This site belongs to UNESCO's International Institute for Educational Planning

IIEP Learning Portal

Search form

- issue briefs

- Improve learning

Information and communication technology (ICT) in education

Information and communications technology (ict) can impact student learning when teachers are digitally literate and understand how to integrate it into curriculum..

Schools use a diverse set of ICT tools to communicate, create, disseminate, store, and manage information.(6) In some contexts, ICT has also become integral to the teaching-learning interaction, through such approaches as replacing chalkboards with interactive digital whiteboards, using students’ own smartphones or other devices for learning during class time, and the “flipped classroom” model where students watch lectures at home on the computer and use classroom time for more interactive exercises.

When teachers are digitally literate and trained to use ICT, these approaches can lead to higher order thinking skills, provide creative and individualized options for students to express their understandings, and leave students better prepared to deal with ongoing technological change in society and the workplace.(18)

ICT issues planners must consider include: considering the total cost-benefit equation, supplying and maintaining the requisite infrastructure, and ensuring investments are matched with teacher support and other policies aimed at effective ICT use.(16)

Issues and Discussion

Digital culture and digital literacy: Computer technologies and other aspects of digital culture have changed the ways people live, work, play, and learn, impacting the construction and distribution of knowledge and power around the world.(14) Graduates who are less familiar with digital culture are increasingly at a disadvantage in the national and global economy. Digital literacy—the skills of searching for, discerning, and producing information, as well as the critical use of new media for full participation in society—has thus become an important consideration for curriculum frameworks.(8)

In many countries, digital literacy is being built through the incorporation of information and communication technology (ICT) into schools. Some common educational applications of ICT include:

- One laptop per child: Less expensive laptops have been designed for use in school on a 1:1 basis with features like lower power consumption, a low cost operating system, and special re-programming and mesh network functions.(42) Despite efforts to reduce costs, however, providing one laptop per child may be too costly for some developing countries.(41)

- Tablets: Tablets are small personal computers with a touch screen, allowing input without a keyboard or mouse. Inexpensive learning software (“apps”) can be downloaded onto tablets, making them a versatile tool for learning.(7)(25) The most effective apps develop higher order thinking skills and provide creative and individualized options for students to express their understandings.(18)

- Interactive White Boards or Smart Boards : Interactive white boards allow projected computer images to be displayed, manipulated, dragged, clicked, or copied.(3) Simultaneously, handwritten notes can be taken on the board and saved for later use. Interactive white boards are associated with whole-class instruction rather than student-centred activities.(38) Student engagement is generally higher when ICT is available for student use throughout the classroom.(4)

- E-readers : E-readers are electronic devices that can hold hundreds of books in digital form, and they are increasingly utilized in the delivery of reading material.(19) Students—both skilled readers and reluctant readers—have had positive responses to the use of e-readers for independent reading.(22) Features of e-readers that can contribute to positive use include their portability and long battery life, response to text, and the ability to define unknown words.(22) Additionally, many classic book titles are available for free in e-book form.

- Flipped Classrooms: The flipped classroom model, involving lecture and practice at home via computer-guided instruction and interactive learning activities in class, can allow for an expanded curriculum. There is little investigation on the student learning outcomes of flipped classrooms.(5) Student perceptions about flipped classrooms are mixed, but generally positive, as they prefer the cooperative learning activities in class over lecture.(5)(35)

ICT and Teacher Professional Development: Teachers need specific professional development opportunities in order to increase their ability to use ICT for formative learning assessments, individualized instruction, accessing online resources, and for fostering student interaction and collaboration.(15) Such training in ICT should positively impact teachers’ general attitudes towards ICT in the classroom, but it should also provide specific guidance on ICT teaching and learning within each discipline. Without this support, teachers tend to use ICT for skill-based applications, limiting student academic thinking.(32) To support teachers as they change their teaching, it is also essential for education managers, supervisors, teacher educators, and decision makers to be trained in ICT use.(11)

Ensuring benefits of ICT investments: To ensure the investments made in ICT benefit students, additional conditions must be met. School policies need to provide schools with the minimum acceptable infrastructure for ICT, including stable and affordable internet connectivity and security measures such as filters and site blockers. Teacher policies need to target basic ICT literacy skills, ICT use in pedagogical settings, and discipline-specific uses. (21) Successful implementation of ICT requires integration of ICT in the curriculum. Finally, digital content needs to be developed in local languages and reflect local culture. (40) Ongoing technical, human, and organizational supports on all of these issues are needed to ensure access and effective use of ICT. (21)

Resource Constrained Contexts: The total cost of ICT ownership is considerable: training of teachers and administrators, connectivity, technical support, and software, amongst others. (42) When bringing ICT into classrooms, policies should use an incremental pathway, establishing infrastructure and bringing in sustainable and easily upgradable ICT. (16) Schools in some countries have begun allowing students to bring their own mobile technology (such as laptop, tablet, or smartphone) into class rather than providing such tools to all students—an approach called Bring Your Own Device. (1)(27)(34) However, not all families can afford devices or service plans for their children. (30) Schools must ensure all students have equitable access to ICT devices for learning.

Inclusiveness Considerations

Digital Divide: The digital divide refers to disparities of digital media and internet access both within and across countries, as well as the gap between people with and without the digital literacy and skills to utilize media and internet.(23)(26)(31) The digital divide both creates and reinforces socio-economic inequalities of the world’s poorest people. Policies need to intentionally bridge this divide to bring media, internet, and digital literacy to all students, not just those who are easiest to reach.

Minority language groups: Students whose mother tongue is different from the official language of instruction are less likely to have computers and internet connections at home than students from the majority. There is also less material available to them online in their own language, putting them at a disadvantage in comparison to their majority peers who gather information, prepare talks and papers, and communicate more using ICT. (39) Yet ICT tools can also help improve the skills of minority language students—especially in learning the official language of instruction—through features such as automatic speech recognition, the availability of authentic audio-visual materials, and chat functions. (2)(17)

Students with different styles of learning: ICT can provide diverse options for taking in and processing information, making sense of ideas, and expressing learning. Over 87% of students learn best through visual and tactile modalities, and ICT can help these students ‘experience’ the information instead of just reading and hearing it. (20)(37) Mobile devices can also offer programmes (“apps”) that provide extra support to students with special needs, with features such as simplified screens and instructions, consistent placement of menus and control features, graphics combined with text, audio feedback, ability to set pace and level of difficulty, appropriate and unambiguous feedback, and easy error correction. (24)(29)

Plans and policies

- India [ PDF ]

- Detroit, USA [ PDF ]

- Finland [ PDF ]

- Alberta Education. 2012. Bring your own device: A guide for schools . Retrieved from http://education.alberta.ca/admin/technology/research.aspx

- Alsied, S.M. and Pathan, M.M. 2015. ‘The use of computer technology in EFL classroom: Advantages and implications.’ International Journal of English Language and Translation Studies . 1 (1).

- BBC. N.D. ‘What is an interactive whiteboard?’ Retrieved from http://www.bbcactive.com/BBCActiveIdeasandResources/Whatisaninteractivewhiteboard.aspx

- Beilefeldt, T. 2012. ‘Guidance for technology decisions from classroom observation.’ Journal of Research on Technology in Education . 44 (3).

- Bishop, J.L. and Verleger, M.A. 2013. ‘The flipped classroom: A survey of the research.’ Presented at the 120th ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition. Atlanta, Georgia.

- Blurton, C. 2000. New Directions of ICT-Use in Education . United National Education Science and Culture Organization (UNESCO).

- Bryant, B.R., Ok, M., Kang, E.Y., Kim, M.K., Lang, R., Bryant, D.P. and Pfannestiel, K. 2015. ‘Performance of fourth-grade students with learning disabilities on multiplication facts comparing teacher-mediated and technology-mediated interventions: A preliminary investigation. Journal of Behavioral Education. 24.

- Buckingham, D. 2005. Educación en medios. Alfabetización, aprendizaje y cultura contemporánea, Barcelona, Paidós.

- Buckingham, D., Sefton-Green, J., and Scanlon, M. 2001. 'Selling the Digital Dream: Marketing Education Technologies to Teachers and Parents.' ICT, Pedagogy, and the Curriculum: Subject to Change . London: Routledge.

- "Burk, R. 2001. 'E-book devices and the marketplace: In search of customers.' Library Hi Tech 19 (4)."

- Chapman, D., and Mählck, L. (Eds). 2004. Adapting technology for school improvement: a global perspective. Paris: International Institute for Educational Planning.

- Cheung, A.C.K and Slavin, R.E. 2012. ‘How features of educational technology applications affect student reading outcomes: A meta-analysis.’ Educational Research Review . 7.

- Cheung, A.C.K and Slavin, R.E. 2013. ‘The effectiveness of educational technology applications for enhancing mathematics achievement in K-12 classrooms: A meta-analysis.’ Educational Research Review . 9.

- Deuze, M. 2006. 'Participation Remediation Bricolage - Considering Principal Components of a Digital Culture.' The Information Society . 22 .

- Dunleavy, M., Dextert, S. and Heinecke, W.F. 2007. ‘What added value does a 1:1 student to laptop ratio bring to technology-supported teaching and learning?’ Journal of Computer Assisted Learning . 23.

- Enyedy, N. 2014. Personalized Instruction: New Interest, Old Rhetoric, Limited Results, and the Need for a New Direction for Computer-Mediated Learning . Boulder, CO: National Education Policy Center.

- Golonka, E.M., Bowles, A.R., Frank, V.M., Richardson, D.L. and Freynik, S. 2014. ‘Technologies for foreign language learning: A review of technology types and their effectiveness.’ Computer Assisted Language Learning . 27 (1).

- Goodwin, K. 2012. Use of Tablet Technology in the Classroom . Strathfield, New South Wales: NSW Curriculum and Learning Innovation Centre.

- Jung, J., Chan-Olmsted, S., Park, B., and Kim, Y. 2011. 'Factors affecting e-book reader awareness, interest, and intention to use.' New Media & Society . 14 (2)

- Kenney, L. 2011. ‘Elementary education, there’s an app for that. Communication technology in the elementary school classroom.’ The Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications . 2 (1).

- Kopcha, T.J. 2012. ‘Teachers’ perceptions of the barriers to technology integration and practices with technology under situated professional development.’ Computers and Education . 59.

- Miranda, T., Williams-Rossi, D., Johnson, K., and McKenzie, N. 2011. "Reluctant readers in middle school: Successful engagement with text using the e-reader.' International journal of applied science and technology . 1 (6).

- Moyo, L. 2009. 'The digital divide: scarcity, inequality and conflict.' Digital Cultures . New York: Open University Press.

- Newton, D.A. and Dell, A.G. 2011. ‘Mobile devices and students with disabilities: What do best practices tell us?’ Journal of Special Education Technology . 26 (3).

- Nirvi, S. (2011). ‘Special education pupils find learning tool in iPad applications.’ Education Week . 30 .

- Norris, P. 2001. Digital Divide: Civic Engagement, Information Poverty, and the Internet Worldwide . Cambridge, USA: Cambridge University Press.

- Project Tomorrow. 2012. Learning in the 21st century: Mobile devices + social media = personalized learning . Washington, D.C.: Blackboard K-12.

- Riasati, M.J., Allahyar, N. and Tan, K.E. 2012. ‘Technology in language education: Benefits and barriers.’ Journal of Education and Practice . 3 (5).

- Rodriquez, C.D., Strnadova, I. and Cumming, T. 2013. ‘Using iPads with students with disabilities: Lessons learned from students, teachers, and parents.’ Intervention in School and Clinic . 49 (4).

- Sangani, K. 2013. 'BYOD to the classroom.' Engineering & Technology . 3 (8).

- Servon, L. 2002. Redefining the Digital Divide: Technology, Community and Public Policy . Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers.

- Smeets, E. 2005. ‘Does ICT contribute to powerful learning environments in primary education?’ Computers and Education. 44 .

- Smith, G.E. and Thorne, S. 2007. Differentiating Instruction with Technology in K-5 Classrooms . Eugene, OR: International Society for Technology in Education.

- Song, Y. 2014. '"Bring your own device (BYOD)" for seamless science inquiry in a primary school.' Computers & Education. 74 .

- Strayer, J.F. 2012. ‘How learning in an inverted classroom influences cooperation, innovation and task orientation.’ Learning Environment Research. 15.

- Tamim, R.M., Bernard, R.M., Borokhovski, E., Abrami, P.C. and Schmid, R.F. 2011. ‘What forty years of research says about the impact of technology on learning: A second-order meta-analysis and validation study. Review of Educational Research. 81 (1).

- Tileston, D.W. 2003. What Every Teacher Should Know about Media and Technology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

- Turel, Y.K. and Johnson, T.E. 2012. ‘Teachers’ belief and use of interactive whiteboards for teaching and learning.’ Educational Technology and Society . 15(1).

- Volman, M., van Eck, E., Heemskerk, I. and Kuiper, E. 2005. ‘New technologies, new differences. Gender and ethnic differences in pupils’ use of ICT in primary and secondary education.’ Computers and Education. 45 .

- Voogt, J., Knezek, G., Cox, M., Knezek, D. and ten Brummelhuis, A. 2013. ‘Under which conditions does ICT have a positive effect on teaching and learning? A call to action.’ Journal of Computer Assisted Learning. 29 (1).

- Warschauer, M. and Ames, M. 2010. ‘Can one laptop per child save the world’s poor?’ Journal of International Affairs. 64 (1).

- Zuker, A.A. and Light, D. 2009. ‘Laptop programs for students.’ Science. 323 (5910).

Related information

- Information and communication technologies (ICT)

New global data reveal education technology’s impact on learning

The promise of technology in the classroom is great: enabling personalized, mastery-based learning; saving teacher time; and equipping students with the digital skills they will need for 21st-century careers. Indeed, controlled pilot studies have shown meaningful improvements in student outcomes through personalized blended learning. 1 John F. Pane et al., “How does personalized learning affect student achievement?,” RAND Corporation, 2017, rand.org. During this time of school shutdowns and remote learning , education technology has become a lifeline for the continuation of learning.

As school systems begin to prepare for a return to the classroom , many are asking whether education technology should play a greater role in student learning beyond the immediate crisis and what that might look like. To help inform the answer to that question, this article analyzes one important data set: the 2018 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), published in December 2019 by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Every three years, the OECD uses PISA to test 15-year-olds around the world on math, reading, and science. What makes these tests so powerful is that they go beyond the numbers, asking students, principals, teachers, and parents a series of questions about their attitudes, behaviors, and resources. An optional student survey on information and communications technology (ICT) asks specifically about technology use—in the classroom, for homework, and more broadly.

In 2018, more than 340,000 students in 51 countries took the ICT survey, providing a rich data set for analyzing key questions about technology use in schools. How much is technology being used in schools? Which technologies are having a positive impact on student outcomes? What is the optimal amount of time to spend using devices in the classroom and for homework? How does this vary across different countries and regions?

From other studies we know that how education technology is used, and how it is embedded in the learning experience, is critical to its effectiveness. This data is focused on extent and intensity of use, not the pedagogical context of each classroom. It cannot therefore answer questions on the eventual potential of education technology—but it can powerfully tell us the extent to which that potential is being realized today in classrooms around the world.

Five key findings from the latest results help answer these questions and suggest potential links between technology and student outcomes:

- The type of device matters—some are associated with worse student outcomes.

- Geography matters—technology is associated with higher student outcomes in the United States than in other regions.

- Who is using the technology matters—technology in the hands of teachers is associated with higher scores than technology in the hands of students.

- Intensity matters—students who use technology intensely or not at all perform better than those with moderate use.

- A school system’s current performance level matters—in lower-performing school systems, technology is associated with worse results.

This analysis covers only one source of data, and it should be interpreted with care alongside other relevant studies. Nonetheless, the 2018 PISA results suggest that systems aiming to improve student outcomes should take a more nuanced and cautious approach to deploying technology once students return to the classroom. It is not enough add devices to the classroom, check the box, and hope for the best.

What can we learn from the latest PISA results?

How will the use, and effectiveness, of technology change post-covid-19.

The PISA assessment was carried out in 2018 and published in December 2019. Since its publication, schools and students globally have been quite suddenly thrust into far greater reliance on technology. Use of online-learning websites and adaptive software has expanded dramatically. Khan Academy has experienced a 250 percent surge in traffic; smaller sites have seen traffic grow fivefold or more. Hundreds of thousands of teachers have been thrown into the deep end, learning to use new platforms, software, and systems. No one is arguing that the rapid cobbling together of remote learning under extreme time pressure represents best-practice use of education technology. Nonetheless, a vast experiment is underway, and innovations often emerge in times of crisis. At this point, it is unclear whether this represents the beginning of a new wave of more widespread and more effective technology use in the classroom or a temporary blip that will fade once students and teachers return to in-person instruction. It is possible that a combination of software improvements, teacher capability building, and student familiarity will fundamentally change the effectiveness of education technology in improving student outcomes. It is also possible that our findings will continue to hold true and technology in the classroom will continue to be a mixed blessing. It is therefore critical that ongoing research efforts track what is working and for whom and, just as important, what is not. These answers will inform the project of reimagining a better education for all students in the aftermath of COVID-19.

PISA data have their limitations. First, these data relate to high-school students, and findings may not be applicable in elementary schools or postsecondary institutions. Second, these are single-point observational data, not longitudinal experimental data, which means that any links between technology and results should be interpreted as correlation rather than causation. Third, the outcomes measured are math, science, and reading test results, so our analysis cannot assess important soft skills and nonacademic outcomes.

It is also worth noting that technology for learning has implications beyond direct student outcomes, both positive and negative. PISA cannot address these broader issues, and neither does this paper.

But PISA results, which we’ve broken down into five key findings, can still provide powerful insights. The assessment strives to measure the understanding and application of ideas, rather than the retention of facts derived from rote memorization, and the broad geographic coverage and sample size help elucidate the reality of what is happening on the ground.

Finding 1: The type of device matters

The evidence suggests that some devices have more impact than others on outcomes (Exhibit 1). Controlling for student socioeconomic status, school type, and location, 2 Specifically, we control for a composite indicator for economic, social, and cultural status (ESCS) derived from questions about general wealth, home possessions, parental education, and parental occupation; for school type “Is your school a public or a private school” (SC013); and for school location (SC001) where the options are a village, hamlet or rural area (fewer than 3,000 people), a small town (3,000 to about 15,000 people), a town (15,000 to about 100,000 people), a city (100,000 to about 1,000,000 people), and a large city (with more than 1,000,000 people). the use of data projectors 3 A projector is any device that projects computer output, slides, or other information onto a screen in the classroom. and internet-connected computers in the classroom is correlated with nearly a grade-level-better performance on the PISA assessment (assuming approximately 40 PISA points to every grade level). 4 Students were specifically asked (IC009), “Are any of these devices available for you to use at school?,” with the choices being “Yes, and I use it,” “Yes, but I don’t use it,” and “No.” We compared the results for students who have access to and use each device with those who do not have access. The full text for each device in our chart was as follows: Data projector, eg, for slide presentations; Internet-connected school computers; Desktop computer; Interactive whiteboard, eg, SmartBoard; Portable laptop or notebook; and Tablet computer, eg, iPad, BlackBerry PlayBook.

On the other hand, students who use laptops and tablets in the classroom have worse results than those who do not. For laptops, the impact of technology varies by subject; students who use laptops score five points lower on the PISA math assessment, but the impact on science and reading scores is not statistically significant. For tablets, the picture is clearer—in every subject, students who use tablets in the classroom perform a half-grade level worse than those who do not.

Some technologies are more neutral. At the global level, there is no statistically significant difference between students who use desktop computers and interactive whiteboards in the classroom and those who do not.

Finding 2: Geography matters

Looking more closely at the reading results, which were the focus of the 2018 assessment, 5 PISA rotates between focusing on reading, science, and math. The 2018 assessment focused on reading. This means that the total testing time was two hours for each student, of which one hour was reading focused. we can see that the relationship between technology and outcomes varies widely by country and region (Exhibit 2). For example, in all regions except the United States (representing North America), 6 The United States is the only country that took the ICT Familiarity Questionnaire survey in North America; thus, we are comparing it as a country with the other regions. students who use laptops in the classroom score between five and 12 PISA points lower than students who do not use laptops. In the United States, students who use laptops score 17 PISA points higher than those who do not. It seems that US students and teachers are doing something different with their laptops than those in other regions. Perhaps this difference is related to learning curves that develop as teachers and students learn how to get the most out of devices. A proxy to assess this learning curve could be penetration—71 percent of US students claim to be using laptops in the classroom, compared with an average of 37 percent globally. 7 The rate of use excludes nulls. The United States measures higher than any other region in laptop use by students in the classroom. US = 71 percent, Asia = 40 percent, EU = 35 percent, Latin America = 31 percent, MENA = 21 percent, Non-EU Europe = 41 percent. We observe a similar pattern with interactive whiteboards in non-EU Europe. In every other region, interactive whiteboards seem to be hurting results, but in non-EU Europe they are associated with a lift of 21 PISA points, a total that represents a half-year of learning. In this case, however, penetration is not significantly higher than in other developed regions.

Finding 3: It matters whether technology is in the hands of teachers or students

The survey asks students whether the teacher, student, or both were using technology. Globally, the best results in reading occur when only the teacher is using the device, with some benefit in science when both teacher and students use digital devices (Exhibit 3). Exclusive use of the device by students is associated with significantly lower outcomes everywhere. The pattern is similar for science and math.

Again, the regional differences are instructive. Looking again at reading, we note that US students are getting significant lift (three-quarters of a year of learning) from either just teachers or teachers and students using devices, while students alone using a device score significantly lower (half a year of learning) than students who do not use devices at all. Exclusive use of devices by the teacher is associated with better outcomes in Europe too, though the size of the effect is smaller.

Finding 4: Intensity of use matters

PISA also asked students about intensity of use—how much time they spend on devices, 8 PISA rotates between focusing on reading, science, and math. The 2018 assessment focused on reading. This means that the total testing time was two hours for each student, of which one hour was reading focused. both in the classroom and for homework. The results are stark: students who either shun technology altogether or use it intensely are doing better, with those in the middle flailing (Exhibit 4).

The regional data show a dramatic picture. In the classroom, the optimal amount of time to spend on devices is either “none at all” or “greater than 60 minutes” per subject per week in every region and every subject (this is the amount of time associated with the highest student outcomes, controlling for student socioeconomic status, school type, and location). In no region is a moderate amount of time (1–30 minutes or 31–60 minutes) associated with higher student outcomes. There are important differences across subjects and regions. In math, the optimal amount of time is “none at all” in every region. 9 The United States is the only country that took the ICT Familiarity Questionnaire survey in North America; thus, we are comparing it as a country with the other regions. In reading and science, however, the optimal amount of time is greater than 60 minutes for some regions: Asia and the United States for reading, and the United States and non-EU Europe for science.

The pattern for using devices for homework is slightly less clear cut. Students in Asia, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), and non-EU Europe score highest when they spend “no time at all” on devices for their homework, while students spending a moderate amount of time (1–60 minutes) score best in Latin America and the European Union. Finally, students in the United States who spend greater than 60 minutes are getting the best outcomes.

One interpretation of these data is that students need to get a certain familiarity with technology before they can really start using it to learn. Think of typing an essay, for example. When students who mostly write by hand set out to type an essay, their attention will be focused on the typing rather than the essay content. A competent touch typist, however, will get significant productivity gains by typing rather than handwriting.

Would you like to learn more about our Social Sector Practice ?

Finding 5: the school systems’ overall performance level matters.

Diving deeper into the reading outcomes, which were the focus of the 2018 assessment, we can see the magnitude of the impact of device use in the classroom. In Asia, Latin America, and Europe, students who spend any time on devices in their literacy and language arts classrooms perform about a half-grade level below those who spend none at all. In MENA, they perform more than a full grade level lower. In the United States, by contrast, more than an hour of device use in the classroom is associated with a lift of 17 PISA points, almost a half-year of learning improvement (Exhibit 5).

At the country level, we see that those who are on what we would call the “poor-to-fair” stage of the school-system journey 10 Michael Barber, Chinezi Chijoke, and Mona Mourshed, “ How the world’s most improved school systems keep getting better ,” November 2010. have the worst relationships between technology use and outcomes. For every poor-to-fair system taking the survey, the amount of time on devices in the classroom associated with the highest student scores is zero minutes. Good and great systems are much more mixed. Students in some very highly performing systems (for example, Estonia and Chinese Taipei) perform highest with no device use, but students in other systems (for example, Japan, the United States, and Australia) are getting the best scores with over an hour of use per week in their literacy and language arts classrooms (Exhibit 6). These data suggest that multiple approaches are effective for good-to-great systems, but poor-to-fair systems—which are not well equipped to use devices in the classroom—may need to rethink whether technology is the best use of their resources.

What are the implications for students, teachers, and systems?

Looking across all these results, we can say that the relationship between technology and outcomes in classrooms today is mixed, with variation by device, how that device is used, and geography. Our data do not permit us to draw strong causal conclusions, but this section offers a few hypotheses, informed by existing literature and our own work with school systems, that could explain these results.

First, technology must be used correctly to be effective. Our experience in the field has taught us that it is not enough to “add technology” as if it were the missing, magic ingredient. The use of tech must start with learning goals, and software selection must be based on and integrated with the curriculum. Teachers need support to adapt lesson plans to optimize the use of technology, and teachers should be using the technology themselves or in partnership with students, rather than leaving students alone with devices. These lessons hold true regardless of geography. Another ICT survey question asked principals about schools’ capacity using digital devices. Globally, students performed better in schools where there were sufficient numbers of devices connected to fast internet service; where they had adequate software and online support platforms; and where teachers had the skills, professional development, and time to integrate digital devices in instruction. This was true even accounting for student socioeconomic status, school type, and location.

COVID-19 and student learning in the United States: The hurt could last a lifetime

Second, technology must be matched to the instructional environment and context. One of the most striking findings in the latest PISA assessment is the extent to which technology has had a different impact on student outcomes in different geographies. This corroborates the findings of our 2010 report, How the world’s most improved school systems keep getting better . Those findings demonstrated that different sets of interventions were needed at different stages of the school-system reform journey, from poor-to-fair to good-to-great to excellent. In poor-to-fair systems, limited resources and teacher capabilities as well as poor infrastructure and internet bandwidth are likely to limit the benefits of student-based technology. Our previous work suggests that more prescriptive, teacher-based approaches and technologies (notably data projectors) are more likely to be effective in this context. For example, social enterprise Bridge International Academies equips teachers across several African countries with scripted lesson plans using e-readers. In general, these systems would likely be better off investing in teacher coaching than in a laptop per child. For administrators in good-to-great systems, the decision is harder, as technology has quite different impacts across different high-performing systems.

Third, technology involves a learning curve at both the system and student levels. It is no accident that the systems in which the use of education technology is more mature are getting more positive impact from tech in the classroom. The United States stands out as the country with the most mature set of education-technology products, and its scale enables companies to create software that is integrated with curricula. 11 Common Core State Standards sought to establish consistent educational standards across the United States. While these have not been adopted in all states, they cover enough states to provide continuity and consistency for software and curriculum developers. A similar effect also appears to operate at the student level; those who dabble in tech may be spending their time learning the tech rather than using the tech to learn. This learning curve needs to be built into technology-reform programs.

Taken together, these results suggest that systems that take a comprehensive, data-informed approach may achieve learning gains from thoughtful use of technology in the classroom. The best results come when significant effort is put into ensuring that devices and infrastructure are fit for purpose (fast enough internet service, for example), that software is effective and integrated with curricula, that teachers are trained and given time to rethink lesson plans integrating technology, that students have enough interaction with tech to use it effectively, and that technology strategy is cognizant of the system’s position on the school-system reform journey. Online learning and education technology are currently providing an invaluable service by enabling continued learning over the course of the pandemic; this does not mean that they should be accepted uncritically as students return to the classroom.

Jake Bryant is an associate partner in McKinsey’s Washington, DC, office; Felipe Child is a partner in the Bogotá office; Emma Dorn is the global Education Practice manager in the Silicon Valley office; and Stephen Hall is an associate partner in the Dubai office.

The authors wish to thank Fernanda Alcala, Sujatha Duraikkannan, and Samuel Huang for their contributions to this article.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Safely back to school after coronavirus closures

How the world’s most improved school systems keep getting better

ICT in education: Benefits, Challenges and New directions

Ieee account.

- Change Username/Password

- Update Address

Purchase Details

- Payment Options

- Order History

- View Purchased Documents

Profile Information

- Communications Preferences

- Profession and Education

- Technical Interests

- US & Canada: +1 800 678 4333

- Worldwide: +1 732 981 0060

- Contact & Support

- About IEEE Xplore

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Nondiscrimination Policy

- Privacy & Opting Out of Cookies

A not-for-profit organization, IEEE is the world's largest technical professional organization dedicated to advancing technology for the benefit of humanity. © Copyright 2024 IEEE - All rights reserved. Use of this web site signifies your agreement to the terms and conditions.

- News: IITE and partners in action

UNESCO IITE and Moscow City University join efforts to promote digital didactics

On the 5 th of March 2021, the UNESCO IITE delegation visited Moscow City University to sign the Memorandum of Understanding that will support cooperation between two organisations in the field of digital didactics and online technologies in education and human development. The delegation consisted of Mr. Tao Zhan, Director of UNESCO IITE, Ms. Svetlana Knyazeva, Chief of the Unit of Digital Pedagogy and Learning Materials , and Ms. Tatyana Murovana, Programme Specialist of the Institute.

Mr. Igor Remorenko, the Rector of MCU, delivered a welcome speech in which he introduced the MCU’s history and directions of academic and research activities. Mr. Kirill Barannikov, Vice-Rector for Strategy, Ms. Daria Milyaeva, Head of the International Relations Department, and Ms. Svetlana Shilkina, Head of the Innovation Policy Department, also took part in the meeting.

Mr. Tao Zhan expressed his gratitude for the hospitality provided and highlighted the importance of reinforcing the partnership with MCU:

We are glad that there are now more opportunities to cooperate with Moscow City University. Let us join our efforts to research, to organise events and launch projects that promote digital didactics, online technologies, as well as design of electronic courses. Tao Zhan, Director of UNESCO IITE

The Memorandum suggests the exchange of international experience on the issues of digital transformation of general and higher education, implementation of innovative learning and teaching technologies, and networking.

Moscow City University was founded by the resolution of the Moscow Government in 1995. Its mission is to provide a comprehensive educational system that trains students for life and work in a big city, combining educational practices with the objectives of the city development.

Advertisement

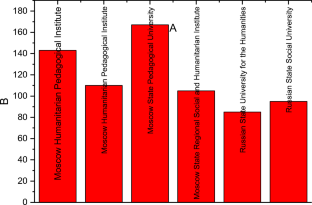

Innovation and communication technologies: Analysis of the effectiveness of their use and implementation in higher education

- Published: 18 May 2019

- Volume 24 , pages 3219–3234, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

- Elena A. Tokareva 1 ,

- Yulia V. Smirnova 1 &

- Larisa G. Orchakova 1

1992 Accesses

22 Citations

Explore all metrics

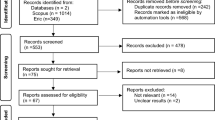

In our research, we have developed and conducted a survey to determine the quality of implementation and organisation of ICT from the point of view of university students. The study was conducted in two groups of students, intramural and extramural, to identify a common problem of domestic education. The survey focuses on various aspects: a student view of education programme innovativeness, teachers’ participation in the ICT introduction, and the technological support in selected universities. These developments can be useful for universities that faced with the problem of introducing innovation and communication technologies. The recommendations described in the research can be used as a solution to the current problems associated with the organisation of ICT. On the way to solving the problem of using and introducing innovative technologies in higher education, it is very important to reorganize all aspects: completeness of education programmes, technological literacy of teachers and technical support provided by universities.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Impacts of digital technologies on education and factors influencing schools' digital capacity and transformation: A literature review

Stella Timotheou, Ourania Miliou, … Andri Ioannou

Adoption of artificial intelligence in higher education: a quantitative analysis using structural equation modelling

Sheshadri Chatterjee & Kalyan Kumar Bhattacharjee

A systematic literature review of ICT integration in secondary education: what works, what does not, and what next?

Mgambi Msambwa Msafiri, Daniel Kangwa & Lianyu Cai

Alemu, B. M. (2015). Integrating ICT into teaching-learning practices: Promise, challenges and future directions of higher educational institutes. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 3 (3), 170–189.

Article Google Scholar

Alfred, M. V. (2003). Sociocultural contexts and learning: Anglophone Caribbean immigrant women in US postsecondary education. Adult Education Quarterly, 53 (4), 242–260.

Amin Khandaghi, M., & Pakmehr, H. (2012). Critical thinking disposition: A neglected loop of humanities curriculum in higher education. Cypriot Journal of Educational Sciences, 7 , 1–13.

Arkorful, V., & Abaidoo, N. (2015). The role of e-learning, advantages and disadvantages of its adoption in higher education. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 12 (1), 29–42.

Google Scholar

Aslan, A., & Zhu, C. (2016). Influencing factors and integration of ICT into teaching practices of pre-service and starting teachers. International Journal of Research in Education and Science, 2 (2), 359–370.

Collis, B. & van der Wende, M. (2002). Models of Technology and Change in Higher Education. An international comparative survey on the current and future use of ICT in higher education. Twente: CHEPS, Centre for Higher Education Policy Studies.

Conley, T., Mehta, N., Stinebrickner, R., & Stinebrickner, T. (2015). Social interactions, mechanisms, and equilibrium: Evidence from a model of study time and academic achievement (no. w21418). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Davis, N. (2003). Technology in teacher education in the USA: What makes for sustainable good practice? Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 12 (1), 59–84.

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Dmitrieva, T., German, E., & Khvatova, T. (2018). Digital technologies and higher education in Russia: New tools of development. SHS Web of Conferences, 44 (29).

Du Plessis, M. (2007). The role of knowledge management in innovation. Journal of Knowledge Management, 11 (4), 20–29.

Dublin, L. (2003). If you only look under the street lamps……Or nine e-Learning Myths. The eLearning developers journal. http://www.eLearningguild.com .

Duţă, N. (2018). The role of education in the development of moral values and principles-empirical study. Euromentor Journal, 9 (4), 44–55.

MathSciNet Google Scholar

Duţă, N., & Martínez-Rivera, O. (2015). Between theory and practice: The importance of ICT in higher education as a tool for collaborative learning. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 180 , 1466–1473.

Eriksen, T. H. (2001). Tyranny of the moment: Fast and slow time in the information age . London: Pluto Press.

Fadel, Ch., Trilling, B., & Bialik, M. (2018). Four-dimensional education: The competencies learners need to succeed (pp. 240). The Center for Curriculum Redesign, Boston, MA.

Green, K.C. (2004). The 2004 National Survey of Information Technology in US Higher Education ( www.campuscomputing.net ).

Hernandez, R. M. (2017). Impact of ICT on education: Challenges and perspectives. Propósitos y Representaciones, 5 (1), 325–347.

Holmes, B., & Gardner, J. (2006). E-Learning: Concepts and practice . London: SAGE Publications.

Honarpour, A., Jusoh, A., & Md Nor, K. (2012). Knowledge management, Total quality management and innovation: A new look. Journal of Technology Management & Innovation, 7 (3), 22–31.

Joiner, L. L. (2002). A virtual tour of virtual schools. American School Board Journal, 189 (9), 50-52.

Kataoka, H., & Mertala, M. (2017). The role of educators and their challenges in distance learning in new millennium. Palma Journal, 16 (3), 423–426.

Kop, R.-P., van den Berg, M., & Klein, T. (2004). A survey into the application of ICT for educational purposes in higher education. ICT-onderwijsmonitor studiejaar 2002/2003 . Leiden: Research voor Beleid.

Lateh, H., & Muniandyb, V. (2010). ICT implementation among Malaysian schools: GIS, obstacles and opportunities. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2 (2), 2846–2850.

Lwoga, E. T., Sife, A. S., Busagala, L. S. P., & Chilimo, W. (2016). The role of universities in creating ICT awareness, literacy and expertise: Experiences from Tanzanian public universities . http://www.suaire.sua.ac.tz:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/1099

Mwalongo, A. (2011). Teachers’ perceptions about ICT for teaching, professional development, administration and personal use. International Journal of Education and Development using Information and Communication Technology (IJEDICT), 7 (3), 36–49.

Nabokina, M.E., Smirnova, Yu.V., & Tokareva E.A. (2016). The religious-philosophical intelligentsia as a sociocultural phenomenon of the early twentieth century. Collection: Actual directions of fundamental and applied research. Proceedings of the VIII International Scientific and Practical Conference (pp. 15-28). North Charleston, USA.

NCATE. (2014). Standards, procedures, and policies for the accreditation of professional education units . Washington, DC: NCATE.

Norazah, M. N., Mohamed Amin, E., & Zaidan, A. B. (2011). Integration of e-learning in teaching & learning in Malaysia Higher Education Institutions. In M. A. Embi (Ed.), e-learning in Malaysian higher education institutions: Status, trend & challenges (pp. 81–98). Putrajaya: Ministry of Higher Education.

OECD. (2015). Students, computers and learning: Making the connection. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264239555-en

Oliver, R., (2002). The role of ICT in higher education for the 21st century: ICT as a change agent for education. HE21 conference. Retrieved from www.citeseerx.ist.psu.edu .

Pelgrum, J. (2002). Schools, teachers, students and computers: A cross-national perspective. IEA-Comped Study Stage 2. University of Twente, Center for Applied Educational Research, PO Box 217, 7500 AE Enschede, The Netherlands.

Pelgrum, W., & Law, N. (2003). ICT in Education around the World: trends, problems and prospects . Paris, UNESCO: International Institute for Educational Planning.

Podrigalo, L., Iermakov, S., Rovnaya, O., Zukow, W., & Nosko, M. (2016). Peculiar features between the studied indicators of the dynamic and interconnections of mental workability of students. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 16 (4), 1211.

Rossi, P. G. (2009). Learning environment with artificial intelligence elements. Journal of e-learning and knowledge society, 5 (1), 67–75.

Sarkar, S. (2012). The Role of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) in Higher Education for the 21st Century (pp. 33–36). University Tripura, Agartala.

Sorokin, A., Korchagina, T., Niderman, I., Novikova, G., Polovnikova, A., Rezakov, R., … & Shapoval, V. (2017). Actual questions of humanitarian studies: theory, methodics, practices. Moscow: Limited Liability Company "Knigodel".

Stensaker, B., Maassen, P., Borgan, M., Oftebro, M., & Karseth, B. (2007). Use, updating and integration of ICT in higher education: Linking purpose, people and pedagog y (pp. 418–422). University of Oslo, Norway.

Šumak, B., Heričko, M., & Pušnik, M. (2011). A meta-analysis of e-learning technology acceptance: The role of user types and e-learning technology types. Computers in Human Behavior, 27 (6), 2067-2077.

Tamrakar, A., & Mehta, K. K. (2009). Analysis of effectiveness of web based e-learning through information technology. Economics, 6 , 7.

Thang, S. M., Lee, K. W., Murugaiah, P., Jaafar, N. M., Tan, C. K., & Bukhari, N. I. A. (2016). ICT tools patterns of use among Malaysian ESL undergraduates. GEMA Online® Journal of Language Studies, 16 (1).

Touray, A., Salminen, A., & Mursu, A. (2013). ICT barriers and critical success factors in developing countries. The Electronic Journal on Information Systems in Developing Countries, 56 (7), 1–17.

Umar, I. N., & Hassan, A. S. A. (2015). Malaysian teachers’ levels of ICT integration and its perceived impact on teaching and learning. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 197 , 2015–2021.

Van der Wende, M., & Van der Ven, M. (2003). The use of ICT in higher education. A Mirror of Europe . Utrecht: Lemma Publishers.

VSNU Digitisation in academic education (2017) Retrieved September 4, 2017 from https://www.vsnu.nl/files/documenten/VSNU%20Digitisation%20in%20academic%20education.pdf

Wanjala, M. S., Khaemba, E. N., & Mukwa, C. (2011). Significant factors in professional staff development for the implementation of ict education in secondary schools: A case of schools in Bungoma District, Kenya. International Journal of Curriculum and Instruction, 1 (1), 30–42.

Zamani, B. E., & Esfijani, A. (2016). Major barriers for participating in online teaching in developing countries from Iranian faculty members’ perspectives. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 32 (3), 38–49.

Zheng, B., & Warschauer, M. (2015). Participation, interaction, and academic achievement in an online discussion environment. Computers & Education, 84 , 78–89.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

MCU (Moscow City University), Moscow, Russian Federation

Elena A. Tokareva, Yulia V. Smirnova & Larisa G. Orchakova

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Elena A. Tokareva .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Tokareva, E.A., Smirnova, Y.V. & Orchakova, L.G. Innovation and communication technologies: Analysis of the effectiveness of their use and implementation in higher education. Educ Inf Technol 24 , 3219–3234 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-019-09922-2

Download citation

Received : 12 February 2019

Accepted : 23 April 2019

Published : 18 May 2019

Issue Date : 13 September 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-019-09922-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Knowledge management

- Innovation education

- Computer-based learning

- Computer literacy

- Digitalisation of higher education

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

What is ICT in Education and Its Importance

The education sector is facing many challenges nowadays. We live in a world where frequent changes occur in all sectors. The biggest instance is the corona pandemic. Who knew that this could also happen? Covid-19 has changed the whole world. Due to lockdown, everyone is working from home online. Students, educators, and all are working hard so that learning continues.

This pandemic has brought a new model of learning, which is online for people. Today, from the time we get up in the morning to the time we sleep, we are surrounded by media like newspapers, radio, TV, and computers. So, getting tech-savvy and using information and communication tools is very important in the changing society. If we use and adopt ICT in schools, our education system can prosper, and the country would become a knowledge superpower.

The three challenges that people face in using ICT tools are:

Now, schools are taking the benefits of ICT to deliver knowledge and information to children. ICT has become a core in the teaching-learning process. It has replaced blackboards with whiteboards and implemented the usage of a digital smartboard for teaching.

When teachers become tech-savvy and properly trained to use these tools, they deliver enhanced knowledge with high order thinking skills.

Before moving further, let’s first understand what ICT is?

What is ICT in Education?

ICT stands for Information and Communications Technology . As the name suggests are tools that handle information and produce, store, and disseminate information. ICT comprises of both old and new tools. Old tools include radio, TV, Telephone. New tools comprise computers, satellites, the Internet, and wireless technology.

It exists in multiple forms like audio, video, audio-visual, and texts. It refers to the latest technologies and a repository of simple audio-visual aids such as slides, radio, cassette, and film.

According to Blurton, ICT is defined as “A diverse set of technologies, tools, and resources used to communicate, create, disseminate, store, and manage information.” These technologies include computers, the internet, radio, TV, etc.

We can use information and communication technologies in the education for many reasons, but there are some practical problems in the implementation of ICT in primary education .

Why Introduce ICT in Schools?

Tools of technology like TV, Radio, Computers, the Internet, Mobile phones all play an important part in our lives. People use ICT to stay connected and become adaptable to it. ICT is an important part of our lives and has transformed it completely.

According to Cross and Adam , the four basic factors that are responsible for introducing ICT in education are as follows:

Social : Technology plays an important role in society. Students need to be made aware of technology and strive to become tech-savvy.

Vocational: Many jobs nowadays are technology-oriented.

Catalytic: Using technology tools as a great way to enhance the teaching-learning process.

Pedagogical: Technology and ICT tools as a great way to enhance learning, flexibility, and efficiency in the process of disseminating knowledge.

ICT as A Current Thinker and Adapter

There are three ways by which ICT can be considered as an important tool in education. These are as follows:

ICT education

ICT education means using trained personnel who can meet the needs and deliver information effectively to society. The vision is to train people and to equip students with ICT skills and knowledge.

ICT-supported education

It is also known as multimedia education. Around the world, many institutes and universities use ICT tools for printed study materials. It includes broadcast media, like radio, TV, audio-visual aids, etc.

ICT-enabled education

ICT-enabled education means the content is disseminated through ICT tools. Here, ICT is considered as a medium required for the teaching-learning process.

Objectives of using ICT in Education

The objectives of ICT in education include:

- Providing accessibility through online medium of education.

- Improving the quality of teaching, especially in remote areas.

- To increase transparency in the education system.

- To strengthen the policies, rules, and laws in the education system.

- To analyze the learning and participation of the students and measure its effectiveness.

- Measuring and evaluating students’ behavior, involvement, and retention in the learning process.

- To analyze students’ performance, placement, and application of knowledge.

The Importance of ICT in Education

The importance and role of ICT in education are as follows:

Online learning

ICT and its tools had led to the emergence of online learning . Through this, the teachers and the students are learning innovative ways in the education process. Online learning has gained popularity amidst the corona pandemic to ensure that the learning continues. ICTs have looked after that education reaches through it worldwide and even in remote areas. No matter where the students are, but it has ensured that every learner derives its benefits.

Accessible to all

ICT in education allows accessibility to all types of learners. All students can learn through the material provided. Even the special needs students can maximize the benefits through the usage of it. ICT has also covered issues like the “digital divide” and allows even less fortunate people to access the tools for their educational needs and enhance learning.

Higher-order thinking & skill developments

ICT promotes high order thinking and reasoning skills. These skills enabled the process of evaluation, planning, monitoring, controlling, reflecting, etc. To use ICT tools effectively, one must be able to explain and justify the solutions to the problems. For using ICTs, the students should be able to discuss, test, and evaluate the strategies and methods they use.

Better subject learning

The key role of ICT is to enhance subject learning and acquire skills. It promotes key learning in areas of literacy and numeracy.

Develops ICT literacy and capability

Literacy and capability are the 21 st -century skills that are needed. One of the best ways to develop these is to equip the subject-matter with purposeful activities.

Encourages collaboration

ICT fosters collaboration as children work collectively. It also enhances communication skills as they discuss, talk, and learn together. All you need is a laptop, tablet, or desktop computer to understand it’s working. ICT tools open up the doors for developing language through fostering communication.

Motivates learning

ICT motivates children towards learning. Children learn better through the usage of technology. They get mesmerized with technology tools and get motivated to learn effectively in the classroom or at home.

Improves engagement and knowledge retention

With the inclusion of ICT in education and its tools, children get more engaged and show greater participation in learning. It is all because of technology. It has made learning fun-filled with creativity and games. It enhances learning in multiple ways. Because of it, the students learn better, leading to knowledge retention.

Effective differentiation instruction with technology

There are varied learners with distinct learning styles in this society. So, technology does the task of providing differentiated instruction to different learners.

A key part of the curriculum

As per the latest curriculum, ICT plays an important part in the education system. So, many governments across the globe have started using ICT as a major part of education and the curriculum.

The rise of the knowledge economy

We live in an economy that is a thirst for the production and dissemination of information properly. ICT pervades at all levels and sectors like health, education, environment, or production. So, its use is needed everywhere at all levels.

Therefore, we cannot deny the fact that ICT is an important part of our lives. It fosters collaboration and connectivity around the world. Technology is ever-changing. It is likable due to certain features like growth, creativity, joy, fun, and consumption.

Importance of Students Engaging with ICT

Students should engage with ICT in order to:

- To develop 21 st -century skills like ICT Literacy and capability.

- To improve retention levels.

- Make them prepared for an integrated society that is taking advantage of the ICT developments.

- Adapt ICT tools as a lifelong partner.

Advantages of ICT in Education

Individualization of learning.

It means that people learn as an individual and not as the same group. As learners are varied, ICTs provide flexibility so that learners learn according to their own pace.

Interactivity

Through this feature of ICT, learners can learn properly at any point. They do not need to follow a proper sequence. Learners can learn effectively through this feature.

More economical, the higher speed of delivery and wider reach

ICT tools are more economical, and the speed of delivering content is also high. Through ICTs, the number of learners increases, thereby reducing the overhead cost of investment.

Multiple teaching functions and diverse audiences

ICT involves multiple functions like diagnosing and solving problems for accessing information and knowledge about various contents. It can be useful in drills and practices also.

Uniform quality

ICTs act as a great equalizer by producing uniform quality content for the rich and the poor, the urban and rural people. It produces good quality content for all.

Facilitates cooperative learning

ICT facilitates cooperative learning by encouraging dialogue, discussions through a more participative classroom environment.

Act as a motivating tool

ICT tools act as a motivator and encourage children to enhance their learning. Children get fascinated with technology. Teachers should use their skills to arouse interest, fun, and creativity to learn in a better way.

Distance and climate insensitive

- Regardless of the distance and climatic conditions, ICT tools provide access to all.

- These were some advantages of ICT in the education sector.

- Now let’s get an insight into certain disadvantages of ICT.

Disadvantages of ICT in Education

Its disadvantage depends upon the usage. They are as follows:

High Infrastructure and start-up costs

ICT tools involve high maintenance and start-up costs. The cost of hardware and software can also be very high. So, high costs act as a barrier to its accessibility.

Little attention towards individual differences to achieve economies of scale

Cost depends upon quantity. The higher the quantity, the lower the cost, and vice-versa. So, to keep the cost low, the content developed is uniform and of common quality. To keep the content common, the individual differences are not kept in mind. It creates a digital divide amongst the students. Those who are tech-savvy and familiarised with ICT tools learn better and faster than others who are not familiar with ICT tools.

Accessibility issue

This is the most common issue worldwide. Everyone does not have equal access. Some may receive great benefits, while others may not. The key accessibility factors include:

- Timing of broadcast

- Electricity

- Time constraints

These factors act as a barrier to accessibility.

Difficulty in performance evaluation

ICTs enhance learning, which is usually multidimensional in nature with a long-term goal. Hence, it leads to difficulty in evaluating performances virtually compared to classroom evaluation, which is immediate.

Continuous training requirement

Technology is ever-changing, and so is the need to train the people. As many educators and teachers are not familiar with ICT tools, they may not provide upgraded knowledge through which learning hinders among the students. Therefore, it is essential to train all the people to involve in ICT.

Attitudinal change to understand the teaching and learning

In the world of diverse media and teaching processes, there arises a need to adapt to the differentiated teaching-learning process. The goal may shift from learning to the acquisition of skills of ICTs. In this way, there is a need for change in the attitudes and mindset of people.

Common Educational Applications of ICT

One device per child.

If there is a 1:1 laptop per child, there might be issues like lower power consumption, a low-cost operating system, and special re-programming and mesh network functions. These issues for reducing costs still cannot fulfill the need to provide one laptop per child.

Tablet is a small touch screen personal gadget that can be operated without a keyboard or mouse. It is one of the best interactive learning tools as you can download and use the necessary software for learning. The interactive learning apps promote high-order thinking and reasoning skills as a result students express their understanding in a better way.

Interactive whiteboards

It is possible to display, edit, drag, click, or copy the projected computer images through interactive whiteboards or smartboards. Users can take and save handwritten notes for future reference. It is used for whole-class instruction instead of student-centric. ICT can bring high student participation and engagement.

Thousands of digitalized books can be stored on e-readers. Students find e-readers useful for independent reading. Its features include easy portability, long battery life, responsiveness to text, and the ability to define unknown text or words.

Flipped classrooms

Flipped classrooms involve multiple features like a lecture and practice through a computer anywhere. It involves computer-guided and interactive learning activities for a better understanding of the topic. The students’ viewpoint about the flipped classroom is mostly positive, but they prefer cooperative learning activities instead of attending lectures.

Featured ICT-related Projects and Activities in the Education Sector

The following projects of the Asian Development Bank are lighting up the path of education at different levels. Similar projects should be appreciated that promote ICT in education around the globe.

Secondary Education Sector Investment Program

The loan on this aims at developing effective, equitable, and high-quality education in the secondary education sector. Its result is the better use of information and communication technology for pedagogy. Its plan is to install 10 computers with the internet and its proper maintenance, equipment, and security in approximately 5000 schools.

Information and Communication Technology for better education services

It includes developing and implementing gender-inclusive ICT, identifying ICT hardware options, developing suitable applications, comprehensive evaluation of ICT access, ICT workshop to create awareness, etc.

Higher Education in the Pacific Investment Program

It aims to achieve equitable access to higher education in USP member countries, especially for women and pacific students. It is planning to provide new ICT equipment to remote campuses easily and quickly with reliable content.

ICT plays a significant role in the field of education. It helps teachers to adapt the tools and provide and disseminate effective knowledge to the students. It implemented the principle of life-long learning.

ICT in schools effectively promotes the culture of learning by sharing experiences and information with others. It has developed technology literacy among students. It supports activities involving information. These activities include gathering, processing, storing, and disseminating information.

ICT has proved and done wonders in the field of education.

Editor: Vinay Prajapati

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Digital learning policies

UNESCO helps its Member States develop and implement sector-wide policies and plans to harness the potential of ICT to ensure equitable and inclusive lifelong learning opportunities for all. For this purpose, UNESCO is developing global ICT in Education Policy Guidelines about the ways ICT can advance progress toward Education 2030 targets.

The Organization works with Ministry of Education officials and other stakeholders to establish coherent goals for ICT integration in education and then facilitates the formulation of appropriate policies and master plans to advance these goals and create enabling environments. Through its policy toolkit and workshops, the Organization helps guide the process of creating, planning and evaluating inter-sectoral or sector-wide ICT in education policies and programmes.

UNESCO also helps its Member States take stock of lessons learned in other countries. The Organization regularly publishes work examining ICT in education policies in different countries to identify best practices, analyze emerging trends, and make recommendations. It further organizes regional ICT in education ministerial forums to facilitate knowledge exchanges across borders.

Overall, UNESCO works to help countries craft policies that use the power of ICT to expand and improve education in line with SDG4.

A platform providing a step-by-step guide to create an ICT in education policy and masterplan

Related items

- Artificial intelligence

- Share full article

Advertisement

Subscriber-only Newsletter

Jessica Grose

Most teachers know they’re playing with fire when they use tech in the classroom.

By Jessica Grose

Opinion Writer

A few years ago, when researchers at Boston College and Harvard set out to review all of the existing research on educational apps for kids in preschool through third grade, they were surprised to find that even though there are hundreds of thousands of apps out there that are categorized as educational, there were only 36 studies of educational apps in the databases they searched. “That is not a strong evidence base on which to completely redesign an entire schooling system,” Josh Gilbert, one of the co-authors of the study, told me over the phone.

That said, their meta-analysis of the effects of educational app use on children’s literacy and math skills, published in 2021, found that well-designed apps can make a positive difference when it comes to “constrained skills” — things like number recognition or times tables in math, or letter sounds in literacy. Unconstrained skills are more complex ones that develop over a lifetime of learning and can deepen over the years. (It’s worth noting that many popular educational apps are not high-quality .)

Gilbert said that overall, “the range of effects was gigantic.” Because they were all over the place, “we have to go beyond the average effect and say, OK, for whom does the app work? Under what conditions? On what types of measures? And I think those are the questions that researchers, policymakers, school leaders, teachers and principals should be asking,” he said. “What are the best use cases for this digital technology in the classroom?”

In last week’s newsletter , I came in pretty hot about the pitfalls of educational technology in American classrooms. I’m convinced that since students returned to in-person school after the disruptions of 2020-21, there are too many schools that haven’t been taking a thoughtful or evidence-based approach to how they’re using screens and apps, and that it’s time for a pause and a rethink. But that doesn’t mean there are no benefits to any use of educational technology.

So for the second part of this series, I wanted to talk to people who’ve seen real upsides from using tech in their classrooms. Their experiences back up some of the available research , which shows that ed tech can help teachers differentiate their material to meet the needs of students with a wide range of proficiencies. Further, teachers report that students with disabilities can really benefit from the assistive technologies that screens and apps can provide.

Debbie Marks, who teaches third grade in Oklahoma, told me that her students’ school-issued laptops allow them “to participate in differentiated reading interventions designed specifically for them” during the school day. That differentiation allows her to better assess how each student has progressed and tailor her instruction to each student.

“So for example, we could be working on story elements and we’re working on characters,” she explained to me when we spoke. “One student might be at the point where they’re just trying to identify who the main character is. Another student might be trying to identify character traits while a higher-level student would be comparing characters or would be identifying how the character changes throughout the story based on the plot. So it really allows me to develop one-on-one lessons for every kid in my classroom.”

Marks works in a rural district, about 90 minutes away from Tulsa, and some of her students may be traveling 45 minutes to an hour just to get to class. She said that the use of devices allows her to better connect with her students’ parents and to get them more involved in what’s going on in a classroom that is physically far from them. Marks also said that screens enable her to do things like virtual author visits, which she says get the kids really excited and engaged in reading.

I also heard from several teachers who said that assistive technology has been a game changer for students with special needs. Duncan Law, who works as a special education support teacher in an elementary school in Oregon, put it this way: “Technology can be a necessity for students with special needs in accessing core curriculum/standards, as well as for fluency practice. In the best case scenario, learning via tech is guided and closely monitored by teachers, and students are actively engaged with feedback. For students with dysgraphia and dyslexia, word processing tools offer a meaningful way to demonstrate/assess their writing skills.”

Several middle school and high school teachers who said that tech was helpful in their classrooms seemed to be using it as an efficient way to teach students more rote tasks, allowing more class time to be spent helping build those “unconstrained” skills.

Doug Showley, a high school English teacher in Indiana who’s been teaching since 1996, gave me the example of how he has changed his quizzes over time by integrating technology. He used to just give straight-up vocabulary quizzes where students had to define words; now he and his colleagues have moved toward “diction quizzes,” requiring students to understand the nuances of using specific words in sentences.

Showley noted that it’s easier to quickly look up words than it was in the hard-copy dictionary days, and that his students “have access to online dictionaries” during these quizzes. They’re given four synonyms and are asked to figure out which synonym best fits into a sentence. “To determine that, they have to go beyond just that basic definition. They’ve got to get into the connotative meaning of the word and the common usage of the word,” he explained.

But Showley also said that he monitors the kids quite closely. When they’re doing a task that involves their laptops, he’ll have them set up so all of their screens are facing him. He estimates that usually only one or two kids out of a class of 25 really aren’t able to stay on task when they’re on the screens.

He also told me that his school has made the decision not to block A.I., including ChatGPT, though it is a hot topic of discussion. The challenge of dealing with A.I. is something that came up a lot among teachers in the upper grades, and the overall vibe I got was that no one quite knows what to do with it yet.

After we spoke, Showley emailed me to say that “we should carefully gauge to what degree and in what way tech is used at each level of education.” And he wrote something that I think really sums up both the promise and the peril of ed tech (and is also such a classic English teacher passage):

I couldn’t help but think of Prometheus defying the Olympic gods by sharing the first-ever technological advancement with humankind: fire. Fire, as with every other significant advancement since, both propelled society forward and burnt it to the ground. It enlightened our minds and souls, and it tormented them, just as Prometheus was perpetually tormented through his punishment for sharing too much of the gods’ power.

Perhaps deliberately, one of the popular digital whiteboards is the Promethean board.

The technology isn’t going away. We need to start creating better frameworks to think about how students and teachers are using technology in our schools, because the tech companies won’t stop pushing their products, whether or not there’s evidence that shows educational gains. CNN’s Clare Duffy reports that later this year, Meta “will launch new software for educators that aims to make it easier to use its V.R. headsets in the classroom,” though “it remains unclear just how useful virtual reality is in helping students learn better.”