Library subject guides

- Key resources

- Books and e-books

- Statistics and country information

Case studies

Recommended databases: case studies, other databases: case studies, streaming videos: case studies.

- Company and industry information, financials

- Additional information

Case studies describe real world practical examples, including successes, issues and challenges. To find case studies using LibrarySearch or databases, add "case study" to your search terms.

- The case study handbook a student's guide This e-book provides tips on how to read, analyse and write about cases.

- Business source complete (EBSCO) Contains case studies from many sources. They can be found using advanced search and selecting "case study" as the Document Type.

- Harvard Business Review Journal of Harvard Business School that covers a wide range of business topics. Click “Search within this publication” and input search terms, then limit results by “Subject” to “Case studies”.

- Harvard Business Review Digital Articles Digital articles uploaded from the HBR.org site. Click “Search within this publication” and add “Case study” as a search term.

- Henry Stewart talks: The business and management collection A collection of video lectures, case studies and seminar-style talks. Subject areas include marketing & sale, global business management, organisation, commerce, technology, and operations.

- Emerald Insight An extensive business research database. Click on advanced search and then select the case studies checkbox.

- MarketLine Case Studies (Datamonitor) Explore business practices across a variety of industry sectors. Select "Analysis" from the menu bar and select Case studies. A selection of pre 2008/9 reports are also available from LibrarySearch; search for "Datamonitor Case Studies”.

- Factiva Use "case study" or "case studies" as terms when building your search. There is no option to limit to case studies as a resource type.

- SAGE Business cases Access to authoritative cases from over 100 countries. SAGE curates interdisciplinary cases on in-demand subjects such as marketing, entrepreneurship, accounting, healthcare management, leadership, social enterprise, and more.

- Arthur Andersen Case Studies in Business Ethics 90 case studies that highlight awareness of ethical issues in business.

- Business Case Studies Uses real information and issues from featured companies.

- Markkula Center for Applied Ethics - ethics case studies Find case studies and scenarios on a variety of fields in applied ethics.

- MIT LearningEdge Case Studies Some of the case studies featured on LearningEdge highlight the decision-making process in a business or management setting.

Case studies in video documentary format are available from these video streaming databases.

- ClickView A collection of educational videos, including professional development videos and case studies. To access you will need to use your RMIT student login. Streaming videos covering a variety of disciplines. Enter your search terms and then narrow using the “case study” Tag.

- Alexander Street A collection of documentaries, features, educational and informative videos (and audio), and archival material. Also includes industry specific textbooks, book chapters, corporate training videos, case studies and executive-oriented research reports. Enter your search terms and then filter your result by selecting “Case Study” as your Content Type.

- Kanopy Business Case Studies A selection of streaming videos examining companies, marketing strategies, and entrepreneurs. Browse the “Business” section and select “Business Case Studies”.

Finding case studies

The Library's Finding Case Studies guide explains different types of case studies and how to find them.

Writing a case study

See the Learning Lab tutorial on Writing a Case Study to find out how to read, analyse and respond to a case study.

- << Previous: Videos

- Next: Company and industry information, financials >>

- Last Updated: Apr 27, 2024 5:48 AM

- URL: https://rmit.libguides.com/economics

Home > Case Studies

Case Studies

Discover all the ways our 2,000 customers succeed, thrive and grow with Oxford Economics. Read success stories from Oxford Economics' clients in sectors such as pensions, energy and Real Estate. Learn how they solved their business challenges, supported their businesses' growth and adapted to new markets using Oxford Economics market-leading consulting and subscription services.

Case Study | Multinational Drinks Company

Bespoke dashboards and agile on-demand economics support

Background Today’s turbulent macroeconomic and consumer environment makes strategy and planning particularly difficult for firms in the business-to-consumer sector. The pandemic, major global conflicts and geopolitical tensions have caused major supply-side disruptions. At the same time, the ever-changing consumer environment, recent unprecedented levels of inflation and the ensuing cost of living crisis have been a...

Case Study | Royal London

Exploring the implications of higher pension contributions

Many households fail to save adequately for retirement. Using in-house models, the study assesses the impact of higher pension contributions on both pension savings and UK economic growth.

Case Study | A global aggregate and building materials provider

Constructing Success by Capitalising on Long-Term Opportunities

Helping a strategy department identify its 10-year growth opportunities

Case Study | Semiconductor Industry Association

A unique policy-driven impact scenario for CHIPS Act

How Oxford Economics engaged the world’s largest chip manufacturers to develop an industry-wide impact assessment of the CHIPS and Sciences Act.

Case Study | Building material manufacturer

Benchmarking Success: Building a Global Market Demand Indicator

Creating a new demand measure to enable a building material manufacturer to gauge its performance.

Case Study | Multinational services company

Quantifying the impact of climate on customers

Leveraging industry-specific climate forecasts to future-proof revenue.

Case Study | Energy UK

Achieving net zero advocacy goals

Highlighting the economic opportunities the energy transition presents and the consequences of not grasping them.

Charting a course for global growth in the shipping industry

Empowering a leading shipping company to enhance its strategic planning and identify new routes for growth

Global macroeconomic and risk scenario tool

Enabling a major automotive manufacturer to anticipate and respond effectively to evolving market dynamics across its global operations.

Risk signal identification, prioritisation and monitoring evaluation model

Despite existing internal risk management processes, a major automotive manufacturer was unprepared for and failed to anticipate and mitigate significant risks and shocks that have significantly affected its operations in recent years, including its sales, supply chain and financing.

Bespoke automotive sector sales forecasting

Automotive companies face many challenges: regulations, emission controls, litigation, political uncertainty, complex and problematic supply chains and disruptive technology are perhaps among the most pressing.

Case Study | Australian Finance Industry Association

The economic impact of Buy Now Pay Later in Australia

Governments globally are realising the importance of payments and financial services efficiency to economic growth, financial wellbeing and social participation. The Australian Finance Industry Association (AFIA) recognises innovation, competition, market efficiency, economic growth and consumer protection are interrelated and, therefore, must be addressed collectively. An informed understanding of the Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL) sector...

Case Study | City of Sydney

City of Sydney’s 2022 Business Needs Survey Report

The City of Sydney required an advisor with the capability to develop a high-impact, user-focused report to: The report had to be engaging and highly visual, containing a range of different devices to communicate economic insights to a range of readers. The solution Oxford Economics Australia developed a rich and compelling report to engage and...

Case Study | Leading Australian Law Firm

Expert Witness Report on property market influences and outlook

The repudiation of an existing development agreement resulted in Supreme Court proceedings whereby residential property market forecasts were required to demonstrate the outlook for the Darwin residential market at that time. Separate sale price and rent projections were needed (on an annual basis) for detached house and attached dwellings for the period of 2017-2030. Importantly,...

Case Study | QBE LMI

The Annual Housing Outlook 2022 – the Green Edition

The objective of this work was to reinforce QBE LMI’s position by providing an outlook of housing market performance and stimulate informed discussion about environmental sustainability within the housing market and a state by state performance analysis of housing market prices and rents. The solution The project was approached collaboratively with the QBE LMI project...

Case Study | Australia Energy Market

Forecasts and scenarios to inform the future of Australia’s energy market

Oxford Economics Australia was commissioned to produce macroeconomic and commodity scenario projections that could be used to generate long-term gas and electricity demand and supply projections across a range of energy transition scenarios. The solution We worked closely with the client’s team and their stakeholders to produce long-term (30-year) macroeconomic and commodity price forecasts, across...

Case Study | National Bureau of Statistics

Developing a leading statistical ecosystem to empower decision makers in government, the private sector and broader society

The National Bureau of Statistics asked Oxford Economics to redesign its existing statistical publications to make them more user-focused. This included: The solution Oxford Economics worked closely with the National Bureau of Statistics over a period of six months to develop 57 redesigned publication templates. The work was completed in two broad stages: The final...

Case Study | Schroders

Understanding climate-related implications on investment strategies

As global awareness of climate change continues to increase, investors are beginning to consider how climate risks and opportunities may affect long-term investment strategies and returns. Our client, Schroders, a large asset manager, is no exception, which is why they switched to our Global Climate Service as the economic foundation for their long-run asset class publication.

Case Study | Life insurance company

Improved research processes and forecasting accuracy

A leading life insurance company has used Oxford Economics' Global Economic Model to improve their global economic research processes and increase the accuracy of their own economic forecasts.

Case Study | Large global pension fund

Supporting investment strategy with long-term perspectives

Overview To make long-term investments, investors need long-term thinking. That’s why one of the largest pension funds globally subscribed to Oxford Economics’ Global Macro Service, Global Cities Service and Regional City Services. They currently use our macroeconomic forecasts as one of the references in reviewing market fundamentals for investment. The Challenge As long-term investors, our...

Find out how Oxford Economics can help you on your path to business growth

Sign up to our Resource Hub to download the latest and most popular reports.

Select to close video modal

Select to close video modal Play Video Select to play video

Suggestions or feedback?

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Machine learning

- Social justice

- Black holes

- Classes and programs

Departments

- Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Brain and Cognitive Sciences

- Architecture

- Political Science

- Mechanical Engineering

Centers, Labs, & Programs

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

- Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

- Lincoln Laboratory

- School of Architecture + Planning

- School of Engineering

- School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

- Sloan School of Management

- School of Science

- MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

The case for economics — by the numbers

Press contact :, media download.

*Terms of Use:

Images for download on the MIT News office website are made available to non-commercial entities, press and the general public under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives license . You may not alter the images provided, other than to crop them to size. A credit line must be used when reproducing images; if one is not provided below, credit the images to "MIT."

Previous image Next image

In recent years, criticism has been levelled at economics for being insular and unconcerned about real-world problems. But a new study led by MIT scholars finds the field increasingly overlaps with the work of other disciplines, and, in a related development, has become more empirical and data-driven, while producing less work of pure theory.

The study examines 140,000 economics papers published over a 45-year span, from 1970 to 2015, tallying the “extramural” citations that economics papers received in 16 other academic fields — ranging from other social sciences such as sociology to medicine and public health. In seven of those fields, economics is the social science most likely to be cited, and it is virtually tied for first in citations in another two disciplines.

In psychology journals, for instance, citations of economics papers have more than doubled since 2000. Public health papers now cite economics work twice as often as they did 10 years ago, and citations of economics research in fields from operations research to computer science have risen sharply as well.

While citations of economics papers in the field of finance have risen slightly in the last two decades, that rate of growth is no higher than it is in many other fields, and the overall interaction between economics and finance has not changed much. That suggests economics has not been unusually oriented toward finance issues — as some critics have claimed since the banking-sector crash of 2007-2008. And the study’s authors contend that as economics becomes more empirical, it is less dogmatic.

“If you ask me, economics has never been better,” says Josh Angrist, an MIT economist who led the study. “It’s never been more useful. It’s never been more scientific and more evidence-based.”

Indeed, the proportion of economics papers based on empirical work — as opposed to theory or methodology — cited in top journals within the field has risen by roughly 20 percentage points since 1990.

The paper, “Inside Job or Deep Impact? Extramural Citations and the Influence of Economic Scholarship,” appears in this month’s issue of the Journal of Economic Literature .

The co-authors are Angrist, who is the Ford Professor of Economics in MIT Department of Economics; Pierre Azoulay, the International Programs Professor of Management at the MIT Sloan School of Management; Glenn Ellison, the Gregory K. Palm Professor Economics and associate head of the Department of Economics; Ryan Hill, a doctoral candidate in MIT’s Department of Economics; and Susan Feng Lu, an associate professor of management in Purdue University’s Krannert School of Management.

Taking critics seriously

As Angrist acknowledges, one impetus for the study was the wave of criticism the economics profession has faced over the last decade, after the banking crisis and the “Great Recession” of 2008-2009, which included the finance-sector crash of 2008. The paper’s title alludes to the film “Inside Job” — whose thesis holds that, as Angrist puts it, “economics scholarship as an academic enterprise was captured somehow by finance, and that academic economists should therefore be blamed for the Great Recession.”

To conduct the study, the researchers used the Web of Science, a comprehensive bibliographic database, to examine citations between 1970 and 2015. The scholars developed machine-learning techniques to classify economics papers into subfields (such as macroeconomics or industrial organization) and by research “style” — meaning whether papers are primarily concerned with economic theory, empirical analysis, or econometric methods.

“We did a lot of fine-tuning of that,” says Hill, noting that for a study of this size, a machine-learning approach is a necessity.

The study also details the relationship between economics and four additional social science disciplines: anthropology, political science, psychology, and sociology. Among these, political science has overtaken sociology as the discipline most engaged with economics. Psychology papers now cite economics research about as often as they cite works of sociology.

The new intellectual connectivity between economics and psychology appears to be a product of the growth of behavioral economics, which examines the irrational, short-sighted financial decision-making of individuals — a different paradigm than the assumptions about rational decision-making found in neoclassical economics. During the study’s entire time period, one of the economics papers cited most often by other disciplines is the classic article “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk,” by behavioral economists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky.

Beyond the social sciences, other academic disciplines for which the researchers studied the influence of economics include four classic business fields — accounting, finance, management, and marketing — as well as computer science, mathematics, medicine, operations research, physics, public health, and statistics.

The researchers believe these “extramural” citations of economics are a good indicator of economics’ scientific value and relevance.

“Economics is getting more citations from computer science and sociology, political science, and psychology, but we also see fields like public health and medicine starting to cite economics papers,” Angrist says. “The empirical share of the economics publication output is growing. That’s a fairly marked change. But even more dramatic is the proportion of citations that flow to empirical work.”

Ellison emphasizes that because other disciplines are citing empirical economics more often, it shows that the growth of empirical research in economics is not just a self-reinforcing change, in which scholars chase trendy ideas. Instead, he notes, economists are producing broadly useful empirical research.

“Political scientists would feel totally free to ignore what economists were writing if what economists were writing today wasn’t of interest to them,” Ellison says. “But we’ve had this big shift in what we do, and other disciplines are showing their interest.”

It may also be that the empirical methods used in economics now more closely match those in other disciplines as well.

“What’s new is that economics is producing more accessible empirical work,” Hill says. “Our methods are becoming more similar … through randomized controlled trials, lab experiments, and other experimental approaches.”

But as the scholars note, there are exceptions to the general pattern in which greater empiricism in economics corresponds to greater interest from other fields. Computer science and operations research papers, which increasingly cite economists’ research, are mostly interested in the theory side of economics. And the growing overlap between psychology and economics involves a mix of theory and data-driven work.

In a big country

Angrist says he hopes the paper will help journalists and the general public appreciate how varied economics research is.

“To talk about economics is sort of like talking about [the United States of] America,” Angrist says. “America is a big, diverse country, and economics scholarship is a big, diverse enterprise, with many fields.”

He adds: “I think economics is incredibly eclectic.”

Ellison emphasizes this point as well, observing that the sheer breadth of the discipline gives economics the ability to have an impact in so many other fields.

“It really seems to be the diversity of economics that makes it do well in influencing other fields,” Ellison says. “Operations research, computer science, and psychology are paying a lot of attention to economic theory. Sociologists are paying a lot of attention to labor economics, marketing and management are paying attention to industrial organization, statisticians are paying attention to econometrics, and the public health people are paying attention to health economics. Just about everything in economics is influential somewhere.”

For his part, Angrist notes that he is a biased observer: He is a dedicated empiricist and a leading practitioner of research that uses quasiexperimental methods. His studies leverage circumstances in which, say, policy changes random assignments in civic life allow researchers to study two otherwise similar groups of people separated by one thing, such as access to health care.

Angrist was also a graduate-school advisor of Esther Duflo PhD ’99, who won the Nobel Prize in economics last fall, along with MIT’s Abhijit Banerjee — and Duflo thanked Angrist at their Nobel press conference, citing his methodological influence on her work. Duflo and Banerjee, as co-founders of MIT’s Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL), are advocates of using field experiments in economics, which is still another way of producing empirical results with policy implications.

“More and more of our empirical work is worth paying attention to, and people do increasingly pay attention to it,” Angrist says. “At the same time, economists are much less inward-looking than they used to be.”

Share this news article on:

Related links.

- Paper: “Inside Job or Deep Impact? Extramural Citations and the Influence of Economic Scholarship”

- Josh Angrist

- Glenn Ellison

- Pierre Azoulay

- Department of Economics

- Article: “The Natural Experimenter”

Related Topics

- MIT Sloan School of Management

- School of Humanities Arts and Social Sciences

- History of science

- Social sciences

Related Articles

MIT economists Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee win Nobel Prize

2019 MacVicar Faculty Fellows named

New science blooms after star researchers die, study finds

The “metrics” system

Previous item Next item

More MIT News

Exploring the history of data-driven arguments in public life

Read full story →

Three from MIT awarded 2024 Guggenheim Fellowships

A musical life: Carlos Prieto ’59 in conversation and concert

Two from MIT awarded 2024 Paul and Daisy Soros Fellowships for New Americans

MIT Emerging Talent opens pathways for underserved global learners

The MIT Edgerton Center’s third annual showcase dazzles onlookers

- More news on MIT News homepage →

Massachusetts Institute of Technology 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA, USA

- Map (opens in new window)

- Events (opens in new window)

- People (opens in new window)

- Careers (opens in new window)

- Accessibility

- Social Media Hub

- MIT on Facebook

- MIT on YouTube

- MIT on Instagram

Examiner and Judge Designs in Economics: A Practitioner's Guide

This article provides empirical researchers with an introduction and guide to research designs based on variation in judge and examiner tendencies to administer treatments or other interventions. We review the basic theory behind the research design, outline the assumptions under which the design identifies causal effects, describe empirical tests of those assumptions, and discuss tradeoffs associated with choices researchers must make for estimation. We demonstrate concepts and best practices concretely in an empirical case study that uses an examiner tendency research design to study the effects of pre-trial detention.

This manuscript is in preparation for the Journal of Economic Literature. Programs and data for the empirical case study will be provided online. We are grateful for insightful comments from David Romer and four anonymous referees. In addition, we received constructive feedback from Amanda Agan, Elior Cohen, Rob Collinson, Jason Cook, Gordon Dahl, John Eric Humphries, Lawrence Katz, Magne Mogstad, Samuel Norris, Aurelie Ouss, Roman Rivera, Henrik Sigstad, Kamelia Stavreva, Megan Stevenson, and Winnie van Dijk. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

MARC RIS BibTeΧ

Download Citation Data

More from NBER

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

The case method can be a powerful tool to teach economic concepts and frameworks. Topics in this section cover a wide range of real-life examples from around the world on a host of issues including infrastructure, trade, taxation, regulation and development.

Integrating Systems at Scale: Coordinating Health Care in Houston

Publication Date: November 8, 2023

This case concerns the Patient Care Intervention Center (PCIC) a values-based health technology social enterprise in Houston, Texas. This organization was founded to tackle fundamental problems in social and health services in the United...

A User-Centered Design Process for Data-Driven Policymaking

Publication Date: August 22, 2023

Well-conceived, user-friendly data visualizations have the potential to bring fresh perspectives derived from analyzing, visualizing, and presenting data to inform evidence-based policymaking. This case uses the Metroverse project from the...

Leadership and Negotiation: Ending the Western Hemisphere’s Longest Running Border Conflict

Publication Date: October 4, 2022

For centuries, Ecuador and Peru each claimed sovereignty over a historically significant, but sparsely inhabited tract of borderland in the Amazonian highlands. The heavily disputed area had led the two nations to war—or the brink of...

Pratham: The Challenge of Converting Schooling to Learning in India

Publication Date: November 18, 2020

This multimedia case brings video, text, and graphics together to offer a rare, immersive experience inside one of the developing world's most pressing challenges, low levels of learning. Pratham, counted among India's largest non-profits, has...

Video Series: Public Policy Applications of Microeconomic Concepts

Publication Date: September 24, 2019

MATERIALS FOR VIDEO CASEThe materials for this case are included in the teaching plan and are for registered instructors to use in class. If you do not have Educator Access, please register here (notification received within 2 business days). Abstract:...

Evaluating the Impact of Solar Lamps in Uganda

Publication Date: August 26, 2019

IDinsight, an evaluation company founded by graduates of the Harvard Kennedy School, designs and conducts evaluations that best suit the needs of clients across the developing world, offering timely and rigorous evidence to help decision making...

Untapped Potential: Renewable Energy in Argentina (Sequel)

Publication Date: October 6, 2020

In 2015, Mauricio Macri became President of Argentina and declared solving the energy crisis one of his top priorities. When Macri attempted to raise utility tariffs, however, he faced loud protests from citizens. In search of solutions to...

Untapped Potential: Renewable Energy in Argentina

Publication Date: August 23, 2019

Christine Lagarde (C): Managing the IMF

Publication Date: August 20, 2018

This case covers the career of Christine Lagarde from 2011 to 2018 as she takes the helm of troubled multilateral organization during a time of deepening economic turmoil. As the first female leader of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and...

Christine Lagarde (B): Being a Public Servant

This case covers the career of Christine Lagarde from 2005 to 2011 after she joins the French Government. After serving several grueling years as Finance Minister during the financial crises that started in 2007/2008, she is being considered as...

Christine Lagarde (A): A French Prime Minister Calls

This case covers formative events and influences in Christine Lagarde's childhood and her trajectory from studying political science and law to heading the world's largest law firm. As she prepares to transition back to practice in 2005, the new...

Christine Lagarde (Extended)

For a modular presentation of the same material, please see Christine Lagarde (A): A French Prime Minister Calls (2136.0), Christine Lagarde (B): Being a Public Servant (2137.0), and Christine Lagarde (C): Managing the IMF (2138.0). These...

Case Studies in Business Economics, Managerial Economics, Economics Case Study, MBA Case Studies

Ibs ® case development centre, asia-pacific's largest repository of management case studies, mba course case maps.

- Business Models

- Blue Ocean Strategy

- Competition & Strategy ⁄ Competitive Strategies

- Core Competency & Competitive Advantage

- Corporate Strategy

- Corporate Transformation

- Diversification Strategies

- Going Global & Managing Global Businesses

- Growth Strategies

- Industry Analysis

- Managing In Troubled Times ⁄ Managing a Crisis ⁄ Product Recalls

- Market Entry Strategies

- Mergers, Acquisitions & Takeovers

- Product Recalls

- Restructuring / Turnaround Strategies

- Strategic Alliances, Collaboration & Joint Ventures

- Supply Chain Management

- Value Chain Analysis

- Vision, Mission & Goals

- Global Retailers

- Indian Retailing

- Brands & Branding and Private Labels

- Brand ⁄ Marketing Communication Strategies and Advertising & Promotional Strategies

- Consumer Behaviour

- Customer Relationship Management (CRM)

- Marketing Research

- Marketing Strategies ⁄ Strategic Marketing

- Positioning, Repositioning, Reverse Positioning Strategies

- Sales & Distribution

- Services Marketing

- Economic Crisis

- Fiscal Policy

- Government & Business Environment

- Macroeconomics

- Micro ⁄ Business ⁄ Managerial Economics

- Monetary Policy

- Public-Private Partnership

- Entrepreneurship

- Family Businesses

- Social Entrepreneurship

- Financial Management & Corporate Finance

- Investment & Banking

- Business Research Methods

- Operations & Project Management

- Operations Management

- Quantitative Methods

- Leadership,Organizational Change & CEOs

- Succession Planning

- Corporate Governance & Business Ethics

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- International Trade & Finance

- HRM ⁄ Organizational Behaviour

- Innovation & New Product Development

- Social Networking

- China-related Cases

- India-related Cases

- Women Executives ⁄ CEO's

- Effective Executive Interviews

- Video Interviews

Executive Brief

- Movie Based Case Studies

- Case Catalogues

- Case studies in Other Languages

- Multimedia Case Studies

- Textbook Adoptions

- Customized Categories

- Free Case Studies

- Faculty Zone

- Student Zone

Economics case studies

Covering micro as well as macro economics, some of IBSCDC's case studies require a prior understanding of certain economic concepts, while many case studies can be used to derive the underlying economic concepts. Topics like Demand and Supply Analysis, Market Structures (Perfect Competition, Monopoly, Monopolistic, etc.), Cost Structures, etc., in micro economics and national income accounting, monetary and fiscal policies, exchange rate dynamics, etc., in macro economics can be discussed through these case studies.

Browse Economics Case Studies By

Sub-Categories

- Government and Business Environment

- Micro / Business / Managerial Economics

- Public Private Partnership

- Aircraft & Ship Building

- Automobiles

- Home Appliances & Personal Care Products

- Minerals, Metals & Mining

- Engineering, Electrical & Electronics

- Building Materials & Construction Equipment

- Food, Diary & Agriculture Products

- Oil & Natural Gas

- Office Equipment

- Banking, Insurance & Financial Services

- Telecommunications

- e-commerce & Internet

- Transportation

- Entertainment

- Advertising

- IT and ITES

- Leisure & Tourism

- Health Care

- Sports & Sports Related

- General Business

- Business Law, Corporate Governence & Ethics

- Conglomerates

Companies & Organizations

- China Aviation Oil Corp

- De Beers and Lev Leviev

- Goldman Sachs

- Gordon Brown

- Iliad Group, France Telecom

- Lehman Brothers

- Merrill Lynch

- Mittal Arcelor

- Morgan Stanley

- Northern Rock

- Temasek Holdings

- Wachovia Wells Fargo

- Dominican Republic

- Netherlands

- North America

- Saudi Arabia

- South Africa

- South Korea

- United Kingdom

- United Arab Emirates

- United States

Recently Bought Case Studies

- Tata Consultancy Services: Managing Liquidity Risk

- SSS�s Experiment: Choosing an Appropriate Research Design

- Differentiating Services: Yatra.com�s �Click and Mortar�Model

- Wedding Services Business in India: Led by Entrepreneurs

- Shinsei Bank - A Turnaround

- Accenture�s Grand Vision: �Corporate America�s Superstar Maker�

- Tata Group�s Strategy: Ratan Tata�s Vision

- MindTree Consulting: Designing and Delivering its Mission and Vision

- Coca-Cola in India: Innovative Distribution Strategies with 'RED' Approach

- IndiGo�s Low-Cost Carrier Operating Model: Flying High in Turbulent Skies

- Evaluation of GMR Hyderabad International Airport Limited (GHIAL)

- Ambuja Cements: Weighted Average Cost of Capital

- Walmart-Bharti Retail Alliance in India: The Best Way Forward?

- Exploring Primary and Secondary Data: Lessons to Learn

- Global Inflationary Trends: Raising Pressure on Central Banks

- Performance Management System@TCS

- Violet Home Theater System: A Sound Innovation

- Consumer�s Perception on Inverters in India: A Factor Analysis Case

- Demand Forecasting of Magic Foods using Multiple Regression Analysis Technique

New Case Studies In Economics

- The Sri Lankan Economic Crisis � What Went Wrong?

- Crude Oil Market and the Law of Supply

- Understanding Crude Oil Demand

- The `C` Factor: Cement Industry in India � Unhealthy Oligopoly & Controls

- Venezuela`s Macroeconomic Crisis: An Enduring Ordeal of Worsening Economy with Alarming Inflation

- Guwahati Molestation Case: Professional Responsibility Vs Moral Ethics

- The Renaissance of the South Africa Music Industry

- EU BREAK-UP?

- The Cyprus Bailout - Is the European Zone Failing?

- Global Financial Crisis and ITS Impact on Real and Financial Sectors in India

Best Selling Case Studies In Economics

- Perfect Competition under eBay: A Fact or a Factoid?

- Mexican Telecom Industry: (Un)wanted Monopoly?

- Mobile Telephony in India: Would Cheaper Rates Bring More Profits?

- US Financial Crisis: The Fall of Lehman Brothers

- Executive Pay Package: A Study of Demand and Supply

- OPEC: The Economics of a Cartel (A)

- OPEC The Economics of a Cartel (B)

- OPEC: The Economics of a Cartel (C)

- Comparative Cost Advantage and the American Outsourcing Backlash

- Global Oil Prices: Demand Side vs Supply Side Factors

Video Inerviews

Case studies on.

- View all Casebooks »

Course Case Mapping For

- View All Course Casemaps »

- View all Video Interviews »

- Executive Briefs

- Executive Inerviews

- View all Executive Briefs »

Executive Interviews

- View All Executive Interviews »

Contact us: IBS Case Development Centre (IBSCDC), IFHE Campus, Donthanapally, Sankarapally Road, Hyderabad-501203, Telangana, INDIA. Mob: +91- 9640901313, E-mail: [email protected]

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 17 April 2024

The economic commitment of climate change

- Maximilian Kotz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2564-5043 1 , 2 ,

- Anders Levermann ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4432-4704 1 , 2 &

- Leonie Wenz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8500-1568 1 , 3

Nature volume 628 , pages 551–557 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

80k Accesses

3415 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Environmental economics

- Environmental health

- Interdisciplinary studies

- Projection and prediction

Global projections of macroeconomic climate-change damages typically consider impacts from average annual and national temperatures over long time horizons 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 . Here we use recent empirical findings from more than 1,600 regions worldwide over the past 40 years to project sub-national damages from temperature and precipitation, including daily variability and extremes 7 , 8 . Using an empirical approach that provides a robust lower bound on the persistence of impacts on economic growth, we find that the world economy is committed to an income reduction of 19% within the next 26 years independent of future emission choices (relative to a baseline without climate impacts, likely range of 11–29% accounting for physical climate and empirical uncertainty). These damages already outweigh the mitigation costs required to limit global warming to 2 °C by sixfold over this near-term time frame and thereafter diverge strongly dependent on emission choices. Committed damages arise predominantly through changes in average temperature, but accounting for further climatic components raises estimates by approximately 50% and leads to stronger regional heterogeneity. Committed losses are projected for all regions except those at very high latitudes, at which reductions in temperature variability bring benefits. The largest losses are committed at lower latitudes in regions with lower cumulative historical emissions and lower present-day income.

Similar content being viewed by others

Climate damage projections beyond annual temperature

Investment incentive reduced by climate damages can be restored by optimal policy

Climate economics support for the UN climate targets

Projections of the macroeconomic damage caused by future climate change are crucial to informing public and policy debates about adaptation, mitigation and climate justice. On the one hand, adaptation against climate impacts must be justified and planned on the basis of an understanding of their future magnitude and spatial distribution 9 . This is also of importance in the context of climate justice 10 , as well as to key societal actors, including governments, central banks and private businesses, which increasingly require the inclusion of climate risks in their macroeconomic forecasts to aid adaptive decision-making 11 , 12 . On the other hand, climate mitigation policy such as the Paris Climate Agreement is often evaluated by balancing the costs of its implementation against the benefits of avoiding projected physical damages. This evaluation occurs both formally through cost–benefit analyses 1 , 4 , 5 , 6 , as well as informally through public perception of mitigation and damage costs 13 .

Projections of future damages meet challenges when informing these debates, in particular the human biases relating to uncertainty and remoteness that are raised by long-term perspectives 14 . Here we aim to overcome such challenges by assessing the extent of economic damages from climate change to which the world is already committed by historical emissions and socio-economic inertia (the range of future emission scenarios that are considered socio-economically plausible 15 ). Such a focus on the near term limits the large uncertainties about diverging future emission trajectories, the resulting long-term climate response and the validity of applying historically observed climate–economic relations over long timescales during which socio-technical conditions may change considerably. As such, this focus aims to simplify the communication and maximize the credibility of projected economic damages from future climate change.

In projecting the future economic damages from climate change, we make use of recent advances in climate econometrics that provide evidence for impacts on sub-national economic growth from numerous components of the distribution of daily temperature and precipitation 3 , 7 , 8 . Using fixed-effects panel regression models to control for potential confounders, these studies exploit within-region variation in local temperature and precipitation in a panel of more than 1,600 regions worldwide, comprising climate and income data over the past 40 years, to identify the plausibly causal effects of changes in several climate variables on economic productivity 16 , 17 . Specifically, macroeconomic impacts have been identified from changing daily temperature variability, total annual precipitation, the annual number of wet days and extreme daily rainfall that occur in addition to those already identified from changing average temperature 2 , 3 , 18 . Moreover, regional heterogeneity in these effects based on the prevailing local climatic conditions has been found using interactions terms. The selection of these climate variables follows micro-level evidence for mechanisms related to the impacts of average temperatures on labour and agricultural productivity 2 , of temperature variability on agricultural productivity and health 7 , as well as of precipitation on agricultural productivity, labour outcomes and flood damages 8 (see Extended Data Table 1 for an overview, including more detailed references). References 7 , 8 contain a more detailed motivation for the use of these particular climate variables and provide extensive empirical tests about the robustness and nature of their effects on economic output, which are summarized in Methods . By accounting for these extra climatic variables at the sub-national level, we aim for a more comprehensive description of climate impacts with greater detail across both time and space.

Constraining the persistence of impacts

A key determinant and source of discrepancy in estimates of the magnitude of future climate damages is the extent to which the impact of a climate variable on economic growth rates persists. The two extreme cases in which these impacts persist indefinitely or only instantaneously are commonly referred to as growth or level effects 19 , 20 (see Methods section ‘Empirical model specification: fixed-effects distributed lag models’ for mathematical definitions). Recent work shows that future damages from climate change depend strongly on whether growth or level effects are assumed 20 . Following refs. 2 , 18 , we provide constraints on this persistence by using distributed lag models to test the significance of delayed effects separately for each climate variable. Notably, and in contrast to refs. 2 , 18 , we use climate variables in their first-differenced form following ref. 3 , implying a dependence of the growth rate on a change in climate variables. This choice means that a baseline specification without any lags constitutes a model prior of purely level effects, in which a permanent change in the climate has only an instantaneous effect on the growth rate 3 , 19 , 21 . By including lags, one can then test whether any effects may persist further. This is in contrast to the specification used by refs. 2 , 18 , in which climate variables are used without taking the first difference, implying a dependence of the growth rate on the level of climate variables. In this alternative case, the baseline specification without any lags constitutes a model prior of pure growth effects, in which a change in climate has an infinitely persistent effect on the growth rate. Consequently, including further lags in this alternative case tests whether the initial growth impact is recovered 18 , 19 , 21 . Both of these specifications suffer from the limiting possibility that, if too few lags are included, one might falsely accept the model prior. The limitations of including a very large number of lags, including loss of data and increasing statistical uncertainty with an increasing number of parameters, mean that such a possibility is likely. By choosing a specification in which the model prior is one of level effects, our approach is therefore conservative by design, avoiding assumptions of infinite persistence of climate impacts on growth and instead providing a lower bound on this persistence based on what is observable empirically (see Methods section ‘Empirical model specification: fixed-effects distributed lag models’ for further exposition of this framework). The conservative nature of such a choice is probably the reason that ref. 19 finds much greater consistency between the impacts projected by models that use the first difference of climate variables, as opposed to their levels.

We begin our empirical analysis of the persistence of climate impacts on growth using ten lags of the first-differenced climate variables in fixed-effects distributed lag models. We detect substantial effects on economic growth at time lags of up to approximately 8–10 years for the temperature terms and up to approximately 4 years for the precipitation terms (Extended Data Fig. 1 and Extended Data Table 2 ). Furthermore, evaluation by means of information criteria indicates that the inclusion of all five climate variables and the use of these numbers of lags provide a preferable trade-off between best-fitting the data and including further terms that could cause overfitting, in comparison with model specifications excluding climate variables or including more or fewer lags (Extended Data Fig. 3 , Supplementary Methods Section 1 and Supplementary Table 1 ). We therefore remove statistically insignificant terms at later lags (Supplementary Figs. 1 – 3 and Supplementary Tables 2 – 4 ). Further tests using Monte Carlo simulations demonstrate that the empirical models are robust to autocorrelation in the lagged climate variables (Supplementary Methods Section 2 and Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5 ), that information criteria provide an effective indicator for lag selection (Supplementary Methods Section 2 and Supplementary Fig. 6 ), that the results are robust to concerns of imperfect multicollinearity between climate variables and that including several climate variables is actually necessary to isolate their separate effects (Supplementary Methods Section 3 and Supplementary Fig. 7 ). We provide a further robustness check using a restricted distributed lag model to limit oscillations in the lagged parameter estimates that may result from autocorrelation, finding that it provides similar estimates of cumulative marginal effects to the unrestricted model (Supplementary Methods Section 4 and Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9 ). Finally, to explicitly account for any outstanding uncertainty arising from the precise choice of the number of lags, we include empirical models with marginally different numbers of lags in the error-sampling procedure of our projection of future damages. On the basis of the lag-selection procedure (the significance of lagged terms in Extended Data Fig. 1 and Extended Data Table 2 , as well as information criteria in Extended Data Fig. 3 ), we sample from models with eight to ten lags for temperature and four for precipitation (models shown in Supplementary Figs. 1 – 3 and Supplementary Tables 2 – 4 ). In summary, this empirical approach to constrain the persistence of climate impacts on economic growth rates is conservative by design in avoiding assumptions of infinite persistence, but nevertheless provides a lower bound on the extent of impact persistence that is robust to the numerous tests outlined above.

Committed damages until mid-century

We combine these empirical economic response functions (Supplementary Figs. 1 – 3 and Supplementary Tables 2 – 4 ) with an ensemble of 21 climate models (see Supplementary Table 5 ) from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP-6) 22 to project the macroeconomic damages from these components of physical climate change (see Methods for further details). Bias-adjusted climate models that provide a highly accurate reproduction of observed climatological patterns with limited uncertainty (Supplementary Table 6 ) are used to avoid introducing biases in the projections. Following a well-developed literature 2 , 3 , 19 , these projections do not aim to provide a prediction of future economic growth. Instead, they are a projection of the exogenous impact of future climate conditions on the economy relative to the baselines specified by socio-economic projections, based on the plausibly causal relationships inferred by the empirical models and assuming ceteris paribus. Other exogenous factors relevant for the prediction of economic output are purposefully assumed constant.

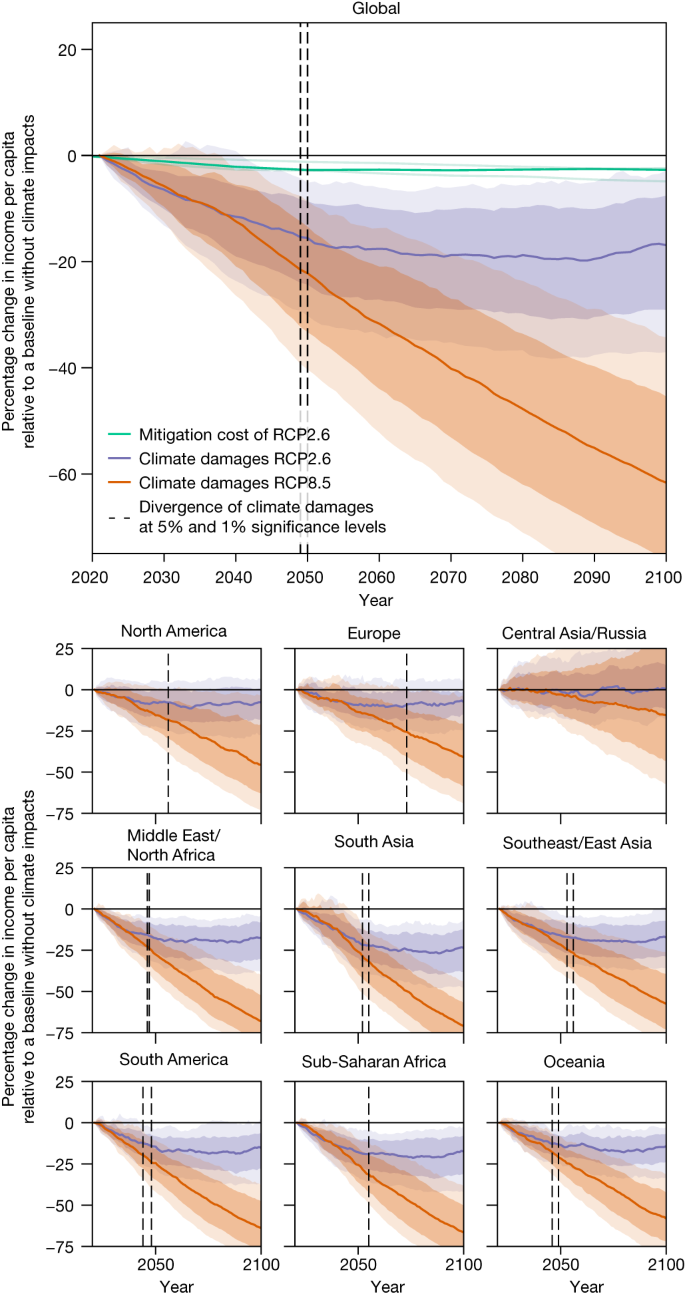

A Monte Carlo procedure that samples from climate model projections, empirical models with different numbers of lags and model parameter estimates (obtained by 1,000 block-bootstrap resamples of each of the regressions in Supplementary Figs. 1 – 3 and Supplementary Tables 2 – 4 ) is used to estimate the combined uncertainty from these sources. Given these uncertainty distributions, we find that projected global damages are statistically indistinguishable across the two most extreme emission scenarios until 2049 (at the 5% significance level; Fig. 1 ). As such, the climate damages occurring before this time constitute those to which the world is already committed owing to the combination of past emissions and the range of future emission scenarios that are considered socio-economically plausible 15 . These committed damages comprise a permanent income reduction of 19% on average globally (population-weighted average) in comparison with a baseline without climate-change impacts (with a likely range of 11–29%, following the likelihood classification adopted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC); see caption of Fig. 1 ). Even though levels of income per capita generally still increase relative to those of today, this constitutes a permanent income reduction for most regions, including North America and Europe (each with median income reductions of approximately 11%) and with South Asia and Africa being the most strongly affected (each with median income reductions of approximately 22%; Fig. 1 ). Under a middle-of-the road scenario of future income development (SSP2, in which SSP stands for Shared Socio-economic Pathway), this corresponds to global annual damages in 2049 of 38 trillion in 2005 international dollars (likely range of 19–59 trillion 2005 international dollars). Compared with empirical specifications that assume pure growth or pure level effects, our preferred specification that provides a robust lower bound on the extent of climate impact persistence produces damages between these two extreme assumptions (Extended Data Fig. 3 ).

Estimates of the projected reduction in income per capita from changes in all climate variables based on empirical models of climate impacts on economic output with a robust lower bound on their persistence (Extended Data Fig. 1 ) under a low-emission scenario compatible with the 2 °C warming target and a high-emission scenario (SSP2-RCP2.6 and SSP5-RCP8.5, respectively) are shown in purple and orange, respectively. Shading represents the 34% and 10% confidence intervals reflecting the likely and very likely ranges, respectively (following the likelihood classification adopted by the IPCC), having estimated uncertainty from a Monte Carlo procedure, which samples the uncertainty from the choice of physical climate models, empirical models with different numbers of lags and bootstrapped estimates of the regression parameters shown in Supplementary Figs. 1 – 3 . Vertical dashed lines show the time at which the climate damages of the two emission scenarios diverge at the 5% and 1% significance levels based on the distribution of differences between emission scenarios arising from the uncertainty sampling discussed above. Note that uncertainty in the difference of the two scenarios is smaller than the combined uncertainty of the two respective scenarios because samples of the uncertainty (climate model and empirical model choice, as well as model parameter bootstrap) are consistent across the two emission scenarios, hence the divergence of damages occurs while the uncertainty bounds of the two separate damage scenarios still overlap. Estimates of global mitigation costs from the three IAMs that provide results for the SSP2 baseline and SSP2-RCP2.6 scenario are shown in light green in the top panel, with the median of these estimates shown in bold.

Damages already outweigh mitigation costs

We compare the damages to which the world is committed over the next 25 years to estimates of the mitigation costs required to achieve the Paris Climate Agreement. Taking estimates of mitigation costs from the three integrated assessment models (IAMs) in the IPCC AR6 database 23 that provide results under comparable scenarios (SSP2 baseline and SSP2-RCP2.6, in which RCP stands for Representative Concentration Pathway), we find that the median committed climate damages are larger than the median mitigation costs in 2050 (six trillion in 2005 international dollars) by a factor of approximately six (note that estimates of mitigation costs are only provided every 10 years by the IAMs and so a comparison in 2049 is not possible). This comparison simply aims to compare the magnitude of future damages against mitigation costs, rather than to conduct a formal cost–benefit analysis of transitioning from one emission path to another. Formal cost–benefit analyses typically find that the net benefits of mitigation only emerge after 2050 (ref. 5 ), which may lead some to conclude that physical damages from climate change are simply not large enough to outweigh mitigation costs until the second half of the century. Our simple comparison of their magnitudes makes clear that damages are actually already considerably larger than mitigation costs and the delayed emergence of net mitigation benefits results primarily from the fact that damages across different emission paths are indistinguishable until mid-century (Fig. 1 ).

Although these near-term damages constitute those to which the world is already committed, we note that damage estimates diverge strongly across emission scenarios after 2049, conveying the clear benefits of mitigation from a purely economic point of view that have been emphasized in previous studies 4 , 24 . As well as the uncertainties assessed in Fig. 1 , these conclusions are robust to structural choices, such as the timescale with which changes in the moderating variables of the empirical models are estimated (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11 ), as well as the order in which one accounts for the intertemporal and international components of currency comparison (Supplementary Fig. 12 ; see Methods for further details).

Damages from variability and extremes

Committed damages primarily arise through changes in average temperature (Fig. 2 ). This reflects the fact that projected changes in average temperature are larger than those in other climate variables when expressed as a function of their historical interannual variability (Extended Data Fig. 4 ). Because the historical variability is that on which the empirical models are estimated, larger projected changes in comparison with this variability probably lead to larger future impacts in a purely statistical sense. From a mechanistic perspective, one may plausibly interpret this result as implying that future changes in average temperature are the most unprecedented from the perspective of the historical fluctuations to which the economy is accustomed and therefore will cause the most damage. This insight may prove useful in terms of guiding adaptation measures to the sources of greatest damage.

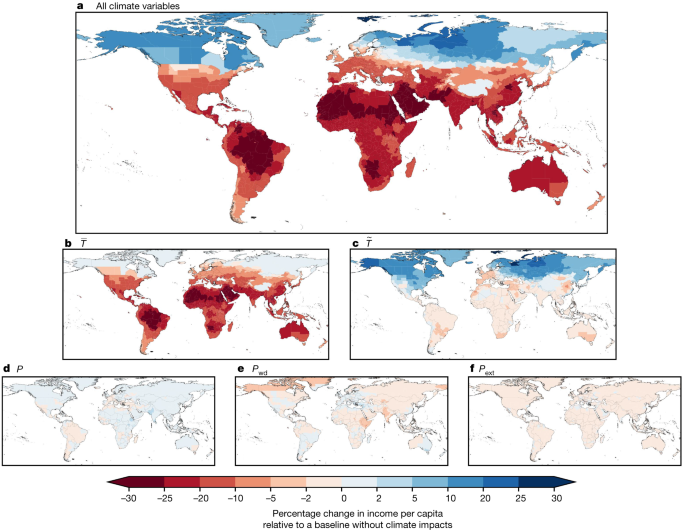

Estimates of the median projected reduction in sub-national income per capita across emission scenarios (SSP2-RCP2.6 and SSP2-RCP8.5) as well as climate model, empirical model and model parameter uncertainty in the year in which climate damages diverge at the 5% level (2049, as identified in Fig. 1 ). a , Impacts arising from all climate variables. b – f , Impacts arising separately from changes in annual mean temperature ( b ), daily temperature variability ( c ), total annual precipitation ( d ), the annual number of wet days (>1 mm) ( e ) and extreme daily rainfall ( f ) (see Methods for further definitions). Data on national administrative boundaries are obtained from the GADM database version 3.6 and are freely available for academic use ( https://gadm.org/ ).

Nevertheless, future damages based on empirical models that consider changes in annual average temperature only and exclude the other climate variables constitute income reductions of only 13% in 2049 (Extended Data Fig. 5a , likely range 5–21%). This suggests that accounting for the other components of the distribution of temperature and precipitation raises net damages by nearly 50%. This increase arises through the further damages that these climatic components cause, but also because their inclusion reveals a stronger negative economic response to average temperatures (Extended Data Fig. 5b ). The latter finding is consistent with our Monte Carlo simulations, which suggest that the magnitude of the effect of average temperature on economic growth is underestimated unless accounting for the impacts of other correlated climate variables (Supplementary Fig. 7 ).

In terms of the relative contributions of the different climatic components to overall damages, we find that accounting for daily temperature variability causes the largest increase in overall damages relative to empirical frameworks that only consider changes in annual average temperature (4.9 percentage points, likely range 2.4–8.7 percentage points, equivalent to approximately 10 trillion international dollars). Accounting for precipitation causes smaller increases in overall damages, which are—nevertheless—equivalent to approximately 1.2 trillion international dollars: 0.01 percentage points (−0.37–0.33 percentage points), 0.34 percentage points (0.07–0.90 percentage points) and 0.36 percentage points (0.13–0.65 percentage points) from total annual precipitation, the number of wet days and extreme daily precipitation, respectively. Moreover, climate models seem to underestimate future changes in temperature variability 25 and extreme precipitation 26 , 27 in response to anthropogenic forcing as compared with that observed historically, suggesting that the true impacts from these variables may be larger.

The distribution of committed damages

The spatial distribution of committed damages (Fig. 2a ) reflects a complex interplay between the patterns of future change in several climatic components and those of historical economic vulnerability to changes in those variables. Damages resulting from increasing annual mean temperature (Fig. 2b ) are negative almost everywhere globally, and larger at lower latitudes in regions in which temperatures are already higher and economic vulnerability to temperature increases is greatest (see the response heterogeneity to mean temperature embodied in Extended Data Fig. 1a ). This occurs despite the amplified warming projected at higher latitudes 28 , suggesting that regional heterogeneity in economic vulnerability to temperature changes outweighs heterogeneity in the magnitude of future warming (Supplementary Fig. 13a ). Economic damages owing to daily temperature variability (Fig. 2c ) exhibit a strong latitudinal polarisation, primarily reflecting the physical response of daily variability to greenhouse forcing in which increases in variability across lower latitudes (and Europe) contrast decreases at high latitudes 25 (Supplementary Fig. 13b ). These two temperature terms are the dominant determinants of the pattern of overall damages (Fig. 2a ), which exhibits a strong polarity with damages across most of the globe except at the highest northern latitudes. Future changes in total annual precipitation mainly bring economic benefits except in regions of drying, such as the Mediterranean and central South America (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 13c ), but these benefits are opposed by changes in the number of wet days, which produce damages with a similar pattern of opposite sign (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 13d ). By contrast, changes in extreme daily rainfall produce damages in all regions, reflecting the intensification of daily rainfall extremes over global land areas 29 , 30 (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 13e ).

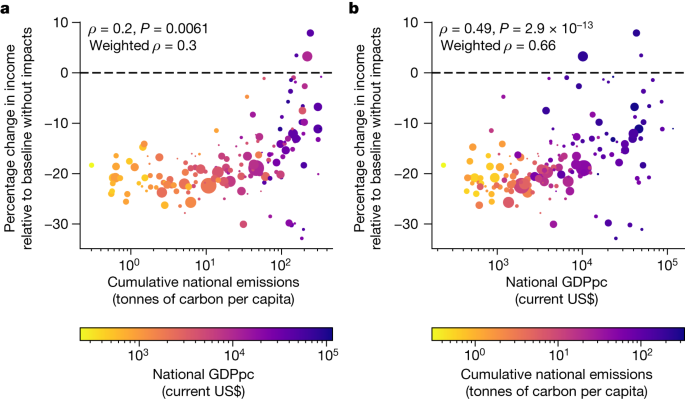

The spatial distribution of committed damages implies considerable injustice along two dimensions: culpability for the historical emissions that have caused climate change and pre-existing levels of socio-economic welfare. Spearman’s rank correlations indicate that committed damages are significantly larger in countries with smaller historical cumulative emissions, as well as in regions with lower current income per capita (Fig. 3 ). This implies that those countries that will suffer the most from the damages already committed are those that are least responsible for climate change and which also have the least resources to adapt to it.

Estimates of the median projected change in national income per capita across emission scenarios (RCP2.6 and RCP8.5) as well as climate model, empirical model and model parameter uncertainty in the year in which climate damages diverge at the 5% level (2049, as identified in Fig. 1 ) are plotted against cumulative national emissions per capita in 2020 (from the Global Carbon Project) and coloured by national income per capita in 2020 (from the World Bank) in a and vice versa in b . In each panel, the size of each scatter point is weighted by the national population in 2020 (from the World Bank). Inset numbers indicate the Spearman’s rank correlation ρ and P -values for a hypothesis test whose null hypothesis is of no correlation, as well as the Spearman’s rank correlation weighted by national population.

To further quantify this heterogeneity, we assess the difference in committed damages between the upper and lower quartiles of regions when ranked by present income levels and historical cumulative emissions (using a population weighting to both define the quartiles and estimate the group averages). On average, the quartile of countries with lower income are committed to an income loss that is 8.9 percentage points (or 61%) greater than the upper quartile (Extended Data Fig. 6 ), with a likely range of 3.8–14.7 percentage points across the uncertainty sampling of our damage projections (following the likelihood classification adopted by the IPCC). Similarly, the quartile of countries with lower historical cumulative emissions are committed to an income loss that is 6.9 percentage points (or 40%) greater than the upper quartile, with a likely range of 0.27–12 percentage points. These patterns reemphasize the prevalence of injustice in climate impacts 31 , 32 , 33 in the context of the damages to which the world is already committed by historical emissions and socio-economic inertia.

Contextualizing the magnitude of damages

The magnitude of projected economic damages exceeds previous literature estimates 2 , 3 , arising from several developments made on previous approaches. Our estimates are larger than those of ref. 2 (see first row of Extended Data Table 3 ), primarily because of the facts that sub-national estimates typically show a steeper temperature response (see also refs. 3 , 34 ) and that accounting for other climatic components raises damage estimates (Extended Data Fig. 5 ). However, we note that our empirical approach using first-differenced climate variables is conservative compared with that of ref. 2 in regard to the persistence of climate impacts on growth (see introduction and Methods section ‘Empirical model specification: fixed-effects distributed lag models’), an important determinant of the magnitude of long-term damages 19 , 21 . Using a similar empirical specification to ref. 2 , which assumes infinite persistence while maintaining the rest of our approach (sub-national data and further climate variables), produces considerably larger damages (purple curve of Extended Data Fig. 3 ). Compared with studies that do take the first difference of climate variables 3 , 35 , our estimates are also larger (see second and third rows of Extended Data Table 3 ). The inclusion of further climate variables (Extended Data Fig. 5 ) and a sufficient number of lags to more adequately capture the extent of impact persistence (Extended Data Figs. 1 and 2 ) are the main sources of this difference, as is the use of specifications that capture nonlinearities in the temperature response when compared with ref. 35 . In summary, our estimates develop on previous studies by incorporating the latest data and empirical insights 7 , 8 , as well as in providing a robust empirical lower bound on the persistence of impacts on economic growth, which constitutes a middle ground between the extremes of the growth-versus-levels debate 19 , 21 (Extended Data Fig. 3 ).

Compared with the fraction of variance explained by the empirical models historically (<5%), the projection of reductions in income of 19% may seem large. This arises owing to the fact that projected changes in climatic conditions are much larger than those that were experienced historically, particularly for changes in average temperature (Extended Data Fig. 4 ). As such, any assessment of future climate-change impacts necessarily requires an extrapolation outside the range of the historical data on which the empirical impact models were evaluated. Nevertheless, these models constitute the most state-of-the-art methods for inference of plausibly causal climate impacts based on observed data. Moreover, we take explicit steps to limit out-of-sample extrapolation by capping the moderating variables of the interaction terms at the 95th percentile of the historical distribution (see Methods ). This avoids extrapolating the marginal effects outside what was observed historically. Given the nonlinear response of economic output to annual mean temperature (Extended Data Fig. 1 and Extended Data Table 2 ), this is a conservative choice that limits the magnitude of damages that we project. Furthermore, back-of-the-envelope calculations indicate that the projected damages are consistent with the magnitude and patterns of historical economic development (see Supplementary Discussion Section 5 ).

Missing impacts and spatial spillovers

Despite assessing several climatic components from which economic impacts have recently been identified 3 , 7 , 8 , this assessment of aggregate climate damages should not be considered comprehensive. Important channels such as impacts from heatwaves 31 , sea-level rise 36 , tropical cyclones 37 and tipping points 38 , 39 , as well as non-market damages such as those to ecosystems 40 and human health 41 , are not considered in these estimates. Sea-level rise is unlikely to be feasibly incorporated into empirical assessments such as this because historical sea-level variability is mostly small. Non-market damages are inherently intractable within our estimates of impacts on aggregate monetary output and estimates of these impacts could arguably be considered as extra to those identified here. Recent empirical work suggests that accounting for these channels would probably raise estimates of these committed damages, with larger damages continuing to arise in the global south 31 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 .

Moreover, our main empirical analysis does not explicitly evaluate the potential for impacts in local regions to produce effects that ‘spill over’ into other regions. Such effects may further mitigate or amplify the impacts we estimate, for example, if companies relocate production from one affected region to another or if impacts propagate along supply chains. The current literature indicates that trade plays a substantial role in propagating spillover effects 43 , 44 , making their assessment at the sub-national level challenging without available data on sub-national trade dependencies. Studies accounting for only spatially adjacent neighbours indicate that negative impacts in one region induce further negative impacts in neighbouring regions 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , suggesting that our projected damages are probably conservative by excluding these effects. In Supplementary Fig. 14 , we assess spillovers from neighbouring regions using a spatial-lag model. For simplicity, this analysis excludes temporal lags, focusing only on contemporaneous effects. The results show that accounting for spatial spillovers can amplify the overall magnitude, and also the heterogeneity, of impacts. Consistent with previous literature, this indicates that the overall magnitude (Fig. 1 ) and heterogeneity (Fig. 3 ) of damages that we project in our main specification may be conservative without explicitly accounting for spillovers. We note that further analysis that addresses both spatially and trade-connected spillovers, while also accounting for delayed impacts using temporal lags, would be necessary to adequately address this question fully. These approaches offer fruitful avenues for further research but are beyond the scope of this manuscript, which primarily aims to explore the impacts of different climate conditions and their persistence.

Policy implications

We find that the economic damages resulting from climate change until 2049 are those to which the world economy is already committed and that these greatly outweigh the costs required to mitigate emissions in line with the 2 °C target of the Paris Climate Agreement (Fig. 1 ). This assessment is complementary to formal analyses of the net costs and benefits associated with moving from one emission path to another, which typically find that net benefits of mitigation only emerge in the second half of the century 5 . Our simple comparison of the magnitude of damages and mitigation costs makes clear that this is primarily because damages are indistinguishable across emissions scenarios—that is, committed—until mid-century (Fig. 1 ) and that they are actually already much larger than mitigation costs. For simplicity, and owing to the availability of data, we compare damages to mitigation costs at the global level. Regional estimates of mitigation costs may shed further light on the national incentives for mitigation to which our results already hint, of relevance for international climate policy. Although these damages are committed from a mitigation perspective, adaptation may provide an opportunity to reduce them. Moreover, the strong divergence of damages after mid-century reemphasizes the clear benefits of mitigation from a purely economic perspective, as highlighted in previous studies 1 , 4 , 6 , 24 .

Historical climate data

Historical daily 2-m temperature and precipitation totals (in mm) are obtained for the period 1979–2019 from the W5E5 database. The W5E5 dataset comes from ERA-5, a state-of-the-art reanalysis of historical observations, but has been bias-adjusted by applying version 2.0 of the WATCH Forcing Data to ERA-5 reanalysis data and precipitation data from version 2.3 of the Global Precipitation Climatology Project to better reflect ground-based measurements 49 , 50 , 51 . We obtain these data on a 0.5° × 0.5° grid from the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project (ISIMIP) database. Notably, these historical data have been used to bias-adjust future climate projections from CMIP-6 (see the following section), ensuring consistency between the distribution of historical daily weather on which our empirical models were estimated and the climate projections used to estimate future damages. These data are publicly available from the ISIMIP database. See refs. 7 , 8 for robustness tests of the empirical models to the choice of climate data reanalysis products.

Future climate data

Daily 2-m temperature and precipitation totals (in mm) are taken from 21 climate models participating in CMIP-6 under a high (RCP8.5) and a low (RCP2.6) greenhouse gas emission scenario from 2015 to 2100. The data have been bias-adjusted and statistically downscaled to a common half-degree grid to reflect the historical distribution of daily temperature and precipitation of the W5E5 dataset using the trend-preserving method developed by the ISIMIP 50 , 52 . As such, the climate model data reproduce observed climatological patterns exceptionally well (Supplementary Table 5 ). Gridded data are publicly available from the ISIMIP database.

Historical economic data

Historical economic data come from the DOSE database of sub-national economic output 53 . We use a recent revision to the DOSE dataset that provides data across 83 countries, 1,660 sub-national regions with varying temporal coverage from 1960 to 2019. Sub-national units constitute the first administrative division below national, for example, states for the USA and provinces for China. Data come from measures of gross regional product per capita (GRPpc) or income per capita in local currencies, reflecting the values reported in national statistical agencies, yearbooks and, in some cases, academic literature. We follow previous literature 3 , 7 , 8 , 54 and assess real sub-national output per capita by first converting values from local currencies to US dollars to account for diverging national inflationary tendencies and then account for US inflation using a US deflator. Alternatively, one might first account for national inflation and then convert between currencies. Supplementary Fig. 12 demonstrates that our conclusions are consistent when accounting for price changes in the reversed order, although the magnitude of estimated damages varies. See the documentation of the DOSE dataset for further discussion of these choices. Conversions between currencies are conducted using exchange rates from the FRED database of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis 55 and the national deflators from the World Bank 56 .

Future socio-economic data

Baseline gridded gross domestic product (GDP) and population data for the period 2015–2100 are taken from the middle-of-the-road scenario SSP2 (ref. 15 ). Population data have been downscaled to a half-degree grid by the ISIMIP following the methodologies of refs. 57 , 58 , which we then aggregate to the sub-national level of our economic data using the spatial aggregation procedure described below. Because current methodologies for downscaling the GDP of the SSPs use downscaled population to do so, per-capita estimates of GDP with a realistic distribution at the sub-national level are not readily available for the SSPs. We therefore use national-level GDP per capita (GDPpc) projections for all sub-national regions of a given country, assuming homogeneity within countries in terms of baseline GDPpc. Here we use projections that have been updated to account for the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the trajectory of future income, while remaining consistent with the long-term development of the SSPs 59 . The choice of baseline SSP alters the magnitude of projected climate damages in monetary terms, but when assessed in terms of percentage change from the baseline, the choice of socio-economic scenario is inconsequential. Gridded SSP population data and national-level GDPpc data are publicly available from the ISIMIP database. Sub-national estimates as used in this study are available in the code and data replication files.

Climate variables