Roberto and Biology: A Case Study on Accommodations for Deafness

My name is Roberto and I am a premedical student majoring in biology. I have a severe-to-profound bilateral hearing loss and use hearing aids and speech reading (watching the movement of a person's lips) to maximize my communication skills. I have some knowledge of American Sign Language but not enough to effectively use a sign language interpreter as an accommodation.

Access Issues

My biology courses, as well as many other courses in science and mathematics, involve intensive lectures; some have interactive discussion sessions, and all of them make extensive use of advanced technical terms. Many of these terms are difficult to hear with hearing aids or to lip-read. I tried to use an FM amplification system (which through a microphone and transmitter worn by the instructor sends his or her words directly to my hearing aid) in these classes, but it was not helpful because of the nature of my hearing loss. If I miss information because of my hearing impairment, then I can't follow the lecture or adequately participate in discussion and ask questions. Note taking provides limited assistance since the notes are not verbatim, I can only review them after the class session, and sometimes the notes are available only one or two days after the class session. Note-taking assistance and front-row seating are adequate for me in nonscience and nonmathematics courses. Because the pace of instruction in science and mathematics is fast and the volume of material covered in each session is large, it is important that I have an adequate means to access the course lecture and discussion as it happens.

I contacted the office of disability services and requested the provision of real-time captioning in my science and mathematics classes. I told the counselor that I had tried various accommodations like note taking and the FM system but that I was still having difficulty with the lectures. The deaf services counselor reviewed my request and then approved it.

Real-time captioning as an accommodation involves having someone with adequate stenography training (often a court reporter) come to the class with me. The stenographer has a steno machine and laptop that is loaded with stenography software, and they sit next to me so I can see the monitor. When the instructor talks or others participate in class discussion, the stenographer enters all spoken words. The words spoken then appear very quickly on the monitor, and I can follow the discussion, ask questions, and, after class, get a hard copy of the notes. Alternatively, the office of disability services arranges for a stenographer at a remote site to provide the same service; in this situation, the instructor wears a wireless microphone that transmits the voice back over the same phone line that is used to instantly send back the real-time captions to the student with a laptop in the classroom. This alternative procedure is used when there is a shortage of qualified stenographers, there are scheduling difficulties, or it is the most cost-effective method to provide the accommodation.

This case study demonstrates the following:

- Students who are deaf or hard of hearing may have differing accommodation needs, and the accommodations may not be the same in all courses for the same student.

- Accommodation procedures and alternatives must be in place, or there must be a capacity to quickly make arrangements to implement the accommodation.

- There are advanced technical accommodations, such as real-time captioning, that may be available anywhere in the country when students and support staff are aware of the resources.

- Students who are deaf or hard of hearing and those with other sensory disabilities can compete in scientific and technical fields and careers.

- Health & Wellness

- Hearing Disorders

- Patient Care

- Amplification

- Hearing Aids

- Implants & Bone Conduction

- Tinnitus Devices

- Vestibular Solutions

- Accessories

- Office Services

- Practice Management

- Industry News

- Organizations

- White Papers

- Edition Archive

Select Page

Case Study of a 5-Year-Old Boy with Unilateral Hearing Loss

Jan 15, 2015 | Pediatric Care | 0 |

Case Study | Pediatrics | January 2015 Hearing Review

A reminder of what our tests really say about the auditory system..

By Michael Zagarella, AuD

How many times have I heard— and said myself—that the OAE is not a hearing test? How many times have I thought to myself that, just because a child passes their newborn hearing screening test, it does not mean they have normal hearing? This case brought those two statements front and center.

A 5-year-old boy was referred to me for a hearing test because he did not pass a kindergarten screening test in his right ear. His parents reported that he said “Huh?” frequently, and more recently they noticed him turning his head when spoken to. He had passed his newborn hearing screening, and he had experienced a few ear infections that responded well to antibiotics. The parents mentioned a maternal aunt who is “nearly totally deaf” and wears binaural hearing aids.

Initial Test Results

Otoscopic examination showed a clear ear canal and a normal-appearing tympanic membrane on the right side. The left ear canal contained non-occluding wax.

Tympanograms were within normal limits bilaterally. Unfortunately, otoacoustic emissions (OAE) testing could not be completed because of an equipment malfunction.

Behavioral testing with SRTs was taken, and I typically start with the right ear. The child seemed bright and cooperative enough for routine testing. I obtained no response until 80 dB.

I switched to the left ear and he responded appropriately. This prompted me to walk into the test booth and check the equipment and wires; everything was plugged in and looked normal. I tried SRTs again with the same results, even reversing the earphones. Same results. When the behavioral tests were completed, the results indicated normal hearing in his left ear and a profound hearing loss in his right ear.

The child’s parents were informed of these results, and we scheduled him to return for a retest in order to confirm these findings.

Follow-up Test

One week later, the boy returned for a follow-up test. The otoscopic exam was the same: RE = normal; LE = non-occluding wax.

Tympanograms were within normal limits. I added acoustic reflexes, which were normal in his left ear (80-90 dB), and questionable in his right ear (105-115 dB).

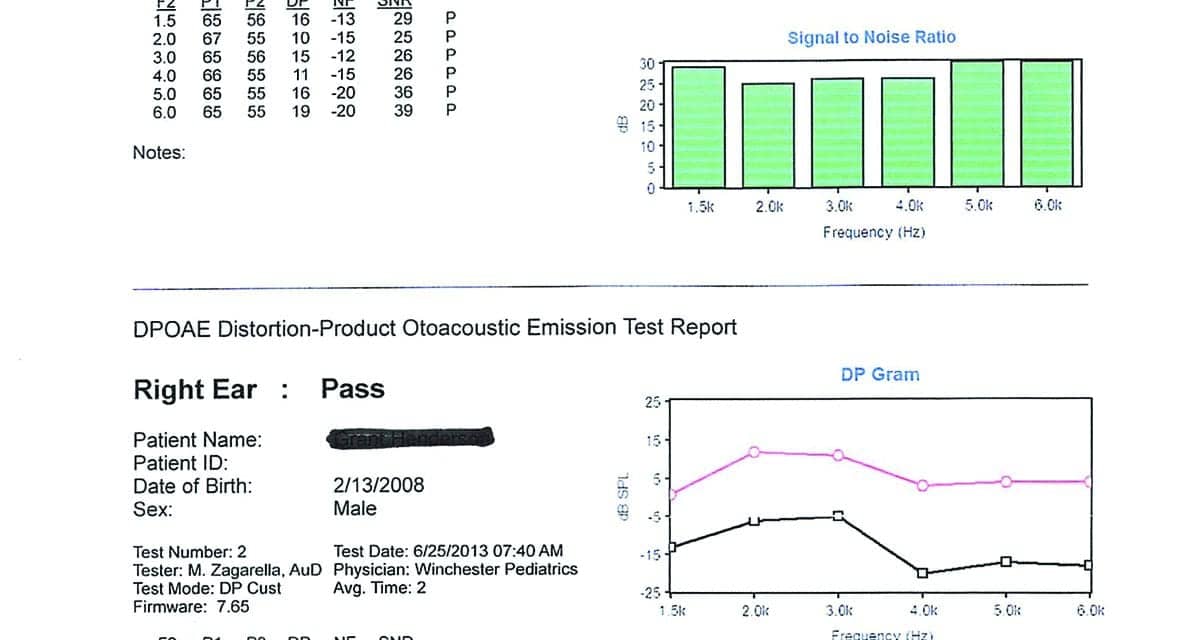

DPOAEs were present in both ears. The right ear was reduced in amplitude compared with the left, but not what I would expect to see with a profound hearing loss (Figure 1).

I repeated the behavioral tests with the same results that I obtained the first time (Figure 2). Bone conduction scores were not obtained at this time because I felt I was reaching the limits of a 5-year-old, and the tympanograms were normal on two occasions.

Recommendation to Parents

After completing the tests, I explained auditory dyssynchrony to the parents, and told them that this is what their son appeared to have. Since they were people with resources, I advised them to make an appointment at Johns Hopkins to have this diagnosis confirmed by ABR.

Johns Hopkins Results

The initial appointment at Johns Hopkins was at the ENT clinic. According to the report from the parents, the physician reviewed my test results and said it was unlikely that they were valid. She suggested they repeat the entire test battery before proceeding with an ABR. All peripheral tests were repeated with exactly the same results that I had obtained. The ABR was scheduled and performed, yielding:

“Findings are consistent with normal hearing sensitivity in the left ear and a neural hearing loss in the right ear consistent with auditory dyssynchrony (auditory neuropathy). The normal hearing in the left ear is adequate for speech and language development at this time.”

Additional Follow-up

The boy’s mother was not completely satisfied with the diagnosis or explanation. After she arrived home and mulled things over, she called Johns Hopkins and asked if they could do an MRI. The ENT assured her that it probably would not show anything, but if it would allay her concerns (and since they had good insurance coverage), they would schedule the MRI.

Further reading: Vestibular Assessment in Infant Cochlear Implant Candidates

Figure 1. DPOAEs of 5-year-old boy.

Findings of MRI. Evaluation of the right inner ear structures demonstrated absence of the right cochlear nerve. The vestibular nerve is present but is small in caliber. The internal auditory canal is somewhat small in diameter. There is atresia versus severe stenosis of the cochlear nerve canal. The right modiolus is thickened. The cochlea has the normal amount of turns, and the vestibule semicircular canals appear normal.

The left inner ear structures, cranial nerves VII and VIII complex, and internal auditory canal are normal. Additional normal findings were also presented regarding sinuses, etc.

Key finding: The results were consistent with atresia versus severe stenosis of the right cochlear nerve canal and cochlear nerve and deficiency described above.

The Value of Relearning in Everyday Clinical Practice

Figure 2. Follow-up behavioral test of 5-year-old boy.

According to the MRI, the cochlea on the right side is normal—which would explain the present DPOAE results. The cochlear branch of the VIIIth Cranial Nerve is completely absent, which would explain the absent ABR result and the profound hearing loss by behavioral testing.

This case has certainly caused me to re-evaluate what I think and say about my test findings. How many times have I heard—and said myself!—that the OAE is not a hearing test? How many times have I thought to myself that, just because a child passes their newborn hear- ing screening test, it does not mean that they have normal hearing?

This case has surely brought those two statements front and center. In addition, what about auditory neuropathy? In about 40 years of testing, I had never seen a case that I was convinced was AN. Naturally, I was somewhat skeptical about this disorder: Is it real, or does it reside in the realm of the Yeti. (Personal note to Dr Chuck Berlin: I truly don’t doubt you, but I do like to see things for myself!)

Finally, this case only reinforces my trust in “mother’s intuition” and the value of deferring to the sensible requests of parents. If she had not felt uneasy about what she had been told at one of the most prestigious clinics in the country, the actual source of this problem would not have been discovered.

So what? Does any of this really make a difference? The bottom line is we have a 5-year-old boy with a unilateral profound hearing loss. How important is it that we know why he has that loss? From a purely clinical standpoint, I think that it is poignant because it brings home the importance of understanding what our tests really say about the hearing mechanism and auditory system (ie, is working or not working?).

And although it may not make a large difference in the boy’s current treatment plan, I do know that the boy’s mother is grateful for understanding the reason for her son’s hearing loss and that it’s at least possible the boy may benefit from this knowledge in the future.

Michael Zagarella, AuD, is an audiologist at RESA 8 Audiology Clinic in Martinsburg, WVa.

Correspondence can be addressed to HR or or Dr Zagarella at: [email protected]

Citation for this article: Zagarella M. Case study of a 5-year-old boy with unilateral hearing loss. Hearing Review . 2015;22(1):30-33.

Related Posts

New Sensei: Oticon’s Most Value-Packed Pediatric Solution Ever

October 3, 2013

UW Research Expands Bilingual Language Program for Babies

January 24, 2020

MEDNAX Launches Audiology Institute

September 14, 2018

Musical Training Offsets Some Academic Achievement Gaps

August 13, 2014

Recent Posts

- Widex Devices Honored by 2024 Red Dot Design Awards

- FDA Clears Lowering Age Requirement of Cochlear Device

- Soundwave Hearing Launches Streaming-Enabled Self-Fitting OTC Hearing Aids

- Phone Captioning App Improves Communication for Users with Hearing Loss

- Researchers Detail Receptor Protein’s Impact on Hearing Loss Intervention

- HearUSA and AAA Launch Scholarship to Support Future Audiologists

Students with hearing loss get a raw deal: a South African case study

Researcher , Cape Peninsula University of Technology

Professor, Stellenbosch University

Disclosure statement

Dr Diane Bell is affiliated with the Carel du Toit Trust, an NPO in Cape Town.

Estelle Swart does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Cape Peninsula University of Technology and Stellenbosch University provide funding as partners of The Conversation AFRICA.

View all partners

Hearing loss is the fourth highest cause of disability globally. The World Health Organisation estimates that there are currently 466 million people with a disabling hearing loss. Two thirds live in low and middle income countries.

In the UK , 2.33% of students with a disability disclosed being deaf (using sign language) or hard of hearing. In Australia , students with a hearing loss comprise of about 10% of the cohort of students with disabilities.

Studies show that up to 75% of students with a hearing loss who do manage to enter higher education don’t graduate . Those who do are often excluded from entering professions.

These global trends are also relevant in South Africa where universities are accepting and registering students with mild, moderate and severe hearing loss, but are failing to provide them with the necessary academic support, or accessible and inclusive curricula.

Statistics about the numbers of university students who have disclosed disabilities, and more specifically hearing loss, aren’t readily available. But, what we do know is that students who are hard of hearing are being granted access to university increasingly, yet they remain under supported. This often results in poor academic outcomes.

Generally, there is a lack of research about students using hearing technology and those who use spoken language. Not much is known about their educational experiences, the teaching and learning support provided to them and their teaching and learning needs. Very little is known about how they cope with academic live.

We did research to explore the teaching and learning experiences of students with hearing impairments at university and the daily barriers they face. We also provided suggestions on how to improve teaching and learning, and how to promote curricula transformation.

The findings

Our findings showed that teaching practices at the university we used for the case study were not inclusive and that curricula were largely inflexible. We selected this university for our study because it had a relatively large number of students with hearing impairments. Although this research explored the experiences of students with hearing impairments at one university, these findings can be generalised across higher education institutions throughout South Africa.

Our study found that reasonable academic adjustments, such as strategies to minimise or remove the effects of a disability to enable learning, were extremely limited. This means that these students didn’t have access and equal opportunity to participate in all the university’s activities.

Secondly, the support services offered at the university to students with hearing impairments were inadequate. Often, the students didn’t know what support was available to them. And even where it was in place the support didn’t meet the unique needs of the students.

The third finding showed that all hard of hearing students at the university experienced a significant number of learning barriers. These included:

Difficulty following class discussions due to high levels of background noise and poor acoustics, especially in large venues.

Inaccessible teaching practices, such as when the lecturer talks while turning his/ her back to write on the white board or chalkboard or showing videos without subtitles.

Inability to hear or lip-read, especially when lecturers switched between two languages or rapidly changed topics without warning.

Poor lighting when using a data/ video projector because students with hearing impairments weren’t able to lip-read.

Some attempts had been made by the university to be more inclusive. But the students still felt inadequately supported in terms of their unique learning and communication needs.

Moreover, students with disabilities in higher education remain marginalised and insufficiently supported. This interferes with their human rights despite progressive legislative framework in South Africa and the noble commitments to right the wrongs of the past.

Recommendations

The participants in the study made a number of recommendations . These included:

University lecturers must receive training around the principles of universal design for learning and knowledge in relation to hearing loss, and how best to support students with a hearing disabilities.

Support should be tailored to address the individualised need of students.

Large teaching venues should be fitted with good quality audio equipment such as microphones.

Induction loop systems should be installed in larger teaching venues. These systems transmit an audio signal directly into hearing aids/ speech processors through a magnetic field. This reduces background noise, competing sounds and other acoustic distortions that reduce clarity of sound.

A compulsory module on diversity, disability and inclusion should be offered in every course at a first year level.

Unless there is a cultural and attitudinal change at universities, and unless strategies are put into place to support hard of hearing students, they will continue to experience significant barriers to learning. These will have a negative effect on not only their educational experience but also their academic success.

A call to action is being made for university administrators, disability support units and lecturers to provide adequate and appropriate support to ensure equitable access to learning and thus a fair chance of academic success.

- Higher education

- Hearing loss

- Hearing aids

- Inclusive education

- Academic life

Senior Lecturer - Earth System Science

Associate Director, Operational Planning

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Deputy Social Media Producer

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

A case study of interventions to facilitate learning for pupils with hearing impairment in Tanzania

Affiliations.

- 1 Digital Department, SINTEF, Trondheim, Norway.

- 2 Department of Neuromedicine and Movement Science, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway.

- 3 Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Lovisenberg Diaconal Hospital, Oslo, Norway.

- 4 Department of Psychology and Special Education, Faculty of Education, Open University of Tanzania, Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania.

- 5 Department of Hearing Impairment, Patandi College of Special Needs and Inclusive Setting, Arusha, Tanzania.

- PMID: 36483846

- PMCID: PMC9724067

- DOI: 10.4102/ajod.v11i0.974

Background: Hearing is essential for learning in school, and untreated hearing loss may hinder quality education and equal opportunities. Detection of children with hearing loss is the first step in improving the learning situation, but effective interventions must also be provided. Hearing aids can provide great benefit for children with hearing impairment, but this may not be a realistic alternative in many low- and middle-income countries because of the shortage of hearing aids and hearing care service providers.

Objective: In this study, alternative solutions were tested to investigate the potential to improve the learning situation for children with hearing impairment.

Method: Two technical solutions (a personal amplifier with and without remote microphone) were tested, in addition to an approach where the children with hearing impairment were moved closer to the teacher. A Swahili speech-in-noise test was developed and used to assess the effect of the interventions.

Results: The personal sound amplifier with wireless transmission of sound from the teacher to the child gave the best results in the speech-in-noise test. The amplifier with directive microphone had limited effect and was outperformed by the intervention where the child was moved closer to the teacher.

Conclusion: This study, although small in sample size, showed that personal amplification with directive microphones did little to assist children with hearing impairment. It also indicated that simple actions can be used to improve the learning situation for children with hearing impairment but that the context (e.g. room acoustical parameters) must be taken into account when implementing interventions.

Contribution: The study gives insight into how to improve the learning situation for school children with hearing impairment and raises concerns about some of the known technical solutions currently being used.

Keywords: hearing impairment; hearing interventions; personal sound amplification system; school children; speech-in-noise test.

© 2022. The Authors.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Arch Public Health

- PMC10664265

Exploring the health literacy status of people with hearing impairment: a systematic review

Zhaoyan piao.

1 College of Pharmacy, Yonsei Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Yonsei University, 162-1 Songdo-Dong, Yeonsu-Gu, Incheon, Republic of Korea

Yeongrok Mun

2 College of Pharmacy, Ajou University, Suwon, Gyeonggi-Do Republic of Korea

Associated Data

Not applicable.

People with hearing impairment have many problems with healthcare use, which is associated with health literacy. Research on health literacy is less focused on people with hearing impairments. This research aimed to explore the levels of health literacy in people with hearing impairment, find the barriers to health literacy, and summarize methods for improving health literacy.

A systematic review was conducted using three databases (PubMed, Cochrane, and Embase) to search the relevant articles and analyze them. The studies were selected using pre-defined inclusion/exclusion criteria in two steps: first, selection by examining the title and abstract; and second, after reading the study in full. The Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for Nonrandomized Studies (RoBANS) was used to assess the quality of the articles.

Twenty-nine studies were synthesized qualitatively. Individuals with hearing impairment were found to have lower health literacy, when compared to those without impairment, which can lead to a higher medical cost. Most of the people with hearing impairment faced barriers to obtaining health-related information and found it difficult to communicate with healthcare providers. To improve their health literacy, it is essential to explore new ways of accessing health information and improving the relationship between patients and healthcare providers.

Conclusions

Our findings show that people with hearing impairment have lower health literacy than those without. This suggests that developing new technology and policies for people with hearing impairment is necessary not to mention promoting provision of information via sign language.

Trial registration

OSF: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/V6UGW . PROSPERO ID: CRD42023395556.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13690-023-01216-x.

Introduction

The term health literacy has come to represent a variety of meanings as research in related fields intensified [ 1 ]. “The cognitive and social skills that determine the individuals’ motivation and ability to gain access to, understand, and use information in ways that promote and maintain good health” is referred to as health literacy in the second edition of the WHO Health Promotion Glossary [ 2 ] published in 1998. In 1999, the American Medical Association’s Ad Hoc Committee on Health Literacy [ 3 ], defined health literacy as a “constellation of skills, including the ability to perform basic reading and numerical tasks required to function in the health care environment,” including the “ability to read and comprehend prescription bottles, appointment slips, and other essential health-related materials.” The Institute of Medicine (IOM) [ 4 ] decided to use the definition adopted by Healthy People 2010 [ 5 ]thus: “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions” [ 6 ]. This concept includes many scenarios in which individuals may encounter and interact with health concerns; nonetheless, all the above-mentioned definitions attempt to characterize health literacy as a problem of individual ability and competence [ 4 ].

Health literacy is influenced by many factors, including social and personal factors [ 7 ], while indirectly impacting health outcomes by changing the status of the relationship between health care providers and patients. Hearing is a factor that influences the level of health literacy, which is important for accessing, understanding, judging, and using health information appropriately. Therefore, it is necessary to objectively explore the association between health literacy and hearing impairment to achieve better health outcomes among people with hearing impairment. Previous reviews looked into the capacity of cancer education to promote health literacy in patients with hearing difficulties [ 8 , 9 ], but the focus was confined to cancer-related health literacy. In our study, health literacy was not limited to cancer-related but also to other health domains, and we summarized the methods that can improve health literacy except education. In this study, we conducted a comprehensive literature review on the health literacy of people with hearing impairment to understand the level and status of health literacy in persons with hearing loss, outline the challenges and concerns of individuals with hearing disabilities, and propose strategies to improve health information transmission.

Search strategy and data source

We conducted the systematic review according to the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA). We extracted, analyzed, and integrated research papers found suitable as per the selection criteria. After searching three global search engines, we found there was no literature about both health literacy and hearing disability before 2000, the data search and analysis on research papers published in international journals were conducted from January 2000 to December 2021. We used three global search engines—including PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Embase Emtree—and MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms. The applicability of the subject terms for this search is only guaranteed to be valid until July 5, 2022—Additional file 1 describes the specific literature search methods in the three databases.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Of the retrieved papers, duplicates were excluded using Endnote 20.3 (Bld 16073). We selected the corresponding literature using key questions prepared in the form of Participants, Interventions, Comparisons, Outcomes, Timing, Settings, Study Design (PICOTS-SD)—that added timing, settings, and study design to the PICO (Participants, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) framework [ 10 ]. The key questions used are listed in Additional file 2 . Two authors independently screened papers for relevance to this study by applying the literature selection and exclusion criteria described in Table Table1. 1 . We selected studies that were relevant both to people with hearing impairment and health literacy and published between 2000 and 2021. Meanwhile, we had five exclusion criteria, including requirements for the topic of the study, population, year of publication, language of publication, and originality. We excluded papers using title and abstract and added manual searches using single specific terms, such as "hearing disability," to find relevant articles.

Data extraction

As shown in the Figure, we initially gathered 163 publications after deleting duplicates. After further exclusion by abstract, title, and full text, 17 articles remained, and with the addition of 12 articles from the manual search, 29 articles were finally selected for the study (Fig. (Fig.1 1 ).

PRISMA flow diagram

Assessment of the risk of bias for the studies

We used the Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for Nonrandomized Studies (RoBANS) to evaluate the quality of the selected studies. RoBANS contains six domains, including selection of participants, confounding variables, measurement of exposure, blinding of the outcome assessments, incomplete outcome data, and selective outcome reporting. For each domain, the bias risk was classified as “low,” “high,” or “unclear” [ 11 ]. According to Kim et al. [ 11 ], the total bias is evaluated by three relatively more important domains (selection of participants, confounding variables, and incomplete outcome data) out of the six, and if more than two of the three have the same bias—such as “low”—then the total bias is “low.” If the three domains have different biases, then the total bias is “unclear.” Assessment of bias was evaluated by two authors individually, but in case of disagreement, we invited another author to co [ 12 , 13 ].

Analysis method

Due to the diversity of the literature in terms of populations, settings, interventions, and outcomes, it was not possible to consolidate the results quantitatively. Alternatively, we collated the main components of the literature and analyzed the key themes between the selected papers, thus establishing commonalities and differences. The papers were collated in terms of countries, characteristics of subjects, study aims, methodology, main findings, and tools for measure health literacy. The results on health literacy status were separately collated for the characteristics of health literacy problems, difference in health literacy levels among people with hearing disabilities, barriers against health literacy, and the ways of improving health literacy.

The final collected papers were categorized into quantitative and qualitative research based on the research method used. Taking the unknown into consideration, the research was classified as quantitative if objective generalized results could be obtained using health literacy tests. If observation and interview methods were conducted to investigate the phenomenon, the research was classified as qualitative.

This study collated the results of the research based on the following. First, the characteristics of the included studies were examined. Second, what is the level of health literacy for people with hearing impairment compared to those without such impairment? Third, what are the barriers to health literacy for people with hearing impairment? Fourth, how does the level of health literacy for the hearing-impaired lead to health management? Fifth, what are the ways to improve the health literacy of people with hearing impairment?

Characteristics of included studies and results of bias assessment

In general, most of our selected papers had low bias and were of high quality. As shown in Additional file 3 , the risk of bias was rated as “low” for 25 of the 29 papers, “high” for 2 papers, and “uncertain” for 2 papers. Twenty of the 26 papers were from the United States, one involved both Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, one was from both South Africa and China, and the other seven from Canada, South Africa, Germany, Turkey, Nigeria, Australia, and Swaziland. The sample size varied from 7 to 19,223 people, with 24 studies having fewer than 1,000 and 4 papers having more than 10,000. There were 22 quantitative studies and 7 qualitative studies. Four of the studies involved teenagers, while the others were conducted on adults. Four of the studies included just female hearing-impaired participants, while none involved only male hearing-impaired participants. Twenty-two studies were conducted by survey, three by interview, and four by focus groups (Table (Table2 2 ).

Characteristics of study included

Tools for measuring health literacy

The most used assessment tools in the articles we searched were the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM), Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA), Newest Vital Sign (NVS), Health Literacy Skills Instrument (HLSI), European Health Literacy Survey (HLS-EU-Q47), and Brief Health Literacy Screen (BHLS). Some studies also used their own developed questionnaires. Table Table3 3 shows some of the sources of health literacy measurement tools. All the tools used for measuring the health literacy of people with hearing impairment classify the level of health literacy into two to four degrees, and all have been tested for validity.

As follows, we have summarized the findings of each article according to those listed in Table Table4. 4 . Although each article does not show the same content due to differences in the purpose of the study, we can still summarize based on what is available.

Current status of health literacy among people with hearing impairment and improvement methods

Health literacy levels of people with hearing impairment

The prevalence of inadequate health literacy among people with hearing impairment is high. Mckee et al. [ 27 ] conducted a study with 166 participants with hearing loss and 239 hearing participants without, and showed that 48% of participants with hearing loss have inadequate health literacy and were 6.9 times more likely than hearing people to have poor health literacy. Pollard et al. [ 19 ] investigated health-related vocabulary knowledge in a sample of adults through a modified REALM and found that 32% of people with hearing loss received scores comparable to low health literacy scores; all of their study participants were people with hearing disabilities and 80.8% obtained a college degree, implying that even people with hearing disabilities with high or average levels of education may be at risk of lower health literacy. Tolisano et al. [ 38 ] found ratings of participants’ hearing were categorized into four grades, and patients with poorer hearing grades C and D had lower health literacy scores measured with the BHLS than those with grades A and B (BHLS score in the range of 11.6–13.6). Wells et al. [ 39 ] divided 19,223 older adults into five groups based on their self-reported hearing disability level, including those with severe unaided hearing loss, severe with hearing aid use, mild with assistance, mild without assistance, and no hearing loss. Of these, the unaided mild, aided severe and unaided severe hearing loss groups showed lower health literacy than the other groups, although this connection diminished with the use of hearing aids.

The barriers to health literacy for people with hearing impairment

Among the people with hearing impairment, there is a lack of knowledge and misconceptions about diseases, such as cervical cancer [ 18 , 23 ], ovarian cancer [ 25 ], breast cancer [ 24 ], HIV/AIDS [ 17 ], COVID-19 [ 41 ], and diabetes [ 35 ]. People with hearing impairment also had limited access to health information and encounter difficulties in seeking health information [ 49 ]. Several studies were conducted on a hearing-impaired group and a control group to compare their knowledge on cervical, ovarian, and breast cancers after listening to a graphic-rich video in American Sign Language with English subtitles regarding cancer [ 18 , 23 , 25 ]. The studies obtained similar results; women in the control group performed better before watching the video, while following the intervention, both groups’ knowledge on relevant tumors improved significantly [ 18 , 23 – 25 ]. These findings imply that the health literacy of people with hearing impairment can be improved if there are more effective ways to expose them to health information and provide more access to it.

People with hearing impairment tend to visit their doctors more often than those with good hearing, but they can have more difficulty communicating with professionals [ 50 ], which is consistent with the findings of a survey of American Sign Language (ASL) interpreters [ 51 ]. In Stevens et al.’s study [ 36 ], more than 90% of people with hearing impairment reported problems with poorly communicated information and communication difficulties when their name was called with the presenter’s back being turned, as well as communication over the telephone, which can affect the quality of patient care, satisfaction, and health outcomes. According to Steinberg et al. [ 15 ], adults with hearing impairment who used ASL were distrustful, fearful, and frustrated with medical care and believed that if doctors could communicate with them in sign language or with a live interpreter, it would help them establish good communication with the doctor and improve their satisfaction with the medical service. Similar communication challenges were observed among teenagers with hearing disabilities [ 37 ], with 55.7% preferring written prescriptions or care procedures and 87.5% preferring sign language communication. A study [ 28 ] has shown that when pharmacists lack patience or understanding of the real needs of people with hearing impairment when they seek medication care, the bond between them can be weakened and, in turn, can affect the safe administration of medication to patients. All of these findings illustrate the importance of effective communication between patients and doctors about medication, treatment, and health outcomes.

The impact of health literacy levels on health management among people with hearing impairment

People with both hearing impairment and limited health literacy were more likely to have higher medical costs [ 39 ]. In addition, people with hearing loss have very limited awareness of health insurance and have little access to the related information [ 40 ]. Willink et al. [ 40 ] discovered that Medicare participants who had a little or a lot of hearing impairment were 18% and 25%, respectively, more likely to report having difficulty understanding Medicare than those who did not have hearing problems. Approximately 20% of Medicare enrollees with hearing loss reported that their hearing disability made it hard to find information about Medicare. This also implies that methods to assist people with hearing loss in understanding Medicare should be consistently developed.

Methods for improving health literacy

Online education can help enhance the health knowledge of people with hearing impairment as well as their capacity to seek health information on the internet [ 14 , 18 , 23 , 25 , 33 ]. Palmer et al. [ 33 ] reported that the bilingual modality via both the signer and closed captioning provided better access to cancer genetics information for less-educated ASL users compared to the monolingual modality. This study supports that materials prepared with sign language and extra captioning and graphics improve the sign language user’s understanding and satisfaction. Short Message Service (SMS) can help people with hearing loss become more aware of hypertension and healthy living. However, because of the special demands and preferences of sign language users, SMS services must be investigated further to fulfill the needs of the hearing impaired. Haricharan et al. [ 32 ] suggested numerous strategies to improve SMS campaigns for people with hearing disabilities, including the use of images, combination of SMS with signed drama, use of 'signed’ SMS, and linkage of SMS campaigns to interactive communication services.

Additionally, communication issues between people with hearing impairment and health care providers need to be addressed. Most people that are hard-of-hearing in the survey mentioned difficulties in communicating with doctors, the obscurity of some terminology, and even misunderstandings [ 36 ]. They hoped to communicate with the doctor in sign language or have a sign language interpreter on-site to help them speak with their doctor, which would increase their satisfaction with health services, strengthen the doctor-patient relationship, and improve their health outcomes [ 15 , 36 , 37 ]. To facilitate communication between patients with hearing impairments and healthcare professionals, it is essential to pre-educate healthcare professionals about people with hearing loss [ 20 ]. In Hoang et al.’s study, medical students were divided into two groups based on whether they had undertaken a community education program on hearing impairment. When knowledge of the overall “deaf culture “ in the healthcare setting was assessed, the summary scores varied widely—26.9 for those who had completed the education program, 17.1 for the medical school faculty, and 13.8 for those who had not completed the education program [ 20 ]. Overall, the faculty members scored similarly to medical students who did not complete the educational program on issues particularly relevant to interactions with hearing loss patients. This research proved that primary education is crucial in interacting with deaf patients, regardless of clinical expertise [ 20 ].

This study assessed the existing literature relating to the health literacy of people with hearing impairment. There are some common observations showing that people with hearing impairment have low health literacy and have difficulties communicating with health providers and understanding—and often misunderstanding—when seeking medical services [ 15 ]. They also have limited sources of relevant health information, incomplete knowledge of diseases, health insurance, and even misunderstandings of the same [ 35 , 40 , 41 , 49 ]. In addition, participants were under-informed about the palliative care services available to them, and health providers were unknown about the deaf culture [ 22 ].

Of our selected literature, 25 were evaluated as having a “low” risk of bias because most studies used instruments to measure health literacy or conducted case–control group studies. Two were deemed to be at high risk of bias, owing to some confounding variables and missing data in the research, which influenced the results. The other two articles were judged to be having an “unclear” risk of bias due to the complete inconsistency of the three main domains. This showed that for the people with hearing impairment, high-quality research has been conducted as enough comprehensive factors were considered in the study to minimize possible bias.

Few studies have investigated health information sources for people with hearing impairment. Smith et al. (2015) interviewed hearing loss adolescents who used sign language and identified five main sources of cardiovascular health information, including family, health education teachers, health care providers, print, and informal sources. They suggested that communal funds be used to conduct appropriate health surveys and identify health education programs, enhance interpreter education, and distribute information using social media. All three authors of this literature [ 29 ] are also people with hearing disabilities; thus, they researched a group to which they belong and understand, which is one way that future research on people with disabilities could be conducted—by researchers who know enough about particular groups.

Increased health literacy through conversational means is crucial, and because of the influence of independence from their families, college students who lose their hearing often rely on friends to get health information and education [ 34 ]. Mutual sign language education with friends, discussion, and participation in these early social discussions can improve overall health knowledge. Recent improvements in online information technology, social networks that enable the gathering of sign language users, and frequent gatherings through online virtual meetings can provide them a space for dialogues, potentially sharing their most recent health information [ 34 ]. Another option is to employ SMS functionality, which in 2015 had a nationwide penetration rate of 85.67% in South Korea; this value will reach 97.4% by 2025 [ 52 ]. We also anticipate that text messaging will become increasingly crucial as more cellphone apps and technology are developed for individuals with disabilities [ 53 , 54 ]. Haricharan et al. [ 32 ] previously investigated sending regular text messages to boost health information and hypertension awareness among people with impairments. The content contained 20 well-designed hypertension messages, 57 food habits, methods to avoid hypertension through healthy living—such as exercise—and four activities [ 32 ]. Although some literature recommend the use of written materials [ 31 , 36 , 37 ], we must recognize that people with hearing impairment who speak sign language as their first language frequently struggle to interpret written texts and lack literacy in this area [ 15 , 55 ]. This is especially true for people who are more likely to have a low level of education [ 33 ]. In Korea, the hearing handicapped commonly employ Korean Sign Language, lip-synthesis, and notes, among other means [ 55 ]. According to the 2017 Korean Sign Language Use Survey, 69.3% of people with hearing loss use sign language as their primary form of communication, but only 30.5% fully understand it [ 56 ]. Hence, using textual material to spread health messages in Korea may be a good option.

In summary, our literature review indicate several currently feasible ways to improve the health literacy of people with hearing impairments: health literacy education for people with hearing impairments, hearing disability-related education for healthcare professionals to help understand better the needs of people with hearing impairments, and popularization of the use of smartphones (e.g., SMS). In addition, if we can analyze subgroups of people with hearing impairment by conditions such as whether they use hearing aids or not and whether they know sign language or not in subsequent studies, that would help to target people with hearing impairment to improve their health literacy.

There are several limitations to this study. First, it is hard to generalize the selected literature as there were variations by countries in selection criteria for people with hearing impairments, age distribution and number of participants, and methods and tools used. Second, it was not possible to compare the selected foreign studies with the Korean results as there are no national studies on health literacy among people with hearing impairment. Third, although the literature we collected was published over a wide time period, from 2000 to 2021, there are not many studies on health literacy among people with hearing impairment. Each paper defined low health literacy differently and, to our knowledge, there is not a clear standard at present. Paul et al. [ 57 ] summarized 43 different health literacy instruments and illustrated that the quality of these instruments varied considerably according to their psychometric properties. Regardless, overall, the literature is of high quality and contains information on the low health literacy of people with hearing impairment, dilemmas faced in the healthcare setting, limited sources of medical information, and some feasible ways to improve it. These existing relevant articles can inform about the current state of health literacy among people with hearing loss and ways of improving the health literacy of people with hearing impairment.

People with hearing impairment have shown a willingness to seek out and learn about health information. However, because of the complex terminology, a lack of easily available health information resources and illustrations by handicap type has been discovered. The recent continuous development of technology for people with disabilities and easy access to smartphones have correspondingly provided more and varied options for people with disabilities to receive health information. This suggests that developing new technology and policies for people with hearing impairment is necessary not to mention promoting provision of information via sign language. For instance, enforcement policies would be required for the existing app technologies in the uploading of health information for various chronic diseases, such that deafness characteristics are taken into consideration and people subscribe only to the information they require.

Acknowledgements

Abbreviations, authors’ contributions.

ZYP searched the articles and was a major contributor to writing the manuscript, HBL and YRM searched literature and tabulation, HKL revised the manuscript, and EH customized the research plan and participated in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

This study was conducted with the support of the National Research Foundation of Korea (grant number: 2022R1A2B5B0100125311).

Availability of data and materials

Declarations.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Browse Econ Literature

- Working papers

- Software components

- Book chapters

- JEL classification

More features

- Subscribe to new research

RePEc Biblio

Author registration.

- Economics Virtual Seminar Calendar NEW!

Challenges Faced by Learners with Hearing Impairments in a Special School Environment: A Case Study of Embangweni Primary School for the Deaf, Mzimba District, Malawi

- Author & abstract

- Related works & more

Corrections

- Sphiwe Wezzie Khomera

- Moses Fayiah

- Simeon Gwayi

Suggested Citation

Download full text from publisher.

Follow serials, authors, keywords & more

Public profiles for Economics researchers

Various research rankings in Economics

RePEc Genealogy

Who was a student of whom, using RePEc

Curated articles & papers on economics topics

Upload your paper to be listed on RePEc and IDEAS

New papers by email

Subscribe to new additions to RePEc

EconAcademics

Blog aggregator for economics research

Cases of plagiarism in Economics

About RePEc

Initiative for open bibliographies in Economics

News about RePEc

Questions about IDEAS and RePEc

RePEc volunteers

Participating archives

Publishers indexing in RePEc

Privacy statement

Found an error or omission?

Opportunities to help RePEc

Get papers listed

Have your research listed on RePEc

Open a RePEc archive

Have your institution's/publisher's output listed on RePEc

Get RePEc data

Use data assembled by RePEc

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Academic Challenges of Students with Hearing Impairment (SHIs) in Ghana

Related Papers

Brighton Kumatongo

This paper is a literature review and discussion of the barriers and facilitators of academic performance for learners with hearing impairments in Zambia. This review is necessary to put into perspective factors that may affect the attainment of sustainable development goals particularly goal number 4 on inclusiveness, equity, and lifelong learning. Learners with hearing impairments experience various learning barriers in Zambian schools. Education for learners with hearing impairments in mainstream institutions requires educators to put in place measures that can facilitate learning and academic performance. Adaptation of curriculum, effective use of assistive technology, and use of appropriate modes of communication are some of the prerequisites to the good academic performance of deaf students. In this article, we shall focus on some of the facilitators to the academic performance of learners with hearing impairments.

Adedayo Olaosun

Background:-Most students with deafness have some difficulty with academic achievement, especially with reading and mathematics. However, the range of intelligence levels of students with deafness does not differ from the range in their hearing counterparts. Academic performance must not be equated with intelligence. Most children who are deaf have normal intellectual capacity and it has been repeatedly demonstrated that their scores on non-verbal intelligence tests are approximately the same as those of the general population. Deafness imposes no limitations on the cognitive capabilities of individuals. The problems that deaf students often experience in academics and adjustment may be largely attributed to a bad fit between their perceptual abilities and the demands of spoken and written English. Several studies have suggested that one of the most potent predictors of academic achievement for the students with deafness is the amount of personalized and specialized attention they r...

Simeon Gwayi

Article History Received: 26 March 2020 Revised: 1 May 2020 Accepted: 29 May 2020 Published: 22 June 2020

European Journal of Physical Education and Sport Science

joseph mandyata

Jennifer Muiti Mwenda

One is learning when he is increasing the probability of making a correct response to a given stimulus. One has learned only when he is capable of giving an appropriate response. The 8.4.4 Curriculum of Education is followed in education of hearing impaired in special schools and units. Hence just as the case in regular education, the hearing impaired are expected to learn and perform well academically. Statement of the Problem was that children with hearing impairments are typically not educationally managed well to permit them compete satisfactorily in the society. The study aimed at investigating factors hindering effective learning of children who are hearing impaired in one special primary school and units in Meru North District in Eastern Province of Kenya. Education being a basic human right, children who are hearing impaired successful learning, needs to be emphasized and factors hindering it to be addressed. Literature was reviewed on trends in the education of children who...

QUEST JOURNALS

This study investigated the influence of teachers' instructional strategies on academic performance of students with hearing impairment in inclusive classroom in AkwaIbom State. Two purposes were postulated to guide the study and two null hypotheses were postulated to guide the study. Descriptive survey research design was employed and used for this study. The population of the study was 72students' with hearing impairment. A sample size of 72students' with hearing impairment selected through purposive sampling technique. Teachers' Instructional Strategies Questionnaire` (TISQ) was used to elicit Academic Performance in core two subjects (English Language and Mathematics). The instrument validity and reliability was determined. Dependent t-test was used to test the null hypotheses at 0.05 level of significance. The findings showed that there is a significant influence of teachers' instructional strategies on academic performance of student with hearing impairment in inclusive classroom in AkwaIbom State. Based on the findings of the study, it was recommended among others that seminars and conferences should be organized by teacher educators for teachers from time to time to keep them abreast of different teaching strategies which they would use in implementing school curriculum.

res publication

accounts ziraf

Difficulty in hearing is recognized as one of factors which deter communication between people involved in conversation. Its invisibility in the learning process particularly in higher Institutions makes easy for teachers to forget about it and treat the students as if they are all normal. Mixed research methods were employed for this study whereas both qualitative and quantitative data were collected from two selected government higher learning institutions. Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) programme was used for analyzing quantitative data, and content analysis was used for analyzing qualitative data. The study revealed that admission systems in the surveyed institutions were not helpful in identifying and planning for the needs of Student with Hearing Impairment (SWHI). As a result, majority of lecturers and instructors were not aware of the presence of SWHI in their institutions. Furthermore, none of the surveyed institutions had either instructors or translators with skills to teach SWHI. Moreover, no extra coaching was provided to SWHI. None of the surveyed institutions had set future plans for easing learning and teaching environment to SWHI. The study concludes that lack of lecturers with special skills to

Jurnal Humaniora

dawit Negassa

The purpose of this study was to investigate the current experiences of deaf children in upper primary, secondary and preparatory schools in Gondar City Administration, Ethiopia. A phenomenological study design with qualitative inquiry approach was used. The main tool used for the study was a semi-structured interview guide, which was developed out of comprehensive review of literature for data collection. Out of the thirty deaf children in the study (26 children from grades 5 to 8 and four children from grades 9 to 12), nine were selected through purposive and available sampling techniques from upper primary, secondary and preparatory schools respectively. The data collected were thematically analyzed though the academic dimension points. Results indicated that the deaf children were not academically included at par with the other students, though they were able to receive support from their peers and were active participants in extra-curricular activities. The deaf children were f...

Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education

Patricia Reece

IOSR Journals

Here's why weight loss based on a calorie deficit diet won't work forever, according to science

Whether you're shedding pounds with the help of effective new medicines, slimming down after weight loss surgery or cutting calories and adding exercise, there will come a day when the numbers on the scale stop going down, and you hit the dreaded weight loss plateau.

In a recent study, Kevin Hall, a researcher at the National Institutes of Health who specializes in measuring metabolism and weight change, looked at when weight loss typically stops depending on the method people were using to drop pounds. He broke down the plateau into mathematical models using data from high-quality clinical trials of different ways to lose weight to understand why people stop losing when they do. The study published Monday in the journal Obesity.

What he found is that part of the reason that gastric bypass surgery and new weight loss drugs such as Wegovy and Zepbound are so effective is because they double the time it takes to hit a plateau. People are able to lose weight for longer than by cutting calories alone.

The body regulates weight by trying to maintain an equilibrium between the calories we eat and the calories we burn. When we expend or cut calories, and start burning our stored energy, appetite kicks in to tell us to eat more. Hall's studies have shown that the more weight a person loses, the stronger appetite becomes until it counteracts, and sometimes completely undoes, all the hard work they've done to lose in the first place.

This feedback mechanism was valuable for our hunter-gatherer ancestors, but it doesn't work so well for modern humans who have easy access to energy dense ultra-processed foods.

Plateaus at different points

To study the trajectory of weight loss using calorie restriction alone, Hall modeled the observed weight loss in the CALERIE study, which randomly assigned 238 adults to either two years of following a 25% calorie restriction diet or eating as they normally would. The study ran from 2007 to 2010 and was sponsored by the NIH. The adults in the group that cut calories lost on average about 16 pounds. The group that followed their normal diets gained about 2 pounds.

Though the people who took part in the CALERIE study kept up their efforts for two years, their weight loss stopped somewhere around the 12-month mark, as their appetite ramped up to counteract it.

Hall notes that his study deals in averages. The timing of a weight loss plateau may vary for individuals.

Hall's model predicted that in order to achieve the weight loss reported in that study, people whose diets started at 2,500 calories per day had to cut just over 800 calories a day. Their bodies responded by prompting them to add to their daily caloric intake an estimated 83 calories for every kilogram of weight they lost.

A kilogram is about 2.2 pounds. For every 2.2 pounds of weight participants lost, their appetite responded by asking for 83 more calories a day. The average weight loss reported in the study was 7.5 kilograms, or 16 pounds, which would mean that at their lowest weights, they were feeling the need to eat 622 more calories a day more than before they started losing weight.

But they weren't actually eating 622 more calories a day - instead, that's the extra amount of appetite they were feeling, even as they're putting in the same amount of effort as they did in the beginning to cut 800 calories a day.

At the end of the study, Hall said, participants were working as hard as they did in the beginning to resist food, but only managing to cut about 200 calories a day instead of the 800 they were shooting for. That brought their weight loss to a halt.

Dr. Christopher Gardner, director of nutrition studies at the Stanford Prevention Research Center, previously told CNN this feedback mechanism is why weight loss gets harder the more you lose.

"Because people's bodies react to that, and they become more metabolically efficient. And so the same calorie deficit won't do it for you. That's why people's weight loss starts to plateau," Gardner told CNN Chief Medical Correspondent Dr. Sanjay Gupta in the "Chasing Life" podcast.

In Hall's model, as people in the CALERIE study lost more weight, their appetites roared back, and around the 12-month mark, they stopped losing weight.

The drugs semaglutide and tirzepatide, which mimic gut hormones to help people lose weight, prompted greater caloric restriction. For semaglutide, the active ingredient in Wegovy, Hall's model predicted that as people gradually increased their dose in the study, they went from eating about 600 fewer calories a day to 1,300 fewer calories a day at the highest dose. For tirzepatide, the active ingredient in Zepbound, the number of calories people cut from their diet each day increased from 830 on the lowest dose to 1,560 on the highest does tested in the study.

But crucially, the drugs didn't merely have an effect on the number of calories people cut from their diets. They also lowered the number of calories their bodies were prompting them to eat back as they lost weight - in effect, weakening their appetites. For Wegovy, people only wanted to eat back about 49 calories daily for every kilogram of weight they lost. For Zepbound, that number was 48. By cutting their appetites by about half, they were able to keep losing weight for longer, an extra year on average compared with calorie restriction alone. People taking weight loss drugs generally stopped losing weight around the two-year mark.

Weight loss surgery had the strongest effect of all, prompting people to cut about 3,600 calories from their diets each day, and only eat back 58 calories for every kilogram they'd lost every day. People who'd had weight loss surgery also had another year before their reached their plateau, suggesting that the surgery turned down their appetite significantly.

More interventions might be necessary

Hall says there are several important insights from this study. The first, he said, is drugs such as Wegovy and Zepbound and interventions like weight loss surgery, lengthen the time it takes to hit a plateau, but they don't stop it from happening completely.

"What's happening is that they still experience an increase in appetite, the more weight that they lose," Hall said.

"If they had no appetite circuit, in other words, the drug just kind of kicked in and their intake stayed at this very low level. It would take many, many years for them to reach a plateau and they would lose, you know, an exorbitant amount of weight," Hall said.

While it may stymie dieters, the appetite feedback circuit is actually a good thing, he said. It would be dangerous if a drug or treatment got rid of appetite entirely. If that happened, a person might stop eating entirely until they died.

Hall said the study also helps to refine some ideas about why people stop losing weight.

For example, one theory has been that weight loss damages metabolism, so people end up burning far fewer calories at rest than when they started and can regain weight very easily.

Hall says metabolism does drop after weight loss, "but not anywhere near the amount that will be required to explain the timing or magnitude of the weight loss plateau," he said.

Hall says the study also seems to disprove the notion that the drugs eventually stop working. "I think that's also incorrect," Hall said.

"Our modeling suggests that the reason for the plateau is because that's the point at which the drugs effect has been matched by the increase in appetite," he said.

Sometimes people hit a plateau well before they've reached their goal weight, which can be extremely frustrating.

Hall said in situations like that, people may have to add interventions to increase their effect.

"Another very common thing now is that people who didn't lose as much weight from bariatric surgery as they thought, will go on one of the GLP-1 receptor agonist so they're adding interventions on top of each other," Hall said.

Whatever route you choose, "a persistent effect is required to maintain the weight loss," Hall said. So it's a good idea to consider whether you can keep doing what you're doing for the long haul.

People who hit a plateau after cutting calories can likely bust through it by restricting calories even further or adding exercise to their routine.

"The whole point here is that whatever you do, you have to keep doing it. And so you've gotta be happy with that lifestyle intervention for the rest of your life. Otherwise, it's not going to have the added benefit," Hall said.

The-CNN-Wire & 2024 Cable News Network, Inc., a Time Warner Company. All rights reserved.

Related Topics

- HEALTH & FITNESS

- WEIGHT LOSS

Weight Loss

Weight loss drug could soon treat types of sleep apnea, drugmaker says

'Oat-zempic' trend 'does not mimic' Ozempic's effects, experts says

Costco begins offering Ozempic prescriptions to some members

Medicare can now cover Wegovy for more senior citizens

Top stories.

'Armed and dangerous' suspect sought connection with CPD cop's murder

- 7 minutes ago

PA parents outraged after middle school student attacked with Stanley

Tenant guilty of landlord's murder, dismemberment on Far North Side

- 35 minutes ago

Bears to unveil plans for new lakefront stadium

Chicago man Jovon Nelson, 24, missing since April 9

- 44 minutes ago

Manhunt underway after Southern California deputy shot in back

- 1 minute ago

Low ice coverage is changing future of Lake Michigan

- 40 minutes ago

5 children taken to hospitals for suspected cannabis overdose

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

has been highlighted prominently. The parents of hearing impaired students were also the part of study and found satisfied with the use of assistive devices for their children. It is divulged that there is a need to reduce the cost of assistive devices to be used by the students with hearing impairment. Key words: Hearing impaired children ...

Helping families help themselves: a case study. When family members of children with hearing loss express concerns about school-related issues to the clinic-based audiologist, we want to respond in a supportive manner, without overstepping our role. The tendency may be to jump in and try to solve the problem for the family.

These case studies—involving real-life teams, patients, students, and families—feature examples of successful IPP collaboration across a variety of settings. Use these examples in the classroom or to inspire an existing IPP team. ... rehabilitation team developed a treatment plan for a 55-year-old man with memory and hearing loss, tinnitus ...

A case study of interventions to facilitate learning for pupils with hearing impairment in Tanzania. ... 2016, ' Functional hearing in the classroom: Assistive listening devices for students with hearing impairment in a mainstream school setting ', International Journal of Audiology 55 (12), 723-729. 10.1080/14992027.2016.1225991 ...

This study explored the untold stories of hearing-impaired students in inclusive Education at Sagay National High School during the 2022-2023. ... This case study provides an overview of current ...

The Hearing Journal: October 2022 - Volume 75 - Issue 10 - p 24,25,26. doi: 10.1097/01.HJ.0000891488.88548.a0. Free. Metrics. If Monica F. Wiser, MA, CCC-A, ruled the world, she would mandate that all in her profession walk a mile in her shoes and experience what it is actually like to be hearing impaired.

Conclusion. This case study demonstrates the following: Students who are deaf or hard of hearing may have differing accommodation needs, and the accommodations may not be the same in all courses for the same student. Accommodation procedures and alternatives must be in place, or there must be a capacity to quickly make arrangements to implement ...

Do a status check As a lecturer you may not be aware that you have a student with a hearing impairment in your class. Many do not disclose or request any special assistance. Inform all your ...

Hearing impairment is a general term used to describe all degrees and types of hearing loss and deafness (Westwood, 2011). Similarly, Paul & Whitelaw (2011) define hearing impairment as a generic term referring to all types, causes, and degrees of hearing loss. Also, according to Andrews, et.al., (2015), hearing impairment is a generic term

Challenges which prevent SHIs from higher academic performance are from different systems of SHIs' environment and the interplay between them and the study recommends that interventions must be directed at the different systems within their environment. Purpose: Several researches have showed that the average academic performances of students with hearing impairment (SHIs) are below that of ...

Figure 2. Follow-up behavioral test of 5-year-old boy. According to the MRI, the cochlea on the right side is normal—which would explain the present DPOAE results. The cochlear branch of the VIIIth Cranial Nerve is completely absent, which would explain the absent ABR result and the profound hearing loss by behavioral testing.

Download Full Case Study & Rubric. An interprofessional practice (IPP) team worked together to assess hearing loss and language skills in a 2-year-old child. The team recommended a cochlear implant and a plan of therapy for language development and listening skills. As a result, the child's expressive vocabulary began showing steady growth.

In the UK, 2.33% of students with a disability disclosed being deaf (using sign language) or hard of hearing. In Australia, students with a hearing loss comprise of about 10% of the cohort of ...

32 Hearing Impairment and the Latin Classroom Experience: A case study of a Year 10 student with a hearing impairment learning Latin dialogue about hearing impairment with other teachers meant that they became more aware of their teaching practice. By opening this dialogue, we consciously use common sense to improve the learning experience.

Students with a hearing impairment may experience difficulty with certain sound frequencies and have difficulties when there is significant background noise. www.iosrjournals.org 69 | Page Challenges faced by Hearing Impaired pupils in learning: A case study of King George VI Memorial Students who were deaf from birth or as the result of ...

The study gives insight into how to improve the learning situation for school children with hearing impairment and raises concerns about some of the known technical solutions currently being used. A case study of interventions to facilitate learning for pupils with hearing impairment in Tanzania Afr J Disabil. 2022 Nov 10; 11:974. doi ...

Students with hearing impairment (aged 18 years and older) who know ASL: S-TOFHLA: Smith ... as having a "low" risk of bias because most studies used instruments to measure health literacy or conducted case-control group studies. Two were deemed to be at high risk of bias, owing to some confounding variables and missing data in the ...

And "It is difficult for Deaf and hearing impaired students to understanding Education means without teacher's assistance" which confirmed the result of Lin, et al., (2013) who found that hearing ...

Email: [email protected]. Abstract: This paper aimed to show the EFL classroom activities for children with hearing. impairment conducted by the teacher, the teacher's consideration in ...

Abstract: Students with Hearing Impairment (HI) are experiencing challenges in most learning institutions of ... Challenges faced by Hearing Impaired pupils in learning: A case study of King George VI Memorial www.iosrjournals.org 70 | Page Students who were deaf from birth or as the result of illness in childhood may lip-read and/or use sign ...

Downloadable! Hearing impairment has been a major disability challenge globally and is considered to a threat to quality education in developing countries like Malawi. This article focuses on the challenges faced by learners with hearing impairments in a special school environment in Malawi. The study was conducted in a selected primary for the deaf in Mzimba District Malawi in 2013.

Institutionally, there are ten basic and two Senior High Schools dedicated to the education of Students www.dcidj.org Vol. 29, No.3, 2017; doi 10.5463/DCID.v29i3.646 129 with Hearing impairment (SHIs) in Ghana. Students with hearing impairment (SHIs) which is used interchangeably with deaf or hard of hearing (D/HH) in this study are described ...

The average weight loss reported in the study was 7.5 kilograms, or 16 pounds, which would mean that at their lowest weights, they were feeling the need to eat 622 more calories a day more than ...