Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Measures of empathy and compassion: A scoping review

Contributed equally to this work with: Cassandra Vieten, Caryn Kseniya Rubanovich, Lora Khatib, Meredith Sprengel, Chloé Tanega

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Centers for Integrative Health, Department of Family Medicine, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, California, United States of America, Clarke Center for Human Imagination, School of Physical Sciences, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, California, United States of America

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, California, United States of America, San Diego State University/University of California San Diego Joint Doctoral Program in Clinical Psychology, San Diego, San Diego, California, United States of America, T. Denny Sanford Institute for Empathy and Compassion, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, California, United States of America, T. Denny Sanford Center for Empathy and Technology, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, California, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, California, United States of America

Roles Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Human Factors, Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research (TNO), Soesterberg, The Netherlands

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Clarke Center for Human Imagination, School of Physical Sciences, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, California, United States of America

Roles Data curation, Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing

¶ ‡ CP, PV, AM, GC, AJL, MTS, LE and CB also contributed equally to this work.

Affiliations U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, VA Boston Healthcare System, Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America, Department of Psychiatry, Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America

Affiliation Compassion Clinic, San Diego, California, United States of America

Roles Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, California, United States of America, VA San Diego Center of Excellence for Stress and Mental Health, San Diego, California, United States of America

Affiliation VA San Diego Center of Excellence for Stress and Mental Health, San Diego, California, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, California, United States of America, VA San Diego Center of Excellence for Stress and Mental Health, San Diego, California, United States of America, Herbert Wertheim School of Public Health and Human Longevity Science, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, California, United States of America

Affiliation Departments of Family Medicine and Medicine (Bioinformatics), School of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, California, United States of America

Affiliations Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, California, United States of America, T. Denny Sanford Institute for Empathy and Compassion, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, California, United States of America, T. Denny Sanford Center for Empathy and Compassion Training in Medical Education, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, California, United States of America

Affiliations Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, California, United States of America, T. Denny Sanford Institute for Empathy and Compassion, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, California, United States of America, T. Denny Sanford Center for Empathy and Technology, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, California, United States of America, T. Denny Sanford Center for Empathy and Compassion Training in Medical Education, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, California, United States of America

- Cassandra Vieten,

- Caryn Kseniya Rubanovich,

- Lora Khatib,

- Meredith Sprengel,

- Chloé Tanega,

- Craig Polizzi,

- Pantea Vahidi,

- Anne Malaktaris,

- Gage Chu,

- Published: January 19, 2024

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297099

- Reader Comments

Evidence to date indicates that compassion and empathy are health-enhancing qualities. Research points to interventions and practices involving compassion and empathy being beneficial, as well as being salient outcomes of contemplative practices such as mindfulness. Advancing the science of compassion and empathy requires that we select measures best suited to evaluating effectiveness of training and answering research questions. The objective of this scoping review was to 1) determine what instruments are currently available for measuring empathy and compassion, 2) assess how and to what extent they have been validated, and 3) provide an online tool to assist researchers and program evaluators in selecting appropriate measures for their settings and populations. A scoping review and broad evidence map were employed to systematically search and present an overview of the large and diverse body of literature pertaining to measuring compassion and empathy. A search string yielded 19,446 articles, and screening resulted in 559 measure development or validation articles reporting on 503 measures focusing on or containing subscales designed to measure empathy and/or compassion. For each measure, we identified the type of measure, construct being measured, in what context or population it was validated, response set, sample items, and how many different types of psychometrics had been assessed for that measure. We provide tables summarizing these data, as well as an open-source online interactive data visualization allowing viewers to search for measures of empathy and compassion, review their basic qualities, and access original citations containing more detail. Finally, we provide a rubric to help readers determine which measure(s) might best fit their context.

Citation: Vieten C, Rubanovich CK, Khatib L, Sprengel M, Tanega C, Polizzi C, et al. (2024) Measures of empathy and compassion: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 19(1): e0297099. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297099

Editor: Ipek Gonullu, Ankara University Faculty of Medicine: Ankara Universitesi Tip Fakultesi, TURKEY

Received: July 5, 2023; Accepted: December 21, 2023; Published: January 19, 2024

Copyright: © 2024 Vieten et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: CV received a grant from the T. Denny Sanford Institute for Empathy and Compassion at https://empathyandcompassion.ucsd.edu/ . Co-authors included faculty members affiliated with the T. Denny Sanford Institute who were involved in study design and reviewing/editing the manuscript. Other than that, the funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Historically, psychological assessment has overwhelmingly focused on measuring human struggles, difficulties, and pathologies. However, converging evidence indicates that positive emotions and prosocial qualities are just as important for improving overall well-being as stress, depression, and anxiety are to detracting from health and well-being [ 1 ]. Across fields—from medicine, mental health care, and education to economics, business and organizational development—there is a growing emphasis on investigating prosocial constructs such as compassion and empathy [ 2 ].

Compassion, or the heartfelt wish to reduce the suffering of self and others, promotes social connection and is an important predictor of overall quality of life [ 2 ] and well-being [ 3 ]. Empathy, or understanding and vicariously sharing other people’s positive emotions, is related to prosocial behaviors (e.g., helping, giving, emotional support), positive affect, quality of life, closeness, trust, and relationship satisfaction [ 4 ]. Compassion and empathy improve parenting [ 5 ], classroom environments [ 6 ], and teacher well-being [ 7 ]. Compassionate love toward self and others is associated with disease outcomes as well, such as increased long-term survival rates in patients with HIV [ 8 ]. Self-compassion refers to being gentle, supportive, and understanding toward ourselves in instances of perceived failure, inadequacy, or personal suffering [ 9 ]. Research indicates that self-compassion appears to reduce anxiety, depression, and rumination [ 10 ], and increase psychological well-being and connections with others [ 11 , 12 ]. Both compassion and self-compassion appear to protect against stress [ 13 ] and anxiety [ 10 ].

In healthcare professionals, empathy is associated with patient satisfaction, diagnostic accuracy, adherence to treatment recommendations, clinical outcomes, clinical competence, and physician retention [ 14 – 16 ]. Importantly, it is also linked to reduced burnout, medical errors, and malpractice claims [ 17 ]. However, evidence indicates that empathy declines during medical training and residency [ 18 – 20 ]. This may present an opportunity to improve many aspects of healthcare by identifying ways to maintain or enhance empathy during medical training. It is also important to note that while empathy is beneficial for patients, the effects on healthcare professionals are more complicated. A distinction can be drawn between positive empathy and/or compassion versus over-empathizing , which can lead to what has been termed “compassion fatigue” and/or burnout.

Disentangling these relationships through scientific investigation requires selecting measures and instruments capable of capturing these nuances. In addition, growing evidence that empathy and compassion can be improved through training [ 21 , 22 ] relies on selection or development of measures that can assess the effectiveness of such training. While empathy and compassion training for healthcare professionals has shown positive outcomes, it still requires improvement. For example, in a recent systematic review, only 9 of 23 empathy education studies in undergraduate nursing samples demonstrated practical improvements in empathy [ 23 ]. Another systematic review of 103 compassion interventions in the healthcare context [ 24 ] identified a number of limitations such as focusing on only a single domain of compassion; inadequately defining compassion; assessing the constructs exclusively by self-report; and not evaluating retention, sustainability, and translation to clinical practice over time: all related to how compassion and empathy are conceptualized and measured. The researchers recommend that such interventions should “be grounded in an empirically-based definition of compassion; use a competency-based approach; employ multimodal teaching methods that address the requisite attitudes, skills, behaviors, and knowledge within the multiple domains of compassion; evaluate learning over time; and incorporate patient, preceptor, and peer evaluations” (p. 1057). Improving conceptualization and measurement of compassion and empathy are crucial to advancing effective training.

Conceptualizing compassion and empathy

Compassion and empathy are complex constructs, and therefore challenging to operationalize and measure. Definitions of compassion and empathy vary, and while they are often used interchangeably, they are distinct constructs [ 25 ]. Like many other constructs, both compassion and empathy can be conceptualized at state and/or trait levels: people can have context-dependent experiences of empathy or compassion (i.e., state), or can have a general tendency to be empathic or compassionate (i.e., trait). The constructs of empathy and compassion each have multiple dimensions: affective, cognitive, behavioral, intentional, motivational, spiritual, moral and others. In addition to their multidimensionality, compassion and empathy are crowded by multiple adjacent constructs with which they overlap to varying degrees, such as kindness, caring, concern, sensitivity, respect, and a host of behaviors such as listening, accurately responding, patience, and so on.

Strauss et al. [ 26 ] conducted a systematic review of measures of compassion, and by combining the definitions of compassion among the few existing instruments at the time, proposed five elements of compassion: recognizing suffering, understanding the universality of human suffering, feeling for the person suffering, tolerating uncomfortable feelings, and motivation to act/acting to alleviate suffering. Gilbert [ 27 ] proposed that compassion consists of six attributes: sensitivity, sympathy, empathy, motivation/caring, distress tolerance, and non-judgement.

Likewise, empathy has been conceptualized as having at least four elements (as measured by the Interpersonal Reactivity Index [ 28 ] for example): perspective-taking (i.e., taking the point of view of others), fantasy (i.e., imagining or transposing oneself into the feelings and actions of others), empathic concern (i.e., accessing other-oriented feelings of sympathy or concern) and personal distress (i.e., or unease in intense interpersonal interactions). Early work by Wiseman [ 29 ] used a concept analysis approach identifying four key domains of empathy: seeing the world the way others see it, understanding their feelings, being non-judgmental, and communicating or expressing that understanding. Other conceptualizations of empathy [ 30 ] include subdomains of affective reactivity (i.e., being emotionally affected by others), affective ability (i.e., others tell me I’m good at understanding them), affective drive (i.e., I try to consider the other person’s feelings), cognitive drive (i.e., trying to understand or imagine how someone else feels), cognitive ability (i.e., I’m good at putting myself in another person’s shoes), and social perspective taking. De Waal and Preston [ 31 ] propose a “Russian doll” model of empathy, in which evolutionary advances in empathy layer one on top of the next, resulting in their definition of empathy as “emotional and mental sensitivity to another’s state, from being affected by and sharing in this state to assessing the reasons for it and adopting the other’s point of view” (p. 499).

Compassion is conceptualized as generally positive, and “more is better” in terms of health and well-being. Empathy on the other hand can lead to positive outcomes such as empathic concern, compassion, and prosocial motivations and behaviors, whereas unregulated empathic distress can be aversive, decrease helping behaviors, and lead to burnout [ 32 ]. Compassion and empathy also appear to differ in underlying brain structure [ 33 ] as well as brain function [ 34 ]. Terms such as “compassion fatigue” are more accurately characterized as empathy fatigue, and some evidence indicates that compassion can actually counteract negative aspects of empathy [ 35 ].

When assessing compassion and empathy, it is often important to measure their opposites, or constructs that present barriers to experiencing and expressing compassion or empathy. Personal distress, for example, can be confused for empathy but in fact is a “self-focused, aversive affective reaction” to encountering another person’s suffering, accompanied by the desire to “alleviate one’s own, but not the other’s distress” [ 36 , p.72]. Personal distress is viewed as a barrier to true compassion, and experienced chronically, is associated with burnout (i.e. exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy due to feeling frenetic/overloaded, underchallenged/indifferent, or worn-out/neglected [ 37 ]).

Other constructs that have been measured as barriers to compassion include lack of empathy or empathy impairment, apathy, coldness, judgmental attitudes toward specific populations or conditions, and fear of compassion. In sum, compassion and empathy are not so much singular constructs as multi-faceted collections of cognitions, affects, motivations and behaviors. When researchers or program evaluators consider the best ways to assess empathy and compassion, they must often attend to measuring these constructs as well.

Past systematic reviews focused on measurement of empathy and compassion sought to (1) review definitions [ 26 , 38 ]; (2) evaluate measurement methods [ 39 ]; (3) assess psychometric properties [ 40 ]; (4) provide quality ratings [ 26 , 41 , 42 ]; and/or (5) recommend gold standard measures [ 26 , 43 ]. To our knowledge, this review is the first scoping review focused on capturing the wide array of instruments measuring empathy, compassion, and adjacent constructs.

We conducted a scoping review and broad evidence map (as opposed to a systematic review or meta-analysis) for several reasons. Whereas systematic reviews attempt to collate empirical evidence from a relatively smaller number of studies pertaining to a focused research question, scoping reviews are designed to employ a systematic search and article identification method to answer broader questions about a field of study. As such, this scoping review provides a large and diverse map of the available measures across this family of constructs and measurement methodology, with the primary goal of aiding researchers and program evaluators in selecting measures appropriate for their setting.

Another unique feature of this scoping review is a data visualization that we have developed to help readers navigate the findings. This interactive tool is called the Compassion and Empathy Measures Interactive Data Visualization (CEM-IDV) ( https://imagination.ucsd.edu/compassionmeasures/ ).

The aims of this scoping review were achieved, including 1) identifying existing measures of empathy and compassion, 2) providing an overview of the evidence for validity of these measures, and 3) providing an online tool to assist researchers and program evaluators in searching for and selecting the most appropriate instruments to evaluate empathy, compassion, and/or adjacent constructs, based on their specific context, setting, or population.

The objective of this project was to capture all peer-reviewed published research articles that were focused on developing, or assessing the psychometric properties of, instruments measuring compassion and empathy and overlapping constructs, such as self-compassion, theory of mind, perspective taking, vicarious pain, caring, the doctor-patient relationship, emotional cues, sympathy, tenderness and emotional intelligence. We included only articles that were specifically focused on measure development or validation, and therefore did not include articles that may have developed idiosyncratic ways of assessing compassion or empathy in service to conducting experiments. We included self-report assessments, observational ratings or behavioral coding schemes, and tasks. This review was conducted according to the PRISMA statement for scoping reviews [ 44 ]. The population, concept, and context (PCC) for this scoping review were 1) population: adults and children, 2) concepts: compassion and empathy, and 3) context: measures/questionnaires for English-speaking populations (behavioral measures and tasks in all languages).

Eligibility criteria

Articles were included if they focused on development or psychometric validation/evaluation of whole or partial scales, tasks, or activities designed to measure empathy, compassion, or synonymous or adjacent constructs. Conference proceedings and abstracts as well as grey-literature were excluded from this review, as were articles in languages other than English or reporting on self-report scales that were in languages other than English. Behavioral tasks or observational measures that were conducted in languages other than English, but were reported in English and could be utilized in an English-speaking context, were included. Papers were excluded if they were in a language other than English, did not include human participants, or did not focus on reporting on development or psychometric validation of measures of compassion, empathy, or adjacent constructs.

Information sources

To identify the peer-reviewed literature reporting on the psychometric properties of measures of empathy and compassion, the following databases were searched: PubMed, Embase, PsychInfo, CINAHL, and Sociological Abstracts. See Table 1 to review the search terms and strategy applied for each database. All databases were searched in October 2020 and again in May 2023 by a reference librarian trained in systematic and scoping reviews at the University of California, San Diego library.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297099.t001

Abstracts of the articles identified through the search were uploaded to Covidence [ 45 , 46 ]. Covidence is a web-based collaboration software platform that streamlines the production of systematic and other literature reviews. Each article was screened by two reviewers and any conflicts reviewed in team meetings until the team reached 90% agreement. Thereafter, one screener included or excluded each abstract.

Full text screening

After articles were screened in, full text for all articles tagged as “Measure Development/Validation” were uploaded to the system. The project coordinator (MS) reviewed all articles that were included to ensure that they were tagged appropriately and that all articles reporting on development or validation of measures or assessments of psychometric properties were included in this review.

Each article was reviewed for its general characteristics and psychometric evaluation/validation data reported. General data extracted from each article included: the article title, full citation, abstract, type of study, the name of the scale/assessment/measure, the author’s definition of the construct(s) being measured (if stated), the specific purpose of the scale (context and population, such as “a scale for measuring nurses’ compassion in patient interactions”), whether the measure was conceptualized as assessing state or trait (or neither or both); whether the scale was self-report, peer-report, or expert observer/coder; the validation population, number, gender proportion, and location; and any reviewer notes.

See Table 2 for the psychometric data extracted from each article. In this scoping review we did not evaluate or record/analyze the results of the psychometric evaluations or validations. We only recorded whether or not they had been completed. Because some members of the team did not have enough experience/training to properly identify psychometric evaluations or assessments, data extraction was completed using two data extraction forms (i.e., one for general data and one for psychometric data) constructed in Survey Planet [ 47 ]. A group of four experienced coders completed both the general and psychometric data extraction forms, and a group of six less experienced coders completed only the general data extraction form with an experienced coder completing the psychometric data extraction form.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297099.t002

Once the data were extracted, they were reviewed by the research coordinator or principal investigator and combined into a spreadsheet. After combining, the answers were reviewed by a team of four additional reviewers to ensure that the information extracted was correct. These four reviewers received additional training on how to confirm that the appropriate information was extracted from the article as well as how to clean the information in a systematic way.

Systematic literature search

A total of 29,119 articles were identified and 9,673 duplicates were removed, resulting in 19,446 titles/abstracts screened for eligibility ( Fig 1 ). A total of 10,553 full-text articles were assessed for inclusion based on the criteria previously described. A total of 6,023 articles were included in the final sample. Of these articles, 559 reported on the development or validation of a measure of empathy and/or compassion, 1,059 identified biomarkers of empathy and/or compassion, and 3,936 used a measure or qualitative interview of empathy or compassion in the respective study. This scoping review reports on the 559 measure development/validation articles.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297099.g001

Measure development and validation studies

An overview of the 503 measures of empathy or compassion that were developed, validated, or psychometrically evaluated in the 559 articles can be found in the S1 Table . The majority of the studies ( n = 181) used a student population for development and/or validation. Student populations included undergraduate students, nursing students, and medical students. A total of 136 studies used samples of general, healthy adults (18 and older). Eighty-three (83) studies developed and/or validated a measure using health care workers, mostly comprising physicians and nursing staff. A total of 66 studies reported on a combined sample of populations such as clinicians and patients. There were 63 studies that used a patient population (e.g., cancer patients, surgical patients). A total of 34 studies used samples of individuals in other specific professions (e.g., military personnel), 32 used youth and adolescent samples (5–18 years old), 18 included older adults/aging populations, while 28 used samples in mental health care related professions (e.g., therapists). Nine studies used samples in other specific populations (e.g., spouses of depressed patients).

The number of possible psychometric assessments was 13 (see list below), and the total types of psychometric assessments reported for each measure ranged from 0 to 12. On average, each measure reported four types of psychometric assessments being completed. The measures with the highest number of psychometric assessments reported included the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) and the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) with 12 psychometric assessments each. All scales with eight or more psychometric assessments reported in the articles we located can be found in S2 Table .

In regards to the type of psychometric assessments reported, a total of 409 studies assessed internal consistency, 342 used construct validity, 316 used factor analysis or principal component analysis, 299 assessed convergent validity, 218 used confirmatory factor analysis, 187 evaluated content validity, 165 tested for discriminant/divergent validity, 108 assessed test re-test reliability, 71 measured interrater reliability, 69 tested for predictive validity, 68 used structural equation modeling, 38 controlled for or examined correlations with social desirability, and 6 used a biased responding assessment or “lie” scale. Eighty studies performed other advanced statistics.

Measures of empathy and compassion

A total of 503 measures of compassion and empathy were identified in the literature. S3 Table is sorted alphabetically by the name of the measure, and includes a description of each measure, year developed, type of measure, subscales (if applicable), administration time (if provided), number of items, sample items, and response set. The majority of the scales were developed in the past decade (since 2013). Most of the measures identified were self-report scales (412 scales). Fifty-three (53) were peer/corollary report measures (descriptions of target individuals’ thoughts, feelings, motives, or behaviors), and 38 were behavioral/expert coder measures (someone who has been trained to assess target’s thoughts, feelings motives or behaviors). There were 370 measures with subscales and 133 measures without subscales. The number of items of each scale varied widely from 1 item to 567 items. The average number of items was 32 (SD = 45.2) and the median was 21 items. Most authors did not report on the estimated time it would take to complete the measure.

Interactive data visualization

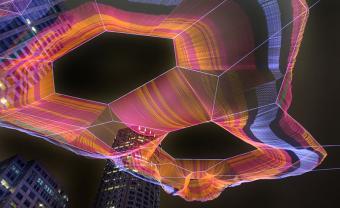

Data visualizations are graphical representations of data designed to communicate key aspects of complex datasets [ 48 ]. Interactive data visualizations allow users to search, filter, and otherwise manipulate views of the data, and are increasingly being used for healthcare decision making [ 49 ]. We used Google Data Studio to create an online open-access interactive data visualization ( Fig 2 ) displaying the results of this scoping review. Access it at: https://imagination.ucsd.edu/compassionmeasures/

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297099.g002

The purpose of this Compassion and Empathy Measures Interactive Data Visualization (CEM-IDV) is to assist health researchers and program evaluators in selecting appropriate measures of empathy and compassion based on a number of parameters, as well as learning more about how these constructs are currently being conceptualized. Visualization parameters include: number of types of psychometric assessments completed (1–12) on the y-axis, number of items on the x-axis (with measures with over 70 items appearing on a separate display, not shown in Fig 2 ), and the bubble size indicating the number of participants in the validation studies. Search filters include Population in which the measure has been validated (e.g. students, healthcare workers, general adults), Construct (e.g. empathy, compassion, caring, self-compassion), and Type of Measure (e.g. self-report, behavioral/expert coder). Users can also search measures by name of the parent measure. For example, there are multiple versions of the Jefferson Scale of Empathy (JSE) (e.g., for physicians, for nurses, for medical students). To retrieve all articles reporting on any version of the JSE, one would search for the parent measure (i.e., “Jefferson Scale of Empathy”). If a measure does not have multiple versions (for example, the Griffith Empathy Measure), this search would yield all articles on that single version.

A robust science of compassion and empathy relies on effective measures. This scoping review examined the broad literature of peer-reviewed published research articles that either developed, or assessed the psychometric properties of, instruments measuring compassion and empathy. The review also includes overlapping and related constructs such as self-compassion, theory of mind, perspective-taking, vicarious pain, caring, the doctor-patient relationship, emotional cues, sympathy, tenderness, and emotional intelligence.

Our review indicates that the field of measuring compassion and empathy is maturing. Strides have been made in recent years in conceptualization, definition, and assessment of compassion and empathy. Since the time of earlier critical reviews of measurement of compassion and empathy, several measures have gained more psychometric support: S2 Table shows that 34 measures have been subjected to 9 or more types of psychometric validation. Multiple measures in this review demonstrate consistent reliability and validity along with many other strengths.

Newer measures align more closely with experimental, theoretical and methodological advances in understanding the various components of compassion and empathy. For example, the newer Empathic Expressions Scale [ 50 ] recognizes that actual empathy behaviors are different from cognitive and affective aspects of empathy. In another example, increasing understanding of the role of warmth and affection as an important component of empathy has led to the development of the Warmth/Affection Coding System (WACS) [ 51 ]. That measure also includes both micro- and macro-social observations, recognizing that implicit and explicit behaviors are important for assessment.

As measurement becomes more precise, assessments have also reflected increasing understanding of the differences between compassion and empathy, and the interaction between the two. For example, the Compassion Scale [ 52 ] subscales include kindness, common humanity, mindfulness and indifference (reverse-scored), whereas the family of the Jefferson Scale(s) of Empathy include compassion as well as “standing in the patient’s shoes” and “understanding the client’s perspective.” Recognizing recent research on how compassion could temper consequences of empathic distress such as burnout, it becomes important for researchers and program evaluators to not only avoid conflating the two, but also measure both separately.

Empathy and compassion in specific circumstances for specific populations have also been developed, such as the Body Compassion Questionnaire [ 53 ] with clear relevance for adolescents and young adults, as well as those with eating and body-dysmorphic disorders, or the modified 5-Item Compassion Measure [ 54 ] created specifically for patients to assess provider compassion during emergency room visits.

In our review, we included self-report assessments, peer/corollary observational measures, and behavioral tasks/expert coder measures, for adults and children in English-speaking populations. A discussion of the utility of each of these types of measures follows, along with a rubric for measure selection that researchers and program evaluators can use with the assistance of the tables and/or CEM-IDV online tool.

Self-report measures

The vast majority of measures of empathy and compassion are self-report measures (surveys, questionnaires, or items asking people to report on their own compassion and empathy). While perhaps the most efficient way to assess large numbers of participants, historically self-assessments of compassion and empathy have been riddled with challenges. Over a decade ago, Gerdes et al. [ 38 ] in their review of the literature noted that:

In addition to a multitude of definitions, different researchers have employed a host of disparate ways to measure empathy (Pederson, 2009). A review of the literature pertaining to empathy reveals that as a result of these inconsistencies, conceptualisations and measurement techniques for empathy vary so widely that it is difficult to engage in meaningful comparisons or make significant conclusions about how we define and measure this key component of human behaviour. (pp. 2327).

While a 2007 systematic review of 36 measures of empathy identified eight instruments demonstrating evidence of reliability, internal consistency, and validity [ 40 ], a systematic review of 12 measures of empathy used in nursing contexts [ 41 ] revealed low-quality scores (scoring 2–8 on a scale of 14), concluding that none of the measures were both psychometrically and conceptually satisfactory.

Our scoping review did not assess psychometric robustness other than the number of psychometric assessments completed, but a 2022 systematic review of measures of compassion [ 26 ] continued to reveal low-quality ratings (ranging from 2 to 7 out of 14) due to poor internal consistency for subscales, insufficient evidence for factor structure and/or failure to examine floor/ceiling effects, test-retest reliability, or discriminant validity. They concluded that “currently no psychometrically robust self- or observer-rated measure of compassion exists, despite widespread interest in measuring and enhancing compassion towards self and others” (pp. 26).

Several issues have been identified as potentially explaining shortcomings of compassion and empathy measures. For example, definitions of compassion and empathy vary widely in scholarly and popular vernacular, which can lead to variability in respondents’ perceptions. In addition to issues of semantics, the vast majority of compassion and empathy measures are face valid, relying on questions such as “I feel for others when they are suffering,” or “When I see someone who is struggling, I want to help.” These questions can increase the risk for social desirability bias (i.e., the tendency to give overly positive self-descriptions either to others or within themselves) and other response biases. Indeed, feeling uncompassionate can be quite difficult to admit, requiring not only a large degree of self-reflection and insight, but also an ability to manage the cognitive dissonance, shame, or embarrassment that could accompany such an admission. This difficulty may be particularly true among healthcare professionals.

Using self-report measures to assess the impact of compassion-focused interventions can also be confounded by mere exposure and demand characteristics, particularly when compared to standard-of-care or wait-list controls. In other words, after spending eight-weeks learning about and practicing compassion, it is not surprising that one might more frequently endorse items with respect to compassion due to increased familiarity with the concept, or implicit desire to satisfy experimenters, as opposed to increased compassionate states or behaviors. On the other hand, interventions could paradoxically result in people more accurately rating themselves lower on these outcomes once they investigate more thoroughly their own levels of, and barriers to, compassion and empathy, potentially masking improvements.

Peer/corollary and behavioral/expert coder measures

With increasing technological, statistical, and conceptual sophistication, we can innovate new measures that can increase validity by triangulating more objective measures with self-perceptions. In fact, multiple measures using observation and ratings by peers, patients, or trained/expert behavioral coders have been developed to do just that. We identified 61 measures utilizing observational measures or peer/corollary reports, some involving a spouse, friend, supervisor, client or patient completing a questionnaire, rating form or checklist regarding their observations of that person. These measures may also include ratings of a live or recorded interaction by someone who has been trained to assess, or is an expert in assessing, compassion or empathy behaviors. Compassion or empathy behaviors include verbalizations and signals such as eye contact, tone of voice, or body language. Similarly, qualitative coding of transcribed narratives, interactions, or responses to interview questions or vignettes can be conducted with human qualitative coders, which is increasingly supported by artificial intelligence.

These methods have the clear benefit of avoiding self-report biases and providing richer data for each individual (for use in admissions or competency exams for instance). However, they can be labor intensive, can introduce potential changes in behavior due to knowing one is being observed, and can introduce another layer of subjectivity on the part of the observer/rater (which can be overcome in part by measures of agreement between two or more raters). They also tend to have fewer psychometric assessments testing their validity or reliability than other measures.

Behavioral tasks

Laboratory-based behavioral tasks have been useful for assessing empathy and compassion under controlled conditions while reducing self-report biases and taking less time than qualitative/observational measures. These lab protocols involve exposure to stimuli designed to induce empathy and compassion or related constructs. For example, respondents might view a video-recorded vignette that reliably results in responses to seeing another person who is suffering [ 55 ] or write a letter to a prison inmate who has committed a violent crime [ 56 ]. Game theory has been used to create tasks focused on giving people options to share with, withhold from, or penalize others with cash, points, or goods. These are used to assess prosocial behaviors and constructs adjacent to empathy and compassion such as altruism and generosity [ 57 ].

The association of these implicit measures of compassion and empathy with real-world settings or with subjective perceptions of empathy and compassion is unknown. A meta-analysis of 85 studies ( N = 14,327) indicates that self-report cognitive empathy scores account for only approximately 1% of the variance in behavioral cognitive empathy assessments [ 58 ]. This finding could demonstrate the superiority of implicit measures and a rather damning verdict for the accuracy of self-perceptions, or could imply that these different types of measures are capturing very different constructs (a problem that exists across many psychosocial versus behavioral measures, see [ 59 ]).

Selecting measures

Our review revealed that there is not one or even a few measures of empathy and compassion that are best across all situations. Rather than providing overarching recommendations, therefore, we emphasize that measurement is context-dependent. As such, we recommend a series of questions researchers and program evaluators might ask themselves when selecting a measure.

We encourage readers to use the online CEM-IDV as a decision-aid tool to identify the best measure for their specific needs. To select the most appropriate instrument(s), we offer the following questions (in a suggested order) to provide guidance:

- Which precise domains of empathy, compassion, or adjacent constructs do you want to measure? For example, is it the participant’s experience of empathy, or a skill or behavior? See the “General Construct” dropdown menu. Because definitions of empathy, compassion and related constructs are often imprecise, investigate whether the sample items, factors, and authors’ definition of the construct matches the outcome or variable you actually want to measure.

- What measurement type is best suited to answering your research/evaluation question, or what is feasible for your setting and sample size? For example, if you have limited time or a large sample size, you may prefer a self-report survey, whereas if you are concerned about self-report bias, you might consider a direct observation or behavioral task/expert coder measure. Use S1 Table to examine measures by type of measure, or use the “Type of Measure” filter in the CEM-IDV.

- What measure length, number of items, or time it takes to complete the assessment is feasible for the study? Refer to the X-axis of the CEM-IDV tool.

- What population (s) are you working with? Use the population filter to explore whether the measures you are considering have been validated in those populations.

- Do you want to differentiate the domain you are measuring from other adjacent constructs , such as sympathy or altruism, or distinguish between empathy and compassion? Select and include measures of each construct in order to make this distinction. Finally, now that you have selected several candidate measures, ask:

- How valid and reliable is the measure? Use S1 Table or the Y-axis of CEM-IDV tool to determine which psychometric assessments have been completed, and click on the measure in the table below to review the full text of the papers to discover the strength of those assessments, as well as familiarizing oneself with the recent literature on the measure. Evidence for the validity, factor structure, or length of measures is often hotly debated, and it can be that a measure has been improved or its interpretation cautioned by recent literature.

For example, imagine you are conducting a study of emergency room outcomes, including number of admissions, time from registration to discharge, and patient satisfaction. You would like to include emergency-room healthcare-provider empathy and/or compassion as a potential predictor or mediator of outcomes. After reviewing the literature on the topic and the definitions, you decide that compassion is the specific domain you are most interested in (Question 1). Because you are aware of the limitations of self-report measures, you decide not to use a self-report measure. You recognize that peer-reports, behavioral tasks, or expert coders are not appropriate for the fast-paced environment and number of interactions, but decide that patient reports of provider compassion would be ideal (Question 2). You recognize that the questionnaire must be brief, given the existing measurement burden and limited time participants have (Question 3). The population is emergency room clinicians and patients (Question 4). In this case, you are not interested in differentiating compassion from other similar constructs because that is not relevant to the question you are trying to answer: whether emergency room physician compassion predicts or mediates patient outcomes (Question 5).

In this case, you might use the CEM-IDV tool to select the population “Patients” and the construct “Compassion.” Your search yields eight potential measures, and upon reviewing each, you find that the 5-item Compassion Scale [ 54 ] has sample items that reflect what you are hoping to measure and was validated with emergency room patients and their clinicians. It demonstrates good reliability and validity and is an excellent choice for your project.

Strengths and limitations

This scoping review has several strengths. First, it covers a wide breadth of literature on ways to assess empathy, compassion, and adjacent constructs using different types of measures (i.e., self-report, peer/corollary report, and behavioral/expert coder). Second, the findings were integrated into an accessible interactive data visualization tool designed to help researchers/program evaluators identify the most suitable measure(s) for their context. Third, the review team included individuals with expertise in conducting reviews, with the project manager having received formal training in best practices for systematic reviews, and an experienced data librarian helping to develop the search string and conduct the literature search. Fourth, the literature search was conducted without a start date limitation, thus capturing all measures published prior to October 2020. Fifth, the review team employed a comprehensive consensus process to establish study inclusion/exclusion criteria and utilized state-of-the-art review software, Covidence, to support the process of screening and data extraction.

There are also several limitations to consider. First, our literature search was limited to five databases (i.e., PubMed, Embase, PsychInfo, CINAHL, and Sociological Abstracts), and excluded grey literature, conference proceedings/abstracts, and measures not written in English. We also included only articles specifically focused on development and/or psychometric validation of measures. Thus, it is possible we missed relevant measures. Second, although we captured how frequently a measure was validated and the types of available psychometric evidence for each measure, we did not review the quality of the evidence. Measures with greater numbers of psychometric assessments may not necessarily be the most appropriate in all contexts or for particular settings, and psychometric studies can lead to conflicting results/interpretations. Importantly, the number of psychometric assessments might be skewed in favor of older measures that have existed in the scientific literature longer, and allegiance biases are possible. Thus, we reiterate that readers would benefit most from using the questions recommended above when selecting measures. Third, this scoping review provides a static snapshot of available measures through October 2020 and does not include measures that may have been published after that time.

Finally, the scoping review does not identify gold-standard measures to use. While systematic reviews typically include quality assessments, scoping reviews do not. Rather, scoping reviews seek to present an overview of a potentially large and diverse body of literature pertaining to a topic. As such, this review did not evaluate the quality of design, appraise the strength of the evidence, or synthesize reliability or validity results for each study. It may therefore include multiple studies that may have weak designs, low power, or evidence inadequate to the conclusions drawn.

Given the multitude of problems facing society (e.g., violence and war, social injustices and inequities, mental health crises), learning how to cultivate compassion and empathy towards self and others is one of the most pressing topics for science to address. Furthermore, studies of compassion, empathy, and adjacent constructs rely on the use of appropriate measures, which are often difficult to select due to inconsistent definitions and susceptibility to biases. Our scoping review identified and reviewed numerous measures of compassion, empathy, and adjacent constructs, extracting the qualities of each measure to create an interactive data visualization tool. This tool is intended to assist researchers and program evaluators in searching for and selecting the most appropriate instruments to evaluate empathy, compassion, and adjacent constructs based on their specific context, setting, or population. It does not replace reviewers’ own critical evaluation of the instruments.

How a construct is measured reflects how it is being defined and conceptualized. Reviewing the subscales/factors and individual items that make up each measure sheds light on how each of these measures conceptualizes empathy and compassion. Ongoing research by our team is using these subscales, factors and items across measures to construct a conceptual map of compassion and empathy, which will be reported in a future paper. In the meantime, a useful feature of the CEM-IDV is that the list of articles yielded by searches includes subscales and sample items from each measure/article. These allow for a snapshot of how each measure or its authors have defined the constructs being assessed.

Future directions for measurement of empathy and compassion should consider incorporating advances in measurement and technology, and strive to bring together two or more assessment methods such as self-report, peer or patient reports, expert observation, implicit tasks, and biomarkers/physiological data to provide a more well-rounded picture of compassion and empathy. Innovations such as voice analysis and automated facial expression recognition may hold promise. Brief measures dispersed across multiple time points such as ecological momentary assessment and daily experience sampling may be useful. In conjunction with mobile technology and wearables, artificial intelligence and machine-learning data processing, could facilitate these formerly labor and time-intensive assessment methods.

Supporting information

S1 table. measure populations and psychometric assessments..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297099.s001

S2 Table. Measures with 8+ psychometric assessments.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297099.s002

S3 Table. Measures of compassion and empathy.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297099.s003

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Omar Shaker for his work to create the online interactive data visualization.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- PubMed/NCBI

- 6. Hart S, Hodson VK. The compassionate classroom: Relationship based teaching and learning. 1st ed. PuddleDancer Press; 2004.

- 27. Gilbert P. Compassion focused therapy: Distinctive features. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2010.

- 36. Eisenberg N, Eggum ND. Empathic responding: Sympathy and personal distress. In: Decety J, Ickes W, editors. The social neuroscience of empathy [Internet]. The MIT Press; 2009. Chapter 6. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9780262012973.003.0007

- 45. Covidence Systematic Review Software [software]. Veritas Health Innovation. Available from: www.covidence.org .

- 49. Zhu Z, Hoon HB, Teow KL. Interactive data visualization techniques applied to healthcare decision making. In: Wang B, Li R, Perrizo W, editors. Big Data Analytics in Bioinformatics and Healthcare. IGI Global; 2015. Chapter 3. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-4666-6611-5.ch003

Cognitive and Affective Empathy Relate Differentially to Emotion Regulation

- RESEARCH ARTICLE

- Open access

- Published: 15 November 2021

- Volume 3 , pages 118–134, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Nicholas M. Thompson 1 ,

- Carien M. van Reekum 1 &

- Bhismadev Chakrabarti 1

14k Accesses

15 Citations

39 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The constructs of empathy (i.e., understanding and/or sharing another’s emotion) and emotion regulation (i.e., the processes by which one manages emotions) have largely been studied in relative isolation of one another. To better understand the interrelationships between their various component processes, this manuscript reports two studies that examined the relationship between empathy and emotion regulation using a combination of self-report and task measures. In study 1 ( N = 137), trait cognitive empathy and affective empathy were found to share divergent relationships with self-reported emotion dysregulation. Trait emotion dysregulation was negatively related to cognitive empathy but did not show a significant relationship with affective empathy. In the second study ( N = 92), the magnitude of emotion interference effects (i.e., the extent to which inhibitory control was impacted by emotional relative to neutral stimuli) in variants of a Go/NoGo and Stroop task were used as proxy measures of implicit emotion regulation abilities. Trait cognitive and affective empathy were differentially related to both task metrics. Higher affective empathy was associated with increased emotional interference in the Emotional Go/NoGo task; no such relationship was observed for trait cognitive empathy. In the Emotional Stroop task, higher cognitive empathy was associated with reduced emotional interference; no such relationship was observed for affective empathy. Together, these studies demonstrate that greater cognitive empathy was broadly associated with improved emotion regulation abilities, while greater affective empathy was typically associated with increased difficulties with emotion regulation. These findings point to the need for assessing the different components of empathy in psychopathological conditions marked by difficulties in emotion regulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Individual differences in emotion regulation moderate the associations between empathy and affective distress.

Philip A. Powell

Trait-level emotion regulation and emotional awareness predictors of empathic accuracy

Nathaniel S. Eckland & Tammy English

Individual differences in empathy are associated with apathy-motivation

Patricia L. Lockwood, Yuen-Siang Ang, … Molly J. Crockett

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Our social lives often rely upon the linked processes of how we manage our own emotions and respond to the emotions of others. Yet, until recently the constructs of empathy (i.e., understanding and/or sharing another’s emotion) and emotion regulation (i.e., the processes by which one manages emotions) have largely been studied in relative isolation of one another. Despite the growing research interest in this area, fundamental questions remain regarding the nature of the interrelationships between the various component processes that comprise empathy and emotion regulation. To address these gaps in current knowledge, this manuscript reports two studies which examined how trait empathy is associated with self-report (study 1) and task-based (study 2) measures of emotion regulation.

Empathy is commonly conceptualised as comprising two dimensions: affective empathy (the ability to share others’ emotions), and cognitive empathy (the ability to infer/ understand others’ emotional experiences; Chakrabarti & Baron-Cohen, 2006 ; Decety & Jackson, 2004 ; Singer & Lamm, 2009 ). Emotion regulation refers to the various processes that can be employed in order to influence one’s own emotions (Gross, 2015 ). A close relationship between empathy and emotion regulation has been proposed by previous theoretical accounts, including our own (e.g., Decety, 2010 ; Schipper & Peterman, 2013 ; Thompson et al., 2019 ; Zaki, 2014 ). Of the handful of empirical studies that have explored this relationship, most have focused on the moderating role of emotion regulation on the association between affective empathy and different ‘empathic outcomes’, such as empathic concern (i.e., sympathy), personal distress, and prosocial behaviours (e.g., Brethel-Haurwitz et al., 2020 ; Lockwood et al., 2014 ; Lopez-Perez & Ambrona, 2015 ; Okun et al., 2000 ). While not their primary focus, such studies provide evidence suggestive of a direct relationship between empathy and emotion regulation. For example, one’s self-reported capacity to understand others’ emotions is positively related to the habitual use of more adaptive emotion regulation strategies such as reappraisal (Lockwood et al., 2014 ; Powell, 2018 ; Tully et al., 2016 ). Similarly, self-reported perspective-taking ability (a process associated with cognitive empathy) is negatively related to trait measures of emotion dysregulation (Contardi et al., 2016 ; Eisenberg & Okun, 1996 ; Okun et al., 2000 ).

Some of this prior work suggests a potential overlap in the cognitive control processes that underlie key abilities associated with these constructs. The ability to attribute an emotional/mental state to another individual (i.e., cognitive empathy) requires various cognitive control processes, which facilitate the necessary coordination of self and other representations (e.g., Carlson et al., 2004 ; Decety & Sommerville, 2003 ; Hansen, 2011 ; Mutter et al., 2006 ). Similar cognitive control processes have been implicated in emotion regulation, where they underlie the ability to exert control over one’s affective responses and behaviours (e.g., Buhle et al., 2014 ; Hendricks & Buchanan, 2016 ; McRae et al., 2012 ; Schmeichel & Demaree, 2010 ).

While the aforementioned evidence would suggest that greater cognitive empathy may facilitate emotion regulation, there is reason to expect that increased affective empathy could in fact hinder these processes. Individuals with higher affective empathy exhibit an increased facial mimicry response to others’ emotions (Sonnby-Borgstrom, 2002 ; Dimberg et al., 2011 ), which has been shown to relate to heightened resonance with the mimicked emotion (Hatfield et al., 1993 ; Laird et al., 1994 ; Wild et al., 2001 ). Additionally, individuals with greater affective empathy may be predisposed to experience emotions with a greater intensity and/or frequency (Davis, 1983 ; Eisenberg et al., 2000 ; Rueckert et al., 2011 ; Sato et al., 2013 ). Given that emotions can have a detrimental effect on the efficiency of cognitive control processes (Hare et al., 2008 ; Tottenham et al., 2011 ), it is possible that the increased emotional reactivity associated with higher levels of affective empathy could interfere with one’s ability to engage the often demanding processes necessary for emotion regulation .

Building upon prior work, the current research adopted a multi-method approach in which we examined the relationship between empathy and emotion regulation using a combination of self-report and more objective performance-based measures. Study 1 examined how trait cognitive empathy and affective empathy are associated with self-reported difficulties with emotion regulation (i.e., emotion dysregulation). Study 2 examined how the same trait empathy measure relates to task metrics that index emotion regulation abilities. Based on the findings discussed above, it was predicted that higher cognitive empathy would be associated with improved emotion regulation, whereas the opposite relationship would be observed for affective empathy.

Various abilities should be taken into account when considering an individual’s capacity for emotion regulation, including (1) awareness/understanding of one’s emotions, (2) the capacity to select and implement appropriate regulation strategies to manage emotions across diverse contexts, and (3) the ability to monitor the extent to which regulatory efforts successfully generate the desired modulation of emotion (Bonanno & Burton, 2013 ; Gohm & Clore, 2002 ; Gratz & Roemer, 2004 ; Gross, 2015 ; Koole et al., 2015 ). In this first study, we examined how trait cognitive empathy and affective empathy are related to a self-report measure of emotion regulation that assesses difficulties with emotion regulation across each of the abilities highlighted above (Kaufman et al., 2016 ). We predicted that self-reported emotion dysregulation would be negatively related to trait cognitive empathy but show a positive relationship with trait affective empathy.

Participants

An a priori sample size estimation was conducted using G*power 3.1 (Faul et al., 2007 ). Based on an expected correlation coefficient of ~ 0.3 (Contardi et al., 2016 ; Lockwood et al., 2014 ), a minimum sample of 67 was required to detect such effects at an alpha level of p = 0.05, with a power of 0.80. To account for the potential of data loss due to incomplete responses in the online survey, we aimed to collect a sample of approximately N = 100. A sample of 137 participants (101 female), with a mean age (± SD) of 20.6 years (± 3.01), was recruited from the University of Reading campus via the school of psychology research panel. Questionnaires were completed online and participants were awarded course credit for participation. Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Reading research ethics committee. This study was conducted as part of a larger project and included an additional questionnaire measure of emotion regulation (the ERQ; Gross & John, 2003 ), the data from which are not reported here.

Trait empathy was measured using the Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy (QCAE; Reniers et al., 2011 ). The QCAE is a 31-item self-report questionnaire assessing respondents’ capacity to understand and resonate with the emotions of others. It comprises five subscales which track onto the two dimensions of empathy (cognitive and affective). The cognitive empathy dimension assesses one’s propensity to take another’s perspective and accurately infer their state (e.g., “When I am upset at someone, I usually try to ‘put myself in his shoes’ for a while”; “I can sense if I am intruding, even if the other person does not tell me”). The affective empathy dimension comprises items assessing respondents’ tendency to resonate with others’ emotions (e.g., “I am happy when I am with a cheerful group and sad when the others are glum”; “It affects me very much when one of my friends seems upset”). Participants rate their response to each item using a 4-point scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”; higher values reflect greater trait empathy. Cronbach’s alpha was high for both empathy dimensions (α Cognitive empathy = 0.88; α Affective empathy = 0.82). The cognitive and affective subscales of the QCAE were positively correlated, rho (135) = 0.42 (CI 95% [0.27, 0.55]), p < 0.001.

Emotion Dysregulation

Trait emotion dysregulation was measured using the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation-short form (DERS-SF; Kaufman et al., 2016 ). The DERS-SF (henceforth, DERS) is an 18-item questionnaire assessing difficulties in six aspects of emotion regulation: (1) awareness of emotions (awareness), (2) clarity/understanding of emotions (clarity), (3) acceptance of emotions (non-acceptance), (4) capacity to maintain goal-directed behaviours in emotional situations (goals), (5) ability to exert control over one’s emotional impulses (impulse), and (6) ability to effectively manage one’s emotional responses (strategies). Respondents report the frequency with which they experience difficulties in these aspects of emotion regulation using a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 = almost never (0–10% of the time) and 5 = almost always (91–100% of the time); higher ratings reflect increased emotion dysregulation. The sum of the six subscales provides a total score reflecting overall levels of emotion dysregulation (DERS-Total). Within this sample, the DERS-Total metric and each subscale thereof demonstrated acceptable to high Cronbach’s alpha: α DERS-Total = 0.91; α Awareness = 0.79; α Clarity = 0.86; α Acceptance = 0.82; α Goals = 0.89; α Impulse = 0.89; α Strategies = 0.83.

Data Reduction and Analysis

The relationship between empathy and emotion dysregulation was examined using bivariate correlations. Normality of each variable was assessed using Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. As some variable distributions showed significant deviation from normality, Spearman’s rho is reported for all correlations in order to enable their direct comparability. All correlations are reported as two-tailed, with an alpha level of p = 0.05. Data were analysed using SPSS version 27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA) and Jamovi version 1.6 ( https://www.jamovi.org ). To ensure that the observed results were not unduly influenced by a small number of outlier cases, the results following the removal of univariate and bivariate outliers are reported in supplementary material ( S1 ).

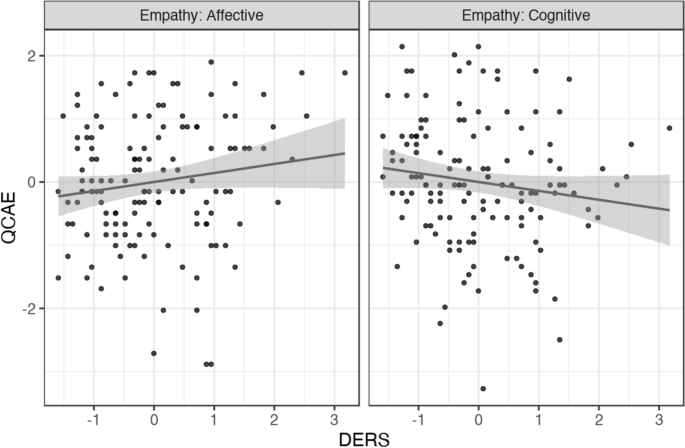

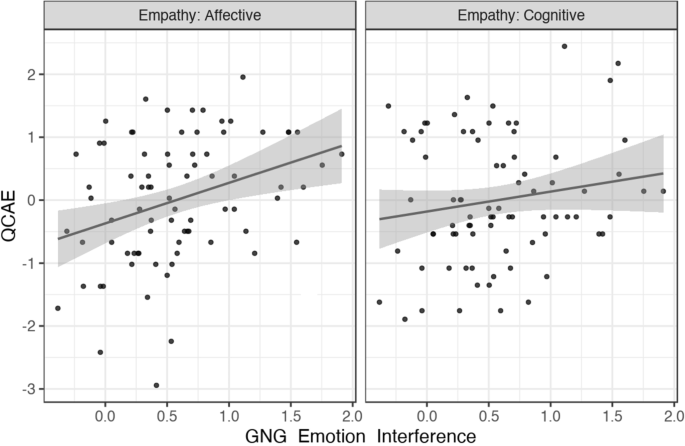

Descriptive statistics for all variables used in the correlation analysis are reported in Table 1 (descriptive statistics for the DERS subscales are reported in supplementary material, S2 ). Affective empathy was not significantly correlated with DERS-Total, rho (135) = 0.13 (CI 95% [− 0.04, 0.29]), p = 0.14. Cognitive empathy showed a small significant negative correlation with DERS-Total, rho (135) = − 0.18 (CI 95% [− 0.34, − 0.01]), p = 0.04. These two correlations were significantly different from each other, Steiger’s Z = − 3.36, p < 0.001 (Fig. 1 ).

Scatterplot showing the relationship between Z -transformed trait cognitive/affective empathy (QCAE) and Z -transformed emotion dysregulation (DERS-Total). Affective empathy (left panel) was not significantly correlated with DERS-Total; cognitive empathy (right panel) was negatively correlated with DERS-Total

To better understand the relationship between cognitive/affective empathy and trait emotion dysregulation, we conducted exploratory correlations testing the relationship between both empathy dimensions and each subscale of the DERS. Cognitive empathy was significantly negatively related to the awareness subscale and showed a trend-level negative relationship with the impulse control subscale. Affective empathy was significantly positively related to the goals and strategies subscales and showed a trend-level positive relationship with non-acceptance. There was also a significant negative relationship between affective empathy and the awareness subscale. Steiger’s tests demonstrated that, with the exception of the clarity subscale, the cognitive and affective dimensions of empathy showed significantly different relationships with each subscale of the DERS. False Discovery Rate (FDR)–corrected correlation results and associated Z statistics are reported in Table 2 .

The results of study 1 highlight several points of divergence between trait cognitive empathy and affective empathy in terms of their relationship with self-reported emotion dysregulation. Cognitive empathy was more negatively related to difficulties with emotional awareness than affective empathy. Significant differences between these empathy components were also observed in relation to other subscales of DERS measuring difficulties with impulse control (impulse), maintaining focus on goal-directed behaviours (goals), and managing/accepting one’s emotions (strategies and non-acceptance, respectively). Many of these abilities are thought to be dependent upon more ‘implicit’ forms of emotion regulation, which refer to regulatory processes that can be enacted with little or no reliance upon conscious effortful control or monitoring (Gyurak et al., 2011 ; Mauss et al., 2007 ). Consequently, in this second study, we examined how these same measures of trait cognitive and affective empathy are associated with performance on two tasks that assess implicit emotion regulation abilities.

Prior work has highlighted the deleterious impact of emotional stimuli on cognitive control processes (e.g., Jasinska et al., 2012 ; Padmala et al., 2011 ; Reeck & Egner, 2011 ; Tottenham et al., 2011 ). While definitions of emotion regulation often emphasise more deliberate and effortful processes, regulating the early influence of emotions on cognitive control is largely dependent upon more implicit processes, which also play a key role in emotion regulation in daily life (Gyurak et al., 2011 ; Mauss et al., 2007 ).

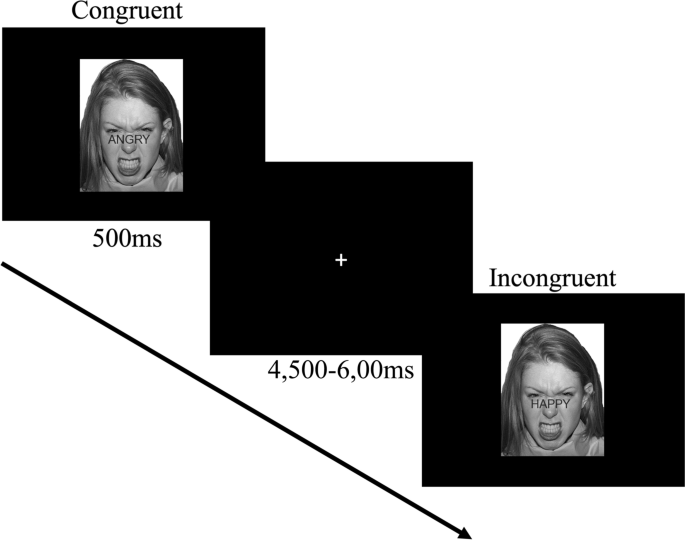

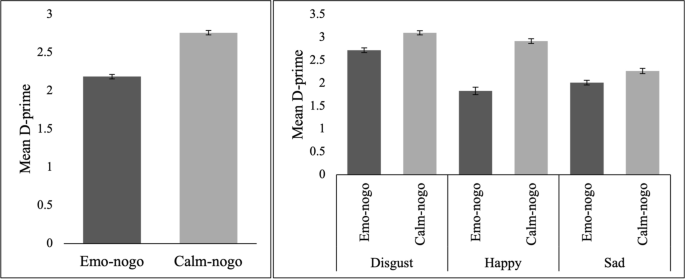

Emotional variants of well-known cognitive control tasks are commonly used to assess attentional biases and the interaction between emotion and cognition. Such tasks have also proven useful for assessing more implicit emotion regulation abilities (see review by Buhle et al., 2010 ). In these paradigms, performance is compared across conditions in which distracting stimuli are either emotional or non-emotional, thereby indexing the extent to which performance is disrupted by emotional information (a phenomenon henceforth referred to as ‘emotion interference effects’). The assumption underlying this approach is that individuals with better implicit emotion regulation abilities will exhibit a reduced magnitude of emotion interference effects relative to their less well-regulated counterparts (Etkin et al., 2010 ; Koole & Rothermund, 2011 ; Zhang & Lu, 2012 ). In the present study, we used two paradigms that have been used in previous research to assess implicit emotion regulation: the emotional go/nogo and the emotional Stroop (henceforth Emo-GNG and Emo-Stroop, respectively). While the term implicit is sometimes used in reference to regulation paradigms wherein the processing of emotional information is entirely irrelevant to task performance (Zhang & Lu, 2012 ), we use the term slightly more broadly to refer to tasks in which regulatory processes may be initiated without any explicit instruction/intention (Yiend et al., 2008 ).

Prior studies using the Emo-GNG have demonstrated that emotional nogo stimuli tend to induce more commission errors (i.e., false alarms) relative to neutral nogo stimuli (Hare et al., 2005 , 2008 ; Tottenham et al., 2011 ; Zhang et al., 2016 ). Similarly, numerous emotional variants of the Stroop task (Stroop, 1935 ) have demonstrated the heightened potential for emotional stimuli to disrupt cognitive control processes relative to neutral stimuli, indexed by increased response times (RT) and/or decreased accuracy (Etkin et al., 2006 ; Haas et al., 2006 ; Stenberg et al., 1998 ). These emotion interference effects are often exhibited to a greater extent, or in some cases, only, in individuals with high trait anxiety (e.g., Kalanthroff et al., 2016 ; Richards et al., 1992 ; see also Buhle et al., 2010 ).

One prior study found that improved performance on a task measuring cognitive empathy–related processes was associated with a greater ability to ignore irrelevant distractors in an Emo-Stroop (Bradford, 2015 ). However, this study did not test the relationship between affective empathy and the Emo-Stroop. Additionally, while there is some evidence to suggest that affective empathy is associated with a heightened sensitivity to emotional stimuli (such as in attentional blink tasks, e.g., Kanske et al., 2013 ), prior work has failed to find any direct evidence for a relationship between affective empathy and interference effects in Emo-Stroop tasks (Hofelich & Preston, 2012 ).

It is important to note that the trait empathy measures used in these prior studies have been criticised for conflating the cognitive and affective dimensions of empathy with dissociable constructs, such as sympathy (Reniers et al., 2011 ). Furthermore, many studies that have used Emo-Stroop variants lacked a neutral control condition, which makes it difficult to determine the extent to which any RT difference between the congruent and incongruent conditions is driven by emotion interference effects (on incongruent trials) or emotion facilitation effects (on congruent trials). Accordingly, the current study includes a neutral control condition to enable the examination of emotional interference independently of facilitation. As prior work has demonstrated the potential for both positively and negatively valenced stimuli to attract attention and disrupt cognitive processing (e.g., Hare et al., 2005 ; Pratto & John, 1991 ), both tasks included positive and negative emotional facial expressions in order to increase the generalizability of the results.

It was expected that emotional stimuli would disrupt inhibitory control processes, as indexed by decreased performance relative to neutral stimuli (i.e., increased emotion interference effects). Based on the literature discussed in the general introduction, it was predicted that trait cognitive and affective empathy would be differentially related to the magnitude of these emotion interference effects. Given evidence suggestive of overlap in the cognitive control processes underlying abilities related to cognitive empathy and emotion regulation (e.g., Buhle et al., 2014 ; Decety & Sommerville, 2003 ; Hansen, 2011 ; Hendricks & Buchanan, 2016 ), it was predicted that cognitive empathy would be negatively related to the magnitude of emotion interference effects. Conversely, based on evidence that affective empathy is positively associated with increased spontaneous mimicry and emotional reactivity (Davis, 1983 ; Eisenberg et al., 2000 ; Hatfield et al., 1993 ; Laird et al., 1994 ; Wild et al., 2001 ), it was predicted that trait affective empathy would show a positive relationship with the magnitude of emotion interference effects.

As in study 1, an a priori sample size estimation was conducted using G*power 3.1 (Faul et al., 2007 ). Based on an expected correlation coefficient of ~ 0.3 (Contardi et al., 2016 ; Lockwood et al., 2014 ), a minimum sample of 67 was required to detect such effects at an alpha level of p = 0.05, with a power of 0.80. To account for potential data loss due to non-responders and data outliers, we sought to obtain a sample of approximately N = 100. Ninety-two right-handed participants (78 females) were recruited from the undergraduate psychology population at the University of Reading. All participants were recruited through the online research panel and received course credit for participation. The mean age (± SD) was 19.86 (± 2.39). The two tasks were administered as part of a lab session, with the order of task completion counterbalanced. This study was conducted as part of a larger project and included an additional questionnaire measure of emotion regulation (the ERQ; Gross & John, 2003 ), the data from which are not reported here.

Following data quality checks (see “Data Reduction and Analysis” for details), thirteen participants’ data were removed from the Emo-GNG, and nine participants’ data were removed from the Emo-Stroop, leaving a final sample of N = 79 (71 females; mean age ± SD = 19.95 ± 2.55) and N = 83 (69 female; mean age ± SD = 19.93 ± 2.50) for these two tasks, respectively. The QCAE was completed online; Cronbach’s alpha was high for both QCAE subscales (α Affective Empathy = 0.79; α Cognitive Empathy = 0.88). Following case removals based on the Emo-GNG and Emo-Stroop task data, the cognitive and affective subscales of the QCAE were positively correlated in both instances, rho (77) = 0.38 (CI 95% [0.18, 0.56]), p < 0.001; rho (81) = 0.36 (CI 95% [0.15, 0.53]), p = 0.001.

Materials and Procedure

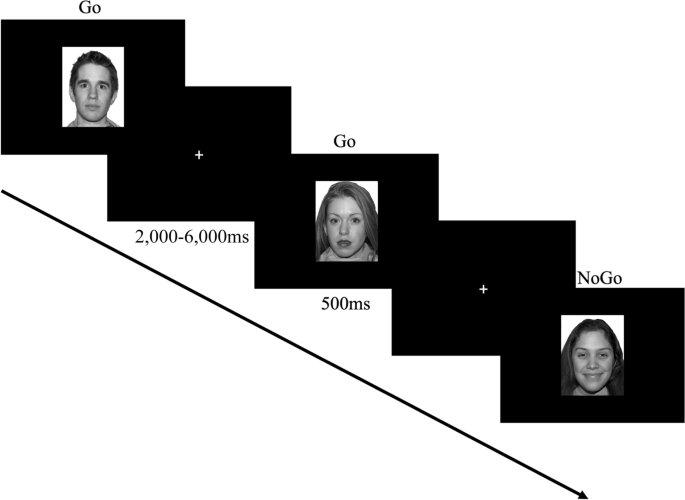

Face stimuli were taken from the Nimstim Face Stimulus Set (Tottenham et al., 2009 ; www.macbrain.org ) and comprised photographs of six female (identity numbers: 1, 3, 6, 8, 9, 10) and six male (identity numbers: 21, 22, 23, 24, 28, 34) actors. Different male and female actors displaying fearful expressions were used for the practice block. Each image was converted to greyscale with the dimensions 256 × 329 pixels. The facial expressions included in the task were the closed-mouth versions of happy, sad, disgusted, and calm (i.e., neutral). These emotions were selected in order to include stimuli depicting expressions of positive, neutral, and negative valence, which were likely to differ in terms of the approach/avoid tendencies they elicit (Seidel et al., 2010 ; Tottenham et al., 2011 ). The same actors were used for each facial expression, and the frequency with which each stimulus was presented was balanced across conditions.

The Emo-GNG task lasted approximately 25 min. This included a practice block comprising 12 trials, followed by 6 experimental blocks each comprising 48 trials. Upon completion of a block, a holding screen was presented until participants pressed a key to continue; the order in which the blocks were completed was randomised. In each block, an emotional target (go) or distractor (nogo) was always paired with a calm target/distractor, such that if an emotional face was the go stimulus, a calm face was the nogo stimulus, and vice versa. Each block contained one emotion type only, alongside the neutral (calm) expressions. At the start of each block, participants were told which emotion represented the go stimulus and were instructed to respond to these targets by pressing ‘0’ on the keypad with their right index finger. Participants were not told what the nogo expression would be but were instructed to respond as quickly as possible (while maintaining accuracy) to the target expression and to withhold responding for any other expression (full verbatim instructions for the Emo-GNG task are presented in supplementary material, S3 ).