- Request new password

- Create a new account

Introduction to Educational Research

Student resources, chapter summary, chapter 6 • qualitative research methods.

- Qualitative research involves the collection, analysis, and interpretation of narrative data.

- The focus of qualitative research is typically on the quality of a particular activity.

- Holistic description of the phenomenon, setting, or topic of interest is a key characteristic of qualitative research.

- Both qualitative and quantitative research methods are valuable in their own rights.

- When deciding on a research methodology, it is best to begin with a topic of interest or specific question and then select the method that will provide you with the best answer to that question.

- Qualitative research is naturalistic.

- Qualitative research is descriptive

- Qualitative researchers are concerned with process as well as product.

- Qualitative researchers analyze their data inductively.

- Qualitative researchers are primarily concerned with how people make sense and meaning of their lives.

- Although the basic steps are fairly consistent, those used in conducting qualitative research may occur out of sequential order, may overlap, and are sometimes conducted concurrently.

- Identification of the phenomenon to be studied

- Review of the related literature

- Identification and selection of participants

- Collection of data

- Analysis of data

- Generation of research questions

- Additional data collection, analysis, and revision of research questions

- Final interpretation of analyses and development of conclusions

- Many different approaches exist for conducting qualitative research.

- Commonly used qualitative approaches include ethnographic research, narrative research, historical research, grounded theory research, phenomenological research, and case study research.

- Ethnographic research involves the in-depth description and interpretation of shared practices and beliefs of a social group or other community.

- Narrative research is an approach used to convey experiences as they are lived and told by individuals.

- Historical research describes events, occurrences, or settings of the past to better understand them.

- Grounded theory research is used to discover an existing theory or generate a new theory resulting directly from data.

- Phenomenological research is used to describe and interpret experiences or reactions of participants to a specific phenomenon from their individual perspectives.

- Case study research is an in-depth analysis of a single entity, known as a case.

- Ethnography is a research approach used to study human interactions in social settings.

- Ethnographic research focuses on social behavior in natural settings.

- It relies on narrative descriptions made by observers or participants in the group being studied.

- Its perspective is holistic.

- In some studies, research questions may emerge after data collection is well under way.

- Procedures of data analysis involve contextualization within the group, setting, or event being observed.

- A privileged observer, also known as a nonparticipant observer, does not engage in the activities of the group.

- A participant observer actively engages in all activities as a regular member of the group being studied.

- Naturalistic observation is a holistic technique where the researcher must record all pertinent information.

- A strength of ethnographic research is its holistic view of education or personal behavior.

- Concerns about ethnographic research involve the reliability of data and the validity of research conclusions, as well as the generalizability of findings.

- Several forms of narrative research exist; all forms tell stories of lived experiences, but they differ according to perspective, amount of life story told, and theoretical lens.

- A biographical study is a type of narrative research where the researcher records the experiences of another person’s life.

- An autobiographical study also involves the experiences of a person’s life but is told by the individual who is the subject of the study.

- A life history tells the story of an individual’s entire life.

- A personal experience story is a study of an individual’s personal experience related to a single or multiple incidents.

- An oral history is conducted by gathering personal reflections of events and their implications from one or more individuals.

- A key technique used in narrative research is restorying, a process of reorganizing personal information and stories into a format that makes sense for the intended audience.

- During the process of restorying, participants as well as the researcher may experience epiphanies.

- A clear strength of narrative research is its ability to tell detailed stories of people’s lives.

- Narrative research, however, is a lengthy process wherein the researcher must uncover a multitude of details in people’s lives.

Qualitative Research: An Overview

- First Online: 24 April 2019

Cite this chapter

- Yanto Chandra 3 &

- Liang Shang 4

3710 Accesses

5 Citations

Qualitative research is one of the most commonly used types of research and methodology in the social sciences. Unfortunately, qualitative research is commonly misunderstood. In this chapter, we describe and explain the misconceptions surrounding qualitative research enterprise, why researchers need to care about when using qualitative research, the characteristics of qualitative research, and review the paradigms in qualitative research.

- Qualitative research

- Gioia approach

- Yin-Eisenhardt approach

- Langley approach

- Interpretivism

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Qualitative research is defined as the practice used to study things –– individuals and organizations and their reasons, opinions, and motivations, beliefs in their natural settings. It involves an observer (a researcher) who is located in the field , who transforms the world into a series of representations such as fieldnotes, interviews, conversations, photographs, recordings and memos (Denzin and Lincoln 2011 ). Many researchers employ qualitative research for exploratory purpose while others use it for ‘quasi’ theory testing approach. Qualitative research is a broad umbrella of research methodologies that encompasses grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss 2017 ; Strauss and Corbin 1990 ), case study (Flyvbjerg 2006 ; Yin 2003 ), phenomenology (Sanders 1982 ), discourse analysis (Fairclough 2003 ; Wodak and Meyer 2009 ), ethnography (Geertz 1973 ; Garfinkel 1967 ), and netnography (Kozinets 2002 ), among others. Qualitative research is often synonymous with ‘case study research’ because ‘case study’ primarily uses (but not always) qualitative data.

The quality standards or evaluation criteria of qualitative research comprises: (1) credibility (that a researcher can provide confidence in his/her findings), (2) transferability (that results are more plausible when transported to a highly similar contexts), (3) dependability (that errors have been minimized, proper documentation is provided), and (4) confirmability (that conclusions are internally consistent and supported by data) (see Lincoln and Guba 1985 ).

We classify research into a continuum of theory building — > theory elaboration — > theory testing . Theory building is also known as theory exploration. Theory elaboration refers to the use of qualitative data and a method to seek “confirmation” of the relationships among variables or processes or mechanisms of a social reality (Bartunek and Rynes 2015 ).

In the context of qualitative research, theory/ies usually refer(s) to conceptual model(s) or framework(s) that explain the relationships among a set of variables or processes that explain a social phenomenon. Theory or theories could also refer to general ideas or frameworks (e.g., institutional theory, emancipation theory, or identity theory) that are reviewed as background knowledge prior to the commencement of a qualitative research project.

For example, a qualitative research can ask the following question: “How can institutional change succeed in social contexts that are dominated by organized crime?” (Vaccaro and Palazzo 2015 ).

We have witnessed numerous cases in which committed positivist methodologists were asked to review qualitative papers, and they used a survey approach to assess the quality of an interpretivist work. This reviewers’ fallacy is dangerous and hampers the progress of a field of research. Editors must be cognizant of such fallacy and avoid it.

A social enterprises (SE) is an organization that combines social welfare and commercial logics (Doherty et al. 2014 ), or that uses business principles to address social problems (Mair and Marti 2006 ); thus, qualitative research that reports that ‘social impact’ is important for SEs is too descriptive and, arguably, tautological. It is not uncommon to see authors submitting purely descriptive papers to scholarly journals.

Some qualitative researchers have conducted qualitative work using primarily a checklist (ticking the boxes) to show the presence or absence of variables, as if it were a survey-based study. This is utterly inappropriate for a qualitative work. A qualitative work needs to show the richness and depth of qualitative findings. Nevertheless, it is acceptable to use such checklists as supplementary data if a study involves too many informants or variables of interest, or the data is too complex due to its longitudinal nature (e.g., a study that involves 15 cases observed and involving 59 interviews with 33 informants within a 7-year fieldwork used an excel sheet to tabulate the number of events that occurred as supplementary data to the main analysis; see Chandra 2017a , b ).

As mentioned earlier, there are different types of qualitative research. Thus, a qualitative researcher will customize the data collection process to fit the type of research being conducted. For example, for researchers using ethnography, the primary data will be in the form of photos and/or videos and interviews; for those using netnography, the primary data will be internet-based textual data. Interview data is perhaps the most common type of data used across all types of qualitative research designs and is often synonymous with qualitative research.

The purpose of qualitative research is to provide an explanation , not merely a description and certainly not a prediction (which is the realm of quantitative research). However, description is needed to illustrate qualitative data collected, and usually researchers describe their qualitative data by inserting a number of important “informant quotes” in the body of a qualitative research report.

We advise qualitative researchers to adhere to one approach to avoid any epistemological and ontological mismatch that may arise among different camps in qualitative research. For instance, mixing a positivist with a constructivist approach in qualitative research frequently leads to unnecessary criticism and even rejection from journal editors and reviewers; it shows a lack of methodological competence or awareness of one’s epistemological position.

Analytical generalization is not generalization to some defined population that has been sampled, but to a “theory” of the phenomenon being studied, a theory that may have much wider applicability than the particular case studied (Yin 2003 ).

There are different types of contributions. Typically, a researcher is expected to clearly articulate the theoretical contributions for a qualitative work submitted to a scholarly journal. Other types of contributions are practical (or managerial ), common for business/management journals, and policy , common for policy related journals.

There is ongoing debate on whether a template for qualitative research is desirable or necessary, with one camp of scholars (the pluralistic critical realists) that advocates a pluralistic approaches to qualitative research (“qualitative research should not follow a particular template or be prescriptive in its process”) and the other camps are advocating for some form of consensus via the use of particular approaches (e.g., the Eisenhardt or Gioia Approach, etc.). However, as shown in Table 1.1 , even the pluralistic critical realism in itself is a template and advocates an alternative form of consensus through the use of diverse and pluralistic approaches in doing qualitative research.

Alvesson, M., & Kärreman, D. (2007). Constructing mystery: Empirical matters in theory development. Academy of Management Review, 32 (4), 1265–1281.

Article Google Scholar

Bartunek, J. M., & Rynes, S. L. (2015). Qualitative research: It just keeps getting more interesting! In Handbook of qualitative organizational research (pp. 41–55). New York: Routledge.

Google Scholar

Brinkmann, S. (2018). Philosophies of qualitative research . New York: Oxford University Press.

Bucher, S., & Langley, A. (2016). The interplay of reflective and experimental spaces in interrupting and reorienting routine dynamics. Organization Science, 27 (3), 594–613.

Chandra, Y. (2017a). A time-based process model of international entrepreneurial opportunity evaluation. Journal of International Business Studies, 48 (4), 423–451.

Chandra, Y. (2017b). Social entrepreneurship as emancipatory work. Journal of Business Venturing, 32 (6), 657–673.

Corley, K. G., & Gioia, D. A. (2004). Identity ambiguity and change in the wake of a corporate spin-off. Administrative Science Quarterly, 49 (2), 173–208.

Cornelissen, J. P. (2017). Preserving theoretical divergence in management research: Why the explanatory potential of qualitative research should be harnessed rather than suppressed. Journal of Management Studies, 54 (3), 368–383.

Denis, J. L., Lamothe, L., & Langley, A. (2001). The dynamics of collective leadership and strategic change in pluralistic organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 44 (4), 809–837.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2011). Introduction. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Doherty, B., Haugh, H., & Lyon, F. (2014). Social enterprises as hybrid organizations: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 16 (4), 417–436.

Dubé, L., & Paré, G. (2003). Rigor in information systems positivist case research: Current practices, trends, and recommendations. MIS Quarterly, 27 (4), 597–636.

Easton, G. (2010). Critical realism in case study research. Industrial Marketing Management, 39 (1), 118–128.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989a). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14 (4), 532–550.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989b). Making fast strategic decisions in high-velocity environments. Academy of Management Journal, 32 (3), 543–576.

Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing discourse: Textual analysis for social research . Abingdon: Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12 (2), 219–245.

Friese, S. (2011). Using ATLAS.ti for analyzing the financial crisis data [67 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12 (1), Art. 39. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1101397

Garfinkel, H. (1967). Studies in ethnomethodology . Malden: Blackwell Publishers.

Geertz, C. (1973). Interpretation of cultures . New York: Basic Books.

Gehman, J., Glaser, V. L., Eisenhardt, K. M., Gioia, D., Langley, A., & Corley, K. G. (2017). Finding theory–method fit: A comparison of three qualitative approaches to theory building. Journal of Management Inquiry, 27 , 284–300. in press.

Gioia, D. A. (1992). Pinto fires and personal ethics: A script analysis of missed opportunities. Journal of Business Ethics, 11 (5–6), 379–389.

Gioia, D. A. (2007). Individual epistemology – Interpretive wisdom. In E. H. Kessler & J. R. Bailey (Eds.), The handbook of organizational and managerial wisdom (pp. 277–294). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Chapter Google Scholar

Gioia, D. (2019). If I had a magic wand: Reflections on developing a systematic approach to qualitative research. In B. Boyd, R. Crook, J. Le, & A. Smith (Eds.), Research methodology in strategy and management . https://books.emeraldinsight.com/page/detail/Standing-on-the-Shoulders-of-Giants/?k=9781787563360

Gioia, D. A., & Chittipeddi, K. (1991). Sensemaking and sensegiving in strategic change initiation. Strategic Management Journal, 12 (6), 433–448.

Gioia, D. A., Price, K. N., Hamilton, A. L., & Thomas, J. B. (2010). Forging an identity: An insider-outsider study of processes involved in the formation of organizational identity. Administrative Science Quarterly, 55 (1), 1–46.

Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16 (1), 15–31.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (2017). Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research . New York: Routledge.

Graebner, M. E., & Eisenhardt, K. M. (2004). The seller’s side of the story: Acquisition as courtship and governance as syndicate in entrepreneurial firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 49 (3), 366–403.

Grayson, K., & Shulman, D. (2000). Indexicality and the verification function of irreplaceable possessions: A semiotic analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 27 (1), 17–30.

Hunt, S. D. (1991). Positivism and paradigm dominance in consumer research: Toward critical pluralism and rapprochement. Journal of Consumer Research, 18 (1), 32–44.

King, G., Keohane, R. O., & Verba, S. (1994). Designing social inquiry: Scientific inference in qualitative research . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kozinets, R. V. (2002). The field behind the screen: Using netnography for marketing research in online communities. Journal of Marketing Research, 39 (1), 61–72.

Langley, A. (1988). The roles of formal strategic planning. Long Range Planning, 21 (3), 40–50.

Langley, A., & Abdallah, C. (2011). Templates and turns in qualitative studies of strategy and management. In Building methodological bridges (pp. 201–235). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Langley, A., Golden-Biddle, K., Reay, T., Denis, J. L., Hébert, Y., Lamothe, L., & Gervais, J. (2012). Identity struggles in merging organizations: Renegotiating the sameness–difference dialectic. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 48 (2), 135–167.

Langley, A. N. N., Smallman, C., Tsoukas, H., & Van de Ven, A. H. (2013). Process studies of change in organization and management: Unveiling temporality, activity, and flow. Academy of Management Journal, 56 (1), 1–13.

Lin, A. C. (1998). Bridging positivist and interpretivist approaches to qualitative methods. Policy Studies Journal, 26 (1), 162–180.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry . Beverly Hills: Sage.

Mair, J., & Marti, I. (2006). Social entrepreneurship research: A source of explanation, prediction, and delight. Journal of World Business, 41 (1), 36–44.

Nag, R., Corley, K. G., & Gioia, D. A. (2007). The intersection of organizational identity, knowledge, and practice: Attempting strategic change via knowledge grafting. Academy of Management Journal, 50 (4), 821–847.

Ozcan, P., & Eisenhardt, K. M. (2009). Origin of alliance portfolios: Entrepreneurs, network strategies, and firm performance. Academy of Management Journal, 52 (2), 246–279.

Prasad, P. (2018). Crafting qualitative research: Beyond positivist traditions . New York: Taylor & Francis.

Pratt, M. G. (2009). From the editors: For the lack of a boilerplate: Tips on writing up (and reviewing) qualitative research. Academy of Management Journal, 52 (5), 856–862.

Ramoglou, S., & Tsang, E. W. (2016). A realist perspective of entrepreneurship: Opportunities as propensities. Academy of Management Review, 41 (3), 410–434.

Sanders, P. (1982). Phenomenology: A new way of viewing organizational research. Academy of Management Review, 7 (3), 353–360.

Sobh, R., & Perry, C. (2006). Research design and data analysis in realism research. European Journal of Marketing, 40 (11/12), 1194–1209.

Stake, R. E. (2010). Qualitative research: Studying how things work . New York: Guilford Press.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. M. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques . Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Vaccaro, A., & Palazzo, G. (2015). Values against violence: Institutional change in societies dominated by organized crime. Academy of Management Journal, 58 (4), 1075–1101.

Weick, K. E. (1989). Theory construction as disciplined imagination. Academy of Management Review, 14 (4), 516–531.

Welch, C. L., Welch, D. E., & Hewerdine, L. (2008). Gender and export behaviour: Evidence from women-owned enterprises. Journal of Business Ethics, 83 (1), 113–126.

Welch, C., Piekkari, R., Plakoyiannaki, E., & Paavilainen-Mäntymäki, E. (2011). Theorising from case studies: Towards a pluralist future for international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 42 (5), 740–762.

Wodak, R., & Meyer, M. (Eds.). (2009). Methods for critical discourse analysis . London: Sage.

Yin, R. K. (1981). Life histories of innovations: How new practices become routinized. Public Administration Review, 41 , 21–28.

Yin, R. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods . Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Young, R. A., & Collin, A. (2004). Introduction: Constructivism and social constructionism in the career field. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64 (3), 373–388.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, Kowloon, Hong Kong

Yanto Chandra

City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, Kowloon, Hong Kong

Liang Shang

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Chandra, Y., Shang, L. (2019). Qualitative Research: An Overview. In: Qualitative Research Using R: A Systematic Approach. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-3170-1_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-3170-1_1

Published : 24 April 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-13-3169-5

Online ISBN : 978-981-13-3170-1

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Qualitative Research Bridging the Conceptual, Theoretical, and Methodological

- Sharon M. Ravitch - University of Pennsylvania, USA

- Nicole Mittenfelner Carl - University of Pennsylvania, USA

- Description

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

Supplements

Offering useful context to the cohort, who are mainly engaged in degree work for vocational purposes but who need to understand the context of the academic work they do

This book gives the student great general knowledge of qualitative reserch and it's different possibilities. THe book has been written understandable, thank you for writers!

Very useful to our Masters students

Will be very helpful for my students undertaking their research projects

This book will provide the content for my online qualitative methodology course. It is an excellent source. Dr. Ballenger

KEY FEATURES:

- Updated organization addresses ethics earlier in the research process

- A more cohesive discussion of research design helps students see the design process within one main chapter

- Additional resources and examples for developing questionnaires provide more thorough coverage

- Expanded discussions of qualitative coding and analysis over several chapters provide more student support for this crucial aspect of research

- Recommended Practices for each memo or document guide students in their creation and development

- Annotated Examples throughout provide real examples and author insights

- Appendices with new and updated examples from real student research including memos, protocols, forms, displays, and conference, grant, and dissertation proposals

Sample Materials & Chapters

Chapter 1: Qualitative Research An Opening Orientation

Chapter 2: Conceptual Frameworks in Research

For instructors

Select a purchasing option.

A Professional and Practitioner's Guide to Public Relations Research, Measurement, and Evaluation, Third Edition by David Michaelson, Don W. Stacks

Get full access to A Professional and Practitioner's Guide to Public Relations Research, Measurement, and Evaluation, Third Edition and 60K+ other titles, with a free 10-day trial of O'Reilly.

There are also live events, courses curated by job role, and more.

Qualitative Research Methodologies

Research can take place in a wide variety of forms, and each of these forms offers unique benefits that can be used to shape and evaluate public relations programs. One of the most basic forms of research is called qualitative research . For purposes of describing qualitative research, its applications, and its limitations, it is important to understand what qualitative research is.

The Dictionary of Public Relations Measurement and Research defines qualitative research as “research that seeks in-depth understanding of particular cases and issues, rather than generalizable statistical information, through probing, open-ended methods such as depth interviews, focus groups and ethnographic observation” ...

Get A Professional and Practitioner's Guide to Public Relations Research, Measurement, and Evaluation, Third Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.

Don’t leave empty-handed

Get Mark Richards’s Software Architecture Patterns ebook to better understand how to design components—and how they should interact.

It’s yours, free.

Check it out now on O’Reilly

Dive in for free with a 10-day trial of the O’Reilly learning platform—then explore all the other resources our members count on to build skills and solve problems every day.

6 Chapter 6: Qualitative Research in Criminal Justice

Case study: exploring the culture of “urban scrounging” 1.

Research Purpose

To describe the culture of urban scrounging, or dumpster diving, and the items that can be found in dumpsters and trash piles.

Methodology

This field study, conducted by Dr. Jeff Ferrell, currently a professor of sociology at Texas Christian University, began in 2002. In December of 2001, after resigning from an academic position in Arizona, Ferrell returned home to Fort Worth, Texas. An avid proponent for and participant in field research throughout his career, he decided to use the next eight months, prior to the 2002 academic year beginning, to explore a culture in which he had always been interested, the urban underground of “scrounging, recycling, and secondhand living” (p. 1). Using the neighborhoods of central Fort Worth as a backdrop, Ferrell embarked, often on his bicycle, into the fife of a dumpster diver. While he was not completely homeless at the time, he did his best to fully embrace the lifestyle of an urban scrounger and survive on what he found. For this study, Ferrell was not only learning how to survive off of the discarded possessions of others, he was systematically recording and describing the contents of the dumpsters and trash piles he found and kept. While in the field, Ferrell was also exploring scrounging as a means of economic survival and the social aspects of this underground existence. A broader theme of Ferrell’s research emerged as he encountered the number and vast array of items he found discarded in trash piles and dumpsters. This theme concerns the “hyperconsumption” and “collective wastefulness” (pp. 5–6) by American citizens and the environmental destruction created by the accumulating and discarding of so many material goods.

Results and Implications

Ferrell’s time spent among the trash piles and dumpsters of Fort Worth resulted in a variety of intriguing yet disturbing realizations regarding not only material excess but also social and personal change. While encounters with others were kept to a minimum, as they generally are for scroungers, Ferrell describes some of the people he met along the way and their conversations. Whether food, clothes, building materials, or scrap metal, the commonality was that scroungers could usually find what they were looking for among the trash heaps and alleyways. Throughout his book, Ferrell often focuses on the material items that he discovered while scrounging. He found so much, he was able to fill and decorate a home with perfectly good items that had been discarded by others, including the bicycle he now rides and a turquoise sink and bathtub. He found books and even old photographs and other mementos meant to document personal history. While discarded, these social artifacts tell the stories of society and often have the chance to find altered meaning when possessed by someone new.

Beyond the things found and people met, Ferrell discusses the boundary shift that has taken urban scrounging from deviant to criminal as lines are often blurred between public access and ownership. Not only do these urban scroungers face the stigma associated with their scrounging activities, those who dive in dumpsters and dig through trash piles can face criminal charges for trespassing. While this makes scrounging more challenging, due to basic survival or interest, the wealth of items and artifacts to be found are often worth the risk. Ultimately, Ferrell’s experiences as an urban scrounger provide not only a description of this subculture but also a critique on American consumption and wastefulness, a theme that becomes more important as Americans and others continue in economically tenuous times.

In This Chapter You Will Learn

To explain what it means for research to be qualitative

To describe the advantages of field research

To explain the challenges of field studies for researchers

To provide examples of field research in the social sciences

To discuss the case study approach

Introduction

In Chapter 2, you read about the differences between quantitative and qualitative methodologies. Whereas methods that are quantitative in nature focus on numerical measurements of phenomena, qualitative methods are focused on developing a deeper understanding regarding groups of people, or subcultures, about which little is known. Using detailed description, findings from qualitative research are generally more sensitizing, providing the research community and the interested public information about these generally elusive groups and their behaviors. A debate rages between criminologists as to which type of research should be achieved and referenced more often. The truth is that both have something valuable to offer regarding the study of deviance, crime, and victimization.

Field Research

Qualitative methodologies involve the use of field research, where researchers are out among these groups collecting information rather than studying participant behavior through surveys or experiments that have been developed in artificial settings. Field research provides some of the most fascinating reading because the researcher is observing closely or acting as part of the group and is therefore able to describe in depth not only the subjects’ behaviors, but also consider the motivations that drive their behaviors. This chapter focuses on the use of qualitative methods in the social sciences, particularly the use of participant observation to study deviant, and sometimes criminal, behaviors. The many challenges as well as advantages of conducting this type of research will be discussed as will well-known examples of past field research and suggestions for conducting this type of research. First, however, it is important to understand what sets qualitative field research apart from the other methodologies discussed in this text.

The Study of Behavior

It is common for criminal justice researchers to rely on survey or interview methodologies to collect data. One advantage of doing so is being able to collect data from many respondents in a short period of time. Technology has created other advantages with survey methodology. For example, Internet surveys are a convenient, quick, and inexpensive way to reach respondents who may or may not reside nearby. Researchers often survey community residents and university students, but may also focus specifically on offender or victim samples. One significant limitation of using survey methodologies is that they rely on the truthfulness of the respondents. If researchers are interested in attitudes and behaviors that may be illegal or otherwise controversial, it could be that respondents will not be truthful in answering the questions placed before them. Survey research has focused on past or current drug use (see the Monitoring the Future Program), past victimization experiences (see the National Criminal Victimization Survey), and prison sexual assault victimization (see the Prison Rape Elimination Act data collection procedures conducted by the Bureau of Justice Statistics), just to name a few. If a student uses marijuana but does not want anyone to know, they may choose to falsify their survey responses when asked about marijuana use. If a citizen or prison inmate has been sexually assaulted but is too ashamed or afraid to tell anyone, they may be untruthful when asked about such victimization experiences on a survey. The point is, although researchers attempt to better understand the attitudes and behaviors of a certain population through the use of surveys, there is one major drawback to consider: the disjunction between what people say and what they actually do. As mentioned previously, a student may be a drug user but not admit to it. Someone may be a gang member, but say they are not when asked directly about it. Someone may respond that they have never committed a crime or been victimized when in fact they have. In short, people sometimes lie and there are many potential reasons for doing so. Perhaps the offender or drug user has not yet been caught and does not want to be caught. Whatever the reason, this is a hazard of measuring attitudes and behaviors through the use of surveys. One way to overcome the issue of untruthfulness is to conduct research using various forms of actual participation or observation of the behaviors we want to study. By observing someone in their natural environment (or, “the field”), researchers have the ability to observe behaviors firsthand, rather than relying on survey responses. These research strategies are generally known as participant observation methods.

Types of Field Research: A Continuum

Participant observation strategies involve researchers studying groups or individuals in their natural setting. Think of participant observation as a student internship. Students may read about law enforcement in their textbooks and discuss law enforcement issues in class, but only through an internship with a law enforcement agency will a student have a chance to understand how things actually happen from firsthand observation. Field strategies were first developed for social science, and particularly crime, research in the 1920s by researchers working within the University of Chicago’s Department of Sociology. The “Chicago School,” as this group of researchers is commonly known, focused on ethnographic research to study urban crime problems. Emerging from the field of anthropology, ethnographic research relies on field research methodologies to scientifically examine human culture in the natural environment. Significant theoretical developments within the field of criminology, such as social disorganization, which focused on the impact of culture and environment, were advanced at this time. For example, researchers such as Shaw and McKay, Thrasher, and others used field research to study the activities of subcultures, particularly youth gangs, as well as areas of the city that were most impacted by crime. These researchers were not interested in studying these problems from afar. Instead, they were interested in understanding social problems, including the impact of environmental disintegration, from the field.

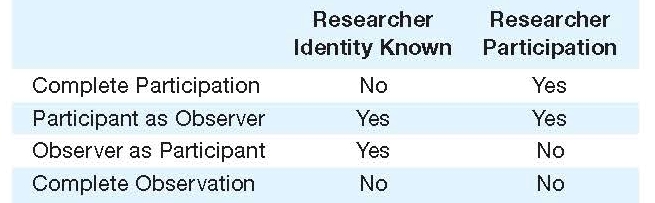

There are various ways to conduct field research, and these can be placed on a continuum from most to least invasive and also from more qualitative to more quantitative. In attempting to understand phenomena from the standpoint of the actors, a researcher may participate fully in the behaviors of the group or may instead choose to observe from afar as activities unfold. The most invasive, and also most qualitative, form of participant observation is complete participation. The least invasive, and also most quantitative, is complete observation. In between these two are participant as observer and observer as participant. Each of these strategies will now be discussed in more detail.

Complete participation, sometimes referred to as disguised observation, is a method that involves the researcher becoming a full-fledged member of a particular group. For example, if a researcher is interested in understanding the culture of correctional officers, she may apply to be hired on as a correctional officer. Once hired on, the researcher will wear the uniform and obtain firsthand experience working in a prison environment. To study urban gangs, a researcher may attempt to be accepted as a member or associate of the gang. In complete participation, the true identity of the researcher is not known to the members of the group. Therefore, they are ultimately just like any other member of the group under study. Not only will the researcher have the ability to observe the group from the inside, he can also manipulate the direction of group activity through participation or through the use of confederates. This method is considered the most qualitative because, as a complete participant, the researcher will be fully sensitized to what it is like to be a member of the group under study, and will fully participate in the group’s activities. The researcher can then share the information he has gathered on the group’s inner workings, motivations, and activities from the perspective of a group member.

Researchers utilizing the participant as observer method will also participate in the activities of the group under study. The difference between the complete participant strategy and participant as observer strategy is that in the participant as observer method, the researcher reveals herself as a researcher to the group. Her presence as a researcher is known. Accordingly, the researcher does not overtly attempt to influence the direction of group activity. While she does participate, the researcher is more interested in observing the group’s activity and corresponding behaviors as they occur naturally. So, if a researcher wanted to examine life as a homeless person, she might go to where a group of homeless persons congregate. The researcher would introduce herself as such but, if safe, stay one or many days and nights out with the homeless she meets in order to conduct observations and participate in group activities.

The third participant observation strategy is observer as participant. As with the participant as observer method, researchers using the observer as participant method reveal themselves to the group as a researcher. Here again, their presence as a researcher is known. What makes this strategy different from the first two is that the researcher does not participate in the group’s activities. While he may interact with the participants, he does not participate. Instead, the researcher is there only to observe. An example of this method would be a researcher who conducts “ride-alongs” in order to study law enforcement behavior during traffic stops. The researcher will interact with the officers, but he will not participate or even exit the car during the traffic stops being observed.

The least invasive participant observation strategy is complete observation. As you will learn in Chapter 7, this is a totally unobtrusive method; the research subjects are not aware that they are being observed for purposes of research. Think of a law enforcement officer being on a stakeout. These officers generally sit in unmarked vehicles down the street as they observe the movements and activities of a certain person or group of people. Researchers who are complete observers work much the same way. While being the least invasive, complete observation is also the least qualitative. Studying an individual or group from afar means that there is no interaction with that individual. Without this interaction, researchers are unable to gain a more sensitized understanding of the motivations of the group. This strategy is considered to be more quantitative because researchers must rely on counts of activities or movements. For example, if you are a researcher interested in studying how many drivers run a stop sign on campus, you may sit near the intersection and observe driver behavior. In collecting the data, you will count how many drivers make a complete stop, how many come to a rolling stop, and how many run the stop sign altogether. Now, although you may have these counts, you will not know why drivers stopped or not. It could be that one driver had a sick passenger who he was rushing to the hospital and that is why he did not come to a complete stop. As with most quantitative research, as a complete observer, questions of “why?” often go unanswered.

FIGURE 6.1 | Differences among Participant Observation Methods

Advantages and Disadvantages of Field Research by Method

As with any particular research method, there are advantages and disadvantages to conducting field research. Some of these are specific to the type of field research a researcher decides to conduct. One general advantage to participant observation methods is that researchers are able to study “hard to reach” populations. A disadvantage is that these groups may be difficult to study for a number of reasons. It could be that the group is criminal in nature, such as a youth gang, a biker gang, or the Mafia. While perhaps not criminal, the individual or group may be involved in deviant behaviors that they are unwilling to discuss even with people they know. An additional disadvantage is that there could be administrative roadblocks to conducting such research. If a researcher wants to understand the correctional officer culture but the prison will not allow the researcher to conduct the study, she may have to get hired on and conduct the research as a full participant. Examples of research involving each of these situations will be discussed later in this chapter.

Another challenge for field researchers is the ability to maintain objectivity. In Chapter 2, the importance of objectivity for scientific research was discussed. If data gathered is subjective or biased in some way, research findings will be impacted by this subjectivity and will therefore not be reflective of reality. While objectivity would be easier to maintain from afar, the closer a researcher becomes to a group and its members, the easier it may be to lose objectivity. This is true particularly for complete participants. For researchers who participate as members of the group under study, it may become difficult not to begin to identify with the group. When this occurs, and the researcher loses sight of the research goals in favor of group membership, it is called “ going native. ” This is a hazard of field research in which the researcher spends a significant amount of time, perhaps years, within a group. The researcher may begin to see things from the group’s perspective and therefore not be able to objectively complete the intended study. To balance this possible hazard of complete participation is the advantage of not having reactivity. Because the research subjects do not know they are being observed, they will not act any differently than they would under normal circumstances. Researchers therefore avoid the Hawthorne Effect when conducting field research as a complete participant.

There is the possibility that a researcher who incorporates the participant as observer strategy may also go native. Although his presence as a researcher is known, he is interacting with the group and participating in group activities. Therefore, it is possible he may begin to lose objectivity due to an attachment to or identification with the group under study. Whereas complete participants can avoid the Hawthorne Effect, participants as observers do not have this luxury. Even though these researchers may be participating in group activities, because their presence as a researcher is known, it can be expected that the group may in some way alter their behavior because they are being observed. An additional disadvantage to this strategy is that it may take time for a researcher to be accepted by group members who are aware of the researcher’s presence. If certain group members are uncomfortable with the researcher’s presence, they may make it difficult for the researcher to interact with other members or join in group activities.

Researchers on the observing end of the participant observation continuum face some similar and some unique challenges. Those who conduct observer as participant field studies will also face reactivity, or the Hawthorne Effect, because their presence as a researcher is known to the group under study. As in the ride-along example discussed previously, if a patrol officer knows she is being observed, she may alter her behavior in such a way that the researcher is not observing a realistic traffic stop. Additionally, these researchers may face difficulties gaining access or being accepted into the group under study, especially since they are there only to observe and not to participate with the group. In this case, the researcher may be ostracized even further by the group because she is not acting as one of them.

Researchers acting as complete observers to gather data on an individual or group are not limited by reactivity. Because the research subjects are unaware they are being observed, the Hawthorne Effect will not impact study findings. The advantage is that this method is totally unobtrusive, or noninvasive. The main disadvantage here is that the researcher is too far away to truly understand the group and their behaviors. As mentioned previously, at this point, the research becomes quite quantitative because the researcher can only observe and count movements and interactions from afar. Lacking in context, these counts may not be as useful in understanding a group as findings would be from the use of another participant observation method.

Costs One of the more important factors to consider when determining whether field research is the best option is the demand such research may place on a researcher. If you remember from the opening case study, Ferrell spent months in the field to collect information on urban scrounging. Researchers may spend weeks, months, and even years participating with and/or observing study subjects. Due to this, they may experience financial, personal, and sometimes professional costs. Time away from family and friends can take a personal toll on researchers. If the researcher is funding his own research or otherwise not able to earn a salary while undergoing the field study, he may suffer financially. Finally, also due to time away and perhaps due to activities that may be considered unethical, fieldwork can have a negative impact on a researcher’s career. While these demands are very real, past researchers have found ways to successfully navigate the world of field research resulting in fascinating findings and ultimately coming out unscathed from the experience.

Gaining Access Gaining access to populations of interest is also a difficult task to accomplish as these populations are often small, clandestine groups who generally keep out of the public eye. Field research is unlike survey research in that there is not a readily available list of gang members or dumpster divers from which you can draw a random sample. Instead, researchers often rely on the snowball sampling technique. If you remember from Chapter 3, snowball sampling entails a researcher meeting one or a handful of group members and receiving introductions to other group members from the initial members. One member leads you to the next, who then leads you to the next.

When gathering information as an observer as participant, a researcher should be straightforward and announce her intentions to group members immediately. It may be best to give a detailed explanation of her presence and purpose to group leaders or other decision-makers. If this does not happen, when the group does find out a researcher is in their presence, they may feel the researcher was trying to hide something. If the identity of the researcher is known, it is important that the researcher be a researcher, and that she not pretend to be one of the group, as this may also cause problems. It may be disconcerting to group members if an outsider thinks she is closer to the group than members are willing to allow her to be.

While complete participant researchers may be introduced to one or more members, this does not mean that they will be readily accepted as part of the group. This is true even if they are acting as full participants. There are some things researchers can do to increase their chances of being accepted. First, researchers should learn the argot, or language, of the group under study. Study subjects may have a particular way of speaking to one another through the use of slang or other vernacular. If a researcher is familiar with this argot and is able to use it convincingly, he will seem less of an outsider. It is also important to time your approach. A researcher should be aware, as much as possible, about what is happening in the group before gaining access. If a researcher is studying drug dealers and there was just a big drug bust or if a researcher is studying gangs and there was recently a fight between two gangs, it may not be the best time to gain access as members of these groups may be immediately suspicious of people they do not know.

Researchers often must find a gatekeeper in order to join a group. Gatekeepers are those individuals who may or may not know about the researcher’s true identity, who will vouch for the researcher among the other group members and who will inform the researcher about group norms, territory, and the like. Gatekeepers may lobby to have a researcher become a part of the group or to be allowed access to the place where the group gathers. While this is helpful for the researcher, it can be dangerous for the gatekeeper, especially if something goes wrong. If the researcher is attempting to be a full participant but her identity as a researcher is exposed, the gatekeeper may be held responsible for allowing the researcher in. This may be the case even if the gatekeeper was not aware of the researcher’s true identity. If a researcher does not want to enter the group himself, he may find an indigenous observer, or a member of the group who is willing to collect information for him. The researcher may pay or otherwise remunerate this person for her efforts as she will be able to see and hear what the researcher could not. A similar problem may arise, however, if this person is caught. There may be negative consequences to pay if it is found out that she is revealing information about the group. Additionally, the researcher must be careful when analyzing the information provided as it may not be objective, or may not even be factual at all.

Maintaining Objectivity Once a researcher gains access, there is another issue she must face. This is the difficulty of remaining an outsider while becoming an insider. In short, the researcher must guard against going native. Objectivity is necessary for research to be scientific. If a researcher becomes too familiar with the group, she may lose objectivity and may even be able to identify with and/or empathize with the group under study. If this occurs, the research findings will be biased and not an objective reflection of the group, what drives the group, and the activities in which the group members participate. For these reasons, it is not suggested that a researcher conduct field research among a group of which he is a member. If a researcher has been a member of a social organization for many years and is friends, or at least acquaintances, with many of the members, it would be very difficult for her to objectively study the group. The researcher may consider the group and the group’s activities as normal and therefore miss out on interesting relationships and behaviors. This is also why external researchers are often brought in to evaluate agency programs. If employees of that program are tasked with evaluating it, they may—consciously or not—design the study in such a way that findings are sure to be positive. This may be because they feel that a negative evaluation will mean an end to the program and ultimately an end to their jobs. Having such a stake in the findings of research is sure to impact the objectivity of the person tasked with conducting the study. While bringing in external researchers may ensure objectivity, these researchers face their own challenges. Trulson, Marquart, and Mullings 3 offer some tips for breaking in to criminal justice agencies, specifically prisons, as an external researcher. The first two tips pertain to obtaining access through the use of a gatekeeper. The third tip focuses on the development and cultivation of relationships within the agency in order to maintain access. The remaining tips describe how a researcher can make a graceful exit once the research project is completed while still maintaining those relationships, as well as building new ones, for potential future research endeavors.

❑ Tip #1: Get a Contact

❑ Tip #2: Establish Yourself and Your Research

❑ Tip #3: Little Things Count

❑ Tip #4: Make Sense of Agency Data by Keeping Contact

❑ Tip #5: Deliver Competent Readable Reports on Time

❑ Tip #6: Request to Debrief the Agency

❑ Tip#7: Thank Everyone

❑ Tip #8: Deal with Adversity by Planning Ahead

❑ Tip #9: Inform the Agency of Data Use

❑ Tip #10: Maintain Trust by Staying in for the Long Haul (pp. 477–478)

CLASSICS IN CJ RESEARCH

Youth Violence and the Code of the Street

Research Study

Based on his ethnography of African American youth living in poor, inner-city neighborhoods, Elijah Anderson 2 developed a comprehensive theory regarding youth violence and the “code of the street.” Anderson explains that, stemming from a lack of resources, distrust in law enforcement, and an overall lack of hope, aggressive behavior is condoned by the informal street code as a way to resolve conflict and earn respect. Anderson’s detailed description and analysis of this street culture provided much needed awareness regarding the context of African American youth violence. Like other research discussed in this chapter, these populations could not be sent an Internet survey or be surveyed in a classroom. The only way for Anderson to gain this knowledge was to go out to the streets and observe and interact with the youth himself. To do this, he conducted four years of field research in both the inner city and the more suburban areas of Philadelphia. During this time, he conducted lengthy interviews with youth and acted as a direct observer of their activities. Anderson’s research is touted for bringing attention to and understanding of inner-city life. Not only does he describe the “code of the street,” but, in doing so, he provides answers to the problem of urban youth violence.

Documenting the Experience Researchers must also decide how best to document their experiences for later analysis. There is a Chinese Proverb that states, “the palest ink is better than the best memory.” Applied here, researchers are encouraged to document as much as they can, as giving a detailed account of things that have occurred from memory is difficult. When taking notes, it is important for researchers to be as specific as possible when describing individuals and their behaviors. It is also important for researchers not to ignore behaviors that may seem trivial at the time, as these may actually signify something much more meaningful.

Particularly as a complete participant, researchers are not going to have the ability to readily pull out their note pad and begin taking notes on things they have seen and heard. Even careful note taking can be dangerous for a researcher who is trying to hide his identity. If a researcher is found to be documenting what is happening within the group, this may breed distrust and group members may become suspicious of the researcher. This suspicion may cause the group members to act unnaturally around the researcher. Even if research subjects are aware of the researcher’s identity, having someone taking notes while they are having a casual conversation can be disconcerting. This may make subjects nervous and unwilling to participate in group activities while the researcher is present. Luckily, with the advance of technology, documentation does not have to include a pen and a piece of paper. Instead, researchers may opt for audio and/or visual recording devices. In one-party consent states, it is legal for one person to record a conversation they are having with another. Not all states are one-party consent states, however, so researchers must be careful not to break any laws with their plan for documentation.

WHAT RESEARCH SHOWS: IMPACTING CRIMINAL JUSTICE OPERATIONS

Application of Field Research Methods in Undercover Investigations

Participant observation research not only informs criminal justice operations, but police and other investigative agencies use these methods as well. Think about an undercover investigation. While the purpose of going undercover for a law enforcement officer is to collect evidence against a suspect, the officer’s methods mirror those of an academic researcher who joins a group as a full participant. In the 1970s, FBI agent Joe Pistone 4 went undercover to obtain information about the Bonnano family, one of the major Sicilian organized crime families in New York at the time. Assuming the identity of Donnie Brasco, the jewel thief, Pistone infiltrated the Bonnano family for six years. Using many of the techniques discussed here—learning the argot and social mores of the group, finding a gatekeeper, documenting evidence through the use of recording devices—by the early 1980s, Pistone provided the FBI with enough evidence to put over 100 Mafioso in prison for the remainder of their lives. Many of you may recognize his alias, as Pistone’s experiences as an undercover agent were brought to the big screen with the release of Donnie Brasco, starring Johnny Depp. Depp’s portrayal of Pistone showed not only his undercover persona but also the difficulties he had maintaining relationships with his loved ones. Now, more than 30 years later, people are still interested in Pistone’s experiences as Brasco. As recently as 2005, the National Geographic Channel premiered Inside the Mafia, a series focused on Pistone’s experiences as Brasco. While this is a more well-known example of an undercover operation, undercover work goes on all the time. Whether making drug busts, infiltrating gangs or other trafficking organizations, or conducting a sting operation on one of their own, investigators employ many of the same techniques as field researchers rely upon.

Ethical Dilemmas for Field Researchers

As you can tell, field research poses unique complications for researchers to consider prior to and while conducting their studies. Ethical issues posed by field research, particularly field research in which the researcher’s identity is not known to research subjects, include the use of deception, privacy invasion, and the lack of consent. How can a researcher obtain informed consent from research subjects if she doesn’t want anyone to know research is taking place? Is it ethical to include someone in a research study without his or her permission? When the first guidelines for human subjects research were handed down, they caused a huge roadblock for field researchers. Later, however, it was determined that social science poses less risk to human subjects, particularly those being observed in their natural setting. Because it was recognized that the risk for harm was significantly less, field researchers were allowed to conduct their studies without conditions involving informed consent. The debate remains, however, as to whether it is truly ethical to conduct research on individuals without them knowing. A related issue is confidentiality and anonymity. If researchers are living among study subjects, anonymity is impossible. One way field researchers protect their subjects in this regard is through the use of pseudonyms. A pseudonym is a false name given to someone whose identity needs to be kept secret. In writing up their study findings, researchers will use pseudonyms instead of the actual names of study subjects.

Beyond the ethical nature of the research itself, field studies may introduce other ethical dilemmas for the researcher. For example, what if the researcher, as a participating member of a group, is asked to participate in an illegal activity? This may be a nonviolent activity like vandalism or graffiti, or it may be an activity that is more sinister in nature. Researchers, as full participants, have to decide whether they would be willing to commit the crime in question. After all, if caught and arrests are made, “I was just doing research,” will not be a justification the researcher will be able to use for his participation. Even if not a full participant, a researcher may observe some activity that is unlawful. The researcher will then have to decide whether to report this activity or to keep quiet about it. If a researcher is called to testify, there could be consequences for not cooperating. Depending on what kind of group is being studied, these dilemmas may occur more or less frequently. It is important that researchers understand prior to entering the field that they may have to make difficult decisions that like the research itself, could have great costs to them personally and professionally.

RESEARCH IN THE NEWS

Field Research Hits Prime Time

In 2009, CBS aired a new reality television series, Undercover Boss, 5 in which corporate executives go “undercover” to experience life as an employee of their company. Fully disguised, the executives are quickly thrown into the day-to-day operations of their workplaces. From the co-owner of the Chicago Cubs, to the CEO of Norwegian Cruise Line, to the mayor of Cincinnati, these executives conduct field research on camera to gain a better understanding of how their company, or city administration, runs from the bottom up. Often, they find hard-working, talented employees who are deserving of recognition, which is given as the episode comes to a close and the executive reveals himself and his undercover activities to his employees. Other times, they find employees that are not so good for business. Ultimately, the experience provides these executives with awareness they did not have prior to going undercover, and they hope to be able to utilize this knowledge to position their workplaces for continued success. Not only has this show benefited the companies and other workplaces profiled, with millions of viewers each week, it has certainly brought the adventures of field research into prime time.

Examples of Field Research in Criminal Justice

If you recall from Chapter 2, Humphreys’ Tea Room Trade is an example of field research. Humphreys participated to an extent, acting as a “watchqueen” so that he could observe the sexual activities taking place in public restrooms and other public places. Another study exploring clandestine sexual activity was conducted by Styles. 6 Styles was interested in the use of gay baths, places where men seeking to have sexual relationships with other men could have relatively private encounters. While Styles was a gay man attempting to study other gay men, at the outset his intention was to be a nonparticipant observer. Having a friend vouch for him, he easily gained access into the bath and began figuring out how to best observe the scene. After observing and conducting a few interviews, Styles was approached by another man for sexual activity. Although he was resolved to only observe, this time he gave in. From this point on, he began attending another bath and collecting information as a complete participant. Styles’ writing is informative, not only for the description regarding this group’s activity, but also for the discussion he provides about his travels through the world of field research, beginning as an observer and ending as a complete participant. His writing on insider versus outsider research resulted in four main reflections for readers to consider:

There are no privileged positions of knowledge when it comes to scrutinizing human group life;

All research is conditioned by value biases and factual preconceptions about the group being studied;

Fieldwork is a process of building up images from one’s biases, preconceptions, and new information, testing these images against one’s observations and the reports of informants, and accepting, modifying, or discarding these images on the basis of what one observes and what one has been told; and

Insider and outsider researchers will differ in the ways they go about building and testing their images of the group they study. (pp. 148–150)

Reviewing the literature, one finds that field researchers often choose sexual deviance as a topic for their field studies. Tewksbury and colleagues have researched gender differences in sex shop patrons 7 and places where men have been found to have anonymous sexual encounters 8 such as sex shop theaters. 9 Another interesting field study was conducted by Ronai and Ellis. 10 For this study, Ronai acted as a complete participant, drawing from her past as a table dancer and also gaining access as an exotic dancer in a Florida strip bar for the purpose of her master’s thesis research. Building on Ronai’s experiences and her interviews with fellow dancers, the researchers examined the interactional strategies used by dancers, both on the stage and on the floor, to ensure a night where the dancers were well paid for their services. In conducting these studies, these researchers were able to expose places where many are either unwilling or afraid to go, or perhaps afraid to admit they go.

In their study of women who belong to outlaw motorcycle gangs, Hopper and Moore 11 used participant observation methods as well as interviews to better understand the biker culture and where women fit into this culture. Moore provided access, as he was once a member and president of Satan’s Dead, an outlaw biker club in Mississippi. Like Styles, Hopper and Moore discuss the challenges of conducting research among the outlaw biker population. Having to observe quietly while bikers committed acts opposite to their personal values and not being able to ask many questions or give uninvited comments were just some of the hurdles the researchers had to overcome in order to conduct their study. The male bikers were, at the least, distrustful of the researchers, and the women bikers even more so. While these challenges existed, Hopper and Moore were able to ascertain quite a bit about the female experience as relates to their role in or among the outlaw biker culture.

Ferrell has been one of the most active field researchers of our time. He is considered a founder and remains a steadfast proponent of cultural criminology, 12 a subfield of criminology that examines the intersections of cultural activities and crime. Not only did he conduct the ethnography on urban scrounging discussed at the beginning of this chapter, he has spent more than a decade in the field studying subcultural groups who defy social norms. Crossing the United States, and the globe, Ferrell has explored the social and political motivations of urban graffiti artists, 13 anarchist bicycle group activists, and outlaw radio operators, 14 just to name a few. The research conducted by Ferrell, and others discussed here, has been described as edgework, or radical ethnography. This means that, as researchers, Ferrell and others have gone to the “edge,” or the extreme, to collect information on subjects of interest. Ferrell and Hamm 15 have put together a collection of readings based on edgework, as have Miller and Tewksbury. 16 While dangerous and wrought with ethical challenges, their research has shed light on societal groups who, whether by choice or not, often reside in the shadows.

Although ethnographers have spent years studying criminal and other deviant activities, field research has not been limited to those groups. Other researchers have sought to explore what it’s like to work in criminal justice from the inside. In the 1960s, Skolnick 17 conducted field research among police officers to better understand how elements of their occupation impacted their views and behaviors. He wrote extensively about the “working personality” of police officers as shaped by their occupational environment, including the danger and alienation they face from those they are sworn to protect, and the solidarity that builds from shared experiences. Beyond law enforcement, there have also been a variety of studies focused on the prison environment. When Ted Conover, 18 a journalist interested in writing from the correctional officer perspective, was denied permission from the New York Department of Correctional Services to do a report on correctional life, he instead applied and was hired on as an actual correctional officer. In Newjack: Guarding Sing Sing, Conover offers a compelling account of his journalistic field research, which resulted in a one-year stint as a corrections officer. From his time in training until his last days working in the galleries, Conover’s experiences provide the reader a look into the challenges faced by correctional officers, stemming not only from the inmates but the correctional staff as well.

Prior to Conover’s writing, Marquart was also interested in correctional work and strategies utilized by prison guards to ensure control over the inmate population. Specifically, in the 1980s, Marquart 19 examined correctional officials’ use of physical coercion and Marquart and Crouch 20 explored their use of inmate leaders as social control mechanisms. In order to conduct this field study, Marquart, with the warden’s permission, entered a prison unit in Texas and proceeded to work as a guard from June 1981 until January 1983. He was able to work in various posts within the institution so that he could observe how prison guards interacted with inmates. Marquart not only observed the prison’s daily routine, he examined institutional records, conducted interviews, and also developed close relationships with 20 prison guards and inmate leaders, or building tenders, whom he relied on for their insider knowledge of prison life and inmate control. Based on his fieldwork, Marquait shared his findings regarding the intimidation and physical coercion used by prison guards to discipline inmates. This fieldwork also provided a fascinating look into the building tender system that was utilized as a means of social control in the Texas prison system prior to that system being discontinued.

In the early 1990s, Schmid and Jones 21 used a unique strategy to study inmate adaptation from inside the prison walls. Jones, an offender serving a sentence in a prison located in the upper midwestern region of the United States, was given permission to enroll in a graduate sociology course focused on methods of research. This course was being offered by Schmid and led to collaborative work between the two men to study prison culture. They specifically focused on the experiences of first-time, short-term inmates. With Jones acting as the complete participant and Schmid acting as the complete observer, the pair began their research covertly. While they were aware of Jones’s meeting with Schmid for purposes of the research methods course in which he was enrolled, correctional authorities and other inmates perceived Jones to be just another inmate. In the 10 months that followed, Jones kept detailed notes regarding his daily experiences and his personal thoughts about and observations of prison life. Also included in his notes was information about his participation in prison activities and his communications with other similar, first-time, short-term inmates. Once his field notes were prepared, Jones would mail them to Schmid for review. Over the course of these letters, phone calls, and intermittent meetings, new observation strategies and themes began to develop based on the observations made by Jones. Upon his release from prison and their analyzing of the initial data, Jones and Schmid reentered the prison to conduct informed interviews with 20 first-time, short-term inmates. Using these data, Schmid and Jones began to write up their findings, which focused on inmate adaptations over time, identity transformations within the prison environment, 22 and conceptions of prison sexual assault, 23 among other topics. Schmid and Jones discussed how their roles as a complete observer and a complete participant allowed them the advantage of balancing scientific objectivity and intimacy with the group under study. The unfettered access Jones had to other inmates within the prison environment as a complete participant added to the unusual nature of this study yielding valuable insight into the prison experience for this particular subset of inmates.

Case Studies

Beyond field research, case studies provide an additional means of qualitative data. While more often conducted by researchers in other disciplines, such as psychology, or by journalists, criminologists also have a rich history of case study research. In conducting case studies, researchers use in-depth interviews and oral/life history, or autobiographical, approaches to thoroughly examine one or a few illustrative cases. This method often allows individuals, particularly offenders, to tell their own story, and information from these stories, or case studies, may then be extrapolated to the larger group. The advantage is a firsthand, descriptive account of a way of life that is little understood. Disadvantages relate to the ability to generalize from what may be an atypical case and also the bias that may enter as a researcher develops a working relationship with their subject. Most examples of case studies involving criminological subjects were conducted more than 20 years ago, which may be due to criminologists’ general inclination toward more quantitative research during this time period.

The earliest case studies focused on crime topics were conducted in the 1930s. Not only was the Chicago School interested in ethnographic research, these researchers were also among the first to conduct case studies on individuals involved in criminal activities. Shaw’s The Jack Roller (1930) 24 and Sutherland’s The Professional Thief (1937) 25 are not only the oldest but also the most well-known case studies related to delinquent and criminal figures. Focused on environmental influences on behavior, Shaw profiled an inner city delinquent male, “Stanley” the “jack roller,” who explained why he was involved in delinquent behavior, specifically the crime of mugging intoxicated men. Fifty years later, Snodgrass 26 updated Shaw’s work, following up with an elderly “Stanley” at age 70. Sutherland’s case study, resulting in the publication of The Professional Thief, was based on “Chic Conwell’s” account of his personal life and professional experience surviving off of what could be stolen or conned from others. The 1970s and 1980s witnessed numerous publications based on case studies. Researchers examined organized crime figures and families, 27 heroin addicts, 28 thieves, 29 and those who fence stolen property. 30 As with participant observation research, case studies have not been relegated to offenders only. In fact, more recently the case study approach has been applied to law enforcement and correctional agencies. 33 These studies have examined activities of the New York City Police Department, 34 the New Orleans Police Department’s response in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, 35 and Rhode Island’s prison system. 36