Hypothesis vs. Prediction

What's the difference.

Hypothesis and prediction are both important components of the scientific method, but they serve different purposes. A hypothesis is a proposed explanation or statement that can be tested through experimentation or observation. It is based on prior knowledge, observations, or theories and is used to guide scientific research. On the other hand, a prediction is a specific statement about what will happen in a particular situation or experiment. It is often derived from a hypothesis and serves as a testable outcome that can be confirmed or refuted through data analysis. While a hypothesis provides a broader framework for scientific inquiry, a prediction is a more specific and measurable expectation of the results.

Further Detail

Introduction.

When it comes to scientific research and inquiry, two important concepts that often come into play are hypothesis and prediction. Both of these terms are used to make educated guesses or assumptions about the outcome of an experiment or study. While they share some similarities, they also have distinct attributes that set them apart. In this article, we will explore the characteristics of hypothesis and prediction, highlighting their differences and similarities.

A hypothesis is a proposed explanation or statement that can be tested through experimentation or observation. It is typically formulated based on existing knowledge, observations, or theories. A hypothesis is often used as a starting point for scientific research, as it provides a framework for investigation and helps guide the research process.

One of the key attributes of a hypothesis is that it is testable. This means that it can be subjected to empirical evidence and observations to determine its validity. A hypothesis should be specific and measurable, allowing researchers to design experiments or gather data to either support or refute the hypothesis.

Another important aspect of a hypothesis is that it is falsifiable. This means that it is possible to prove the hypothesis wrong through experimentation or observation. Falsifiability is crucial in scientific research, as it ensures that hypotheses can be objectively tested and evaluated.

Hypotheses can be classified into two main types: null hypotheses and alternative hypotheses. A null hypothesis states that there is no significant relationship or difference between variables, while an alternative hypothesis proposes the existence of a relationship or difference. These two types of hypotheses are often used in statistical analysis to draw conclusions from data.

In summary, a hypothesis is a testable and falsifiable statement that serves as a starting point for scientific research. It is specific, measurable, and can be either a null or alternative hypothesis.

While a hypothesis is a proposed explanation or statement, a prediction is a specific outcome or result that is anticipated based on existing knowledge or theories. Predictions are often made before conducting an experiment or study and serve as a way to anticipate the expected outcome.

Unlike a hypothesis, a prediction is not necessarily testable or falsifiable on its own. Instead, it is used to guide the research process and provide a basis for comparison with the actual results obtained from the experiment or study. Predictions can be based on previous research, theoretical models, or logical reasoning.

One of the key attributes of a prediction is that it is specific and precise. It should clearly state the expected outcome or result, leaving little room for ambiguity. This allows researchers to compare the prediction with the actual results and evaluate the accuracy of their anticipated outcome.

Predictions can also be used to generate hypotheses. By making a prediction and comparing it with the actual results, researchers can identify discrepancies or unexpected findings. These observations can then be used to formulate new hypotheses and guide further research.

In summary, a prediction is a specific anticipated outcome or result that is not necessarily testable or falsifiable on its own. It serves as a basis for comparison with the actual results obtained from an experiment or study and can be used to generate new hypotheses.

Similarities

While hypotheses and predictions have distinct attributes, they also share some similarities in the context of scientific research. Both hypotheses and predictions are based on existing knowledge, observations, or theories. They are both used to make educated guesses or assumptions about the outcome of an experiment or study.

Furthermore, both hypotheses and predictions play a crucial role in the scientific method. They provide a framework for research, guiding the design of experiments, data collection, and analysis. Both hypotheses and predictions are subject to evaluation and revision based on empirical evidence and observations.

Additionally, both hypotheses and predictions can be used to generate new knowledge and advance scientific understanding. By testing hypotheses and comparing predictions with actual results, researchers can gain insights into the relationships between variables, uncover new phenomena, or challenge existing theories.

Overall, while hypotheses and predictions have their own unique attributes, they are both integral components of scientific research and inquiry.

In conclusion, hypotheses and predictions are important concepts in scientific research. While a hypothesis is a testable and falsifiable statement that serves as a starting point for investigation, a prediction is a specific anticipated outcome or result that guides the research process. Hypotheses are specific, measurable, and can be either null or alternative, while predictions are precise and serve as a basis for comparison with actual results.

Despite their differences, hypotheses and predictions share similarities in terms of their reliance on existing knowledge, their role in the scientific method, and their potential to generate new knowledge. Both hypotheses and predictions contribute to the advancement of scientific understanding and play a crucial role in the research process.

By understanding the attributes of hypotheses and predictions, researchers can effectively formulate research questions, design experiments, and analyze data. These concepts are fundamental to the scientific method and are essential for the progress of scientific research and inquiry.

Comparisons may contain inaccurate information about people, places, or facts. Please report any issues.

- Key Differences

Know the Differences & Comparisons

Difference Between Hypothesis and Prediction

Due to insufficient knowledge, many misconstrue hypothesis for prediction, which is wrong, as these two are entirely different. Prediction is forecasting of future events, which is sometimes based on evidence or sometimes, on a person’s instinct or gut feeling. So take a glance at the article presented below, which elaborates the difference between hypothesis and prediction.

Content: Hypothesis Vs Prediction

Comparison chart, definition of hypothesis.

In simple terms, hypothesis means a sheer assumption which can be approved or disapproved. For the purpose of research, the hypothesis is defined as a predictive statement, which can be tested and verified using the scientific method. By testing the hypothesis, the researcher can make probability statements on the population parameter. The objective of the hypothesis is to find the solution to a given problem.

A hypothesis is a mere proposition which is put to the test to ascertain its validity. It states the relationship between an independent variable to some dependent variable. The characteristics of the hypothesis are described as under:

- It should be clear and precise.

- It should be stated simply.

- It must be specific.

- It should correlate variables.

- It should be consistent with most known facts.

- It should be capable of being tested.

- It must explain, what it claims to explain.

Definition of Prediction

A prediction is described as a statement which forecasts a future event, which may or may not be based on knowledge and experience, i.e. it can be a pure guess based on the instinct of a person. It is termed as an informed guess, when the prediction comes out from a person having ample subject knowledge and uses accurate data and logical reasoning, to make it.

Regression analysis is one of the statistical technique, which is used for making the prediction.

In many multinational corporations, futurists (predictors) are paid a good amount for making prediction relating to the possible events, opportunities, threats or risks. And to do so, the futurists, study all past and current events, to forecast future occurrences. Further, it has a great role to play in statistics also, to draw inferences about a population parameter.

Key Differences Between Hypothesis and Prediction

The difference between hypothesis and prediction can be drawn clearly on the following grounds:

- A propounded explanation for an observable occurrence, established on the basis of established facts, as an introduction to the further study, is known as the hypothesis. A statement, which tells or estimates something that will occur in future is known as the prediction.

- The hypothesis is nothing but a tentative supposition which can be tested by scientific methods. On the contrary, the prediction is a sort of declaration made in advance on what is expected to happen next, in the sequence of events.

- While the hypothesis is an intelligent guess, the prediction is a wild guess.

- A hypothesis is always supported by facts and evidence. As against this, predictions are based on knowledge and experience of the person making it, but that too not always.

- Hypothesis always have an explanation or reason, whereas prediction does not have any explanation.

- Hypothesis formulation takes a long time. Conversely, making predictions about a future happening does not take much time.

- Hypothesis defines a phenomenon, which may be a future or a past event. Unlike, prediction, which always anticipates about happening or non-happening of a certain event in future.

- The hypothesis states the relationship between independent variable and the dependent variable. On the other hand, prediction does not state any relationship between variables.

To sum up, the prediction is merely a conjecture to discern future, while a hypothesis is a proposition put forward for the explanation. The former, can be made by any person, no matter he/she has knowledge in the particular field. On the flip side, the hypothesis is made by the researcher to discover the answer to a certain question. Further, the hypothesis has to pass to various test, to become a theory.

You Might Also Like:

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Peterborough

Understanding Hypotheses and Predictions

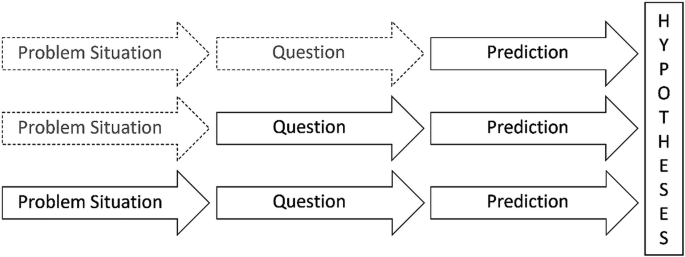

Hypotheses and predictions are different components of the scientific method. The scientific method is a systematic process that helps minimize bias in research and begins by developing good research questions.

Research Questions

Descriptive research questions are based on observations made in previous research or in passing. This type of research question often quantifies these observations. For example, while out bird watching, you notice that a certain species of sparrow made all its nests with the same material: grasses. A descriptive research question would be “On average, how much grass is used to build sparrow nests?”

Descriptive research questions lead to causal questions. This type of research question seeks to understand why we observe certain trends or patterns. If we return to our observation about sparrow nests, a causal question would be “Why are the nests of sparrows made with grasses rather than twigs?”

In simple terms, a hypothesis is the answer to your causal question. A hypothesis should be based on a strong rationale that is usually supported by background research. From the question about sparrow nests, you might hypothesize, “Sparrows use grasses in their nests rather than twigs because grasses are the more abundant material in their habitat.” This abundance hypothesis might be supported by your prior knowledge about the availability of nest building materials (i.e. grasses are more abundant than twigs).

On the other hand, a prediction is the outcome you would observe if your hypothesis were correct. Predictions are often written in the form of “if, and, then” statements, as in, “if my hypothesis is true, and I were to do this test, then this is what I will observe.” Following our sparrow example, you could predict that, “If sparrows use grass because it is more abundant, and I compare areas that have more twigs than grasses available, then, in those areas, nests should be made out of twigs.” A more refined prediction might alter the wording so as not to repeat the hypothesis verbatim: “If sparrows choose nesting materials based on their abundance, then when twigs are more abundant, sparrows will use those in their nests.”

As you can see, the terms hypothesis and prediction are different and distinct even though, sometimes, they are incorrectly used interchangeably.

Let us take a look at another example:

Causal Question: Why are there fewer asparagus beetles when asparagus is grown next to marigolds?

Hypothesis: Marigolds deter asparagus beetles.

Prediction: If marigolds deter asparagus beetles, and we grow asparagus next to marigolds, then we should find fewer asparagus beetles when asparagus plants are planted with marigolds.

A final note

It is exciting when the outcome of your study or experiment supports your hypothesis. However, it can be equally exciting if this does not happen. There are many reasons why you can have an unexpected result, and you need to think why this occurred. Maybe you had a potential problem with your methods, but on the flip side, maybe you have just discovered a new line of evidence that can be used to develop another experiment or study.

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Biology library

Course: biology library > unit 1, the scientific method.

- Controlled experiments

- The scientific method and experimental design

Introduction

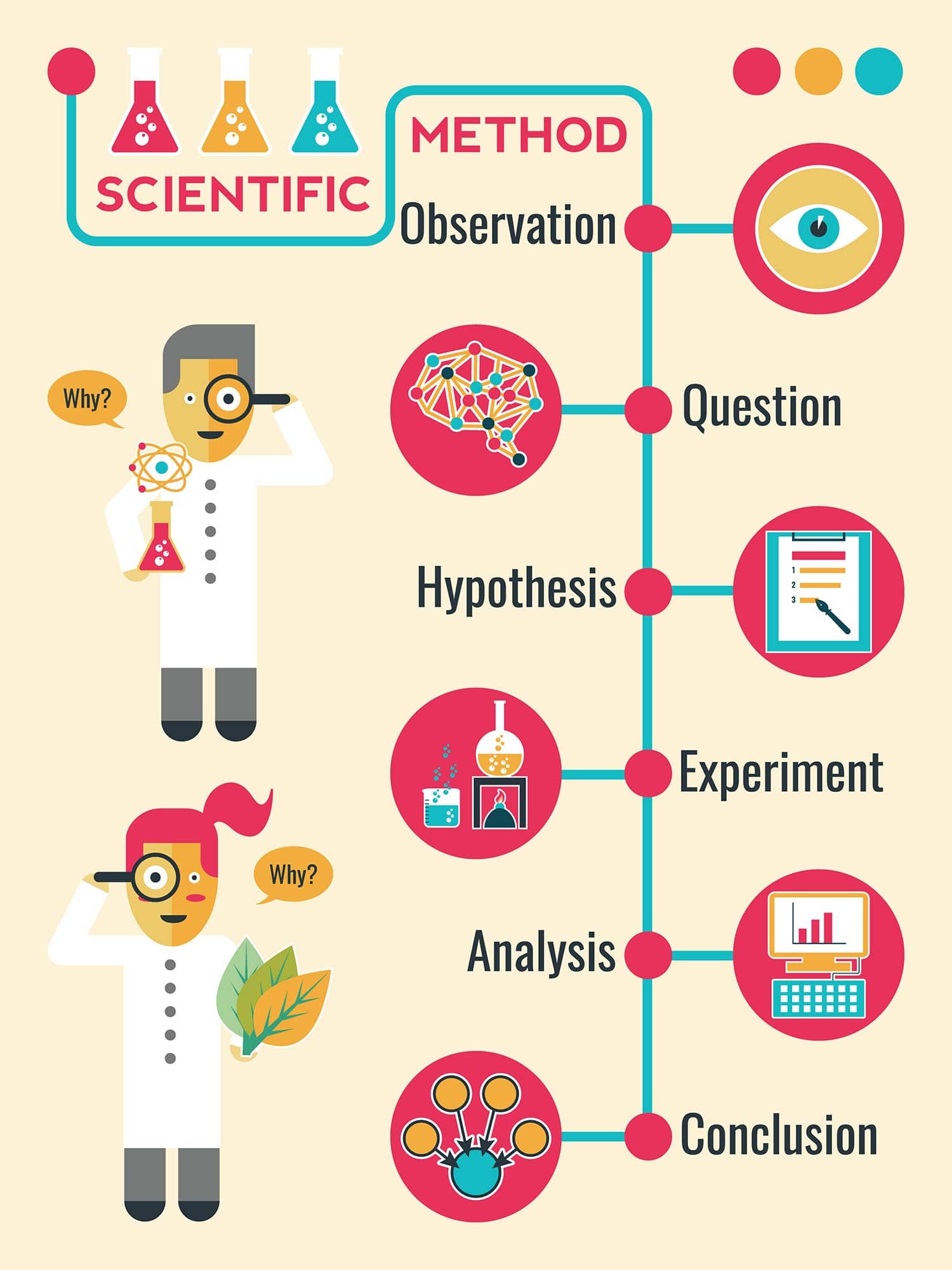

- Make an observation.

- Ask a question.

- Form a hypothesis , or testable explanation.

- Make a prediction based on the hypothesis.

- Test the prediction.

- Iterate: use the results to make new hypotheses or predictions.

Scientific method example: Failure to toast

1. make an observation..

- Observation: the toaster won't toast.

2. Ask a question.

- Question: Why won't my toaster toast?

3. Propose a hypothesis.

- Hypothesis: Maybe the outlet is broken.

4. Make predictions.

- Prediction: If I plug the toaster into a different outlet, then it will toast the bread.

5. Test the predictions.

- Test of prediction: Plug the toaster into a different outlet and try again.

- If the toaster does toast, then the hypothesis is supported—likely correct.

- If the toaster doesn't toast, then the hypothesis is not supported—likely wrong.

Logical possibility

Practical possibility, building a body of evidence, 6. iterate..

- Iteration time!

- If the hypothesis was supported, we might do additional tests to confirm it, or revise it to be more specific. For instance, we might investigate why the outlet is broken.

- If the hypothesis was not supported, we would come up with a new hypothesis. For instance, the next hypothesis might be that there's a broken wire in the toaster.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

What Are The Steps Of The Scientific Method?

Julia Simkus

Editor at Simply Psychology

BA (Hons) Psychology, Princeton University

Julia Simkus is a graduate of Princeton University with a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology. She is currently studying for a Master's Degree in Counseling for Mental Health and Wellness in September 2023. Julia's research has been published in peer reviewed journals.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Science is not just knowledge. It is also a method for obtaining knowledge. Scientific understanding is organized into theories.

The scientific method is a step-by-step process used by researchers and scientists to determine if there is a relationship between two or more variables. Psychologists use this method to conduct psychological research, gather data, process information, and describe behaviors.

It involves careful observation, asking questions, formulating hypotheses, experimental testing, and refining hypotheses based on experimental findings.

How it is Used

The scientific method can be applied broadly in science across many different fields, such as chemistry, physics, geology, and psychology. In a typical application of this process, a researcher will develop a hypothesis, test this hypothesis, and then modify the hypothesis based on the outcomes of the experiment.

The process is then repeated with the modified hypothesis until the results align with the observed phenomena. Detailed steps of the scientific method are described below.

Keep in mind that the scientific method does not have to follow this fixed sequence of steps; rather, these steps represent a set of general principles or guidelines.

7 Steps of the Scientific Method

Psychology uses an empirical approach.

Empiricism (founded by John Locke) states that the only source of knowledge comes through our senses – e.g., sight, hearing, touch, etc.

Empirical evidence does not rely on argument or belief. Thus, empiricism is the view that all knowledge is based on or may come from direct observation and experience.

The empiricist approach of gaining knowledge through experience quickly became the scientific approach and greatly influenced the development of physics and chemistry in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Step 1: Make an Observation (Theory Construction)

Every researcher starts at the very beginning. Before diving in and exploring something, one must first determine what they will study – it seems simple enough!

By making observations, researchers can establish an area of interest. Once this topic of study has been chosen, a researcher should review existing literature to gain insight into what has already been tested and determine what questions remain unanswered.

This assessment will provide helpful information about what has already been comprehended about the specific topic and what questions remain, and if one can go and answer them.

Specifically, a literature review might implicate examining a substantial amount of documented material from academic journals to books dating back decades. The most appropriate information gathered by the researcher will be shown in the introduction section or abstract of the published study results.

The background material and knowledge will help the researcher with the first significant step in conducting a psychology study, which is formulating a research question.

This is the inductive phase of the scientific process. Observations yield information that is used to formulate theories as explanations. A theory is a well-developed set of ideas that propose an explanation for observed phenomena.

Inductive reasoning moves from specific premises to a general conclusion. It starts with observations of phenomena in the natural world and derives a general law.

Step 2: Ask a Question

Once a researcher has made observations and conducted background research, the next step is to ask a scientific question. A scientific question must be defined, testable, and measurable.

A useful approach to develop a scientific question is: “What is the effect of…?” or “How does X affect Y?”

To answer an experimental question, a researcher must identify two variables: the independent and dependent variables.

The independent variable is the variable manipulated (the cause), and the dependent variable is the variable being measured (the effect).

An example of a research question could be, “Is handwriting or typing more effective for retaining information?” Answering the research question and proposing a relationship between the two variables is discussed in the next step.

Step 3: Form a Hypothesis (Make Predictions)

A hypothesis is an educated guess about the relationship between two or more variables. A hypothesis is an attempt to answer your research question based on prior observation and background research. Theories tend to be too complex to be tested all at once; instead, researchers create hypotheses to test specific aspects of a theory.

For example, a researcher might ask about the connection between sleep and educational performance. Do students who get less sleep perform worse on tests at school?

It is crucial to think about different questions one might have about a particular topic to formulate a reasonable hypothesis. It would help if one also considered how one could investigate the causalities.

It is important that the hypothesis is both testable against reality and falsifiable. This means that it can be tested through an experiment and can be proven wrong.

The falsification principle, proposed by Karl Popper , is a way of demarcating science from non-science. It suggests that for a theory to be considered scientific, it must be able to be tested and conceivably proven false.

To test a hypothesis, we first assume that there is no difference between the populations from which the samples were taken. This is known as the null hypothesis and predicts that the independent variable will not influence the dependent variable.

Examples of “if…then…” Hypotheses:

- If one gets less than 6 hours of sleep, then one will do worse on tests than if one obtains more rest.

- If one drinks lots of water before going to bed, one will have to use the bathroom often at night.

- If one practices exercising and lighting weights, then one’s body will begin to build muscle.

The research hypothesis is often called the alternative hypothesis and predicts what change(s) will occur in the dependent variable when the independent variable is manipulated.

It states that the results are not due to chance and that they are significant in terms of supporting the theory being investigated.

Although one could state and write a scientific hypothesis in many ways, hypotheses are usually built like “if…then…” statements.

Step 4: Run an Experiment (Gather Data)

The next step in the scientific method is to test your hypothesis and collect data. A researcher will design an experiment to test the hypothesis and gather data that will either support or refute the hypothesis.

The exact research methods used to examine a hypothesis depend on what is being studied. A psychologist might utilize two primary forms of research, experimental research, and descriptive research.

The scientific method is objective in that researchers do not let preconceived ideas or biases influence the collection of data and is systematic in that experiments are conducted in a logical way.

Experimental Research

Experimental research is used to investigate cause-and-effect associations between two or more variables. This type of research systematically controls an independent variable and measures its effect on a specified dependent variable.

Experimental research involves manipulating an independent variable and measuring the effect(s) on the dependent variable. Repeating the experiment multiple times is important to confirm that your results are accurate and consistent.

One of the significant advantages of this method is that it permits researchers to determine if changes in one variable cause shifts in each other.

While experiments in psychology typically have many moving parts (and can be relatively complex), an easy investigation is rather fundamental. Still, it does allow researchers to specify cause-and-effect associations between variables.

Most simple experiments use a control group, which involves those who do not receive the treatment, and an experimental group, which involves those who do receive the treatment.

An example of experimental research would be when a pharmaceutical company wants to test a new drug. They give one group a placebo (control group) and the other the actual pill (experimental group).

Descriptive Research

Descriptive research is generally used when it is challenging or even impossible to control the variables in question. Examples of descriptive analysis include naturalistic observation, case studies , and correlation studies .

One example of descriptive research includes phone surveys that marketers often use. While they typically do not allow researchers to identify cause and effect, correlational studies are quite common in psychology research. They make it possible to spot associations between distinct variables and measure the solidity of those relationships.

Step 5: Analyze the Data and Draw Conclusions

Once a researcher has designed and done the investigation and collected sufficient data, it is time to inspect this gathered information and judge what has been found. Researchers can summarize the data, interpret the results, and draw conclusions based on this evidence using analyses and statistics.

Upon completion of the experiment, you can collect your measurements and analyze the data using statistics. Based on the outcomes, you will either reject or confirm your hypothesis.

Analyze the Data

So, how does a researcher determine what the results of their study mean? Statistical analysis can either support or refute a researcher’s hypothesis and can also be used to determine if the conclusions are statistically significant.

When outcomes are said to be “statistically significant,” it is improbable that these results are due to luck or chance. Based on these observations, investigators must then determine what the results mean.

An experiment will support a hypothesis in some circumstances, but sometimes it fails to be truthful in other cases.

What occurs if the developments of a psychology investigation do not endorse the researcher’s hypothesis? It does mean that the study was worthless. Simply because the findings fail to defend the researcher’s hypothesis does not mean that the examination is not helpful or instructive.

This kind of research plays a vital role in supporting scientists in developing unexplored questions and hypotheses to investigate in the future. After decisions have been made, the next step is to communicate the results with the rest of the scientific community.

This is an integral part of the process because it contributes to the general knowledge base and can assist other scientists in finding new research routes to explore.

If the hypothesis is not supported, a researcher should acknowledge the experiment’s results, formulate a new hypothesis, and develop a new experiment.

We must avoid any reference to results proving a theory as this implies 100% certainty, and there is always a chance that evidence may exist that could refute a theory.

Draw Conclusions and Interpret the Data

When the empirical observations disagree with the hypothesis, a number of possibilities must be considered. It might be that the theory is incorrect, in which case it needs altering, so it fully explains the data.

Alternatively, it might be that the hypothesis was poorly derived from the original theory, in which case the scientists were expecting the wrong thing to happen.

It might also be that the research was poorly conducted, or used an inappropriate method, or there were factors in play that the researchers did not consider. This will begin the process of the scientific method again.

If the hypothesis is supported, the researcher can find more evidence to support their hypothesis or look for counter-evidence to strengthen their hypothesis further.

In either scenario, the researcher should share their results with the greater scientific community.

Step 6: Share Your Results

One of the final stages of the research cycle involves the publication of the research. Once the report is written, the researcher(s) may submit the work for publication in an appropriate journal.

Usually, this is done by writing up a study description and publishing the article in a professional or academic journal. The studies and conclusions of psychological work can be seen in peer-reviewed journals such as Developmental Psychology , Psychological Bulletin, the Journal of Social Psychology, and numerous others.

Scientists should report their findings by writing up a description of their study and any subsequent findings. This enables other researchers to build upon the present research or replicate the results.

As outlined by the American Psychological Association (APA), there is a typical structure of a journal article that follows a specified format. In these articles, researchers:

- Supply a brief narrative and background on previous research

- Give their hypothesis

- Specify who participated in the study and how they were chosen

- Provide operational definitions for each variable

- Explain the measures and methods used to collect data

- Describe how the data collected was interpreted

- Discuss what the outcomes mean

A detailed record of psychological studies and all scientific studies is vital to clearly explain the steps and procedures used throughout the study. So that other researchers can try this experiment too and replicate the results.

The editorial process utilized by academic and professional journals guarantees that each submitted article undergoes a thorough peer review to help assure that the study is scientifically sound. Once published, the investigation becomes another piece of the current puzzle of our knowledge “base” on that subject.

This last step is important because all results, whether they supported or did not support the hypothesis, can contribute to the scientific community. Publication of empirical observations leads to more ideas that are tested against the real world, and so on. In this sense, the scientific process is circular.

The editorial process utilized by academic and professional journals guarantees that each submitted article undergoes a thorough peer review to help assure that the study is scientifically sound.

Once published, the investigation becomes another piece of the current puzzle of our knowledge “base” on that subject.

By replicating studies, psychologists can reduce errors, validate theories, and gain a stronger understanding of a particular topic.

Step 7: Repeat the Scientific Method (Iteration)

Now, if one’s hypothesis turns out to be accurate, find more evidence or find counter-evidence. If one’s hypothesis is false, create a new hypothesis or try again.

One may wish to revise their first hypothesis to make a more niche experiment to design or a different specific question to test.

The amazingness of the scientific method is that it is a comprehensive and straightforward process that scientists, and everyone, can utilize over and over again.

So, draw conclusions and repeat because the scientific method is never-ending, and no result is ever considered perfect.

The scientific method is a process of:

- Making an observation.

- Forming a hypothesis.

- Making a prediction.

- Experimenting to test the hypothesis.

The procedure of repeating the scientific method is crucial to science and all fields of human knowledge.

Further Information

- Karl Popper – Falsification

- Thomas – Kuhn Paradigm Shift

- Positivism in Sociology: Definition, Theory & Examples

- Is Psychology a Science?

- Psychology as a Science (PDF)

List the 6 steps of the scientific methods in order

- Make an observation (theory construction)

- Ask a question. A scientific question must be defined, testable, and measurable.

- Form a hypothesis (make predictions)

- Run an experiment to test the hypothesis (gather data)

- Analyze the data and draw conclusions

- Share your results so that other researchers can make new hypotheses

What is the first step of the scientific method?

The first step of the scientific method is making an observation. This involves noticing and describing a phenomenon or group of phenomena that one finds interesting and wishes to explain.

Observations can occur in a natural setting or within the confines of a laboratory. The key point is that the observation provides the initial question or problem that the rest of the scientific method seeks to answer or solve.

What is the scientific method?

The scientific method is a step-by-step process that investigators can follow to determine if there is a causal connection between two or more variables.

Psychologists and other scientists regularly suggest motivations for human behavior. On a more casual level, people judge other people’s intentions, incentives, and actions daily.

While our standard assessments of human behavior are subjective and anecdotal, researchers use the scientific method to study psychology objectively and systematically.

All utilize a scientific method to study distinct aspects of people’s thinking and behavior. This process allows scientists to analyze and understand various psychological phenomena, but it also provides investigators and others a way to disseminate and debate the results of their studies.

The outcomes of these studies are often noted in popular media, which leads numerous to think about how or why researchers came to the findings they did.

Why Use the Six Steps of the Scientific Method

The goal of scientists is to understand better the world that surrounds us. Scientific research is the most critical tool for navigating and learning about our complex world.

Without it, we would be compelled to rely solely on intuition, other people’s power, and luck. We can eliminate our preconceived concepts and superstitions through methodical scientific research and gain an objective sense of ourselves and our world.

All psychological studies aim to explain, predict, and even control or impact mental behaviors or processes. So, psychologists use and repeat the scientific method (and its six steps) to perform and record essential psychological research.

So, psychologists focus on understanding behavior and the cognitive (mental) and physiological (body) processes underlying behavior.

In the real world, people use to understand the behavior of others, such as intuition and personal experience. The hallmark of scientific research is evidence to support a claim.

Scientific knowledge is empirical, meaning it is grounded in objective, tangible evidence that can be observed repeatedly, regardless of who is watching.

The scientific method is crucial because it minimizes the impact of bias or prejudice on the experimenter. Regardless of how hard one tries, even the best-intentioned scientists can’t escape discrimination. can’t

It stems from personal opinions and cultural beliefs, meaning any mortal filters data based on one’s experience. Sadly, this “filtering” process can cause a scientist to favor one outcome over another.

For an everyday person trying to solve a minor issue at home or work, succumbing to these biases is not such a big deal; in fact, most times, it is important.

But in the scientific community, where results must be inspected and reproduced, bias or discrimination must be avoided.

When to Use the Six Steps of the Scientific Method ?

One can use the scientific method anytime, anywhere! From the smallest conundrum to solving global problems, it is a process that can be applied to any science and any investigation.

Even if you are not considered a “scientist,” you will be surprised to know that people of all disciplines use it for all kinds of dilemmas.

Try to catch yourself next time you come by a question and see how you subconsciously or consciously use the scientific method.

- ABBREVIATIONS

- BIOGRAPHIES

- CALCULATORS

- CONVERSIONS

- DEFINITIONS

Grammar Tips & Articles »

Hypothesis vs. prediction, go to grammar.com to read about hypothesis vs. prediction and their differences. relax and enjoy.

Email Print

Have a discussion about this article with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe. If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

You need to be logged in to favorite .

Create a new account.

Your name: * Required

Your email address: * Required

Pick a user name: * Required

Username: * Required

Password: * Required

Forgot your password? Retrieve it

Use the citation below to add this article to your bibliography:

Style: MLA Chicago APA

"Hypothesis vs. Prediction." Grammar.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2024. Web. 21 Apr. 2024. < https://www.grammar.com/hypothesis_vs._prediction >.

The Web's Largest Resource for

Grammar & spelling, a member of the stands4 network, free, no signup required :, add to chrome.

Two clicks install »

Add to Firefox

Browse grammar.com.

Free Writing Tool :

Instant grammar checker.

Improve your grammar, vocabulary, and writing -- and it's FREE !

Try it now »

Are you a grammar master?

Identify the sentence with correct use of the future perfect tense:.

Improve your writing now :

Download grammar ebooks.

It’s now more important than ever to develop a powerful writing style. After all, most communication takes place in reports, emails, and instant messages.

- Understanding the Parts of Speech

- Common Grammatical Mistakes

- Developing a Powerful Writing Style

- Rules on Punctuation

- The Top 25 Grammatical Mistakes

- The Awful Like Word

- Build Your Vocabulary

More eBooks »

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to footer

Science Struck

What’s the Real Difference Between Hypothesis and Prediction

Both hypothesis and prediction fall in the realm of guesswork, but with different assumptions. This Buzzle write-up below will elaborate on the differences between hypothesis and prediction.

Like it? Share it!

“There is no justifiable prediction about how the hypothesis will hold up in the future; its degree of corroboration simply is a historical statement describing how severely the hypothesis has been tested in the past.” ― Robert Nozick, American author, professor, and philosopher

A lot of people tend to think that a hypothesis is the same as prediction, but this is not true. They are entirely different terms, though they can be manifested within the same example. They are both entities that stem from statistics, and are used in a variety of applications like finance, mathematics, science (widely), sports, psychology, etc. A hypothesis may be a prediction, but the reverse may not be true.

Also, a prediction may or may not agree with the hypothesis. Confused? Don’t worry, read the hypothesis vs. prediction comparison, provided below with examples, to clear your doubts regarding both these entities.

- A hypothesis is a kind of guess or proposition regarding a situation.

- It can be called a kind of intelligent guess or prediction, and it needs to be proved using different methods.

- Formulating a hypothesis is an important step in experimental design, for it helps to predict things that might take place in the course of research.

- The strength of the statement is based on how effectively it is proved while conducting experiments.

- It is usually written in the ‘If-then-because’ format.

- For example, ‘ If Susan’s mood depends on the weather, then she will be happy today, because it is bright and sunny outside. ‘. Here, Susan’s mood is the dependent variable, and the weather is the independent variable. Thus, a hypothesis helps establish a relationship.

- A prediction is also a type of guess, in fact, it is a guesswork in the true sense of the word.

- It is not an educated guess, like a hypothesis, i.e., it is based on established facts.

- While making a prediction for various applications, you have to take into account all the current observations.

- It can be testable, but just once. This goes to prove that the strength of the statement is based on whether the predicted event occurs or not.

- It is harder to define, and it contains many variations, which is why, probably, it is confused to be a fictional guess or forecast.

- For example, He is studying very hard, he might score an A . Here, we are predicting that since the student is working hard, he might score good marks. It is based on an observation and does not establish any relationship.

Factors of Differentiation

♦ Consider a statement, ‘If I add some chili powder, the pasta may become spicy’. This is a hypothesis, and a testable statement. You can carry on adding 1 pinch of chili powder, or a spoon, or two spoons, and so on. The dish may become spicier or pungent, or there may be no reaction at all. The sum and substance is that, the amount of chili powder is the independent variable here, and the pasta dish is the dependent variable, which is expected to change with the addition of chili powder. This statement thus establishes and analyzes the relationship between both variables, and you will get a variety of results when the test is performed multiple times. Your hypothesis may even be opposed tomorrow.

♦ Consider the statement, ‘Robert has longer legs, he may run faster’. This is just a prediction. You may have read somewhere that people with long legs tend to run faster. It may or may not be true. What is important here is ‘Robert’. You are talking only of Robert’s legs, so you will test if he runs faster. If he does, your prediction is true, if he doesn’t, your prediction is false. No more testing.

♦ Consider a statement, ‘If you eat chocolates, you may get acne’. This is a simple hypothesis, based on facts, yet necessary to be proven. It can be tested on a number of people. It may be true, it may be false. The fact is, it defines a relationship between chocolates and acne. The relationship can be analyzed and the results can be recorded. Tomorrow, someone might come up with an alternative hypothesis that chocolate does not cause acne. This will need to be tested again, and so on. A hypothesis is thus, something that you think happens due to a reason.

♦ Consider a statement, ‘The sky is overcast, it may rain today’. A simple guess, based on the fact that it generally rains if the sky is overcast. It may not even be testable, i.e., the sky can be overcast now and clear the next minute. If it does rain, you have predicted correctly. If it does not, you are wrong. No further analysis or questions.

Both hypothesis and prediction need to be effectively structured so that further analysis of the problem statement is easier. Remember that, the key difference between the two is the procedure of proving the statements. Also, you cannot state one is better than the other, this depends entirely on the application in hand.

Get Updates Right to Your Inbox

Privacy overview.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write a Great Hypothesis

Hypothesis Definition, Format, Examples, and Tips

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Verywell / Alex Dos Diaz

- The Scientific Method

Hypothesis Format

Falsifiability of a hypothesis.

- Operationalization

Hypothesis Types

Hypotheses examples.

- Collecting Data

A hypothesis is a tentative statement about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a specific, testable prediction about what you expect to happen in a study. It is a preliminary answer to your question that helps guide the research process.

Consider a study designed to examine the relationship between sleep deprivation and test performance. The hypothesis might be: "This study is designed to assess the hypothesis that sleep-deprived people will perform worse on a test than individuals who are not sleep-deprived."

At a Glance

A hypothesis is crucial to scientific research because it offers a clear direction for what the researchers are looking to find. This allows them to design experiments to test their predictions and add to our scientific knowledge about the world. This article explores how a hypothesis is used in psychology research, how to write a good hypothesis, and the different types of hypotheses you might use.

The Hypothesis in the Scientific Method

In the scientific method , whether it involves research in psychology, biology, or some other area, a hypothesis represents what the researchers think will happen in an experiment. The scientific method involves the following steps:

- Forming a question

- Performing background research

- Creating a hypothesis

- Designing an experiment

- Collecting data

- Analyzing the results

- Drawing conclusions

- Communicating the results

The hypothesis is a prediction, but it involves more than a guess. Most of the time, the hypothesis begins with a question which is then explored through background research. At this point, researchers then begin to develop a testable hypothesis.

Unless you are creating an exploratory study, your hypothesis should always explain what you expect to happen.

In a study exploring the effects of a particular drug, the hypothesis might be that researchers expect the drug to have some type of effect on the symptoms of a specific illness. In psychology, the hypothesis might focus on how a certain aspect of the environment might influence a particular behavior.

Remember, a hypothesis does not have to be correct. While the hypothesis predicts what the researchers expect to see, the goal of the research is to determine whether this guess is right or wrong. When conducting an experiment, researchers might explore numerous factors to determine which ones might contribute to the ultimate outcome.

In many cases, researchers may find that the results of an experiment do not support the original hypothesis. When writing up these results, the researchers might suggest other options that should be explored in future studies.

In many cases, researchers might draw a hypothesis from a specific theory or build on previous research. For example, prior research has shown that stress can impact the immune system. So a researcher might hypothesize: "People with high-stress levels will be more likely to contract a common cold after being exposed to the virus than people who have low-stress levels."

In other instances, researchers might look at commonly held beliefs or folk wisdom. "Birds of a feather flock together" is one example of folk adage that a psychologist might try to investigate. The researcher might pose a specific hypothesis that "People tend to select romantic partners who are similar to them in interests and educational level."

Elements of a Good Hypothesis

So how do you write a good hypothesis? When trying to come up with a hypothesis for your research or experiments, ask yourself the following questions:

- Is your hypothesis based on your research on a topic?

- Can your hypothesis be tested?

- Does your hypothesis include independent and dependent variables?

Before you come up with a specific hypothesis, spend some time doing background research. Once you have completed a literature review, start thinking about potential questions you still have. Pay attention to the discussion section in the journal articles you read . Many authors will suggest questions that still need to be explored.

How to Formulate a Good Hypothesis

To form a hypothesis, you should take these steps:

- Collect as many observations about a topic or problem as you can.

- Evaluate these observations and look for possible causes of the problem.

- Create a list of possible explanations that you might want to explore.

- After you have developed some possible hypotheses, think of ways that you could confirm or disprove each hypothesis through experimentation. This is known as falsifiability.

In the scientific method , falsifiability is an important part of any valid hypothesis. In order to test a claim scientifically, it must be possible that the claim could be proven false.

Students sometimes confuse the idea of falsifiability with the idea that it means that something is false, which is not the case. What falsifiability means is that if something was false, then it is possible to demonstrate that it is false.

One of the hallmarks of pseudoscience is that it makes claims that cannot be refuted or proven false.

The Importance of Operational Definitions

A variable is a factor or element that can be changed and manipulated in ways that are observable and measurable. However, the researcher must also define how the variable will be manipulated and measured in the study.

Operational definitions are specific definitions for all relevant factors in a study. This process helps make vague or ambiguous concepts detailed and measurable.

For example, a researcher might operationally define the variable " test anxiety " as the results of a self-report measure of anxiety experienced during an exam. A "study habits" variable might be defined by the amount of studying that actually occurs as measured by time.

These precise descriptions are important because many things can be measured in various ways. Clearly defining these variables and how they are measured helps ensure that other researchers can replicate your results.

Replicability

One of the basic principles of any type of scientific research is that the results must be replicable.

Replication means repeating an experiment in the same way to produce the same results. By clearly detailing the specifics of how the variables were measured and manipulated, other researchers can better understand the results and repeat the study if needed.

Some variables are more difficult than others to define. For example, how would you operationally define a variable such as aggression ? For obvious ethical reasons, researchers cannot create a situation in which a person behaves aggressively toward others.

To measure this variable, the researcher must devise a measurement that assesses aggressive behavior without harming others. The researcher might utilize a simulated task to measure aggressiveness in this situation.

Hypothesis Checklist

- Does your hypothesis focus on something that you can actually test?

- Does your hypothesis include both an independent and dependent variable?

- Can you manipulate the variables?

- Can your hypothesis be tested without violating ethical standards?

The hypothesis you use will depend on what you are investigating and hoping to find. Some of the main types of hypotheses that you might use include:

- Simple hypothesis : This type of hypothesis suggests there is a relationship between one independent variable and one dependent variable.

- Complex hypothesis : This type suggests a relationship between three or more variables, such as two independent and dependent variables.

- Null hypothesis : This hypothesis suggests no relationship exists between two or more variables.

- Alternative hypothesis : This hypothesis states the opposite of the null hypothesis.

- Statistical hypothesis : This hypothesis uses statistical analysis to evaluate a representative population sample and then generalizes the findings to the larger group.

- Logical hypothesis : This hypothesis assumes a relationship between variables without collecting data or evidence.

A hypothesis often follows a basic format of "If {this happens} then {this will happen}." One way to structure your hypothesis is to describe what will happen to the dependent variable if you change the independent variable .

The basic format might be: "If {these changes are made to a certain independent variable}, then we will observe {a change in a specific dependent variable}."

A few examples of simple hypotheses:

- "Students who eat breakfast will perform better on a math exam than students who do not eat breakfast."

- "Students who experience test anxiety before an English exam will get lower scores than students who do not experience test anxiety."

- "Motorists who talk on the phone while driving will be more likely to make errors on a driving course than those who do not talk on the phone."

- "Children who receive a new reading intervention will have higher reading scores than students who do not receive the intervention."

Examples of a complex hypothesis include:

- "People with high-sugar diets and sedentary activity levels are more likely to develop depression."

- "Younger people who are regularly exposed to green, outdoor areas have better subjective well-being than older adults who have limited exposure to green spaces."

Examples of a null hypothesis include:

- "There is no difference in anxiety levels between people who take St. John's wort supplements and those who do not."

- "There is no difference in scores on a memory recall task between children and adults."

- "There is no difference in aggression levels between children who play first-person shooter games and those who do not."

Examples of an alternative hypothesis:

- "People who take St. John's wort supplements will have less anxiety than those who do not."

- "Adults will perform better on a memory task than children."

- "Children who play first-person shooter games will show higher levels of aggression than children who do not."

Collecting Data on Your Hypothesis

Once a researcher has formed a testable hypothesis, the next step is to select a research design and start collecting data. The research method depends largely on exactly what they are studying. There are two basic types of research methods: descriptive research and experimental research.

Descriptive Research Methods

Descriptive research such as case studies , naturalistic observations , and surveys are often used when conducting an experiment is difficult or impossible. These methods are best used to describe different aspects of a behavior or psychological phenomenon.

Once a researcher has collected data using descriptive methods, a correlational study can examine how the variables are related. This research method might be used to investigate a hypothesis that is difficult to test experimentally.

Experimental Research Methods

Experimental methods are used to demonstrate causal relationships between variables. In an experiment, the researcher systematically manipulates a variable of interest (known as the independent variable) and measures the effect on another variable (known as the dependent variable).

Unlike correlational studies, which can only be used to determine if there is a relationship between two variables, experimental methods can be used to determine the actual nature of the relationship—whether changes in one variable actually cause another to change.

The hypothesis is a critical part of any scientific exploration. It represents what researchers expect to find in a study or experiment. In situations where the hypothesis is unsupported by the research, the research still has value. Such research helps us better understand how different aspects of the natural world relate to one another. It also helps us develop new hypotheses that can then be tested in the future.

Thompson WH, Skau S. On the scope of scientific hypotheses . R Soc Open Sci . 2023;10(8):230607. doi:10.1098/rsos.230607

Taran S, Adhikari NKJ, Fan E. Falsifiability in medicine: what clinicians can learn from Karl Popper [published correction appears in Intensive Care Med. 2021 Jun 17;:]. Intensive Care Med . 2021;47(9):1054-1056. doi:10.1007/s00134-021-06432-z

Eyler AA. Research Methods for Public Health . 1st ed. Springer Publishing Company; 2020. doi:10.1891/9780826182067.0004

Nosek BA, Errington TM. What is replication ? PLoS Biol . 2020;18(3):e3000691. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000691

Aggarwal R, Ranganathan P. Study designs: Part 2 - Descriptive studies . Perspect Clin Res . 2019;10(1):34-36. doi:10.4103/picr.PICR_154_18

Nevid J. Psychology: Concepts and Applications. Wadworth, 2013.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Home » Language » English Language » Words and Meanings » What is the Difference Between Hypothesis and Prediction

What is the Difference Between Hypothesis and Prediction

The main difference between hypothesis and prediction is that the hypothesis proposes an explanation to something which has already happened whereas the prediction proposes something that might happen in the future.

Hypothesis and prediction are two significant concepts that give possible explanations to several occurrences or phenomena. As a result, one may be able to draw conclusions that assist in formulating new theories , which can affect the future advancements in the human civilizations. Thus, both these terms are common in the field of science, research and logic. In addition, to make a prediction, one should need evidence or observation whereas one can formulate a hypothesis based on limited evidence .

Key Areas Covered

1. What is a Hypothesis – Definition, Features 2. What is a Prediction – Definition, Features 3. What is the Relationship Between Hypothesis and Prediction – Outline of Common Features 4. What is the Difference Between Hypothesis and Prediction – Comparison of Key Differences

Hypothesis, Logic, Prediction, Theories, Science

What is a Hypothesis

By definition, a hypothesis refers to a supposition or a proposed explanation made on the basis of limited evidence as a starting point for further investigation. In brief, a hypothesis is a proposed explanation for a phenomenon. Nevertheless, this is based on limited evidence, facts or information one has based on the underlying causes of the problem. However, it can be further tested by experimentation. Therefore, this is yet to be proven as correct.

This term hypothesis is, thus, used often in the field of science and research than in general usage. In science, it is termed as a scientific hypothesis. However, a scientific hypothesis has to be tested by a scientific method. Moreover, scientists usually base scientific hypotheses on previous observations which cannot be explained by the existing scientific theories.

Figure 01: A Hypothesis on Colonial Flagellate

In research studies, a hypothesis is based on independent and dependent variables. This is known as a ‘working hypothesis’, and it is provisionally accepted as a basis for further research, and often serves as a conceptual framework in qualitative research. As a result, based on the gathered facts in research, the hypothesis tends to create links or connections between the different variables. Thus, it will work as a source for a more concrete scientific explanation.

Hence, one can formulate a theory based on the hypothesis to lead on the investigation to the problem. A strong hypothesis can create effective predictions based on reasoning. As a result, a hypothesis can predict the outcome of an experiment in a laboratory or the observation of a natural phenomenon. Hence, a hypothesis is known as an ‘educated guess’.

What is a Prediction

A prediction can be defined as a thing predicted or a forecast. Hence, a prediction is a statement about something that might happen in the future. Thus, one can guess as to what might happen based on the existing evidence or observations.

In the general context, although it is difficult to predict the uncertain future, one can draw conclusions as to what might happen in the future based on the observations of the present. This will assist in avoiding negative consequences in the future when there are dangerous occurrences in the present.

Moreover, there is a link between hypothesis and prediction. A strong hypothesis will enable possible predictions. This link between a hypothesis and a prediction can be clearly observed in the field of science.

Figure 2: Weather Predictions

Hence, in scientific and research studies, a prediction is a specific design that can be used to test one’s hypothesis. Thus, the prediction is the outcome one can observe if their hypothesis were supported with experiment. Moreover, predictions are often written in the form of “if, then” statements; for example, “if my hypothesis is true, then this is what I will observe.”

Relationship Between Hypothesis and Prediction

- Based on a hypothesis, one can create a prediction

- Also, a hypothesis will enable predictions through the act of deductive reasoning.

- Furthermore, the prediction is the outcome that can be observed if the hypothesis were supported proven by the experiment.

Difference Between Hypothesis and Prediction

Hypothesis refers to the supposition or proposed explanation made on the basis of limited evidence, as a starting point for further investigation. On the other hand, prediction refers to a thing that is predicted or a forecast of something. Thus, this explains the main difference between hypothesis and prediction.

Interpretation

Hypothesis will lead to explaining why something happened while prediction will lead to interpreting what might happen according to the present observations. This is a major difference between hypothesis and prediction.

Another difference between hypothesis and prediction is that hypothesis will result in providing answers or conclusions to a phenomenon, leading to theory, while prediction will result in providing assumptions for the future or a forecast.

While a hypothesis is directly related to statistics, a prediction, though it may invoke statistics, will only bring forth probabilities.

Moreover, hypothesis goes back to the beginning or causes of the occurrence while prediction goes forth to the future occurrence.

The ability to be tested is another difference between hypothesis and prediction. A hypothesis can be tested, or it is testable whereas a prediction cannot be tested until it really happens.

Hypothesis and prediction are integral components in scientific and research studies. However, they are also used in the general context. Hence, hypothesis and prediction are two distinct concepts although they are related to each other as well. The main difference between hypothesis and prediction is that hypothesis proposes an explanation to something which has already happened whereas prediction proposes something that might happen in the future.

1. “Prediction.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 17 Sept. 2018, Available here . 2. “Hypothesis.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 20 Sept. 2018, Available here . 3. Bradford, Alina. “What Is a Scientific Hypothesis? | Definition of Hypothesis.” LiveScience, Purch, 26 July 2017, Available here . 4. “Understanding Hypotheses and Predictions.” The Academic Skills Centre Trent University, Available here .

Image Courtesy:

1. “Colonial Flagellate Hypothesis” By Katelynp1 – Own work (CC BY-SA 3.0) via Commons Wikimedia 2. “USA weather forecast 2006-11-07” By NOAA – (Public Domain) via Commons Wikimedia

About the Author: Upen

Upen, BA (Honours) in Languages and Linguistics, has academic experiences and knowledge on international relations and politics. Her academic interests are English language, European and Oriental Languages, Internal Affairs and International Politics, and Psychology.

You May Also Like These

Leave a reply cancel reply.

University of Lethbridge

Science Toolkit

What is a Hypothesis?

A hypothesis (plural: hypotheses) is in its simplest form nothing more than an idea about how the world works. For example, “the moon is made of green cheese” is a valid hypothesis. But there are several characteristics which separate useful scientific hypotheses from those which are impractical. First and foremost, a hypothesis must be testable. We must (at least in principle) be able to design an experiment which will allow us to determine whether the hypothesis is false. Keep in mind that we can never prove any hypothesis is completely true because we can always

English chemist Robert Boyle (1627-1691) was one of the first scientists to explicitly adopt a program of hypothesis testing. imagine new circumstances in which it has not been tested, or other possible explanations for the results we have obtained. It is much easier to show, with a high degree of confidence, that a hypothesis is false. If it is not consistent with the results of a well designed and executed experiment, we are forced to accept that the hypothesis is false. If a hypothesis is not falsifiable, it is outside the realm of science. Note that the “green-cheese hypothesis” meets this test. A hypothesis should also be plausible. That is, the hypothesis, should be consistent with what we already know about the subject being investigated, and its parts should be logically and mathematically sound. We often celebrate the creative spark by which new hypotheses come to light. But typically that moment of inspiration follows a great deal of perspiration racked up in a thorough review of previous research in the subject. A hypothesis may in the end be a guess, but it should be the best guess possible. Given what we know about astronomy (and cheese production) the”green-cheese hypothesis” is not plausible, and not worth investing much of our time and resources in testing. What are predictions?

The predictions of a hypothesis set out what we expect to see if the hypothesis is true. (This is where we use deductive “If-Then” logic.) Experiments are designed to test specific predictions of the hypothesis. The “green-cheese hypothesis” predicts that material collected from the moon would contain milk proteins and fungi. These predictions could be tested by bringing material back from the moon, and testing its chemical structure. The hypothesis also makes predictions about the wavelengths of light reflected from the moon, a field called spectroscopy. (These predictions have actually been tested, believe it or not. Needless to say the hypothesis was not supported!) Three main factors make a prediction useful in testing a hypothesis: The prediction should be specific to the hypothesis (i.e. no other hypotheses make the same prediction). If several hypotheses predict the same outcome of an experiment, we will need to do further experiments to distinguish between them. The prediction should provide results which are unambiguous. It should be practical and economically feasible to run the experiment. A prediction is really nothing more than a simpler hypothesis — practical to test — derived from a larger hypothesis. Note that a prediction does not have be about the future, but it does have to apply to a situation we have not looked at yet. We are free to use the results of previous experiments to develop a new hypothesis, but we can’t then test our predictions against the results of those old experiments — to do so would be arguing in circles. Are theories different from hypotheses?

A “theory” has no formal definition in science (Style Manual Committee, CBE 1994). Hypotheses which have considerable support from experiments, and which are useful in explaining a fairly wide range of phenomena, are “upgraded” to theories, for example Darwin’s Theory of Evolution by Natural Selection, or the Theory of Plate Tectonics (which explains the movement of continents). So a theory is simply a well-tested and widely useful hypothesis, and there’s no strict rules defining when a hypothesis becomes a theory. Theories which are extremely well supported by experiments, particularly those which can be expressed as simple mathematical equations, are often called laws, e.g. Newton’s Law of Gravitation, Kepler’s Laws of Motion, or Mendel’s Laws of Genetics. Again, no one has yet laid out a strict set of rules for defining a natural law. A final term that scientists use to describe their ideas is a model. This dates back to the time when physical models were one of the few tools researchers had in investigating phenomena which were too big or too small to manipulate directly. Physical models are still used in science. Francis Crick and James Watson used a scale model of a DNA molecule to help them deduce its structure (Giere 1997). But scientists also use mathematical models to help them understand how different factors will interact. The development of computers has vastly increased the scope of mathematical models, and made them accessible even to non-mathematicians. Why are hypotheses important?

Philosopher of science Karl Popper likened a hypothesis to a searchlight, which the researcher shines on the relevant portion of nature (Davies 1973). It tells us which experiments are the important ones to perform, and which observations the important ones to make, out of an infinite number of possibilities. Without hypotheses scientists would be reduced to bean counters, and science to a collection of facts without organization or purpose. A hypothesis is the cornerstone used in building an elegant, structured body of knowledge from the apparent chaos of nature. (So they’re pretty important, eh!)

Hypotheses Versus Predictions

Hypotheses and predictions are not the same thing..

Posted January 12, 2018

Blogs are not typically places where professors post views about arcane matters. But blogs have the advantage of providing places to convey quick messages that may be of interest to selected parties. I've written this blog to point students and others to a spot where a useful distinction is made that, as far as I know, hasn't been made before. The distinction concerns two words that are used interchangeably though they shouldn't be. The words are hypothesis (or hypotheses) and prediction (or predictions).

It's not uncommon to see these words swapped for each other willy-nilly, as in, "We sought to test the hypothesis that the two groups in our study would remember the same number of words," or "We sought to test the prediction that the two groups in our study would remember the same number of words." Indifference to the contrast in meaning between "hypothesis" and "prediction" is unfortunate, in my view, because "hypothesis" and "prediction" (or "hypotheses" and "predictions") mean very different things. A student proposing an experiment, or an already-graduated researcher doing the same, will have more gravitas if s/he states a hypothesis from which a prediction follows than if s/he proclaims a prediction from thin air.

Consider the prediction that the time for two balls to drop from the Tower Pisa will be the same if the two balls have different mass. This is the famous prediction tested (or allegedly tested) by Galileo. This experiment — one of the first in the history of science — was designed to test two contrasting predictions. One was that the time for the two balls to drop would be the same. The other was that the time for the heavier ball to drop would be shorter. (The third possibility, that the lighter ball would drop more quickly, was logically possible but not taken seriously.) The importance of the predictions came from the hypotheses on which they were based. Those hypotheses couldn't have been more different. One stemmed from Aristotle and had an entire system of assumptions about the world's basic elements, including the idea that motion requires a driving force, with the force being greater for a heavier object than a lighter one, in which case the heavier object would land first. The other hypothesis came from an entirely different conception which made no such assumptions, as crystallized (later) by Newton. It led to the prediction of equivalent drop times. Dropping two balls and seeing which, if either, landed first was a more important experiment if it was motivated by different hypotheses than if it was motivated by two different off-the-cuff predictions. Predictions can be ticked off by a monkey at a typewriter, so to speak. Anyone can list possible outcomes. That's not good (interesting) science.

Let me say this, then, to students or colleagues reading this (some of whom might be people to whom I give the URL for this blog): Be cognizant of the distinction between "hypotheses" and "predictions." Hypotheses are claims or educated guesses about the world or the part of it you are studying. Predictions are derived from hypotheses and define opportunities for seeing whether expected consequences of hypotheses are observed. Critically, if a prediction is confirmed — if the data agree with the prediction — you can say that the data are consistent with the prediction and, from that point onward you can also say that the data are consistent with the hypothesis that spawned the prediction. You can't say that the data prove the hypothesis, however. The reason is that any of an infinite number of other hypotheses might have caused the outcome you obtained. If you say that a given data pattern proves that such-and-such hypothesis is correct, you will be shot down, and rightly so, for any given data pattern can be explained by an infinite number of possible hypotheses. It's fine to say that the data you have are consistent with a hypothesis, and it's fine for you to say that a hypothesis is (or appears to be) wrong because the data you got are inconsistent with it. The latter outcome is the culmination of the hypothetico-deductive method, where you can say that a hypothesis is, or seems to be, incorrect if you have data that violates it, but you can never say that a hypothesis is right because you have data consistent with it; some other hypothesis might actually correspond to the true explanation of what you found. By creating hypotheses that lead to different predictions, you can see which prediction is not supported, and insofar as you can make progress by rejecting hypotheses, you can depersonalize your science by developing hypotheses that are worth disproving. The worth of a hypothesis will be judged by how resistant it is to attempts at disconfirmation over many years by many investigators using many methods.

Some final comments.... First, hypotheses don't predict; people do. You can say that a prediction arose from a hypothesis, but you can't say, or shouldn't say, that a hypothesis predicts something.

Second, beware of the admonition that hypotheses are weak if they predict no differences. Newtonian mechanics predicts no difference in the landing times of heavy and light objects dropped from the same height at the same time. The fact that Newtonian mechanics predicts no difference hardly means that Newtonian mechanics is lightweight. Instead, the prediction of no difference in landing times demands creation of extremely sensitive experiments. Anyone can get no difference with sloppy experiments. By contrast, getting no difference when a sophisticated hypothesis predicts none and when one has gone to great lengths to detect even the tiniest possible difference ... now that's good science.