The Value of Critical Thinking in Nursing

- How Nurses Use Critical Thinking

- How to Improve Critical Thinking

- Common Mistakes

Some experts describe a person’s ability to question belief systems, test previously held assumptions, and recognize ambiguity as evidence of critical thinking. Others identify specific skills that demonstrate critical thinking, such as the ability to identify problems and biases, infer and draw conclusions, and determine the relevance of information to a situation.

Nicholas McGowan, BSN, RN, CCRN, has been a critical care nurse for 10 years in neurological trauma nursing and cardiovascular and surgical intensive care. He defines critical thinking as “necessary for problem-solving and decision-making by healthcare providers. It is a process where people use a logical process to gather information and take purposeful action based on their evaluation.”

“This cognitive process is vital for excellent patient outcomes because it requires that nurses make clinical decisions utilizing a variety of different lenses, such as fairness, ethics, and evidence-based practice,” he says.

How Do Nurses Use Critical Thinking?

Successful nurses think beyond their assigned tasks to deliver excellent care for their patients. For example, a nurse might be tasked with changing a wound dressing, delivering medications, and monitoring vital signs during a shift. However, it requires critical thinking skills to understand how a difference in the wound may affect blood pressure and temperature and when those changes may require immediate medical intervention.

Nurses care for many patients during their shifts. Strong critical thinking skills are crucial when juggling various tasks so patient safety and care are not compromised.

Jenna Liphart Rhoads, Ph.D., RN, is a nurse educator with a clinical background in surgical-trauma adult critical care, where critical thinking and action were essential to the safety of her patients. She talks about examples of critical thinking in a healthcare environment, saying:

“Nurses must also critically think to determine which patient to see first, which medications to pass first, and the order in which to organize their day caring for patients. Patient conditions and environments are continually in flux, therefore nurses must constantly be evaluating and re-evaluating information they gather (assess) to keep their patients safe.”

The COVID-19 pandemic created hospital care situations where critical thinking was essential. It was expected of the nurses on the general floor and in intensive care units. Crystal Slaughter is an advanced practice nurse in the intensive care unit (ICU) and a nurse educator. She observed critical thinking throughout the pandemic as she watched intensive care nurses test the boundaries of previously held beliefs and master providing excellent care while preserving resources.

“Nurses are at the patient’s bedside and are often the first ones to detect issues. Then, the nurse needs to gather the appropriate subjective and objective data from the patient in order to frame a concise problem statement or question for the physician or advanced practice provider,” she explains.

Top 5 Ways Nurses Can Improve Critical Thinking Skills

We asked our experts for the top five strategies nurses can use to purposefully improve their critical thinking skills.

Case-Based Approach

Slaughter is a fan of the case-based approach to learning critical thinking skills.

In much the same way a detective would approach a mystery, she mentors her students to ask questions about the situation that help determine the information they have and the information they need. “What is going on? What information am I missing? Can I get that information? What does that information mean for the patient? How quickly do I need to act?”

Consider forming a group and working with a mentor who can guide you through case studies. This provides you with a learner-centered environment in which you can analyze data to reach conclusions and develop communication, analytical, and collaborative skills with your colleagues.

Practice Self-Reflection

Rhoads is an advocate for self-reflection. “Nurses should reflect upon what went well or did not go well in their workday and identify areas of improvement or situations in which they should have reached out for help.” Self-reflection is a form of personal analysis to observe and evaluate situations and how you responded.

This gives you the opportunity to discover mistakes you may have made and to establish new behavior patterns that may help you make better decisions. You likely already do this. For example, after a disagreement or contentious meeting, you may go over the conversation in your head and think about ways you could have responded.

It’s important to go through the decisions you made during your day and determine if you should have gotten more information before acting or if you could have asked better questions.

During self-reflection, you may try thinking about the problem in reverse. This may not give you an immediate answer, but can help you see the situation with fresh eyes and a new perspective. How would the outcome of the day be different if you planned the dressing change in reverse with the assumption you would find a wound infection? How does this information change your plan for the next dressing change?

Develop a Questioning Mind

McGowan has learned that “critical thinking is a self-driven process. It isn’t something that can simply be taught. Rather, it is something that you practice and cultivate with experience. To develop critical thinking skills, you have to be curious and inquisitive.”

To gain critical thinking skills, you must undergo a purposeful process of learning strategies and using them consistently so they become a habit. One of those strategies is developing a questioning mind. Meaningful questions lead to useful answers and are at the core of critical thinking .

However, learning to ask insightful questions is a skill you must develop. Faced with staff and nursing shortages , declining patient conditions, and a rising number of tasks to be completed, it may be difficult to do more than finish the task in front of you. Yet, questions drive active learning and train your brain to see the world differently and take nothing for granted.

It is easier to practice questioning in a non-stressful, quiet environment until it becomes a habit. Then, in the moment when your patient’s care depends on your ability to ask the right questions, you can be ready to rise to the occasion.

Practice Self-Awareness in the Moment

Critical thinking in nursing requires self-awareness and being present in the moment. During a hectic shift, it is easy to lose focus as you struggle to finish every task needed for your patients. Passing medication, changing dressings, and hanging intravenous lines all while trying to assess your patient’s mental and emotional status can affect your focus and how you manage stress as a nurse .

Staying present helps you to be proactive in your thinking and anticipate what might happen, such as bringing extra lubricant for a catheterization or extra gloves for a dressing change.

By staying present, you are also better able to practice active listening. This raises your assessment skills and gives you more information as a basis for your interventions and decisions.

Use a Process

As you are developing critical thinking skills, it can be helpful to use a process. For example:

- Ask questions.

- Gather information.

- Implement a strategy.

- Evaluate the results.

- Consider another point of view.

These are the fundamental steps of the nursing process (assess, diagnose, plan, implement, evaluate). The last step will help you overcome one of the common problems of critical thinking in nursing — personal bias.

Common Critical Thinking Pitfalls in Nursing

Your brain uses a set of processes to make inferences about what’s happening around you. In some cases, your unreliable biases can lead you down the wrong path. McGowan places personal biases at the top of his list of common pitfalls to critical thinking in nursing.

“We all form biases based on our own experiences. However, nurses have to learn to separate their own biases from each patient encounter to avoid making false assumptions that may interfere with their care,” he says. Successful critical thinkers accept they have personal biases and learn to look out for them. Awareness of your biases is the first step to understanding if your personal bias is contributing to the wrong decision.

New nurses may be overwhelmed by the transition from academics to clinical practice, leading to a task-oriented mindset and a common new nurse mistake ; this conflicts with critical thinking skills.

“Consider a patient whose blood pressure is low but who also needs to take a blood pressure medication at a scheduled time. A task-oriented nurse may provide the medication without regard for the patient’s blood pressure because medication administration is a task that must be completed,” Slaughter says. “A nurse employing critical thinking skills would address the low blood pressure, review the patient’s blood pressure history and trends, and potentially call the physician to discuss whether medication should be withheld.”

Fear and pride may also stand in the way of developing critical thinking skills. Your belief system and worldview provide comfort and guidance, but this can impede your judgment when you are faced with an individual whose belief system or cultural practices are not the same as yours. Fear or pride may prevent you from pursuing a line of questioning that would benefit the patient. Nurses with strong critical thinking skills exhibit:

- Learn from their mistakes and the mistakes of other nurses

- Look forward to integrating changes that improve patient care

- Treat each patient interaction as a part of a whole

- Evaluate new events based on past knowledge and adjust decision-making as needed

- Solve problems with their colleagues

- Are self-confident

- Acknowledge biases and seek to ensure these do not impact patient care

An Essential Skill for All Nurses

Critical thinking in nursing protects patient health and contributes to professional development and career advancement. Administrative and clinical nursing leaders are required to have strong critical thinking skills to be successful in their positions.

By using the strategies in this guide during your daily life and in your nursing role, you can intentionally improve your critical thinking abilities and be rewarded with better patient outcomes and potential career advancement.

Frequently Asked Questions About Critical Thinking in Nursing

How are critical thinking skills utilized in nursing practice.

Nursing practice utilizes critical thinking skills to provide the best care for patients. Often, the patient’s cause of pain or health issue is not immediately clear. Nursing professionals need to use their knowledge to determine what might be causing distress, collect vital information, and make quick decisions on how best to handle the situation.

How does nursing school develop critical thinking skills?

Nursing school gives students the knowledge professional nurses use to make important healthcare decisions for their patients. Students learn about diseases, anatomy, and physiology, and how to improve the patient’s overall well-being. Learners also participate in supervised clinical experiences, where they practice using their critical thinking skills to make decisions in professional settings.

Do only nurse managers use critical thinking?

Nurse managers certainly use critical thinking skills in their daily duties. But when working in a health setting, anyone giving care to patients uses their critical thinking skills. Everyone — including licensed practical nurses, registered nurses, and advanced nurse practitioners —needs to flex their critical thinking skills to make potentially life-saving decisions.

Meet Our Contributors

Crystal Slaughter, DNP, APRN, ACNS-BC, CNE

Crystal Slaughter is a core faculty member in Walden University’s RN-to-BSN program. She has worked as an advanced practice registered nurse with an intensivist/pulmonary service to provide care to hospitalized ICU patients and in inpatient palliative care. Slaughter’s clinical interests lie in nursing education and evidence-based practice initiatives to promote improving patient care.

Jenna Liphart Rhoads, Ph.D., RN

Jenna Liphart Rhoads is a nurse educator and freelance author and editor. She earned a BSN from Saint Francis Medical Center College of Nursing and an MS in nursing education from Northern Illinois University. Rhoads earned a Ph.D. in education with a concentration in nursing education from Capella University where she researched the moderation effects of emotional intelligence on the relationship of stress and GPA in military veteran nursing students. Her clinical background includes surgical-trauma adult critical care, interventional radiology procedures, and conscious sedation in adult and pediatric populations.

Nicholas McGowan, BSN, RN, CCRN

Nicholas McGowan is a critical care nurse with 10 years of experience in cardiovascular, surgical intensive care, and neurological trauma nursing. McGowan also has a background in education, leadership, and public speaking. He is an online learner who builds on his foundation of critical care nursing, which he uses directly at the bedside where he still practices. In addition, McGowan hosts an online course at Critical Care Academy where he helps nurses achieve critical care (CCRN) certification.

Probing the Relationship Between Evidence-Based Practice Implementation Models and Critical Thinking in Applied Nursing Practice

- PMID: 27031030

- DOI: 10.3928/00220124-20160322-05

HOW TO OBTAIN CONTACT HOURS BY READING THIS ISSUE Instructions: 1.2 contact hours will be awarded by Villanova University College of Nursing upon successful completion of this activity. A contact hour is a unit of measurement that denotes 60 minutes of an organized learning activity. This is a learner-based activity. Villanova University College of Nursing does not require submission of your answers to the quiz. A contact hour certificate will be awarded after you register, pay the registration fee, and complete the evaluation form online at http://goo.gl/gMfXaf. In order to obtain contact hours you must: 1. Read the article, "Probing the Relationship Between Evidence-Based Practice Implementation Models and Critical Thinking in Applied Nursing Practice," found on pages 161-168, carefully noting any tables and other illustrative materials that are included to enhance your knowledge and understanding of the content. Be sure to keep track of the amount of time (number of minutes) you spend reading the article and completing the quiz. 2. Read and answer each question on the quiz. After completing all of the questions, compare your answers to those provided within this issue. If you have incorrect answers, return to the article for further study. 3. Go to the Villanova website to register for contact hour credit. You will be asked to provide your name, contact information, and a VISA, MasterCard, or Discover card number for payment of the $20.00 fee. Once you complete the online evaluation, a certificate will be automatically generated. This activity is valid for continuing education credit until March 31, 2019. CONTACT HOURS This activity is co-provided by Villanova University College of Nursing and SLACK Incorporated. Villanova University College of Nursing is accredited as a provider of continuing nursing education by the American Nurses Credentialing Center's Commission on Accreditation.

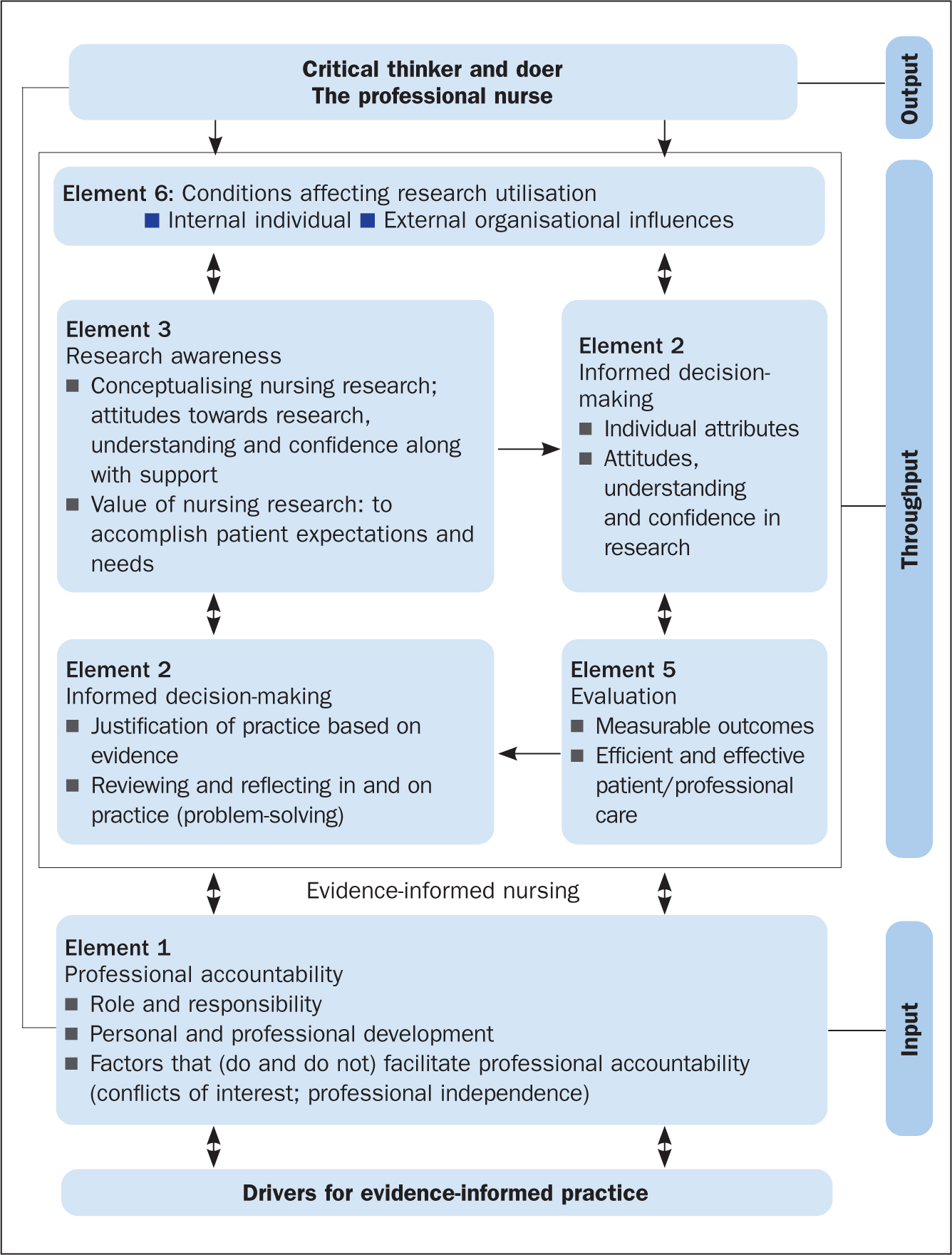

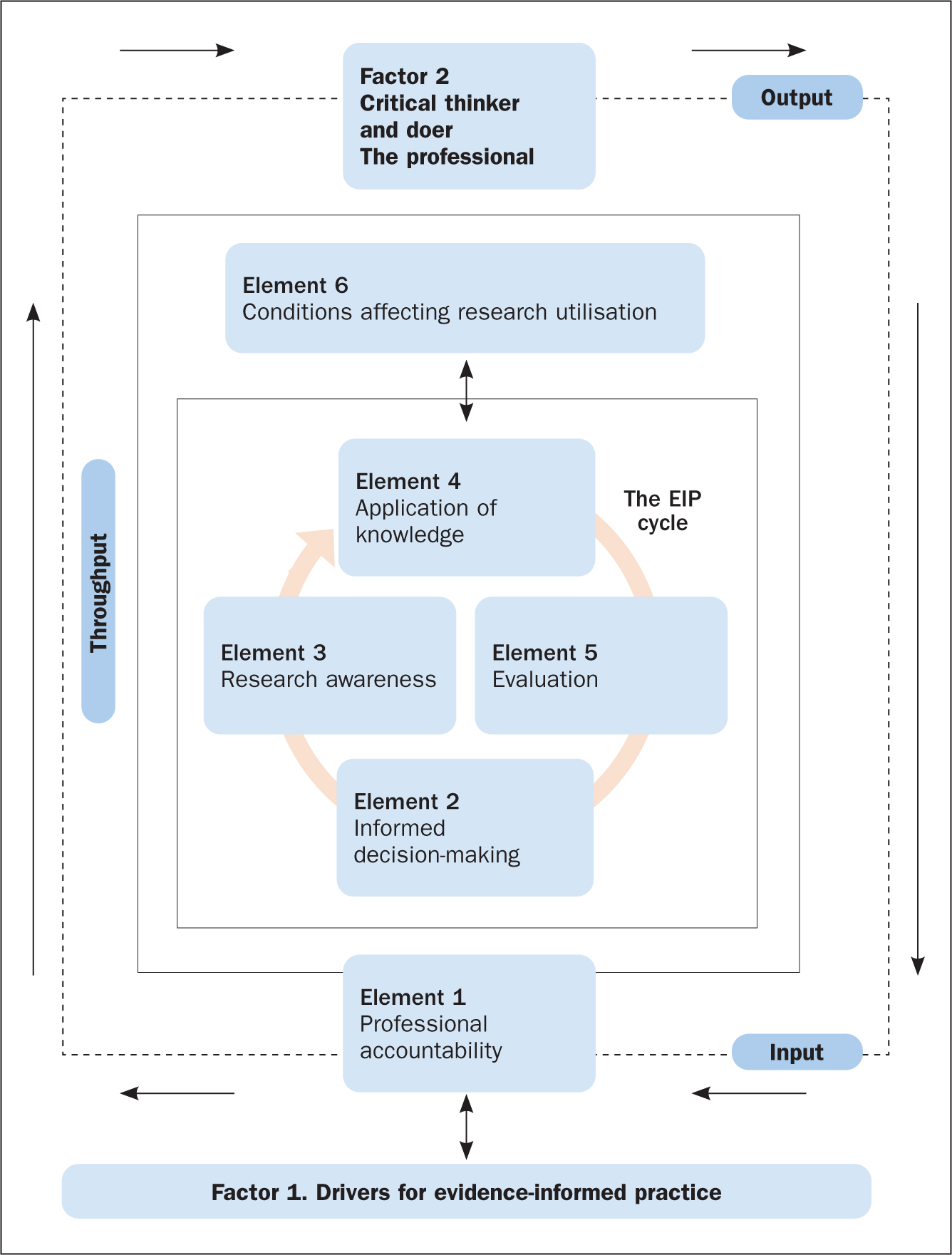

Objectives: • Describe the key components and characteristics related to evidence-based practice and critical thinking. • Identify the relationship between evidence-based practice and critical thinking. DISCLOSURE STATEMENT Neither the planners nor the author have any conflicts of interest to disclose. Evidence-based practice is not a new concept to the profession of nursing, yet its application and sustainability is inconsistent in nursing practice. Despite the expansion of efforts to teach evidence-based practice and practically apply evidence at the bedside, a research-practice gap still exists. Several critical factors contribute to the successful application of evidence into practice, including critical thinking. The purpose of this article is to discuss the relationship between critical thinking and the current evidence-based practice implementation models. Understanding this relationship will help nurse educators and clinicians in cultivating critical thinking skills in nursing staff to most effectively apply evidence at the bedside. Critical thinking is a key element and is essential to the learning and implementation of evidence-based practice, as demonstrated by its integration into evidence-based practice implementation models.

Copyright 2016, SLACK Incorporated.

- Attitude of Health Personnel

- Clinical Competence*

- Education, Nursing, Continuing / organization & administration*

- Evidence-Based Nursing / education*

- Models, Nursing

- Nursing Education Research

- Nursing Staff, Hospital / education*

- United States

Promoting critical thinking through an evidence-based skills fair intervention

Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning

ISSN : 2397-7604

Article publication date: 23 November 2020

Issue publication date: 1 April 2022

The lack of critical thinking in new graduates has been a concern to the nursing profession. The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of an innovative, evidence-based skills fair intervention on nursing students' achievements and perceptions of critical thinking skills development.

Design/methodology/approach

The explanatory sequential mixed-methods design was employed for this study.

The findings indicated participants perceived the intervention as a strategy for developing critical thinking.

Originality/value

The study provides educators helpful information in planning their own teaching practice in educating students.

Critical thinking

Evidence-based practice, skills fair intervention.

Gonzalez, H.C. , Hsiao, E.-L. , Dees, D.C. , Noviello, S.R. and Gerber, B.L. (2022), "Promoting critical thinking through an evidence-based skills fair intervention", Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning , Vol. 15 No. 1, pp. 41-54. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIT-08-2020-0041

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2020, Heidi C. Gonzalez, E-Ling Hsiao, Dianne C. Dees, Sherri R. Noviello and Brian L. Gerber

Published in Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning . Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

Introduction

Critical thinking (CT) was defined as “cognitive skills of analyzing, applying standards, discriminating, information seeking, logical reasoning, predicting, and transforming knowledge” ( Scheffer and Rubenfeld, 2000 , p. 357). Critical thinking is the basis for all professional decision-making ( Moore, 2007 ). The lack of critical thinking in student nurses and new graduates has been a concern to the nursing profession. It would negatively affect the quality of service and directly relate to the high error rates in novice nurses that influence patient safety ( Arli et al. , 2017 ; Saintsing et al. , 2011 ). It was reported that as many as 88% of novice nurses commit medication errors with 30% of these errors due to a lack of critical thinking ( Ebright et al. , 2004 ). Failure to rescue is another type of error common for novice nurses, reported as high as 37% ( Saintsing et al. , 2011 ). The failure to recognize trends or complications promptly or take action to stabilize the patient occurs when health-care providers do not recognize signs and symptoms of the early warnings of distress ( Garvey and CNE series, 2015 ). Internationally, this lack of preparedness and critical thinking attributes to the reported 35–60% attrition rate of new graduate nurses in their first two years of practice ( Goodare, 2015 ). The high attrition rate of new nurses has expensive professional and economic costs of $82,000 or more per nurse and negatively affects patient care ( Twibell et al. , 2012 ). Facione and Facione (2013) reported the failure to utilize critical thinking skills not only interferes with learning but also results in poor decision-making and unclear communication between health-care professionals, which ultimately leads to patient deaths.

Due to the importance of critical thinking, many nursing programs strive to infuse critical thinking into their curriculum to better prepare graduates for the realities of clinical practice that involves ever-changing, complex clinical situations and bridge the gap between education and practice in nursing ( Benner et al. , 2010 ; Kim et al. , 2019 ; Park et al. , 2016 ; Newton and Moore, 2013 ; Nibert, 2011 ). To help develop students' critical thinking skills, nurse educators must change the way they teach nursing, so they can prepare future nurses to be effective communicators, critical thinkers and creative problem solvers ( Rieger et al. , 2015 ). Nursing leaders also need to redefine teaching practice and educational guidelines that drive innovation in undergraduate nursing programs.

Evidence-based practice has been advocated to promote critical thinking and help reduce the research-practice gap ( Profetto-McGrath, 2005 ; Stanley and Dougherty, 2010 ). Evidence-based practice was defined as “the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of the individual patient” ( Sackett et al. , 1996 , p. 71). Skills fair intervention, one type of evidence-based practice, can be used to engage students, promote active learning and develop critical thinking ( McCausland and Meyers, 2013 ; Roberts et al. , 2009 ). Skills fair intervention helps promote a consistent teaching practice of the psychomotor skills to the novice nurse that decreased anxiety, gave clarity of expectations to the students in the clinical setting and increased students' critical thinking skills ( Roberts et al. , 2009 ). The researchers of this study had an opportunity to create an active, innovative skills fair intervention for a baccalaureate nursing program in one southeastern state. This intervention incorporated evidence-based practice rationale with critical thinking prompts using Socratic questioning, evidence-based practice videos to the psychomotor skill rubrics, group work, guided discussions, expert demonstration followed by guided practice and blended learning in an attempt to promote and develop critical thinking in nursing students ( Hsu and Hsieh, 2013 ; Oermann et al. , 2011 ; Roberts et al. , 2009 ). The effects of an innovative skills fair intervention on senior baccalaureate nursing students' achievements and their perceptions of critical thinking development were examined in the study.

Literature review

The ability to use reasoned opinion focusing equally on processes and outcomes over emotions is called critical thinking ( Paul and Elder, 2008 ). Critical thinking skills are desired in almost every discipline and play a major role in decision-making and daily judgments. The roots of critical thinking date back to Socrates 2,500 years ago and can be traced to the ancient philosopher Aristotle ( Paul and Elder, 2012 ). Socrates challenged others by asking inquisitive questions in an attempt to challenge their knowledge. In the 1980s, critical thinking gained nationwide recognition as a behavioral science concept in the educational system ( Robert and Petersen, 2013 ). Many researchers in both education and nursing have attempted to define, measure and teach critical thinking for decades. However, a theoretical definition has yet to be accepted and established by the nursing profession ( Romeo, 2010 ). The terms critical literacy, CT, reflective thinking, systems thinking, clinical judgment and clinical reasoning are used synonymously in the reviewed literature ( Clarke and Whitney, 2009 ; Dykstra, 2008 ; Jones, 2010 ; Swing, 2014 ; Turner, 2005 ).

Watson and Glaser (1980) viewed critical thinking not only as cognitive skills but also as a combination of skills, knowledge and attitudes. Paul (1993) , the founder of the Foundation for Critical Thinking, offered several definitions of critical thinking and identified three essential components of critical thinking: elements of thought, intellectual standards and affective traits. Brunt (2005) stated critical thinking is a process of being practical and considered it to be “the process of purposeful thinking and reflective reasoning where practitioners examine ideas, assumptions, principles, conclusions, beliefs, and actions in the contexts of nursing practice” (p. 61). In an updated definition, Ennis (2011) described critical thinking as, “reasonable reflective thinking focused on deciding what to believe or do” (para. 1).

The most comprehensive attempt to define critical thinking was under the direction of Facione and sponsored by the American Philosophical Association ( Scheffer and Rubenfeld, 2000 ). Facione (1990) surveyed 53 experts from the arts and sciences using the Delphi method to define critical thinking as a “purposeful, self-regulatory judgment which results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference, as well as an explanation of the evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or contextual considerations upon which judgment, is based” (p. 2).

To come to a consensus definition for critical thinking, Scheffer and Rubenfeld (2000) also conducted a Delphi study. Their study consisted of an international panel of nurses who completed five rounds of sequenced questions to arrive at a consensus definition. Critical thinking was defined as “habits of mind” and “cognitive skills.” The elements of habits of mind included “confidence, contextual perspective, creativity, flexibility, inquisitiveness, intellectual integrity, intuition, open-mindedness, perseverance, and reflection” ( Scheffer and Rubenfeld, 2000 , p. 352). The elements of cognitive skills were recognized as “analyzing, applying standards, discriminating, information seeking, logical reasoning, predicting, and transforming knowledge” ( Scheffer and Rubenfeld, 2000 , p. 352). In addition, Ignatavicius (2001) defined the development of critical thinking as a long-term process that must be practiced, nurtured and reinforced over time. Ignatavicius believed that a critical thinker required six cognitive skills: interpretation, analysis, evaluation, inference, explanation and self-regulation ( Chun-Chih et al. , 2015 ). According to Ignatavicius (2001) , the development of critical thinking is difficult to measure or describe because it is a formative rather than summative process.

Fero et al. (2009) noted that patient safety might be compromised if a nurse cannot provide clinically competent care due to a lack of critical thinking. The Institute of Medicine (2001) recommended five health care competencies: patient-centered care, interdisciplinary team care, evidence-based practice, informatics and quality improvement. Understanding the development and attainment of critical thinking is the key for gaining these future competencies ( Scheffer and Rubenfeld, 2000 ). The development of a strong scientific foundation for nursing practice depends on habits such as contextual perspective, inquisitiveness, creativity, analysis and reasoning skills. Therefore, the need to better understand how these critical thinking habits are developed in nursing students needs to be explored through additional research ( Fero et al. , 2009 ). Despite critical thinking being listed since the 1980s as an accreditation outcome criteria for baccalaureate programs by the National League for Nursing, very little improvement has been observed in practice ( McMullen and McMullen, 2009 ). James (2013) reported the number of patient harm incidents associated with hospital care is much higher than previously thought. James' study indicated that between 210,000 and 440,000 patients each year go to the hospital for care and end up suffering some preventable harm that contributes to their death. James' study of preventable errors is attributed to other sources besides nursing care, but having a nurse in place who can advocate and critically think for patients will make a positive impact on improving patient safety ( James, 2013 ; Robert and Peterson, 2013 ).

Adopting teaching practice to promote CT is a crucial component of nursing education. Research by Nadelson and Nadelson (2014) suggested evidence-based practice is best learned when integrated into multiple areas of the curriculum. Evidence-based practice developed its roots through evidence-based medicine, and the philosophical origins extend back to the mid-19th century ( Longton, 2014 ). Florence Nightingale, the pioneer of modern nursing, used evidence-based practice during the Crimean War when she recognized a connection between poor sanitary conditions and rising mortality rates of wounded soldiers ( Rahman and Applebaum, 2011 ). In professional nursing practice today, a commonly used definition of evidence-based practice is derived from Dr. David Sackett: the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of the individual patient ( Sackett et al. , 1996 , p. 71). As professional nurses, it is imperative for patient safety to remain inquisitive and ask if the care provided is based on available evidence. One of the core beliefs of the American Nephrology Nurses' Association's (2019) 2019–2020 Strategic Plan is “Anna must support research to develop evidence-based practice, as well as to advance nursing science, and that as individual members, we must support, participate in, and apply evidence-based research that advances our own skills, as well as nursing science” (p. 1). Longton (2014) reported the lack of evidence-based practice in nursing resulted in negative outcomes for patients. In fact, when evidence-based practice was implemented, changes in policies and procedures occurred that resulted in decreased reports of patient harm and associated health-care costs. The Institute of Medicine (2011) recommendations included nurses being leaders in the transformation of the health-care system and achieving higher levels of education that will provide the ability to critically analyze data to improve the quality of care for patients. Student nurses must be taught to connect and integrate CT and evidence-based practice throughout their program of study and continue that practice throughout their careers.

One type of evidence-based practice that can be used to engage students, promote active learning and develop critical thinking is skills fair intervention ( McCausland and Meyers, 2013 ; Roberts et al. , 2009 ). Skills fair intervention promoted a consistent teaching approach of the psychomotor skills to the novice nurse that decreased anxiety, gave clarity of expectations to the students in the clinical setting and increased students' critical thinking skills ( Roberts et al. , 2009 ). The skills fair intervention used in this study is a teaching strategy that incorporated CT prompts, Socratic questioning, group work, guided discussions, return demonstrations and blended learning in an attempt to develop CT in nursing students ( Hsu and Hsieh, 2013 ; Roberts et al. , 2009 ). It melded evidence-based practice with simulated CT opportunities while students practiced essential psychomotor skills.

Research methodology

Context – skills fair intervention.

According to Roberts et al. (2009) , psychomotor skills decline over time even among licensed experienced professionals within as little as two weeks and may need to be relearned within two months without performing a skill. When applying this concept to student nurses for whom each skill is new, it is no wonder their competency result is diminished after having a summer break from nursing school. This skills fair intervention is a one-day event to assist baccalaureate students who had taken the summer off from their studies in nursing and all faculty participated in operating the stations. It incorporated evidence-based practice rationale with critical thinking prompts using Socratic questioning, evidence-based practice videos to the psychomotor skill rubrics, group work, guided discussions, expert demonstration followed by guided practice and blended learning in an attempt to promote and develop critical thinking in baccalaureate students.

Students were scheduled and placed randomly into eight teams based on attributes of critical thinking as described by Wittmann-Price (2013) : Team A – Perseverance, Team B – Flexibility, Team C – Confidence, Team D – Creativity, Team E – Inquisitiveness, Team F – Reflection, Team G – Analyzing and Team H – Intuition. The students rotated every 20 minutes through eight stations: Medication Administration: Intramuscular and Subcutaneous Injections, Initiating Intravenous Therapy, ten-minute Focused Physical Assessment, Foley Catheter Insertion, Nasogastric Intubation, Skin Assessment/Braden Score and Restraints, Vital Signs and a Safety Station. When the students completed all eight stations, they went to the “Check-Out” booth to complete a simple evaluation to determine their perceptions of the effectiveness of the innovative intervention. When the evaluations were complete, each of the eight critical thinking attribute teams placed their index cards into a hat, and a student won a small prize. All Junior 2, Senior 1 and Senior 2 students were required to attend the Skills Fair. The Skills Fair Team strove to make the event as festive as possible, engaging nursing students with balloons, candy, tri-boards, signs and fun pre and postactivities. The Skills Fair rubrics, scheduling and instructions were shared electronically with students and faculty before the skills fair intervention to ensure adequate preparation and continuous resource availability as students move forward into their future clinical settings.

Research design

Institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained from XXX University to conduct this study and protect human subject rights. The explanatory sequential mixed-methods design was employed for this study. The design was chosen to identify what effects a skills fair intervention that had on senior baccalaureate nursing students' achievements on the Kaplan Critical Thinking Integrated Test (KCTIT) and then follow up with individual interviews to explore those test results in more depth. In total, 52 senior nursing students completed the KCTIT; 30 of them participated in the skills fair intervention and 22 of them did not participate. The KCTIT is a computerized 85-item exam in which 85 equates to 100%, making each question worth one point. It has high reliability and validity ( Kaplan Nursing, 2012 ; Swing, 2014 ). The reliability value of the KCTIT ranged from 0.72 to 0.89. A t -test was used to analyze the test results.

A total of 11 participants were purposefully selected based on a range of six high achievers and five low achievers on the KCTIT for open-ended one-on-one interviews. Each interview was conducted individually and lasted for about 60 minutes. An open-ended interview protocol was used to guide the flow of data collection. The interviewees' ages ranged from 21 to 30 years, with an average of 24 years. One of 11 interviewees was male. Among them, seven were White, three were Black and one was Indian American. The data collected were used to answer the following research questions: (1) What was the difference in achievements on the KCTIT among senior baccalaureate nursing students who participated in the skills fair intervention and students who did not participate? (2) What were the senior baccalaureate nursing students' perceptions of internal and external factors impacting the development of critical thinking skills during the skills fair intervention? and (3) What were the senior baccalaureate nursing students' perceptions of the skills fair intervention as a critical thinking developmental strategy?

Inductive content analysis was used to analyze interview data by starting with the close reading of the transcripts and writing memos for initial coding, followed by an analysis of patterns and relationships among the data for focused coding. The intercoder reliability was established for qualitative data analysis with a nursing expert. The lead researcher and the expert read the transcript several times and assigned a code to significant units of text that corresponded with answering the research questions. The codes were compared based on differences and similarities and sorted into subcategories and categories. Then, headings and subheadings were used based on similar comments to develop central themes and patterns. The process of establishing intercoder reliability helped to increase dependability, conformability and credibility of the findings ( Graneheim and Lundman, 2004 ). In addition, methods of credibility, confirmability, dependability and transferability were applied to increase the trustworthiness of this study ( Graneheim and Lundman, 2004 ). First, reflexivity was observed by keeping journals and memos. This practice allowed the lead researcher to reflect on personal views to minimize bias. Data saturation was reached through following the recommended number of participants as well as repeated immersion in the data during analysis until no new data surfaced. Member checking was accomplished through returning the transcript and the interpretation to the participants to check the accuracy and truthfulness of the findings. Finally, proper documentation was conducted to allow accurate crossreferencing throughout the study.

Quantitative results

Results for the quantitative portion showed there was no difference in scores on the KCTIT between senior nursing students who participated in the skills fair intervention and senior nursing students who did not participate, t (50) = −0.174, p = 0.86 > 0.05. The test scores between the nonparticipant group ( M = 67.59, SD = 5.81) and the participant group ( M = 67.88, SD = 5.99) were almost equal.

Qualitative results

Initial coding.

The results from the initial coding and generated themes are listed in Table 1 . First, the participants perceived the skills fair intervention as “promoting experience” and “confidence” by practicing previously learned knowledge and reinforcing it with active learning strategies. Second, the participants perceived the skills fair intervention as a relaxed, nonthreatening learning environment due to the festive atmosphere, especially in comparison to other learning experiences in the nursing program. The nonthreatening environment of the skills fair intervention allowed students to learn without fear. Third, the majority of participants believed their critical thinking was strengthened after participating. Several participants believed their perception of critical thinking was “enhanced” or “reinforced” rather than significantly changed.

Focused coding results

The final themes were derived from the analysis of patterns and relationships among the content of the data using inductive content analysis ( Saldana, 2009 ). The following was examined across the focused coding process: (1) factors impacting critical thinking skills development during skills fair intervention and (2) skills fair intervention a critical thinking skills developmental strategy.

Factors impacting critical thinking skills development . The factors impacting the development of critical thinking during the skills fair intervention were divided into two themes: internal factors and external factors. The internal factors were characteristics innate to the students. The identified internal factors were (1) confidence and anxiety levels, (2) attitude and (3) age. The external factors were the outside influences that affected the students. The external factors were (1) experience and practice, (2) faculty involvement, (3) positive learning environment and (4) faculty prompts.

I think that confidence and anxiety definitely both have a huge impact on your ability to be able to really critically think. If you start getting anxious and panicking you cannot think through the process like you need too. I do not really think gender or age necessarily would have anything to do with critical thinking.

Definitely the confidence level, I think, the more advanced you get in the program, your confidence just keeps on growing. Level of anxiety, definitely… I think the people who were in the Skills Fair for the first time, had more anxiety because they did not really know to think, they did not know how strict it was going to be, or if they really had to know everything by the book. I think the Skills Fair helped everyone's confidence levels, but especially the Jr. 2's.

Attitude was an important factor in the development of critical thinking skills during the skills fair intervention as participants believed possessing a pleasant and positive attitude meant a student was eager to learn, participate, accept responsibility for completing duties and think seriously. Participant 6 believed attitude contributed to performance in the Skills Fair.

I feel like, certain things bring critical thinking out in you. And since I'm a little bit older than some of the other students, I have had more life experiences and am able to figure stuff out better. Older students have had more time to learn by trial and error, and this and that.

Like when I had clinical with you, you'd always tell us to know our patients' medications. To always know and be prepared to answer questions – because at first as a Junior 1 we did not do that in the clinical setting… and as a Junior 2, I did not really have to know my medications, but with you as a Senior 1, I started to realize that the patients do ask about their meds, so I was making sure that I knew everything before they asked it. And just having more practice with IVs – at first, I was really nervous, but when I got to my preceptorship – I had done so many IVs and with all of the practice, it just built up my confidence with that skill so when I performed that skill during the Fair, I was confident due to my clinical experiences and able to think and perform better.

I think teachers will always affect the ability to critically think just because you want [to] get the right answer because they are there and you want to seem smart to them [Laugh]. Also, if you are leading in the wrong direction of your thinking – they help steer you back to [in] the right direction so I think that was very helpful.

You could tell the faculty really tried to make it more laid back and fun, so everybody would have a good experience. The faculty had a good attitude. I think making it fun and active helped keep people positive. You know if people are negative and not motivated, nothing gets accomplished. The faculty did an amazing job at making the Skills Fair a positive atmosphere.

However, for some of the participants, a positive learning environment depended on their fellow students. The students were randomly assigned alphabetically to groups, and the groups were assigned to starting stations at the Skills Fair. The participants claimed some students did not want to participate and displayed cynicism toward the intervention. The participants believed their cynicism affected the positive learning environment making critical thinking more difficult during the Skills Fair.

Okay, when [instructor name] was demonstrating the Chevron technique right after we inserted the IV catheter and we were trying to secure the catheter, put on the extension set, and flush the line at what seemed to be all at the same time. I forgot about how you do not want to put the tape right over the hub of the catheter because when you go back in and try to assess the IV site – you're trying to assess whether or not it is patent or infiltrated – you have to visualize the insertion site. That was one of the things that I had been doing wrong because I was just so excited that I got the IV in the vein in the first place – that I did not think much about the tape or the tegaderm for sterility. So I think an important part of critical thinking is to be able to recognize when you've made a mistake and stop, stop yourself from doing it in the future (see Table 2 ).

Skills fair intervention as a developmental strategy for critical thinking . The participants identified the skills fair intervention was effective as a developmental strategy for critical thinking, as revealed in two themes: (1) develops alternative thinking and (2) thinking before doing (See Table 3 ).

Develops alternative thinking . The participants perceived the skills fair intervention helped enhance critical thinking and confidence by developing alternative thinking. Alternative thinking was described as quickly thinking of alternative solutions to problems based on the latest evidence and using that information to determine what actions were warranted to prevent complications and prevent injury. It helped make better connections through the learning of rationale between knowledge and skills and then applying that knowledge to prevent complications and errors to ensure the safety of patients. The participants stated the learning of rationale for certain procedures provided during the skills fair intervention such as the evidence and critical thinking prompts included in the rubrics helped reinforce this connection. The participants also shared they developed alternative thinking after participating in the skills fair intervention by noticing trends in data to prevent potential complications from the faculty prompts. Participant 1 stated her instructor prompted her alternative thinking through questioning about noticing trends to prevent potential complications. She said the following:

Another way critical thinking occurred during the skills fair was when [instructor name] was teaching and prompted us about what it would be like to care for a patient with a fractured hip – I think this was at the 10-minute focused assessment station, but I could be wrong. I remember her asking, “What do you need to be on the look-out for? What can go wrong?” I automatically did not think critically very well and was only thinking circulation in the leg, dah, dah, dah. But she was prompting us to think about mobility alterations and its effect on perfusion and oxygenation. She was trying to help us build those connections. And I think that's a lot of the aspects of critical thinking that gets overlooked with the nursing student – trouble making connections between our knowledge and applying it in practice.

Thinking before doing . The participants perceived thinking before doing, included thinking of how and why certain procedures, was necessary through self-examination prior to taking action. The hands-on situational learning allowed the participants in the skills fair intervention to better notice assessment data and think at a higher level as their previous learning of the skills was perceived as memorization of steps. This higher level of learning allowed participants to consider different future outcomes and analyze pertinent data before taking action.

I think what helped me the most is considering outcomes of my actions before I do anything. For instance, if you're thinking, “Okay. Well, I need to check their blood pressure before I administer this blood pressure medication – or the blood pressure could potentially bottom out.” I really do not want my patient to bottom out and get hypotensive because I administered a medication that was ordered, but not safe to give. I could prevent problems from happening if I know what to be on alert for and act accordingly. So ultimately knowing that in the clinical setting, I can prevent complications from happening and I save myself, my license, and promote patient safety. I think knowing that I've seen the importance of critical thinking already in practice has helped me value and understand why I should be critically thinking. Yes, we use the 5-rights of medication safety – but we also have to think. For instance, if I am going to administer insulin – what do I need to know or do to give this safely? What is the current blood sugar? Has the patient been eating? When is the next meal scheduled? Is the patient NPO for a procedure? Those are examples of questions to consider and the level of thinking that needs to take place prior to taking actions in the clinical setting.

Although the results of quantitative data showed no significant difference in scores on the KCTIT between the participant and nonparticipant groups, during the interviews some participants attributed this result to the test not being part of a course grade and believed students “did not try very hard to score well.” However, the participants who attended interviews did identify the skills fair intervention as a developmental strategy for critical thinking by helping them develop alternative thinking and thinking before doing. The findings are supported in the literature as (1) nurses must recognize signs of clinical deterioration and take action promptly to prevent potential complications ( Garvey and CNE series 2015 ) and (2) nurses must analyze pertinent data and consider all possible solutions before deciding on the most appropriate action for each patient ( Papathanasiou et al. , 2014 ).

The skills fair intervention also enhanced the development of self-confidence by participants practicing previously learned skills in a controlled, safe environment. The nonthreatening environment of the skills fair intervention allowed students to learn without fear and the majority of participants believed their critical thinking was strengthened after participating. The interview data also revealed a combination of internal and external factors that influenced the development of critical thinking during the skills fair intervention including confidence and anxiety levels, attitude, age, experience and practice, faculty involvement, positive learning environment and faculty prompts. These factors should be considered when addressing the promotion and development of critical thinking.

Conclusions, limitations and recommendations

A major concern in the nursing profession is the lack of critical thinking in student nurses and new graduates, which influences the decision-making of novice nurses and directly affects patient care and safety ( Saintsing et al. , 2011 ). Nurse educators must use evidence-based practice to prepare students to critically think with the complicated and constantly evolving environment of health care today ( Goodare, 2015 ; Newton and Moore, 2013 ). Evidence-based practice has been advocated to promote critical thinking ( Profetto-McGrath, 2005 ; Stanley and Dougherty, 2010 ). The skills fair intervention can be one type of evidence-based practice used to promote critical thinking ( McCausland and Meyers, 2013 ; Roberts et al. , 2009 ). The Intervention used in this study incorporated evidence-based practice rationale with critical thinking prompts using Socratic questioning, evidence-based practice videos to the psychomotor skill rubrics, group work, guided discussions, expert demonstration followed by guided practice and blended learning in an attempt to promote and develop critical thinking in nursing students.

The explanatory sequential mixed-methods design was employed to investigate the effects of the innovative skills fair intervention on senior baccalaureate nursing students' achievements and their perceptions of critical thinking skills development. Although the quantitative results showed no significant difference in scores on the KCTIT between students who participated in the skills fair intervention and those who did not, those who attended the interviews perceived their critical thinking was reinforced after the skills fair intervention and believed it was an effective developmental strategy for critical thinking, as it developed alternative thinking and thinking before doing. This information is useful for nurse educators who plan their own teaching practice to promote critical thinking and improve patient outcomes. The findings also provide schools and educators information that helps review their current approach in educating nursing students. As evidenced in the findings, the importance of developing critical thinking skills is crucial for becoming a safe, professional nurse. Internal and external factors impacting the development of critical thinking during the skills fair intervention were identified including confidence and anxiety levels, attitude, age, experience and practice, faculty involvement, positive learning environment and faculty prompts. These factors should be considered when addressing the promotion and development of critical thinking.

There were several limitations to this study. One of the major limitations of the study was the limited exposure of students' time of access to the skills fair intervention, as it was a one-day learning intervention. Another limitation was the sample selection and size. The skills fair intervention was limited to only one baccalaureate nursing program in one southeastern state. As such, the findings of the study cannot be generalized as it may not be representative of baccalaureate nursing programs in general. In addition, this study did not consider students' critical thinking achievements prior to the skills fair intervention. Therefore, no baseline measurement of critical thinking was available for a before and after comparison. Other factors in the nursing program could have affected the students' scores on the KCTIT, such as anxiety or motivation that was not taken into account in this study.

The recommendations for future research are to expand the topic by including other regions, larger samples and other baccalaureate nursing programs. In addition, future research should consider other participant perceptions, such as nurse educators, to better understand the development and growth of critical thinking skills among nursing students. Finally, based on participant perceptions, future research should include a more rigorous skills fair intervention to develop critical thinking and explore the link between confidence and critical thinking in nursing students.

Initial coding results

Factors impacting critical thinking skill development during skills fair intervention

Skills fair intervention as a developmental strategy for critical thinking

American Nephrology Nurses Association (ANNA) ( 2019 ), “ Learning, leading, connecting, and playing at the intersection of nephrology and nursing-2019–2020 strategic plan ”, viewed 3 Aug 2019, available at: https://www.annanurse.org/download/reference/association/strategicPlan.pdf .

Arli , S.D. , Bakan , A.B. , Ozturk , S. , Erisik , E. and Yildirim , Z. ( 2017 ), “ Critical thinking and caring in nursing students ”, International Journal of Caring Sciences , Vol. 10 No. 1 , pp. 471 - 478 .

Benner , P. , Sutphen , M. , Leonard , V. and Day , L. ( 2010 ), Educating Nurses: A Call for Radical Transformation , Jossey-Bass , San Francisco .

Brunt , B. ( 2005 ), “ Critical thinking in nursing: an integrated review ”, The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing , Vol. 36 No. 2 , pp. 60 - 67 .

Chun-Chih , L. , Chin-Yen , H. , I-Ju , P. and Li-Chin , C. ( 2015 ), “ The teaching-learning approach and critical thinking development: a qualitative exploration of Taiwanese nursing students ”, Journal of Professional Nursing , Vol. 31 No. 2 , pp. 149 - 157 , doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2014.07.001 .

Clarke , L.W. and Whitney , E. ( 2009 ), “ Walking in their shoes: using multiple-perspectives texts as a bridge to critical literacy ”, The Reading Teacher , Vol. 62 No. 6 , pp. 530 - 534 , doi: 10.1598/RT.62.6.7 .

Dykstra , D. ( 2008 ), “ Integrating critical thinking and memorandum writing into course curriculum using the internet as a research tool ”, College Student Journal , Vol. 42 No. 3 , pp. 920 - 929 , doi: 10.1007/s10551-010-0477-2 .

Ebright , P. , Urden , L. , Patterson , E. and Chalko , B. ( 2004 ), “ Themes surrounding novice nurse near-miss and adverse-event situations ”, The Journal of Nursing Administration: The Journal of Nursing Administration , Vol. 34 , pp. 531 - 538 , doi: 10.1097/00005110-200411000-00010 .

Ennis , R. ( 2011 ), “ The nature of critical thinking: an outline of critical thinking dispositions and abilities ”, viewed 3 May 2017, available at: https://education.illinois.edu/docs/default-source/faculty-documents/robert-ennis/thenatureofcriticalthinking_51711_000.pdf .

Facione , P.A. ( 1990 ), Critical Thinking: A Statement of Expert Consensus for Purposes of Educational Assessment and Instruction , The California Academic Press , Millbrae .

Facione , N.C. and Facione , P.A. ( 2013 ), The Health Sciences Reasoning Test: Test Manual , The California Academic Press , Millbrae .

Fero , L.J. , Witsberger , C.M. , Wesmiller , S.W. , Zullo , T.G. and Hoffman , L.A. ( 2009 ), “ Critical thinking ability of new graduate and experienced nurses ”, Journal of Advanced Nursing , Vol. 65 No. 1 , pp. 139 - 148 , doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04834.x .

Garvey , P.K. and CNE series ( 2015 ), “ Failure to rescue: the nurse's impact ”, Medsurg Nursing , Vol. 24 No. 3 , pp. 145 - 149 .

Goodare , P. ( 2015 ), “ Literature review: ‘are you ok there?’ The socialization of student and graduate nurses: do we have it right? ”, Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing , Vol. 33 No. 1 , pp. 38 - 43 .

Graneheim , U.H. and Lundman , B. ( 2014 ), “ Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures, and measures to achieve trustworthiness ”, Nurse Education Today , Vol. 24 No. 2 , pp. 105 - 12 , doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001 .

Hsu , L. and Hsieh , S. ( 2013 ), “ Factors affecting metacognition of undergraduate nursing students in a blended learning environment ”, International Journal of Nursing Practice , Vol. 20 No. 3 , pp. 233 - 241 , doi: 10.1111/ijn.12131 .

Ignatavicius , D. ( 2001 ), “ Six critical thinking skills for at-the-bedside success ”, Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing , Vol. 20 No. 2 , pp. 30 - 33 .

Institute of Medicine ( 2001 ), Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century , National Academy Press , Washington .

James , J. ( 2013 ), “ A new, evidence-based estimate of patient harms associated with hospital care ”, Journal of Patient Safety , Vol. 9 No. 3 , pp. 122 - 128 , doi: 10.1097/PTS.0b013e3182948a69 .

Jones , J.H. ( 2010 ), “ Developing critical thinking in the perioperative environment ”, AORN Journal , Vol. 91 No. 2 , pp. 248 - 256 , doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2009.09.025 .

Kaplan Nursing ( 2012 ), Kaplan Nursing Integrated Testing Program Faculty Manual , Kaplan Nursing , New York, NY .

Kim , J.S. , Gu , M.O. and Chang , H.K. ( 2019 ), “ Effects of an evidence-based practice education program using multifaceted interventions: a quasi-experimental study with undergraduate nursing students ”, BMC Medical Education , Vol. 19 , doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1501-6 .

Longton , S. ( 2014 ), “ Utilizing evidence-based practice for patient safety ”, Nephrology Nursing Journal , Vol. 41 No. 4 , pp. 343 - 344 .

McCausland , L.L. and Meyers , C.C. ( 2013 ), “ An interactive skills fair to prepare undergraduate nursing students for clinical experience ”, Nursing Education Perspectives , Vol. 34 No. 6 , pp. 419 - 420 , doi: 10.5480/1536-5026-34.6.419 .

McMullen , M.A. and McMullen , W.F. ( 2009 ), “ Examining patterns of change in the critical thinking skills of graduate nursing students ”, Journal of Nursing Education , Vol. 48 No. 6 , pp. 310 - 318 , doi: 10.3928/01484834-20090515-03 .

Moore , Z.E. ( 2007 ), “ Critical thinking and the evidence-based practice of sport psychology ”, Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology , Vol. 1 , pp. 9 - 22 , doi: 10.1123/jcsp.1.1.9 .

Nadelson , S. and Nadelson , L.S. ( 2014 ), “ Evidence-based practice article reviews using CASP tools: a method for teaching EBP ”, Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing , Vol. 11 No. 5 , pp. 344 - 346 , doi: 10.1111/wvn.12059 .

Newton , S.E. and Moore , G. ( 2013 ), “ Critical thinking skills of basic baccalaureate and accelerated second-degree nursing students ”, Nursing Education Perspectives , Vol. 34 No. 3 , pp. 154 - 158 , doi: 10.5480/1536-5026-34.3.154 .

Nibert , A. ( 2011 ), “ Nursing education and practice: bridging the gap ”, Advance Healthcare Network , viewed 3 May 2017, available at: https://www.elitecme.com/resource-center/nursing/nursing-education-practice-bridging-the-gap/ .

Oermann , M.H. , Kardong-Edgren , S. , Odom-Maryon , T. , Hallmark , B.F. , Hurd , D. , Rogers , N. and Smart , D.A. ( 2011 ), “ Deliberate practice of motor skills in nursing education: CPR as exemplar ”, Nursing Education Perspectives , Vol. 32 No. 5 , pp. 311 - 315 , doi: 10.5480/1536-5026-32.5.311 .

Papathanasiou , I.V. , Kleisiaris , C.F. , Fradelos , E.C. , Kakou , K. and Kourkouta , L. ( 2014 ), “ Critical thinking: the development of an essential skill for nursing students ”, Acta Informatica Medica , Vol. 22 No. 4 , pp. 283 - 286 , doi: 10.5455/aim.2014.22.283-286 .

Park , M.Y. , Conway , J. and McMillan , M. ( 2016 ), “ Enhancing critical thinking through simulation ”, Journal of Problem-Based Learning , Vol. 3 No. 1 , pp. 31 - 40 , doi: 10.24313/jpbl.2016.3.1.31 .

Paul , R. ( 1993 ), Critical Thinking: How to Prepare Students for a Rapidly Changing World , The Foundation for Critical Thinking , Santa Rosa .

Paul , R. and Elder , L. ( 2008 ), “ Critical thinking: the art of socratic questioning, part III ”, Journal of Developmental Education , Vol. 31 No. 3 , pp. 34 - 35 .

Paul , R. and Elder , L. ( 2012 ), Critical Thinking: Tools for Taking Charge of Your Learning and Your Life , 3rd ed. , Pearson/Prentice Hall , Boston .

Profetto-McGrath , J. ( 2005 ), “ Critical thinking and evidence-based practice ”, Journal of Professional Nursing , Vol. 21 No. 6 , pp. 364 - 371 , doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2005.10.002 .

Rahman , A. and Applebaum , R. ( 2011 ), “ What's all this about evidence-based practice? The roots, the controversies, and why it matters ”, American Society on Aging , viewed 3 May 2017, available at: https://www.asaging.org/blog/whats-all-about-evidence-based-practice-roots-controversies-and-why-it-matters .

Rieger , K. , Chernomas , W. , McMillan , D. , Morin , F. and Demczuk , L. ( 2015 ), “ The effectiveness and experience of arts‐based pedagogy among undergraduate nursing students: a comprehensive systematic review protocol ”, JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports , Vol. 13 No. 2 , pp. 101 - 124 , doi: 10.11124/jbisrir-2015-1891 .

Robert , R.R. and Petersen , S. ( 2013 ), “ Critical thinking at the bedside: providing safe passage to patients ”, Medsurg Nursing , Vol. 22 No. 2 , pp. 85 - 118 .

Roberts , S.T. , Vignato , J.A. , Moore , J.L. and Madden , C.A. ( 2009 ), “ Promoting skill building and confidence in freshman nursing students with a skills-a-thon ”, Educational Innovations , Vol. 48 No. 8 , pp. 460 - 464 , doi: 10.3928/01484834-20090518-05 .

Romeo , E. ( 2010 ), “ Quantitative research on critical thinking and predicting nursing students' NCLEX-RN performance ”, Journal of Nursing Education , Vol. 49 No. 7 , pp. 378 - 386 , doi: 10.3928/01484834-20100331-05 .

Sackett , D. , Rosenberg , W. , Gray , J. , Haynes , R. and Richardson , W. ( 1996 ), “ Evidence-based medicine: what it is and what it isn't ”, British Medical Journal , Vol. 312 No. 7023 , pp. 71 - 72 , doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71 .

Saintsing , D. , Gibson , L.M. and Pennington , A.W. ( 2011 ), “ The novice nurse and clinical decision-making: how to avoid errors ”, Journal of Nursing Management , Vol. 19 No. 3 , pp. 354 - 359 .

Saldana , J. ( 2009 ), The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers , Sage , Los Angeles .

Scheffer , B. and Rubenfeld , M. ( 2000 ), “ A consensus statement on critical thinking in nursing ”, Journal of Nursing Education , Vol. 39 No. 8 , pp. 352 - 359 .

Stanley , M.C. and Dougherty , J.P. ( 2010 ), “ Nursing education model. A paradigm shift in nursing education: a new model ”, Nursing Education Perspectives , Vol. 31 No. 6 , pp. 378 - 380 , doi: 10.1043/1536-5026-31.6.378 .

Swing , V.K. ( 2014 ), “ Early identification of transformation in the proficiency level of critical thinking skills (CTS) for the first-semester associate degree nursing (ADN) student ”, doctoral thesis , Capella University , Minneapolis , viewed 3 May 2017, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses database .

Turner , P. ( 2005 ), “ Critical thinking in nursing education and practice as defined in the literature ”, Nursing Education Perspectives , Vol. 26 No. 5 , pp. 272 - 277 .

Twibell , R. , St Pierre , J. , Johnson , D. , Barton , D. , Davis , C. and Kidd , M. ( 2012 ), “ Tripping over the welcome mat: why new nurses don't stay and what the evidence says we can do about it ”, American Nurse Today , Vol. 7 No. 6 , pp. 1 - 10 .

Watson , G. and Glaser , E.M. ( 1980 ), Watson Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal , Psychological Corporation , San Antonio .

Wittmann-Price , R.A. ( 2013 ), “ Facilitating learning in the classroom setting ”, in Wittmann-Price , R.A. , Godshall , M. and Wilson , L. (Eds), Certified Nurse Educator (CNE) Review Manual , Springer Publishing , New York, NY , pp. 19 - 70 .

Corresponding author

Related articles, we’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

What is Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing? (With Examples, Benefits, & Challenges)

Are you a nurse looking for ways to increase patient satisfaction, improve patient outcomes, and impact the profession? Have you found yourself caught between traditional nursing approaches and new patient care practices? Although evidence-based practices have been used for years, this concept is the focus of patient care today more than ever. Perhaps you are wondering, “What is evidence-based practice in nursing?” In this article, I will share information to help you begin understanding evidence-based practice in nursing + 10 examples about how to implement EBP.

What Is Evidence-Based Practice In Nursing?

When was evidence-based practice first introduced in nursing, who introduced evidence-based practice in nursing, what is the difference between evidence-based practice in nursing and research in nursing, what are the benefits of evidence-based practice in nursing, top 5 benefits to the patient, top 5 benefits to the nurse, top 5 benefits to the healthcare organization, 10 strategies nursing schools employ to teach evidence-based practices, 1. assigning case studies:, 2. journal clubs:, 3. clinical presentations:, 4. quizzes:, 5. on-campus laboratory intensives:, 6. creating small work groups:, 7. interactive lectures:, 8. teaching research methods:, 9. requiring collaboration with a clinical preceptor:, 10. research papers:, what are the 5 main skills required for evidence-based practice in nursing, 1. critical thinking:, 2. scientific mindset:, 3. effective written and verbal communication:, 4. ability to identify knowledge gaps:, 5. ability to integrate findings into practice relevant to the patient’s problem:, what are 5 main components of evidence-based practice in nursing, 1. clinical expertise:, 2. management of patient values, circumstances, and wants when deciding to utilize evidence for patient care:, 3. practice management:, 4. decision-making:, 5. integration of best available evidence:, what are some examples of evidence-based practice in nursing, 1. elevating the head of a patient’s bed between 30 and 45 degrees, 2. implementing measures to reduce impaired skin integrity, 3. implementing techniques to improve infection control practices, 4. administering oxygen to a client with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (copd), 5. avoiding frequently scheduled ventilator circuit changes, 6. updating methods for bathing inpatient bedbound clients, 7. performing appropriate patient assessments before and after administering medication, 8. restricting the use of urinary catheterizations, when possible, 9. encouraging well-balanced diets as soon as possible for children with gastrointestinal symptoms, 10. implementing and educating patients about safety measures at home and in healthcare facilities, how to use evidence-based knowledge in nursing practice, step #1: assessing the patient and developing clinical questions:, step #2: finding relevant evidence to answer the clinical question:, step #3: acquire evidence and validate its relevance to the patient’s specific situation:, step #4: appraise the quality of evidence and decide whether to apply the evidence:, step #5: apply the evidence to patient care:, step #6: evaluating effectiveness of the plan:, 10 major challenges nurses face in the implementation of evidence-based practice, 1. not understanding the importance of the impact of evidence-based practice in nursing:, 2. fear of not being accepted:, 3. negative attitudes about research and evidence-based practice in nursing and its impact on patient outcomes:, 4. lack of knowledge on how to carry out research:, 5. resource constraints within a healthcare organization:, 6. work overload:, 7. inaccurate or incomplete research findings:, 8. patient demands do not align with evidence-based practices in nursing:, 9. lack of internet access while in the clinical setting:, 10. some nursing supervisors/managers may not support the concept of evidence-based nursing practices:, 12 ways nurse leaders can promote evidence-based practice in nursing, 1. be open-minded when nurses on your teams make suggestions., 2. mentor other nurses., 3. support and promote opportunities for educational growth., 4. ask for increased resources., 5. be research-oriented., 6. think of ways to make your work environment research-friendly., 7. promote ebp competency by offering strategy sessions with staff., 8. stay up-to-date about healthcare issues and research., 9. actively use information to demonstrate ebp within your team., 10. create opportunities to reinforce skills., 11. develop templates or other written tools that support evidence-based decision-making., 12. review evidence for its relevance to your organization., bonus 8 top suggestions from a nurse to improve your evidence-based practices in nursing, 1. subscribe to nursing journals., 2. offer to be involved with research studies., 3. be intentional about learning., 4. find a mentor., 5. ask questions, 6. attend nursing workshops and conferences., 7. join professional nursing organizations., 8. be honest with yourself about your ability to independently implement evidence-based practice in nursing., useful resources to stay up to date with evidence-based practices in nursing, professional organizations & associations, blogs/websites, youtube videos, my final thoughts, frequently asked questions answered by our expert, 1. what did nurses do before evidence-based practice, 2. how did florence nightingale use evidence-based practice, 3. what is the main limitation of evidence-based practice in nursing, 4. what are the common misconceptions about evidence-based practice in nursing, 5. are all types of nurses required to use evidence-based knowledge in their nursing practice, 6. will lack of evidence-based knowledge impact my nursing career, 7. i do not have access to research databases, how do i improve my evidence-based practice in nursing, 7. are there different levels of evidence-based practices in nursing.

• Level One: Meta-analysis of random clinical trials and experimental studies • Level Two: Quasi-experimental studies- These are focused studies used to evaluate interventions. • Level Three: Non-experimental or qualitative studies. • Level Four: Opinions of nationally recognized experts based on research. • Level Five: Opinions of individual experts based on non-research evidence such as literature reviews, case studies, organizational experiences, and personal experiences.

8. How Can I Assess My Evidence-Based Knowledge In Nursing Practice?

This website is intended for healthcare professionals

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

Brechin A. Introducing critical practice. In: Brechin A, Brown H, Eby MA (eds). London: Sage/Open University; 2000

Introduction to evidence informed decision making. 2012. https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/45245.html (accessed 8 March 2022)

Cullen L, Adams SL. Planning for implementation of evidence-based practice. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2012; 42:(4)222-230 https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0b013e31824ccd0a

DiCenso A, Guyatt G, Ciliska D. Evidence-based nursing. A guide to clinical practice.St. Louis (MO): Mosby; 2005

Implementing evidence-informed practice: International perspectives. In: Dill K, Shera W (eds). Toronto, Canada: Canadian Scholars Press; 2012

Dufault M. Testing a collaborative research utilization model to translate best practices in pain management. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2004; 1:S26-S32 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04049.x

Epstein I. Promoting harmony where there is commonly conflict: evidence-informed practice as an integrative strategy. Soc Work Health Care. 2009; 48:(3)216-231 https://doi.org/10.1080/00981380802589845

Epstein I. Reconciling evidence-based practice, evidence-informed practice, and practice-based research: the role of clinical data-mining. Social Work. 2011; 56:(3)284-288 https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/56.3.284

Implementation research: a synthesis of the literature. 2005. https://tinyurl.com/mwpf4be4 (accessed 6 March 2022)

Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map?. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006; 26:(1)13-24 https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.47

Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Bate P, MacFarlane F, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in health service organisations. A systematic literature review.Malden (MA): Blackwell; 2005

Greenhalgh T, Howick J, Maskrey N. Evidence based medicine: a movement in crisis?. BMJ. 2014; 348 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g3725

Haynes RB, Devereaux PJ, Guyatt GH. Clinical expertise in the era of evidence-based medicine and patient choice. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine. 2002; 7:36-38 https://doi.org/10.1136/ebm.7.2.36

Hitch D, Nicola-Richmond K. Instructional practices for evidence-based practice with pre-registration allied health students: a review of recent research and developments. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2017; 22:(4)1031-1045 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-016-9702-9

Jerkert J. Negative mechanistic reasoning in medical intervention assessment. Theor Med Bioeth. 2015; 36:(6)425-437 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11017-015-9348-2

McSherry R, Artley A, Holloran J. Research awareness: an important factor for evidence-based practice?. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2006; 3:(3)103-115 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6787.2006.00059.x

McSherry R, Simmons M, Pearce P. An introduction to evidence-informed nursing. In: McSherry R, Simmons M, Abbott P London: Routledge; 2002

Implementing excellence in your health care organization: managing, leading and collaborating. In: McSherry R, Warr J (eds). Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2010

Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E, Stillwell SB, Williamson KM. Evidence-based practice: step by step: the seven steps of evidence-based practice. AJN, American Journal of Nursing. 2010; 110:(1)51-53 https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000366056.06605.d2

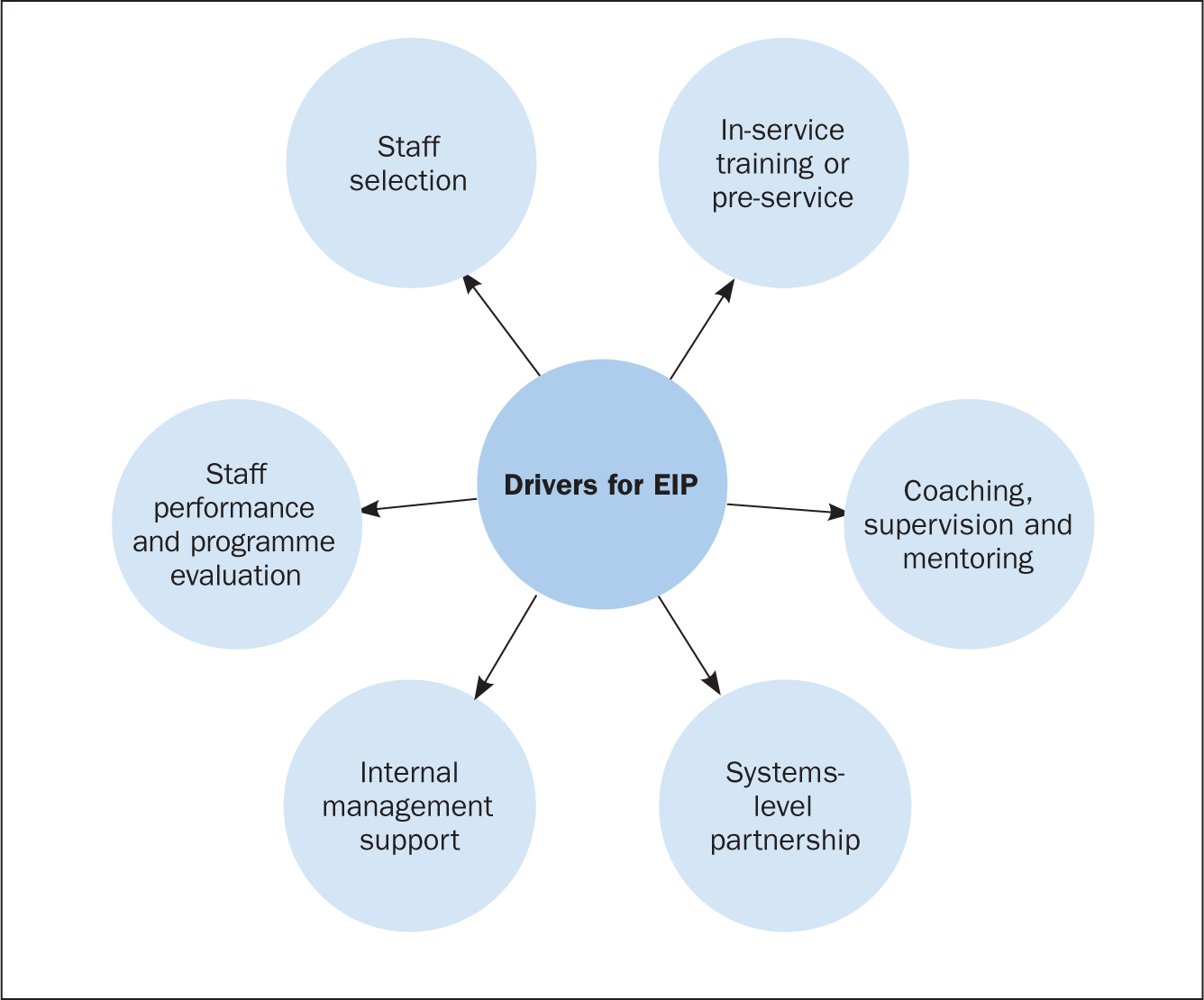

Implementing evidence-based practices: six ‘drivers’ of success. Part 3 in a Series on Fostering the Adoption of Evidence-Based Practices in Out-Of-School Time Programs. 2007. https://tinyurl.com/mu2y6ahk (accessed 8 March 2022)

Muir-Gray JA. Evidence-based healthcare. How to make health policy and management decisions.Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1997

Nevo I, Slonim-Nevo V. The myth of evidence-based practice: towards evidence-informed practice. British Journal of Social Work. 2011; 41:(6)1176-1197 https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcq149

Newhouse RP, Dearholt S, Poe S, Pugh LC, White K. The Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-based Practice Rating Scale.: The Johns Hopkins Hospital: Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing; 2005

Nursing and Midwifery Council. The Code. 2018. https://www.nmc.org.uk/standards/code (accessed 7 March 2022)

Nutley S, Walter I, Davies HTO. Promoting evidence-based practice: models and mechanisms from cross-sector review. Research on Social Work Practice. 2009; 19:(5)552-559 https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731509335496

Reed JE, Howe C, Doyle C, Bell D. Successful Healthcare Improvements From Translating Evidence in complex systems (SHIFT-Evidence): simple rules to guide practice and research. Int J Qual Health Care. 2019; 31:(3)238-244 https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzy160

Rosswurm MA, Larrabee JH. A model for change to evidence-based practice. Image J Nurs Sch. 1999; 31:(4)317-322 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.1999.tb00510.x

Rubin A. Improving the teaching of evidence-based practice: introduction to the special issue. Research on Social Work Practice. 2007; 17:(5)541-547 https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731507300145

Shlonsky A, Mildon R. Methodological pluralism in the age of evidence-informed practice and policy. Scand J Public Health. 2014; 42:18-27 https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494813516716