Differences Between Review Paper and Research Paper

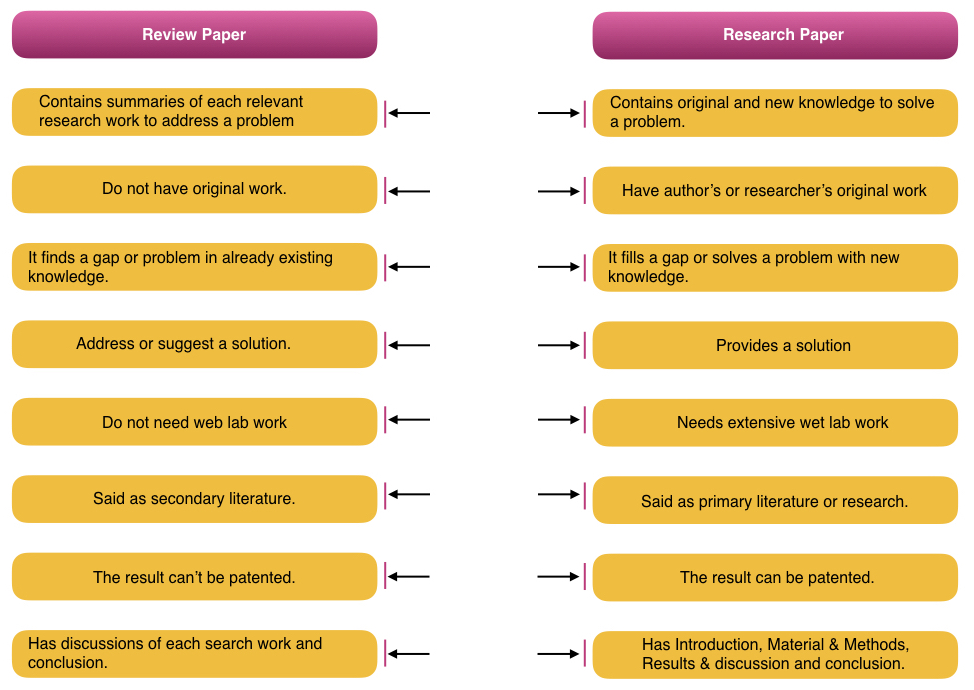

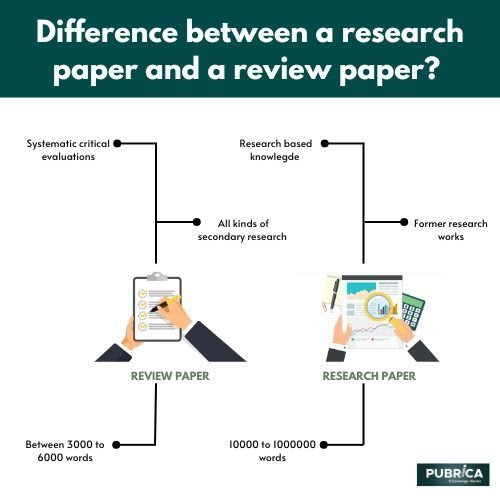

A research paper includes original work while a review paper includes the summary of existing work which explains or solves a specific problem.

An integral part of a PhD dissertation or thesis is writing a research and review article, besides writing a thesis, proposal and synopsis. In addition, one also has to publish an article in a peer-reviewed journal which is indeed a tougher task, right!

Writing is an indispensable part of the doctorate degree and has significant value in honoring the same degree. A student when becoming a PhD candidate has to write a thesis statement, research proposal, synopsis of the doctorate, thesis, research article and review article, in chronological order.

If one fails to do so, they can’t get a degree. And that’s why writing is important. Nonetheless, students face problems while writing either research or review articles.

Supportive evidence suggests that students actually don’t know the basic and major differences between either so fail to publish both article types.

In the present piece of content, I will explain the importance of a review and research article as well as the differences between both. I am hoping that this article will add value to your knowledge and help you in your PhD.

Stay tuned.

What is a Review Paper?

What is a research paper, review vs research paper: differences, research article vs review article- similarities:, wrapping up: .

A review chapter or review articles add value to the thesis as well as existing knowledge. Universities are usually recommended to write and publish it. From students’ perspectives, review writing frightens them.

However, from a supervisors’ perspective, it should be precise, concise and nearly perfect.

Review writing is a tedious, frustrating and time-consuming process that needs special attention. The reason why it should be nearly perfect is that it supports researchers’ original work.

Technically, the review article comprises a summary of the existing research in a structured manner. Normally, it addresses the original research work and solves the existing problem by literature.

However, it can’t solve any existing problem, it doesn’t need wet-lab experimentation. It only shows the existing state of understanding of a topic. Notedly, an expert of the subject, experienced person, professor and professional scientist can usually write a review.

A research paper/article contributes original research or work of a researcher on the present topic, usually includes web lab work. Much like the review, a research article should be published in a peer-reviewed journal too.

Research article writing takes too much time as it includes research work additionally. Comprehensive writing is required to explain the materials & methods section and results & outcomes while the elaborative explanation is sufficient to introduce a topic.

Structurally a typical research article or paper has an introduction or background, Materials & Methods, Results & discussion and conclusion.

Depending upon the requirement of the journal and the depth or concentration of the research, the length of the article may vary, however, ordinarily is between 2 to 8 pages.

Much like the review article, an abstract and a list of references must be included in the article.

In summary, the research paper provides new knowledge in the relevant field and solves an existing problem by it.

Now quickly move to the important part of this article, what are the differences between the review and research paper?

A review article is certainly a comprehensive, in-depth and extensively well-written piece of information covering summaries of already present knowledge. While the research article constitutes an elaborative introduction of the topic and an in-depth explanation of how the research was conducted. It contributes new knowledge.

A review is written based on the already existing information and so considered as a secondary source of information, while the research paper has original research work supported by already existing sources.

In terms of length, a review article has an in-depth explanation and so are longer, normally, 10 to 20 pages whilst the research article has an elaborative explanation and to the point information on the problem, usually ranging from 2 to 8 pages.

The review article addresses the problem whilst the research article solves the problem, certainly.

The conclusion of the review article supports the already present findings while the result of the research article is supported by the existing research work.

The purpose of writing a research paper is to critically analyze already existing or previous work in the form of short summaries. And restricted to a specific topic.

On the other side, the research article includes the author’s own work in detail

Structurally, the review article has a single heading or sometimes a conclusion at the end of the article whilst the research article has sections like an introduction to the topic, materials & methods, results, discussion and final interpretation.

Steps in review article writing are,

- Topic finding

- Searching relevant sources

- Summarising each source

- Correlating them with the topic or problem

- Concluding the research.

Steps in research article writing are,

- Choosing a problem or gap in present findings

- Sample collection, experimentation and wet lab work

- Finding, collecting and organizing the data

- Correlating it with the present knowledge

- Stating results

- Final interpretation.

Normally, a subject expert or experienced person can write a review article while any student, or person having the original research work can write a research article.

The review article defines or clarifies a problem, explains it by compiling previous investigations and suggests problem-solving strategies or options. On the other hand, the research article has an original problem-solving statement supported by various chapters and previous research.

So the review article suggests possible outcomes to fill the knowledge gap while the research article provides evidence and new knowledge on how to fill the gap.

Summary:

Either document has been written for a different purpose which solves almost the same objective. Fortunately, there are several similarities in writing a research or review article. Hera re some,

Both have in-text citations, a references page, an abstract and contributors. Both also need a final conclusion too in order to address or solve a problem.

Research or review articles can be submitted or published in peer-reviewed journals.

Both require educational, professional, informal and research writing skills.

Importantly, both articles must be plagiarism-free, copying isn’t recommended.

Every PhD student must have written at least a single review and research article during their research or doctoral tenure to get an award. Achieving a successful publication needs critical writing skills and original research or findings.

The major difference between either is that the review article has summed information that directs one towards solving a problem and so does not include original work.

Whilst the research article actually proposes a way to solve a problem and so has original work.

Dr. Tushar Chauhan is a Scientist, Blogger and Scientific-writer. He has completed PhD in Genetics. Dr. Chauhan is a PhD coach and tutor.

Share this:

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Pinterest

- Share on Linkedin

- Share via Email

About The Author

Dr Tushar Chauhan

Related posts.

Difference between M.D vs PhD

Doctorate vs PhD- differences and similarities

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

- Study resources

- Calendar - Graduate

- Calendar - Undergraduate

- Class schedules

- Class cancellations

- Course registration

- Important academic dates

- More academic resources

- Campus services

- IT services

- Job opportunities

- Safety & prevention

- Mental health support

- Student Service Centre (Birks)

- All campus services

- Calendar of events

- Latest news

- Media Relations

- Faculties, Schools & Colleges

- Arts and Science

- Gina Cody School of Engineering and Computer Science

- John Molson School of Business

- School of Graduate Studies

- All Schools, Colleges & Departments.

- Directories

- My Library account Renew books and more

- Book a study room or scanner Reserve a space for your group online

- Interlibrary loans (Colombo) Request books from external libraries

- Zotero (formerly RefWorks) Manage your citations and create bibliographies

- Article/Chapter Scan & Deliver Request a PDF of an article/chapter we have in our physical collection

- Contactless Book Pickup Request books, DVDs and more from our physical collection while the Library is closed

- WebPrint Upload documents to print on campus

- Course reserves Online course readings

- Spectrum Deposit a thesis or article

- Sofia Discovery tool

- Databases by subject

- Course Reserves

- E-journals via Browzine

- E-journals via Sofia

- Article/chapter scan

- Intercampus delivery of bound periodicals/microforms

- Interlibrary loans

- Spectrum Research Repository

- Special Collections

- Additional resources & services

- Subject & course guides

- Open Educational Resources Guide

- Borrowing & renewing

- General guides for users

- Evaluating...

- Ask a librarian

- Research Skills Tutorial

- Bibliometrics & research impact guide

- Concordia University Press

- Copyright guide

- Copyright guide for thesis preparation

- Digital scholarship

- Digital preservation

- Open Access

- ORCiD at Concordia

- Research data management guide

- Scholarship of Teaching & Learning

- Systematic Reviews

- Borrow (laptops, tablets, equipment)

- Connect (netname, Wi-Fi, guest accounts)

- Desktop computers, software & availability maps

- Group study, presentation practice & classrooms

- Printers, copiers & scanners

- Technology Sandbox

- Visualization Studio

- Webster Library

- Vanier Library

- Grey Nuns Reading Room

- Study spaces

- Floor plans

- Book a group study room/scanner

- Room booking for academic events

- Exhibitions

- Librarians & staff

- Work with us

- Memberships & collaborations

- Indigenous Student Librarian program

- Wikipedian in residence

- Researcher in residence

- Feedback & improvement

- Annual reports & fast facts

- Strategic Plan 2016/21

- Library Services Fund

- Giving to the Library

- Policies & Code of Conduct

- My Library account

- Book a study room or scanner

- Interlibrary loans (Colombo)

- Zotero (formerly RefWorks)

- Article/Chapter Scan & Deliver

- Contactless Book Pickup

- Course reserves

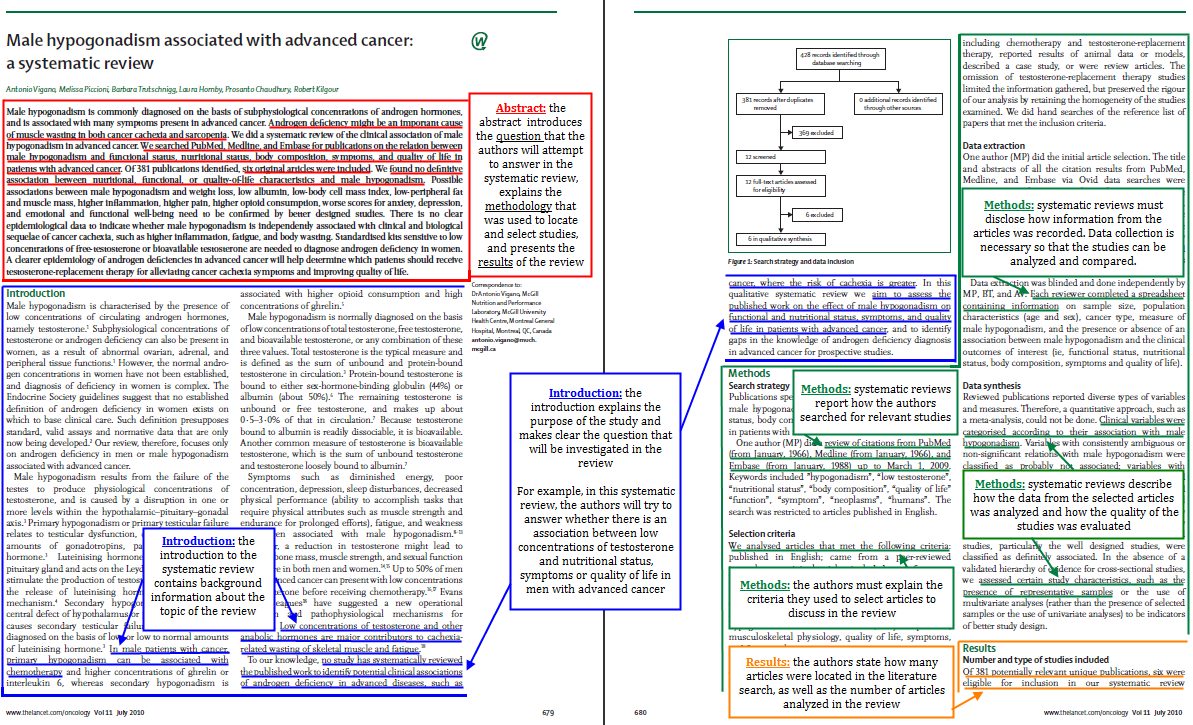

Review vs. Research Articles

How can you tell if you are looking at a research paper, review paper or a systematic review examples and article characteristics are provided below to help you figure it out., research papers.

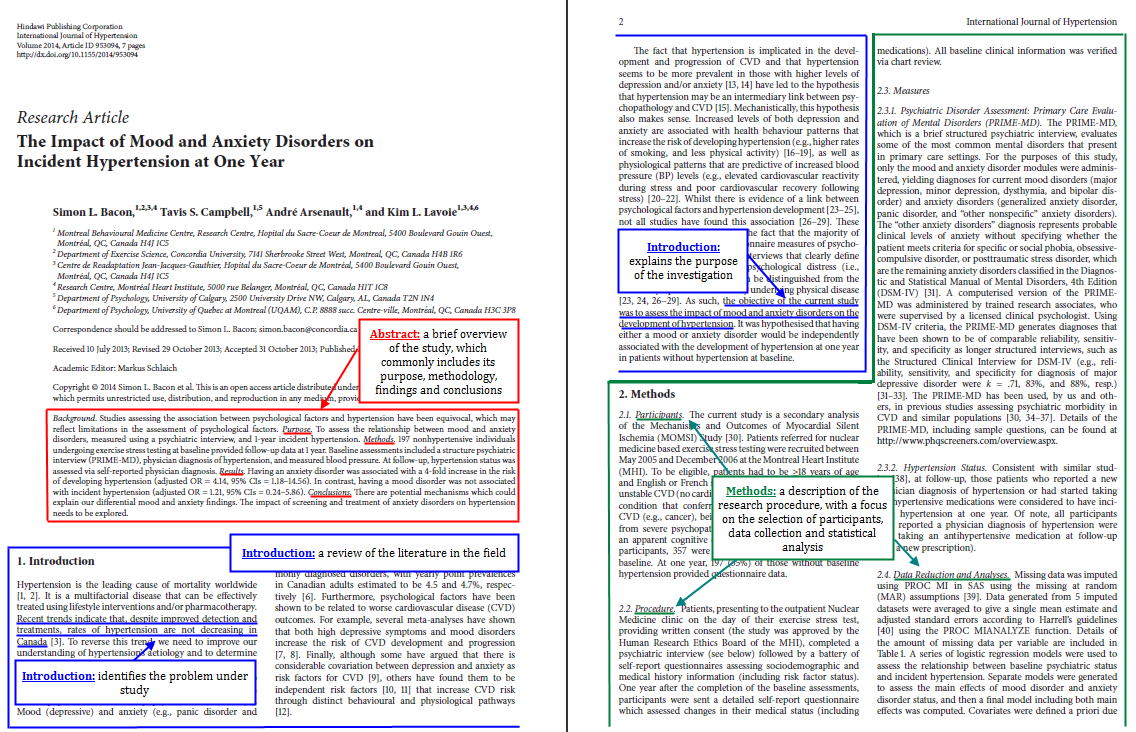

A research article describes a study that was performed by the article’s author(s). It explains the methodology of the study, such as how data was collected and analyzed, and clarifies what the results mean. Each step of the study is reported in detail so that other researchers can repeat the experiment.

To determine if a paper is a research article, examine its wording. Research articles describe actions taken by the researcher(s) during the experimental process. Look for statements like “we tested,” “I measured,” or “we investigated.” Research articles also describe the outcomes of studies. Check for phrases like “the study found” or “the results indicate.” Next, look closely at the formatting of the article. Research papers are divided into sections that occur in a particular order: abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, and references.

Let's take a closer look at this research paper by Bacon et al. published in the International Journal of Hypertension :

Review Papers

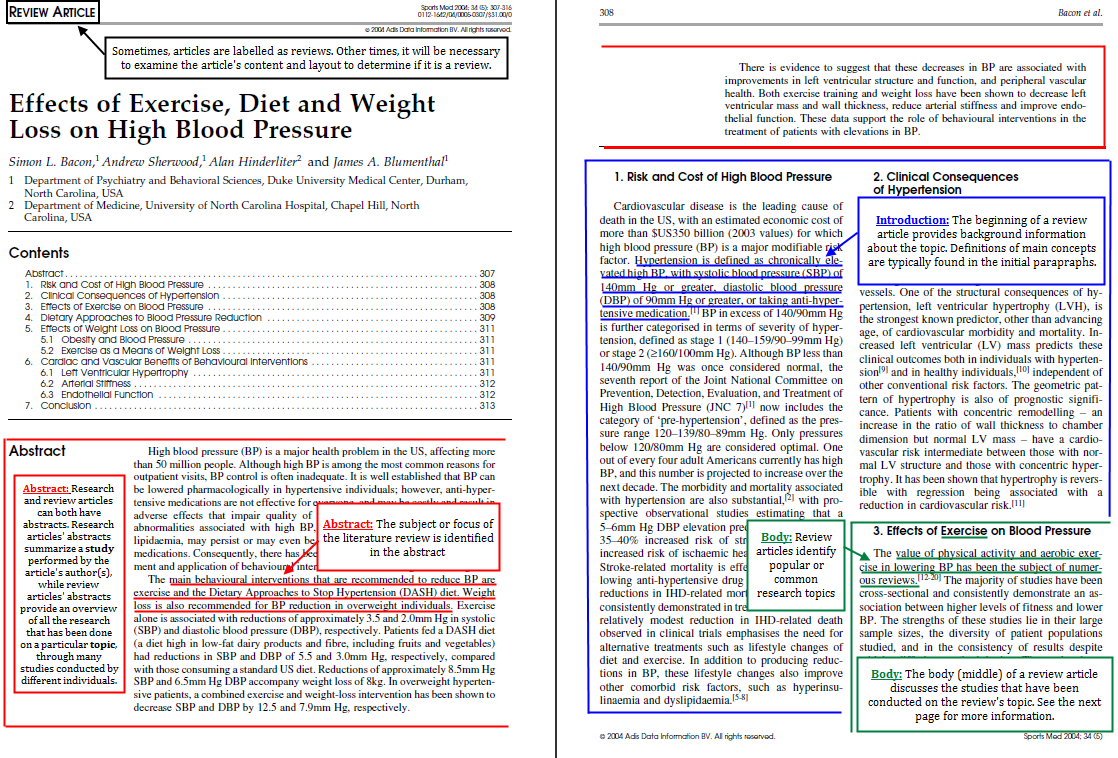

Review articles do not describe original research conducted by the author(s). Instead, they give an overview of a specific subject by examining previously published studies on the topic. The author searches for and selects studies on the subject and then tries to make sense of their findings. In particular, review articles look at whether the outcomes of the chosen studies are similar, and if they are not, attempt to explain the conflicting results. By interpreting the findings of previous studies, review articles are able to present the current knowledge and understanding of a specific topic.

Since review articles summarize the research on a particular topic, students should read them for background information before consulting detailed, technical research articles. Furthermore, review articles are a useful starting point for a research project because their reference lists can be used to find additional articles on the subject.

Let's take a closer look at this review paper by Bacon et al. published in Sports Medicine :

Systematic Review Papers

A systematic review is a type of review article that tries to limit the occurrence of bias. Traditional, non-systematic reviews can be biased because they do not include all of the available papers on the review’s topic; only certain studies are discussed by the author. No formal process is used to decide which articles to include in the review. Consequently, unpublished articles, older papers, works in foreign languages, manuscripts published in small journals, and studies that conflict with the author’s beliefs can be overlooked or excluded. Since traditional reviews do not have to explain the techniques used to select the studies, it can be difficult to determine if the author’s bias affected the review’s findings.

Systematic reviews were developed to address the problem of bias. Unlike traditional reviews, which cover a broad topic, systematic reviews focus on a single question, such as if a particular intervention successfully treats a medical condition. Systematic reviews then track down all of the available studies that address the question, choose some to include in the review, and critique them using predetermined criteria. The studies are found, selected, and evaluated using a formal, scientific methodology in order to minimize the effect of the author’s bias. The methodology is clearly explained in the systematic review so that readers can form opinions about the quality of the review.

Let's take a closer look this systematic review paper by Vigano et al. published in Lancet Oncology :

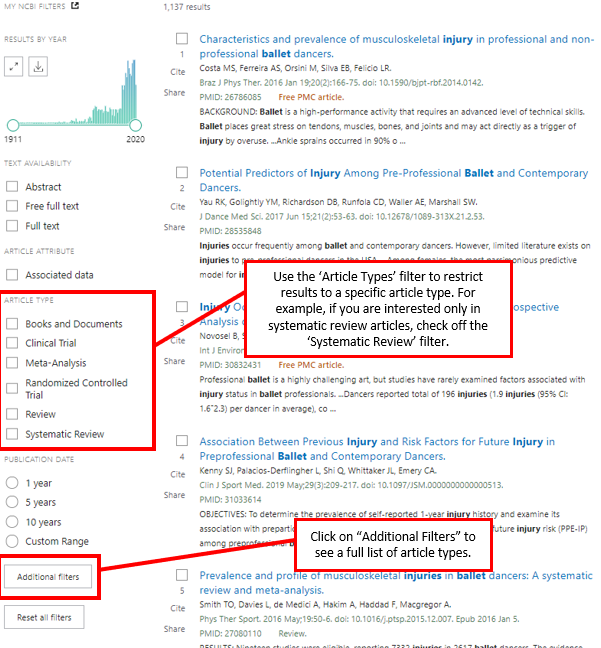

Finding Review and Research Papers in PubMed

Many databases have special features that allow the searcher to restrict results to articles that match specific criteria. In other words, only articles of a certain type will be displayed in the search results. These “limiters” can be useful when searching for research or review articles. PubMed has a limiter for article type, which is located on the left sidebar of the search results page. This limiter can filter the search results to show only review articles.

© Concordia University

- Interesting

- Scholarships

- UGC-CARE Journals

Research Paper Vs Review Paper | 50 Differences

50 Differences Between Research Article and a Review Article

Table of contents

A research paper is a piece of writing that reports facts, data, and other information on a specific topic. It is usually longer than a review paper and includes a detailed evaluation of the research. Whereas, a review paper is a shorter piece of writing that summarizes and evaluates the research on a specific topic. It is usually shorter than a research paper and does not include a detailed evaluation of the research. In this article, we have listed the 50 important differences between a review paper vs research article.

- A research paper is typically much longer than a review paper.

- A research paper is typically more detailed and comprehensive than a review paper.

- A research paper is typically more focused on a specific topic than a review paper.

- A research paper is typically more analytical and critical than a review paper.

- A research paper is typically more objective than a review paper.

- A research paper is typically written by one or more authors, while a review paper may be written by a single author.

- A research paper is typically peer-reviewed, while a review paper may not be.

- A research paper is typically published in a scholarly journal, while a review paper may be published in a variety of different publications.

- The audience for a research paper is typically other scholars, while the audience for a review paper may be the general public.

- The purpose of a research paper is typically to contribute to the scholarly literature, while the purpose of a review paper may be to provide an overview of the literature or to evaluate a particular research study.

- The structure of a research paper is typically more complex than the structure of a review paper.

- A research paper typically includes an abstract, while a review paper may not.

- A research paper typically includes a literature review, while a review paper may not.

- A research paper typically includes a methodology section, while a review paper may not.

- A research paper typically includes results and discussion sections, while a review paper may not.

- A research paper typically includes a conclusion, while a review paper may not.

- A research paper is typically organized around a central research question , while a review paper may be organized around a central theme.

- A research paper typically uses primary sources, while a review paper may use both primary and secondary sources.

- A research paper is typically based on empirical research, while a review paper may be based on either empirical or non-empirical research.

- A research paper is typically more formal than a review paper.

- A research paper is typically written in the third person, while a review paper may be written in the first person.

- A research paper typically uses formal language, while a review paper may use more informal language.

- A research paper is typically objective in tone, while a review paper may be more subjective in tone.

- A research paper typically uses APA style, while a review paper may use a different style.

- A research paper typically includes a title page, while a review paper may not.

- A research paper typically includes an abstract on the title page, while a review paper may not.

- A research paper typically includes keywords on the title page, while a review paper may not.

- A research paper typically includes an author note, while a review paper may not.

- A research paper is typically organized around a central research question, while a review paper may be organized around a central theme.

- A research paper is typically longer than a review paper.

I hope, this article would help you to know the differences between Research Paper and a Review Paper.

Also Read: What is a Research Design? Importance and Types

- Difference between

- evaluation review paper

- Research Paper

What is a Research Design? Importance and Types

Z-library is legal you can download 70,000,000+ scientific articles for free, top scopus indexed journals in aviation and aerospace engineering, email subscription.

iLovePhD is a research education website to know updated research-related information. It helps researchers to find top journals for publishing research articles and get an easy manual for research tools. The main aim of this website is to help Ph.D. scholars who are working in various domains to get more valuable ideas to carry out their research. Learn the current groundbreaking research activities around the world, love the process of getting a Ph.D.

WhatsApp Channel

Join iLovePhD WhatsApp Channel Now!

Contact us: [email protected]

Copyright © 2019-2024 - iLovePhD

- Artificial intelligence

What is the Difference between a Research Paper and a Review Paper?

What is the difference between a systematic review and a meta-analysis?

Review of the Journal’s Editing: Current State and Future Plans

Original research is the foundation of a research paper. Experiments, surveys, interviews, questionnaires, and other types of analysis may be used depending on the field or subject. Still, authors must collect and analyse raw data and perform an original report. The study and interpretation of this data will be the foundation of the research paper. A review article, also known as a review paper, is a piece of writing focused on previously published papers. It does not include any new studies. In general, review papers summarise the existing literature on a subject to clarify the current state of knowledge on the subject.

Introduction

The terms “review paper” and “research paper” are not interchangeable. Both have similar characteristics and may even be related, but some variations exist. For Example, the research paper is an academic writing style in which the student must respond to an important, systematic, and theoretical level of questioning. Similarly, a review paper allows students to interpret what they have learned about the subject matter to demonstrate a thorough understanding by writing. For Example, it can be up to 5,000 words long and come in various formats (1) .

Research paper

Regardless of the topic, a research paper has a basic structure: the title page, table of contents, introduction/background information, literature review, methodology, findings, discussion, and conclusions/recommendations. Individually these parts have their own set of writing guidelines. The framework is usually the same regardless of the issue question under investigation. This form of paper typically necessitates a significant amount of time for study and writing. There are several different study forms, each with its own characteristics based on data collection methods , such as interviews, observations, questionnaires, surveys, and experiments. Dependent on the volume and complication of the problem question, the analysis may take anything from a day to years, depending on the hypothesis and intent of the study.

Review paper

On the other hand, a review paper is used to assess students’ awareness after they have learned a few topics. For Example, following the completion of a specific theme, students may be asked to compose an essay, take a test, or complete a task related to that theme. In addition, students are expected to write review papers to show that they have acquired the necessary knowledge and skills in a particular topic.

A review paper may be written in a critical essay on a current or common topic. The student or research scholar must provide their point of view on the subject while still showing an accurate and concise understanding of the topic when it is structured in this way. The article should have some convincing points and proof or data to back them up. Generally, a review paper is written to demonstrate that a student has studied or gained knowledge of a specific topic. The review paper is usually handed in at the end of the semester and accounts for a significant portion of the final exam. The length of a review paper is generally between 3,000 and 5,000 words (2) .

The key features of a Research paper

This type of scholarly writing entails delving into a subject concept to address a specific theoretical question. A standard text is 5,000 words long, although it is often longer. The student is expected to interpret and thoroughly analyse knowledge on a given subject. It can be assigned at any time, but most instructors assign it at the start of the semester to give students ample time to collect Information and draft their papers. This type of paper often includes the compilation of primary data and its subsequent analysis.

The Key Features of a Review Paper

A student writes this paper to illustrate their understanding of a specific topic. The job is generally between 3,000 and 5,000 words long. A chosen topic should be thoroughly investigated, and the writer should express their viewpoint on the subject at hand. This assignment is typically assigned at the end of the semester and directly impacts the final grade. Scholarly journals, academic works , lab papers, and textbooks should be used as references for the review paper.

The Differences between these research and review papers

Despite this, there are certain similarities between the two assignments. First, students should choose a subject that picks their interest in each case. They use the same tools, and the paper structures can be pretty similar. The main distinction between these two types of academic writing is that a research paper can be assigned at any time and does not usually count against a student’s final grade. Another consideration for writing teachers is that a research paper often includes a hypothesis, while a review paper typically supports a thesis assertion.

Furthermore, a research paper typically includes a lengthy list of references. On the other hand, the review paper assignment usually is shorter and does not have a conclusion. Another critical distinction between a research paper and a review paper is that a research paper encourages students to participate in problem-solving activities. In contrast, a review paper assesses the student’s expertise rather than necessarily solving the problem (3) .

Conclusion

The review and the research paper are types of writing in which the first is based on the second. Both are essential parts of literature and writing since they give readers a better understanding of the topic. Reviews and research papers can be obtained from a variety of outlets. Both are different in terms of duration and material. These papers must adhere to a set of guidelines. Anyone wishing to join the world of writing must possess strong reading and analytical abilities, which will aid in writing the review and research article.

About pubrica

Pubrica’s team of researchers and authors develop Scientific and medical research papers that can act as an indispensable tools to the practitioner/authors. Pubrica medical writers help you to write and edit the introduction by introducing the reader to the shortcomings or empty spaces in the identified research field. Our experts know the structure that follows the broad topic, the problem, and the background and advance to a narrow topic to state the hypothesis.

pubrica-academy

Related posts.

What are the suggestions given by peer reviewers in the introduction section of the original research article?

Is there a difference between the theoretical framework and conceptual framework of the study?

Give an Example of Studies that used the QUADAS-2 tool?

Comments are closed.

How to Write a Literature Review

- What is a literature review

How is a literature review different from a research paper?

- What should I do before starting my literature review?

- What type of literature review should I write and how should I organize it?

- What should I be aware of while writing the literature review?

- For more information on Literature Reviews

- More Research Help

The purpose of an academic research paper is to develop a new argument. The literature review is one part of a research paper. In a research paper, you use the literature review as a foundation and as support for the new insight that you contribute. The focus of a literature review, however, is to summarize and analyze the arguments and ideas of others without adding new contributions.

- << Previous: What is a literature review

- Next: What should I do before starting my literature review? >>

- Last Updated: Feb 26, 2021 11:35 AM

- URL: https://midway.libguides.com/LiteratureReview

RESEARCH HELP

- Research Guides

- Databases A-Z

- Journal Search

- Citation Help

LIBRARY SERVICES

- Accessibility

- Interlibrary Loan

- Study Rooms

INSTRUCTION SUPPORT

- Course Reserves

- Library Instruction

- Little Memorial Library

- 512 East Stephens Street

- 859.846.5316

- [email protected]

Literature Reviews

What this handout is about.

This handout will explain what literature reviews are and offer insights into the form and construction of literature reviews in the humanities, social sciences, and sciences.

Introduction

OK. You’ve got to write a literature review. You dust off a novel and a book of poetry, settle down in your chair, and get ready to issue a “thumbs up” or “thumbs down” as you leaf through the pages. “Literature review” done. Right?

Wrong! The “literature” of a literature review refers to any collection of materials on a topic, not necessarily the great literary texts of the world. “Literature” could be anything from a set of government pamphlets on British colonial methods in Africa to scholarly articles on the treatment of a torn ACL. And a review does not necessarily mean that your reader wants you to give your personal opinion on whether or not you liked these sources.

What is a literature review, then?

A literature review discusses published information in a particular subject area, and sometimes information in a particular subject area within a certain time period.

A literature review can be just a simple summary of the sources, but it usually has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis. A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information. It might give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations. Or it might trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates. And depending on the situation, the literature review may evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant.

But how is a literature review different from an academic research paper?

The main focus of an academic research paper is to develop a new argument, and a research paper is likely to contain a literature review as one of its parts. In a research paper, you use the literature as a foundation and as support for a new insight that you contribute. The focus of a literature review, however, is to summarize and synthesize the arguments and ideas of others without adding new contributions.

Why do we write literature reviews?

Literature reviews provide you with a handy guide to a particular topic. If you have limited time to conduct research, literature reviews can give you an overview or act as a stepping stone. For professionals, they are useful reports that keep them up to date with what is current in the field. For scholars, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the writer in his or her field. Literature reviews also provide a solid background for a research paper’s investigation. Comprehensive knowledge of the literature of the field is essential to most research papers.

Who writes these things, anyway?

Literature reviews are written occasionally in the humanities, but mostly in the sciences and social sciences; in experiment and lab reports, they constitute a section of the paper. Sometimes a literature review is written as a paper in itself.

Let’s get to it! What should I do before writing the literature review?

If your assignment is not very specific, seek clarification from your instructor:

- Roughly how many sources should you include?

- What types of sources (books, journal articles, websites)?

- Should you summarize, synthesize, or critique your sources by discussing a common theme or issue?

- Should you evaluate your sources?

- Should you provide subheadings and other background information, such as definitions and/or a history?

Find models

Look for other literature reviews in your area of interest or in the discipline and read them to get a sense of the types of themes you might want to look for in your own research or ways to organize your final review. You can simply put the word “review” in your search engine along with your other topic terms to find articles of this type on the Internet or in an electronic database. The bibliography or reference section of sources you’ve already read are also excellent entry points into your own research.

Narrow your topic

There are hundreds or even thousands of articles and books on most areas of study. The narrower your topic, the easier it will be to limit the number of sources you need to read in order to get a good survey of the material. Your instructor will probably not expect you to read everything that’s out there on the topic, but you’ll make your job easier if you first limit your scope.

Keep in mind that UNC Libraries have research guides and to databases relevant to many fields of study. You can reach out to the subject librarian for a consultation: https://library.unc.edu/support/consultations/ .

And don’t forget to tap into your professor’s (or other professors’) knowledge in the field. Ask your professor questions such as: “If you had to read only one book from the 90’s on topic X, what would it be?” Questions such as this help you to find and determine quickly the most seminal pieces in the field.

Consider whether your sources are current

Some disciplines require that you use information that is as current as possible. In the sciences, for instance, treatments for medical problems are constantly changing according to the latest studies. Information even two years old could be obsolete. However, if you are writing a review in the humanities, history, or social sciences, a survey of the history of the literature may be what is needed, because what is important is how perspectives have changed through the years or within a certain time period. Try sorting through some other current bibliographies or literature reviews in the field to get a sense of what your discipline expects. You can also use this method to consider what is currently of interest to scholars in this field and what is not.

Strategies for writing the literature review

Find a focus.

A literature review, like a term paper, is usually organized around ideas, not the sources themselves as an annotated bibliography would be organized. This means that you will not just simply list your sources and go into detail about each one of them, one at a time. No. As you read widely but selectively in your topic area, consider instead what themes or issues connect your sources together. Do they present one or different solutions? Is there an aspect of the field that is missing? How well do they present the material and do they portray it according to an appropriate theory? Do they reveal a trend in the field? A raging debate? Pick one of these themes to focus the organization of your review.

Convey it to your reader

A literature review may not have a traditional thesis statement (one that makes an argument), but you do need to tell readers what to expect. Try writing a simple statement that lets the reader know what is your main organizing principle. Here are a couple of examples:

The current trend in treatment for congestive heart failure combines surgery and medicine. More and more cultural studies scholars are accepting popular media as a subject worthy of academic consideration.

Consider organization

You’ve got a focus, and you’ve stated it clearly and directly. Now what is the most effective way of presenting the information? What are the most important topics, subtopics, etc., that your review needs to include? And in what order should you present them? Develop an organization for your review at both a global and local level:

First, cover the basic categories

Just like most academic papers, literature reviews also must contain at least three basic elements: an introduction or background information section; the body of the review containing the discussion of sources; and, finally, a conclusion and/or recommendations section to end the paper. The following provides a brief description of the content of each:

- Introduction: Gives a quick idea of the topic of the literature review, such as the central theme or organizational pattern.

- Body: Contains your discussion of sources and is organized either chronologically, thematically, or methodologically (see below for more information on each).

- Conclusions/Recommendations: Discuss what you have drawn from reviewing literature so far. Where might the discussion proceed?

Organizing the body

Once you have the basic categories in place, then you must consider how you will present the sources themselves within the body of your paper. Create an organizational method to focus this section even further.

To help you come up with an overall organizational framework for your review, consider the following scenario:

You’ve decided to focus your literature review on materials dealing with sperm whales. This is because you’ve just finished reading Moby Dick, and you wonder if that whale’s portrayal is really real. You start with some articles about the physiology of sperm whales in biology journals written in the 1980’s. But these articles refer to some British biological studies performed on whales in the early 18th century. So you check those out. Then you look up a book written in 1968 with information on how sperm whales have been portrayed in other forms of art, such as in Alaskan poetry, in French painting, or on whale bone, as the whale hunters in the late 19th century used to do. This makes you wonder about American whaling methods during the time portrayed in Moby Dick, so you find some academic articles published in the last five years on how accurately Herman Melville portrayed the whaling scene in his novel.

Now consider some typical ways of organizing the sources into a review:

- Chronological: If your review follows the chronological method, you could write about the materials above according to when they were published. For instance, first you would talk about the British biological studies of the 18th century, then about Moby Dick, published in 1851, then the book on sperm whales in other art (1968), and finally the biology articles (1980s) and the recent articles on American whaling of the 19th century. But there is relatively no continuity among subjects here. And notice that even though the sources on sperm whales in other art and on American whaling are written recently, they are about other subjects/objects that were created much earlier. Thus, the review loses its chronological focus.

- By publication: Order your sources by publication chronology, then, only if the order demonstrates a more important trend. For instance, you could order a review of literature on biological studies of sperm whales if the progression revealed a change in dissection practices of the researchers who wrote and/or conducted the studies.

- By trend: A better way to organize the above sources chronologically is to examine the sources under another trend, such as the history of whaling. Then your review would have subsections according to eras within this period. For instance, the review might examine whaling from pre-1600-1699, 1700-1799, and 1800-1899. Under this method, you would combine the recent studies on American whaling in the 19th century with Moby Dick itself in the 1800-1899 category, even though the authors wrote a century apart.

- Thematic: Thematic reviews of literature are organized around a topic or issue, rather than the progression of time. However, progression of time may still be an important factor in a thematic review. For instance, the sperm whale review could focus on the development of the harpoon for whale hunting. While the study focuses on one topic, harpoon technology, it will still be organized chronologically. The only difference here between a “chronological” and a “thematic” approach is what is emphasized the most: the development of the harpoon or the harpoon technology.But more authentic thematic reviews tend to break away from chronological order. For instance, a thematic review of material on sperm whales might examine how they are portrayed as “evil” in cultural documents. The subsections might include how they are personified, how their proportions are exaggerated, and their behaviors misunderstood. A review organized in this manner would shift between time periods within each section according to the point made.

- Methodological: A methodological approach differs from the two above in that the focusing factor usually does not have to do with the content of the material. Instead, it focuses on the “methods” of the researcher or writer. For the sperm whale project, one methodological approach would be to look at cultural differences between the portrayal of whales in American, British, and French art work. Or the review might focus on the economic impact of whaling on a community. A methodological scope will influence either the types of documents in the review or the way in which these documents are discussed. Once you’ve decided on the organizational method for the body of the review, the sections you need to include in the paper should be easy to figure out. They should arise out of your organizational strategy. In other words, a chronological review would have subsections for each vital time period. A thematic review would have subtopics based upon factors that relate to the theme or issue.

Sometimes, though, you might need to add additional sections that are necessary for your study, but do not fit in the organizational strategy of the body. What other sections you include in the body is up to you. Put in only what is necessary. Here are a few other sections you might want to consider:

- Current Situation: Information necessary to understand the topic or focus of the literature review.

- History: The chronological progression of the field, the literature, or an idea that is necessary to understand the literature review, if the body of the literature review is not already a chronology.

- Methods and/or Standards: The criteria you used to select the sources in your literature review or the way in which you present your information. For instance, you might explain that your review includes only peer-reviewed articles and journals.

Questions for Further Research: What questions about the field has the review sparked? How will you further your research as a result of the review?

Begin composing

Once you’ve settled on a general pattern of organization, you’re ready to write each section. There are a few guidelines you should follow during the writing stage as well. Here is a sample paragraph from a literature review about sexism and language to illuminate the following discussion:

However, other studies have shown that even gender-neutral antecedents are more likely to produce masculine images than feminine ones (Gastil, 1990). Hamilton (1988) asked students to complete sentences that required them to fill in pronouns that agreed with gender-neutral antecedents such as “writer,” “pedestrian,” and “persons.” The students were asked to describe any image they had when writing the sentence. Hamilton found that people imagined 3.3 men to each woman in the masculine “generic” condition and 1.5 men per woman in the unbiased condition. Thus, while ambient sexism accounted for some of the masculine bias, sexist language amplified the effect. (Source: Erika Falk and Jordan Mills, “Why Sexist Language Affects Persuasion: The Role of Homophily, Intended Audience, and Offense,” Women and Language19:2).

Use evidence

In the example above, the writers refer to several other sources when making their point. A literature review in this sense is just like any other academic research paper. Your interpretation of the available sources must be backed up with evidence to show that what you are saying is valid.

Be selective

Select only the most important points in each source to highlight in the review. The type of information you choose to mention should relate directly to the review’s focus, whether it is thematic, methodological, or chronological.

Use quotes sparingly

Falk and Mills do not use any direct quotes. That is because the survey nature of the literature review does not allow for in-depth discussion or detailed quotes from the text. Some short quotes here and there are okay, though, if you want to emphasize a point, or if what the author said just cannot be rewritten in your own words. Notice that Falk and Mills do quote certain terms that were coined by the author, not common knowledge, or taken directly from the study. But if you find yourself wanting to put in more quotes, check with your instructor.

Summarize and synthesize

Remember to summarize and synthesize your sources within each paragraph as well as throughout the review. The authors here recapitulate important features of Hamilton’s study, but then synthesize it by rephrasing the study’s significance and relating it to their own work.

Keep your own voice

While the literature review presents others’ ideas, your voice (the writer’s) should remain front and center. Notice that Falk and Mills weave references to other sources into their own text, but they still maintain their own voice by starting and ending the paragraph with their own ideas and their own words. The sources support what Falk and Mills are saying.

Use caution when paraphrasing

When paraphrasing a source that is not your own, be sure to represent the author’s information or opinions accurately and in your own words. In the preceding example, Falk and Mills either directly refer in the text to the author of their source, such as Hamilton, or they provide ample notation in the text when the ideas they are mentioning are not their own, for example, Gastil’s. For more information, please see our handout on plagiarism .

Revise, revise, revise

Draft in hand? Now you’re ready to revise. Spending a lot of time revising is a wise idea, because your main objective is to present the material, not the argument. So check over your review again to make sure it follows the assignment and/or your outline. Then, just as you would for most other academic forms of writing, rewrite or rework the language of your review so that you’ve presented your information in the most concise manner possible. Be sure to use terminology familiar to your audience; get rid of unnecessary jargon or slang. Finally, double check that you’ve documented your sources and formatted the review appropriately for your discipline. For tips on the revising and editing process, see our handout on revising drafts .

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Jones, Robert, Patrick Bizzaro, and Cynthia Selfe. 1997. The Harcourt Brace Guide to Writing in the Disciplines . New York: Harcourt Brace.

Lamb, Sandra E. 1998. How to Write It: A Complete Guide to Everything You’ll Ever Write . Berkeley: Ten Speed Press.

Rosen, Leonard J., and Laurence Behrens. 2003. The Allyn & Bacon Handbook , 5th ed. New York: Longman.

Troyka, Lynn Quittman, and Doug Hesse. 2016. Simon and Schuster Handbook for Writers , 11th ed. London: Pearson.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- Master Your Homework

- Do My Homework

The Contrasts Between Research and Review Papers

Research and review papers are two common types of academic writing, but they have distinct differences that need to be understood in order to produce the most effective work. Research papers involve an exploration into a particular topic or field of study, while review papers provide summaries and critiques of existing research on a given subject. These distinctions must be taken into account when considering the purpose and structure of both forms of scholarly discourse. This article will examine each type more closely, discussing their respective features as well as highlighting areas where authors can improve in terms of creating effective works for either category.

I. Introduction to Research and Review Papers

Ii. comparison of structure between research and review papers, iii. differences in content for research vs. review papers, iv. distinctions in language used for each type of paper, v. in-depth analysis of the purposes served by each paper type, vi. advantages and disadvantages between a research & review approach, vii conclusion: summarizing the contrasts between two types of writing.

What are Research and Review Papers? Research papers and review papers can both be academic documents, yet they differ in terms of purpose. A research paper is typically longer than a review paper and strives to explore an original thought or concept within its respective field of study. To write a successful research paper, it must present evidence that clearly demonstrates the researcher’s claims, which could include statistics as well as facts from reliable sources such as books, articles or published interviews.

A review paper on the other hand is shorter but more comprehensive in scope compared to a research paper; it focuses on summarizing relevant information about previously conducted studies pertaining to its respective field without introducing any new ideas into the mix. Its main aim is for readers to gain better understanding about what has been already discussed by experts on their topics of interest. Additionally, this type of document often contains critical evaluation methods so that readers have access to various perspectives when formulating their own conclusions.

- Research Paper : Longer format aimed at exploring original thought/concept.

- Review Paper : Shorter format with focus on summarizing previously discussed work.

Structure Differences Research papers and review papers may seem quite similar at a glance, but upon closer inspection there are several key differences in the structure of these two types of documents. Let’s dive into some of these distinctions to gain better insight into both paper forms.

- In comparison to research papers, which usually seek out new information or build on existing facts, reviews present an opinion-based discussion about published works.

- Research papers tend to be longer than reviews since they involve data gathering and analysis while reviews include only summaries and critique.

.Additionally, as research looks for solutions to problems it often contains recommendations that outline potential future directions whereas a review tends not to contain such advice due its summary nature. The language style used in each type is also distinct with research requiring more technical terms while reviews utilize everyday language making them easier for general readership. Finally, though references from primary sources are expected in both cases, the list associated with a review will typically be smaller given the summarizing format .

The differences between research and review papers can be quite complex. When writing either type of paper, there are several important distinctions to keep in mind.

- Research Papers

Research papers focus on the author’s original work, such as experiments or analysis of data sets. It typically involves collecting information from existing sources and analyzing it to provide insight into a specific problem. The results of this research should then be summarized, compared with previous studies related to the topic, and discussed thoroughly.

- Review Papers

It is true that when it comes to writing an academic paper, the language used can vary greatly depending on its type. Research papers and review papers are two distinct types of documents with their own unique features.

- Research Papers : These scholarly works require a more analytical approach in which the writer examines existing research and makes deductions from these findings. To create persuasive arguments for his or her ideas, the author must be adept at using jargon associated with their field as well as incorporating facts from credible sources. Furthermore, effective use of rhetorical devices such as appeals to logic should also be utilized.

- Review Papers : In comparison to research papers, review papers entail summarizing already published work instead of investigating new topics. As such, they typically employ simpler language than what would normally be seen in a research paper while including references directly related to its subject matter. The goal here is not only providing an objective summary but also providing insights into how different aspects are interconnected.

The world of research and academia is characterized by the use of different paper types. Each one serves its own unique purpose, so understanding them all can be immensely beneficial for any scholar or student. Research Papers offer a platform to dive deep into an issue, displaying knowledge on the subject while investigating further areas that require attention. While they may include personal observations and assumptions, most parts rely heavily on factual evidence gathered from established sources.

In contrast to this are Review Papers . These documents serve as compilations of existing literature in a certain field; including relevant books, articles and other publications put together in order to provide readers with an informed overview about the topic being discussed. As such, these papers tend not to focus too much on introducing new ideas but rather exploring already known theories more thoroughly.

Research & Review: Pros and Cons

When conducting academic research, there is a debate as to which approach yields the most comprehensive results – a Research or Review paper? While each has its own merits, it’s essential for scholars to identify the differences between these two types of papers. One key difference lies in their objectives; with research papers being focused on developing new knowledge from original sources whereas review articles are written to synthesize existing literature about a given topic. As such, when composing research work more time must be taken into investigating fresh material compared to that required for producing reviews. This can lead to drawbacks if the data collection process becomes overly lengthy or costly. An advantage associated with writing reviews is its improved accessibility since they often contain concise summaries of diverse topics rather than single experiments/studies conducted by one author as featured in typical research articles. It can also provide an efficient way for scientists studying similar subjects within different disciplines towards discovering previously unknown connections between them – helping accelerate progress in their field even further! Additionally, reviewing is beneficial for novice researchers trying their hand at making sense out of complex data.

In conclusion then while both approaches have distinct strengths and weaknesses related outcomes will depend heavily upon how well authors apply them suitably according relevant contexts. Experienced writers need only discern carefully what kind of article best meets their needs before taking any decision either way!

At its core, the contrast between a research paper and a review paper comes down to scope. A research paper is focused on original work while reviews are concerned with compiling existing evidence and summarizing it in an accessible format.

- Research Papers : Research papers provide new insights into a topic or field of study through fresh investigation. They involve gathering primary data (through interviews, experiments) or secondary sources like journal articles. Additionally, they tend to require extensive literature reviews that explore prior studies related to the author’s chosen area of inquiry.

- Review Papers: On the other hand, review papers take already published results as their starting point and aim to synthesize them by analyzing various aspects such as methodologies employed by different authors in similar fields of inquiry; assumptions made when designing studies; implications for future practice; emerging trends etc., offering readers comprehensive insight into current understanding about certain topics within limited spaces.

In conclusion, writing either type of paper requires rigorous analysis combined with creative thinking skills but at differing levels depending on whether one is researching from scratch or reviewing what has been done previously. While both types carry equal importance due to their distinct purposes in academia – providing raw knowledge versus neatly packaged summaries respectively – ultimately there can be no denying that each plays its own unique role towards advancing human thought overall!

English: The contrast between research and review papers is an important concept to understand when writing scholarly work. While both are forms of academic writings, they each bring a unique set of characteristics that need to be considered in order for the paper’s purpose to be effectively met. By understanding how research and review papers differ from one another, authors can better craft their pieces with insight into the nuances between them. As this article has illustrated, doing so will allow authors to produce higher-quality works that achieve their intended goals more successfully.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- ScientificWorldJournal

- v.2024; 2024

- PMC10807936

Writing a Scientific Review Article: Comprehensive Insights for Beginners

Ayodeji amobonye.

1 Department of Biotechnology and Food Science, Faculty of Applied Sciences, Durban University of Technology, P.O. Box 1334, KwaZulu-Natal, Durban 4000, South Africa

2 Writing Centre, Durban University of Technology, P.O. Box 1334 KwaZulu-Natal, Durban 4000, South Africa

Japareng Lalung

3 School of Industrial Technology, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Gelugor 11800, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia

Santhosh Pillai

Associated data.

The data and materials that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Review articles present comprehensive overview of relevant literature on specific themes and synthesise the studies related to these themes, with the aim of strengthening the foundation of knowledge and facilitating theory development. The significance of review articles in science is immeasurable as both students and researchers rely on these articles as the starting point for their research. Interestingly, many postgraduate students are expected to write review articles for journal publications as a way of demonstrating their ability to contribute to new knowledge in their respective fields. However, there is no comprehensive instructional framework to guide them on how to analyse and synthesise the literature in their niches into publishable review articles. The dearth of ample guidance or explicit training results in students having to learn all by themselves, usually by trial and error, which often leads to high rejection rates from publishing houses. Therefore, this article seeks to identify these challenges from a beginner's perspective and strives to plug the identified gaps and discrepancies. Thus, the purpose of this paper is to serve as a systematic guide for emerging scientists and to summarise the most important information on how to write and structure a publishable review article.

1. Introduction

Early scientists, spanning from the Ancient Egyptian civilization to the Scientific Revolution of the 16 th /17 th century, based their research on intuitions, personal observations, and personal insights. Thus, less time was spent on background reading as there was not much literature to refer to. This is well illustrated in the case of Sir Isaac Newton's apple tree and the theory of gravity, as well as Gregor Mendel's pea plants and the theory of inheritance. However, with the astronomical expansion in scientific knowledge and the emergence of the information age in the last century, new ideas are now being built on previously published works, thus the periodic need to appraise the huge amount of already published literature [ 1 ]. According to Birkle et al. [ 2 ], the Web of Science—an authoritative database of research publications and citations—covered more than 80 million scholarly materials. Hence, a critical review of prior and relevant literature is indispensable for any research endeavour as it provides the necessary framework needed for synthesising new knowledge and for highlighting new insights and perspectives [ 3 ].

Review papers are generally considered secondary research publications that sum up already existing works on a particular research topic or question and relate them to the current status of the topic. This makes review articles distinctly different from scientific research papers. While the primary aim of the latter is to develop new arguments by reporting original research, the former is focused on summarising and synthesising previous ideas, studies, and arguments, without adding new experimental contributions. Review articles basically describe the content and quality of knowledge that are currently available, with a special focus on the significance of the previous works. To this end, a review article cannot simply reiterate a subject matter, but it must contribute to the field of knowledge by synthesising available materials and offering a scholarly critique of theory [ 4 ]. Typically, these articles critically analyse both quantitative and qualitative studies by scrutinising experimental results, the discussion of the experimental data, and in some instances, previous review articles to propose new working theories. Thus, a review article is more than a mere exhaustive compilation of all that has been published on a topic; it must be a balanced, informative, perspective, and unbiased compendium of previous studies which may also include contrasting findings, inconsistencies, and conventional and current views on the subject [ 5 ].

Hence, the essence of a review article is measured by what is achieved, what is discovered, and how information is communicated to the reader [ 6 ]. According to Steward [ 7 ], a good literature review should be analytical, critical, comprehensive, selective, relevant, synthetic, and fully referenced. On the other hand, a review article is considered to be inadequate if it is lacking in focus or outcome, overgeneralised, opinionated, unbalanced, and uncritical [ 7 ]. Most review papers fail to meet these standards and thus can be viewed as mere summaries of previous works in a particular field of study. In one of the few studies that assessed the quality of review articles, none of the 50 papers that were analysed met the predefined criteria for a good review [ 8 ]. However, beginners must also realise that there is no bad writing in the true sense; there is only writing in evolution and under refinement. Literally, every piece of writing can be improved upon, right from the first draft until the final published manuscript. Hence, a paper can only be referred to as bad and unfixable when the author is not open to corrections or when the writer gives up on it.

According to Peat et al. [ 9 ], “everything is easy when you know how,” a maxim which applies to scientific writing in general and review writing in particular. In this regard, the authors emphasized that the writer should be open to learning and should also follow established rules instead of following a blind trial-and-error approach. In contrast to the popular belief that review articles should only be written by experienced scientists and researchers, recent trends have shown that many early-career scientists, especially postgraduate students, are currently expected to write review articles during the course of their studies. However, these scholars have little or no access to formal training on how to analyse and synthesise the research literature in their respective fields [ 10 ]. Consequently, students seeking guidance on how to write or improve their literature reviews are less likely to find published works on the subject, particularly in the science fields. Although various publications have dealt with the challenges of searching for literature, or writing literature reviews for dissertation/thesis purposes, there is little or no information on how to write a comprehensive review article for publication. In addition to the paucity of published information to guide the potential author, the lack of understanding of what constitutes a review paper compounds their challenges. Thus, the purpose of this paper is to serve as a guide for writing review papers for journal publishing. This work draws on the experience of the authors to assist early-career scientists/researchers in the “hard skill” of authoring review articles. Even though there is no single path to writing scientifically, or to writing reviews in particular, this paper attempts to simplify the process by looking at this subject from a beginner's perspective. Hence, this paper highlights the differences between the types of review articles in the sciences while also explaining the needs and purpose of writing review articles. Furthermore, it presents details on how to search for the literature as well as how to structure the manuscript to produce logical and coherent outputs. It is hoped that this work will ease prospective scientific writers into the challenging but rewarding art of writing review articles.

2. Benefits of Review Articles to the Author

Analysing literature gives an overview of the “WHs”: WHat has been reported in a particular field or topic, WHo the key writers are, WHat are the prevailing theories and hypotheses, WHat questions are being asked (and answered), and WHat methods and methodologies are appropriate and useful [ 11 ]. For new or aspiring researchers in a particular field, it can be quite challenging to get a comprehensive overview of their respective fields, especially the historical trends and what has been studied previously. As such, the importance of review articles to knowledge appraisal and contribution cannot be overemphasised, which is reflected in the constant demand for such articles in the research community. However, it is also important for the author, especially the first-time author, to recognise the importance of his/her investing time and effort into writing a quality review article.

Generally, literature reviews are undertaken for many reasons, mainly for publication and for dissertation purposes. The major purpose of literature reviews is to provide direction and information for the improvement of scientific knowledge. They also form a significant component in the research process and in academic assessment [ 12 ]. There may be, however, a thin line between a dissertation literature review and a published review article, given that with some modifications, a literature review can be transformed into a legitimate and publishable scholarly document. According to Gülpınar and Güçlü [ 6 ], the basic motivation for writing a review article is to make a comprehensive synthesis of the most appropriate literature on a specific research inquiry or topic. Thus, conducting a literature review assists in demonstrating the author's knowledge about a particular field of study, which may include but not be limited to its history, theories, key variables, vocabulary, phenomena, and methodologies [ 10 ]. Furthermore, publishing reviews is beneficial as it permits the researchers to examine different questions and, as a result, enhances the depth and diversity of their scientific reasoning [ 1 ]. In addition, writing review articles allows researchers to share insights with the scientific community while identifying knowledge gaps to be addressed in future research. The review writing process can also be a useful tool in training early-career scientists in leadership, coordination, project management, and other important soft skills necessary for success in the research world [ 13 ]. Another important reason for authoring reviews is that such publications have been observed to be remarkably influential, extending the reach of an author in multiple folds of what can be achieved by primary research papers [ 1 ]. The trend in science is for authors to receive more citations from their review articles than from their original research articles. According to Miranda and Garcia-Carpintero [ 14 ], review articles are, on average, three times more frequently cited than original research articles; they also asserted that a 20% increase in review authorship could result in a 40–80% increase in citations of the author. As a result, writing reviews can significantly impact a researcher's citation output and serve as a valuable channel to reach a wider scientific audience. In addition, the references cited in a review article also provide the reader with an opportunity to dig deeper into the topic of interest. Thus, review articles can serve as a valuable repository for consultation, increasing the visibility of the authors and resulting in more citations.

3. Types of Review Articles

The first step in writing a good literature review is to decide on the particular type of review to be written; hence, it is important to distinguish and understand the various types of review articles. Although scientific review articles have been classified according to various schemes, however, they are broadly categorised into narrative reviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses [ 15 ]. It was observed that more authors—as well as publishers—were leaning towards systematic reviews and meta-analysis while downplaying narrative reviews; however, the three serve different aims and should all be considered equally important in science [ 1 ]. Bibliometric reviews and patent reviews, which are closely related to meta-analysis, have also gained significant attention recently. However, from another angle, a review could also be of two types. In the first class, authors could deal with a widely studied topic where there is already an accumulated body of knowledge that requires analysis and synthesis [ 3 ]. At the other end of the spectrum, the authors may have to address an emerging issue that would benefit from exposure to potential theoretical foundations; hence, their contribution would arise from the fresh theoretical foundations proposed in developing a conceptual model [ 3 ].

3.1. Narrative Reviews

Narrative reviewers are mainly focused on providing clarification and critical analysis on a particular topic or body of literature through interpretative synthesis, creativity, and expert judgement. According to Green et al. [ 16 ], a narrative review can be in the form of editorials, commentaries, and narrative overviews. However, editorials and commentaries are usually expert opinions; hence, a beginner is more likely to write a narrative overview, which is more general and is also referred to as an unsystematic narrative review. Similarly, the literature review section of most dissertations and empirical papers is typically narrative in nature. Typically, narrative reviews combine results from studies that may have different methodologies to address different questions or to formulate a broad theoretical formulation [ 1 ]. They are largely integrative as strong focus is placed on the assimilation and synthesis of various aspects in the review, which may involve comparing and contrasting research findings or deriving structured implications [ 17 ]. In addition, they are also qualitative studies because they do not follow strict selection processes; hence, choosing publications is relatively more subjective and unsystematic [ 18 ]. However, despite their popularity, there are concerns about their inherent subjectivity. In many instances, when the supporting data for narrative reviews are examined more closely, the evaluations provided by the author(s) become quite questionable [ 19 ]. Nevertheless, if the goal of the author is to formulate a new theory that connects diverse strands of research, a narrative method is most appropriate.

3.2. Systematic Reviews

In contrast to narrative reviews, which are generally descriptive, systematic reviews employ a systematic approach to summarise evidence on research questions. Hence, systematic reviews make use of precise and rigorous criteria to identify, evaluate, and subsequently synthesise all relevant literature on a particular topic [ 12 , 20 ]. As a result, systematic reviews are more likely to inspire research ideas by identifying knowledge gaps or inconsistencies, thus helping the researcher to clearly define the research hypotheses or questions [ 21 ]. Furthermore, systematic reviews may serve as independent research projects in their own right, as they follow a defined methodology to search and combine reliable results to synthesise a new database that can be used for a variety of purposes [ 22 ]. Typically, the peculiarities of the individual reviewer, different search engines, and information databases used all ensure that no two searches will yield the same systematic results even if the searches are conducted simultaneously and under identical criteria [ 11 ]. Hence, attempts are made at standardising the exercise via specific methods that would limit bias and chance effects, prevent duplications, and provide more accurate results upon which conclusions and decisions can be made.

The most established of these methods is the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines which objectively defined statements, guidelines, reporting checklists, and flowcharts for undertaking systematic reviews as well as meta-analysis [ 23 ]. Though mainly designed for research in medical sciences, the PRISMA approach has gained wide acceptance in other fields of science and is based on eight fundamental propositions. These include the explicit definition of the review question, an unambiguous outline of the study protocol, an objective and exhaustive systematic review of reputable literature, and an unambiguous identification of included literature based on defined selection criteria [ 24 ]. Other considerations include an unbiased appraisal of the quality of the selected studies (literature), organic synthesis of the evidence of the study, preparation of the manuscript based on the reporting guidelines, and periodic update of the review as new data emerge [ 24 ]. Other methods such as PRISMA-P (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis Protocols), MOOSE (Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology), and ROSES (Reporting Standards for Systematic Evidence Syntheses) have since been developed for systematic reviews (and meta-analysis), with most of them being derived from PRISMA.

Consequently, systematic reviews—unlike narrative reviews—must contain a methodology section which in addition to all that was highlighted above must fully describe the precise criteria used in formulating the research question and setting the inclusion or exclusion criteria used in selecting/accessing the literature. Similarly, the criteria for evaluating the quality of the literature included in the review as well as for analysing, synthesising, and disseminating the findings must be fully described in the methodology section.

3.3. Meta-Analysis

Meta-analyses are considered as more specialised forms of systematic reviews. Generally, they combine the results of many studies that use similar or closely related methods to address the same question or share a common quantitative evaluation method [ 25 ]. However, meta-analyses are also a step higher than other systematic reviews as they are focused on numerical data and involve the use of statistics in evaluating different studies and synthesising new knowledge. The major advantage of this type of review is the increased statistical power leading to more reliable results for inferring modest associations and a more comprehensive understanding of the true impact of a research study [ 26 ]. Unlike in traditional systematic reviews, research topics covered in meta-analyses must be mature enough to allow the inclusion of sufficient homogeneous empirical research in terms of subjects, interventions, and outcomes [ 27 , 28 ].