Questions? Visit the CDO Welcome Desk or email us at [email protected] . | CDO Welcome Desk Hours: M-F, 9am-4pm | The Virtual Interview Room is available for spring semester bookings!

- Bio / Pharma / Healthcare

- CPG / Retail

- Data Science & Analytics

- Entertainment, Media, & Sports

- Entrepreneurship

- Product Management

- Sustainability

- Diversity & Inclusion

- International Students

- Writing the Code – URM Programming

- MBA / LGO / MSMS

- Featured Jobs

- Career Central

- Parker Dewey: Micro-Internships

- Alumni Job Board

- CDO Employer Relations & Recruiting

- CDO Club Liaisons

- MIT Sloan Industry Advisors

- MIT Sloan Faculty

- MBA Career Peers

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- CDO Year In Review

- Employment Reports

- Employment Directories

- Employment Surveys

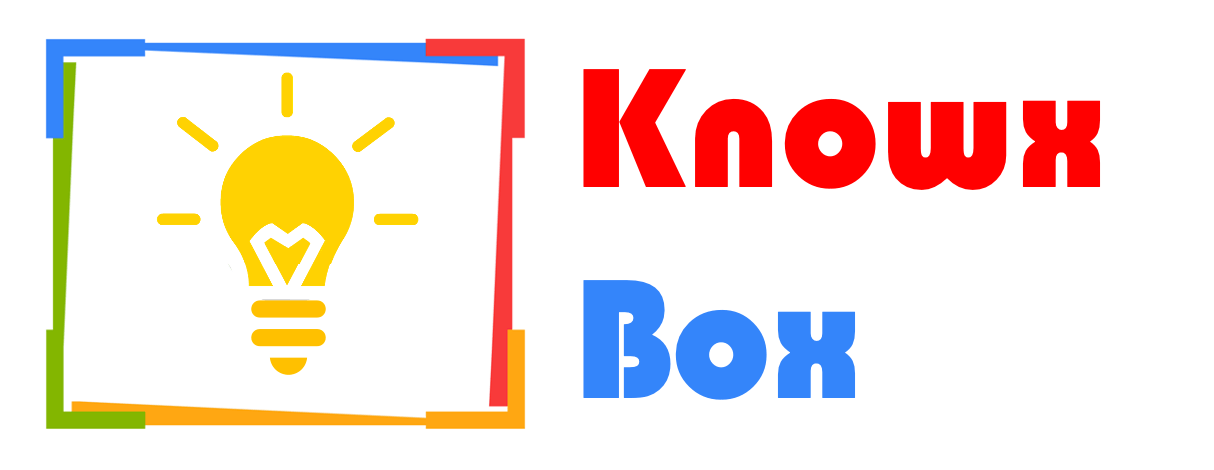

The Personality Traits That Define a Successful Problem-Solver

- Share This: Share The Personality Traits That Define a Successful Problem-Solver on Facebook Share The Personality Traits That Define a Successful Problem-Solver on LinkedIn Share The Personality Traits That Define a Successful Problem-Solver on X

Problems are an unavoidable fact of life. Do not be surprised as an entrepreneur if your days are consistently filled with a continuous wave of problems.

However, Entrepreneur Network partner Brian Tracy recommends you do your best to control your attitude. If you are able to control your emotional tendencies, you will be able to deal with problems more tactfully. Next, try to embrace a solution-oriented personality and focus on what can be done in the moment. Switch your mind from the problem (the negative) to the solution (the positive).

Click here to watch the video.

- Top Courses

- Online Degrees

- Find your New Career

- Join for Free

7 Problem-Solving Skills That Can Help You Be a More Successful Manager

Discover what problem-solving is, and why it's important for managers. Understand the steps of the process and learn about seven problem-solving skills.

![character traits for problem solving [Featured Image]: A manager wearing a black suit is talking to a team member, handling an issue utilizing the process of problem-solving](https://d3njjcbhbojbot.cloudfront.net/api/utilities/v1/imageproxy/https://images.ctfassets.net/wp1lcwdav1p1/6uiffmHlG1nCAhji06VPaV/06ef7be91702ee158c66d2caeae98607/iStock-1176251115__2_.jpg?w=1500&h=680&q=60&fit=fill&f=faces&fm=jpg&fl=progressive&auto=format%2Ccompress&dpr=1&w=1000)

1Managers oversee the day-to-day operations of a particular department, and sometimes a whole company, using their problem-solving skills regularly. Managers with good problem-solving skills can help ensure companies run smoothly and prosper.

If you're a current manager or are striving to become one, read this guide to discover what problem-solving skills are and why it's important for managers to have them. Learn the steps of the problem-solving process, and explore seven skills that can help make problem-solving easier and more effective.

What is problem-solving?

Problem-solving is both an ability and a process. As an ability, problem-solving can aid in resolving issues faced in different environments like home, school, abroad, and social situations, among others. As a process, problem-solving involves a series of steps for finding solutions to questions or concerns that arise throughout life.

The importance of problem-solving for managers

Managers deal with problems regularly, whether supervising a staff of two or 100. When people solve problems quickly and effectively, workplaces can benefit in a number of ways. These include:

Greater creativity

Higher productivity

Increased job fulfillment

Satisfied clients or customers

Better cooperation and cohesion

Improved environments for employees and customers

7 skills that make problem-solving easier

Companies depend on managers who can solve problems adeptly. Although problem-solving is a skill in its own right, a subset of seven skills can help make the process of problem-solving easier. These include analysis, communication, emotional intelligence, resilience, creativity, adaptability, and teamwork.

1. Analysis

As a manager , you'll solve each problem by assessing the situation first. Then, you’ll use analytical skills to distinguish between ineffective and effective solutions.

2. Communication

Effective communication plays a significant role in problem-solving, particularly when others are involved. Some skills that can help enhance communication at work include active listening, speaking with an even tone and volume, and supporting verbal information with written communication.

3. Emotional intelligence

Emotional intelligence is the ability to recognize and manage emotions in any situation. People with emotional intelligence usually solve problems calmly and systematically, which often yields better results.

4. Resilience

Emotional intelligence and resilience are closely related traits. Resiliency is the ability to cope with and bounce back quickly from difficult situations. Those who possess resilience are often capable of accurately interpreting people and situations, which can be incredibly advantageous when difficulties arise.

5. Creativity

When brainstorming solutions to problems, creativity can help you to think outside the box. Problem-solving strategies can be enhanced with the application of creative techniques. You can use creativity to:

Approach problems from different angles

Improve your problem-solving process

Spark creativity in your employees and peers

6. Adaptability

Adaptability is the capacity to adjust to change. When a particular solution to an issue doesn't work, an adaptable person can revisit the concern to think up another one without getting frustrated.

7. Teamwork

Finding a solution to a problem regularly involves working in a team. Good teamwork requires being comfortable working with others and collaborating with them, which can result in better problem-solving overall.

Steps of the problem-solving process

Effective problem-solving involves five essential steps. One way to remember them is through the IDEAL model created in 1984 by psychology professors John D. Bransford and Barry S. Stein [ 1 ]. The steps to solving problems in this model include: identifying that there is a problem, defining the goals you hope to achieve, exploring potential solutions, choosing a solution and acting on it, and looking at (or evaluating) the outcome.

1. Identify that there is a problem and root out its cause.

To solve a problem, you must first admit that one exists to then find its root cause. Finding the cause of the problem may involve asking questions like:

Can the problem be solved?

How big of a problem is it?

Why do I think the problem is occurring?

What are some things I know about the situation?

What are some things I don't know about the situation?

Are there any people who contributed to the problem?

Are there materials or processes that contributed to the problem?

Are there any patterns I can identify?

2. Define the goals you hope to achieve.

Every problem is different. The goals you hope to achieve when problem-solving depend on the scope of the problem. Some examples of goals you might set include:

Gather as much factual information as possible.

Brainstorm many different strategies to come up with the best one.

Be flexible when considering other viewpoints.

Articulate clearly and encourage questions, so everyone involved is on the same page.

Be open to other strategies if the chosen strategy doesn't work.

Stay positive throughout the process.

3. Explore potential solutions.

Once you've defined the goals you hope to achieve when problem-solving , it's time to start the process. This involves steps that often include fact-finding, brainstorming, prioritizing solutions, and assessing the cost of top solutions in terms of time, labor, and money.

4. Choose a solution and act on it.

Evaluate the pros and cons of each potential solution, and choose the one most likely to solve the problem within your given budget, abilities, and resources. Once you choose a solution, it's important to make a commitment and see it through. Draw up a plan of action for implementation, and share it with all involved parties clearly and effectively, both verbally and in writing. Make sure everyone understands their role for a successful conclusion.

5. Look at (or evaluate) the outcome.

Evaluation offers insights into your current situation and future problem-solving. When evaluating the outcome, ask yourself questions like:

Did the solution work?

Will this solution work for other problems?

Were there any changes you would have made?

Would another solution have worked better?

As a current or future manager looking to build your problem-solving skills, it is often helpful to take a professional course. Consider Improving Communication Skills offered by the University of Pennsylvania on Coursera. You'll learn how to boost your ability to persuade, ask questions, negotiate, apologize, and more.

You might also consider taking Emotional Intelligence: Cultivating Immensely Human Interactions , offered by the University of Michigan on Coursera. You'll explore the interpersonal and intrapersonal skills common to people with emotional intelligence, and you'll learn how emotional intelligence is connected to team success and leadership.

Build job-ready skills with a Coursera Plus subscription

- Get access to 7,000+ learning programs from world-class universities and companies, including Google, Yale, Salesforce, and more

- Try different courses and find your best fit at no additional cost

- Earn certificates for learning programs you complete

- A subscription price of $59/month, cancel anytime

Article sources

Tennessee Tech. “ The Ideal Problem Solver (2nd ed.) , https://www.tntech.edu/cat/pdf/useful_links/idealproblemsolver.pdf.” Accessed December 6, 2022.

Keep reading

Coursera staff.

Editorial Team

Coursera’s editorial team is comprised of highly experienced professional editors, writers, and fact...

This content has been made available for informational purposes only. Learners are advised to conduct additional research to ensure that courses and other credentials pursued meet their personal, professional, and financial goals.

10 Characteristics of Good Problem Solvers

Professional psychologist, motivational writer

Good problem solvers are good thinkers. They have less drama and problems to begin with and don't get overly emotional when faced with a problem. They usually see problems as challenges and life experiences and try to stand above them, objectively.

Good problem solvers use a combination of intuition and logic to come up with their solutions. Intuition has more to do with the emotional and instinctive side of us and logic is more related to our cognition and thinking. Good problem solvers use both of these forces to get as much information as they can to come up with the best possible solution. In addition, they are reasonably open minded but logically skeptical.

Some of the general characteristics of good problem solvers are:

1. They don't need to be right all the time: They focus on finding the right solution rather than wanting to prove they are right at all costs.

2. They go beyond their own conditioning: They go beyond a fixated mind set and open up to new ways of thinking and can explore options.

3. They look for opportunity within the problem: They see problems as challenges and try to learn from them.

4. They know the difference between complex and simple thinking: They know when to do a systematic and complex thinking and when to go through short cuts and find an easy solution.

5. They have clear definition of what the problem is: They can specifically identity the problem.

6. They use the power of words to connect with people: They are socially well developed and find ways to connect with people and try to find happy-middle solutions.

7. They don't create problems for others: They understand that to have their problem solved they can't create problems for others. Good problems solvers who create fair solutions make a conscious effort not to harm others for a self-interest intention. They know such acts will have long term consequences even if the problem is temporarily solved.

8. They do prevention more than intervention: Good problem solvers have a number of skills to prevent problems from happening in the first place. They usually face less drama, conflict, and stressful situations since they have clear boundaries, don't let their rights violated and do not violate other people's rights. They are more of a positive thinker so naturally they are surrounded with more positivity and have more energy to be productive.

9. They explore their options: They see more than one solution to a problem and find new and productive ways to deal with new problems as they arise. They also have a backup plan if the first solution does not work and can ask for support and advise when needed.

10. They have reasonable expectations: Good problem solvers have reasonable expectations as to what the solution would be. They understand that there are many elements effecting a situation and that idealistic ways of thinking and going about solving a problem will be counterproductive.

At the end, good problem solvers do not have too many irrational fears when dealing with problems. They can visualize the worst case scenario, work their way out of it and let go of the fear attached to it. Fear can make your logic and intuition shady and your decisions unproductive.

Support HuffPost

Our 2024 coverage needs you, your loyalty means the world to us.

At HuffPost, we believe that everyone needs high-quality journalism, but we understand that not everyone can afford to pay for expensive news subscriptions. That is why we are committed to providing deeply reported, carefully fact-checked news that is freely accessible to everyone.

Whether you come to HuffPost for updates on the 2024 presidential race, hard-hitting investigations into critical issues facing our country today, or trending stories that make you laugh, we appreciate you. The truth is, news costs money to produce, and we are proud that we have never put our stories behind an expensive paywall.

Would you join us to help keep our stories free for all? Your contribution of as little as $2 will go a long way.

Can't afford to donate? Support HuffPost by creating a free account and log in while you read.

As Americans head to the polls in 2024, the very future of our country is at stake. At HuffPost, we believe that a free press is critical to creating well-informed voters. That's why our journalism is free for everyone, even though other newsrooms retreat behind expensive paywalls.

Our journalists will continue to cover the twists and turns during this historic presidential election. With your help, we'll bring you hard-hitting investigations, well-researched analysis and timely takes you can't find elsewhere. Reporting in this current political climate is a responsibility we do not take lightly, and we thank you for your support.

Contribute as little as $2 to keep our news free for all.

Dear HuffPost Reader

Thank you for your past contribution to HuffPost. We are sincerely grateful for readers like you who help us ensure that we can keep our journalism free for everyone.

The stakes are high this year, and our 2024 coverage could use continued support. Would you consider becoming a regular HuffPost contributor?

The stakes are high this year, and our 2024 coverage could use continued support. If circumstances have changed since you last contributed, we hope you’ll consider contributing to HuffPost once more.

Already contributed? Log in to hide these messages.

Popular in the Community

From our partner, huffpost shopping’s best finds, more in life.

- Connect with us on LinkedIn

- Our Blog RSS Feed

Stay informed.

Keep up with the latest in careers, hiring and industry developments.

The Top 10 Characteristics of Problem Solvers

September 24th, 2017

Have you ever noticed that some people seem to be natural born problem solvers? Look closer, and you’ll discover that problem solving is more a skill than a gift. Effective problem solvers share ten common characteristics.

1. They have an “attitude”!

Simply expressed, effective problem solvers invariably see problems as opportunities, a chance to learn something new, to grow, to succeed where others have failed, or to prove that “it can be done”. Underlying these attitudes is a deeply held conviction that, with adequate preparation, the right answer will come.

2. They re-define the problem.

Problem solving is a primary consulting skill. Seasoned consultants know that, very often, the initial definition of the problem (by the client) is incorrect or incomplete. They learn to discount statements such as, “Obviously, the problem is that …” and follow their own leadings, but…

3. They have a system.

Perhaps the most common model is the old consulting acronym: DACR/S in which the letters stand for Describe, Analyze, Conclude, and Recommend/Solve. As with many formulas, its usefulness stems from the step-by-step approach it represents. Effective problem solvers take the steps in order and apply them literally. For example, in describing the problem (the first step), they strenuously avoid making premature judgments or ruling out possibilities. In analyzing the information, they are careful that their own prejudices do not interfere. In developing conclusions, they are aware of the need to test them thoroughly. Finally, most astute problem solvers recognize that there is almost always more than one solution, so they develop several alternatives from which to choose.

4. They avoid the experience trap.

The world is becoming increasingly non-linear. Things happen in pairs, triads, and groups and often don’t follow traditional lines from past to present and cause to effect. In such an environment, where synchronicity and simultaneity rather than linearity prevails, past experience must be taken with a grain of salt. Seasoned problem solvers know the pitfalls of relying on what worked in the past as a guide to what will work in the future. They learn to expect the unexpected, illogical, and non-linear.

5. They consider every position as though it were their own.

For effective problem solvers, standing in the other person’s shoes is more than a cute saying. It’s a fundamental way of looking at the problem from every perspective. This ability to shift perspectives quickly and easily is a key characteristic of effective problem solvers. As one especially capable consultant put it, “I take the other fellow’s position, and then I expand upon it until I understand it better than he does”.

6. They recognize conflict as often a prerequisite to solution.

When the stakes are high in a problem situation, the parties are often reluctant to show their hands and cautious about giving away too much. In such instances, managed conflict can be an effective tool for flushing out the real facts of a situation.

7. They listen to their intuition.

Somewhere during the latter stages of the fact-finding (description) process, effective problem solvers experience what can best be called, “inklings”-gut-level feelings about the situation. When this happens, they listen, hypothesize, test and re-test. They realize that, while intuition may be partially innate, effective intuition is overwhelmingly a developed faculty-and they work to develop it!

8. They invariably go beyond “solving the problem”.

On a time scale, just solving the problem at hand brings you to the present, to a point you might call, ground-zero. Truly effective problem solvers push further. They go beyond simply solving the problem to discover the underlying opportunities that often lie concealed within the intricacies of the situation. Implicit in this approach is the premise that every problem is an opportunity in disguise.

9. They seek permanent solutions.

Permanent, as opposed to band-aid solutions, has two characteristics: (1) they address all aspects of the problem, and (2) they are win/win in that they offer acceptable benefits to all parties involved. Symptomatic problem solving, like bad surgery or dentistry, leaves part of the decay untouched, with the result that, over time, it festers and erupts. Just for the record, a permanent solution is one that STAYS solved and doesn’t come back to bite you.

10. They gain agreement and commitment from the parties involved.

It’s easy, in the heady rush of finding “the answer” to a problem, to fail to gain agreement and commitment on the part of everyone involved. For effective problem solvers, just “going along” via tacit agreement isn’t enough. There must be explicit statements from all parties that they concur and are willing to commit to the solution. Agreement and concurrence really constitute a third characteristic of the “permanent” solution discussed above, but they are so often ignored that it is important that they be viewed separately.

Written by Shale Paul, Copyright Coach University. All Rights Reserved.

Share this:

Comments are closed.

- Newsletter Content

- Software Sales Candidates

A Library of Essential Behavioural Training Courses

Explore Library

Are you tired of feeling overwhelmed when faced with complex problems? Do you want to enhance your problem-solving skills and become a master at finding innovative solutions? Look no further courses on problem solving , ! In this blog post, we will delve into the key traits and strategies that can help you unlock your problem-solving potential. Whether it’s navigating through personal or professional challenges, these tried-and-true approaches will empower you to tackle any obstacle with confidence. Get ready to unleash your inner problem-solver and embark on a journey towards success like never before!

What are Problem-Solving Skills?: Defining problem-solving skills and why they are essential for personal and professional growth.

Problem-solving skills are a crucial set of abilities that allow individuals to approach and overcome challenges effectively. They involve the ability to identify, analyze, and solve problems in a logical and systematic manner. These skills are essential for personal and professional growth as they enable individuals to navigate through life’s complexities and achieve their goals.

Defining problem-solving skills can be challenging because it encompasses various cognitive processes such as critical thinking, creativity, decision-making, and reasoning. However, at its core, problem-solving is about finding solutions to issues or obstacles that require some form of action or decision.

These skills are vital in all aspects of life, whether in personal relationships, academics, or the workplace. In personal relationships, being able to resolve conflicts effectively requires problem-solving skills. In academia, students need these skills to excel in their studies by understanding complex concepts and applying them in assignments. In the workplace, employees with strong problem-solving abilities can tackle challenges independently and contribute positively to achieving organizational objectives.

One reason why problem-solving skills are essential for personal growth is that they promote self-reliance. When faced with an issue or obstacle, individuals with strong problem-solving abilities do not rely on others to provide solutions but instead take initiative and find ways to overcome it themselves. This independence leads to increased self-confidence and a sense of accomplishment when successful resolutions are achieved.

Key Traits of Effective Problem Solvers: Exploring the common characteristics shared by individuals who excel at problem-solving.

Effective problem solvers are highly sought after in today’s fast-paced and constantly changing world. Whether it’s in the workplace, academia, or personal life, individuals who possess strong problem solving course are able to navigate challenges and find solutions efficiently. But what makes someone an effective problem solver? What characteristics do they possess that set them apart from others? In this section, we will explore the key traits of effective problem solvers and how they contribute to their success.

Analytical thinking:

One of the key traits of effective problem solvers is their ability to think analytically. They have a natural inclination towards breaking down complex problems into smaller, more manageable parts. This allows them to understand the root cause of a problem and identify potential solutions.

Creative mindset:

Effective problem solvers possess a creative mindset that enables them to approach problems with fresh perspectives. They are not limited by traditional or conventional methods; instead, they actively seek out new ideas and alternative solutions.

Persistence:

Problem-solving requires patience and persistence as not every solution will work on the first try. Effective problem solvers have a tenacious attitude towards finding solutions and are willing to put in the effort required for success.

Curiosity is another common trait among effective problem solvers. They have a natural desire to learn and understand things deeply, which allows them to ask insightful questions that lead them towards better solutions.

– Critical thinking

Critical thinking is an essential skill for mastering problem-solving. It involves using logical and analytical reasoning to evaluate information, identify patterns and connections, and make well-informed decisions. In today’s fast-paced and ever-changing world, the ability to think critically is becoming more valuable than ever before.

At its core, critical thinking requires us to question our assumptions and beliefs, challenge the status quo, and approach problems from different perspectives. It goes beyond simply accepting information at face value but rather encourages us to dig deeper, analyze evidence, and draw our own conclusions. By honing this skill, we can become better problem-solvers by making more informed choices that lead to effective solutions.

One of the key traits of critical thinking is open-mindedness. This means being receptive to new ideas, opinions, and viewpoints without judgment or bias. Being open-minded allows us to consider all possibilities before reaching a conclusion and helps us avoid falling into the trap of confirmation bias – where we only seek out information that confirms our existing beliefs.

– Creativity

Creativity is a key trait that is essential for mastering problem solving course online . It involves thinking outside of the box, coming up with innovative solutions, and approaching problems from different angles. In this section, we will discuss the importance of creativity in problem-solving and provide strategies for enhancing your creative thinking abilities.

Why Creativity Matters in Problem-Solving:

When faced with a complex problem, traditional methods may not always lead to successful solutions. This is where creativity comes into play. By thinking creatively, you are able to break away from conventional ways of solving problems and explore new possibilities. This can lead to more efficient and effective solutions that may have been overlooked otherwise.

Additionally, being creative allows you to approach problems with an open mind and a sense of curiosity rather than being restricted by preconceived notions or biases. This enables you to see the problem from different perspectives and consider all potential solutions before making a decision.

Strategies for Enhancing Creativity:

- Embrace Divergent Thinking: Divergent thinking refers to the ability to generate multiple ideas or solutions for a given problem. To enhance this skill, try brainstorming without any limitations or restrictions. Allow yourself to think freely and come up with as many ideas as possible without judgment.

- Practice Mind Mapping : A mind map is a visual representation of thoughts or ideas connected around a central concept or topic. Using this technique can help you organize your thoughts and make connections between different ideas, leading to more creative solutions.

– Adaptability

Adaptability is a crucial trait for mastering problem-solving skills. In today’s fast-paced and ever-changing world, the ability to adapt to new situations and challenges is essential for success. It involves being open-minded, flexible, and proactive in finding solutions to problems.

One of the main reasons why adaptability is so important for problem-solving is because it allows individuals to approach a problem from different perspectives. When faced with a challenge, adaptable individuals are able to step back and look at the situation objectively, without being limited by their own biases or habits. This enables them to see potential solutions that others may have overlooked. Furthermore, adaptability also involves continuously learning and growing from experiences. Instead of getting stuck in one way of thinking or doing things, adaptable individuals are open to trying new approaches and learning from their mistakes. This not only helps in finding solutions but also allows for personal growth and development.

In addition, being adaptable means being able to adjust quickly when plans change or unexpected obstacles arise. This requires a certain level of resilience and resourcefulness – the ability to think on your feet and come up with creative solutions under pressure. Adaptable individuals are not easily discouraged by setbacks or failures; instead, they use them as opportunities for growth and improvement.

– Persistence

Persistence is a crucial trait for mastering problem-solving skills. It is the ability to continue working towards a solution despite facing obstacles, setbacks, and challenges. In other words, it is the determination and resilience to keep going until you reach your desired outcome.

One of the main reasons why persistence is essential in problem-solving is that not all problems have easy solutions. Some can be complex and require time and effort to solve. Without persistence, one may easily give up when faced with difficulties, leaving the problem unsolved. However, individuals who possess this trait are more likely to find success in problem-solving as they are willing to put in the necessary work and effort.

Moreover, being persistent also means having a growth mindset rather than a fixed mindset. A growth mindset allows one to see setbacks or failures as opportunities for learning and improvement. This mindset enables individuals to view problems as challenges that can be overcome with effort and perseverance instead of insurmountable barriers.

In addition to having the right mindset, there are several strategies that can help cultivate persistence in problem-solving:

1) Break down the problem into smaller parts: Sometimes, problems may seem overwhelming at first glance. Breaking them down into smaller, more manageable chunks makes them less daunting and easier to tackle.

2) Set achievable goals: Setting realistic goals helps individuals stay motivated as they work towards solving a problem step by step. Celebrating each small victory along the way can also boost motivation and determination.

Why choose us?

In today’s fast-paced and constantly changing world, mastering problem-solving skills is crucial for success in any aspect of life. By cultivating key traits such as patience, creativity, and resilience, along with implementing effective strategies like breaking down the problem into smaller steps and seeking out different perspectives, anyone can become a skilled problem-solver. With determination and practice, you too can overcome any challenge that comes your way. So go forth confidently knowing that you have the tools to tackle any problem that may arise.

© 2023 Dynamic Pixel Multimedia Solutions

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Personality traits and complex problem solving: Personality disorders and their effects on complex problem-solving ability

Ulrike kipman.

1 College of Education, Institute of Educational Sciences and Research, Salzburg, Austria

Stephan Bartholdy

2 Department of Psychology, University of Greifswald, Greifswald, Germany

Marie Weiss

3 Department of Psychology, University of Graz, Graz, Austria

Wolfgang Aichhorn

4 Department of Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, Paracelsus Medical Private University, Salzburg, Austria

Günter Schiepek

5 Institute of Synergetics and Psychotherapy Research, Paracelsus Medical Private University, Salzburg, Austria

Associated Data

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Complex problem solving (CPS) can be interpreted as the number of psychological mechanisms that allow us to reach our targets in difficult situations, that can be classified as complex, dynamic, non-transparent, interconnected, and multilayered, and also polytelic. The previous results demonstrated associations between the personality dimensions neuroticism, conscientiousness, and extraversion and problem-solving performance. However, there are no studies dealing with personality disorders in connection with CPS skills. Therefore, the current study examines a clinical sample consisting of people with personality and/or depressive disorders. As we have data for all the potential personality disorders and also data from each patient regarding to potential depression, we meet the whole range from healthy to impaired for each personality disorder and for depression. We make use of a unique operationalization: CPS was surveyed in a simulation game, making use of the microworld approach. This study was designed to investigate the hypothesis that personality traits are related to CPS performance. Results show that schizotypal, histrionic, dependent, and depressive persons are less likely to successfully solve problems, while persons having the additional behavioral characteristics of resilience, action orientation, and motivation for creation are more likely to successfully solve complex problems.

Introduction

A problem arises when a person is unable to reach the desired goal. Problem-solving refers to the cognitive activities aimed at removing the obstacle separating the present situation from the target situation ( Betsch et al., 2011 ). In our daily lives, we are constantly confronted with new challenges and a plethora of possibilities to address them. Accordingly, problem-solving requires the ability to identify these possibilities and select the best option in the unfamiliar situations. It is, therefore, an important competence to deal with new conditions, adapt to changing circumstances, and react flexibly to new challenges ( Kipman, 2020 ).

Even tasks for which the sequence of choices to be taken is relatively straight-forward, such as in the process of navigating to a certain destination in a foreign city or cooperative decision-making during psychotherapy, appear as a highly diversified process, when considered in detail ( Schiepek, 2009 ; Schiepek et al., 2016a ). However, most problems we face in everyday life are not as well defined and do not necessarily have an unambiguous solution. The ability to deal with such sophisticated problems, i.e., complex problem solving (CPS) , is of particular relevance in everyday settings.

Funke (2001 , 2003 , 2012) and Dörner and Funke (2017) , identified five dimensions along which complex problems can be characterized: (i) The complexity of the problem arises from the number of variables contributing to the problem, which in turn affect the number of possible solutions. (ii) The connectivity of the problem arises from the number of interconnections between these variables. (iii) The dynamics of the problem arise from changes in the problem variables or their interconnections over time. These changes can be a result of the person’s actions or are inherent to the problem, i.e., characteristics of the variables themselves or a result of interactions between the variables. (iv) The non-transparency of a problem refers to the extent to which the target situation, the variables involved, their interactions and dynamics cannot be ascertained. (v) Finally, complex problems are usually polytelic , i.e., they have more than one target situation.

Accordingly, CPS requires the ability to model the problem space, i.e., understand which variables are involved and how they are interconnected, the ability to handle a large number of variables at the same time, judge the relevance and success probability of possibilities, identify the interconnections between variables and the inherent dynamics thereof, judge the consequences of one’s own actions with regards to the problem space, and collect relevant knowledge to deal with non-transparency.

Tasks to measure this complex set of abilities were developed by Dörner (1980 , 1986) , who criticized that the measurement of general intelligence tended to use simple tasks that are not comparable with the level of complexity of real-world problems. He proposed measuring intelligent behavior in computerized environments specifically adapted to simulate the properties of sophisticated problems in everyday settings ( Danner et al., 2011b ). cf. Dörner et al. (1983) in research used settings referred to as Microworlds to assess the way participants acted under heterogeneous, dynamic, and non-transparent conditions. Participants were instructed to administrate a tiny German village by the name of Lohhausen by creating the ideal conditions for the village and its inhabitants ( Hussy, 1998 , p. 140–141). This microworld comprised more than 2,000 variables, guaranteeing an elevated level of complexity, which also required a high-level operationalization of CPS. However, the general validity of the performance at Lohhausen turned out to be a questionable issue, since the performance was operationalized as a factor composed of 6 main criteria, some of which were subjective assessments. Accordingly, the parameter definition for CPS performance was rather ambiguous. The reason for this ambiguity is that the vague description of the objective, i.e., to establish a respectable standard of well-being among the inhabitants—gave room for subjective interpretation (cf. Hussy, 1998 , p. 146–150). Since then, the psychometric validity of the CPS performance in complex microworlds has been demonstrated by several researchers (e.g., Wittmann and Hattrup, 2004 ; Danner et al., 2011a ).

Because of the high-translational relevance of the topic, the question arises how and which individual differences contribute to more or less efficient solving of the complex problems, such as Microworlds. Individual differences in problem-solving have been described along a cognitive dimension, i.e., the problem-solving style , and an emotional–motivational dimension, i.e., the problem orientation ( D’Zurilla et al., 2011 ). Cognitively, problems can be solved in a rational style , i.e., systematically and deliberate, in an impulsive style , i.e., careless, hurried, and often incomplete, or in an avoidance style via passivity and inaction leading to procrastination ( D’Zurilla et al., 2002 , as cited in D’Zurilla et al., 2011 ). Emotionally, people with a positive problem orientation , see problems as an opportunity for success, i.e., a “challenge” and are confident that the problem is solvable, and that they will be able to solve it. People with a negative problem orientation view problems as an opportunity for failure, i.e., a “threat” and doubt their ability to solve the problem ( D’Zurilla et al., 2011 ).

Some studies have already related basic personality traits, such as the BIG-5, to the way a person tackles complex problems. For example, it has been demonstrated that individuals who score high in conscientiousness, openness for experience, and extraversion also have higher problem-solving abilities. In contrast, individuals with higher scores in neuroticism show poor problem-solving abilities ( D’Zurilla et al., 2011 ). McMurran et al. (2001) demonstrate that this is a result of the way in which neurotic individuals approach problems. Neuroticisms was significantly associated with an impulsive or avoidant problem-solving style, and a negative problem orientation. Vice versa, Arslan (2016) identified a positive relationship between constructive problem-solving and being extrovert, receptive, and open to new learning experiences, and also high in tolerability and accountability.

The present study seeks to extend these findings to individuals with “extreme” levels of personality traits, i.e., individuals with personality disorders, taking into consideration the way in which personality characteristics manifest in everyday situations, such as work–place situations. Following the most current diagnostic approach to personality disorders as outlined in the ICD-11, the individual accentuations of 9 disorder-relevant personality traits were taken into account, including:

- (i) Paranoid traits , i.e., the extent of mistrust toward others.

- (ii) Schizoid traits , i.e., the inability to express feelings and experience pleasure, resulting in fierce separation from affective contacts and also friends and social gatherings with an excessive preference for the magical worlds.

- (iii) Antisocial traits , i.e., the extent of disregard for social obligations and callous lack of involvement in feelings for others, resulting in aggressive behavior.

- (iv) Borderline traits , i.e., the tendency to act out impulses without regard to consequences, associated with unpredictable and erratic moods.

- (v) Histrionic traits , i.e., the tendency to overdramatize and show a theatrical, exaggerated expression of feelings, suggestibility, egocentricity, hedonism, and a constant desire for recognition, external stimuli, and attention.

- (vi) Dependent traits , i.e., excessive and inappropriate agreeableness ( Costa and McCrae, 1986 ) resulting in major anxiety about separation, feelings of helplessness, and a tendency to subordinate oneself to the desires of others.

- (vii) Schizotypal traits , i.e., extreme levels of introversion, resulting in social disengagement.

- (viii) Obsessive-compulsive (anankastic) traits , i.e., excessive conscientiousness, involving feelings of doubt, perfectionism, and inflexibility.

- (ix) Depressive traits , i.e., the tendency toward persistent feelings of sadness and loss of interest.

Few studies have assessed problem-solving, much less CPS, in patients with personality disorders. Previous research shows, that patients with histrionic and narcissistic personality types show an impulsive problem-solving style, whereas avoidant and dependent individuals show a negative problem orientation ( McMurran et al., 2007 ). In addition, people who are in a depressive mood ( Lyubomirsky et al., 1999 ), or even clinically depressed and anxious have difficulties generating effective solutions to problems ( Marx et al., 1992 ). Accordingly, we hypothesize a negative association between high accentuations of disorder-related personality traits and CPS. The aim of the present study was to explore, which disorders were most severely affected and whether this association also manifested in work-related situations.

Action-orientated problem-solving is particularly required in areas where people are under a lot of stress, for example, in entrepreneurship, team leading in the clinical settings, or firefighting. Especially when a work-related crisis appears, action-oriented problem-solving is important, because it unites handling both novel and routine demands ( Rudolph and Repenning, 2002 , as cited in Rudolph et al., 2009 ). Rudolph et al. (2009) found that only by taking action, information cues become available. Accordingly, both CPS and everyday situations in the work-place require the ability to cope with stressful events and protect oneself from the negative effects of stress, i.e., resilience ( Lee and Cranford, 2008 , as cited in Wagnild and Young, 1993 ; Fletcher and Sarkar, 2013 ). Indeed, individuals with a high trait resilience are more willing to take action in problem-solving ( Li and Yang, 2009 , as cited in Li et al., 2013 ). This is consistent with previous research demonstrating that effective problem-solving abilities go along with high-psychological resilience ( Garcia-Dia et al., 2013 ; Williamson et al., 2013 ; Crowther et al., 2016 , as cited in Pinar et al., 2018 ). Pinar et al. (2018) even found that problem-solving competencies can be increased by increasing psychological resilience and self-confidence levels. Accordingly, identifying which personality disorders are most severely affected in these areas may also provide hints for psychotherapy.

Materials and methods

Participants.

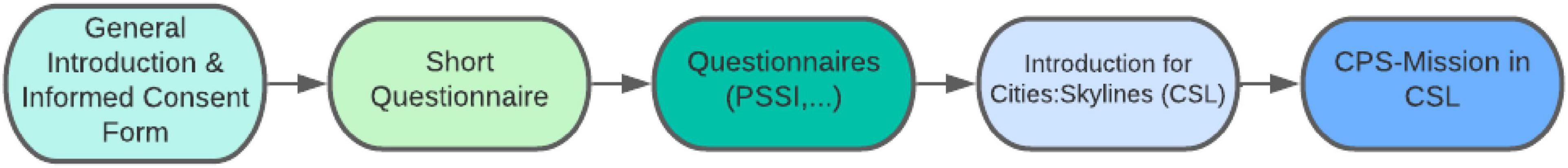

The present study included data from N = 242 adults (49.1% male) with personality disorders and/or depressive disorders, with ages ranging from 17 to 48 years (mean: 26.5 years). The participants were given five assessment batteries and a set of demographic variables, which included game experience. They were also given a commercial complex problem-solving (CPS) game known as Cities: Skylines involving the construction and managing of a city like a mayor would with the goal of growing the city while not running out of money. Participants were patients from psychiatric and psychosomatic hospitals, who got follow-up treatment directly after leaving the hospital. The treatment took place in a panel practice for aftercare where the CPS experiment was done (see Figure 1 ).

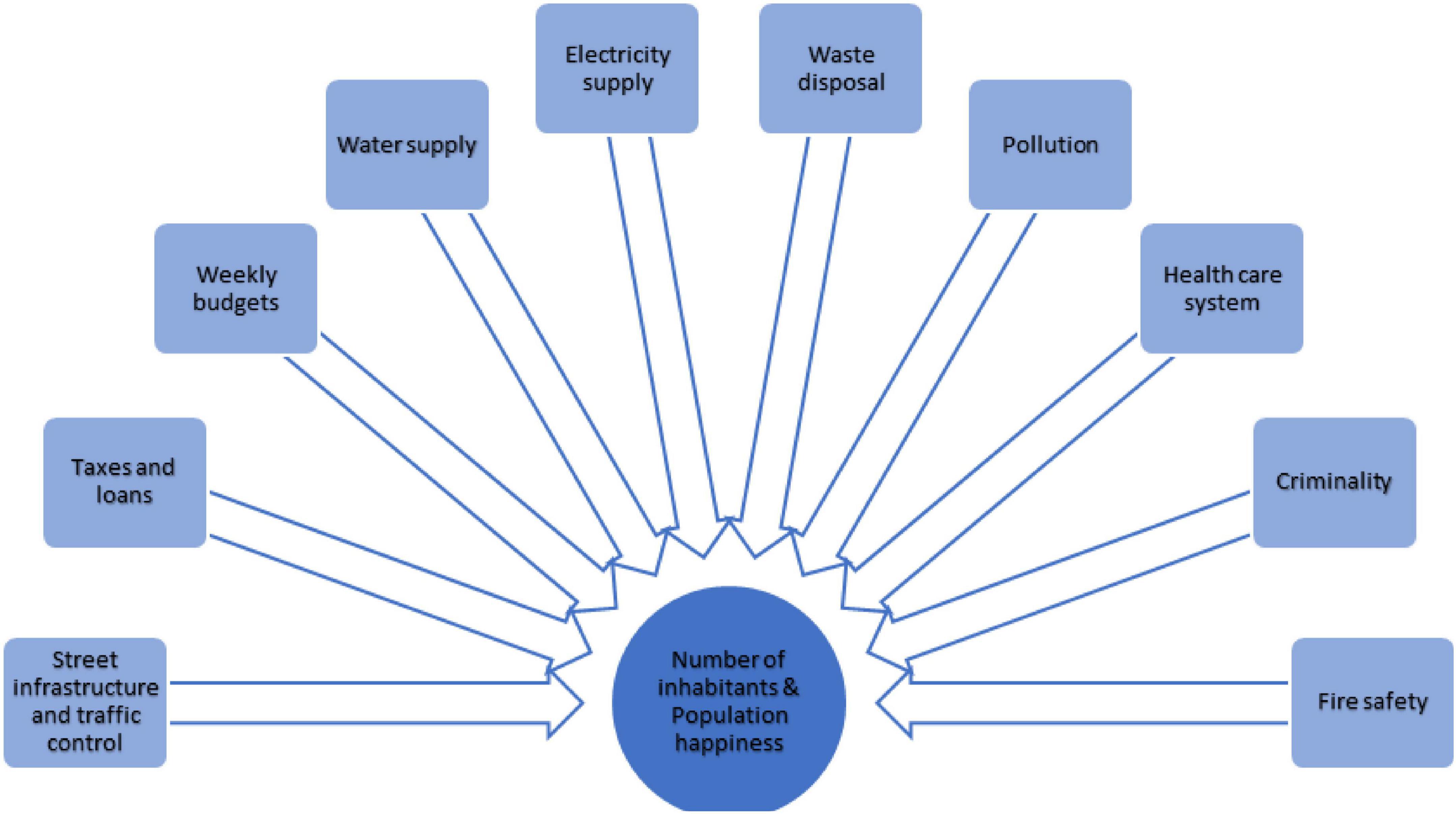

Exemplary model of some (not all) factors that influence the number of inhabitants and the general happiness of the population in Cities: Skylines (CSL). The number of related variables illustrates the complexity, connectivity, and polytely in the simulated environment.

Personality questionnaires

In order to obtain a comprehensive diagnosis and measure disordered personality traits in a continuous fashion, three personality questionnaires were used, including the PSSI, SCID-5-PD, and MMPI-II. While the PSSI scores were used in the statistical analysis, SCID-5-PD scores and MMPI-II scores were used to confirm the PSSI diagnosis. Furthermore, in order to assess the manifestation of disordered personality traits in work-related situations, we used the BIP.

The Persönlichkeits-Stil und Störungs-Inventar (PSSI; Kuhl and Kazen, 2009 ) is a self-report instrument that measures the comparative manifestation of the character traits. These are designed as non-pathological analogs of the personality disorders described in the psychiatric diagnostic manuals DSM-IV and ICD-10. The PSSI comprises 140 items assigned to 14 scales: PN (willful-paranoid), SZ (independent-schizoid), ST (intuitive-schizotypal), BL (impulsive-borderline), HI (agreeable-histrionic), NA (ambitious-narcissistic), SU (self-critical-avoidant), AB (loyal-dependent), ZW (conscientious-compulsive—anankastic), NT (critical-negativistic), DP (calm-depressive), SL (helpful-selfless), RH (optimistic-rhapsodic), and AS (self-assertive-antisocial). Patients rate each item on a 4-point Likert scale (from 0 to 3) and continuous scale values are calculated as the sum of the 10 item ratings belonging to a scale. Accordingly, a maximum value of 30 can be achieved for each scale. In this study, we focused on the nine traits PN, SZ, ST, BL, HI, AB, ZW, DP, and AS, as the other measured traits are not listed as personality disorders in the ICD-10 or DSM-V.

The Strukturiertes Klinisches Interview für DSM-5—Persönlichkeitsstörungen (SCID-5-PD; First et al., 2019 ) is a semi-structured diagnostic questionnaire that can be used to evaluate the 10 personality disorders included in the DSM-5 in clusters A, B, and C, as well as disorders in the category “not otherwise specified personality disorder.” Each DSM-5 criterion is assigned corresponding interview questions to assist the interviewer in assessing the criterion. It is possible to utilize the SCID-5-PD to categorically diagnose personality disorders (present or absent) ( First et al., 2019 ). In addition, regulations are also included which can be used to create dimensional ratings.

The MMPI ® –2 ( Butcher et al., 2000 ) is a revised and completely re-normed version of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI). With the help of the MMPI ® –2, a relatively complete picture of the personality structure can be obtained in an economical way.

The Bochumer Inventar zur berufsbezogenen Persönlichkeitsbeschreibung (BIP; Hossiep and Paschen, 2019 ) measures personality traits in a work-related context. A total of 210 items are assigned to 4 global dimensions including 14 subscales. These include work orientation (diligence, agility, and focus), professional approach ( performance-, creativity-, and management motivation), social competencies (sensitivity, social skills, sociability, teamwork, and assertiveness), and mental constitution (emotional stability, resilience, and self-confidence) on a continuous scale. Patients respond to each item on a 6-point Likert scale.

Game experience

As possible previous experience with the CPS game may affect the level of problem-solving efficiency during the test, participants were asked to rate their previous engagement with simulation-based urban development games on a 4-point Likert scale with response options running from “none” to “very much.” The same poll also featured a listing of 20 symbols from Cities: Skylines, in combination with their meanings (e.g., “no electricity”) for participants to make use of during their quest. At the end, participants were asked to rate their experience based on a 5-point scaling reaching from 1 (extremely simple) to 5 (super challenging). At last, the researcher also marked on each poll sheet, whether (a) the individual patient was able to accomplish the mission (Success, Failure, or Patient Breakup), and (b) the exact time frame of the testing session (morning, afternoon, or evening).

Cities: Skylines (CSL)

The computer-based simulation game Cities: Skylines ( Paradox Interactive, 2015a ), which can be downloaded from Steam for about 30 dollars, explores the construction and management of a city and was implemented in the current study as a Microworld scenario. Much like in the successful microworld Lohhausen ( Dörner et al., 1983 ), gamers in Cities: Skylines basically act in lieu of the city’s mayor, taking over all of his authority and duties. As promised in the user manual, it “offers endless sandbox play in a city that keeps offering new areas, resources, and technologies to explore, continually presenting the player with new challenges to overcome” ( Paradox Interactive, 2015b , p. 4). The game fulfills the parameters of Brehmer and Dörner’s (1993) microworlds and meets the standards of complex problems according to Funke ’s ( 2001; 2012 ). The examples below illustrate the way in which these features are relevant for Cities: Skylines (see Figure 2 ; see also de Kooter, 2015 ; Paradox Interactive, 2015b ):

Procedure of the study.

- (i) Complexity is fulfilled because the system is made up of a variety of components including a vast series of different constructions (areas, basic resources, roads, constructions, electricity, water supplies, etc.), options (fiscal matters, budgeting, credit, traffic management, security, healthcare, and education), and parameters (population density, inhabitant satisfaction, environmental issues, and delinquency). As an example, while purchasing a wind turbine, the participant may weigh related costs, budgeted funds for the week, potential noise pollution, the way the turbine blends into the landscape vs. the rate of efficiency, along with the hardware required to connect the device to the town’s existing network, etc.

- (ii) Connectivity is fulfilled because the parameters in the model are heavily interconnected. Each component is related to at least one other element (see Figure 2 ) implementing a network of correlations and interdependencies. As an example, residential zones should not be located in proximity to wind turbines, as the amount of noise pollution caused by their operation might affect the quality of life in that zone, which again might make the area less attractive and lower the property values.

- (iii) Dynamics are fulfilled because the demands of the population are subject to autonomous change, while other variables, e.g., zoning requirements also depend in part on the actions of the participants. While the dynamics of the game cause the population and the territory of the city to grow, the whole infrastructure becomes inadequate over time and needs to be adapted. Water and electricity infrastructures, the number of schools, clinics, municipal cemeteries, etc., that used to suffice for the population then need to be expanded. Moreover, depending on its frequentation, each building or road has a certain life span until it is left abandoned and will have to be replaced.

- (iv) Non-transparency is not featured as an essential part of the Cities: Skylines gameplay, but is instead primarily caused by its connectivity and intricacy. While playing the game, the number of variables and their interconnections make active exploration essential. Independent of the player’s actions; however, there are also very non-transparent features, such as random death waves or an (unexpectedly) higher incidence of fires in the area following the first construction of a firefighter center by the player.

- (v) Polytely arises since the objective to increase the population of the city requires the simultaneous achievement of a large number of minor tasks, which may be conflicting (e.g., strategic allocation of bus stops for both students and employees). The situation is further complicated by unforeseen complications (e.g., water pollution causing disease spread), which force the player to abandon his/her ongoing task and give full attention to the new issue. The source of the problem must be evaluated while new strategies for potential solutions are weighed against proven approaches. For the current research, each patient was provided with identical settings, including a sizeable, completely functional city with a number of 2,600 residents, 50,000 game money points, and a general population satisfaction level of 90%. Their subsequent task was to boost the population of the cities to 5,000 residents while making sure that the residents were not poorly (as measured by an average satisfaction level of at least 75%) and the bank balance remained positive. On the contrary, the task was left unaccomplished if (a) the population of the urban areas dropped to 1,000, (b) the balance of the account dropped to 0, or (c) the maximum game time of 120 min had elapsed. Patients received the tip, that it was necessary to set priorities and focus on the mission.

Based on the task of raising the number of inhabitants of the city, a parameter of CPS performance was calculated as the average growth of the population relative to the target size of 5,000:

Gamers were instructed not to modify the time settings during the game, to allow for comparable measurements across participants.

Given that the participants were patients from psychiatric and psychosomatic hospitals, many of them lacked game experience. To increase test fairness between patients with different levels of game experience, all the participants were provided with a brief introduction on how to handle a list of fundamental game features:

- • placement of streets, buildings, water pumps, and wind turbines;

- • positioning of roads, structures, water pipes, and turbines;

- • division of zones (housing, businesses, and industries/offices zones) and the mode of bulldozing;

- • structural survey of power, water lines, and waste collection;

- • search for the info stats to view the requirements of the residents;

Statistical analysis

For all the statistical analyses, SPSS version 26.0 (2020) was used.

On the basis of the ICD-11 definition, the personality traits were not analyzed categorically (as before), but dimensionally. To relate the expression of currently recognized personality disorders to performance in CPS, we used correlation analyses between CPS performance and the 9 scale scores of the PSSI (verified by the SCID and MMPI-2) and also the 4 overall dimensions of the BIP. Given the high number of resulting correlations, p -values could be misleading because of the multiple testing. Accordingly, we identified relevant personality traits for CPS using (i) The Bonferonni-correction of p -values and (ii) an effect sizes cut-off of r > 0.25.

In a second step, we explored, which facets of the BIP contributed to the associations with CPS performance in order to get a more fine-grained picture of possible effects.

In sum, we sought to identify the strongest predictors of CPS performance using 3 multivariate regression models with the 9 clinical traits, controlling for gender in the 2nd model and additional game experience in the 3rd model.

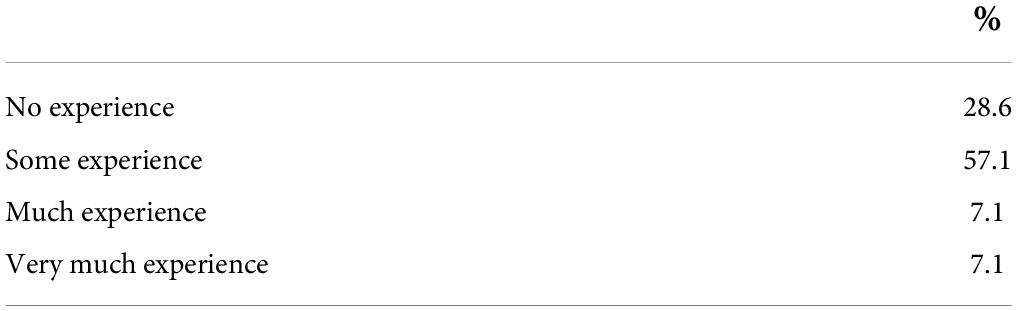

Table 1 lists the experience with urban planning simulation games in the current sample. About 50% of the patients rated the game as “easy” or “rather easy,” 37.5% rated it as “not easy but also not difficult” and 12.6% responded that the game was “difficult” or “very difficult.”

Experience of the sample ( N = 242, N = 210 valid answers).

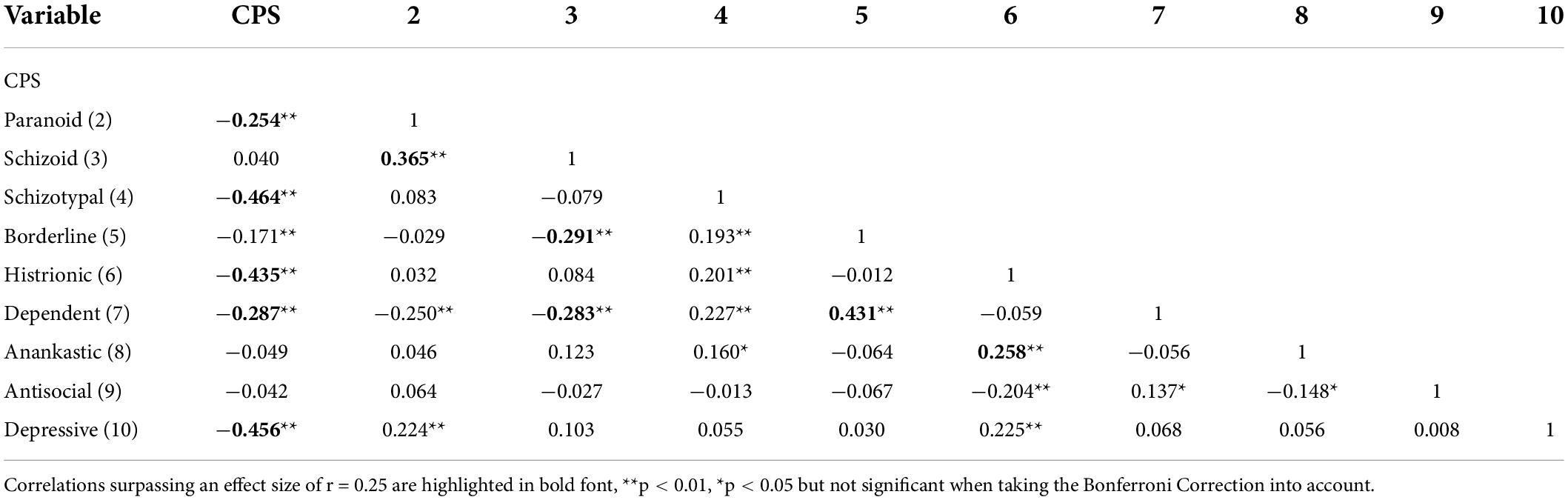

Correlation analyses show that CPS performance was negatively related to schizotypal ( r = −0.46), histrionic ( r = −0.44), and depressive ( r = −0.46) personality accentuations. The higher the expression in any of these areas, the higher the probability of failing in CPS. Effect sizes (: = r ) were > 0.40 for each of these traits (compare Table 2 ). Furthermore, CPS-performance was negatively correlated with the dependent ( r = −0.29) and paranoid ( r = −0.25) personality traits, but coefficients were much lower and therefore of less practical relevance as for schizotypical, histrionic, and depressive traits. Schizoid ( r = 0.04), borderline ( r = 0.17), anankastic ( r = −0.05), and anti-social ( r = −0.04) traits were not significantly associated with the CPS (see Table 3 ).

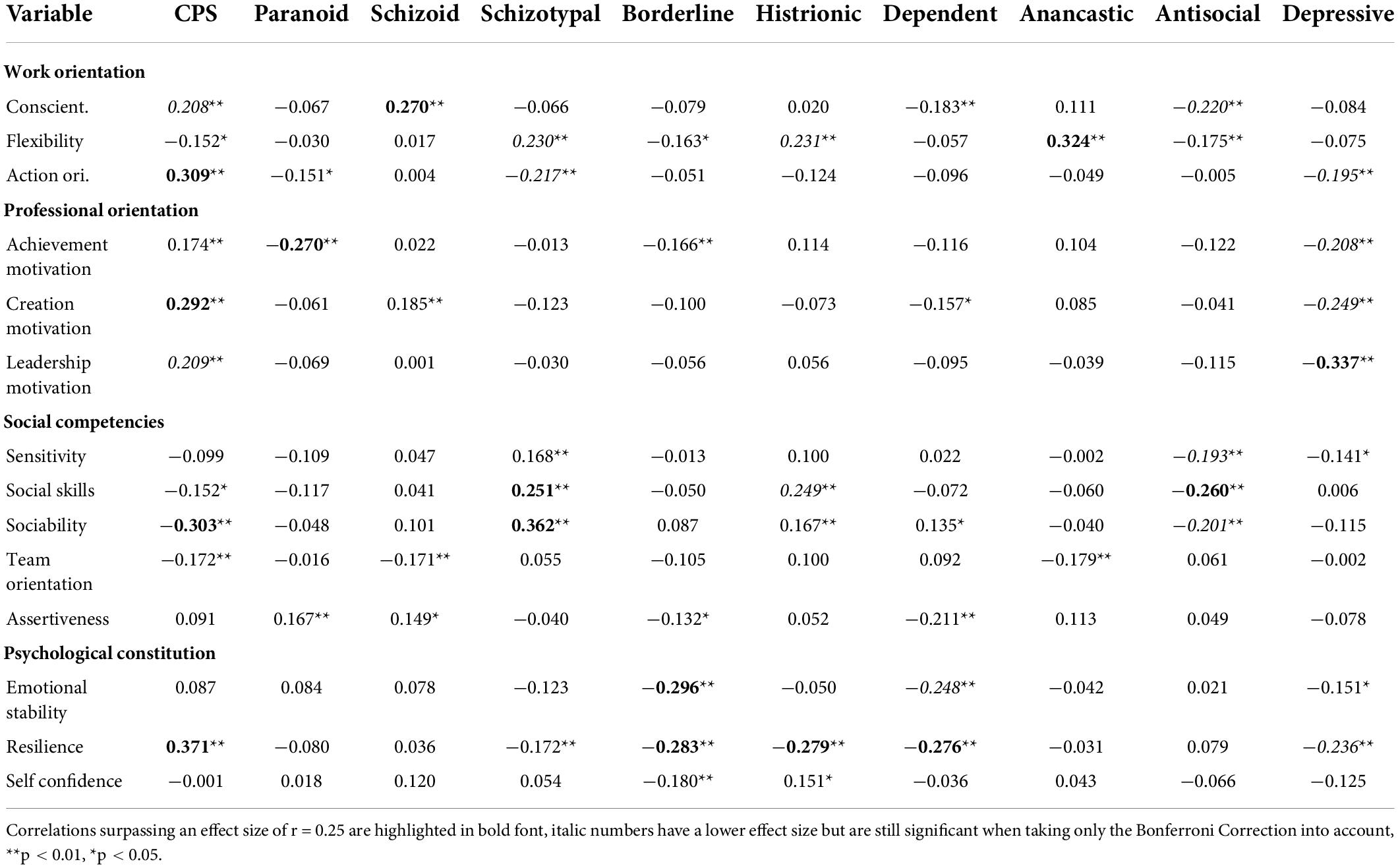

Correlations of CPS and personality disorders with work-related personality manifestations as assessed with the BIP.

Correlations surpassing an effect size of r = 0.25 are highlighted in bold font, italic numbers have a lower effect size but are still significant when taking only the Bonferroni Correction into account, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Correlations between personality traits and CPS performance.

Correlations surpassing an effect size of r = 0.25 are highlighted in bold font, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 but not significant when taking the Bonferroni Correction into account.

Regarding the work-related manifestations of the personality traits, CPS-performance was positively associated with the overall BIP dimensions of work orientation ( r = 0.27), professional orientation ( r = 0.34), and psychological constitution ( r = 0.25), but negatively with the overall BIP dimension social competencies ( r = −0.25). In order to explore these associations further, CPS performance and personality disorders were related to the sub-facet scores of the BIP (see Table 2 ).

Professional orientation was also negatively correlated with depressive traits ( r = −0.40), the psychological constitution was negatively correlated with borderline traits (−0.38), dependent traits (−0.31), and with depressive traits (−0.26).

The results demonstrate that particularly the facets resilience, action orientation, and motivation for creation were positively correlated with successful problem-solving, while sociability and CPS were significantly negatively correlated. The higher the resilience, action orientation and motivation for creation and the lower the sociability, the better was the CPS performance. When we take Bonferroni correction into account, also conscientiousness and motivation for leadership (italic in the table) were negatively correlated with the CPS performance.

Interestingly, the associations between personality disorders and work-related personality expressions were moderate. The strongest associations arose for resilience, which was negatively associated with several personality disorders, particularly, borderline, histrionic, and dependent traits. Focusing on the traits that showed the strongest impairment in CPS, schizotypal traits were associated with high sociability ( r = 0.36) and to a lesser extent with low-action orientation ( r = −0.22), which in turn related to low-CPS performance. Histrionic traits were related to low resilience ( r = −0.28), which in turn related to low-CPS performance. Depressive traits were related to low motivation for creation ( r = −0.25), and also low-leadership motivation ( r = −0.34) and to a lesser extent low-achievement motivation ( r = −0.21), low-action orientation ( r = −0.20), and low resilience ( r = −0.24), which in turn is related to low-CPS performance.

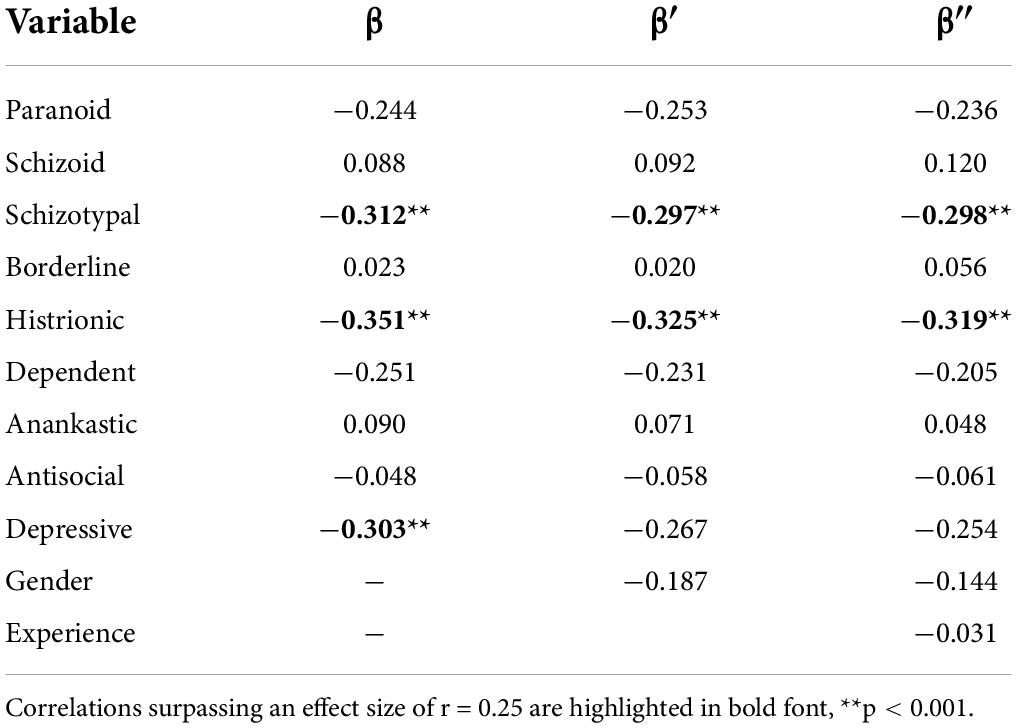

In a combined model with all 9 personality traits (adjusted R 2 = 36.7%), we confirmed that histrionic traits have the biggest negative impact on CPS performance (β = −0.351), followed by schizotypical (β = −0.312) and depressive traits (β = −0.303). Also, in the multiple regression model, dependent and paranoid traits are negatively related to CPS performance. If gender is the part of the model and held constant in a model containing the 9 traits, histrionic traits still have a significant and practical relevant impact of β′ = −0.325. (Condition Index = 24). The same holds true when also taking game experience into account (β ′ ′ = −0.319) see Table 4 .

Combined regression model, β′: controlling for gender, β ′ ′ controlling for gender and game experience.

Correlations surpassing an effect size of r = 0.25 are highlighted in bold font, **p < 0.001.

(Condition Index checking for possible multicollinearity is moderate with CI = 22, 36, so multicollinearity is moderately given, βs are, therefore, interpretable, p -values can be slightly biased, βs with 0.3 and higher found in this model for the 3 traits have for certain a significant and practically relevant impact).

The present study examined the influences of personality traits on the CPS performance in a clinical sample of individuals with a range of different psychiatric diagnoses. The aim of this empirical analysis was to extend previous research on individual differences in CPS to extreme personality traits as observed in personality disorders, and also their manifestation in work-related situations. We explored, which personality dimensions were most strongly associated with impairments in the CPS.

With regards to the clinical personality dimensions (i.e., dimensionally defined personality disorders), statistical analyses revealed that schizotypal, histrionic, dependent, and depressive personality traits were associated negatively with the participants’ performances in the given CPS task (consistent with, e.g., McMurran et al., 2007 ). Previous findings on these relationships were, therefore, further confirmed, specifically in showing that subjects with high levels of depressiveness and anxiety seemed to have more difficulties in finding and executing effective solutions to the given complex problems (e.g., see Marx et al., 1992 ; Lyubomirsky et al., 1999 ).

Unsurprisingly, no single clinical personality structure was associated with better problem-solving performances (as compared with the non-clinical trait levels). As personality disorders are generally linked with increased levels of neuroticism, which subsequently was consistently found to negatively influence problem-solving (e.g., McMurran et al., 2001 ; D’Zurilla et al., 2011 ), this result is also consistent with the general clinical intuition. But, contrary to the previous findings ( D’Zurilla et al., 2011 ), conscientiousness had no significant impact on CPS performance in this sample.

Further analyses gave deeper insights into relationships that were found in the first part of the data analyses. They are especially allowed to draw conclusions for the clinical patients. It was found that higher levels of resilience (consistent with, e.g., Garcia-Dia et al., 2013 ; Williamson et al., 2013 ; Crowther et al., 2016 , as cited in Li and Yang, 2009 ; Pinar et al., 2018 , as cited in Li et al., 2013 ), action orientation, and motivation for creation (e.g., see Eseryel et al., 2014 ) positively influenced the problem-solving performance as additional behavioral characteristics . This indicates that, even for high levels of usually negative personality traits, a person’s ability to successfully solve problems will not be impaired automatically if the person is also very resilient to the effects of negative events and highly action-oriented and motivated when facing problems. Hence, this interpretation is consistent with the conclusions of a study by Güss et al. (2017) , who found that more approach-oriented individuals outperformed avoidance-oriented participants in the complex problems. In this way, these positive traits act against the negative impact of otherwise impairing personality traits or even disorders. Interestingly, sociability was found to have a negative influence on the participants’ performances, while no significant influences on social skills, team orientation, or self-confidence were found. Therefore, it seems to be more comprehensible why some of us deal easily with complex problems and can manage things forward-looking while others do not succeed in making good decisions.

Data availability statement

Ethics statement.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

UK was the main author, did all calculations, research to and wrote the article. SB did the programming of the microworlds and all technical support. MW did the review on the introduction and discussion part. WA and GS served as a consultant. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We thank Martina Mathur and Belinda Pletzer for proofreading and translating.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Arslan C. (2016). Interpersonal problem solving, self-compassion and personality traits in university students. Educ. Res. Rev. 11 474–481. 10.5897/ERR2015.2605 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Betsch T., Funke J., PLessner H. (2011). Denken - urteilen, entscheiden, problemlösen . Berlin: Springer. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brehmer B., Dörner D. (1993). Experiments with computer-simulated microworlds: Escaping both the narrow straits of the laboratory and the deep blue sea of the field study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 9 171–184. 10.1016/0747-5632(93)90005-D [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Butcher J. N., Dahlstrom W. G., Graham J. R., Tellegen A., Kaemmer B. (2000). Minnesota multiphasic personality inventory ® -2. Bern: Huber. [ Google Scholar ]

- Costa P. T., McCrae R. R. (1986). Personality stability and its implications for clincal psychology. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 6 407–423. 10.1016/0272-7358(86)90029-2 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Crowther S., Hunter B., McAra-Couper J., Warren L., Gilkison A., Hunter M., et al. (2016). Sustainability and resilience in midwifery: A discussion paper. Midwifery 40 40–48. 10.1016/j.midw.2016.06.005 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dörner D. (1980). On the difficulties people have in dealing with complexity . Simul. Games 11 , 87–106. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dörner D. (1986). Diagnostik der operativen intelligenz . Diagnostica 32 , 290–308. [ Google Scholar ]

- D’Zurilla T. J., Maydeu-Olivares A., Gallardo-Pujol D. (2011). Predicting social problem solving using personality traits. Pers. Individ. Differ. 50 142–147. 10.1016/j.paid.2010.09.015 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- D’Zurilla T. J., Nezu A. M., Maydeu-Olivares A. (2002). The Social Problem-Solving Inventory-Revised (SPSI-R): Technical Manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems, Inc. [ Google Scholar ]

- Danner D., Hagemann D., Holt D. V., Hager M., Schankin A., Wüstenberg S., et al. (2011a). Measuring performance in dynamic decision making. J. Individ. Differ. 32 225–233. 10.1027/1614-0001/a000055 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Danner D., Hagemann D., Schankin A., Hager M., Funke J. (2011b). Beyond IQ: A latent state-trait analysis of general intelligence, dynamic decision making, and implicit learning. Intelligence 39 323–334. 10.1016/j.intell.2011.06.004 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- de Kooter S. (2015). Cities Skylines Guide: Beginner Tips and Tricks Guide. Available Online at: https://www.gameplayinside.com/strategy/cities-skylines/cities-skylines-guide-beginner-tips-and-tricks-guide/ . [ Google Scholar ]

- Dörner D., Funke J. (2017). Complex problem solving: What it is and what it is not. Front. Psychol. 8 : 1153 . 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01153 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dörner D., Kreuzig H. W., Reither F., Stäudel T. (1983). Lohhausen: Vom Umgang mit Unbestimmtheit und Komplexität. Soziologische Rev. 8 : 93 . [ Google Scholar ]

- Eseryel D., Law V., Ifenthaler D., Ge X., Miller R. (2014). An investigation of the interrelationships between motivation, engagement, and complex problem solving in game-based learning. Educ. Technol. Soc. 17 42–53. [ Google Scholar ]

- First M., Williams J., Smith B., Spitzer R. (2019). SCID-5-PD. Göttingen: Hogrefe. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fletcher D., Sarkar M. (2013). A review of psychological resilience. Eur. Psychol. 18 12–23. 10.1027/1016-9040/a000124 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Funke J. (2001). Dynamic systems as tools for analysing human judgement. Think. Reason. 7 69–89. 10.1080/13546780042000046 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Funke J. (2003). Problemlösendes Denken. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer. [ Google Scholar ]

- Funke J. (2012). “ Complex Problem Solving ,” in Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning , ed. Seel N. M. (Boston, MA: Springer US; ), 682–685. 10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_685 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Garcia-Dia M. J., DiNapoli J. M., Garcia-Ona L., Jakubowski R., O’Flaherty D. (2013). Concept analysis: Resilience. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 27 264–270. 10.1016/j.apnu.2013.07.003 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Güss C. D., Burger M. L., Dörner D. (2017). The role of motivation in complex problem solving. Front. Psychol. 8 : 851 . 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00851 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hossiep R., Paschen M. (2019). Bochumer Inventar zur berufsbezogenen Persönlichkeitsbeschreibung . Göttingern: Hogrefe. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hussy W. (1998). Denken und Problemlösen. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kipman U. (2020). Komplexes problemlösen . Wiesbaden: Springer. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kuhl J., Kazen M. (2009). Persönlichkeits-Stil-und Störungs-Inventar . Göttingen: Hogrefe. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee H. H., Cranford J. A. (2008). Does resilience moderate the associations between parental problem drinking and adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing behaviors?: A study of Korean adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 96 213–221. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.007 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Li M. H., Yang Y. (2009). Determinants of problem solving, social support-seeking, and avoidance: A path analytic model. Int. J. Stress Manag. 16 155–176. 10.1037/a0016844 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Li M. H., Eschenauer R., Yang Y. (2013). Influence of efficacy and resilience on problem solving in the United States, Taiwan, and China. Multicult. Couns. Dev. 41 144–157. 10.1002/j.2161-1912.2013.00033.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lyubomirsky S., Tucker K. L., Caldwell N. D. (1999). Why ruminators are poor problem solvers: Clues from the phenomenology of dysphoric rumination. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 77 1041–1060. 10.1037/0022-3514.77.5.1041 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Marx E. M., Williams J. M., Claridge G. C. (1992). Depression and social problem solving. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 101 78–86. 10.1037/0021-843X.101.1.78 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McMurran M., Duggan C., Christopher G., Huband N. (2007). The relationships between personality disorders and social problem solving in adults. Pers. Individ. Differ. 42 145–155. 10.1016/j.paid.2006.07.002 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McMurran M., Egan V., Blair M., Richardson C. (2001). The relationship between social problem-solving and personality in mentally disordered offenders. Pers. Individ. Differ. 30 517–524. 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00050-7 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Paradox Interactive (2015a). Cities: Skylines. Stockholm, SE: Paradox Interactive. [ Google Scholar ]

- Paradox Interactive (2015b). Cities: Skylines: User Manual. Stockholm, SE: Paradox Interactive. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pinar S. E., Yildirim G., Sayin N. (2018). Investigating the psychological resilience, self-confidence and problemsolving skills of midwife candidates. Nurse Educ. Today 64 144–149. 10.1016/j.nedt.2018.02.014 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rudolph J. W., Repenning N. P. (2002). Disaster dynamics: Understanding the role of quantity in organizational collapse. Adm. Sci. Q. 47 1–30. 10.2307/3094889 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rudolph J. W., Morrison J. B., Carroll J. S. (2009). The dynamics of action-oriented problem solving: Linking interpretation and choice. Acad. Manag. Rev. 34 733–756. 10.5465/AMR.2009.44886170 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schiepek G. (2009). Complexity and nonlinear dynamics in psychotherapy. Eur. Rev. 17 331–356. 10.1017/S1062798709000763 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schiepek G., Stöger-Schmidinger B., Aichhorn W., Schöller H., Aas B. (2016a). Systemic case formulation, individualized process monitoring, and state dynamics in a case of dissociative identity disorder. Front. Psychol. Clin. Settings 7 : 1545 . 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01545 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wagnild G. M., Young H. M. (1993). Development and psychometric evaluation of the resilience scale. J. Nurs. Meas. 1 165–178. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Williamson G. R., Health V., Proctor-Childs T. (2013). Vocation, friendship and resilience: A study exploring nursing student and staff views on retention and attrition. Open J. Nurs. 7 149–156. 10.2174/1874434601307010149 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wittmann W. W., Hattrup K. (2004). The relationship between performance in dynamic systems and intelligence. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 21 393–409. 10.1002/sres.653 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- أحاديث نفسية ..الدكتورة أسماء

- الفالدوكسان

- عقار البريستيك

- Clinical Tips

- PSYCHIATRIC Movie reviews

- Psychiatric Cases and Discussion

- C++ Constructors vs destructors

- C++ REading &Writing text files

- MFC binary, structs and pointers tutorial

- C++ modify and delete record

- C++, listbox tutorial

- NetWorking Tutorial

- Packman like Game part(2)

- Packman like game part (3)continued

- Psychiatry Illustrated:

- Medical Psychology

- Quick Guide to Clinical Psychiatry

- Full Photography course:

- Self Development

- الصد عن سبيل الله

- في فضل سور القرآن

- مثل العنكبوت

The Ten Characteristics of Effective Problem Solvers

Why is it that some people seem to be natural born problem solvers? Look closer, and you’ll discover that problem solving is much more of a skill than an art. You, too, can become an effective problem solver for your real estate business and your family if you learn to develop these proven techniques.

1. They have a “can do” attitude!

Simply expressed, effective problem solvers see problems as opportunities, a chance to learn something new, to grow, to succeed where others have failed, or to prove that “it can be done”. Underlying this attitude is a deeply held conviction that, with adequate preparation, the right answer will emerge.

2. They re-define the problem . Problem solving is a primary consulting skill. Seasoned consultants know that the initial definition of the problem very often is incorrect or incomplete. They learn to dig deeper and follow their own instincts. In describing the problem, they strenuously avoid making premature judgments or ruling out possibilities.

3. They have a system .