Reimagining the postpandemic workforce

As the pandemic begins to ease, many companies are planning a new combination of remote and on-site working, a hybrid virtual model in which some employees are on premises, while others work from home. The new model promises greater access to talent, increased productivity for individuals and small teams , lower costs, more individual flexibility, and improved employee experiences .

While these potential benefits are substantial, history shows that mixing virtual and on-site working might be a lot harder than it looks—despite its success during the pandemic. Consider how Yahoo! CEO Marissa Mayer ended that company’s remote-working experiment in 2013, observing that the company needed to become “one Yahoo!” again, or how HP Inc. did the same that year. Specific reasons may have varied. But in each case, the downsides of remote working at scale came to outweigh the positives.

These downsides arise from the organizational norms that underpin culture and performance— ways of working , as well as standards of behavior and interaction—that help create a common culture, generate social cohesion, and build shared trust. To lose sight of them during a significant shift to virtual-working arrangements is to risk an erosion over the long term of the very trust, cohesion, and shared culture that often helps remote working and virtual collaboration to be effective in the short term.

It also risks letting two organizational cultures emerge, dominated by the in-person workers and managers who continue to benefit from the positive elements of co-location and in-person collaboration, while culture and social cohesion for the virtual workforce languish. When this occurs, remote workers can soon feel isolated, disenfranchised, and unhappy, the victims of unintentional behavior in an organization that failed to build a coherent model of, and capabilities for, virtual and in-person work. The sense of belonging, common purpose, and shared identity that inspires all of us to do our best work gets lost. Organizational performance deteriorates accordingly.

Now is the time, as you reimagine the postpandemic organization , to pay careful attention to the effect of your choices on organizational norms and culture. Focus on the ties that bind your people together. Pay heed to core aspects of your own leadership and that of your broader group of leaders and managers. Your opportunity is to fashion the hybrid virtual model that best fits your company, and let it give birth to a new shared culture for all your employees that provides stability, social cohesion, identity, and belonging, whether your employees are working remotely, on premises, or in some combination of both.

Avoiding the pitfalls of remote working requires thinking carefully about leadership and management in a hybrid virtual world. Interactions between leaders and teams provide an essential locus for creating the social cohesion and the unified hybrid virtual culture that organizations need in the next normal.

Cutting the ties that bind

If you happen to believe that remote work is no threat to social ties, consider the experience of Skygear.io, a company that provides an open-source platform for app development. Several years ago, Skygear was looking to accommodate several new hires by shifting to a hybrid remote-work model for their 40-plus-person team. The company soon abandoned the idea. Team members who didn’t come to the office missed out on chances to strengthen their social ties through ad hoc team meals and discussions around interesting new tech launches. The wine and coffee tastings that built cohesion and trust had been lost. Similarly, GoNoodle employees found themselves at Zoom happy hour longing for the freshly remodeled offices they had left behind at lockdown. “We had this killer sound system,” one employee, an extrovert who yearns for time with her colleagues, told the New York Times . “You know—we’re drinking coffee, or maybe, ‘Hey, want to take a walk?’ I miss that.” 1 Clive Thompson, “What if working from home goes on … forever?,” New York Times , June 9, 2020, nytimes.com. Successful workplace cultures rely on these kinds of social interactions. That’s something Yahoo!’s Mayer recognized in 2013 when she said, “We need to be one Yahoo!, and that starts with physically being together,” having the “interactions and experiences that are only possible” face-to-face, such as “hallway and cafeteria discussions, meeting new people, and impromptu team meetings.” 2 Kara Swisher, “‘Physically together’: Here’s the internal Yahoo no-work-from-home memo for remote workers and maybe more,” All Things Digital, February 22, 2013, allthingsd.com.

Or consider how quickly two cultures emerged recently in one of the business units of a company we know. Within this business unit, one smaller group was widely distributed in Cape Town, Los Angeles, Mumbai, Paris, and other big cities. The larger group was concentrated in Chicago, with a shared office in the downtown area. When a new global leader arrived just prior to the pandemic, the leader based herself in Chicago and quickly bonded with the in-person group that worked alongside her in the office. As the pandemic began, but before everyone was sent home to work remotely, the new leader abruptly centralized operations into a crisis nerve center made up of everyone in the on-site group. The new arrangement persisted as remote working began. Meanwhile, the smaller group, which had already been remote working in other cities, quickly lost visibility into, and participation in, the new workflows and resources that had been centralized among the on-site group, even though that on-site group was now working virtually too. Newly created and highly sought-after assignments (which were part of the business unit’s crisis response) went to members of the formerly on-site group, while those in the distributed group found many of their areas of responsibility reduced or taken away entirely. Within a matter of months, key employees in the smaller, distributed group were unhappy and underperforming.

The new global leader, in her understandable rush to address the crisis, had failed to create a level playing field and instead (perhaps unintentionally) favored one set of employees over the other. For us, it was stunning to observe how quickly, in the right circumstances, everything could go wrong. Avoiding these pitfalls requires thinking carefully about leadership and management in a hybrid virtual world, and about how smaller teams respond to new arrangements for work. Interactions between leaders and teams provide an essential locus for creating the social cohesion and the unified hybrid virtual culture that organizations need in the next normal.

Choose your model

Addressing working norms, and their effect on culture and performance, requires making a basic decision: Which part of the hybrid virtual continuum (exhibit) is right for your organization? The decision rests on the factors for which you’re optimizing. Is it real-estate cost? Employee productivity? Access to talent? The employee experience? All of these are worthy goals, but in practice it can be difficult to optimize one without considering its effect on the others. Ultimately, you’re left with a difficult problem to solve—one with a number of simultaneous factors and that defies simple formulas.

That said, we can make general points that apply across the board. These observations, which keep a careful eye on the organizational norms and ways of working that inform culture and performance, address two primary factors: the type of work your employees tend to do and the physical spaces you need to support that work.

First let’s eliminate the extremes. We’d recommend a fully virtual model to very few companies, and those that choose this model would likely operate in specific industries such as outsourced call centers, customer service, contact telesales, publishing, PR, marketing, research and information services, IT, and software development, and under specific circumstances. Be cautious if you think better access to talent or lower real-estate cost—which the all-virtual model would seem to optimize—outweigh all other considerations. On the other hand, few companies would be better off choosing an entirely on-premises model, given that at least some of their workers need flexibility because of work–life or health constraints. That leaves most companies somewhere in the middle, with a hybrid mix of remote and on-site working.

The physical spaces needed for work—or not

Being in the middle means sorting out the percentage of your employees who are working remotely and how often they are doing so. Let’s say 80 percent of your employees work remotely but do so only one day per week. In the four days they are on premises, they are likely getting all the social interaction and connection needed for collaboration, serendipitous idea generation, innovation, and social cohesiveness. In this case, you might be fine with the partially remote, large headquarters (HQ) model in the exhibit.

If, instead, a third of your employees are working remotely but doing so 90 percent of the time, the challenges to social cohesion are more pronounced. The one-third of your workforce will miss out on social interaction with the two-thirds working on-premises—and the cohesion, coherence, and cultural belonging that comes with it. One solution would be to bring those remote workers into the office more frequently, in which case multiple hubs, or multiple microhubs (as seen in the exhibit), might be the better choice. Not only is it easier to travel to regional hubs than to a central HQ, at least for employees who don’t happen to live near that HQ, but more dispersed hubs make the in-person culture less monolithic. Moreover, microhubs can often be energizing, fun, and innovative places in which to collaborate and connect with colleagues, which further benefits organizational culture.

Productivity and speed

Now let’s begin to factor in other priorities, such as employee productivity. Here the question becomes less straightforward, and the answer will be unique to your circumstances. When tackling the question, be sure to go beyond the impulse to monitor inputs and activity as a proxy for productivity. Metrics focused on inputs or volume of activity have always been a poor substitute for the true productivity that boosts outcomes and results, no matter how soothing it might be to look at the company parking lot to see all the employees who have arrived early in the day, and all those who are leaving late. Applied to a hybrid model, counting inputs might leave you grasping at the number of hours that employees are spending in front of their computers and logged into your servers. Yet the small teams that are the lifeblood of today’s organizational success thrive with empowering, less-controlling management styles. Better to define the outcomes you expect from your small teams rather than the specific activities or the time spent on them.

Would you like to learn more about our People & Organizational Performance Practice ?

In addition to giving teams clear objectives, and both the accountability and autonomy for delivering them, leaders need to guide, inspire, and enable small teams, helping them overcome bureaucratic challenges that bog them down, such as organizational silos and resource inertia—all while helping to direct teams to the best opportunities, arming them with the right expertise, and giving them the tools they need to move fast. Once teams and individuals understand what they are responsible for delivering, in terms of results, leaders should focus on monitoring the outcome-based measurements. When leaders focus on outcomes and outputs, virtual workers deliver higher-quality work.

In this regard, you can take comfort in Netflix (which at the time of this writing is the 32nd largest company in the world by market capitalization), which thrives without limiting paid time off or specifying how much “face time” workers must spend in the office. Netflix measures productivity by outcomes, not inputs—and you should do the same.

No matter which model you choose for hybrid virtual work, your essential task will be to carefully manage the organizational norms that matter most when adopting any of these models. Let’s dive more deeply into those now.

Managing the transition

Organizations thrive through a sense of belonging and shared purpose that can easily get lost when two cultures emerge. When this happens, our experience—and the experience at HP, IBM, and Yahoo!—is that the in-person culture comes to dominate, disenfranchising those who are working remotely. The difficulty arises through a thousand small occurrences: when teams mishandle conference calls such that remote workers feel overlooked, and when collaborators use on-site white boards rather than online collaboration tools such as Miro. But culture can split apart in bigger ways too, as when the pattern of promotions favors on-site employees or when on-premises workers get the more highly sought-after assignments.

Some things simply become more difficult when you are working remotely. Among them are acculturating new joiners; learning via hands-on coaching and apprenticeship; undertaking ambiguous, complex, and collaborative innovations; and fostering the creative collisions through which new ideas can emerge. Addressing these boils down to leadership and management styles, and how those styles and approaches support small teams. Team experience is a critical driver of hybrid virtual culture—and managers and team leaders have an outsize impact on their teams’ experiences.

Managers and leaders

As a rule, the more geographically dispersed the team, the less effective the leadership becomes. Moreover, leaders who were effective in primarily on-site working arrangements may not necessarily prove so in a hybrid virtual approach. Many leaders will now need to “show up” differently when they are interacting with some employees face-to-face and others virtually. By defining and embracing new behaviors that are observable to all, and by deliberately making space for virtual employees to engage in informal interactions, leaders can facilitate social cohesion and trust-building in their teams.

More inspirational. There’s a reason why military commanders tour the troops rather than send emails from headquarters—hierarchical leadership thrives in person. Tom Peters used to call the in-person approach “management by walking around”: “Looking someone in the eye, shaking their hand, laughing with them when in their physical presence creates a very different kind of bond than can be achieved [virtually].” 3 See Tom Peters blog , “The heart of MBWA,” blog entry by Shelley Dolley, February 27, 2013, tompeters.com.

But when the workforce is hybrid virtual, leaders need to rely less on hierarchical and more on inspirational forms of leadership . The dispersed employees working remotely require new leadership behaviors to compensate for the reduced socioemotional cues characteristic of digital channels.

Cultivate informal interactions. Have you ever run into a colleague in the hallway and, by doing so, learned something you didn’t know? Informal interactions and unplanned encounters foster the unexpected cross-pollination of ideas—the exchange of tacit knowledge—that are essential to healthy, innovative organizations. Informal interactions provide a starting point for collegial relationships in which people collaborate on areas of shared interest, thereby bridging organizational silos and strengthening social networks and shared trust within your company.

Informal interactions, which occur more naturally among co-located employees, don’t come about as easily in a virtual environment. Leaders need new approaches to creating them as people work both remotely and on-site. One approach is to leave a part of the meeting agenda free, as a time for employees to discuss any topic. Leaders can also establish an open-door policy and hold virtual “fireside chats,” without any structured content at all, to create a forum for less formal interactions. The goal is for employees, those working remotely and in-person, to feel like they have access to leaders and to the kind of informal interactions that happen on the way to the company cafeteria.

Many leaders will now need to “show up” differently when they are interacting with some employees face-to-face and others virtually. By defining and embracing new behaviors that are observable to all, and by deliberately making space for virtual employees to engage in informal interactions—leaders can facilitate social cohesion and trust-building in their teams.

Further approaches include virtual coffee rooms and social events, as well as virtual conferences in which group and private chat rooms and sessions complement plenary presentations. In between time, make sure you and all your team members are sending text messages to one another and that you are texting your team regularly for informal check-ins. These norms cultivate the habit of connecting informally.

Role model the right stance. It might seem obvious, but research shows that leaders consistently fail to recognize how their actions affect and will be interpreted by others. 4 Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, “How to work for a boss who lacks self-awareness,” Harvard Business Review , April 3, 2018, hbr.org. Consider the location from which you choose to work. If you want to signal that you tolerate virtual work, come into the office every day and join meetings in-person with those who happen to be in the building. This will result in a cultural belief that the HQ or physical offices are the real centers of gravity, and that face time is what’s important.

Come into the office every day, though, and your remote-working employees may soon feel that their choice to work virtually leaves them fewer career opportunities, and that their capabilities and contributions are secondary. By working from home (or a non-office location) a couple days a week, leaders signal that people don’t need to be in the office to be productive or to get ahead. In a hybrid virtual world, seemingly trivial leadership decisions can have outsize effect on the rest of the organization.

Don’t rely solely on virtual interactions. By the same token, despite big technological advancements over the years, nothing can entirely replace face-to-face interactions. Why? In part because so much of communication is nonverbal (even if it’s not the 93 percent that some would assert), but also because so much communication involves equivocal, potentially contentious, or difficult-to-convey subject matter. Face-to-face interactions create significantly more opportunities for rich, informal interactions, emotional connection, and emergent “creative collision” that can be the lifeblood of trust, collaboration, innovation, and culture.

Media richness theory helps us understand the need to match the “richness” of the message with the capabilities of the medium. You wouldn’t let your nephew know of the death of his father by fax, for instance—you would do it in person, if at all possible, and, failing that, by the next richest medium, probably video call. Some communication simply proceeds better face-to-face, and it is up to the leader to match the mode of communication to the equivocality of the message they are delivering.

Reimagining the post-pandemic organization

In other cases, asynchronous communication—such as email and text—are sufficient, and even better, because it allows time for individuals to process information and compose responses after some reflection and thought. However, when developing trust (especially early on in a relationship) or discussing sensitive work-related issues, such as promotions, pay, and performance, face-to-face is preferred, followed by videoconferencing, which, compared with audio, improves the ability for participants to show understanding, anticipate responses, provide nonverbal information, enhance verbal descriptions, manage pauses, and express attitudes. However, compared with face-to-face interaction, it can be difficult in video interactions to notice peripheral cues, control the floor, have side conversations, and point to or manipulate real-world objects.

Whatever the exact mix of communication you choose in a given moment, you will want to convene everyone in person at least one or two times a year, even if the work a particular team is doing can technically be done entirely virtually. In person is where trust-based relationships develop and deepen, and where serendipitous conversations and connections can occur.

Track your informal networks. Corporate organizations consist of multiple, overlapping, and intersecting social networks. As these informal networks widen and deepen, they mobilize talent and knowledge across the enterprise, facilitating and informing cultural cohesiveness while helping to support cross-silo collaboration and knowledge sharing.

Because the hybrid virtual model reduces face-to-face interaction and the serendipitous encounters that occur between people with weak ties , social networks can lose their strength. To counter that risk, leaders should map and monitor the informal networks in their organization with semiannual refreshes of social-network maps. Approaches include identifying the functions or activities where connectivity seems most relevant and then mapping relationships within those priority areas—and then tracking the changes in those relationships over time. Options for obtaining the necessary information include tracking email, observing employees, using existing data (such as time cards and project charge codes), and administering short (five- to 20-minute) questionnaires. It is likely that leaders will need to intervene and create connections between groups that do not naturally interact or that now interact less frequently as a result of the hybrid virtual model.

Hybrid virtual teams

Leadership is crucial, but in the hybrid virtual model, teams (and networks of teams ) also need to adopt new norms and change the way they work if they are to maintain—and improve—productivity, collaboration, and innovation. This means gathering information, devising solutions, putting new approaches into practice, and refining outcomes—and doing it all fast. The difficulty rises when the team is part virtual and part on-site. What follows are specific areas on which to focus.

Create ‘safe’ spaces to learn from mistakes and voice requests

Psychological safety matters in the workplace, obviously, and in a hybrid virtual model it requires more attention. First, because a feeling of safety can be harder to create with some people working on-site and others working remotely. And, second, because it’s often less obvious when safety erodes. Safety arises as organizations purposefully create a culture in which employees feel comfortable making mistakes, speaking up, and generating innovative ideas. Safety also requires helping employees feel supported when they request flexible operating approaches to accommodate personal needs.

Mind the time-zone gaps

The experience of a hybrid virtual team in the same time zone varies significantly from a hybrid virtual team with members in multiple time zones. Among other ills, unmanaged time-zone differences make sequencing workflows more difficult. When people work in different time zones, the default tends toward asynchronous communications (email) and a loss of real-time connectivity. Equally dysfunctional is asking or expecting team members to wake up early or stay up late for team meetings. It can work for a short period of time, but in the medium and longer run it reduces the cohesion that develops through real-time collaboration. (It also forces some team members to work when they’re tired and not at their best.) Moreover, if there is a smaller subgroup on the team in, say, Asia, while the rest are in North America, a two-culture problem can emerge, with the virtual group feeling lesser than. Better to simply build teams with at least four hours of overlap during the traditional workday to ensure time for collaboration.

Keep teams together, when possible, and hone the art of team kickoffs

Established teams, those that have been working together for longer periods of time, are more productive than newer teams that are still forming and storming. The productivity they enjoy arises from clear norms and trust-based relationships—not to mention familiarity with workflows and routines. That said, new blood often energizes a team.

In an entirely on-premises model, chances are you would swap people in and out of your small teams more frequently. The pace at which you do so will likely decline in a hybrid virtual model, in which working norms and team cohesion are more at risk. But don’t take it to an extreme. Teams need members with the appropriate expertise and backgrounds, and the right mix of those tends to evolve over time.

Meanwhile, pay close attention to team kickoffs as you add new people to teams or stand up new ones. Kickoffs should include an opportunity to align the overall goals of the team with those of team members while clarifying personal working preferences.

Keeping track

Once you have your transition to a hybrid virtual model underway, how will you know if it’s working, and whether you maintained or enhanced your organization’s performance culture? Did your access to talent increase, and are you attracting and inspiring top talent? Are you developing and deploying strong leaders? To what extent are all your employees engaged in driving performance and innovation, gathering insights, and sharing knowledge?

The right metrics will depend on your goals, of course. Be wary of trying to achieve across all parameters, though. McKinsey research shows that winning performance cultures emerge from carefully selecting the right combinations of practices (or “recipes”) that, when applied together, create superior organizational performance. Tracking results against these combinations of practices can help indicate, over time, if you’ve managed to keep your unified performance culture intact in the transition to a new hybrid virtual model.

We’ll close by saying you don’t have to make all the decisions about your hybrid virtual model up front and in advance. See what happens. See where your best talent emerges. If you end up finding, say, 30 (or 300) employees clustered around Jakarta, and other groups in Kuala Lumpur and Singapore, ask them what might help them feel a socially supported sense of belonging. To the extent that in-person interactions are important—as we guess they will be—perhaps consider a microhub in one of those cities, if you don’t have one already.

Approached in the right way, the new hybrid model can help you make the most of talent wherever it resides, while lowering costs and making your organization’s performance culture even stronger than before.

Andrea Alexander is an associate partner in McKinsey’s Houston office, where Aaron De Smet is a senior partner and Mihir Mysore is a partner.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Communications get personal: How leaders can engage employees during a return to work

Reimagining the postpandemic organization

Adapting workplace learning in the time of coronavirus

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

About a third of U.S. workers who can work from home now do so all the time

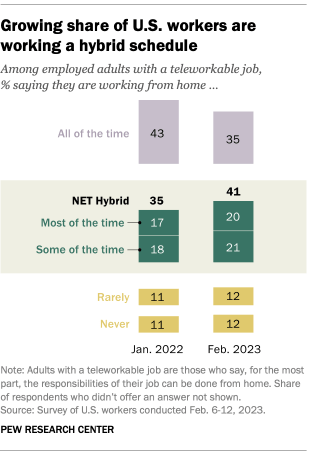

Roughly three years after the COVID-19 pandemic upended U.S. workplaces, about a third (35%) of workers with jobs that can be done remotely are working from home all of the time, according to a new Pew Research Center survey. This is down from 43% in January 2022 and 55% in October 2020 – but up from only 7% before the pandemic.

While the share working from home all the time has fallen off somewhat as the pandemic has gone on, many workers have settled into hybrid work. The new survey finds that 41% of those with jobs that can be done remotely are working a hybrid schedule – that is, working from home some days and from the office, workplace or job site other days. This is up from 35% in January 2022.

Among hybrid workers who are not self-employed, most (63%) say their employer requires them to work in person a certain number of days per week or month. About six-in-ten hybrid workers (59%) say they work from home three or more days in a typical week, while 41% say they do so two days or fewer.

Related: How Americans View Their Jobs

Many hybrid workers would prefer to spend more time working from home than they currently do. About a third (34%) of those who are currently working from home most of the time say, if they had the choice, they’d like to work from home all the time. And among those who are working from home some of the time, half say they’d like to do so all (18%) or most (32%) of the time.

Pew Research Center conducted this analysis to study how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the workplace and specifically how workers with jobs that can be done from home have adapted their work schedules. To do this, we surveyed 5,775 U.S. adults who are working part time or full time and who have only one job or who have more than one job but consider one of them to be their primary job. All the workers who took part are members of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses.

Address-based sampling ensures that nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

Here are the questions used for this analysis, along with responses, and the survey’s methodology .

The majority of U.S. workers overall (61%) do not have jobs that can be done from home. Workers with lower incomes and those without a four-year college degree are more likely to fall into this category. Among those who do have teleworkable jobs, Hispanic adults and those without a college degree are among the most likely to say they rarely or never work from home.

When looking at all employed adults ages 18 and older in the United States, Pew Research Center estimates that about 14% – or roughly 22 million people – are currently working from home all the time.

The advantages and disadvantages of working from home

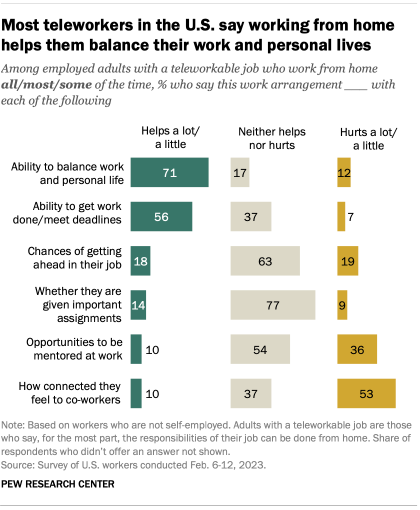

Workers who are not self-employed and who are teleworking at least some of the time see one clear advantage – and relatively few downsides – to working from home. By far the biggest perceived upside to working from home is the balance it provides: 71% of those who work from home all, most or some of the time say doing so helps them balance their work and personal lives. That includes 52% who say it helps them a lot with this.

About one-in-ten (12%) of those who are at least occasionally working from home say it hurts their ability to strike the right work-life balance, and 17% say it neither helps nor hurts. There is no significant gender difference in these views. However, parents with children younger than 18 are somewhat more likely than workers without children in that age range to say working from home is helpful in this regard (76% vs. 69%).

A majority of those who are working from home at least some of the time (56%) say this arrangement helps them get their work done and meet deadlines. Only 7% say working from home hurts their ability to do these things, and 37% say it neither helps nor hurts.

There are other aspects of work – some of them related to career advancement – where the impact of working from home seems minimal:

- When asked how working from home affects whether they are given important assignments, 77% of those who are at least sometimes working from home say it neither helps nor hurts, while 14% say it helps and 9% say it hurts.

- When it comes to their chances of getting ahead at work, 63% of teleworkers say working from home neither helps or hurts, while 18% say it helps and 19% say it hurts.

- A narrow majority of teleworkers (54%) say working from home neither helps nor hurts with opportunities to be mentored at work. Among those who do see an impact, it’s perceived to be more negative than positive: 36% say working from home hurts opportunities to be mentored and 10% say it helps.

One aspect of work that many remote workers say working from home makes more challenging is connecting with co-workers: 53% of those who work from home at least some of the time say working from home hurts their ability to feel connected with co-workers, while 37% say it neither helps nor hurts. Only 10% say it helps them feel connected.

In spite of this, those who work from home all the time or occasionally are no less satisfied with their relationship with co-workers than those who never work from home. Roughly two-thirds of workers – whether they are working exclusively from home, follow a hybrid schedule or don’t work from home at all – say they are extremely or very satisfied with these relationships. In addition, among those with teleworkable jobs, employed adults who work from home all the time are about as likely as hybrid workers to say they have at least one close friend at work.

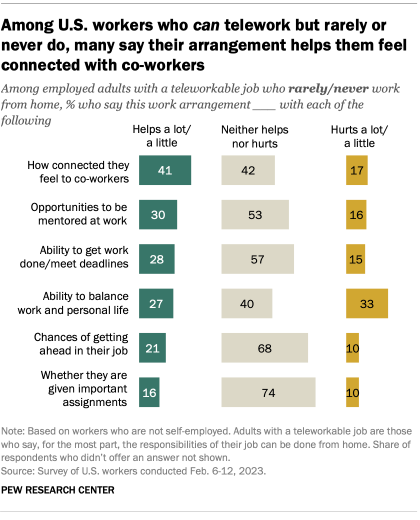

Feeling connected with co-workers is one area where many workers who rarely or never work from home see an advantage in their setup. About four-in-ten of these workers (41%) say the fact that they rarely or never work from home helps in how connected they feel to their co-workers. A similar share (42%) say it neither helps nor hurts, and 17% say it hurts.

At the same time, those who rarely or never work from home are less likely than teleworkers to say their current arrangement helps them achieve work-life balance. A third of these workers say the fact that they rarely or never work from home hurts their ability to balance their work and personal lives, while 40% say it neither helps nor hurts and 27% say it helps.

When it comes to other aspects of work, many of those who rarely or never work from home say their arrangement is neither helpful nor hurtful. This is true when it comes to opportunities to be mentored (53% say this), their ability to get work done and meet deadlines (57%), their chances of getting ahead in their job (68%) and whether they are given important assignments (74%).

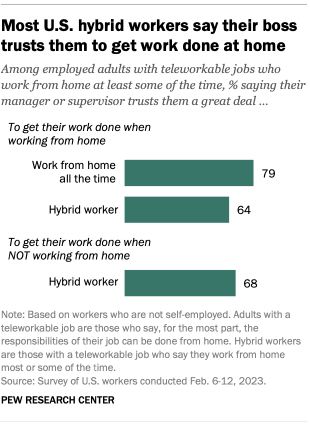

Most adults with teleworkable jobs who work from home at least some of the time (71%) say their manager or supervisor trusts them a great deal to get their work done when they’re doing so. Those who work from home all the time are the most likely to feel trusted: 79% of these workers say their manager trusts them a great deal, compared with 64% of hybrid workers.

Hybrid workers feel about as trusted when they’re not working from home: 68% say their manager or supervisor trusts them a great deal to get their work done when they’re not teleworking.

Note: Here are the questions used for this analysis, along with responses, and the survey’s methodology .

- Business & Workplace

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

Kim Parker is director of social trends research at Pew Research Center

A look at small businesses in the U.S.

Majorities of adults see decline of union membership as bad for the u.s. and working people, a look at black-owned businesses in the u.s., from businesses and banks to colleges and churches: americans’ views of u.s. institutions, 2023 saw some of the biggest, hardest-fought labor disputes in recent decades, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

Golf, rent, and commutes: 7 impacts of working from home

The pandemic sharply accelerated trends of people working from home, leaving lasting impacts on how we work going forward. Stanford scholar Nicholas Bloom details how working from home is affecting the office, our homes, and more.

The massive surge in the number of people working from home may be the largest change to the U.S. economy since World War II, says Stanford scholar Nicholas Bloom .

And the shift to working from home, catalyzed by the pandemic, is here to stay, with further growth expected in the long run through improvements in technology.

Looking at data going back to 1965, when less than 1% of people worked from home, the number of people working from home had been rising continuously up to the pandemic, doubling roughly every 15 years, said Bloom, the William D. Eberle Professor in Economics in the School of Humanities and Sciences and professor, by courtesy, at Stanford Graduate School of Business.

Before the pandemic, only around 5% of the typical U.S. workforce worked from home; at the pandemic’s onset, it skyrocketed to 61.5%. Currently, about 30% of employees work from home.

“In some ways, one of the biggest lasting legacies of the pandemic will be the shift to work from home,” said Bloom.

Bloom shared his research on working from home at the Stanford Distinguished Careers Institute ’s “The Future of Work” Winter 2023 Colloquium, which focused on how the ways we work are changing.

DCI Director Richard Saller moderated the event , which featured scholars from Stanford and beyond discussing working arrangements and attitudes, challenges to office real estate, learned lessons about the power of proximity, and more.

Below are seven takeaways from Bloom’s discussion:

- The employees. About 58% of people in the U.S. can’t work from home at all, and they are typically frontline workers with lower pay. Those who work entirely from home are primarily professionals, managers, and in higher-paying fields such as IT support, payroll, and call centers. The highest paid group includes the 30% of people working from home in a hybrid capacity, and these include professionals and managers.

- The move. Almost 1 million people left city centers like New York and San Francisco during the pandemic. Those who used to go to the office five days a week are now willing to commute farther because they are only in the office a couple days a week, and they want larger homes to accommodate needs such as a home office. This has changed property markets substantially with rents and home values in the suburbs surging, Bloom said. Home values in city centers have risen but not by much.

- The commute. Public transit journeys have plummeted and are currently down by a third compared to pre-pandemic levels. This sharp reduction is threatening the survival of mass transit, Bloom said. These are systems that have relatively fixed costs because the hardware and labor, which is largely unionized, are relatively hard to adjust. A lot of the revenues come from ticket sales, and these agencies are losing a lot of money.

- The office. Offices are changing, with cubicles becoming less popular and meeting rooms more desirable. As some companies incorporate an organized hybrid schedule in which everyone comes in on certain days, they are redesigning spaces to support more meetings, presentations, trainings, lunches, and social time.

- The startups. Startup rates are surging, up by 20% from pre-pandemic numbers. The reasons: working from home provides a cheaper way to start a new company by saving a lot on initial capital and rent. Also, people can more easily work on a startup on the side when their regular job offers the option to work from home.

- The downtime. The number of people playing golf mid-week has more than doubled since 2019. People used to go before or after work, or on the weekends, but now the mid-day, mid-week golf game is becoming more common. The same is probably true for things like gyms, tennis courts, retail hairdressers, ski resorts, and anything else that consumers used to pack into the weekends.

- The organization. More and more, firms are outsourcing or offshoring their information technology, human resources, and finance to access talent, save costs, and free up space. There has been a big increase in part-time employees, independent contractors, and outsourcing. “After seeing how well it worked with remote work at the beginning of the pandemic, companies may not see a need to have employees in the country,” Bloom said.

Interested in hearing more about the future of work? Stanford Continuing Studies will feature Bloom as he discusses “The Future of and Impact of Working from Home” on May 1 as part of the Stanford Monday University web seminar series .

Bloom is also co-director of the Productivity, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship program at the National Bureau of Economic Research, a fellow at the Centre for Economic Performance, and a senior fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research .

EARLY BIRD PROMOTION: Register for the Masterclass by May 31 to secure lifetime(!) access. (Only 14 spots remaining)

The Business Case For Remote Work

Global Workplace Analytics published a comprehensive report on the benefits to employers, employees, the environment, and society. The findings are crystal clear: remote work is here to stay.

Learning from the pandemic

The report , titled 'The business case for remote work', draws from a wide range of research papers and surveys and provides an interesting insight into the potential benefits of sustained remote work.

Many like to make the conversation about remote work black or white— either everyone is in the office, or everyone is remote. This is both shortsighted and unwise.

Why? Because as with many things in life, beauty lies in the balance.

Consider this: Roughly 95 percent of U.S. office workers worked from their homes for three or more days a week during the pandemic. Ninety-five freaking percent. That’s basically one big test case that most everyone was forced to participate in, to an extent.

And guess what? 82 percent of the workers surveyed said they’d like to keep working remotely at least once per week after the pandemic is over. On the other hand, a slightly insignificant (and probably robotic) three percent said they’d rather forgo working remotely post-pandemic. Okay.

Anyway, at the same time, less than a fifth (19 percent) say they want to work fully remote. The majority prefer a mix of both. In the U.S., the preference averages out to be 2.5 days a week.

Why? Because they are fearful that a fully remote approach would likely lead to the erosion of the established work culture at that business. This notion seems a bit blah at first, but moving from fully on-premises to fully remote can actually make it more difficult for these companies to onboard new employees, make things harder for parents who have young children running all over the place and screaming at home, and even deprive young employees of the subtle mentorship and guidance that happens when they are physically around more experienced colleagues.

Luckily, remote work shouldn't be a problem for many. The benefits for those with remote-compatible jobs (45 percent) are omnipresent and can be summarized into three categories: those for employees, employers, and environment & society.

Employee benefits

Employees who can work remotely at least a few times a week—and actually want to—can preserve three valuable commodities: time, money, and their health.

1. More time

Aside from being liberated from the need to wear pants, the first thing most people think about when toying with the idea of working from home is the elimination of the daily commute—which is potentially a massive time-saver for many.

Think about it. U.S. workers spend the equivalent of 28 days a year commuting. Imagine spending the entire month of a non-leap year February stuck in a perpetual commute. Working remotely even half the time would shave off 14 of those days, leaving you with just a half of a February spent commuting.

Roughly 20 percent of non-remote workers have it even worse: their one-way commutes exceed an hour a day, equating to 60 days a year. Half-time remote work would lop off a full 30 days of being stuck in traffic, which most would surely take unless they have an inherent affinity for red lights, subways, and bus stops.

What would you do with an extra 14-30 days’ worth of hours each year? Well, you can do whatever you want, obviously, but it definitely won’t be spent in traffic.

2. More money

Yes, reducing the commute also means having more money in the bank.

By working from home half the time, a typical worker can save anywhere from $640 to $6,400 a year by reducing their spending on things like transportation, parking, gas, work clothes (and dry cleaning), food, and serendipity spending on stuff like gifts, impulsive lunchtime shopping, etc. Just whatever you spend by going into work, cut it in half in this scenario; that’s the point.

Oh, and these hypothetical figures account for increased utility bills and food at home, in case you were about to bust out a “well, actually” in response.

Depending on their situations, some workers could further reduce costs by:

- Selling their car

- Negotiating a new auto insurance premium (since they won’t be commuting as much)

- Moving to a different, less expensive area that’s not as close to their physical workplace

- Lowering any daycare, after-school, or eldercare costs

Whatever your work situation is, staying home half the time presents multiple opportunities to save some cash.

3. Better health

More remote work doesn't just bring in more time and money, it also benefits the health of employees.

Not that you need a study to really prove this, but long commutes have been linked to higher levels of stress (surprise), increased anxiety and depression, higher risks of heart issues like hypertension, increased obesity, and really just poor heart health in general. All of this, simply from long commutes.

Here are some stats gleaned from what surveyed remote workers say:

- 77% report having a better work/life balance between

- 69% report an improvement to their well-being—due to factors like more sleep and less stress

- 54% report eating healthier

- 48% report exercising more often

Employer benefits

The fact that employees benefit from policy change is, in most companies, not enough to actually make a change happen. However, when employers benefit from more money, more time, and more productivity, all of a sudden, an interest to change is sparked.

Luckily, for remote work, that's the case. So let’s discuss three of the most important ones.

1. Reduced office costs

Let's start with the three biggest reasons as to why company leaders enact change: money, money, money.

An employer that shells out $7,700 per employee, per year for their hallowed office space would save nearly $2k per half-time remote worker per year. How? By simply reducing their real estate footprint by a measly 25 percent for each half-time remote worker on staff. And as for the most expensive cities in the U.S.? The savings would increase by a factor of nearly five times that amount.

While there's some extra cost involved for giving stipends to purchase home office equipment, better tools, and stuff like that (around $666 per remote worker per year), there's still quite a lot to be saved.

So yes, it’s true that employers may implement remote work as a strategy to cut costs, but many see that the true value of remote work centers on human capital benefits.

You’re clearly intrigued, so let's look at some of those.

2. Increased productivity

Another one of those favorite yardsticks for success: productivity. Even in those terms, remote work gets shit done. Again, let’s turn to those who were surveyed:

- Remote workers said they gained an average of 35 working minutes a day due to fewer interruptions at their home (as opposed to constant interruptions at an office).

- Remote workers also reported voluntarily working an average of 47 percent of the time they would have otherwise spent stuck in their typical commute. That’s an additional seven days per year of good ‘ol productivity.

When considering these two factors, a half-time remote worker increases their productivity by the equivalent of 16 workdays a year.

Productivity, productivity, productivity. Every employer and C-suite type just loves increased productivity. And remote work increases it—which means they should love remote work.

Because productivity.

3. Reduced absenteeism

Here’s a fact: Most workers who call in sick are extremely not sick. Statistics show that nearly 70 percent of unplanned work absences are actually due to personal situations, family issues, stress, or being literally sick of work. Sick of work to the point of calling in sick to work.

That’s an astounding number. Depressing, even.

Fortunately, remote work reduces absenteeism because remote workers:

- Are not as exposed to sick coworkers who still come into work

- Limit their exposure to occupational and environmental risks

- Are still capable of working—even if they don’t feel well enough to physically show up at work

- Can handle personal appointments without the need to take the entire day or half-day off

- Lessen the stresses that come from commuting, interruptions, and all the standard office politics bullshit

- Tend to sleep better (and longer), eat healthier, and exercise more

Plenty of case studies have shown that the option to work remotely can reduce absenteeism anywhere from 26 percent to 88 percent. That’s actually kind of a hilarious window between two figures, but even the bottom number of 26 percent is a vast improvement.

When adding and subtracting some more numbers (details here ), the report concludes as follows:

"[A] typical U.S. employer can save $11,000 a year for each half-time (2 to 3 day a week) remote worker. That’s over $1M for every thousand employees!"

What's not to love?!

Environmental & societal benefits

But wait, there's more! We do, as they say, live in a society. Thankfully, the potential benefits of remote work for the environment—and society in general—are just as abundant.

Let’s examine a few. Remote work might help to:

- Decrease the risks stemming from human congestion

- Decrease wear and tear on a city’s transportation infrastructure

- Increase productivity among even non-remote workers by cutting down their travel times (and shortening their commutes)

- Reduce travel, even more, thanks to the widespread use of virtual-based tech

- Encourage a fuller, more robust employment for the disabled who can work from home

- Increase the standard of living in rural and economically disadvantaged areas

- Revitalize cities by reducing congestion and traffic and all the problems that come from them—such as dissuading visitors and tourists

- Make a bigger dent in the housing crisis by repurposing unneeded office spaces into residential buildings

We rest our case

The case is clear: let's make the option of remote work available to any and all remote-compatible jobs out there. All of the associated myths and concerns people had with the prospect of an increase of remote work has proven to be typical hysteria about nothing.

The bottom line is this: we can improve the lives of employees while benefiting employers. This is an actual thing that can happen and IS happening already. Oh, and don’t forget, both the environment and society benefit too. No big deal.

This is not hard. Everyone wins with remote work. Literally, everyone.

And with that, we rest our case.

Download: New Ways Of Working Guide

Unlock our in-depth guide spotlighting trends, tools, and best practices from over 150 pioneering organizations.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Download: Free Guide

Unlock our in-depth guide on trends, tools, and best practices from over 150 pioneering organizations.

Subscribe below and receive it directly in your inbox.

We respect your privacy. Unsubscribe at any time.

How working from home works out

Key takeaways.

- Forty-two percent of U.S. workers are now working from home full time, accounting for more than two-thirds of economic activity.

- Policymakers should ensure that broadband service is expanded so more workers can do their jobs away from a traditional office.

- As companies consider relocating from densely populated urban centers in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis, cities may suffer while suburbs and rural areas benefit.

- Working from home is here to stay, but post-pandemic will be optimal at about two days a week.

Working from home (WFH) is dominating our lives. If you haven’t experienced the phenomenon directly, you’ve undoubtedly heard all about it, as U.S. media coverage of working from home jumped 12,000 percent since January 1 .

But the trend toward working from home is nothing new. In 2014 I published a study of a Chinese travel company, Ctrip, that looked at the benefits of its WFH policies (Bloom et al. 2014). And in the past several months as the coronavirus pandemic has forced millions of workers to set up home offices, I have been advising dozens of firms and analyzing four large surveys covering working from home. 2

The recent work has highlighted several recurring themes, each of which carries policy questions — either for businesses or public officials. But the bottom line is clear: Working from home will be very much a part of our post-COVID economy. So the sooner policymakers and business leaders think of the implications of a home-based workforce, the better our firms and communities will be positioned when the pandemic subsides.

The US economy is now a working-from-home economy

Figure 1 shows the work status of 2,500 Americans my colleagues Jose Barrero (ITAM) and Steve Davis (Chicago) and I surveyed between May 21-25. The responders were between 20 and 64, had worked full time in 2019, and earned more than $20,000. The participants were weighted to represent the U.S. by state, industry, and income.

We find that 42 percent of the U.S. labor force are now working from home full time, while another 33 percent are not working — a testament to the savage impact of the lockdown recession. The remaining 26 percent are working on their business’s premises, primarily as essential service workers. Almost twice as many employees are working from home as at a workplace.

If we weight these employees by their earnings in 2019 as an indicator of their contribution to the country’s GDP, we see that these at-home workers now account for more than two-thirds of economic activity. In a matter of weeks, we have transformed into a working-from-home economy.

Although the pandemic has battered the economy to a point where we likely won’t see a return to trend until 2022 (Baker et al. 2020), things would have been far worse without the ability to work from home. Remote working has allowed us to maintain social distancing in our fight against COVID-19. So, working from home is a not only economically essential, it is a critical weapon in combating the pandemic.

Figure 1: WFH now accounts for over 60% of US economic activity

Source: Response to the question “Currently (this week) what is your work status?” Response options were “Working on my business premises“ , “Working from home” , “Still employed and paid, but not working“ , “Unemployed, but expect to be recalled to my previous job“ , “Unemployed, and do not expect to be recalled to my previous job“ , and “Not working, and not looking for work“

Data from a survey of 2,500 US residents aged 20 to 64, earning more than $20,000 per year in 2019 carried out between May 21-29, by QuestionPro on behalf of Stanford University. Sample reweighted to match current CPS.

Shares shown weighted by earnings and unweighted (share of workers)

The inequality time bomb

But it is important to understand the potential downsides of a WFH economy and take steps to mitigate them.

Figure 2 shows not everyone can work from home. Only 51 percent of our survey reported being able to WFH at an efficiency rate of 80 percent or more. These are mostly managers, professionals, and financial workers who can easily carry out their jobs on their computers by videoconference, phone, and email.

The remaining half of Americans don’t benefit from those technological workarounds — many employees in retail, health care, transportation, and business services cannot do their jobs anywhere other than a traditional workplace. They need to see customers or work with products or equipment. As such they face a nasty choice between enduring greater health risks by going to work or forgoing earnings and experience by staying at home.

Figure 2: Not all jobs can be carried out WFH

Source: Data from a survey of 2,500 US residents aged 20 to 64, earning more than $20,000 per year in 2019 carried out between May 21-25 2020, by QuestionPro on behalf of Stanford University. Sample reweighted to match the Current Population Survey.

In Figure 3 we see that many Americans also lack the facilities to effectively work from home. Only 49 percent of responders can work privately in a room other than their bedroom. The figure displays another big challenge — online connectivity. Internet connectivity for video calls has to be 90 percent or greater, which only two-thirds of those surveyed reported having. The remaining third have such poor internet service that it prevents them effectively working from home.

Figure 3: WFH under COVID-19 is challenging for many employees

Source: Pre-COVID data from the BLS ATUS . During COVID data from a survey of 2,500 US residents aged 20 to 64, earning more than $20,000 per year in 2019 carried out between May 21-25 2020, by QuestionPro on behalf of Stanford University. Sample reweighted to match the Current Population Survey.

In Figure 4, we see that more educated, higher-earning employees are far more likely to work from home. These employees continue to earn, develop skills, and advance careers. Those unable to work from home — either because of the nature of their jobs or because they lack suitable space or internet connections — are being left behind. They face bleak prospects if their skills erode during the shutdown.

Taken together, these findings point to a ticking inequality time bomb.

So as we move forward to restart the U.S. economy, investing in broadband expansion should be a major priority. During the last Great Depression, the U.S. government launched one of the great infrastructure projects in American history when it approved the Rural Electrification Act in 1936. Over the following 25 years, access to electricity by rural Americans increased from just 10 percent to nearly 100 percent. The long-term benefits included higher rates of growth in employment, population, income, and property values.

Today, as policymakers consider how to focus stimulus spending to revive growth, a significant increase in broadband spending is crucial to ensuring that all of the United States has a fair chance to bounce back from COVID-19.

Figure 4: WFH is much more common among educated higher-income employees

Source: Pre-COVID data from the BLS ATUS . During COVID data from a survey of 2,500 US residents aged 20 to 64, earning more than $20,000 per year in 2019 carried out between May 21-25 2020, by QuestionPro on behalf of Stanford University. Sample reweighted to match the Current Population Survey. We code a respondent as working from home pre-COVID if they report working from home one day per week or more.

Trouble for the cities?

Understanding the lasting impacts of working from home in a post-COVID world requires taking a look back at the pre-pandemic work world. Back when people went to work, they typically commuted to offices in the center of cities. Our survey showed 58 percent of those who are now working from home had worked in a city before the coronavirus shutdown. And 61 percent of respondents said they worked in an office.

Since these employees also tend to be well paid, I estimate this could remove from city centers up to 50 percent of total daily spending in bars, restaurants, and shops. This is already having a depressing impact on the vitality of the downtowns of our major cities. And, as I argue below, this upsurge in working from home is largely here to stay. So I see a longer-run decline in city centers.

The largest American cities have seen incredible growth since the 1980s as younger, educated Americans have flocked into revitalized downtowns (Glaeser 2011). But it looks like 2020 will reverse that trend, with a flight of economic activity from city centers.

Of course, the upside is this will be a boom for suburbs and rural areas.

Working from home is here to stay

Working from home is a play in three parts, each totally different from the other. The first part is pre -COVID. This was an era in which working from home was both rare and stigmatized.

A survey of 10,000 salaried workers conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics showed only 15 percent of employees ever had a full day working from home. 3

Indeed, only 2 percent of workers ever worked from home full time. From talking to dozens of remote employees for my research projects over the years, I found these are mostly either lower-skilled data entry or tele-sales workers or higher-skilled employees who were able to do their jobs largely online and had often been able to keep a job despite locating to a new area.

Working from home before the pandemic was also hugely stigmatized — often mocked and ridiculed as “shirking from home” or “working remotely, remotely working.”

In a 2017 TEDx Talk , I showed the result from an online image search for the words “working from home” which pulled up hundreds of negative images of cartoons, semi-naked people or parents holding a laptop in one hand and a baby in the other.

Working from home during the pandemic is very different. It is now extremely common, without the stigma, but under challenging conditions . Many workers have kids at home with them. There’s a lack of quiet space, a lack of choice over having to work from home, and no option other than to do this full time. Having four kids myself I have definitely experienced this.

COVID has forced many of us to work from home under the worst circumstances.

But working from home post- COVID should be what we look forward to. Of the dozens of firms I have talked to, the typical plan is that employees will work from home between one and three days a week and come into the office the rest of the time. This is supported by our evidence on about 1,000 firms from the Survey of Business Uncertainty I run with the Atlanta Fed and the University of Chicago. 4

Before COVID, 5 percent of working days were spent at home. During the pandemic, this increased eightfold to 40 percent a day. And post-pandemic, the number will likely drop to 20 percent.

But that 20 percent still represents a fourfold increase of the pre-COVID level, highlighting that working from home is here to stay. While few firms are planning to continue full time WFH after the pandemic ends, nearly every firm I have talked to about this has been positively surprised by how well it has worked.

The office will survive but it may look different

“Should we get rid of our office?” I get that question a lot.

The answer is “No. But you might want to move it.”

Although firms plan to reduce the time their employees spend at work, this will not reduce the demand for total office space given the need for social distancing. The firms I talk to are typically thinking about halving the density of offices, which is leading to an increase in the overall demand for office space. That is, the 15 percent drop in working days in the office is more than offset by the 50 percent increase in demand for space per employee.

What is happening, however, is offices are moving from skyscrapers to industrial parks. Another dominant theme of the last 40 years of American cities was the shift of office space into high-rise buildings in city centers. COVID is dramatically reversing this trend as high rises face two massive problems in a post-COVID world.

Just consider mass transit and elevators in a time of mandatory social distancing. How can you get several million workers in and out of major cities like New York, London, or Tokyo every day keeping everyone six feet apart? And think of the last elevator you were in. If we strictly enforce six feet of social distancing, the maximum capacity of elevators could fall by 90 percent 5 , making it impossible for employees working in a skyscraper to expediently reach their desks.

Of course, if social distancing disappears post-COVID, this may not matter. But given all the uncertainty, my prediction is that when a vaccine eventually comes out in a year or so, society will have become accustomed to social distancing. And given recent nearly missed pandemics like SARS, Ebola, MERS, and avian flu, many firms and employees may be preparing for another outbreak and another need for social distancing. So my guess is many firms will be reluctant to return to dense offices.

So what is the solution? Firms may be wise to turn their attention from downtown buildings to industrial park offices, or “campuses,” as hi-tech companies in Silicon Valley like to call them. These have the huge benefits of ample parking for all employees and spacious low-rise buildings that are accessible by stairs.

Two types of policies can be explored to address this challenge. First, towns and cities should be flexible on zoning, allowing struggling shopping malls, cinemas, gyms, and hotels to be converted into offices. These are almost all low-rise structures with ample parking, perfect for office development.

Second, we need to think more like economists by introducing airline-style pricing for mass transit and elevators. The challenges with social distancing arise during peak capacity, so we need to cut peak loads.

For public transportation this means steeply increasing peak-time fares and cutting off-peak fares to encourage riders to spread out through the day.

For elevator rides we need to think more radically. For example, office rents per square foot could be cut by 50 percent, but elevator use could be charged heavily during the morning and evening rush hours. Charging firms, say $10 per elevator ride between 8:45 a.m. and 9:15 a.m. and 4:45 p.m. and 5:15 p.m., would encourage firms to stagger their working days. This would move elevator traffic to off-peak periods with excess capacity. We are moving from a world where office space is in short supply to one where elevator space is in short supply, and commercial landlords should consider charging their clients accordingly.

Making a smooth transition

From all my conversations and research, I have three pieces of advice for anyone crafting WFH policies.

First, working from home should be part time.

Full-time working from home is problematic for three reasons: It is hard to be creative at a distance, it is hard to be inspired and motivated at home, and employee loyalty is strained without social interaction.

My experiment at Ctrip in China followed 250 employees working from home for four days a week for nine months and saw the challenges of isolation and loneliness this created.

For the first three months employees were happy — it was the euphoric honeymoon period. But by the time the experiment had run its full length, two-thirds of the employees requested to return to the office. They needed human company.

Currently, we are in a similar honeymoon phase of full-time WFH. But as with any relationship, things can get rocky and I see increasing numbers of firms and employees turning against this practice.

So the best advice is plan to work from home about 1 to 3 days a week. It’ll ease the stress of commuting, allow for employees to use their at-home days for quiet, thoughtful work, and let them use their in-office days for meetings and collaborations.

Second, working from home should be optional.

Figure 5 shows the choice of how many days per week our survey of 2,500 American workers preferred. While the median responder wants to work from home two days a week, there is a striking range of views. A full 20 percent of workers never want to do it while another 25 percent want to do it full time.

The remaining 55 percent all want some mix of office and home time. I saw similarly large variations in views in my China experiment, which often changed over time. Employees would try WFH and then discover after a few months it was too lonely or fell victim to one of the three enemies of the practice — the fridge, the bed, and the television — and would decide to return to the office.

So the simple advice is to let employees choose, within limits. Nobody should be forced to work from home full time, and nobody should be forced to work in the office full time. Choice is key — let employees pick their schedules and let them change as their views evolve. The two exceptions are new hires, for whom maybe one or two years full time in the office makes sense, and under-performers, who are the subject of my final tip.

Third, working from home is a privilege, not an entitlement.

For WFH to succeed, it is essential to have an effective performance review system. If you can evaluate employees based on output — what they accomplish — they can easily work from home. If they are effective and productive, great; if not, warn them, and if they continue to underperform, haul them back to the office.

This of course requires effective performance management. In firms that do not have effective employee appraisal systems management, I would caution against working from home. This was the lesson of Yahoo in 2013 . When Marissa Mayer took over, she found there was an ineffective employee evaluation system and working from home was hard to manage. So WFH was paused while Mayer revamped Yahoo’s employee performance evaluation.

The COVID pandemic has challenged and changed our relationships with work and how many of us do our jobs. There’s no real going back, and that means policymakers and business leaders need to plan and prepare so workers and firms are not sidelined by otherwise avoidable problems. With a thoughtful approach to a post-pandemic world, working from home can be a change for good.

Figure 5: There is wide variation in employee demand for WFH post-COVID

Source: Response to the questions: “In 2021+ (after COVID) how often would you like to have paid work days at home?“

Data from a survey of 2,500 US residents aged 20 to 64, earning more than $20,000 per year in 2019 carried out between May 21-25, by QuestionPro on behalf of Stanford University.

Sample reweighted to match the Current Population Survey.

1 Newsbank Access World News collection of approximately 2,000 national and local daily U.S. newspapers showing the percentage of articles mentioning “working from home” or “WFH.”

2 These are the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics American Time Use Survey ; the Survey of Business Uncertainty ; the Bank of England Decision Maker Panel ; and the survey I conducted of 2,500 U.S. employees.

3 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Job Flexibilities and Work Schedules News Release. Sept. 24, 2019 .

4 Firms Expect Working from Home to Triple. May 28, 2020. Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta .

5 In a packed elevator each person requires about four square feet. With six-foot spacing we need a circle of radius six-feet around each person, which is over 100 square feet. If an elevator is large enough to fit more than one person, experts have advised riders to stand in your corner, face the walls and carry toothpicks (for pushing the buttons), as explained in this NPR report .

Baker, S.R., Bloom, N., Davis, S.J., Terry, S.J. (2020). COVID-Induced Economic Uncertainty (No. 26983). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Bloom, N., Liang, J., Roberts, J., Zhichun, J.Y. (2014). Does Working from Home Work? Evidence from a Chinese Experiment. Quarterly Journal of Economics.

Glaeser, E. (2011). Triumph of the City: How Our Greatest Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier and Happier. Penguin Books.

Related Topics

- Policy Brief

More Publications

Economic analysis of law, are ideas getting harder to find, do energy rebate programs encourage conservation.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Wolters Kluwer - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Work From Home During the COVID-19 Outbreak

The COVID-19 pandemic made working from home (WFH) the new way of working. This study investigates the impact that family-work conflict, social isolation, distracting environment, job autonomy, and self-leadership have on employees’ productivity, work engagement, and stress experienced when WFH during the pandemic.

This cross-sectional study analyzed data collected through an online questionnaire completed by 209 employees WFH during the pandemic. The assumptions were tested using hierarchical linear regression.

Employees’ family-work conflict and social isolation were negatively related, while self-leadership and autonomy were positively related, to WFH productivity and WFH engagement. Family-work conflict and social isolation were negatively related to WFH stress, which was not affected by autonomy and self-leadership.

Conclusion:

Individual- and work-related aspects both hinder and facilitate WFH during the COVID-19 outbreak.

The COVID-19 outbreak has made working from home (WFH) the new way of working for millions of employees in the EU and around the world. Due to the pandemic, many workers and employers had to switch, quite suddenly, to remote work for the first time and without any preparation. Early estimates from Eurofound 1 suggested that due to the pandemic, approximately 50% of Europeans worked from home (at least partially) as compared with 12% prior to the emergency. Currently, these numbers are approximately the same, with many employees and organizations possibly opting for WFH even after the pandemic. 2

To contain the spread of the virus, Italy quickly adopted home confinement measures which, since the Spring of 2020, were renewed for several months and are still, as in some other European countries, ongoing also during Spring 2021.

As all organizational changes, WFH too has some advantages and disadvantages. 3 Usually, adopting this flexible way of working has been presented as a planned choice that requires a period of design, preparation, and adaptation to allow organizations to effectively support employees’ productivity and ensure them better work-life balance. 4 – 6 However, the COVID-19 outbreak has substantially forced most organizations to adopt this way of working, often without providing employees with the necessary skills required for remote work. 7 – 9 As previously mentioned, studies have reported both advantages and disadvantages related to remote work. 10 Its effects, therefore, have been quite explored. 6 On the other side, the need to examine how WFH, as a “new way of working,” 11 , 12 has affected the well-being and productivity of employees with no prior remote work experience and to identify specific work conditions affecting remote work during the COVID-19 crisis 9 is imperative.

To achieve these goals, the present study considered the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model 13 , 14 as a theoretical framework. The JD-R model is a well-established theoretical model in the field of occupational health psychology, which suggests that work conditions, categorized into job demands and job resources, affect employees’ wellbeing and performance. Job demands refer to the physical, psychological, or socio-organizational aspects of the work whose energy-depleting process induces people to experience energy loss and fatigue, leading to stress, burnout, and health impairment. On the contrary, job resources refer to the physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job that reduce job demands while stimulating work motivation, personal growth, and development. 15 In addition, personal resources have been introduced in the JD-R model defining them as “aspects of the self that are generally linked to resilience and refer to individuals’ sense of their ability to control and impact upon their environment successfully,” 16 thus stimulating optimal functioning and lessening stress.