions for these terms are provided below, along with examples. This is a classification of the types of contributions of research and scholarship within a theory of change, not a hierarchy of value.

Societal demands for impact naturally focus on positive changes in social, economic, environmental, or other physical condition. Research is supported with the expectation that it will contribute in some way to improvements in human well-being and environmental conditions. In the development field, the term impact is often used to mean mission-level impact (i.e., changes in social, economic, environmental, and/or physical condition) (Belcher and Palenberg, 2018 ). However, the term impact is used commonly and ambiguously in standard English language, and in the academic realm it has both a particular meaning (often measured by citations) and a general meaning that includes what we have called outcomes as well as realized benefits (and costs), as exemplified by the definitions cited above. The term is so imprecise in its common usage, and so loaded with pre-existing definitions, that it would be difficult to re-define. We have therefore elected not to propose a new or restricted definition of the term impact. Rather, we are proposing a classification of sub-categories of impact, which are based on the nature of the change. We use “impact” as an overarching term to denote any change caused in whole or in part by an action or set of actions, including research actions.

Proposed definitions

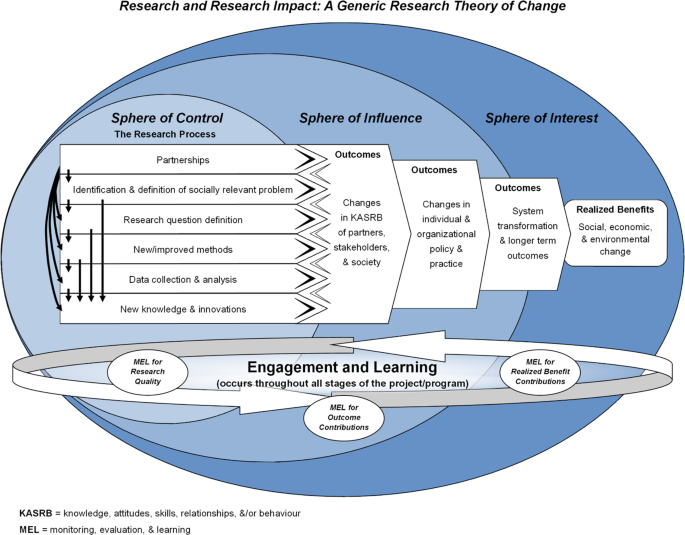

Knowledge, including new insights, technical innovations, institutional models, and other direct products and services produced by a research program. Outputs are produced by actions within a program’s (including partners) sphere of control (see Fig. 1 ).

Examples of outputs include: new research methods, data sets, analyses, discoveries, histories, new theories, policy analyses or recommendations, and artistic performances. Outputs may also include processes such as discussion fora, networking, or capacity building done as part of a research process.

Outputs are the actual knowledge, innovations, and services produced by research as well as the media that communicate knowledge and innovation, such as books, journal publications, policy briefs, or patents.

A change in knowledge, attitudes, skills, and/or relationships (KASR), ideally manifest as a change in behavior (B), that results in whole or in part from the research process and its outputs. Outcomes may be at the individual, group, organizational, or higher scales.

Outcomes occur in actors beyond the research boundary; that is, outside the sphere of control and within the spheres of influence and interest.

By this definition, a change in an individual, group, or organization’s KASR is an outcome.

If a change in KASR leads to an action or set of actions (a change in behavior Footnote 1 ) by an actor in the system, that action may in turn contribute to changes in other actors’ KASR and behavior. Such downstream changes are also defined as outcomes. A change in KASR is an outcome by this definition, but it can only contribute to further change if it leads to some action.

In research evaluation, outcomes can be disaggregated into academic outcomes , which refers to influences and changes within the academic realm, and societal outcomes , which refers to changes outside the academic realm.

Examples of academic outcomes include adoption and use of new methods, replication of studies, use of data sets, or use of new theories by other researchers.

Examples of societal outcomes include changes Footnote 2 in understanding of risk or vulnerabilities; changes in public understanding, values, and attitudes; adoption of new technologies or organizational practices; licensing of patents; new partnerships with community groups; skills and capabilities inculcated through the research experience; shared knowledge and public discourse; new policy or regulations; or creation of a social enterprise.

Realized benefits

A change in economic, social, or environmental condition resulting in whole or in part from a chain of events to which research has contributed. This can manifest as a change in flow or change in state. Benefits/costs may be realized at individual, group, organizational, or higher scales.

Realizing tangible social, economic, and/or environmental benefits often Footnote 3 involves actors outside the program’s/researcher’s sphere of influence and is the ultimate stage of a complex pathway and change process to which the research has contributed.

Examples of realized benefits include: changes in income (flow) or wealth (state), changes in the level of press freedom (state), changes in carbon emissions (flow) or water quality (state), changes in levels of experienced racism, or changes in a person’s or a community’s mental health status.

Realized benefits may be positive or negative in the same way an investment can yield a negative return; that is, the change process to which research contributes may have negative or harmful social, economic, and/or environmental consequences for some or all stakeholders. Such negative consequences are sometimes termed “grimpacts” (Derrick et al., 2018 , p. 1199).

Research outputs, outcomes, and realized benefits in a theory of change

Figure 1 illustrates a research program Footnote 4 theory of change. The three spheres reflect the fact that the relative influence of any intervention declines as interactions with other actors and processes increase (Hearn, 2010 ; Montague, 2000 ). The program has a high level of control over program activities and outputs in the sphere of control. Beyond the program boundary, research outputs inform, influence, and support other actors and their actions (outcomes), alongside many other influences and processes, in the sphere of influence. Ideally, the actions of those other actors will then contribute to realized benefits in the sphere of interest.

Generic research theory of change.

In practical terms, the sphere of control includes actions and outputs that can be produced directly by the researcher or research team. This includes actions and outputs produced by collaborators as part of their commitments to a program. If an actor must be persuaded through the provision of knowledge, tools, or advocacy, this change occurs in the sphere of influence. The concept of the sphere of influence attempts to capture the idea that change happens when the KASR of other actors (i.e., not part of the research team) change. These kinds of changes are classified as outcomes of the research if they result in whole or, more likely, in part from the research process and/or output(s). If there are co-produced outputs, it implies that the research process has resulted in KASR and behavior in other actors that would not have happened in the absence of the research, and this change is an outcome. Individually or collectively, changes in behavior that result in part or in whole from the research can lead to realized benefits.

The research program itself is represented in Fig. 1 as a stylized sequence of activities, from top to bottom, within the sphere of control. Activities include developing partnerships with other researchers and/or societal actors and (co-)defining the problem the research will address and the specific questions it seeks to answer. The research then may apply established methods and/or develop new methods to collect and analyze data and (co)create new knowledge and innovations. This list is indicative; not all steps may be present and\or they may occur in different sequence, iteratively, and with or without external actors being involved.

The program’s interactions with and influence in society is represented horizontally, from the sphere of control (program implementation), through the sphere of influence (other actors informed and influenced by research outputs), to the sphere of interest (the tangible benefits to which the research may contribute). The figure tries to represent the dynamic interactions in a complex system. The downward arrows in the sphere of control indicate that each step in the research process contributes to other actions in the research process.

In traditional academic research, the primary aim has been to create new knowledge, search for meaning, and improve understanding. However, research can contribute to outcomes and realized benefits in many ways. Moving from the left to right in the diagram (as indicated by the rightward arrows), each of the individual steps in the research process can produce outputs that contribute independently as well as in combination. For example, the process of developing a partnership may build relationships among stakeholders that have value beyond the program; the research question and/or new methods could stimulate attention and additional research on an important topic; open data policies are increasing the likelihood that data sets will be made available for other uses beyond a program. Each of the steps can contribute to changes in KASR and changes in behavior (B) by other actors. The research process may also be informed and influenced by societal engagement, as represented by the leftward arrows moving from partners, stakeholders, and society back to the program.

The rightward arrow to the second step within the sphere of influence illustrates how changes in KASRB (outcomes) among partners, stakeholders, and society more generally can lead to changes in policy and practice (outcomes) and higher-level system transformations (outcomes), that ultimately lead to changes in social, economic, or environmental condition (realized benefits) in the sphere of interest. This highlights the important role of collaborations and partnerships in co-creating and advancing the use the research-based knowledge and reflects an important rationale for increased use of engaged transdisciplinary research approaches. The circular arrow at the bottom of the diagram represents ongoing stakeholder engagement throughout all stages.

Finally, the figure indicates that the focus of monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) is different at each stage in the impact pathway. Within the sphere of control, the focus is on research quality, broadly defined to include considerations of relevance, credibility, legitimacy, and how research is positioned for use (Belcher et al., 2016 ; Ofir et al., 2016 ). Is the research focus, design, and implementation appropriate and sound? Within the sphere of influence, research evaluation needs to focus on whether and how research has contributed to outcomes. Is there evidence that the research has stimulated or contributed to changes in KASRB, and is it reasonable to expect further knock-on changes? In the sphere of interest, the focus is on the scale and scope of realized benefits and analysis of the relative contribution of research.

It is important to emphasize that this is a classification, not a hierarchy of value. It is intended to support research evaluation by distinguishing the kinds of changes that research can enable, catalyze, and contribute to. In order to assess what difference research makes, we need to know what kind of change we are looking for. Change happens in complex systems and, as illustrated in Fig. 1 , most change happens outside the control of a research program. The kind and degree of change to which any research program contributes and the timeframe over which that change happens will depend on many other factors, including the nature of the issue, the current state of knowledge, and the political climate. In some domains of research (e.g., many Engineering and Applied Sciences), external stakeholders often have close linkages with researchers, such that the pathway through the spheres of influence and interest to realized benefits can be relatively direct and rapid. In Health research, the interface of researchers with individuals with lived experience of a disease provides engagement and learning, and enables more effective translation of research outputs to practice and realized benefits of the affected communities. The outputs of scholarship in Social Sciences and the Humanities may profoundly influence understanding, appreciation, values, and indeed the actions of individuals, organizations, or society more generally (i.e., outcomes). These kinds of changes are often difficult to observe, difficult to measure, and difficult to attribute, and occur over long timeframes, but have value in and of themselves. They may also contribute to realized benefits, but in most cases the attribution challenges are insurmountable because there are so many other causal factors. This classification aims to help focus research evaluation appropriately and enhance appreciation of contributions that scholarship makes to change in more diffuse ways. In any research evaluation, we need to look at outcomes as the primary indicator of research effectiveness.

There has been a great deal of discussion in the literature about research impact, how to define it, and how to measure it, but current definitions and usage remain vague and ambiguous. This essay combines two main ideas to help achieve conceptual clarity. First, we explicitly recognize that research contributes to change within systems as sequential causal processes (with feedback and iteration), in combination with other processes and other actors. We have provided a generic model of a research-to-impact process that: illustrates the declining relative influence of an intervention in a system, shown as spheres of control, influence, and interest; indicates typical actions within a research process; appreciates that individual actions in the research process may make valuable contributions independently as well as in combination, especially in engaged co-produced research; and identifies that the focus of monitoring, evaluation, and learning is different at each stage in the process. Second, we propose that it is practical and useful to classify research results into different kinds. Outputs are the products and services produced directly by research. Outcomes are the changes in KASR experienced by other actors who have been influenced by the outputs of research. Those changes in KASR may also contribute to changes in behavior and, thereby, to subsequent outcomes. Realized benefits are tangible changes in the social, economic, environmental, or other physical conditions. In this framing, research impact includes both outcomes and realized benefits. This classification aims to help focus research evaluation appropriately and enhance appreciation of the multiple pathways and mechanisms by which scholarship contributes to change.

Change in behavior is understood broadly. It is any action that would not otherwise have taken place. It could be something as simple as one person telling another what they have learned, to transformative changes in individual, organizational, institutional, or societal policies or practices. We are asking “Who does what differently as a result of the research?”

Change is assessed against a (hypothetical) counterfactual; i.e., what would have happened in the absence of the intervention. Thus, the change may be a decision to maintain the status quo or to avoid implementing a program.

In some types of research, such as participatory action research, benefits may be realized by participants.

We use the term “program” to refer to a body of research work done by an individual researcher or a team of researchers. The discussion could equally refer to a “project”.

Alla K, Hall WD, Whiteford HA, Head BW, Meurk CS (2017) How do we define the policy impact of public health research? A systematic review. Health Res Pol Syst 15(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-017-0247-z

Article Google Scholar

Australian Research Council (2018) Engagement and Impact EI 2018 Assessment Handbook. https://www.arc.gov.au/engagement-and-impact-assessment/ei-key-documents

Belcher BM, Rasmussen KE, Kemshaw MR, Zornes DA (2016) Defining and assessing research quality in a transdisciplinary context. Res Eval 25(1):1–17. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvv025

Belcher B, Palenberg M (2018) Outcomes and impacts of development interventions: toward conceptual clarity. Am J Eval 39(4):478–495. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214018765698

Bornmann L (2012) Measuring the societal impact of research: research is less and less assessed on scientific impact alone—we should aim to quantify the increasingly important contributions of science to society. EMBO Rep 13(8):673–676. https://doi.org/10.1038/embor.2012.99

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Derrick GE, Faria R, Benneworth P, Budtz-Petersen D, Sivertsen G (2018) Towards characterising negative impact: Introducing Grimpact. Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Science and Technology Indicators 2018, Leiden, The Netherlands. https://research.utwente.nl/files/57761417/STI2018_paper_201.pdf

DORA (2012) The San Francisco Declaration Research Assessment. https://sfdora.org/read/

Economic and Social Research Council (2021) What is impact?. https://esrc.ukri.org/research/impact-toolkit/what-is-impact/

Edler J, Georghiou L, Blind K, Uyarra E (2012) Evaluating the demand side: new challenges for evaluation. Res Eval 21(1):33–47. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvr002

Gow J, Redwood H (2020) Impact in international affairs: the quest for world-leading research (1st edn.). Routledge

Hearn S (2010) Outcome mapping: planning, monitoring and evaluation. Outcome mapping learning community. https://www.slideshare.net/sihearn/introduction-to-outcome-mapping

Hicks D, Wouters P, Waltman L, De Rijcke S, Rafols I (2015) Bibliometrics: the Leiden Manifesto for research metrics. Nat News 520(7548):429–431. https://doi.org/10.1038/520429a

Montague S. (2000) Circles of influence: an approach to structured, succinct strategy. http://www.pmn.net/wp-content/uploads/Circles-of-Influence.pdf

Oancea A (2019) Research governance and the future(s) of research assessment. Palgrave Commun 5(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-018-0213-6

OECD-DAC (2010) Glossary of key terms in evaluation and results based management. https://www.oecd.org/dac/evaluation/2754804.pdf

Ofir Z, Schwandt T, Duggan C, McLean R (2016) RQ+ research quality plus: a holistic approach to evaluating research. https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/bitstream/handle/10625/56528/IDL-56528.pdf?sequence=2

REF (2011) Assessment framework and guidance on submissions. Bristol, United Kingdom. https://www.ref.ac.uk/2014/media/ref/content/pub/assessmentframeworkandguidanceonsubmissions/GOS%20including%20addendum.pdf

Williams K (2020) Playing the fields: theorizing research impact and its assessment. Res Eval 29(2):191–202. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvaa001

Wilsdon J, Allen L, Belfiore E, Campbell P, Curry S, Hill S, Jones R, Kain R, Kerridge S, Thelwall M, Tinkler J, Viney I, Wouters P, Hill J, Johnson B (2015) The metric tide: report of the independent review of the role of metrics in research assessment and management. Sage Publications, London

Download references

Acknowledgements

For their sponsorship of a 2019 workshop by the Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences and CASRAI, as well as their valuable comments and feedback at various stages in the development of this article, the authors would like to acknowledge Suzanne Board, Laura Beaupre, Yolande Chan, Kyle Demes, Heather Frost, Laura Hillier, Sandra Lapointe, Sharon Murphy, Nilgun Onder, Emile Paquin, David Phipps, Sally Rutherford, Lisa Shapiro, Karine Souffez, Louise Michelle Verrier, and David Watt. We are also indebted to Anna Hatch for her insightful comments on an earlier draft of this article. Brian Belcher’s work on this has been supported by the Canada Research Chairs Programme, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC), Ashoka Canada, and the Forests, Trees and Agroforestry Consortium Research Program.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Royal Roads University, Victoria, BC, Canada

Brian Belcher

Center for International Forestry Research, P.O. Box 0113, BOCBD, Bogor, Indonesia

J. E. Halliwell Associates Inc, Saltspring Island, BC, Canada

Janet Halliwell

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Brian Belcher .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Belcher, B., Halliwell, J. Conceptualizing the elements of research impact: towards semantic standards. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8 , 183 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00854-2

Download citation

Received : 21 December 2020

Accepted : 30 June 2021

Published : 27 July 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00854-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Synonyms and antonyms of outcome in English

- THE RESULT OF SOMETHING

Synonyms and examples

Outcome | american thesaurus.

Word of the Day

customer support

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

help and advice that a company makes available to customers when they have bought something

Varied and diverse (Talking about differences, Part 1)

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

To add ${headword} to a word list please sign up or log in.

Add ${headword} to one of your lists below, or create a new one.

{{message}}

Something went wrong.

There was a problem sending your report.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Zhejiang Univ Sci B

- v.14(8); 2013 Aug

Outcomes research: science and action

Henry h. ting.

1 Division of Cardiovascular Diseases, Knowledge and Evaluation Research Unit, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota 55905, USA

Mei-xiang Xiang

2 Cardiovascular Key Lab of Zhejiang Province, Department of Cardiology, the Second Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310009, China

Jian-an Wang

Outcomes research, which investigates the outcomes of health care practices, is intended to provide scientific evidence for clinical decision making and health care. This paper elucidates the goal and domains of outcomes research. Also it shows the potential and promise of outcomes research to provide a methodology to uncover what to do and how to do it, and enable the health care profession to achieve the right care, for the right patient, at the right time, the first time, every time, nothing more, and nothing less.

1. Clinical case

A 56 year-old male smoker presented to a hospital emergency department, having suffered 3 h of severe chest pain. Physical exam showed a heart rate of 90 beats/min, blood pressure of 90/60 mmHg, and bibasilar rales. An electrocardiogram performed within 10 min of arrival demonstrated a 2-mm ST-elevation in leads V 1 –V 4 (Fig. (Fig.1). 1 ). The patient was treated with 325 mg of aspirin, 600 mg of clopidogrel, and 4 000 U of heparin, and underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention using right radial artery access. Following aspiration thrombectomy, a drug-eluting stent was placed in the left anterior descending artery, restoring normal blood flow. The door-to-balloon time was 70 min. Echocardiography showed a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction of 60% with only mild anterior-apical hypokinesis. He was started on 50 mg of metoprolol twice daily, 40 mg of atorvastatin daily, 81 mg of aspirin daily, and 75 mg of clopidogrel daily, and discharged from hospital on Day 3. Was this high-quality patient care?

Clinical case of electrocardiogram and angiogram

The care provided in the emergency department, cardiac catheterization lab, and coronary care unit was appropriate and excellent. However, despite rapid diagnosis and treatment for this patient with ST-elevation myocardial infarction, what were the long-term patient outcomes at 30 d, 6 months, and 1 year? While long-term survival free from recurrent major adverse cardiovascular events depends on the door-to-balloon time and type of drug-eluting stent, it also depends on the patient’s ability to adhere to medication schedules, to follow up with his or her physician, to change his lifestyle, including smoking cessation, diet, and exercise, and to access and pay for health care services and secondary prevention.

2. Opportunity to improve health care

The United States health care system’s costs are the highest in the world, but quality and patient outcomes lag behind those of other countries. Furthermore, the United States health care is characterized by striking gaps (McGlynn et al., 2003 ; Pham et al., 2007 ) including: (1) variation in care across health care systems and among clinicians, (2) fragmentation of care, (3) disparities in access and patient outcomes, (4) marginal safety, and (5) unsustainable rises in costs. These forces contribute to observed adverse outcomes such as preventable deaths, re-admissions, and hospital acquired infections. Some experts contend that the United States health care system faces a hard choice—either to cut costs or to sacrifice quality. This is a false choice and there is a third option—to design, implement, and evaluate systems of care that simultaneously improve outcomes and reduce costs.

In the 20th century, clinicians saved lives by inventing new and more effective medications, performing open heart surgery, and treating heart attack patients with stents. In the 21st century, clinicians will save lives by improving coordination of care, enhancing communication and teamwork, engaging patients and families in shared decision making, and embracing a culture of change and continuous improvement. Fatalism is leaving health care as events which once appeared beyond our control, like medication errors and patient falls, are coming within our influence—but only if we act together as an interprofessional team.

Health care organizations across the world are rapidly transforming to achieve the triple aims of better patient care and health care experience, better population health, and more affordable care. Stakeholders in health care, including patients, payers, and policymakers, expect clinicians and organizations to achieve all three aims simultaneously, and not only one or two of them. Recently, 11 chief executive officers of leading United States health care systems proposed a “Checklist for High Value Health Care” consisting of 10 key strategies to improve outcomes and reduce costs simultaneously (Cosgrove et al., 2013 ): (1) leadership with visible priorities; (2) culture of continuous improvement and learning; (3) information technology best practices at point of care; (4) use of evidence-based protocols; (5) optimized use of resources (personnel, space, and equipment); (6) integrated care; (7) shared decision making; (8) targeted service lines for resource intensive patients; (9) embedded safeguards to prevent injury and harm; (10) internal transparency of performance, outcomes, and costs.

How will clinicians and health care organizations achieve these goals in a manner harmonized with the Institute of Medicine’s domains of quality (Ferguson, 2012 )—care that is safe, timely, effective, efficient, equitable, and patient-centered? How will clinical research inform clinicians and health care organizations about what to do and how to do it?

3. Goals of outcomes research

Outcomes research holds the potential and promise to help transform health care delivery and patient outcomes by focusing on the “end results or outcomes” of health care. Health care can be characterized and measured by attributes including structure, processes, and outcomes. Structural attributes are features of health care organizations or clinicians, related to their capacity to provide high quality care, such as electronic medical records, computerized physician order entry, or nurse-to-patient staffing ratios. Process measures are health care related activities performed for, on behalf of, or by a patient, such as prescribing statins at discharge for patients with acute myocardial infarction or door-to-balloon time for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Intermediate clinical outcome measures are changes in physiologic state that lead to a long-term health outcome, such as low-density lipoprotein levels or adherence to prescribed medications. Health outcome measures represent the health status of a patient resulting from care (including either desirable or adverse outcomes), such as 30-d mortality rates and 30-d hospital re-admission rates.

Outcomes research focuses on understanding and improving intermediate clinical outcomes and health outcomes through better information, better clinical decision making, and better health care delivery. It is a new scientific field developed in the last decade and draws from clinical medicine, statistics, informatics, epidemiology, social sciences, real-world practice, improvement science, implementation science, and policy (Krumholz, 2011 ). Outcomes research, positioned at the interface of these disciplines, is an inherently practical form of clinical research that not only describes gaps in health care outcomes but also strives to find solutions to resolve those gaps (Ting et al., 2009 ).

4. Domains of outcomes research

Outcomes research consists of four domains of activities: surveillance, discovery, translation, and dissemination (Fig. (Fig.2). 2 ). Surveillance research addresses the question: How are we doing? Surveillance is a necessary and critical first step to understand what gaps exist in our current health care delivery system, either at the local, regional, national, or international level. Surveillance starts with an environmental scan of what care is actually delivered, rather than what care should be delivered according to clinical practice guidelines. For example, in a study of 12 cities in the United States, McGlynn et al. ( 2003 ) showed that on average only 55% of patients received treatments recommended by clinical practice guidelines, ranging from 68% of patients with coronary artery disease to 25% of patients with atrial fibrillation who received ideal, recommended care. Clinical databases and registries, payer claims and financial databases, and survey studies are alternative approaches to collect and analyze data to understand better the gap between usual, routine clinical care and ideal, recommended clinical care.

Outcomes research—types of activities

Discovery research addresses the questions: What new approaches can be learned and what works, for whom, and in what context? After illuminating the gaps in clinical care and patient outcomes, discovery research endeavors to find new ways to organize and deliver care that can resolve those gaps. There are three general approaches for discovery research, including multivariable statistical modeling, action-oriented quality improvement, and mixed-methodology positive deviance. Multivariable statistical modeling research determines which characteristics of hospitals or patients are associated with patient outcomes. One example is the development and validation of risk prediction scores to identify which patients, after percutaneous coronary intervention, are at low (<1%), intermediate (1%–3%), and high (>3%) risk for major bleeding events (Mehta et al., 2009 ). Action-oriented quality improvement research represents a single organization or work unit internally developing, implementing, and testing interventions to improve patient outcomes. These interventions and best practices are typically informed by a small sample of experts and often may not be applicable to other contexts. For example, a quality improvement team strived to reduce hospital acquired infections by trying interventions such as hand hygiene and disinfection of surfaces with bleach (Orenstein et al., 2011 ). Mixed-methodology positive deviance research aims to identify existing top performing organizations and to understand how they are delivering care. This approach requires the following: performance measures that are valid, widely accepted, available, and accessible; a range and distribution in performance where top performers can be reliably identified; top performers that are willing to share best practices and a learning network that can be developed; and qualitative and quantitative methods that can be reliably used (Bradley et al., 2009 ). For example, novel interventions to improve door-to-balloon time for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction in the United States were developed using positive deviance research. These interventions included enabling the emergency department physician to activate the cardiac catheterization lab team and providing real-time feedback of performance to emergency department cardiac catheterization lab staff (Bradley et al., 2006 ).

Translation research addresses the question: How can we best apply proven interventions to clinical practice? Translation focuses on the practical issues of what are the facilitators and barriers for hospitals and clinicians to adopt novel interventions and methods to provide care. For example, in the United States, it took 25 years and 6 weeks from the discovery that β-blockers improve survival after myocardial infarction in the β-Blocker Heart Attack Trial (BHAT) to achieve the performance standard that 90% of patients after acute myocardial infarction are discharged from the hospital on a β-blocker (Lee, 2007 ). This lag in translation is not related to unintelligent or forgetful clinicians. Rather, it relates to systems and processes of care to ensure that the best care is provided to every patient, every day. Further, decades of research have shown that in the current era, translation typically occurs passively, much like diffusion; if the goal was to accelerate the speed of translation, then it must be actively managed. Recently, federal funding agencies in the United States have begun to prioritize grants for translational research (Westfall et al., 2007 ).

Dissemination addresses the question: How to spread what works for one hospital or practice context to other hospitals. Dissemination research utilizes the REAIM (reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, maintenance) framework of reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance. Reach measures how broadly the intervention is used by participants. Effectiveness refers to the impact of the intervention on patient outcomes. Adoption assesses how easy it is for participants to understand and implement the intervention within their practice context and clinical workflow. Implementation evaluates the facilitators and barriers to implement the intervention, and the correspondence between what was planned and what was achieved. Maintenance measures whether the intervention has become a usual, routine activity, and whether continuous monitoring of outcomes exists. Dissemination research requires developing learning networks to engage stakeholders and beneficiaries broadly. For example, the Door-to-Balloon Alliance for Quality spread interventions to improve door-to-balloon time to over 1 200 hospitals in the United States through a learning network (Krumholz et al., 2008 ).

5. Conclusions

Health care is on the cusp of extraordinary changes to achieve the triple aims of better patient care and health care experience, better population health, and more affordable care. To realize the societal expectation for high value health care, outcomes research represents a scientific field of study to illuminate the gaps in care, discover interventions that can close those gaps, translate proven interventions to specific clinical teams and practice contexts, and spread what works across a region or nation. Outcomes research has the potential and promise to provide a methodology to uncover what to do and how to do it, and enable the health care profession to achieve the right care, for the right patient, at the right time, the first time, every time, nothing more, and nothing less.

Compliance with ethics guidelines: Henry H. TING, Mei-xiang XIANG, and Jian-an WANG declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Synonyms of 'outcome' in British English

Additional synonyms, synonyms of 'outcome' in american english.

Browse alphabetically outcome

- All ENGLISH synonyms that begin with 'O'

Quick word challenge

Quiz Review

Score: 0 / 5

Wordle Helper

Scrabble Tools

Related Words and Phrases

Bottom_desktop desktop:[300x250].

Synonyms of results

- as in outcomes

- as in answers

- as in works

- as in turns out

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Thesaurus Definition of results

(Entry 1 of 2)

Synonyms & Similar Words

- consequences

- developments

- conclusions

- implications

- matters of course

- aftereffects

- precipitates

- corollaries

- ramifications

- repercussions

- denouements

- side effects

- side reactions

- dénouements

- by - products

- aftershocks

- spin - offs

Antonyms & Near Antonyms

- antecedents

- considerations

- determinants

- foundations

- inspirations

- instigations

- groundworks

- explanations

- determinations

Thesaurus Definition of results (Entry 2 of 2)

- springs (up)

- shapes (up)

- materializes

- comes about

Thesaurus Entries Near results

resulting (in)

results (in)

Cite this Entry

“Results.” Merriam-Webster.com Thesaurus , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/thesaurus/results. Accessed 15 May. 2024.

More from Merriam-Webster on results

Nglish: Translation of results for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of results for Arabic Speakers

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

More commonly misspelled words, your vs. you're: how to use them correctly, every letter is silent, sometimes: a-z list of examples, more commonly mispronounced words, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), popular in wordplay, the words of the week - may 10, a great big list of bread words, 10 scrabble words without any vowels, 8 uncommon words related to love, 9 superb owl words, games & quizzes.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Synonyms for Research Outcome (other words and phrases for Research Outcome). Synonyms for Research outcome. 19 other terms for research outcome- words and phrases with similar meaning. Lists. synonyms. antonyms. definitions. sentences. thesaurus. suggest new. scientific end. study effect. academic consequence.

Synonyms for OUTCOME: result, resultant, consequence, product, effect, aftermath, matter of course, fate; Antonyms of OUTCOME: cause, reason, consideration, factor ...

Find 23 different ways to say OUTCOME, along with antonyms, related words, and example sentences at Thesaurus.com.

Figure 1 illustrates a research program Footnote 4 theory of change. The three spheres reflect the fact that the relative influence of any intervention declines as interactions with other actors ...

Typical examples of outcomes are cure, clinical worsening, and mortality. The primary outcome is the variable that is the most relevant to answer the research question. Ideally, it should be patient-centered (i.e., an outcome that matters to patients, such as quality of life and survival). Secondary outcomes are additional outcomes monitored to ...

Synonyms for OUTCOME: result, consequence, issue, effect, upshot, end, aftermath, event, resultant, corollary, end product, conclusion, fruit, consummation; Antonyms for OUTCOME: cause, origin, source, beginning. ... 101 Sociology Research Topics That Make an Impact How to Write an Appeal Letter That Gets Results Opinion Examples Examples of ...

The outcome of a legal proceeding. An occurrence, or something that happens. A thing that is complete in itself. The end or conclusion of something. The reason for which something or someone is used or suited for. The principle on which an idea, activity or process is based on. The act of counting or numbering things.

OUTCOME - Synonyms, related words and examples | Cambridge English Thesaurus

ensure a pro‑Western outcome - English Only forum equivalent to the outcome …<but ><and> without the expenditure - English Only forum eventuality/outcome - English Only forum exposure and outcome - English Only forum fielding outcome - English Only forum good luck will maximize the outcome of my hard work - English Only forum

Abstract. Outcomes research, which investigates the outcomes of health care practices, is intended to provide scientific evidence for clinical decision making and health care. This paper elucidates the goal and domains of outcomes research. Also it shows the potential and promise of outcomes research to provide a methodology to uncover what to ...

Synonyms for OUTCOME in English: result, end, consequence, conclusion, end result, payoff, upshot, outcome, result, upshot, …

Synonyms for OUTCOMES: results, consequences, resultants, effects, products, aftermaths, developments, issues; Antonyms of OUTCOMES: factors, reasons, causes ...

Synonyms for outcomes include results, consequences, conclusions, corollaries, ends, reactions, by-products, product, effects and produce. Find more similar words at ...

Synonyms for RESULT: outcome, resultant, consequence, product, effect, aftermath, matter of course, upshot; Antonyms of RESULT: cause, reason, basis, consideration ...

Synonyms for OUTCOMES: results, upshots, issues, end, consequences, effects, events, terminations, ramifications, scores, sequences, residua, reactions; Antonyms for OUTCOMES: causes, beginnings, sources, origins. ... 101 Sociology Research Topics That Make an Impact How to Write an Appeal Letter That Gets Results Opinion Examples Examples of ...

Synonyms for RESULTS: outcomes, consequences, resultants, products, effects, aftermaths, fruits, developments; Antonyms of RESULTS: reasons, causes, factors ...

AI in surgical decision-making helps enhance surgical resection margins, shorten operating times, and increase efficiency. A recent patient-agnostic transfer-learned neural network uses quick ...

Abstract Background: Epidemiological research commonly investigates single exposure-outcome relationships, while childrens experiences across a variety of early lifecourse domains are intersecting. To design realistic interventions, epidemiological research should incorporate information from multiple risk exposure domains to assess effect on health outcomes. In this paper we identify ...

In patients with dyssynchronous heart failure (DHF), cardiac conduction abnormalities cause the regional distribution of myocardial work to be non-homogeneous. Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) using an implantable, programmed biventricular pacemaker/defibrillator, can improve the synchrony of contraction between the right and left ventricles in DHF, resulting in reduced morbidity and ...