The immigrant workforce supports millions of US jobs

Subscribe to global connection, dany bahar , dany bahar nonresident senior fellow - global economy and development @dany_bahar carlos daboin contreras , and carlos daboin contreras consultant - workforce of the future initiative at brookings @daboincj greg wright greg wright fellow - global economy and development @gregcwright.

October 17, 2022

Dozens of empirical studies have found that immigration benefits American workers. Even immigrant workers with little formal education have, with some exceptions , been found to have negligible effects on the wages of similarly educated workers .

As part of Brookings Workforce of the Future initiative’s ongoing efforts to identify immigration policies that benefit American workers, we present a new perspective on the role that immigrants play in the U.S. economy. Using the “complementarity index,” we show that immigrant workers are broadly complementary to natives, both because immigrants work in occupations that serve an unusually wide range of industries, and also because immigrant-intensive occupations often complement other jobs. Acknowledging this complementarity is essential given that current trends in occupation growth imply that the immigrant workforce will become increasingly central to the U.S. economy in the coming years.

In Figure 1 each dot represents an occupation. The vertical axis measures the share of workers in that occupation that were born abroad, using Census data from 2019. The horizontal axis tracks our own “complementarity index,” which measures the extent to which each occupation complements all others. The higher the index, the more that workers in the occupation are likely to fuel demand for other jobs.

Figure 1. Immigrants and occupational complementarity

Source: Census Bureau and authors’ calculations

The logic of our complementarity index is that an occupation is considered complementary to other occupations for two reasons: first, if it is present in many industries, in effect influencing the way goods and services are produced throughout the economy; and second, if within an industry its employment share grows or shrinks in tandem with other occupations, indicating that its use is tightly linked to the use of other workers. Formally, the measure captures the share of industries in which any two occupations were both present together and simultaneously grew or shrank over time. For example, we find that the complementarity between “food and beverage serving workers” and “cooks and food preparation workers” is 0.49, a relatively high value that indicates that the two occupations were used together in 49 percent of U.S. industries and, at the same time, that their employment shares were positively correlated.

The overall complementarity index (the horizontal axis of Figure 1) is then the simple average of all these pairwise complementarities for each occupation. For instance, “Office and Administrative Support Workers” and “Financial Specialists” are two of the most complementary occupations, reflecting both their pervasiveness in the economy and the fact that any particular occupation is likely to be reliant on administrative and financial support.

While recognizing that there may be many reasons for these observed correlations, the patterns in the figure suggest that millions of immigrants work in occupations that are central to the rest of the workforce, thereby supporting millions of American jobs. In fact, Figure 1 indicates that the majority of the most immigrant-intensive occupations are above average on this index.

Moreover, the concentration of immigrants in occupations that are central to the U.S. economy will be the case well into the future, as many of these highly central occupations are projected to be among the fastest growing jobs over the next few years, as Figure 2 shows. In the figure, the horizontal axis shows the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ projected employment growth for each occupation for the period 2020-2030, while the vertical axis measures the share of foreign-born workers in each occupation in 2019.

Figure 2. Immigrants and future job growth

The occupations in the upper-right quadrant correspond to jobs that are both immigrant intensive and fast growing (the dotted line marks the average value in both instances). For instance, “home health and personal care” occupations—which include nurses and other health professionals—will add over one million workers over the next few years, and approximately 25 percent of workers in these jobs were foreign-born, as of 2019.

A major challenge for policymakers is identifying the highest value policies. Our complementarity index addresses this by identifying specific parts of the immigrant workforce that create significant and widespread benefits for U.S. workers.

Taking the two figures together, we see that there are a handful of occupations that are immigrant-intensive, fast-growing, and that also have high overall complementarity with the rest of the economy according to our measure above. A few of these are “motor vehicle operators,” “food preparation workers,” “material moving workers,” and “building cleaning and pest control workers.” Each of these jobs requires little formal education but serves as a vital link along a wide range of industry production chains.

A major challenge for policymakers is identifying the highest value policies. Our complementarity index addresses this by identifying specific parts of the immigrant workforce that create significant and widespread benefits for U.S. workers. Accordingly, the index can serve as one basis for identifying the parts of the economy that would benefit most from targeted immigration reforms.

Related Content

Greg Wright, Dany Bahar, Ian Seyal

June 17, 2022

Dany Bahar, Greg Wright

November 18, 2021

Labor & Unemployment

Global Economy and Development

Benjamin H. Harris, Liam Marshall

April 2, 2024

William A. Galston

March 8, 2024

Wendy Edelberg, Tara Watson

March 7, 2024

Migrant workers still at great risk despite key role in global economy

Facebook Twitter Print Email

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the key role that migrant workers play in the global economy, as well as the “terrible risks” that they are forced to take, to find work.

According to the new International Organization for Migration ( IOM ) Global Migration Indicators (GMI) 2021 report, launched on Thursday, over the past decade migrants in the worldwide labour force have tripled.

IOM’s Global Migration Data Analysis Centre (GMDAC) also flagged that remittances sent home to lower and middle-income countries (LMICs) have outpaced foreign aid.

The analysis featured on the Global Migration Data Portal , provides snapshots of the latest statistics and trends, including the impacts of COVID-19 on mobility.

For example, remittances made up more than 25 per cent of total GDP last year in El Salvador, Lebanon, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Tonga.

“The availability of timely and reliable data can help us maximize the potential of migration for development ”, said Ugochi Daniels, IOM Deputy Director General for Operations.

Demand rising

Migration trends at a glance.

More people than ever live in a country they were not born in.

More than one billion people are on the move.

Many migrate out of necessity.

One in 30 people is a migrant.

One in 95 is forcibly

As exemplified by the many roles of migrants considered ‘essential’ during the COVID-19 pandemic, the report highlights an increase in demand for their labour.

Foreign doctors account for 33 per cent of the United Kingdom’s physicians, according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and there is an overall reliance on foreign healthcare workers in Europe and the United States.

Surge in overseas workers

There are nearly 170 million foreign workers globally, according to the latest IMO estimates – more than triple the 53 million registered in 2010.

And foreign-born workers play a growing role in the labour force, making up an estimated five per cent of today’s global workforce.

“As we celebrate International Migrants Day this week, this report stands as a clear reminder of the role migrants play in the development of their communities worldwide”, said Frank Laczko, GMDAC Director.

“But while the global economy continues to rely heavily on migrant workers, people continue to face terrible risks when they cannot access legal pathways in their search for better opportunities.”

Migrant safety

While migration policies are difficult to measure, the data available show a trend toward limiting safe, legal migration options .

🆕 Global Competency Standards for #HealthWorkers will provide quality, culturally sensitive care to migrants and refugees, a 🔑 step towards achieving #HealthForAll, including for people on the move.👉 https://t.co/W0rOzuud4Q pic.twitter.com/sZ62jr547n World Health Organization (WHO) WHO

While 81 per cent of the countries participating in IOM ’s Migration Governance Indicators (MGI) have at least one government body dedicated to border control, just 38 per cent have a defined national migration strategy, with only 31 per cent aligning it with a national economic development strategy.

“This reports highlights…the invaluable contributions migrants have in our communities and economies, and the need for concrete action to increase legal channels”, Ms. Daniels said.

Setting global standards

Also on Thursday, the World Health Organization ( WHO ) published the agency’s new Global Competency Standards for refugee and migrant health services to strengthen countries’ ability to provide services to refugees and migrants by defining markers to be incorporated into health workers’ education and practices.

“While facing similar health risks to their host communities, refugees and migrants may have specific health needs and are often vulnerable to adverse health outcomes due to their mobility, living and working conditions”, said Santino Severoni, Director of the WHO Health and Migration Programme.

The health workforce has a vital role in providing inclusive services that are respectful of cultural, religious, and linguistic needs, said the UN health agency.

“Refugees and migrants face obstacles in accessing people-centred and culturally sensitive health services in both countries of transit and destination. These can include…restricted use of health services, all of which shape their interactions with the host country’s health system”, said the WHO Director.

The document is accompanied by a Curriculum Guide to support its operationalization.

The competencies can be tailored to various environments and take into consideration the requirements and constraints of local health systems as well as the characteristics of diverse refugee and migrant populations.

“2021 is the International Year of Health and Care Workers ”, reminded Jim Campbell, Director of WHO’s Health Workforce Department.

“The same workers must be supported with a competency-based education, as outlined in the Standards…to take us a step closer towards universal health coverage for all populations, including for refugees and migrants”.

- migrant workers

This website uses cookies

The only cookies we store on your device by default let us know anonymously whether you have seen this message. With your permission, we also set Google Analytics cookies. You can click “Accept all” below if you are happy for us to store cookies (you can always change your mind later). For more information please see our Cookie Policy .

Google Analytics will anonymize and store information about your use of this website, to give us data with which we can improve our users’ experience.

Created in partnership with the Helpdesk on Business & Human Rights

Migrant Workers

Who are migrant workers.

A migrant worker is a person who is to be engaged, is engaged or has been engaged in a remunerated activity in a State of which they are not a national [1] (information on internal migrant workers is included in a separate call-out box below). Migrant labour is work undertaken by individuals, families or communities who have moved from abroad. Migrant workers contribute to growth and development in their ‘host’ countries or regions, while countries or regions of origin benefit from the skills these workers gather while away, and from any taxes or remittances sent ‘home’.

Migrant workers often face challenges to and abuse of their human and labour rights in the workplace due to discrimination against them. This can occur in many ways, such as:

- Unfair recruitment practices, such as charging fees, requiring migrants to put up a bond, or giving misleading or incorrect information about a promised job;

- Trafficking or smuggling workers across borders for work, and/or entering the worker into forced labour in the new destination;

- Unequal access to employment rights, remuneration, social security, trade union rights, employment taxes or access to legal proceedings and remediation; and

- Workplace racism or discrimination.

What is the Dilemma?

Migrant workers can make a positive contribution to business performance and productivity by filling skill gaps, increasing access to international knowledge, strengthening contacts in international networks and local networks through new language skills and cultural awareness.

However, migrant labour can also pose a dilemma to businesses as migrant workers — whether in a regular or an irregular situation — can face a range of challenges to their rights, including discrimination from other workers, employers and laws, unfair working conditions and harmful recruitment practices. Migrant workers are particularly at risk of other human rights violations, such as being trapped in forced labour due to abuse of vulnerability, a lack of understanding of their rights and a lack of social capital or power.

Businesses can struggle to ensure that migrant workers in their operations and supply chains have their rights upheld, especially when Governments do not fulfil their duty to protect and their obligations under international human rights instruments (such as the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families ).

Internal Migrant Workers

While this issue focuses on international migrant workers given their specific vulnerabilities to labour rights abuses, internal migrant workers also face similar challenges in securing adequate working and living conditions.

Exact global figures for the number of internal labour migrants (those who have moved within their country for work) are not known. However, disruptions arising out of the coronavirus pandemic have drawn global attention to their plight — particularly in India, where millions of internal migrants were left economically devastated by state-wide lockdowns in 2020.

Internal migrants remain on the periphery of the COVID-19 recovery process and are disadvantaged when it comes to securing social protections, safe living and working conditions and access to justice. India’s migrant crisis has also put the spotlight on other countries whose economies are dependent on internal migration, such as China, Thailand, Indonesia, Kenya, Uganda, South Africa and Brazil.

Prevalence of Migrant Labour

According to the UN World Migration Report 2022 , there have been ‘historic’ changes in migration in the last decade, and even during COVID-19, there has been an increase in the number of displaced people in the world. While many of those displaced are fleeing from harm, many others are migrating due to dire economic conditions. It is estimated that there were more than 280 million international migrants globally in 2020, 245 million of which are working age (aged 15 and over). According to the International Labour Organization ( ILO ), the number of international migrant workers totalled 169 million in 2021, constituting nearly 5% of the global workforce.

Key drivers contributing to the growing mobility of workers:

- Lack of jobs and decent working conditions;

- The widening income inequalities within and between countries;

- A growing demand for skilled and low-skilled workers in migrant destination countries (often driven by strong growth, ‘shortages’ of domestic labour or rigid societal norms);

- Demographic changes, with countries seeing declining labour forces and aging populations.

Key trends include:

- According to the ILO , women constitute 41.5% and men 58.5% of migrant workers (2021).

- Sector figures show that 66.2% of migrant workers are in services, 26.7% are in industry and 7.1% are in agriculture (2021).

- Of the estimated 169 million international migrant workers, 67.4% are in high-income countries and 19.5% in upper middle-income countries (2021).

- ILO research suggests that the world’s migrant workers are distributed among the major regions as follows: Europe and Central Asia, 37.7%; Americas, 25.6%; Arab States, 14.3%; Asia and the Pacific, 14.2%; and Africa, with only 8.1% (2021).

- The labour force participation rate of migrants at 69% is higher than the labour force participation of non-migrants at 60.4% (2021).

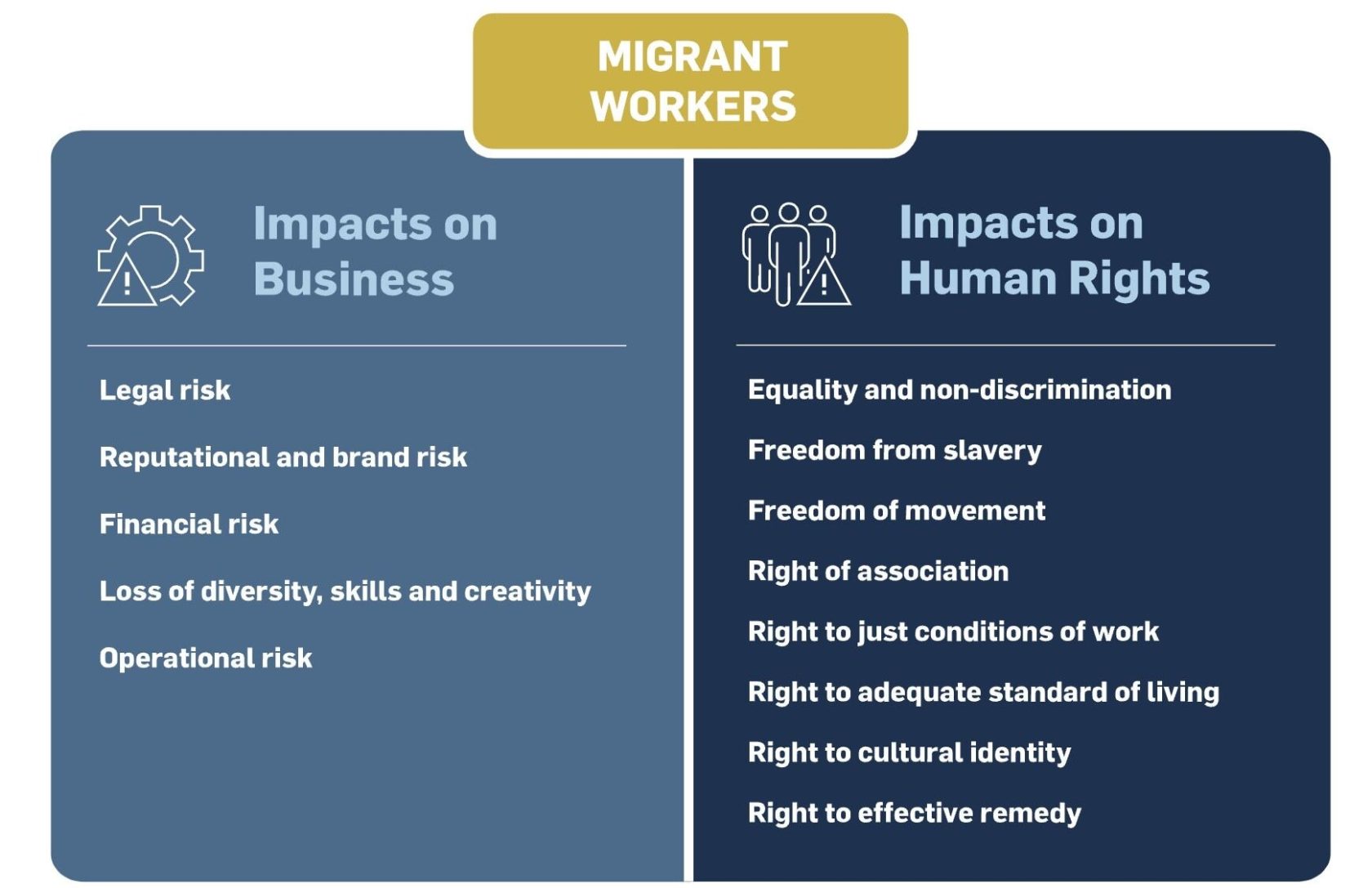

Impacts on Businesses

Businesses can be impacted by migrant labour risks in their operations and supply chains in multiple ways:

- Legal risk : There is a close link between migrant labour and human rights abuses such as forced labour, modern slavery and child labour, as migrant workers are often in situations of vulnerability. Companies can face legal charges and severe consequences if they are found to have any of the above issues in their operations or supply chains.

- Reputational and brand risk : Campaigns by non-governmental organizations (NGOs), trade unions, consumers and other stakeholders against multinational corporations (MNCs) alleged to abuse migrant workers can result in reduced sales and brand erosion.

- Financial risk : Suppliers and clients may end contracts and relationships with companies that are found to abuse migrant workers’ rights, or be linked to abuse, in their supply chain, resulting in reduced sales. Divestment and/or avoidance by investors and finance providers (many of which are increasingly applying environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria to their decision-making) can result in reduced or more expensive access to capital and reduced shareholder value.

- Loss of diversity, skills and creativity : Where migrant workers are not treated fairly or with respect, they may leave for other employment and leave behind a skills gap.

- Operational risk : Changes to a company’s supply chains made in response to the discovery of harmful migrant labour conditions may result in disruption. For example, companies may feel the need to terminate supplier contracts (resulting in potentially higher costs and/or disruption) and direct sourcing activities to lower-risk locations.

Impacts on Human Rights

Abuse of migrant workers has the potential to impact a range of human rights, [2] including but not limited to:

- Right to equality of treatment and non-discrimination ( ICRMW , Articles 43 and 45, ICCPR , Article 2, ICESCR , Article 2): Migrant workers can be subject to unequal treatment when compared to nationals. This is likely to occur in recruitment processes, their treatment at the workplace as well as in terms of the legal protections that they are afforded in the workplace.

- Right to freedom from slavery and forced labour ( UDHR , Article 4, ICRMW , Article 11, ICCPR , Article 8): Migrant workers are at a higher risk of being subject to conditions that may amount to forced labour and/or modern slavery. For example, migrant workers may face the retention of identity documents, debt bondage and restriction of movement, which are some of the indicators of forced labour.

- Right to freedom of movement ( ICRMW , Article 39, UDHR , Article 13): The freedom of movement of migrant workers can be severely restricted through, for example, the confiscation of passports or other travel documents.

- Right of migrants to form, join and participate in associations and trade unions ( ICRMW , Article 26 and 40; ICCPR , Article 22; ICESCR , Article 8): In many situations, migrants may — due to their legal status, the legal frameworks in which they operate in or their relatively weak negotiating position — be denied the right to freedom of association. ICCPR and ICESCR specify that all workers (including migrant workers in a regular situation) have the right to form and join trade unions for the protection of their interests. In addition, Article 26 of the ICRMW affords migrant workers in both regular and irregular situations the right to join and participate in the activities of associations and trade unions.

- Right to just and favourable conditions of work ( ICRMW , Article 25; ICESCR , Article 7): Many migrants experience lower pay and poorer working conditions than their domestic counterparts. This can be due to discrimination, prevailing legal frameworks, the legal status of migrant workers and market dynamics.

- Right to an adequate standard of living (including access to adequate food, clothing, housing and water) ( ICRMW , Article 43; ICESCR , Article 11): Companies that provide housing to migrant workers can directly infringe on this right if the housing is not of an adequate standard.

- Rights to cultural identity ( ICRMW , Article 31, ICCPR , Article 27): Migrants have the right to enjoy their own culture, practice their own religion, and to speak their own language without discrimination. Due to their status, migrant workers may be denied this right as a matter of official policy or through societal discrimination.

- Right to an effective remedy for acts violating fundamental rights ( ICRMW , Article 83, ICCPR , Article 3): A lack of accessible operational-level grievance mechanisms may hinder migrant workers from accessing remedies for human and labour rights abuses. This is particularly the case where the legal framework and culture in a country prevent migrants from seeking adequate access to remedy.

The following SDG targets relate to migrant workers :

- Goal 8 (“ Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all ”), Target 8.8 : Protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments of all workers, including migrant workers, particularly women migrants, and those in precarious employment.

- Goal 10 (“ Reduce inequality within and among countries ”), Target 10.7 : Facilitate orderly, safe, regular and responsible migration and mobility of people, including through implementation of planned and well-managed migration policies.

Key Resources

The following resources provide further information on how businesses can address violations of migrant workers’ rights in their operations and supply chains:

- ILO, Fair Recruitment Toolkit : A modular training manual on fair recruitment to support in the design and implementation of fair recruitment practices.

- Institute for Human Rights and Business, Migration with Dignity: A Guide to Implementing the Dhaka Principles : A practical guide to implementing the Dhaka Principles of fair and equal labour for migrants. The Dhaka Principles provide a roadmap that traces the migrant worker from recruitment, through employment, to the end of contract and provides key principles that employers and migrant recruiters should respect at each stage in the process to ensure migration with dignity.

- BSR, Migrant Worker Management Toolkit: A Global Framework : A toolkit for respecting the rights of migrant workers throughout businesses and global supply chains.

- [email protected]

Photo essay: In the Philippines, women migrant workers rebuild lives, advocate for each other

Date: 16 September 2016

A global programme by UN Women, “Promoting and Protecting Women Migrant Workers’ Labour and Human Rights”, supported by the European Union and piloted in the Philippines, works to build the capacities of migrant women’s organizations and networks to better serve and assist women migrant workers. UN Women spoke with migrant women returnees and community leaders from La Union province, over 260 miles from Manila, where the programme supports various migrant women’s organizations. These are their stories.

“I migrated to the Middle East as a domestic worker because my husband was about to lose his job due to poor health. I worked long work hours—I was the only domestic worker for a household of ten—and endured verbal abuse. There was a time that I didn’t receive any salary for several months…,” shares 55-year old Virginia Carriaga.

After two years of abuse, Carriaga escaped from her last work place in Lebanon, and sought assistance from the Philippines Embassy. Prior to her repatriation, in the two months that she spent at the Embassy-sponsored shelter in Beirut, she became a spokesperson for other women migrant workers. Today, Carriaga is a successful business woman, owner of a variety store in Balaoan, with the assistance and trainings that she received from the government and women migrant workers’ organizations.

Primitiva Vanderpoorten, a retired nurse who worked in the United Kingdom for several years, invested her income in properties in her home country. Today she offers her resort hotel in Luna as a venue for meetings of Bannuar Ti La Union, an organization for women migrant workers, where she is a member: “Even as a nurse, I experienced offensive remarks from patients. They would ask why I was in their country and that I should go back to my country.”

“My son did not finish high school and got involved in delinquent activities. He resented me for leaving him in Philippines. Have I been a bad mother, I asked myself,” shares Virginia Estepa, a 62-year-old former woman migrant worker who now works as a health worker at the barangay (smallest unit in the community) in Naguilian. Like many others, Estepa migrated overseas to provide for her family. As women migrate for work, leaving behind their children, the social cost of the impact on their children is often less known or understood. Research shows that fathers, grandmothers and the extended families care for children left behind.

UN Women’s programme, piloting in three countries—Philippines, Mexico and Moldova—provides trainings to organizations and women migrant workers’ groups to strengthen their advocacy skills, knowledge on migrant women’s rights, organizational development, strategic planning and enterprise governance. Women migrant workers’ organizations and groups have been instrumental in providing information that enables women to migrate safely and know how to report abuse or seek assistance.

The training on organizational development was particularly useful for Carmelita Nulledo, 52, a former domestic worker from Singapore and Hong Kong and now a farmer and volunteer in various organizations. “From the action planning during our training, we have proceeded with mapping and simple surveys in the community. This will generate data about migrant women and inform any local planning and policies to address the needs of women migrant workers,” she shares. Like many of the migrant women impacted by the project, Nulledo volunteers at the local assistance desks for migrant workers and their families. “I had a positive migration experience, and now I am motivated to help others, she adds.

Women migrant workers’ organizations in the Philippines also provide reintegration assistance to returnee women migrants by providing livelihood and business trainings, and helping them access assistance programmes, such as scholarship for education and training, enterprise development funds, business counseling, legal and psychosocial services provided by the government under the national law and through local ordinances.

Delilah Dulay, 40, works as a master cutter at the Aringay Bannuar Garments Production, which is funded by the Department of Labour and Employment and the local government of Aringay in La Union province and provides decent work for migrant women returnees. Dulay had migrated to Qatar to improve her income. She landed with a domestic worker’s job where she barely slept for two hours every day and was paid significantly less than the salary she was promised. Upon her return to La Union, Dulay underwent trainings through Bannuar Ti La Union as part of the UN Women project and learned about her rights and gained skills as a garment worker.

“Being a member of a women migrant workers’ group helps me and the others find our confidence in facing day to day life and its challenges. We have a common bond stemming from similar experiences,” she says.

Edna Valdez, 58, worked for four years as a domestic worker in Hong Kong under harsh conditions. Today, she is the President of Bannuar Ti La Union. “The main challenge for women migrant workers is that they don’t know what rights they have. Even when there are laws and services in place, they don’t know how to claim their rights or access support. That’s why we lobby the local government units to set up Migrant Desks at each municipal office, in compliance with the national law, where migrants and their families can access information and support,” says Valdez.

Today, she volunteers at the Migrant Desk at San Fernando City La Union three times a week, refers women migrant workers to relevant government units for legal assistance and reintegration support. She also delivers trainings to prospective women migrant workers to help them identify the warning signs and risks of trafficking and illegal recruitment, and how to access legal assistance and support if they are abused.

As of June 2016, 118 women migrant workers have been trained on their rights, and an additional 45 on entrepreneurship management and 49 on organizational development. The pilot programme has developed critically needed capacity of women migrant workers and their groups so that they are able to build upon the gains made so far and continue to advocate for women migrant workers’ rights at the local and national levels.

Credit for all photos: UN Women/Norman Gorecho

[1] UN Women (2016). Filipino Women Migrant Workers Fact Sheet

- ‘One Woman’ – The UN Women song

- UN Under-Secretary-General and UN Women Executive Director Sima Bahous

- Kirsi Madi, Deputy Executive Director for Resource Management, Sustainability and Partnerships

- Nyaradzayi Gumbonzvanda, Deputy Executive Director for Normative Support, UN System Coordination and Programme Results

- Guiding documents

- Report wrongdoing

- Programme implementation

- Career opportunities

- Application and recruitment process

- Meet our people

- Internship programme

- Procurement principles

- Gender-responsive procurement

- Doing business with UN Women

- How to become a UN Women vendor

- Contract templates and general conditions of contract

- Vendor protest procedure

- Facts and Figures

- Global norms and standards

- Women’s movements

- Parliaments and local governance

- Constitutions and legal reform

- Preguntas frecuentes

- Global Norms and Standards

- Macroeconomic policies and social protection

- Sustainable Development and Climate Change

- Rural women

- Employment and migration

- Facts and figures

- Creating safe public spaces

- Spotlight Initiative

- Essential services

- Focusing on prevention

- Research and data

- Other areas of work

- UNiTE campaign

- Conflict prevention and resolution

- Building and sustaining peace

- Young women in peace and security

- Rule of law: Justice and security

- Women, peace, and security in the work of the UN Security Council

- Preventing violent extremism and countering terrorism

- Planning and monitoring

- Humanitarian coordination

- Crisis response and recovery

- Disaster risk reduction

- Inclusive National Planning

- Public Sector Reform

- Tracking Investments

- Strengthening young women's leadership

- Economic empowerment and skills development for young women

- Action on ending violence against young women and girls

- Engaging boys and young men in gender equality

- Sustainable development agenda

- Leadership and Participation

- National Planning

- Violence against Women

- Access to Justice

- Regional and country offices

- Regional and Country Offices

- Liaison offices

- UN Women Global Innovation Coalition for Change

- Commission on the Status of Women

- Economic and Social Council

- General Assembly

- Security Council

- High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development

- Human Rights Council

- Climate change and the environment

- Other Intergovernmental Processes

- World Conferences on Women

- Global Coordination

- Regional and country coordination

- Promoting UN accountability

- Gender Mainstreaming

- Coordination resources

- System-wide strategy

- Focal Point for Women and Gender Focal Points

- Entity-specific implementation plans on gender parity

- Laws and policies

- Strategies and tools

- Reports and monitoring

- Training Centre services

- Publications

- Government partners

- National mechanisms

- Civil Society Advisory Groups

- Benefits of partnering with UN Women

- Business and philanthropic partners

- Goodwill Ambassadors

- National Committees

- UN Women Media Compact

- UN Women Alumni Association

- Editorial series

- Media contacts

- Annual report

- Progress of the world’s women

- SDG monitoring report

- World survey on the role of women in development

- Reprint permissions

- Secretariat

- 2023 sessions and other meetings

- 2022 sessions and other meetings

- 2021 sessions and other meetings

- 2020 sessions and other meetings

- 2019 sessions and other meetings

- 2018 sessions and other meetings

- 2017 sessions and other meetings

- 2016 sessions and other meetings

- 2015 sessions and other meetings

- Compendiums of decisions

- Reports of sessions

- Key Documents

- Brief history

- CSW snapshot

- Preparations

- Official Documents

- Official Meetings

- Side Events

- Session Outcomes

- CSW65 (2021)

- CSW64 / Beijing+25 (2020)

- CSW63 (2019)

- CSW62 (2018)

- CSW61 (2017)

- Member States

- Eligibility

- Registration

- Opportunities for NGOs to address the Commission

- Communications procedure

- Grant making

- Accompaniment and growth

- Results and impact

- Knowledge and learning

- Social innovation

- UN Trust Fund to End Violence against Women

- About Generation Equality

- Generation Equality Forum

- Action packs

- Skip to main content

Advancing social justice, promoting decent work

Ilo is a specialized agency of the united nations, receive ilo news, follow us on.

Labour migration

Facing the global jobs crisis: Migrant workers, a population at risk

The global economic crisis is posing new challenges for the world's 100 million migrant workers. They may face reduced employment and migration opportunities, worsening living and working conditions and increasing xenophobia. Although no massive return of migrant workers has been observed so far, the crisis is having repercussions on their earnings and the remittances they send home. Ibrahim Awad, Director of the International Migration Programme at the International Labour Office, published a new study entitled "The global economic crisis and migrant workers: Impact and response". Interview with ILO Online.

ILO Online: How does the impact of the crisis on migration vary across countries and sectors?

Mr. Awad: Depending on countries of destination, migrant workers are present in such sectors as construction, manufacturing, hotels and restaurants, health care, education, domestic service and agriculture. Some of these sectors – construction, manufacturing and hotels and restaurants – have been seriously affected by the crisis with migrant workers experiencing the major shocks. In the United States, Ireland, and Spain, migrant workers in construction were particularly affected. In Malaysia, Japan, and the Republic of Korea, the impact is in manufacturing which has the largest job losses. In contrast, other sectors (e.g., health care, domestic service, and education), in some countries, have seen employment growth. In the United States and Ireland, jobs in health care and education have

ILO Online: Does the crisis have an impact on labour migration flows?

Mr. Awad: Contraction of the economy and rising unemployment may prompt destination countries to introduce more restrictive labour migration policies. Origin countries, which often heavily depend upon the remittances from migrant workers, respond to the impact of the crisis by exploring new labour markets and introducing reintegration and employment packages. To date, no mass returns of migrant workers have been observed, but new outflows from some countries of origin have slowed down. For example, in Mexico, the net outflow dropped by over 50 per cent between August 2007 and August 2008 ( Note 1 ). Potential migrants, considering the high costs of migrating and reduced employment opportunities in the destination, have chosen to stay home. At the same time, the number of returning migrant workers in 2008 remained similar to the previous two years. Voluntary return programmes implemented by destination countries have fallen far short of the targeted numbers. Migrant workers often choose to remain despite deteriorating labour market conditions in order to preserve social security benefits. The adverse economic and employment situation in the origin country also discourages them from returning home.

ILO Online: Before the crisis, remittances were growing in all developing countries. Has the crisis reversed this trend?

Mr. Awad: The rates of growth of remittances has declined, and in some areas so has absolute volume. A number of countries in Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa and especially Central Asia have been seriously affected. Thus poverty reduction and the sustainability of economic activity and employment in some countries are at risk. However, in some countries, such as Egypt and Pakistan, during certain periods since the crisis broke out, remittances have increased despite the economic downturn, suggesting they acted as countercyclical measures (i.e. rising when the economy is weakening, and falling when the economy is strengthening). Remittances are the most visible and tangible benefits of labour migration. At the macro level they bring in foreign exchange and contribute to correcting balances on current accounts in countries of origin. In many countries, remittances represent a high proportion of GDP. Through their direct and multiplier effects, they sustain demand and thus stimulate economic activity. Employment is generated as a result. At the household level, remittances can contribute to poverty reduction and human capital development through expenditures on education and health care.

ILO Online: How does the crisis affect migrant workers specifically?

Mr. Awad: In times of crisis, slack demand for labour increases the likelihood of precarious and irregular employment. Perceived or actual competition for scarce jobs spurs xenophobic and discriminatory reactions of nationals against migrant workers and their families. While little evidence exists, it is likely that migrant workers will be forced to take on jobs in poor working conditions and/or in the informal economy. Certain groups and individuals may demand more protectionist measures or show aggressiveness towards migrants. Examples of such reactions exist in different regions. However, it is important to emphasize that violence and xenophobia against migrant workers are far from widespread.

ILO Online: Some countries of origin and destination have started to adopt policies to deal with the consequences of the crisis. Do these policies have an impact on migrant workers and labour migration?

Mr. Awad: Policies encouraging voluntary return put in place by some countries of destination have not realized their objectives up to now. A response to the crisis that only takes into account the decline in overall demand for labour, without regard to differential sectoral demands may end up generating irregular migration. It is still too early to assess the impact of more restrictive admission measures on the operation of labour markets and on the migration status of foreign workers. The employment situations in countries of origin and the remittances they receive will have to be monitored to examine the effectiveness of their adopted policy measures. This also applies to the protection of the rights of migrant workers.

ILO Online: What does the ILO recommend to reinforce the protection and recognition of the crucial role of migrant workers?

Mr. Awad: Migrant workers have participated in promoting economic growth and prosperity and the creation of wealth in countries of destination, while contributing to poverty reduction and development in their countries of origin. The future may harbour more adverse consequences for migrant workers than observed to date, if the crisis becomes drawn out. It is therefore important to adopt appropriate policy measures to maximize their contributions to both countries of origin and destination. For instance, economic stimulus packages put in place by countries of destination should equally and without discrimination benefit regular migrant workers. This would ensure the most efficient operation of labour markets and the best utilization of available labour. Using relevant international labour standards ( Note 2 ), social partners can work together in countries of origin and destination to improve labour migration policies that can respond to the crisis or capitalize on the opportunities ushered by it. The ILO Multilateral Framework on Labour Migration sets forth principles and provides guidelines that can be of great value in elaborating these policies.

Note 1 : According to the National Statistics, Geography and Information Institute

Note 2 : The ILO Conventions on migrant workers – Migration for Employment No. 97, (1949), the Migrant Workers (Supplementary Provisions) Convention No. 143, (1975) and the 1990 International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families, are the three conventions which define together a comprehensive charter of migrant rights and provide a legal basis for national policy and practice on migrant workers.

Labour Migration, Vulnerability, and Development Policy: The Pandemic as Inflexion Point?

- Introductory Article

- Published: 18 January 2021

- Volume 63 , pages 859–883, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Ravi Srivastava 1

10k Accesses

18 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This issue takes the current pandemic as a point of reference to reflect on the nature of migration processes in India which involve labour migrants who generally work in the lower rungs of the informal economy. It particularly focuses on the circular migrants who were hardest hit by the stringent lockdowns in India and abroad. While migration occurs for a variety of reasons and takes a number of forms, it mostly aims at improving the livelihood and employment prospects of the movers and supports the growth and development of the areas to which the movement occurs. But this does not happen without significant stress and costs. Patterns of unequal development, demographic changes, wars, and conflicts play a large role in migration. Overall, the global trend has been towards higher mobility, both between countries and within countries, although at various levels, the data is fuzzy. This has contributed to greater well-being and prosperity, notwithstanding the many stress points. However, migration is not a single phenomenon in terms of nature, distance, and temporality and migrant workers have diverse characteristics. Many are poor and have little or no skills or assets, and others are well placed and well endowed in skills and assets. The former have poor bargaining power, form segments at the lower end of the labour market at destination, and struggle to achieve basic rights. The diversity in characteristics is also shared by migrants moving within, and across, national boundaries.

Attempts to curtail or structure mobility are not new. This is obvious in the movement between countries since immigration controls and rules are available to sovereign countries. It is less obvious in the case of internal migration where constraints and barriers on specific types of migration mobility operate through higher economic and non-economic costs. Historically, short-term controls on pandemics such as the Corona-Cov-2 pandemic of 2020 have operated through checks on population mobility, which reduces spatial transmission risks (see de Haan in this volume). These restrictions have dramatic and negative consequences for the economy and for economically vulnerable populations. Among the vulnerable, migratory populations and refugees are likely to be deeply affected, but research and policies have a strong tendency to ignore the existence of such populations (De Haan 1999 ).

1 International Migration

Internal and international (including cross-border) migration is generally seen with different lenses. This is understandable because international migration is subject to a country’s sovereign control over its borders and is permitted through its immigration rules. Moreover, the costs of international migration and information asymmetries are much higher, but benefits to migrants could also be higher due to higher wage/earning differential between countries. While there are also other differences, both internal migration and international migration are impelled by similar factors-in the case of economic migration, lack of adequate opportunities at source, or availability of better opportunities at destination; or in other cases, force of compulsion (as in the case of refugee migration or internally displaced persons (IDPs) ); or other factors (Srivastava and Sasikumar 2005 ; King and Skeldon 2010 ; Srivastava and Pandey 2017 ).

Globally, international migration is a greater focus of monitoring and policy attention for various reasons (Srivastava and Pandey 2017 ). The ILO and the UN have adopted a number of specific conventions and recommendations to protect the rights of international migrant workers, while the UN, the IOM, and the World Bank routinely monitor the trends in international migration and remittances. On the other hand, internal migrants and migrant workers are guaranteed their rights and protected against exploitation under the laws of the land and the general ILO Conventions which are deemed to be sufficient to protect their interests (ibid.). Compared to international migration, internal migration is only the subject of sporadic reports.

The impact of the pandemic has been severe on international emigrant workers, particularly low-skilled emigrant workers on short-term contracts working in the informal economy and undocumented workers. Loss of jobs, wage theft, issues with visa extension, closure of border crossings, lack of access to any social protection mechanisms, cost of repatriation have all taken a heavy toll on them. Incomes also declined for those emigrants who continued in employment. The ILO estimates that global labour income losses, without income support measures, declined by 10.7 per cent during the first three-quarters of 2020 compared to the same period in 2019 (ILO 2020 ).

The World Bank (Ratha et al. 2020 ) currently estimates that international remittances would decline by 7.2 per cent in 2020, followed by a further decline in 2021. High return migration and low prospects of new emigration are estimated to cause an absolute decline in the total numbers of emigrants, more severe than the 2008 global crisis (ibid.).

For India, international migration is voluminous and India is the highest earner of international remittances, which, however, is projected to decline by about 9 per cent in 2020 (Ratha et al. 2020 ). On the other hand, India also has a significant volume of migration from other countries, although most of this from countries with which India shares a border (Srivastava and Pandey 2017 ). There is scanty literature on the impact of the pandemic on these migrants, whereas we know more about the actual and possible impact of the pandemic of international migrants, particularly worker migrants in the Gulf and other regions.

The broad pattern of Indian emigrants abroad was in the past dominated by middle and high-income states in the North, West, and South of the country. Over time, the pattern of worker migration tilted towards the Eastern states of the country-Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and West Bengal (Srivastava and Pandey 2017 ). The pandemic with its impact on oil revenues is likely to have a significant impact on the GCC countries which depend on oil exports due to falling oil revenues. As Abella and Sasikumar (this issue) show in their paper, trends in aggregate worker emigration closely mirror, albeit with a lag, the growth trends in the Gulf economies. They point out that the Government of India’s Vande Bharat mission brought back nearly 60000 stranded Indians from various countries abroad, of whom 170,000-180,000 were migrant workers. Since the journeys involved a direct travel cost of $350-400, many workers could not avail of them. Nonetheless, the likely scenarios of employment loss on incomplete contracts or wage loss for those migrants continuing to be employed imply a loss of earnings for the migrants as well as a loss in remittances. This loss increases when the “sunk costs” of migration in terms of recruitment costs are factored in. Abella and Sasikumar consider the segment of low-skilled workers, migrating to Saudi Arabia to be engaged in the construction sector. Based on the distribution of length of contract and earnings of this group, they project estimated loss in earnings and remittances under assumptions of job loss or lower wages. They point out that two counter tendencies may imply that the actual decrease in remittances may not be as high as anticipated: first, the tendency of employed migrants to remit a higher proportion of wages during crisis, and second, that the loss in employment may eventually not be very high due to the irreplaceability of low-skilled migrants in some sectors.

The Southern state of Kerala continues to have a large stock of migrants abroad-more than two million, particularly in the Gulf states. Kannan and Hari, in this issue, offer a long-term view of emigration from Kerala and hypothesise the impact of the pandemic of emigration and remittances in Kerala. Migrant workers from Kerala are currently estimated to be about 17-18 per cent of its workforce. Kannan and Hari estimates the number of migrants from Kerala and total remittances over nearly a half a century. Although emigration peaked around 2012-2013, remittances have shown a steady increase, but their contribution to state income declined from over a fifth at the beginning of this decade to about 14 per cent between 2015 and 2020, mainly due to a rapid growth in Kerala’s state income. Significantly, the secular increase in remittances was not reversed either by the Gulf wars or by global economic crises, including the 2008 crisis. The fact that total remittances increased despite a decline in the total number of migrants, Kannan and Hari note, was due to the changing educational and skill composition of the emigrant workforce, with a much smaller proportion engaged in manual and low-skilled jobs. The paper also analyses the macro-economic implications of the emigration for the state economy over different phases, its impact on the labour market, on household income and consumption and (increasing) inter-personal inequality, despite the state’s low multidimensional poverty index (MPI) and high human development index (HDI). The other negative aspect of Kerala’s development is the persistence of educated unemployment, especially among women, despite the safety valve of emigration. The third negative aspect is the declining tax collection effort shown by the share in net state domestic product (NSDP) of own tax revenue. The paper notes that the economic crisis precipitated by the pandemic confronts the state with multiple challenges and possibilities. As far as emigration is concerned, the crisis could be a turning point in terms of a sharp decline in Kerala’s large-scale labour migration to the Gulf countries, but alternatively, it could set off a beginning of a change in the composition of emigration if the demand for health care personnel increases in the Gulf as well as in other countries.

The Kerala migration story is examined from another perspective by Abraham (this issue), which can throw light on the long-term prospects open to return migrants affected by the current crisis (assuming that the short-term prospects could be overshadowed by the severity of the economic crisis and unemployment). Using the Kerala Migration Survey data, Abraham examines the occupational mobility of international migrants, pre-, during, and post-migration. Abraham points out that the major destination for migrants in Kerala is the GCC and 95 per cent of the migrations to the Gulf countries are on temporary contracts. Kerala still accounts for the highest Indian emigrant stock in the GCC. It is also the state with the highest return emigrant stock in India, and a high proportion of return emigrants are still in the working-age group and active in the labour force. The contractual jobs are mostly low skilled but offer a much higher earning potential to the migrants, although at the cost of deskilling for many, and downward occupational mobility. Their post-return occupational choices in the home labour market would be dependent on their level of human and physical capital and re-migration intentions, but termination or non-renewal of the migrant's contract could have an adverse impact on the occupational choices of the return migrants.

Using data from the 2011 Kerala Migration Survey, Abraham constructs three mobility matrices over the three phases of geographical mobility of return migrants in the economically active age group. The study finds that skilled blue-collar workers are in a higher proportion in all three stages of migration and they along with elementary workers form the largest proportion of return emigrants in Kerala. However, the proportion of workers is twice in the service sector while abroad, as compared to in the source region. The proportion of higher-skilled workers (professionals, associates, and technicians) are more or less stable over the three phases, while there is a significant rise (from negligible) in the percentage of workers reporting as managers/self-employed post-return. The data show a high occupational persistence among pre-emigration and post-return occupational choices, indicating that work experience abroad does not lead to a significant level of occupational mobility for return emigrants in Kerala. Around a fifth of the return migrants show upward mobility, while ten per cent moved to a lower occupational category. Only about 10 per cent are engaged in self-employment (mainly as proprietors and managers). Thus, the paper concludes that international migration does not lead to upward occupational mobility for most migrants and that there is limited skill augmentation ensuing from foreign work experience. Understanding these occupational trajectories in “normal” circumstances is more crucial in the current pandemic situation, with high numbers of return migrants, also unable to complete their contracts and requires an urgent consideration about the reintegration strategies for the migrants in the local economy and labour market.

2 Migration and Labour Circulation in India

Once households are considered as a site of production and social reproduction, a site where multiple strategies of subsistence converge, and which is placed in a social and cultural setting of kinship ties and the village, circular migration by individuals becomes part of a household strategy with diversification at its core (Ellis 1998 ). Lucas and Stark ( 1985 ) and the new economics of labour migration literature seek to explain these decisions by a risk spreading within households. Chen and Fan ( 2018 ) suggest that, in addition, migration transition theory, social network theories, and dual labour market theories also provide an explanation of labour market circulation. Of these, only the last emphasises the production structure and demand. The economies of production and social reproduction are shared between the migrant and the non-migrant part of the household in an intricate manner, enabling employers to meet only the basic cost of reproduction of the worker over the employment period, contributing to much greater flexibility and cheapening of labour. This has led to theorisations which focus on the dynamics of capital accumulation, capital labour relations, and how they incorporate the production and care economies (Breman 1996 and 2019 , Larche and Shah 2018 ).

Further, it may eventually be possible for migrants to take longer-term decisions, to migrate with their families, eventually even to uproot themselves almost entirely from their village settings. This has led to studies which explore changes in labour circulation over time and the decisions to migrate and settle permanently in urban areas (Chen and Fan 2018 ; Hu, Xu, and Chen 2011 ; Anh et al. 2012 ).

Labour migration may be seen as part of the larger phenomenon of labour mobility through which labour flows meet the requirements of spatially distinct regions. The larger phenomenon of labour mobility includes labour commuting at one end, and permanent migration, at the other. Circular migration falls between the two ends of this spectrum. The circular migration that is implied here may not have any fixity, in terms of location or temporality. It includes international migrants, cross-border migrants, or internal migrants.

Attempting to find a completely common ground between the various definitions of circular migration is not easy, and some parts of all definitions are debatable. Zelinsky ( 1971 : 225-226) defines circulation as:

a great variety of movements usually short term, repetitive or cyclical in nature, but all having in common the lack of any declared intention of a permanent or long lasting change in residence.

According to Skeldon ( 2012 ), the term “circular” implies a temporary movement that involves return. However, it is also distinct from “return migration”, as it implies more than just a single out-and-return movement to return at any time. Hugo ( 1982 ) further makes a distinction between commuting, defined as regular travel outside the village from 6 to 24 h, and circular migration, involving continuous but temporary absences of greater than 1 day.

Circularity includes migrants who adapt the seasonality of production and employment in their villages to that in the destination locations-whether rural or urban. It also includes those migrants who have acquired a certain fixity of location in urban spaces and also those whose location changes with workplaces and who, therefore, return to their native villages only when work opportunities are exhausted or when they themselves need to recuperate. A single label-seasonal or short term-eludes the circular migrants. Studies in most cases have focused either on short duration or seasonal migrants or those whose stay away from home have no temporal fixity, and who Breman in this issue describes as footloose workers or as modern day nomadism, which ensures that the workforce at the bottom of the economy, shorn off social security, and protection, can be bought at the lowest possible price and only hired for as long as their services. On the other hand, studies in the urban informal economy and in slums and similar habitations have often focused on the circular migrant who is struggling to put a foot in and find herself a niche in the urban economy and civic spaces.

Lucas ( 2015 ) in a review of internal migration globally points out that there is a neglect of seasonal and temporary migration globally. Such a neglect can have serious welfare and development implications for countries.

Long-term migrants in cities comprise either those who totally belong to the urban milieu or have largely extracted themselves from their rural roots. It also includes those who are semi-permanent residents in urban areas but still are linked to their rural habitat, with or without a desire to return to it permanently. Breman suggests that migrants who do not come back to the villages other than for short visits enjoy higher and steadier income, usually originate from castes-classes higher up in the village hierarchy, and are equipped with better physical and social capital. Survey results do not permit a very neat categorisation between different types of migrants. The National Sample Survey Organisation carried out a survey of migrants in 2007–2008. The survey allows us to distinguish between (in)-migrants, long-term outmigrants from households (away for more than a year), and short-term outmigrants (those who were away for work for a period of more than one month but less than six months). Results have shown that both (in)-migrants and long-term outmigrants who happen to be much more concentrated in better socio-economic groups than the short-term outmigrants who happen to be predominantly concentrated in lower consumption quintiles are from Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes or Other Backward Classes (Kundu and Sarangi 2007 ; Srivastava 2012 ). Yet, as discussed earlier the long-term outmigrants also form part of the precarious workforce in the informal urban economy (Srivastava 2020b ).

The migration of those at the bottom of the workforce which is less motivated by choice and search for better opportunity than by the dearth of livelihood opportunities in their home areas is very much a result of unequal development (Srivastava 2011b ; Srivastava et al. 2020b ) which has led to an empirical demarcation between sending states and receiving states. In fact, as shown in Srivastava ( 2020b , Table 8), states sending long-term migrants and short-term migrants largely overlap. As per the data from the 2011 Census and the NSS Survey on Migration (2007-2008), most outmigrants originate in a few low-income states and mostly travel to a handful of middle- or high-income states. The major source states are Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, Odisha, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, and Chhattisgarh, whereas the major destination states are Delhi, Haryana, and Punjab in the North (along with other areas in the Delhi National Capital Region), Maharashtra, Gujarat, and Goa in the West, and Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Kerala in the South. Recent studies also indicate that there is an increase in migration from the North-eastern states and towards the Southern states (see Lusome and Bhagat, and Peter et al. in this issue).

However, as Breman rightly observes in this issue, the contrast between home states (sending migrants) and host states (receiving migrants) is too simple and should not be reified. Gujarat happens to be a state of both in-migration and outmigration, and it is not the only one. Breman( 1996 ) and Breman ( 2009 ) show that the demand for outside labour is not necessarily caused by a lack of local supply and migrants are employed because they are cheaper and more docile. In fact, as shown in Srivastava ( 2020b ) a large amount of short-term outmigration emanates from within the high-income states.

At a more general level, one can ask whether such migration leads to an improvement in the condition of the individual and the household, and if so, in what way. Evidence shows that remittances lead to an improvement in consumption and decline in poverty, but effects are linked to the initial endowments of migrants and their current position in the labour market (Srivastava 2011a ). Bharti and Tripathi in this issue use the India Human Development Survey (IHDS) data for 2004-05 and 2011–2012 and analyse intergenerational mobility between father–son pairs, with and without remittances. They find no significant difference in the occupational mobility profile of the two types of households. Although this study is for all types of households, the results are likely to hold more for migrants at the bottom of the occupational ladder.

The seasonal, short duration, and footloose migrants have been analysed in a number of papers in this issue. The general conclusion is that these labourers are among the lowest substratum of workers, intensely exploited and denied a modicum of labour rights (Mishra; Breman; Adhikari et al. this issue), and changes in labour regulation have increased labour flexibility and non-standard employment without addressing issues of rights and dignity of labour, or the balance between capital and labour.

Breman, who has studied the footloose labour in Gujarat for over half a century, summarises his findings on footloose migrants as:

‘modern day nomadism, which ensures that the workforce at the bottom of the economy, shorn off social security, and protection, can be bought at the lowest possible price and only hired for as long as their services are required.

Class-wise, they can be clubbed as either semi-proletarians equipped with meagre and low yielding means of production (land, tools, cattle) or proletarians who are fully dispossessed from such ownership and at risk of even having forfeited control over where and when to apply their labour power. Their social profiles are structured on the basis of their primary identities defined by caste (Scheduled Castes or Dalits, Other Backward Classes); tribe (Scheduled Tribes or Adivasis) or creed (Hindus or Muslims). All these distinct clusters are further subdivided into a broad and stratified repertoire of hierarchical differentiation.

From day one, they are marked as outsiders lacking local language proficiency and familiarity with the alien habitat and its social intercourse.

A drift between their place of origin and the work that entices them away, labour nomads are not without assertiveness. However, it is a resilience that does not amount to a joint platform of protest and resistance.’

Mishra, in this issue, has analysed the unfreedom of seasonal labour migration from the rain-fed regions of three districts in interior Odisha, one of the low-income states of India. The paper historically traces the causes of dispossession of agrarian producers, ranging from land acquisition, peasant differentiation as agriculture commercialises, and rural distress and agrarian crisis. Rural labour that escapes distress is absorbed in an exploitative capitalist labour market through a network of social and economic structures which builds on the ethnicity, caste, gender, and tribal identity of the labourers. Capitalism uses these structures of discrimination to discipline and control labour. In the specific manifestations of migrant lives, the capitalist and non-/pre-capitalist forms of exploitation intersect and create conditions for “conjugated oppression” (Lerche and Shah, 2018 ).

The seasonal migration patterns in the study areas are quite diverse but dominated by inter-state family migration to brick kilns where migration is structured by the dadan system, in which advances given by sub-contractors or Sardars at around the festival of Nuakhali are used by labourers to settle old debts and defray current expenses. In return, labourers commit their labour, as a family unit, to work in the brick kilns, effectively bartering away their freedom and bargaining power. Overall, Mishra notes that despite some diversity, within and between the migration streams, there is a marked adverse inclusion, often characterised by unfreedom, of labourers at the bottom of the social and economic hierarchy, in capitalist production.

Bihar (along with Uttar Pradesh) has long been seen as the largest reservoir of migrant labour to many parts of the country. This migration again combines different streams and variations reflecting the initial social and economic endowment of the migrant’s household and individual characteristics. Dutta, in this issue, follows up on a long tradition of village and migration studies, initiated nearly five decades ago by a group of researchers working with the legendary researcher, Pradhan H. Prasad. (Of this research team, A. N. Sharma and Gerry Rodgers continue this research right till the present day.) Although secondary data suggest that Bihar contributes the most to short duration outmigration, Dutta finds that most of the outmigrants in her study are long-term migrants. The number of cases where entire households have relocated is low. While about one in five individuals migrated from two-third of the households, migration, especially among low-status social groups and agricultural labourers, was male dominated. Shorter-term migration streams were dominated by migrants from the poorest regions, and those at the bottom of the caste and class hierarchy, and these also constituted the most precarious migration streams. Again, while on average, migrants’ educational level was higher than non-migrants, migration streams at the bottom of the education spectrum were dominated by the most vulnerable social groups and poorest source regions. The person’s social and economic status was closely intertwined with the migration trajectory, and despite long periods of migration, most migrants continued to be in precarious jobs and enjoyed virtually no access to social protection entitlements at destination.

Uttarakhand, a mainly hilly state, with a long history of outmigration, was part of Uttar Pradesh till 2000. Awasthi and Mehta in this issue write about the background of migration from this state and then focus on the profile of a sample of migrants who had returned to the State after lockdown. Long-term circular outmigration from the region again far outweighed short-term outmigration, and in many cases, the former had partially been replaced by permanent outmigration, reducing many villages in the hills to the status of “ghost villages”. Turning to their survey of returnee migrants, they find that two-thirds had migrated to other states and nearly a similar proportion of all return migrants were recent migrants. A high, four-fifth of the returnees, were in regular wage/salaried jobs, while about a tenth each were self-employed or casual workers, but the salaried jobs were low skilled, low income, and informal, which ended as soon as lockdown started.

A number of papers in this issue analyse the conditions of migrant workers from the vantage point of receiving states and regions. The paper by Jayaram and Varma in this issue analyses the conditions of migrant workers industrialised Gujarat with a focus on two cities-Surat and Ahmedabad-and three sectors-construction, textiles, and hotels. In Ahmedabad, the textile value chain ended with women home-based workers who received a fraction of the minimum wage. The condition for male migrant workers in the small and medium units varied with scheduled caste migrant workers at the bottom of the ladder as helpers and contract workers having no possibility of upward mobility. Female workers earned even less than the male counterparts. Safety hazards were high, and scheduled tribe migrants were hired by the medium size units to do the most unsafe jobs. In Surat, 70 per cent of the powerloom workers were from Odisha working on piecerates on long shifts and when the powerlooms shut during the lockdown, many were stranded without wages. In the construction industry in Ahmedabad, workers were drawn from tribal areas within the state or from adjoining states, such as Rajasthan or Madhya Pradesh, through contractors, who paid them an advance. Again as lockdown struck, many workers were stuck without wages. Migrant women were often hired as jodis or couples - as 1.5 labour units, leading to a large gender wage gap and a lack of control over incomes. Women often delivered their infants on worksites, without basic facilities, and return to work within 15 days of their delivery (Jayaram et al. 2019 ). In the hotel industry, low-caste workers were generally employed in menial and insecure jobs. Under lockdown, workers immediately lost jobs and living spaces and left worksites with large wage arrears from contractors, who claimed that they were unable to recover wages from the hotel employers. Across the sectors, unsafe working conditions and poor living conditions, high congruence between work and social status, including gender, and a large role for contractors and intermediaries, were common features.

Maharashtra continues to be the largest major destination state for labour migrants. The paper by Singh et al. presents labour market characteristics in the organised construction industry in the urban economic agglomeration around the state capital, Mumbai. The construction industry also draws the highest number of circular/seasonal migrants - nearly 40 per cent of the total, according to NSS and IHDS estimates and employment in the industry grew at a remarkable rate between 1983 and 2011-2012 (Srivastava 2018 ). The industry employs a very high proportion of migrants and informal workers who are engaged through a dense system of sub-contracting, obfuscating the legal responsibility of employers towards the engaged workers. The paper tries to unpack the term “employer” by reflecting on the national level labour legislations, viz. the Inter-State Migrant Workers (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) (ISMW) Act, 1979, the Building and Other Construction Workers (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) (BOCW) Act, 1996 and the Contract Labour (Regulation and Abolition) Act, 1970 applicable to the construction sector, complemented with findings from fieldwork to provide a concrete understanding of the labour sub-contracting process. The perpetuation of the contracting system to engage migrants, the authors argue, is to provide employers with highly flexible and low cost labour, and the system evades regulation. The responsibilities under the laws are divided between the “contractor” and the “employer” and take no cognizance of the web of relationships.

Kerala, which has been a major source state for outmigration to other states as well as international destinations, has now emerged as a major and attractive destination state as a result of labour market characteristics and demographic changes. The state has also relatively the most proactive migration policies. Peter et.al. (this issue) estimate that the state is currently home to about 3.5 million circular migrants. The state began to see a heavy influx of migrant labour from the 1990s, and much of this was from beyond the neighbouring states, such as Tamil Nadu. Peter et al. present an analysis of the sectors engaging migrants and the emergence of long-distance corridors, with migrant labour coming to Kerala from the Eastern, Northern and North-Eastern states (Assam, Odisha, West Bengal, Bihar, Jharkhand, and Uttar Pradesh). They suggest that, like the rest of India, the temporary migrants belong to socially and educationally disadvantaged poor agrarian communities, whose livelihood opportunities in their native places have been severely constrained by a multitude of factors including climate change, disasters like drought and floods, conflicts, and oppression.

Kerala is one of the few states which has had proactive policy for labour migrants (Srivastava 2020c , Peter et al., this issue). Some of these measures date back to 2008. However, Peter et al. point out that the welfare schemes and regulatory framework had limited reach among the migrants. Collective bargaining largely eluded them, so that wages, although higher than other states, remained lower than local wages. There was also the “othering” of migrant labour, and even the “guest worker” label, which connoted the welcoming status being given to them, was an unfortunate extraction from international migration, where such workers acquired differentiated and lower rights compared to local workers. They further analyse the measures taken by the state for labour migrants during the lockdown. The state was impacted early by the pandemic and reduced economic activity forced a large number of migrants to return home from mid-March even before the lockdown. With lockdown, the government tried to meet the food-related challenges faced by the labour migrants, with the help of the local community setting up community kitchens, with partial success. Large-scale efforts were made to disseminate awareness about the pandemic among migrants in their languages. Many residential shelters were declared to be in situ shelters, and some new shelters were also set up. Government efforts were strongly supplemented by the community and civil society organisations (CSOs). The paper points out that Kerala's strong decentralised institutional set-up and disaster preparedness also equipped it to take steps arising out of pandemic-related crisis for migrants. But the state also made several mid-course corrections in dealing with the migrant crisis.

The North-Eastern states in India share international borders with Bangladesh, Myanmar, China, and Bhutan. Migration patterns in these states are complicated since these states are both source and destination states for internal as well as international (cross-border) migration. Lusome and Bhagat (in this issue) use Census and other sources of data to analyse patterns of internal migration in these states, and the impact of the pandemic on return migration. The paper also presents a rich texture of migration for states within the region.