Problem Solving Wheel: Help Kids Solve Their Own Problems

Students who act out in aggressive behaviors often do so because they struggle with identifying solutions to their problems. A Problem-Solving Wheel can help teach your students to learn how to independently solve a problem.

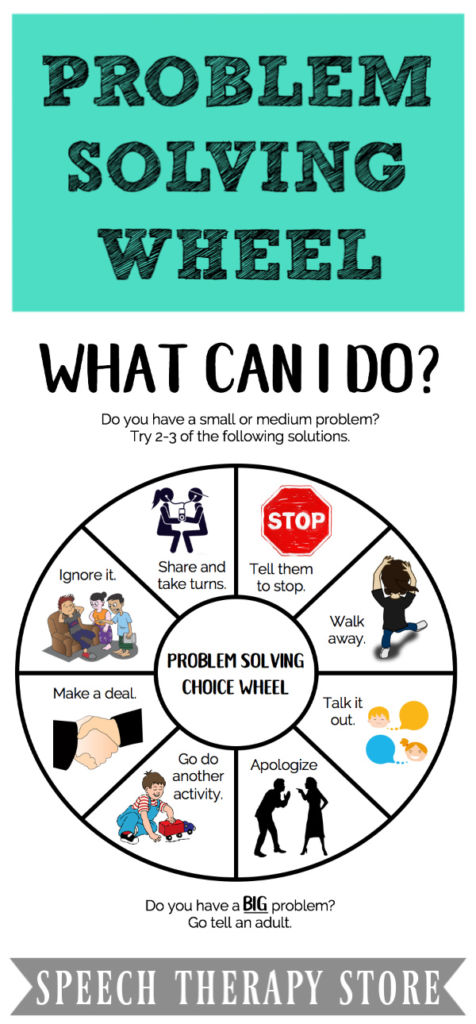

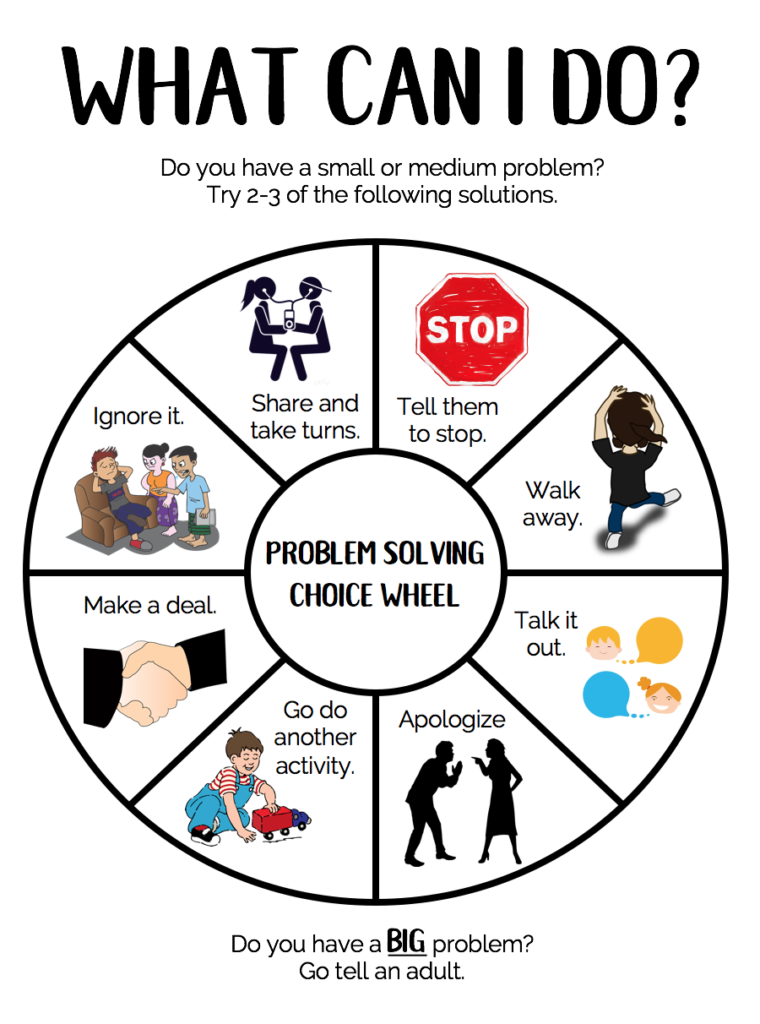

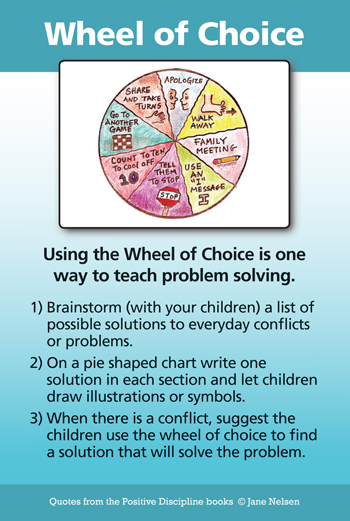

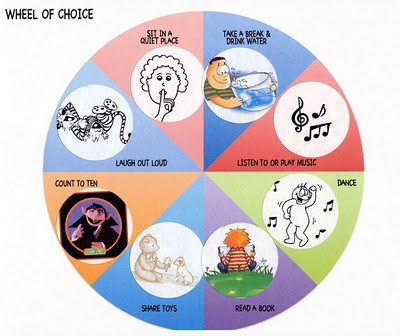

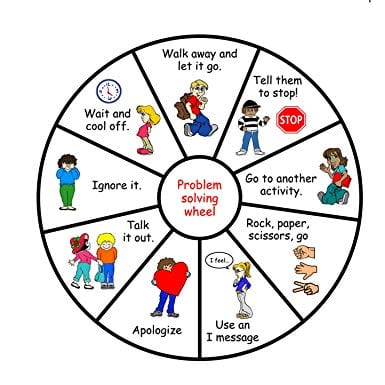

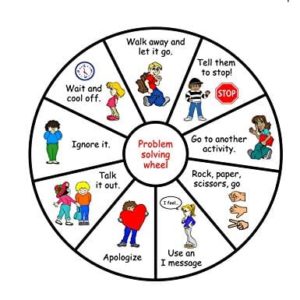

A problem-solving wheel also known as the wheel of choice or solution wheel is a great way to give students a visual of choices to help them either calm down when they are upset or to help them solve a problem with a classmate.

It is best to use the problem-solving wheel when students are dealing with a “small” problem. “Small” problems include conflicts that cause “small” feelings of annoyance, embarrassment, boredom, etc. If the student has a BIG problem they should practice telling an adult. “BIG problems” are situations that are scary, dangerous, illegal, etc.

Examples of Small Problems

- A classmate broke your pencil

- Someone cut in front of them in line

- A classmate is using the color crayon they want to use

- A friend keeps kicking their chair

Conflict Resolution

Children don’t always know what to do when they are experiencing conflicts with others. When students are stressed and in the moment of a conflict they can often forget how to solve the problem A problem-solving choice wheel can help them learn different ways to solve their problems. I’ve created a few free printable problem-solving choice wheels for you to choose from. Simply download and start using in your classroom today!

Problem Solving Wheel Freebie

Comes in 4 different versions:

- Ready-Made: “What can I do?” choice wheel is ready to use right away. Simply download, print and start using this freebie!

- Blank with Pictures: Have your students add their own words to the pictures.

- Blank: Have your students draw their own pictures and write a short description.

- Editable Version: Using the free version of Adobe Acrobat Reader edit all the blue boxes with your own words.

When you create a consistent pattern of how to solve problems students will eventually pick up on that pattern and begin to implement the pattern independently.

Send me the Problem Solving Choice Wheel!

Involve children in finding the solution..

Involving children in the problem-solving process can help give them buy-in into using the system that they take part in creating. Use the blank version or the editable version and have your students create their own ideas for how to solve “small” problems on their own. Your students might even surprise you and come up with some creative solutions.

Teach Feeling Words

In addition, for some of our students teaching feeling words can help them have the vocabulary necessary to express how they are feeling during a problem. We can start by naming students’ feelings for them and after some practice hopefully, the students will begin to use feeling words to describe how they are feeling during a conflict. For example, “Sam the way you yelled, “no” and stomped your feet tell me that you are angry.” Talking to our students this way can help bring their attention to their feelings so they can eventually identify their own feelings.

Help your students resolve a social conflict on their own with this – PROBLEM-SOLVING WHEEL .

Where to Begin

- Start by posting the PROBLEM-SOLVING WHEEL in a good spot in your classroom or office.

- Start slowly and use 1-2 solutions and build up to using all 6 solutions.

- Practice, practice, practice!

Helpful Tips

- Start slowly: practice using 1-2 choices at a time and slowly build up to using all six. Be clear about what each choice looks like in practice.

- Practice is critical: Even after introducing the Problem-Solving Wheel students will still depend on you to help them resolve their conflicts. Continue to modal and have your students practice.

Books on Problem Solving

For Younger Children: Recommended Ages 2-6

- The Little Mouse, The Red Ripe Strawberry, and the Big Hungry Bear

- Duncan the Story Dragon

- The Whale in my Swimming Pool

For Older Children: Recommended Ages 8-12

- Appleblossom the Possum

- Dough Knights and Dragons

- Rosie Revere, Engineer

Aggressive behaviors are often exhibited when a student struggles with identifying solutions to their problems. A problem-solving wheel can be a great way to give students a visual of choices to help them calm down and to solve a problem with a classmate or friend.

Grab your freebie printable today and get started helping your students independently solving their own problems!

Want More Problem Solving?

Be sure to check out my other problem-solving freebies:

- 31 Wordless Videos to Teach Problem-Solving

- 71+ Free Social Problem Solving Task Cards Scenarios

Get More Problem Solving Time Saving Materials

Next, be sure to check out the following time-saving materials to continue to teach your students how to solve their social problems in addition to this freebie.

Problem Size & Reaction Size

- Problem size and reaction size. Teach your students to identify the size of a problem and to match the size of the problem with their reaction size.

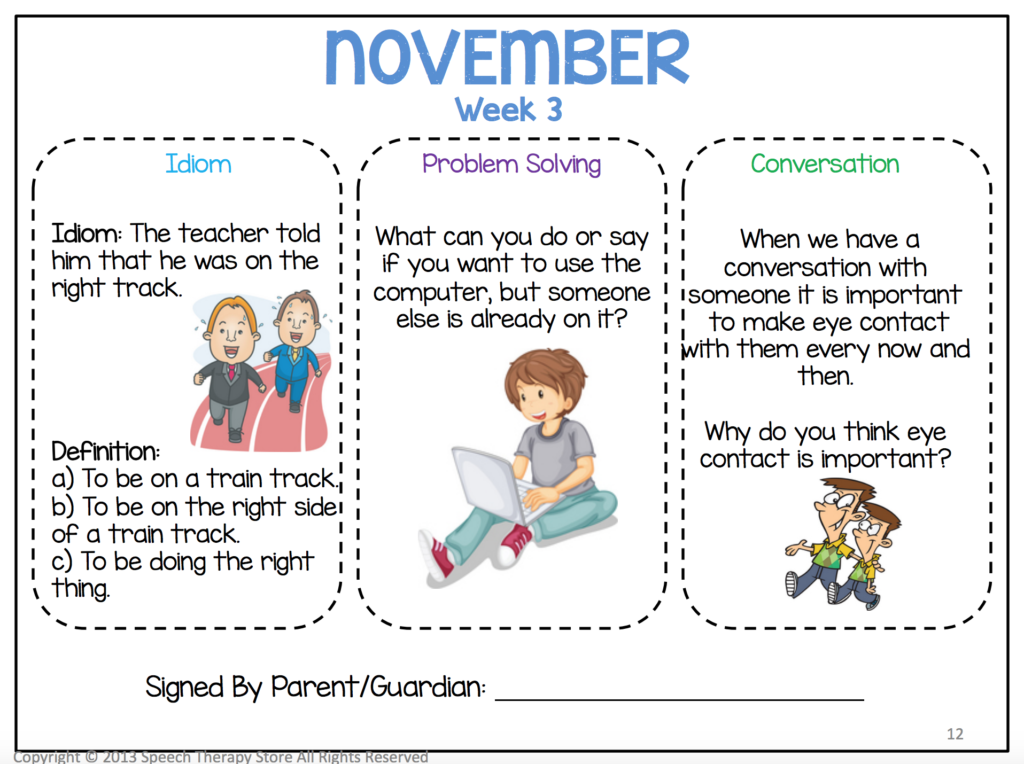

Weekly Social Pragmatics Homework

- Weekly problem-solving. Send home a weekly homework page that includes a problem-solving scenario plus an idiom and a conversational practice scenario.

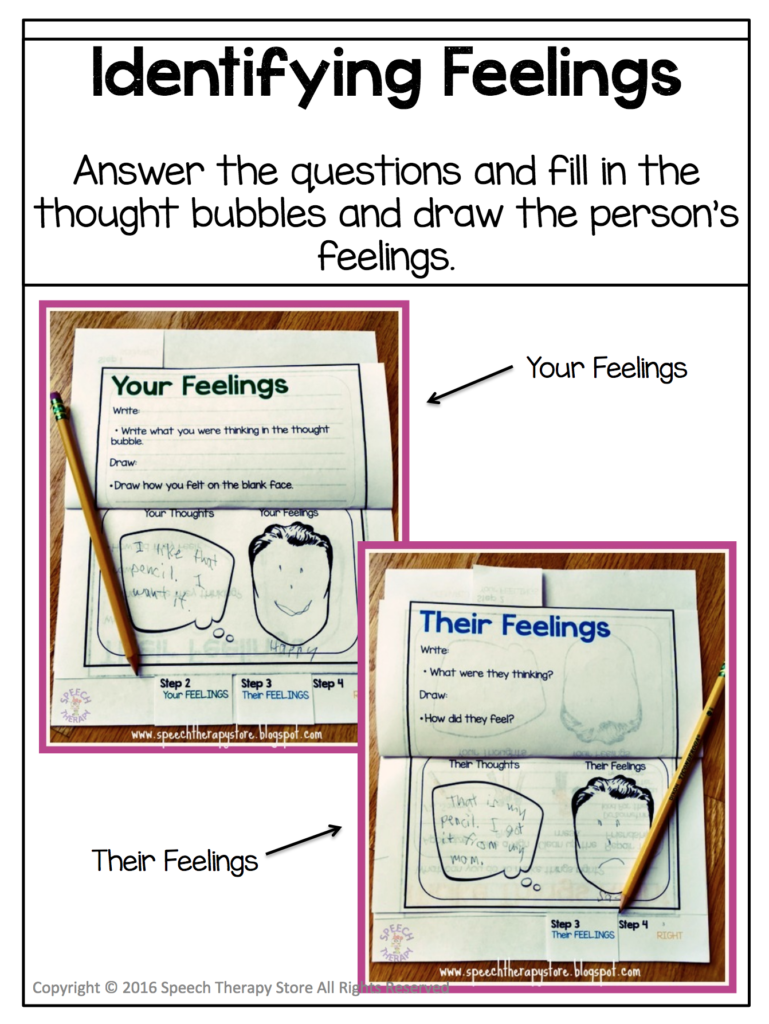

Restorative Justice Problem Solving Flip Book

- Restorative justice graphic visual. Use this graphic visual to help your student restore a social relationship after a social problem.

Thursday 2nd of February 2023

Great idea!

71+ Free Social Problem-Solving Scenarios - Speech Therapy Store

Wednesday 23rd of October 2019

[…] with these small problems can be a great learning opportunity. Children can practice problem-solving with a small problem which can help them learn how to handle bigger problems in the […]

Problem Solving Wheel – What can I do?

- Post author By Hugo

- Post date 25 November 2017

What can I do?

Problem solving wheel

- Walk away and let it go

- Tell them to stop

- Go to another activity

- Rock, paper, scissors, go

- Use and I statement – I feel…

- Talk it out

- Wait and cool off

Search form

Customer Service 1-800-456-7770

The Wheel of Choice

Sign Up for Our Newsletter

Focusing on solutions is a primary theme of Positive Discipline, and kids are great at focusing on solutions when they are taught the skills and are allowed to practice them.

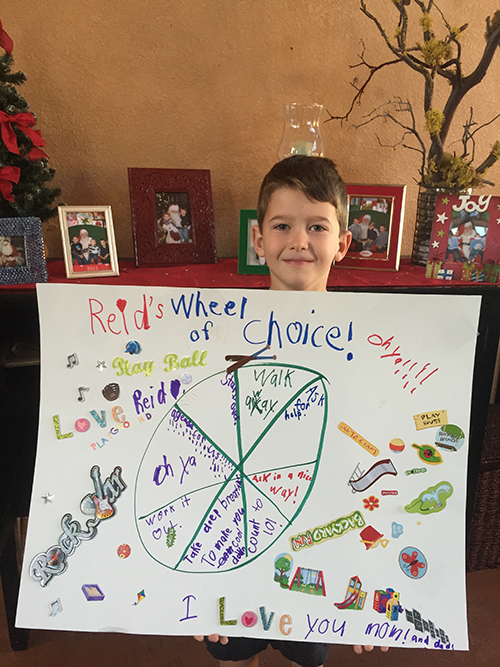

The wheel of choice provides a fun and exciting way to involve kids in learning and practicing problem-solving skills, especially when they are involved in creating it.

Make sure your child takes the primary lead in creating his or her wheel of choice. The less you do, the better. Your child can be creative and decide if he or she would like to draw pictures or symbols to represent solutions, or to find pictures on the Internet. Then let your child choose (within reason) where to hang his or her wheel of choice.

Older kids may not want to create a wheel, but could benefit from brainstorming ideas for focusing on solutions and writing them down on an easily accessible list. It is helpful when you have other options for finding solutions, such as family meetings. Then you can offer a choice: “What would help you the most right now—your wheel of choice or putting this problem on the family meeting agenda?”

Helping your child create a wheel of choice increases his or her sense of capability and self-regulation. From Mary’s story you will gain a sense of why it is best to have your kids make their own wheel of choice from scratch instead of using a template.

Success Story

The following Wheel of Choice was created by 3-year-old Jake with the help of his mom, Laura Beth. Jake chose the clip art he wanted to represent some choices. His Mom, shared the following success story.

Jake used his Wheel of Choice today. Jake and his sister (17 months old) were sitting on the sofa sharing a book. His sister, took the book and Jake immediately flipped his lid. He yelled at her, grabbed the book, made her cry. She grabbed it back and I slowly walked in. I asked Jake if he’d like to use his Wheel Of Choice to help—and he actually said YES! He chose to “share his toys.” He got his sister her own book that was more appropriate for her and she gladly gave him his book back. They sat there for a while and then traded!

by Mary Tamborski , co-author of Positive Discipline Parenting Tools

It was such fun creating a wheel of choice with my son Reid when he was 7 years old. We purchased a few supplies in advance: poster board, stickers, scented markers, scissors, and colored paper. None of these materials are required, but I knew it would make it more fun.

It turned out to be even more of an advantage than I thought because his 3-year-old brother, Parker, wanted to be involved too. He had fun making his own wheel of choice (even though he didn’t really under- stand it). This was a great distraction for Reid’s little brother, who felt like he was involved in the process.

I started by asking Reid, “What are some of the things you do or can do when you are having a challenge?”

I was really impressed with how easy it was for Reid to come up with so many solutions. He had already been using many of these skills, so he created his list very quickly.

- Walk away or go to a different room.

- Take deep breaths.

- Put it on the family meeting agenda.

- Use a different tone.

- Ask Mom or Dad for help.

- Count to ten to cool off.

- Hit the “reset button” and try again.

He had fun writing them all on his pie graph. The scented pens added to his enthusiasm. He wanted to “practice” writing them on a piece of scratch paper before he officially drew them on his poster board.

I loved how he handled it when he misspelled a word or when his circle wasn’t even. He just crossed out the word and rewrote it. I was tempted to give my two cents and step in to fix it for him, but I remembered how important it was for him to do it by himself. I could see the pride in his grin and his little happy dance movement in his chair. I was relieved when Reid patiently allowed his little brother to be involved by adding stickers to his finished project.

Reid was so proud when he held up his wheel of choice. Even Parker was proud. They were both posing for a photo, and Reid even wanted me to take a video as he described it.

About two hours later he had his first challenge: his older brother, Greyson, was saying, “Reid smells like a fart.” Then he started mimicking everything Reid said.

Reid came to me and said, “Greyson keeps bugging me.”

I said, “You’re having a challenging moment. Would it help you to go to your wheel of choice to choose something you could do?”

He went to his wheel of choice, looked at it, and did his own little process of elimination. He said, “I’ve already walked away and he keeps following me.

I’m asking you for help.”

I asked, “What else could you try?”

Reid started taking deep breaths. Then he said, “I’m going to try asking him in a calm voice to please stop, and lie on the bed while you read us a book.”

Before I could even fully process this magical moment, all three boys were lying next to me while we read a book.

One of the most valuable lessons I learned was that he had the tools and skills to solve his problems on his own. Knowing that he had his wheel of choice reminded me to not get involved in solving the problem. After all, getting me involved wasn’t one of his “solutions.” (Yes, asking me for help was one of his solutions, and I used my judgment to know he could find something that didn’t involve me. If he had been in physical danger I would have helped.)

Click Here to view the Wheel of Choice from a program created by Lynn Lott and Jane Nelsen (illustrations by Paula Gray).

Click Here to get a more complete description and to order your own Wheel of Choice: A Problem Solving Program . It includes 14 lessons to teach the skills for using the Wheel of Choice.

- Log in to post comments

Online Learning

Positive Discipline offers online learning options for parents, teachers, and parent educators. Learn in the comfort of your own home and at your own pace. You have unlimited access to our online streaming programs, so you can watch and re-watch the videos as often as you like.

Classroom Management Toolbox

Eastern Washington University

Problem Solving Wheel

The “Problem Solving Wheel” has many options the student can choose from such as, walk away and let it go, apologize, tell them to stop, ignore it, talk it out, and wait and cool off. Having this tool in the classroom helps minimize the fighting and arguing in the younger grade classes. It helps with giving different options that the students can choose from to handle their difficult situations themselves. For example if a student is constantly taking their classmates scissors or school supplies without asking, their behavior needs to be corrected. They can do this by going to the wheel and choosing the best option to help them make the situation better. In this case it would be to apologize to the other student who they were taking supplies from without permission.

More Information – Tool Source: Pinterest

1 thought on “Problem Solving Wheel”

I am placed in a first-grade classroom with 21 students in a suburban neighborhood. I prepared this tool by finding a wheel of choice that fit my grade level and included age-appropriate choices. I printed three copies of the wheels, laminated them, and stapled them around the room at eye level for students. I introduced the wheel at carpet time with the students, explained each choice on the wheel, and gave examples of what each one would look like in use. Since the wheels have been posted, some students have been referencing the wheel when needed and I have noticed a decrease in escalated conflicts among students. Students understand how the wheel is used and that it is their responsibility to pick a choice that is most appropriate for the situation. An adjustment that could be made to make this tool more effective would be creating a wheel of choice from scratch in collaboration with the students in your class.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Campus Safety

509.359.6498 Office

509.359.6498 Cheney

509.359.6498 Spokane

Records & Registration

509.359.2321

Need Tech Assistance?

509.359.2247

EWU ACCESSIBILITY

509.359.6871

EWU Accessibility

Student Affairs

509.359.7924

University Housing

509.359.2451

Housing & Residential Life

Register to Vote

Register to Vote (RCW 29A.08.310)

509.359.6200

© 2023 INSIDE.EWU.EDU

Insights from an Educational Psychologist and mom

- Books and Resources

- About Melissa

- K&M Center

- Privacy Policy

Flexible Thinking Wonder Wheel: Guide your child’s thinking

Flexible thinking and problem solving are key components of learning. We are constantly presented with questions needing an answer. “What time do we need to leave to make it to school on time? “ How cold will it be tomorrow?” “ Who is picking me up today?” Whether the question is big or little, important or trivial, it needs to be answered. Teaching our children to analyze information and find solutions to the problems they face is a critical skill.

Children start out as Concrete Thinkers .

Concrete thinkers learn new information by memorizing it. Learning to memorize facts, decode words, and write letters/numbers is the first level of academic learning. Practicing rote facts and skills until they become automatic allows children to advance to the next stage of learning where they start developing higher order thinking skills. Now the child can extend previously learned rote information to create associations and novel solutions.

How do concrete thinkers learn to think flexibly?

Transitioning from concrete thinking to flexible thinking is automatic for many children, but others need guidance and support to make the transition. Since concrete thinkers see the world as black and white, ideas become fixed in their mind as final and complete. When asked to reconsider or alter an idea in any way, concrete thinkers often become resistant. Lacking strategies to think flexibly these children hold tight to the idea they have.

Helping children understand that there is another way to think is a good first step to teaching children to think flexibly.

Teach two types of thinking: crystalized and fluid.

Exploring the concept of solid and fluid and comparing it to your child’s thinking skills can help them understand that there are many ways of thinking.

Crystalized intelligence is often compared to an ice cube, where the knowledge is frozen and stored in long-term memory for later use.

Examples: Learning math facts or vocabulary words.

Fluid intelligence is compared to flowing water, where the knowledge can easily adapt to any changes it encounters.

Examples: Figuring out how to do a new math problem or solve a puzzle.

Demonstrate that there can be more than one right answer to a problem.

Introduce your child to the idea that there can be multiple solutions to a problem to start the process of flexible thinking. Discuss that switching from crystalized to fluid thinking will allow new ideas to develop and lead to novel solutions.

Many children’s first response to a problem is to pick one response and stick with it. So it is critical for children to learn how to inhibit their first response and stay open to finding other solutions. Creating metacognitive strategies will help guide your child to create multiple options and facilitate flexible thinking.

Metacognition is thinking about thinking.

Modeling metacognition is the best way to teach it. You will be instrumental in guiding your child through the metacognitive questioning process to discover solutions. The goal is to offer enough external guidance and practice that your child is able to internalize the process and is able to create solutions on her own.

The best way to begin modeling metacognitive thinking is to pay attention to the questions you ask yourself.

What is your internal dialog when you solve problems? As adults much of our internal dialog is unconscious, becoming aware your problem solving process will allow you to understand what you are trying to teach your child. Verbalizing each thought you consider on your way to solving problems will provide your child with a demonstration of a problem-solving model.

- Let’s see what we already have. We have chicken, beans and some rice. Great, I will make roasted chicken with steamed beans and rice.

- Well, we want to eat at 6:00, the chicken cooks 40 minutes, the rice takes 20 minutes and the beans need 10 minutes.

- So I have to put the chicken in the oven at 5:20, the rice in at 5:40 and the beans on at 5:50.

- I will set the timer to remind me to start dinner at 5:15”

We are constantly asking and answering questions to solve our everyday problems. Allowing our children to see this process will help them realize that active thinking and problem solving is a normal part of everyday life.

Use the Flexible Thinking Wonder Wheel

The Flexible Thinking Wonder Wheel helps children begin to wonder about how to approach and solve problems.

Start the Flexible Thinking Wonder Wheel with a clear understanding of what the problem is.

Leo takes too long to get ready in the morning, making the morning routine stressful for everyone in the house. Every morning he is woken up at 7:00 which should give him plenty of time to eat breakfast and get dressed, but somehow he stretches out the process so that at 8:00 when it is time to leave he isn’t ready.

Create a signal that indicates it is time to let go of what you and your child are doing so you can begin the Wondering process. This can be something as simple as blinking 2 times or clapping your hands. The idea is that you let go of whatever you are thinking to begin the Wondering process.

Start the WONDERING process with metacognitive questions to understand the problem. “ I wonder how I can get to ready for school on time.”

..why I am doing this?

..what this will look like when I am done?

..how long does it take to do everything in the morning?

…is this more or less time than I have now?

Answer as many questions as you can and then start the next stage of the wondering process.

Start thinking of solutions

Option 1: I can time each activity in the morning to find out where the time is being spent and then adjust the schedule as needed.

Option 2: I can set a timer to make sure each activity takes only as long as indicated.

Option 3: I can get up earlier and not worry about how long each activity is taking.

Pick which solution to try first.

If the first solution doesn’t work, don’t give up, just go on and try the next one.

Continue on until you find a solution.

The Flexible Thinking Wonder Wheel enables you, as the parent, to guide your child towards active problem-solving. Like a wheel that goes around many times to reach a destination, you will use this wheel many times to get to your destination: flexible thinking. Mastering this process requires practice and repetition.

Learning the keywords, Stop, Wonder, Act, Don’t Give Up, to guide you and your child through the strategy of identifying the problem, breaking it down to understand it, creating possible solutions and then trying each solution until you find the one that works helps guide you through the process.

Share this:

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

[…] in a timely manner, Todd is unable to do so without getting upset. I introduced Sarah to the Wonder Wheel of Thinking as a tool to help guide Todd toward a new approach to his […]

Math Wheels for Note-taking?

Problem Solving Math Wheels

Problem solving in math, or tackling word problems in math can be challenging for students, whether they’re in early elementary, upper elementary, middle school, or even high school!

Especially if they don’t have any type of strategies to help them know where to start.

I’m not necessarily a fan of using ‘tricks’ or a specific approach every time students approach a problem.

But, there are times when students will feel very ‘stuck’ as to where to start, especially if they have trouble understanding or breaking down the actual text of the problem. They may also have difficulty in middle school if they don’t have a strong problem solving foundation.

We often see students in middle school who can understand what to do mathematically when presented with a problem situation. But some of those same students kind of freeze when that problem is presented in several sentences…. especially if there’s some extra information in there.

So, I created two different math wheels to help students with:

- Deciphering word problems

- Problem solving strategies

Problem Solving Math Wheel #1

The first problem solving math wheel includes eight ideas students can use when breaking down a word problem and then solving:

1) Carefully read the problem

2) Identify the question, to be sure about what is being asked

3) Reread. Once students know what the problem is asking, they can reread to find pertinent information.

4) Circle key numbers. By circling key numbers students are taking the time to identify numbers they’ll use in their calculations.

This is helpful:

- for identifying numbers that may be in word form

- for identifying numbers that are NOT needed for the problem. These would not be circled and could even be crossed out.

5) Locate and box important words

- These words don’t necessarily need to be ‘operation’ words, but rather any words that help students understand what is happening in the problem

6) Evaluate, or solve the problem

7) Interpret and label

- The mathematical answer may not be the answer to the question (like when interpreting the quotient results in the answer being rounded up or down)

- Adding the unit label to the answer

8) Take time to check

- Is the answer reasonable? Does it make sense as an answer to the question?

This wheel has a word problem that you can work through with students when discussing these ideas.

Problem Solving Math Wheel #2

The second problem solving math wheel includes some of the well-known problem solving strategies and can be used as a simple reference to remind students that these strategies exist.

These problem solving strategies include:

- Organized List

- Guess and Check

- Work Backwards

- Make a Table

- Draw a Diagram

- Write an Equation

- Look for a Pattern

- Use Logical Reasoning

This wheel would be great for a center or finished early activity, because it doesn’t require direct instruction.

- Students can color this problem solving math wheel and then add it to their binders/notebooks and use as a reference throughout the year.

- This wheel could also be used in conjunction with the Problem Solving Doodle Notes , which can be used to teach each individual strategy, as explained in this problem solving strategies blog post .

I know your students will love this engaging way to talk about and reinforce math problem solving strategies.

The opportunity to color and add some of their own creative touches will help make the strategies more memorable.

Keeping these finished notes in their math notebooks will give students a reference for the entire school year!

read next...

Tips for Teaching Exponent Rules

How to Teach Exponents in Middle School with Math Wheels

5 Ways to Practice Problem Solving Skills in Middle School

Behavior Management Tips for the Last Few Months of the School Year

Welcome to Cognitive Cardio Math! I’m Ellie, a wife, mom, grandma, and dog ‘mom,’ and I’ve spent just about my whole life in school! With nearly 30 years in education, I’ve taught:

- All subject areas in 4 th and 5 th grades

- Math, ELA, and science in 6th grade (middle school)

I’ve been creating resources for teachers since 2012 and have worked in the elearning industry for about five years as well!

FIND IT FAST

Let's connect.

Select the image above to learn more!

Get FIVE days of free math lessons!

Terms of Use Privacy Policy

COPYRIGHT © 2022 COGNITIVE CARDIO MATH • ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. SITE DESIGN BY LAINE SUTHERLAND DESIGNS

CREATE Week: Using the Problem-Solving Wheel to Prioritize Solutions by Abby Woods

As a school leader for more than 15 years, having the ability to quickly problem solve while including my team has been a vital craft to develop. I’m Abby Woods , a longtime leader in schools working alongside teams to improve educational experiences for students. My current role, besides being a board member for CREATE , is as the Director of Internal Consulting for Charleston County School District .

The problem-solving wheel graphic has been an essential tool for my school teams to attack educational issues related to student achievement and program evaluation. Many times teams gather to admire the problem and often get derailed with discussing the issues rather than prioritizing the solution through a process of performance measures and documentation .

Lessons Learned:

- Ensure your team can stay focused on the issues at hand and encourage them to be specific with problem. For example, the literacy program is not working is vague; whereas gathering information and creating a ‘work flow’ of the literacy process will help identify the breakdown.

- Providing stakeholders with an outline or steps helps the team feel successful in problem solving. Additionally, the cogs of the wheel can be assigned, then brought back to share for further examination. Teacher teams feel especially empowered through this level of responsibility and problem-solving for their students.

- Guiding the team through this problem-solving wheel requires a systematic approach giving each member a role. Put differently, the ‘buy-in’ of the team will grow as the leader develops responsibility within the team.

Rad Resources:

- American Evaluation Association is a great resource for leaders to evaluate how your team is growing. https://www.eval.org/page/competencies

- The Flippen Group has a myriad of resources for growing, developing and stabilizing teams. These were practices that are most helpful when creating the appropriate culture for team growth and problem solving. https://flippengroup.com/capturing-kids-hearts/

- The Racial Equity Institute provided an incredible insight and tools for evaluation as leaders work in a variety of organizations.

The American Evaluation Association is celebrating Consortium for Research on Educational Assessment and Teaching (CREATE) week. The contributions all this week to aea365 come from members of CREATE. Do you have questions, concerns, kudos, or content to extend this aea365 contribution? Please add them in the comments section for this post on the aea365 webpage so that we may enrich our community of practice. Would you like to submit an aea365 Tip? Please send a note of interest to [email protected] . aea365 is sponsored by the American Evaluation Association and provides a Tip-a-Day by and for evaluators.

1 thought on “CREATE Week: Using the Problem-Solving Wheel to Prioritize Solutions by Abby Woods”

I am a student in the PME program at Queens University, in Kingston Ontario and am currently taking a course in Program Inquiry and Evaluation. I connected to your article as soon as I saw the “problem solving” wheel. As an instructional lead at my school, I can also see how this wheel would come in very handy to evaluate programs. I have led many PLC’s and we have taken on the Collaborative Inquiry model and follow the work of Jennifer Donohoo. This wheel and this model I have mentioned, have many similarities. Every stage of this wheel and the collaborative inquiry model are similar in that the contain the stages of problem solving (reflection), inquiry (awareness, gather information), collaboration (analyze information, vision and planning) and design (implement plan). Both of these models or processes allow stakeholders the ability to collaborate and through their inquires come up with a central idea or overall problem they need to try and solve by designing and implementing plans to meet their students learning needs. I appreciate that although the collaborative model is very systematic, it is not linear, and teams may need to go back and forth on the cycle. I would imagine this problem-solving wheel would be the same and participants would have the ability to go back and forth depending on any challenges the evaluation may pose. When I have facilitated inquiry teams, we brainstorm ideas, frame our problem and decide upon a common goal but after analyzing data we realize that we may need to take a step or two back and that the problem runs a little deeper than we thought. (i.e.: set a school goal of improving students reading fluency when after analyzing reading records realized that accuracy was the overall underlying issue and thus had to change our goal and focus.) I appreciate the three points you made as I also agree that participants need a systematic approach, with every member serving a specific purpose, clearly defined goals, which everyone agrees upon and are working towards and a clearly defined process to keep everyone motivated and on track. I wonder about any challenges you may face when evaluating programs and working collaboratively with a team. I wonder how you have overcome these challenges. I also have found that if success is not found after a certain amount of time, participants may lose interest in the end goal. Do you have any advice for keeping members motivated to continue and complete the program evaluation using this problem-solving wheel? I appreciated the link provided to the “performance measures and documentation” and look forward to sharing this with my team at work as I think it will help guide our evaluation questions.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of followup comments via e-mail. You can also subscribe without commenting.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

National Center for Pyramid Model Innovations

We Can Be Problem Solvers!

Scripted story to help children understand the steps to problem solving. Includes problem scenario cards to help children practice finding a solution to common social problems.

This website was made possible by Cooperative Agreement #H326B220002 which is funded by the U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs. However, those contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. This website is maintained by the University of South Florida . Contact webmaster . © University of South Florida

Get Off the Anxiety Hamster Wheel

Four steps to leave fears, worries and worst-case scenarios behind..

Posted December 19, 2018

- What Is Anxiety?

- Find a therapist to overcome anxiety

In college, I struggled with algebra. I sweated, prayed and ugly cried through every test, quiz, and random question asked in class—until that Tuesday I got smart and showed up at Professor Johnson’s office. To paraphrase the good doctor’s wisdom : Applying mathematics is to follow a series of basic structures and patterns. You employ critical thinking to find balance and predictability. Each step builds on previous steps. Always come back to problem-solving.

Ironically, I now teach a similar set of skills applied to a different life problem: how to quiet the anxious mind.

Conquering my fear of numbers came by way of slow, deep-breathing, reminding myself I was not, in fact, math-impaired, and taking it one step at a time. You can do the same to reduce anxiety by applying the following strategies:

1. Recognize the fight-flight response. Too often we overreact to the sudden onset of physical symptoms (easy to do when your heart threatens to jump out of your chest and your breath is stuck in your throat). Instead, know when your body and mind are conspiring to keep you overly focused on fears, worries, and worst-case scenarios. Deep-breathing, meditation and grounding exercises are your go-to's.

Take control question: Is there an actual threat to my personal safety or survival, or am I unintentionally panicking myself?

2. Spot the hidden culprits. The anxious response is not random, rather, our under- attention to problem-solving is finally catching up to us. All feelings go somewhere.

Take control questions: What boundaries do I need to tighten up? Are there others that could be loosened?

3. Stop with the indecision, already! A hallmark of the anxious mindset, if ever there was one. Talk about a time suck—not to mention a sure-fire method of losing social contacts. Employ rational thoughts to make a sound decision.

Take control questions: What’s the expedient take on my situation? Who can I talk to for perspective?

4. Problem-solve, instead of engaging in habitual activities that get you moving but get you nowhere. The task here is doing differently in the face of stress, worries, and uncertainty. The challenge is to summon the energy to show up and execute, rather than sink into that passive space that anxiety prefers. Acting with intention and positivity takes more mental strength than defaulting to a negative, hopeless mind space.

Take control question: If I follow the same steps when stressed out, is this likely to get me through or keep me stuck?

The road to calm can be bumpy, but sequential steps will get you on the right side of inner peace quicker. Not as elementary as 1, 2, 3, but easier and faster than learning algebra.

Linda Esposito, LCSW, is a psychotherapist helping adults and teens overcome stress and anxiety.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Problem solving wheel, social skills, friendship

Description

Children don’t always know what to do when they are experiencing conflicts with others. When students are stressed and in the moment of a conflict they can often forget how to solve the problem A problem-solving choice wheel can help them learn different ways to solve their problems.

When you create a consistent pattern of how to solve problems students will eventually pick up on that pattern and begin to implement the pattern independently.

Problem solving wheel comes in 3 different versions:

Ready-Made: “What can I do?” choice wheel is ready to use right away. Simply print, laminate and assemble an arrow.

Ready-Made: “What can I do?” poster.

Blank: Have your students draw their own pictures and write a short description.

Good friends can be hard to find! Use Friendship social skills card set to help teach children the qualities of a good friend.

Simply download and start using in your classroom today!

Questions & Answers

Olena ozyurek.

- We're hiring

- Help & FAQ

- Privacy policy

- Student privacy

- Terms of service

- Tell us what you think

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Overview of the Problem-Solving Mental Process

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Rachel Goldman, PhD FTOS, is a licensed psychologist, clinical assistant professor, speaker, wellness expert specializing in eating behaviors, stress management, and health behavior change.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Rachel-Goldman-1000-a42451caacb6423abecbe6b74e628042.jpg)

- Identify the Problem

- Define the Problem

- Form a Strategy

- Organize Information

- Allocate Resources

- Monitor Progress

- Evaluate the Results

Frequently Asked Questions

Problem-solving is a mental process that involves discovering, analyzing, and solving problems. The ultimate goal of problem-solving is to overcome obstacles and find a solution that best resolves the issue.

The best strategy for solving a problem depends largely on the unique situation. In some cases, people are better off learning everything they can about the issue and then using factual knowledge to come up with a solution. In other instances, creativity and insight are the best options.

It is not necessary to follow problem-solving steps sequentially, It is common to skip steps or even go back through steps multiple times until the desired solution is reached.

In order to correctly solve a problem, it is often important to follow a series of steps. Researchers sometimes refer to this as the problem-solving cycle. While this cycle is portrayed sequentially, people rarely follow a rigid series of steps to find a solution.

The following steps include developing strategies and organizing knowledge.

1. Identifying the Problem

While it may seem like an obvious step, identifying the problem is not always as simple as it sounds. In some cases, people might mistakenly identify the wrong source of a problem, which will make attempts to solve it inefficient or even useless.

Some strategies that you might use to figure out the source of a problem include :

- Asking questions about the problem

- Breaking the problem down into smaller pieces

- Looking at the problem from different perspectives

- Conducting research to figure out what relationships exist between different variables

2. Defining the Problem

After the problem has been identified, it is important to fully define the problem so that it can be solved. You can define a problem by operationally defining each aspect of the problem and setting goals for what aspects of the problem you will address

At this point, you should focus on figuring out which aspects of the problems are facts and which are opinions. State the problem clearly and identify the scope of the solution.

3. Forming a Strategy

After the problem has been identified, it is time to start brainstorming potential solutions. This step usually involves generating as many ideas as possible without judging their quality. Once several possibilities have been generated, they can be evaluated and narrowed down.

The next step is to develop a strategy to solve the problem. The approach used will vary depending upon the situation and the individual's unique preferences. Common problem-solving strategies include heuristics and algorithms.

- Heuristics are mental shortcuts that are often based on solutions that have worked in the past. They can work well if the problem is similar to something you have encountered before and are often the best choice if you need a fast solution.

- Algorithms are step-by-step strategies that are guaranteed to produce a correct result. While this approach is great for accuracy, it can also consume time and resources.

Heuristics are often best used when time is of the essence, while algorithms are a better choice when a decision needs to be as accurate as possible.

4. Organizing Information

Before coming up with a solution, you need to first organize the available information. What do you know about the problem? What do you not know? The more information that is available the better prepared you will be to come up with an accurate solution.

When approaching a problem, it is important to make sure that you have all the data you need. Making a decision without adequate information can lead to biased or inaccurate results.

5. Allocating Resources

Of course, we don't always have unlimited money, time, and other resources to solve a problem. Before you begin to solve a problem, you need to determine how high priority it is.

If it is an important problem, it is probably worth allocating more resources to solving it. If, however, it is a fairly unimportant problem, then you do not want to spend too much of your available resources on coming up with a solution.

At this stage, it is important to consider all of the factors that might affect the problem at hand. This includes looking at the available resources, deadlines that need to be met, and any possible risks involved in each solution. After careful evaluation, a decision can be made about which solution to pursue.

6. Monitoring Progress

After selecting a problem-solving strategy, it is time to put the plan into action and see if it works. This step might involve trying out different solutions to see which one is the most effective.

It is also important to monitor the situation after implementing a solution to ensure that the problem has been solved and that no new problems have arisen as a result of the proposed solution.

Effective problem-solvers tend to monitor their progress as they work towards a solution. If they are not making good progress toward reaching their goal, they will reevaluate their approach or look for new strategies .

7. Evaluating the Results

After a solution has been reached, it is important to evaluate the results to determine if it is the best possible solution to the problem. This evaluation might be immediate, such as checking the results of a math problem to ensure the answer is correct, or it can be delayed, such as evaluating the success of a therapy program after several months of treatment.

Once a problem has been solved, it is important to take some time to reflect on the process that was used and evaluate the results. This will help you to improve your problem-solving skills and become more efficient at solving future problems.

A Word From Verywell

It is important to remember that there are many different problem-solving processes with different steps, and this is just one example. Problem-solving in real-world situations requires a great deal of resourcefulness, flexibility, resilience, and continuous interaction with the environment.

Get Advice From The Verywell Mind Podcast

Hosted by therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast shares how you can stop dwelling in a negative mindset.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts

You can become a better problem solving by:

- Practicing brainstorming and coming up with multiple potential solutions to problems

- Being open-minded and considering all possible options before making a decision

- Breaking down problems into smaller, more manageable pieces

- Asking for help when needed

- Researching different problem-solving techniques and trying out new ones

- Learning from mistakes and using them as opportunities to grow

It's important to communicate openly and honestly with your partner about what's going on. Try to see things from their perspective as well as your own. Work together to find a resolution that works for both of you. Be willing to compromise and accept that there may not be a perfect solution.

Take breaks if things are getting too heated, and come back to the problem when you feel calm and collected. Don't try to fix every problem on your own—consider asking a therapist or counselor for help and insight.

If you've tried everything and there doesn't seem to be a way to fix the problem, you may have to learn to accept it. This can be difficult, but try to focus on the positive aspects of your life and remember that every situation is temporary. Don't dwell on what's going wrong—instead, think about what's going right. Find support by talking to friends or family. Seek professional help if you're having trouble coping.

Davidson JE, Sternberg RJ, editors. The Psychology of Problem Solving . Cambridge University Press; 2003. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511615771

Sarathy V. Real world problem-solving . Front Hum Neurosci . 2018;12:261. Published 2018 Jun 26. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2018.00261

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

How to master the seven-step problem-solving process

In this episode of the McKinsey Podcast , Simon London speaks with Charles Conn, CEO of venture-capital firm Oxford Sciences Innovation, and McKinsey senior partner Hugo Sarrazin about the complexities of different problem-solving strategies.

Podcast transcript

Simon London: Hello, and welcome to this episode of the McKinsey Podcast , with me, Simon London. What’s the number-one skill you need to succeed professionally? Salesmanship, perhaps? Or a facility with statistics? Or maybe the ability to communicate crisply and clearly? Many would argue that at the very top of the list comes problem solving: that is, the ability to think through and come up with an optimal course of action to address any complex challenge—in business, in public policy, or indeed in life.

Looked at this way, it’s no surprise that McKinsey takes problem solving very seriously, testing for it during the recruiting process and then honing it, in McKinsey consultants, through immersion in a structured seven-step method. To discuss the art of problem solving, I sat down in California with McKinsey senior partner Hugo Sarrazin and also with Charles Conn. Charles is a former McKinsey partner, entrepreneur, executive, and coauthor of the book Bulletproof Problem Solving: The One Skill That Changes Everything [John Wiley & Sons, 2018].

Charles and Hugo, welcome to the podcast. Thank you for being here.

Hugo Sarrazin: Our pleasure.

Charles Conn: It’s terrific to be here.

Simon London: Problem solving is a really interesting piece of terminology. It could mean so many different things. I have a son who’s a teenage climber. They talk about solving problems. Climbing is problem solving. Charles, when you talk about problem solving, what are you talking about?

Charles Conn: For me, problem solving is the answer to the question “What should I do?” It’s interesting when there’s uncertainty and complexity, and when it’s meaningful because there are consequences. Your son’s climbing is a perfect example. There are consequences, and it’s complicated, and there’s uncertainty—can he make that grab? I think we can apply that same frame almost at any level. You can think about questions like “What town would I like to live in?” or “Should I put solar panels on my roof?”

You might think that’s a funny thing to apply problem solving to, but in my mind it’s not fundamentally different from business problem solving, which answers the question “What should my strategy be?” Or problem solving at the policy level: “How do we combat climate change?” “Should I support the local school bond?” I think these are all part and parcel of the same type of question, “What should I do?”

I’m a big fan of structured problem solving. By following steps, we can more clearly understand what problem it is we’re solving, what are the components of the problem that we’re solving, which components are the most important ones for us to pay attention to, which analytic techniques we should apply to those, and how we can synthesize what we’ve learned back into a compelling story. That’s all it is, at its heart.

I think sometimes when people think about seven steps, they assume that there’s a rigidity to this. That’s not it at all. It’s actually to give you the scope for creativity, which often doesn’t exist when your problem solving is muddled.

Simon London: You were just talking about the seven-step process. That’s what’s written down in the book, but it’s a very McKinsey process as well. Without getting too deep into the weeds, let’s go through the steps, one by one. You were just talking about problem definition as being a particularly important thing to get right first. That’s the first step. Hugo, tell us about that.

Hugo Sarrazin: It is surprising how often people jump past this step and make a bunch of assumptions. The most powerful thing is to step back and ask the basic questions—“What are we trying to solve? What are the constraints that exist? What are the dependencies?” Let’s make those explicit and really push the thinking and defining. At McKinsey, we spend an enormous amount of time in writing that little statement, and the statement, if you’re a logic purist, is great. You debate. “Is it an ‘or’? Is it an ‘and’? What’s the action verb?” Because all these specific words help you get to the heart of what matters.

Want to subscribe to The McKinsey Podcast ?

Simon London: So this is a concise problem statement.

Hugo Sarrazin: Yeah. It’s not like “Can we grow in Japan?” That’s interesting, but it is “What, specifically, are we trying to uncover in the growth of a product in Japan? Or a segment in Japan? Or a channel in Japan?” When you spend an enormous amount of time, in the first meeting of the different stakeholders, debating this and having different people put forward what they think the problem definition is, you realize that people have completely different views of why they’re here. That, to me, is the most important step.

Charles Conn: I would agree with that. For me, the problem context is critical. When we understand “What are the forces acting upon your decision maker? How quickly is the answer needed? With what precision is the answer needed? Are there areas that are off limits or areas where we would particularly like to find our solution? Is the decision maker open to exploring other areas?” then you not only become more efficient, and move toward what we call the critical path in problem solving, but you also make it so much more likely that you’re not going to waste your time or your decision maker’s time.

How often do especially bright young people run off with half of the idea about what the problem is and start collecting data and start building models—only to discover that they’ve really gone off half-cocked.

Hugo Sarrazin: Yeah.

Charles Conn: And in the wrong direction.

Simon London: OK. So step one—and there is a real art and a structure to it—is define the problem. Step two, Charles?

Charles Conn: My favorite step is step two, which is to use logic trees to disaggregate the problem. Every problem we’re solving has some complexity and some uncertainty in it. The only way that we can really get our team working on the problem is to take the problem apart into logical pieces.

What we find, of course, is that the way to disaggregate the problem often gives you an insight into the answer to the problem quite quickly. I love to do two or three different cuts at it, each one giving a bit of a different insight into what might be going wrong. By doing sensible disaggregations, using logic trees, we can figure out which parts of the problem we should be looking at, and we can assign those different parts to team members.

Simon London: What’s a good example of a logic tree on a sort of ratable problem?

Charles Conn: Maybe the easiest one is the classic profit tree. Almost in every business that I would take a look at, I would start with a profit or return-on-assets tree. In its simplest form, you have the components of revenue, which are price and quantity, and the components of cost, which are cost and quantity. Each of those can be broken out. Cost can be broken into variable cost and fixed cost. The components of price can be broken into what your pricing scheme is. That simple tree often provides insight into what’s going on in a business or what the difference is between that business and the competitors.

If we add the leg, which is “What’s the asset base or investment element?”—so profit divided by assets—then we can ask the question “Is the business using its investments sensibly?” whether that’s in stores or in manufacturing or in transportation assets. I hope we can see just how simple this is, even though we’re describing it in words.

When I went to work with Gordon Moore at the Moore Foundation, the problem that he asked us to look at was “How can we save Pacific salmon?” Now, that sounds like an impossible question, but it was amenable to precisely the same type of disaggregation and allowed us to organize what became a 15-year effort to improve the likelihood of good outcomes for Pacific salmon.

Simon London: Now, is there a danger that your logic tree can be impossibly large? This, I think, brings us onto the third step in the process, which is that you have to prioritize.

Charles Conn: Absolutely. The third step, which we also emphasize, along with good problem definition, is rigorous prioritization—we ask the questions “How important is this lever or this branch of the tree in the overall outcome that we seek to achieve? How much can I move that lever?” Obviously, we try and focus our efforts on ones that have a big impact on the problem and the ones that we have the ability to change. With salmon, ocean conditions turned out to be a big lever, but not one that we could adjust. We focused our attention on fish habitats and fish-harvesting practices, which were big levers that we could affect.

People spend a lot of time arguing about branches that are either not important or that none of us can change. We see it in the public square. When we deal with questions at the policy level—“Should you support the death penalty?” “How do we affect climate change?” “How can we uncover the causes and address homelessness?”—it’s even more important that we’re focusing on levers that are big and movable.

Would you like to learn more about our Strategy & Corporate Finance Practice ?

Simon London: Let’s move swiftly on to step four. You’ve defined your problem, you disaggregate it, you prioritize where you want to analyze—what you want to really look at hard. Then you got to the work plan. Now, what does that mean in practice?

Hugo Sarrazin: Depending on what you’ve prioritized, there are many things you could do. It could be breaking the work among the team members so that people have a clear piece of the work to do. It could be defining the specific analyses that need to get done and executed, and being clear on time lines. There’s always a level-one answer, there’s a level-two answer, there’s a level-three answer. Without being too flippant, I can solve any problem during a good dinner with wine. It won’t have a whole lot of backing.

Simon London: Not going to have a lot of depth to it.

Hugo Sarrazin: No, but it may be useful as a starting point. If the stakes are not that high, that could be OK. If it’s really high stakes, you may need level three and have the whole model validated in three different ways. You need to find a work plan that reflects the level of precision, the time frame you have, and the stakeholders you need to bring along in the exercise.

Charles Conn: I love the way you’ve described that, because, again, some people think of problem solving as a linear thing, but of course what’s critical is that it’s iterative. As you say, you can solve the problem in one day or even one hour.

Charles Conn: We encourage our teams everywhere to do that. We call it the one-day answer or the one-hour answer. In work planning, we’re always iterating. Every time you see a 50-page work plan that stretches out to three months, you know it’s wrong. It will be outmoded very quickly by that learning process that you described. Iterative problem solving is a critical part of this. Sometimes, people think work planning sounds dull, but it isn’t. It’s how we know what’s expected of us and when we need to deliver it and how we’re progressing toward the answer. It’s also the place where we can deal with biases. Bias is a feature of every human decision-making process. If we design our team interactions intelligently, we can avoid the worst sort of biases.

Simon London: Here we’re talking about cognitive biases primarily, right? It’s not that I’m biased against you because of your accent or something. These are the cognitive biases that behavioral sciences have shown we all carry around, things like anchoring, overoptimism—these kinds of things.

Both: Yeah.

Charles Conn: Availability bias is the one that I’m always alert to. You think you’ve seen the problem before, and therefore what’s available is your previous conception of it—and we have to be most careful about that. In any human setting, we also have to be careful about biases that are based on hierarchies, sometimes called sunflower bias. I’m sure, Hugo, with your teams, you make sure that the youngest team members speak first. Not the oldest team members, because it’s easy for people to look at who’s senior and alter their own creative approaches.

Hugo Sarrazin: It’s helpful, at that moment—if someone is asserting a point of view—to ask the question “This was true in what context?” You’re trying to apply something that worked in one context to a different one. That can be deadly if the context has changed, and that’s why organizations struggle to change. You promote all these people because they did something that worked well in the past, and then there’s a disruption in the industry, and they keep doing what got them promoted even though the context has changed.

Simon London: Right. Right.

Hugo Sarrazin: So it’s the same thing in problem solving.

Charles Conn: And it’s why diversity in our teams is so important. It’s one of the best things about the world that we’re in now. We’re likely to have people from different socioeconomic, ethnic, and national backgrounds, each of whom sees problems from a slightly different perspective. It is therefore much more likely that the team will uncover a truly creative and clever approach to problem solving.

Simon London: Let’s move on to step five. You’ve done your work plan. Now you’ve actually got to do the analysis. The thing that strikes me here is that the range of tools that we have at our disposal now, of course, is just huge, particularly with advances in computation, advanced analytics. There’s so many things that you can apply here. Just talk about the analysis stage. How do you pick the right tools?

Charles Conn: For me, the most important thing is that we start with simple heuristics and explanatory statistics before we go off and use the big-gun tools. We need to understand the shape and scope of our problem before we start applying these massive and complex analytical approaches.

Simon London: Would you agree with that?

Hugo Sarrazin: I agree. I think there are so many wonderful heuristics. You need to start there before you go deep into the modeling exercise. There’s an interesting dynamic that’s happening, though. In some cases, for some types of problems, it is even better to set yourself up to maximize your learning. Your problem-solving methodology is test and learn, test and learn, test and learn, and iterate. That is a heuristic in itself, the A/B testing that is used in many parts of the world. So that’s a problem-solving methodology. It’s nothing different. It just uses technology and feedback loops in a fast way. The other one is exploratory data analysis. When you’re dealing with a large-scale problem, and there’s so much data, I can get to the heuristics that Charles was talking about through very clever visualization of data.

You test with your data. You need to set up an environment to do so, but don’t get caught up in neural-network modeling immediately. You’re testing, you’re checking—“Is the data right? Is it sound? Does it make sense?”—before you launch too far.

Simon London: You do hear these ideas—that if you have a big enough data set and enough algorithms, they’re going to find things that you just wouldn’t have spotted, find solutions that maybe you wouldn’t have thought of. Does machine learning sort of revolutionize the problem-solving process? Or are these actually just other tools in the toolbox for structured problem solving?

Charles Conn: It can be revolutionary. There are some areas in which the pattern recognition of large data sets and good algorithms can help us see things that we otherwise couldn’t see. But I do think it’s terribly important we don’t think that this particular technique is a substitute for superb problem solving, starting with good problem definition. Many people use machine learning without understanding algorithms that themselves can have biases built into them. Just as 20 years ago, when we were doing statistical analysis, we knew that we needed good model definition, we still need a good understanding of our algorithms and really good problem definition before we launch off into big data sets and unknown algorithms.

Simon London: Step six. You’ve done your analysis.

Charles Conn: I take six and seven together, and this is the place where young problem solvers often make a mistake. They’ve got their analysis, and they assume that’s the answer, and of course it isn’t the answer. The ability to synthesize the pieces that came out of the analysis and begin to weave those into a story that helps people answer the question “What should I do?” This is back to where we started. If we can’t synthesize, and we can’t tell a story, then our decision maker can’t find the answer to “What should I do?”

Simon London: But, again, these final steps are about motivating people to action, right?

Charles Conn: Yeah.

Simon London: I am slightly torn about the nomenclature of problem solving because it’s on paper, right? Until you motivate people to action, you actually haven’t solved anything.

Charles Conn: I love this question because I think decision-making theory, without a bias to action, is a waste of time. Everything in how I approach this is to help people take action that makes the world better.

Simon London: Hence, these are absolutely critical steps. If you don’t do this well, you’ve just got a bunch of analysis.

Charles Conn: We end up in exactly the same place where we started, which is people speaking across each other, past each other in the public square, rather than actually working together, shoulder to shoulder, to crack these important problems.

Simon London: In the real world, we have a lot of uncertainty—arguably, increasing uncertainty. How do good problem solvers deal with that?

Hugo Sarrazin: At every step of the process. In the problem definition, when you’re defining the context, you need to understand those sources of uncertainty and whether they’re important or not important. It becomes important in the definition of the tree.

You need to think carefully about the branches of the tree that are more certain and less certain as you define them. They don’t have equal weight just because they’ve got equal space on the page. Then, when you’re prioritizing, your prioritization approach may put more emphasis on things that have low probability but huge impact—or, vice versa, may put a lot of priority on things that are very likely and, hopefully, have a reasonable impact. You can introduce that along the way. When you come back to the synthesis, you just need to be nuanced about what you’re understanding, the likelihood.

Often, people lack humility in the way they make their recommendations: “This is the answer.” They’re very precise, and I think we would all be well-served to say, “This is a likely answer under the following sets of conditions” and then make the level of uncertainty clearer, if that is appropriate. It doesn’t mean you’re always in the gray zone; it doesn’t mean you don’t have a point of view. It just means that you can be explicit about the certainty of your answer when you make that recommendation.

Simon London: So it sounds like there is an underlying principle: “Acknowledge and embrace the uncertainty. Don’t pretend that it isn’t there. Be very clear about what the uncertainties are up front, and then build that into every step of the process.”

Hugo Sarrazin: Every step of the process.

Simon London: Yeah. We have just walked through a particular structured methodology for problem solving. But, of course, this is not the only structured methodology for problem solving. One that is also very well-known is design thinking, which comes at things very differently. So, Hugo, I know you have worked with a lot of designers. Just give us a very quick summary. Design thinking—what is it, and how does it relate?

Hugo Sarrazin: It starts with an incredible amount of empathy for the user and uses that to define the problem. It does pause and go out in the wild and spend an enormous amount of time seeing how people interact with objects, seeing the experience they’re getting, seeing the pain points or joy—and uses that to infer and define the problem.

Simon London: Problem definition, but out in the world.

Hugo Sarrazin: With an enormous amount of empathy. There’s a huge emphasis on empathy. Traditional, more classic problem solving is you define the problem based on an understanding of the situation. This one almost presupposes that we don’t know the problem until we go see it. The second thing is you need to come up with multiple scenarios or answers or ideas or concepts, and there’s a lot of divergent thinking initially. That’s slightly different, versus the prioritization, but not for long. Eventually, you need to kind of say, “OK, I’m going to converge again.” Then you go and you bring things back to the customer and get feedback and iterate. Then you rinse and repeat, rinse and repeat. There’s a lot of tactile building, along the way, of prototypes and things like that. It’s very iterative.

Simon London: So, Charles, are these complements or are these alternatives?

Charles Conn: I think they’re entirely complementary, and I think Hugo’s description is perfect. When we do problem definition well in classic problem solving, we are demonstrating the kind of empathy, at the very beginning of our problem, that design thinking asks us to approach. When we ideate—and that’s very similar to the disaggregation, prioritization, and work-planning steps—we do precisely the same thing, and often we use contrasting teams, so that we do have divergent thinking. The best teams allow divergent thinking to bump them off whatever their initial biases in problem solving are. For me, design thinking gives us a constant reminder of creativity, empathy, and the tactile nature of problem solving, but it’s absolutely complementary, not alternative.

Simon London: I think, in a world of cross-functional teams, an interesting question is do people with design-thinking backgrounds really work well together with classical problem solvers? How do you make that chemistry happen?

Hugo Sarrazin: Yeah, it is not easy when people have spent an enormous amount of time seeped in design thinking or user-centric design, whichever word you want to use. If the person who’s applying classic problem-solving methodology is very rigid and mechanical in the way they’re doing it, there could be an enormous amount of tension. If there’s not clarity in the role and not clarity in the process, I think having the two together can be, sometimes, problematic.

The second thing that happens often is that the artifacts the two methodologies try to gravitate toward can be different. Classic problem solving often gravitates toward a model; design thinking migrates toward a prototype. Rather than writing a big deck with all my supporting evidence, they’ll bring an example, a thing, and that feels different. Then you spend your time differently to achieve those two end products, so that’s another source of friction.

Now, I still think it can be an incredibly powerful thing to have the two—if there are the right people with the right mind-set, if there is a team that is explicit about the roles, if we’re clear about the kind of outcomes we are attempting to bring forward. There’s an enormous amount of collaborativeness and respect.

Simon London: But they have to respect each other’s methodology and be prepared to flex, maybe, a little bit, in how this process is going to work.

Hugo Sarrazin: Absolutely.

Simon London: The other area where, it strikes me, there could be a little bit of a different sort of friction is this whole concept of the day-one answer, which is what we were just talking about in classical problem solving. Now, you know that this is probably not going to be your final answer, but that’s how you begin to structure the problem. Whereas I would imagine your design thinkers—no, they’re going off to do their ethnographic research and get out into the field, potentially for a long time, before they come back with at least an initial hypothesis.

Want better strategies? Become a bulletproof problem solver

Hugo Sarrazin: That is a great callout, and that’s another difference. Designers typically will like to soak into the situation and avoid converging too quickly. There’s optionality and exploring different options. There’s a strong belief that keeps the solution space wide enough that you can come up with more radical ideas. If there’s a large design team or many designers on the team, and you come on Friday and say, “What’s our week-one answer?” they’re going to struggle. They’re not going to be comfortable, naturally, to give that answer. It doesn’t mean they don’t have an answer; it’s just not where they are in their thinking process.

Simon London: I think we are, sadly, out of time for today. But Charles and Hugo, thank you so much.

Charles Conn: It was a pleasure to be here, Simon.

Hugo Sarrazin: It was a pleasure. Thank you.

Simon London: And thanks, as always, to you, our listeners, for tuning into this episode of the McKinsey Podcast . If you want to learn more about problem solving, you can find the book, Bulletproof Problem Solving: The One Skill That Changes Everything , online or order it through your local bookstore. To learn more about McKinsey, you can of course find us at McKinsey.com.

Charles Conn is CEO of Oxford Sciences Innovation and an alumnus of McKinsey’s Sydney office. Hugo Sarrazin is a senior partner in the Silicon Valley office, where Simon London, a member of McKinsey Publishing, is also based.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Strategy to beat the odds

Five routes to more innovative problem solving

Problem wheel

Examples from our community, 10,000+ results for 'problem wheel'.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

A problem-solving wheel also known as the wheel of choice or solution wheel is a great way to give students a visual of choices to help them either calm down when they are upset or to help them solve a problem with a classmate. It is best to use the problem-solving wheel when students are dealing with a "small" problem.

Problem solving wheel. Walk away and let it go. Tell them to stop. Go to another activity. Rock, paper, scissors, go. Use and I statement - I feel…. Apologise. Talk it out. Ignore it.

What can I do? Walk away and Wait and cool off. Ignore it. Talk it out. let it go. Problem solving wheel Tell them to stop! STOP 60 to another activity. Rock, paper, scissors, go Use an I message Apologize.

In the moment, they can't remember things that they can do to help work through a problem. Using a solution wheel is a great resource to help them figure out different ways to solve a problem. One of the reasons I do like this lesson is because it's working on solving problems AND you can also make it a crafts project. Yay!! What you'll need:

Problem Solving Wheel Art Actvity: Attached is an good example of an effective Boardmaker problem-solving skills template What can I do?: Boardmaker Problem-Solving Wheel that you and your teen may enjoy reviewing together. As an option, you can also help your teen identify exactly what kind (s) of problem solving strategies

The wheel of choice provides a fun and exciting way to involve kids in learning and practicing problem-solving skills, especially when they are involved in creating it. Make sure your child takes the primary lead in creating his or her wheel of choice. The less you do, the better. Your child can be creative and decide if he or she would like to ...

The "Problem Solving Wheel" has many options the student can choose from such as, walk away and let it go, apologize, tell them to stop, ignore it, talk it out, and wait and cool off. Having this tool in the classroom helps minimize the fighting and arguing in the younger grade classes. It helps with giving different options that the ...

To reinforce Kelso's Choices, students can learn all about the 9 different Kelso's Choices (problem-solving strategies) with these posters. Students will learn about big versus small problems and learn all about the 9 different choices. This file can be used as posters to put up in the classroom, print individual wheels to give out to each ...

GENERAL ITEM DESCRIPTION:Empower your students with effective problem-solving skills using this printable solutions wheel. Hang it up in your classroom and help kids learn valuable techniques to tackle common problems and de-escalate challenging situations. With options like "Walk away", "Tell them ...

Problem activity. solving wheel Rock, paper, scissors, go Use an Apologize I message . WHAT CAN I DO? Do you have a srnall or medium problem? Try 2-3 of the following solutions. PROBLEM SOLVING CHOICE WHEEL Do you have a BIG problem? Go tell an adult . Author: Green, Temeca L

Problem Solving wheel. What can I do? Wait and cool off. Ignore it. Talk it out. Walk away and let it go. Tell them to stop! STOP Go to another Problem activity. solving wheel Rock, paper, scissors, go. Use an Apologize I message.

The Flexible Thinking Wonder Wheel enables you, as the parent, to guide your child towards active problem-solving. Like a wheel that goes around many times to reach a destination, you will use this wheel many times to get to your destination: flexible thinking. Mastering this process requires practice and repetition.

The first problem solving math wheel includes eight ideas students can use when breaking down a word problem and then solving: 1) Carefully read the problem. 2) Identify the question, to be sure about what is being asked. 3) Reread. Once students know what the problem is asking, they can reread to find pertinent information. 4) Circle key numbers.