Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Research recommendations play a crucial role in guiding scholars and researchers toward fruitful avenues of exploration. In an era marked by rapid technological advancements and an ever-expanding knowledge base, refining the process of generating research recommendations becomes imperative.

But, what is a research recommendation?

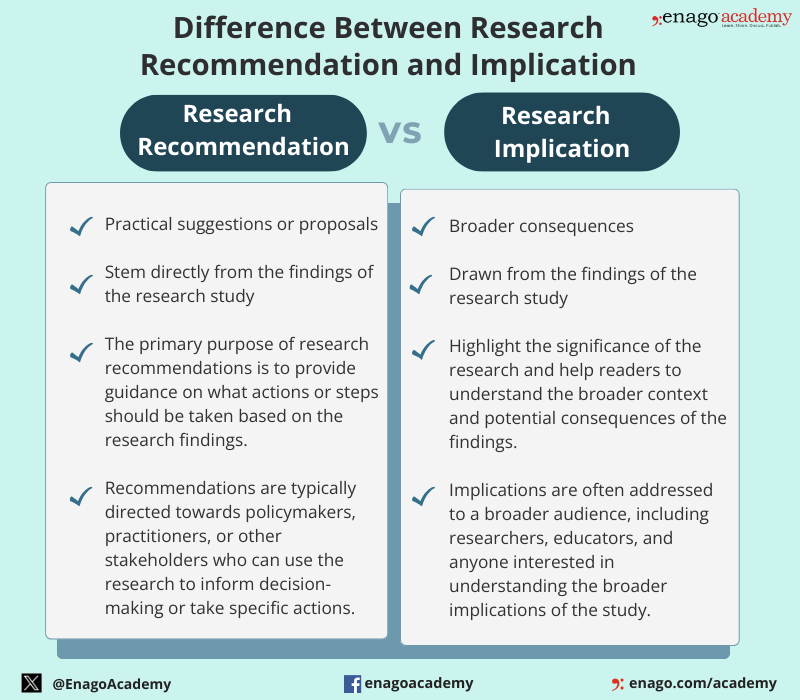

Research recommendations are suggestions or advice provided to researchers to guide their study on a specific topic . They are typically given by experts in the field. Research recommendations are more action-oriented and provide specific guidance for decision-makers, unlike implications that are broader and focus on the broader significance and consequences of the research findings. However, both are crucial components of a research study.

Difference Between Research Recommendations and Implication

Although research recommendations and implications are distinct components of a research study, they are closely related. The differences between them are as follows:

Types of Research Recommendations

Recommendations in research can take various forms, which are as follows:

These recommendations aim to assist researchers in navigating the vast landscape of academic knowledge.

Let us dive deeper to know about its key components and the steps to write an impactful research recommendation.

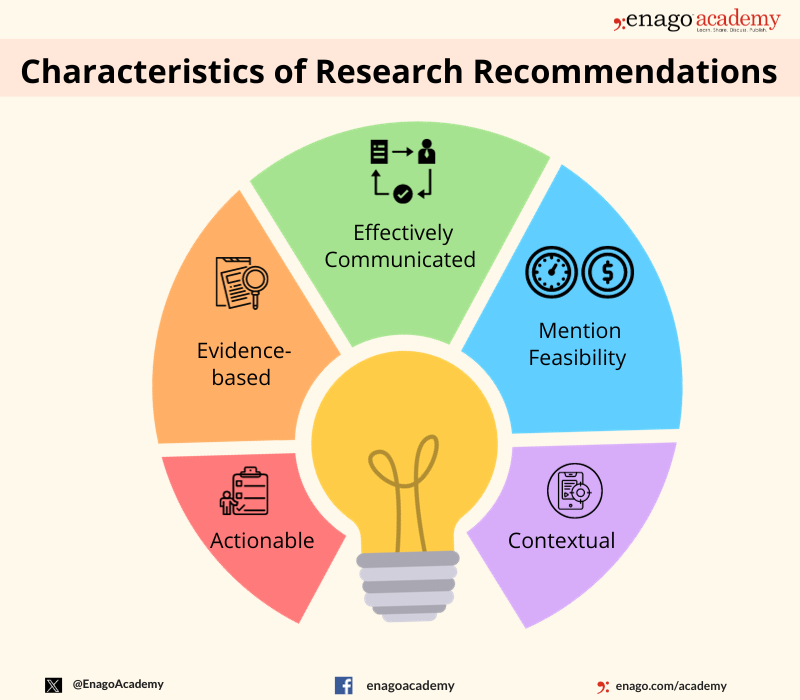

Key Components of Research Recommendations

The key components of research recommendations include defining the research question or objective, specifying research methods, outlining data collection and analysis processes, presenting results and conclusions, addressing limitations, and suggesting areas for future research. Here are some characteristics of research recommendations:

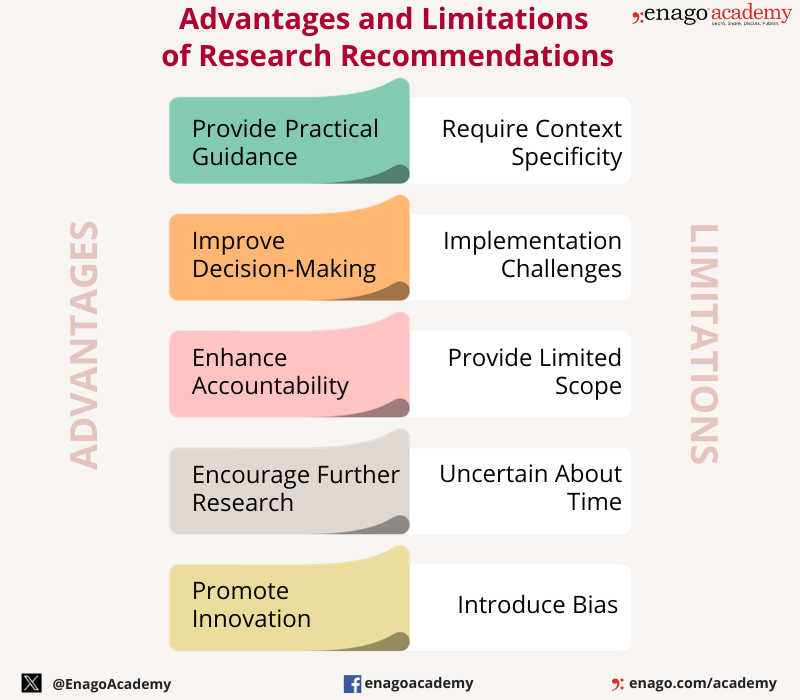

Research recommendations offer various advantages and play a crucial role in ensuring that research findings contribute to positive outcomes in various fields. However, they also have few limitations which highlights the significance of a well-crafted research recommendation in offering the promised advantages.

The importance of research recommendations ranges in various fields, influencing policy-making, program development, product development, marketing strategies, medical practice, and scientific research. Their purpose is to transfer knowledge from researchers to practitioners, policymakers, or stakeholders, facilitating informed decision-making and improving outcomes in different domains.

How to Write Research Recommendations?

Research recommendations can be generated through various means, including algorithmic approaches, expert opinions, or collaborative filtering techniques. Here is a step-wise guide to build your understanding on the development of research recommendations.

1. Understand the Research Question:

Understand the research question and objectives before writing recommendations. Also, ensure that your recommendations are relevant and directly address the goals of the study.

2. Review Existing Literature:

Familiarize yourself with relevant existing literature to help you identify gaps , and offer informed recommendations that contribute to the existing body of research.

3. Consider Research Methods:

Evaluate the appropriateness of different research methods in addressing the research question. Also, consider the nature of the data, the study design, and the specific objectives.

4. Identify Data Collection Techniques:

Gather dataset from diverse authentic sources. Include information such as keywords, abstracts, authors, publication dates, and citation metrics to provide a rich foundation for analysis.

5. Propose Data Analysis Methods:

Suggest appropriate data analysis methods based on the type of data collected. Consider whether statistical analysis, qualitative analysis, or a mixed-methods approach is most suitable.

6. Consider Limitations and Ethical Considerations:

Acknowledge any limitations and potential ethical considerations of the study. Furthermore, address these limitations or mitigate ethical concerns to ensure responsible research.

7. Justify Recommendations:

Explain how your recommendation contributes to addressing the research question or objective. Provide a strong rationale to help researchers understand the importance of following your suggestions.

8. Summarize Recommendations:

Provide a concise summary at the end of the report to emphasize how following these recommendations will contribute to the overall success of the research project.

By following these steps, you can create research recommendations that are actionable and contribute meaningfully to the success of the research project.

Download now to unlock some tips to improve your journey of writing research recommendations.

Example of a Research Recommendation

Here is an example of a research recommendation based on a hypothetical research to improve your understanding.

Research Recommendation: Enhancing Student Learning through Integrated Learning Platforms

Background:

The research study investigated the impact of an integrated learning platform on student learning outcomes in high school mathematics classes. The findings revealed a statistically significant improvement in student performance and engagement when compared to traditional teaching methods.

Recommendation:

In light of the research findings, it is recommended that educational institutions consider adopting and integrating the identified learning platform into their mathematics curriculum. The following specific recommendations are provided:

- Implementation of the Integrated Learning Platform:

Schools are encouraged to adopt the integrated learning platform in mathematics classrooms, ensuring proper training for teachers on its effective utilization.

- Professional Development for Educators:

Develop and implement professional programs to train educators in the effective use of the integrated learning platform to address any challenges teachers may face during the transition.

- Monitoring and Evaluation:

Establish a monitoring and evaluation system to track the impact of the integrated learning platform on student performance over time.

- Resource Allocation:

Allocate sufficient resources, both financial and technical, to support the widespread implementation of the integrated learning platform.

By implementing these recommendations, educational institutions can harness the potential of the integrated learning platform and enhance student learning experiences and academic achievements in mathematics.

This example covers the components of a research recommendation, providing specific actions based on the research findings, identifying the target audience, and outlining practical steps for implementation.

Using AI in Research Recommendation Writing

Enhancing research recommendations is an ongoing endeavor that requires the integration of cutting-edge technologies, collaborative efforts, and ethical considerations. By embracing data-driven approaches and leveraging advanced technologies, the research community can create more effective and personalized recommendation systems. However, it is accompanied by several limitations. Therefore, it is essential to approach the use of AI in research with a critical mindset, and complement its capabilities with human expertise and judgment.

Here are some limitations of integrating AI in writing research recommendation and some ways on how to counter them.

1. Data Bias

AI systems rely heavily on data for training. If the training data is biased or incomplete, the AI model may produce biased results or recommendations.

How to tackle: Audit regularly the model’s performance to identify any discrepancies and adjust the training data and algorithms accordingly.

2. Lack of Understanding of Context:

AI models may struggle to understand the nuanced context of a particular research problem. They may misinterpret information, leading to inaccurate recommendations.

How to tackle: Use AI to characterize research articles and topics. Employ them to extract features like keywords, authorship patterns and content-based details.

3. Ethical Considerations:

AI models might stereotype certain concepts or generate recommendations that could have negative consequences for certain individuals or groups.

How to tackle: Incorporate user feedback mechanisms to reduce redundancies. Establish an ethics review process for AI models in research recommendation writing.

4. Lack of Creativity and Intuition:

AI may struggle with tasks that require a deep understanding of the underlying principles or the ability to think outside the box.

How to tackle: Hybrid approaches can be employed by integrating AI in data analysis and identifying patterns for accelerating the data interpretation process.

5. Interpretability:

Many AI models, especially complex deep learning models, lack transparency on how the model arrived at a particular recommendation.

How to tackle: Implement models like decision trees or linear models. Provide clear explanation of the model architecture, training process, and decision-making criteria.

6. Dynamic Nature of Research:

Research fields are dynamic, and new information is constantly emerging. AI models may struggle to keep up with the rapidly changing landscape and may not be able to adapt to new developments.

How to tackle: Establish a feedback loop for continuous improvement. Regularly update the recommendation system based on user feedback and emerging research trends.

The integration of AI in research recommendation writing holds great promise for advancing knowledge and streamlining the research process. However, navigating these concerns is pivotal in ensuring the responsible deployment of these technologies. Researchers need to understand the use of responsible use of AI in research and must be aware of the ethical considerations.

Exploring research recommendations plays a critical role in shaping the trajectory of scientific inquiry. It serves as a compass, guiding researchers toward more robust methodologies, collaborative endeavors, and innovative approaches. Embracing these suggestions not only enhances the quality of individual studies but also contributes to the collective advancement of human understanding.

Frequently Asked Questions

The purpose of recommendations in research is to provide practical and actionable suggestions based on the study's findings, guiding future actions, policies, or interventions in a specific field or context. Recommendations bridges the gap between research outcomes and their real-world application.

To make a research recommendation, analyze your findings, identify key insights, and propose specific, evidence-based actions. Include the relevance of the recommendations to the study's objectives and provide practical steps for implementation.

Begin a recommendation by succinctly summarizing the key findings of the research. Clearly state the purpose of the recommendation and its intended impact. Use a direct and actionable language to convey the suggested course of action.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Reporting Research

How to Effectively Cite a PDF (APA, MLA, AMA, and Chicago Style)

The pressure to “publish or perish” is a well-known reality for academics, striking fear into…

- AI in Academia

- Trending Now

Using AI for Journal Selection — Simplifying your academic publishing journey in the smart way

Strategic journal selection plays a pivotal role in maximizing the impact of one’s scholarly work.…

- Career Corner

Recognizing the signs: A guide to overcoming academic burnout

As the sun set over the campus, casting long shadows through the library windows, Alex…

- Diversity and Inclusion

Reassessing the Lab Environment to Create an Equitable and Inclusive Space

The pursuit of scientific discovery has long been fueled by diverse minds and perspectives. Yet…

Simplifying the Literature Review Journey — A comparative analysis of 6 AI summarization tools

Imagine having to skim through and read mountains of research papers and books, only to…

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

Digital Citations: A comprehensive guide to citing of websites in APA, MLA, and CMOS…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for…

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- How to formulate...

How to formulate research recommendations

- Related content

- Peer review

- Polly Brown ( pbrown{at}bmjgroup.com ) , publishing manager 1 ,

- Klara Brunnhuber , clinical editor 1 ,

- Kalipso Chalkidou , associate director, research and development 2 ,

- Iain Chalmers , director 3 ,

- Mike Clarke , director 4 ,

- Mark Fenton , editor 3 ,

- Carol Forbes , reviews manager 5 ,

- Julie Glanville , associate director/information service manager 5 ,

- Nicholas J Hicks , consultant in public health medicine 6 ,

- Janet Moody , identification and prioritisation manager 6 ,

- Sara Twaddle , director 7 ,

- Hazim Timimi , systems developer 8 ,

- Pamela Young , senior programme manager 6

- 1 BMJ Publishing Group, London WC1H 9JR,

- 2 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, London WC1V 6NA,

- 3 Database of Uncertainties about the Effects of Treatments, James Lind Alliance Secretariat, James Lind Initiative, Oxford OX2 7LG,

- 4 UK Cochrane Centre, Oxford OX2 7LG,

- 5 Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York, York YO10 5DD,

- 6 National Coordinating Centre for Health Technology Assessment, University of Southampton, Southampton SO16 7PX,

- 7 Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, Edinburgh EH2 1EN,

- 8 Update Software, Oxford OX2 7LG

- Correspondence to: PBrown

- Accepted 22 September 2006

“More research is needed” is a conclusion that fits most systematic reviews. But authors need to be more specific about what exactly is required

Long awaited reports of new research, systematic reviews, and clinical guidelines are too often a disappointing anticlimax for those wishing to use them to direct future research. After many months or years of effort and intellectual energy put into these projects, authors miss the opportunity to identify unanswered questions and outstanding gaps in the evidence. Most reports contain only a less than helpful, general research recommendation. This means that the potential value of these recommendations is lost.

Current recommendations

In 2005, representatives of organisations commissioning and summarising research, including the BMJ Publishing Group, the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, the National Coordinating Centre for Health Technology Assessment, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, and the UK Cochrane Centre, met as members of the development group for the Database of Uncertainties about the Effects of Treatments (see bmj.com for details on all participating organisations). Our aim was to discuss the state of research recommendations within our organisations and to develop guidelines for improving the presentation of proposals for further research. All organisations had found weaknesses in the way researchers and authors of systematic reviews and clinical guidelines stated the need for further research. As part of the project, a member of the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination under-took a rapid literature search to identify information on research recommendation models, which found some individual methods but no group initiatives to attempt to standardise recommendations.

Suggested format for research recommendations on the effects of treatments

Core elements.

E Evidence (What is the current state of the evidence?)

P Population (What is the population of interest?)

I Intervention (What are the interventions of interest?)

C Comparison (What are the comparisons of interest?)

O Outcome (What are the outcomes of interest?)

T Time stamp (Date of recommendation)

Optional elements

d Disease burden or relevance

t Time aspect of core elements of EPICOT

s Appropriate study type according to local need

In January 2006, the National Coordinating Centre for Health Technology Assessment presented the findings of an initial comparative analysis of how different organisations currently structure their research recommendations. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence and the National Coordinating Centre for Health Technology Assessment request authors to present recommendations in a four component format for formulating well built clinical questions around treatments: population, intervention, comparison, and outcomes (PICO). 1 In addition, the research recommendation is dated and authors are asked to provide the current state of the evidence to support the proposal.

Clinical Evidence , although not directly standardising its sections for research recommendations, presents gaps in the evidence using a slightly extended version of the PICO format: evidence, population, intervention, comparison, outcomes, and time (EPICOT). Clinical Evidence has used this inherent structure to feed research recommendations on interventions categorised as “unknown effectiveness” back to the National Coordinating Centre for Health Technology Assessment and for inclusion in the Database of Uncertainties about the Effects of Treatments ( http://www.duets.nhs.uk/ ).

We decided to propose the EPICOT format as the basis for its statement on formulating research recommendations and tested this proposal through discussion and example. We agreed that this set of components provided enough context for formulating research recommendations without limiting researchers. In order for the proposed framework to be flexible and more widely applicable, the group discussed using several optional components when they seemed relevant or were proposed by one or more of the group members. The final outcome of discussions resulted in the proposed EPICOT+ format (box).

A recent BMJ article highlighted how lack of research hinders the applicability of existing guidelines to patients in primary care who have had a stroke or transient ischaemic attack. 2 Most research in the area had been conducted in younger patients with a recent episode and in a hospital setting. The authors concluded that “further evidence should be collected on the efficacy and adverse effects of intensive blood pressure lowering in representative populations before we implement this guidance [from national and international guidelines] in primary care.” Table 1 outlines how their recommendations could be formulated using the EPICOT+ format. The decision on whether additional research is indeed clinically and ethically warranted will still lie with the organisation considering commissioning the research.

Research recommendation based on gap in the evidence identified by a cross sectional study of clinical guidelines for management of patients who have had a stroke

- View inline

Table 2 shows the use of EPICOT+ for an unanswered question on the effectiveness of compliance therapy in people with schizophrenia, identified by the Database of Uncertainties about the Effects of Treatments.

Research recommendation based on a gap in the evidence on treatment of schizophrenia identified by the Database of Uncertainties about the Effects of Treatments

Discussions around optional elements

Although the group agreed that the PICO elements should be core requirements for a research recommendation, intense discussion centred on the inclusion of factors defining a more detailed context, such as current state of evidence (E), appropriate study type (s), disease burden and relevance (d), and timeliness (t).

Initially, group members interpreted E differently. Some viewed it as the supporting evidence for a research recommendation and others as the suggested study type for a research recommendation. After discussion, we agreed that E should be used to refer to the amount and quality of research supporting the recommendation. However, the issue remained contentious as some of us thought that if a systematic review was available, its reference would sufficiently identify the strength of the existing evidence. Others thought that adding evidence to the set of core elements was important as it provided a summary of the supporting evidence, particularly as the recommendation was likely to be abstracted and used separately from the review or research that led to its formulation. In contrast, the suggested study type (s) was left as an optional element.

A research recommendation will rarely have an absolute value in itself. Its relative priority will be influenced by the burden of ill health (d), which is itself dependent on factors such as local prevalence, disease severity, relevant risk factors, and the priorities of the organisation considering commissioning the research.

Similarly, the issue of time (t) could be seen to be relevant to each of the core elements in varying ways—for example, duration of treatment, length of follow-up. The group therefore agreed that time had a subsidiary role within each core item; however, T as the date of the recommendation served to define its shelf life and therefore retained individual importance.

Applicability and usability

The proposed statement on research recommendations applies to uncertainties of the effects of any form of health intervention or treatment and is intended for research in humans rather than basic scientific research. Further investigation is required to assess the applicability of the format for questions around diagnosis, signs and symptoms, prognosis, investigations, and patient preference.

When the proposed format is applied to a specific research recommendation, the emphasis placed on the relevant part(s) of the EPICOT+ format may vary by author, audience, and intended purpose. For example, a recommendation for research into treatments for transient ischaemic attack may or may not define valid outcome measures to assess quality of life or gather data on adverse effects. Among many other factors, its implementation will also depend on the strength of current findings—that is, strong evidence may support a tightly focused recommendation whereas a lack of evidence would result in a more general recommendation.

The controversy within the group, especially around the optional components, reflects the different perspectives of the participating organisations—whether they were involved in commissioning, undertaking, or summarising research. Further issues will arise during the implementation of the proposed format, and we welcome feedback and discussion.

Summary points

No common guidelines exist for the formulation of recommendations for research on the effects of treatments

Major organisations involved in commissioning or summarising research compared their approaches and agreed on core questions

The essential items can be summarised as EPICOT+ (evidence, population, intervention, comparison, outcome, and time)

Further details, such as disease burden and appropriate study type, should be considered as required

We thank Patricia Atkinson and Jeremy Wyatt.

Contributors and sources All authors contributed to manuscript preparation and approved the final draft. NJH is the guarantor.

Competing interests None declared.

- Richardson WS ,

- Wilson MC ,

- Nishikawa J ,

- Hayward RSA

- McManus RJ ,

- Leonardi-Bee J ,

- PROGRESS Collaborative Group

- Warburton E

- Rothwell P ,

- McIntosh AM ,

- Lawrie SM ,

- Stanfield AC

- O'Donnell C ,

- Donohoe G ,

- Sharkey L ,

- Jablensky A ,

- Sartorius N ,

- Ernberg G ,

Implications or Recommendations in Research: What's the Difference?

- Peer Review

High-quality research articles that get many citations contain both implications and recommendations. Implications are the impact your research makes, whereas recommendations are specific actions that can then be taken based on your findings, such as for more research or for policymaking.

Updated on August 23, 2022

That seems clear enough, but the two are commonly confused.

This confusion is especially true if you come from a so-called high-context culture in which information is often implied based on the situation, as in many Asian cultures. High-context cultures are different from low-context cultures where information is more direct and explicit (as in North America and many European cultures).

Let's set these two straight in a low-context way; i.e., we'll be specific and direct! This is the best way to be in English academic writing because you're writing for the world.

Implications and recommendations in a research article

The standard format of STEM research articles is what's called IMRaD:

- Introduction

- Discussion/conclusions

Some journals call for a separate conclusions section, while others have the conclusions as the last part of the discussion. You'll write these four (or five) sections in the same sequence, though, no matter the journal.

The discussion section is typically where you restate your results and how well they confirmed your hypotheses. Give readers the answer to the questions for which they're looking to you for an answer.

At this point, many researchers assume their paper is finished. After all, aren't the results the most important part? As you might have guessed, no, you're not quite done yet.

The discussion/conclusions section is where to say what happened and what should now happen

The discussion/conclusions section of every good scientific article should contain the implications and recommendations.

The implications, first of all, are the impact your results have on your specific field. A high-impact, highly cited article will also broaden the scope here and provide implications to other fields. This is what makes research cross-disciplinary.

Recommendations, however, are suggestions to improve your field based on your results.

These two aspects help the reader understand your broader content: How and why your work is important to the world. They also tell the reader what can be changed in the future based on your results.

These aspects are what editors are looking for when selecting papers for peer review.

Implications and recommendations are, thus, written at the end of the discussion section, and before the concluding paragraph. They help to “wrap up” your paper. Once your reader understands what you found, the next logical step is what those results mean and what should come next.

Then they can take the baton, in the form of your work, and run with it. That gets you cited and extends your impact!

The order of implications and recommendations also matters. Both are written after you've summarized your main findings in the discussion section. Then, those results are interpreted based on ongoing work in the field. After this, the implications are stated, followed by the recommendations.

Writing an academic research paper is a bit like running a race. Finish strong, with your most important conclusion (recommendation) at the end. Leave readers with an understanding of your work's importance. Avoid generic, obvious phrases like "more research is needed to fully address this issue." Be specific.

The main differences between implications and recommendations (table)

Now let's dig a bit deeper into actually how to write these parts.

What are implications?

Research implications tell us how and why your results are important for the field at large. They help answer the question of “what does it mean?” Implications tell us how your work contributes to your field and what it adds to it. They're used when you want to tell your peers why your research is important for ongoing theory, practice, policymaking, and for future research.

Crucially, your implications must be evidence-based. This means they must be derived from the results in the paper.

Implications are written after you've summarized your main findings in the discussion section. They come before the recommendations and before the concluding paragraph. There is no specific section dedicated to implications. They must be integrated into your discussion so that the reader understands why the results are meaningful and what they add to the field.

A good strategy is to separate your implications into types. Implications can be social, political, technological, related to policies, or others, depending on your topic. The most frequently used types are theoretical and practical. Theoretical implications relate to how your findings connect to other theories or ideas in your field, while practical implications are related to what we can do with the results.

Key features of implications

- State the impact your research makes

- Helps us understand why your results are important

- Must be evidence-based

- Written in the discussion, before recommendations

- Can be theoretical, practical, or other (social, political, etc.)

Examples of implications

Let's take a look at some examples of research results below with their implications.

The result : one study found that learning items over time improves memory more than cramming material in a bunch of information at once .

The implications : This result suggests memory is better when studying is spread out over time, which could be due to memory consolidation processes.

The result : an intervention study found that mindfulness helps improve mental health if you have anxiety.

The implications : This result has implications for the role of executive functions on anxiety.

The result : a study found that musical learning helps language learning in children .

The implications : these findings suggest that language and music may work together to aid development.

What are recommendations?

As noted above, explaining how your results contribute to the real world is an important part of a successful article.

Likewise, stating how your findings can be used to improve something in future research is equally important. This brings us to the recommendations.

Research recommendations are suggestions and solutions you give for certain situations based on your results. Once the reader understands what your results mean with the implications, the next question they need to know is "what's next?"

Recommendations are calls to action on ways certain things in the field can be improved in the future based on your results. Recommendations are used when you want to convey that something different should be done based on what your analyses revealed.

Similar to implications, recommendations are also evidence-based. This means that your recommendations to the field must be drawn directly from your results.

The goal of the recommendations is to make clear, specific, and realistic suggestions to future researchers before they conduct a similar experiment. No matter what area your research is in, there will always be further research to do. Try to think about what would be helpful for other researchers to know before starting their work.

Recommendations are also written in the discussion section. They come after the implications and before the concluding paragraphs. Similar to the implications, there is usually no specific section dedicated to the recommendations. However, depending on how many solutions you want to suggest to the field, they may be written as a subsection.

Key features of recommendations

- Statements about what can be done differently in the field based on your findings

- Must be realistic and specific

- Written in the discussion, after implications and before conclusions

- Related to both your field and, preferably, a wider context to the research

Examples of recommendations

Here are some research results and their recommendations.

A meta-analysis found that actively recalling material from your memory is better than simply re-reading it .

- The recommendation: Based on these findings, teachers and other educators should encourage students to practice active recall strategies.

A medical intervention found that daily exercise helps prevent cardiovascular disease .

- The recommendation: Based on these results, physicians are recommended to encourage patients to exercise and walk regularly. Also recommended is to encourage more walking through public health offices in communities.

A study found that many research articles do not contain the sample sizes needed to statistically confirm their findings .

The recommendation: To improve the current state of the field, researchers should consider doing power analysis based on their experiment's design.

What else is important about implications and recommendations?

When writing recommendations and implications, be careful not to overstate the impact of your results. It can be tempting for researchers to inflate the importance of their findings and make grandiose statements about what their work means.

Remember that implications and recommendations must be coming directly from your results. Therefore, they must be straightforward, realistic, and plausible.

Another good thing to remember is to make sure the implications and recommendations are stated clearly and separately. Do not attach them to the endings of other paragraphs just to add them in. Use similar example phrases as those listed in the table when starting your sentences to clearly indicate when it's an implication and when it's a recommendation.

When your peers, or brand-new readers, read your paper, they shouldn't have to hunt through your discussion to find the implications and recommendations. They should be clear, visible, and understandable on their own.

That'll get you cited more, and you'll make a greater contribution to your area of science while extending the life and impact of your work.

The AJE Team

See our "Privacy Policy"

Turn your research insights into actionable recommendations

At the end of one presentation, my colleague approached me and asked what I recommended based on the research. I was a bit puzzled. I didn’t expect anyone to ask me this kind of question. By that point in my career, I wasn’t aware that I had to make recommendations based on the research insights. I could talk about the next steps regarding what other research we had to conduct. I could also relay the information that something wasn’t working in a prototype, but I had no idea what to suggest.

How to move from qualitative data to actionable insights

Over time, more and more colleagues asked for these recommendations. Finally, I realized that one of the key pieces I was missing in my reports was the “so what?” The prototype isn’t working, so what do we do next? Because I didn’t include suggestions, my colleagues had a difficult time marrying actions to my insights. Sure, the team could see the noticeable changes, but the next steps were a struggle, especially for generative research.

Without these suggestions, my insights started to fall flat. My colleagues were excited about them and loved seeing the video clips, but they weren’t working with the findings. With this, I set out to experiment on how to write recommendations within a user research report.

.css-1nrevy2{position:relative;display:inline-block;} How to write recommendations

For a while, I wasn’t sure how to write recommendations. And, even now, I believe there is no one right way . When I first started looking into this, I started with two main questions:

What do recommendations mean to stakeholders?

How prescriptive should recommendations be?

When people asked me for recommendations, I had no idea what they were looking for. I was nervous I would step on people’s toes and give the impression I thought I knew more than I did. I wasn’t a designer and didn’t want to make whacky design recommendations or impractical suggestions that would get developers rolling their eyes.

When in doubt, I dusted off my internal research cap and sat with stakeholders to understand what they meant by recommendations. I asked them for examples of what they expected and what made a suggestion “helpful” or “actionable.” I walked away with a list of “must-haves” for my recommendations. They had to be:

Flexible. Just because I made an initial recommendation did not mean it was the only path forward. Once I presented the recommendations, we could talk through other ideas and consider new information. There were a few times when I revised my recommendations based on conversations I had with colleagues.

Feasible. At first, I started presenting my recommendations without any prior feedback. My worst nightmare came true. The designer and developer sat back, arms crossed, and said, “A lot of this is impossible.” I quickly learned to review some of my recommendations I was uncertain about with them beforehand. Alternatively, I came up with several recommendations for one solution to help combat this problem.

Prioritized (to my best abilities). Since I am not entirely sure of the recommendation’s effort, I use a chart of impact and reach to prioritize suggestions. Then, once I present this list, it may get reprioritized depending on effort levels from the team (hey, flexibility!).

Detailed. This point helped me a lot with my second question regarding how in-depth I should make my recommendations. Some of the best detail comes from photos, videos, or screenshots, and colleagues appreciated when I linked recommendations with this media. They also told me to put in as much detail as possible to avoid vagueness, misinterpretation, and endless debate.

Think MVP. Think about the solution with the fewest changes instead of recommending complex changes to a feature or product. What are some minor changes that the team can make to improve the experience or product?

Justified. This part was the hardest for me. When my research findings didn’t align with expectations or business goals, I had no idea what to say. When I receive results that highlight we are going in the wrong direction, my recommendations become even more critical. Instead of telling the team that the new product or feature sucks and we should stop working on it, I offer alternatives. I follow the concept of “no, but...” So, “no, this isn’t working, but we found that users value X and Y, which could lead to increased retention” (or whatever metric we were looking at.

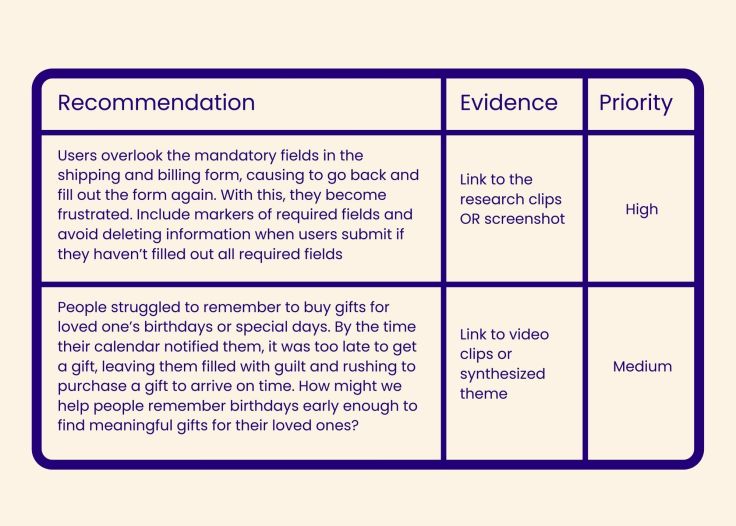

Let’s look at some examples

Although this list was beneficial in guiding my recommendations, I still wasn’t well-versed in how to write them. So, after some time, I created a formula for writing recommendations:

Observed problem/pain point/unmet need + consequence + potential solution

Evaluative research

Let’s imagine we are testing a check-out page, and we found that users were having a hard time filling out the shipping and billing forms, especially when there were two different addresses.

A non-specific and unhelpful recommendation might look like :

Users get frustrated when filling out the shipping and billing form.

The reasons this recommendation is not ideal are :

It provides no context or detail of the problem

There is no proposed solution

It sounds a bit judgemental (focus on the problem!)

There is no immediate movement forward with this

A redesign recommendation about the same problem might look like this :

Users overlook the mandatory fields in the shipping and billing form, causing them to go back and fill out the form again. With this, they become frustrated. Include markers of required fields and avoid deleting information when users submit if they haven’t filled out all required fields.

Let’s take another example :

We tested an entirely new concept for our travel company, allowing people to pay to become “prime” travel members. In our user base, no one found any value in having or paying for a membership. However, they did find value in several of the features, such as sharing trips with family members or splitting costs but could not justify paying for them.

A suboptimal recommendation could look like this :

Users would not sign-up or pay for a prime membership.

Again, there is a considerable lack of context and understanding here, as well as action. Instead, we could try something like:

Users do not find enough value in the prime membership to sign-up or pay for it. Therefore, they do not see themselves using the feature. However, they did find value in two features: sharing trips with friends and splitting the trip costs. Focusing, instead, on these features could bring more people to our platform and increase retention.

Generative research

Generative research can look a bit trickier because there isn’t always an inherent problem you are solving. For example, you might not be able to point to a usability issue, so you have to look more broadly at pain points or unmet needs.

For example, in our generative research, we found that people often forget to buy gifts for loved ones, making them feel guilty and rushed at the last minute to find something meaningful but quickly.

This finding is extremely broad and could go in so many directions. With suggestions, we don’t necessarily want to lead our teams down only one path (flexibility!), but we also don’t want to leave the recommendation too vague (detailed). I use How Might We statements to help me build generative research recommendations.

Just reporting the above wouldn’t entirely be enough for a recommendation, so let’s try to put it in a more actionable format:

People struggled to remember to buy gifts for loved one’s birthdays or special days. By the time their calendar notified them, it was too late to get a gift, leaving them filled with guilt and rushing to purchase a meaningful gift to arrive on time. How might we help people remember birthdays early enough to find meaningful gifts for their loved ones?

A great follow-up to generative research recommendations can be running an ideation workshop !

Researching the right thing versus researching the thing right

How to format recommendations in your report.

I always end with recommendations because people leave a presentation with their minds buzzing and next steps top of mind (hopefully!). My favorite way to format suggestions is in a chart. That way, I can link the recommendation back to the insight and priority. My recommendations look like this:

Overall, play around with the recommendations that you give to your teams. The best thing you can do is ask for what they expect and then ask for feedback. By catering and iterating to your colleagues’ needs, you will help them make better decisions based on your research insights!

Written by Nikki Anderson, User Research Lead & Instructor. Nikki is a User Research Lead and Instructor with over eight years of experience. She has worked in all different sizes of companies, ranging from a tiny start-up called ALICE to large corporation Zalando, and also as a freelancer. During this time, she has led a diverse range of end-to-end research projects across the world, specializing in generative user research. Nikki also owns her own company, User Research Academy, a community and education platform designed to help people get into the field of user research, or learn more about how user research impacts their current role. User Research Academy hosts online classes, content, as well as personalized mentorship opportunities with Nikki. She is extremely passionate about teaching and supporting others throughout their journey in user research. To spread the word of research and help others transition and grow in the field, she writes as a writer at dscout and Dovetail. Outside of the world of user research, you can find Nikki (happily) surrounded by animals, including her dog and two cats, reading on her Kindle, playing old-school video games like Pokemon and World of Warcraft, and writing fiction novels.

Keep reading

.css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} Decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next

Decide what to build next.

Users report unexpectedly high data usage, especially during streaming sessions.

Users find it hard to navigate from the home page to relevant playlists in the app.

It would be great to have a sleep timer feature, especially for bedtime listening.

I need better filters to find the songs or artists I’m looking for.

Log in or sign up

Get started for free

Undergraduate Research Experiences for STEM Students: Successes, Challenges, and Opportunities (2017)

Chapter: 9 conclusions and recommendations, 9 conclusions and recommendations.

Practitioners designing or improving undergraduate research experiences (UREs) can build on the experiences of colleagues and learn from the increasingly robust literature about UREs and the considerable body of evidence about how students learn. The questions practitioners ask themselves during the design process should include questions about the goals of the campus, program, faculty, and students. Other factors to consider when designing a URE include the issues raised in the conceptual framework for learning and instruction, the available resources, how the program or experience will be evaluated or studied, and how to design the program from the outset to incorporate these considerations, as well as how to build in opportunities to improve the experience over time in light of new evidence. (Some of these topics are addressed in Chapter 8 .)

Colleges and universities that offer or wish to offer UREs to their students should undertake baseline evaluations of their current offerings and create plans to develop a culture of improvement in which faculty are supported in their efforts to continuously refine UREs based on the evidence currently available and evidence that they and others generate in the future. While much of the evidence to date is descriptive, it forms a body of knowledge that can be used to identify research questions about UREs, both those designed around the apprenticeship model and those designed using the more recent course-based undergraduate research experience (CURE) model. Internships and other avenues by which undergraduates do research provide many of the same sorts of experiences but are not well studied. In any case, it is clear that students value these experiences; that many faculty do as well; and that they contribute to broadening participation in science,

technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education and careers. The findings from the research literature reported in Chapter 4 provide guidance to those designing both opportunities to improve practical and academic skills and opportunities for students to “try out” a professional role of interest.

Little research has been done that provides answers to mechanistic questions about how UREs work. Additional studies are needed to know which features of UREs are most important for positive outcomes with which students and to gain information about other questions of this type. This additional research is needed to better understand and compare different strategies for UREs designed for a diversity of students, mentors, and institutions. Therefore, the committee recommends steps that could increase the quantity and quality of evidence available in the future and makes recommendations for how faculty, departments, and institutions might approach decisions about UREs using currently available information. Multiple detailed recommendations about the kinds of research that might be useful are provided in the research agenda in Chapter 7 .

In addition to the specific research recommended in Chapter 7 , in this chapter the committee provides a series of interrelated conclusions and recommendations related to UREs for the STEM disciplines and intended to highlight the issues of primary importance to administrators, URE program designers, mentors to URE students, funders of UREs, those leading the departments and institutions offering UREs, and those conducting research about UREs. These conclusions and recommendations are based on the expert views of the committee and informed by their review of the available research, the papers commissioned for this report, and input from presenters during committee meetings. Table 9-1 defines categories of these URE “actors,” gives examples of specific roles included in each category, specifies key URE actions for which that category is responsible, and lists the conclusions and recommendations the committee views as most relevant to that actor category.

RESEARCH ON URES

Conclusion 1: The current and emerging landscape of what constitutes UREs is diverse and complex. Students can engage in STEM-based undergraduate research in many different ways, across a variety of settings, and along a continuum that extends and expands upon learning opportunities in other educational settings. The following characteristics define UREs. Due to the variation in the types of UREs, not all experiences include all of the following characteristics in the same way; experiences vary in how much a particular characteristic is emphasized.

TABLE 9-1 Audiences for Committee’s Conclusions and Recommendations

- They engage students in research practices including the ability to argue from evidence.

- They aim to generate novel information with an emphasis on discovery and innovation or to determine whether recent preliminary results can be replicated.

- They focus on significant, relevant problems of interest to STEM researchers and, in some cases, a broader community (e.g., civic engagement).

- They emphasize and expect collaboration and teamwork.

- They involve iterative refinement of experimental design, experimental questions, or data obtained.

- They allow students to master specific research techniques.

- They help students engage in reflection about the problems being investigated and the work being undertaken to address those problems.

- They require communication of results, either through publication or presentations in various STEM venues.

- They are structured and guided by a mentor, with students assuming increasing ownership of some aspects of the project over time.

UREs are generally designed to add value to STEM offerings by promoting an understanding of the ways that knowledge is generated in STEM fields and to extend student learning beyond what happens in the small group work of an inquiry-based course. UREs add value by enabling students to understand and contribute to the research questions that are driving the field for one or more STEM topics or to grapple with design challenges of interest to professionals. They help students understand what it means to be a STEM researcher in a way that would be difficult to convey in a lecture course or even in an inquiry-based learning setting. As participants in a URE, students can learn by engaging in planning, experimentation, evaluation, interpretation, and communication of data and other results in light of what is already known about the question of interest. They can pose relevant questions that can be solved only through investigative or design efforts—individually or in teams—and attempt to answer these questions despite the challenges, setbacks, and ambiguity of the process and the results obtained.

The diversity of UREs reflects the reality that different STEM disciplines operate from varying traditions, expectations, and constraints (e.g., lab safety issues) in providing opportunities for undergraduates to engage in research. In addition, individual institutions and departments have cultures that promote research participation to various degrees and at different stages in students’ academic careers. Some programs emphasize design and problem solving in addition to discovery. UREs in different disciplines can

take many forms (e.g., apprentice-style, course-based, internships, project-based), but the definitional characteristics described above are similar across different STEM fields.

Furthermore, students in today’s university landscape may have opportunities to engage with many different types of UREs throughout their education, including involvement in a formal program (which could include mentoring, tutoring, research, and seminars about research), an apprentice-style URE under the guidance of an individual or team of faculty members, an internship, or enrolling in one or more CUREs or in a consortium- or project-based program.

Conclusion 2: Research on the efficacy of UREs is still in the early stages of development compared with other interventions to improve undergraduate STEM education.

- The types of UREs are diverse, and their goals are even more diverse. Questions and methodologies used to investigate the roles and effectiveness of UREs in achieving those goals are similarly diverse.

- Most of the studies of UREs to date are descriptive case studies or use correlational designs. Many of these studies report positive outcomes from engagement in a URE.

- Only a small number of studies have employed research designs that can support inferences about causation. Most of these studies find evidence for a causal relationship between URE participation and subsequent persistence in STEM. More studies are needed to provide evidence that participation in UREs is a causal factor in a range of desired student outcomes.

Taking the entire body of evidence into account, the committee concludes that the published peer-reviewed literature to date suggests that participation in a URE is beneficial for students .

As discussed in the report’s Introduction (see Chapter 1 ) and in the research agenda (see Chapter 7 ), the committee considered descriptive, causal, and mechanistic questions in our reading of the literature on UREs. Scientific approaches to answering descriptive, causal, and mechanistic questions require deciding what to look for, determining how to examine it, and knowing appropriate ways to score or quantify the effect.

Descriptive questions ask what is happening without making claims as to why it is happening—that is, without making claims as to whether the research experience caused these changes. A descriptive statement about UREs only claims that certain changes occurred during or after the time the students were engaged in undergraduate research. Descriptive studies

cannot determine whether any benefits observed were caused by participation in the URE.

Causal questions seek to discover whether a specific intervention leads to a specific outcome, other things being equal. To address such questions, causal evidence can be generated from a comparison of carefully selected groups that do and do not experience UREs. The groups can be made roughly equivalent by random assignment (ensuring that URE and non-URE groups are the same on average as the sample size increases) or by controlling for an exhaustive set of characteristics and experiences that might render the groups different prior to the URE. Other quasi-experimental strategies can also be used. Simply comparing students who enroll in a URE with students who do not is not adequate for determining causality because there may be selection bias. For example, students already interested in STEM are more likely to seek out such opportunities and more likely to be selected for such programs. Instead the investigator would have to compare future enrollment patterns (or other measures) between closely matched students, some of whom enrolled in a URE and some of whom did not. Controlling for selection bias to enable an inference about causation can pose significant challenges.

Questions of mechanism or of process also can be explored to understand why a causal intervention leads to the observed effect. Perhaps the URE enhances a student’s confidence in her ability to succeed in her chosen field or deepens her commitment to the field by exposing her to the joy of discovery. Through these pathways that act on the participant’s purposive behavior, the URE enhances the likelihood that she persists in STEM. The question for the researcher then becomes what research design would provide support for this hypothesis of mechanism over other candidate explanations for why the URE is a causal factor in STEM persistence.

The committee has examined the literature and finds a rich descriptive foundation for testable hypotheses about the effects of UREs on student outcomes. These studies are encouraging; a few of them have generated evidence that a URE can be a positive causal factor in the progression and persistence of STEM students. The weight of the evidence has been descriptive; it relies primarily on self-reports of short-term gains by students who chose to participate in UREs and does not include direct measures of changes in the students’ knowledge, skills, or other measures of success across comparable groups of students who did and did not participate in UREs.

While acknowledging the scarcity of strong causal evidence on the benefits of UREs, the committee takes seriously the weight of the descriptive evidence. Many of the published studies of UREs show that students who participate report a range of benefits, such as increased understanding of the research process, encouragement to persist in STEM, and support that helps them sustain their identity as researchers and continue with their

plans to enroll in a graduate program in STEM (see Chapter 4 ). These are effective starting points for causal studies.

Conclusion 3: Studies focused on students from historically underrepresented groups indicate that participation in UREs improves their persistence in STEM and helps to validate their disciplinary identity.

Various UREs have been specifically designed to increase the number of historically underrepresented students who go on to become STEM majors and ultimately STEM professionals. While many UREs offer one or more supplemental opportunities to support students’ academic or social success, such as mentoring, tutoring, summer bridge programs, career or graduate school workshops, and research-oriented seminars, those designed for underrepresented students appear to emphasize such features as integral and integrated components of the program. In particular, studies of undergraduate research programs targeting underrepresented minority students have begun to document positive outcomes such as degree completion and persistence in interest in STEM careers ( Byars-Winston et al., 2015 ; Chemers et al., 2011 ; Jones et al., 2010 ; Nagda et al., 1998 ; Schultz et al., 2011 ). Most of these studies collected data on apprentice-style UREs, in which the undergraduate becomes a functioning member of a research group along with the graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, and mentor.

Recommendation 1: Researchers with expertise in education research should conduct well-designed studies in collaboration with URE program directors to improve the evidence base about the processes and effects of UREs. This research should address how the various components of UREs may benefit students. It should also include additional causal evidence for the individual and additive effects of outcomes from student participation in different types of UREs. Not all UREs need be designed to undertake this type of research, but it would be very useful to have some UREs that are designed to facilitate these efforts to improve the evidence base .

As the focus on UREs has grown, so have questions about their implementation. Many articles have been published describing specific UREs (see Chapter 2 ). Large amounts of research have also been undertaken to explore more generally how students learn, and the resulting body of evidence has led to the development and adoption of “active learning” strategies and experiences. If a student in a URE has an opportunity to, for example, analyze new data or to reformulate a hypothesis in light of the student’s analysis, this activity fits into the category that is described as active learning. Surveys of student participants and unpublished evaluations pro-

vide additional information about UREs but do not establish causation or determine the mechanism(s). Consequently, little is currently known about the mechanisms of precisely how UREs work and which aspects of UREs are most powerful. Important components that have been reported include student ownership of the URE project, time to tackle a question iteratively, and opportunities to report and defend one’s conclusions ( Hanauer and Dolan, 2014 ; Thiry et al., 2011 ).

There are many unanswered questions and opportunities for further research into the role and mechanism of UREs. Attention to research design as UREs are planned is important; more carefully designed studies are needed to understand the ways that UREs influence a student’s education and to evaluate the outcomes that have been reported for URE participants. Appropriate studies, which include matched samples or similar controls, would facilitate research on the ways that UREs benefit students, enabling both education researchers and implementers of UREs to determine optimal features for program design and giving the community a more robust understanding of how UREs work.

See the research agenda ( Chapter 7 ) for specific recommendations about research topics and approaches.

Recommendation 2: Funders should provide appropriate resources to support the design, implementation, and analysis of some URE programs that are specifically designed to enable detailed research establishing the effects on participant outcomes and on other variables of interest such as the consequences for mentors or institutions.

Not all UREs need to be the subject of extensive study. In many cases, a straightforward evaluation is adequate to determine whether the URE is meeting its goals. However, to achieve more widespread improvement in both the types and quality of the UREs offered in the future, additional evidence about the possible causal effects and mechanisms of action of UREs needs to be systematically collected and disseminated. This includes a better understanding of the implementation differences for a variety of institutions (e.g., community colleges, primarily undergraduate institutions, research universities) to ensure that the desired outcomes can translate across settings. Increasing the evidence about precisely how UREs work and which aspects of UREs are most powerful will require careful attention to study design during planning for the UREs.

Not all UREs need to be designed to achieve this goal; many can provide opportunities to students by relying on pre-existing knowledge and iterative improvement as that knowledge base grows. However, for the knowledge base to grow, funders must provide resources for some URE designers and social science researchers to undertake thoughtful and well-planned studies

on causal and mechanistic issues. This will maximize the chances for the creation and dissemination of information that can lead to the development of sustainable and effective UREs. These studies can result from a partnership formed as the URE is designed and funded, or evaluators and social scientists could identify promising and/or effective existing programs and then raise funds on their own to support the study of those programs to answer the questions of interest. In deciding upon the UREs that are chosen for these extensive studies, it will be important to consider whether, collectively, they are representative of UREs in general. For example, large and small UREs at large and small schools targeted at both introductory and advanced students and topics should be studied.

CONSTRUCTION OF URES

Conclusion 4: The committee was unable to find evidence that URE designers are taking full advantage of the information available in the education literature on strategies for designing, implementing, and evaluating learning experiences. STEM faculty members do not generally receive training in interpreting or conducting education research. Partnerships between those with expertise in education research and those with expertise in implementing UREs are one way to strengthen the application of evidence on what works in planning and implementing UREs.

As discussed in Chapters 3 and 4 , there is an extensive body of literature on pedagogy and how people learn; helping STEM faculty to access the existing literature and incorporate those concepts as they design UREs could improve student experiences. New studies that specifically focus on UREs may provide more targeted information that could be used to design, implement, sustain, or scale up UREs and facilitate iterative improvements. Information about the features of UREs that elicit particular outcomes or best serve certain populations of students should be considered when implementing a new instantiation of an existing model of a URE or improving upon an existing URE model.

Conclusion 5: Evaluations of UREs are often conducted to inform program providers and funders; however, they may not be accessible to others. While these evaluations are not designed to be research studies and often have small sample sizes, they may contain information that could be useful to those initiating new URE programs and those refining UREs. Increasing access to these evaluations and to the accumulated experience of the program providers may enable URE designers and implementers to build upon knowledge gained from earlier UREs.

As discussed in Chapter 1 , the committee searched for evaluations of URE programs in several different ways but was not able to locate many published evaluations to study. Although some evaluations were found in the literature, the committee could not determine a way to systematically examine the program evaluations that have been prepared. The National Science Foundation and other funders generally require grant recipients to submit evaluation data, but that information is not currently aggregated and shared publicly, even for programs that are using a common evaluation tool. 1

Therefore, while program evaluation likely serves a useful role in providing descriptive data about a program for the institutions and funders supporting the program, much of the summative evaluation work that has been done to date adds relatively little to the broader knowledge base and overall conversations around undergraduate research. Some of the challenges of evaluation include budget and sample size constraints.

Similarly, it is difficult for designers of UREs to benefit systematically from the work of others who have designed and run UREs in the past because of the lack of an easy and consistent mechanism for collecting, analyzing, and sharing data. If these evaluations were more accessible they might be beneficial to others designing and evaluating UREs by helping them to gather ideas and inspiration from the experiences of others. A few such stories are provided in this report, and others can be found among the many resources offered by the Council on Undergraduate Research 2 and on other websites such as CUREnet. 3

Recommendation 3: Designers of UREs should base their design decisions on sound evidence. Consultations with education and social science researchers may be helpful as designers analyze the literature and make decisions on the creation or improvement of UREs. Professional development materials should be created and made available to faculty. Educational and disciplinary societies should consider how they can provide resources and connections to those working on UREs.

Faculty and other organizers of UREs can use the expanding body of scholarship as they design or improve the programs and experiences offered to their students. URE designers will need to make decisions about how to adapt approaches reported in the literature to make the programs they develop more suitable to their own expertise, student population(s), and available resources. Disciplinary societies and other national groups, such as those focused on improving pedagogy, can play important roles in

___________________

1 Personal knowledge of Janet Branchaw, member of the Committee on Strengthening Research Experiences for Undergraduate STEM Students.

2 See www.cur.org [November 2016].

3 See ( curenet.cns.utexas.edu ) [November 2016].

bringing these issues to the forefront through events at their national and regional meetings and through publications in their journals and newsletters. They can develop repositories for various kinds of resources appropriate for their members who are designing and implementing UREs. The ability to travel to conferences and to access and discuss resources created by other individuals and groups is a crucial aspect of support (see Recommendations 7 and 8 for further discussion).

See Chapter 8 for specific questions to consider when one is designing or implementing UREs.

CURRENT OFFERINGS

Conclusion 6: Data at the institutional, state, or national levels on the number and type of UREs offered, or who participates in UREs overall or at specific types of institutions, have not been collected systematically. Although the committee found that some individual institutions track at least some of this type of information, we were unable to determine how common it is to do so or what specific information is most often gathered.

There is no one central database or repository that catalogs UREs at institutions of higher education, the nature of the research experiences they provide, or the relevant demographics (student, departmental, and institutional). The lack of comprehensive data makes it difficult to know how many students participate in UREs; where UREs are offered; and if there are gaps in access to UREs across different institutional types, disciplines, or groups of students. One of the challenges of describing the undergraduate research landscape is that students do not have to be enrolled in a formal program to have a research experience. Informal experiences, for example a work-study job, are typically not well documented. Another challenge is that some students participate in CUREs or other research experiences (such as internships) that are not necessarily labeled as such. Institutional administrators may be unaware of CUREs that are already part of their curriculum. (For example, establishment of CUREs may be under the purview of a faculty curriculum committee and may not be recognized as a distinct program.) Student participation in UREs may occur at their home institution or elsewhere during the summer. Therefore, it is very difficult for a science department, and likely any other STEM department, to know what percentage of their graduating majors have had a research experience, let alone to gather such information on students who left the major. 4

4 This point was made by Marco Molinaro, University of California, Davis, in a presentation to the Committee on Strengthening Research Experience for Undergraduate STEM Students, September 16, 2015.

Conclusion 7: While data are lacking on the precise number of students engaged in UREs, there is some evidence of a recent growth in course-based undergraduate research experiences (CUREs), which engage a cohort of students in a research project as part of a formal academic experience.

There has been an increase in the number of grants and the dollar amount spent on CUREs over the past decade (see Chapter 3 ). CUREs can be particularly useful in scaling UREs to reach a much larger population of students ( Bangera and Brownell, 2014 ). By using a familiar mechanism—enrollment in a course—a CURE can provide a more comfortable route for students unfamiliar with research to gain their first experience. CUREs also can provide such experiences to students with diverse backgrounds, especially if an institution or department mandates participation sometime during a student’s matriculation. Establishing CUREs may be more cost-effective at schools with little on-site research activity. However, designing a CURE is a new and time-consuming challenge for many faculty members. Connecting to nationally organized research networks can provide faculty with helpful resources for the development of a CURE based around their own research or a local community need, or these networks can link interested faculty to an ongoing collaborative project. Collaborative projects can provide shared curriculum, faculty professional development and community, and other advantages when starting or expanding a URE program. See the discussion in the report from a convocation on Integrating Discovery-based Research into the Undergraduate Curriculum ( National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2015 ).

Recommendation 4: Institutions should collect data on student participation in UREs to inform their planning and to look for opportunities to improve quality and access.

Better tracking of student participation could lead to better assessment of outcomes and improved quality of experience. Such metrics could be useful for both prospective students and campus planners. An integrated institutional system for research opportunities could facilitate the creation of tiered research experiences that allow students to progress in skills and responsibility and create support structures for students, providing, for example, seminars in communications, safety, and ethics for undergraduate researchers. Institutions could also use these data to measure the impact of UREs on student outcomes, such as student success rates in introductory courses, retention in STEM degree programs, and completion of STEM degrees.

While individual institutions may choose to collect additional information depending on their goals and resources, relevant student demographics

and the following design elements would provide baseline data. At a minimum, such data should include

- Type of URE;

- Each student’s discipline;

- Duration of the experience;

- Hours spent per week;

- When the student began the URE (e.g., first year, capstone);

- Compensation status (e.g., paid, unpaid, credit); and

- Location and format (e.g., on home campus, on another campus, internship, co-op).

National aggregation of some of the student participation variables collected by various campuses might be considered by funders. The existing Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System database, organized by the National Center for Education Statistics at the U.S. Department of Education, may be a suitable repository for certain aspects of this information.

Recommendation 5: Administrators and faculty at all types of colleges and universities should continually and holistically evaluate the range of UREs that they offer. As part of this process, institutions should:

- Consider how best to leverage available resources (including off-campus experiences available to students and current or potential networks or partnerships that the institution may form) when offering UREs so that they align with their institution’s mission and priorities;

- Consider whether current UREs are both accessible and welcoming to students from various subpopulations across campus (e.g., historically underrepresented students, first generation college students, those with disabilities, non-STEM majors, prospective kindergarten-through-12th-grade teachers); and

- Gather and analyze data on the types of UREs offered and the students who participate, making this information widely available to the campus community and using it to make evidence-based decisions about improving opportunities for URE participation. This may entail devising or implementing systems for tracking relevant data (see Conclusion 4 ).

Resources available for starting, maintaining, and expanding UREs vary from campus to campus. At some campuses, UREs are a central focus and many resources are devoted to them. At other institutions—for example, many community colleges—UREs are seen as extra, and new resources may be required to ensure availability of courses and facilities. Resource-