Ascension of Christ; Adoration of the Magi; Presentation of Christ at the Temple

Andrea mantegna (isola di carturo (pd) 1431 - mantua 1506).

- Characteristics

- Description

Today the three panels form part of a triptych inserted in a Renaissance-style frame dating back to the 19th century. This is therefore an arbitrary reconstruction, and the original context must have been very different. The three scenes depict three Gospel stories. The one in the center illustrates, with many figures and details, the homage of the Magi to Baby Jesus, who sits on the lap of the Virgin Mary in the glory of angels and under the watchful gaze of the elderly Joseph. The natural scenery in which the episode is set is replaced in the scene on the right by a sumptuous and majestic architecture: the temple where Mary, according to Jewish custom, went to purify herself forty days after giving birth and where Jesus received the circumcision. The scene depicts Jesus in his mother's arms, retreating in fear before the priest who is about to perform the rite. On the other hand, the scene on the left is part of the stories of post-mortem Christ, and describes the last episode narrated in the Gospel of Luke, namely the ascension to heaven of the risen Christ, in the presence of his mother Mary and the apostles.

The three panels were part of a decorative cycle created by Andrea Mantegna and commissioned by Ludovico Gonzaga (1412-1478) for the chapel of the Saint George Castle in Mantua, which was lost due to subsequent renovations of the building. To the same cycle also belonged the scene of the Death of the Virgin, which is currently divided between Madrid (Prado Museum, inv. no. 248) and Ferrara (National Art Gallery inv. no. 333) and, perhaps, the Resurrection of Christ and Descent into Limbo, divided between Bergamo, Accademia Carrara, and a private collection. However, the reconstruction of the pictorial cycle, as well as its original location and the time of its execution, are still largely debated. The concave shape of the panel with the Adoration of the Magi, which is also wider than the other panels (while originally it must have been of the same height), suggests that the painting was made to fit a curved wall, probably a niche or a small apse in the chapel.

The creation of the pictorial cycle in the chapel of the Saint George Castle coincides with the period in which Andrea Mantegna moved from Padua to Mantua, where he was documented as early as 1460 and where he stayed until his death, thus becoming the favourite painter of the reigning family, the Gonzaga.

The three panels now in the Uffizi became famous in Florence in the collection of Don Antonio de' Medici (1576-1621), which he had inherited from his parents, Grand Duke Francesco I and Bianca Cappello, both died in 1587. It is believed that Francesco received the paintings on the occasion of the wedding of his daughter Eleonora with Vincenzo I Gonzaga in 1584.

Among the greatest interpreters and promoters of the renewal of north Italian painting following a Renaissance style, Andrea Mantegna was skilled in the use of perspective, as it is also revealed by how the sense of depth is given through the chequered floor in the scene of the Presentation at the Temple. The painter showed a keen interest in the culture and art of the ancient Greco-Roman civilization, on which he concentrated almost with the spirit of an archaeologist. He was an extraordinary draughtsman and managed to translate into painting Donatello's sculpture (1386-1466), who was active for a long time in Padua, Mantegna's birthplace.

R. Lightbown, Mantegna, with a complete catalogue of paintings, drawings and prints , Oxford 1986, pp. 411-415;L. Attardi, in Mantegna 1431-1506 , a cura di G. Agosti e D. Thiébaut, Parigi – Milano 2008, pp. pp. 192-193; G. Valagussa, in A ndrea Mantegna. Rivivere l'antico, costruire il moderno , Torino, 2019, p. 236

The Newsletter of the Uffizi Galleries

The meaning of The Presentation of Christ by Andrea Mantegna

"The Presentation of Christ in the Temple" by Andrea Mantegna is a masterpiece that captures a pivotal moment in Christian theology. The painting depicts the presentation of the infant Jesus at the temple, as narrated in the Gospel of Luke. The central figures are Mary, Joseph, the child Jesus, and the elderly Simeon holding the baby in his arms. The composition is structured in a pyramid shape, with the characters arranged to draw the viewers' eyes towards the Christ child. The use of perspective, rich colors, and detailed architectural elements highlight the solemnity and significance of the scene.Mantegna's meticulous attention to detail in "The Presentation of Christ" conveys a sense of reverence and awe. The figures are portrayed with a sense of dignity and grace, capturing the sacredness of the moment. The painting symbolizes the fulfillment of biblical prophecies and the recognition of Jesus as the long-awaited Messiah. The interaction between the characters conveys a profound sense of devotion and faith.However, beneath the surface of this religious narrative lies a hidden interpretation that challenges traditional assumptions. Some art historians and scholars have proposed an alternative reading of the painting, suggesting that Mantegna may have embedded a subtle commentary on the social and political dynamics of his time. By closely examining the expressions and body language of the figures, a different narrative emerges—one that hints at themes of power, authority, and hierarchy.In this reinterpretation, Mary and Joseph represent the marginalized and oppressed, while Simeon symbolizes the established religious and political institutions. The presentation of the Christ child can be seen as a subversive act, challenging the existing power structures and calling for a reevaluation of societal norms. The painting invites viewers to question their assumptions and explore the complexity of interpersonal relationships and societal expectations.By juxtaposing the traditional and unconventional interpretations of "The Presentation of Christ in the Temple," viewers are encouraged to engage with the painting on a deeper level. Mantegna's masterful execution allows for multiple layers of meaning and invites contemplation and discussion. Ultimately, the painting serves as a reminder of the enduring power of art to provoke thought, spark conversation, and inspire new ways of seeing the world around us.

The meaning of Portrait of Cardinal Ludovico Trevisan by Andrea Mantegna

The meaning of the dead christ by andrea mantegna.

Where next?

Explore related content

The Presentation of Christ in the Temple

Pietro antonio magatti c. 1725 - 1730, veneranda biblioteca ambrosiana milano, italy.

This painting, with its very balanced composition and extremely delicate tones, shows the presentation of Jesus in the Temple, just as Simeon takes the Child into his arms. Its formal characteristics show that it must have been painted in the 1720s. Scholars are undecided on whether this is a preparatory study or a work that is small in size to make it suitable for private devotion.

- Title: The Presentation of Christ in the Temple

- Creator: Pietro Antonio Magatti

- Date Created: c. 1725 - 1730

- Physical Dimensions: 72 x 93 cm

- Type: Painting

- Medium: Oil

- Art Genre: Sacred art

- Art Form: Painting

- Support: Canvas

- Depicted Topic: madonna, Christ child, high priest

Get the app

Explore museums and play with Art Transfer, Pocket Galleries, Art Selfie, and more

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Brothers in art: the Renaissance rivalry of Mantegna and Bellini

With paintings so similar their origins have been disputed for centuries, these giants of Italian art are now being exhibited together for the first time at London’s National Gallery

I n a small room in a former palace in Venice there is a strange, compelling painting set on an easel at head height so the viewer looks straight into eyes first depicted more than 500 years ago. It is very like an earlier painting now in Berlin and art historians have been arguing about them both for years.

Both paintings ostensibly show the infant Jesus in the temple. The one at the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, is agreed to be the work of Andrea Mantegna . The Venetian painting, made 20 years later, was credited to Mantegna also. But it is now accepted as by Giovanni Bellini .

There is something unnerving about seeing it so close up on its easel; the black background, the heads packed together, the baby as tightly swaddled as a chrysalis – apart from his poor little fingertips.

Recently, an experiment was carried out in the former palace in Venice – a heart-stopping moment for Caroline Campbell. She is the curator of an exhibition at the National Gallery in London that will bring the two paintings together again in the first show to directly compare the work of both men. (The origins of the exhibition lie in the years she has spent puzzling over two more related works – Mantegna and Bellini’s versions of The Agony in the Garden , which have hung together in London since the 19th century.)

A tracing of the Berlin Jesus painting on an acetate sheet was overlaid on to the Venice version. The six central figures matched exactly. “Anyone with eyes could see that there was a relationship between the two artists,” said Campbell, “but this was the first solid evidence of one man working directly from the other.”

The relationship between the two men was well known. They were both giants of 15th-century Italian art: one, the stroppy son of a carpenter from a tiny village outside Padua; the other, a mild-mannered Venetian born into the city’s most acclaimed family of artists.

Bellini’s precise birth and death dates, where he lived and the exact site of his grave are not known, though he lived to the great age of 86 and died in Venice, rich and revered. A prodigy apprenticed as a child to a Paduan artist, Mantegna is less elusive because he was an argumentative soul and his life can be tracked in legal actions. He went to court to escape adoption by the master who trained him but wouldn’t pay him; against a wealthy patron who felt he’d cheated her on the number of angels in her altar piece; or, when he thought a studio assistant was stealing his ideas.

Furthermore, Mantegna married Bellini’s sister Nicolosia – a beauty, if she was, as is presumed, the model for the Virgin. The match was probably made by her father Jacopo to bring the brilliant young man, already more famous than either of Jacopo’s artist sons Giovanni and Gentile, into his workshop without having to pay him. Although the two families remained in contact, Jacopo lost his prize when Mantegna accepted an invitation to become court painter to the Dukes of Mantua.

While the Bellinis prospered in Venice, in later years Mantegna’s extravagant lifestyle, and problems with actually getting paid his princely salary, meant that he died in poverty near the church where he is buried, long after the sale of the extraordinary house he designed and built. It is still standing, although now a shell in use as a contemporary art gallery.

His Jesus in the Temple painting may have been made to mark his marriage to Nicolosia and the hope of a child. Campbell believes that Bellini may have recreated it, incorporating more family portraits to mark the death of his father, Jacopo.

The exhibition studies the relationship between their work and the extent to which they inspired, borrowed from, or even directly imitated one another. Campbell attributes to Mantegna the dramatic black backgrounds, which bring out the sculptural qualities of the figures in many of the smaller works; the audacious experiments in perspective and foreshortening; and his fascination with the architecture of classical Rome and Greece. (Roman fragments burst through the soil of Padua at every street corner.) She gives Bellini the prize for suffusing his paintings with light and for creating emotional warmth even when he was borrowing the figures from his brother-in-law or his father’s notebooks.

As to which was the greater, visitors will be joining an argument now more than five centuries old. The 16th-century biographer Giorgio Vasari called Mantegna “praiseworthy in all his actions”, and predicted “his memory will ever live not only in his own country but in the whole world”.

In 1504, a Venetian art dealer wrote to Isabella d’Este, patron of both artists: “Nobody can beat Mr Andrea Mantegna for invention in which he is the height of excellence … but in colour Giovanni Bellini is excellent.” Albrecht Dürer , a jealous assessor of the genius of other artists, wrote of Bellini, who was then working aged about 90, “still he is the best painter of them all”.

Campbell keeps her counsel on the ancient debate, but there may be a clue in her intake of breath on a recent visit to the wondrous Bellini altarpiece in the Frari in Venice – the honeyed light in which the figures stand magnified by the golden rays of an autumn afternoon pouring in, as Bellini intended, from a tall window in the side wall. It is one of the masterpieces she never contemplated borrowing for the exhibition. “I don’t think this picture has ever left this space – and I hope it never will. It is just perfection.

“To admire one is not to take from the other,” Campbell says firmly. “Mantegna for invention, Bellini for light, both are wonderful.”

- National Gallery

- Christianity

- Exhibitions

Most viewed

Apollo Magazine

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

Lost your password?

← Go to Apollo Magazine

Category : Presentation of Christ in the Temple by Andrea Mantegna

Subcategories.

This category has only the following subcategory.

- Presentation of Christ in the Temple by Andrea Mantegna - Details (5 F)

Media in category "Presentation of Christ in the Temple by Andrea Mantegna"

The following 11 files are in this category, out of 11 total.

- Paintings by Andrea Mantegna in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

- Paintings in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin by title

- Religious paintings in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

- Paintings in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin - Room 38

- Paintings of the presentation of Jesus Christ at the Temple in Germany

- Renaissance religious paintings

- Self-portraits with family

- Swaddling in paintings (infant Jesus)

- 15th-century oil on canvas paintings in Germany

- 15th-century religious paintings in Germany

- 1460s religious paintings from Italy

- 1460s paintings in Germany

- Madonnas by Andrea Mantegna

- Paintings by Andrea Mantegna by title

- 15th-century paintings of the presentation of Jesus Christ at the Temple

- 15th-century religious paintings by title

- Mantegna and Bellini

- Framed religious paintings

- Renaissance paintings of New Testament figures

- Self-portraits in group

- Uses of Wikidata Infobox

- Individual painting categories

Navigation menu

Go back to the home page

Luke 2:22–33

The presentation of jesus in the temple.

Commentaries by Roger Ferlo

Works of art by Andrea Mantegna , Duccio and Giovanni Bellini

Andrea Mantegna

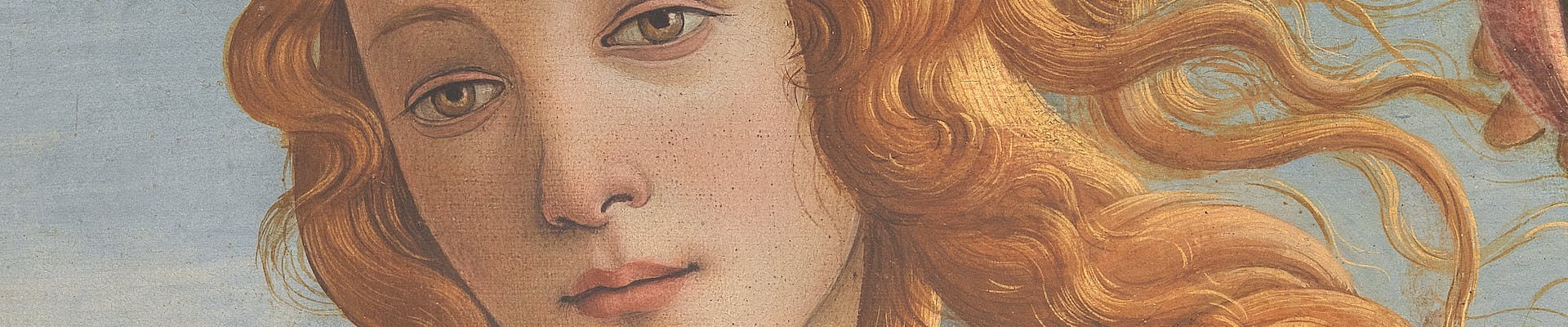

The Presentation in the Temple , c.1455, Tempera on canvas, 77 x 94 cm, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin; 29, bpk Bildagentur / Gemaeldegalerie, Berlin / Photo: Christoph Schmidt / Art Resource, NY

Swaddled or Shrouded?

Commentary by Roger Ferlo

This painting by Andrea Mantegna was probably commissioned to adorn not a church or chapel but a domestic interior. One views the figures in the Presentation story as if through a window. There is a Byzantine stillness here. Mantegna was known for the chiselled quality of his painted figures, often depicted in foreshortened perspective—a kind of sculpture in two dimensions rather than three. The striking verticality of the stiffly swaddled infant directly parallels the equally striking verticality of Simeon’s profile and lengthy beard. Grouped around these two verticals, the remaining figures create two overlapping and geometrically perfect ‘golden sections’—a compositional tour de force underscoring the harmony and joy expressed in Simeon’s song (Blass-Simmen 2018: 42).

The Virgin’s forearm gently protrudes towards the viewer’s side of the virtual window, as do the pillow on which the swaddled child rests, and Simeon’s outstretched left hand. By breaking through the picture plane the artist gives us the impression that his figures share the same space as us. He makes the viewer a direct witness to the action. And the viewer is not alone. Most scholars agree that on the right Mantegna has included his own self-portrait, and on the left, a portrait of Nicolosa Bellini, his new bride. This painting may be intended as a joyful celebration of the birth of Andrea and Nicolosa’s first child, to which the viewer is an invited guest (Rowley 2018: 58–59).

But amidst the painting’s muted colours and strong geometrical structure, this joy seems shadowed by impending loss. The mood is solemn, the emotions inscrutable. Perhaps this is why Nicolosia looks away from the action. The swaddled infant looks away as well, a troubled expression on its face. Those swaddling clothes, so tightly wound, double as a shroud—a hint of this child’s destiny, a harbinger of the cross and tomb. It’s as if Nicolosia knew.

Blass-Simmen, Brigit. 2018. ‘One Cartoon—Two Paintings’, in Bellini/Mantegna: Masterpieces Face-to-Face — The Presentation in the Temple , ed. by Dario Cimarelli (Milan: Silvani Editoriale), pp. 35-49

Rowley, Neville. 2018. ‘Critical Fortunes and Worldly Vicissitudes in Andrea Mantegna’s Presentation of Jesus at the Temple, Now at the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin’, in Bellini/Mantegna: Masterpieces Face-to-Face—The Presentation in the Temple , ed. by Dario Cimarelli (Milan: Silvani Editoriale), pp. 51–61

Presentation in the Temple (from the Maestà) , 1308–11, Tempera and gold on panel, 44 x 45 cm, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Siena; Scala / Art Resource, NY

An Explosion of Colour and Light

In 1311 a huge altarpiece was commissioned from the local Sienese artist, Duccio di Buoninsegna, to adorn the high altar of Siena’s great cathedral. Originally located beneath the dome in the crossing, Duccio’s monumental double-sided polyptych, exceptional in the number and the variety of its panels, and rising perhaps twenty feet above the nave (Conrad 2016: 184), must have stood out dramatically against the black and white marble that still dominates much of the cathedral interior. It would have been an explosion of colour and light.

The entire front of the predella—the horizontal box-like support to the main tier of the altarpiece—was painted with episodes in Jesus’s birth and early childhood, and this exquisite depiction of Luke’s Presentation story occupied the predella’s central position. In the large panel directly above it, the artist installed an immense representation of the Virgin Mary enthroned in glory and surrounded by a vast cloud of witnesses—the famous Maestà —hovering still and glowing like a massive Byzantine icon.

Small as it is in contrast with the massive Maestà , the Presentation panel at the centre of the predella was not placed there by accident. In contrast with the imperial image soaring above it, the scale and mood of this painting is intimate, personal. A frightened child reaches back to his mother, her hands still outstretched as if ready to take him back. Behind them stands an altar under a marble baldachin, the stonework of its Romanesque arch painted in alternating colours. The pattern recalls the decoration of Siena cathedral itself, but a joyful red has transformed the official Sienese black and white.

Between the monumental and the intimate, the hieratic and the emotive, these contrasts echo the theological doubleness at the heart of Luke’s account, balancing the joy of Simeon’s song of deliverance (‘For my eyes have seen your salvation’) with the dark warning pronounced just a few verses later. ‘This child is destined for the rising and falling of many’, Simeon will say to Mary, ‘and a sword will pierce your own soul too’ ( Luke 2:34–35 ). No wonder the child—‘a sign that will be opposed’—seeks the arms of his mother, against the sobering backdrop of that glowing altar of sacrifice (Luke 2:33, 35).

Conrad, Jessamyn. 2016. ‘The Meanings of Duccio’s Maestà: Architecture, Painting, Politics, and the Construction of Narrative Time in the Trecento Altarpieces for Siena Cathedral’, PhD Dissertation, Columbia University

Giovanni Bellini

The Presentation in the Temple , c.1460, Tempera on panel, 80 x 105 cm, Fondazione Querini Stampalia, Venice; Cameraphoto Arte, Venice / Art Resource, NY

A Family Business

The Venetian Renaissance painter Giovanni Bellini was Andrea Mantegna’s brother-in-law. This work, painted on panel, at first glance looks like an exact copy of Mantegna’s painting of the Presentation ( also in this exhibition ). Perhaps Bellini admired the painting so much that he sought to learn from it by copying it. There is evidence that he traced the outline of the images directly from the original (Blass-Simmen 2018: 36). But Bellini’s homage to his brother-in-law is also an act of artistic independence—a loosening of the original’s mood and structure. Perhaps we may see in this more a response to the joy of Luke’s narrative than to its shadowed forebodings.

Bellini’s version is wider, more spacious than Mantegna’s. He eliminates Mantegna’s window effect; instead, he places his principal figures behind a simulated marble parapet, stretching across the entire panel. Where Mantegna was a master of line and proportion, Bellini is a master of colour. His colours, though now sadly faded, were originally more vibrant. His lines are more relaxed. There is more room to breathe. Mary’s features are softer, Simeon’s less rigid. Even though the viewer is kept at a distance by that marble parapet, Bellini brings the central encounter right up to the picture plane. Mary’s forearm, the corner of the cushion, and Simeon’s welcoming hands come close to the viewer’s side of the parapet.

Bellini’s version seems less and less icon-like, and more like an incident in progress. He preserves the image of his half-sister Nicolosia looking away from the action, but he adds two additional figures, one on each side of the painting. They closely watch the action at the centre, as if to counter Nicolosia’s anxiety. Bellini preserves the infant’s shroud-like swaddling, but Mary seems more willing to let the child go. She has slightly relaxed her embrace, as if now reconciled to her child’s fate. Once that child has been loosed from his swaddling shroud—like Lazarus risen from the tomb—she too will rejoice with Simeon in this resurrection light.

Andrea Mantegna :

The Presentation in the Temple , c.1455 , Tempera on canvas

Presentation in the Temple (from the Maestà) , 1308–11 , Tempera and gold on panel

Giovanni Bellini :

The Presentation in the Temple , c.1460 , Tempera on panel

An Act of Holy Ventriloquism

Comparative commentary by Roger Ferlo

Luke punctuates his nativity story with several stirring set pieces: the song of Mary when she visits her cousin Elizabeth ( Luke 1:46–55 ); the prophecy of Zechariah, miraculously healed of his inability to speak as he celebrates the birth of his son John the Baptizer (Luke 1:68–79); the song of the angels to the shepherds ( Luke 2:14 ); and the prayer of Simeon (Luke 2:29–32). At such moments, the narrative action draws to a temporary halt. These songs in Luke operate much like a Byzantine icon: an image that distils the ‘and then’, ‘and then’ of the biblical narrative into a timeless moment. The viewer contemplates the divine glory as if through a cosmic window. Time becomes timeless, action is suspended. In the icon, meaning is distilled into line and colour; in Luke’s Gospel, into poetic form and an implied melody.

No wonder Lukan passages like Simeon’s song (traditionally known as the Nunc Dimittis , the Latin text of the opening words) has become so prominent in the history of Christian ritual. When the Nunc Dimittis is sung liturgically, both singers and listeners are witnesses to the scene (like viewers before the icon) and, in an act of holy ventriloquism, virtual participants in the action, taking the part of Mary or Simeon.

One might compare this Lukan alternation of movement and stillness to the alternation between narrative and lyric in a Bach passion. At one moment, the chorus acts the role of the crowd gathered before Pilate (‘Crucify him, Crucify him’, they sing), but then, minutes later, without warning they break into a four-part Lutheran chorale (perhaps originally joined by the Leipzig congregation), reflecting on the emotional impact of the scriptural story in their own lives. Even today, when worshippers sing or hear Simeon’s prayer of joy during an evening service or at a service of burial (and perhaps recall the words of foreboding that follow in vv.33–35 ), they are thrust (or thrust themselves) into the biblical moment, sharing in—even re-enacting—Simeon’s act of confession and conversion: ‘Now you are dismissing your servant in peace … for my eyes have seen your salvation’.

So imagine what it was like to encounter the dazzling colour and gold leaf of Duccio’s immense altarpiece, glowing aloft against the black and white stonework and the cathedral’s shadowy recesses, like a light to enlighten the nations (see Luke 2:32). You are at once stunned, even intimidated, by the timeless icon-like image of the Virgin and Child in majesty. But then, if you are one of those permitted to draw closer, you realize you are also made privy to the intimate scene of the Presentation, depicted just below. You take in the imploring gesture, so tender and natural, of the Christ child seeking to return to his mother’s arms, the child who is nonetheless the hope of his people Israel. And then, at the rear of the scene, the golden light in the archway invites you to enter into the mystery of the Incarnation, the divine become human, in the eucharistic rite celebrated day by day at the altar below.

On the other hand, to approach Andrea Mantegna’s or Giovanni Bellini’s paintings, displayed as they are today in art galleries framed on a wall or perched on a free-standing easel, is to enter a different kind of space—a space at once more personal (you can be alone with the image), and more intimate (you are at eye-level). Although you are nowhere near a church, standing before each of these works you sense you have been invited into the Temple ritual, the way Luke’s gospel for centuries has moved the reader or hearer of his story to recite Simeon’s words aloud in unison with the prophet. You are present both as a foreign observer, watching through a virtual window or across the barrier of a virtual marble parapet, and yet also as a participating witness in a family event, joining with Mantegna and Nicolosia, and with Bellini’s theatrical extras. (It’s thought that the hovering face of Joseph, central in both paintings, is a portrait of Giovanni’s father Jacopo, Andrea’s father in-law, for whom the painting might originally have been intended; Blass-Simmen 2018: 36).

The brother-in-law artists invite us to enter fully into the scene, empowering us to acknowledge—along with Simeon—that this child, now bound and swaddled, will abandon that shroud in the empty tomb, and that our eyes, too, will have seen our salvation.

Revised Standard Version

22 And when the time came for their purification according to the law of Moses, they brought him up to Jerusalem to present him to the Lord 23 (as it is written in the law of the Lord, “Every male that opens the womb shall be called holy to the Lord”) 24 and to offer a sacrifice according to what is said in the law of the Lord, “a pair of turtledoves, or two young pigeons.” 25 Now there was a man in Jerusalem, whose name was Simeon, and this man was righteous and devout, looking for the consolation of Israel, and the Holy Spirit was upon him. 26 And it had been revealed to him by the Holy Spirit that he should not see death before he had seen the Lord’s Christ. 27 And inspired by the Spirit he came into the temple; and when the parents brought in the child Jesus, to do for him according to the custom of the law, 28 he took him up in his arms and blessed God and said,

29 “Lord, now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace,

according to thy word;

30 for mine eyes have seen thy salvation

31 which thou hast prepared in the presence of all peoples,

32 a light for revelation to the Gentiles,

and for glory to thy people Israel.”

33 And his father and his mother marveled at what was said about him;

More Exhibitions

Sign up for our free newsletter

Master of the Life of the Virgin, The Presentation in the Temple

The priest Simeon is shown receiving the infant Christ from the Virgin Mary in front of an elaborate altar. The scene is based on a passage in the Gospel of Luke (2:22–40), which describes Mary and Joseph’s visit to the temple in Jerusalem for the rituals of Mary’s purification and of Christ’s presentation to God.

Simeon recognised Christ’s divinity upon seeing him, saying ‘Lord, now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace, according to thy word: For mine eyes have seen thy salvation’ (Luke 2: 29–30). The embroidery on his cope shows the Roman Emperor Augustus having a vision of the Virgin and Child – a decisive experience which made the ruler recognise that their spiritual power was greater than his.

This painting, along with seven other panels now in the Alte Pinakothek, Munich, once formed part of the central panel of an altarpiece made for the church of Saint Ursula in Cologne. It was commissioned by Dr Johann von Hirtz, a councillor in the city.

This scene is based on a passage in the Gospel of Luke (2:22-40), which describes Mary and Joseph’s visit to the temple in Jerusalem for the rituals of Mary’s purification and of the infant Christ’s presentation to God. In conformity with Jewish law, all women had to be ritually purified forty days after giving birth, while first-born sons were to be presented and redeemed by an offering to God. The priest, Simeon, is shown receiving the infant from Mary in front of an elaborate altar. The two turtle doves held by a woman at the left were brought as the sacrificial offering to secure Christ’s redemption.

Simeon was the first to recognise Christ’s divinity after the latter’s birth. Upon seeing the child, the priest said: ‘Lord, now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace, according to thy word: For mine eyes have seen thy salvation’ (Luke 2: 29–30). The Old Testament scenes visible on the carved stone altarpiece and on the back of Simeon’s embroidered cope underscore the theological significance of the event, as they were deemed to foreshadow Christ’s Passion. The altarpiece shows Cain slaying his brother Abel, the sacrifice of Isaac, and the drunkenness of Noah, while the embroidery of Simeon’s cope depicts the Roman Emperor Augustus’s vision of the Virgin and Child during which he – a pagan – recognised that their spiritual power was greater than his. The small boys cast in bronze who hold up the altar may be references to pagan art, and reinforce the message of the cope by illustrating that paganism was surpassed by Judaism and Christianity.

The painting once formed part of an altarpiece made for the church of Saint Ursula in Cologne, consisting of scenes of the life of the Virgin Mary. Seven other panels are today in the collection of the Alte Pinakothek in Munich. The work was commissioned by Johann von Hirtz, an alderman and mayor of the city.

The centre panel of the altarpiece consisted of four scenes arranged in a square grid – The Presentation in the Temple appeared in the lower right. It was once thought that the altarpiece took the form of a triptych (a painting composed of three parts) but recent technical analysis has raised the possibility that the panels may have been shown individually or in a different formation to that of a triptych.

Download a low-resolution copy of this image for personal use.

License and download a high-resolution image for reproductions up to A3 size from the National Gallery Picture Library.

This image is licensed for non-commercial use under a Creative Commons agreement .

Examples of non-commercial use are:

- Research, private study, or for internal circulation within an educational organisation (such as a school, college or university)

- Non-profit publications, personal websites, blogs, and social media

The image file is 800 pixels on the longest side.

As a charity, we depend upon the generosity of individuals to ensure the collection continues to engage and inspire. Help keep us free by making a donation today.

You must agree to the Creative Commons terms and conditions to download this image.

More paintings by Master of the Life of the Virgin

Preaching Grace on the Square

Scripture, tradition, theology, random thoughts from capitol square in madison, wi.

The Presentation of Our Lord Jesus Christ in the Temple: A sermon

Presentation of Jesus at the Temple (detail), Andrea Mantegna, c. 1455

Today is the Feast of the Presentation of our Lord Jesus Christ in the Temple. It’s a major feast in our calendar but one we observe at Grace only when it falls on a Sunday. It commemorates the events recorded by Luke in today’s gospel reading. Jesus’ parents Mary and Joseph brought him to the temple forty days after his birth to conform to Jewish ritual obligations—the presentation of the first-born to God; and the purification of a woman after giving birth.

It’s a bit disorienting to read this gospel today, to commemorate the Feast of the Presentation, because it draws our attention backwards, to Christmas. In a very real sense, it is the final observance of the Christmas season, which explains why in many traditional Christian churches, the Christmas decorations, especially the creche remain until this day. Our attention is drawn back to Christmas, to the birth of Christ, and to his family. And even as our lives have moved on, and the world is not paying attention, the church allows us one last glimpse of the joy of Christmas.

It is a story full of joy—the joy of parents who are faithfully fulfilling the practices of their faith—and especially the joy of two elderly people who see the identity of the baby and testify to his world-historical significance.

Luke is keen to show Jesus’ parents obeying Jewish law, mentioning it no fewer than five times in this brief passage. He is also concerned to show them as observant Jews. He will do the same when he depicts Jesus. In addition, the temple is a focal point. Joseph and Mary bring Jesus here twice, now forty days after his birth. They will bring him again when he is twelve years old, an incident related only by Luke in the very next verses. Jesus will remain behind at the temple after his parents leave; when they discover he is not with the group returning to Nazareth, they return to the temple and find him in conversation with religious leaders about scripture.

Jesus will return to the temple when he comes to Jerusalem just before his crucifixion and the temple will continue to be a focal point for his disciples after his ascension. In fact, Luke’s description of them at the end of the gospel, calls to mind his description of Anna, “They returned to Jerusalem with great joy, and they were continually in the temple blessing God.” (24:53)

In addition to the prominent role of the temple throughout Luke and Acts, this story emphasizes other themes central to Luke’s telling. The presence of Simeon and Anna, two aged people who testify to the baby’s identity link this story to models in Hebrew scripture and also appeal to the prophetic tradition. Anna is explicitly identified as a prophetess while Simeon offers prophecy as well as song when he encounters Jesus.

Simeon’s is not the first song Luke records in the gospel. The nativity story is accompanied by hymns: that of Zechariah, “Blessed be the Lord God of Israel, for he hath visited and redeemed his people.” He sang it when his voice returned after the birth of his son John the Baptist. There’s Mary’s song, the Magnificat, “My soul proclaims the greatness of the Lord.” There’s the song the angels sang, “Glory to God in the highest and peace to his people on earth.” And there is this one, “Lord, now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace.” These are the church’s songs, sung for nearly two thousand years and sung or chanted during the daily office.

While emphasizing tradition, the law and the prophets, and these two elderly witnesses, Luke also emphasizes the role of the Holy Spirit, mentioning her movement three times in describing Simeon. Simeon was righteous and devout and looking forward to the consolation of Israel. His song is one of benediction and leave-taking. But Simeon has more to say and turns to ominous prophecy: “this child is destined for the rising and the falling of many in Israel … and a sword will pierce your own soul, too.” Unfortunately, Luke doesn’t tell us what Anna said instead only leaves us with the image of an elderly woman who spent all of her time in the temple speaking about Jesus to everyone in the temple “who were looking for the redemption of Jerusalem.”

On the surface this episode that brings to an end Luke’s infancy narrative is little more than confirmation of what has gone before—the birth of the Son of God in keeping with scripture and witnessed by people who were able to testify to its importance. But when you step back a moment to reflect, it opens up great depths of meaning.

Think again about the temple’s significance. It plays an important role in this episode as it does throughout Luke and Acts. Yet by the time Luke was writing, the temple lay in ruins. In fact, it may have been destroyed two generations before he wrote. So, Luke’s readers could not have imagined the scene. They had no reference points for it.

And think about those two elderly people who express their joy, of Simeon who sings “my eyes have seen my salvation.” But the sort of hopes expressed in this text, the consolation of Israel, the redemption of Jerusalem had not been accomplished and may have seemed further away than ever before. Would Simeon and Anna been able to hold on to their hope if they knew what the future held?

And even in this story of faith, hope, and joy, there is an ominous note. In his blessing, Simeon speaks of the falling and rising of many in Israel, of opposition and division, and most of all, of a sword that will pierce Mary’s soul. Even here in the joy of incarnation, the shadow of the cross looms. Perhaps that’s why Mantegna, in the painting reproduced on the service bulletin’s cover, seems to have Jesus wrapped, not in swaddling clothes but in what looks like burial wrappings.

We hear this story today, forty days after Christmas, when the joy of that season has long since left us, cooled by endless gray days, by the relentless cycle of news that wears us down and grinds our hope into despair. We hear this story when our attention is fleeting perhaps diverted momentarily by national spectacle like the Super Bowl or the silly rituals of Groundhog Day.

Can we appreciate the power of the story that Luke has crafted, a story of long waits, expectation and hope in the midst of disappointment? Can we see ourselves in the aged Simeon and Anna, whose faith did not falter through years of struggle and disappointment?

This is the Feast of the Presentation. Mary and Joseph brought Jesus to the temple. Our cover image shows Mary doing just that. But it also shows Simeon’s outstretched hands. While our translations says that Simeon “took” the baby, a better translation would be that “he received him. Indeed, Simeon didn’t just see Christ, as my friend Chris Bryan has written,

he touches him, holds him, embraces him؛†and given that Jesus comes to Simeon in the weakness of babyhood, for this moment Simeon actually carries him, as the stronger carries the weaker. Simeon has waited faithfully upon God, and the reward of his faithfulness is that for just a moment he becomes the hearer of Christ.

Mary and Joseph presented Christ in the temple; they presented him to Simeon and Anna. Yet Simeon’s and Anna’s confessions make clear who Jesus is: our salvation, our redemption, the Son of God. The collect for the day reminds us that Christ presents us to God, and in a real sense that is what was happening here; Jesus was presenting his parents to God, to Simeon and Anna.

We make Christ present on this altar, recalling his life, death, and resurrection. But the fact of the matter is that in a deeper sense, Christ is presenting us. We approach his table hand in hand with him, carried by him.

May we, like Simeon and Anna, proclaim our faith in Christ, may we see him here, on the altar, in our lives and in the world around us. May we sing with Simeon:

For mine eyes have seen thy salvation, which thou hast prepared before the face of all people,

To be a light to lighten the Gentiles, and to be the glory of thy people Israel.

Share this:

Leave a comment cancel reply.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Presentation of Jesus at the Temple

- Fra Angelico

* As an Amazon Associate, and partner with Google Adsense and Ezoic, I earn from qualifying purchases.

Fra Angelico was one of the most important artists of the Early Renaissance in Florence. Born Guido di Pietro, his first paintings are noted in 1417, and it is around the same time that he became a novice at the Friary of San Domenico at Fiesole near Florence, taking the name of Fra Giovanni.

He remained there until 1439, when he moved to the city's Dominican Friary of San Marco, which was rebuilt with the support of Cosimo de Medici. Presentation of Jesus at the Temple is one of a series of frescoes completed here around 1440 to 1442. Fra Angelico worked on these, arguably his best-known works, with his assistants, choosing detailed subjects for the public areas, but reserving more restrained representations for the cells where the monks contemplated.

The muted colours of Presentation of Jesus at the Temple was produced for Cell 10, dominating in a way that is not intrusive to quiet thought and meditation. Fra Angelico was influenced by other artists of the Early Renaissance in Florence, especially the sculptor Ghiberti, and experimented with realism and volume to define subjects, and used linear perspective to emphasise space in the more thoughtful pictures.

The story is taken from St Luke's Gospel, when Mary and Joseph take the baby Jesus to the temple, as required for a first-born son. Joseph carries two turtle doves in a basket as an offering, with flames in the altar to emphasise the custom. The devout ageing Simeon receives the vision of the Messiah promised to him by God, as he holds the infant. Also in the picture are Saint Peter Martyr and Blessed Villana, a Florentine holy woman of the fourteenth century. The group conveys the serenity that is common in Fra Angelico's art, allowing him to portray ordinary people with dignity and respect.

The artist probably first worked under the monk Lorenzo Monaco, an important Florentine manuscript illuminator, miniaturist and painter at the time, with Fra Angelico's touches discernible in a choir book and elsewhere. After his death in Rome in 1455, he was described as the Angelic Painter due to the tranquillity of his style, and the name of Fra Angelico stuck. Although he has continued to be appreciated, it is only in recent years that his place in the development of European art has been properly recognised. Like Masaccio and others, Fra Angelico grasped the opportunities that came with the era, to pursue his radical understanding of perspective, and was always concerned with new trends. Presentation of Jesus at the Temple, which today still rests in San Marco, now the Museum of San Marco, is a perfect example of this.

Article Author

Tom Gurney in an art history expert. He received a BSc (Hons) degree from Salford University, UK, and has also studied famous artists and art movements for over 20 years. Tom has also published a number of books related to art history and continues to contribute to a number of different art websites. You can read more on Tom Gurney here.

Proposed LDS temple project moves forward after crowds launch fierce debate on both sides

LAS VEGAS, Nev. (FOX5) - Crowds showed up to support a plan for a new temple for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as neighbors continue their fierce opposition to the proposal.

The Las Vegas Planning Commission approved the Site Development Review in a vote of 6 with one abstention, adding conditions to address one aspect of residents’ concerns: before the church moves into the temple, the building must meet lighting standards for the neighborhood and must turn off parking lot lights overnight.

The project moves forward to a full City Council vote on July 17.

Hundreds of church members wore blue shirts and “vote yes” stickers, crowding the steps of Las Vegas City Hall. They also launched a counter-petition drawing close to 10,000 signatures. Church members voiced a need for a second temple on the other side of town; the only temple for 85,000 people lies at the edge of Sunrise Mountain on the far east side.

In late 2022, church leaders announced plans for a second temple at the 20-acre site off North Grand Canyon Road. City documents stated the height of the steeple would be 216 feet. The temple would be 70,000 square feet and a meeting hall would be 15,000 square feet. Parking would be required to accommodate visitors.

“I know I’m looking forward to it. I live super close to it and I know it would benefit me greatly,” said church member Emma Brummett, who said family members also came to show support. “We can drive a lot quicker and be there more often,” she said.

In March, the City Council of Las Vegas voted to amend longstanding code in the district, paving the way for houses of worship to apply for a Special Use Permit to build in the area.

Concerned Neighbors launched a fierce opposition, created a petition with more than 5,000 signatures and launched a Preserve Rural Las V egas website. Various neighbors have expressed concerns over traffic and the massive footprint, but many take issue with the height and lighting proposals in a rural area.

Long-time rural zoning restrictions for the Lone Mountain area limit projects with massive footprints and height and lighting restrictions.

“It’s too big and just doesn’t fit into the area,” said concerned neighbor Matt Hackley. “This isn’t an anti-church movement at all. This is simply a grassroots movement of our neighborhood to protect its rural status,” Hackley said.

Neighbors said they had asked for compromises on concerns but church representatives and project officials seemed unwilling to make major amendments.

“The arrogance and unwillingness to compromise in the name of the Lord I feel is unacceptable,” another concerned resident said.

Residents likened the size and bright lights of various temples to “casinos” in a neighborhood.

Numerous residents own and ride horses, and voiced concerns about the safety to continue to do so. Community members are also lobbying Clark County leaders as the project progresses through city and county commissions.

A spokesperson for the project before the planning commission said the temple site is not a place for carnivals or large events. Several weeks ago, FOX5 spoke to church leadership about neighbors’ concerns. FOX5 was told that officials would address concerns— but some designs are intrinsic to their faith.

“Temples are so special, they are so significant. We build them, and then we dedicate them to God, they are literally a house of the Lord. Things like the size and the height of the building are part of the deep religious meaning and symbolism of the building itself,” said Bud Stoddard, stake president of the Lone Mountain Stake, who spoke to FOX5 several weeks ago.

The City of Las Vegas said the proposed temple will now head to City Council for another full presentation, and then a vote on the project. City documents state as soon as the project is approved, it could be built in 36 months.

Copyright 2024 KVVU. All rights reserved.

Mirage Hotel & Casino closing date announced ahead of Hard Rock hotel

Why will high-speed train from Vegas go to Rancho Cucamonga, CA instead of Los Angeles?

Man shot, killed during drug deal in east Las Vegas neighborhood

Man wins nearly $2 million jackpot at north Las Vegas Strip resort

Mail truck crashes into wall in south Las Vegas neighborhood

Latest news.

FOX5 Vegas Presents the Take 5 to Care Book Stop, featuring the CCSD Book Bus

Death Valley visitor comes forward after pulling down salt tram tower

Las Vegas middle schoolers compete in underwater robotics competition

Skateboarder critically injured by pick-up truck in northwest Las Vegas Valley crash

Man charged with shooting Las Vegas middle school campus monitor pleads guilty

COMMENTS

c. 1455. Medium. Tempera on canvas. Dimensions. 68.9 cm × 86.3 cm (27.1 in × 34.0 in) Location. Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. The Presentation at the Temple is a painting by the Italian Renaissance artist Andrea Mantegna. Dating to c. 1455, it is housed in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin, Germany.

Presentation at the Temple is an example of Andrea Mantegna's early work, from his time in Padua. The exact date of the early Renaissance painting is unknown, but estimates vary from 1453 to 1460. During this time, Mantegna allied himself through marriage to the artist Giovanni Bellini, who subsequently produced a very similar painting also ...

Ascension of Christ; Adoration of the Magi; Presentation of Christ at the Temple. Andrea Mantegna (Isola di Carturo (PD) 1431 - Mantua 1506) Today the three panels form part of a triptych inserted in a Renaissance-style frame dating back to the 19th century. This is therefore an arbitrary reconstruction, and the original context must have been ...

Presentation in the Temple. c. 1460. Tempera on wood, 67 x 86 cm. Staatliche Museen, Berlin. In 1453 or 1454 Mantegna married Nicolosia Bellini and in so doing allies himself professionally with her brother, Giovanni, to whom he imparts Donatellian ideas. The two London panels depicting the Agony in the Garden by Mantegna and Bellini ...

Feb 18. Written By. "The Presentation of Christ in the Temple" by Andrea Mantegna is a masterpiece that captures a pivotal moment in Christian theology. The painting depicts the presentation of the infant Jesus at the temple, as narrated in the Gospel of Luke. The central figures are Mary, Joseph, the child Jesus, and the elderly Simeon holding ...

February 1st 2020. "The Presentation of Christ in the Temple", Andrea Mantegna, c.1454, Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche, Museen su Berlin. It is accepted that this painting dates from around the time of Mantegna's marriage to Nicolosia Bellini and before he left Padua. The two figures, left and right, are thought to be Mantegna and his bride.

Milano, Italy. This painting, with its very balanced composition and extremely delicate tones, shows the presentation of Jesus in the Temple, just as Simeon takes the Child into his arms. Its formal characteristics show that it must have been painted in the 1720s. Scholars are undecided on whether this is a preparatory study or a work that is ...

Bellini's Presentation of Christ in the Temple, a clear imitation of Mantegna's earlier work Photograph: Fondazione Querini Stampalia. The relationship between the two men was well known.

Mantegna's Presentation of Christ at the Temple - which features a self-portrait on the far right - dates from this early period of close proximity to his brother-in-law. The Presentation of Christ in the Temple (1470-75), Giovanni Bellini.

The Presentation at the Temple by the Italian master Giovanni Bellini, dating to c. 1460, is housed in the Fondazione Querini Stampalia, in Venice. The dating of the work is uncertain, though it is usually considered to be subsequent to the Presentation at the Temple by Andrea Mantegna (Berlin, c. 1455), from which Bellini took a very similar placement of the figures.

Media in category "Presentation of Christ in the Temple by Andrea Mantegna". The following 13 files are in this category, out of 13 total. Andrea Mantegna - The Presentation - Google Art Project.jpg 5,061 × 4,000; 11.29 MB. Andrea Mantegna - Presentation in the Temple - WGA13963.jpg 1,300 × 1,027; 173 KB.

Andrea Mantegna The Presentation in the Temple, c.1455, Tempera on canvas, 77 x 94 cm, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin; 29, ... You take in the imploring gesture, so tender and natural, of the Christ child seeking to return to his mother's arms, the child who is nonetheless the hope of his people Israel. And then, at the rear of the scene, the golden ...

The priest Simeon is shown receiving the infant Christ from the Virgin Mary in front of an elaborate altar. The scene is based on a passage in the Gospel of Luke (2:22-40), which describes Mary and Joseph's visit to the temple in Jerusalem for the rituals of Mary's purification and of Christ's presentation to God.

To be a light to lighten the Gentiles, and to be the glory of thy people Israel. Amen. Today is the Feast of the Presentation of our Lord Jesus Christ in the Temple. It's a major feast in our calendar but one we observe at Grace only when it falls on a Sunday. It commemorates the events recorded by Luke in today's gospel reading.

Other articles where Presentation in the Temple is discussed: Albrecht Dürer: Second journey to Italy of Albrecht Dürer: …Bellini's free adaptation of Mantegna's Presentation in the Temple. Dürer's work is a virtuoso performance that shows mastery and close attention to detail. In the painting the inscription on the scrap of paper out of the book held by the old man in the ...

History. The dating of the work is uncertain, though it is usually considered to be subsequent to the Presentation at the Temple by Andrea Mantegna (Berlin, c. 1455), from which Bellini took a very similar placement of the figures.. The commission of the two works is unknown, as well as if the figures, as is sometimes suggested, portrayed members of the Mantegna and Bellini families.

The medium used in the portrait on presentation at the temple is Tempera on panel .The group is fixed in a 80cm × 105cm a pale, marble frame that seems to separate them from the crowd as it shows them to be on a church altar. The portrait by Giovanni looks like that of the brother in law Andrea Mantegna. He got the painting inspiration from ...

The story is taken from St Luke's Gospel, when Mary and Joseph take the baby Jesus to the temple, as required for a first-born son. Joseph carries two turtle doves in a basket as an offering, with flames in the altar to emphasise the custom. The devout ageing Simeon receives the vision of the Messiah promised to him by God, as he holds the infant.

Presentation of Jesus at the Temple by Fra Angelico. Presentazione di Gesù al Tempio is a fresco by Fra Angelico made for the then Dominican Convent of Saint Mark in Florence, Italy. [1] [2] It depicts the dedication of Jesus in the Temple in Jerusalem as the first-born son of His family, as related in the Gospel of St. Luke, 2:23-24.

An exterior rendering of The Lone Mountain Temple was released on Feb. 26, 2024. It will be the second temple built in Las Vegas by the LDS church. (Photo provided by The Church Of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.) After a six-hour meeting Christian Salmon, a lone Mountain resident, reacted to the vote that he and his neighbors opposed.

LAS VEGAS, Nev. (FOX5) - Crowds showed up to support a plan for a new temple for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as neighbors continue their fierce opposition to the proposal. The ...