Course Assessment

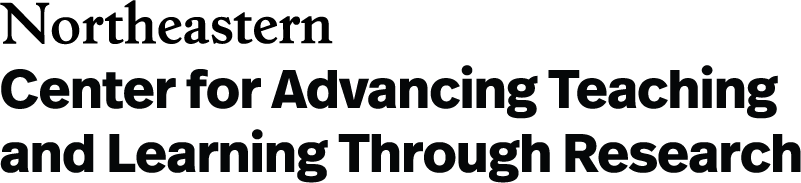

Course-level assessment is a process of systematically examining and refining the fit between the course activities and what students should know at the end of the course.

Conducting a course-level assessment involves considering whether all aspects of the course align with each other and whether they guide students to achieve the desired learning outcomes.

“Assessment” refers to a variety of processes for gathering, analyzing, and using information about student learning to support instructional decision-making, with the goal of improving student learning. Most instructors already engage in assessment processes all the time, ranging from informal (“hmm, there are many confused faces right now- I should stop for questions”) to formal (“nearly half the class got this quiz question wrong- I should revisit this concept”).

When approached in a formalized way, course-level assessment is a process of systematically examining and refining the fit between the course activities and what students should know at the end of the course. Conducting a course-level assessment involves considering whether all aspects of the course align with each other and whether they guide students to achieve the desired learning outcomes . Course-level assessment can be a practical process embedded within course design and teaching, that provides substantial benefits to instructors and students.

Over time, as the process is followed iteratively over several semesters, it can help instructors find a variety of pathways to designing more equitable courses in which more learners develop greater expertise in the skills and knowledge of greatest importance to the discipline or topic of the course.

Differentiating Grading from Assessment

“Assessment” is sometimes used colloquially to mean “grading,” but there are distinctions between the two. Grading is a process of evaluating individual student learning for the purposes of characterizing that student’s level of success at a particular task (or the entire course). The grade of an assignment may provide feedback to students on which concepts or skills they have mastered, which can guide them to revise their study approach, but may not be used by the instructor to decide how subsequent class sessions will be spent. Similarly, a student’s grade in a course might convey to other instructors in the curriculum or prospective employers the level of mastery that the student has demonstrated during that semester, but need not suggest changes to the design of the course as a whole for future iterations.

In contrast to grading, assessment practices focus on determining how many students achieved which learning course outcomes, and to what level of mastery, for the purpose of helping the instructor revise subsequent lessons or the course as a whole for subsequent terms. Since final course grades may include participation points, and aggregate student mastery of all course learning objectives into a single measure, they rarely give clarity on what elements of the course have been most or least successful in achieving the instructor’s goals. Differentiating assessment from grading allows instructors to plot a clear course forward toward making the changes that will have the greatest impact in the areas they define as being most important, based on the results of the assessment.

Course learning outcomes are measurable statements that describe what students should be able to do by the end of a course . Let’s parse this statement into its three component parts: student-centered, measurable, and course-level.

Student-Centered

First, learning outcomes should focus on what students will be able to do, not what the course will do. For example:

- “Introduces the fundamental ideas of computing and the principles of programming” says what a course is intended to accomplish. This is perfectly appropriate for a course description but is not a learning outcome.

- A related student learning outcome might read, “ Explain the fundamental ideas of computing and identify the principles of programming.”

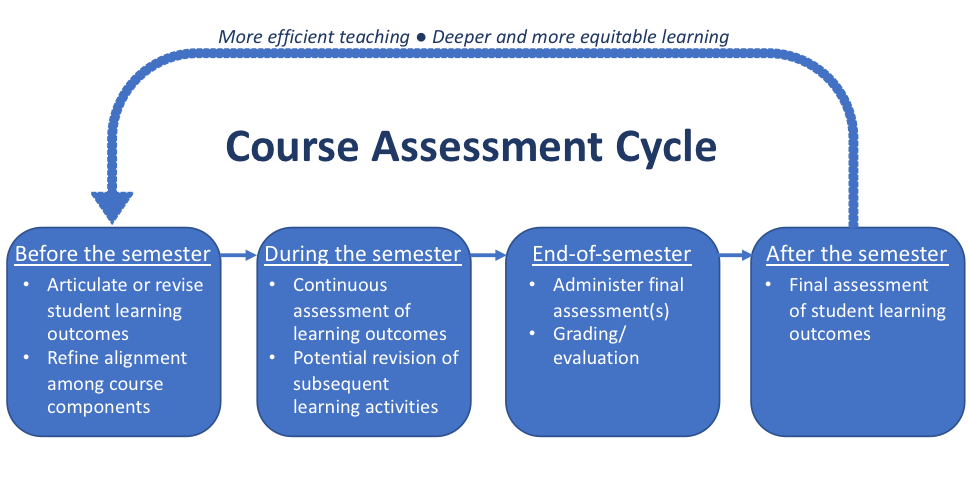

Second, learning outcomes are measurable , which means that you can observe the student performing the skill or task and determine the degree to which they have done so. This does not need to be measured in quantitative terms—student learning can be observed in the characteristics of presentations, essays, projects, and many other student products created in a course (discussed more in the section on rubrics below).

To be measurable, learning outcomes should not include words like understand , learn , and appreciate , because these qualities occur within the student’s mind and are not observable. Rather, ask yourself, “What would a student be doing if they understand, have learned, or appreciate?” For example:

- “Learners should understand US political ideologies regarding social and environmental issues,” is not observable.

- “Learners should be able to compare and contrast U.S. political ideologies regarding social and environmental issues,” is observable.

Course-Level

Finally, learning outcomes for course-level assessment focus on the knowledge and skills that learners will take away from a course as a whole. Though the final project, essay, or other assessment that will be used to measure student learning may match the outcome well, the learning outcome should articulate the overarching takeaway from the course, rather than describing the assignment. For example:

- “Identify learning principles and theories in real-world situations” is a learning outcome that describes skills learners will use beyond the course.

- “Develop a case study in which you document a learner in a real-world setting” describes a course assignment aligned with that outcome but is not a learning outcome itself.

Identify and Prioritize Your Higher-Order End Goals

Course-level learning outcomes articulate the big-picture takeaways of the course, providing context and purpose for day-to-day learning. To keep the workload of course assessment manageable, focus on no more than 5-10 learning outcomes per course (McCourt, 2007). This limit is helpful because each of these course-level learning objectives will be carefully assessed at the end of the term and used to guide iterative revision of the course in future semesters.

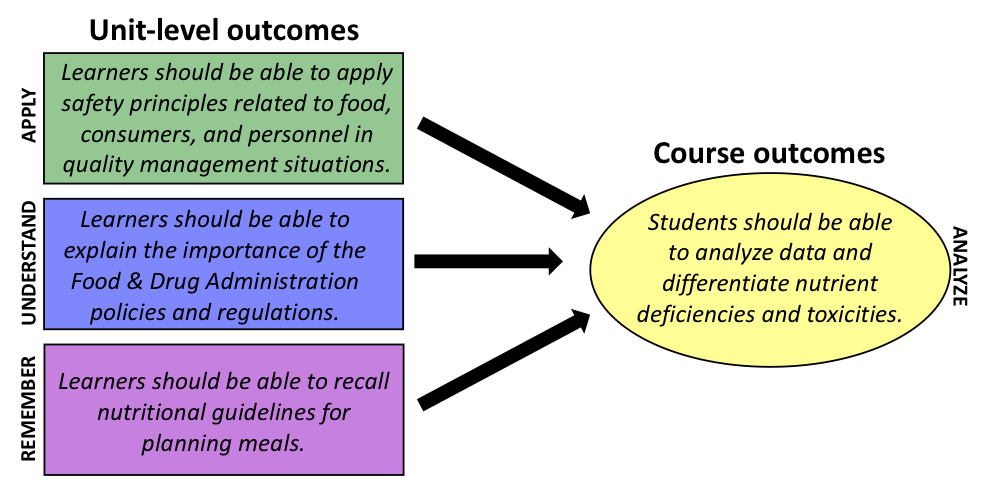

This is not meant to suggest that students will only learn 5-10 skills or concepts during the term. Multiple shorter-term and lower-level learning objectives are very helpful to guide student learning at the unit, week, or even class session scale (Felder & Brent, 2016). These shorter-term objectives build toward or serve as components of the course-level objectives.

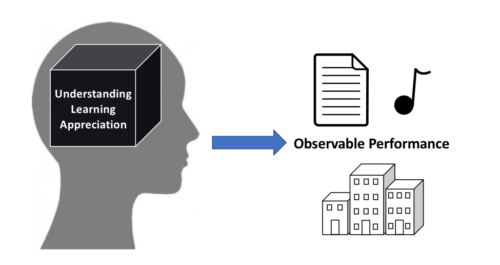

Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001) is a helpful tool for deciding which of your objectives are course-level, which may be unit-to class-level objectives, and how they fit together. This taxonomy organizes action verbs by complexity of thinking, resulting in the following categories:

Download a list of sample learning outcomes from a variety of disciplines .

Typically, objectives at the higher end of the spectrum (“analyzing,” “evaluating,” or “creating”) are ideal course-level learning outcomes, while those at the lower end of the spectrum (“remembering,” “understanding,” or “applying”) are component parts and day, week, or unit-level outcomes. Lower-level outcomes that do not contribute substantially to students’ ability to achieve the higher-level objectives may fit better in a different course in the curriculum.

Consider Involving Your Learners

Depending on the course and the flexibility of the course structure and/or progression, some educators spend the first day of the course working with learners to craft or edit learning outcomes together. This practice of giving learners an informed voice may lead to increased motivation and ownership of learning.

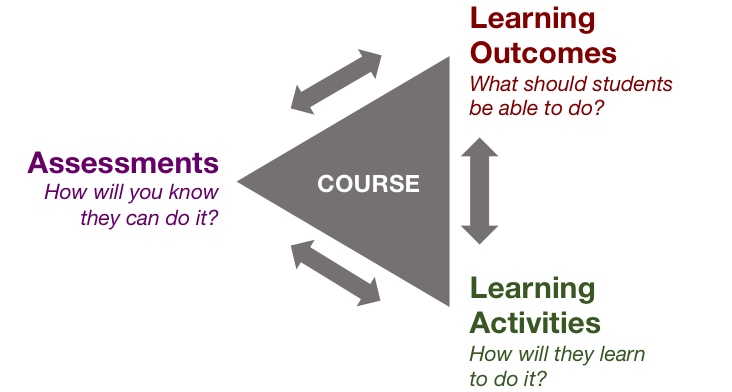

Alignment, where all components work together to bolster specific student learning outcomes, occurs at multiple levels. At the course level, assignments or activities within the course are aligned with the daily or unit-level learning outcomes, which in turn are aligned with the course-level objectives. At the next level, the learning outcomes of each course in a curriculum contribute directly and strategically to programmatic learning outcomes.

Alignment Within the Course

Since learning outcomes are statements about key learning takeaways, they can be used to focus the assignments, activities, and content of the course (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). Biggs & Tang (2011) note that, “In a constructively aligned system, all components… support each other, so the learner is enveloped within a supportive learning system.”

For example, for the learning outcome, “learners should be able to collaborate effectively on a team to create a marketing campaign for a product,” the course should: (1) intentionally teach learners effective ways to collaborate on a team and how to create a marketing campaign; (2) include activities that allow learners to practice and progress in their skillsets for collaboration and creation of marketing campaigns; and (3) have assessments that provide feedback to the learners on the extent that they are meeting these learning outcomes.

Alignment With Program

When developing your course learning outcomes, consider how the course contributes to your program’s mission/goals (especially if such decisions have not already been made at the programmatic level). If course learning outcomes are set at the programmatic level, familiarize yourself with possible program sequences to understand the knowledge and skills learners are bringing into your course and the level and type of mastery they may need for future courses and experiences. Explicitly sharing your understanding of this alignment with learners may help motivate them and provide more context, significance, and/or impact for their learning (Cuevas, Matveevm, & Miller, 2010).

If relevant, you will also want to ensure that a course with NUpath attributes addresses the associated outcomes . Similarly, for undergraduate or graduate courses that meet requirements set by external evaluators specific to the discipline or field, reviewing and assessing these outcomes is often a requirement for continuing accreditation.

See our program-level assessment guide for more information.

Transparency

Sharing course learning outcomes with learners makes the benchmarks for learning explicit and helps learners make connections across different elements within the course (Cuevas & Mativeev, 2010). Consider including course learning outcomes in your syllabus , so learners know what is expected of them by the end of a course and can refer to the outcomes as the term progresses. When educators refer to learning outcomes during the course before introducing new concepts or assignments, learners receive the message that the outcomes are important and are more likely to see the connections between the outcomes and course activities.

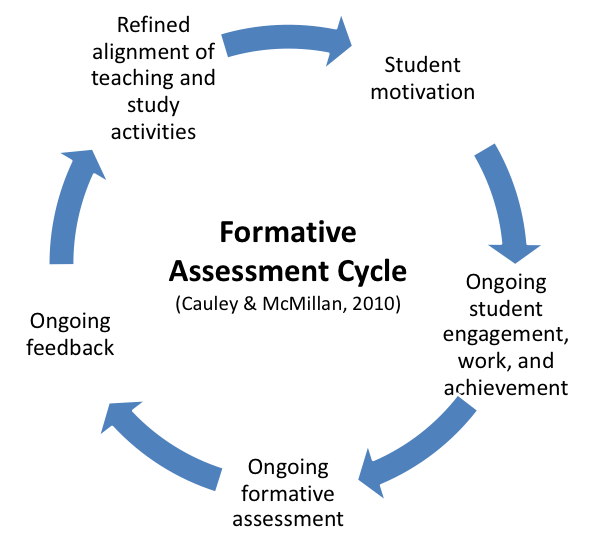

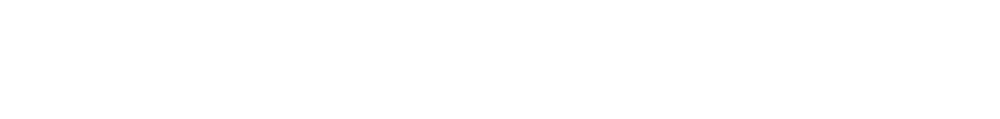

Formative Assessment

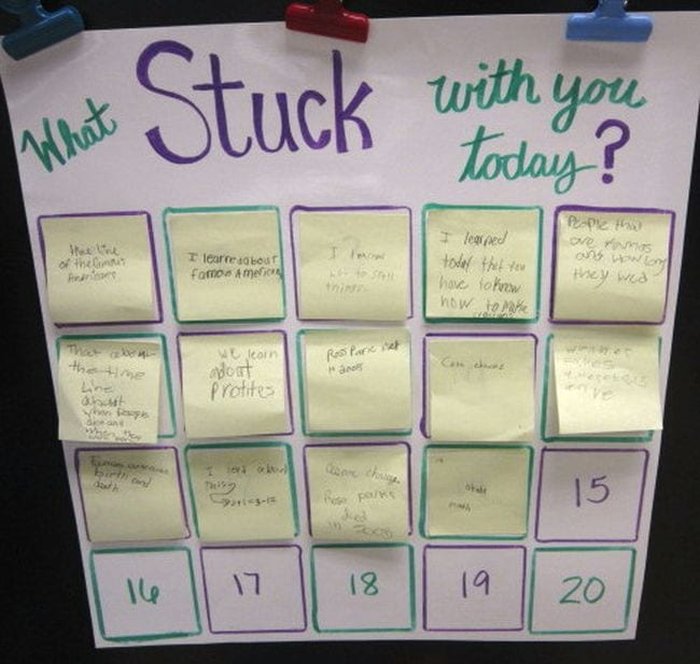

Formative assessment practices are brief, often low-stakes (minimal grade value) assignments administered during the semester to give the instructor insight into student progress toward one or more course-level learning objectives (or the day-to unit-level objectives that stair-step toward the course objectives). Common formative assessment techniques include classroom discussions , just-in-time quizzes or polls , concept maps , and informal writing techniques like minute papers or “muddiest points,” among many others (Angelo & Cross, 1993).

Refining Alignment During the Semester

While it requires a bit of flexibility built into the syllabus, student-centered courses often use the results of formative assessments in real time to revise upcoming learning activities. If students are struggling with a particular outcome, extra time might be devoted to related practice. Alternatively, if students demonstrate accomplishment of a particular outcome early in the related unit, the instructor might choose to skip activities planned to teach that outcome and jump ahead to activities related to an outcome that builds upon the first one.

Supporting Student Motivation and Engagement

Formative assessment and subsequent refinements to alignment that support student learning can be transformative for student motivation and engagement in the course, with the greatest benefits likely for novices and students worried about their ability to successfully accomplish the course outcomes, such as those impacted by stereotype threat (Steele, 2010). Take the example below, in which an instructor who sees that students are struggling decides to dedicate more time and learning activities to that outcome. If that instructor were to instead move on to instruction and activities that built upon the prior learning objective, students who did not reach the prior objective would become increasingly lost, likely recognize that their efforts at learning the new content or skill were not helping them succeed, and potentially disengage from the course as a whole.

Artifacts for Summative Assessment

To determine the degree to which students have accomplished the course learning outcomes, instructors often assign some form of project , essay, presentation, portfolio, renewable assignment , or other cumulative final. The final product of these activities could serve as the “artifact” that is assessed. In this context, alignment is particularly critical—if this assignment does not adequately guide students to demonstrate their achievement of the learning outcomes, the instructor will not have concrete information to guide course design for future semesters. To keep assessment manageable, aim to design a single final assignment that create the space for students to demonstrate their performance on multiple (if not all) course learning outcomes.

Since not all courses are designed with a final assignment that allows students to demonstrate their highest level of achievement of all course learning outcomes, the assessment processes could use the course assignment that represents the highest level of achievement that students had an opportunity to demonstrate during the term. However, some learning objectives that do not come into play during the final may be better categorized as unit-level, rather than course-level, objectives.

Direct vs. Indirect Measures of Student Learning

Some instructors also use surveys, interviews, or other methods that ask learners whether and how they believe they have achieved the learning outcomes. This type of “indirect evidence” can provide valuable information about how learners understand their progress but does not directly measure students’ learning. In fact, novices commonly have difficulty accurately evaluating their own learning (Ambrose et al., 2010). For this reason, indirect evidence of student learning (on its own) is not considered sufficient for summative assessment.

Together, direct and indirect evidence of student learning can help an instructor determine whether to bolster student practice in certain areas or whether to simply focus on increasing transparency about when students are working toward which learning outcome.

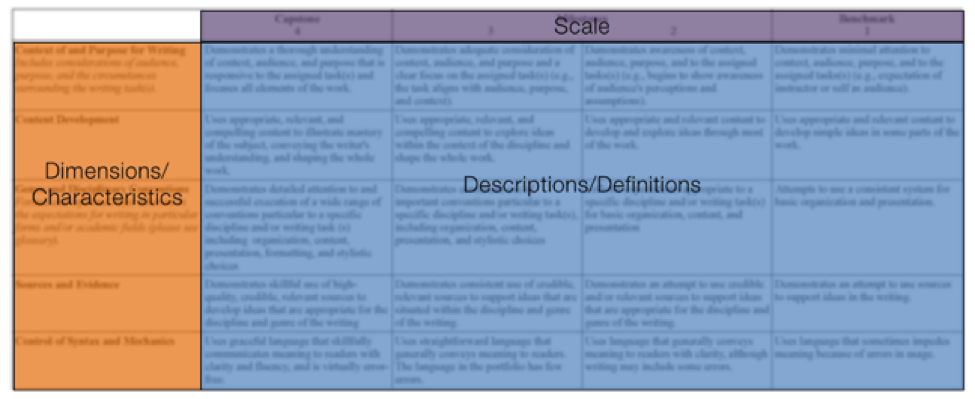

Creating and Assessing Student Work with Analytic Rubrics

One tool for assessing student work is analytic rubrics (shown below) which are matrices of characteristics and descriptions of what it might look like for student products to demonstrate these characteristics at different levels of mastery. Analytic rubrics are commonly recommended for assessment purposes, since they provide more detailed feedback to guide course design in more meaningful ways than holistic rubrics. Pre-existing analytic rubrics such as the AAC&U VALUE Rubrics can be tailored to fit your course or program, or you can develop an outcome-specific rubric yourself (Moskal, 2000 is a useful reference, or contact CATLR for a one-on-one consultation). The process of refining a rubric often involves multiple iterations of applying the rubric to student work and identifying the ways in which it captures or does not capture the characteristics representing the outcome.

Summative assessment results can inform changes to any of the course components for subsequent terms. If students have underperformed on a particular course learning objective, the instructor might choose to revise the related assignments or provide additional practice opportunities related to that objective, and formative assessments might be revised or implemented to test whether those new learning activities are producing better results. If the final assessment does not provide sufficient information about student performance on a certain outcome, the instructor might revise the assessment guidelines or even implement a different assessment that is more aligned to the outcome. Finally, if an instructor notices during the assessment process that an important outcome has not been articulated, or would be more clearly stated a different way, that instructor might revise the objectives themselves.

For assistance at any stage of the course assessment cycle, contact CATLR for a one-on-one or group consultation.

Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M. C., & Norman, M. K. (2010). How learning works: Seven research-based principles for smart teaching . San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives . New York, NY: Longman.

Bembenutty, H. (2011). Self-regulation of learning in postsecondary education. New Directions for Teaching and Learning , 126 , 3-8. doi: 10.1002/tl.439

Biggs, J., & Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for Quality Learning at University . Maidenhead, England: Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.

Cauley, K. M., & McMillan, J. H. (2010). Formative assessment techniques to support student motivation and achievement. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas , 83 (1), 1-6. doi: 10.1080/00098650903267784

Cuevas, N. M., Matveev, A. G., & Miller, K. O. (2010). Mapping general education outcomes in the major: Intentionality and transparency. Peer Review , 12 (1), 10-15.

Felder, R. M., & Brent, R. (2016). Teaching and learning STEM: A practical guide . San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy: An overview. Theory into practice , 41 (4), 212-218. doi: 10.1207/s15430421tip4104_2

McCourt, Millis, B. J., (2007). Writing and Assessing Course-Level Student Learning Outcomes . Office of Planning and Assessment at the Texas Tech University.

Moskal, B. M. (2000). Scoring rubrics: What, when and how? Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation , 7 (3).

Setting Learning Outcomes . (2012). Center for Teaching Excellence at Cornell University. Retrieved from https://teaching.cornell.edu/teaching-resources/designing-your-course/setting-learning-outcomes .

Steele, C. M. (2010). Whistling Vivaldi: How Stereotypes Affect Us and What We Can Do . New York, NY: WW Norton & Company, Inc.

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by Design (Expanded) . Alexandria, US: Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development (ASCD).

Teaching Commons Conference 2024

Join us for the Teaching Commons Conference 2024 – Cultivating Connection. Friday, May 10.

Course Evaluations and End-term Student Feedback

Main navigation.

At Stanford, student course feedback can provide insight into what is working well and suggest ways to develop your teaching strategies and promote student learning, particularly in relation to the specific learning goals you are working to achieve.

There are many ways to assess the effectiveness of teaching and courses , including feedback from students, input from colleagues, and self-reflection. No single method of evaluation offers a complete view. This page describes the end-term student feedback survey and offers recommendations for managing it.

End-term student feedback

The end-term student feedback survey, often referred to as the “course evaluations”, opens in the last week of instruction each quarter for two weeks:

- Course evaluations are anonymous and run online

- Results are delivered to instructors after final grades are posted

- The minimum course enrollment for evaluations is three students

Two feedback forms

Students provide feedback on their courses using up to two forms:

- The course feedback form gathers feedback on students' experience of the course, covering general questions about learning and course organization, and potentially specific learning goals, course elements, and other instructor-designed questions. At Stanford, this form focuses on the course as a whole and not the performance of individual instructors. Students complete one form for each course, even in a team-teaching situation where there could be several instructors.

- The section feedback form gathers feedback on the TAs or CAs students interact with, usually through sections such as discussions and labs. Even if TAs and CAs do not lead individual sections—for example, they take office hours or assist during labs—they can still receive feedback using this form.

Course evaluation system

The current course evaluation platform is EvaluationKIT, accessible to instructors at evaluationkit.stanford.edu .

End-term course evaluations and EvaluationKIT are managed by Evaluations and Research, part of Learning Technologies and Spaces (LTS) within Student Affairs . You can find comprehensive information about end-term course evaluations on the Evaluations and Research website.

Tailored custom questions

The course and section forms are customizable , allowing you to add specific questions, such as learning goals, course elements (such as textbooks), and even questions of your own, so that you can gather targeted feedback on aspects of your course design.

Although you are not required to customize your questions, it is an excellent way to gather information on any aspect of the course that you want to assess, such as a new teaching technique, an activity, or an approach you want to revise. If you do not customize, your students will still respond to the standard questions.

Managing your end-term feedback

Whether you are new to Stanford or familiar with the course evaluations system, these are the most useful links to managing your evaluations every quarter:

- Key dates : review the key dates for customization, opening and closing of the evaluations, and reports.

- Customization is open for four weeks each quarter, starting in Week 4, so you can add your own questions to the course and section forms.

- Interpreting your reports : Reading and interpreting feedback effectively will help you to assess what is working and identify areas where your course may need to make adjustments.

- The Evaluations and Research website has many resources to help you find, read, and interpret evaluation reports, as well as understand the scope and limitations of teaching evaluations.

Need help understanding or responding to course evaluations?

The Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) has trained and experienced teaching consultants who can help you interpret results and advise on teaching strategies. Contact CTL to request a consultation at any time.

Further sources of evaluation and feedback

There are many other sources of feedback that can help inform your teaching and learning decisions, including:

- Mid-term student feedback is an excellent way to gather actionable insights into a course while the course is still in progress and it is possible to make adjustments, if necessary, before the end of the quarter. Consider a Small Group Feedback Session offered by CTL or an in-class survey .

- Input from colleagues , such as peer observations, particularly when including a review of materials and course goals, and using a consistent review protocol. Peer review can include online materials, modules, and courses using criteria similar to those for in-class instruction.

- Instructor’s self-reflection , including evaluation of course materials, such as syllabi, assignments, exams, papers, and so on.

- Other contributions, such as those to curriculum development, supervision of student research, mentoring of other instructors, creation of instructional materials, and published research on teaching, can be assessed by colleagues and also form part of a general teaching portfolio.

- OU Homepage

- The University of Oklahoma

Course Assessment

Over the past two decades, colleges and universities across the United States have faced increased demands to show evidence that students are meeting appropriate educational goals. Designing and implementing assessments at the course level is quite instrumental in ensuring that students are not just learning the material, but also providing important information to instructors on the extent of the progress students are making in attaining the intended learning outcomes of the course. A formal process of assessing a course can help instructors effectively facilitate student learning by:

- Promoting a clearer and better comprehension of course expectations for their work and how the quality of their work will be evaluated.

- Ensuring clarity regarding teaching goals and what students are expected to learn.

- Cultivating student engagement in their own learning.

- Fostering effective communication and feedback with students.

- Providing increased information about student learning in the classroom, leading to adjustments in pedagogical styles as the course progresses.

Assessment at the course level addresses the following critical questions:

- What do you want students to know and do upon completion of your course?

- And how will you know if they get there?

These questions provide an excellent opportunity for classroom assessment process to directly address concerns about better learning and effective teaching. Below is a simple process of instructors can use to developing a course assessment plan:

Remote/Online Assessment Techniques

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has led to huge challenges regarding the teaching and assessment of student learning process in higher education. As a result of this, the Office of Academic Assessment has developed and put together resources to assist faculty as they continue to develop and/or adopt assessment strategies appropriate for and applicable to the current online/remote teaching and learning. As you continuously refine aspects of your course in the online environment, you may find the following best practices and answers to frequently asked questions relating to online assessment particularly helpful and useful. Please feel free to reach out to the Office of Academic Assessment for consultations to help provide insights regarding practical, classroom or course-level assessments appropriate for online or remote environment.

To Get Started

Given that during the Fall 2020 semester, most tests and examinations were delivered to students digitally, irrespective of course modality, and the same is expected to continue in spring 2021, we strongly encourage all faculty to plan assessments well in advance of scheduled delivery. This will help ensure that online or remote assessment continues to not only be rigorous, but also appropriate and meaningful to the teaching and learning process. Below are useful questions to ask you may ask yourself:

- What do you expect students enrolled in your course to know and do upon completion of the course? How can they demonstrate what they learned through your course?

- If you intend to use open-book for some of the online or remote assessments, do you have examples of questions you can ask students that target conceptual, application, or require them to demonstrate higher-order thinking?

- Can your students demonstrate understanding in a less traditional format such as a presentation, portfolio, or project?

- If you usually use multiple-choice questions, can you reduce the number of lower- questions and replace with items requiring students demonstrate critical thinking and problem-solving skills? Could questions be written so students need to show a practical application of what they've learned?

Helpful Insights to Consider

- Make your instructions and course expectations very clear to students. One way to do this is to embed details of your course assignments expectations in your syllabus. For instance, do you allow your students to use notes or other outside materials? Can they collaborate? Are the assignments or exams timed? Communication is particularly important in an online/remote environment.

- Besides multiple-choice type assessments/exams, many alternative forms of assessments may require the use of rubrics to (1) help you determine the quality of student work, (2) allow your students see what you're looking for and, (3) make grading consistent and fair.

- Whenever possible, give your students an opportunity to engage in your desired forms of assessments prior to the most important and final exams, so this isn't the first time they're being asked to engage in a new assessment activity. Even if these practice opportunities are formative (i.e., ungraded), giving them the opportunity to practice and get feedback (from you, your TAs, or their peers) can help them be successful, particularly if prior assessments/assignments in your course were in different formats.

- There’s no doubt that students will be navigating unusual new schedules and conflicting priorities as everyone faces the ongoing COVID-19 challenges. Whenever possible, have the assessments/assignments available for them for multiple days as this will give them flexibility.

Best Practices/Options in Remote/Online Assessment

The tumult and uncertainty of the COVID-19 pandemic has greatly impacted the teaching and learning process across institutions of higher education. This is particularly evident in assessment of student learning process, which continues to be challenging, especially in courses that were designed to be taught fully in-person or using the blended format. There are various practical and authentic assessment strategies and tools that can help faculty create or fine-tune assessment to better determine the degree to which students are learning in your class. On this page, we chare several assessment options you may consider applying to your class in addition to using Quiz tools in Canvas.

Assessing Engagement and Interaction

Developing strategies for promoting student engagement online during the ongoing pandemic is difficult. However, there are ways to continue deeper learning and engagement despite these challenges such as maintaining constant communication, listening to and (where possible) accommodating student needs, creating a welcoming atmosphere, building strong relationships with students and, offering both synchronous and asynchronous learning opportunities as a means to ensuring equity.

Peer Assessment

Peer assessment (or “peer review”) is mostly used as a technique for students to assess their fellow students’ work. This typically involves students evaluating and providing feedback to their peers using a rubric or a set of assessment criteria. A well-designed peer assessment process can potentially lead to increase in student motivation and engagement, and help students in development of self-awareness, reflecting on the feedback and enhancing the quality of their own work.

- Creating Peer Assessments in Canvas

Repeated Low-Stakes Assessments

The remote teaching and learning process can be very beneficial if students are engaged and active. One of the strategies to accomplish this is to use brief, more regular assessments such as collaborative projects, weekly writing assignments, short problem sets or quizzes as they provide students a much better and firm foundational knowledge and practice with the planned course materials particularly at this time when high stakes assessments/examinations are not optimal. If you are considering to use low stakes assessments, ensure that objectives of the assessments/assignments are guided by your course student learning outcomes.

- How to use quizzes in Canvas

- Canvas quiz options to randomize questions

- Classroom Assessment Techniques offer a variety of simple but very effective and practical strategies for low-stakes formative assessments.

Student Research/Term Papers

Whether required for individual students or required as a group, research projects/term papers of a variety of lengths and complexity work well in a remote learning environment. Given that students develop research papers/projects throughout the semester, requiring them to submit portions of the project (e.g., the introduction and thesis, the literature review) at different times can be quite beneficial in ensuring quality of the project. In addition, grading each portion of the project separately using a rubric and providing feedback to students not only helps them refine aspects of the project, but also minimizes the possibility that students will be able to plagiarize work.

Course Assessment Tools in Canvas

In addition to the above recommendations, please take a look at the assessment resources available in Canvas as they may be very helpful as you develop or refine assessment plan for your course.

- Learning Outcomes : It is crucial to ensure that student learning outcomes (SLOs) in your course are directly aligned with assessments – this makes the design of the course more helpful and meaningful to students.

- Assignments : Assignments provide students excellent opportunities to demonstrate knowledge and skills/abilities learned in a course.

- Gradebook : understanding the Canvas Gradebook can be very helpful as you develop assessment plan for your course.

- Rubrics : using a well-designed rubric(s) can help you communicate clear expectations regarding assignments/projects in your course, evaluate the quality of student work/projects and manage your ability to provide useful feedback to students.

Back to top

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- OU Job Search

- Legal Notices

- Resources and Offices

- OU Report It!

Assessing Course Outcomes

Learning Objectives

At the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Describe why assessment is used for teaching & learning.

- Explain the difference between assessing traditional and open course materials.

Assessment is an integral part of the education process, a method used as a barometer for what changes may be necessary to improve teaching and learning. Assessment is not always a simple process, so it can help to get some support understanding key concepts.

Assessment in the Classroom

Assessment can occur at any time during or after a course. It is recommended that instructors assess their course regularly, but especially when incorporating new techniques or course materials for the first time. The National Research Council describes the assessment process as a constantly evolving enterprise:

“What is important is that assessment is an ongoing activity, one that relies on multiple strategies and sources for collecting information that bears on the quality of student work and that then can be used to help both the students and the teacher think more pointedly about how the quality might be improved.” [1]

One popular method of assessing a course is to investigate whether the learning outcomes you selected for the course have been met.

Learning Outcomes

Elhabashy defines Student Learning Outcomes (SLOs) as

“the specific observable or measurable results that are expected subsequent to a learning experience. These outcomes may involve knowledge (cognitive), skills (behavioral), or attitudes (affective) that provide evidence that learning has occurred as a result of a specified course, program activity, or process.” [2]

These learning outcomes are used as benchmarks for assessing student learning and, by proxy, your own teaching. Perhaps the most important type of SLOs are Course Learning Outcomes (CLOs). CLOs are the final outcomes that an instructor expects their class to have gained once they leave a course. [3] These should be measurable items, outcomes for which you can create effective assessments.

Anytime you adjust your syllabus, course schedule, or learning materials, it can be helpful to consult your CLOs to ensure that the new structure you are making for your course is able to accommodate the needs of learners and facilitate the development of your learning outcomes.

CLO Example from Library 160: Information Literacy

After completing this course, students will:

- recognize how information creation, dissemination, and the research process can impact what is available on a given topic;

- recognize that information has value and identify how the information you produce is used online;

- appropriately relate information needs to search strategies, tools, and types of information sources, including recognizing and interpreting different types of citations;

- appropriately use the web for research, including critical evaluation of information;

- adhere to academic integrity policies, including those on plagiarism and copyright.

Course learning outcomes can be an invaluable part of the course transformation process for departments hoping to flip courses to open. As Tidewater Community College explained the process for their Z-degree pilot, in which a selection of courses taught at the university were transformed to use OER and other no-cost course materials:

“The faculty team began by stripping each of the 21 courses down to the course learning outcomes and rebuilding them, matching OER to each outcome… Courses were designed consistent with college’s academic and instructional design requirements, and were subjected to a strict copyright review.” [4]

Now that you have an overview of the types of goals you can set for your course, let’s move on to the processes available for assessing whether your students (and, by extension, your teaching) have met them.

Types of Assessment

The point of assessment is to ensure that learning objectives are being met and that your teaching is helping students develop the skills they ought to be achieving throughout your course. The assessment techniques you implement will depend on your preference and the standards in your field, but to help you get started, we’ve listed a few standard assessment types below:

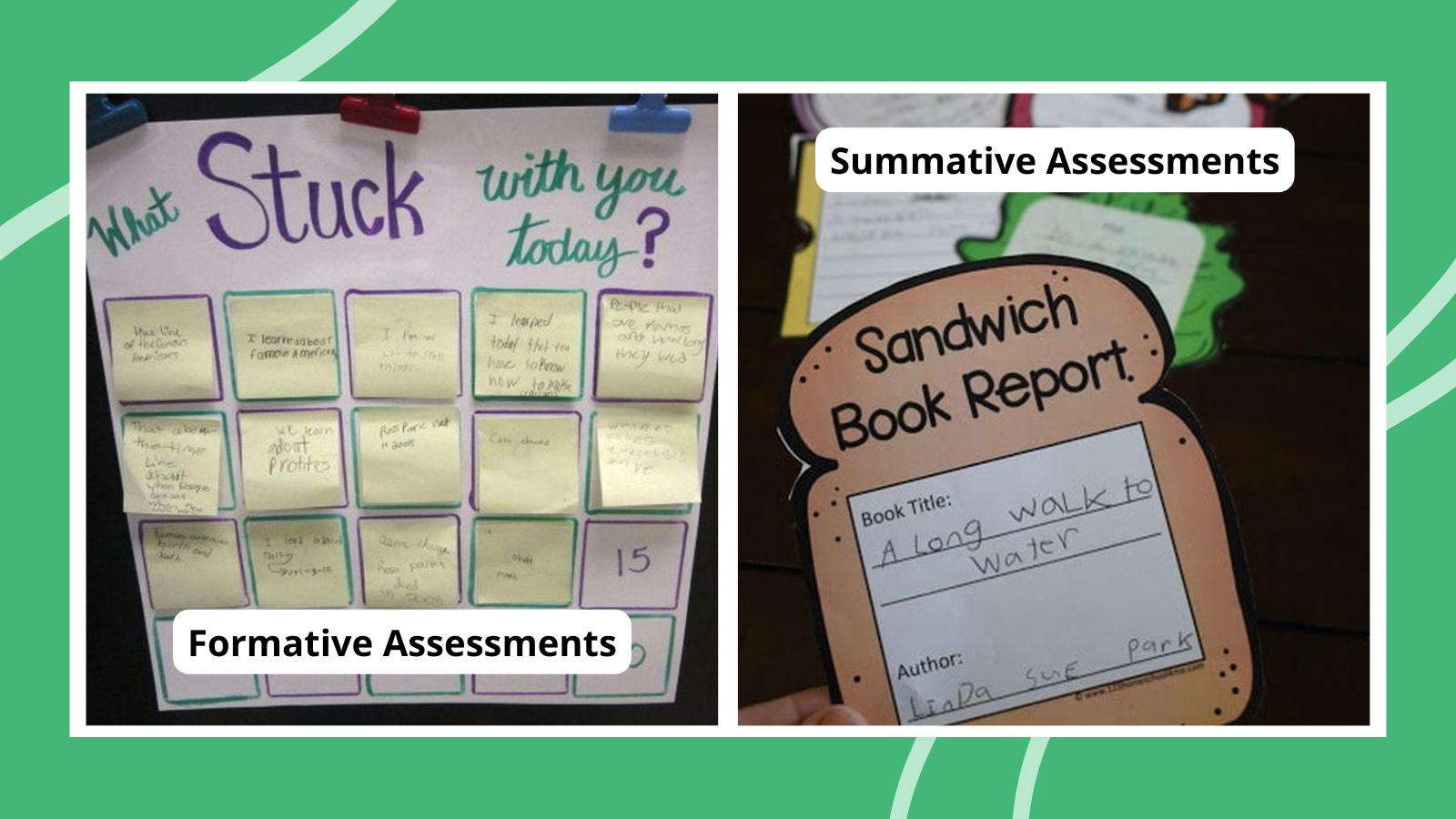

- Formative Assessment : An ongoing process with a wide variety of formats, formative assessment can include quizzes, papers, projects, and any other formal or informal tests provided to gauge your students’ understanding of course content.

- Summative Assessment : The final assessment of student learning after a course has completed, summative assessment can include final papers, projects, or exams. Summative assessment should be used to assess both standard teaching procedures and the effectiveness of any changes made following the formative assessments provided throughout your course.

- Student Self-Assessment : Methods for allowing your students to rate their own confidence in their work and their understanding of course content; examples include writing discussion board posts, drafting exam questions, and filling out confidence rating scales on exams. [5]

- Student Peer-Assessment : The process by which students evaluate the work of their peers within a course, peer assessment is often used as a learning tool to help students reconsider their own understanding of course content as they evaluate the work of their peers. [6]

- Student Assessment of Teaching (SATs) : The manner in which students report on the effectiveness of an instructor’s teaching on their learning, often given at the end of a course but sometimes handled as an ongoing process. The most ubiquitous SATs are student surveys given at the end of a course.

For additional approaches to classroom assessment, the Iowa State University Center for Excellence in Learning & Teaching (CELT) has compiled a website listing quick assessment strategies .

After reviewing these more traditional assessment types, you might wonder how the assessment for a course using OER differs.

Assessment for OER

Assessment for courses utilizing OER does not have to be any different than for courses utilizing traditional materials. Nonetheless, some individuals have developed assessment techniques for the open classroom in particular. One of these is the RISE Framework.

The RISE Framework (Resource Inspection, Selection, and Enhancement) utilizes a 2 x 2 matrix of High Grade/Low Grade and High Use/Low Use to determine how much the use of OER has affected a student’s learning outcomes. [7] The RISE Framework is used to determine how well a student performed in a course and to contrast that outcome with how much they used their provided course materials. This method can help delineate between students who excel in a subject by default and those who have done well in a course thanks to the use of the provided course content. A package in R has been developed for running a RISE analysis quickly and easily. The RISE package for R is openly available in Zenodo.

In the end, what assessment techniques you employ in your course will be determined by a variety of factors, some of which will be out of your control. Nonetheless, it’s important to understand why you’re assessing your course and the impact that assessment can have, particularly for courses changing their materials.

For more information about assessment in the classroom, visit the ISU Center for Excellence in Learning & Teaching’s Assessment & Evaluation website or talk to an instructional designer about your course. In the next chapter, we will transition to talk about how you can get involved in the development of OER.

- National Research Council. Classroom Assessment and the National Science Education Standards . Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2001. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17226/9847. ↵

- Elhabashy, Sameh. Formulate Consequential Student Learning Outcome s. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2017. ↵

- Elhabashy, Sameh. Formulate Consequential Student Learning Outcome s. ↵

- Wiley, David, et al. "The Tidewater Z-Degree and the INTRO Model for Sustaining OER Adoption." Education Policy Analysis Archives 23, no. 41 (2016). DOI: https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.24.1828 ↵

- Sorenson-Unruh, Clarissa. "Ungrading: The First Exam." Reflective Teaching Evolution . May 1, 2019. https://clarissasorensenunruh.com/2019/05/01/ungrading-the-first-exam-part-3/ ↵

- Stanford Teaching Commons. "Peer Assessment." Accessed July 1, 2019. https://teachingcommons.stanford.edu/resources/teaching/evaluating-students/assessing-student-learning/peer-assessment ↵

- Bodily, Robert, Nyland, Rob, and Wiley, David. "The RISE Framework: Using Learning Analytics to Automatically Identify Open Educational Resources for Continuous Improvement." International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 18, no. 2 (2017). DOI: https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i2.2952 ↵

The outcomes that an instructor expects their students to display at the end of a learning experience (an activity, process, or course). (Source: Elhabashy, 2017).

The final outcomes that an instructor expects their students to gain by the time the students complete a course.

The OER Starter Kit Copyright © 2019 by Abbey K. Elder is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Our websites may use cookies to personalize and enhance your experience. By continuing without changing your cookie settings, you agree to this collection. For more information, please see our University Websites Privacy Notice .

Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning

- Teaching and Learning Assessment Overview

Assessment methods are designed to measure selected learning outcomes to see whether or not the objectives have been met for the course. Assessment involves the use of empirical data on student learning to refine programs and improve student learning (Assessing Academic Programs in Higher Education by Allen 2004). As you design an assessment plan, be sure to align it to your student-learning objectives and outcomes for the course.

The appropriate assessment method depends on numerous variables, including the learning objective to be measured, the intent of the assessment, the timing of the assessment, and the classroom setting.

A Typology of Assessments

(Assessing Student Learning: A common sense guide by Suskie 2004 and Assessing for Learning: Building a sustainable commitment across the institution by Maki 2004)

Angelo and Cross developed a list of 50 classroom assessment techniques (CAT) that you might consider but not every CAT is appropriate for every situation so faculty should weigh the pro's and con's.pdf and choose the right assessment tool.pdf.

- Assess at the start of the course. By knowing the students’ level of knowledge prior to the course or unit, you can tailor your teaching to better meet their needs.

- Assess student learning often. Rather than only assessing learning at the end of units, assess how well the students are learning at intermediate points as well.

- Multiple choice exams allow for easy testing of large groups of students but are often not the best choice. In situations where multiple choice is the best option, please see these tips for designing multiple choice questions .

Angelo, T.A. & Cross, K.P. (1993). Classroom assessment techniques: a handbook for college teachers (2 nd ed) . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Barkley, E.F., Major, C.H., & Cross, K.P. (2014). Classroom assessment techniques (2 nd ed) . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Bull, B. (2014) 10 Assessment Design Tips for Increasing Online Student Retention, Satisfaction and Learning ( http://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/online-education/10-assessment-design-tips-increasing-retention-satisfaction-student-learning-online-courses/?campaign=FF140203article#sthash.GAYkXAMH.dpuf )

Maki, P. L. "Beginning with dialogue about teaching and learning." Maki, PL, Assessing for learning: Building a sustainable commitment across the institution, Sterling, VA: Stylus/AAHE (2004): 31-57. Suskie, Linda. "Assessing student learning: A common sense guide. Bolton, MA." (2004).

20-Minute Mentor Tips

Through our institution subscription to 20-Minute Mentor you have countless teaching tip videos available at the click of a button. Here are a few related to this topic:

- How can I use classroom assessment techniques (CATs) online?

- How can I make my multiple choice tests more effective?

- How can I make my exams more accessible?

If you have not signed up for your subaccount, here is how .

For more information, or for a consultation about your course, please contact Faculty Development at CETL. We can help you identify assessment tools that align with your course objectives, and help you determine how best to combine assessments using a variety of approaches across in-person, remote, synchronous, and asynchronous modes. Email us at [email protected] and we will get back to you as soon as possible.

Quick Links

- Aligning to Course Objectives

- Alternative Authentic Assessment Methods

- Formative and Summative Assessment

- Developing Multiple Choice Questions

- Assessment as Feedback

- Quick Tips for Designing Assessments

- Bias and Exclusion in Assessment

- ChatGPT AI impact on Teaching and Learning

- 50 Classroom Assessment Techniques (CATS)

Consult with our CETL Professionals

Consultation services are available to all UConn faculty at all campuses at no charge.

Center for Teaching

Student assessment in teaching and learning.

Much scholarship has focused on the importance of student assessment in teaching and learning in higher education. Student assessment is a critical aspect of the teaching and learning process. Whether teaching at the undergraduate or graduate level, it is important for instructors to strategically evaluate the effectiveness of their teaching by measuring the extent to which students in the classroom are learning the course material.

This teaching guide addresses the following: 1) defines student assessment and why it is important, 2) identifies the forms and purposes of student assessment in the teaching and learning process, 3) discusses methods in student assessment, and 4) makes an important distinction between assessment and grading., what is student assessment and why is it important.

In their handbook for course-based review and assessment, Martha L. A. Stassen et al. define assessment as “the systematic collection and analysis of information to improve student learning.” (Stassen et al., 2001, pg. 5) This definition captures the essential task of student assessment in the teaching and learning process. Student assessment enables instructors to measure the effectiveness of their teaching by linking student performance to specific learning objectives. As a result, teachers are able to institutionalize effective teaching choices and revise ineffective ones in their pedagogy.

The measurement of student learning through assessment is important because it provides useful feedback to both instructors and students about the extent to which students are successfully meeting course learning objectives. In their book Understanding by Design , Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe offer a framework for classroom instruction—what they call “Backward Design”—that emphasizes the critical role of assessment. For Wiggens and McTighe, assessment enables instructors to determine the metrics of measurement for student understanding of and proficiency in course learning objectives. They argue that assessment provides the evidence needed to document and validate that meaningful learning has occurred in the classroom. Assessment is so vital in their pedagogical design that their approach “encourages teachers and curriculum planners to first ‘think like an assessor’ before designing specific units and lessons, and thus to consider up front how they will determine if students have attained the desired understandings.” (Wiggins and McTighe, 2005, pg. 18)

For more on Wiggins and McTighe’s “Backward Design” model, see our Understanding by Design teaching guide.

Student assessment also buttresses critical reflective teaching. Stephen Brookfield, in Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher, contends that critical reflection on one’s teaching is an essential part of developing as an educator and enhancing the learning experience of students. Critical reflection on one’s teaching has a multitude of benefits for instructors, including the development of rationale for teaching practices. According to Brookfield, “A critically reflective teacher is much better placed to communicate to colleagues and students (as well as to herself) the rationale behind her practice. She works from a position of informed commitment.” (Brookfield, 1995, pg. 17) Student assessment, then, not only enables teachers to measure the effectiveness of their teaching, but is also useful in developing the rationale for pedagogical choices in the classroom.

Forms and Purposes of Student Assessment

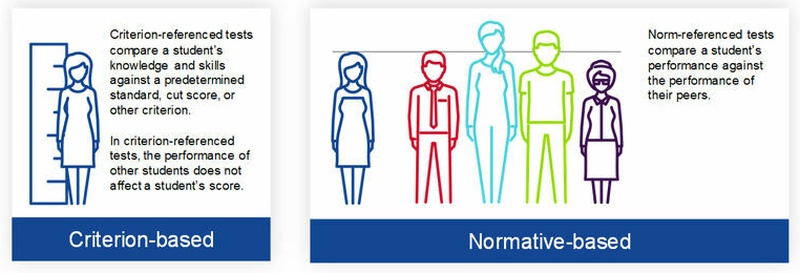

There are generally two forms of student assessment that are most frequently discussed in the scholarship of teaching and learning. The first, summative assessment , is assessment that is implemented at the end of the course of study. Its primary purpose is to produce a measure that “sums up” student learning. Summative assessment is comprehensive in nature and is fundamentally concerned with learning outcomes. While summative assessment is often useful to provide information about patterns of student achievement, it does so without providing the opportunity for students to reflect on and demonstrate growth in identified areas for improvement and does not provide an avenue for the instructor to modify teaching strategy during the teaching and learning process. (Maki, 2002) Examples of summative assessment include comprehensive final exams or papers.

The second form, formative assessment , involves the evaluation of student learning over the course of time. Its fundamental purpose is to estimate students’ level of achievement in order to enhance student learning during the learning process. By interpreting students’ performance through formative assessment and sharing the results with them, instructors help students to “understand their strengths and weaknesses and to reflect on how they need to improve over the course of their remaining studies.” (Maki, 2002, pg. 11) Pat Hutchings refers to this form of assessment as assessment behind outcomes. She states, “the promise of assessment—mandated or otherwise—is improved student learning, and improvement requires attention not only to final results but also to how results occur. Assessment behind outcomes means looking more carefully at the process and conditions that lead to the learning we care about…” (Hutchings, 1992, pg. 6, original emphasis). Formative assessment includes course work—where students receive feedback that identifies strengths, weaknesses, and other things to keep in mind for future assignments—discussions between instructors and students, and end-of-unit examinations that provide an opportunity for students to identify important areas for necessary growth and development for themselves. (Brown and Knight, 1994)

It is important to recognize that both summative and formative assessment indicate the purpose of assessment, not the method . Different methods of assessment (discussed in the next section) can either be summative or formative in orientation depending on how the instructor implements them. Sally Brown and Peter Knight in their book, Assessing Learners in Higher Education, caution against a conflation of the purposes of assessment its method. “Often the mistake is made of assuming that it is the method which is summative or formative, and not the purpose. This, we suggest, is a serious mistake because it turns the assessor’s attention away from the crucial issue of feedback.” (Brown and Knight, 1994, pg. 17) If an instructor believes that a particular method is formative, he or she may fall into the trap of using the method without taking the requisite time to review the implications of the feedback with students. In such cases, the method in question effectively functions as a form of summative assessment despite the instructor’s intentions. (Brown and Knight, 1994) Indeed, feedback and discussion is the critical factor that distinguishes between formative and summative assessment.

Methods in Student Assessment

Below are a few common methods of assessment identified by Brown and Knight that can be implemented in the classroom. [1] It should be noted that these methods work best when learning objectives have been identified, shared, and clearly articulated to students.

Self-Assessment

The goal of implementing self-assessment in a course is to enable students to develop their own judgement. In self-assessment students are expected to assess both process and product of their learning. While the assessment of the product is often the task of the instructor, implementing student assessment in the classroom encourages students to evaluate their own work as well as the process that led them to the final outcome. Moreover, self-assessment facilitates a sense of ownership of one’s learning and can lead to greater investment by the student. It enables students to develop transferable skills in other areas of learning that involve group projects and teamwork, critical thinking and problem-solving, as well as leadership roles in the teaching and learning process.

Things to Keep in Mind about Self-Assessment

- Self-assessment is different from self-grading. According to Brown and Knight, “Self-assessment involves the use of evaluative processes in which judgement is involved, where self-grading is the marking of one’s own work against a set of criteria and potential outcomes provided by a third person, usually the [instructor].” (Pg. 52)

- Students may initially resist attempts to involve them in the assessment process. This is usually due to insecurities or lack of confidence in their ability to objectively evaluate their own work. Brown and Knight note, however, that when students are asked to evaluate their work, frequently student-determined outcomes are very similar to those of instructors, particularly when the criteria and expectations have been made explicit in advance.

- Methods of self-assessment vary widely and can be as eclectic as the instructor. Common forms of self-assessment include the portfolio, reflection logs, instructor-student interviews, learner diaries and dialog journals, and the like.

Peer Assessment

Peer assessment is a type of collaborative learning technique where students evaluate the work of their peers and have their own evaluated by peers. This dimension of assessment is significantly grounded in theoretical approaches to active learning and adult learning . Like self-assessment, peer assessment gives learners ownership of learning and focuses on the process of learning as students are able to “share with one another the experiences that they have undertaken.” (Brown and Knight, 1994, pg. 52)

Things to Keep in Mind about Peer Assessment

- Students can use peer assessment as a tactic of antagonism or conflict with other students by giving unmerited low evaluations. Conversely, students can also provide overly favorable evaluations of their friends.

- Students can occasionally apply unsophisticated judgements to their peers. For example, students who are boisterous and loquacious may receive higher grades than those who are quieter, reserved, and shy.

- Instructors should implement systems of evaluation in order to ensure valid peer assessment is based on evidence and identifiable criteria .

According to Euan S. Henderson, essays make two important contributions to learning and assessment: the development of skills and the cultivation of a learning style. (Henderson, 1980) Essays are a common form of writing assignment in courses and can be either a summative or formative form of assessment depending on how the instructor utilizes them in the classroom.

Things to Keep in Mind about Essays

- A common challenge of the essay is that students can use them simply to regurgitate rather than analyze and synthesize information to make arguments.

- Instructors commonly assume that students know how to write essays and can encounter disappointment or frustration when they discover that this is not the case for some students. For this reason, it is important for instructors to make their expectations clear and be prepared to assist or expose students to resources that will enhance their writing skills.

Exams and time-constrained, individual assessment

Examinations have traditionally been viewed as a gold standard of assessment in education, particularly in university settings. Like essays they can be summative or formative forms of assessment.

Things to Keep in Mind about Exams

- Exams can make significant demands on students’ factual knowledge and can have the side-effect of encouraging cramming and surface learning. On the other hand, they can also facilitate student demonstration of deep learning if essay questions or topics are appropriately selected. Different formats include in-class tests, open-book, take-home exams and the like.

- In the process of designing an exam, instructors should consider the following questions. What are the learning objectives that the exam seeks to evaluate? Have students been adequately prepared to meet exam expectations? What are the skills and abilities that students need to do well? How will this exam be utilized to enhance the student learning process?

As Brown and Knight assert, utilizing multiple methods of assessment, including more than one assessor, improves the reliability of data. However, a primary challenge to the multiple methods approach is how to weigh the scores produced by multiple methods of assessment. When particular methods produce higher range of marks than others, instructors can potentially misinterpret their assessment of overall student performance. When multiple methods produce different messages about the same student, instructors should be mindful that the methods are likely assessing different forms of achievement. (Brown and Knight, 1994).

For additional methods of assessment not listed here, see “Assessment on the Page” and “Assessment Off the Page” in Assessing Learners in Higher Education .

In addition to the various methods of assessment listed above, classroom assessment techniques also provide a useful way to evaluate student understanding of course material in the teaching and learning process. For more on these, see our Classroom Assessment Techniques teaching guide.

Assessment is More than Grading

Instructors often conflate assessment with grading. This is a mistake. It must be understood that student assessment is more than just grading. Remember that assessment links student performance to specific learning objectives in order to provide useful information to instructors and students about student achievement. Traditional grading on the other hand, according to Stassen et al. does not provide the level of detailed and specific information essential to link student performance with improvement. “Because grades don’t tell you about student performance on individual (or specific) learning goals or outcomes, they provide little information on the overall success of your course in helping students to attain the specific and distinct learning objectives of interest.” (Stassen et al., 2001, pg. 6) Instructors, therefore, must always remember that grading is an aspect of student assessment but does not constitute its totality.

Teaching Guides Related to Student Assessment

Below is a list of other CFT teaching guides that supplement this one. They include:

- Active Learning

- An Introduction to Lecturing

- Beyond the Essay: Making Student Thinking Visible in the Humanities

- Bloom’s Taxonomy

- How People Learn

- Syllabus Construction

References and Additional Resources

This teaching guide draws upon a number of resources listed below. These sources should prove useful for instructors seeking to enhance their pedagogy and effectiveness as teachers.

Angelo, Thomas A., and K. Patricia Cross. Classroom Assessment Techniques: A Handbook for College Teachers . 2 nd edition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1993. Print.

Brookfield, Stephen D. Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1995. Print.

Brown, Sally, and Peter Knight. Assessing Learners in Higher Education . 1 edition. London ; Philadelphia: Routledge, 1998. Print.

Cameron, Jeanne et al. “Assessment as Critical Praxis: A Community College Experience.” Teaching Sociology 30.4 (2002): 414–429. JSTOR . Web.

Gibbs, Graham and Claire Simpson. “Conditions under which Assessment Supports Student Learning. Learning and Teaching in Higher Education 1 (2004): 3-31.

Henderson, Euan S. “The Essay in Continuous Assessment.” Studies in Higher Education 5.2 (1980): 197–203. Taylor and Francis+NEJM . Web.

Maki, Peggy L. “Developing an Assessment Plan to Learn about Student Learning.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 28.1 (2002): 8–13. ScienceDirect . Web. The Journal of Academic Librarianship.

Sharkey, Stephen, and William S. Johnson. Assessing Undergraduate Learning in Sociology . ASA Teaching Resource Center, 1992. Print.

Wiggins, Grant, and Jay McTighe. Understanding By Design . 2nd Expanded edition. Alexandria, VA: Assn. for Supervision & Curriculum Development, 2005. Print.

[1] Brown and Night discuss the first two in their chapter entitled “Dimensions of Assessment.” However, because this chapter begins the second part of the book that outlines assessment methods, I have collapsed the two under the category of methods for the purposes of continuity.

Teaching Guides

- Online Course Development Resources

- Principles & Frameworks

- Pedagogies & Strategies

- Reflecting & Assessing

- Challenges & Opportunities

- Populations & Contexts

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

Jump to main content

Center for the Enhancement of Teaching & Learning

Course Assessment Toolkit

This toolkit provides resources to help instructors create measurable learning outcomes and develop classroom assessments to track student learning.

- Teaching Toolkits

- Course Assessment Toolbox

Course-level assessment is a process of systematically examining and refining the fit between the course activities and what students should know at the end of the course. It involves both formative and summative assessment of student learning. The most effective course assessment is done throughout the semester, provides opportunities for low-stakes, formative assessment, and is based in authentic demonstrations of a students' learning. The key to effective course assessment is establishing course learning outcomes and developing course assessments that will provide evidence of achievement (Angelo & Cross, 1993).

This toolkit provides help with developing course learning outcomes and thinking through the type of assessment you want to conduct and how to develop effective assessments.

How do I develop course learning outcomes?

Developing course learning outcomes comes down to thinking through the big ideas you want students to learn from your course. It's important to think about the essential knowledge, skills, and dispositions you want students to leave class with and be able to use later. It is also important to think about what knowledge and skills students need in the next course in your program to ensure their continued success in the major.

For a detailed process to develop course learning outcomes download the Developing Course-Level Student Learning Outcomes Workbook.

What kind of assessment should you conduct in class?

There are two types of assessment - formative and summative. Formative assessment is done early and often in a course to track student learning over time. Formative assessments are low-stakes assessments that won't harm a student's grade but will keep them engaged in course content. They help students identify strengths and areas for improvement in their own learning while also providing faculty with information about how students are grasping content, allowing instructors to adjust a course as needed.

- Read more about formative and summative assessment

- Watch the CETL webinar on implementing low-stakes assessment in large courses

How can I determine if students can apply course concepts?

Authentic assessments can tell you a lot about students' ability to apply course concepts and think critically about the content. Authentic assessment focuses on application of course knowledge to a new situation using complex, real-world situations that require a student to think about application of knowledge and skills in society rather than just in the classroom. This moves instructors away from multiple choice and memorization, will improve learning, and limit academic dishonesty.

- Read more about Authentic Assessment

How do I develop a course assessment?

To develop an assessment you want to think about how a student will demonstrate their understanding of a course concept or demonstrate their skill. Developing an effective Classroom Assessment Technique (CAT) takes some thought because you want to be sure that the CAT is assessing what you want it to assess.

For a detailed process to develop classroom assessments download the Developing Classroom Assessment Techniques Workbook and the CAT KIT .

The workbook provides a step-by-step process for developing classroom assessments. The CAT KIT details six assessments and discusses how to develop them for your own needs and how to use the data. Examples of assessments are provided.

How do I align my assessments to my learning outcomes?

Dr. Aaron Haberman explores different summative assessment methods and will help you develop or refine a high stakes summative assessment that directly aligns with one or more of your course-level student learning outcomes.

- Creating Summative Assessments that Align to Student Learning Outcomes

Angelo, T. A., & Cross, K. P. (1993). Classroom assessment techniques: A handbook for college teachers (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, p. 7-11

Support for Course Assessment

If you need support developing course learning outcomes or assessment you can set up a personal consultation with CETL.

Contact UNC

Social media.

- UNC Overview

- Awards & Accolades

- Organizational Chart

- Strategic Plan

- Accreditation

- Student Consumer Information

- Sustainability

- COURSE CATALOG

- GIVE TO UNC

- Open Records Act

Page Last Updated: Today | Contact for this Page: CETL

Privacy Policy | Affirmative Action/Equal Employment Opportunity/Title IX Policy & Coordinator

Design and Grade Course Work

This resource provides a brief introduction to designing your course assessment strategy based on your course learning objectives and introduces best practices in assessment design. It also addresses important issues in grading, including strategies to curb cheating and grading methods that reduce implicit bias and provide actionable feedback for students.

In this document, assessments refer to all the ways students’ learning can be measured. This includes summative assessments such as tests and papers, but also formative assessments such as a survey to gauge understanding of course concepts.

Table of Contents:

Crafting effective assessments

Encouraging academic integrity.

- Grading fairly

Resources & further reading

Tie assessments to the course learning objectives. To determine what kinds of assessments to use in your course, consider what you want the students to learn to do and how that can be measured. When designing an overall plan, it is important to begin with the end in mind.

Consider what type of assessments best fit your learning objectives. For example, a case study is appropriate for measuring students’ ability to apply skills to a new situation, while a multiple choice exam is better for testing their understanding of concepts. This table of assessment choices from Carnegie Mellon University can help you think about the alignment of learning objectives and types of assessments.

Rethink traditional assessment to enhance the learning experience. At the end of a learning unit or module, summative assessments are frequently employed to measure students’ learning. These assessments are usually graded, cumulative in design and take the form of a midterm exam, research paper or final project. Consider replacing a traditional assessment with an authentic assessment situated in a meaningful, real-world context or modifying existing assessments to “do” the subject instead of recalling information. Here are some high-level questions for to get you started:

- Does this assessment replicate or simulate the contexts in which adults are “tested” in the workplace, civic life or personal life?

- Does this assessment challenge students to use what they’ve learned in solving or analyzing new problems?

- Does this assessment provide direct evidence of learning?

- Is this assessment realistic? Have students been able to practice along the way?

- Does this assessment truly demonstrate success and mastery of a skill students should have at the end of your course?

Further considerations for authentic assessment design are available in this guide from University of Illinois.

In practice, authentic assessments look different by discipline and level of the course. A good starting point is to research common examples of alternative assessments , but consider researching approaches in your discipline. There are also ways to improve traditional assessments such as quizzes to be a measure of true learning instead of memorization.

Our page on Alternative Strategies for Assessment and Grading outlines some options for creating assessment activities and policies which are learning-focused, while also being equitable and compassionate. The suggestions are loosely grouped by expected faculty time commitment.

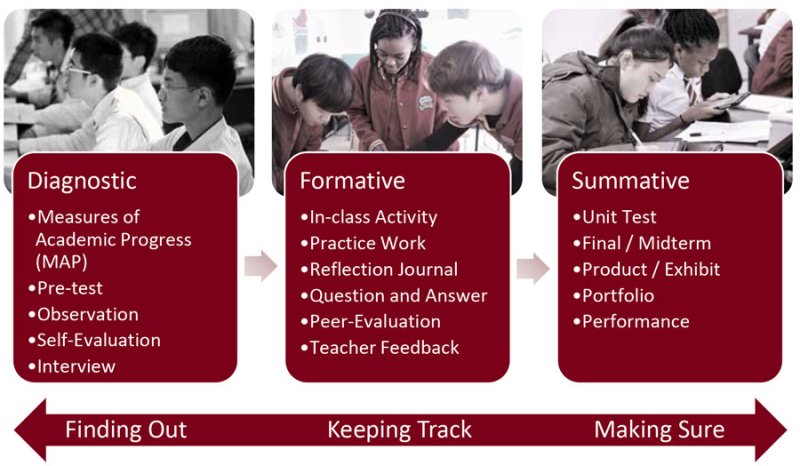

Tailor learning by assessing previous knowledge. At the beginning of a learning unit or module, use a diagnostic assessment to gain insight into students’ existing understanding and skills prior to beginning a new concept. Examples of diagnostic assessments include: discussion, informal quiz, survey or a quick write paper ( see this list for more ideas ).

Use frequent informal assessments to monitor progress. Formative assessments are any assessments implemented to evaluate progress during the learning experience. When possible, provide several low-stakes opportunities for students to demonstrate progress throughout the course. Formative assessments provide five major benefits: (1)

- Students can identify their strengths and weaknesses with a particular concept and request additional support during the learning unit.

- Instructors can target areas where students are struggling that should be addressed either individually or in whole class activities before a more high-stakes assessment.

- Formative assessments can be reviewed and evaluated by peers which provides additional opportunities to learn, both for the reviewer and the student being reviewed.

- Informal, low-stakes assessments reduce student anxiety.

- A more frequent, immediate feedback loop can make some assessments (like graded quizzes) less necessary.

Examples include quick assessments like polls which can make large classes feel smaller or more informal, or end-of-class reflection questions on the day’s content. This longer list of low-stakes, formative assessments can help you find methods that work with your content and goals.

Use rubrics when possible. Students are likely to perform better on assessments when the grading criteria are clear. Research suggests that assessments designed with a corresponding rubric lead to an increased attention to detail and fewer misunderstandings in submitted work. (2) If you are interested in creating rubrics, Arizona State University has a detailed guide to get started .

Break up larger assessments into smaller parts. Scaffolding major or long-term work into smaller assignments with different deadlines gives students natural structure, helps with time and project management skills and provides multiple opportunities for students to receive constructive feedback. Students also benefit from scaffolding when:

- Rubrics are provided to assess discrete skills and evaluate student practice via smaller pre-assignments.

- The stakes are lowered for preliminary work.

- Opportunities are offered for rewrite or rework based on feedback.

Use practices that promote inclusive assessment design . Take inventory of the explicit and implicit norms and biases of your course assessments. For example, are your assessment questions phrased in a way that all students (including non-native English speakers) can be successful? Do your course assessments meet basic accessibility standards, including being appropriate for students with visual or hearing needs?

The Duke Community Standard embraces the principle that “intellectual and academic honesty are at the heart of the academic life of any university. It is the responsibility of all students to understand and abide by Duke’s expectations regarding academic work.” (3) Learning the rules of legitimacy in academic work is part of college education, so the topic of cheating and plagiarism should be embraced as part of ongoing discussion among students, and faculty instructors should remind students of this obligation throughout their courses.

Include a statement about cheating and plagiarism in your syllabus. Remind students that they must uphold the standards of student conduct as an obligation of participating in our learning community. This can be reinforced before important assessments as well. Studies have shown that when students have to manually agree to the Honor Pledge prior to submitting an assignment (either online or in person), they are less likely to cheat. (4)

Specify where training is available. Because of their cultural or academic experiences, some students may not be familiar with what constitutes plagiarism in your course. Students can use library resources to learn more about plagiarism and take the university’s plagiarism tutorial .

Include specific guidelines for collaboration, citation and the use of electronic sources for every assessment. For example, it may be necessary to define what kinds of online sources are considered cheating for your discipline (for example, online translators in language courses) or help students understand how to cite correctly .

Provide ongoing feedback to reduce the temptation to cheat. Students are more likely to seek short cuts when they don’t know how to approach a task. Requiring students to turn in smaller parts of a paper or project for feedback and a grade before the final deadline can lessen the risk of cheating. Having multiple milestones on larger assessments reduces the stress of finishing a paper at the last minute or cramming for a final exam.

Ask questions that have no single right answer. The most direct approach to reduce cheating is to design open-ended assessment items. When writing test or quiz questions ask yourself: could this answer be easily discovered online? If so, rewrite your question to elicit more critical thinking from your students.