Disclaimer » Advertising

- HealthyChildren.org

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Description of the MUSP Cohort

Inclusion criteria for original research publications, quality of supporting literature, predictors: maltreatment types, ethical approval, prevalence and co-occurrence of maltreatment subtypes, cognition and education outcomes, psychological and mental health outcomes, addiction and substance use outcomes, sexual health outcomes, physical health, magnitude of effects, abuse, neglect, and cognitive development, psychological maltreatment: emotional abuse and/or neglect, sexual abuse, physical abuse, limitations, conclusions, long-term cognitive, psychological, and health outcomes associated with child abuse and neglect.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- CME Quiz Close Quiz

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Lane Strathearn , Michele Giannotti , Ryan Mills , Steve Kisely , Jake Najman , Amanuel Abajobir; Long-term Cognitive, Psychological, and Health Outcomes Associated With Child Abuse and Neglect. Pediatrics October 2020; 146 (4): e20200438. 10.1542/peds.2020-0438

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Video Abstract

Potential long-lasting adverse effects of child maltreatment have been widely reported, although little is known about the distinctive long-term impact of differing types of maltreatment. Our objective for this special article is to integrate findings from the Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy, a longitudinal prenatal cohort study spanning 2 decades. We compare and contrast the associations of specific types of maltreatment with long-term cognitive, psychological, addiction, sexual health, and physical health outcomes assessed in up to 5200 offspring at 14 and/or 21 years of age. Overall, psychological maltreatment (emotional abuse and/or neglect) was associated with the greatest number of adverse outcomes in almost all areas of assessment. Sexual abuse was associated with early sexual debut and youth pregnancy, attention problems, posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, and depression, although associations were not specific for sexual abuse. Physical abuse was associated with externalizing behavior problems, delinquency, and drug abuse. Neglect, but not emotional abuse, was associated with having multiple sexual partners, cannabis abuse and/or dependence, and experiencing visual hallucinations. Emotional abuse, but not neglect, revealed increased odds for psychosis, injecting-drug use, experiencing harassment later in life, pregnancy miscarriage, and reporting asthma symptoms. Significant cognitive delays and educational failure were seen for both abuse and neglect during adolescence and adulthood. In conclusion, child maltreatment, particularly emotional abuse and neglect, is associated with a wide range of long-term adverse health and developmental outcomes. A renewed focus on prevention and early intervention strategies, especially related to psychological maltreatment, will be required to address these challenges in the future.

Child maltreatment is a major public health issue worldwide, with serious and often debilitating long-term consequences for psychosocial development as well as physical and mental health. 1 In the United States alone, 3.5 million children are reported for suspected maltreatment each year, with an annual substantiated maltreatment rate of 9.1 per 1000 children. 2 Some of the long-term adverse outcomes associated with maltreatment include cognitive disability, anxiety and depression, psychosis, teen-aged pregnancy, addiction disorders, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. 3 Understanding the distinctive impact of differing types of maltreatment may help medical professionals provide more wholistic care and treatment recommendations as well as identify more specific public health targets for primary prevention.

Unfortunately, however, little is known about the long-term effects of differing types of child maltreatment, which include sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect. 4 According to a meta-analysis review, 5 research on child maltreatment has predominantly been focused on sexual abuse, with far less attention paid to psychological maltreatment (emotional abuse and/or neglect) and the co-occurrence of different types of maltreatment. In addition, most of the current evidence is derived from cross-sectional studies, which may be subject to recall bias, 6 – 8 in which an outcome status (such as depression) may influence recall of the exposure (ie, previous maltreatment). Few previous studies have adequately controlled for confounding variables, such as perinatal risk, socioeconomic adversity, parental psychopathology, and impaired early childhood development, which may predispose to both child maltreatment and later adverse health outcomes.

Longitudinal studies offer evidence that is more robust, but these studies are relatively few in number and have generally been limited to certain sociodemographic groups 9 or to specific types of child maltreatment, such as sexual abuse. 1 , 10 Other longitudinal studies have relied on retrospective recall of maltreatment rather than prospectively collected agency-reported data. 11 – 13 In studies in which prospective data have been collected, 7 , 13 – 17 only a few have compared different types of child maltreatment. 7 , 16 , 17

In this special article, we review findings from the Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy (MUSP), a now 40-year longitudinal prenatal cohort study from Brisbane, Australia, involving >7000 women and their children. 18 Unique features of the MUSP include its use of a population-based sample, its use of prospectively substantiated child maltreatment reports, and its consideration of different subtypes of maltreatment. In addition, the study design controlled for a wide range of confounders and covariates, including both maternal and child sociodemographic and mental health variables. This combined body of work, which includes numerous publications over the past decade, has documented a broad range of adverse outcomes associated with child maltreatment, including deficits in cognitive and educational outcomes 19 – 21 ; mental health problems, such as anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), psychosis, delinquency, and intimate partner violence (IPV) 22 – 25 ; substance abuse and addiction 26 – 30 ; sexual health problems 31 ; physical growth and health deficits 32 – 35 ; and overall decreased quality of life. 36

Our purpose for this special article is to compare the effects of 4 differing types of maltreatment on long-term cognitive, psychological, addiction, and health outcomes assessed in the offspring at ∼14 and/or 21 years of age. Rather than providing a systematic review or meta-analysis of the current literature, which would include diverse study designs and purposes, we report and compare the findings of individual articles that used a common data set and standard methodology to study a broad array of outcomes. We particularly highlight the long-term impact of emotional abuse and neglect, which has received far less attention in the literature.

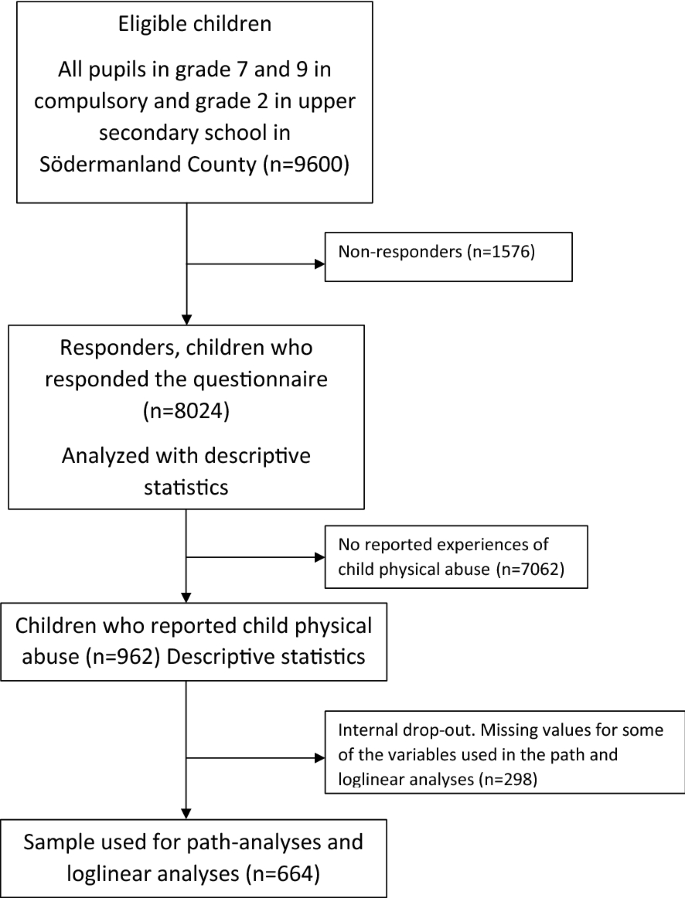

Between 1981 and 1983, 8556 consecutive pregnant women who attended their first prenatal clinic visit at the Mater Mothers’ Hospital in Brisbane, Australia, agreed to participate ( Fig 1 ). After excluding mothers who did not deliver a singleton infant at the Mater Mothers’ Hospital or withdrew consent, the MUSP birth cohort consisted of 7223 mother-infant dyads, who were followed over 2 decades: at 3 to 5 days, 6 months, 5 years, 14 years and 21 years. Midway through the study, this rich data set was anonymously linked to state reports of child abuse and neglect, which identified some form of suspected maltreatment in >10% of cases. 37 Notified cases, which had been referred from the community or by general medical practitioners, were investigated by the Queensland government child protection agency. Substantiated maltreatment was determined after a formal investigation when there was “reasonable cause to believe that the child had been, was being, or was likely to be abused or neglected.” 38 Substantiated maltreatment occurred when a notified case was confirmed for (1) sexual abuse, “exposing a child to or involving a child in inappropriate sexual activities”; (2) physical abuse, “any non-accidental physical injury inflicted by a person who had care of the child”; (3) emotional abuse, “any act resulting in a child suffering any kind of emotional deprivation or trauma”; or (4) neglect, “failure to provide conditions that were essential for the healthy physical and emotional development of a child,” which encompassed physical, emotional and medical neglect. 37

Overview of the MUSP enrollment and testing.

We searched PubMed from inception to April 2020 for published MUSP articles in which agency-reported child maltreatment was evaluated as the predictor of a range of outcomes. Studies needed to meet the following criteria for inclusion in the review: (1) notified or substantiated abuse and neglect was listed as a main predictor variable and (2) outcomes included standardized measurements of cognitive, psychological, behavioral, or health functioning. From ∼340 published MUSP studies, we identified 24 articles dealing with child maltreatment, of which 21 included state-reported maltreatment versus self-reported maltreatment data ( n = 3). Nineteen of the 21 articles met all inclusion criteria and were evaluated in this review ( Fig 2 ). One study was excluded because it only examined outcomes associated with sexual abuse. 8 Another article was excluded because its outcome measures were similar to another included study. 29

![child abuse for research paper FIGURE 2. Published studies from the Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy, linking long-term outcomes with specific maltreatment subtypes (adjusted coefficients or odds ratios ± 95% confidence intervals). CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale; CI, confidence interval; N, number of offspring in sample; N(Mal), number of offspring who experienced maltreatment. aIn different articles adjusting for co-occurrence of maltreatment subtypes was handled in different ways: (1) statistical adjustment: each maltreatment subtype predictor was statistically adjusted for the other maltreatment subtypes (eg, neglect was adjusted for the occurrence of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse) and is reflected in the table’s odds ratios and coefficients; (2) exclusive categories: different combinations of maltreatment types are included in mutually exclusive groups (eg, physical abuse only, physical abuse and emotional abuse only, physical and emotional abuse and neglect [without sexual abuse], etc; see Table 1); (3) nonexclusive categories: maltreatment categories may overlap with other categories (eg, any substantiated abuse [sexual, physical, or emotional] versus any substantiated neglect); and (4) none: no statistical adjustments or combined categories were presented for co-occurring maltreatment subtypes. bAdjusted coefficients (95% CI) were reported as statistical association measures rather than adjusted odds ratios. cCases of notified (rather than substantiated) maltreatment. In the study by Mills et al,26 a sensitivity analysis was performed after exclusion of unsubstantiated cases of maltreatment. The associations between any maltreatment and substance use were similar to those seen in the original analysis after full adjustment. dMedium effect size, based on magnitude of the adjusted odds ratio (2 ≤ odds ratio ≤ 4). eLarge effect size, based on magnitude of the adjusted odds ratio (odds ratio > 4).](https://aap2.silverchair-cdn.com/aap2/content_public/journal/pediatrics/146/4/10.1542_peds.2020-0438/4/m_peds_20200438_f2.jpeg?Expires=1717625277&Signature=YaKUpbIkH4Bx5TR66X5MFDL3k9N6FRq1IW4cpaOl2eJ3qD5kpdIp-dMzCkU0CsNyEF9WvnIk3VZQM~iVsWo6owKkGt2fjrTbVOxuj86ts5dUC1ZHOehDMQVyfqWk1qUTZGm31UjAiRqb5VYXwuNVJ~K8Ggco-rNPp6L6S~XNA89rkMyVZAP-2~AE-c~OoteWamus2MVMO2dQuxh~NAKyWeKo8lwBtlEeWKSzB7aNPCxP4iAvvrh08LPGI5WSBYFIrAhPulOG4g~QH~g4dWLnsV6CjBGW~tTfas7y0Tf2~SxDC1b0EuavDMW5mEFZMlhfZ3KivCV6hDIVnFHTWnP~Fg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Published studies from the Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy, linking long-term outcomes with specific maltreatment subtypes (adjusted coefficients or odds ratios ± 95% confidence intervals). CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale; CI, confidence interval; N , number of offspring in sample; N (Mal) , number of offspring who experienced maltreatment. a In different articles adjusting for co-occurrence of maltreatment subtypes was handled in different ways: (1) statistical adjustment: each maltreatment subtype predictor was statistically adjusted for the other maltreatment subtypes (eg, neglect was adjusted for the occurrence of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse) and is reflected in the table’s odds ratios and coefficients; (2) exclusive categories: different combinations of maltreatment types are included in mutually exclusive groups (eg, physical abuse only, physical abuse and emotional abuse only, physical and emotional abuse and neglect [without sexual abuse], etc; see Table 1 ); (3) nonexclusive categories: maltreatment categories may overlap with other categories (eg, any substantiated abuse [sexual, physical, or emotional] versus any substantiated neglect); and (4) none: no statistical adjustments or combined categories were presented for co-occurring maltreatment subtypes. b Adjusted coefficients (95% CI) were reported as statistical association measures rather than adjusted odds ratios. c Cases of notified (rather than substantiated) maltreatment. In the study by Mills et al, 26 a sensitivity analysis was performed after exclusion of unsubstantiated cases of maltreatment. The associations between any maltreatment and substance use were similar to those seen in the original analysis after full adjustment. d Medium effect size, based on magnitude of the adjusted odds ratio (2 ≤ odds ratio ≤ 4). e Large effect size, based on magnitude of the adjusted odds ratio (odds ratio > 4).

Each of the reviewed articles followed Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for the conduct of cohort studies. 41 The quality of the studies was also evaluated by using a modified version of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, which is used to assess the following domains: sample representativeness and size, comparability between respondents and nonrespondents, ascertainment of outcomes, and statistical quality. 42 On the basis of this assessment, all of the MUSP studies were determined to be of low risk of bias, with a score of 4 out of 5 points ( Supplemental Information ).

In all but 2 studies (which used notified maltreatment 21 , 26 ) events were dichotomized and coded as substantiated maltreatment versus no substantiated maltreatment. According to a validated classification of maltreatment types, 43 specific categories and co-occurring forms of childhood maltreatment 44 were used to predict outcomes. In 2 studies, 19 , 20 all types of abuse were combined into 1 category and compared to neglect, whereas in another study, sexual abuse was compared to any combination of nonsexual maltreatment. 21 In 2 other studies, 26 , 40 emotional abuse and neglect (examples of psychological maltreatment) were combined, partly because of overlapping definitional constructs from the government child protection agency (emotional abuse included “emotional deprivation,” and neglect included the failure to provide for “healthy…emotional development”). In all but 2 of the included articles, 25 , 33 co-occurrence of different types of maltreatment was considered, either by examining specific combinations of maltreatment types (in exclusive or nonexclusive overlapping categories) or by statistically adjusting for all remaining types of maltreatment ( Fig 2 ).

All of the odds ratios, mean differences, or coefficients were adjusted for potential confounding variables ( Fig 3 ). All articles adjusted for a variety of sociodemographic variables, such as age, race, education, income, and marital status. Perinatal and/or childhood factors, such as birth weight, gestational age, and breastfeeding status, were used as covariates, particularly in articles in which cognitive and educational outcomes were examined. Psychological and mental health variables (such as internalizing and externalizing behavior problems, maternal depression, chronic stress, or exposure to violence) were primarily included as covariates in mental health outcome studies, especially for psychosis. Addiction studies adjusted for youth and maternal alcohol or tobacco use, among other covariates, and physical health outcome studies adjusted for relevant covariates (such as BMI in a study of dietary fat intake and parental height when studying offspring height). In selected articles, maltreatment subtypes were also statistically adjusted for the other types of maltreatment to determine independent effects.

Covariates used in published articles from the MUSP to adjust for possible confounding. a Race: child’s race, parental race, and maternal or paternal racial origin at pregnancy. b Child age: child age and gestational age. c Maternal age: maternal age at the first visit clinic or at pregnancy. d Maternal education: maternal education (prenatal or at birth). e Family income: annual family income, familial income over the first 5 years or family poverty before birth or over the first 5 years of life, family income before birth, and annual family income. f Maternal marital status and social support: same partner at birth and 14 years and social support at 5 years. g Maternal depression: maternal depression during pregnancy, 3- to 6-month follow-up, or 21-year follow-up; chronic maternal depression. h Maternal alcohol use: maternal alcohol use at 3- to 6-month or 14-year follow-up and binge drinking. i Maternal cigarette use: cigarette use during pregnancy, 6 months postpartum, or at 14-year follow-up. ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale; IPV, intimate partner violence. Covariates used in published articles from the MUSP to adjust for possible confounding.

A total of 46 outcomes were assessed at 14 years ( n = 5200) and/or 21 years ( n = 3778) ( Fig 1 ) and were grouped into 5 domains ( Fig 2 ):

Cognition and education outcomes included reading ability and perceptual reasoning measured in adolescence, and, at age 21, receptive verbal intelligence and failure to complete high school or be either enrolled in school or employed; attention problems were measured at both time points.

Psychological and mental health outcomes at 21 years included internalizing and externalizing behavior problems (which were also assessed at 14 years), lifetime anxiety disorder, depressive disorder and symptoms, PTSD, lifetime psychosis diagnosis, psychotic symptoms (such as delusional experience or visual and/or auditory hallucinations), delinquency, experience of IPV or harassment, and overall quality of life.

Addiction and substance use, measured at both time points, included alcohol and cigarette use at 14 and 21 years, and cannabis abuse and/or dependence (including early onset) and injecting-drug use at the 21-year follow-up.

Sexual health was investigated at age 21 in terms of early initiation of sexual experience, having multiple sexual partners, youth pregnancy, and miscarriage or termination.

Physical health outcomes measured at 21 years included symptoms of asthma, high dietary fat intake, poor sleep quality, and height deficits.

The 14-year assessments included a youth questionnaire ( n = 5172) and in-person cognitive testing ( n = 3796). The 21-year visit included an in-person assessment of mental health diagnoses in a subset of the cohort ( n = 2531) with the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), which is based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition criteria 45 ( Fig 1 ). All of the questionnaire and interview measures were validated, except for reported frequencies of specific events (ie, pregnancy, number of cigarettes, etc).

Associations were described by using either adjusted odds ratios or mean differences and coefficients, along with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals, and were plotted to visualize and compare the statistical significance of each association across specific outcome categories and types of maltreatment ( Figs 4 – 8 ).

Child maltreatment and cognition and educational outcomes at 14 and 21 years. A, Adjusted coefficients ± 95% confidence intervals. B, Odds ratios ± 95% confidence intervals. * P < .05.

Child maltreatment and psychological and mental health outcomes at 14 and 21 years. A, Adjusted coefficients ± 95% confidence intervals. B, Odds ratios ± 95% confidence intervals. * P < .05.

Child maltreatment and addiction and substance use outcomes at 14 and 21 years (adjusted odds ratio ± 95% confidence interval). * P < .05.

Child maltreatment and sexual health outcomes at 21 years (adjusted odds ratio ± 95% confidence interval). * P < .05.

Child maltreatment and physical health outcomes at 21 years. A, Adjusted odds ratio ± 95% confidence interval. B, Adjusted coefficients ± 95% confidence interval. * P < .05.

The MUSP was approved by the Human Ethics Review Committee of The University of Queensland and the Mater Misericordiae Children’s Hospital. Ethical approval was obtained separately from the Human Ethics Review Committee of The University of Queensland for linking substantiated child maltreatment data to the 21-year follow-up data.

In this cohort of 7214 children ( Fig 1 ), 7.1% ( n = 511 children) experienced at least 1 episode of substantiated maltreatment. Substantiated sexual abuse was reported in 2.0% ( n = 147), physical abuse in 4.0% ( n = 287), emotional abuse in 3.7% ( n = 267), and neglect in 3.7% of cases ( n = 269) ( Table 1 ). Almost 60% of the children with substantiated maltreatment had multiple substantiated episodes (293 children; range: 2–14 episodes per child; median: 3 episodes per child 37 ). Of the 3778 young adults included in the 21-year follow-up, 4.5% ( n = 171) had a history of substantiated maltreatment, 39 including sexual abuse ( n = 53), physical abuse ( n = 60), emotional abuse ( n = 71), and neglect ( n = 89).

More than half of the children who experienced substantiated maltreatment were reported for ≥2 co-occurring maltreatment types ( Table 1 ). Of the substantiated sexual abuse cases, 57.1% of the children experienced ≥1 additional maltreatment types (84 of 147); for physical abuse, this proportion was 79.1% (227 of 287); for emotional abuse, 83.5% (223 of 267); and for neglect, 73.6% (198 of 269). In particular, emotional abuse and neglect co-occurred, with or without other types of maltreatment, in ∼59% of cases. 46

Nonexclusive and Exclusive Categorization of Child Maltreatment Subtypes (Single and in Combination) Within the MUSP Cohort

Abuse (a combined category) and neglect were both associated with significantly lower cognitive scores at both 14 and 21 years, as well as with negative long-term educational and employment outcomes in young adulthood. 19 , 20 This was after adjusting for factors such as the child’s race, sex, birth weight, breastfeeding exposure, and age; family income; and maternal education and alcohol and/or tobacco use ( Fig 3 ). Specifically, proxy measures of IQ, such as reading ability and perceptual reasoning, at age 14 years were adversely associated with both substantiated abuse and neglect. 19 Sexual abuse was associated with attention problems in adolescence, whereas nonsexual maltreatment was associated with attention problems at both time points. 21 Young adults who experienced substantiated child maltreatment had reduced scores on the Peabody Vocabulary Test at 21 years. In terms of educational outcomes in young adulthood, both abuse and neglect manifested a threefold to fourfold increase in odds of failing to complete high school and a twofold to threefold increase in the likelihood of being unemployed at age 21 years 20 ( Figs 2 and 4 ).

During adolescence, physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect were all significantly associated with both internalizing and externalizing behavior problems, although this was not the case for physical abuse notifications without co-occurring emotional abuse or neglect. 22 After adjustment for relevant sociodemographic variables, the associations with emotional abuse and neglect remained significant at 21 years. 39 No statistically significant association was found between sexual abuse and these behavior problems at either time point.

Psychological maltreatment in childhood was associated with all of the other 15 psychological and mental health outcomes in young adulthood, except for delinquency in women. This was true after adjustment for sociodemographic variables and psychological and mental health problems (such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, aggressive behavior problems, and maternal depression or adverse life events, in the case of psychosis and/or IPV exposure outcomes) ( Fig 3 ). Specifically, both emotional abuse and neglect were significantly associated at 21 years with all of the following outcomes: anxiety, depression, PTSD, psychosis (with some exceptions), delinquency in men, and experiencing IPV and harassment (except for neglect). 22 – 25 , 39 Emotional abuse and neglect were the only maltreatment subtypes associated with a significant decrease in quality-of-life scores. 36

The only mental health outcomes associated with sexual abuse were clinical depression, lifetime PTSD, and experiencing physical IPV. 8 , 25 , 39 Physical abuse was associated with externalizing behavior problems and delinquency (in men), internalizing behavior problems and depressive symptoms, experience of IPV, and PTSD 22 , 24 , 25 , 39 ( Figs 2 and 5 ).

Overall, emotional abuse and/or neglect were associated with all categories of substance use and addiction at both 14 and 21 years, whereas physical and sexual abuse were associated with surprisingly few substance abuse outcomes. Specifically, childhood emotional abuse and neglect were associated with adolescent substance use at age 14, including alcohol use and smoking. 26 This was after adjustment for sociodemographic factors and youth and maternal drug use. The association with cigarette and alcohol use persisted from adolescence to adulthood. The category of "any cigarette use" was the only addiction outcome associated with all 4 types of maltreatment. 40 At 21 years, emotional abuse and neglect were both associated with the early onset of cannabis abuse after adjustment for maternal stress and cigarette use. Additionally, physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect all revealed increased odds of cannabis dependence at age 21, with early onset associated with physical abuse and neglect. 28 In contrast, only emotional abuse significantly predicted injecting-drug use in young adult men, after adjustment for maternal alcohol use and depression, whereas all types of substantiated childhood maltreatment were associated with injecting-drug use in women. 27 Sexual abuse was not associated with any addiction or substance use outcome except for cigarette use at 21 years ( Figs 2 and 6 ).

All forms of maltreatment were significantly associated, at 21 years, with early onset of sexual activity and subsequent youth pregnancy. This was after adjustment for factors such as gestational age, youth psychopathology, and drug use. Neglect was the only type of maltreatment associated with having multiple sexual partners and was the maltreatment type most strongly associated with most other sexual health outcomes, especially youth pregnancy. Pregnancy miscarriage was modestly associated with emotional abuse, whereas termination of pregnancy was not associated with any maltreatment subtype 31 ( Figs 2 and 7 ).

Reduced adult height at 21 years, adjusted for parental height, was associated with all maltreatment subtypes except sexual abuse (which was not associated with any of the physical health outcomes). At 21 years, physical abuse was also associated with high dietary fat intake, a risk factor for obesity (adjusted for BMI), and poor sleep quality in men (adjusted for psychopathology and drug use). Asthma at 21 years revealed a modest association with emotional abuse. The combined category of any maltreatment was also associated with high dietary fat intake ( Figs 2 and 8 ).

To estimate the magnitude of potential effects of child maltreatment on long-term outcomes, other studies have used a number of statistical techniques. In one Australian study that used the MUSP and other data sets, the population attributable risk of child maltreatment causing anxiety disorders in men and women, was estimated to be 21% and 31%, respectively, and 16% and 23% for depressive disorders. 46 Similarly, in the MUSP study on cognitive and educational outcomes of maltreated youth, the population attributable risk of child maltreatment leading to “failure to complete high school” was 13%, and 14% for “failure to be in either education or employment at 21 years.” 20

Based on one published metric of effect size using the magnitude of the adjusted odds ratio, 47 77% of the statistically significant associations in this review were considered to have a medium to large effect size (odds ratio ≥2), including 10% with a large effect size (odds ratio >4) ( Fig 2 ).

In summary, over the past decade, the MUSP has revealed that child maltreatment is associated with a broad array of adverse outcomes during adolescence and young adulthood, including the following:

deficits in cognitive development, attention, educational attainment, and employment;

serious mental health problems, including anxiety, depression, PTSD, and psychosis, as well as delinquency and the experience of IPV;

substance use and addiction problems;

sexual health problems; and

physical health limitations and risk.

These results were seen after adjustment for a broad range of relevant sociodemographic, perinatal, psychological, and other risk factors ( Fig 3 ). Many of the studies also adjusted for the other subtypes of child maltreatment and demonstrated that specific maltreatment types were closely associated with particular outcomes.

Significant cognitive delays and educational failure were seen for both abuse and neglect across adolescence and adulthood. In another study, the authors concluded that preexisting cognitive impairments at 3 or 5 years may explain this association, rather than maltreatment per se. 16 However, other research has revealed that children neglected over the first 4 years of life show a progressive decline in cognitive functioning, which is associated with a significantly reduced head circumference at 2 and 4 years of age. 48 In rodent models, contingent maternal behavior is linked with infant cognitive development, and possible mechanisms include increases in synaptic connections within the hippocampus 49 and reduced apoptotic cell loss. 50 Prolonged maternal separation, in contrast, is associated with impaired cognitive development in rodent and primate models. 51 , 52

One of the most striking conclusions from this review was the broad association between emotional abuse and/or neglect and adverse outcomes in almost all areas of assessment ( Fig 2 ). In stark contrast, physical abuse and sexual abuse were associated with far fewer adverse outcomes. Overall, quality of life was lower for those who had experienced emotional abuse and neglect but not for those who had experienced physical or sexual abuse. Although emotional abuse and neglect often co-occur with other types of maltreatment, 46 the associated outcomes were generally robust even after statistical adjustment or separation into differing maltreatment categories ( Fig 2 ).

Emotional abuse and neglect in early childhood may lead to psychopathology via insecure attachment, 53 , 54 which has been associated with externalizing behavior problems 55 and impaired social competence. 56 , 57 Emotional neglect, in particular, may lead to deficits in emotion recognition and regulation, as well as insensitivity to reward, 3 potentially influencing social and emotional development. Neglected children are less able to discriminate facial expressions and emotions, 58 whereas youth who have been emotionally neglected show blunted development of the brain’s reward area, the ventral striatum. 59 Reduced reward activation may predict risk for depression, 59 addiction, 60 and other psychopathologies. 61

Neglect was also associated with the early onset of sexual activity, multiple sexual partners, and youth pregnancy, even after adjustment for other maltreatment subtypes. This suggests that neglect may result in compensatory efforts to obtain sexual intimacy, consistent with other studies revealing higher rates of unprotected sex 62 and adolescent pregnancy in neglected children. 63 In the animal literature, female rodents that experience maternal deprivation tend to have an earlier onset of puberty and increased sexual receptivity, leading to elevated reproductive activity to help offset an environment of higher offspring risk. 64 , 65

As observed elsewhere, 66 sexual abuse was associated with early sexual experimentation and youth pregnancy as well as symptoms of PTSD and depression. Risky sexual behaviors were independent of other types of maltreatment but were not specific for sexual abuse. An additional MUSP study comparing self-reported and agency-notified child sexual abuse revealed consistent associations with major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, and PTSD. 8 The absence of associations with other adverse outcomes, however, may be, in part, due to the lower prevalence of substantiated sexual abuse, especially at the 21-year follow-up.

Outcomes associated with physical abuse differed from those associated with sexual abuse, with increased odds of externalizing behavior problems, and delinquency in men. Jaffee 3 suggests that physical abuse, in particular, may lead to a hypervigilance response to threat, including negative attentional bias, disproportionate to relatively mild threat cues. Studies have revealed that physically abused children show selective attention to anger cues, 67 have difficulty disengaging from them, 58 , 68 and are more likely to misinterpret facial cues as being angry or fearful. 69

Although these studies demonstrated significant associations between maltreatment and a range of long-term outcomes, association does not equal causality. The causal mechanisms proposed above are tentative and may relate to multiple types of maltreatment.

Other limitations should also be considered. Firstly, selective attrition of socioeconomically disadvantaged and maltreated young people was evident in the MUSP cohort ( Supplemental Information ). However, based on multiple imputation calculations and inverse probability weighting of MUSP data, 18 , 70 differences in the rate of loss to follow-up, for both dependent and independent variables, made little difference to either the estimates or their precision, mirroring findings from other longitudinal studies. 71 In addition, the findings were mostly unchanged when using propensity analysis, which is used to assess the effects of nonrandom sampling variation by analyzing the probability of assignment to a particular category within an observational study given the observed covariates. 72 Specifically, the sample was weighted so that it better resembled sociodemographic characteristics at baseline to minimize bias from differential attrition in those with greater socioeconomic disadvantage.

Secondly, differences in the prevalence of specific maltreatment subtypes might have influenced the statistical power to detect true effects, particularly regarding sexual abuse ( Table 1 ).

Finally, the co-occurrence of different types of maltreatment may have impacted the ability to accurately predict the associations between specific types of maltreatment and outcomes. Other studies have revealed that emotional abuse and neglect, in particular, are more likely to co-occur with each other and with other types of maltreatment. 73 However, even in those articles that statistically adjusted for other co-occurring maltreatment subtypes, the associated outcomes linked with emotional abuse and/or neglect were generally robust. In articles that did not adjust for these co-occurrences, some of the strongest associations were still observed for emotional abuse and/or neglect.

Child maltreatment, particularly psychological maltreatment, is associated with a broad range of negative long-term health and developmental outcomes extending into adolescence and young adulthood. Although these data do not establish causality, neurodevelopmental pathways are likely influenced by stress and early social experience through epigenetic mechanisms, which may affect gene expression and regulation and, ultimately, behavior and development. 3 , 74

Understanding the developmental roots of these adverse outcomes may motivate physicians to more systematically inquire about early-life trauma and refer patients to more appropriate treatment services. 75 , 76 Even more importantly, early intervention and prevention programs, such as prenatal and infancy nurse home visiting, 77 have demonstrated, in randomized clinical trials, diminished rates of child abuse and neglect. 78 , 79 Long-term benefits to the offspring include decreased childhood internalizing problems, 80 reduced antisocial behavior and substance abuse in adolescence, 81 and improved cognitive skills extending into young adulthood. 80 , 82 Supporting at-risk parents and young children should thus be an urgent priority.

Dr Strathearn conceptualized and designed the original study linking the Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy data set with substantiated reports of child maltreatment, drafted the special article, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Giannotti assisted in drafting the manuscript and prepared all tables and figures; Drs Mills, Kisely, and Abajobir conceptualized and wrote the original research articles summarized in this article; Dr Najman was the original principal investigator of the Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy; and all authors critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FUNDING: Partially supported by the US National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA026437). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of this institute or the National Institutes of Health. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Composite International Diagnostic Interview

intimate partner violence

Mater-University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy

posttraumatic stress disorder

Competing Interests

Supplementary data.

Advertising Disclaimer »

Citing articles via

Email alerts.

Affiliations

- Editorial Board

- Editorial Policies

- Journal Blogs

- Pediatrics On Call

- Online ISSN 1098-4275

- Print ISSN 0031-4005

- Pediatrics Open Science

- Hospital Pediatrics

- Pediatrics in Review

- AAP Grand Rounds

- Latest News

- Pediatric Care Online

- Red Book Online

- Pediatric Patient Education

- AAP Toolkits

- AAP Pediatric Coding Newsletter

First 1,000 Days Knowledge Center

Institutions/librarians, group practices, licensing/permissions, integrations, advertising.

- Privacy Statement | Accessibility Statement | Terms of Use | Support Center | Contact Us

- © Copyright American Academy of Pediatrics

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

Understanding Child Abuse and Neglect (1993)

Chapter: 1 introduction, 1 introduction.

Child maltreatment is a devastating social problem in American society. In 1990, over 2 million cases of child abuse and neglect were reported to social service agencies. In the period 1979 through 1988, about 2,000 child deaths (ages 0-17) were recorded annually as a result of abuse and neglect (McClain et al., 1993), and an additional 160,000 cases resulted in serious injuries in 1990 alone (Daro and McCurdy, 1991). However tragic and sensational, the counts of deaths and serious injuries provide limited insight into the pervasive long-term social, behavioral, and cognitive consequences of child abuse and neglect. Reports of child maltreatment alone also reveal little about the interactions among individuals, families, communities, and society that lead to such incidents.

American society has not yet recognized the complex origins or the profound consequences of child victimization. The services required for children who have been abused or neglected, including medical care, family counseling, foster care, and specialized education, are expensive and are often subsidized by governmental funds. The General Accounting Office (1991) has estimated that these services cost more than $500 million annually. Equally disturbing, research suggests that child maltreatment cases are highly related to social problems such as juvenile delinquency, substance abuse, and violence, which require additional services and severely affect the quality of life for many American families.

The Importance Of Child Maltreatment Research

The challenges of conducting research in the field of child maltreatment are enormous. Although we understand comparatively little about the causes, definitions, treatment, and prevention of child abuse and neglect, we do know enough to recognize that the origins and consequences of child victimization are not confined to the months or years in which reported incidents actually occurred. For those who survive, the long-term consequences of child maltreatment appear to be more damaging to victims and their families, and more costly for society, than the immediate or acute injuries themselves. Yet little is invested in understanding the factors that predispose, mitigate, or prevent the behavioral and social consequences of child maltreatment.

The panel has identified five key reasons why child maltreatment research should be viewed as a central nexus of more comprehensive research activity.

Research On Child Maltreatment Is Currently Undervalued And Undeveloped

Research in the field of child maltreatment studies is relatively undeveloped when compared with related fields such as child development, so-

cial welfare, and criminal violence. Although no specific theory about the causes of child abuse and neglect has been substantially replicated across studies, significant progress has been gained in the past few decades in identifying the dimensions of complex phenomena that contribute to the origins of child maltreatment.

Efforts to improve the quality of research on any group of children are dependent on the value that society assigns to the potential inherent in young lives. Although more adults are available in American society today as service providers to care for children than was the case in 1960, a disturbing number of recent reports have concluded that American children are in trouble (Fuchs and Reklis, 1992; National Commission on Children, 1991; Children's Defense Fund, 1991).

Efforts to encourage greater investments in research on children will be futile unless broader structural and social issues can be addressed within our society. Research on general problems of violence, substance addiction, social inequality, unemployment, poor education, and the treatment of children in the social services system is incomplete without attention to child maltreatment issues. Research on child maltreatment can play a key role in informing major social policy decisions concerning the services that should be made available to children, especially children in families or neighborhoods that experience significant stress and violence.

As a nation, we already have developed laws and regulatory approaches to reduce and prevent childhood injuries and deaths through actions such as restricting hot water temperatures and requiring mandatory child restraints in automobiles. These important precedents suggest how research on risk factors can provide informed guidance for social efforts to protect all of America's children in both familial and other settings.

Not only has our society invested relatively little in research on children, but we also have invested even less in research on children whose families are characterized by multiple problems, such as poverty, substance abuse, violence, welfare dependency, and child maltreatment. In part, this slower development is influenced by the complexities of research on major social problems. But the state of research on this topic could be advanced more rapidly with increased investment of funds. In the competition for scarce research funds, the underinvestment in child maltreatment research needs to be understood in the context of bias, prejudice, and the lack of a clear political constituency for children in general and disadvantaged children in particular (Children's Defense Fund, 1991; National Commission on Children, 1991). Factors such as racism, ethnic discrimination, sexism, class bias, institutional and professional jealousies, and social inequities influence the development of our national research agenda (Bell, 1992, Huston, 1991).

The evolving research agenda has also struggled with limitations im-

posed by attempting to transfer the results of sample-specific studies to diverse groups of individuals. The roles of culture, ethnic values, and economic factors pervade the development of parenting practices and family dynamics. In setting a research agenda for this field, ethnic diversity and multiple cultural perspectives are essential to improve the quality of the research program and to overcome systematic biases that have restricted its development.

Researchers must address ethical and legal issues that present unique obligations and dilemmas regarding selection of subjects, provision of services, and disclosure of data. For example, researchers who discover an undetected incident of child abuse in the course of an interview are required by state laws to disclose the identities of the victim and offender(s), if known, to appropriate child welfare officials. These mandatory reporting requirements, adopted in the interests of protecting children, may actually cause long-term damage to children by restricting the scope of research studies and discouraging scientists from developing the knowledge base necessary to guide social interventions.

Substantial efforts are now required to reach beyond the limitations of current knowledge and to gain new insights that can improve the quality of social service efforts and public policy decisions affecting the health and welfare of abused and neglected children and their families. Most important, collaborative long-term research ventures are necessary to diminish social, professional, and institutional prejudices that have restricted the development of a comprehensive knowledge base that can improve understanding of, and response to, child maltreatment.

Dimensions Of Child Abuse And Neglect

The human dimensions of child maltreatment are enormous and tragic. The U.S. Advisory Board on Child Abuse and Neglect has called the problem of child maltreatment ''an epidemic" in American society, one that requires a critical national emergency response.

The scale and severity of child abuse and neglect has caused various public and private organizations to mobilize efforts to raise public awareness of individual cases and societal trends, to improve the reporting and tracking of child maltreatment cases, to strengthen the responses of social service systems, and to develop an effective and fair system for protecting and offering services to victims while also punishing adults who deliberately harm children or place them in danger. Over the past several decades, a growing number of state and federal funding programs, governmental reports, specialized journals, and research centers, as well as national and international societies and conferences, have examined various dimensions of the problem of child maltreatment.

The results of these efforts have been inconsistent and uneven. In addressing aspects of each new revelation of abuse or each promising new intervention, research efforts often have become diffuse, fragmented, specific, and narrow. What is lacking is a coordinated approach and a general conceptual framework that can add new depth to our understanding of child maltreatment. A coordinated approach can accommodate diverse perspectives while providing direction and guidance in establishing research priorities and synthesizing research knowledge. Organizational mechanisms are also needed to facilitate the application and integration of research on child maltreatment in related areas such as child development, family violence, substance abuse, and juvenile delinquency.

Child maltreatment is not a new problem, yet concerted service, research, and policy attention toward it is just beginning. Although isolated studies of child maltreatment appeared in the medical and sociological literature in the first half of the twentieth century, the publication of "The Battered Child Syndrome" by C. Henry Kempe and associates (1962) is generally considered the first definitive paper in the field in the United States. The efforts of Kempe and others to publicize disturbing medical experience with child abuse and neglect led to the passage of the first Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act in 1974 (P.L. 93-247). The act, which has been amended several times (most recently in 1992), established a governmental program designed to guide and consolidate national and state data collection efforts regarding reports of child abuse and neglect, conduct national surveys of household violence, and sponsor research and demonstration programs to prevent, identify, and treat child abuse and neglect.

However, the federal government's leadership role in building a research base in this area has been complicated by changes and inconsistencies in research plans and priorities, limited funding, politicized peer review, fragmentation of effort among various federal agencies, poorly scheduled proposal review deadlines, and bias introduced by competing institutional objectives. 1 The lack of comprehensive, long-term planning for a research base has resulted in a field characterized by contradictions, conflict, and fragmentation. The role of the National Center for Child Abuse and Neglect as the lead federal agency in supporting research in this field has been sharply criticized (U.S. Advisory Board, 1991). Many observers believe that the federal government lacks leadership, funding, and an effective research program for studies on child maltreatment.

The Complexity Of Child Maltreatment

Child maltreatment was originally seen in the form of "the battered child," often portrayed in terms of physical abuse. Today, four general categories of child maltreatment are generally recognized: (1) physical

abuse, (2) sexual abuse, (3) neglect, and (4) emotional maltreatment. Each category covers a range of behaviors, as discussed in Chapter 2.

These four categories have become the focus of separate studies of incidence and prevalence, etiology, prevention, consequences, and treatment, with uneven development of research within each area and poor integration of knowledge across areas. Each category has developed its own typology and framework of reference terms, revealing certain similarities (such as the importance of developmental perspectives in considering the consequences of maltreatment) but also important differences (such as the predatory behavior associated with some forms of sexual abuse that do not appear in the etiology of other forms of child maltreatment).

In addition to the category of child maltreatment, the duration, source, intensity, timing, and situational context of incidents of child victimization are now recognized as important factors in studying the origin and consequences of child maltreatment. Yet information about these factors is rarely requested or recorded by social agencies or health professionals in the process of identifying or documenting reports of child maltreatment. Furthermore, research is often weakened by variation in research definitions of child maltreatment, bias in the recruitment of research subjects, the absence of information regarding circumstances surrounding maltreatment reports, the absence of measures to assess selected variables under study, and the absence of a developmental perspective in many research studies.

The co-occurrence of different forms of child maltreatment has been examined only to a limited extent. Relatively little is known about areas of similarity and differences in terms of causes, consequences, prevention, and treatment of selected types of child abuse and neglect. Inconsistencies in definitions often preclude comparative analyses of clinical studies. For example, studies of sexual abuse have indicated wide variations in its prevalence, often as a result of differences in the types of behavior that might be included in the definition adopted by each research investigator. Emotional abuse is also a matter of controversy in some quarters, primarily because of broad variations in its definition.

Research on child maltreatment is also complicated by the fragmentation of services and responses by which our society addresses specific reports of child maltreatment. Cases may involve children who are victims or witnesses to single or repeated incidents of child abuse and neglect. Sadly, child maltreatment often involves various family members, relatives, or other individuals who reside in the homes or neighborhoods of the affected children. Adult figures may be perpetrators of offensive incidents or mediators in intervention or prevention efforts.

The importance of the social ecological framework of the child has only recently been recognized in studies of maltreatment. Responses to child abuse and neglect involve a variety of social institutions, including commu-

nities, schools, hospitals, churches, youth associations, the media, and other social structures that provide services for children. Such groups and organizations present special intervention opportunities to reduce the scale and scope of the problem of child maltreatment, but their activities are often poorly documented and uncoordinated. Finally, governmental offices at the local, state, and federal levels have legal and social obligations to develop programs and resources to address child maltreatment, and their role is critical in developing a research agenda for this field.

In the past, the research agenda has been determined predominantly by pragmatic needs in the development and delivery of treatment and prevention services rather than by theoretical paradigms, a process that facilitates short-term studies of specialized research priorities but impedes the development of a well-organized, coherent body of scientific knowledge that can contribute over time to understanding fundamental principles and issues. As a result, the research in this field has been generally viewed by the scientific community as fragmented, diffuse, decentralized, and of poor quality.

Selection of Research Studies

The research literature in the field of child maltreatment is immense—over 2000 items are included in the panel's research bibliography, a portion of which is referenced in this report. Despite this quantity of literature, researchers generally agree that the quality of research on child maltreatment is relatively weak in comparison to health and social science research studies in areas such as family systems and child development. Only a few prospective studies of child maltreatment have been undertaken, and most studies rely on the use of clinical samples (which may exclude important segments of the research population) or adult memories. Both types of samples are problematic and can produce biased results. Clinical samples may not be representative of all cases of child maltreatment. For example, we know from epidemiologic studies of disease of cases that were derived from hospital records that, unless the phenomenon of interest always comes to a service provider for treatment, there exist undetected and untreated cases in the general population that are often quite different from those who have sought treatment. Similarly, when studies rely on adult memories of childhood experiences, recall bias is always an issue. Longitudinal studies are quite rare, and some studies that are described as longitudinal actually consist of hybrid designs followed over time.

To ensure some measure of quality, the panel relied largely on studies that had been published in the peer-reviewed scientific literature. More rigorous scientific criteria (such as the use of appropriate theory and methodology in the conduct of the study) were considered by the panel, but were not adopted because little of the existing work would meet such selection

criteria. Given the early stage of development of this field of research, the panel believes that even weak studies contain some useful information, especially when they suggest clinical insights, a new perspective, or a point of departure from commonly held assumptions. Thus, the report draws out issues based on clinical studies or studies that lack sufficient control samples, but the panel refrains from drawing inferences based on this literature.

The panel believes that future research reviews of the child maltreatment literature would benefit from the identification of explicit criteria that could guide the selection of exemplary research studies, such as the following:

For the most part, only a few studies will score well in each of the above categories. It becomes problematic, therefore, to rate the value of studies which may score high in one category but not in others.

The panel has relied primarily on studies conducted in the past decade, since earlier research work may not meet contemporary standards of methodological rigor. However, citations to earlier studies are included in this report where they are thought to be particularly useful and when research investigators provided careful assessments and analysis of issues such as definition, interrelationships of various types of abuse, and the social context of child maltreatment.

A Comparison With Other Fields of Family and Child Research

A comparison with the field of studies on family functioning may illustrate another point about the status of the studies on child maltreatment. The literature on normal family functioning or socialization effects differs in many respects from the literature on child abuse and neglect. Family sociology research has a coherent body of literature and reasonable consensus about what constitutes high-quality parenting in middle-class, predominantly White populations. Family functioning studies have focused predominantly on large, nonclinical populations, exploring styles of parenting and parenting practices that generate different kinds and levels of competence, mental health, and character in children. Studies of family functioning have tended to follow cohorts of subjects over long periods to identify the effects of variations in childrearing practices and patterns on children's

competence and adjustment that are not a function of social class and circumstances.

By contrast, the vast and burgeoning literature on child abuse and neglect is applied research concerned largely with the adverse effects of personal and social pathology on children. The research is often derived from very small samples selected by clinicians and case workers. Research is generally cross-sectional, and almost without exception the samples use impoverished families characterized by multiple problems, including substance abuse, unemployment, transient housing, and so forth. Until recently, researchers demonstrated little regard for incorporating appropriate ethnic and cultural variables in comparison and control groups. In the past decade, significant improvements have occurred in the development of child maltreatment research, but key problems remain in the area of definitions, study designs, and the use of instrumentation.

As the nature of research on child abuse and neglect has evolved over time, scientists and practitioners have likewise changed. The psychopathologic model of child maltreatment has been expanded to include models that stress the interactions of individual, family, neighborhood, and larger social systems. The role of ethnic and cultural issues are acquiring an emerging importance in formulating parent-child and family-community relationships. Earlier simplistic conceptionalizations of perpetrator-victim relationships are evolving into multiple-focus research projects that examine antecedents in family histories, current situational relationships, ecological and neighborhood issues, and interactional qualities of relationships between parent-child and offender-victim. In addition, emphases in treatment, social service, and legal programs combine aspects of both law enforcement and therapy, reflecting an international trend away from punishment, toward assistance, for families in trouble.

Charge To The Panel

The commissioner of the Administration for Children, Youth, and Families in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services requested that the National Academy of Sciences convene a study panel to undertake a comprehensive examination of the theoretical and pragmatic research needs in the area of child maltreatment. The Panel on Research on Child Abuse and Neglect was asked specifically to:

The report resulting from this study provides recommendations for allocating existing research funds and also suggests funding mechanisms and topic areas to which new resources could be allocated or enhanced resources could be redirected. By focusing this report on research priorities and the needs of the research community, the panel's efforts were distinguished from related activities, such as the reports of the U.S. Advisory Board on Child Abuse and Neglect, which concentrate on the policy issues in the field of child maltreatment.

The request for recommendations for research priorities recognizes that existing studies on child maltreatment require careful evaluation to improve the evolution of the field and to build appropriate levels of human and financial resources for these complex research problems. Through this review, the panel has examined the strengths and weaknesses of past research and identified areas of knowledge that represent the greatest promise for advancing understanding of, and dealing more effectively with, the problem of child maltreatment.

In conducting this review, the panel has recognized the special status of studies of child maltreatment. The experience of child abuse or neglect from any perspective, including victim, perpetrator, professional, or witness, elicits strong emotions that may distort the design, interpretation, or support of empirical studies. The role of the media in dramatizing selected cases of child maltreatment has increased public awareness, but it has also produced a climate in which scientific objectivity may be sacrificed in the name of urgency or humane service. Many concerned citizens, legislators, child advocates, and others think we already know enough to address the root causes of child maltreatment. Critical evaluations of treatment and prevention services are not supported due to both a lack of funding and a lack of appreciation for the role that scientific analysis can play in improving the quality of existing services and identifying new opportunities for interventions. The existing research base is small in volume and spread over a wide variety of topics. The contrast between the importance of the problem and the difficulty of approaching it has encouraged the panel to proceed carefully, thoroughly distinguishing suppositions from facts when they appear.

Research on child maltreatment is at a crossroads—we are now in a position to merge this research field with others to incorporate multiple perspectives, broaden research samples, and focus on fundamental issues that have the potential to strengthen, reform, or replace existing public policy and social programs. We have arrived at a point where we can

recognize the complex interplay of forces in the origins and consequences of child abuse and neglect. We also recognize the limitations of our knowledge about the effects of different forms of social interventions (e.g., home visitations, foster care, family treatment programs) for changing the developmental pathways of abuse victims and their families.

The Importance Of A Child-Oriented Framework

The field of child maltreatment studies has often divided research into the types of child maltreatment under consideration (such as physical and sexual abuse, child neglect, and emotional maltreatment). Within each category, researchers and practitioners have examined underlying causes or etiology, consequences, forms of treatment or other interventions, and prevention programs. Each category has developed its own typology and framework of reference terms, and researchers within each category often publish in separate journals and attend separate professional meetings.

Over a decade ago, the National Research Council Committee on Child Development Research and Public Policy published a report titled Services for Children: An Agenda for Research (1981). Commenting on the development of various government services for children, the report noted that observations of children's needs were increasingly distorted by the "unmanageably complex, expensive, and confusing" categorical service structure that had produced fragmented and sometimes contradictory programs to address child health and nutrition requirements (p. 15-16). The committee concluded that the actual experiences of children and their families in different segments of society and the conditions of their homes, neighborhoods, and communities needed more systematic study. The report further noted that we need to learn more about who are the important people in children's lives, including parents, siblings, extended family, friends, and caretakers outside the family, and what these people do for children, when, and where.

These same conclusions can be applied to studies of child maltreatment. Our panel considered, but did not endorse, a framework that would emphasize differences in the categories of child abuse or neglect. We also considered a framework that would highlight differences in the current system of detecting, investigating, or responding to child maltreatment. In contrast to conceptualizing this report in terms of categories of maltreatment or responses of the social system to child maltreatment, the panel presents a child-oriented research agenda that emphasizes the importance of knowing more about the backgrounds and experiences of developing children and their families, within a broader social context that includes their friends, neighborhoods, and communities. This framework stresses the importance of knowing more about the qualitative differences between children who suffer episodic experiences of abuse or neglect and those for whom mal-

treatment is a chronic part of their lives. And this approach highlights the need to know more about circumstances that affect the consequences, and therefore the treatment, of child maltreatment, especially circumstances that may be affected by family, cultural, or ethnic factors that often remain hidden in small, isolated studies.

An Ecological Developmental Perspective

The panel has adopted an ecological developmental perspective to examine factors in the child, family, or society that can exacerbate or mitigate the incidence and destructive consequences of child maltreatment. In the panel's view, this perspective reflects the understanding that development is a process involving transactions between the growing child and the social environment or ecology in which development takes place. Positive and negative factors merit attention in shaping a research agenda on child maltreatment. We have adopted a perspective that recognizes that dysfunctional families are often part of a dysfunctional environment.

The relevance of child maltreatment research to child development studies and other research fields is only now being examined. New methodologies and new theories of child maltreatment that incorporate a developmental perspective can provide opportunities for researchers to consider the interaction of multiple factors, rather than focusing on single causes or short-term effects. What is required is the mobilization of new structures of support and resources to concentrate research efforts on significant areas that offer the greatest promise of improving our understanding of, and our responses to, child abuse and neglect.

Our report extends beyond what is, to what could be, in a society that fosters healthy development in children and families. We cannot simply build a research agenda for the existing social system; we need to develop one that independently challenges the system to adapt to new perspectives, new insights, and new discoveries.

The fundamental theme of the report is the recognition that research efforts to address child maltreatment should be enhanced and incorporated into a long-term plan to improve the quality of children's lives and the lives of their families. By placing maltreatment within the framework of healthy development, for example, we can identify unique sources of intervention for infants, preschool children, school-age children, and adolescents.

Each stage of development presents challenges that must be resolved in order for a child to achieve productive forms of thinking, perceiving, and behaving as an adult. The special needs of a newborn infant significantly differ from those of a toddler or preschool child. Children in the early years of elementary school have different skills and distinct experiential levels from those of preadolescent years. Adolescent boys and girls demon-

strate a range of awkward and exploratory behaviors as they acquire basic social skills necessary to move forward into adult life. Most important, developmental research has identified the significant influences of family, schools, peers, neighborhoods, and the broader society in supporting or constricting child development.

Understanding the phenomenon of child abuse and neglect within a developmental perspective poses special challenges. As noted earlier, research literature on child abuse and neglect is generally organized by the category or type of maltreatment; integrated efforts have not yet been achieved. For example, research has not yet compared and contrasted the causes of physical and sexual abuse of a preschool child or the differences between emotional maltreatment of toddlers and adolescents, although all these examples fall within the domain of child maltreatment. A broader conceptual framework for research will elicit data that can facilitate such comparative analyses.

By placing research in the framework of factors that foster healthy development, the ecological developmental perspective can enhance understanding of the research agenda for child abuse and neglect. The developmental perspective can improve the quality of treatment and prevention programs, which often focus on particular groups, such as young mothers who demonstrate risk factors for abuse of newborns, or sexual offenders who molest children. There has been little effort to cut across the categorical lines established within these studies to understand points of convergence or divergence in studies on child abuse and neglect.

The ecological developmental perspective can also improve our understanding of the consequences of child abuse and neglect, which may occur with increased or diminished intensity over a developmental cycle, or in different settings such as the family or the school. Initial effects may be easily identified and addressed if the abuse is detected early in the child's development, and medical and psychological services are available for the victim and the family. Undetected incidents, or childhood experiences discovered later in adult life, require different forms of treatment and intervention. In many cases, incidents of abuse and neglect may go undetected and unreported, yet the child victim may display aggression, delinquency, substance addiction, or other problem behaviors that stimulate responses within the social system.

Finally, an ecological developmental perspective can enhance intervention and prevention programs by identifying different requirements and potential effects for different age groups. Children at separate stages of their developmental cycle have special coping mechanisms that present barriers to—and opportunities for—the treatment and prevention of child abuse and neglect. Intervention programs need to consider the extent to which children may have already experienced some form of maltreatment in order to

evaluate successful outcomes. In addition, the perspective facilitates evaluation of which settings are the most promising locus for interventions.

Previous Reports

A series of national reports associated with the health and welfare of children have been published in the past decade, many of which have identified the issue of child abuse and neglect as one that deserves sustained attention and creative programmatic solutions. In their 1991 report, Beyond Rhetoric , the National Commission on Children noted that the fragmentation of social services has resulted in the nation's children being served on the basis of their most obvious condition or problem rather than being served on the basis of multiple needs. Although the needs of these children are often the same and are often broader than the mission of any single agency emotionally disturbed children are often served by the mental health system, delinquent children by the juvenile justice system, and abused or neglected children by the protective services system (National Commission on Children, 1991). In their report, the commission called for the protection of abused and neglected children through more comprehensive child protective services, with a strong emphasis on efforts to keep children with their families or to provide permanent placement for those removed from their homes.

In setting health goals for the year 2000, the Public Health Service recognized the problem of child maltreatment and recommended improvements in reporting and diagnostic services, and prevention and educational interventions (U.S. Public Health Service, 1990). For example, the report, Health People 2000 , described the four types of child maltreatment and recommended that the rising incidence (identified as 25.2 per 1,000 in 1986) should be reversed to less than 25.2 in the year 2000. These public health targets are stated as reversing increasing trends rather than achieving specific reductions because of difficulties in obtaining valid and reliable measures of child maltreatment. The report also included recommendations to expand the implementation of state level review systems for unexplained child deaths, and to increase the number of states in which at least 50 percent of children who are victims of physical or sexual abuse receive appropriate treatment and follow-up evaluations as a means of breaking the intergenerational cycle of abuse.

The U.S. Advisory Board on Child Abuse and Neglect issued reports in 1990 and 1991 which include national policy and research recommendations. The 1991 report presented a range of research options for action, highlighting the following priorities (U.S. Advisory Board on Child Abuse and Neglect, 1991:110-113):

This report differs from those described above because its primary focus is on establishing a research agenda for the field of studies on child abuse and neglect. In contrast to the mandate of the U.S. Advisory Board on Child Abuse and Neglect, the panel was not asked to prepare policy recommendations for federal and state governments in developing child maltreatment legislation and programs. The panel is clearly aware of the need for services for abused and neglected children and of the difficult policy issues that must be considered by the Congress, the federal government, the states, and municipal governments in responding to the distress of children and families in crisis. The charge to this panel was to design a research agenda that would foster the development of scientific knowledge that would provide fundamental insights into the causes, identification, incidence, consequences, treatment, and prevention of child maltreatment. This knowledge can enable public and private officials to execute their responsibilities more effectively, more equitably, and more compassionately and empower families and communities to resolve their problems and conflicts in a manner that strengthens their internal resources and reduces the need for external interventions.

Report Overview

Early studies on child abuse and neglect evolved from a medical or pathogenic model, and research focused on specific contributing factors or causal sources within the individual offender to be discovered, addressed, and prevented. With the development of research on child maltreatment over the past several decades, however, the complexity of the phenomena encompassed by the terms child abuse and neglect or child maltreatment has become apparent. Clinical studies that began with small sample sizes and weak methodological designs have gradually evolved into larger and longer-term projects with hundreds of research subjects and sound instrumentation.