Stem Cell Therapy for Retinal Degeneration: The Evidence to Date

Affiliation.

- 1 Stem Cells and Cancer Biology Research Group, Department of Biosciences and Bioengineering, Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati, Guwahati, Assam, 781039, India.

- PMID: 34349498

- PMCID: PMC8327474

- DOI: 10.2147/BTT.S290331

There is a rise in the number of people who have vision loss due to retinal diseases, and conventional therapies for treating retinal degeneration fail to repair and regenerate the damaged retina. Several studies in animal models and human trials have explored the use of stem cells to repair the retinal tissue to improve visual acuity. In addition to the treatment of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and diabetic retinopathy (DR), stem cell therapies were used to treat genetic diseases such as retinitis pigmentosa (RP) and Stargardt's disease, characterized by gradual loss of photoreceptor cells in the retina. Transplantation of retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells derived from embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) have shown promising results in improving retinal function in various preclinical models of retinal degeneration and clinical studies without any severe side effects. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) were utilized to treat optic neuropathy, RP, DR, and glaucoma with positive clinical outcomes. This review summarizes the preclinical and clinical evidence of stem cell therapy and current limitations in utilizing stem cells for retinal degeneration.

Keywords: embryonic stem cells; induced pluripotent stem cells; mesenchymal stem cells; retinal degeneration; retinal pigment epithelial cells; retinitis pigmentosa.

© 2021 Sharma and Jaganathan.

Publication types

- For Authors

- Editorial Board

- Journals Home

To View More...

Purchase this article with an account.

- Defining Neural Progenitors as Stem Cells

- Neural Stem Cells-Progenitors in the Mammalian Eye

- Therapeutic Uses of Neural Stem Cells-Progenitors

- Iqbal Ahmad From the Department of Ophthalmology, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, Nebraska.

- Full Article

This feature is available to authenticated users only.

Iqbal Ahmad; Stem Cells: New Opportunities to Treat Eye Diseases. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2001;42(12):2743-2748.

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

© ARVO (1962-2015); The Authors (2016-present)

- Get Permissions

- Supplements

Related Articles

From other journals, related topics.

- Nanotechnology and Regenerative Medicine

- Eye Anatomy and Disorders

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

You must be signed into an individual account to use this feature.

Advertisement

The Potential of Stem Cells as Treatment for Ocular Surface Diseases

- Ocular Surface (A Galor, Section Editor)

- Published: 11 November 2022

- Volume 10 , pages 209–217, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Andres Serrano 1 ,

- Kwaku A. Osei 1 ,

- Marcela Huertas-Bello 1 &

- Alfonso L. Sabater ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6383-2558 1

214 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Purpose of Review

In this article, we review recent studies that examine stem cells as a potential treatment for ocular surface diseases.

Recent Findings

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) derived from non-ocular surface tissues were effective in treating limbal stem cell deficiency and corneal endothelial dysfunction. In dry eye, limbal stem cells reduced ocular symptoms, while MSCs improved tear secretion and tear quality and reduced symptoms and inflammatory cytokine expression. There were no clinically significant adverse effects associated with stem cell treatment.

While available evidence supports stem cells as a potential treatment for ocular surface diseases, the applicability of these therapies in humans has yet to be fully established, given that over 80% of studies evaluating stem cell treatments have been carried out in animal models and non-human subjects. Future studies examining the safety and efficacy of stem cell therapies for ocular surface diseases in humans are thus warranted.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Regeneration of the Ocular Surface

Pluripotent Stem Cells and Other Innovative Strategies for the Treatment of Ocular Surface Diseases

Mini review: human clinical studies of stem cell therapy in keratoconus

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • of importance •• of major importance.

The definition and classification of dry eye disease. report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007). Ocul Surf. 2007;5(2):75–92.

Article Google Scholar

Narayanan S, Redfern RL, Miller WL, Nichols KK, McDermott AM. Dry eye disease and microbial keratitis: is there a connection? Ocul Surf. 2013;11(2):75–92.

Cavuoto KM, Stradiotto AC, Galor A. Role of the ocular surface microbiome in allergic disease. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;19(5):482–7.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Garza A, Diaz G, Hamdan M, Shetty A, Hong BY, Cervantes J. Homeostasis and defense at the surface of the eye. The conjunctival microbiota Curr Eye Res. 2021;46(1):1–6.

Li Z, Duan H, Jia Y, Zhao C, Li W, Wang X, et al. Long-term corneal recovery by simultaneous delivery of hPSC-derived corneal endothelial precursors and nicotinamide. J Clin Invest. 2022;132(1):e146658. This animal study shows that co-administered human embryonic stem cell-derived corneal endothelial precursors and nicotinamide are effective for corneal endothelial dysfunction .

Sun P, Shen L, Li YB, Du LQ, Wu XY. Long-term observation after transplantation of cultured human corneal endothelial cells for corneal endothelial dysfunction. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13(1):228. This animal study shows that orbital adipose stem cell-derived hCECs have the capacity to regenerate a diseased corneal endothelium .

Wei LN, Wu CH, Lin CT, Liu IH. Topical applications of allogeneic adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate the canine keratoconjunctivitis sicca. BMC Vet Res. 2022;18(1):217. This animal study shows the therapeutic potential of adipose mesenchymal stem cells for dry eye treatment .

Shen K, Wang XJ, Liu KT, Li SH, Li J, Zhang JX, et al. Effects of exosomes from human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells on inflammatory response of mouse RAW264.7 cells and wound healing of full-thickness skin defects in mice. Zhonghua Shao Shang Za Zhi. 2022;38(3):215–26.

CAS Google Scholar

Wang G, Li H, Long H, Gong X, Hu S, Gong C. Exosomes derived from mouse adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells alleviate benzalkonium chloride-induced mouse dry eye model via inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome. Ophthalmic Res. 2022;65(1):40–51. This animal study shows that exoxomes from adipose stem cells have therapeutic potential in dry eye treatment .

Fu YS, Chen PR, Yeh CC, Pan JY, Kuo WC, Tseng KW. Human umbilical mesenchymal stem cell xenografts repair UV-induced photokeratitis in a rat model. Biomedicines. 2022;10(5):1125. This animal study shows the potential of umbilical cord-mesenchymal stem cells in treating photokeratitis .

Elhusseiny AM, Soleimani M, Eleiwa TK, ElSheikh RH, Frank CR, Naderan M, et al. Current and emerging therapies for limbal stem cell deficiency. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2022;11(3):259–68.

Kumar A, Yun H, Funderburgh ML, Du Y. Regenerative therapy for the cornea. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2022;87: 101011.

Ali M, Khan SY, Gottsch JD, Hutchinson EK, Khan A, Riazuddin SA. Pluripotent stem cell-derived corneal endothelial cells as an alternative to donor corneal endothelium in keratoplasty. Stem Cell Rep. 2021;16(9):2320–35. This animal shows the potential of cryopreserved human embryonic stem cell-derived endothelial cells to regenerate a dysfunctional corneal endothelium .

Hermida-Prieto M, Garcia-Castro J, Marinas-Pardo L. Systemic treatment of immune-mediated keratoconjunctivitis sicca with allogeneic stem cells improves the Schirmer tear test score in a canine spontaneous model of disease. J Clin Med. 2021;10(24):5981. This animal study shows that mesenchymal stem cells from adipose tissue improve tear secretion .

Moller-Hansen M, Larsen AC, Toft PB, Lynggaard CD, Schwartz C, Bruunsgaard H, et al. Safety and feasibility of mesenchymal stem cell therapy in patients with aqueous deficient dry eye disease. Ocul Surf. 2021;19:43–52. This clinical trial shows that allogeneic adipose mesenchymal stems can be an effective dry eye treatment .

Ruan Y, Jiang S, Musayeva A, Pfeiffer N, Gericke A. Corneal epithelial stem cells-physiology, pathophysiology and therapeutic options. Cells. 2021;10(9):2302.

Singh V, Tiwari A, Kethiri AR, Sangwan VS. Current perspectives of limbal-derived stem cells and its application in ocular surface regeneration and limbal stem cell transplantation. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2021;10(8):1121–8.

Rush SW, Chain J, Das H. Corneal epithelial stem cell supernatant in the treatment of severe dry eye disease: a pilot study. Clin Ophthalmol. 2021;15:3097–107. This clinical study shows the potential of donor limbal stem cells in treating limbal stem cell deficiency .

Falcao MSA, Brunel H, Peixer MAS, Dallago BSL, Costa FF, Queiroz LM, et al. Effect of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) on corneal wound healing in dogs. J Tradit Complement Med. 2020;10(5):440–5. This animal study shows adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells as a treatment option for refractory corneal ulcer .

Ghareeb AE, Lako M, Figueiredo FC. Recent advances in stem cell therapy for limbal stem cell deficiency: a narrative review. Ophthalmol Ther. 2020;9(4):809–31.

He J, Ou S, Ren J, Sun H, He X, Zhao Z, et al. Tissue engineered corneal epithelium derived from clinical-grade human embryonic stem cells. Ocul Surf. 2020;18(4):672–80.

Calonge M, Perez I, Galindo S, Nieto-Miguel T, Lopez-Paniagua M, Fernandez I, et al. A proof-of-concept clinical trial using mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of corneal epithelial stem cell deficiency. Transl Res. 2019;206:18–40.

Shukla S, Mittal SK, Foulsham W, Elbasiony E, Singhania D, Sahu SK, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of different routes of mesenchymal stem cell administration in corneal injury. Ocul Surf. 2019;17(4):729–36.

Galindo S, Herreras JM, Lopez-Paniagua M, Rey E, de la Mata A, Plata-Cordero M, et al. Therapeutic effect of human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells in experimental corneal failure due to limbal stem cell niche damage. Stem Cells. 2017;35(10):2160–74.

Zhang C, Du L, Sun P, Shen L, Zhu J, Pang K, et al. Construction of tissue-engineered full-thickness cornea substitute using limbal epithelial cell-like and corneal endothelial cell-like cells derived from human embryonic stem cells. Biomaterials. 2017;124:180–94.

Bittencourt MK, Barros MA, Martins JF, Vasconcellos JP, Morais BP, Pompeia C, et al. Allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in dogs with keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Cell Med. 2016;8(3):63–77.

Villatoro AJ, Fernandez V, Claros S, Rico-Llanos GA, Becerra J, Andrades JA. Use of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells in keratoconjunctivitis sicca in a canine model. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015: 527926.

Ramos T, Scott D, Ahmad S. An update on ocular surface epithelial stem cells: cornea and conjunctiva. Stem Cells Int. 2015;2015: 601731.

Beyazyildiz E, Pinarli FA, Beyazyildiz O, Hekimoglu ER, Acar U, Demir MN, et al. Efficacy of topical mesenchymal stem cell therapy in the treatment of experimental dry eye syndrome model. Stem Cells Int. 2014;2014: 250230. This animal study shows the efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells in treating benzalkonium cholride-induced dry eye .

Weng J, He C, Lai P, Luo C, Guo R, Wu S, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells treatment attenuates dry eye in patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Mol Ther. 2012;20(12):2347–54.

Damdimopoulou P, Rodin S, Stenfelt S, Antonsson L, Tryggvason K, Hovatta O. Human embryonic stem cells. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;31:2–12.

Dhamodaran K, Subramani M, Ponnalagu M, Shetty R, Das D. Ocular stem cells: a status update! Stem Cell Res Ther. 2014;5(2):56.

Alison MR, Poulsom R, Forbes S, Wright NA. An introduction to stem cells. J Pathol. 2002;197(4):419–23.

Collin J, Queen R, Zerti D, Bojic S, Dorgau B, Moyse N, et al. A single cell atlas of human cornea that defines its development, limbal progenitor cells and their interactions with the immune cells. Ocul Surf. 2021;21:279–98.

Zakrzewski W, Dobrzynski M, Szymonowicz M, Rybak Z. Stem cells: past, present, and future. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):68.

Henningson CT Jr, Stanislaus MA, Gewirtz AM. 28 Embryonic and adult stem cell therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111(2 Suppl):S745-53.

Bacakova L, Zarubova J, Travnickova M, Musilkova J, Pajorova J, Slepicka P, et al. Stem cells: their source, potency and use in regenerative therapies with focus on adipose-derived stem cells - a review. Biotechnol Adv. 2018;36(4):1111–26.

Kolios G, Moodley Y. Introduction to stem cells and regenerative medicine. Respiration. 2013;85(1):3–10.

Bremond-Gignac D, Copin H, Benkhalifa M. Corneal epithelial stem cells for corneal injury. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2018;18(9):997–1003.

Marion NW, Mao JJ. Mesenchymal stem cells and tissue engineering. Methods Enzymol. 2006;420:339–61.

Pinnamaneni N, Funderburgh JL. Concise review: stem cells in the corneal stroma. Stem Cells. 2012;30(6):1059–63.

Levis HJ, Daniels JT. Recreating the human limbal epithelial stem cell niche with bioengineered limbal crypts. Curr Eye Res. 2016;41(9):1153–60.

Yoon JJ, Ismail S, Sherwin T. Limbal stem cells: central concepts of corneal epithelial homeostasis. World J Stem Cells. 2014;6(4):391–403.

Stewart RM, Sheridan CM, Hiscott PS, Czanner G, Kaye SB. Human conjunctival stem cells are predominantly located in the medial canthal and inferior forniceal areas. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(3):2021–30.

Du Y, Funderburgh ML, Mann MM, SundarRaj N, Funderburgh JL. Multipotent stem cells in human corneal stroma. Stem Cells. 2005;23(9):1266–75.

Amano S, Yamagami S, Mimura T, Uchida S, Yokoo S. Corneal stromal and endothelial cell precursors. Cornea. 2006;25(10 Suppl 1):S73–7.

Yu WY, Sheridan C, Grierson I, Mason S, Kearns V, Lo AC, et al. Progenitors for the corneal endothelium and trabecular meshwork: a potential source for personalized stem cell therapy in corneal endothelial diseases and glaucoma. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011: 412743.

Samoila O, Samoila L. Stem cells in the path of light, from corneal to retinal reconstruction. Biomedicines. 2021;9(8):873.

Alviano F, Fossati V, Marchionni C, Arpinati M, Bonsi L, Franchina M, et al. Term amniotic membrane is a high throughput source for multipotent mesenchymal stem cells with the ability to differentiate into endothelial cells in vitro. BMC Dev Biol. 2007;7:11.

Paunescu V, Deak E, Herman D, Siska IR, Tanasie G, Bunu C, et al. In vitro differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells to epithelial lineage. J Cell Mol Med. 2007;11(3):502–8.

Saghizadeh M, Kramerov AA, Svendsen CN, Ljubimov AV. Concise review: stem cells for corneal wound healing. Stem Cells. 2017;35(10):2105–14.

Uccelli A, Moretta L, Pistoia V. Immunoregulatory function of mesenchymal stem cells. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36(10):2566–73.

Bandeira F, Goh TW, Setiawan M, Yam GH, Mehta JS. Cellular therapy of corneal epithelial defect by adipose mesenchymal stem cell-derived epithelial progenitors. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11(1):14.

Kuroda Y, Kitada M, Wakao S, Dezawa M. Bone marrow mesenchymal cells: how do they contribute to tissue repair and are they really stem cells? Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz). 2011;59(5):369–78.

Ullah I, Subbarao RB, Rho GJ. Human mesenchymal stem cells - current trends and future prospective. Biosci Rep. 2015;35(2):e00191.

Call M, Meyer EA, Kao WW, Kruse FE, Schltzer-Schrehardt U. Murine hair follicle derived stem cell transplantation onto the cornea using a fibrin carrier. Bio Protoc. 2018;8(10): e2849.

Medvedev SP, Shevchenko AI, Zakian SM. Induced pluripotent stem cells: problems and advantages when applying them in regenerative medicine. Acta Naturae. 2010;2(2):18–28.

Gorecka J, Kostiuk V, Fereydooni A, Gonzalez L, Luo J, Dash B, et al. The potential and limitations of induced pluripotent stem cells to achieve wound healing. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):87.

Moradi S, Mahdizadeh H, Saric T, Kim J, Harati J, Shahsavarani H, et al. Research and therapy with induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs): social, legal, and ethical considerations. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):341.

Hayashi R, Ishikawa Y, Sasamoto Y, Katori R, Nomura N, Ichikawa T, et al. Co-ordinated ocular development from human iPS cells and recovery of corneal function. Nature. 2016;531(7594):376–80.

Hayashi R, Ishikawa Y, Katori R, Sasamoto Y, Taniwaki Y, Takayanagi H, et al. Coordinated generation of multiple ocular-like cell lineages and fabrication of functional corneal epithelial cell sheets from human iPS cells. Nat Protoc. 2017;12(4):683–96.

Thoft RA. Conjunctival transplantation. Arch Ophthalmol. 1977;95(8):1425–7.

Shanbhag SS, Patel CN, Goyal R, Donthineni PR, Singh V, Basu S. Simple limbal epithelial transplantation (SLET): review of indications, surgical technique, mechanism, outcomes, limitations, and impact. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2019;67(8):1265–77.

Soleimani M, Naderan M. Management strategies of ocular chemical burns: current perspectives. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:2687–99.

Cullen AP. Photokeratitis and other phototoxic effects on the cornea and conjunctiva. Int J Toxicol. 2002;21(6):455–64.

Bergmanson JP. Corneal damage in photokeratitis–why is it so painful? Optom Vis Sci. 1990;67(6):407–13.

Wongvisavavit R, Parekh M, Ahmad S, Daniels JT. Challenges in corneal endothelial cell culture. Regen Med. 2021;16(9):871–91.

Eye Bank Association of America. 2020 Eye Banking Statistical Report. Washington, DC: Eye Bank Association of America; 2021.

Google Scholar

Ali M, Khan SY, Vasanth S, Ahmed MR, Chen R, Na CH, et al. Generation and proteome profiling of PBMC-originated, iPSC-derived corneal endothelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59(6):2437–44. This animal study shows that induced pluripotent stem cell-derived corneal endothelial cells (CECs) closely mimic human CECs .

Craig JP, Nichols KK, Akpek EK, Caffery B, Dua HS, Joo CK, et al. TFOS DEWS II definition and classification report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):276–83.

Bron AJ, de Paiva CS, Chauhan SK, Bonini S, Gabison EE, Jain S, et al. TFOS DEWS II pathophysiology report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):438–510.

Messmer EM, von Lindenfels V, Garbe A, Kampik A. Matrix metalloproteinase 9 testing in dry eye disease using a commercially available point-of-care immunoassay. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(11):2300–8.

Yamaguchi T. Inflammatory response in dry eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59(14):DES192–9.

Yoshida A, Fujihara T, Nakata K. Cyclosporin A increases tear fluid secretion via release of sensory neurotransmitters and muscarinic pathway in mice. Exp Eye Res. 1999;68(5):541–6.

Ames P, Galor A. Cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsions for the treatment of dry eye: a review of the clinical evidence. Clin Investig (Lond). 2015;5(3):267–85.

Song N, Scholtemeijer M, Shah K. Mesenchymal stem cell immunomodulation: mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2020;41(9):653–64.

Ren K. Exosomes in perspective: a potential surrogate for stem cell therapy. Odontology. 2019;107(3):271–84.

Li N, Zhao L, Wei Y, Ea VL, Nian H, Wei R. Recent advances of exosomes in immune-mediated eye diseases. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):278.

Zheng Q, Zhang S, Guo WZ, Li XK. The unique immunomodulatory properties of MSC-derived exosomes in organ transplantation. Front Immunol. 2021;12: 659621.

Chen W, Huang Y, Han J, Yu L, Li Y, Lu Z, et al. Immunomodulatory effects of mesenchymal stromal cells-derived exosome. Immunol Res. 2016;64(4):831–40.

Zheng Q, Ren Y, Reinach PS, She Y, Xiao B, Hua S, et al. Reactive oxygen species activated NLRP3 inflammasomes prime environment-induced murine dry eye. Exp Eye Res. 2014;125:1–8.

Zheng Q, Ren Y, Reinach PS, Xiao B, Lu H, Zhu Y, et al. Reactive oxygen species activated NLRP3 inflammasomes initiate inflammation in hyperosmolarity stressed human corneal epithelial cells and environment-induced dry eye patients. Exp Eye Res. 2015;134:133–40.

Zhou T, He C, Lai P, Yang Z, Liu Y, Xu H, et al. miR-204-containing exosomes ameliorate GVHD-associated dry eye disease. Sci Adv. 2022;8(2):eabj9617. This clinical trial shows that mesenchymal stem cell exoxomes can be effective in treating graft-versus-host disease dry eye .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, 900 NW 17Th St., Miami, FL, 33136, USA

Andres Serrano, Kwaku A. Osei, Marcela Huertas-Bello & Alfonso L. Sabater

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Alfonso L. Sabater .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Human/Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Ocular Surface

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Serrano, A., Osei, K.A., Huertas-Bello, M. et al. The Potential of Stem Cells as Treatment for Ocular Surface Diseases. Curr Ophthalmol Rep 10 , 209–217 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40135-022-00303-6

Download citation

Accepted : 24 October 2022

Published : 11 November 2022

Issue Date : December 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40135-022-00303-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Corneal endothelial dysfunction

- Limbal stem cell deficiency

- Ocular surface disease

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Virtual Tour

- Staff Directory

- En Español

You are here

News releases.

News Release

Tuesday, January 2, 2018

NIH discovery brings stem cell therapy for eye disease closer to the clinic

Stem cell-derived retinal cells need primary cilia to support survival of light-sensing photoreceptors.

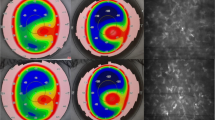

Scientists at the National Eye Institute (NEI), part of the National Institutes of Health, report that tiny tube-like protrusions called primary cilia on cells of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) — a layer of cells in the back of the eye — are essential for the survival of the retina’s light-sensing photoreceptors. The discovery has advanced efforts to make stem cell-derived RPE for transplantation into patients with geographic atrophy, otherwise known as dry age-related macular degeneration (AMD), a leading cause of blindness in the U.S. The study appears in the January 2 Cell Reports.

“We now have a better idea about how to generate and replace RPE cells, which appear to be among the first type of cells to stop working properly in AMD,” said the study’s lead investigator, Kapil Bharti, Ph.D., Stadtman investigator at the NEI. Bharti is leading the development of patient stem cell-derived RPE for an AMD clinical trial set to launch in 2018.

In a healthy eye, RPE cells nourish and support photoreceptors, the cells that convert light into electrical signals that travel to the brain via the optic nerve. RPE cells form a layer just behind the photoreceptors. In geographic atrophy, RPE cells die, which causes photoreceptors to degenerate, leading to vision loss.

Bharti and his colleagues are hoping to halt and reverse the progression of geographic atrophy by replacing diseased RPE with lab-made RPE. The approach involves using a patient’s blood cells to generate induced-pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), cells capable of becoming any type of cell in the body. iPSCs are grown in the laboratory and then coaxed into becoming RPE for surgical implantation.

Attempts to create functional RPE implants, however, have hit a recurring obstacle: iPSCs programmed to become RPE cells have a tendency to get developmentally stuck, said Bharti. “The cells frequently fail to mature into functional RPE capable of supporting photoreceptors. In cases where they do mature, however, RPE maturation coincides with the emergence of primary cilia on the iPSC-RPE cells.”

The researchers tested three drugs known to modulate the growth of primary cilia on iPSC-derived RPE. As predicted, the two drugs known to enhance cilia growth significantly improved the structural and functional maturation of the iPSC-derived RPE. One important characteristic of maturity observed was that the RPE cells all oriented properly, correctly forming a single, functional monolayer. The iPSC-derived RPE cell gene expression profile also resembled that of adult RPE cells. And importantly, the cells performed a crucial function of mature RPE cells: they engulfed the tips of photoreceptor outer segments, a pruning process that keeps photoreceptors working properly.

By contrast, iPSC-derived RPE cells exposed to the third drug, an inhibitor of cilia growth, demonstrated severely disrupted structure and functionality.

As further confirmation of their observations, when the researchers genetically knocked down expression of cilia protein IFT88, the iPSC-derived RPE showed severe maturation and functional defects, as confirmed by gene expression analysis. Tissue staining showed that knocking down IFT88 led to reduced iPSC-derived RPE cell density and functional polarity, i.e., cells within the RPE tissue pointed in the wrong direction.

Bharti and his group found similar results in iPSC-derived lung cells, another type of epithelial cell with primary cilia. When iPSC-derived lung cells were exposed to drugs that enhance cilia growth, immunostaining confirmed that the cells looked structurally mature.

The report suggests that primary cilia regulate the suppression of the canonical WNT pathway, a cell signaling pathway involved in embryonic development. Suppression of the WNT pathway during RPE development instructs the cells to stop dividing and to begin differentiating into adult RPE, according to the researchers.

The researchers also generated iPSC-derived RPE from a patient with ciliopathy, a disorder that causes severe vision loss due to photoreceptor degeneration. The patient’s ciliopathy was associated with mutations of cilia gene CEP290. Compared to a healthy donor, iPSC-derived RPE from the ciliopathy patient had cilia that were smaller. The patient’s iPSC-derived RPE also had maturation and functional defects similar to those with IFT88 knockdown.

Further studies in a mouse model of ciliopathy confirmed an important temporal relationship: Looking across several early development stages, the RPE defects preceded the photoreceptor degeneration, which provides additional insights into ciliopathy-induced retinal degeneration.

The study’s findings have been incorporated into the group’s protocol for making clinical-grade iPSC-derived RPE. They will also inform the development of disease models for research of AMD and other degenerative retinal diseases, Bharti said.

This work was supported by the NEI intramural research program and the NIH Common Fund’s Regenerative Medicine Program.

NEI leads the federal government’s research on the visual system and eye diseases. NEI supports basic and clinical science programs to develop sight-saving treatments and address special needs of people with vision loss. For more information, visit https://www.nei.nih.gov .

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH): NIH, the nation's medical research agency, includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the primary federal agency conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit www.nih.gov .

NIH…Turning Discovery Into Health ®

May-Simera, Helen Louise et al. “Primary Cilium Mediated Retinal Pigment Epithelium Maturation is Retarded in Ciliopathy Patient Cells”. Cell Reports. Published online January 2, 2018. DOI:10.1016/j.celrep.2017.12.038

Connect with Us

- More Social Media from NIH

Streamlining stem cells to treat macular degeneration

As we age, so do our eyes; most commonly, this involves changes to our vision and new glasses, but there are more severe forms of age-related eye problems. One of these is age-related macular degeneration, which affects the macula -- the back part of the eye that gives us sharp vision and the ability to distinguish details. The result is a blurriness in the central part of our visual field.

The macula is part of the eye's retina, which is the light-sensitive tissue mostly composed of the eye's visual cells: cone and rod photoreceptor cells. The retina also contains a layer called the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), which has several important functions, including light absorption, cleaning up cellular waste, and keeping the other cells of the eye healthy.

The cells of the RPE also nourish and maintain the eye's photoreceptor cells, which is why one of the most promising treatment strategies for age-related macular degeneration is to replace aging, degenerating RPE cells with new ones grown from human embryonic stem cells.

Scientist have proposed several methods for converting stem cells into RPE, but there is still a gap in our knowledge of how cells respond to these stimuli over time. For example, some protocols take a few months while others can take up to a year. And yet, scientists are not clear as to what exactly happens over that period of time.

Mixed cell populations

"None of the differentiation protocols proposed for clinical trials have been scrutinized over time at the single-cell level -- we know they can make retinal pigment cells, but how cells evolve to that state remains a mystery," says Dr Gioele La Manno, a researcher with EPFL's Life Sciences Independent Research (ELISIR) program.

"Overall, the field has been so focused on the product of differentiation, that the path undertaken has been sometimes overlooked," he adds. "For the field to move forward, it is important to understand aspects of the dynamics of what happens in these protocols. The path to maturity could be as important as the end state, for example for the safety of treatment or for improving cell purity and reducing production time."

Tracking stem cells as they grow into RPE cells

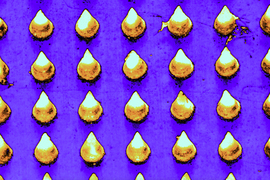

La Manno has now led a study with Professor Fredrik Lanner at the Karolinska Institute (Sweden) profiling a protocol for differentiating human embryonic stem cells into RPE cells that is actually intended for clinical use. Their work shows that the protocol can develop safe and efficient pluripotent stem cell-based therapies for age-related macular degeneration. The study is published and featured on this month's cover of the journal Stem Cell Reports .

"Standard methods such as quantitative PCR and bulk RNA-seq capture the average expression of RNAs from large populations of cells," says Alex Lederer, a doctoral student at EPFL and one of the study's lead authors. "In mixed-cell populations, these measurements may obscure critical differences between individual cells that are important for knowing if the process is unfolding correctly." Instead, the researchers used a technique called single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), which can detect all the active genes in an individual cell at a given time.

Looking at intermediate states

Using scRNA-seq, the researchers were able to study the entire gene expression profile of individual human embryonic stem cells throughout the differentiation protocol, which takes a total of sixty days. This allowed them to map out all the transient states within a population as they grew into retinal pigment cells, but also to optimize the protocol and suppress the growth of non-RPE cells, thus preventing the formation of contaminant cell populations. "The aim is to prevent mixed cell populations at the time of transplantation, and to make sure the cells at the endpoint are similar to original RPE cells from a patient's eye," says Lederer.

What they found was that on the way to becoming RPE cells, stem cells go through a process very similar to early embryonic development. During this, the cell culture took up a "rostral embryo patterning," the process that develops the embryo's neural tube, which will go on to become its brain and sensory systems for vision, hearing, and taste. After this patterning, the stem cells began to mature into RPE cells.

Eye-to-eye: transplanting RPE cells in an animal model

But the point of the differentiation protocol is to generate a pure population of RPE cells that can be implanted in patients' retinas to slow down macular degeneration. So the team transplanted their population of cells that had been monitored with scRNA-seq into the subretinal space of two female New Zealand white albino rabbits, which are what scientists in the field refer to as a "large-eyed animal model." The operation was carried out following approval by the Northern Stockholm Animal Experimental Ethics Committee.

The work showed that the protocol not only produces a pure RPE cell population but that those cells can continue maturing even after they have been transplanted in the subretinal space. "Our work shows that the differentiation protocol can develop safe and efficient pluripotent stem cell-based therapies for age-related macular degeneration," says Dr Fredrik Lanner, who is currently making sure the protocol can be soon used in clinics.

- Immune System

- Skin Cancer

- Hearing Impairment

- Schizophrenia

- Neuroscience

- Embryonic stem cell

- Adult stem cell

- Gene therapy

- Chemotherapy

- Stem cell treatments

- Bone marrow transplant

Story Source:

Materials provided by Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne . Original written by Nik Papageorgiou. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Journal Reference :

- Sandra Petrus-Reurer, Alex R. Lederer, Laura Baqué-Vidal, Iyadh Douagi, Belinda Pannagel, Irina Khven, Monica Aronsson, Hammurabi Bartuma, Magdalena Wagner, Andreas Wrona, Paschalis Efstathopoulos, Elham Jaberi, Hanni Willenbrock, Yutaka Shimizu, J. Carlos Villaescusa, Helder André, Erik Sundstrӧm, Aparna Bhaduri, Arnold Kriegstein, Anders Kvanta, Gioele La Manno, Fredrik Lanner. Molecular profiling of stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelial cell differentiation established for clinical translation . Stem Cell Reports , 2022; 17 (6): 1458 DOI: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2022.05.005

Cite This Page :

Explore More

- Life Expectancy May Increase by 5 Years by 2050

- Toward a Successful Vaccine for HIV

- Highly Efficient Thermoelectric Materials

- Toward Human Brain Gene Therapy

- Whale Families Learn Each Other's Vocal Style

- AI Can Answer Complex Physics Questions

- Otters Use Tools to Survive a Changing World

- Monogamy in Mice: Newly Evolved Type of Cell

- Sustainable Electronics, Doped With Air

- Male Vs Female Brain Structure

Trending Topics

Strange & offbeat.

Taming Unruly Stem Cells to Enhance Eye Research

Widely Available Molecule Could Aid Development of Therapies for Blinding Diseases

By Brandon Levy

Tuesday, October 4, 2022

IRP researchers have discovered that a cheap, widely available molecule can help lab-grown stem cells develop into complex, three-dimensional models of the eye’s retina.

As scientists inch closer to growing fully functioning organs outside the body, it’s easy to forget that it’s already possible to grow miniature, simplified versions of some organs in the lab. These ‘organoids’ are an extremely useful research tool, but producing them can be tricky. New IRP research could make it much easier to grow organoids that mimic the eye’s retina, thereby accelerating discoveries about a variety of vision-impairing diseases. 1

Retinal organoids are three-dimensional structures with distinct layers containing all the major cell types found in the real human retina, the part of the eye that converts light into electrical signals the brain can interpret. While organoids aren’t perfect models, they are much closer to the real deal than the flat collections of a single cell type that scientists have long used for their experiments.

“A retinal organoid is as close to being a retina in a dish as we’ve ever had,” says IRP senior investigator Tiansen Li, Ph.D. , the new study’s senior author.

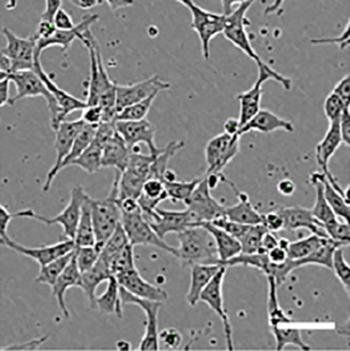

What’s more, scientists can grow retinal organoids that have the exact same genetic mutations as a patient with an eye disease, enabling them to investigate the biological causes of a person’s specific vision problems. This involves taking skin or blood cells from the patient and turning them into cells called induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which can develop into any cell type found in the body. These iPSCs can then be grown in unlimited quantities to create ‘cell lines’ with specific properties, and researchers like those in Dr. Li’s lab coax them to develop into retinal organoids by exposing them to specific molecules. Unfortunately, not all cell lines cooperate with the scientists trying to manipulate them.

Human pluripotent stem cells, as seen under a microscope.

“The cell lines that we create from different people can react differently to our process,” says IRP postdoctoral fellow Florian Regent, Ph.D., who led the new study in Dr. Li’s lab. “Our process can be very effective for some cell lines and not for others. And, of course, when you want to study a particular patient’s cell line, you can’t work with a different one — the process has to work with that cell line.”

In the new study, Dr. Li’s team added an additional chemical to their standard process for turning iPSCs into retinal organoids: a form of vitamin B3 called nicotinamide that is commonly found in dietary supplements. The group selected nicotinamide for the experiment because it has previously been used to encourage iPSCs to develop into a different part of the retina, the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE).

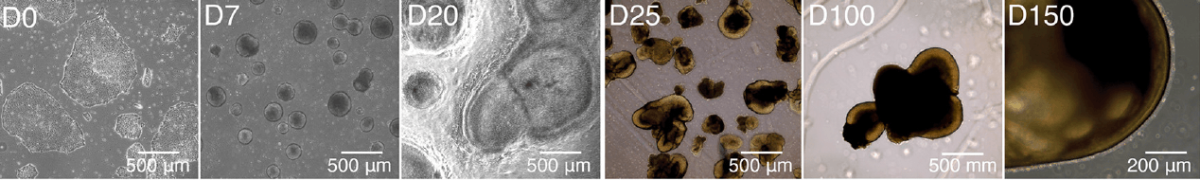

At the beginning of their experiment, the IRP researchers exposed stem cells from eight different cell lines to nicotinamide for either eight or twenty one days. Some of the cell lines readily developed into retinal organoids even without the nicotinamide treatment, while others did not. The researchers discovered that the eight-day nicotinamide treatment significantly increased the yield of retinal organoids from all of the cell lines, including those that produced very few organoids in the absence of nicotinamide. The three-week treatment also boosted organoid yields from some of the cell lines, but decreased the yield for one cell line, suggesting that nicotinamide treatment is more beneficial during a specific, narrow developmental window.

“During development, cells are influenced by their intrinsic programs, obviously, but also by external environmental cues,” Dr. Li explains. “These cues act at defined time points, so a cue that does one thing at one point in time, two days later might do the opposite. That applies to nicotinamide as well. If you apply it for an extended duration, it might overstay its welcome.”

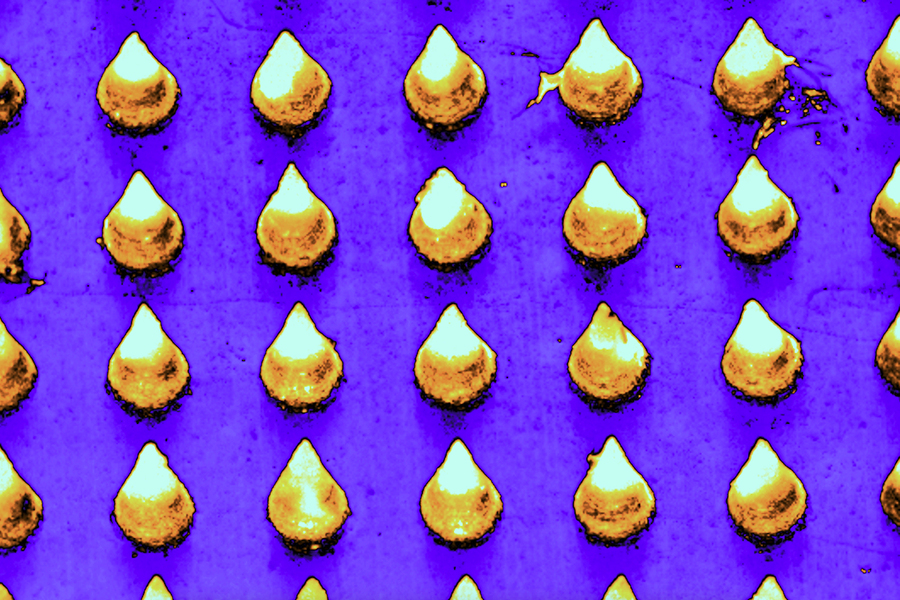

These images from the study show how induced pluripotent stem cells develop into retinal organoids over the course of 150 days.

The study also shed light on why nicotinamide encourages iPSCs to develop into retinal organoids. During the early stages of the experiment, the stem cells treated with nicotinamide more readily transformed into an immature form of neural cells capable of eventually becoming retinal cells, as opposed to changing into the sorts of immature cells that could only develop into cell types like skin and bone cells. Moreover, the researchers discovered that nicotinamide-treated cells had lower activity in a set of genes related to bone morphogenic protein (BMP), a molecule that plays an important role in embryonic development. This discovery suggests that inhibition of this BMP-related cellular system is one reason — though likely not the only reason — why nicotinamide helps turn stem cells into retinal organoids.

Dr. Florian Regent (left) and Dr. Tiansen Li (right)

Regardless of how exactly nicotinamide works its magic, Dr. Li believes that it could soon become a standard part of the procedures other labs use to produce retinal organoids. Nicotinamide is cheap and widely available, and by using it to facilitate the creation of retinal organoids from stem cell lines that previously refused to develop into them, scientists could find it much easier to make discoveries about a number of diseases that affect vision.

“We continue to gather data to support the validity of this approach, and our hope and expectation is that the entire field will adopt it, just as they adopted other standardized and widely used additions to retinal organoid production,” Dr. Li says. “I would like to see it used in everybody’s procedures in the next few years. That would make me very happy.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

References:

[1] Regent F, Batz Z, Kelley RA, Gieser L, Swaroop A, Chen HY, Li T. Nicotinamide Promotes Formation of Retinal Organoids From Human Pluripotent Stem Cells via Enhanced Neural Cell Fate Commitment. Front Cell Neurosci . 2022 Jun 17;16:878351. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2022.878351.

Related Blog Posts

- Experimental Treatment Helps Neurons Recover From Damage

- Pain Research Center Accelerates IRP Pain Studies

- Tiny Molecules Have Big Potential for Treating Eye Diseases

- Postdoc Profile: A Bird’s-Eye View of Retinal Disease

- Non-Toxic Drug Could Increase Availability of Organ Transplants

This page was last updated on Wednesday, May 24, 2023

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- RESEARCH HIGHLIGHT

- 09 May 2024

CRISPR therapy restores some vision to people with blindness

The light-absorbing rods and cones in the retina (artificially coloured) deteriorate in people with Leber’s congenital amaurosis. Credit: Science Photo Library

A CRISPR-based gene-editing therapy led to improved vision in people with an inherited condition that causes blindness 1 .

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Nature 629 , 507 (2024)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-01285-0

Pierce, E. A. et al. N. Engl. J. Med . https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2309915 (2024).

Article Google Scholar

Download references

- Gene therapy

How to kill the ‘zombie’ cells that make you age

News Feature 15 MAY 24

Targeting RNA opens therapeutic avenues for Timothy syndrome

News & Views 24 APR 24

Improving prime editing with an endogenous small RNA-binding protein

Article 03 APR 24

Faculty Positions& Postdoctoral Research Fellow, School of Optical and Electronic Information, HUST

Job Opportunities: Leading talents, young talents, overseas outstanding young scholars, postdoctoral researchers.

Wuhan, Hubei, China

School of Optical and Electronic Information, Huazhong University of Science and Technology

Postdoc in CRISPR Meta-Analytics and AI for Therapeutic Target Discovery and Priotisation (OT Grant)

APPLICATION CLOSING DATE: 14/06/2024 Human Technopole (HT) is a new interdisciplinary life science research institute created and supported by the...

Human Technopole

Research Associate - Metabolism

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Postdoc Fellowships

Train with world-renowned cancer researchers at NIH? Consider joining the Center for Cancer Research (CCR) at the National Cancer Institute

Bethesda, Maryland

NIH National Cancer Institute (NCI)

Faculty Recruitment, Westlake University School of Medicine

Faculty positions are open at four distinct ranks: Assistant Professor, Associate Professor, Full Professor, and Chair Professor.

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Westlake University

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- For Ophthalmologists

- For Practice Management

- For Clinical Teams

- For Public & Patients

Museum of the Eye

- Eye Health A-Z

- Glasses & Contacts

- Tips & Prevention

- Ask an Ophthalmologist

- Patient Stories

- No-Cost Eye Exams

- For Public & Patients /

Stem Cell Therapy for Eye Disease: What You Need to Know

Avoid unlicensed clinics offering unapproved stem cell therapy.

Stem cell therapies are getting headlines for their potential to cure diseases, including those that affect vision. But an important message is missing: the therapies are not yet proven to be safe and effective for your eyes .

Stem cell treatments appear to offer hope to people with few options to recover vision. This includes people with forms of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) , retinitis pigmentosa (RP) , and Stargardt disease . Some clinics across the United States offer "stem-cell therapy" to people outside of clinical trials. But the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved the treatments they offer. These treatments often use unproven products that may be ineffective or dangerous. These products may carry serious risks, including tumor growth.

Ask These Questions If You’re Considering Stem Cell Therapy for Eye Disease

It is important that you know that there are no stem cell products approved by the FDA for eye disease right now. If you want stem cell therapy, look for a clinical trial and discuss the matter with your ophthalmologist. A clinic should not expect you to pay thousands of dollars for an unproven, unapproved therapy. Your health insurance will not cover the cost of an unapproved treatment.

Before agreeing to a stem cell treatment, ask yourself:

- Is the stem cell treatment approved by the FDA?

- Is the stem cell treatment part of an FDA-approved clinical trial?

- Is the stem cell treatment covered by your health insurance?

It is frustrating and frightening to face the loss of vision while waiting for potential treatments. However, choosing to pursue an unproven treatment in an unlicensed clinic is an unacceptable risk to your vision and your overall health.

The American Academy of Ophthalmology wants to reduce or eliminate unlicensed stem cell clinics in the United States. In June 2016, the Academy asked the FDA to tighten regulations and increase investigations into stem cell treatments given outside of clinical trials.

Stem Cells in the News

- Unregulated Stem Cell Treatments Can Be Dangerous

- Stem Cell Treatment for Dry AMD Moves Closer to Human Trials

- Stem Cells May Return Some Vision Lost to Wet AMD

- Could Stem Cells Cure Blindness Caused by Macular Degeneration?

- Will Stem Cell or Gene Therapies Bring Cures for Retinal Diseases?

- Find an Ophthalmologist Search Advanced Search

Free EyeSmart Newsletter

All content on the Academy’s website is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service . This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

- About the Academy

- Jobs at the Academy

- Financial Relationships with Industry

- Medical Disclaimer

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Statement on Artificial Intelligence

- For Advertisers

- Ophthalmology Job Center

FOLLOW THE ACADEMY

Medical Professionals

Public & Patients

- New Treatments for Age-Related Macular Degeneration

- New Treatments for Retinitis Pigmentosa

Cultural Relativity and Acceptance of Embryonic Stem Cell Research

Article sidebar.

Main Article Content

There is a debate about the ethical implications of using human embryos in stem cell research, which can be influenced by cultural, moral, and social values. This paper argues for an adaptable framework to accommodate diverse cultural and religious perspectives. By using an adaptive ethics model, research protections can reflect various populations and foster growth in stem cell research possibilities.

INTRODUCTION

Stem cell research combines biology, medicine, and technology, promising to alter health care and the understanding of human development. Yet, ethical contention exists because of individuals’ perceptions of using human embryos based on their various cultural, moral, and social values. While these disagreements concerning policy, use, and general acceptance have prompted the development of an international ethics policy, such a uniform approach can overlook the nuanced ethical landscapes between cultures. With diverse viewpoints in public health, a single global policy, especially one reflecting Western ethics or the ethics prevalent in high-income countries, is impractical. This paper argues for a culturally sensitive, adaptable framework for the use of embryonic stem cells. Stem cell policy should accommodate varying ethical viewpoints and promote an effective global dialogue. With an extension of an ethics model that can adapt to various cultures, we recommend localized guidelines that reflect the moral views of the people those guidelines serve.

Stem cells, characterized by their unique ability to differentiate into various cell types, enable the repair or replacement of damaged tissues. Two primary types of stem cells are somatic stem cells (adult stem cells) and embryonic stem cells. Adult stem cells exist in developed tissues and maintain the body’s repair processes. [1] Embryonic stem cells (ESC) are remarkably pluripotent or versatile, making them valuable in research. [2] However, the use of ESCs has sparked ethics debates. Considering the potential of embryonic stem cells, research guidelines are essential. The International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) provides international stem cell research guidelines. They call for “public conversations touching on the scientific significance as well as the societal and ethical issues raised by ESC research.” [3] The ISSCR also publishes updates about culturing human embryos 14 days post fertilization, suggesting local policies and regulations should continue to evolve as ESC research develops. [4] Like the ISSCR, which calls for local law and policy to adapt to developing stem cell research given cultural acceptance, this paper highlights the importance of local social factors such as religion and culture.

I. Global Cultural Perspective of Embryonic Stem Cells

Views on ESCs vary throughout the world. Some countries readily embrace stem cell research and therapies, while others have stricter regulations due to ethical concerns surrounding embryonic stem cells and when an embryo becomes entitled to moral consideration. The philosophical issue of when the “someone” begins to be a human after fertilization, in the morally relevant sense, [5] impacts when an embryo becomes not just worthy of protection but morally entitled to it. The process of creating embryonic stem cell lines involves the destruction of the embryos for research. [6] Consequently, global engagement in ESC research depends on social-cultural acceptability.

a. US and Rights-Based Cultures

In the United States, attitudes toward stem cell therapies are diverse. The ethics and social approaches, which value individualism, [7] trigger debates regarding the destruction of human embryos, creating a complex regulatory environment. For example, the 1996 Dickey-Wicker Amendment prohibited federal funding for the creation of embryos for research and the destruction of embryos for “more than allowed for research on fetuses in utero.” [8] Following suit, in 2001, the Bush Administration heavily restricted stem cell lines for research. However, the Stem Cell Research Enhancement Act of 2005 was proposed to help develop ESC research but was ultimately vetoed. [9] Under the Obama administration, in 2009, an executive order lifted restrictions allowing for more development in this field. [10] The flux of research capacity and funding parallels the different cultural perceptions of human dignity of the embryo and how it is socially presented within the country’s research culture. [11]

b. Ubuntu and Collective Cultures

African bioethics differs from Western individualism because of the different traditions and values. African traditions, as described by individuals from South Africa and supported by some studies in other African countries, including Ghana and Kenya, follow the African moral philosophies of Ubuntu or Botho and Ukama , which “advocates for a form of wholeness that comes through one’s relationship and connectedness with other people in the society,” [12] making autonomy a socially collective concept. In this context, for the community to act autonomously, individuals would come together to decide what is best for the collective. Thus, stem cell research would require examining the value of the research to society as a whole and the use of the embryos as a collective societal resource. If society views the source as part of the collective whole, and opposes using stem cells, compromising the cultural values to pursue research may cause social detachment and stunt research growth. [13] Based on local culture and moral philosophy, the permissibility of stem cell research depends on how embryo, stem cell, and cell line therapies relate to the community as a whole . Ubuntu is the expression of humanness, with the person’s identity drawn from the “’I am because we are’” value. [14] The decision in a collectivistic culture becomes one born of cultural context, and individual decisions give deference to others in the society.

Consent differs in cultures where thought and moral philosophy are based on a collective paradigm. So, applying Western bioethical concepts is unrealistic. For one, Africa is a diverse continent with many countries with different belief systems, access to health care, and reliance on traditional or Western medicines. Where traditional medicine is the primary treatment, the “’restrictive focus on biomedically-related bioethics’” [is] problematic in African contexts because it neglects bioethical issues raised by traditional systems.” [15] No single approach applies in all areas or contexts. Rather than evaluating the permissibility of ESC research according to Western concepts such as the four principles approach, different ethics approaches should prevail.

Another consideration is the socio-economic standing of countries. In parts of South Africa, researchers have not focused heavily on contributing to the stem cell discourse, either because it is not considered health care or a health science priority or because resources are unavailable. [16] Each country’s priorities differ given different social, political, and economic factors. In South Africa, for instance, areas such as maternal mortality, non-communicable diseases, telemedicine, and the strength of health systems need improvement and require more focus. [17] Stem cell research could benefit the population, but it also could divert resources from basic medical care. Researchers in South Africa adhere to the National Health Act and Medicines Control Act in South Africa and international guidelines; however, the Act is not strictly enforced, and there is no clear legislation for research conduct or ethical guidelines. [18]

Some parts of Africa condemn stem cell research. For example, 98.2 percent of the Tunisian population is Muslim. [19] Tunisia does not permit stem cell research because of moral conflict with a Fatwa. Religion heavily saturates the regulation and direction of research. [20] Stem cell use became permissible for reproductive purposes only recently, with tight restrictions preventing cells from being used in any research other than procedures concerning ART/IVF. Their use is conditioned on consent, and available only to married couples. [21] The community's receptiveness to stem cell research depends on including communitarian African ethics.

c. Asia

Some Asian countries also have a collective model of ethics and decision making. [22] In China, the ethics model promotes a sincere respect for life or human dignity, [23] based on protective medicine. This model, influenced by Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), [24] recognizes Qi as the vital energy delivered via the meridians of the body; it connects illness to body systems, the body’s entire constitution, and the universe for a holistic bond of nature, health, and quality of life. [25] Following a protective ethics model, and traditional customs of wholeness, investment in stem cell research is heavily desired for its applications in regenerative therapies, disease modeling, and protective medicines. In a survey of medical students and healthcare practitioners, 30.8 percent considered stem cell research morally unacceptable while 63.5 percent accepted medical research using human embryonic stem cells. Of these individuals, 89.9 percent supported increased funding for stem cell research. [26] The scientific community might not reflect the overall population. From 1997 to 2019, China spent a total of $576 million (USD) on stem cell research at 8,050 stem cell programs, increased published presence from 0.6 percent to 14.01 percent of total global stem cell publications as of 2014, and made significant strides in cell-based therapies for various medical conditions. [27] However, while China has made substantial investments in stem cell research and achieved notable progress in clinical applications, concerns linger regarding ethical oversight and transparency. [28] For example, the China Biosecurity Law, promoted by the National Health Commission and China Hospital Association, attempted to mitigate risks by introducing an institutional review board (IRB) in the regulatory bodies. 5800 IRBs registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry since 2021. [29] However, issues still need to be addressed in implementing effective IRB review and approval procedures.

The substantial government funding and focus on scientific advancement have sometimes overshadowed considerations of regional cultures, ethnic minorities, and individual perspectives, particularly evident during the one-child policy era. As government policy adapts to promote public stability, such as the change from the one-child to the two-child policy, [30] research ethics should also adapt to ensure respect for the values of its represented peoples.

Japan is also relatively supportive of stem cell research and therapies. Japan has a more transparent regulatory framework, allowing for faster approval of regenerative medicine products, which has led to several advanced clinical trials and therapies. [31] South Korea is also actively engaged in stem cell research and has a history of breakthroughs in cloning and embryonic stem cells. [32] However, the field is controversial, and there are issues of scientific integrity. For example, the Korean FDA fast-tracked products for approval, [33] and in another instance, the oocyte source was unclear and possibly violated ethical standards. [34] Trust is important in research, as it builds collaborative foundations between colleagues, trial participant comfort, open-mindedness for complicated and sensitive discussions, and supports regulatory procedures for stakeholders. There is a need to respect the culture’s interest, engagement, and for research and clinical trials to be transparent and have ethical oversight to promote global research discourse and trust.

d. Middle East

Countries in the Middle East have varying degrees of acceptance of or restrictions to policies related to using embryonic stem cells due to cultural and religious influences. Saudi Arabia has made significant contributions to stem cell research, and conducts research based on international guidelines for ethical conduct and under strict adherence to guidelines in accordance with Islamic principles. Specifically, the Saudi government and people require ESC research to adhere to Sharia law. In addition to umbilical and placental stem cells, [35] Saudi Arabia permits the use of embryonic stem cells as long as they come from miscarriages, therapeutic abortions permissible by Sharia law, or are left over from in vitro fertilization and donated to research. [36] Laws and ethical guidelines for stem cell research allow the development of research institutions such as the King Abdullah International Medical Research Center, which has a cord blood bank and a stem cell registry with nearly 10,000 donors. [37] Such volume and acceptance are due to the ethical ‘permissibility’ of the donor sources, which do not conflict with religious pillars. However, some researchers err on the side of caution, choosing not to use embryos or fetal tissue as they feel it is unethical to do so. [38]

Jordan has a positive research ethics culture. [39] However, there is a significant issue of lack of trust in researchers, with 45.23 percent (38.66 percent agreeing and 6.57 percent strongly agreeing) of Jordanians holding a low level of trust in researchers, compared to 81.34 percent of Jordanians agreeing that they feel safe to participate in a research trial. [40] Safety testifies to the feeling of confidence that adequate measures are in place to protect participants from harm, whereas trust in researchers could represent the confidence in researchers to act in the participants’ best interests, adhere to ethical guidelines, provide accurate information, and respect participants’ rights and dignity. One method to improve trust would be to address communication issues relevant to ESC. Legislation surrounding stem cell research has adopted specific language, especially concerning clarification “between ‘stem cells’ and ‘embryonic stem cells’” in translation. [41] Furthermore, legislation “mandates the creation of a national committee… laying out specific regulations for stem-cell banking in accordance with international standards.” [42] This broad regulation opens the door for future global engagement and maintains transparency. However, these regulations may also constrain the influence of research direction, pace, and accessibility of research outcomes.

e. Europe

In the European Union (EU), ethics is also principle-based, but the principles of autonomy, dignity, integrity, and vulnerability are interconnected. [43] As such, the opportunity for cohesion and concessions between individuals’ thoughts and ideals allows for a more adaptable ethics model due to the flexible principles that relate to the human experience The EU has put forth a framework in its Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being allowing member states to take different approaches. Each European state applies these principles to its specific conventions, leading to or reflecting different acceptance levels of stem cell research. [44]

For example, in Germany, Lebenzusammenhang , or the coherence of life, references integrity in the unity of human culture. Namely, the personal sphere “should not be subject to external intervention.” [45] Stem cell interventions could affect this concept of bodily completeness, leading to heavy restrictions. Under the Grundgesetz, human dignity and the right to life with physical integrity are paramount. [46] The Embryo Protection Act of 1991 made producing cell lines illegal. Cell lines can be imported if approved by the Central Ethics Commission for Stem Cell Research only if they were derived before May 2007. [47] Stem cell research respects the integrity of life for the embryo with heavy specifications and intense oversight. This is vastly different in Finland, where the regulatory bodies find research more permissible in IVF excess, but only up to 14 days after fertilization. [48] Spain’s approach differs still, with a comprehensive regulatory framework. [49] Thus, research regulation can be culture-specific due to variations in applied principles. Diverse cultures call for various approaches to ethical permissibility. [50] Only an adaptive-deliberative model can address the cultural constructions of self and achieve positive, culturally sensitive stem cell research practices. [51]

II. Religious Perspectives on ESC

Embryonic stem cell sources are the main consideration within religious contexts. While individuals may not regard their own religious texts as authoritative or factual, religion can shape their foundations or perspectives.

The Qur'an states:

“And indeed We created man from a quintessence of clay. Then We placed within him a small quantity of nutfa (sperm to fertilize) in a safe place. Then We have fashioned the nutfa into an ‘alaqa (clinging clot or cell cluster), then We developed the ‘alaqa into mudgha (a lump of flesh), and We made mudgha into bones, and clothed the bones with flesh, then We brought it into being as a new creation. So Blessed is Allah, the Best of Creators.” [52]

Many scholars of Islam estimate the time of soul installment, marked by the angel breathing in the soul to bring the individual into creation, as 120 days from conception. [53] Personhood begins at this point, and the value of life would prohibit research or experimentation that could harm the individual. If the fetus is more than 120 days old, the time ensoulment is interpreted to occur according to Islamic law, abortion is no longer permissible. [54] There are a few opposing opinions about early embryos in Islamic traditions. According to some Islamic theologians, there is no ensoulment of the early embryo, which is the source of stem cells for ESC research. [55]

In Buddhism, the stance on stem cell research is not settled. The main tenets, the prohibition against harming or destroying others (ahimsa) and the pursuit of knowledge (prajña) and compassion (karuna), leave Buddhist scholars and communities divided. [56] Some scholars argue stem cell research is in accordance with the Buddhist tenet of seeking knowledge and ending human suffering. Others feel it violates the principle of not harming others. Finding the balance between these two points relies on the karmic burden of Buddhist morality. In trying to prevent ahimsa towards the embryo, Buddhist scholars suggest that to comply with Buddhist tenets, research cannot be done as the embryo has personhood at the moment of conception and would reincarnate immediately, harming the individual's ability to build their karmic burden. [57] On the other hand, the Bodhisattvas, those considered to be on the path to enlightenment or Nirvana, have given organs and flesh to others to help alleviate grieving and to benefit all. [58] Acceptance varies on applied beliefs and interpretations.

Catholicism does not support embryonic stem cell research, as it entails creation or destruction of human embryos. This destruction conflicts with the belief in the sanctity of life. For example, in the Old Testament, Genesis describes humanity as being created in God’s image and multiplying on the Earth, referencing the sacred rights to human conception and the purpose of development and life. In the Ten Commandments, the tenet that one should not kill has numerous interpretations where killing could mean murder or shedding of the sanctity of life, demonstrating the high value of human personhood. In other books, the theological conception of when life begins is interpreted as in utero, [59] highlighting the inviolability of life and its formation in vivo to make a religious point for accepting such research as relatively limited, if at all. [60] The Vatican has released ethical directives to help apply a theological basis to modern-day conflicts. The Magisterium of the Church states that “unless there is a moral certainty of not causing harm,” experimentation on fetuses, fertilized cells, stem cells, or embryos constitutes a crime. [61] Such procedures would not respect the human person who exists at these stages, according to Catholicism. Damages to the embryo are considered gravely immoral and illicit. [62] Although the Catholic Church officially opposes abortion, surveys demonstrate that many Catholic people hold pro-choice views, whether due to the context of conception, stage of pregnancy, threat to the mother’s life, or for other reasons, demonstrating that practicing members can also accept some but not all tenets. [63]

Some major Jewish denominations, such as the Reform, Conservative, and Reconstructionist movements, are open to supporting ESC use or research as long as it is for saving a life. [64] Within Judaism, the Talmud, or study, gives personhood to the child at birth and emphasizes that life does not begin at conception: [65]

“If she is found pregnant, until the fortieth day it is mere fluid,” [66]

Whereas most religions prioritize the status of human embryos, the Halakah (Jewish religious law) states that to save one life, most other religious laws can be ignored because it is in pursuit of preservation. [67] Stem cell research is accepted due to application of these religious laws.

We recognize that all religions contain subsets and sects. The variety of environmental and cultural differences within religious groups requires further analysis to respect the flexibility of religious thoughts and practices. We make no presumptions that all cultures require notions of autonomy or morality as under the common morality theory , which asserts a set of universal moral norms that all individuals share provides moral reasoning and guides ethical decisions. [68] We only wish to show that the interaction with morality varies between cultures and countries.

III. A Flexible Ethical Approach

The plurality of different moral approaches described above demonstrates that there can be no universally acceptable uniform law for ESC on a global scale. Instead of developing one standard, flexible ethical applications must be continued. We recommend local guidelines that incorporate important cultural and ethical priorities.

While the Declaration of Helsinki is more relevant to people in clinical trials receiving ESC products, in keeping with the tradition of protections for research subjects, consent of the donor is an ethical requirement for ESC donation in many jurisdictions including the US, Canada, and Europe. [69] The Declaration of Helsinki provides a reference point for regulatory standards and could potentially be used as a universal baseline for obtaining consent prior to gamete or embryo donation.

For instance, in Columbia University’s egg donor program for stem cell research, donors followed standard screening protocols and “underwent counseling sessions that included information as to the purpose of oocyte donation for research, what the oocytes would be used for, the risks and benefits of donation, and process of oocyte stimulation” to ensure transparency for consent. [70] The program helped advance stem cell research and provided clear and safe research methods with paid participants. Though paid participation or covering costs of incidental expenses may not be socially acceptable in every culture or context, [71] and creating embryos for ESC research is illegal in many jurisdictions, Columbia’s program was effective because of the clear and honest communications with donors, IRBs, and related stakeholders. This example demonstrates that cultural acceptance of scientific research and of the idea that an egg or embryo does not have personhood is likely behind societal acceptance of donating eggs for ESC research. As noted, many countries do not permit the creation of embryos for research.

Proper communication and education regarding the process and purpose of stem cell research may bolster comprehension and garner more acceptance. “Given the sensitive subject material, a complete consent process can support voluntary participation through trust, understanding, and ethical norms from the cultures and morals participants value. This can be hard for researchers entering countries of different socioeconomic stability, with different languages and different societal values. [72]

An adequate moral foundation in medical ethics is derived from the cultural and religious basis that informs knowledge and actions. [73] Understanding local cultural and religious values and their impact on research could help researchers develop humility and promote inclusion.

IV. Concerns

Some may argue that if researchers all adhere to one ethics standard, protection will be satisfied across all borders, and the global public will trust researchers. However, defining what needs to be protected and how to define such research standards is very specific to the people to which standards are applied. We suggest that applying one uniform guide cannot accurately protect each individual because we all possess our own perceptions and interpretations of social values. [74] Therefore, the issue of not adjusting to the moral pluralism between peoples in applying one standard of ethics can be resolved by building out ethics models that can be adapted to different cultures and religions.

Other concerns include medical tourism, which may promote health inequities. [75] Some countries may develop and approve products derived from ESC research before others, compromising research ethics or drug approval processes. There are also concerns about the sale of unauthorized stem cell treatments, for example, those without FDA approval in the United States. Countries with robust research infrastructures may be tempted to attract medical tourists, and some customers will have false hopes based on aggressive publicity of unproven treatments. [76]

For example, in China, stem cell clinics can market to foreign clients who are not protected under the regulatory regimes. Companies employ a marketing strategy of “ethically friendly” therapies. Specifically, in the case of Beike, China’s leading stem cell tourism company and sprouting network, ethical oversight of administrators or health bureaus at one site has “the unintended consequence of shifting questionable activities to another node in Beike's diffuse network.” [77] In contrast, Jordan is aware of stem cell research’s potential abuse and its own status as a “health-care hub.” Jordan’s expanded regulations include preserving the interests of individuals in clinical trials and banning private companies from ESC research to preserve transparency and the integrity of research practices. [78]

The social priorities of the community are also a concern. The ISSCR explicitly states that guidelines “should be periodically revised to accommodate scientific advances, new challenges, and evolving social priorities.” [79] The adaptable ethics model extends this consideration further by addressing whether research is warranted given the varying degrees of socioeconomic conditions, political stability, and healthcare accessibilities and limitations. An ethical approach would require discussion about resource allocation and appropriate distribution of funds. [80]