You are using an outdated browser and it's not supported. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

- LOGIN FOR PROGRAM PARTICIPANTS

- PROGRAM SUPPORT

Close Reading: Learning about the Declaration of Independence

Description.

There may be cases when our downloadable resources contain hyperlinks to other websites. These hyperlinks lead to websites published or operated by third parties. UnboundEd and EngageNY are not responsible for the content, availability, or privacy policies of these websites.

- Grade 4 Module 3B, Unit 1, Lesson 9

Bilingual Language Progressions

These resources, developed by the New York State Education Department, provide standard-level scaffolding suggestions for English Language Learners (ELLs) to help them meet grade-level demands. Each resource contains scaffolds at multiple levels of language acquisition and describes the linguistic demands of the standards to help ELA teachers as well as ESL/bilingual teachers scaffold content for their English learning students.

- CCSS Standard:

- Kathy Wilmore

- Thomas Jefferson and the Declaration of Independence

Related Guides and Multimedia

Our professional learning resources include teaching guides, videos, and podcasts that build educators' knowledge of content related to the standards and their application in the classroom.

There are no related guides or videos. To see all our guides, please visit the Enhance Instruction section here .

MA in American History : Apply now and enroll in graduate courses with top historians this summer!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

History Resources

The Declaration of Independence

By tim bailey, view the declaration in the gilder lehrman collection by clicking here and here . for additional primary resources click here and here ., unit objective.

This unit is part of Gilder Lehrman’s series of Common Core State Standards–based teaching resources. These units were written to enable students to understand, summarize, and analyze original texts of historical significance. Students will demonstrate this knowledge by writing summaries of selections from the original document and, by the end of the unit, articulating their understanding of the complete document by answering questions in an argumentative writing style to fulfill the Common Core State Standards. Through this step-by-step process, students will acquire the skills to analyze any primary or secondary source material.

While the unit is intended to flow over a five-day period, it is possible to present and complete the material within a shorter time frame. For example, the first two days can be used to ensure an understanding of the process with all of the activity completed in class. The teacher can then assign lessons three and four as homework. The argumentative essay is then written in class on day three.

Students will be asked to "read like a detective" and gain a clear understanding of the Declaration of Independence. Through reading and analyzing the original text, the students will know what is explicitly stated, draw logical inferences, and demonstrate these skills by writing a succinct summary and then restating that summary in the student’s own words. In the first lesson this will be facilitated by the teacher and done as a whole-class lesson.

Introduction

Tell the students that they will be learning what Thomas Jefferson wrote in 1776 that served to announce the creation of a new nation by reading and understanding Jefferson’s own words. Resist the temptation to put the Declaration into too much context. Remember, we are trying to let the students discover what Jefferson and the Continental Congress had to say and then develop ideas based solely on the original text.

- The Declaration of Independence, abridged (PDF)

- Teacher Resource: Complete text of the Declaration of Independence (PDF). This transcript of the Declaration of Independence is from the National Archives online resource The Charters of Freedom .

- Summary Organizer #1 (PDF)

- All students are given an abridged copy of the Declaration of Independence and are asked to read it silently to themselves.

- The teacher then "share reads" the text with the students. This is done by having the students follow along silently while the teacher begins reading aloud. The teacher models prosody, inflection, and punctuation. The teacher then asks the class to join in with the reading after a few sentences while the teacher continues to read along with the students, still serving as the model for the class. This technique will support struggling readers as well as English Language Learners (ELL).

- The teacher explains that the students will be analyzing the first part of the text today and that they will be learning how to do in-depth analysis for themselves. All students are given a copy of Summary Organizer #1. This contains the first selection from the Declaration of Independence.

- The teacher puts a copy of Summary Organizer #1 on display in a format large enough for all of the class to see (an overhead projector, Elmo projector, or similar device). Explain that today the whole class will be going through this process together.

- Explain that the objective is to select "Key Words" from the first section and then use those words to create a summary sentence that demonstrates an understanding of what Jefferson was saying in the first paragraph.

- Guidelines for selecting the Key Words: Key Words are very important contributors to understanding the text. Without them the selection would not make sense. These words are usually nouns or verbs. Don’t pick "connector" words (are, is, the, and, so, etc.). The number of Key Words depends on the length of the original selection. This selection is 181 words so we can pick ten Key Words. The other Key Words rule is that we cannot pick words if we don’t know what they mean.

- Students will now select ten words from the text that they believe are Key Words and write them in the box to the right of the text on their organizers.

- The teacher surveys the class to find out what the most popular choices were. The teacher can either tally this or just survey by a show of hands. Using this vote and some discussion the class should, with guidance from the teacher, decide on ten Key Words. For example, let’s say that the class decides on the following words: necessary, dissolve, political bonds (yes, technically these are two words, but you can allow such things if it makes sense to do so; just don’t let whole phrases get by), declare, separation, self-evident, created equal, liberty, abolish, and government. Now, no matter which words the students had previously selected, have them write the words agreed upon by the class or chosen by you into the Key Words box in their organizers.

- The teacher now explains that, using these Key Words, the class will write a sentence that restates or summarizes what was stated in the Declaration. This should be a whole-class discussion-and-negotiation process. For example, "It is necessary for us to dissolve our political bonds and declare a separation; it is self-evident that we are created equal and should have liberty, so we need to abolish our current government." You might find that the class decides they don’t need the some of the words to make it even more streamlined. This is part of the negotiation process. The final negotiated sentence is copied into the organizer in the third section under the original text and Key Words sections.

- The teacher explains that students will now be putting their summary sentence into their own words, not having to use Jefferson’s words. Again, this is a class discussion-and-negotiation process. For example, "We need to get rid of our old government so we can be free."

- Wrap up: Discuss vocabulary that the students found confusing or difficult. If you choose, you could have students use the back of their organizers to make a note of these words and their meanings.

Students will be asked to "read like a detective" and gain a clear understanding of what Thomas Jefferson was writing about in the Declaration of Independence. Through reading and analyzing the original text, the students will know what is explicitly stated, draw logical inferences, and demonstrate these skills by writing a succinct summary and then restating that summary in the student’s own words. In the second lesson the students will work with partners and in small groups.

Tell the students that they will be further exploring the meaning of the Declaration of Independence by reading and understanding Jefferson’s text and then being able to tell, in their own words, what he said. Today they will be working with partners and in small groups.

- Summary Organizer #2 (PDF)

- All students are given the abridged copy of the Declaration of Independence and are asked to read it silently to themselves.

- The students and teacher discuss what they did yesterday and what they decided was the meaning of the first selection.

- The teacher then "share reads" the second selection with the students. This is done by having the students follow along silently while the teacher begins reading aloud. The teacher models prosody, inflection, and punctuation. The teacher then asks the class to join in with the reading after a couple of sentences while the teacher continues to read along with the students, still serving as the model for the class. This technique will support struggling readers as well as English Language Learners (ELL).

- The teacher explains that the class will be analyzing the second selection from the Declaration of Independence today. All students are given a copy of Summary Organizer #2. This contains the second selection from the Declaration.

- The teacher puts a copy of Summary Organizer #2 on display in a format large enough for all of the class to see (an overhead projector, Elmo projector, or similar device). Explain that today they will be going through the same process as yesterday but with partners and in small groups.

- Explain that the objective is still to select "Key Words" from the second selection and then use those words to create a summary sentence that demonstrates an understanding of what Jefferson was saying in that selection.

- Guidelines for selecting the Key Words: The guidelines for selecting Key Words are the same as they were yesterday. However, because this paragraph is shorter than the last one at 148 words, they can pick only seven or eight Key Words.

- Pair the students up and have them negotiate which Key Words to select. After they have decided on their words both students will write them in the Key Words box of their organizers.

- The teacher now puts two pairs together. These two pairs go through the same negotiation-and-discussion process to come up with their Key Words. Be strategic in how you make your groups to ensure the most participation by all group members.

- The teacher now explains that by using these Key Words the group will build a sentence that restates or summarizes what Thomas Jefferson was saying. This is done by the group negotiating with its members on how best to build that sentence. Try to make sure that everyone is contributing to the process. It is very easy for one student to take control of the entire process and for the other students to let them do so. All of the students should write their negotiated sentence into their organizers.

- The teacher asks for the groups to share out the summary sentences they have created. This should start a teacher-led discussion that points out the qualities of the various attempts. How successful were the groups at understanding the Declaration and were they careful to only use Jefferson’s Key Words in doing so?

- The teacher explains that the group will now be putting their summary sentence into their own words, not having to use Jefferson’s words. Again, this is a group discussion-and-negotiation process. After they have decided on a sentence it should be written into their organizers. Again, the teacher should have the groups share out and discuss the clarity and quality of the groups’ attempts.

Students will be asked to "read like a detective" and gain a clear understanding of the meaning of the Declaration of Indpendence. Through reading and analyzing the original text, the students will know what is explicitly stated, draw logical inferences, and demonstrate these skills by writing a succinct summary and then restating that summary in the student’s own words. In this lesson the students will be working individually.

Tell the students that they will be further exploring what Thomas Jefferson was saying in the third selection from the Declaration of Independence by reading and understanding Jefferson’s words and then being able to tell, in their own words, what he said. Today they will be working by themselves on their summaries.

- Summary Organizer #3 (PDF)

- The students and teacher discuss what they did yesterday and what they decided was the meaning of the first two selections.

- The teacher then "share reads" the third selection with the students. This is done by having the students follow along silently while the teacher begins reading aloud. The teacher models prosody, inflection, and punctuation. The teacher then asks the class to join in with the reading after a couple of sentences while the teacher continues to read along with the students, still serving as the model for the class. This technique will support struggling readers as well as English Language Learners (ELL).

- The teacher explains that the class will be analyzing the third selection from the Declaration of Independence today. All students are given a copy of Summary Organizer #3. This contains the third selection from the Declaration.

- The teacher puts a copy of Summary Organizer #3 on display in a format large enough for all of the class to see (an overhead projector, Elmo projector, or similar device). Explain that today they will be going through the same process as yesterday, but they will be working by themselves.

- Explain that the objective is still to select "Key Words" from the third paragraph and then use those words to create a summary sentence that demonstrates an understanding of what Jefferson was saying in that selection.

- Guidelines for selecting the Key Words: The guidelines for selecting Key Words are the same as they were yesterday. However, because this paragraph is longer (208 words) they can pick ten Key Words.

- Have the students decide which Key Words to select. After they have chosen their words they will write them in the Key Words box of their organizers.

- The teacher explains that, using these Key Words, each student will build a sentence that restates or summarizes what Jefferson was saying. They should write their summary sentences into their organizers.

- The teacher explains that they will be putting their summary sentence into their own words, not having to use Jefferson’s words. This should be added to their organizers.

- The teacher asks for students to share out the summary sentences they have created. This should start a teacher-led discussion that points out the qualities of the various attempts. How successful were the students at understanding what Jefferson was writing about?

Tell the students that they will be further exploring what Thomas Jefferson was saying in the fourth selection from the Declaration of Independence by reading and understanding Jefferson’s words and then being able to tell, in their own words, what he said. Today they will be working by themselves on their summaries.

- Summary Organizer #4 (PDF)

- The students and teacher discuss what they did yesterday and what they decided was the meaning of the first three selections.

- The teacher then "share reads" the fourth selection with the students. This is done by having the students follow along silently while the teacher begins reading aloud. The teacher models prosody, inflection, and punctuation. The teacher then asks the class to join in with the reading after a couple of sentences while the teacher continues to read along with the students, still serving as the model for the class. This technique will support struggling readers as well as English Language Learners (ELL).

- The teacher explains that the class will be analyzing the fourth selection from the Declaration of Independence today. All students are given a copy of Summary Organizer #4. This contains the fourth selection from the Declaration.

- The teacher puts a copy of Summary Organizer #4 on display in a format large enough for all of the class to see (an overhead projector, Elmo projector, or similar device). Explain that today they will be going through the same process as yesterday, but they will be working by themselves.

- Explain that the objective is still to select "Key Words" from the fourth paragraph and then use those words to create a summary sentence that demonstrates an understanding of what Jefferson was saying in that selection.

- Guidelines for selecting the Key Words: The guidelines for selecting Key Words are the same as they were yesterday. Because this paragraph is the longest (more than 219 words) it will be challenging for them to select only ten Key Words. However, the purpose of this exercise is for the students to get at the most important content of the selection.

- The teacher explains that now they will be putting their summary sentence into their own words, not having to use Jefferson’s words. This should be added to their organizers.

This lesson has two objectives. First, the students will synthesize the work of the last four days and demonstrate that they understand what Jefferson was saying in the Declaration of Independence. Second, the teacher will ask questions of the students that require them to make inferences from the text and also require them to support their conclusions in a short essay with explicit information from the text.

Tell the students that they will be reviewing what Thomas Jefferson was saying in the Declaration of Independence. Second, you will be asking them to write a short argumentative essay about the Declaration; explain that their conclusions must be backed up by evidence taken directly from the text.

- All students are given the abridged copy of the Declaration of Independence and then are asked to read it silently to themselves.

- The teacher asks the students for their best personal summary of selection one. This is done as a negotiation or discussion. The teacher may write this short sentence on the overhead or similar device. The same procedure is used for selections two, three, and four. When they are finished the class should have a summary, either written or oral, of the Declaration in only a few sentences. This should give the students a way to state what the general purpose or purposes of the document were.

- The teacher can have the students write a short essay now addressing one of the following prompts or do a short lesson on constructing an argumentative essay. If the latter is the case, save the essay writing until the next class period or assign it for homework. Remind the students that any arguments they make must be backed up with words taken directly from the Declaration of Independence. The first prompt is designed to be the easiest.

- What are the key arguments that Thomas Jefferson makes for the colonies’ separation from Great Britain?

- Can the Declaration of Independence be considered a declaration of war? Using evidence from the text argue whether this is or is not true.

- Thomas Jefferson defines what the role of government should and should not be. How does he make these arguments?

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter.

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

EL Education Curriculum

You are here.

- ELA G4:M3:U2:L5

Close Read: Excerpt of the Declaration of Independence, Part I

In this lesson, daily learning targets, ongoing assessment.

- Technology and Multimedia

Supporting English Language Learners

Universal design for learning, closing & assessments, you are here:.

- ELA Grade 4

- ELA G4:M3:U2

Like what you see?

Order printed materials, teacher guides and more.

How to order

Help us improve!

Tell us how the curriculum is working in your classroom and send us corrections or suggestions for improving it.

Leave feedback

These are the CCS Standards addressed in this lesson:

- RL.4.1: Refer to details and examples in a text when explaining what the text says explicitly and when drawing inferences from the text.

- RI.4.1: Refer to details and examples in a text when explaining what the text says explicitly and when drawing inferences from the text.

- RI.4.4: Determine the meaning of general academic and domain-specific words or phrases in a text relevant to a grade 4 topic or subject area .

- SL.4.1: Engage effectively in a range of collaborative discussions (one-on-one, in groups, and teacher-led) with diverse partners on grade 4 topics and texts , building on others' ideas and expressing their own clearly.

- SL.4.6: Differentiate between contexts that call for formal English (e.g., presenting ideas) and situations where informal discourse is appropriate (e.g., small-group discussion); use formal English when appropriate to task and situation.

- L.4.4: Determine or clarify the meaning of unknown and multiple-meaning words and phrases based on grade 4 reading and content, choosing flexibly from a range of strategies.

- I can closely read an excerpt of the Declaration of Independence to restate it in my own words. (RL.4.1, RL.4.3, RI.4.1, RI.4.4, SL.4.1a, L.4.4)

- I can make connections between an excerpt of the Declaration of Independence and the opinions of characters in Divided Loyalties. (RI.4.1, RL.4.1)

- I can follow discussion norms to participate in a productive discussion about opinions of the characters in Divided Loyalties. (SL.4.1)

- Close Read Note-catcher: Excerpt of the Declaration of Independence, Part I (RL.4.1, RL.4.3, RI.4.1, RI.4.4, SL.4.1a, L.4.4)

- Discussion Notes (SL.4.1c, SL.4.1d)

- Strategically pair students for close reading, with at least one strong reader per pair.

- Strategically group students heterogeneously for discussions, ensuring that the pairs from close reading are separated. There should be four or five students in each group. Try to get an even number of groups so that the groups can be paired off to observe each other during the discussion and provide feedback.

- Review the Fishbowl protocol (see Classroom Protocols).

- Post: Learning targets; Infer the Topic Resources: 4 from Unit 1, Lesson 1; and applicable anchor charts (see Materials list).

Tech and Multimedia

- Continue to use the technology tools recommended throughout Modules 1-2 to create anchor charts to share with families, to record students as they participate in discussions and protocols to review with students later and to share with families, and for students to listen to and annotate text, record ideas on note-catchers, and word-process writing.

Supports guided in part by CA ELD Standards 4.I.B.6, 4.I.B.7, 4.I.B.8, 4.I.A.1, 4.I.A.3, 4.I.A.4, 4.I.C.12, 4.II.B.5, 4.II.B.6, 4.II.B.7

Important points in the lesson itself

- The basic design of this lesson supports ELLs by guiding them in a close read of an excerpt of the Declaration of Independence with a specific focus on determining the meaning of unfamiliar words and phrases and restating the text in their own words. The same routine followed for each of the three sections of this text during the close read supports students in each of these goals.

- ELLs may find the combination of the linguistic demands of the excerpt of the Declaration of Independence and the cognitive demand of determining a character's opinion of this text overwhelming. Additionally, they may find it challenging to engage in a text-based discussion with these combined linguistic and cognitive demands without much time to prepare. Consider providing additional time for students to orally process their thoughts with a partner before the text-based discussion. See levels of support, below, and the Meeting Students' Needs column for additional suggestions.

- In Work Time A of this lesson, ELLs may participate in an optional Language Dive that guides them through the meaning of an excerpt from the Excerpt of the Declaration of Independence, Part I. The focus of this Language Dive is on the subordinating conjunction whenever, as well as on providing an opportunity for students to restate complex language structures in their own words. Students then apply their understanding of the meaning and structure of this excerpt when participating in a text-based discussion later in this lesson and when reading and restating excerpts of the Declaration of Independence throughout the unit. Preview the Language Dive Guide and consider how to invite conversation among students to address the language goals suggested under each sentence strip chunk (see supporting Materials). Select from the questions and goals provided to best meet your students' needs. See the Tools page e for additional information regarding a consistent Language Dive routine.

Levels of support

For lighter support:

- During the text-based discussion in Work Time B, encourage students to use Goals 1 and 2 Conversation Cues with other students to extend and deepen conversations, think with others, and enhance language development. (Example: "Can you give an example?")

For heavier support:

- Consider providing students with sentence starters during Work Time B to support them in the text-based discussion. Allow time for them to orally practice with a partner before doing so with the group. For example, "I agree, and would like to add that ____." "One example that demonstrates this opinion is _____."

- Multiple Means of Representation (MMR): This lesson offers a variety of visual anchors to cue students' thinking. For those who may need additional support, consider creating additional or individual anchor charts for reference. Additionally, chart student responses during whole class discussions to aid with comprehension. Some students may require additional scaffolding in visual representation (e.g., the use of graphic organizers, charts, highlights, or different colors). This prompts them to visually categorize information into more manageable chunks and reinforce relationships among multiple pieces of information.

- Multiple Means of Action and Expression (MMAE): During independent writing, support a range of fine motor abilities and writing needs by offering students options for writing utensils. Alternatively, consider supporting students' expressive skills by offering partial dictation of student responses. Varying tools for construction and composition supports students' ability to express knowledge without barriers to communicating their thinking.

- Multiple Means of Engagement (MME): Provide support for students who may need additional guidance in peer interactions and collaboration. Continue to offer prompts or sentence frames that support students in asking for help or clarification from classmates. To support students who may need help in sustaining effort and/or attention, provide opportunities for restating the goal. In doing so, students maintain focus to complete the activity.

Key: Lesson-Specific Vocabulary (L); Text-Specific Vocabulary (T); Vocabulary Used in Writing (W)

- restate, opinions, productive (L)

- truths, self-evident, rights, secure, governments, just, consent, governed, destructive, alter, abolish (T)

- Close Readers Do These Things anchor chart (begun in Module 1)

- Academic Word Wall (begun in Module 1; added to during the Opening)

- Divided Loyalties (from Lesson 1; one per student)

- Infer the Topic Resources: 4 (from Unit 1, Lesson 1; one to display)

- Excerpt of the Declaration of Independence, Part I (one per student and one to display)

- Working to Become Effective Learners anchor chart (begun in Module 1)

- Close Reading Guide: An Excerpt of the Declaration of Independence, Part I (for teacher reference)

- Close Reading Note-catcher: An Excerpt of the Declaration of Independence, Part I (one per student and one to display)

- Close Reading Note-catcher: An Excerpt of the Declaration of Independence, Part I (example, for teacher reference)

- Language Dive Guide: Excerpt of the Declaration of Independence, Part I (optional; for ELLs; for teacher reference)

- Questions We Can Ask during a Language Dive anchor chart (begun in Unit 1)

- Language Dive Chunk Chart: Excerpt of the Declaration of Independence, Part I (optional; for ELLs; for teacher reference)

- Language Dive Sentence Strip Chunks: Excerpt of the Declaration of Independence, Part I (optional; for ELLs; one to display)

- Language Dive Note-catcher: Excerpt of the Declaration of Independence, Part I (optional; for ELLs; one per student and one to display)

- Discussion Norms anchor chart (begun in Module 1)

- Discussion Notes (one per student)

- Sticky notes (two colors; one of each per student)

- Working to Become Ethical People anchor chart (begun in Module 1)

- T-chart (one per discussion group)

- Character Analysis Paragraph: Act I, Scene 3--Robert (example, for teacher reference)

Each unit in the 3-5 Language Arts Curriculum has two standards-based assessments built in, one mid-unit assessment and one end of unit assessment.

Copyright © 2013-2024 by EL Education, New York, NY.

Get updates about our new K-5 curriculum as new materials and tools debut.

Help us improve our curriculum..

Tell us what’s going well, share your concerns and feedback.

Terms of use . To learn more about EL Education, visit eleducation.org

- Number of visits 487

- Number of saves 3

ELA Grade 11 Exploring Independence

- Report this resource

Description

No reviewers yet.

Add a Reviewer.

Maryland College and Career Ready English Language Arts Standards

Learning Domain: Language

Standard: Demonstrate command of the conventions of standard English grammar and usage when writing or speaking.

Degree of Alignment: Not Rated (0 users)

Standard: Demonstrate command of the conventions of standard English capitalization, punctuation, and spelling when writing.

Standard: Determine or clarify the meaning of unknown and multiple-meaning words and phrases based on grades 11-12 reading and content, choosing flexibly from a range of strategies.

Standard: Demonstrate understanding of figurative language, word relationships, and nuances in word meanings.

Standard: Acquire and use accurately general academic and domain-specific words and phrases, sufficient for reading, writing, speaking, and listening at the college and career readiness level; demonstrate independence in gathering vocabulary knowledge when considering a word or phrase important to comprehension or expression.

Learning Domain: Reading Literature

Standard: Cite strong and thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text, including determining where the text leaves matters uncertain.

Standard: Determine two or more themes or central ideas of a text and analyze their development over the course of the text, including how they interact and build on one another to produce a complex account; provide an objective summary of the text.

Learning Domain: Writing

Standard: Write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts, using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence.

Standard: Write routinely over extended time frames (time for research, reflection, and revision) and shorter time frames (a single sitting or a day or two) for a range of tasks, purposes, and audiences.

Standard: Draw evidence form literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research.

Standard: Apply grades 11-12 Reading standards to literary nonfiction (e.g., "Delineate and evaluate the reasoning in seminal U.S. texts, including the application of constitutional principles and use of legal reasoning [e.g., in U.S. Supreme Court Case majority opinions and dissents) and the premises, purposes, and arguments in works of public advocacy (e.g., The Federalist, presidential addresses]").

Evaluations

No evaluations yet.

Review Criteria

Select one or multiple and then click Browse

What So Proudly We Hail | Blog

Close Reading Activity: The Declaration of Independence

On July 4, 1776, two days after it adopted the Lee Resolution that declared the united colonies’ independence from Great Britain, the Continental Congress approved the Declaration of Independence , drafted by Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826), which explains that decision by “declar[ing] the causes which impel them to the separation.”

Engage your students in a close reading of the Declaration of Independence with the help of these discussion questions from our Independence Day ebook :

The opening paragraphs of the Declaration provide the first and most authoritative statement of what we might call “the American creed.” For in separating from Great Britain, the united colonies ground their claim to political independence in a teaching about individual human rights—to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness—to which rightful freedoms all human beings are said to be equally entitled.

In articulating the four self-evident truths (natural equality, inalienable individual rights, government founded on the consent of the governed, and the people’s right of revolution) and compiling the list of the king’s abuses, Jefferson claims to have done nothing more than “place before mankind the common sense of the subject.” “It was,” he explained years later, “intended to be an expression of the American mind.” Even so, this birth announcement of the American Republic reveals that it is the first nation anywhere to be founded not on ties of blood, soil, or lineage but on a set of philosophical principles for which the document—and the nation—are justly celebrated.

Careful study of the text will attend to both the universal principles and the particular grievances, as well as to the question of the relation between them. What, according to the Declaration, makes the American colonists a distinct “people,” entitled to a “separate and equal station” among the peoples of the world? What is meant by the Laws of Nature and Nature’s God, and how are these related to our “peoplehood”? What is a “right,” and where do individual rights come from? What is a “self-evident” truth, and in what self-evidently true sense can we say that “all men are created equal”? How does the Declaration understand the relation between the individual and the collective? Between our rights and our responsibilities (or duties)? Do we Americans today still hold these truths (or any truths) to be self-evident?

Review carefully the list of grievances. Which ones strike you as most egregious? To what do they all add up? Why does the document emphasize the deeds of the king, downplaying the complicit role of Parliament? What is the relation between these grievances and the philosophical principles stated earlier? Are you persuaded that revolution was in fact justified? Imagining yourself in Philadelphia in July 1776, would you have pledged your Life, Fortune, and sacred Honor to support this Declaration? Would you—and in the name of what?—make such a pledge today to support the American Republic, should comparable support be needed?

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

declaration of independence reading assignment

All Formats

Resource types, all resource types.

- Rating Count

- Price (Ascending)

- Price (Descending)

- Most Recent

Declaration of independence reading assignment

Declaration of Independence Reading Assignment - Signers of Freedom

The Declaration of Independence : Close Reading and Analysis Assignment

- Word Document File

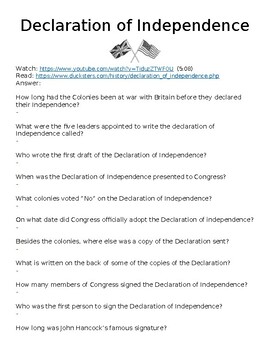

Declaration of independence "Watch, Read & Answer" Online Assignment (WORD)

Declaration of independence "Watch, Read & Answer" Online Assignment (PDF)

Declaration of Independence Opener, Close Read , and Wiki Assignment

(Portuguese) Declaration of Independence "Watch, Read & Answer" Assignment

- Google Docs™

Declaration of Independence "Watch, Read & Answer" Online Assignment

Declaration of Independence - Close Read , Group Analysis, Optional Deep Analysis

Info Reading Text - Pre-Revolution America Bundle 10 Articles (No Prep Sub Plan)

Declaration of Independence Reading Comprehension

- Google Slides™

The Declaration of Independence - Online Reading , Questions, Beyond the Document

- Internet Activities

Close Reading Lesson Plan: Declaration of Independence

Declaration of Independence Reading Activities

- Google Apps™

Arguments of the Declaration of Independence (SSUSH4a)

Declaration of Rights of Man Assignment French Revolution

Declaration of Independence Article & Questions (PDF)

Declaration of Independence Article & Questions (WORD)

American Revolution "Watch, Read & Answer" Online Assignment Bundle (GOOGLE)

2.2 - Declaring Independence Guided Reading Questions - SSUSH3

Declaration of Independence Annotated Reading

American Revolution "Watch, Read & Answer" Online Assignment Bundle (WORD)

American Revolution "Watch, Read & Answer" Online Assignment Bundle (PDF)

- We're hiring

- Help & FAQ

- Privacy policy

- Student privacy

- Terms of service

- Tell us what you think

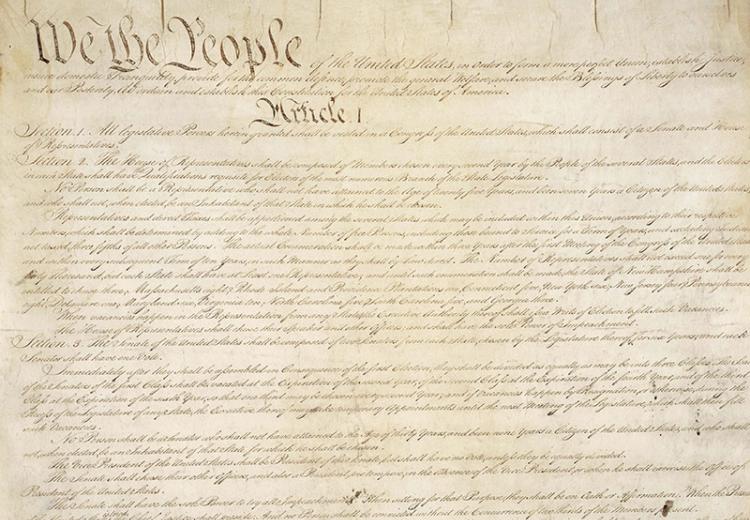

America's Founding Documents

Declaration of Independence: A Transcription

Note: The following text is a transcription of the Stone Engraving of the parchment Declaration of Independence (the document on display in the Rotunda at the National Archives Museum .) The spelling and punctuation reflects the original.

In Congress, July 4, 1776

The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America, When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.--That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, --That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.--Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.

He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.

He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them.

He has refused to pass other Laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of Representation in the Legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only.

He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures.

He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people.

He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected; whereby the Legislative powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within.

He has endeavoured to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands.

He has obstructed the Administration of Justice, by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary powers.

He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone, for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries.

He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harrass our people, and eat out their substance.

He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures.

He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil power.

He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation:

For Quartering large bodies of armed troops among us:

For protecting them, by a mock Trial, from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States:

For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world:

For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent:

For depriving us in many cases, of the benefits of Trial by Jury:

For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences

For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies:

For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws, and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments:

For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever.

He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us.

He has plundered our seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people.

He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty & perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation.

He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands.

He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.

In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.

Nor have We been wanting in attentions to our Brittish brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. We have appealed to their native justice and magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the ties of our common kindred to disavow these usurpations, which, would inevitably interrupt our connections and correspondence. They too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends.

We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.

Button Gwinnett

George Walton

North Carolina

William Hooper

Joseph Hewes

South Carolina

Edward Rutledge

Thomas Heyward, Jr.

Thomas Lynch, Jr.

Arthur Middleton

Massachusetts

John Hancock

Samuel Chase

William Paca

Thomas Stone

Charles Carroll of Carrollton

George Wythe

Richard Henry Lee

Thomas Jefferson

Benjamin Harrison

Thomas Nelson, Jr.

Francis Lightfoot Lee

Carter Braxton

Pennsylvania

Robert Morris

Benjamin Rush

Benjamin Franklin

John Morton

George Clymer

James Smith

George Taylor

James Wilson

George Ross

Caesar Rodney

George Read

Thomas McKean

William Floyd

Philip Livingston

Francis Lewis

Lewis Morris

Richard Stockton

John Witherspoon

Francis Hopkinson

Abraham Clark

New Hampshire

Josiah Bartlett

William Whipple

Samuel Adams

Robert Treat Paine

Elbridge Gerry

Rhode Island

Stephen Hopkins

William Ellery

Connecticut

Roger Sherman

Samuel Huntington

William Williams

Oliver Wolcott

Matthew Thornton

Back to Main Declaration Page

- Lesson Plans

- Teacher's Guides

- Media Resources

The Preamble to the Constitution: A Close Reading Lesson

The first page of the United States Constitution, opening with the Preamble.

National Archives

"[T]he preamble of a statute is a key to open the mind of the makers, as to the mischiefs, which are to be remedied, and the objects, which are to be accomplished by the provisions of the statute." — Justice Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution

The Preamble is the introduction to the United States Constitution, and it serves two central purposes. First, it states the source from which the Constitution derives its authority: the sovereign people of the United States. Second, it sets forth the ends that the Constitution and the government that it establishes are meant to serve.

Gouverneur Morris, the man the Constitutional Convention entrusted with drafting the final version of the document, put into memorable language the principles of government negotiated and formulated at the Convention.

As Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story points out in the passage quoted above, the Preamble captures some of the hopes and fears of the framers for the American republic. By reading their words closely and comparing them with those of the Articles of Confederation, students can in turn access “the mind of the makers” as to “mischiefs” to be “remedied” and “objects” to be accomplished.

In this lesson, students will practice close reading of the Preamble and of related historic documents, illuminating the ideas that the framers of the Constitution set forth about the foundation and the aims of government.

Guiding Questions

How does the language of the Preamble to the U.S. Constitution reflect historical circumstances and ideas about government?

To what extent is the U.S. Constitution a finished document?

Learning Objectives

Compare the Preamble to the U.S. Constitution with the statement of purposes included in the Articles of Confederation.

Explain the source of authority and the goals of the U.S. Constitution as identified in the Preamble.

Evaluate the fundamental values and principles expressed in the Preamble to the U.S. Constitution.

Lesson Plan Details

The Articles of Confederation was established in 1781 as the nation’s “first constitution.” Each state governed itself through elected representatives, and the state representatives in turn elected a central government. But the national government was so feeble and its powers so limited that this system proved unworkable. Congress could not impose taxes to cover national expenses, which meant the Confederation was ineffectual. And because all 13 colonies had to ratify amendments, one state’s refusal prevented any reform. By 1786 many far-sighted American leaders saw the need for a more powerful central authority; a convention was called to meet in Philadelphia in May 1787.

The Constitutional Convention met for four months. Among the chief points at issue were how much power to allow the central government and then, how to balance and check that power to prevent government abuse.

As debate at the Philadelphia Convention drew to a close, Gouverneur Morris was assigned to the Committee of Style and given the task of wording the Constitution by the committee’s members. Through thoughtful word choice, Morris attempted to put the fundamental principles agreed on by the framers into memorable language.

By looking carefully at the words of the Preamble, comparing it with the similar passages in the opening of the Articles of Confederation, and relating them to historical circumstances as well as widely shared political principles such as those found in the Declaration of Independence, students can see how the Preamble reflects the hope and fears of the Framers.

For background information about the history and interpretation of the Constitution, see the following resources:

- A basic and conveniently organized introduction to the historical context is “ To Form a More Perfect Union ,” available in Documents from the Continental Congress and the Constitutional Convention, 1774–1789 from the Library of Congress .

- Another historical summary is " Constitution of the United States—A History ," available in America's Founding Documents from the National Archives .

- The Interactive Constitution , a digital resource that incorporates commentary from constitutional scholars, is available from the National Constitution Center .

- The American Constitution: A Documentary Record , available via The Avalon Project at the Yale Law School , offers an extensive archive of documents critical to the development of the Constitution.

This lesson is one of a series of complementary EDSITEment lesson plans for intermediate-level students about the foundations of our government. Consider adapting them for your class in the following order:

- The Argument of the Declaration of Independence

- (Present lesson plan)

- Balancing Three Branches at Once: Our System of Checks and Balances:

- The First Amendment: What's Fair in a Free Country

NCSS. D2.Civ.3.9-12. Analyze the impact of constitutions, laws, treaties, and international agreements on the maintenance of national and international order.

NCSS.D2.Civ.4.9-12. Explain how the U.S. Constitution establishes a system of government that has powers, responsibilities, and limits that have changed over time and that are still contested.

NCSS. D2.His.3.9-12. Use questions generated about individuals and groups to assess how the significance of their actions changes over time and is shaped by the historical context.

NCSS. D2.His.4.9-12. Analyze complex and interacting factors that influenced the perspectives of people during different historical eras.

NCSS. D2.His.5.9-12. Analyze how historical contexts shaped and continue to shape people’s perspectives.

NCSS. D2.His.6.9-12. Analyze the ways in which the perspectives of those writing history shaped the history that they produced.

NCSS. D2.His.14.9-12. Analyze multiple and complex causes and effects of events in the past.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.1. Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.2. Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of the source distinct from prior knowledge or opinions.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.6. Identify aspects of a text that reveal an author’s point of view or purpose (e.g., loaded language, inclusion or avoidance of particular facts).

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.10. By the end of grade 8, read and comprehend history/social studies texts in the grades 6-8 text complexity band independently and proficiently.

The following resources are included with this lesson plan to be used in conjunction with the student activities and for teacher preparation.

- Activity 1. Student Worksheet

- Activity 2. Teachers Guide to the Preamble

- Activity 2. Graphic Organizer

Review the Graphic Organizer for Activity 2, which contains the Preamble to the Constitution along with the opening passages of the Articles of Confederation and the second paragraph of the Declaration of Independence (both from OurDocuments.gov ), and make copies for the class.

Activity 1. Why Government?

To help students understand the enormous task facing the Americans, pose a hypothetical situation to the class:

Imagine that on a field trip to a wilderness area or sailing trip to a small, remote island, you all became stranded without any communication with parents, the school, or other adults and had little hope of being rescued in the foreseeable future. The area where you’re marooned can provide the basic necessities of food, shelter, and water, but you will have to work together to survive.

Encourage students to think about the next steps they need to take with a general discussion about such matters as:

- Are you better working together or alone? (Be open to their ideas, but point out reasons why they have a better chance at survival if they work together.)

- How will you work together?

- How will you create rules?

- Who will be responsible for leading the group to help all survive?

- How will they be chosen?

- How will you deal with people in the group who may not be following the rules?

Distribute the Student Worksheet handout , which contains the seven questions below. [ Note: These questions are related to the seven phrases from the Preamble but this relationship in not given on the handout. ]

Divide students into small groups and have each group brainstorm a list of things they would have to consider in developing its own government. [ Note: You can have all groups answer all seven questions or assign one question for each group.] Ask students to be detailed in their answers and be able to support their recommendations.

- How will you make sure everyone sticks together and works towards the common goal of getting rescued? (form a more perfect union)

- How will you make sure that anyone who feels unfairly treated will have a place to air complaints? (establishing justice)

- How will you make sure that people can have peace and quiet? (ensuring domestic tranquility)

- How will you make sure that group members will help if outsiders arrive who threaten your group? (providing for the common defense)

- How will you make sure that the improvements you make on the island (such as shelters, fireplaces and the like) will be used fairly? (promoting the general welfare)

- How will you make sure that group members will be free to do what they want as long as it doesn't hurt anyone else? (securing the blessing of liberty to ourselves)

- How will you make sure that the rules and organizations you develop protect future generations? (securing the blessing of liberty to our posterity)

While students are working in their groups, write or project the following seven headers on the front board in this order:

- Secure the Blessings of Liberty for our Posterity,

- Promote the General Welfare,

- Establish Justice,

- Form a more perfect Union,

- Insure Domestic Tranquility,

- Secure the Blessings of Liberty to Ourselves, and

- Provide for the Common Defense

After the groups have finished discussing their questions, have them meet as a class. First ask them to identify which question (by number) from their handout goes with which section of the Preamble of the U.S. Constitution you’ve listed on the front board. Next, have students share their recommendations to the questions and allow other groups to comment, add, or disagree with the recommendations made.

Exit Ticket:

Encourage class discussion of the following questions:

- Having just released themselves from Britain's monarchy, what would the colonists fear most?

- Judging from some of the complaints the colonists had against Britain, what might be some of their concerns for any future government?

As in the hypothetical situation described above, what decisions would the colonists have to make about forming a new government out of 13 colonies which, until 1776, had basically been running themselves independently?

Activity 2. What the Preamble Says

Review the Teachers' Guide to the Preamble , which parses each of the phrases of the Preamble and contrasts them with the equivalent passages in the Articles and the Declaration. Teachers can use this guide as a source for a short lecture before the activity and as a kind of answer sheet for the activity.

In this activity, students investigate the Preamble to the Constitution by comparing and contrasting it with the opening language of the Articles of Confederation. They will:

- understand how the Preamble of the Constitution (in outlining the goals of the new government under the Constitution) was written with the deficiencies of the Articles of Confederation in mind, aiming to create “a more perfect union,” and

- understand how the Preamble drew its justification from the principles outlined in the Declaration of Independence.

The aim of this activity is to show students, through a close reading of the Preamble, how its style and content reflect some of the aspirations of the framers for the future of republican government in America.

[ Note: teachers should define “diction,” “connotation,” and “denotation” to the students before beginning to ask students to differentiate between language in the two documents. ]

Distribute copies of the Graphic Organizer and questions to all students and have them complete it in their small groups (or individually as a homework assignment).

Have one or two students or groups of students summarize their conclusions concerning the critical differences between the Articles and the Preamble, citing the sources of these documents as referents.

Have students answer the following in a brief, well-constructed essay:

Using the ideas and information presented in this lesson, explain how the wording and structure of the Preamble demonstrate that the Constitution is different from the Articles of Confederation.

Note: For an excellent example of what can be inferred from the language and structure of the Preamble, teachers should review and model this passage by Professor Garret Epps from “ The Poetry of the Preamble ” on the Oxford University Press blog (2013):

“Form, establish, insure, provide, promote, secure”: these are strong verbs that signify governmental power, not restraint. “We the people” are to be bound—into a stronger union. We will be protected against internal disorder—that is, against ourselves—and against foreign enemies. The “defence” to be provided is “common,” general, spread across the country. The Constitution will establish justice; it will promote the “general” welfare; it will secure our liberties. The new government, it would appear, is not the enemy of liberty but its chief agent and protector.

Students could be asked whether they agree or disagree with the above interpretation. They should be expected to provide evidence-based arguments for their position.

The aspirational rhetoric of the Preamble has inspired various social movements throughout our nation’s history. In particular, two 19th-century developments come to mind: the struggles for abolitionism and women's suffrage. Examples of oratory from each movement are provided below. In response to one of these excerpts, students can write a short essay about how the words of the Preamble affected the relevant movement.

- Students should ascertain what the Preamble meant to the movement and how it was used to make an appeal to the nation. The essay might address the question of how and why those such as Frederick Douglass and Susan B. Anthony, who at their time were excluded from the full range of rights and liberties ensured by the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, responded to the principles expressed in the Preamble.

- Students should then argue either for or against the interpretation of the Preamble advanced in the excerpt, drawing from the knowledge gained in this lesson.

Be sure that the essay has a strong thesis (a non-obvious, debatable proposition about the Preamble) that students support with evidence from the texts used in this lesson.

Example 1. Frederick Douglass, “ What to the Slave is the Fourth of July ?” (1852)

Fellow-citizens! there is no matter in respect to which, the people of the North have allowed themselves to be so ruinously imposed upon, as that of the pro-slavery character of the Constitution. In that instrument I hold there is neither warrant, license, nor sanction of the hateful thing; but, interpreted as it ought to be interpreted, the Constitution is a GLORIOUS LIBERTY DOCUMENT. Read its preamble, consider its purposes. Is slavery among them? Is it at the gateway? or is it in the temple? It is neither.

Example 2. Susan B. Anthony, “ Is It a Crime for a U.S. Citizen to Vote? ” ( 1873)

It was we, the people; not we, the white male citizens; nor yet we, the male citizens; but we, the whole people, who formed the Union. And we formed it, not to give the blessings of liberty, but to secure them; not to the half of ourselves and the half of our posterity, but to the whole people—women as well as men. And it is a downright mockery to talk to women of their enjoyment of the blessings of liberty while they are denied the use of the only means of securing them provided by this democratic-republican government—the ballot.

Materials & Media

Preamble close reading: activity 1 student worksheet, preamble close reading: activity 2 graphic organizer, preamble close reading: activity 2 teachers guide, related on edsitement, a day for the constitution, commemorating constitution day, the constitutional convention of 1787.

Knowledge for Freedom seminar

Hosted by Dickinson College with support from the Teagle Foundation

Close Reading of Declaration of Sentiments (1848)

By etsub taye, a case for equal rights.

In 1848, the first women’s convention was held in Seneca Falls, New York. At the convention “The Declaration of Sentiments” was drafted to assert the natural rights of women as being equal to the natural rights of men. The author, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, mimicked the language and structure of “The Declaration of Independence,” using evocative language to draw comparisons in order to advocate for the equal rights of women. However, despite drawing a parallel between the two documents, Stanton failed in elevating her document to revolutionary status.

Stanton’s decision to draw a comparison between women’s rights to a document written 72 years prior was strategic because it captured the attention of its audience. Furthermore, the document repeats the philosophy of John Locke’s “Second Treatise of Government” which declared that all people had a natural or inherent right. Knowing the influence of Locke on Jefferson, Stanton showcased the validity of her argument by describing the disenfranchisement of women in a list of grievances. Stanton wrote “he has” then would interchange a strong verb to evoke emotion. She employed the use of words like “suffer,” “deprive,” “abuse,” over 40 times to compel sympathy. [1] Like Jefferson, Stanton used passive language to showcase women’s injuries. This allowed her to emphasize that women were being barred from accessing their natural rights which as a result gave her standing to protest for change.

The caveat to modeling The Declaration of Sentiments so heavily on The Declaration of Independence however is that it was always going to be overshadowed. Its lack of originality prevented it from ever achieving the same amount of lasting notoriety.

It is also important to recognize that Stanton was petitioning for the rights of educated wealthy white women like her, not for all men and women. She does not explicitly advocate for the rights of the enslaved. Moreover, unlike “The Declaration of Independence,” Stanton does not fully commit to protesting like Jefferson. Her call for women to demand “equal status to which they are entitled” diverges from Jefferson’s call to colonists to “alter their former systems of government.” Stanton’s aim was not to separate from the current government but to work within it. [2] This is not surprising since the resolution for women’s right to vote at the convention was a point of contention among delegates in 1848. Given the public reaction to the document, many women of the convention were hesitant to be radical in fear of their lives.

When further comparing the two documents, “The Declaration of Sentiments” demonstrates their fear as it lacks force. For instance the document “insists” on equal rights and promises to pursue them by stating “we shall employ agents, circulate tracts, petition the pulpit and the press on our behalf.” [3] The forms of protest they chose to make were significant but not nearly disruptive enough to be revolutionary. Nevertheless, the efforts of Stanton and “The Declaration of Sentiments” should be celebrated and remembered. Although the document didn’t warrant immediate change it served as a foundation for the suffragist movement.

Excerpt from “The Declaration of Sentiments,” Seneca Falls Convention (1848), read by Etsub Taye

- Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Declaration of Sentiments, July 19, 1848, Seneca Falls, NY, Reproduced by the National Park Service

- Stanton, Declaration of Sentiments; Thomas Jefferson, et al, Declaration of Independence: A Transcription, July 4, 1776, Philadelphia, PA, Reproduced by National Archives

- Stanton, Declaration of Sentiments

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Description. To build on their understanding of the American Revolution and the Declaration of Independence, students read part of the first section of the article "Thomas Jefferson and the Declaration of Independence.". The second section of the article is read in Lesson 10. Students closely examine how and why the Declaration of ...

Unit Objective. Exact facsimile of the original Declaration of Independence, reproduced in 1823 by William Stone. (Gilder Lehrman Collection) This unit is part of Gilder Lehrman's series of Common Core State Standards-based teaching resources. These units were written to enable students to understand, summarize, and analyze original texts ...

The Declaration of Independence is a statement originally composed by Thomas Jefferson, then adopted by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776. It announced that the 13 American colonies, then at war with Great Britain, regarded themselves as independent states, and no longer a part of the British Empire. Activity Two—Close Reading ...

The Declaration of Independence Close Reading. You will be doing a close reading of the Declaration of Independence—one of the most important documents in American history. This document set in motion a series of events that is still being argued about today. From what the phrase "all men are created equal"

On July 2, 1776, after months of deliberation and while directing battle in the colonies and Canada, the Second Continental Congress voted to declare the "united States of America" separate and independent from Britain. On July 4, the Congress approved the final wording of the Declaration, written primarily by Thomas Jefferson.

20 minutes. Divide the class into pairs or trios. Distribute Handout A: The Declaration of Independence and Handout C: The Structure of the Declaration to each group. 1. Assign each group one section of the Declaration to focus on. Additionally, all groups should do the signature section.

A. Close Reading: Excerpt of the Declaration of Independence, Part III (25 minutes) B. Text-Based Discussion: Character Reaction to the Declaration of Independence (20 minutes) 3. Closing and Assessment. A. Reflecting on Discussion (10 minutes) 4. Homework. A. Accountable Research Reading. Select a prompt and respond in the front of your ...

In this lesson, students closely read an excerpt of the Declaration of Independence to prepare for a text-based discussion about what characters from Divided Loyalties would think of it (RL.4.1, RL.4.3, RI.4.1, RI.4.4, SL.4.1, L.4.4). This is practice for Part II of the mid-unit assessment, in which students will participate in a similar text ...

The organization of the Declaration of Independence reflects what has come to be known as the classic structure of argument—that is, an organizational model for laying out the premises and the supporting evidence, the contexts and the claims for argument. According to its principal author, Thomas Jefferson, the Declaration was intended to be ...

Speed. IN CONGRESS, July 4, 1776. The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America, When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the... Educators only.

This close reading lesson is the first of many to come! It is written using 4th grade CCSS, but can easily be adjusted for 5th or 6th grades. It includes a detailed lesson of the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd reading of the the first section of the Declaration of Independence, vocabulary lesson that targets key words in the text, text-dependent questions, and an informational writing assignment.

Lesson OverviewThis lesson, which will require multiple class periods to complete, involves a close reading of selected portions of The Declaration of Independence. The lesson will begin by establishing students' background knowledge regarding the American Revolution and the subsequent writing of The Declaration of Independence. Vocabulary pertinent to the Declaration will be taught via a ...

the Declaration of Independence. The Declaration of Independence is one of the most important documents in the history of the United States. It was an official act taken by all 13 American colonies in declaring independence from British rule. This is a painting by John Trumbull that shows the committee presenting the Declaration of Independence ...

July 3rd, 2013. On July 4, 1776, two days after it adopted the Lee Resolution that declared the united colonies' independence from Great Britain, the Continental Congress approved the Declaration of Independence, drafted by Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), which explains that decision by "declar [ing] the causes which impel them to the ...

Activity Two—Close Reading/Annotation of the Text. Read the Declaration of Independence printed for you below. As you read, use the questions in the right margin to guide your annotations. (Keep in mind that this document was written before the regulation of spelling and capitalization.) You will complete paragraphs 1-2 as a class.

He was the third president of the United States of America. Thomas Jefferson was also the writer of the Declaration of Independence. He wrote ideas about people and govern ... ReadWorks is an edtech nonprofit organization that is committed to helping to solve America's reading comprehension crisis.

Objectives. After completing this learning activity, students will be able to: •. Explain the importance of the Declaration of Independence. • Identify and/or analyze key concepts put forth in the Declaration of Independence. • Evaluate alternative wording choices in the Declaration and defend their decisions. Time Required.

A super bundle of 10 reading assignments about the foundations of the US government. Articles about the Enlightenment, Treaty of Paris 1763, Stamp Act, Boston Massacre and Tea Party, and the Declaration of Independence are included. This is a great way to introduce these subjects, and best of all, there is no prep time required with this bundle!

2. Plan activities where they read excerpts from the document closely and carefully. Phrases and sentences work here—select them carefully and scaffold student work with strategies like pair work, paraphrasing, and vocabulary help. Some other ideas include: Looking at the original document. Sign the document.

In Congress, July 4, 1776. The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America, When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and ...

In this activity, students will read Elizabeth Cady Stanton's Declaration of Sentiments from the Women's Rights Convention in Seneca Falls in 1848, and compare the text of the Declaration of Sentiments to the Declaration of Independence. Separate graphic organizers for middle and high school guide students through a close reading of the text using the ELA strategy, "What does it say?

Preamble close reading: Activity 2 Teachers Guide. The Preamble is the introduction to the United States Constitution, and it serves two central purposes. First, it states the source from which the Constitution derives its authority: the sovereign people of the United States. Second, it sets forth the ends that the Constitution and the ...