- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 27 May 2020

Knowledge, attitude and willingness to donate organ among medical students of Jimma University, Jimma Ethiopia: cross-sectional study

- Fantu Kerga Dibaba ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4331-3907 1 ,

- Kabaye Kumela Goro 1 ,

- Amare Desalegn Wolide 2 ,

- Fanta Gashe Fufa 1 ,

- Aster Wakjira Garedow 1 ,

- Birtukan Edilu Tufa 3 &

- Eshetu Mulisa Bobasa 1

BMC Public Health volume 20 , Article number: 799 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

7123 Accesses

15 Citations

7 Altmetric

Metrics details

The lack of organ donors has become a limiting factor for the development of organ transplantation programs. Many countries are currently facing a severe shortage of organs for transplantation. Medical students, as future doctors can engage in the role of promoting organ donation by creating awareness and motivating the community to donate their organs besides their voluntary organ donation. The aim of this study is to assess the knowledge, attitude and willingness of undergraduate medical students’ towards organ donation at Jimma University.

A cross-sectional study was conducted among 320 medical students from year I to internship using questionnaire in order to assess their knowledge, attitude and willingness regarding organ donation. Data collected was entered using epidata and analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 20.

Mean (±SD = standard deviation) age of participants was 23.48 ± 17.025 years. 57.8% of the study subjects were male. There was a statistically significant interaction effect between gender and year of study on the combined knowledge questions (dependent variables) F(25,062) = 1.755, P = 0.014, Wilk’s Λ = .033. Variables which were related to a positive attitude towards organ donation were: being of the male sex (Odds Ratio = 1.156); having awareness about organ donation (Odds Ratio = 2.602); not having a belief on the importance of burying intact body (Odds Ratio = 5.434); willingness to donate blood (Odds Ratio = 4.813); and willingness to donate organ (Odds Ratio = 19.424).

High level of knowledge but low level of positive attitude and willingness was noticed among the study participants toward organ donation.

Peer Review reports

The need for organ donation has increased globally in the past years due to an increase in organ failure [ 1 ]. Every day in the United States of America (USA), 21 people die waiting for an organ and more than 120,048 men, women, and children await life-saving organ transplants [ 2 ]. Accor-ding to a survey In India every year about 5 lakh (500,000) people die because of non-availability of organs and 1.5 lakh(150,000) people await a kidney transplant but only 5000 get among them [ 3 ]. Recently published report has found that approximately 3 million people in sub-Saharan Africa diagnosed with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) die each year due to renal failure [ 4 ]. In Kenya, the kidney transplant queue at Kenyatta National Hospital in Nairobi stretches all the way to 2018, despite the hospital performing the procedure on a weekly basis [ 5 ]. In Ethiopia, between 130 and 150 corneas are collected yearly. However, there are more than 300,000 blind people waiting for corneal transplantation [ 6 ].

There are no sufficient facilities which provide maintenance and transplantation therapy for failed organs in Ethiopia. Currently there are only cornea and living related kidney transplant programs established in the nation’s capital Addis Ababa [ 6 ]. Facilities which provide maintenance dialysis has been in existence in the country starting from 2001. Hemodialysis has become on hand in private institutions, mostly in Addis Ababa the capital city of the country, and more recently in a few other urban and semi-urban regions. Currently, there are 30 hemodialysis centers with a total of 186 hemodialysis chairs and approximately 800 patients on hemodialysis. Among patients on maintenance dialysis, only about one-third receives treatment 3× per year because the cost of hemodialysis is unaffordable for the majority of patients [ 7 ].

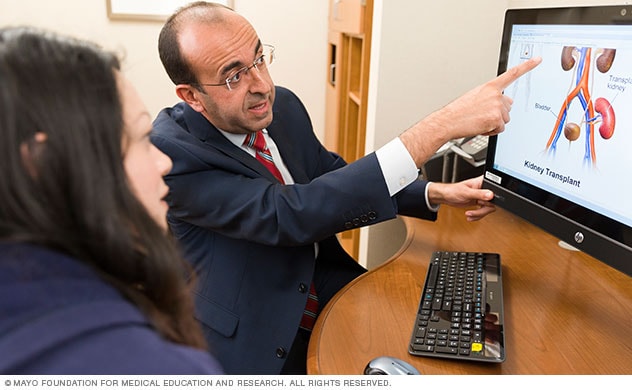

Organ transplantation is one of the great advances in modern medicine and is the best option for failed organ. Transplantation is defined as the transfer of human cells, tissues or organs from a donor to recipient with an aim of restoring normal physiology in the body [ 8 ]. In Ethiopia, up to 2018, 1336 corneal and 90 living donor kidney transplants have been performed. Currently the kidney transplant program accepts candidates only at the age of 14 and above [ 7 , 9 ].

Some studies found out that the issue of organ donation is multifactorial. In developed countries relational ties, religious beliefs, cultural influences, family influences, body integrity, and previous interactions with the health-care system were reported as the potential factors for organ donation [ 10 ]. However, there are limited studies regarding organ donation and the factors that influence it in developing countries for instance, in Kenya there are peoples who believe a person’s body should be intact when buried this belief and other sociocultural and legal factors hinder the harvest of organ from patients who have been medically declared to be in a “state of dying” [ 5 ].

Among 100,000 of people died each year are believed to be potential donors; however, only less than 200 actually become donors [ 11 ]. This indicates that a lot should be done on awareness creation towards organ donation. As a new approach in solving the organ shortage, it has been suggested that awareness about organ donation to be made a part of school education [ 12 ]. In Ethiopia we suggest to use religious leaders besides to incorporating the issue in school education, because Ethiopia is religious country. Our country has close ties with all three major Abrahamic religions, and it was the first in the region to officially adopt Christianity in the fourth century. Christians account for 63% of the country’s population, with 43.5% belonging to the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, 18.5% Protestant and 0.7% Catholic. Ethiopia has the first Hijra in Islamic history and the oldest Muslim settlement on the continent. Muslims account for 34% of the population, traditional 2.7% and other 0.6% [ 13 ].

In Ethiopia there are no data on public perception of organ donation and transplantation Therefore, the present study was designed to assess the knowledge, attitude and willingness of organ donation among medical students. Medical students, as future doctors can take up the role of promoting organ donation by educating and motivating the public to initiate them donate their organs besides their voluntary organ donation. Therefore, assessing medical student’s knowledge, attitude and willingness to donate organ is very important to decrease the shortage of organ in the future.

Study setting and subjects

A cross sectional study was carried out for 3 months from May to July 2019among under graduate medical students in Jimma University after obtaining Institutional Ethical Clearance from institutional review board (IRB) of Jimma University. The University is located in Jimma town which is 352 km from Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. Jimma University is one of the most distinguished centers of excellence in medical education in the country.

Sample size

All medical students (from first to internship) registered in the year 2018/2019 were the source population. Based on their training background, medical students in Jimma University were divided into two groups: PRE-CLINICAL and CLINICAL. PRECLINICAL is subdivided in to two groups: Year I (PC-I) and Year II (PC-II) and CLINICAL in to three subgroups Year III(C-I), Year IV(C-II) and internship. The sample size was calculated by using simple proportion formula assuming a prevalence of 50% for knowledge, attitudes and willingness of organ donation, a 95% confidence interval and a sample error of 5%. This was adjusted for 10% non-response rate; bringing the total sample size to 320.There were about 1200 students studying in Jimma University medical school.

The questionnaire was distributed to undergraduate medical students during lecture hours in the classroom and in ward during attachment. They were instructed not to discuss the questions among themselves. The importance of the study was explained and confidentiality regarding the participant response for the questions was ensured.

A 20-item self-administered questionnaire was developed. The first part of the questionnaire gathered the demographic details from the students, which included age, gender, year of study and religion. The second, third and fourth sections assessed the levels of knowledge (Q1–7), attitude (Q8–16) and willingness (Q17–20) to donate organ, respectively.

The students were grouped as those who do have adequate and inadequate knowledge based on their score.

Adequate knowledge is when 4–6 questions were answered correctly and inadequate when less than 4 questions answered correctly out of 6 knowledge questions.

Attitude was assessed by using 9 attitude statements and respondents were categorized as those who do have positive attitude and negative if they agree to 6–9 and less than 6 attitude statements respectively.

Statistical analysis

Data was entered to EPI data and exported to SPSS version 20 for analysis. Descriptive statistics like percentage and mean and standard deviation were used to present socio-demography, knowledge, attitude and willingness response of the participants. Multivariate analysis was used in order to relate those factors that gave a significant result: One way Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to see a significant relationship between one independent variable and dependent variables and two ways MANOVA was considered to know if there was an interaction between two independent variables on the dependent variables. One way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used for comparing means of variables to know among which groups were the differences. Finally, Odds ratio analysis was used to find out variables which were related to a positive attitude towards organ donation.

Out of 320 participants 57.8% were male. Mean (±SD = standard deviation) age of participants was 23.48 ± 17.025 years. Majority of the participants were orthodox (49%.7) and the least percentage being others constituting wakeefeta, apostolic, humanity, atheist and Seventh Day Adventist (SDA) (2.8%) (Table 1 ).

96.9% of the students had awareness about organ donation. Only 25% had knowledge that there was no age limit for organ donation (Table 2 ).

There was a statistically significant difference in level of knowledge between study groups as demonstrated by one-way ANOVA(F (4,315) =7.6, p = 0.001). Based on the post hoc test the significant difference was between PC-I and C-II( p = 0.001), PC-I and intern( p = 0.001), PC-II and C-I( P = 0.022) and PC-II and intern( p = 0.010). The mean for PC-I, PC-II, C-I, C-II and intern is 1.37, 1.27, 1.20, 1.08 and 1.05 respectively. Therefore, PC=I had significantly higher level of knowledge when compared to the rest year of study (Table 3 ).

74.1% of the participants agreed to support family members if they wish to become an organ donor. Majority of the study subjects (91.9%) felt that awareness about organ donation should be made a part of school education (Table 4 ).

According to our finding, males were 1.156 (Odds Ratio = 1.156) times likely to have positive attitude towards to organ donation as compared to female. Students who had an awareness about organ donation were 2.602 (Odds Ratio = 2.602) times likely to have positive attitude towards to organ donation as compared to those who were unaware. The other variables which were related to a positive attitude towards organ donation were: not having a belief on the importance of burying intact body (Odds Ratio = 5.434); knowing definition of brain death (Odds Ratio = 1.257); not having a belief that there is a danger of misuse, abuse or misappropriation of donated organ (Odds Ratio = 2.777); willingness to donate blood (Odds Ratio = 4.813); and willingness to donate organ (Odds Ratio = 19.424).

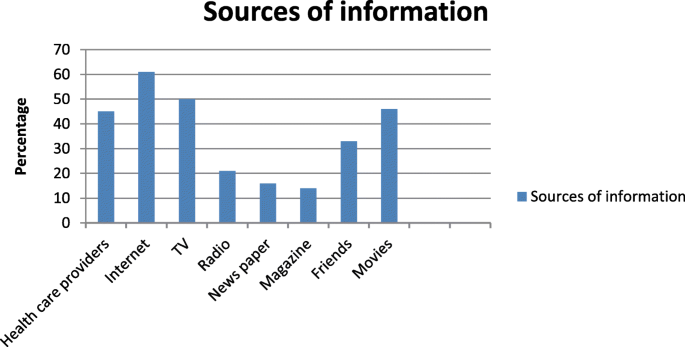

58.1% of the study participants were willing to donate their organs and allow organ donation after the death of a family member. Majority of the study subjects (88.4%) did not like to take money for organ donation. 90.3% of the study subjects were willing to donate blood and 58.1% were willing to donate their organ (Table 5 ) (Fig. 1 ).

Distribution of study subjects according to the source of information about organ donations. i.e. Note: No of respondents may be greater than sample size as multiple options were allowed. Most common source of information about organ donation was found to be internet (61%) television (50%) followed by, Movies and health care providers 46 and 45% respectively

There were an association between willingness and attitude. Willingness to donate organ was significantly higher among those who do have positive attitude (88.2%) as compared to those with negative attitude (11.8%) (Table 6 ).

There was a statistically significant difference on belief of burying intact body between religions as demonstrated by one-way ANOVA(F (3,316) =4.5, p = .004). Based on the post hoc test the significant difference was between Protestant and Muslim ( p = .007). The mean for protestant is 1.83 and Muslim 1.56.Therefore, Protestant had significantly higher belief on the importance of burying intact body when compared to Muslim (Table 7 ).

There was a statistically significant difference between males and females when knowledge questions considered jointly Wilk’s Λ = .96, F (6,312) = 2.247, P = 0.039, multivariate ƞ 2 = 0.041 and attitude statements consider jointly Wilk’s Λ = .94, F (9,310) = 2.301, P = 0.016, multivariate ƞ 2 = 0.063.

When year of study is considered, there was a statistically significant difference among year of studies when knowledge questions considered jointly Wilk’s Λ = .75, F (25,079) = 3.966, P < 0.001, multivariate ƞ 2 = .071, attitude statements considered jointly Wilk’s Λ = .77, F (37,152) = .766, P < 0.001, multivariate ƞ 2 = .065 and willingness questions considered jointly Wilk’s Λ = .93, F (12,828) = 2.072, P = 0.017, multivariate ƞ 2 = .026.

Two way MANOVA was considered to know if there was an interaction between two independent variables on the dependent variables. There was a statistically significant interaction effect between gender and year of study on the combined knowledge questions (dependent variables) F (25,062) = 1.755, P = 0.014, Wilk’s Λ = .033.

Knowledge of the participant

Organ failure and shortage of donated organs are global problem. Among 100,000 of people died each year are believed to be potential donors; however, only less than 200 actually become donors [ 9 ]. The widespread shortage of donated organs indicates that there is low donor rate worldwide; In Ethiopia there is no data on rate of organ donation. In 2017 Spain had the highest donor rate in the world at 46.9 per million people, followed by Portugal (34.0 per million), Belgium (33.6 per million), Croatia (33.0 per million) and the US (32.0 per million) [ 14 ]. Donated organs are the major pre-requisite for consistency of organ transplantation program; one of the solutions to increase organ supply is to assess public knowledge, attitude and willingness towards organ donation and taking an action based on the data. In our country there is no study done on people’s perception towards organ donation this background pledges us to conduct this study.

In our study 96.9% of the participants heard about organ donation which is similar to study done by Annadurai et al and Jothula et al. [ 15 , 16 ] both reported that 100% of the participants were aware about organ donation.74.1% of the participants were aware about the meaning of organ donation which is relatively higher than the study done by Annadurai et al. [ 15 ]. In the present study, level of knowledge was significantly higher among PC=I (year I) students as compared to the other year of study this finding was similar to study done among undergraduate dental students of Panineeya Institute of Dental Sciences and Hospital, which showed higher average knowledge among first-year students [ 17 ]. In this study, only 82.5%of medical students had adequate knowledge about organ donation which is relatively higher than the study done on final semester medical students by Karini et al. which showed that only 56% of them were having adequate knowledge [ 18 ].

In the present study the main sources of information about organ donation was found to be internet (61%) and television (50%).This was similar to study conducted in USA and Australia [ 19 , 20 ]. However; Similar findings were observed by Sindhu et al. and Jothula KY et al. [ 16 , 21 ]. The third source of information about organ donation in our study are health care providers (45%) which is relatively higher than the study done by Annadurai et al. [ 15 ] which reported 34.1%. this finding showed that health care providers are playing undeniable role in creating awareness towards organ donation in Ethiopia.

206(64.4%) of our study participants had identified all the organs that can be donated. This finding was higher than the study done by Annadurai et al. [ 15 ] and Karini et al. [ 18 ] which reported 16.1 and 26% respectively. In the present study 80(25%) of the students knew that there is no age limit for organ donation which is approximate to Sucharitha et al. and lower than Jothula KY et al. [ 16 , 22 ].

Attitude of medical students regarding organ donation

201(62.8%) of our study subjects have a positive attitude towards organ donation which is lower than the study in Spain and India which found 80 and 71.3% respectively [ 23 , 24 ]. 91.9% of this study subjects, felt that awareness about organ donation should be included in school curriculum which is similar to Adithyan et al. reported that 91.2% of the subjects felt the need for revision of medical curriculum on organ donation [ 25 ] Our study found out that 251(78.4%) of the study subjects would like to motivate others for organ donation which is lower than to the Vinay et al [ 26 ].

77(24.1%) of our study subjects belief that person’s body should be intact when buried A study in USA reported that 8% of participants strongly agree and 11.7% agree to this statement which is almost similar to our finding [ 19 ]. In our study being of the male sex (Odds Ratio = 1.156) was related to a favorable attitude towards to organ donation; in contrast, a study done in Spain reported that being of females sex (Odds Ratio = 1.739) was related to a favorable attitude [ 23 ]. In our study not having a belief on the importance of burying intact body (Odds Ratio = Ratio = 5.434) was one of the variables which affect positive attitude towards to organ donation which was similar to a study in USA [ 19 ]. A study done in Spain reported being a blood donor (OR = 2.824) as a variable related to a positive attitude towards to organ donation similarly in our study we found out willingness to donate blood (Odds Ratio = 4.813) as a variable to a favorable attitude.

Willingness of medical students to donate organ

In this study 186(58.1%) of the study participants were willing to donate their organ which is similar to a study done in USA [ 20 ] and lower than Payghan et al. and Vinay et al revealed that almost 90% of study participants were willing to donate their organs [ 26 , 27 ]. The present study found out that there is a significant association between attitude regarding organ donation and willingness to donate organs which is different from the finding by Ali et al. and by Dasgupta et al. [ 28 , 29 ] which reported that there was a significant association between attitude and knowledge acquired. Though taking money for organ donation is unethical 11.6% of our study participants would like to take money for organ donation which was higher than study by Jothula KY et al. [ 16 ].

Though most of the students had adequate knowledge, still gaps exist in their attitude and willingness. This implies the need for an intensified and sustained education to raise attitude and willingness of the students towards organ donation.

Recommendations

Most of the students (91.9%) felt that awareness about organ donation should be made a part of school education; until it included in school curriculum, we recommend the students to acquire an adequate knowledge by themselves; In our study the most common source of information about organ donation was internet; so, they can browse more to acquire additional knowledge and make informed decision.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Analysis of variance

Clinical-II

End-stage kidney disease

Institutional Review Board

Jimma University Medical College

Multivariate analysis of variance

Pre-clinical-I

Pre-clinical-II

Seventh Day Adventist

Statistical Package for Social Sciences

United States of America

Wakefield MA, Loken B, Hornik RC. Use of mass media campaigns to change health behaviour. Lancet. 2010;376(9748):1261–71.

Article Google Scholar

Organ Donation Facts & Info _ Organ Transplants _ Cleveland Clinic www.unos.org , Nov. 1, 2016. Accessed 26 Jan 2020.

National Health Portal. “Organ donation day”. Available at http://www.nhp.gov.in/organdonation-day_pg . Accessed 18 Feb 2018.

Ashuntantang G, Osafo C, Olowu WA, et al. Outcomes in adults and children with end-stage kidney disease requiring dialysis in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5:e408–17.

Organ failure: patients in East Africa wait endlessly for donors. Science & Health https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke . Accessed 26 Aug 2019.

Rao GN, Gopinathan U. Eye banking: an introduction. Community Eye Health. 2009;22(71):46–7.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ahmed, et al. Organ transplantation in Ethiopia. 2019;103(3):449–51.

World Health Organisation (WHO). Global glossary of terms and definitions on donation and transplantation, vol. 14. Geneva; 2009.

13. Eye Bank of Ethiopia celebrates 15 th anniversary June 28, 2018 by New Business Ethiopia. http://newbusinessethiopia.com/health/eye-bank-of-ethiopia-celebrates-15th-anniversary/ .

Irving MJ, Tong A, Jan S, Cass A, Rose J, Chadban S, et al. Factors that influence the decision to be an organ donor: a systematic review of the qualitative literature. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:2526–33.

Sahi M. Myths and misconceptions and reality on organ donation. Transplantation Research. https://www.mohanfoundation.org/organ-donation-transplant-resources/Myths-Misconceptions-and-the-Reality-of-Organ-Donation.asp .

Burra P, De Bona M, Canova D, et al. Changing attitude to organ donation and transplantation in university students during the years of medical school in Italy. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:547–50.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Ethiopia PEOPLE 2019, CIA World Fact book Theodora.com https://theodora.com/wfbcurrent/ethiopia/ethiopia_people.html .

Newsletter 2018 (PDF). International registry in organ donation and transplantation. 2018 . Retrieved December 30, 2018 . .

Google Scholar

Annadurai K, Mani K, Ramasamy J. A study on knowledge, attitude and practices about organ donation among college students in Chennai, Tamil Nadu −2012. Prog Health Sci. 2013;3:2 KAP on organ donation.

Jothula KY, Sreeharshika D. Study to assess knowledge, attitude and practice regarding organ donation among interns of a medical college in Telangana, India. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2018;5:1339–45.

Chakradhar K, Doshi D, Srikanth Reddy B, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice regarding organ donation among Indian dental students. Int J Organ Transplant Med. 2016;7(1):28–35.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Karini D, Sunitha S, Devi Madhavi B. Perceptions of medical students in a government medical college towards organ donation. J Evid Based Med Healthc. 2015;2(44):7998–8005.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Healthcare Systems Bureau, 2012 National Survey of Organ Donation Attitudes and Behaviors. Rockville, Maryland: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2013.

Hyde MK, Chambers SK. Information sources, donation knowledge, and attitudes toward transplant recipients in Australia. Prog Transplant. 2014;24:169–77.

Sindhu A, Ramakrishnan TS, Khera A, Singh G. A study to assess the knowledge of medical students regarding organ donation in a selected college of Western Maharashtra. Med J DY Patil Univ. 2017;10:349–53.

Agarwal S. Are medical students having enough knowledge about organ donation. IOSR J Dental Med Sci. 2015;14(7):29–34.

Ríos A, López-Navas A, López-López A, Gómez FJ, Iriarte J, Herruzo R, Blanco G, Llorca FJ, Asunsolo A, Sánchez P, Gutiérrez PR, Fernández A, de Jesús MT, MartínezAlarcón L, Lana A, Fuentes L, Hernández JR, Virseda J, Yelamos J, Bondía JA, Hernández AM, Ayala MA, Ramírez P, Parrilla P. A multicentre and stratified study of the attitude of medical students towards organ donation in Spain. Ethn Health. 2019;24(4):443–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2017.1346183 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bathija GV, Ananthesh BG, Bant DD. Study to assess knowledge and attitude towards organ donation among interns and post graduates of a medical college in Karnataka, India. Natl J Community Med. 2017;8(5):236–40.

Adithyan GS, Mariappan M, Nayana KB. A study on knowledge and attitude about organ donation among medical students in Kerala. Indian J Transplant. 2017;11:133–7.

Vinay KV, Beena N, Sachin KS, Praveen S. Changes in knowledge and attitude among medical students towards organ donation and transplantation. Int J Anat Res. 2016;4(3):2873–7.

Payghan BS, Kadam SS, Furmeen S. Organ donation: awareness and perception among medical students. J Pharm Sci Innov. 2014;3(4):379–81.

Ali NF, Qureshi A, Jilani BN, Zehra N. Knowledge and ethical perception regarding organ donation among medical students. BMC Med Ethics. 2013;14:38.

Dasgupta A, Shahbabu B, Sarkar K, Sarkar I, Das S, Das MK. Perception of organ donation among adults: a community based study in an urban. Sch J App Med Sci. 2014;2(6A):2016–2021.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

The study was funded with the support of Jimma University; Faculty of Health Science. The funding body has no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Health Sciences, School of Pharmacy, Jimma University, 378, Jimma, Ethiopia

Fantu Kerga Dibaba, Kabaye Kumela Goro, Fanta Gashe Fufa, Aster Wakjira Garedow & Eshetu Mulisa Bobasa

Facility of Medicine, Jimma University, 378, Jimma, Ethiopia

Amare Desalegn Wolide

Faculty of Health Sciences, School of Midwifery and Nursing, Jimma University, 378, Jimma, Ethiopia

Birtukan Edilu Tufa

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

FKD, EMB, KKG, ADW, FGF, AWG, BET involved in the data collection. FKD analyze the data and FKD and EMB prepared the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Fantu Kerga Dibaba .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of Jimma University, College of Health Sciences and ethical clearance was obtained with the Reference Number IHRPGD/3019/2019. Permission of data collection was granted with formal letter from chief executive director of Jimma University Medical College (JUMC). The purpose and protocol of this study was explained, participants signed informed written consent.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Dibaba, F.K., Goro, K.K., Wolide, A.D. et al. Knowledge, attitude and willingness to donate organ among medical students of Jimma University, Jimma Ethiopia: cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 20 , 799 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08931-y

Download citation

Received : 19 September 2019

Accepted : 17 May 2020

Published : 27 May 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08931-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Organ donation

- Willingness

- Medical students

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Featured Clinical Reviews

- Screening for Atrial Fibrillation: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement JAMA Recommendation Statement January 25, 2022

- Evaluating the Patient With a Pulmonary Nodule: A Review JAMA Review January 18, 2022

- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

Organ Donor Research : Overcoming Challenges, Increasing Opportunities

- 1 University of Virginia, Charlottesville

A substantial gap exists between the need for organ transplants and the number of transplants performed each year in the United States. In 2016, 27 630 organs were transplanted from 9971 deceased donors and 5980 additional organs from living donors, but as of September 29, 2017, a total of 116 602 individuals were included on the nation’s organ transplant wait lists. 1 This gap remains despite increases in the number of both donated organs and organ transplants in recent years. In 2015, close to 5000 organs from deceased donors were discarded because they were deemed unsuitable for transplantation. 1

Read More About

Childress JF. Organ Donor Research : Overcoming Challenges, Increasing Opportunities . JAMA. 2017;318(22):2177–2178. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.16442

Manage citations:

© 2024

Artificial Intelligence Resource Center

Cardiology in JAMA : Read the Latest

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Organ Donation for Social Change: A Systematic Review

- First Online: 07 January 2020

Cite this chapter

- Amani Alsalem 2 ,

- Park Thaichon 2 &

- Scott Weaven 2

Part of the book series: Contributions to Management Science ((MANAGEMENT SC.))

1720 Accesses

2 Citations

This chapter presents a critical review of the existing organ donation literature. The objective of this chapter is to identify the main gaps in the current body of literature on the organ donation context and the marketing discipline. This chapter initially discusses social marketing within the context of organ donation for social change. Following on, this chapter provides a systematic quantitative literature review of the existing organ donation studies from the period of 1985–2019. Then, this chapter details and discusses the review method. The literature review findings include the geographical distribution of 262 peer-reviewed organ donation studies around the world; the frequency of published articles over the period 1985–2019; the disciplinary scope of these studies; the sample characteristics; and the key theories and models used to inform organ donation studies. Finally, this chapter concludes with a discussion of the main limitations of existing organ donation studies.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Afifi, W. A., Morgan, S. E., Stephenson, M. T., Morse, C., Harrison, T., Reichert, T., & Long, S. D. (2006). Examining the decision to talk with family about organ donation: Applying the theory of motivated information management. Communication Monographs, 73 (2), 188–215.

Google Scholar

Agrawal, S., Binsaleem, S., Al-Homrani, M., Al-Juhayim, A., & Al-Harbi, A. (2017). Knowledge and attitude towards organ donation among adult population in Al-Kharj, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases and Transplantation, 28 (1), 81.

Al Sebayel, M., & Khalaf, H. (2004). Knowledge and attitude of intensivists toward organ donation in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Paper presented at the Transplantation Proceedings.

Almufleh, A., Althebaity, R., Alamri, A. S., Al-Rashed, N. A., Alshehri, E. H., Albalawi, L. … Alsaif, F. A. (2018). Organ donation awareness and attitude among Riyadh City Residents, Saudi Arabia. Journal of Nature and Science of Medicine, 1 (2), 59.

AlShareef, S. M., & Smith, R. M. (2018). Saudi medical students knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs with regard to organ donation and transplantation. Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases and Transplantation, 29 (5), 1115.

Alvaro, E. M., Jones, S. P., Robles, A. S. M., & Siegel, J. (2006). Hispanic organ donation: Impact of a Spanish-language organ donation campaign. Journal of the National Medical Association, 98 (1), 28.

Anker, A. E., Feeley, T. H., & Kim, H. (2010). Examining the attitude–behavior relationship in prosocial donation domains. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40 (6), 1293–1324.

Bae, H.-S. (2008). Entertainment-education and recruitment of cornea donors: The role of emotion and issue involvement. Journal of health communication, 13 (1), 20–36.

Balwani, M., Pasari, A., Aziz, F., Patel, M., Kute, V., Shah, P., & Gumber, M. (2018). Knowledge Regarding brain death and organ donation laws among medical students. Transplantation, 102 , S812.

Blitstein, J. L., Cates, S. C., Hersey, J., Montgomery, D., Shelley, M., Hradek, C. … Williams, P. A. (2016). Adding a social marketing campaign to a school-based nutrition education program improves children’s dietary intake: A quasi-experimental study. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 116 (8), 1285-1294.

Boey, K. W. (2002). A cross-validation study of nurses’ attitudes and commitment to organ donation in Hong Kong. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 39 (1), 95–104.

Brennan, L., Binney, W., Parker, L., Aleti, T., & Nguyen, D. (2014). Social marketing and behaviour change: Models, theory and applications . Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Cárdenas, V., Thornton, J. D., Wong, K. A., Spigner, C., & Allen, M. D. (2010). Effects of classroom education on knowledge and attitudes regarding organ donation in ethnically diverse urban high schools. Clinical Transplantation, 24 (6), 784–793.

Chan, E. Y. (2018). The politics of intent: Political ideology influences organ donation intentions. Personality and Individual Differences, 142, 255–259.

Cheng, H., Kotler, P., & Lee, D. (2010). Social marketing for public health. In Social marketing for public health: Global trends and success stories , p. 1.

Chien, Y.-H., & Chang, W.-T. (2015). Effects of message framing and exemplars on promoting organ donation. Psychological Reports, 117 (3), 692–702.

Cohen, E. L. (2010). The role of message frame, perceived risk, and ambivalence in individuals’ decisions to become organ donors. Health Communication, 25 (8), 758–769.

Collins, T. J. (2005). Organ and tissue donation: A survey of nurse’s knowledge and educational needs in an adult ITU. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing, 21 (4), 226–233.

Conner, M., & Norman, P. (2005). Predicting health behaviour . New York, UK: McGraw-Hill Education.

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches . Thousand Oaks: Sage publications.

Dahl, A. J., Barber, K., & Peltier, J. (2019). Social media’s effectiveness for activating social declarations and motivating personal discussions to improve organ donation consent rates. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 13 (1), 47–61.

Dann, G., Nash, D., & Pearce, P. (1988). Methodology in tourism research. Annals of Tourism Research, 15 (1), 1–28.

Dijker, A. J., Nelissen, R. M., & Stijnen, M. M. (2013). Framing posthumous organ donation in terms of reciprocity: What are the emotional consequences? Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 35 (3), 256–264.

Dippel, E. A., Hanson, J. D., McMahon, T. R., Griese, E. R., & Kenyon, D. B. (2017). Applying the theory of reasoned action to understanding teen pregnancy with American Indian communities. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 21 (7), 1449–1456.

Fahrenwald, N. L., & Stabnow, W. (2005). Sociocultural perspective on organ and tissue donation among reservation-dwelling American Indian adults. Ethnicity and Health, 10 (4), 341–354.

Falomir-Pichastor, J. M., Berent, J. A., & Pereira, A. (2013). Social psychological factors of post-mortem organ donation: A theoretical review of determinants and promotion strategies. Health Psychology Review, 7 (2), 202–247.

Feeley, T. H. (2007). College students’ knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors regarding organ donation: An integrated review of the literature1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 37 (2), 243–271.

Fitzgerald, R., Fitzgerald, A., Shaheen, F., & DuBois, J. (2002). Support for organ procurement: National, professional, and religious correlates among medical personnel in Austria and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Paper presented at the Transplantation Proceedings.

Flemming, S. S. C., Redmond, N., Williamson, D. H., Thompson, N. J., Perryman, J. P., Patzer, R. E., et al. (2018). Understanding the pros and cons of organ donation decision-making: Decisional balance and expressing donation intentions among African Americans. Journal of Health Psychology, 1359105318766212.

Flower, J. R. L., & Balamurugan, E. (2013). A study on public intention to donate organ: Perceived barriers and facilitators. British Journal of Medical Practitioners, 6 (4), 6–10.

French, J., & Gordon, R. (2015). Strategic social marketing . Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Gibbons, F. X., Houlihan, A. E., & Gerrard, M. (2009). Reason and reaction: The utility of a dual-focus, dual-processing perspective on promotion and prevention of adolescent health risk behaviour. British Journal of Health Psychology, 14 (2), 231–248.

Ginossar, T., Benavidez, J., Gillooly, Z. D., Kanwal Attreya, A., Nguyen, H., & Bentley, J. (2017). Ethnic/Racial, religious, and demographic predictors of organ donor registration status among young adults in the southwestern United States. Progress in Transplantation, 27 (1), 16–22.

Goldberg, M. E., Fishbein, M., & Middlestadt, S. E. (2018). Social marketing: Theoretical and practical perspectives . London: Psychology Press.

Hansen, S. L., Eisner, M. I., Pfaller, L., & Schicktanz, S. (2018). “Are you in or are you out?!” Moral Appeals to the public in organ donation poster campaigns: A multimodal and ethical analysis. Health Communication, 33 (8), 1020–1034.

Harrison, T., Morgan, S., & Di Corcia, M. (2008). Effects of information, education, and communication training about organ donation for gatekeepers: Clerks at the department of motor vehicles and organ donor registries. Progress in Transplantation, 18 (4), 301–309.

Harrison, T. R., Morgan, S. E., Chewning, L. V., Williams, E. A., Barbour, J. B., Di Corcia, M. J., & Davis, L. A. (2011). Revisiting the worksite in worksite health campaigns: Evidence from a multisite organ donation campaign. Journal of Communication, 61 (3), 535–555.

Healy, J., & Murphy, M. (2017). Social marketing: The lifeblood of blood donation? The customer is NOT always right? Marketing orientations in a dynamic business world (pp. 811–811). Springer, Cham.

Hesse-Biber, S. N. (2010). Mixed methods research: Merging theory with practice . New York, USA: Guilford Press.

Horton, R. L., & Horton, P. J. (1991). A model of willingness to become a potential organ donor. Social Science and Medicine, 33 (9), 1037–1051.

Hyde, M. K., & White, K. M. (2010). Are organ donation communication decisions reasoned or reactive? A test of the utility of an augmented theory of planned behaviour with the prototype/willingness model. British Journal of Health Psychology, 15 (2), 435–452.

Hyde, M. K., & White, K. M. (2014). Perceptions of organ donors and willingness to donate organs upon death: A test of the prototype/willingness model. Death studies, 38 (7), 459–464.

Hyman, M., Shabbir, H., Chari, S., & Oikonomou, A. (2014). Anti-child-abuse ads: Believability and willingness-to-act. Journal of Social Marketing, 4 (1), 58–76.

Jeong, H., & Park, H. S. (2015). The effect of parasocial interaction on intention to register as organ donors through entertainment-education programs in Korea. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health, 27 (2), NP2040–NP2048.

Kopfman, & Smith, S. W. (1996). Understanding the audiences of a health communication campaign: A discriminant analysis of potential organ donors based on intent to donate .

Lam, W. A., & McCullough, L. B. (2000). Influence of religious and spiritual values on the willingness of Chinese-Americans to donate organs for transplantation. Clinical Transplantation, 14 (5), 449–456.

Lee, N. R., & Kotler, P. (2011). Social marketing: Influencing behaviors for good . Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Massi Lindsey, L. L. (2005). Anticipated guilt as behavioral motivation: An examination of appeals to help unknown others through bone marrow donation. Human Communication Research, 31 (4), 453–481.

Mohamed, E., & Guella, A. (2013). Public awareness survey about organ donation and transplantation. Paper presented at the Transplantation Proceedings.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151 (4), 264–269.

Morgan, S., & Miller, J. (2002a). Communicating about gifts of life: The effect of knowledge, attitudes, and altruism on behavior and behavioral intentions regarding organ donation. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 30 (2), 163–178.

Morgan, S., Miller, J., & Arasaratnam, L. (2002b). Signing cards, saving lives: An evaluation of the worksite organ donation promotion project. Communication Monographs, 69 (3), 253–273.

Morgan, S. E., Stephenson, M. T., Harrison, T. R., Afifi, W. A., & Long, S. D. (2008). Facts versusFeelings’ How rational is the decision to become an organ donor? Journal of Health Psychology, 13 (5), 644–658.

Morgan, M., Kenten, C., Deedat, S., & Team, D. P. (2013). Attitudes to deceased organ donation and registration as a donor among minority ethnic groups in North America and the UK: A synthesis of quantitative and qualitative research. Ethnicity & health, 18 (4), 367–390.

Morgan, S., & Gibbs, D. (2006). Final report on the Life Share Project . Unpublished manuscript.

Morgan, S. E. (2004). The power of talk: African Americans’ communication with family members about organ donation and its impact on the willingness to donate organs. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 21 (1), 112–124.

Morgan, S. E., King, A. J., Smith, J. R., & Ivic, R. (2010). A kernel of truth? The impact of television storylines exploiting myths about organ donation on the public’s willingness to donate. Journal of Communication, 60 (4), 778–796.

Morse, C. R., Afifi, W. A., Morgan, S. E., Stephenson, M. T., Reichert, T., Harrison, T. R., & Long, S. D. (2009). Religiosity, anxiety, and discussions about organ donation: Understanding a complex system of associations. Health communication, 24 (2), 156–164.

O’Carroll, R. E., Ferguson, E., Hayes, P. C., & Shepherd, L. (2012). Increasing organ donation via anticipated regret (INORDAR): Protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health, 12 (1), 169.

O’Carroll, R. E., Foster, C., McGeechan, G., Sandford, K., & Ferguson, E. (2011). The “ick” factor, anticipated regret, and willingness to become an organ donor. Health Psychology, 30 (2), 236.

Padela, A. I., Rasheed, S., Warren, G. J., Choi, H., & Mathur, A. K. (2011). Factors associated with positive attitudes toward organ donation in Arab Americans. Clinical Transplantation, 25 (5), 800–808.

Padela, A. I., & Zaganjor, H. (2014). Relationships between Islamic religiosity and attitude toward deceased organ donation among American Muslims: A pilot study. Transplantation, 97 (12), 1292–1299.

Park, H. S., Smith, S. W., & Yun, D. (2009). Ethnic differences in intention to enroll in a state organ donor registry and intention to talk with family about organ donation. Health Communication, 24 (7), 647–659.

Pauli, J., Basso, K., & Ruffatto, J. (2017). The influence of beliefs on organ donation intention. International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Healthcare Marketing, 11 (3), 291–308.

Peattie, S., Peattie, K., & Thomas, R. (2012). Social marketing as transformational marketing in public services: The case of Project Bernie. Public Management Review, 14 (7), 987–1010.

Pechmann, C. (2018). Does antismoking advertising combat underage smoking? A review of past practices and research. In Social Marketing (pp. 189–216). Psychology Press, London.

Pérez-Escamilla, R., & Hall Moran, V. (2016). Scaling up breastfeeding programmes in a complex adaptive world. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 12 (3), 375–380.

Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1996). Addressing disturbing and disturbed consumer behavior: Is it necessary to change the way we conduct behavioral science? Journal of Marketing Research, 33 (1), 1–8.

Pfaller, L., Hansen, S. L., Adloff, F., & Schicktanz, S. (2018). ‘Saying no to organ donation’: An empirical typology of reluctance and rejection. Sociology of Health & Illness, 40 (8), 1327–1346.

Pickering, C., Grignon, J., Steven, R., Guitart, D., & Byrne, J. (2015). Publishing not perishing: How research students transition from novice to knowledgeable using systematic quantitative literature reviews. Studies in Higher Education, 40 (10), 1756–1769.

Pykett, J., Jones, R., Welsh, M., & Whitehead, M. (2014). The art of choosing and the politics of social marketing. Policy Studies, 35 (2), 97–114.

Quick, B. L., Morgan, S. E., LaVoie, N. R., & Bosch, D. (2014). Grey’s Anatomy viewing and organ donation attitude formation: Examining mediators bridging this relationship among African Americans, Caucasians, and Latinos. Communication Research, 41 (5), 690–716.

Resnicow, K., Andrews, A. M., Zhang, N., Chapman, R., Beach, D. K., Langford, A. T. … Magee, J. C. (2011). Development of a scale to measure African American attitudes toward organ donation. Journal of Health Psychology . https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105311412836 .

Reubsaet, A., Brug, J., Nijkamp, M., Candel, M., Van Hooff, J., & Van den Borne, H. (2005). The impact of an organ donation registration information program for high school students in the Netherlands. Social Science and Medicine, 60 (7), 1479–1486.

Ríos, A., López-Navas, A., López-López, A., Gómez, F. J., Iriarte, J., Herruzo, R. … Sánchez, P. (2017). A multicentre and stratified study of the attitude of medical students towards organ donation in Spain. Ethnicity & Health , 1–19.

Ríos, A., López‐Navas, A. I., García, J. A., Garrido, G., Ayala‐García, M. A., Sebastián, M. J. … Parrilla, P. (2017). The attitude of Latin American immigrants in Florida (USA) towards deceased organ donation–a cross section cohort study. Transplant International, 30 (10), 1020–1031.

Robbins, R. A. (1990). Signing an organ donor card: Psychological factors. Death Studies, 14 (3), 219–229.

Rocheleau, C. A. (2013). Organ donation intentions and behaviors: Application and extension of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43 (1), 201–213.

Rodrigue, J., Cornell, D., Jackson, S., Kanasky, W., Marhefka, S., & Reed, A. (2004). Are organ donation attitudes and beliefs, empathy, and life orientation related to donor registration status? Progress in Transplantation, 14 (1), 56–60.

Ryckman, R. M., Borne, B., Thornton, B., & Gold, J. A. (2005). Value priorities and organ donation in young adults. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 35 (11), 2421–2435.

Saleem, T., Ishaque, S., Habib, N., Hussain, S. S., Jawed, A., Khan, A. A. … Jehan, I. (2009). Knowledge, attitudes and practices survey on organ donation among a selected adult population of Pakistan. BMC medical ethics, 10 (1), 1.

Salim, A., Berry, C., Ley, E. J., Schulman, D., Navarro, S., & Chan, L. S. (2011). Utilizing the media to help increase organ donation in the Hispanic American population. Clinical Transplantation, 25 (6), E622–E628.

Sayedalamin, Z., Imran, M., Almutairi, O., Lamfon, M., Alnawwar, M., & Baig, M. (2017). Awareness and attitudes towards organ donation among medical students at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Age (years), 21 (1), 64.

Siegel, J. T., Alvaro, E. M., Lac, A., Crano, W. D., & Dominick, A. (2008). Intentions of becoming a living organ donor among Hispanics: A theory-based approach exploring differences between living and nonliving organ donation. Journal of health Communication, 13 (1), 80–99.

Siminoff, L. A., Burant, C., & Youngner, S. J. (2004). Death and organ procurement: Public beliefs and attitudes. Social Science and Medicine, 59 (11), 2325–2334.

Singh, R., Agarwal, T. M., Al-Thani, H., Al Maslamani, Y., & El-Menyar, A. (2018). Validation of a survey questionnaire on organ donation: An Arabic World scenario. Journal of transplantation, 2018 .

Skumanich, S. A., & Kintsfather, D. P. (1996). Promoting the organ donor card: A causal model of persuasion effects. Social Science and Medicine, 43 (3), 401–408.

Smith, S., & Paladino, A. (2010). Eating clean and green? Investigating consumer motivations towards the purchase of organic food. Australasian Marketing Journal (AMJ), 18 (2), 93–104.

Smith, S. W., Kopfman, J. E., Lindsey, L. L. M., Yoo, J., & Morrison, K. (2004). Encouraging family discussion on the decision to donate organs: The role of the willingness to communicate scale. Health communication, 16 (3), 333–346.

Song, J., Drennan, J. C., & Andrews, L. M. (2012). Exploring regional differences in Chinese consumer acceptance of new mobile technology: A qualitative study. Australasian Marketing Journal (AMJ), 20 (1), 80–88.

Soubhanneyaz, A., Kaki, A., & Noorelahi, M. (2015). Survey of public attitude, awareness and beliefs of organ donation in western region of Saudi Arabia. American Journal of Internal Medicine, 3 (6), 264–271.

Spence, T. H. (2018). The theory of reasoned action: Influences on college students’ behaviors regarding recently legalized recreational Marijuana in the State of Nevada.

Sun, H.-J. (2014). A study on the development of public campaign messages for organ donation promotion in Korea. Health Promotion International, 30 (4), 903–918.

Trompeta, J. A., Cooper, B. A., Ascher, N. L., Kools, S. M., Kennedy, C. M., & Chen, J.-L. (2012). Asian American adolescents’ willingness to donate organs and engage in family discussion about organ donation and transplantation. Progress in Transplantation, 22 (1), 33–70.

Truong, V. D. (2014). Social marketing: A systematic review of research 1998–2012. Social Marketing Quarterly, 20 (1), 15–34.

Veloso, C., Rodrigues, J., Resende, L. C. B., & Rezende, L. B. O. (2017). Donate to save: An analysis of the intention to donate organs under the perspective of social marketing. Revista Gestão & Tecnologia, 17 (1), 10–35.

Wang, X. (2012). The role of attitude functions and self-monitoring in predicting intentions to register as organ donors and to discuss organ donation with family. Communication Research, 39 (1), 26–47.

Wenger, A. V., & Szucs, T. D. (2011). Predictors of family communication of one’s organ donation intention in Switzerland. International journal of public health, 56 (2), 217–223.

Wilczek-Rużyczka, E., Milaniak, I., Przybyłowski, P., Wierzbicki, K., & Sadowski, J. (2014). Influence of empathy, beliefs, attitudes, and demographic variables on willingness to donate organs. Paper presented at the Transplantation Proceedings.

Williams, B. C., & Plouffe, C. R. (2007). Assessing the evolution of sales knowledge: A 20-year content analysis. Industrial Marketing Management, 36 (4), 408–419.

Williamson, L. D., Reynolds-Tylus, T., Quick, B. L., & Shuck, M. (2017). African-Americans’ perceptions of organ donation:‘simply boils down to mistrust!’. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 45 (2), 199–217.

Wong, S. (2012). Does superstition help? A study of the role of superstitions and death beliefs on death anxiety amongst Chinese undergraduates in Hong Kong. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 65 (1), 55–70.

Wu, A. M., Tang, C. S., & Yogo, M. (2013). Death anxiety, altruism, self-efficacy, and organ donation intention among Japanese college students: A moderated mediation analysis. Australian Journal of Psychology, 65 (2), 115–123.

Wu, M. S. A. (2009). The negative impact of death anxiety on self-efficacy and willingness to donate organs among chinese adults (Refereed).

Zhang, J., Jemmott, J. B., III, Icard, L. D., Heeren, G. A., Ngwane, Z., Makiwane, M., & O’Leary, A. (2018). Predictors and psychological pathways for binge drinking among South African men. Psychology & Health, 33 (6), 810–826.

Zhang, L., Liu, W., Xie, S., Wang, X., Woo, S. M.-L., Miller, A. R. … Jia, B. (2019). Factors behind negative attitudes toward cadaveric organ donation: A comparison between medical and non–medical students in China. Transplantation .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Marketing, Griffith University, Gold Coast, Australia

Amani Alsalem, Park Thaichon & Scott Weaven

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Park Thaichon .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Marketing, La Trobe University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Vanessa Ratten

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Alsalem, A., Thaichon, P., Weaven, S. (2020). Organ Donation for Social Change: A Systematic Review. In: Ratten, V. (eds) Entrepreneurship and Organizational Change. Contributions to Management Science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-35415-2_6

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-35415-2_6

Published : 07 January 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-35414-5

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-35415-2

eBook Packages : Business and Management Business and Management (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Bureaus and Offices

- Contact HRSA

- For Workplaces

- Grants and Research

Research Reports

2019 national survey of organ donation attitudes and practices.

The 2019 National Survey of Organ Donation Attitudes and Practices measured public opinion about organ donation and transplantation. This survey was completed by 10,000 U.S. adults. Key findings include:

- People’s support for organ donation.

- If they have signed up to be an organ donor and where.

- Talking to family members about organ donation and their wish.

- Beliefs about organ donation and transplantation.

- If they want their organs used locally or wherever they are needed most.

- Where they got their information on organ donation in the past year.

View and download the 2019 National Survey report (PDF - 3 MB) .

Supplemental Tables

- Binary Response Tables (XLSX - 459 KB) – Frequency tables with data bars/color coding in the 2019 National Survey report.

- Supplemental Tables (XLSX - 196 KB) – Non-frequency tables in the 2019 National Survey report.

- Full Response Tables (XLSX - 510 KB) – Proportions and confidence intervals for every response option for all 86 key survey questions.

Listen to/watch a webinar recording on key findings of the survey. Slides from the webinar (PDF - 697 KB) are also available.

Note: If you are using assistive technology, you may not be able to fully see all of the information in this PDF file. The Excel file with it has the same information for the National Survey of Organ Donation Attitudes and Practices, 2019: Report of Findings. For help, please email [email protected] or call 301-443-3300.

2012 National Survey of Organ Donation Attitudes and Behaviors

This report details the findings of the 2012 survey of the American public’s attitudes and behaviors about organ donation.

View and download the 2012 National Survey of Organ Donation Attitudes and Behaviors (PDF - 1 MB) report.

Worldwide barriers to organ donation

Affiliations.

- 1 Neurocritical Care Unit and Stroke Department, Hospital Copa D'Or, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

- 2 Cerebrovascular Center of the Neurological Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio.

- PMID: 25402335

- DOI: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.3083

Importance: The disparity between patients awaiting organ transplantation and organ availability increases each year. As a consequence, organ trafficking has emerged and developed into a multibillion-dollar-a-year industry.

Objective: To identify and address barriers to organ donation in the United States and globally.

Evidence review: Evidence-based peer-reviewed articles, including prospective and retrospective cohort studies, as well as case series and reports were identified in a PubMed search of organ donation, barriers to organ donation, brain death, donation after cardiac death, and organ trafficking. Additional Internet searches were conducted of national and international transplant and organ donation websites and US Department of Health of Health and Human Services websites. Citation publication dates ranged from August 1, 1968, through June 28, 2014.

Findings: The lack of standardization of brain death and organ donation criteria worldwide contributes to a loss of potential donors. Major barriers to donation include variable clinical and legal definitions of brain death; inconsistent legal upholding of brain death criteria; racial, ethnic, and religious perspectives on organ donation; and physician discomfort and community misunderstanding of the process of donation after cardiac death. Limited international legislation and oversight of organ donation and transplant has contributed to the dilemma of organ trafficking.

Conclusions and relevance: An urgent need exists for a global standard on the definition of brain death and donation after death by cardiac criteria to better regulate organ donation and maximize transplantation rates. Unified standards may have a positive effect on limiting organ trafficking.

Publication types

- Attitude to Health*

- Global Health

- Tissue and Organ Procurement* / methods

- Tissue and Organ Procurement* / standards

- United States

Organ Donation: Importance Information Research Paper

Organ transplant is a form of surgery in which an injured, diseased, or damaged body organ is removed from a patient and replaced with a healthy organ, which has been donated (Elgert 4). This concept emerged in the 19 th century and has been practiced for a long time now (about 50 years now). Majorly, several vital body organs can be transplanted.

The most common body organs being transplanted today include the heart, liver, kidney, and lungs (Elgert 4). Across the globe, more than 1 million organ transplants happen every year with the US performing more than 20,000 cases. Today, the success rates of organ transplants have been on the increase although donors are reducing drastically.

Just like any other surgery, organ transplantation has some risks and complications. Some of the most common complications include infections, excessive bleeding, and damages (Elgert 32). For instance, in kidney transplantation, the urethra may be damaged when the doctor is carrying out the surgery (NHS Organ Donor).

Because of such complications, the patient may not survival for long and hence the process is deemed not successful. The ability to reduce complications and ensure that organ transplantation happens in a success manner may increase the chances of a patient surviving; this is what is known as successful surgery.

Success rates refer to the percentage of all organ transplantation surgeries that produce favorable outcomes (Elgert 35). The success rates of organ transplant surgery have increased and improved in a big way.

However, despite of these remarkable improvements, there is also a growing demand for organs and tissues as the supply has been going down every day. Because of the growing shortage of body organ, many needy patients do not have adequate supply and as a result, there are many situations where patients are dying before they get willing donors.

Because of the improved and advanced technology, the practice of organ transplant is becoming more popular and acceptable in the society. Currently, the advancement in technology has contributed to improved ways of preserving organs and better surgical methods in the health care (Elgert 67). Notably, better and improved health care has contributed to increase in success rates of organ and tissue transplant across the world.

According to research, the success rates of organ transplant have improved in a big way. In fact, Sir Madgi Yacoub a senior researcher at a donations center describes the practice of organ transfer as “one of the greatest success stories of the latter half of the 20 th century (NHS Organ Donor).

This has greatly been attributed to the advanced technology and quality patience care. The UK organ transplants statistics show that, transplants surgery have been increasing every year.

To demonstrate this facts, the newly released report on organ transplants reveal that at least 94 per cent of kidney donors are still leaving very healthy, more than 88 per cent of transplanted kidneys from people who are dead are running and functioning healthy, 86 per cent of liver transfers are still performing well, and 84 per cent of all heart transfers are still doing well too (NHS Organ Donor).

According to this report, many factors have contributed to increase in successful rates of organ transplants. One of the factors is the improved patient management, which is getting better every year (NHS Organ Donor).

Recently, the center of Scientific Registry of Transplant (SRTR) provided data concerning the success rates of patients who have received organ transplant in the US (New York Organ Donor Network, Inc).

According to (SRTR) research center, the survival of patients who have already received organ transplant is deemed as the best measure of assessing the success rates of transplant. Indeed, by focusing closely on the data provided, it is evident that the success rates have increased over the years as portrayed by the “history and success rate of organ transplantation” (Hakim and Vassilios 7).

The history of organ transfer will further prove how the success rates of organ transplantations have improved in the recent years. In the year 1999, the number of individuals who required organ transplant stood at 55, 000 people (Hakim and Vassilios 47). However, today the demand for this service has increased over the years since more people have developed trust with this practice after witnessing high level of success rates.

Because of the improved rates, many patients have been demanding for this service. According to experts, “improved survival rates and the expectation that organ replacement will enhance quality of life encouraged more doctors and their patients with organ failure to opt for transplantation” (Hakim and Vassilios 241).

According to history, the practice of organ transplant is a concept that started a few decades ago. The first successful organ transplant took place in the 1954 where a patient received a kidney transplant in the US (Hakim and Vassilios 97).

In 1967, the first case of heart transplant took place in South Africa and the heart function was effective for 18 days (Patel and Rushefsky 34). In the year 1981, a successful heart transfer showed some improvement where a patient who received a heart transfer survived for 5 years.

During 1990s, the practice of transplantation surgery became more popular and more than 2,500 heart transplants were performed in the US alone (Patel and Rushefsky 65). Along with cases of heart transfer, increased cases of other organ transplants were reported around the globe. In the year 1997, the record of success in organ transplantation went high.

For kidney transplants, a statics record of 95 per cent survival rates was recorded in a period of one year (Patel and Rushefsky, 2002). To demonstrate the increase in the survival rates of organs transfer, a study by United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) portrayed an impressive improvement from 7 per cent to 12 per cent successful rates of lung, heart, and liver transplants between the year 1992 and 1994 (Patel and Rushefsky 22).

This and many similar investigations have proved that the success rates of organ transplant vary from one transplant centre to another (Patel and Rushefsky, 42). Notably, centers that have had low success rates are those centers, which have been reported to carry out a small number of organ transplants (Patel and Rushefsky, 55).

On the other hand, transfer centers that carry out large numbers of organ transplants have been reported to produce statistical numbers showing high success rates. Over the years, this level of successful rates have increased for both low-volume and high volume transplant centers. For both centers, an increase success rate of 50 per cent has been recorded in the recent years (Patel and Rushefsky, 79).

Towards the start of this decade, major developments have taken place in the health care institutions. As such, success rates have also improved and many patients are now being refereed for these vital services (Elgert 4).

Because of the ever-growing demand, many countries around the world are also creating new organ transplant centers. However, with the increased successful rates of organ transplants, there has been reduced supply of organs (Egendorf 14). It has been reported that, the demand for donor organs has also increased, as people are not willing to donate their organs.

Among the many factors that have contributed to improved success rates of transplants is the issue of innovations. The positive technological innovation is an improvement, which has led to more patients surviving. This is precisely because with innovations, modern and better preservation methods have also developed.

As such, donated organs are preserved well therefore reducing chances of organ failure once implanted into the recipient. Another factor that has contributed to improved success rates is the improvements in surgical technique (New York Organ Donor Network, Inc). Progress in this area has also contributed to improvement in success rates of organ transfer as the operation surgeons are carryout an excellent job.

On the other hand, a continuous decline in the supply of donors has been observed for the last five years. Doctors have reported that, the reduced supply of organs from donors can have “resulted in a widening gap between the number of organs available for transplant, and the number of patients who are waiting for donor organs” (New York Organ Donor Network, Inc).

In this report, it has been noted that, the number of living donors increased a great deal between the year 1999 and 2004, but the numbers started decreasing drastically by the end of 2004 (Egendorf 51).

Despite the challenges and the issue of organ shortage, we can see light at the end of the tunnel. In providing a solution, a study has revealed that “the market place for immunosuppressive” is most likely to grow and expand for next 5 years from now (New York Organ Donor Network, Inc). This market is likely to expand because of the fact that, new transplant centers are being developed considering that survival rates have gone up significantly.

In summary, it is evidently clear that the success rates of organ transplantation have increased considerably over the years. Towards the start of this decade, major developments have taken place in the health care sector.

Among the many changes that have taken place, advanced technology has been the most fundamental change, which has contributed to increased chances of survival among the patients receiving organ transplant and therefore bringing positive outcomes.

Several governmental and non-governmental organizations have done extensive research with an aim of investigating the success rates of organ transplantation in the recent days.

According to the findings from different organizations like United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), it has been revealed that there is a general improvement in the success rates especially from the year 2000 onwards.

On the other hand, with the increase in the success rates, there is a growing demand for organ donors because there is a shortage in supply of organs in the market (Egendorf 75). However, despite this shortage, the market is anticipated to improve in the future days, as people are developing confidence due to increased survival rates.

Works Cited

Elgert, Klaus. Immunology: Understanding the Immune System . New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons, 2009. Print.

Egendorf, Laura. Organ Donation . San Diego: Greenhaven Press, 2009. Print.

Hakim, Nadey and Vassilios Papalois. History of Organ and Cell Transplantation . London: Imperial College Press, 2003. Print.

New York Organ Donor Network, Inc. Donation . 2011. Web.

NHS Organ Donor. Success rates . 2011. Web.

Patel, Kant and Mark Rushefsky. Healthcare Policy in an Age of New Technologies . Carlifornia: M.E. Sharpe, 2002. Print.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, January 5). Organ Donation: Importance Information. https://ivypanda.com/essays/organ-donation/

"Organ Donation: Importance Information." IvyPanda , 5 Jan. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/organ-donation/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'Organ Donation: Importance Information'. 5 January.

IvyPanda . 2024. "Organ Donation: Importance Information." January 5, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/organ-donation/.

1. IvyPanda . "Organ Donation: Importance Information." January 5, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/organ-donation/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Organ Donation: Importance Information." January 5, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/organ-donation/.

- Organ Donation and Transplantation Medicine

- Organ Transplantation and Donation

- Organ Donation: Postmortem Transplantation

- The COVID-19 Impact on Organ Donation

- The Ethics of Organ Donation in Modern World

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Organ Transplantation

- Organ Donation: Donor Prevalence in Saudi Arabia

- Researching of Xenograft and Organ Donation

- Importance of Organ Donation

- Pros and Cons of Paying for Organ Donation: Arguments for Prohibition

- Al-Zahrawi's Life and Contributions

- Consumer Trend Analysis: Plastic Surgery

- Materials for Artificial Hip Joints’

- “Postoperative Recovery Advantages in Patients Undergoing Thyroid and Parathyroid Surgery Under Regional Anesthesia.” by Suri

- Women and Breast Augmentation

- Português Br

- Journalist Pass

Organ donation: Don’t let these myths confuse you

Mayo Clinic Staff

Share this: