An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

In Spring 2021, the National Library of Medicine (NLM) PubMed® Special Query on this page will no longer be curated by NLM. If you have questions, please contact NLM Customer Support at https://support.nlm.nih.gov/

This chart lists the major biomedical research reporting guidelines that provide advice for reporting research methods and findings. They usually "specify a minimum set of items required for a clear and transparent account of what was done and what was found in a research study, reflecting, in particular, issues that might introduce bias into the research" (Adapted from the EQUATOR Network Resource Centre ). The chart also includes editorial style guides for writing research reports or other publications.

See the details of the search strategy. More research reporting guidelines are at the EQUATOR Network Resource Centre .

Last Reviewed: April 14, 2023

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- Collections Home

- About Collections

- Browse Collections

- Calls for Papers

Reporting Guidelines

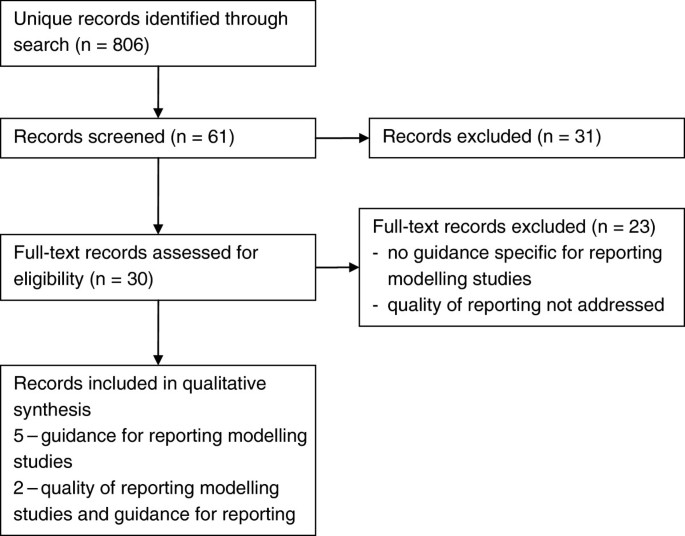

Reporting guidelines are statements intended to advise authors reporting research methods and findings. They can be presented as a checklist, flow diagram or text, and describe what is required to give a clear and transparent account of a study's research and results. These guidelines are prepared through consideration of specific issues that may introduce bias, and are supported by the latest evidence in the field. The Reporting Guidelines Collection highlights articles published across PLOS journals and includes guidelines and guidance, commentary, and related research on guidelines. This collection features some of the many resources available to facilitate the rigorous reporting of scientific studies, and to improve the presentation and evaluation of published studies.

Image Credit: CCAC North Library, Flickr

- From the Blogs

- Observational & Epidemiological Research

- Randomized Controlled Trials

- Systematic Reviews & Meta-Analyses

- Diagnostic & Prognostic Research

- Animal & Cell Models

- General Guidance

- Image credit CCAC North Library, Flickr.com Speaking of Medicine Maximizing the Impact of Research: New Reporting Guidelines Collection from PLOS – Speaking of Medicine September 3, 2013 Amy Ross, Laureen Connell

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001885 PLOS Medicine The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) Statement October 6, 2015 Eric I. Benchimol, Liam Smeeth, Astrid Guttmann, Katie Harron, David Moher, Irene Petersen, Henrik T. Sørensen, Erik von Elm, Sinéad M. Langan, RECORD Working Committee

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040297 PLOS Medicine Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and Elaboration October 16, 2007 Jan P Vandenbroucke, Erik von Elm, Douglas G Altman, Peter C Gøtzsche, Cynthia D Mulrow, Stuart J Pocock, Charles Poole, James J Schlesselman, Matthias Egger, for the STROBE Initiative

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040296 PLOS Medicine The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies October 16, 2007 Erik von Elm, Douglas G Altman, Matthias Egger, Stuart J Pocock, Peter C Gøtzsche, Jan P Vandenbroucke, for the STROBE Initiative

- Image credit PLOS PLOS Medicine Reporting Guidelines for Survey Research: An Analysis of Published Guidance and Reporting Practices August 2, 2011 Carol Bennett, Sara Khangura, Jamie Brehaut, Ian Graham, David Moher, Beth Potter, Jeremy Grimshaw

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pone.0064733 PLOS ONE Impact of STROBE Statement Publication on Quality of Observational Study Reporting: Interrupted Time Series versus Before-After Analysis August 26, 2013 Sylvie Bastuji-Garin, Emilie Sbidian, Caroline Gaudy-Marqueste, Emilie Ferrat, Jean-Claude Roujeau, Marie-Aleth Richard, Florence Canoui-Poitrine

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pone.0094412 PLOS ONE The Reporting of Observational Clinical Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Studies: A Systematic Review April 22, 2014 Qing Guo, Melissa Parlar, Wanda Truong, Geoffrey Hall, Lehana Thabane, Margaret McKinnon, Ron Goeree, Eleanor Pullenayegum

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pone.0101176 PLOS ONE A Review of Published Analyses of Case-Cohort Studies and Recommendations for Future Reporting June 27, 2014 Stephen Sharp, Manon Poulaliou, Simon Thompson, Ian White, Angela Wood

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pone.0103360 PLOS ONE Outlier Removal and the Relation with Reporting Errors and Quality of Psychological Research July 29, 2014 Marjan Bakker, Jelte Wicherts

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000022 PLOS Medicine STrengthening the REporting of Genetic Association Studies (STREGA)— An Extension of the STROBE Statement February 3, 2009 Julian Little, Julian P.T Higgins, John P.A Ioannidis, David Moher, France Gagnon, Erik von Elm, Muin J Khoury, Barbara Cohen, George Davey-Smith, Jeremy Grimshaw, Paul Scheet, Marta Gwinn, Robin E Williamson, Guang Yong Zou, Kim Hutchings, Candice Y Johnson, Valerie Tait, Miriam Wiens, Jean Golding, Cornelia van Duijn, John McLaughlin, Andrew Paterson, George Wells, Isabel Fortier, Matthew Freedman, Maja Zecevic, Richard King, Claire Infante-Rivard, Alex Stewart, Nick Birkett

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001117 PLOS Medicine STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology – Molecular Epidemiology (STROBE-ME): An Extension of the STROBE Statement October 25, 2011 Valentina Gallo, Matthias Egger, Valerie McCormack, Peter Farmer, John Ioannidis, Micheline Kirsch-Volders, Giuseppe Matullo, David Phillips, Bernadette Schoket, Ulf Strömberg, Roel Vermeulen, Christopher Wild, Miquel Porta, Paolo Vineis

- Image credit PLOS PLOS Medicine Observational Studies: Getting Clear about Transparency August 26, 2014 The PLoS Medicine Editors

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050020 PLOS Medicine CONSORT for Reporting Randomized Controlled Trials in Journal and Conference Abstracts: Explanation and Elaboration January 22, 2008 Sally Hopewell, Mike Clarke, David Moher, Elizabeth Wager, Philippa Middleton, Douglas G Altman, Kenneth F Schulz, and the CONSORT Group

- Image credit PLOS PLOS ONE Endorsement of the CONSORT Statement by High-Impact Medical Journals in China: A Survey of Instructions for Authors and Published Papers February 13, 2012 Xiao-qian Li, Kun-ming Tao, Qinghui Zhou, David Moher, Hong-yun Chen, Fu-zhe Wang, Chang-quan Ling

- Image credit PLOS PLOS ONE Assessing the Quality of Reports about Randomized Controlled Trials of Acupuncture Treatment on Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy July 2, 2012 Chen Bo, Zhao Xue, Guo Yi, Chen Zelin, Bai Yang, Wang Zixu, Wang Yajun

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pone.0065442 PLOS ONE Reporting Quality of Social and Psychological Intervention Trials: A Systematic Review of Reporting Guidelines and Trial Publications May 29, 2013 Sean Grant, Evan Mayo-Wilson, G. J. Melendez-Torres, Paul Montgomery

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pone.0084779 PLOS ONE Are Reports of Randomized Controlled Trials Improving over Time? A Systematic Review of 284 Articles Published in High-Impact General and Specialized Medical Journals December 31, 2013 Matthew To, Jennifer Jones, Mohamed Emara, Alejandro Jadad

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pone.0086360 PLOS ONE Assessment of the Reporting Quality of Randomized Controlled Trials on Treatment of Coronary Heart Disease with Traditional Chinese Medicine from the Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine: A Systematic Review January 28, 2014 Fan Fang, Xu Qin, Sun Qi, Zhao Jun, Wang Ping, Guo Rui

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001666 PLOS Medicine Evidence for the Selective Reporting of Analyses and Discrepancies in Clinical Trials: A Systematic Review of Cohort Studies of Clinical Trials June 24, 2014 Kerry Dwan, Douglas Altman, Mike Clarke, Carrol Gamble, Julian Higgins, Jonathan Sterne, Paula Williamson, Jamie Kirkham

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pone.0110229 PLOS ONE Systematic Evaluation of the Patient-Reported Outcome (PRO) Content of Clinical Trial Protocols October 15, 2014 Derek Kyte, Helen Duffy, Benjamin Fletcher, Adrian Gheorghe, Rebecca Mercieca-Bebber, Madeleine King, Heather Draper, Jonathan Ives, Michael Brundage, Jane Blazeby, Melanie Calvert

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pone.0110216 PLOS ONE Patient-Reported Outcome (PRO) Assessment in Clinical Trials: A Systematic Review of Guidance for Trial Protocol Writers October 15, 2014 Melanie Calvert, Derek Kyte, Helen Duffy, Adrian Gheorghe, Rebecca Mercieca-Bebber, Jonathan Ives, Heather Draper, Michael Brundage, Jane Blazeby, Madeleine King

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000261 PLOS Medicine Revised STandards for Reporting Interventions in Clinical Trials of Acupuncture (STRICTA): Extending the CONSORT Statement June 8, 2010 Hugh MacPherson, Douglas G. Altman, Richard Hammerschlag, Li Youping, Wu Taixiang, Adrian White, David Moher, on behalf of the STRICTA Revision Group

- Image credit PLOS PLOS Medicine Comparative Effectiveness Research: Challenges for Medical Journals April 27, 2010 Harold C. Sox, Mark Helfand, Jeremy Grimshaw, Kay Dickersin, the PLoS Medicine Editors , David Tovey, J. André Knottnerus, Peter Tugwell

- Image credit PLOS PLOS Medicine Reporting of Systematic Reviews: The Challenge of Genetic Association Studies June 26, 2007 Muin J Khoury, Julian Little, Julian Higgins, John P. A Ioannidis, Marta Gwinn

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040078 PLOS Medicine Epidemiology and Reporting Characteristics of Systematic Reviews March 27, 2007 David Moher, Jennifer Tetzlaff, Andrea C Tricco, Margaret Sampson, Douglas G Altman

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pone.0027611 PLOS ONE From QUOROM to PRISMA: A Survey of High-Impact Medical Journals’ Instructions to Authors and a Review of Systematic Reviews in Anesthesia Literature November 16, 2011 Kun-ming Tao, Xiao-qian Li, Qing-hui Zhou, David Moher, Chang-quan Ling, weifeng yu

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pone.0075122 PLOS ONE Testing the PRISMA-Equity 2012 Reporting Guideline: the Perspectives of Systematic Review Authors October 10, 2013 Belinda Burford, Vivian Welch, Elizabeth Waters, Peter Tugwell, David Moher, Jennifer O'Neill, Tracey Koehlmoos, Mark Petticrew

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pone.0092508 PLOS ONE The Quality of Reporting Methods and Results in Network Meta-Analyses: An Overview of Reviews and Suggestions for Improvement March 26, 2014 Brian Hutton, Georgia Salanti, Anna Chaimani, Deborah Caldwell, Chris Schmid, Kristian Thorlund, Edward Mills, Lucy Turner, Ferran Catala-Lopez, Doug Altman, David Moher

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pone.0096407 PLOS ONE Blinded by PRISMA: Are Systematic Reviewers Focusing on PRISMA and Ignoring Other Guidelines? May 1, 2014 Padhraig Fleming, Despina Koletsi, Nikolaos Pandis

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 PLOS Medicine Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement July 21, 2009 David Moher, Alessandro Liberati, Jennifer Tetzlaff, Douglas G. Altman, The PRISMA Group

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001333 PLOS Medicine PRISMA-Equity 2012 Extension: Reporting Guidelines for Systematic Reviews with a Focus on Health Equity October 30, 2012 Vivian Welch, Mark Petticrew, Peter Tugwell, David Moher, Jennifer O'Neill, Elizabeth Waters, Howard White

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001419 PLOS Medicine PRISMA for Abstracts: Reporting Systematic Reviews in Journal and Conference Abstracts April 9, 2013 Elaine Beller, Paul Glasziou, Douglas Altman, Sally Hopewell, Hilda Bastian, Iain Chalmers, Peter Gotzsche, Toby Lasserson, David Tovey

- Image credit PLOS PLOS Medicine Many Reviews Are Systematic but Some Are More Transparent and Completely Reported than Others March 27, 2007 The PLoS Medicine Editors

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100 PLOS Medicine The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration July 21, 2009 Alessandro Liberati, Douglas G. Altman, Jennifer Tetzlaff, Cynthia Mulrow, Peter C. Gøtzsche, John P. A. Ioannidis, Mike Clarke, P. J. Devereaux, Jos Kleijnen, David Moher

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pone.0007753 PLOS ONE Quality and Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies in TB, HIV and Malaria: Evaluation Using QUADAS and STARD Standards November 13, 2009 Patricia Scolari Fontela, Nitika Pant Pai, Ian Schiller, Nandini Dendukuri, Andrew Ramsay, Madhukar Pai

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001531 PLOS Medicine Use of Expert Panels to Define the Reference Standard in Diagnostic Research: A Systematic Review of Published Methods and Reporting October 15, 2013 Loes Bertens, Berna Broekhuizen, Christiana Naaktgeboren, Frans Rutten, Arno Hoes, Yvonne van Mourik, Karel Moons, Johannes Reitsma

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pone.0085908 PLOS ONE The Assessment of the Quality of Reporting of Systematic Reviews/Meta-Analyses in Diagnostic Tests Published by Authors in China January 21, 2014 Long Ge, Jian-cheng Wang, Jin-long Li, Li Liang, Ni An, Xin-tong Shi, Yin-chun Liu, JH Tian

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000420 PLOS Medicine Strengthening the Reporting of Genetic Risk Prediction Studies: The GRIPS Statement March 15, 2011 A. Cecile J. W. Janssens, John P. A. Ioannidis, Cornelia M. van Duijn, Julian Little, Muin J. Khoury, for the GRIPS Group

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001216 PLOS Medicine Reporting Recommendations for Tumor Marker Prognostic Studies (REMARK): Explanation and Elaboration May 29, 2012 Doug Altman, Lisa McShane, Willi Sauerbrei, Sheila Taube

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001381 PLOS Medicine Prognosis Research Strategy (PROGRESS) 3: Prognostic Model Research February 5, 2013 Ewout Steyerberg, Karel Moons, Danielle van der Windt, Jill Hayden, Pablo Perel, Sara Schroter, Richard Riley, Harry Hemingway, Douglas Altman

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001380 PLOS Medicine Prognosis Research Strategy (PROGRESS) 2: Prognostic Factor Research February 5, 2013 Richard Riley, Jill Hayden, Ewout Steyerberg, Karel Moons, Keith Abrams, Panayiotis Kyzas, Nuria Malats, Andrew Briggs, Sara Schroter, Douglas Altman, Harry Hemingway

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001671 PLOS Medicine Improving the Transparency of Prognosis Research: The Role of Reporting, Data Sharing, Registration, and Protocols July 8, 2014 George Peat, Richard Riley, Peter Croft, Katherine Morley, Panayiotis Kyzas, Karel Moons, Pablo Perel, Ewout Steyerberg, Sara Schroter, Douglas Altman, Harry Hemingway

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pone.0007824 PLOS ONE Survey of the Quality of Experimental Design, Statistical Analysis and Reporting of Research Using Animals November 30, 2009 Carol Kilkenny, Nick Parsons, Ed Kadyszewski, Michael F. W. Festing, Innes C. Cuthill, Derek Fry, Jane Hutton, Douglas G. Altman

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001489 PLOS Medicine Threats to Validity in the Design and Conduct of Preclinical Efficacy Studies: A Systematic Review of Guidelines for In Vivo Animal Experiments July 23, 2013 Valerie Henderson, Jonathan Kimmelman, Dean Fergusson, Jeremy Grimshaw, Dan Hackam

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pone.0088266 PLOS ONE Five Years MIQE Guidelines: The Case of the Arabian Countries February 4, 2014 Afif Abdel Nour, Esam Azhar, Ghazi Damanhouri, Stephen Bustin

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pone.0101131 PLOS ONE The Quality of Methods Reporting in Parasitology Experiments July 30, 2014 Oscar Flórez-Vargas, Michael Bramhall, Harry Noyes, Sheena Cruickshank, Robert Stevens, Andy Brass

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000412 PLOS Biology Improving Bioscience Research Reporting: The ARRIVE Guidelines for Reporting Animal Research June 29, 2010 Carol Kilkenny, William J. Browne, Innes C. Cuthill, Michael Emerson, Douglas G. Altman

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001481 PLOS Biology Whole Animal Experiments Should Be More Like Human Randomized Controlled Trials February 12, 2013 Beverly Muhlhausler, Frank Bloomfield, Matthew Gillman

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001756 PLOS Biology Two Years Later: Journals Are Not Yet Enforcing the ARRIVE Guidelines on Reporting Standards for Pre-Clinical Animal Studies January 7, 2014 David Baker, Katie Lidster, Ana Sottomayor, Sandra Amor

- Image credit PLOS PLOS Biology Reporting Animal Studies: Good Science and a Duty of Care June 29, 2010 Catriona J. MacCallum

- Image credit PLOS PLOS Biology Open Science and Reporting Animal Studies: Who’s Accountable? January 7, 2014 Catriona MacCallum, Jonathan Eisen, Emma Ganley

- Image credit PLOS PLOS Computational Biology Minimum Information About a Simulation Experiment (MIASE) April 28, 2011 Dagmar Waltemath, Richard Adams, Daniel A. Beard, Frank T. Bergmann, Upinder S. Bhalla, Randall Britten, Vijayalakshmi Chelliah, Michael T. Cooling, Jonathan Cooper, Edmund J. Crampin, Alan Garny, Stefan Hoops, Michael Hucka, Peter Hunter, Edda Klipp, Camille Laibe, Andrew K. Miller, Ion Moraru, David Nickerson, Poul Nielsen, Macha Nikolski, Sven Sahle, Herbert M. Sauro, Henning Schmidt, Jacky L. Snoep, Dominic Tolle, Olaf Wolkenhauer, Nicolas Le Novère

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050139 PLOS Medicine Guidelines for Reporting Health Research: The EQUATOR Network’s Survey of Guideline Authors June 24, 2008 Iveta Simera, Douglas G Altman, David Moher, Kenneth F Schulz, John Hoey

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000217 PLOS Medicine Guidance for Developers of Health Research Reporting Guidelines February 16, 2010 David Moher, Kenneth F. Schulz, Iveta Simera, Douglas G. Altman

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pone.0035621 PLOS ONE Are Peer Reviewers Encouraged to Use Reporting Guidelines? A Survey of 116 Health Research Journals April 27, 2012 Allison Hirst, Douglas Altman

- Image credit PLOS PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases Research Ethics and Reporting Standards at PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases October 31, 2007 Gavin Yamey

- Image credit PLOS PLOS Medicine Better Reporting, Better Research: Guidelines and Guidance in PLoS Medicine April 29, 2008 The PLoS Medicine Editors

- Image credit CCAC North Library, Flickr.com PLOS Medicine Better Reporting of Scientific Studies: Why It Matters August 27, 2013 The PLoS Medicine Editors

- Image credit 10.1371/journal.pone.0097492 PLOS ONE Do Editorial Policies Support Ethical Research? A Thematic Text Analysis of Author Instructions in Psychiatry Journals June 5, 2014 Daniel Strech, Courtney Metz, Hannes Knüppel

Reporting Guidelines

It is important that your manuscript gives a clear and complete account of the research that you have done. Well reported research is more useful and complete reporting allows editors, peer reviewers and readers to understand what you did and how.

Poorly reported research can distort the literature, and leads to research that cannot be replicated or used in future meta-analyses or systematic reviews.

You should make sure that you manuscript is written in a way that the reader knows exactly what you did and could repeat your study if they wanted to with no additional information. It is particularly important that you give enough information in the methods section of your manuscript.

To help with reporting your research, there are reporting guidelines available for many different study designs. These contain a checklist of minimum points that you should cover in your manuscript. You should use these guidelines when you are preparing and writing your manuscript, and you may be required to provide a completed version of the checklist when you submit your manuscript.

The EQUATOR (Enhancing the Quality and Transparency Of health Research) Network is an international initiative that aims to improve the quality of research publications. It provides a comprehensive list of reporting guidelines and other material to help improve reporting.

A list full of all of the reporting guidelines endorsed by the EQUATOR Network can be found here . Some of the reporting guidelines for common study designs are:

- Randomized controlled trials – CONSORT

- Systematic reviews – PRISMA

- Observational studies – STROBE

- Case reports – CARE

- Qualitative research – COREQ

- Pre-clinical animal studies – ARRIVE

Peer reviewers may be asked to use these checklists when assessing your manuscript. If you follow these guidelines, editors and peer reviewers will be able to assess your manuscript better as they will more easily understand what you did. It may also mean that they ask you for fewer revisions.

Featured Clinical Reviews

- Screening for Atrial Fibrillation: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement JAMA Recommendation Statement January 25, 2022

- Evaluating the Patient With a Pulmonary Nodule: A Review JAMA Review January 18, 2022

Select Your Interests

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

Updated Guidance on the Reporting of Race and Ethnicity in Medical and Science Journals

- 1 Executive Managing Editor, JAMA and the JAMA Network, Chicago, Illinois

- 2 Deputy Managing Editor, JAMA Network, Chicago, Illinois

- 3 Managing Editor, JAMA , Chicago, Illinois

- Editorial The Reporting of Race and Ethnicity in Medical and Science Journals Annette Flanagin, RN, MA; Tracy Frey, BA; Stacy L. Christiansen, MA; Howard Bauchner, MD JAMA

- Editorial Guidance on Race, Ethnicity, and Origin as Proxies for Genetic Ancestry in Biomedical Publication W. Gregory Feero, MD, PhD; Robert D. Steiner, MD; Anne Slavotinek, MBBS, PhD; Tiago Faial, PhD; Michael J. Bamshad, MD; Jehannine Austin, PhD, CGC; Bruce R. Korf, MD, PhD; Annette Flanagin, RN, MA; Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, PhD, MD, MAS JAMA

The goal of this guidance is to provide recommendations and suggestions that encourage fairness, equity, consistency, and clarity in use and reporting of race and ethnicity in medical and science journals. As previously summarized, “terminology, usage, and word choice are critically important, especially when describing people and when discussing race and ethnicity. Inclusive language supports diversity and conveys respect. Language that imparts bias toward or against persons or groups based on characteristics or demographics must be avoided.” 1

With the publication of an earlier version of this guidance, 1 comments were invited, and helpful assessments and comments were received from numerous reviewers, scholars, and researchers, who provided valuable feedback and represented diverse expertise and opinions. After thorough review of these comments (some of which did not agree with others) and additional research and discussion, the guidance was revised and updated, and additional formal review was obtained. In this Editorial, we present the updated guidance, and we sincerely thank the many reviewers for their contributions, each of whom are listed in the Acknowledgment at the end of this article.

This guidance continues to acknowledge that race and ethnicity are social constructs as well as the important sensitivities and controversies related to use of these terms and associated nomenclature in medical and health research, education, and practice. Thus, for content published in medical journals, language and terminology must be accurate, clear, and precise, and must reflect fairness, equity, and consistency in use and reporting of race and ethnicity. The guidance also acknowledges that the reporting of race and ethnicity should not be considered in isolation and should be accompanied by reporting of other sociodemographic factors and social determinants, including concerns about racism, disparities, and inequities, and the intersectionality of race and ethnicity with these other factors.

The guidance defines commonly used terms associated with race and ethnicity and acknowledges that these terms and definitions have changed, that some are out of date, and that the nomenclature will continue to evolve. Other topics addressed include relevant concerns and controversies in health care and research, including the intersectionality of ancestry and heritage, social determinants of health, and other socioeconomic, structural, institutional, cultural, and demographic factors; reporting of race and ethnicity in research articles; use of racial and ethnic collective or umbrella terms, capitalization, and abbreviations; listing racial and ethnic categories in alphabetical order vs order by majority; adjectival vs noun usage for categories of race and ethnicity; geographic origin and regionalization considerations; and brief guidance for journals and publishers that collect demographic data on editors, authors, and peer reviewers. Examples are provided to help guide authors and editors.

This updated guidance on reporting race and ethnicity is being added to the Inclusive Language section of the AMA Manual of Style: A Guide for Authors and Editors as subsection 11.2.3, Race and Ethnicity (see below). 2 This section of the Correct and Preferred Usage chapter of the style manual also includes subsections that address reporting concerns and preferred nomenclature for sex and gender, sexual orientation, age, socioeconomic status, and persons with diseases, disorders, or disabilities. Each of these subsections also will be reviewed and updated.

With this publication, this guidance will be freely available on the JAMA website and in the AMA Manual of Style , 2 and linked from the JAMA Network journals’ Instructions for Authors. Others are welcome to use and cite this guidance.

This guidance is not intended to be final but is presented with the understanding that monitoring will continue, and further updates will be provided as needed. Continual review of the terms and language used in the reporting of race and ethnicity is critically important as societal norms continue to evolve.

Section 11.12.3. Race and Ethnicity

Race and ethnicity are social constructs, without scientific or biological meaning. The indistinct construct of racial and ethnic categories has been increasingly acknowledged, and concerns about use of these terms in medical and health research, education, and practice have been progressively recognized. Accordingly, for content published in medical and science journals, language and terminology must be accurate, clear, and precise and must reflect fairness, equity, and consistency in use and reporting of race and ethnicity. (Note: historically, although inappropriately, race may have been considered a biological construct; thus, older content may characterize race as having biological significance.)

One of the goals of this guidance is to encourage the use of language to reduce unintentional bias in medical and science literature. The reporting of race and ethnicity should not be considered in isolation but should be accompanied by reporting of other sociodemographic factors and social determinants, including concerns about racism, disparities, and inequities, and the intersectionality of race and ethnicity with these other factors.

When reporting the results of research that includes racial and ethnic disparities and inequities, authors are encouraged to provide a balanced, evidence-based discussion of the implications of the findings for addressing institutional racism and structural racism as these affect the study population, disease or disorder studied, and the relevant health care systems. For example, Introduction and Discussion sections of manuscripts could include implications of historical injustices when describing the differences observed by race and ethnicity. Such discussion of implications can use specific words, such as racism , structural racism , racial equity , or racial inequity , when appropriate.

Definitions

The definitions provided herein focus on reporting race and ethnicity. Definitions of broader terms (eg, disparity, inequity, intersectionality, and others) will be included in the overarching Inclusive Language section that contains this subsection.

“Race and ethnicity are dynamic, shaped by geographic, cultural, and sociopolitical forces.” 3 Race and ethnicity are social constructs and with limited utility in understanding medical research, practice, and policy. However, the terms may be useful as a lens through which to study and view racism and disparities and inequities in health, health care, and medical practice, education, and research. 3 - 5 Terms and categories used to define and describe race and ethnicity have changed with time based on sociocultural shifts and greater awareness of the role of racism in society. This guidance is presented with that understanding, and updates have been and will continue to be provided as needed.

The terms race (first usage dating back to the 1500s) and ethnicity (first usage dating back to the late 1700s) 6 have changed and continue to evolve semantically. The Oxford English Dictionary currently defines race as “a group of people connected by common descent or origin” or “any of the (putative) major groupings of mankind, usually defined in terms of distinct physical features or shared ethnicity” and ethnicity as “membership of a group regarded as ultimately of common descent, or having a common national or cultural tradition.” 7 For example, in the US, ethnicity has referred to Hispanic or Latino, Latina, or Latinx people. Outside of the US, other terms of ethnicity may apply within specific nations or ancestry groups. As noted in a lexicographer’s post on the Conscious Style Guide , race and ethnicity are difficult to untangle. 6 In general, ethnicity has historically referred to a person’s cultural identity (eg, language, customs, religion) and race to broad categories of people that are divided arbitrarily but based on ancestral origin and physical characteristics. 6 Definitions that rely on external determinations of physical characteristics are problematic and may perpetuate racism. In addition, there is concern about whether these and other definitions are appropriate or out-of-date 8 and whether separation of subcategories of race from subcategories of ethnicity could be discriminatory, especially when used by governmental agencies and institutions to guide policy, funding allocations, budgets, and data-driven business and research decisions. 9 Thus, proposals have been made that these terms be unified into an aggregate, mutually exclusive set of categories as in “race and ethnicity.” 10 (See Additional Guidance for Use of Racial and Ethnic Collective Terms.)

The term ancestry refers to a person’s country or region of origin or an individual’s lineage of descent. Another characteristic of many populations is genetic admixture , which refers to genetic exchange among people from different ancestries and may correlate with an individual’s risk for certain genetic diseases. 3 Ancestry and genetic admixture may provide more useful information about health, population health, and genetic variants and risk for disease or disorders than do racial and ethnic categories. 3

Although race and ethnicity have no biological meaning, the terms have important, albeit contested, social meanings. Neglecting to report race and ethnicity in health and medical research disregards the reality of social stratification, injustices, and inequities and implications for population health, 3 , 4 and removing race and ethnicity from research may conceal health disparities. Thus, inclusion of race and ethnicity in reports of medical research to address and further elucidate health disparities and inequities remains important at this time.

According to the “Health Equity Style Guide for the COVID-19 Response: Principles and Preferred Terms for Non-Stigmatizing, Bias-Free Language” of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), racism is defined as a “system of structuring opportunity and assigning value based on the social interpretation of how one looks...(“race”), that unfairly disadvantages some individuals and communities, unfairly advantages other individuals and communities, and undermines realization of the full potential of our whole society through the waste of human resources.” 11 Note that racism and prejudice can occur without phenotypic discrimination.

Jones 12 and the CDC style guide 11 have defined 3 levels of racism.

Systemic, institutionalized, and structural racism : “Structures, policies, practices, and norms resulting in differential access to the goods, services, and opportunities of society by ‘race’ (eg, how major systems—the economy, politics, education, criminal justice, health, etc—perpetuate unfair advantage).” 11 The Associated Press (AP) Stylebook advises to not shorten these terms to “racism,” to avoid confusion with the other definitions. 13

Interpersonal and personally mediated racism : “Prejudice and discrimination, where prejudice is differential assumptions about the abilities, motives, and intents of others by ‘race,’ and discrimination is differential actions towards others by ‘race.’ These can be either intentional or unintentional.” 11

Internalized racism : “Acceptance by members of the stigmatized ‘races’ of negative messages about their own abilities and intrinsic worth.” 11

Concerns, Sensitivities, and Controversies in Health Care and Research

There are many examples of reported associations between race and ethnicity and health outcomes, but these outcomes may also be intertwined with ancestry and heritage, social determinants of health, as well as socioeconomic, structural, institutional, cultural, demographic, or other factors. 3 , 4 , 14 Thus, discerning the roles of these factors is difficult. For example, a person’s ancestral heritage may convey certain health-related predispositions (eg, cystic fibrosis in persons of Northern European descent and sickle cell disease reported among people whose ancestors were from sub-Saharan Africa, India, Saudi Arabia, and Mediterranean countries); however, such perceptions have resulted in underdiagnosis of these conditions in other populations. 15

Also, certain groups may bear a disproportionate burden of disease compared with other groups, but this may reflect individual and systemic disparities and inequities in health care and social determinants of health. For example, according to the US National Cancer Institute, the rates of cervical cancer are higher among Hispanic/Latina women and Black/African American women than among women of other racial or ethnic groups, with Black/African American women having the highest rates of death from the disease, but social determinants of health and inequities are also associated with a high prevalence of cervical cancer among these women. 16 The American Heart Association summarizes similar disparities in cardiovascular disease among Black individuals in the US compared with those from other racial and ethnic groups. 17

Identifying the race or ethnicity of a person or group of participants, along with other sociodemographic variables, may provide information about participants included in a study and the potential generalizability of the results of a study and may identify important disparities and inequities. Researchers should aim for inclusivity by providing comprehensive categories and subcategories where applicable. Many people may identify with more than 1 race and ethnicity; therefore, categories should not be considered absolute or viewed in isolation.

However, there is concern about the use of race in clinical algorithms and some health-based risk scores and databases because of inapplicability to some groups and the potential for discrimination and inappropriate clinical decisions. For example, the use of race to estimate glomerular filtration rates among Black adults has become controversial for several reasons. 18 - 21 Oversimplification of racial dichotomies can be harmful, such as in calculating kidney function, especially with racial inequities in kidney care. In this context, health inequities among populations should be addressed rather than focusing solely on differences in racial categories (eg, Black vs White adults with kidney disease). 21 Another example is the Framingham Risk Score, which was originally developed from a cohort of White, middle-class participants in the US included in the Framingham Heart Study and may not accurately estimate risk in other racial and ethnic populations. Similar concerns have been raised about genetic risk studies based on specific populations or that do not include participants from other groups (eg, a genome-wide association study that reports a genetic association with a specific disease or disorder based solely on a population of European descent). 22 Use caution in interpreting or generalizing findings from studies of risk based on populations of individuals representing specific or limited racial and ethnic categories.

Guidance for Reporting Race and Ethnicity in Research Articles

The JAMA Network journals include the following guidance for reporting race and ethnicity and other demographic information in research articles in the Instructions for Authors. 23

Demographic Information

Aggregate, deidentified demographic information (eg, age, sex, race and ethnicity, and socioeconomic indicators) should be reported for research reports along with all prespecified outcomes. Demographic variables collected for a specific study should be indicated in the Methods section. Demographic information assessed should be reported in the Results section, either in the main article or in an online supplement or both. If any demographic characteristics that were collected are not reported, the reason should be stated. Summary demographic information (eg, baseline characteristics of study participants) should be reported in the first line of the Results section of the Abstract.

With regard to the collection and reporting of demographic data on race and ethnicity:

The Methods section should include an explanation of who identified participant race and ethnicity and the source of the classifications used (eg, self-report or selection, investigator observed, database, electronic health record, survey instrument).

If race and ethnicity categories were collected for a study, the reasons that these were assessed also should be described in the Methods section. If collection of data on race and ethnicity was required by the funding agency, that should be noted.

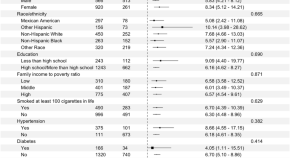

Specific racial and ethnic categories are preferred over collective terms, when possible. Authors should report the specific categories used in their studies and recognize that these categories will differ based on the databases or surveys used, the requirements of funders, and the geographic location of data collection or study participants. Categories included in groups labeled as “other” should be defined.

Categories should be listed in alphabetical order in text and tables.

Race and ethnicity categories of the study population should be reported in the Results section.

Reporting race and ethnicity in this study was mandated by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), consistent with the Inclusion of Women, Minorities, and Children policy. Individuals participating in the poststudy survey were categorized as American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, or White based on the NIH Policy on Reporting Race and Ethnicity Data. Children’s race and ethnicity were based on the parents’ report. Race was self-reported by study participants, and race categories (Black and White) were defined by investigators based on the US Office of Management and Budget’s Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity. Given that racial residential segregation is distinctively experienced by Black individuals in the US, the analytical sample was restricted to participants who self-identified as Black. In this genome-wide association study, participants were from 8 African countries (ie, Kenya, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, South Africa, Sudan, Uganda, and Zambia). Any Black African group from any of the 8 African countries (mostly of Bantu descent) was included in the Black African cohort. The South African group composed primarily of multiple racial categories, comprising any admixture combination of individuals of European, Southeast Asian, South Asian, Bantu-speaking African, and/or indigenous Southern African hunter-gatherer ancestries (Khoikhoi, San, or Bushmen), was renamed admixed African individuals. The race and ethnicity of an individual was self-reported. Data for this study included US adults who self-reported as non-Hispanic Black (hereafter, Black), Hispanic or Latino, and non-Hispanic White (hereafter, White) individuals. We excluded individuals who self-reported being Asian or of other race and ethnicity (which included those who were American Indian or Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander) because of small sample sizes.

Additional Guidance for Use of Racial and Ethnic Collective Terms

Specific racial and ethnic terms are preferred over collective terms, when possible. Authors should report the specific categories used in their studies and recognize that these categories will differ based on the databases or surveys used, the requirements of funders, and the geographic location of data collection or study participants.

When collective terms are used, merging of race and ethnicity with a virgule as “race/ethnicity” is no longer recommended. Instead, “race and ethnicity” is preferred, with the understanding that there are numerous subcategories within race and ethnicity. Given that a virgule often means “and/or,” which can be confusing, do not use the virgule construction in this context (see also 8.4, Forward Slash [Virgule, Solidus]).

The general term minorities should not be used when describing groups or populations because it is overly vague and implies a hierarchy among groups. Instead, include a modifier when using the word “minority” and do not use the term as a stand-alone noun, for example, racial and ethnic minority groups and racial and ethnic minority individuals . 11 , 24 However, even this umbrella term may not be appropriate in some settings. Other terms such as underserved populations (eg, when referring to health disparities among groups) or underrepresented populations (eg, when referring to a disproportionately low number of individuals in a workforce or educational program) may be used provided the categories of individuals included are defined at first mention. 25 The term minoritized may be acceptable as an adjective provided that the noun(s) that it is modifying is included (eg, “racial and ethnic minoritized group”). Groups that have been historically marginalized could be suitable in certain contexts if the rationale for this designation is provided and the categories of those included are defined or described at first mention. 11

The nonspecific group label “other” for categorizing race and ethnicity is uninformative and may be considered pejorative. However, the term is sometimes used for comparison in data analysis when the numbers of those in some subgroups are too small for meaningful analyses. The term should not be used as a “convenience” grouping or label unless it was a prespecified formal category in a database or research instrument. In such cases, the categories included in “other” groups should be defined and reported. Authors are advised to be as specific as possible when reporting on racial and ethnic categories (even if these categories contain small numbers). If the numbers in some categories are so small as to potentially identify study participants, the specific numbers and percentages do not need to be reported provided this is noted. For cases in which the group “other” is used but not defined, the author should be queried for further explanation.

The terms multiracial and multiethnic are acceptable in reports of studies if the specific categories these terms comprise are defined or if the terms were predefined in a study or database to which participants self-selected. If the criteria for data quality and confidentiality are met, at a minimum, the number of individuals identifying with more than 1 race should be reported. Authors are encouraged to provide greater detail about the distribution of multiple racial and ethnic categories if known. In general, the term mixed race may carry negative connotations 13 and should be avoided, unless it was specifically used in data collection; in this case, the term should be defined, if possible. To the extent possible, the specific type of multiracial and multiethnic groups should be delineated.

In this study, 140 participants (25%) self-reported as multiracial, which included 100 (18%) identifying as Asian and White and 40 (7%) as Black and White.

Other terms may enter the lexicon as descriptors or modifiers for racial and ethnic categories of people. For example, the term people of color was introduced to mean all racial and ethnic groups that are not considered White or of European ancestry and as an indication of antiracist, multiracial solidarity. However, there is concern that the term may be “too inclusive,” to the point that it erases differences among specific groups. 13 , 26 - 28 There are similar concerns about use of the collective and abbreviated terms for Black, Indigenous, and people of color ( BIPOC ) and Black, Asian, and minority ethnic ( BAME ) (commonly used in the UK). Criticism of these terms has noted that they disregard individuals’ identities, do not include all underrepresented groups, eliminate differences among groups, and imply a hierarchy among them. 13 , 26 - 28 Although these terms may be used colloquially (eg, within an opinion article), preference is to describe or define the specific racial or ethnic categories included or intended to be addressed. These terms should not be used in reports of research, unless the terms are included in a database on which a study is based or specified in a research data collection instrument (eg, survey questionnaire).

In agreement with other guides, 13 , 24 other terms related to colors, such as brown and yellow , should not be used to describe individuals or groups. These terms may be less inclusive than intended or considered pejorative or a racial slur.

In addition, avoid collective reference to racial and ethnic minority groups as “non-White.” If comparing racial and ethnic groups, indicate the specific groups. Researchers should avoid study designs and statistical comparisons of White groups vs “non-White” groups and should specify racial and ethnic groups included and conduct analyses comparing the specific groups. If such a comparison is justified, authors should explain the rationale and specify what categories are included in the “non-White” group.

Capitalization

The names of races, ethnicities, and tribes should be capitalized, such as African American, Alaska Native, American Indian, Asian, Black, Cherokee Nation, Hispanic, Kamba, Kikuyu, Latino, and White. There may be sociopolitical instances in which context may merit exception to this guidance, for example, in an opinion piece for which capitalization could be perceived as inflammatory or inappropriate (eg, “white supremacy”).

Adjectival Usage for Specific Categories

Racial and ethnic terms should not be used in noun form (eg, avoid Asians , Blacks , Hispanics , or Whites ); the adjectival form is preferred (eg, Asian women, Black patients , Hispanic children , or White participants ) because this follows AMA style regarding person-first language. The adjectival form may be used as a predicate adjective to modify the subject of a phrase (eg, “the patients self-identified as Asian, Black, Hispanic, or White”). 11

Most combinations of proper adjectives derived from geographic entities are not hyphenated when used as racial or ethnic descriptors. Therefore, do not hyphenate terms such as Asian American , African American , Mexican American, and similar combinations, and in compound modifiers (eg, African American patient ).

Geographic Origin and Regionalization Considerations

Awareness of the relevance of geographic origin and regionalization associated with racial and ethnic designations is important. In addition, preferred usage may change about the most appropriate designation. For example, the term Caucasian had historically been used to indicate the term White , but it is technically specific to people from the Caucasus region in Eurasia and thus should not be used except when referring to people from this region.

The terms African American or Black may be used to describe participants in studies involving populations in the US, following how such information was recorded or collected for the study. However, the 2 terms should not be used interchangeably in reports of research unless both terms were formally used in the study, and the terms should be used consistently within a specific article. For example, among Black people residing in the US, those from the Caribbean may identify as Black but not as African American, whereas Black people whose families have been in the US for several generations may identify as Black and African American. When a study includes individuals of African ancestry in the diaspora, the term Black may be appropriate because it does not obscure cultural and linguistic nuances and national origins, such as Dominican, Haitian, and those of African sovereign states (eg, Kenyan, Nigerian, Sudanese), provided that the term was used in the study.

The term Asian is a broad category that can include numerous countries of origin (eg, Cambodia, China, India, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippine Islands, Thailand, Vietnam, and others) and regions (eg, East Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia). 29 The term may be combined with those from the Pacific Islands as in Asian or Pacific Islander . The term Asian American is acceptable when describing those who identify with Asian descent among the US population. However, reporting of individuals’ self-identified countries of origin is preferred when known. As with other categories, the formal terms used in research collection should be used in reports of studies.

In reference to persons indigenous to North America (and their descendants), American Indian or Alaska Native is generally preferred to the broader term Native American . However, the term Indigenous is also acceptable. There are also other specific designations for people from other locations, such as Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander . 29 , 30 If appropriate, specify the nation or peoples (eg, Inuit , Iroquois , Mayan, Navajo , Nez Perce , Samoan ). Many countries have specific categories for Indigenous peoples (eg, First Nations in Canada and Aboriginal in Australia). Capitalize the first word and use lowercase for people when describing persons who are Indigenous or Aboriginal (eg, Indigenous people, Indigenous peoples of Canada , Aboriginal people ). Lowercase indigenous when referring to objects, such as indigenous plants .

Hispanic , Latino or Latina , Latinx , and Latine are terms that have been used for people living in the US of Spanish-speaking or Latin American descent or heritage, but as with other terms, they can include people from other geographic locations. 29 , 30 Hispanic historically has been associated with people from Spain or other Spanish-speaking countries in the Western hemisphere (eg, Cuba, Central and South America, Mexico, Puerto Rico); however, individuals and some government agencies may prefer to specify country of origin. 29 - 31 Latino or Latina are broad terms that have been used for people of origin or descent from Cuba, Mexico, Puerto Rico, and some countries in Central America, South America, and the Caribbean, but again, individuals may prefer to specify their country of origin. 29 - 31 When possible, a more specific term (eg, Cuban , Cuban American , Guatemalan, Latin American , Mexican , Mexican American , Puerto Rican ) should be used. However, as with other categories, the formal terms used in research collection should be used for reports of studies. For example, some US agencies also include Spanish origin when listing Hispanic and Latino. The terms Latinx and Latine are acceptable as gender-inclusive or nonbinary terms for people of Latin American cultural or ethnic identity in the US. However, editors should avoid reflexively changing Latino and Latina to Latinx or vice versa and should follow author preference. Authors of research reports, in turn, should use the terms that were prespecified in their study (eg, via participant self-report or selection, investigator observed, database, electronic health record, survey instrument).

Description of people as being of a regional descent (eg, of African, Asian, European, or Middle Eastern or North African descent) is acceptable if those terms were used in formal research. However, it is preferable to identify a specific country or region of origin when known and pertinent to the study.

For the genome-wide association study discovery stage, study participants of African ancestry were recruited from Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, and the US, where the same phenotype definition was applied to diagnose primary open-angle glaucoma. The second validation meta-analysis included individuals with primary open-angle glaucoma and matched control individuals from Mali, Cameroon, Nigeria (Lagos, Kaduna, and Enugu), Brazil, Saudi Arabia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Morocco, and Peru.

For example, it is generally preferable to describe persons of Asian ancestry according to their country or regional area of origin (eg, Cambodian , Chinese , Indian , Japanese , Korean , Sri Lankan , East Asian , Southeast Asian ). Similarly, study participants from the Middle Eastern and North African region should be described using their nation of origin (eg, Egyptian , Iranian , Iraqi , Israeli , Lebanese ) when possible. Individuals of Middle Eastern and North African descent who identify with Arab ancestry and reside in the US may be referred to as Arab American . In such cases, researchers should report how categories were determined (eg, self-reported or selected by study participants or from demographic data in databases or other sources).

Note that Arab and Arab American, Asian and Asian American, Chinese and Chinese American , Mexican and Mexican American , and so on are not equivalent or interchangeable.

For studies that use national databases or include participants in a single country, a term for country of origin can be included if the term was provided at data collection (eg, Chinese American and Korean American for a study performed in the US, or Han Chinese and Zhuang Chinese for a study conducted in China). Again, how these designations were determined (eg, self-reported or selected or by other means) should be reported.

Abbreviations

Generally, abbreviations of categories for race and ethnicity should be avoided unless necessary because of space constraints (eg, in tables and figures) or to avoid long, repetitive strings of descriptors. If used, any abbreviations should be clearly explained parenthetically in text or in table and figure footnotes or legends.

Guidance for Journals and Publishers That Collect Data on Editors, Authors, and Peer Reviewers

Journals and publishers that collect race and ethnicity data on editors, editorial board members, authors, and peer reviewers should follow principles of confidentiality, privacy, and inclusivity and should permit individuals to self-identify or opt out of such identification. The Joint Commitment on Action for Inclusion and Diversity in Publishing is developing an international list of terms for journals and publishers that collect information on race and ethnicity. 32

Journals that collect information on race and ethnicity should not permit editorial decisions to be influenced by the demographic characteristics of authors, peer reviewers, editorial board members, or editors. In addition, the collection and use of such data should respect privacy regulations and be secured to prevent disclosure of personally identifiable information. Individual personally identifiable information of authors and peer reviewers should not be accessible to anyone involved in editorial decisions. Such data may be used in aggregate to benchmark and monitor strategies to promote and improve the diversity of journals.

Corresponding Author: Annette Flanagin, RN, MA, JAMA and the JAMA Network, 330 N Wabash Ave, Chicago, IL 60611 ( [email protected] ).

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Ms Christiansen is chair and Mss Flanagin and Frey are members of the AMA Manual of Style committee.

Members of the AMA Manual of Style Committee : Stacy L. Christiansen, MA, managing editor, JAMA ; Miriam Y. Cintron, BA, assistant managing editor, JAMA ; Angel Desai, MD, MPH, associate editor, JAMA Network Open , and assistant professor, University of California, Davis; Annette Flanagin, RN, MA, executive managing editor, JAMA and JAMA Network; Phil B. Fontanarosa, MD, MBA, interim editor in chief, JAMA and JAMA Network; Tracy Frey, BA, deputy managing editor, JAMA Network; Iris Y. Lo, BA, assistant deputy managing editor, JAMA Network; Connie Manno, ELS, freelance manuscript editing director, JAMA Network; and Christopher C. Muth, MD, senior editor, JAMA , and assistant professor, Rush University Medical Center.

Additional Contributions: We thank the following individuals for their thoughtful review and comments that helped shape this guidance: Nadia N. Abuelezam, ScD, Boston College William F. Connell School of Nursing; Adewole S. Adamson, MD, MPP, Associate Editor, JAMA Dermatology , University of Texas at Austin, Internal Medicine, Division of Dermatology; Dewesh Agrawal, MD, Children’s National Hospital, and Departments of Pediatrics and Emergency Medicine, George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences; Kristine J. Ajrouch, PhD, Department of Sociology, Eastern Michigan University; Germine H. Awad, PhD, University of Texas at Austin; Maria Baquero, PhD, MPH, senior social epidemiologist, Research and Evaluation Unit, Bureau of Epidemiology Services, Division of Epidemiology, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; Aisha Barber, MD, MEd, Children’s National Hospital, and Department of Pediatrics, George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences; Ashley Bennett, MD, Children's Hospital Los Angeles; Howard Bauchner, MD, former editor in chief, JAMA and JAMA Network; Khadijah Breathett, MD, MS, Department of Medicine, University of Arizona; Thuy D. Bui, MD, Department of Medicine, Global Health/Underserved Populations Track, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine; Kim Campbell, BS, senior manuscript editor, JAMA ; Jessica Castner, PhD, RN-BC, editor in chief, Journal of Emergency Nursing ; Linh Hồng Chương, MPH, Department of Health Policy & Management, UCLA Fielding School of Public Health; Francisco Cigarroa, MD, Department of Surgery, Director, Transplant Center, UT Health, San Antonio, and JAMA editorial board member; Desiree M. de la Torre, MPH, MBA, Community Affairs & Population Health Improvement, Children’s National Hospital; Christopher P. Duggan, MD, MPH, Center for Nutrition at Boston Children's Hospital and Harvard Medical School; Torian Easterling, MD, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; Enrique Escalante, MD, MSHS, director of Diversity Recruitment and Inclusion, Children’s National Hospital, and Department of Pediatrics, George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences; Lisa Evans, JD, Scientific Workforce Diversity Officer, National Institutes of Health; Olanrewaju O. Falusi, MD, Children’s National Hospital; Stephanie E. Farquhar, PhD, MHS, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; Glenn Flores, MD, Department of Pediatrics, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Holtz Children’s Hospital, Jackson Health System; Barbara Gastel, MD, MPH, Texas A&M College of Medicine, Humanities in Medicine; L. Hannah Gould, PhD, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; Carmen E. Guerra, MD, MSCE, vice chair of Diversity and Inclusion, Department of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania; P. Michael Ho, MD, PhD, University of Colorado, Aurora; Said Ibrahim, MD, MPH, MBA, Division of Healthcare Delivery Science & Innovation, Weill Cornell Medicine; Omer Ilahi, MD, Southwest Orthopedic Group; Alireza Hamidian Jahromi, MD, Rush University Medical Center; Quita Highsmith, MBA, chief diversity officer, Genentech; Renee M. Johnson, PhD, MPH, Department of Mental Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; Kamlesh Khunti, PhD, MD, University of Leicester; Trevor Lane, MA, DPhil, AsiaEdit; Cara Lichtenstein, MD, MPH, Children’s National Hospital; Francie Likis, DrPh, editor in chief, Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health ; Preeti N. Malani, MD, MSJ, associate editor, JAMA , and Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Disease, University of Michigan; Jacqueline McGrath, PhD, RN, School of Nursing, UT Health San Antonio; Michelle Morse, MD, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; Brahmajee K. Nallamothu, MD, MPH, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; Peter Olson, MA, manuscript editing coordinator, JAMA Network; Manish Pareek, MD, University of Leicester; Monica Peek, MD, MPH, Department of Medicine, Chicago Center for Diabetes Translational Research, University of Chicago; Jose S. Pulido, MD, MS, MPH, MBA, Wills Eye Hospital, and Departments of Ophthalmology and Molecular Medicine, Mayo Clinic; Zudin Puthucheary, MBBS, PhD, BMedSci, William Harvey Research Institute, Barts and The London School of Medicine & Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, Royal London Hospital, Barts Health NHS Trust; Sanjay Ramakrishnan, MBBS, Nuffield Department of Medicine, University of Oxford; Jeanne M. Regnante, chief health equity and diversity officer, LUNGevity Foundation; Allie Reynolds, Princeton University; Ash Routen, PhD, University of Leicester; James B. Ruben, MD, Folsom, California (retired); Randall L. Rutta, National Health Council; Deborah Salerno, PhD, senior medical writer, Salerno Scientific; Kanade Shinkai, MD, editor, JAMA Dermatology , and Department of Dermatology, University of California San Francisco; Erica S. Spatz, MD, MHS, Yale School of Medicine; Jenna Rose Stoehr, BA, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine; L. Tantay, MA, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; Ayanna Vasquez, MD, MS, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; and Jason H. Wasfy, MD, MPhil, Massachusetts General Hospital.

See More About

Flanagin A , Frey T , Christiansen SL , AMA Manual of Style Committee. Updated Guidance on the Reporting of Race and Ethnicity in Medical and Science Journals. JAMA. 2021;326(7):621–627. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.13304

Manage citations:

© 2024

Artificial Intelligence Resource Center

Cardiology in JAMA : Read the Latest

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Guidelines for Reporting Your Research

Reporting standards, bias and language.

- Language Services and Resources for Non-Native English Speakers

ASHA encourages the use of relevant reporting guidelines to help promote the transparency and reproducibility of scientific research. Although the submission of completed checklists for the relevant guidelines (and flow diagram, if applicable) alongside your manuscript is not required, we do strongly encourage that clinical studies appearing in ASHA journals meet recognized standards for designing and implementing their studies and reporting the findings:

- Articles reporting randomized clinical trials should follow the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials ( CONSORT ).

- Nonrandomized clinical evaluations should follow the Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs ( TREND ) statement.

- Studies of diagnostic accuracy should meet the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy ( STARD ).

Additional standards and checklists may be relevant depending on the type of study conducted. Therefore, authors are encouraged to review the Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency of health Research ( EQUATOR ) information in the Reporting Standards section

EQUATOR Network

Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency of health Research, better known as EQUATOR, is an international initiative with aims very much in alignment the goals of the ASHA Journals Program . The EQUATOR Network mission is to achieve accurate, complete, and transparent reporting of all health research studies to support research reproducibility and usefulness. To support EQUATOR’s goals, ASHA encourages the use of a relevant reporting guideline when writing any communication sciences and disorders research manuscript. It is hoped that by utilizing the appropriate reporting guidelines, the quality of research reports will be improved, enabling easier evaluation and better clinical applicability.

We invite you to submit completed checklists for the relevant guidelines (and flow diagram if applicable) alongside your manuscript, indicating the manuscript page on which each checklist item is found. Editable checklists for reporting guidelines can be found on the EQUATOR Network site ( www.equator-network.org ), which also gives general information on how to choose the correct guideline and why guidelines are important. Using a checklist helps to ensure you have used a guideline correctly.

At minimum, your article should report the content addressed by each item of the identified checklist or state that the item was not considered in the study and, if relevant, the reason why not (for example, if you did not use anonymizing, your article should explain this). Meeting these basic reporting requirements will greatly improve the value of your manuscript, may facilitate/enhance the peer review process, and may enhance its chances for eventual publication.

While checklists are not required, we encourage you to complete a checklist because this helps you to check that you have included all of the important information in your article, and because our editors and reviewers will also be asked to make use of reporting guidelines when peer reviewing submitted manuscripts. If the checklist indicates an item that you have not addressed in your manuscript, please either explain in the manuscript text why this information is not relevant to your study or add the relevant information.

Common Study Types and Appropriate Guidelines

Some common study types and the appropriate guidelines are listed below. If you cannot find an appropriate guideline here, search the full EQUATOR database . You may need to use more than one guideline, depending on your research. For example, if you randomly assigned human participants to one of two interventions, then conducted unstructured interviews with each participant, you will need to use CONSORT , COREQ , and TIDIER together. To make sure you collect all of the relevant guidelines, check each major heading, even if you have already found a relevant guideline under a previous major heading.

If you are reporting a protocol

Use the SPIRIT guideline for the protocol of a clinical trial. Use the PRISMA-P guideline for the protocol of a systematic review.

If you are reporting a review of a section of the existing literature

Use the ENTREQ guideline for a review of studies that use descriptive data, such as unstructured interviews (qualitative data). Use the MOOSE guideline for a review of observational studies. The PRISMA guideline should be used only for systematic reviews.

If you are reporting on animal research

Use the ARRIVE (or the UK version ) guideline for research on animals in a lab.

If you are reporting descriptive data (either alone or alongside quantitative analysis)

Use the COREQ guideline for reporting unstructured interviews and focus groups. Use the CARE guideline for reporting one case study or a series of case studies. Use the SRQR guideline for any other descriptive data (qualitative research).

If you are reporting research into diagnosis

Use the STARD guideline if you compared the accuracy of a diagnostic test with an established reference standard test. Use the REMARK guideline if you evaluated the prognostic value of a biomarker. Use the TRIPOD guideline if you developed, validated, or updated a prognostic or diagnostic prediction modelling tool.

If you are reporting research into an intervention or treatment on people

Use the TIDIER guideline to fully describe your intervention. Use the CHEERS guideline for an economic evaluation of the interventions.

If you are reporting research into an intervention, treatment, exposure, or protective factor on people

Use the CARE guideline for reporting one case study or a series of case studies. If you selected your participants before they received the intervention/exposure/etc. under study, AND You controlled which intervention/exposure/etc. they each received, AND You used a random allocation method to decide which intervention/exposure/etc. they each received (i.e., a randomised controlled trial) THEN , use the CONSORT guideline or one of its extensions. If you selected your participants after they received the intervention/exposure/etc. under study, OR You selected your participants before they received the intervention/exposure/etc. under study AND you did not control which intervention/exposure/etc. they received (they decided/their doctor decided/life just happened) (i.e., an observational study), THEN , use the STROBE guideline or one of its extensions. If you selected your participants before they received the intervention/exposure/etc. under study, AND If CARE, CONSORT, and STROBE are not applicable to your research AND You used a non-random way to decide which intervention/exposure/etc. your participants received, such as which hospital they went to or what their clinical symptoms were. (i.e., a non-randomised trial) THEN , use the TREND guideline.

The ASHA Journals Program follows the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.) style , which reminds authors to be mindful of using language that is free of bias—or the suggestion thereof. ASHA’s official statement on language and terminology related to disability and differing abilities is as follows:

ASHA adheres to the style guide of the American Psychological Association (APA) in using person-first or identity-first language to describe attributes and diagnoses of individuals or groups of people. When there is a preference, ASHA honors that preference. For more information, see APA’s style guidelines on bias-free language .

Per APA style, “It is unacceptable to use constructions that might imply prejudicial beliefs or perpetuate biased assumptions against persons on the basis of age, disability, gender, participation in research, racial or ethnic identity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, or some combination of these or other personal factors (e.g., marital status, immigration status, religion)” (p. 131).

However, when an author expresses a preference for identity-first language, ASHA honors that preference. Per APA style, “As always, good judgment is required—these are not rigid rules. If your writing reflects respect for your participants and your readers, and if you write with appropriate specificity and precision, you contribute to the goal of accurate, unbiased communication” (p. 131).

For many more details and examples on APA style recommendations for ensuring bias-free language—including entire sections on age, disability, gender, participation in research, racial and ethnic identity, sexual orientation and preference, socioeconomic status, and intersectionality—see APA’s online guide to bias-free language .

Bias Examples

Using the term "normal".

The use of “normal” to describe human beings is avoided because it suggests, incorrectly, that the other groups are somehow “abnormal.” Thus, ASHA rewords a phrase such as “normal participants” to “typical participants” to avoid describing a person as “normal.” In a similar way, we rephrase “normal-hearing participants” to “participants with normal hearing” to adhere to person-first language (which, in this instance, would be the most acceptable style).

APA discusses this in its section on false hierarchies in the chapter on bias-free language: “Compare groups with care. Bias occurs when authors use one group (often their own group) as the standard against which others are judged (e.g., using citizens of the United States as the standard without specifying why that group was chosen). For example, usage of “normal” may prompt readers to make the comparison with “abnormal,” thus stigmatizing individuals with differences” (p. 134).

What is normal, anyway?