Related Words and Phrases

Bottom_desktop desktop:[300x250].

Synonyms of research

- as in investigation

- as in to explore

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Thesaurus Definition of research

(Entry 1 of 2)

Synonyms & Similar Words

- investigation

- exploration

- examination

- inquisition

- disquisition

- questionnaire

- interrogation

- reinvestigation

- soul - searching

- cross - examination

- questionary

- self - examination

- self - reflection

- self - exploration

- going - over

- self - scrutiny

- self - questioning

Thesaurus Definition of research (Entry 2 of 2)

- investigate

- look (into)

- inquire (into)

- delve (into)

- check up on

- skim (through)

- thumb (through)

- reinvestigate

Thesaurus Entries Near research

Cite this entry.

“Research.” Merriam-Webster.com Thesaurus , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/thesaurus/research. Accessed 1 Apr. 2024.

More from Merriam-Webster on research

Nglish: Translation of research for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of research for Arabic Speakers

Britannica.com: Encyclopedia article about research

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

The tangled history of 'it's' and 'its', more commonly misspelled words, why does english have so many silent letters, your vs. you're: how to use them correctly, every letter is silent, sometimes: a-z list of examples, popular in wordplay, the words of the week - mar. 29, 10 scrabble words without any vowels, 12 more bird names that sound like insults (and sometimes are), 8 uncommon words related to love, 9 superb owl words, games & quizzes.

- Daily Crossword

- Word Puzzle

- Word Finder

- Word of the Day

- Synonym of the Day

- Word of the Year

- Language stories

- All featured

- Gender and sexuality

- All pop culture

- Grammar Coach ™

- Writing hub

- Grammar essentials

- Commonly confused

- All writing tips

- Pop culture

- Writing tips

Advertisement

noun as in examination, study

Strongest matches

- exploration

- investigation

Strong matches

- experimentation

- inquisition

Weak matches

- fact-finding

- fishing expedition

verb as in examine, study

- investigate

- play around with

Discover More

Related words.

Words related to research are not direct synonyms, but are associated with the word research . Browse related words to learn more about word associations.

noun as in inspection, examination

verb as in put in a specific context

verb as in dig into task, action

- leave no stone unturned

- really get into

- turn inside out

verb as in investigate; discover

- bring to light

- come across

- come up with

- search high and low

- turn upside down

Viewing 5 / 43 related words

Example Sentences

The duo spent the first year in research and engaging with farmers.

Dan Finn-Foley, head of energy storage at energy research firm Wood Mackenzie Power & Renewables, compared Google’s plan to ordering eggs for breakfast.

Users will give Deep Longevity the right to conduct anonymized research using their data as part of the app’s terms and conditions, Zhavoronkov said.

There’s also the Wilhelm Reich Museum, located at “Orgonon” in Rangeley, Maine, which was previously Reich’s estate—where he conducted questionable orgone research in the later years of his career.

When we started doing research on these topics, we were too focused on political institutions.

Have you tried to access the research that your tax dollars finance, almost all of which is kept behind a paywall?

Have a look at this telling research from Pew on blasphemy and apostasy laws around the world.

And Epstein continues to steer money toward universities to advance scientific research.

The research literature, too, asks these questions, and not without reason.

We also have a growing body of biological research showing that fathers, like mothers, are hard-wired to care for children.

We find by research that smoking was the most general mode of using tobacco in England when first introduced.

This class is composed frequently of persons of considerable learning, research and intelligence.

Speaking from recollection, it appears to be a work of some research; but I cannot say how far it is to be relied on.

Thomas Pope Blount died; an eminent English writer and a man of great learning and research.

That was long before invention became a research department full of engineers.

Synonym of the day

Start each day with the Synonym of the Day in your inbox!

By clicking "Sign Up", you are accepting Dictionary.com Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policies.

On this page you'll find 76 synonyms, antonyms, and words related to research, such as: analysis, exploration, inquiry, investigation, probe, and delving.

From Roget's 21st Century Thesaurus, Third Edition Copyright © 2013 by the Philip Lief Group.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

3.2: Overview of the Research Process

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 26219

- Anol Bhattacherjee

- University of South Florida via Global Text Project

So how do our mental paradigms shape social science research? At its core, all scientific research is an iterative process of observation, rationalization, and validation. In the observation phase, we observe a natural or social phenomenon, event, or behavior that interests us. In the rationalization phase, we try to make sense of or the observed phenomenon, event, or behavior by logically connecting the different pieces of the puzzle that we observe, which in some cases, may lead to the construction of a theory. Finally, in the validation phase, we test our theories using a scientific method through a process of data collection and analysis, and in doing so, possibly modify or extend our initial theory. However, research designs vary based on whether the researcher starts at observation and attempts to rationalize the observations (inductive research), or whether the researcher starts at an ex ante rationalization or a theory and attempts to validate the theory (deductive research). Hence, the observation-rationalization-validation cycle is very similar to the induction-deduction cycle of research discussed in Chapter 1.

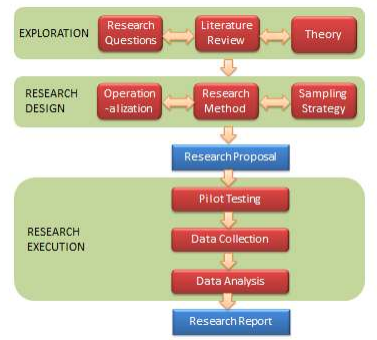

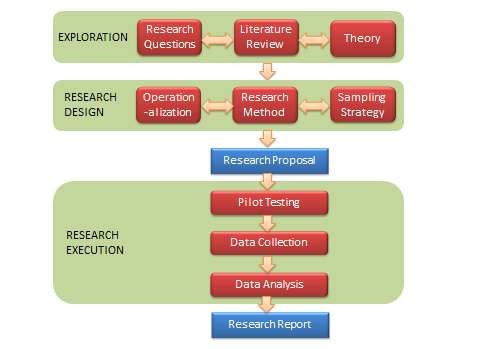

Most traditional research tends to be deductive and functionalistic in nature. Figure 3.2 provides a schematic view of such a research project. This figure depicts a series of activities to be performed in functionalist research, categorized into three phases: exploration, research design, and research execution. Note that this generalized design is not a roadmap or flowchart for all research. It applies only to functionalistic research, and it can and should be modified to fit the needs of a specific project.

The first phase of research is exploration . This phase includes exploring and selecting research questions for further investigation, examining the published literature in the area of inquiry to understand the current state of knowledge in that area, and identifying theories that may help answer the research questions of interest.

The first step in the exploration phase is identifying one or more research questions dealing with a specific behavior, event, or phenomena of interest. Research questions are specific questions about a behavior, event, or phenomena of interest that you wish to seek answers for in your research. Examples include what factors motivate consumers to purchase goods and services online without knowing the vendors of these goods or services, how can we make high school students more creative, and why do some people commit terrorist acts. Research questions can delve into issues of what, why, how, when, and so forth. More interesting research questions are those that appeal to a broader population (e.g., “how can firms innovate” is a more interesting research question than “how can Chinese firms innovate in the service-sector”), address real and complex problems (in contrast to hypothetical or “toy” problems), and where the answers are not obvious. Narrowly focused research questions (often with a binary yes/no answer) tend to be less useful and less interesting and less suited to capturing the subtle nuances of social phenomena. Uninteresting research questions generally lead to uninteresting and unpublishable research findings.

The next step is to conduct a literature review of the domain of interest. The purpose of a literature review is three-fold: (1) to survey the current state of knowledge in the area of inquiry, (2) to identify key authors, articles, theories, and findings in that area, and (3) to identify gaps in knowledge in that research area. Literature review is commonly done today using computerized keyword searches in online databases. Keywords can be combined using “and” and “or” operations to narrow down or expand the search results. Once a shortlist of relevant articles is generated from the keyword search, the researcher must then manually browse through each article, or at least its abstract section, to determine the suitability of that article for a detailed review. Literature reviews should be reasonably complete, and not restricted to a few journals, a few years, or a specific methodology. Reviewed articles may be summarized in the form of tables, and can be further structured using organizing frameworks such as a concept matrix. A well-conducted literature review should indicate whether the initial research questions have already been addressed in the literature (which would obviate the need to study them again), whether there are newer or more interesting research questions available, and whether the original research questions should be modified or changed in light of findings of the literature review. The review can also provide some intuitions or potential answers to the questions of interest and/or help identify theories that have previously been used to address similar questions.

Since functionalist (deductive) research involves theory-testing, the third step is to identify one or more theories can help address the desired research questions. While the literature review may uncover a wide range of concepts or constructs potentially related to the phenomenon of interest, a theory will help identify which of these constructs is logically relevant to the target phenomenon and how. Forgoing theories may result in measuring a wide range of less relevant, marginally relevant, or irrelevant constructs, while also minimizing the chances of obtaining results that are meaningful and not by pure chance. In functionalist research, theories can be used as the logical basis for postulating hypotheses for empirical testing. Obviously, not all theories are well-suited for studying all social phenomena. Theories must be carefully selected based on their fit with the target problem and the extent to which their assumptions are consistent with that of the target problem. We will examine theories and the process of theorizing in detail in the next chapter.

The next phase in the research process is research design . This process is concerned with creating a blueprint of the activities to take in order to satisfactorily answer the research questions identified in the exploration phase. This includes selecting a research method, operationalizing constructs of interest, and devising an appropriate sampling strategy.

Operationalization is the process of designing precise measures for abstract theoretical constructs. This is a major problem in social science research, given that many of the constructs, such as prejudice, alienation, and liberalism are hard to define, let alone measure accurately. Operationalization starts with specifying an “operational definition” (or “conceptualization”) of the constructs of interest. Next, the researcher can search the literature to see if there are existing prevalidated measures matching their operational definition that can be used directly or modified to measure their constructs of interest. If such measures are not available or if existing measures are poor or reflect a different conceptualization than that intended by the researcher, new instruments may have to be designed for measuring those constructs. This means specifying exactly how exactly the desired construct will be measured (e.g., how many items, what items, and so forth). This can easily be a long and laborious process, with multiple rounds of pretests and modifications before the newly designed instrument can be accepted as “scientifically valid.” We will discuss operationalization of constructs in a future chapter on measurement.

Simultaneously with operationalization, the researcher must also decide what research method they wish to employ for collecting data to address their research questions of interest. Such methods may include quantitative methods such as experiments or survey research or qualitative methods such as case research or action research, or possibly a combination of both. If an experiment is desired, then what is the experimental design? If survey, do you plan a mail survey, telephone survey, web survey, or a combination? For complex, uncertain, and multifaceted social phenomena, multi-method approaches may be more suitable, which may help leverage the unique strengths of each research method and generate insights that may not be obtained using a single method.

Researchers must also carefully choose the target population from which they wish to collect data, and a sampling strategy to select a sample from that population. For instance, should they survey individuals or firms or workgroups within firms? What types of individuals or firms they wish to target? Sampling strategy is closely related to the unit of analysis in a research problem. While selecting a sample, reasonable care should be taken to avoid a biased sample (e.g., sample based on convenience) that may generate biased observations. Sampling is covered in depth in a later chapter.

At this stage, it is often a good idea to write a research proposal detailing all of the decisions made in the preceding stages of the research process and the rationale behind each decision. This multi-part proposal should address what research questions you wish to study and why, the prior state of knowledge in this area, theories you wish to employ along with hypotheses to be tested, how to measure constructs, what research method to be employed and why, and desired sampling strategy. Funding agencies typically require such a proposal in order to select the best proposals for funding. Even if funding is not sought for a research project, a proposal may serve as a useful vehicle for seeking feedback from other researchers and identifying potential problems with the research project (e.g., whether some important constructs were missing from the study) before starting data collection. This initial feedback is invaluable because it is often too late to correct critical problems after data is collected in a research study.

Having decided who to study (subjects), what to measure (concepts), and how to collect data (research method), the researcher is now ready to proceed to the research execution phase. This includes pilot testing the measurement instruments, data collection, and data analysis.

Pilot testing is an often overlooked but extremely important part of the research process. It helps detect potential problems in your research design and/or instrumentation (e.g., whether the questions asked is intelligible to the targeted sample), and to ensure that the measurement instruments used in the study are reliable and valid measures of the constructs of interest. The pilot sample is usually a small subset of the target population. After a successful pilot testing, the researcher may then proceed with data collection using the sampled population. The data collected may be quantitative or qualitative, depending on the research method employed.

Following data collection, the data is analyzed and interpreted for the purpose of drawing conclusions regarding the research questions of interest. Depending on the type of data collected (quantitative or qualitative), data analysis may be quantitative (e.g., employ statistical techniques such as regression or structural equation modeling) or qualitative (e.g., coding or content analysis).

The final phase of research involves preparing the final research report documenting the entire research process and its findings in the form of a research paper, dissertation, or monograph. This report should outline in detail all the choices made during the research process (e.g., theory used, constructs selected, measures used, research methods, sampling, etc.) and why, as well as the outcomes of each phase of the research process. The research process must be described in sufficient detail so as to allow other researchers to replicate your study, test the findings, or assess whether the inferences derived are scientifically acceptable. Of course, having a ready research proposal will greatly simplify and quicken the process of writing the finished report. Note that research is of no value unless the research process and outcomes are documented for future generations; such documentation is essential for the incremental progress of science.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

A Beginner's Guide to Starting the Research Process

When you have to write a thesis or dissertation , it can be hard to know where to begin, but there are some clear steps you can follow.

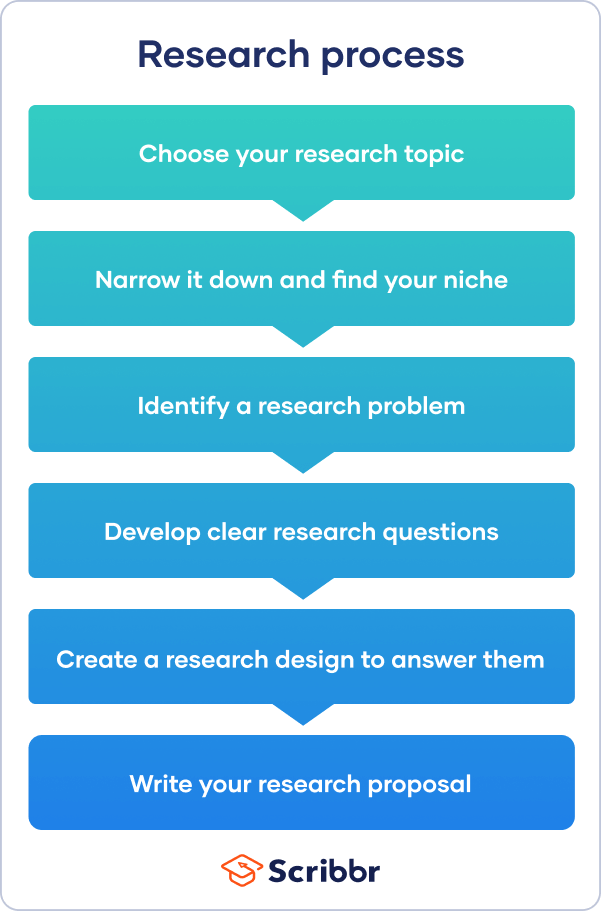

The research process often begins with a very broad idea for a topic you’d like to know more about. You do some preliminary research to identify a problem . After refining your research questions , you can lay out the foundations of your research design , leading to a proposal that outlines your ideas and plans.

This article takes you through the first steps of the research process, helping you narrow down your ideas and build up a strong foundation for your research project.

Table of contents

Step 1: choose your topic, step 2: identify a problem, step 3: formulate research questions, step 4: create a research design, step 5: write a research proposal, other interesting articles.

First you have to come up with some ideas. Your thesis or dissertation topic can start out very broad. Think about the general area or field you’re interested in—maybe you already have specific research interests based on classes you’ve taken, or maybe you had to consider your topic when applying to graduate school and writing a statement of purpose .

Even if you already have a good sense of your topic, you’ll need to read widely to build background knowledge and begin narrowing down your ideas. Conduct an initial literature review to begin gathering relevant sources. As you read, take notes and try to identify problems, questions, debates, contradictions and gaps. Your aim is to narrow down from a broad area of interest to a specific niche.

Make sure to consider the practicalities: the requirements of your programme, the amount of time you have to complete the research, and how difficult it will be to access sources and data on the topic. Before moving onto the next stage, it’s a good idea to discuss the topic with your thesis supervisor.

>>Read more about narrowing down a research topic

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

So you’ve settled on a topic and found a niche—but what exactly will your research investigate, and why does it matter? To give your project focus and purpose, you have to define a research problem .

The problem might be a practical issue—for example, a process or practice that isn’t working well, an area of concern in an organization’s performance, or a difficulty faced by a specific group of people in society.

Alternatively, you might choose to investigate a theoretical problem—for example, an underexplored phenomenon or relationship, a contradiction between different models or theories, or an unresolved debate among scholars.

To put the problem in context and set your objectives, you can write a problem statement . This describes who the problem affects, why research is needed, and how your research project will contribute to solving it.

>>Read more about defining a research problem

Next, based on the problem statement, you need to write one or more research questions . These target exactly what you want to find out. They might focus on describing, comparing, evaluating, or explaining the research problem.

A strong research question should be specific enough that you can answer it thoroughly using appropriate qualitative or quantitative research methods. It should also be complex enough to require in-depth investigation, analysis, and argument. Questions that can be answered with “yes/no” or with easily available facts are not complex enough for a thesis or dissertation.

In some types of research, at this stage you might also have to develop a conceptual framework and testable hypotheses .

>>See research question examples

The research design is a practical framework for answering your research questions. It involves making decisions about the type of data you need, the methods you’ll use to collect and analyze it, and the location and timescale of your research.

There are often many possible paths you can take to answering your questions. The decisions you make will partly be based on your priorities. For example, do you want to determine causes and effects, draw generalizable conclusions, or understand the details of a specific context?

You need to decide whether you will use primary or secondary data and qualitative or quantitative methods . You also need to determine the specific tools, procedures, and materials you’ll use to collect and analyze your data, as well as your criteria for selecting participants or sources.

>>Read more about creating a research design

Finally, after completing these steps, you are ready to complete a research proposal . The proposal outlines the context, relevance, purpose, and plan of your research.

As well as outlining the background, problem statement, and research questions, the proposal should also include a literature review that shows how your project will fit into existing work on the topic. The research design section describes your approach and explains exactly what you will do.

You might have to get the proposal approved by your supervisor before you get started, and it will guide the process of writing your thesis or dissertation.

>>Read more about writing a research proposal

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked.

- Writing Strong Research Questions | Criteria & Examples

What Is a Research Design | Types, Guide & Examples

- How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

More interesting articles

- 10 Research Question Examples to Guide Your Research Project

- How to Choose a Dissertation Topic | 8 Steps to Follow

- How to Define a Research Problem | Ideas & Examples

- How to Write a Problem Statement | Guide & Examples

- Relevance of Your Dissertation Topic | Criteria & Tips

- Research Objectives | Definition & Examples

- What Is a Fishbone Diagram? | Templates & Examples

- What Is Root Cause Analysis? | Definition & Examples

Unlimited Academic AI-Proofreading

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Table of Contents

Research Process

Definition:

Research Process is a systematic and structured approach that involves the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data or information to answer a specific research question or solve a particular problem.

Research Process Steps

Research Process Steps are as follows:

Identify the Research Question or Problem

This is the first step in the research process. It involves identifying a problem or question that needs to be addressed. The research question should be specific, relevant, and focused on a particular area of interest.

Conduct a Literature Review

Once the research question has been identified, the next step is to conduct a literature review. This involves reviewing existing research and literature on the topic to identify any gaps in knowledge or areas where further research is needed. A literature review helps to provide a theoretical framework for the research and also ensures that the research is not duplicating previous work.

Formulate a Hypothesis or Research Objectives

Based on the research question and literature review, the researcher can formulate a hypothesis or research objectives. A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested to determine its validity, while research objectives are specific goals that the researcher aims to achieve through the research.

Design a Research Plan and Methodology

This step involves designing a research plan and methodology that will enable the researcher to collect and analyze data to test the hypothesis or achieve the research objectives. The research plan should include details on the sample size, data collection methods, and data analysis techniques that will be used.

Collect and Analyze Data

This step involves collecting and analyzing data according to the research plan and methodology. Data can be collected through various methods, including surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments. The data analysis process involves cleaning and organizing the data, applying statistical and analytical techniques to the data, and interpreting the results.

Interpret the Findings and Draw Conclusions

After analyzing the data, the researcher must interpret the findings and draw conclusions. This involves assessing the validity and reliability of the results and determining whether the hypothesis was supported or not. The researcher must also consider any limitations of the research and discuss the implications of the findings.

Communicate the Results

Finally, the researcher must communicate the results of the research through a research report, presentation, or publication. The research report should provide a detailed account of the research process, including the research question, literature review, research methodology, data analysis, findings, and conclusions. The report should also include recommendations for further research in the area.

Review and Revise

The research process is an iterative one, and it is important to review and revise the research plan and methodology as necessary. Researchers should assess the quality of their data and methods, reflect on their findings, and consider areas for improvement.

Ethical Considerations

Throughout the research process, ethical considerations must be taken into account. This includes ensuring that the research design protects the welfare of research participants, obtaining informed consent, maintaining confidentiality and privacy, and avoiding any potential harm to participants or their communities.

Dissemination and Application

The final step in the research process is to disseminate the findings and apply the research to real-world settings. Researchers can share their findings through academic publications, presentations at conferences, or media coverage. The research can be used to inform policy decisions, develop interventions, or improve practice in the relevant field.

Research Process Example

Following is a Research Process Example:

Research Question : What are the effects of a plant-based diet on athletic performance in high school athletes?

Step 1: Background Research Conduct a literature review to gain a better understanding of the existing research on the topic. Read academic articles and research studies related to plant-based diets, athletic performance, and high school athletes.

Step 2: Develop a Hypothesis Based on the literature review, develop a hypothesis that a plant-based diet positively affects athletic performance in high school athletes.

Step 3: Design the Study Design a study to test the hypothesis. Decide on the study population, sample size, and research methods. For this study, you could use a survey to collect data on dietary habits and athletic performance from a sample of high school athletes who follow a plant-based diet and a sample of high school athletes who do not follow a plant-based diet.

Step 4: Collect Data Distribute the survey to the selected sample and collect data on dietary habits and athletic performance.

Step 5: Analyze Data Use statistical analysis to compare the data from the two samples and determine if there is a significant difference in athletic performance between those who follow a plant-based diet and those who do not.

Step 6 : Interpret Results Interpret the results of the analysis in the context of the research question and hypothesis. Discuss any limitations or potential biases in the study design.

Step 7: Draw Conclusions Based on the results, draw conclusions about whether a plant-based diet has a significant effect on athletic performance in high school athletes. If the hypothesis is supported by the data, discuss potential implications and future research directions.

Step 8: Communicate Findings Communicate the findings of the study in a clear and concise manner. Use appropriate language, visuals, and formats to ensure that the findings are understood and valued.

Applications of Research Process

The research process has numerous applications across a wide range of fields and industries. Some examples of applications of the research process include:

- Scientific research: The research process is widely used in scientific research to investigate phenomena in the natural world and develop new theories or technologies. This includes fields such as biology, chemistry, physics, and environmental science.

- Social sciences : The research process is commonly used in social sciences to study human behavior, social structures, and institutions. This includes fields such as sociology, psychology, anthropology, and economics.

- Education: The research process is used in education to study learning processes, curriculum design, and teaching methodologies. This includes research on student achievement, teacher effectiveness, and educational policy.

- Healthcare: The research process is used in healthcare to investigate medical conditions, develop new treatments, and evaluate healthcare interventions. This includes fields such as medicine, nursing, and public health.

- Business and industry : The research process is used in business and industry to study consumer behavior, market trends, and develop new products or services. This includes market research, product development, and customer satisfaction research.

- Government and policy : The research process is used in government and policy to evaluate the effectiveness of policies and programs, and to inform policy decisions. This includes research on social welfare, crime prevention, and environmental policy.

Purpose of Research Process

The purpose of the research process is to systematically and scientifically investigate a problem or question in order to generate new knowledge or solve a problem. The research process enables researchers to:

- Identify gaps in existing knowledge: By conducting a thorough literature review, researchers can identify gaps in existing knowledge and develop research questions that address these gaps.

- Collect and analyze data : The research process provides a structured approach to collecting and analyzing data. Researchers can use a variety of research methods, including surveys, experiments, and interviews, to collect data that is valid and reliable.

- Test hypotheses : The research process allows researchers to test hypotheses and make evidence-based conclusions. Through the systematic analysis of data, researchers can draw conclusions about the relationships between variables and develop new theories or models.

- Solve problems: The research process can be used to solve practical problems and improve real-world outcomes. For example, researchers can develop interventions to address health or social problems, evaluate the effectiveness of policies or programs, and improve organizational processes.

- Generate new knowledge : The research process is a key way to generate new knowledge and advance understanding in a given field. By conducting rigorous and well-designed research, researchers can make significant contributions to their field and help to shape future research.

Tips for Research Process

Here are some tips for the research process:

- Start with a clear research question : A well-defined research question is the foundation of a successful research project. It should be specific, relevant, and achievable within the given time frame and resources.

- Conduct a thorough literature review: A comprehensive literature review will help you to identify gaps in existing knowledge, build on previous research, and avoid duplication. It will also provide a theoretical framework for your research.

- Choose appropriate research methods: Select research methods that are appropriate for your research question, objectives, and sample size. Ensure that your methods are valid, reliable, and ethical.

- Be organized and systematic: Keep detailed notes throughout the research process, including your research plan, methodology, data collection, and analysis. This will help you to stay organized and ensure that you don’t miss any important details.

- Analyze data rigorously: Use appropriate statistical and analytical techniques to analyze your data. Ensure that your analysis is valid, reliable, and transparent.

- I nterpret results carefully : Interpret your results in the context of your research question and objectives. Consider any limitations or potential biases in your research design, and be cautious in drawing conclusions.

- Communicate effectively: Communicate your research findings clearly and effectively to your target audience. Use appropriate language, visuals, and formats to ensure that your findings are understood and valued.

- Collaborate and seek feedback : Collaborate with other researchers, experts, or stakeholders in your field. Seek feedback on your research design, methods, and findings to ensure that they are relevant, meaningful, and impactful.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

Research Questions – Types, Examples and Writing...

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

3 The research process

In Chapter 1, we saw that scientific research is the process of acquiring scientific knowledge using the scientific method. But how is such research conducted? This chapter delves into the process of scientific research, and the assumptions and outcomes of the research process.

Paradigms of social research

Our design and conduct of research is shaped by our mental models, or frames of reference that we use to organise our reasoning and observations. These mental models or frames (belief systems) are called paradigms . The word ‘paradigm’ was popularised by Thomas Kuhn (1962) [1] in his book The structure of scientific r evolutions , where he examined the history of the natural sciences to identify patterns of activities that shape the progress of science. Similar ideas are applicable to social sciences as well, where a social reality can be viewed by different people in different ways, which may constrain their thinking and reasoning about the observed phenomenon. For instance, conservatives and liberals tend to have very different perceptions of the role of government in people’s lives, and hence, have different opinions on how to solve social problems. Conservatives may believe that lowering taxes is the best way to stimulate a stagnant economy because it increases people’s disposable income and spending, which in turn expands business output and employment. In contrast, liberals may believe that governments should invest more directly in job creation programs such as public works and infrastructure projects, which will increase employment and people’s ability to consume and drive the economy. Likewise, Western societies place greater emphasis on individual rights, such as one’s right to privacy, right of free speech, and right to bear arms. In contrast, Asian societies tend to balance the rights of individuals against the rights of families, organisations, and the government, and therefore tend to be more communal and less individualistic in their policies. Such differences in perspective often lead Westerners to criticise Asian governments for being autocratic, while Asians criticise Western societies for being greedy, having high crime rates, and creating a ‘cult of the individual’. Our personal paradigms are like ‘coloured glasses’ that govern how we view the world and how we structure our thoughts about what we see in the world.

Paradigms are often hard to recognise, because they are implicit, assumed, and taken for granted. However, recognising these paradigms is key to making sense of and reconciling differences in people’s perceptions of the same social phenomenon. For instance, why do liberals believe that the best way to improve secondary education is to hire more teachers, while conservatives believe that privatising education (using such means as school vouchers) is more effective in achieving the same goal? Conservatives place more faith in competitive markets (i.e., in free competition between schools competing for education dollars), while liberals believe more in labour (i.e., in having more teachers and schools). Likewise, in social science research, to understand why a certain technology was successfully implemented in one organisation, but failed miserably in another, a researcher looking at the world through a ‘rational lens’ will look for rational explanations of the problem, such as inadequate technology or poor fit between technology and the task context where it is being utilised. Another researcher looking at the same problem through a ‘social lens’ may seek out social deficiencies such as inadequate user training or lack of management support. Those seeing it through a ‘political lens’ will look for instances of organisational politics that may subvert the technology implementation process. Hence, subconscious paradigms often constrain the concepts that researchers attempt to measure, their observations, and their subsequent interpretations of a phenomenon. However, given the complex nature of social phenomena, it is possible that all of the above paradigms are partially correct, and that a fuller understanding of the problem may require an understanding and application of multiple paradigms.

Two popular paradigms today among social science researchers are positivism and post-positivism. Positivism , based on the works of French philosopher Auguste Comte (1798–1857), was the dominant scientific paradigm until the mid-twentieth century. It holds that science or knowledge creation should be restricted to what can be observed and measured. Positivism tends to rely exclusively on theories that can be directly tested. Though positivism was originally an attempt to separate scientific inquiry from religion (where the precepts could not be objectively observed), positivism led to empiricism or a blind faith in observed data and a rejection of any attempt to extend or reason beyond observable facts. Since human thoughts and emotions could not be directly measured, they were not considered to be legitimate topics for scientific research. Frustrations with the strictly empirical nature of positivist philosophy led to the development of post-positivism (or postmodernism) during the mid-late twentieth century. Post-positivism argues that one can make reasonable inferences about a phenomenon by combining empirical observations with logical reasoning. Post-positivists view science as not certain but probabilistic (i.e., based on many contingencies), and often seek to explore these contingencies to understand social reality better. The post-positivist camp has further fragmented into subjectivists , who view the world as a subjective construction of our subjective minds rather than as an objective reality, and critical realists , who believe that there is an external reality that is independent of a person’s thinking but we can never know such reality with any degree of certainty.

Burrell and Morgan (1979), [2] in their seminal book Sociological p aradigms and organizational a nalysis , suggested that the way social science researchers view and study social phenomena is shaped by two fundamental sets of philosophical assumptions: ontology and epistemology. Ontology refers to our assumptions about how we see the world (e.g., does the world consist mostly of social order or constant change?). Epistemology refers to our assumptions about the best way to study the world (e.g., should we use an objective or subjective approach to study social reality?). Using these two sets of assumptions, we can categorise social science research as belonging to one of four categories (see Figure 3.1).

If researchers view the world as consisting mostly of social order (ontology) and hence seek to study patterns of ordered events or behaviours, and believe that the best way to study such a world is using an objective approach (epistemology) that is independent of the person conducting the observation or interpretation, such as by using standardised data collection tools like surveys, then they are adopting a paradigm of functionalism . However, if they believe that the best way to study social order is though the subjective interpretation of participants, such as by interviewing different participants and reconciling differences among their responses using their own subjective perspectives, then they are employing an interpretivism paradigm. If researchers believe that the world consists of radical change and seek to understand or enact change using an objectivist approach, then they are employing a radical structuralism paradigm. If they wish to understand social change using the subjective perspectives of the participants involved, then they are following a radical humanism paradigm.

To date, the majority of social science research has emulated the natural sciences, and followed the functionalist paradigm. Functionalists believe that social order or patterns can be understood in terms of their functional components, and therefore attempt to break down a problem into small components and studying one or more components in detail using objectivist techniques such as surveys and experimental research. However, with the emergence of post-positivist thinking, a small but growing number of social science researchers are attempting to understand social order using subjectivist techniques such as interviews and ethnographic studies. Radical humanism and radical structuralism continues to represent a negligible proportion of social science research, because scientists are primarily concerned with understanding generalisable patterns of behaviour, events, or phenomena, rather than idiosyncratic or changing events. Nevertheless, if you wish to study social change, such as why democratic movements are increasingly emerging in Middle Eastern countries, or why this movement was successful in Tunisia, took a longer path to success in Libya, and is still not successful in Syria, then perhaps radical humanism is the right approach for such a study. Social and organisational phenomena generally consist of elements of both order and change. For instance, organisational success depends on formalised business processes, work procedures, and job responsibilities, while being simultaneously constrained by a constantly changing mix of competitors, competing products, suppliers, and customer base in the business environment. Hence, a holistic and more complete understanding of social phenomena such as why some organisations are more successful than others, requires an appreciation and application of a multi-paradigmatic approach to research.

Overview of the research process

So how do our mental paradigms shape social science research? At its core, all scientific research is an iterative process of observation, rationalisation, and validation. In the observation phase, we observe a natural or social phenomenon, event, or behaviour that interests us. In the rationalisation phase, we try to make sense of the observed phenomenon, event, or behaviour by logically connecting the different pieces of the puzzle that we observe, which in some cases, may lead to the construction of a theory. Finally, in the validation phase, we test our theories using a scientific method through a process of data collection and analysis, and in doing so, possibly modify or extend our initial theory. However, research designs vary based on whether the researcher starts at observation and attempts to rationalise the observations (inductive research), or whether the researcher starts at an ex ante rationalisation or a theory and attempts to validate the theory (deductive research). Hence, the observation-rationalisation-validation cycle is very similar to the induction-deduction cycle of research discussed in Chapter 1.

Most traditional research tends to be deductive and functionalistic in nature. Figure 3.2 provides a schematic view of such a research project. This figure depicts a series of activities to be performed in functionalist research, categorised into three phases: exploration, research design, and research execution. Note that this generalised design is not a roadmap or flowchart for all research. It applies only to functionalistic research, and it can and should be modified to fit the needs of a specific project.

The first phase of research is exploration . This phase includes exploring and selecting research questions for further investigation, examining the published literature in the area of inquiry to understand the current state of knowledge in that area, and identifying theories that may help answer the research questions of interest.

The first step in the exploration phase is identifying one or more research questions dealing with a specific behaviour, event, or phenomena of interest. Research questions are specific questions about a behaviour, event, or phenomena of interest that you wish to seek answers for in your research. Examples include determining which factors motivate consumers to purchase goods and services online without knowing the vendors of these goods or services, how can we make high school students more creative, and why some people commit terrorist acts. Research questions can delve into issues of what, why, how, when, and so forth. More interesting research questions are those that appeal to a broader population (e.g., ‘how can firms innovate?’ is a more interesting research question than ‘how can Chinese firms innovate in the service-sector?’), address real and complex problems (in contrast to hypothetical or ‘toy’ problems), and where the answers are not obvious. Narrowly focused research questions (often with a binary yes/no answer) tend to be less useful and less interesting and less suited to capturing the subtle nuances of social phenomena. Uninteresting research questions generally lead to uninteresting and unpublishable research findings.

The next step is to conduct a literature review of the domain of interest. The purpose of a literature review is three-fold: one, to survey the current state of knowledge in the area of inquiry, two, to identify key authors, articles, theories, and findings in that area, and three, to identify gaps in knowledge in that research area. Literature review is commonly done today using computerised keyword searches in online databases. Keywords can be combined using Boolean operators such as ‘and’ and ‘or’ to narrow down or expand the search results. Once a shortlist of relevant articles is generated from the keyword search, the researcher must then manually browse through each article, or at least its abstract, to determine the suitability of that article for a detailed review. Literature reviews should be reasonably complete, and not restricted to a few journals, a few years, or a specific methodology. Reviewed articles may be summarised in the form of tables, and can be further structured using organising frameworks such as a concept matrix. A well-conducted literature review should indicate whether the initial research questions have already been addressed in the literature (which would obviate the need to study them again), whether there are newer or more interesting research questions available, and whether the original research questions should be modified or changed in light of the findings of the literature review. The review can also provide some intuitions or potential answers to the questions of interest and/or help identify theories that have previously been used to address similar questions.

Since functionalist (deductive) research involves theory-testing, the third step is to identify one or more theories can help address the desired research questions. While the literature review may uncover a wide range of concepts or constructs potentially related to the phenomenon of interest, a theory will help identify which of these constructs is logically relevant to the target phenomenon and how. Forgoing theories may result in measuring a wide range of less relevant, marginally relevant, or irrelevant constructs, while also minimising the chances of obtaining results that are meaningful and not by pure chance. In functionalist research, theories can be used as the logical basis for postulating hypotheses for empirical testing. Obviously, not all theories are well-suited for studying all social phenomena. Theories must be carefully selected based on their fit with the target problem and the extent to which their assumptions are consistent with that of the target problem. We will examine theories and the process of theorising in detail in the next chapter.

The next phase in the research process is research design . This process is concerned with creating a blueprint of the actions to take in order to satisfactorily answer the research questions identified in the exploration phase. This includes selecting a research method, operationalising constructs of interest, and devising an appropriate sampling strategy.

Operationalisation is the process of designing precise measures for abstract theoretical constructs. This is a major problem in social science research, given that many of the constructs, such as prejudice, alienation, and liberalism are hard to define, let alone measure accurately. Operationalisation starts with specifying an ‘operational definition’ (or ‘conceptualization’) of the constructs of interest. Next, the researcher can search the literature to see if there are existing pre-validated measures matching their operational definition that can be used directly or modified to measure their constructs of interest. If such measures are not available or if existing measures are poor or reflect a different conceptualisation than that intended by the researcher, new instruments may have to be designed for measuring those constructs. This means specifying exactly how exactly the desired construct will be measured (e.g., how many items, what items, and so forth). This can easily be a long and laborious process, with multiple rounds of pre-tests and modifications before the newly designed instrument can be accepted as ‘scientifically valid’. We will discuss operationalisation of constructs in a future chapter on measurement.

Simultaneously with operationalisation, the researcher must also decide what research method they wish to employ for collecting data to address their research questions of interest. Such methods may include quantitative methods such as experiments or survey research or qualitative methods such as case research or action research, or possibly a combination of both. If an experiment is desired, then what is the experimental design? If this is a survey, do you plan a mail survey, telephone survey, web survey, or a combination? For complex, uncertain, and multifaceted social phenomena, multi-method approaches may be more suitable, which may help leverage the unique strengths of each research method and generate insights that may not be obtained using a single method.

Researchers must also carefully choose the target population from which they wish to collect data, and a sampling strategy to select a sample from that population. For instance, should they survey individuals or firms or workgroups within firms? What types of individuals or firms do they wish to target? Sampling strategy is closely related to the unit of analysis in a research problem. While selecting a sample, reasonable care should be taken to avoid a biased sample (e.g., sample based on convenience) that may generate biased observations. Sampling is covered in depth in a later chapter.

At this stage, it is often a good idea to write a research proposal detailing all of the decisions made in the preceding stages of the research process and the rationale behind each decision. This multi-part proposal should address what research questions you wish to study and why, the prior state of knowledge in this area, theories you wish to employ along with hypotheses to be tested, how you intend to measure constructs, what research method is to be employed and why, and desired sampling strategy. Funding agencies typically require such a proposal in order to select the best proposals for funding. Even if funding is not sought for a research project, a proposal may serve as a useful vehicle for seeking feedback from other researchers and identifying potential problems with the research project (e.g., whether some important constructs were missing from the study) before starting data collection. This initial feedback is invaluable because it is often too late to correct critical problems after data is collected in a research study.

Having decided who to study (subjects), what to measure (concepts), and how to collect data (research method), the researcher is now ready to proceed to the research execution phase. This includes pilot testing the measurement instruments, data collection, and data analysis.

Pilot testing is an often overlooked but extremely important part of the research process. It helps detect potential problems in your research design and/or instrumentation (e.g., whether the questions asked are intelligible to the targeted sample), and to ensure that the measurement instruments used in the study are reliable and valid measures of the constructs of interest. The pilot sample is usually a small subset of the target population. After successful pilot testing, the researcher may then proceed with data collection using the sampled population. The data collected may be quantitative or qualitative, depending on the research method employed.

Following data collection, the data is analysed and interpreted for the purpose of drawing conclusions regarding the research questions of interest. Depending on the type of data collected (quantitative or qualitative), data analysis may be quantitative (e.g., employ statistical techniques such as regression or structural equation modelling) or qualitative (e.g., coding or content analysis).

The final phase of research involves preparing the final research report documenting the entire research process and its findings in the form of a research paper, dissertation, or monograph. This report should outline in detail all the choices made during the research process (e.g., theory used, constructs selected, measures used, research methods, sampling, etc.) and why, as well as the outcomes of each phase of the research process. The research process must be described in sufficient detail so as to allow other researchers to replicate your study, test the findings, or assess whether the inferences derived are scientifically acceptable. Of course, having a ready research proposal will greatly simplify and quicken the process of writing the finished report. Note that research is of no value unless the research process and outcomes are documented for future generations—such documentation is essential for the incremental progress of science.

Common mistakes in research

The research process is fraught with problems and pitfalls, and novice researchers often find, after investing substantial amounts of time and effort into a research project, that their research questions were not sufficiently answered, or that the findings were not interesting enough, or that the research was not of ‘acceptable’ scientific quality. Such problems typically result in research papers being rejected by journals. Some of the more frequent mistakes are described below.

Insufficiently motivated research questions. Often times, we choose our ‘pet’ problems that are interesting to us but not to the scientific community at large, i.e., it does not generate new knowledge or insight about the phenomenon being investigated. Because the research process involves a significant investment of time and effort on the researcher’s part, the researcher must be certain—and be able to convince others—that the research questions they seek to answer deal with real—and not hypothetical—problems that affect a substantial portion of a population and have not been adequately addressed in prior research.

Pursuing research fads. Another common mistake is pursuing ‘popular’ topics with limited shelf life. A typical example is studying technologies or practices that are popular today. Because research takes several years to complete and publish, it is possible that popular interest in these fads may die down by the time the research is completed and submitted for publication. A better strategy may be to study ‘timeless’ topics that have always persisted through the years.

Unresearchable problems. Some research problems may not be answered adequately based on observed evidence alone, or using currently accepted methods and procedures. Such problems are best avoided. However, some unresearchable, ambiguously defined problems may be modified or fine tuned into well-defined and useful researchable problems.

Favoured research methods. Many researchers have a tendency to recast a research problem so that it is amenable to their favourite research method (e.g., survey research). This is an unfortunate trend. Research methods should be chosen to best fit a research problem, and not the other way around.

Blind data mining. Some researchers have the tendency to collect data first (using instruments that are already available), and then figure out what to do with it. Note that data collection is only one step in a long and elaborate process of planning, designing, and executing research. In fact, a series of other activities are needed in a research process prior to data collection. If researchers jump into data collection without such elaborate planning, the data collected will likely be irrelevant, imperfect, or useless, and their data collection efforts may be entirely wasted. An abundance of data cannot make up for deficits in research planning and design, and particularly, for the lack of interesting research questions.

- Kuhn, T. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions . Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ↵

- Burrell, G. & Morgan, G. (1979). Sociological paradigms and organisational analysis: elements of the sociology of corporate life . London: Heinemann Educational. ↵

Social Science Research: Principles, Methods and Practices (Revised edition) Copyright © 2019 by Anol Bhattacherjee is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

University Libraries

- Ohio University Libraries

- Library Guides

- Library Research Process

- Words and Synonyms

- Research: An Overview

- Narrowing a Topic

- Doing Presearch

- Scholarly vs. Popular

- What's in a Scholarly Article?

- Finding Books

- Finding Articles

- Film & Video

- Subject Databases and Guides

- Spotting Fake News

- The Four Moves

- Quick Journal Article Evaluation

- Zotero: Tracking Sources

- Information In Real Life Tutorial

- Scholarship as a Conversation and Article Deep Dive

Handouts for the 3 Approaches

- Mindmap Handout

- Hierarchies Handout

- Word Bank Handout

I Say Research is a Word game Because...

- I have to guess where to begin

- I must track the words I use and find

- words lead to more words

- it's never a straight line

- luck is involved

- I don't know where I will end up.

'Incunabula" means "books printed before 1501." Who knew?

The Word Bank: A Vital Little Research Concept

Words and Synonyms Infographic

This text describes the infographic image above.

Expert researchers organize subject-related words before they being searching -- and continue to save words as they learn new ones.

Here are 3 ways to organize and think about words in searching:

- The Mindmap is a series of bubbles: the big one in the middle is the broad topic, the smaller ones are aspects of the broad topic. Brainstorm the aspects, and use arrows to indicate connections; naming the arrows helps uncover ideas. Example: Women is the broad idea; College, Appalachia, and engineering are related; girls is STEM goes along an arrow. Include synonyms: women could be female or girl.

- Use Hierarchies to consider bigger-to-smaller ideas. In boxes left to right, make the idea smaller and smaller. You can search for things all along the hierarchy, adding words and ideas as they appear. Example: First idea: musicians; smaller idea: rock musicians; smaller: guitar players: smaller: Keith Richards.

- A word bank organizes your words by concept in vertical columns. Take each concept and collect synonyms and related terms under it. Example: Motorcycle, the concept at the top of the column, could also be called bike, Harley, or hog. Culture, a second top idea, could be described as beliefs, attitudes, or psychology.

When I Say Word Bank, you say.....

We use a lot of different words to talk about using words in searching. I need a Word Bank to talk about synonyms.

Expert researchers should brainstorm, identify, find, discover, chose, list, think, mindmap, create, imagine all the synonyms, controlled vocabulary, thesaurus terms, descriptors, identifiers, indexers, keywords, technical names, jargon, scientific names, MESH headings, word stems, hierarchies, common / specific / technical words, abbreviations, spelling variations, definitions, uniform titles, terms, words, descriptions, smallest parts, languages, concepts, terminology, search terms, alternatives, phrases, or similar words before - and during - searching.

- << Previous: Search Techniques

- Next: Types of Resources and Finding Them >>

- Visit the University of Nebraska–Lincoln

- Apply to the University of Nebraska–Lincoln

- Give to the University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Search Form

Overview of research process.

The Research Process

Anything you write involves organization and a logical flow of ideas, so understanding the logic of the research process before beginning to write is essential. Simply put, you need to put your writing in the larger context—see the forest before you even attempt to see the trees.

In this brief introductory module, we’ll review the major steps in the research process, conceptualized here as a series of steps within a circle, with each step dependent on the previous one. The circle best depicts the recursive nature of the process; that is, once the process has been completed, the researcher may begin again by refining or expanding on the initial approach, or even pioneering a completely new approach to solving the problem.

Identify a Research Problem

You identify a research problem by first selecting a general topic that’s interesting to you and to the interests and specialties of your research advisor. Once identified, you’ll need to narrow it. For example, if teenage pregnancy is your general topic area, your specific topic could be a comparison of how teenage pregnancy affects young fathers and mothers differently.

Review the Literature

Find out what’s being asked or what’s already been done in the area by doing some exploratory reading. Discuss the topic with your advisor to gain additional insights, explore novel approaches, and begin to develop your research question, purpose statement, and hypothesis(es), if applicable.

Determine Research Question

A good research question is a question worth asking; one that poses a problem worth solving. A good question should:

- Be clear . It must be understandable to you and to others.

- Be researchable . It should be capable of developing into a manageable research design, so data may be collected in relation to it. Extremely abstract terms are unlikely to be suitable.

- Connect with established theory and research . There should be a literature on which you can draw to illuminate how your research question(s) should be approached.

- Be neither too broad nor too narrow. See Appendix A for a brief explanation of the narrowing process and how your research question, purpose statement, and hypothesis(es) are interconnected.

Appendix A Research Questions, Purpose Statement, Hypothesis(es)

Develop Research Methods

Once you’ve finalized your research question, purpose statement, and hypothesis(es), you’ll need to write your research proposal—a detailed management plan for your research project. The proposal is as essential to successful research as an architect’s plans are to the construction of a building.

See Appendix B to view the basic components of a research proposal.

Appendix B Components of a Research Proposal

Collect & Analyze Data

In Practical Research–Planning and Design (2005, 8th Edition), Leedy and Ormrod provide excellent advice for what the researcher does at this stage in the research process. The researcher now

- collects data that potentially relate to the problem,

- arranges the data into a logical organizational structure,

- analyzes and interprets the data to determine their meaning,

- determines if the data resolve the research problem or not, and

- determines if the data support the hypothesis or not.

Document the Work

Because research reports differ by discipline, the most effective way for you to understand formatting and citations is to examine reports from others in your department or field. The library’s electronic databases provide a wealth of examples illustrating how others in your field document their research.

Communicate Your Research

Talk with your advisor about potential local, regional, or national venues to present your findings. And don’t sell yourself short: Consider publishing your research in related books or journals.

Refine/Expand, Pioneer

Earlier, we emphasized the fact that the research process, rather than being linear, is recursive—the reason we conceptualized the process as a series of steps within a circle. At this stage, you may need to revisit your research problem in the context of your findings. You might also investigate the implications of your work and identify new problems or refine your previous approach.

The process then begins anew . . . and you’ll once again move through the series of steps in the circle.

Continue to Module Two

Appendix C - Key Research Terms

Comprehensive Healthcare Simulation: Operations, Technology, and Innovative Practice pp 101–110 Cite as

The Research Process

- Stormy M. Monks 6 &

- Rachel Bailey 7

- First Online: 18 July 2019

1120 Accesses

Part of the book series: Comprehensive Healthcare Simulation ((CHS))

Research is a process that requires not only time but considerable effort. Research is intended to answer a specific question that is pertinent to a field of study. The research question or study purpose determines the type of research approach taken. Prior to conducting research, it is important to determine if the research must be approved by an institutional review board to ensure that it is being conducted in an ethically sound manner. After the study implementation, the researcher has the obligation to write about the research process. This assists other researchers by providing additional knowledge to the literature surrounding the research topic.

- Quantitative

- Qualitative

- Experimental

- Quasi-experimental

- Nonexperimental

- Institutional review board

- Introduction

- Purpose statement

- Discussion/conclusions

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

US Department of Health and Human Services. Code of federal regulations. Title 45 Public welfare. Department of Health and Human Services. Part 46: Protection of human subjects. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2009.

Google Scholar

Cottrell RR, McKenzie JF. Health promotion and education research methods: using the five-chapter thesis/dissertation model. Sudbury: Jones & Bartlett; 2010.

Hulley SB, Cummings SR, Browner WS, Grady DG, Newman TB. Designing clinical research. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013.

Huang X, Lin J, Demner-Fushman D, editors. Evaluation of PICO as a knowledge representation for clinical questions. AMIA annual symposium proceedings, American Medical Informatics Association; 2006.

Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, Keitz S, Fontelo P. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2007;7(1):16.

Article Google Scholar

Cook TD, Campbell DT, Shadish W. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Boston; 2002.

Rocco TS, Hatcher TG. The handbook of scholarly writing and publishing. New York: Wiley; 2011.

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMC Med. 2010;8(1):18.

Gastel B, Day RA. How to write and publish a scientific paper. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO; 2016.

Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI) Program. 2000. Available from: https://www.citiprogram.org/

US Department of Health and Human Services. The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research, National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, 45. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1979.

Bem D. Writing the empirical journal article. In: Darley JM, Zanna MP, Roediger III HL, editors. The compleat academic: a practical guide for the beginning social scientist. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association (APA); 2004.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Emergency Medicine, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center El Paso, El Paso, TX, USA

Stormy M. Monks

Engineering and Computer Simulations, Orlando, FL, USA

Rachel Bailey

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Stormy M. Monks .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Scott B. Crawford

SimGHOSTS, Las Vegas, NV, USA

Lance W. Baily

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Monks, S.M., Bailey, R. (2019). The Research Process. In: Crawford, S., Baily, L., Monks, S. (eds) Comprehensive Healthcare Simulation: Operations, Technology, and Innovative Practice. Comprehensive Healthcare Simulation. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15378-6_8

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15378-6_8

Published : 18 July 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-15377-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-15378-6

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

This unit explores the concept of research. You will define the term “research” for yourself. Next, you’ll examine several models of the research process and borrow from these models to create one that describes your own research process.

What Is Research?

To start, let’s compare the word “report” and “research.”

When you write a report, you locate information on a topic and summarize it. That’s generally it. Technically, a report does not ask you to analyze, compare, or synthesize information. It does not require you to locate facts to support an argument.

Research, on the other hand, means to investigate.. Research involves posing an original question, looking at something from all angles, studying it carefully, and examining it deeply.

Listen to what these Northwestern University students have to say about research:

Assignment 1:

In the discussion thread labeled “What Is Research,” identify one or two responses from the Northwestern students that you found meaningful. Write a few sentences explaining why you found those responses meaningful.

Rate Yourself As a Researcher

Note: Create a Google Form for this. Students submit to the form. Place the form in iLearn.

Think about the skills you have to complete research. Rate yourself using the following scale:

1 = I know nothing about this

2 = I am a beginner at this

3 = I can do this, but I still have a lot to learn about doing this well.

4 = I am an expert at this

Based on your own scores, what do you need to work on as a researcher?

Research Process Models

We know from decades of studies that when people do research, they follow a process with some predictable stages. There are many models of this process. Here are three. As you read, think about what these models have in common.

The Search Process

Step 1: Choosing a Topic and Asking Questions Define your research problem, explore topics, do some background building, and create questions to guide your research.

Step 2: Identifying resources Figure out what resources you’ll need to best answer your questions and solve your research problem. These might include people, books, magazines, newspapers, videos, websites, and any other source of information.

Step 3: Planning your search Narrow or broaden your topic, create subject and keyword lists to search, prioritize your questions, create interview questions, schedule interviews, and organize your search time.