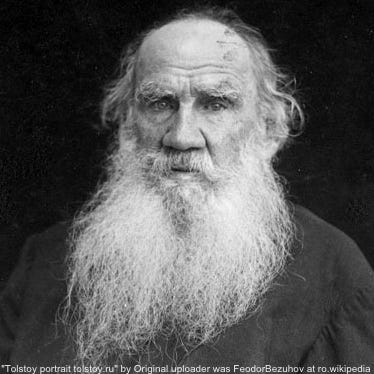

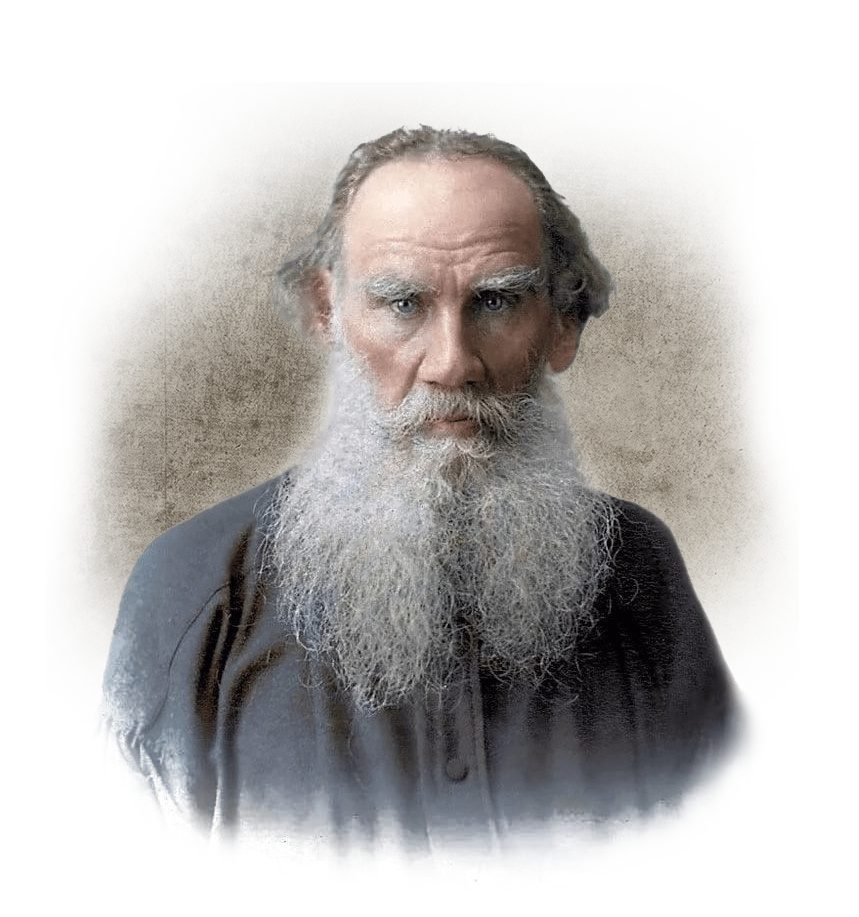

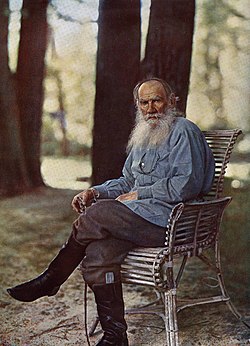

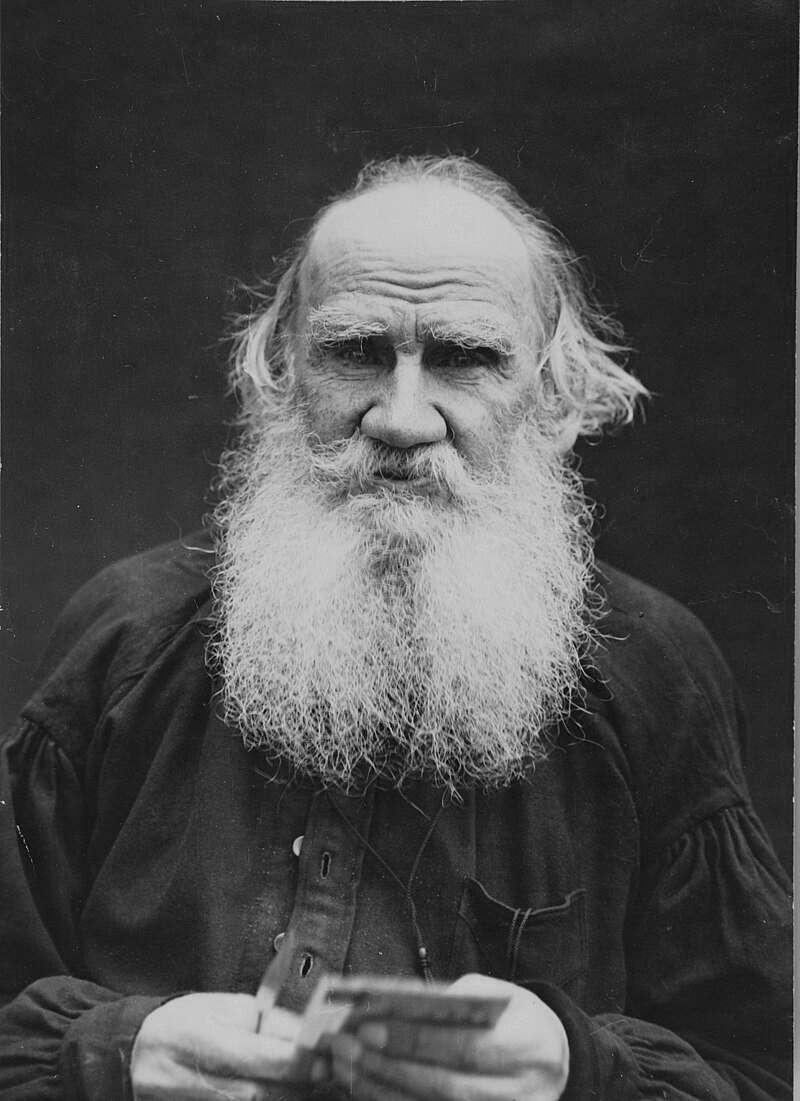

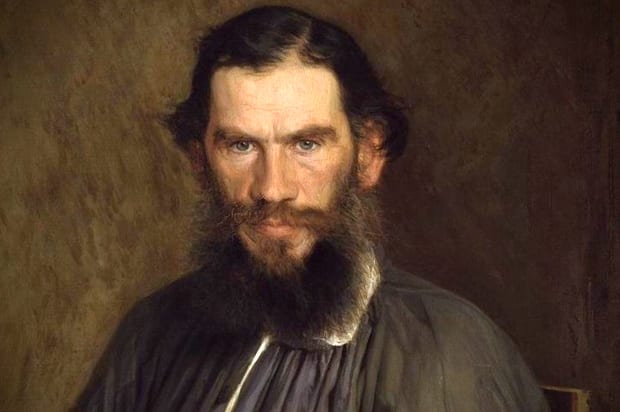

Leo Tolstoy

(1828-1910)

Who Was Leo Tolstoy?

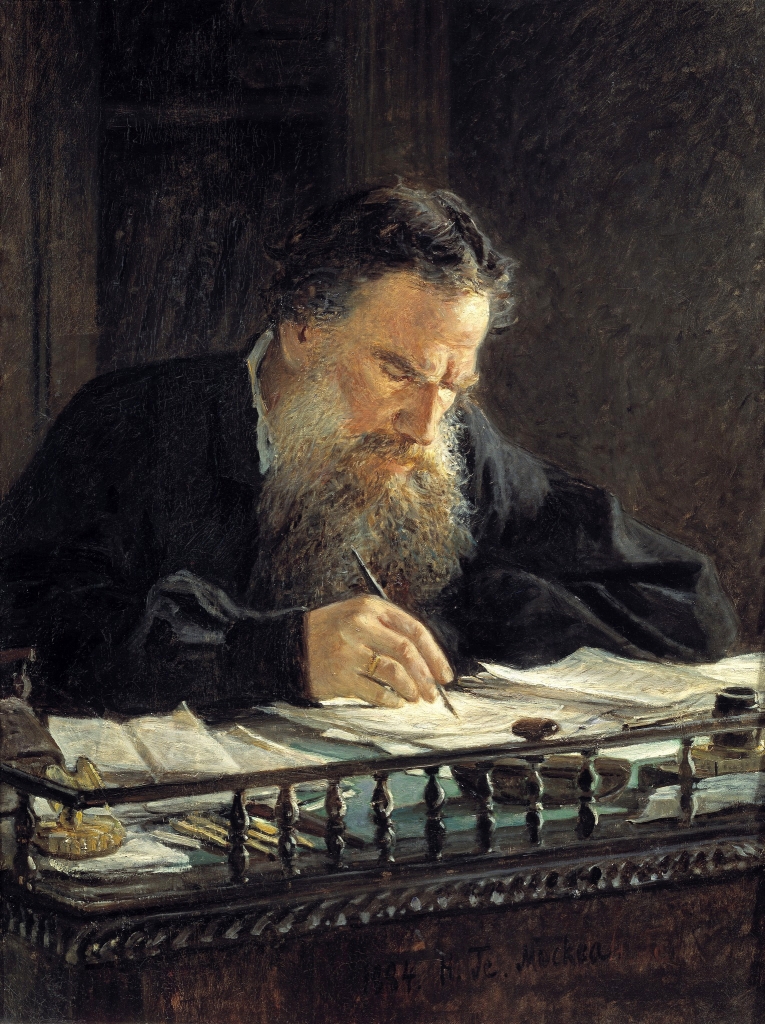

In the 1860s, Russian author Leo Tolstoy wrote his first great novel, War and Peace . In 1873, Tolstoy set to work on the second of his best-known novels, Anna Karenina . He continued to write fiction throughout the 1880s and 1890s. One of his most successful later works was The Death of Ivan Ilyich .

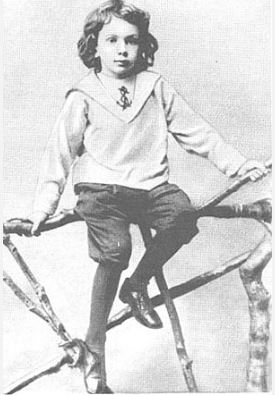

On September 9, 1828, writer Leo Tolstoy was born at his family's estate, Yasnaya Polyana, in the Tula Province of Russia. He was the youngest of four boys. When Tolstoy's mother died in 1830, his father's cousin took over caring for the children. When their father, Count Nikolay Tolstoy, died just seven years later, their aunt was appointed their legal guardian. When the aunt passed away, Tolstoy and his siblings moved in with a second aunt, in Kazan, Russia. Although Tolstoy experienced a lot of loss at an early age, he would later idealize his childhood memories in his writing.

Tolstoy received his primary education at home, at the hands of French and German tutors. In 1843, he enrolled in an Oriental languages program at the University of Kazan. There, Tolstoy failed to excel as a student. His low grades forced him to transfer to an easier law program. Prone to partying in excess, Tolstoy ultimately left the University of Kazan in 1847, without a degree. He returned to his parents' estate, where he made a go at becoming a farmer. He attempted to lead the serfs, or farmhands, in their work, but he was too often absent on social visits to Tula and Moscow. His stab at becoming the perfect farmer soon proved to be a failure. He did, however, succeed in pouring his energies into keeping a journal — the beginning of a lifelong habit that would inspire much of his fiction.

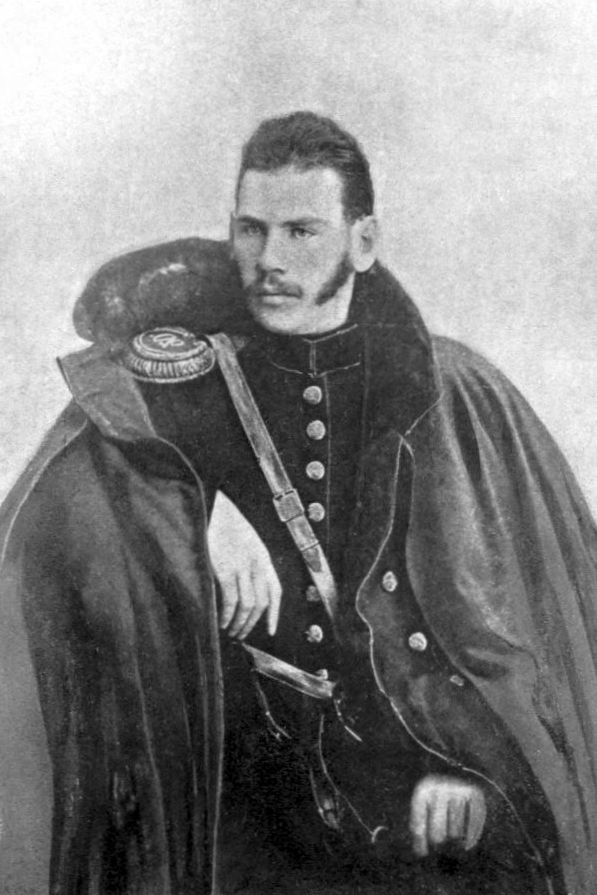

As Tolstoy was flailing on the farm, his older brother, Nikolay, came to visit while on military leave. Nikolay convinced Tolstoy to join the Army as a junker, south in the Caucasus Mountains, where Nikolay himself was stationed. Following his stint as a junker, Tolstoy transferred to Sevastopol in Ukraine in November 1854, where he fought in the Crimean War through August 1855.

Early Works

During quiet periods while Tolstoy was a junker in the Army, he worked on an autobiographical story called Childhood . In it, he wrote of his fondest childhood memories. In 1852, Tolstoy submitted the sketch to The Contemporary , the most popular journal of the time. The story was eagerly accepted and became Tolstoy's very first published work.

After completing Childhood , Tolstoy started writing about his day-to-day life at the Army outpost in the Caucasus. However, he did not complete the work, entitled The Cossacks , until 1862, after he had already left the Army.

Tolstoy still managed to continue writing while at battle during the Crimean War. During that time, he composed Boyhood (1854), a sequel to Childhood , the second book in what was to become Tolstoy's autobiographical trilogy. In the midst of the Crimean War, Tolstoy also expressed his views on the striking contradictions of war through a three-part series, Sevastopol Tales . In the second Sevastopol Tales book, Tolstoy experimented with a relatively new writing technique: Part of the story is presented in the form of a soldier's stream of consciousness.

Once the Crimean War ended and Tolstoy left the Army, he returned to Russia. Back home, the burgeoning author found himself in high demand on the St. Petersburg literary scene. Stubborn and arrogant, Tolstoy refused to ally himself with any particular intellectual school of thought. Declaring himself an anarchist, he made off to Paris in 1857. Once there, he gambled away all of his money and was forced to return home to Russia. He also managed to publish Youth , the third part of his autobiographical trilogy, in 1857.

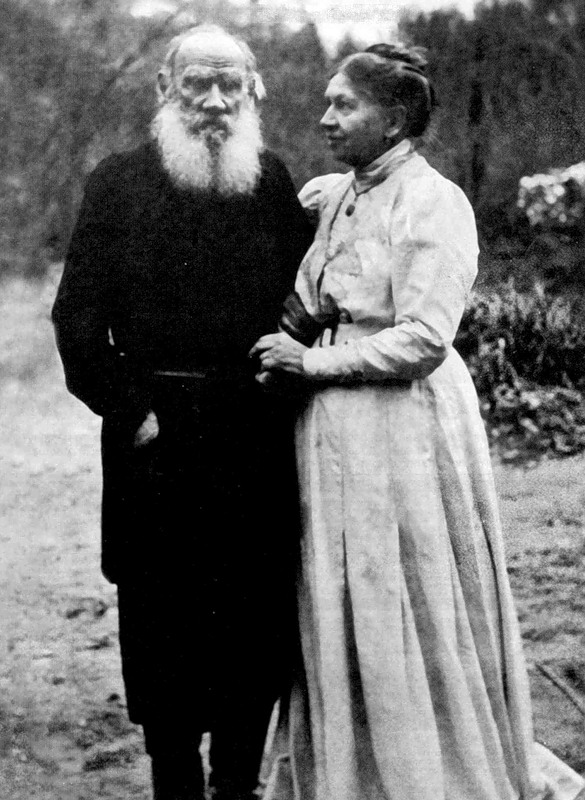

Back in Russia in 1862, Tolstoy produced the first of a 12 issue-installment of the journal Yasnaya Polyana , marrying a doctor's daughter named Sofya Andreyevna Bers that same year.

'War and Peace'

Residing at Yasnaya Polyana with his wife and children, Tolstoy spent the better part of the 1860s toiling over his first great novel, War and Peace . A portion of the novel was first published in the Russian Messenger in 1865, under the title "The Year 1805." By 1868, he had released three more chapters and a year later, the novel was complete. Both critics and the public were buzzing about the novel's historical accounts of the Napoleonic Wars, combined with its thoughtful development of realistic yet fictional characters. The novel also uniquely incorporated three long essays satirizing the laws of history. Among the ideas that Tolstoy extols in War and Peace is the belief that the quality and meaning of one's life is mainly derived from his day-to-day activities.

'Anna Karenina'

Following the success of War and Peace , in 1873, Tolstoy set to work on the second of his best-known novels, Anna Karenina . Like War and Peace , Anna Karenina fictionalized some biographical events from Tolstoy's life, as was particularly evident in the romance of the characters Kitty and Levin, whose relationship is said to resemble Tolstoy's courtship with his own wife.

The first sentence of Anna Karenina is among the most famous lines of the book: "All happy families resemble one another, each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way." Anna Karenina was published in installments from 1873 to 1877, to critical and public acclaim. The royalties that Tolstoy earned from the novel contributed to his rapidly growing wealth.

Philosophy, Religious Conversion

Despite the success of Anna Karenina , following the novel's completion, Tolstoy suffered a spiritual crisis and grew depressed. Struggling to uncover the meaning of life, Tolstoy first went to the Russian Orthodox Church but did not find the answers he sought there. He came to believe that Christian churches were corrupt and, in lieu of organized religion, developed his own beliefs. He decided to express those beliefs by founding a new publication called The Mediator in 1883.

As a consequence of espousing his unconventional — and therefore controversial — spiritual beliefs, Tolstoy was ousted by the Russian Orthodox Church. He was even watched by the secret police. When Tolstoy's new beliefs prompted his desire to give away his money, his wife strongly objected. The disagreement put a strain on the couple's marriage until Tolstoy begrudgingly agreed to a compromise: He conceded to granting his wife the copyrights — and presumably the royalties — to all of his writing predating 1881.

Later Fiction

'the death of ivan ilyich'.

In addition to his religious tracts, Tolstoy continued to write fiction throughout the 1880s and 1890s. Among his later works' genres were moral tales and realistic fiction. One of his most successful later works was the novella The Death of Ivan Ilyich , written in 1886. In Ivan Ilyich , the main character struggles to come to grips with his impending death. The title character, Ivan Ilyich, comes to the jarring realization that he has wasted his life on trivial matters, but the realization comes too late.

In 1898, Tolstoy wrote Father Sergius , a work of fiction in which he seems to criticize the beliefs that he developed following his spiritual conversion. The following year, he wrote his third lengthy novel, Resurrection . While the work received some praise, it hardly matched the success and acclaim of his previous novels. Tolstoy's other late works include essays on art, a satirical play called The Living Corpse that he wrote in 1890, and a novella called Hadji-Murad (written in 1904), which was discovered and published after his death.

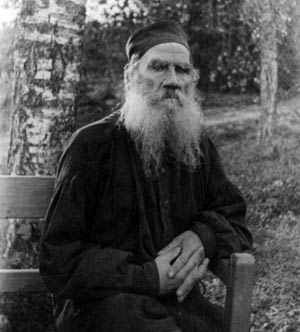

Elder Years

Also during his later years, Tolstoy reaped the rewards of international acclaim. Yet he still struggled to reconcile his spiritual beliefs with the tensions they created in his home life. His wife not only disagreed with his teachings, but she also disapproved of his disciples, who regularly visited Tolstoy at the family estate. Their troubled marriage took on an air of notoriety in the press. Anxious to escape his wife's growing resentment, in October 1910, Tolstoy, his daughter, Aleksandra, and his physician, Dr. Dushan P. Makovitski, embarked on a pilgrimage. Valuing their privacy, they traveled incognito, hoping to dodge the press, to no avail.

Death and Legacy

Unfortunately, the pilgrimage proved too arduous for the aging novelist. In November 1910, the stationmaster of a train depot in Astapovo, Russia opened his home to Tolstoy, allowing the ailing writer to rest. Tolstoy died there shortly after, on November 20, 1910. He was buried at the family estate, Yasnaya Polyana, in Tula Province, where Tolstoy had lost so many loved ones yet had managed to build such fond and lasting memories of his childhood. Tolstoy was survived by his wife and their brood of 8 children. (The couple had spawned 13 children in all, but only 10 had survived past infancy.)

To this day, Tolstoy's novels are considered among the finest achievements of literary work. War and Peace is, in fact, frequently cited as the greatest novel ever written. In contemporary academia, Tolstoy is still widely acknowledged as having possessed a gift for describing characters' unconscious motives. He is also championed for his finesse in underscoring the role of people's everyday actions in defining their character and purpose.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Leo Tolstoy

- Birth Year: 1828

- Birth date: September 9, 1828

- Birth City: Tula Province (Yasnaya Polyana)

- Birth Country: Russia

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Russian author Leo Tolstoy wrote the acclaimed novels 'War and Peace,' 'Anna Karenina' and 'The Death of Ivan Ilyich,' and ranks among the world's top writers.

- Fiction and Poetry

- Astrological Sign: Virgo

- University of Kazan

- Death Year: 1910

- Death date: November 20, 1910

- Death City: Astapovo

- Death Country: Russia

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Leo Tolstoy Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/authors-writers/leo-tolstoy

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: November 14, 2019

- Original Published Date: September 9, 2014

- I put men to death in war, I fought duels to slay others. I lost at cards, wasted the substance wrung from the sweat of peasants, punished the latter cruelly, rioted with loose women, and deceived men. Lying, robbery, adultery of all kinds, drunkenness, violence, and murder, all were committed by me, not one crime omitted, and yet I was not the less considered by my equals to be a comparatively moral man. Such was my life for ten years.

Famous Authors & Writers

9 Surprising Facts About Truman Capote

William Shakespeare

How Did Shakespeare Die?

Meet Stand-Up Comedy Pioneer Charles Farrar Browne

Francis Scott Key

Christine de Pisan

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

10 Famous Langston Hughes Poems

5 Crowning Achievements of Maya Angelou

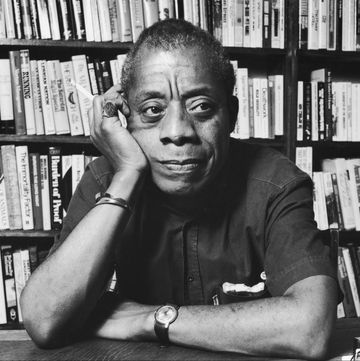

10 Black Authors Who Shaped Literary History

The True Story of Feud:Capote vs. The Swans

Biography of Leo Tolstoy, Influential Russian Writer

The great Russian novelist and philosophical writer

Hulton Archive / Getty Images

- Authors & Texts

- Top Picks Lists

- Study Guides

- Best Sellers

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/ThoughtCo_Amanda_Prahl_webOG-48e27b9254914b25a6c16c65da71a460.jpg)

- M.F.A, Dramatic Writing, Arizona State University

- B.A., English Literature, Arizona State University

- B.A., Political Science, Arizona State University

Leo Tolstoy (September 9, 1828-November 20, 1910) was a Russian writer, best known for his epic novels . Born into an aristocratic Russian family, Tolstoy wrote realist fiction and semi-autobiographical novels before shifting into more moral and spiritual works.

Fast Facts: Leo Tolstoy

- Full Name: Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy

- Known For: Russian novelist and writer of philosophical and moral texts

- Born : September 9, 1828 in Yasnaya Polyana, Russian Empire

- Parents: Count Nikolai Ilyich Tolstoy and Countess Mariya Tolstoya

- Died: November 20, 1910 in Astapovo, Russian Empire

- Education: Kazan University (began at age 16; did not complete his studies)

- Selected Works: War and Peace (1869), Anna Karenina (1878), A Confession (1880), The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886), Resurrection (1899)

- Spouse: Sophia Behrs (m. 1862)

- Children: 13, including Count Sergei Lvovich Tolstoy, Countess Tatiana Lvona Tolstoya, Count Ilya Lvovich Tolstoy, Count Lev Lvovich Tolstoy, and Countess Alexandra Lvona Tolstoya

- Notable Quote: “There can be only one permanent revolution—a moral one; the regeneration of the inner man. How is this revolution to take place? Nobody knows how it will take place in humanity, but every man feels it clearly in himself. And yet in our world everybody thinks of changing humanity, and nobody thinks of changing himself."

Tolstoy was born into a very old Russian aristocratic family whose lineage was, quite literally, the stuff of Russian legend. According to family history, they could trace their family tree back to a legendary nobleman named Indris, who had left the Mediterranean region and arrived in Chernigov, Ukraine, in 1353 with his two sons and an entourage of approximately 3,000 people. His descendant then was nicknamed “Tolstiy,” meaning “fat,” by Vasily II of Moscow , which inspired the family name. Other historians trace the family’s origins to 14th or 16th-century Lithuania, with a founder named Pyotr Tolstoy.

He was born on the family’s estate, the fourth of five children born to Count Nikolai Ilyich Tolstoy and his wife, the Countess Maria Tolstoya. Because of the conventions of Russian noble titles, Tolstoy also bore the title of “count” despite not being his father’s eldest son. His mother died when he was 2 years old, and his father when he was 9, so he and his siblings were largely brought up by other relatives. In 1844, at age 16, he began studying law and languages at Kazan University, but was apparently a very poor student and soon left to return to a life of leisure.

Tolstoy did not marry until his thirties, after the death of one of his brothers hit him hard. On September 23, 1862, he married Sophia Andreevna Behrs (known as Sonya), who was only 18 at the time (16 years younger than him) and was the daughter of a doctor at court. Between 1863 and 1888, the couple had 13 children; eight survived to adulthood. The marriage was, reportedly, happy and passionate in the early days, despite Sonya’s discomfort with her husband’s wild past, but as time went on, their relationship deteriorated into deep unhappiness.

Travels and Military Experience

Tolstoy’s journey from dissolute aristocrat to socially agitating writer was shaped heavily by a few experiences in his youth; namely, his military service and his travels in Europe. In 1851, after running up significant debts from gambling, he went with his brother to join the army. During the Crimean War , from 1853 to 1856 , Tolstoy was an artillery officer and served in Sevastopol during the famous 11-month siege of the city between 1854 and 1855.

Although he was commended for his bravery and promoted to lieutenant, Tolstoy did not like his military service. The gruesome violence and heavy death toll in the war horrified him, and he left the army as soon as possible after the war ended. Along with some of his compatriots, he embarked on tours of Europe: one in 1857, and one from 1860 to 1861.

During his 1857 tour, Tolstoy was in Paris when he witnessed a public execution. The traumatic memory of that experience shifted something in him permanently, and he developed a deep loathing and mistrust of government in general. He came to believe that there was no such thing as good government, only an apparatus to exploit and corrupt its citizens, and he became a vocal advocate of non-violence. In fact, he corresponded with Mahatma Gandhi about the practical and theoretical applications of non-violence.

A later visit to Paris, in 1860 and 1861, produced further effects in Tolstoy which would come to fruition in some of his most famous works. Soon after reading Victor Hugo’s epic novel Les Miserables , Tolstoy met Hugo himself. His War and Peace was heavily influenced by Hugo, particularly in its treatment of war and military scenes. Similarly, his visit to the exiled anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon gave Tolstoy the idea for his novel’s title and shaped his views on education. In 1862, he put those ideals to work, founding 13 schools for Russian peasant children in the aftermath of Alexander II’s emancipation of the serfs. His schools were among the first to run on the ideals of democratic education—education which advocates democratic ideals and runs according to them–but were short-lived due to the enmity of the royalist secret police.

Early and Epic Novels (1852-1877)

- Childhood (1852)

- Boyhood (1854)

- Youth (1856)

- "Sevastopol Sketches" (1855–1856)

- The Cossacks (1863)

- War and Peace (1869)

- Anna Karenina (1877)

Between 1852 and 1856, Tolstoy focused on a trio of autobiographical novels: Childhood , Boyhood , and Youth . Later in his career, Tolstoy criticized these novels as being overly sentimental and unsophisticated, but they’re quite insightful about his own early life. The novels are not direct autobiographies, but instead tell the story of a rich man’s son who grows up and slowly realizes that there is an insurmountable gap between him and the peasants who live on the land owned by his father. He also wrote a trio of semi-autobiographical short stories, Sevastopol Sketches , which depicted his time as an army officer during the Crimean War .

For the most part, Tolstoy wrote in the realist style, attempting to accurately (and with detail) convey the lives of the Russians he knew and observed. His 1863 novella, The Cossacks , provided a close look at the Cossack people in a story about a Russian aristocrat who falls in love with a Cossack girl. Tolstoy’s magnum opus was 1869’s War and Peace , a massive and sprawling narrative encompassing nearly 600 characters (including several historical figures and several characters strongly based on real people Tolstoy knew). The epic story deals with Tolstoy’s theories about history, spanning many years and moving through wars , family complications, romantic intrigues, and court life, and ultimately intended as an exploration of the eventual causes of the 1825 Decembrist revolt . Interestingly, Tolstoy did not consider War and Peace to be his first “real” novel; he considered it a prose epic, not a true novel .

Tolstoy believed his first true novel to be Anna Karenina , published in 1877. The novel follows two major plotlines which intersect: an unhappily married aristocratic woman’s doomed affair with a cavalry officer, and a wealthy landowner who has a philosophical awakening and wants to improve the peasantry’s way of life. It covers personal themes of morality and betrayal, as well as larger social questions of the changing social order, contrasts between city and rural life, and class divisions. Stylistically, it lies at the juncture of realism and modernism.

Musings on Radical Christianity (1878-1890)

- A Confession (1879)

- Church and State (1882)

- What I Believe (1884)

- What Is to Be Done? (1886)

- The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886)

- On Life (1887)

- The Love of God and of One's Neighbour (1889)

- The Kreutzer Sonata (1889)

After Anna Karenina , Tolstoy began further developing the seeds of moral and religious ideas in his earlier works into the center of his later work. He actually criticized his own earlier works, including War and Peace and Anna Karenina , as not being properly realistic. Instead, he began developing a radical, anarcho-pacifist, Christian worldview that explicitly rejected both violence and the rule of the state.

Between 1871 and 1874, Tolstoy tried his hand at poetry, branching out from his usual prose writings. He wrote poems about his military service, compiling them with some fairy tales in his Russian Book for Reading , a four-volume publication of shorter works that was intended for an audience of schoolchildren. Ultimately, he disliked and dismissed poetry.

Two more books during this period, the novel The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886) and the non-fiction text What Is to Be Done? (1886), continued developing Tolstoy’s radical and religious views, with harsh critiques of the state of Russian society. His Confession (1880) and What I Believe (1884) declared his Christian beliefs, his support of pacifism and complete non-violence, and his choice of voluntary poverty and asceticism.

Political and Moral Essayist (1890-1910)

- The Kingdom of God Is Within You (1893)

- Christianity and Patriotism (1894)

- The Deception of the Church (1896)

- Resurrection (1899)

- What Is Religion and What is its Essence? (1902)

- The Law of Love and the Law of Violence (1908)

In his later years, Tolstoy wrote almost solely about his moral, political, and religious beliefs. He developed a firm belief that the best way to live was to strive for personal perfection by following the commandment to love God and love one’s neighbor, rather than following the rules set by any church or government on earth. His thoughts eventually garnered a following, the Tolstoyans, who were a Christian anarchist group devoted to living out and spreading Tolstoy’s teachings.

By 1901, Tolstoy’s radical views led to his excommunication from the Russian Orthodox Church , but he was unperturbed. In 1899, he had written Resurrection , his final novel, which critiqued the human-run church and state and attempted to expose their hypocrisy. His criticism extended to many of the foundations of society at the time, including private property and marriage. He hoped to continue spreading his teachings throughout Russia.

For the last two decades of his life, Tolstoy largely focused on essay writing. He continued advocating for his anarchist beliefs while also cautioning against the violent revolution espoused by many anarchists . One of his books, The Kingdom of God Is Within You , was one of the formative influences on Mahatma Gandhi’s theory of nonviolent protest, and the two men actually corresponded for a year, between 1909 and 1910. Tolstoy also wrote significantly in favor of the economic theory of Georgism, which posited that individuals should own the value they produce, but society should share in the value derived from the land itself.

Literary Styles and Themes

In his earlier works, Tolstoy was largely concerned with depicting what he saw around him in the world, particularly at the intersection of the public and private spheres. War and Peace and Anna Karenina , for instance, both told epic stories with serious philosophical underpinnings. War and Peace spent significant time criticizing the telling of history, arguing that it’s the smaller events that make history, not the huge events and famous heroes. Anna Karenina , meanwhile, centers on personal themes such as betrayal, love, lust and jealousy, as well as turning a close eye on the structures of Russian society, both in the upper echelons of the aristocracy and among the peasantry.

Later in life, Tolstoy’s writings took a turn into the explicitly religious, moral, and political. He wrote at length about his theories of pacifism and anarchism, which tied into his highly individualistic interpretation of Christianity as well. Tolstoy’s texts from his later eras were no longer novels with intellectual themes, but straightforward essays, treatises, and other non-fiction work. Asceticism and the work of inner perfection were among the things Tolstoy advocated for in his writings.

Tolstoy did, however, get politically involved, or at least publicly expressed his opinions on major issues and conflicts of the day. He wrote in support of the Boxer rebels during the Boxer Rebellion in China, condemning the violence of the Russian, American, German, and Japanese troops. He wrote on revolution, but he considered it an internal battle to be fought within individual souls, rather than a violent overthrow of the state.

Over the course of his life, Tolstoy wrote in a wide variety of styles. His most famous novels contained sweeping prose somewhere between the realist and modernist styles, as well as a particular style of seamlessly sweeping from quasi-cinematic, detailed but massive descriptions to the specifics of characters’ perspectives. Later, as he shifted away from fiction into non-fiction, his language became more overtly moral and philosophical.

By the end of his life, Tolstoy had reached a breaking point with his beliefs, his family, and his health. He finally decided to separate from his wife Sonya, who vehemently opposed many of the ideas and was intensely jealous of the attention he gave his followers over her. In order to escape with the least amount of conflict, he slipped away secretively, leaving home in the middle of the night during the cold winter.

His health had been declining, and he had renounced the luxuries of his aristocratic lifestyle. After spending a day traveling by train, his destination somewhere in the south, he collapsed due to pneumonia at the Astapovo railway station. Despite the summoning of his personal doctors, he died that day, on November 20, 1910. When his funeral procession went through the streets, police tried to limit access, but they were unable to stop thousands of peasants from lining the streets—although some were there not because of devotion to Tolstoy, but merely out of curiosity about a nobleman who had died.

In many ways, Tolstoy’s legacy cannot be overstated. His moral and philosophical writings inspired Gandhi, which means that Tolstoy’s influence can be felt in contemporary movements of non-violent resistance. War and Peace is a staple on countless lists of the best novels ever written, and it has remained highly praised by the literary establishment since its publication.

Tolstoy’s personal life, with its origins in the aristocracy and his eventual renunciation of his privileged existence, continues to fascinate readers and biographer, and the man himself is as famous as his works. Some of his descendants left Russia in the early 20th century, and many of them continue to make names for themselves in their chosen professions to this day. Tolstoy left behind a literary legacy of epic prose, carefully drawn characters, and a fiercely felt moral philosophy, making him an unusually colorful and influential author across the years.

- Feuer, Kathryn B. Tolstoy and the Genesis of War and Peace . Cornell University Press, 1996.

- Troyat, Henri. Tolstoy . New York: Grove Press, 2001.

- Wilson, A.N. Tolstoy: A Biography . W. W. Norton Company, 1988.

- Top 10 Books for High School Seniors

- Quotes From Leo Tolstoy's Classic 'Anna Karenina'

- Notable Writers from European History

- The Greatest Works of Russian Literature Everyone Should Read

- "Anna Karenina" Study Guide

- Memorable Quotes of Leo Tolstoy Quotes

- The 19 Best Books on the Napoleonic Wars

- Biography of Mohandas Gandhi, Indian Independence Leader

- Biography of Sam Houston, Founding Father of Texas

- Papa Panov's Special Christmas: Synopsis and Analysis

- Biography of George Eliot, English Novelist

- Russian Nicknames and Diminutives

- Biography of Tipu Sultan, the Tiger of Mysore

- Julia Ward Howe Biography

- A List of Every Nobel Prize Winner in Literature

- Biography of Walt Whitman, American Poet

Biography Online

Leo Tolstoy Biography

Leo Tolstoy was one of the world’s pre-eminent writers becoming famous through his epic novels War and Peace and Anna Karenina . War and Peace has been ranked as one of the greatest novels of all time, for its rich characterisation and sweeping view of Russian society. Tolstoy also became a leading critic of injustice, formal religion and the inequality of Tsarist Russia. While critical of the church, he believed in the essence of gospels and espoused a form of primitive Christianity. In politics, his exposition of pacifism and non-violence had a profound influence on others – most notably Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King.

“The hero of my tale, whom I love with all the power of my soul, whom I have tried to portray in all his beauty, who has been, is, and will be beautiful, is Truth.”

– Leo Tolstoy

Short Bio – Leo Tolstoy

In his early life, he struggled with his studies and drifted through life ending up with large gambling debts. Fed up with his aimless and empty life he volunteered to serve in the Russian army. However, these experiences as a soldier led him to become a pacifist in later life. He wrote his battlefield observations in Sevastopol Sketches , and this raised his profile as a leading Russian writer, gaining the attention even of the current Tsar. Later, looking back on these years (in his Confessions 1882), he bitterly regretted his misspent years

“I cannot recall those years without horror, loathing, and heart-rending pain. I killed people in war, challenged men to duels with the purpose of killing them, and lost at cards; I squandered the fruits of the peasants’ toil and then had them executed; I was a fornicator and a cheat. Lying, stealing, promiscuity of every kind, drunkenness, violence, murder — there was not a crime I did not commit… Thus I lived for ten years.” – Leo Tolstoy

Tolstoy had a deep interest in seeking a greater understanding and justification of life. He travelled widely through Europe but became increasingly disenchanted with the materialism of the European Bourgeoisie. He could be argumentative with those he disagreed with such as Turgenev (widely considered the greatest Russian writer of his generation). He also developed an increasing sympathy with peasants, the poor, and those downtrodden from society. He went out of his way to help and serve them.

War and Peace is breathtaking in its scope, realism and sense of history. Some characters were real historical people; others were invented. It tells a narrative of two families set against the backdrop of the Napoleonic Wars. Tolstoy never saw it as a novel but an epic. Amongst other themes, it suggests the necessity of making the best of life, whatever your situation.

“Seize the moments of happiness, love and be loved! That is the only reality in the world, all else is folly. It is the one thing we are interested in here.”

– Leo Tolstoy from War and Peace

Religious views of Tolstoy

After writing War and Peace and Anna Karenina , Tolstoy underwent a change of religious and philosophical attitude. Influenced by Buddhism and Jesus Christ’s ‘Sermon on the Mount’ he developed a belief in spiritual renewal based on service to the poor and direct relationship with God. He noted his attitudes in ‘The Kingdom of Heaven is within you’ and ‘Confessions’.

“The sole meaning of life is to serve humanity by contributing to the establishment of the kingdom of God, which can only be done by the recognition and profession of the truth by every man.”

Leo Tolstoy , The Kingdom of Heaven is within You.

His religious views could be described as an early form of Christianity – based on the direct teachings of Jesus Christ, but without the external edifice of religious institutions and ‘myths’ such as the Holy Trinity and Eucharist. Tolstoy felt the power and influence of the church diluted the spiritual essence of religion. Due to his criticism of the Orthodox Church, he was ex-communicated from the church but his legacy as a writer and unique thinker was enhanced throughout the world. His philosophy began to attract disciples, and idealistic Tolstoy communes began to form.

Political views

His religious views also had a direct impact on his political views. He was critical of injustice, greed and the inequality that tended to dominate Tsarist Russia. He developed a pacifist/anarchist philosophy, and became supportive of civil disobedience to improve the welfare of the oppressed. However, his criticism of the Tsar and Russian class system meant the government started to spy on Tolstoy. He was too internationally famous to directly challenge him, but Tolstoy’s strident criticism of the aristocracy was worrying for the authorities.

Life and death

Tolstoy was interested in the meaning of life and death. During his own life, he witnessed the painful death of his brother from tuberculosis, multiple deaths in the Crimean War and a public guillotining in Paris (which contributed to his rejection of the death penalty). He wrote on this theme of death in his short novel Death of Ivan Ilyich. He completed the book in 1882, but it fell foul of Russian censorship and it was not published until 1886. It is written after his religious conversion and touches on the distinction between what gives life value – sympathy, concern and love – and the ‘artificial life’ of social climbing and outer material displays. It is also critical of the attitudes of his former colleagues and friends who are embarrassed by the inconvenience of his fatal illness, but in the novel, he praises the selfless action of a peasant (Gerasim) who turns out to be Ivan’s greatest friend in his painful moments of dying.

Friendship with Gandhi

In the evening of his life, he developed a close relationship with a young Mahatma Gandhi . Tolstoy had written an article supporting Indian independence and Gandhi requested permission to republish it in a South African newspaper. This led to a long correspondence where the two wrote to each other on religious and political matters. Tolstoy wrote to Gandhi.

“Love is the only way to rescue humanity from all ills, and in it you too have the only method of saving your people from enslavement… Love, and forcible resistance to evil-doers, involve such a mutual contradiction as to destroy utterly the whole sense and meaning of the conception of love.” – Letters One from Tolstoy to Gandhi

Gandhi was very impressed with Tolstoy’s belief in non-violent resistance, vegetarianism and brand of ‘anarchist Christianity’. Gandhi later became a pre-eminent proponent of non-violent resistance and credited Tolstoy with being a major inspiration in his religious and political outlook.

Death of Tolstoy

On 28 October 1910, Tolstoy left his family home outside Moscow, leaving a note to his wife saying:

“I am doing what old men of my age usually do: leaving worldly life to spend the last days of my life in solitude and quiet,”

However a few days, later he was taken ill on a train passing through a remote Russian village called Astapovo. Suffering from pneumonia, Tolstoy was taken off the train and looked after at the station master’s house. His final days created worldwide media interest with media outlets sending reporters to cover whether Tolstoy would recover. However, his condition steadily worsened and he began slipping in and out of consciousness. On 7 November 1910, he passed away.

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan . “ Biography of Leo Tolstoy ”, Oxford, UK www.biographyonline.net . Last updated 4 March 2020. Originally published 22nd Jan. 2009.

Tolstoy: A Russian Life at Amazon

Quotes on Tolstoy

Gandhi said of Tolstoy “the greatest apostle of non-violence that the present age has produced”

Virginia Woolf went on to declare him “greatest of all novelists”

James Joyce said of Tolstoy “He is never dull, never stupid, never tired, never pedantic, never theatrical”

Fyodor Dostoevsky thought him the greatest of all living writers

Related pages

- Quotes by Leo Tolstoy

Leo Tolstoy

Great Russian writer

"Everyone thinks of changing the world, but no one thinks of changing himself"

Date and place of birth: August 28, 1828, Yasnaya Polyana, Tula province Date and place of death: November 7, 1910, Astapovo station, Ryazan province Occupation: prose writer, publicist, teacher, philosopher, writer, playwright. Movement: realism. Genre: short story, novel, drama Years of oeuvre: 1847-1910

Leo Tolstoy – Russian writer and thinker, participated in the defense of Sevastopol, was engaged in educational and journalistic activities. He was at the origins of Tolstoyism, a new religious movement.

Childhood and Youth

Leo Tolstoy was born on August 28, 1828, on his mother’s birthplace, Yasnaya Polyana, in Tula province. His father was Count Nikolai Tolstoy, a descendant of the ancient family of the Tolstoys, who were in the service of Ivan the Terrible and Peter the Great. His mother belonged to the Volkonsky family, descendants of the Ruriks. Leo Tolstoy and the poet Alexander Pushkin had a common ancestor, Ivan Golovin, admiral of the tsarist navy.

Lev’s mother died shortly after giving birth to her daughter, and Lev was not even two years old at the time. Lev was the fourth child in a noble family. His father did not outlive his mother by much; he died seven years after her death.

The children were orphaned, and their upbringing was undertaken by their aunt, T.A. Ergolskaya. After some time, the duties of guardian passed to a second aunt – A.M. Osten-Saken, who had the title of Count. When she died, the children settled in Kazan in the family of their father’s sister P.I.Yushkova, who became their new guardian. It was 1840. Auntie had a great influence on Leo Tolstoy, the years spent with her, he called the happiest period of his life. Her house was always full of guests, it was considered the most hospitable and cheerful in Kazan. Childhood impressions of living in this family are reflected in his work “Childhood”.

Leo Tolstoy passed the elementary school program at home. He was taught by French and German teachers. In 1843, Tolstoy became a student in the Faculty of Oriental Languages at Kazan University. He was not particularly interested in languages, so his grades were very low. This was an incentive to change the faculty. Tolstoy gave preference to the Faculty of Law. However, even this change did not give the result, two years later he left the university altogether, and remained without a degree.

Tolstoy returned to his ancestral home, Yasnaya Polyana. He had a plan to arrange his life in a new way, to live in harmony with the peasantry. Nothing came out of this venture, but during this period, he wrote down all his observations in his diary, drawing conclusions. In addition, the young Earl Tolstoy was often seen at social gatherings, and for practicing music. He could listen to his favorite composers for hours. Lev spent a summer on his native estate and realized that the life of a landlord was not to his liking. He left the village and immediately settled in Moscow, and then moved to St. Petersburg. At this time he was trying to define himself in life, so he diligently prepared for the examinations at the university, played music, played cards, and partied with gypsies. He simultaneously wanted to be a civil servant and a cadet in the cavalry regiment. His relatives exclusively saw him as a “trifling little fellow”, unfit for anything, and hardly had time to pay his debts.

In 1851, Lev heeded the advice of his brother Nicholas, who at that time already had the rank of officer, and left for the Caucasus. For three years he lived in a village along the Terek River. The local nature and the way of life of the Cossacks Tolstoy then colorfully described in his works – “Hadji Murat”, “Cossacks”, “Logging”, “Raid”.

It was during his stay in the Caucasus that his story called “Childhood” was born, which was printed by the Sovremennik magazine. Tolstoy did not sign his last name, under the publication were the initials L.N. Following this, the young writer created a sequel to the story, which were called “Adolescence” and “Youth”. These stories were combined into a trilogy. The debut in literature was successful, and gave a powerful impetus to the development of the creative biography. Leo Tolstoy became a famous writer.

Soon Leo Tolstoy was assigned to Bucharest, then found himself in the besieged Sevastopol, where he commanded a battery. These events in life did not go unnoticed, the writer reflected them in his works. The “Sevastopol Stories” were published, which were highly appreciated by the critics. They found in the cycle of stories a bold psychological analysis. According to Nikolai Chernyshevsky, these stories were inherent “dialectics of the soul. Emperor Alexander II himself admired the creative abilities of the writer, and he especially liked the story “Sevastopol in December”.

In 1855 Leo Tolstoy again settled in St. Petersburg and became a member of the circle called “Sovremennik”. The 28-year-old writer was received very cordially, he was called nothing less than “the great hope of Russian literature. For a year, Lev attended all the meetings of the circle, attended literary readings, engaged in arguments and conflicts, attended literary dinners. Until he realized that these people disgusted him, and he was no longer happy with himself.

In 1856 he left St. Petersburg and settled again in Yasnaya Polyana. But he stayed there only until January 1857, and then he went abroad. For six months he visited Italy, Germany, Switzerland, and France. On his return, Tolstoy lived briefly in Moscow, and then settled back in Yasnaya Polyana. He had the idea to teach the children of the peasants, and Lev with great zeal began to open educational institutions for them. Thanks to the writer’s efforts, soon there were two dozen schools in the vicinity of his estate.

Tolstoy loved children, and created for them many cautionary tales and stories that breathed with kindness. He wrote fairy tales called “Two Brothers,” “The Kitten,” “The Lion and the Dog,” and “The Hedgehog and the Hare.

Leo Tolstoy was the author of the school handbook “The ABCs,” which included four books. They made it easy for children to learn to write, count, and read. The manual consists of byliny, stories, and fables. In addition, there are tips for teachers. The third book contains the story “Prisoner of the Caucasus.

In addition to teaching peasant children, Tolstoy continued his literary activities. In 1870, he sat down to write the novel Anna Karenina, which consisted of two main plot lines. Against the background of the unfolding family drama of the Karenin couple, very striking looked the idyll of the landowner Levin, whom the writer wrote almost from himself. At first glance, it might seem that the novel is just a love story. In fact, it touches on the meaning of life for the rich and educated, especially in comparison with the lives of the common people.

Gradually the writer’s worldview changes, he begins to talk more and more about social inequality, about the idleness of the life of the ruling class – the nobility. This can be seen in the works that Tolstoy wrote in the 1880s. Among them we want to highlight “Kreutzer Sonata”, “Death of Ivan Ilyich”, “After the Ball”, “Father Sergius”.

Leo Tolstoy began to wonder more and more about the meaning of human life; he tried to find an answer from Orthodox priests, but received nothing but disappointment. He decided that corruption ruled the church, and that priests only covered themselves in the name of faith, but were in fact promoting false doctrine. In 1883, Tolstoy became the founder of The Mediator, in which he expounded at length on his beliefs and in which he mercilessly criticized the Russian Orthodox Church. This prompted his excommunication and close surveillance by the secret police. In 1898 another novel by Leo Tolstoy, Resurrection, was published, which was also praised by the critics. However, this work did not create such a furor as Anna Karenina and War and Peace.

Personal Life

Leo Tolstoy’s wife was an 18-year-old girl Sophia Bers. Their marriage took place in 1862, when the writer was already 34. The couple’s family life lasted almost half a century, but the writer’s cloudless happiness did not work out in his personal life.

Soon after the wedding, Tolstoy let his wife read his diary – he wanted his wife to know everything about him. Sophia was struck by the descriptions of her husband’s adventures, his wild life and his passion for playing cards. She also found out about the existence of the peasant woman Aksinya, who was pregnant by Tolstoy.

In 1863, their first child, their son Sergei, was born. When Tolstoy began working on his novel War and Peace, Sophia, even though she was pregnant, did her best to help him work. A total of thirteen children were born to the couple, but five of them died as babies. Sophia Andreevna gave all of them home schooling.

The first crisis in family relations began after Tolstoy wrote Anna Karenina. He became depressed and dissatisfied with everything. He was irritated by the well-organized life, which was lovingly arranged by his wife. His depressive state was expressed in the fact that he gave up smoking, drinking and eating meat, and he demanded this from his family. Tolstoy forced his family to dress like peasants, and he made outfits for everyone with his own hands. Lev Nikolaevich was going to give away all the family property to the peasants, and God only knows what efforts it took Sophia to dissuade him from taking such a rash step.

Tolstoy agreed, but the couple quarreled and he left home. Upon his return, he had his daughters rewrite drafts of his manuscript.

The spouses briefly reconciled when their last child, son Vanya, died. However, full understanding in the family never came. Sofya tried to console herself with music, and even took lessons from a Moscow teacher. A liking emerged between them, but it went no further than that. They remained friends, but Tolstoy called it a “half-change” and did not forgive his wife. The couple finally quarreled in October 1910. The writer left, leaving a farewell message for his wife, in which he confessed his love for her, but said he was forced to leave her.

Religious Views

“The essence of any religion consists only in the answer to the question, why do I live and what is my attitude towards the infinite world surrounding me. There is not a single religion, from the most exalted to the most brutal, which would not have as its basis this establishment of the relation of man to the world around him” – Leo Tolstoy.

Tolstoy’s life teaching was influenced by a variety of ideological currents: the Baha’i Faith, Brahmanism, Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, Islam, Quakerism, as well as the teachings of moral philosophers (Socrates, the late Stoics, Kant, Schopenhauer). The idea of considering Christianity as a doctrine of non-resistance to evil is independent. Tolstoy denied the resurrection of Christ, Christianity is perceived by him only as an ethical teaching. The Tolstoyans reject the dogmas of the organized church, public worship, do not recognize the church hierarchy, the clergy, but place high moral principles of Christianity. The Tolstoyans criticized the Orthodox Church and the official religion in general, as well as state violence and social inequality.

“ True religion is such an attitude to the infinite life around him, established by man, which connects his life with this infinity and guides his actions” – Leo Tolstoy.

Religious views within the framework of Tolstoyism are characterized by syncretism. Tolstoy believed that “in essence, all definitions of the meaning of life, revealed to people by the greatest minds of mankind, are the same.” Having offered his own interpretations of the Gospel, he believed that he was clearing the teachings of Christ from historical distortions. The Tolstoyans rejected the dogmas of the Christian Church and professed antitrinitarianism.

“Faith is the understanding of the meaning of life and the recognition of the obligations arising from this understanding” – Leo Tolstoy.

At the end of October, Tolstoy and his personal doctor D. Makovitsky, who accompanied him, left Yasnaya Polyana. The writer was 82 years old at the time. He fell ill on the train and was forced to get off at a station called Astapovo. His last shelter before his death was the station warden’s cottage, where he remained for seven days. His wife and children came to see Tolstoy, but he refused to see them. Leo Tolstoy died on November 7, 1910. The cause of death was pneumonia. The place of repose of the writer was Yasnaya Polyana. Sophia Andreevna died nine years later.

- War and Peace

Leo Tolstoy

- Literature Notes

- Leo Tolstoy Biography

- Book Summary

- Character List

- Summary and Analysis

- Book I: Chapters 1–6

- Book I: Chapters 7–21

- Book I: Chapters 22–25

- Book II: Chapters 1–8

- Book II: Chapters 9–21

- Book III: Chapters 1–5

- Book III: Chapters 6–8

- Book III: Chapters 9–19

- Book IV: Chapters 1–6

- Book IV: Chapters 7–9

- Book IV: Chapters 10–16

- Book V: Chapters 1–14

- Book V: Chapters 15–22

- Book VI: Chapters 1–10

- Book VI: Chapters 11–26

- Book VIII: Chapters 1–5

- Book VIII: Chapters 6–22

- Book IX: Chapters 1–7

- Book IX: Chapters 8–15

- Book IX: Chapters 16–23

- Book X: Chapters 1–14

- Book X: Chapters 15–25

- Book X: Chapters 26–39

- Book XI: Chapters 1–12

- Book XI: Chapters 13–29

- Book XI: Chapters 30–34

- Book XII: Chapters 1–13

- Book XII: Chapters 14–16

- Book XV: Chapters 1–3

- Book XV: Chapters 4–11

- Book XV: Chapters 12–20

- First Epilogue

- Second Epilogue

- Character Analysis

- Pierre Bezuhov

- Prince Andrey Bolkonsky

- Natasha Rostov

- Nikolay Rostov

- Historical Figures

- Critical Essays

- Structure of War and Peace

- Themes in War and Peace

- Technical Devices Used in War and Peace

- Essay Questions

- Cite this Literature Note

Leo Nicolaevich Tolstoy (1828-1910) was the next to youngest of five children, descending from one of the oldest and best families in Russia. His youthful surroundings were of the upper-class gentry of the last period of serfdom. Though his life spanned the westernization of Russia, his early intellectual and cultural education was the traditional 18th-century training. Lyovochka (as he was called) was a tender, affection-seeking child who liked to do things"out of the ordinary." Self-consciousness was one of his youthful attributes, and this process of self-scrutiny continued all his life. Indeed, Tolstoy's life is one of the best documented accounts we have of any writer, for the diaries he began at 17 he continued through old age.

In 1844 Leo attended the University of Kazan, then one of the great seats of learning east of Berlin. He early showed a contempt for academic learning but became interested enough at the faculty of jurisprudence (the easiest course of study) to attend classes with some regularity. Kazan, next to St. Petersburg and Moscow, was a great social center for the upper class. An eligible, titled young bachelor, Tolstoy devoted his energies to engage in the brilliant social life of his set. But his homely peasant face was a constant source of embarrassment and Tolstoy took refuge in queer and original behavior. His contemporaries called him"Lyovochka the bear," for he was always stiff and awkward.

Before his second-year examinations, Tolstoy left Kazan to settle at his ancestral estate, Yasnaya Polyana (Bright Meadow), which was his share of the inheritance. Intending to farm and devote himself to improve the lot of his peasants, Tolstoy's youthful idealism soon vanished as he confronted the insurmountable distrust of the peasantry. He set off for Moscow in 1848 and for two years lived the irregular and dissipated life led by young men of his class. The diaries of this period reveal the critical self-scrutiny with which he regarded all his actions, and he itemized each deviation from his code of perfect behavior. Carnal lust and gambling were those passions most difficult for him to exorcise. As he closely observed the life around him in Moscow, Tolstoy experienced an irresistible urge to write. This time was the birth of the creative artist, and the following year saw the publication of his first story, Childhood.

Tolstoy began his army career in 1852, joining his brother Nicolai in the Caucasus. Garrisoned among a string of Cossack outposts on the borders of Georgia, Tolstoy participated in occasional expeditions against the fierce Chechenians, the Tartar natives rebelling against Russian rule. He spent the rest of his time gambling, hunting, fornicating.

Torn amidst his inner struggle between his bad and good impulses, Tolstoy arrived at a sincere belief in God, though not in the formalized sense of the Eastern Church. The wild primitive environment of the Caucasus satisfied Tolstoy's intense physical and spiritual needs. Admiring the free, passionate, natural life of the mountain natives, he wished to turn his back forever on sophisticated society with its falseness and superficiality.

Soon after receiving his commission, Tolstoy fought among the defenders at Sevastopol against the Turks. In his Sevastopol sketches he describes with objectivity and compassion the matter-of-fact bravery of the Russian officers and soldiers during the siege.

By now he was a writer of nationwide reputation, and when he resigned from the army and went to Petersburg, Turgenev offered him hospitality. With the leader of the capital's literary world as sponsor, Tolstoy became an intimate member of the circle of important writers and editors. But he failed to get on with these litterateurs: He had no respect for their ideal of European progress, and their intellectual arrogance appalled him. His lifelong antagonism with Turgenev typified this relationship.

His travels abroad in 1857 started Tolstoy toward his lifelong revolt against the whole organization of modern civilization. To promote the growth of individual freedom and self-awareness, he started a unique village school at Yasnaya Polyana based on futuristic progressive principles. The peasant children"brought only themselves, their receptive natures, and the certainty that it would be as jolly in school today as yesterday." But the news of his brother's illness interrupted his work. Traveling to join Nicolai in France, he first made a tour of inspection throughout the German school system. He was at his brother's side when Nicolai died at the spa near Marseilles, and this death affected him deeply. Only his work saved him from the worst depressions and sense of futility he felt toward life.

The fundamental aim of Tolstoy's nature was a search for truth, for the meaning of life, for the ultimate aims of art, for family happiness, for God. In marriage his soul found a release from this never-ending quest, and once approaching his ideal of family happiness, Tolstoy entered upon the greatest creative period of his life.

In the first 15 years of his marriage to Sonya (Sofya Andreyevna Bers) the great inner crisis he later experienced in his"conversion" was procrastinated, lulled by the triumph of spontaneous life over questioning reason. While his nine children grew up, his life was happy, almost idyllic, despite the differences which arose between him and the wife 16 years his junior. As an inexperienced bride of 18, the city-bred Sonya had many difficult adjustments to make. She was the mistress of a country estate as well as the helpmate of a man whose previous life she had not shared. Her constant pregnancies and boredom and loneliness marred the great love she and Tolstoy shared. In this exhilarating period of his growing family, Tolstoy created the epic novels War and Peace and Anna Karenina while Sonya, rejoicing at his creative genius, faithfully turned his rough drafts into fair copy.

Toward the end of 1866, while writing Anna Karenina, Tolstoy entered on the prolonged and fateful crisis which resulted in his conversion. He recorded part of this spiritual struggle in Anna Karenina. The meaning of life consists in living according to one's"inner goodness," he concluded. Only through emotional and religious commitment can one discover this natural truth. Uniquely interpreting the Gospels, Tolstoy discovered Christ's entire message was contained in the idea"that ye resist not evil." This doctrine of"non-resistance" became the foundation of Tolstoyism, where one lived according to nature, renouncing the artificial refinements of society. Self-gratification, Tolstoy believed, perverted man's inherent goodness. Therefore property rights — ownership by one person of"things that belong to all" — is a chief source of evil. Carnal lust, ornamental clothing, and fancy food are other symptoms of the corrupting influence of civilization. In accordance with his beliefs, Tolstoy renounced all copyrights to his works since 1881, divided his property among his family members, dressed in peasant homespun, ate only vegetables, gave up liquor and tobacco, engaged in manual work, and even learned to cobble his own boots. Renouncing creative art on account of its corrupt refinements, Tolstoy wrote polemic tracts and short stories which embodied his new faith.

But the incongruity of his ideals and his actual environment grieved Tolstoy. With his family, he lived in affluence. His wife and children (except for Alexandra) disapproved of his philosophy. As they became more estranged and embittered by their differences, Sonya's increasing hysteria made his latter years a torment for Tolstoy.

All three stages of Tolstoy's life and writings (pre-conversion, conversion, effects of conversion) reflect the single quest of his career: to find the ultimate truth of human existence. After finding this truth, his life was a series of struggles to practice his preachings. He became a public figure both as a sage and an artist during his lifetime, and Yasnaya Polyana became a mecca for a never-ceasing stream of pilgrims. The intensity and heroic scale of his life have been preserved for us from the memoirs of friends and family and wisdom-seeking visitors. Though Tolstoy expressed his philosophy and theory of history with the same thoroughness and lucidity he devoted to his novels, he is known today chiefly for his important contributions to literature. Although his artistic influence is wide and still pervasive, few writers have achieved the personal stature with which to emulate his epic style.

Previous Historical Figures

Next Structure of War and Peace

Culture History

Leo Tolstoy

Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910) was a Russian writer and philosopher, renowned for his epic novels such as “War and Peace” and “Anna Karenina.” His literary works explore complex themes like morality, spirituality, and the human condition. Tolstoy’s philosophical writings also had a profound impact, emphasizing nonviolent resistance and a simple, ethical life. His ideas influenced figures like Mahatma Gandhi and continue to resonate in both literary and philosophical circles.

Tolstoy was born into an aristocratic family with a rich lineage. His parents, Count Nikolai Ilyich Tolstoy and Countess Mariya Tolstaya, provided him with a privileged upbringing. The family estate, Yasnaya Polyana, served as the backdrop to Tolstoy’s early years. Surrounded by vast landscapes, Tolstoy developed a deep connection with nature, a theme that would later find resonance in his literary works.

As a young boy, Tolstoy lost his mother to illness, an event that left a lasting impact on him. His education was diverse, marked by periods of formal schooling, private tutors, and extensive reading of classical literature. He displayed an early interest in literature and wrote his first story, “The Raid,” at the age of nine. The young Tolstoy’s exposure to European and Russian literature laid the foundation for his future endeavors.

In 1844, Tolstoy enrolled at Kazan University, but his academic pursuits were short-lived. He found the formal education system stifling and preferred independent study. His desire for knowledge led him to read widely, exploring philosophy, ethics, and the works of Enlightenment thinkers. This intellectual curiosity marked the beginning of Tolstoy’s lifelong exploration of existential questions and moral philosophy.

In 1851, Tolstoy joined the Russian army and served in the Crimean War. His experiences on the battlefield influenced his later writings, particularly his war epic “War and Peace.” Tolstoy’s observations of the brutality and futility of war left a deep impression on him, shaping his evolving views on human nature and the pursuit of peace.

After the war, Tolstoy returned to Yasnaya Polyana and immersed himself in agricultural and educational pursuits. He sought to improve the lives of the serfs on his estate, experimenting with educational reforms and advocating for social justice. These efforts reflected Tolstoy’s growing concern for the well-being of the common people and marked the beginning of his critique of social inequalities.

In 1862, Tolstoy married Sofya Andreyevna Bers, and the couple went on to have thirteen children. Their marriage, while enduring for many years, was not without challenges. Sofya, a strong-willed and intelligent woman, played a significant role in supporting Tolstoy’s literary endeavors, even transcribing his handwritten drafts. However, tensions arose over time, exacerbated by Tolstoy’s evolving spiritual beliefs and his pursuit of a simpler, ascetic lifestyle.

Tolstoy’s literary career took a significant turn with the publication of “War and Peace” in serialized form between 1865 and 1869. This monumental work, often considered one of the greatest novels ever written, weaves a complex narrative against the backdrop of the Napoleonic Wars. Through vivid characters and intricate plotlines, Tolstoy explores themes of history, fate, and the human condition. The novel showcases his keen insight into human psychology and his ability to capture the nuances of society.

Following the success of “War and Peace,” Tolstoy embarked on another ambitious project, “Anna Karenina,” serialized from 1873 to 1877. This tragic tale of love and betrayal delves into the complexities of human relationships and societal expectations. Tolstoy’s exploration of morality and the consequences of one’s actions resonated with readers and established him as a literary giant.

Despite his literary acclaim, Tolstoy began to grapple with existential questions that went beyond the realms of fiction. A deep spiritual crisis led him to question the meaning of life, the pursuit of happiness, and the nature of morality. Tolstoy’s quest for a genuine and purposeful existence led him to adopt a form of Christian anarchism and embrace a philosophy he termed “Christianity Not as a Mystical Teaching but as a New Concept of Life.”

In his later years, Tolstoy became increasingly critical of the Russian Orthodox Church and the institutionalization of religion. He rejected organized forms of worship and advocated for a personal, direct relationship with God. His theological writings, including “The Kingdom of God Is Within You,” inspired individuals such as Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. , who admired Tolstoy’s commitment to nonviolence and social justice.

Tolstoy’s evolving philosophy extended to his lifestyle choices. He renounced his aristocratic privileges, embraced a simpler way of life, and became a vocal critic of materialism and inequality. Tolstoy’s writings on pacifism and nonresistance to evil influenced movements such as Tolstoyanism and had a lasting impact on the development of nonviolent resistance.

The latter part of Tolstoy’s life was marked by a tumultuous relationship with his wife, Sofya, and conflicts with the Russian government. His criticism of state power, the church, and private property led to tension with authorities, and his works were censored. In 1910, Tolstoy left Yasnaya Polyana in a self-imposed exile, accompanied by his physician, Dr. Dushan Makovitsky.

Tragically, Leo Tolstoy’s life came to an end on November 20, 1910, at the railway station in Astapovo, Russia. He fell ill during the journey and passed away, surrounded by those who accompanied him in his final moments. Tolstoy’s death marked the conclusion of a remarkable life that spanned the worlds of literature, philosophy, and social activism.

Leo Tolstoy’s legacy endures through his literary masterpieces, philosophical writings, and advocacy for social justice. His exploration of the human condition, moral dilemmas, and the pursuit of a meaningful life continues to resonate with readers around the globe. Tolstoy’s influence extends beyond literature, touching on realms as diverse as pacifism, spirituality, and the critique of societal norms. His life and works remain a testament to the enduring power of ideas and the impact that a single individual can have on the course of history.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

FAMOUS AUTHORS

Leo Tolstoy

Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy was a Russian author best known for his novels War and Peace and Anna Karenina which are considered to be the greatest novels of realist fiction. Tolstoy is also regarded as world’s best novelist by many. In addition to writing novels, Tolstoy also authored short stories, essays and plays. Also a moral thinker and a social reformer, Tolstoy held severe moralistic views. In later life, he became a fervent Christian anarchist and anarcho-pacifist. His non-violent resistance approach towards life has been expressed in his works such as The Kingdom of God is Within You, which is known to have a profound effect on important 20th century figures, particularly, Martin Luther King Jr. and Mohandas Gandhi.

Born in Yasnaya Polyana on September 9, 1828, Leo Tolstoy belonged to a well known noble Russian family. He was the fourth among five children of Count Nikolai Ilyich Tolstoy and Countess Mariya Tolstaya, both of whom died leaving their children to be raised by relatives. Wanting to enter the faculty of Oriental languages at Kazan University, Tolstoy prepared for the entry examination by studying Arabic, Turkish, Latin, German, English, and French, also geography, history, and religion. In 1844, Tolstoy was accepted into Kazan University. Unable to graduate beyond the second year, Tolstoy returned to Yasnava Polyana and then spent time travelling between Moscow and St. Petersburg. With some working knowledge of several languages, he became a polyglot. The newly found youth attracted Tolstoy towards drinking, visiting brothels and most of all gambling which left him in heavy debt and agony but Tolstoy soon realized he was living a brutish life and once again attempted university exams in the hope that he would obtain a position with the government, but ended but up in Caucusus serving in the army following in the footsteps of his elder brother. It was during this time that Tolstoy began writing.

In 1862, Leo Tolstoy married Sophia Andreevna Behrs, mostly called Sonya, who was 16 years younger than him. The couple had thirteen children, of which, five died at an early age. Sonya acted as Tolstoy’s secretary, proof-reader and financial manager while he composed two of his greatest works. Their early married life was filled with contentment. However, Tolstoy’s relationship with his wife deteriorated as his beliefs became increasingly radical to the extent of disowning his inherited and earned wealth.

Tolstoy began writing his masterpiece, War and Peace in 1862. The six volumes of the work were published between 1863 and 1869. With 580 characters fetched from history and others created by Tolstoy, this great novel takes on exploring the theory of history and the insignificance of noted figures such as Alexander and Napoleon. Anna Karenina, Tolstoy’s next epic was started in 1873 and published completely in 1878. Among his earliest publications are autobiographical works such as Childhood, Boyhood and Youth (1852-1856). Although they are works of fiction, the novels reveal aspects of Leo’s own life and experiences. Tolstoy was a master of writing about the Russian society, evidence of which is displayed in The Cossacks (1863). His later works such as The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886) and What Is to Be Done? (1901) focus on Christian themes.

In his late years, Tolstoy became increasingly inclined towards ascetic morality and believed sternly in the Sermon on the Mount and non violent resistance. On November 20, 1910, Leo Tolstoy died at the age of 82 due to pneumonia.

Buy Books by Leo Tolstoy

Recent posts.

- 10 Famous Russian Authors You Must Read

- 10 Famous Indian Authors You Must Read

- 10 Famous Canadian Authors You Must Read

- Top 10 Christian Authors You Must Read

- 10 Best Graphic Novels Of All Time

- 10 Best Adult Coloring Books Of All Time

- 10 Best Adventure Books of All Time

- 10 Best Mystery Books of All Time

- 10 Best Science Fiction Books Of All Time

- 12 Best Nonfiction Books of All Times

- Top 10 Greatest Romance Authors of All Time

- 10 Famous Science Fiction Authors You Must Be Reading

- Top 10 Famous Romance Novels of All Time

- 10 Best Children’s Books of All Time

- 10 Influential Black Authors You Should Read

- 16 Stimulating WorkPlaces of Famous Authors

- The Joy of Books

- Art History

- U.S. History

- World History

Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy, popularly known as Leo Tolstoy, was born in the Tula Province of Russia in September of 1828. Tolstoy was a Great Russian writer who wrote novels and short stories. His work was centered around realistic fiction and he is still considered one of the greatest novelists of all time.

Birth and Early Years

Leo Tolstoy was born into a noble and well-known Russian family. He was the fourth youngest kid amongst five children in the family. Leo’s mother died when he was very young, and father also passed away after some time. Tolstoy and his siblings were raised by relatives. Tolstoy began studying law in 1844, along with oriental languages. However, Tolstoy could never develop great interest in his studies and therefore left them in between.

Tolstoy’s teachers described him as a student who was uninterested and unable to learn. After leaving the university, he spent much of his time in St. Petersburg and Moscow. Tolstoy ran into huge debt due to gambling, which made him move in with his elder brother and join the army. It was around this time Tolstoy started writing. Leo’s two trips to Europe in 1857 and 1860 influenced his literary and political development significantly. He was inspired by Victor Hugo during his European visits, and his writings also drew inspiration from Hugo’s work and writing style as well.

Tolstoy’s Personal Life

In 1862, Tolstoy got married to Sophia Andreevna Behrd, who was 16 years younger than him. Sophia was a court physician’s daughter. The two went on to have a big family, with both having thirteen children between 1863 and 1888. The marriage from the beginning was driven by sexual passion and lack of emotional sensitivity.

Despite Tolstoy disclosing his extensive pre-marital sexual past with Sophia, the early part of their marriage is believed to be very happy and Sophia helped Leo in writing novels and even acted as a proofreader and financial manager. However, it is believed that their relationship turned sour later on due to Tolstoy’s belief turning extremely radical with the times.

Tolstoy’s Work and Achievements

Leo Tolstoy started writing at the age of 24. He published his first short novel Childhood , which like Boyhood and Youth that followed, was inspired by Tolstoy’s own early years.

Leo Tolstoy’s famous work includes the epic War and Peace . It took him seven years (1862 to 1869) to finish the four volumes of this epic. The novel tells the story of several families against the background of Napoleon’s 1812 invasion of Russia.

Another one of the greatest works of Tolstoy includes Anna Karenina , which is known as the most popular realist fiction ever written. The story is about the doomed affair between a high-society woman trapped in a passionless marriage and a dashing officer. Several movies have been made based on this fictional work.

Tolstoy also wrote three plays and a lot of short stories, including Two Hussars , The Kossacks , Master and Man , Father Sergius and Hadji Murad . Most of his stories were based on the problems and the influence of materialism on simple men. In the latter years of Tolstoy’s life, his educational ideas were adopted not only in Russia, but also in other countries.

Tolstoy’s Non-Fiction Works

All of these books were based on social, religious, spiritual and even artistic matters. His later works, such as The Death of Ivan Ilyich and What Is to Be Done are focused on Christian themes. His works have been published many times in enormous editions in all languages. His literary work is included in the school curriculum, and his educational writings are studied at special teacher-training establishments at different levels.

Tolstoy’s Later Years

Despite his fame, his wealth, and his happy family life, Tolstoy was dissatisfied with himself. In his later years, he became increasingly inclined towards ascetic morality and believed sternly in the Sermon on the Mount and non-violent resistance. Mahatma Gandhi was deeply moved by his book, The Kingdom of God is Within You , and he wrote to Tolstoy about his nonviolent resistance movement and their correspondence led to a warm friendship.

Tolstoy died in 1910 at the age of 82. He died of pneumonia after falling sick when he tried to run away from his wife, with whom the relationship had turned very sour.

Newest Additions

- The Beheading of John the Baptist

- Jesus Sends Out His Twelve Apostles

- The Miracle of Healing: Jesus and the Paralytic

- Parables of Wisdom: The Teachings of Jesus

- Jesus’ Response to John’s Disciples

Copyright © 2020 · Totallyhistory.com · All Rights Reserved. | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy | Contact Us

- World Biography

Leo Tolstoy Biography

Born: August 28, 1828 Tula Province, Russia Died: November 9, 1910 Astapovo, Russia Russian novelist

The Russian novelist and moral philosopher (person who studies good and bad in relation to human life) Leo Tolstoy ranks as one of the world's great writers, and his War and Peace has been called the greatest novel ever written.

Early years

Leo (Lev Nikolayevich) Tolstoy was born at Yasnaya Polyana, his family's estate, on August 28, 1828, in Russia's Tula Province, the youngest of four sons. His mother died when he was two years old, whereupon his father's distant cousin Tatyana Ergolsky took charge of the children. In 1837 Tolstoy's father died, and an aunt, Alexandra Osten-Saken, became legal guardian of the children. Her religious dedication was an important early influence on Tolstoy. When she died in 1840, the children were sent to Kazan, Russia, to another sister of their father, Pelageya Yushkov.

Tolstoy was educated at home by German and French tutors. He was not a particularly exceptional student but he was good at games. In 1843 he entered Kazan University. Planning on a diplomatic career, he entered the faculty of Oriental languages. Finding these studies too demanding, he switched two years later to studying law. Tolstoy left the university in 1847 without taking his degree.

Tolstoy returned to Yasnaya Polyana, determined to become a model farmer and a "father" to his serfs (unpaid farmhands). His charity failed because of his foolishness in dealing with the peasants (poor, working class) and because he spent too much time socializing in Tula and Moscow. During this time he first began making amazingly honest diary entries, a practice he maintained until his death. These entries provided much material for his fiction, and in a very real sense the collection is one long autobiography.

Army life and early literary career

From November 1854 to August 1855 Tolstoy served in the battered fortress at Sevastopol in southern Ukraine. He had requested transfer to this area, a sight of one of the bloodiest battles of the Crimean War (1853–1956; when Russia battled England and France over land). As he directed fire from the Fourth Bastion, the hottest area in the conflict for a long while, Tolstoy managed to write Youth, the second part of his autobiographical trilogy. He also wrote the three Sevastopol Tales at this time, revealing the distinctive Tolstoyan vision of war as a place of unparalleled confusion and heroism, a special space where men, viewed from the author's neutral, godlike point of view, were at their best and worst.

When the city fell, Tolstoy was asked to make a study of the artillery action during the final assault and to report with it to the authorities in St. Petersburg, Russia. His reception in the capital was a triumphant success. Because of his name, he was welcomed into the most brilliant society. Because of his stories, he was treated as a celebrity by the cream of literary society.

Golden years

In September 1862, Tolstoy married Sofya Andreyevna Bers (or Behrs), a woman sixteen years younger than himself. Daughter of a prominent Moscow doctor, Bers was beautiful, intelligent, and, as the years would show, strong-willed. The first decade of their marriage brought Tolstoy the greatest happiness; never before or after was his creative life so rich or his personal life so full. In June 1863 his wife had the first of their thirteen children.

The first portion of War and Peace was published in 1865 (in the Russian Messenger ) as "The Year 1805." In 1868 three more chapters appeared, and in 1869 he completed the novel. His new novel created a fantastic out-pouring of popular and critical reaction.