University of Birmingham

“ You are an Arabic speaker, well are you interested in undertaking research in Arabic with refugees? ” This was the start of an exciting project for me. Over 10 years, I have been conducting research on vulnerabilities, planning, communities and social inequalities. I never embarked on research in my mother tongue and never with refugees. I was excited that this pioneering research would have a direct impact on the sponsored refugees and help the sponsoring groups to better understand refugee families, their hopes and aspirations as well as their concerns and fears.

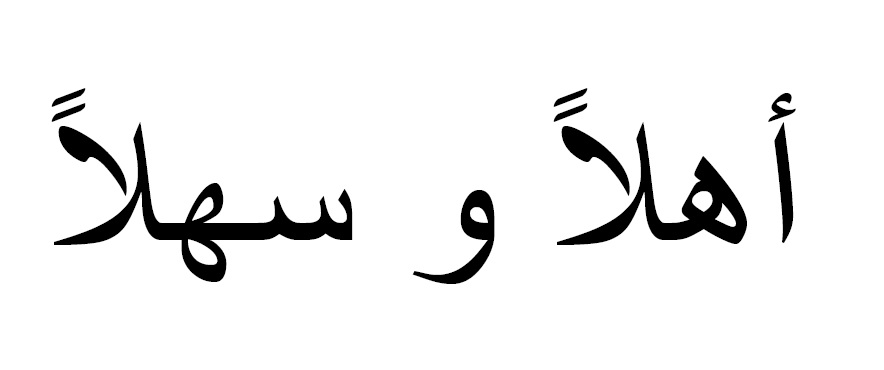

There are many different dialects of spoken Arabic, my Egyptian colloquial Arabic is quite widely understood within Arab speakers in the Middle East. Before conducting my first ever interview two years ago, I wondered who these refugees were. To me, they were the refugees we saw on the news, escaping on boats and surviving inhumane conditions in camps and shelters. I also knew little about sponsorship groups and how their enthusiasm, empathy, activism, and persistence drive the success of the Community Sponsorship Scheme supporting refugee resettlement in the UK. Learning about refugees’ journeys and their gratitude towards their sponsor groups for their continuous support was an emotional and unique experience. During the interviews, which were all conducted in Arabic, I was amazed by both the hospitality and rich information the participants shared with me. Ultimately, I was overwhelmed with the idea that this “could have been me”. Perhaps, because we shared the same language or perhaps because of the extraordinarily 'normal' lives families lead before conflict. They had secure jobs, homes and loving families and friends, dreams and aspirations, all of which they lost during the conflict in 2011. They suddenly became refugees.

Throughout more than 60 remarkable interviews, respondents revealed to me details of their experiences during flight from the conflict zone, their expectations about life in the UK and their arrival journey. They recalled the warm welcome of their sponsor groups’ and their settling down experiences. They described to me their daily life situations in their new homes and communities. Moreover, they discussed their first steps in integration, the support they were given and challenges they faced learning the English language. It was very revealing to learn about their experiences in Arabic. They explained details never shared before sometimes with their closest family members and issues they could not translate to their sponsors. Overwhelmed by the help the volunteers and sponsor groups provide them every day, sometimes the respondents felt reluctant to raise concerns about experiences and difficult relationships upon their arrival. They avoid asking for help around some matters because they do not wish to become a burden to their sponsors. However, they always seemed happy to share concerns as well as positive experiences with me without the language or mediator barrier. I felt overwhelmed with responsibility to make their voices heard and the challenge of interpreting the meanings of what they shared.

The bigger task in this research journey was the challenge of interpretation of meanings. Language is used to express meaning but also language influences how meaning is created and understood. For example, many of those interviewed needed to express their experiences and frequently used narratives and metaphors which capture the richness of experience using Arabic. However, metaphors differ from culture to culture and are indeed very much specific to the language. Language does not only influence what can be expressed but also shapes our realities and how we experience the world. Many refugees framed this perfectly, stating that they needed to think in English in order to express the meaning they wanted to communicate. Perhaps, to me, one of the biggest challenges was to interpret the meaning behind these stories and metaphors. As part of a multi-national team of researchers I was responsible for clarifying what interviewees had shared and then relaying this interpretation in English for the research team to design analysis and synthesis. Hence, my task was not only to understand and report findings from the interviews but also to validate my research by making sure that the distance between the meanings as experienced by the refugees and those interpreted in the findings are as close as possible. Thinking and reflection processes by our multi-national research team needed innovation where discussions primarily benefitted from using descriptions to meanings rather than a word for word translation.

Many lessons were learnt throughout this staggering research journey, which required not only my research skills but also my language and personal skills. I am honoured to have been part of the research team undertaking this study and eternally grateful to the kindness and hospitality of both the participant refugees and their sponsor groups. You can read my report at http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/refugeesoncommunitysponsorship . I hope that the information I have relayed does justice to that shared and provides much needed insight into the experience of refugees coming to the UK under the Community Sponsorship Scheme.

Blog written by Dr Sara Hassan, Community Sponsorship Evaluation Researcher, University of Birmingham.

Read more about the Community Sponsorship Evaluation in the Institute for Research into Superdiversity (IRiS) .

Qualitative research in the Arabic language. When should translations to English occur? A literature review

Affiliation.

- 1 Clinical Pharmacy Department, King Saud University, 11523 PO BOX 50351, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

- PMID: 35800471

- PMCID: PMC9254492

- DOI: 10.1016/j.rcsop.2022.100153

Qualitative studies are a valuable approach to exploratory research. Frequently, researchers are required to collect data in languages other than English, which requires a translation process for the results to be communicated to a wider audience. However, language-embedded meaning can be lost in the translation process, and there is no consensus on the optimum timing of translation during the analysis process. Thus, the aim of this paper was to review how researchers conduct qualitative research with Arabic-speaking participants and the timing of data translation. Three databases were searched (PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science) for the period January 2010 to January 2020. Studies were excluded if the data collection was not in Arabic or the study was not qualitative or healthcare related. Thirty-one studies were included, 26 of which translated all transcripts into English and then analyzed the data in English. Five studies transcribed the data in Arabic, analyzed it in Arabic, and then translated the results to English or conducted a parallel analysis. The reason provided for translating the data into English before the analysis was to enable non-Arabic authors to access the data and assist with the analysis. The search results suggest that researchers prefer translating data before analyzing it and are aware of the possibility of losing meaning during the translation process, which might affect the results. A more thoughtful approach to the timing of translation should be undertaken to ensure the subtleties of language are not lost during the analysis of qualitative data.

Keywords: Arabic; Cross-cultural; Healthcare; Interviews; Language; Language barriers; Qualitative research; Translation.

© 2022 The Author.

Publication types

- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Translation of conduct – English–Arabic dictionary

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

(Translation of conduct from the Cambridge English-Arabic Dictionary © Cambridge University Press)

Examples of conduct

Translations of conduct.

Get a quick, free translation!

Word of the Day

hit the road

to leave a place or begin a journey

Searching out and tracking down: talking about finding or discovering things

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

- English–Arabic Noun Verb

- Translations

- All translations

To add conduct to a word list please sign up or log in.

Add conduct to one of your lists below, or create a new one.

{{message}}

Something went wrong.

There was a problem sending your report.

To support our work, we invite you to accept cookies or to subscribe.

You have chosen not to accept cookies when visiting our site.

The content available on our site is the result of the daily efforts of our editors. They all work towards a single goal: to provide you with rich, high-quality content. All this is possible thanks to the income generated by advertising and subscriptions.

By giving your consent or subscribing, you are supporting the work of our editorial team and ensuring the long-term future of our site.

If you already have purchased a subscription, please log in

What is the translation of "conduct" in Arabic?

"conduct" in arabic, conduct {v.t.}.

- volume_up أَدارَ

conduct {noun}

- volume_up تَصَرُّف

conductive {adj.}

- volume_up ناقِل

conducting {adj.}

Conductivity {noun}.

- volume_up نَقْل

Translations

Conduct [ conducted|conducted ] {transitive verb}.

- "a business, campaign"

- "electricity, heat"

- "an orchestra", music

- open_in_new Link to source

- warning Request revision

conductive {adjective}

Conducting {adjective}, context sentences, english arabic contextual examples of "conduct" in arabic.

These sentences come from external sources and may not be accurate. bab.la is not responsible for their content.

Monolingual examples

English how to use "conduct" in a sentence, english how to use "conductive" in a sentence, english how to use "conducting" in a sentence, english how to use "conductivity" in a sentence, synonyms (english) for "conduct":.

- conditioner

- conditioning

- conditions deteriorated

- condolence book

- condolence card

- condominium

- conduct a case

- conduct a search of sb's house

- conduct an autopsy

- conduct electricity

- conduct one's own defense

- conduct oneself

- conductivity

In the Hindi-English dictionary you will find more translations.

Social Login

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.55(1); 2023

- PMC10321193

Translation and population-based validation of the Arabic version of the brief resilience scale

Baian a. baattaiah.

a Department of Physical Therapy, Faculty of Medical Rehabilitation Sciences, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Mutasim D. Alharbi

Monira i. aldhahi.

b Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, College of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Associated Data

Data for the current study will be available upon reasonable request from the principal investigator or corresponding author.

This study aimed to translate the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) into the Arabic language and to assess the reliability and validity of the translated version of the scale among a sample of the Saudi population.

Material and methods

The internal consistency and test–retest reliability of the translated BRS were analyzed. Factor analyses were conducted to examine the factor structure of the scale. Convergent validity was measured by correlating BRS scores with those from the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), and WHO-5 Well-Being Index (WHO-5).

A total of 1072 participants were included in the analysis. The score of the Arabic version showed excellent internal consistency (alpha = 0.98) and good test–retest reliability (ICC = 0.88, 95% CI: 0.82–0.92, p ≤ 0.0001). The results of factor analyses showed that the two-factor model is a good model fit with [CMIN/DF = 9.105; GFI = 0.97; CFI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.09]. The BRS scores were negatively correlated with levels of anxiety ( r = −0.61), depression ( r = −0.6), and stress ( r = −0.53) and positively correlated with levels of satisfaction with life ( r = 0.44) and mental well-being ( r = 0.58).

Conclusions

Our findings firmly support the reliability and validity of the Arabic version of the BRS to be used in research and clinical settings with the Saudi population.

KEY MESSAGES

- Resilience, defined as the ability to bounce back from stressors, is a psychological factor that may buffer the harmful effects of health-related stress.

- The Arabic version of the BRS demonstrates strong reliability and validity for assessing resilience among the Arabic-speaking Saudi population.

- The scale will provide the rehabilitation field in the Arabic-speaking population and other health communities with a tool for research and clinical practice. The scale will also guide the development of strategic plans and psychological protective and rehabilitative intervention protocols for those in health-related stressful circumstances.

Introduction

Resilience, an emerging concept in the psychology of rehabilitation, has been defined in several ways. The term was initially defined as an individual trait involving self-esteem, self-efficacy, well-being, optimism, faith, and self-determination [ 1–7 ]. It was then conceptualized as the capacity of an individual to bounce back, cope, and adjust while undergoing stress to maintain similar levels of functioning, structure, identity, and feedback [ 8–16 ]. An individual’s capacity to cope with and adapt to a stressful situation may buffer the maladaptive effects of stress and anxiety. In other words, people who can quickly recover from and adjust to difficulties are resilient to the harmful effects of stress [ 17 ]. Psychosocial factors can also affect a person’s decision to adapt or maintain the course of their life [ 18 , 19 ].

Several measures have been developed to assess resilience; however, the majority are based on a trait-oriented approach (e.g. the Dispositional Resilience Scale [ 20 ], the Ego-Resiliency Scale (ERS) [ 21 ], Psychological Resilience (PR) [ 22 ], the Resilience Scale for Adults (RSA) [ 23 ], and the Resilience Scale (RS) [ 24 ]). The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) is a widely used measure of resilience, and it has been translated into multiple languages, including Arabic [ 25 , 26 ]. The scale is multidimensional and focuses on measuring the availability of resources and protective factors to maintain or regain mental health despite significant adversities and does not solely focus on one’s ability to bounce back [ 27 , 28 ].

To specifically assess resilience, defined as the ability to bounce back from stress, the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) [ 14 ], first developed by Smith and colleagues, is dominantly used. A critical review of self-reported resilience measures concluded that the BRS is the only scale that measures resilience itself rather than the personal characteristics that may promote positive adaptation. The review also emphasized that the BRS is one of the best available measures in terms of its psychometric ratings [ 29 ].

The BRS is a self-rated assessment that quantifies a person’s ability to bounce back and cope following stressors that might also be related to health [ 14 ]. Its overarching objective is to measure a person’s ability to thrive in the face of adversity, as people who are more resilient are better able to cope with and navigate life’s challenges. Unlike other measures, the BRS is short, concise, and specific; it comprises six items with a possible total score of 6–30. Each item in the scale has the following possible responses: 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree. The validity and reliability of this scale have been examined, and it has demonstrated psychometric properties that efficiently measure resilience [ 14 , 30–32 ].

Until recently, no evidence was available regarding the translation of the BRS into Arabic or the validation of the translated form, although it has been translated into many languages such as German [ 30 ], Malaysian [ 33 ], Portuguese (Brazil) [ 34 , 35 ], French [ 36 ], Spanish [ 32 ], Polish [ 37 ], Dutch [ 38 ], Chinese [ 39 , 40 ], Japanese [ 41 ], Greek [ 42 ], Turkish [ 43 ], and Korean [ 44 ] as well as among the Czechoslovakia population [ 45 ]. The only known resilience scale in Arabic differs from the BRS not only in length and measurement structure but also in its definition of resilience. Therefore, there is no appropriate, short, valid, and reliable Arabic tool to measure resilience as one’s ability to bounce back from stress.

In rehabilitation, resilience may play a major role in recovery, adaptation, positive outcomes, and treatment compliance and execution for multiple health conditions [ 46–49 ], but there is scarce research regarding resilience in Saudi Arabia. Translating and validating this short and easy to administer metric into Arabic will add to the fundamental knowledge pertaining to rehabilitation communities. The assessment process of the scale will ensure the psychometric properties of the BRS and will provide a necessary Arabic-language tool for research and clinical practice that may promote the psychological aspects of rehabilitation in the community and facilitate positive outcomes. This additional data will also benefit the scientific area in which resilience measures are available in different languages and cultures and among various health-related samples.

This study aimed to translate the BRS into Arabic and to measure its psychometric properties to validate it among a sample of the adult Saudi population. We hypothesized that the translated BRS would demonstrate solid internal consistency and intraclass correlations and would be an appropriate measure for use in research and clinical settings among Arabic-speaking populations.

Materials and methods

This research was a cross-sectional study conducted using an electronic survey link distributed to Saudi people living in all regions of Saudi Arabia between September 2021 and January 2022. The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines proposed in the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was reviewed and approved by the Center of Excellence in Genomic Medicine Research (CEGMR) committee for bioethical approval, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia (Registration Number: HA-02-J-003, Reference No 06-CEGMR-Bioeth-2020).

Translation procedures

To translate the BRS into Arabic, we directly contacted the original developer, Bruce W. Smith, and a written permission for use was obtained. The BRS was then translated using the well-established forward–backward translation approach [ 50 ]. First, the scale was translated from English to Arabic (forward translation) by two English-speaking bilingual translators, one from the medical field and the other from a non-medical field. A committee of judges, including the two translators and a research member, then evaluated the pertinence of the items, and the forward-translated version was then translated back into English (backward translation) by two native Arabic-speaking bilingual translators, one from the medical field and the other from a non-medical field. Those translators were blinded to the original English version of the scale. The committee, which also including the two translators and a research member, then revised the backward-translated version, and no significant variations were found when compared against the original English version. The pre-final Arabic version was approved by the committee, consisting of the four translators and research members, after they guaranteed the semantic, idiomatic, cultural, and conceptual equivalence of the translated and original questionnaires.

Pilot testing ensured the readability and understandability of the translated questionnaire and verified that there were no issues related to answering the questions in the pre-final translated version of the BRS. Content validity, which refers to the degree to which a scale is fully representative and has appropriate items to measure the construct that is supposed to measure, and face validity, which refers to the degree of clarity and comprehension of the instructions and language of the scale and its items, were both used in the process of translation [ 51 , 52 ]. To assess the validity of the content, ten experts in the field participated in the assessment. The panel was asked to review and critique the degree of conceptual and semantic equivalence of the instructions, answer structure, and items of the scale in a 4-point Likert scale in which 1 = not relevant, 2 = somewhat relevant, 3 = quite relevant, 4 = highly relevant. The minimum acceptable value for the content validity index (CVI) was 0.80. To assess the face validity of the translated BRS, 32 participants from the intended population were asked to rate the clarity and comprehension of the scale and of each item. The minimum acceptable value for the face validity index (FVI) was 0.80 [ 51–53 ]. Pilot participants indicated that the Arabic version of the BRS was easy to read and understand; therefore, no further modifications have been done.

Sample size

The OpenEpi Info online sample size calculator (Division of Health Informatics and Surveillance and Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory services, GA) was used to compute the required sample size for the further testing conducting in the study. With a two-sided significance level of 95%, margin of error of 5%, and anticipated frequency of 50%, the minimum estimated sample size required for this study was 385 participants. With a 20% potential dropout rate factored into the calculation, the estimated sample size increased to 462 participants [ 54 ].

Participants

All participation in the study was voluntary. A total of 1072 participants were included in the final analyses. The inclusion criteria were as follows: participants were Saudi, lived in Saudi Arabia, aged between 18 and 70 years, and able to read and understand Arabic. Participants who did not meet the study’s inclusion criteria were excluded from participation. An electronic questionnaire was created using an online survey platform (Google Forms). The link to the survey included the Arabic version of the BRS together with other questionnaires assessing theoretically related outcomes and constructs. The link was distributed via email and through various social media platforms (WhatsApp, Twitter). Participants were allowed to answer the questionnaire only once. The principal investigator’s contact information was provided in the questionnaire for any inquiries. The study’s inclusion and exclusion criteria, protocol, and procedures as well as the participants’ rights were explained at the beginning of the survey, and informed consent for inclusion was obtained from all participants before partaking in the study. All participants were assured that their privacy would be respected and that none of their personal information would be disclosed to the public.

The first survey questions elicited sociodemographic data on age, weight, height, gender, educational status, marital status, employment status, and nationality. Health-related questions, such as whether participants engaged in physical activity, smoked cigarettes, or had experienced chronic diseases, were also included in the survey. Thereafter, all participants completed a battery of self-report questionnaires in the same sequence, which altogether took approximately 5–7 minutes to finish. All questionnaires included in the study have been translated into Arabic and validated among the Arabic-speaking population. Permissions to use the included questionnaires, including the BRS, were professionally sought from the concerned authors before the study began.

Brief resilience scale [ 14 ]

The BRS is a self-rated assessment developed to quantify a person’s ability to bounce back from and cope with health-related stressors [ 14 ]. The overarching objective of this test is to measure a person’s ability to thrive in the face of adversity. The BRS was first developed by Smith et al. [ 14 ] and comprises six items with total scores ranging from 6 to 30. Participants score each item as 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, or 5 = strongly agree. The scores for items 2, 4, and 6 should be reverse coded before analysis. The validity and reliability of this scale in multiple languages have been examined, and it has demonstrated excellent psychometric properties that efficiently measure resilience [ 14 , 30–33 , 36 , 43 ].

Hospital anxiety and depression scale [ 55 ]

The HADS is a 14-item, self-administered scale that contains two set of items, one for reporting anxiety and one for reporting depression, based on a four-point response format. Higher scores indicate greater anxiety and depression symptoms. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the Arabic version of the HADS anxiety subscale and HADS depression subscale were 0.83 and 0.77, respectively, both of which indicate acceptable internal consistency reliability [ 56 ].

Satisfaction with life scale [ 57 ]

The SWLS focuses on evaluating an individual’s general satisfaction with their life. The original version was composed of five items with a seven-point Likert-type scale of response ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The Arabic version had a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.79 and a test–retest reliability of 0.83, indicating that it is appropriate for use among an Arabic-speaking population [ 58 ].

Perceived stress scale [ 59 ]

The PSS measures personal stress in relation to life situations. The Arabic version of the scale consists of a 14-item questionnaire with a five-point response scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often), with higher scores indicating higher stress levels. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.80 for the Arabic version of the PSS. The test–retest reliability had an intra-correlation coefficient of 0.90, indicating that the scale is suitable for assessing stress among an Arabic-speaking population [ 59 , 60 ].

WHO-5 well-being index scale [ 61 , 62 ]

The WHO-5 is a five-item, self-administered questionnaire measuring well-being on a six-point Likert scale (0 = at no time; 5 = all the time). Scores range from 0 to 25, with higher scores indicating greater well-being. The Arabic version of the WHO-5 (WHO-5-A) has been shown to be an effective screening tool for detecting depressive episodes in older people, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.87 and a test–retest reliability of 0.73 [ 63 ].

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using statistical software SPSS version 23 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL), and the factor structure was analyzed using AMOS 23. We checked the data for missing data and outliers. Data were presented as mean and standard deviation ( SD ) for continuous variables and as frequencies ( n ) and percentages (%) for categorical variables. The testing of the psychometric proprieties of the Arabic version of the scale was conducted using various analyses, as discussed below.

Internal consistency

Internal consistency measures the correlation of items within the same scale, that is, whether the items that are intended to assess the construct produce similar scores. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used to assess the internal consistency of the scale.

Test–retest reliability

Test–retest reliability measures the stability and consistency of the instrument over time. A retest assessment of the Arabic BRS was carried out 15 days after the baseline assessment. The intra-correlation coefficient (ICC) was used to measure the strength of agreement.

Convergent validity

Convergent validity measures how a specific construct in the Arabic BRS correlates to the established instruments that measure the same construct. Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used to determine the correlation between the different instruments. The HADS, SWLS, PSS, and WHO-5 were used as the established measures.

Construct validity

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed to examine the factor structure of the sample ( n = 170) using the Kaiser–Mayer–Olkin (KMO) measure and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. The factors were considered significant and confirmed to have a satisfactory factor structure by assessing the eigenvalues (above one) and visually examining the scree plot, KMO estimates (above 0.70), and Bartlett’s test ( p ≤ 0.001) [ 64 ].

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed using AMOS software to evaluate the construct validity of the scale ( n = 902) [ 65–67 ]. The model of fit was determined with the following cut-off criteria according to the structural equation modelling literature [ 68 , 69 ]: a significant χ 2 , comparative fit index (CFI > 0.9), chi-square fit statistics/degree of freedom (CMIN/DF < 5), goodness of fit index (GFI > 0.9), and root-mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (< 0.08).

The translation of BRS

The forward-translation procedures were done without any significant issues. In case of discrepancy or confusion, the matter would be resolved by committee, which as mentioned above consisting of the scale translators and research members. The backward-translated English version was compared with the original English version; no major linguistic or conceptual differences were detected. The results of the pilot testing for the pre-final version were acceptable, as the FVI value was 0.87 and the CVI value was 0.8. The final version of the Arabic translation was approved following the committee’s revision, refinement, and proofreading.

Baseline characteristics and descriptive data

A total of 1072 participants responded to the survey and are included in the analysis. The baseline characteristics of all participants are presented in Table 1 . The mean age of the participants was 29 ± 9, while the mean body mass index (BMI) was 23.99 ± 4.12. The majority (62%) of participants were female, while 611 participants (57%) were married. Almost half (49%) of the participants held a bachelor’s degree, and approximately 31% reported being unemployed at the time of the survey. The majority of the sample responded ‘no’ when asked about participating in physical activity (70%), smoking (82%), and having chronic disease (77.5%).

Baseline characteristics of participants ( N = 1072).

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation/frequency n and percentages (%).

BMI: body mass index.

BRS scores among participants

Of the 1072 participants, roughly one-third (326; 30%) were within the category of low resilience, while the majority of participants (746; 70%) reported moderate to high levels of resilience, as they had scores above the cut-off point (> 2.95). The average resilience level score was 3.43 with a standard deviation of 1.35.

Table 2 represents the frequencies and percentages of the BRS scores across the characteristics of participants. Of the total study population ( N = 1072), 426 of married participants and 347 of those holding a bachelor’s degree reported being resilient. A total of 227 participants who were not working, 537 participants who did not participate in physical activity, 607 participants who did not smoke, and 564 participants who did not have chronic diseases also reported being resilient.

BRS scores across the characteristics of participants ( N = 1072).

Data are presented as frequency n and percentages (%).

Percentages are of the total sample ( N = 1072).

Table 3 represents the descriptive characteristics of the BRS items with mean, standard deviation, skewness, kurtosis, item total correction, and alpha if the item is deleted. The total mean score for the Arabic version of BRS was 20.56 ± 8.08. The corrected item-total correlation for the Arabic version of BRS scale was above 0.30, which is acceptable for scale construction. The Cronbach’s alpha value for the Arabic version of BRS scale was 0.98, which is in the ‘most excellent’ range.

Descriptive statistics of the Arabic translated version of BRS.

Abbreviations. M : mean; SD : standard deviation; sk: skewness; ku: kurtosis; r it : corrected item total correlation; a iid : Cronbach’s alpha if item deleted.

Test–retest reliability was assessed for 118 subjects who were re-evaluated using the Arabic version of BRS 15 days after the first administration. The Arabic version of BRS pre-mean score was 3.44 ± 0.70, and the post-mean score was 3.38 ± 0.63. The ICC was calculated as 0.88 (95% CI: 0.82 to 0.92, p ≤ 0.0001).

Content validity and face validity

The content validity was assessed by 10 experts in the field, and the CVI was measured as 0.8. The face validity was determined by 32 subjects from the intended population, and the FVI was calculated as 0.87, which is in the acceptable range.

The Arabic version of BRS demonstrated a statistically significant correlation with the HADS for both depression ( r = −0.6) and anxiety ( r = −0.61), SWLS ( r = 0.44), PSS ( r = −0.53), and WHO-5 ( r = 0.58; Table 4 ).

Correlation between for the Arabic version of BRS and other well-established scales.

* p -value ≤ 0.05 is significant; r : Spearman’s correlation coefficient; CI: confidence intervals.

HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

SWLS: Satisfaction with Life Scale.

PSS: Perceived Stress Scale.

WHO-5: WHO-5 Well-Being Index Scale.

Factorial structure

The correlation matrix demonstrated a minimum value of 0.6 for all coefficients, suggesting high factorability. The factor analysis results demonstrated a KMO value of 0.84 and a significant Bartlett’s test of sphericity value ( p ≤ 0.0001), indicating subject adequacy for factor analysis. The EFA produced a two-factor model (eigenvalue = 4.44; 1.04), and the factor model constituted 91% of the total variance with all items having a factor loading of more than 0.88 in the model ( Figure 1 and Table 5 ). The results of the model showed a model fit (CMIN/DF = 9.105; GFI = 0.97; CFI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.09; Figure 2 ).

Scree plot showing the eigenvalue and factor loading.

CFA Path diagram showing the final model of the Arabic version of BRS.

The item loadings derived from exploratory factor analysis for the Arabic version of BRS.

Note . Loadings higher than 0.50 are displayed. M : mean; SD: standard deviation; R : reverse-coded items.

* p < 0.01 is significant.

This study aimed to translate the BRS into Arabic and measure its psychometric properties to validate it among the Saudi population. The scale was translated in accordance with international standards and was initially assessed by both experts in the field and a sample of the intended population. The translated scale had sufficient content (0.8) and face (0.87) validity scores. Our results also showed that the Arabic version of the BRS had adequate psychometric properties with excellent internal consistency, a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.98, and good test–retest reliability (ICC = 0.88). The scale was significantly correlated with the HADS, SWLS, PSS, and WHO-5 (all p -values ≤ 0.0001). Our results thus indicate that the Arabic version of the BRS can be used among the Saudi population as a valid resilience instrument that quantifies a person’s ability to bounce back from and cope with stressors, including those related to health.

Regarding reliability scores, the internal consistency of the scale was measured using the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, which is the extent to which all items in a scale measure the same concept or construct. Values over 0.7 are regarded as good, while values greater than 0.9 indicate high internal consistency between items [ 70 , 71 ]. The internal consistency for the translated BRS is consistent with that of the original English version of the BRS [ 14 ], as the alpha values ranged between 0.80 and 0.91 in all study samples. The Arabic translation yielded better values than those obtained from other translations of the BRS, such as the Chinese [ 39 ] ( α = 0.71), Dutch [ 38 ] ( α = 0.73), Portuguese (Brazil) [ 35 ] ( α = 0.76), Greek [ 42 ] ( α = 0.80), Spanish [ 32 ] ( α = 0.83), French [ 36 ] ( α = 0.84), Turkish [ 43 ] ( α = 0.86), Polish [ 37 ] ( α = 0.88), and German [ 30 ] ( α = 0.85) translations. It was not, however, significantly higher than the value obtained in the Malaysian BRS [ 33 ] ( α = 0.93). Our findings regarding the internal consistency of the Arabic BRS confirm that each item of the scale is interrelated with other items while measuring resilience among the Saudi population.

The ability of an instrument to consistently generate comparable findings over time is known as test–retest reliability [ 72 ]. To evaluate the degree of agreement between the repeated measures, the intraclass correlation coefficient was utilized. According to the literature, an ICC value of 0.70 or above indicates acceptable reliability, and values above 0.90 imply outstanding reliability [ 73 ]. Our study found that the test–retest scores demonstrated a good ICC value (ICC = 0.88), which was also supported by those translated versions published previously [ 14 , 31 ]. These findings demonstrate the strong reproducibility of the Arabic version of the BRS over time, potentially due to the scale items being short, simple, easy to understand, and straightforward.

The construct validity of the BRS was examined by conducting an EFA and a CFA. We first evaluated the data for sampling adequacy and appropriateness for factor analysis. Thereafter, we split the sample, and the EFA was conducted to determine the underlying structure of the items. A two-factor model (positive and negative items) was obtained, and by conducting a CFA, the two-factor model was further confirmed, and goodness of fit was ascertained. These results suggest that the Arabic version of the BRS scale measures a two-dimensional construct of resilience among the Saudi population. In contrast, the original English version of the BRS showed a mono-factorial structure [ 14 ]. Several other versions of the BRS have also shown that a one-factor structure is a good model fit [ 32 , 33 , 35 , 36 , 40 ]. Similar to our results, a two-factor model was confirmed in the Polish [ 37 ], Greek [ 42 ], and Chinese [ 39 ] versions. Those differences might be attributed to the model’s modification indices applied to the method effects to control for wording used during the analysis.

Using questionnaires measuring similar constructs of resilience, our evidence of convergent validity showed that the BRS scores are significantly and negatively related to HADS scores (depression: r = −0.6; anxiety: r = −0.61) and PSS scores ( r = −0.53) and positively related to SWLS scores ( r = 0.44) and WHO-5 scores ( r = 0.58). Those relationships assume that resilience levels could indicate an individual’s health status as related to anxiety, depression, satisfaction, stress, and well-being. In other words, the findings suggest that less resilient people most probably suffer from high levels of anxiety, depression, and stress. Resilience also appeared to increase subjective satisfaction among participants, a pattern also shown in relation to mental well-being. Despite methodological differences and sample variations, the abovementioned relationships have been introduced into the previous literature for several populations [ 74–79 ].

Regarding the level of resilience among our participants, moderate to high levels of resilience were prevalent among our study sample, indicating their ability to bounce back from stress. Female participants reported higher resilience levels compared to males. Such results are not dominant in previous research [ 80 , 81 ], as males usually demonstrated higher levels of resilience when compared to females. These results might differ due to the sociodemographic characteristics of the samples studied; in addition, our study included more female than male participants. Our results also showed that married participants were more resilient compared to other marital statuses. This could mean that support from an individual’s partner and family plays a major role in a person’s level of resilience [ 82 , 83 ].

The data revealed that a high percentage of resilient participants held at least a bachelor’s degree. Unlike our findings, previous studies have stated that an individual’s level of education does not impact their ability to adjust to and cope with adversity [ 84 , 85 ]. Furthermore, among all employment status categories included in our study, a high percentage of resilient participants were at least students. This could be supported by previous research, which has shown that unemployment contributes to lower levels of resilience [ 86 ]. In addition, many resilient participants did not have chronic diseases and did not smoke. These results are in line with previous studies [ 76 , 87–91 ], and these trends might be attributed to physiological changes in an individual’s body being associated with their level of resilience.

Surprisingly, more resilient participants indicated that they do not participate in physical activity compared to those who indicated that they are physically active, while research has shown the positive impact of physical activity and exercise on an individual’s level of resilience [ 92–94 ]. As our results revealed that the majority of participants (70%) reported moderate to high levels of resilience, based on previous research, it was reasonable to expect high levels of physical activity participation among our participants. That was not the case in the current study, as almost 50% of the sample reported moderate to high levels of resilience but with no physical activity participation. This may have resulted from not using a valid tool to measure physical activity among our sample. However, studying the relationship between sociodemographic characteristics and level of resilience is beyond the scope of this study.

Strengths and limitations

One potential strength of this study is that it is a population-based survey with a large sample size that includes a broad range of ages. Another strength is that this study used a standardized translation approach following rigorous steps of linguistic validation in addition to the in-depth statistical analysis employed to examine the reliability and validity of the scale. However, this study has possible limitations that should be acknowledged.

First, the cross-sectional design of the study, which used a self-reporting questionnaire, could initiate some forms of bias. Future studies should consider personal interviews or prospective longitudinal data collection methods to avoid such limitations. Second, although the study was population-based with a broad range of ages, we did not include individuals under 18 or over 70 years of age. The resilience scale could be used by both age categories since they may also experience stressful circumstances in their lives. Future research should validate the scale’s usage among those specific age groups. Third, although our study included a heterogenous sample (with and without health-related stressors) to validate the scale, participants were not stratified based on their health conditions. For the scale to be used accurately in clinical settings, reliability and validity evidence for a specific sample of a population is needed. Fourth, the majority of our sample was female. Our sample characteristics were, to some extent, similar to those studied by Smith et al. the original developer of the BRS [ 14 ], and other previous validations, such as the Greek translation [ 42 ]. Although sample comparability may imply that establishing the internal consistency of the Arabic BRS among the Saudi population could provide promising results similar to those previously published, future research should note socio-demographic, economic, and cultural differences while testing validation. Fifth, the scale was validated using a standardized Arabic language among the Saudi population; however, we did not conduct a cognitive debriefing including people from other Arab countries. Therefore, researchers should be cautious if extrapolating our findings to people in other Arab countries.

It was beyond the scope of the current study to examine the moderating role of participants’ socio-demographic and economic characteristics on the resilience instrument’s structure. Future studies are encouraged to conduct measurement invariance analyses of socio-demographic and economic characteristics on the instrument’s structure.

Practical implications

Few studies have examined the mental and physical health outcomes of resilience characteristics; however, the majority have focused on mental health outcomes [ 31 , 95 ]. Translating the BRS into Arabic and then validating the translated scale will provide the Arabic rehabilitation field and other health communities with a tool for research and clinical practice that specifically measures resilience in its original meaning: the ability to bounce back from stress. This is of high importance, as the scale can be used to identify those at a high risk of developing psychopathological compromises after experiencing stressful events and therefore protect against negative outcomes, either mental or physical. It will add to our fundamental knowledge of psychological rehabilitation and guide the development of strategic plans and psychological protective and rehabilitative intervention protocols for those in health-related stressful circumstances. Our scale’s validation was population-based; thus, it will also provide the scientific community with data on the psychometric properties of BRS scores to be used among Arabic-speaking individuals with or without health-related stressors.

As mentioned throughout the text, resilience is an essential attribute that individuals rely on to recover from and adapt to in the face of various stressors. In recent years, the concept of resilience has garnered significant attention not only from psychologists but also from educators and other professionals interested in understanding human behavior and responses to adversity. Assessing the psychometric properties of the Arabic version of the BRS will provide a valuable tool for monitoring progress and evaluating the effectiveness of interventions targeting resilience building in various fields such as therapy, counseling, and educational settings. Additionally, it may facilitate communication and collaboration between professionals such as psychologists, educators, and healthcare providers regarding strategies to promote resilience among the populations they serve.

Another benefit of having such a scale in Arabic is that it can enhance the understanding of mental health in Arab cultures, particularly in Saudi Arabia. Assessing resilience can help psychologists and educators gain a deeper understanding of various factors that contribute to mental health and well-being, ultimately assisting in the development of more effective treatment plans. Educators can use the resilience assessment to identify students who might struggle to cope with academic stressors or personal challenges [ 96 , 97 ]. This information can guide the development of educational programs that address emotional regulation, stress management, and life skills to foster greater resilience in students. It can guide curriculum design, as educators could use information about students’ resilience to develop curricula that foster key qualities associated with bouncing back from stressors, such as problem-solving, adaptability, and optimism. Furthermore, resilience assessment may enable personalized educational support based on specific needs and challenges. Both psychologists and educators can track individuals’ resilience over time to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions or educational programs.

The importance of studying the psychometric properties of resilience lies in the ability to better understand, measure, and promote this vital characteristic among individuals and communities. Accurate measurements of resilience help researchers evaluate the effectiveness of interventions designed to foster such qualities. Thus, facilitating focused research on resilience assessment can help researchers understand how different factors (e.g. personality traits) may impact an individual’s ability to cope with stressors, informing theory development and practical applications in the fields of health, psychology, and education, among others [ 98 ].

In summary, this study demonstrates that the Arabic version of the BRS is a valid and reliable means of assessing resilience, as originally defined as the ability to bounce back from stress [ 29 ], among a sample of the Saudi population. Since the scale was validated among a large heterogenous sample, it can reasonably be used for clinical and research purposes. The scale is short and easy to administer, and its questions are understandable and take only a few minutes to answer. The BRS will guide healthcare practitioners to screen patients for resilience levels so they can perform additional assessments and recommend appropriate interventions.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University for supporting this project through the Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2023R 286), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The authors would like to thank all participants for their time and cooperation while participation in this study.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2023R 286), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Authors’ contribution

All authors contributed substantially to the manuscript. BAB, MDA, and FK contributed to the conception and designing of the study. BAB, MDA, FK and MIA contributed to the data collection and FK contributed to the data analysis. BAB, MDA, FK and MIA contributed to the results’ interpretation of the analyzed data. BAB and MDA and MIA contributed to the writing of the original manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors critically read, revised, and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Authors note

The Arabic version of the BRS is available upon reasonable request from the principal investigator at as.ude.uak@haiattaabb .

Data availability statement

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Arabic language is widely used when conducting qualitative research in the healthcare field. 3 Not only is it spoken in 25 countries, but 30% of foreigners in western countries are Arabic-speaking migrants. 4 However, conducting qualitative research with Arabic participants requires translation for the results to be shared with a wider ...

Steps to Conducting Research. It's essential to note that there are different types of research: Exploratory research identifies a problem or question.; Constructive research examines hypotheses and offers solutions.; Empirical research tests the feasibility of a solution using data.; That being said, the research process may differ based on the purpose of the project.

Arab researchers encounter formidable obstacles when conducting and publishing their scientific work. We conducted semi-structured interviews with 17 Arab researchers from various Arab Middle East countries to gain a comprehensive understanding of the difficulties they face in research and publication.

Translations in context of "conducting research" in English-Arabic from Reverso Context: We make lots of different inferences or conclusions while conducting research.

"You are an Arabic speaker, well are you interested in undertaking research in Arabic with refugees?" This was the start of an exciting project for me. Over 10 years, I have been conducting research on vulnerabilities, planning, communities and social inequalities. I never embarked on research in my mother tongue and never with refugees.

Qualitative studies are a valuable approach to exploratory research. Frequently, researchers are required to collect data in languages other than English, which requires a translation process for ...

The main objectives of this study: Clarify the main barriers and challenges facing healthcare providers in Arabic countries. Make an association and relation between common barriers among healthcare providers and the MENA region. Provide information about strengths in Arabic countries in the research field.

However, language-embedded meaning can be lost in the translation process, and there is no consensus on the optimum timing of translation during the analysis process. Thus, the aim of this paper was to review how researchers conduct qualitative research with Arabic-speaking participants and the timing of data translation.

Meaning is expected to be detailed in the manuals of the policies and procedures for research ethics guidelines, such as the newly published "Saudi Procedures List of the System of Ethics of Research on Living Creatures" (2011), which is the only manual related to research ethics available in the region (This version is in Arabic only.

code of conduct n. (official rules) قوانين التعامل الرسمية. He was fired from the company for violating the code of conduct. conduct a campaign v expr. (promote [sth], [sb]) يقوم بحملة دعاية لـ. conduct a study v expr. (perform an investigation)

research translation in English - Arabic Reverso dictionary, see also 'research, reserve, rear, resemblance', examples, definition, conjugation. Translation Context Spell check Synonyms Conjugation. More. Collaborative Dictionary Documents Grammar Expressio. Reverso for Windows. ... It's well known these people conduct research into recent deaths.

conducting n. (leading an orchestra) قيادة فرقة موسيقية، قيادة أوركسترا. Conducting may look easy, but it requires a deep understanding of music. conducting n as adj. (musicians: leading) في القيادة الموسيقية. Music students can take a conducting course. conducting adj.

conduct. v. يَقُودُ. Additional comments: Helping millions of people and large organizations communicate more efficiently and precisely in all languages. conducting translation in English - Arabic Reverso dictionary, see also 'conductor, confusing, contain, condition', examples, definition, conjugation.

Register Connect. Display more examples. Suggest an example. Translations in context of "conducting" in English-Arabic from Reverso Context: conducting research, conducting business, currently conducting, after conducting, conducting investigations.

The Arabic language is widely used when conducting qualitative research in the healthcare field. 3 Not only is it spoken in 25 countries, but 30% of foreigners in western countries are Arabic-speaking migrants. 4 However, conducting qualitative research with Arabic participants requires translation for the results to be shared with a wider ...

https://orcid.org. Europe PMC. Menu. About. About Europe PMC; Preprints in Europe PMC

CONDUCT translate: سُلوك, يُجري, يَقوْد (الفرقة الموسيقيّة). Learn more in the Cambridge English-Arabic Dictionary.

Translations Definition Synonyms Conjugation Pronunciation Examples Translator Phrasebook open_in_new. ... English Arabic Contextual examples of "conduct" in Arabic . ... and newly synthesized and characterized compounds are reported weekly in prominent research journals. more_vert.

Translating the BRS into Arabic and then validating the translated scale will provide the Arabic rehabilitation field and other health communities with a tool for research and clinical practice that specifically measures resilience in its original meaning: the ability to bounce back from stress.

Display more examples. Suggest an example. Translations in context of "conduct" in English-Arabic from Reverso Context: rule of conduct, conduct oneself, conduct a funeral, code of conduct, codes of conduct.

New York CNN —. OpenAI on Monday announced its latest artificial intelligence large language model that it says will be easier and more intuitive to use. The new model, called GPT-4o, is an ...