An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Public Health Nutr

- v.22(9); 2019 Jun

- PMC10260889

A systematic review of food pantry-based interventions in the USA

1 Guangzhou Sport University, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510620, People’s Republic of China

2 Department of Kinesiology and Community Health, College of Applied Health Sciences, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, Champaign, IL 61820, USA

3 Brown School, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO 63130, USA

Junjie Wang

4 Department of Physical Education, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, People’s Republic of China

5 Soka University of America, Aliso Viejo, CA, USA

6 Beijing Sport University, Beijing, People’s Republic of China

Emily Loehmer

7 University of Illinois Extension, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, Champaign, IL, USA

Jennifer McCaffrey

Food pantries play a critical role in combating food insecurity. The objective of the present work was to systematically review and synthesize scientific evidence regarding the effectiveness of food pantry-based interventions in the USA.

Keyword/reference search was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, Cochrane Library and CINAHL for peer-reviewed articles published until May 2018 that met the following criteria. Setting: food pantry and/or food bank in the USA; study design: randomized controlled trial (RCT) or pre–post study; outcomes: diet-related outcomes (e.g. nutrition knowledge, food choice, food security, diet quality); study subjects: food pantry/bank clients.

Fourteen articles evaluating twelve distinct interventions identified from the keyword/reference search met the eligibility criteria and were included in the review. Five were RCT and the remaining seven were pre–post studies. All studies found that food pantry-based interventions were effective in improving participants’ diet-related outcomes. In particular, the nutrition education interventions and the client-choice intervention enhanced participants’ nutrition knowledge, cooking skills, food security status and fresh produce intake. The food display intervention helped pantry clients select healthier food items. The diabetes management intervention reduced participants’ glycaemic level.

Conclusions

Food pantry-based interventions were found to be effective in improving participants’ diet-related outcomes. Interventions were modest in scale and usually short in follow-up duration. Future studies are warranted to address the challenges of conducting interventions in food pantries, such as shortage in personnel and resources, to ensure intervention sustainability and long-term effectiveness.

Food insecurity, a lack of reliable access to a sufficient quantity of affordable, nutritious food, impacts over one-eighth of American households, with highest rates among households with incomes below the federal poverty level ( 1 ) . Food insecurity is associated with poor dietary quality and elevated disease risks ( 2 , 3 ) . Food banks in the USA typically operate as warehouses that store a large quantity and variety of food items to be distributed by smaller front-line agencies, called food pantries, which directly serve the end users free of charge. Food banks and food pantries in the USA distribute free grocery items to over 46·5 million Americans in need annually ( 4 , 5 ) . Estimations of food insecurity among pantry clients in the USA range from 50 to 84% ( 5 – 7 ) . Food pantries are often used to augment the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits ( 7 , 8 ) . However, some clients use food pantries as their primary or sole food source, partially due to SNAP ineligibility ( 9 ) . Food pantries play a critical role in addressing the needs of Americans at high risk of food insecurity ( 10 ) .

Besides emergency food provision, food pantries may serve as a natural setting and focal point where additional services can be delivered to improve the diet and health status of the highly vulnerable client population. Previous reviews on food pantries largely focused on cross-sectional studies that assessed the nutritional values of foods provided, service types and quality, and client characteristics (e.g. food security status, dietary intake, malnutrition status, health or disease status, and frequencies or reasons for food pantry use) ( 6 , 11 , 12 ) . One prospective review intends to survey outcomes of disease prevention and management interventions in food pantries, but the review does not assess health behaviour (e.g. food choice) and results have yet to be reported ( 13 ) . The purpose of the present study was to systematically review and synthesize scientific evidence regarding the effectiveness of food pantry-based interventions on diet-related outcomes in the USA. We focused on food pantries in the USA because the types and ways of operation of food banks and pantries differ substantially across countries, and they are also subject to different government regulations and serve diverse populations.

The systematic review was reported in accordance with the PRIMSA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement ( 14 ) . Analysis was conducted in May 2018.

Data sources

A keyword search was performed in five electronic bibliographic databases: (i) PubMed; (ii) Web of Science; (iii) Scopus; (iv) Cochrane Library; and (v) Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL). The search algorithm included all the following keywords: ‘food pantry’, ‘food pantries’, ‘food bank’, ‘food banks’, ‘food shelf’, ‘food shelves’, ‘food cupboard’, ‘food cupboards’ and ‘food assistance’. The MeSH (medical subject heading) term ‘food assistance’ was included in the PubMed search. All keywords in the PubMed were searched with the ‘(All fields)’ tag, which are processed using Automatic Term Mapping ( 15 ) . The Appendix documents the search algorithm in PubMed as an example. The search function ‘TS=Topic’ was used in Web of Science, which launches a search for topic terms in the fields of title, abstract, keywords and Keywords Plus® ( 16 ) . Titles and abstracts of the articles identified through the keyword search were screened against the study selection criteria. Potentially relevant articles were retrieved for evaluation of the full text. Two reviewers, J.W. and J.S., independently conducted title and abstract screening and identified potentially relevant articles. Inter-rater agreement was assessed using the Cohen’s kappa ( κ =0·82). Discrepancies were resolved through face-to-face discussions between R.A., J.W. and J.S.

A reference list search (i.e. backward reference search) and a cited reference search (i.e. forward reference search) were conducted based on the full-text articles meeting the study selection criteria that were identified from the keyword search. Articles identified from the backward and forward reference search were further screened and evaluated using the same study selection criteria. The reference search was repeated on newly identified articles until no additional relevant article was found.

Study selection

Studies that met all of the following criteria were included in the review. (i) Setting: food pantry and/or food bank in the USA; (ii) exposure: any intervention that addresses food pantry clients’ diet-related outcomes (e.g. nutrition knowledge, food choice, food security, diet quality), except for the daily work routine of a food pantry (i.e. food service) or food bank (i.e. food storage and distribution); (iii) study design: randomized controlled trial (RCT) or pre–post study; (iv) study subjects: food pantry/bank clients; (v) article type: peer-reviewed publication; (vi) time window of search: from the inception of an electronic bibliographic database to 28 May 2018; and (vii) language: article written in English.

Studies that met any of the following criteria were excluded from the review: (i) food pantry/bank-related observational studies; (ii) non-peer-reviewed articles; (iii) articles not written in English; or (iv) letters, editorials, study/review protocols or review articles.

Data extraction

A standardized data extraction form was used to collect the following methodological and outcome variables from each included study: authors, publication year, study design, sample size, age range, percentage of women, duration of follow-up, setting, intervention type, intervention components, measures, outcomes, statistical models, covariates adjusted for and estimated intervention effectiveness.

Data synthesis

A tabulation of extracted data revealed that no two interventions provided a quantitative estimate for the same outcome measure. This precluded a meta-analysis. We narratively summarized the common themes and findings of the included studies.

Study quality assessment

We used the National Institutes of Health’s Quality Assessment Tool of Controlled Intervention Studies to assess the quality of each included study ( 17 ) . This assessment tool rates each study based on fourteen criteria. For each criterion, a score of 1 was assigned if ‘yes’ was the response, whereas a score of 0 was assigned otherwise (i.e. an answer of ‘no’, ‘not applicable’, ‘not reported’ or ‘cannot determine’). Study quality assessment helped measure the strength of scientific evidence but was not used to determine the inclusion of studies.

Figure 1 shows the study selection flowchart. We identified 3051 articles in total by the keyword search, including 610 articles from PubMed, 603 articles from Web of Science, 1412 from Scopus, 354 articles from CINAHL and seventy-two articles from Cochrane Library. After removing duplicates, 2446 unique articles entered title and abstract screening, of which 2436 articles were excluded. The full texts of the remaining ten articles were reviewed against the study selection criteria ( 18 – 27 ) and two studies were excluded because they were other types of interventions (i.e. smoking cessation and medical referral) rather than diet-related interventions ( 19 , 23 ) . A forward and backward reference search was conducted based on these eight articles and six new articles were identified that met the study selection criteria ( 28 – 33 ) . Therefore, these fourteen articles consist of the final pool of studies included in the review ( 18 , 20 – 22 , 24 – 33 ) .

Flowchart showing study selection for the current review of food pantry-based interventions in the USA

Summary of the selected studies

Table 1 summarizes the basic characteristics of the fourteen articles evaluating twelve distinct interventions included in the review. All of them were published within the past 12 years. Seven studies adopted a pre–post study design and five adopted an RCT study design. Sample size varied substantially across studies. Two articles had a sample size between forty and 100 participants ( 20 , 24 ) , seven had a sample size between 100 and 500 participants ( 18 , 22 , 25 , 29 – 32 ) , three articles had a sample size between 500 and 1000 participants ( 21 , 26 , 28 ) , one had a sample size between 1000 and 2000 participants ( 27 ) , whereas the remaining one recruited 375 families ( 33 ) . The mean and median sample sizes were 429 and 236, respectively, except for one study that did not report its sample size in detail ( 33 ) . All studies but one ( 33 ) focused exclusively on adults aged 18 years or above. Among the nine articles that reported sex distribution, women accounted for over half (53–100%) of the analytic sample ( 20 – 22 , 24 , 25 , 28 , 29 , 31 , 32 ) . Four articles recruited participants with diabetes ( 21 , 22 , 25 , 28 ) , three articles recruited participants with hypertension ( 22 , 25 , 28 ) , two articles recruited participants with obesity ( 22 , 25 ) and one article recruited participants with heart disease ( 28 ) .

Basic characteristics of the studies included in the current review of food pantry-based interventions in the USA

RCT, randomized controlled trial; M, male; F, female.

Table 2 summarizes intervention type, intervention components, outcome measures, statistical models and estimated intervention effectiveness on diet-related outcomes. Nutrition education ( n 9) was the most common type of intervention ( 20 , 24 – 28 , 31 – 33 ) , followed by client-choice intervention (called ‘Freshplace’; n 3) ( 22 , 25 , 29 ) , food display intervention ( n 1) ( 18 ) and diabetes management intervention ( n 1) ( 21 ) . The nutrition education interventions included nutrition knowledge dissemination (e.g. healthy eating plate, nutrition facts label use, nutritional implications of different fat types, relationship between nutrition and health, and healthy recipes using fresh produce) ( 20 , 24 – 28 , 31 – 33 ) and cooking demonstrations ( 24 , 27 ) . In the nutrition education interventions, extension staff and local volunteers provided education pertaining to various nutrition-related facts and knowledge (e.g. read food labels, understand different types of fats) for low-income families ( 20 ) . Study investigators created a software to provide messages regarding tailored recipes and food-use tips for pantry clients ( 26 , 33 ) . Food pantry staff were trained about the relationship between nutrition and chronic diseases in order to provide healthier pantry food options ( 28 ) . A food safety-certified graduate assistant served whole-grain dish along with the recipe, informed clients regarding the whole-grain ingredients in the recipe and asked them to make half their grains whole on a daily basis ( 31 ) . In the cooking demonstration, study investigators provided cooking classes for low-income people who would like to try new recipes ( 22 ) . The staff did a cooking demonstration to show how one could prepare healthy recipes using the fresh produce offered and distributed the recipes to pantry clients ( 27 ) . The client-choice intervention (‘Freshplace’) included three major components: (i) participants chose their own foods (primarily fresh and perishable food items); (ii) met with a project manager once per month to develop and track personal goals for becoming food secure and self-sufficient; and (iii) received services tailored to their individual needs (e.g. a six-week cooking workshop) ( 22 , 25 , 29 ) . In the food display intervention, researchers manipulated the display of a targeted product (i.e. protein bar) in a food pantry – placing the product in the front or the back of the category line and presenting the product in its original box or unboxed – with the goal of encouraging the selection of targeted foods through ‘nudges’ but without restricting choices ( 1 ) . In the diabetes management intervention, food pantry clients with diabetes were provided with diabetes-appropriate foods, blood sugar monitoring, primary care referral and self-management support by project personnel who were registered dietitians or certified diabetes educators ( 21 ) .

Intervention components, measures, statistical models and estimated effects on diet and health outcomes of the studies included in the current review of food pantry-based interventions in the USA

HbA1c, glycated Hb.

Two of the fourteen articles adopted one or more biometric outcome measures (e.g. BMI calculated from measured height and weight, glycaemic level and blood pressure) ( 21 , 24 ) , and the remaining twelve articles adopted subjective outcome measures using questionnaires ( n 5) ( 22 , 25 , 28 , 29 , 32 ) , face-to-face or telephone-based interviews ( n 5, including a 24 h dietary recall ( 20 ) ) ( 20 , 26 , 30 , 31 , 33 ) , staff registration ( n 1) ( 27 ) and researchers’ observation ( n 1) ( 18 ) . One of the fourteen articles adopted both biometric and subjective measures (e.g. interview and biometric measures) ( 24 ) . Statistical tests and models applied included the t test, χ 2 test, Cronbach α test, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, linear regression, logistic regression, ANOVA, hierarchical linear modelling and generalized linear mixed model.

All twelve studies included in the review found improvements in diet, cooking skills, food security, nutrition knowledge and/or health outcomes attributable to food pantry-based interventions. Among these studies, four reported positive qualitative outcomes linking the food pantry-based intervention to improved cooking skills ( 30 ) , medical care ( 27 ) , nutrition knowledge ( 28 ) and/or dietary quality among study participants ( 33 ) . The remaining eight studies that applied statistical tests and models reported a statistically significant positive association between the food pantry-based intervention and diet quality, cooking skills, food security, nutrition knowledge and/or health outcomes ( 18 , 20 – 22 , 24 – 26 , 29 , 31 , 32 ) . The nutrition education interventions and the client-choice intervention were found to improve participants’ nutrition knowledge, cooking skills, food security status and fresh produce intake ( 20 , 22 , 24 – 29 , 31 – 33 ) . The food display intervention was found to significantly help pantry clients select healthier food items ( 18 ) . The diabetes management intervention was found to significantly help participants better control their glycaemic level ( 21 ) . More specifically, the glycaemic control intervention was more effective among the subset of participants with glycated Hb (HbA1c) ≥7·5% at baseline (i.e. improved by 0·48 percentage points) than those with diabetes in general (i.e. improved by 0·15 percentage points) ( 21 ) . The only study that assessed BMI reported a reduction in BMI among food pantry clients following a six-week cooking programme of plant-based recipes, but the estimated intervention effect was only marginally significant ( P =0·05) ( 24 ) .

Table 3 reports criterion-specific ratings from the study quality assessment. All fourteen articles included in the review clearly stated the research question/objective, clearly specified and defined the study population, recruited subjects from the same or similar populations during the same time period, pre-specified and uniformly applied inclusion and exclusion criteria to all participants, had a reasonably long follow-up period that was sufficient for changes in outcomes to be observed, and implemented valid and reliable exposure and outcome measures. On the other hand, none of them examined the dose–response effect of food pantry-based interventions, and few justified their sample size and/or conducted a power calculation ( 18 , 26 ) . Three articles had the outcome assessors blinded to the exposure status of the participants ( 18 , 21 , 24 ) . Four articles had an attrition rate less than 20% ( 18 , 22 , 25 , 26 ) . Seven articles had a participation rate above 50% ( 22 , 25 , 26 , 29 – 32 ) , assessed the exposures more than once during the study period ( 20 – 22 , 24 – 26 , 29 ) , and measured and statistically adjusted key potential confounding variables for their impact on the relationship between exposures and outcomes ( 18 , 21 , 22 , 26 , 29 , 31 , 32 ) .

Quality assessment * of the studies included in the current review of food pantry-based interventions in the USA

The present study systematically reviewed scientific evidence regarding food pantry-based interventions on participants’ diet-related outcomes in the USA. A total of fourteen articles evaluating twelve distinct interventions were identified. Seven studies adopted a pre–post study design and the remaining five adopted an RCT design. Nine studies focused on nutrition education interventions, one study focused on client-choice intervention, one study focused on food display intervention and the remaining one focused on diabetes management intervention. The review findings demonstrated the feasibility and preliminary effectiveness of these food pantry-based interventions in producing a wide range of positive outcomes such as improved nutrition and health literacy, food security, cooking skills, healthy food choices and intake, diabetes management and access to community resources.

Since the current review was conducted, Seligman et al . (2018) ( 34 ) reported that food banks positively impacted food security, food stability and fruit/vegetable intake among participants. However, no differences in self-management (i.e. depressive symptoms, diabetes distress, self-care, hypoglycaemia and self-efficacy) or HbA1c were identified. On the one hand, findings from Seligman et al . (2018) ( 34 ) help strengthen the evidence regarding the effectiveness of food pantry-based interventions on food security and dietary quality. On the other hand, the null findings contradicted previous positive findings pertaining to improved HbA1c reported in Seligman et al . (2015) ( 21 ) . Future studies should be conducted to assess this discrepancy.

Despite these initially promising results, food pantry-based interventions also face multiple challenges. Largely dependent upon donations and volunteer work, food pantries may have limited resources to provide additional services to clients in need ( 6 , 11 , 12 , 35 ) . Modifications of health behaviours and outcomes often require moderate to intensive interventions that last for a sustained period, but the shortage in personnel and funding may threaten the sustainability and suitability of food pantry-based interventions. Language and cultural barriers, lack of mutual trust and social stigma may prevent clients from fully engaging in the interventions offered at food pantries ( 36 – 40 ) . This situation could be further hampered by food pantry staff’s lack of professional training in intervention delivery. A close collaboration between food pantry and health or other professionals might be the key to a successful and sustainable intervention. A potential partnership for these interventions may exist between food pantries and agencies implementing SNAP-Ed (i.e. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program–Education), who have staff that specialize in assisting organizations serving low-income populations ( 41 ) . SNAP-Ed implementing agencies provide free technical assistance and may help bridge the gap between pantry staff or funding shortages and the desire to implement sustained food pantry interventions.

Food insecurity is merely one of the many challenges food pantry clients face on a daily basis. Malnutrition among food pantry users has been strongly correlated with lack of shelter, access barriers to health care and other social resources, unemployment, physical and mental disability, illiteracy, substance abuse and domestic conflict ( 42 ) . Findings of the current review revealed the potential of food pantry-based interventions in addressing some of the unmet needs of pantry users, especially in the domains of food insecurity and diet quality. The remaining questions are: what else could be done to support this highly vulnerable population, and how could we sustain interventions beyond the conclusion of research funding? Emerging research has explored non-diet related interventions at the food pantry setting, such as smoking cessation and medical referral programmes ( 19 , 23 ) , in an effort to meet other needs of pantry users beyond food access. In view of the close link between food insecurity and health, Feeding America has started to promote partnerships between food pantries/banks and health-care providers ( 43 ) . As a pilot programme, a food pantry in Indiana was established in a health clinic to address the health and nutrition needs of senior patients and the neighbouring community ( 44 ) . Sustainability of an intervention is largely determined by the abundance and stability of financial resources that cover the capital and labour cost of the intervention beyond the phase of scientific research. Demonstrating the intervention effectiveness and cost-effectiveness is of importance, but it alone may not be sufficient to attract and sustain long-term investment. Building a healthy partnership with other non-profit or for-profit institutes could help sustain the intervention in the long run if that is of their common interest. The Walmart Foundation has partnered with local food banks/pantries across the nation in a joint effort to improve the quantity and quality of food in the charitable meal system ( 45 ) . Resource and cost sharing based on partnerships can also play an important role in intervention sustainability. However, two recent studies assessed the network of agencies in local communities that promote healthy eating among populations with limited resources and found that those agencies were only loosely connected ( 46 , 47 ) .

The current review serves as the first attempt to synthesize scientific evidence regarding food pantry-based interventions on participants’ diet-related outcomes in the USA. Several limitations pertaining to the review and the included studies should be noted. The majority of the selected studies used subjective outcome measures (e.g. questionnaires and face-to-face or telephone-based interviews), which are subject to recall error and social desirability bias ( 48 , 49 ) . Half of the articles adopted a pre–post study design. In the absence of randomization, their estimated intervention effects could be prone to confounding bias. Research quality varied substantially across studies. Merely two articles justified their sample size and/or conducted a power calculation. It is possible that some studies were underpowered to detect a statistically significant effect. Only four articles had an attrition rate less than 20%, which could be partially explained by the high turnover rate of food pantry clients and the difficulty in tracking them over time. All articles reported positive findings only, whereas it is possible that non-positive and/or inconclusive results were not reported or published (i.e. presence of publication and/or reporting bias). No two articles provided a quantitative effect estimate for the same type of food pantry-based intervention on the same diet-related outcome, which precluded a meta-analysis. None of the included studies assessed the dose–response effect of food pantry-based interventions. The presence of an optimal intervention intensity remains to be tested. Most studies were small in scale and it remains unclear whether some of those interventions are suitable for scaling up to accommodate the population needs. The current review only included published literature. There might be useful and relevant unpublished studies that were missed by the review. Future work could explore grey literature to see whether it could build on the findings from the current review. Biel et al . (2009) explored a collaboration model between community clinics and local food pantries to jointly address the unmet needs of low-income residents ( 27 ) . However, such partnership is uncommon. Future work should incorporate larger sample sizes and diverse participants, examine the dose–response effect of the intervention, build collaboration with other public or private entities, and design innovative interventions to address other types of unmet needs of food pantry users.

The present work systematically reviewed scientific evidence regarding food pantry-based interventions on clients’ diet-related outcomes. Fourteen articles evaluating twelve distinct interventions were identified from the keyword and reference search, including nine nutrition education interventions, a client-choice intervention, a food display intervention and a diabetes management intervention. All fourteen articles included in the review clearly stated the research question/objective, clearly specified and defined the study population, recruited subjects from the same or similar populations during the same time period, pre-specified and uniformly applied inclusion and exclusion criteria to all participants, had a reasonably long follow-up period that was sufficient for changes in outcomes to be observed, and implemented valid and reliable exposure and outcome measures. On the other hand, none of them examined the dose–response effect of food pantry-based interventions, only two justified their sample size and/or conducted a power calculation, three had the outcome assessors blinded to the exposure status of the participants and four had an attrition rate less than 20%. Findings from these studies demonstrated the feasibility and preliminary effectiveness of food pantry-based interventions in delivering a wide range of positive outcomes including improved nutrition and health literacy, food security, cooking skills, healthy food choices and intake, diabetes management and access to community resources. Future studies are warranted to address the challenges of conducting interventions in food pantries, such as shortage in personnel and resources, to ensure intervention sustainability and long-term effectiveness.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This research is partially funded by Guangzhou Sport University. Guangzhou Sport University had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare. Authorship: R.A. conceived and designed the study and wrote the manuscript. J.W. and J.L. conducted the literature review and constructed the summary tables and figures. E.L. and J.M. contributed to manuscript drafting. J.S. contributed to manuscript revision. Ethics of human subject participation: This review is non-human subject research and exempt from institutional review board review.

Search algorithm in PubMed

‘food pantry’(All Fields) OR ‘food pantries’(All Fields) OR ‘food bank’(All Fields) OR ‘food assistance’(MeSH) AND (‘humans’(MeSH Terms) AND English(lang))

The Food Bank and Food Pantries Help Food Insecure Participants Maintain Fruit and Vegetable Intake During COVID-19

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Nutrition and Food Sciences, The University of Vermont, Burlington, VT, United States.

- 2 Food Systems Program, The University of Vermont, Burlington, VT, United States.

- 3 Gund Institute for Environment, The University of Vermont, Burlington, VT, United States.

- PMID: 34422877

- PMCID: PMC8378669

- DOI: 10.3389/fnut.2021.673158

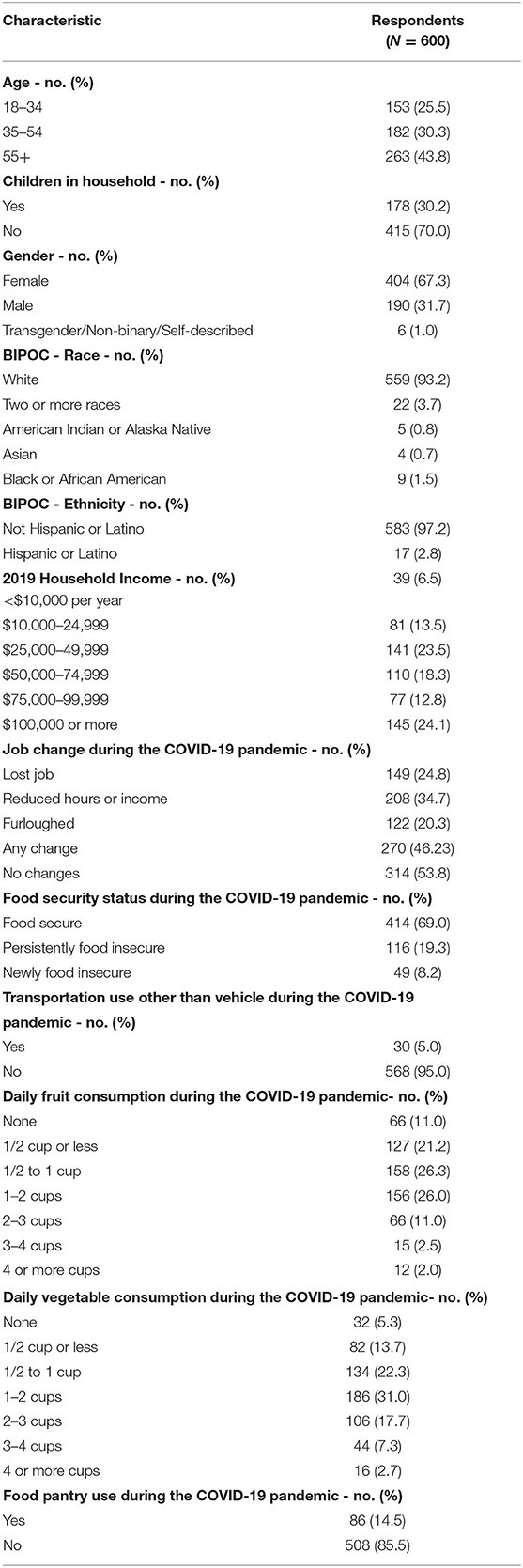

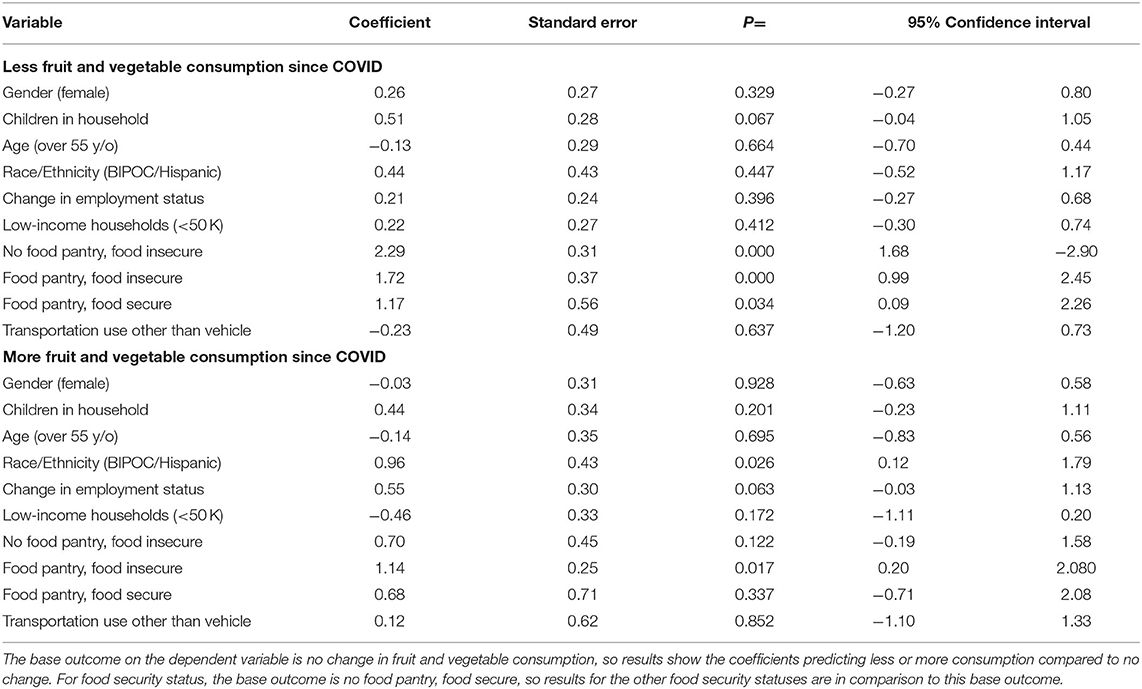

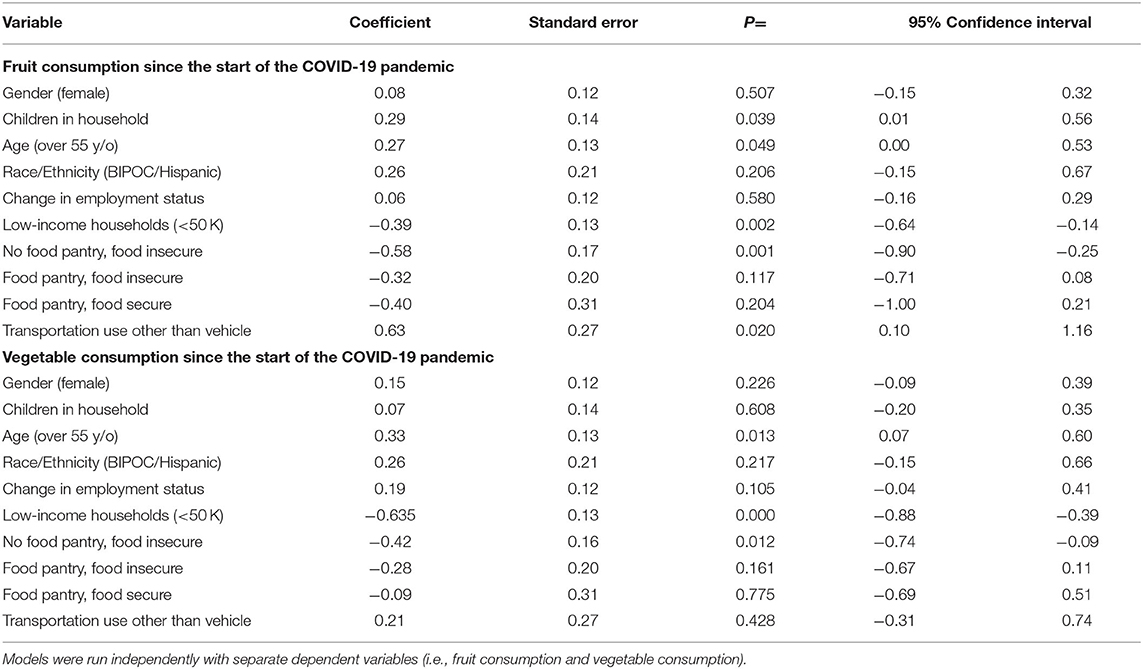

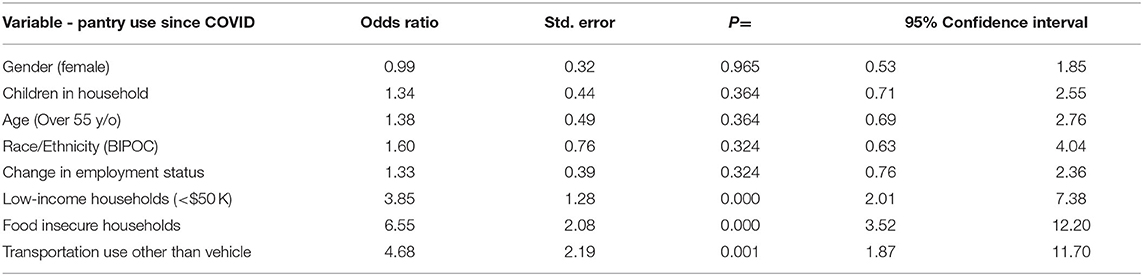

Charitable food services, including food banks and pantries, support individual and households' food access, potentially maintaining food security and diet quality during emergencies. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the use of food banks and pantries has increased in the US. Here we examine perceptions of food banks and food pantries and their relationship to food security and fruit and vegetable (FV) intake during the first 6 months of the COVID-19 pandemic, using a statewide representative survey ( n = 600) of residents of Vermont. The utilization of food pantries was more common among food insecure households and households with children. Among food insecure respondents, those who did not use a food pantry were significantly more likely to report consuming less FV during the pandemic. Further, we find respondents who are food insecure and using a food pantry report consuming more FV since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. We found that respondents who were both food insecure and reported not using a food pantry were significantly more likely to report both a reduction in fruit consumption ( b = -0.58; p = 0.001) and a reduction in vegetable consumption ( b = -0.415; p = 0.012). These results indicate that these services may support food access and one important dimension of diet quality (FV intake) for at-risk populations during emergencies.

Keywords: coronavirus; emergency food assistance; food pantry; food security; nutrition security.

Copyright © 2021 Bertmann, Rogomentich, Belarmino and Niles.

Cornell Chronicle

- Architecture & Design

- Arts & Humanities

- Business, Economics & Entrepreneurship

- Computing & Information Sciences

- Energy, Environment & Sustainability

- Food & Agriculture

- Global Reach

- Health, Nutrition & Medicine

- Law, Government & Public Policy

- Life Sciences & Veterinary Medicine

- Physical Sciences & Engineering

- Social & Behavioral Sciences

- Coronavirus

- News & Events

- Public Engagement

- New York City

- Photos of the Week

- Big Red Sports

- Freedom of Expression

- Student Life

- University Statements

- Around Cornell

- All Stories

- In the News

- Expert Quotes

- Cornellians

Food pantry access worth billions nationally, study finds

By james dean, cornell chronicle.

A research collaboration between Cornell and the U.S. Department of Agriculture offers the first estimates of the economic value contributed by food pantries, and finds it is substantial – worth up to $1,000 annually to participating families and as much as $28 billion nationwide.

The totals underscore food bank systems’ important role in addressing food insecurity, a role that has grown during the pandemic and recent bouts of inflation, said David R. Just , the Susan Eckert Lynch Professor in Science and Business in the Charles H. Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management, part of the Cornell SC Johnson College of Business and the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

“Food pantries make a huge difference to the households they serve, for many representing a substantial portion of their income,” Just said. “This is important information for policymakers considering support for the national or local food banking system, like tax breaks for food donation, direct program support from USDA or other efforts.”

Just is the co-author of " What is Free Food Worth? A Nonmarket Valuation Approach to Estimating the Welfare Effects of Food Pantry Services ,” published Nov. 9 in the American Journal of Agricultural Economics. The lead author is Anne Byrne, Ph.D. ’21, a research agricultural economist at the USDA’s Economic Research Service . The team has collaborated on multiple investigations of private food assistance.

“Private food assistance, especially food banking, has grown in recent decades,” Byrne said. “These organizations have a unique position within the food system and a specific role in food access because they offer quick relief in the form of free groceries to a wide variety of people, typically with minimal administrative hurdles.”

Food banks and pantries served 51 million people in 2021, according to the nonprofit Feeding America . Despite their importance, the researchers said, their economic value to the individuals and households that they serve hasn’t been estimated using rigorous economic methods.

Determining that value is challenging, the researchers said, since food pantries provide food and services at no cost. In addition, the market value of food may not accurately capture its value to people who can’t afford to access markets.

Byrne and Just thought they could get at the question using travel costs, a novel application of a methodology long used to value assets like national parks – where the cost of visiting isn’t primarily an entry fee – based on costs incurred to make the trip. They calculated the cost of travel to and from food pantries as a measure of households’ “willingness to pay” for the food, considering the distance, duration and frequency of their trips.

“We know they would be willing to give up at least this amount for the food they obtain, which enables us to identify demand in terms of price – travel costs – and quantity – visits,” Just said.

The scholars analyzed 13 years of data (2005-17) from a northern Colorado food bank that in 2017 served 10% of Larimer County residents at locations in Fort Collins and Loveland.

The data set included millions of pantry visits representing about 45,000 households – a population with lower incomes and more racial and ethnic minorities than the county overall, according to census data. To calculate travel costs, the researchers used Google maps for walking and driving distances and times, AAA data for vehicle costs, and reported incomes or the Colorado minimum wage to determine the opportunity cost of the time trips required.

The result was an estimated value to families of $40 to $60 per trip to a food pantry, and of $600 to $1,000 per year based on typical annual visit frequencies, with values increasing or decreasing with travel costs.

Extrapolated nationally – based on 389 million visits reported by Feeding America’s 2014 Hunger in America Study – the first-of-their-kind estimates confirm that “food bank services collectively represent a sizeable share of the food landscape,” the researchers wrote. Their estimated value of $19 to $28 billion is more than double the sales by farmers markets in 2020, and a significant fraction of federal food stamp (SNAP) benefits that year worth $74.2 billion, according to the research.

“Without such an estimate it is difficult to know whether food pantries are a worthwhile investment from a public policy perspective,” Just said. “Given the great number of families touched by these services and the significant investment and volunteer hours given, it is important to document and measure the value they are contributing to our economy.”

Media Contact

Lindsey knewstub.

Get Cornell news delivered right to your inbox.

You might also like

Gallery Heading

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 17 March 2022

A descriptive analysis of food pantries in twelve American states: hours of operation, faith-based affiliation, and location

- Natalie D. Riediger ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8736-9446 1 , 2 ,

- Lindsey Dahl 1 , 3 ,

- Rajeshwari A. Biradar 4 , 5 ,

- Adriana N. Mudryj 1 &

- Mahmoud Torabi 2

BMC Public Health volume 22 , Article number: 525 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

4672 Accesses

6 Citations

21 Altmetric

Metrics details

Our objectives were to describe both the development, and content, of a charitable food dataset that includes geographic information for food pantries in 12 American states.

Food pantries were identified from the foodpantries.org website for 12 states, which were linked to state-, county-, and census-level demographic information. The publicly available 2015 Food Access Research Atlas and the 2010 US Census of Population and Housing were used to obtain demographic information of each study state. We conducted a descriptive analysis and chi-square tests were used to test for differences in patterns of food pantries according to various factors.

We identified 3777 food pantries in 12 US states, providing an estimated 4.84 food pantries per 100,000 people, but ranged from 2.60 to 7.76 within individual states. The majority of counties (61.2%) had at least one food pantry. In contrast, only 15.7% of all census tracts in the study states had at least one food pantry. A higher proportion of urban census tracts had food pantries compared to rural tracts. We identified 2388 (63.2%) as being faith-based food pantries. More than a third (34.4%) of food pantries did not have information on their days of operation available. Among the food pantries displaying days of operation, 78.1% were open at least once per week. Only 13.6% of food pantries were open ≤1 day per month.

Conclusions

The dataset developed in this study may be linked to food access and food environment data to further examine associations between food pantries and other aspects of the consumer food system (e.g. food deserts) and population health from a systems perspective. Additional linkage with the U.S. Religion Census Data may be useful to examine associations between church communities and the spatial distribution of food pantries.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Food insecurity refers to the inability to access sufficient, safe, and nutritious food to meet the dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life [ 1 ]. The prevalence of household food insecurity in 2019 in the United States was estimated at 10.5% [ 2 ], which has only been exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic [ 3 ]. Given the significant number of food insecure households and food insecurity’s strong associations with poor health outcomes [ 4 , 5 , 6 ], particularly diabetes [ 7 , 8 ], and increased health care costs [ 9 ], food insecurity is a major public health concern. While food insecurity is inextricably linked to low income, food-based interventions at the municipal-level, such as food pantries have been thrust to the forefront in an attempt to alleviate the problem [ 10 ]. Food banks refer to charitable food assistance organizations that rely upon food and monetary donations in order to either distribute food to smaller charities that serve food insecure populations, or to provide a direct grocery service to clients, sometimes called food pantries or food shelves [ 11 ].

The inception of charitable food organizations in the 1960s was intended to serve as emergency food aid in response to short-term food insecurity. By the 1990’s, emergency food aid had grown to such an extent that in Detroit, Michigan there were more food banks, pantries, and soup kitchens ( N = 100) than supermarkets and large grocery stores ( N = 96) [ 12 ]. Despite the rise in charitable food, there is a lack of evidence supporting their effectiveness in addressing the main issue of food insecurity. At the individual-level, the charitable food system has been shown to contribute to stigma and shame among patrons [ 13 , 14 , 15 ], offer poor nutritional value [ 11 , 16 ], provide insufficient and inconsistent food supply [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ], consist of limited food choice and variety [ 16 ], and exacerbate pre-existing chronic health conditions [ 11 , 18 , 19 ]. Furthermore, “pantries spring up wherever someone is moved to create them” [ 20 ] (p221). In this way, the geographical distribution of food pantries may not follow any systematic pattern or necessarily reflect need. Many food pantries operate out of churches and volunteers are often motivated to volunteer because of their religious commitments. Given these circumstances and undercurrents, faith is an important and dynamic element of the charitable food system. However, faith-based affiliations within the current charitable food system is unknown and likely context-specific.

While the experiences of clients of the charitable food system have been explored qualitatively [ 13 , 21 , 22 ], and there is considerable individual-level data to evaluate food security programs, there has been little, if any, ecological data to describe the charitable food system. The charitable food system is one component, or sub-system, of the larger consumer food system, as well as part of the broader social and economic system. The scope of the charitable food system is related to overall food security, food security programs (i.e., food stamps), both smaller and larger grocery stores, and religious communities (i.e., churches), as some examples. Taken together, all these sub-systems also influence health outcomes (e.g., diabetes). An ecological analysis applying systems theory [ 23 ] as a conceptual framework to examine the consumer food system could provide important policy-relevant evidence regarding the charitable food system, as well as publicly-funded food security programs, food security, and health. Ecological studies are especially useful when the implications for intervention are at the population- or systems-level.

From a systems theory perspective [ 24 , 25 ], we understand that if charitable food makes up an increasing component of the consumer food system, other aspects of the food or economic systems counterbalance for this increase. For example, the reliance on the charitable food sector has reduced the pressure on governments to improving income security through social programs [ 26 , 27 ], and may further reduce participation in other public food programs. Similarly, applying a systems perspective, reductions in churches or declining participation in faith-based communities [ 28 , 29 ] may diminish charitable food assistance. The increasing involvement of the corporate food sector through donations (supported by governmental tax programs) may further aggravate food system inequality by contributing to the dissolution of smaller grocers and the preponderance of “food deserts” or areas devoid of fresh and whole foods in disadvantaged neighborhoods [ 30 ]. Smaller businesses may be unable to provide food at a comparable price to either larger grocery stores or the charitable sector, which is free. The interconnectedness of the food system is further displayed through the food systems impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic [ 3 ]. In this way, systems theory may be useful for exploring structural issues and inequities within consumer food systems, including charitable food systems as a sub-system.

In order to empirically examine the relationships amongst the consumer food sub-systems for future research, we have created a Charitable Food Dataset (CFD), which lists and documents characteristics of charitable food organizations in select states in the U.S. The objectives of this paper are to (1) describe the developed dataset and (2) describe the charitable food system according to days of operation, faith-based affiliation, and rural/urban location. This methods paper describes a dataset that can be linked to other publicly available datasets to further explore relationships within the food system.

Data sources

The CFD was constructed primarily from the publicly available charitable food organization directory at foodpantries.org [ 31 ]. The website is not affiliated with any governmental agency or non-profit organization, and manually collects information on food pantries, soup kitchens and non-profit organizations (collectively referred to as ‘food pantries’ hereinafter) in the 50 US states and the District of Columbia. Food pantries were identified in 12 study states (Alabama, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, Ohio, Tennessee and West Virginia) purposefully selected to achieve variation in the sample based on state prevalence of food security listed in the 2018 Food Environment Atlas, the inclusion of both rural and urban areas, as well as the number of food pantries in each state. The CFD contains the name, address, and hours/days of operation of each food pantry in the directory, which were entered into Microsoft Excel. The data were cleaned and any entries that shared the same name and/or address were considered duplicates and removed. The CFD data were collected between February 2017 and July 2018, and are stored in an open source repository [ 32 ].

Census tract numbers for each food pantry in the study states were obtained using the United States Census Bureau’s (USCB) Geocoder address look-up tool [ 33 ] and the one-line address associated with each food pantry. If census tracts were not found using the Geocoder, the food pantry was geographically located using Google Maps [ 34 ] and cross-referenced with the corresponding USCB Census Tract Reference Map [ 35 ]. The reference maps are county-based and display the census tract numbers for each delineated tract area within that county for the 2010 Census, which was the latest census completed in the US.

The publicly available 2015 Food Access Research Atlas [ 36 ] and the 2010 US Census of Population and Housing [ 37 ] were also used to obtain demographic information of each study state. The Food Access Research Atlas is maintained by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), and contains food access indicators at the census-tract level.

The Food Access Research Atlas includes the 2010 populations of each census tract based on the estimates from the 2010 US Census. These estimates were used to estimate the populations for each study state. The Atlas also includes an indicator variable for urban or rural census tracts based on whether the geographic centroid of the census tract is in an area with more than 2500 people as determined by the 2010 block-level population data and aerially allocated to ½ kilometre square grids [ 38 ]. This indicator variable was used to calculate the populations and the number of census tracts stratified by urban and rural census areas for each state. The number of counties per state was determined by converting the census tract numbers provided in the Atlas into county Federal Information Processing Standards (FIPS) and removing any duplicates. Finally, the 2010 Census was used to obtain the square mile of land area in each state as a measure of its geographic size.

A variable indicating whether a food pantry was affiliated with a Judeo-Christian organization was created by reviewing each food pantry name in the CFD for Judeo-Christian terms, for example, “Saint” or “church” (Table 1 ). These terms were subjectively selected based on their likelihood of being recognized as Judeo-Christian terms by someone who was using the foodpantries.org directory. We refer to these food pantries as faith-based for the remainder of the paper. Lastly, the days of operation of food pantries contained in the CFD varied widely ranging from 4 days per year to 5 days per week. Therefore, a variable was created by collapsing the days of operation into 5 categories: (1) ≤1 day per month; (2) 2–3 days per month; (3) once per week; (4) 2–3 days per week; (5) ≥4 days per week.

Descriptive statistics were generated for the study states, including population counts, number of counties, number of census tracts, proportion of urban and rural census tracts, and land area. Population counts for each state are from 2018, with the most recent estimates calculated from the 2010 Census. The urban and rural populations were determined by using the 2010 Census, which were provided at the census-tract level in the Food Access Research Atlas.

Descriptive analyses, using the state demographic information, were conducted for the food pantries in the CFD. First, the number of food pantries in each state was counted and the proportions that were in urban and rural census tracts were calculated. Second, the number of food pantries per 100,000 state population stratified by urban and rural tracts, as well as the number of food pantries per 1000 square miles of state land area, were determined. Third, the numbers of counties, census tracts, urban tracts, and rural tracts that had at least one food pantry were calculated, and the proportions within urban compared to rural census tracts were tested using chi-square tests. Fourth, the number and proportion of food pantries per state that were faith-based were calculated, and then stratified by urban and rural areas. The proportion of faith-based pantries in urban areas was compared with the proportion in rural areas using chi-square tests. Lastly, the frequencies within each category of days of operation were calculated. Chi-square tests were used to explore differences in the distributions of faith-based and non-faith-based food pantries, and of urban and rural food pantries, in the days of operation categories. The level of significance was set at 0.05 for all statistical tests, which were carried out using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 23.

The selected states represent a total of 1112 counties and 19,167 census tracts (Table 2 ). The average state population was 6,507,685 (SD = 3,642,347) and ranged from 1,852,994 to 12,830,632 people. The majority of census tracts were considered to be located in urban areas (69.1%), which represented approximately two thirds of the total population in the study states. The average state land area was 47,796 square miles (SD = 14,403) with a minimum of 24,038 and a maximum of 81,759 square miles.

We identified 3923 food pantries using the foodpantries.org directory, with 47 of the entries requiring the USCB reference maps to locate their census tract numbers. We removed 146 duplicate food pantry entries, resulting in 3777 individual food pantries in the CFD with three quarters of them located in urban census tracts (Table 3 ). The number of food pantries per 100,000 people in the overall sample was 4.84, ranging from 2.60 to 7.76 within the individual states. There were 5.31 food pantries per 100,000 in urban census tracts, and 3.79 in rural census tracts, and there were 6.59 food pantries per 1000 square miles of land area. The majority of counties (61.2%) had at least one food pantry. In contrast, only 15.7% of all census tracts in the study states had at least one food pantry (Table 4 ). Significantly more urban census tracts had a food pantry compared to rural census tracts (16.8% vs. 13.3%; p < .00001). We identified 2388 (63.2%) as being faith-based food pantries, with a significantly higher proportion of urban food pantries being faith-based compared to rural food pantries (65.1% vs. 57.4%, p < .0001; Table 5 ).

More than a third (34.4%) of food pantries did not have information on their days of operation available. The proportion of faith-based versus non-faith based food pantries that did not provide this information was not significantly different (35.4% vs. 32.7%; p = 0.093), as was the case for urban and rural food pantries (33.9% vs. 36.2%; p = 0.202). Among the food pantries displaying days of operation, 52.9% were open at least 2 days per week, while 78.1% were open at least once per week (Table 6 ). Only 13.6% of food pantries were open ≤1 day per month. Significant relationships existed between the days open categories and whether the food pantry was faith-based ( p < .00001), or was located in an urban or rural area ( p = 0.043). A higher proportion of faith-based and rural food pantries fell into the less frequently open categories, and had a lower proportion in the more frequently open categories as compared to non-faith-based food pantries and urban food pantries, respectively.

In this study, we described the processes involved in developing the CFD, a dataset containing information on food pantries in 12 US states. Descriptive findings indicate approximately three quarters of food pantries are located in urban areas, and almost two thirds were considered to have a faith affiliation, which were also more common in urban versus rural areas. Among pantries with hours of operation posted, 78.1% were open at least 1 day per week, and non-faith-based and urban food pantries were more likely to be open more often. This dataset can be linked via FIPS to a number of publicly available datasets, such as the USDA Food Access Research Atlas, the USDA Food Environment Atlas, and the U.S. Religion Census Data. Through linkage of this CFD with other datasets, a number of research questions can be examined.

Food insecurity affected 10.5% of households in the United States in 2020, and is more common among households with children, and Black or non-Hispanic householders [ 39 ]. Given the prevalence of food insecurity, efforts to mitigate food insecurity have the capacity to greatly improve population health at multiple levels – national, state, county, household, and individual. The role of food assistance programs has increased as a result of the decline of non-food social programs. The largest publicly-funded food assistance program in the US is SNAP, which provided ‘food stamp’ benefits to more than 44 million people in 2016 [ 40 ]. However, many eligible people do not participate in the program, and among those who do, approximately half of them continue to report being food insecure [ 41 ]. Charitable food assistance programs or food banks, which were initially established to provide emergency food supplies, are now considered to supplement the governmental programs in their effort to address food insecurity. In fact, 26.5% of food insecure households and 4.8% of all US households used a food pantry in 2016, representing a 40 and 68% increase from 2001, respectively [ 42 ]. For these reasons, it has become increasingly important to consider the effects of growing charitable food programs on food security and health [ 43 ].

Charitable food organizations, and other community-level initiatives, have the potential to improve individual health through emergency food provision [ 10 ]. However, most health research, media attention, and governmental policy action is disproportionately focused on individual health and exposures, which limits our ability to understand structural drivers of inequality [ 43 , 44 , 45 ]. The USDA’s Food Access Research Atlas and the Food Environment Atlas provide data on food access and environmental indicators at the census tract- and county-levels. By assigning census tract numbers to each food pantry, the CFD is able to link with both atlases, providing an opportunity to explore the structural drivers of health inequality as it relates to food pantries, ‘food deserts’, federal food programs, food insecurity, and health. The CFD is also able to link with US Religion Census data [ 46 ], which contains data on congregations, members, adherents, and attendees, or the population purported to sustain the charitable food sector.

The CFD consists of more food pantries located in urban census tracts compared to rural tracts, reflecting the higher proportion of urban census tracts in the US. The proportion of urban census tracts that had at least one food pantry was 26% higher compared to rural census tracts, and the number of food pantries per urban population was higher than the number per rural population by approximately 40%. This is inconsistent with previously reported data using county-level information from the Map the Meal Gap project and the Hunger in America 2014 survey, which showed that the number of charitable food locations per 1000 people was highest in counties that were considered completely rural according to urban-rural continuum codes [ 47 ]. However, the difference in defining urban and rural areas (i.e., county versus census tract) makes it difficult to compare the findings from the two studies. Given that food insecurity is more prevalent in more populated metropolitan areas compared to nonmetropolitan areas, this may indicate that the food pantries in our dataset are located in areas of greatest need [ 3 ]. However, further research is needed to provide estimates of food insecurity at the census-tract level in order to determine if, in fact, the food pantries are concentrated in the areas that would benefit most from their service.

Charitable food organizations rely heavily on food and monetary donations, and volunteers for their operation. In this way, faith-based or religious organizations, with their ability to engage their communities and which often work for social justice and against inequality, are set up well to provide such services [ 48 ]. In addition, volunteerism in food banks and pantries is often motivated by faith and has an important role in building community [ 20 ]. This may explain the higher proportion of food pantries identified as faith-based in the CFD. The relationship between religion and population health has been extensively explored, and through its ability to provide social capital to communities, especially the most vulnerable communities, illustrate religions’ importance as a social determinant of health [ 49 , 50 ]. However, the variability in the hours of operation of food pantries reflects the volunteer nature of food banking, and is a legitimate concern among clients given that many rely on prolonged use of food pantries [ 4 , 51 ]. This may illustrate the limits of volunteerism in addressing food insecurity, which may be exacerbated as participation in faith-based communities is declining [ 29 ].

The large size and diversity of the CFD is a strength, which provides a foundation for future research exploring the relationship between charitable food and social- and health- related outcomes from a systems perspective. However, there are several limitations of this dataset, and the present study, that must be considered. First, the completeness of the dataset is uncertain. The foodpantries.org directory only contains information regarding updates, corrections, or new food pantries that they receive manually through an online submission form. Some food pantries may not be in the directory, while others may still be included despite closure. We documented 146 directory entries that were considered duplicates because they shared either the same name or address with another entry, which illustrates the limitation in the maintenance of the directory. Furthermore, Feeding America advertises 200 food banks and 60,000 food programs as part of its network; however, foodpantries.org documented only 15,494 food pantries in total in 2018, with 3777 included in the present study. While it is unclear how Feeding America defines a ‘food program’ or whether the 60,000 food programs are a cumulative or a point prevalence, there is clearly a large discrepancy. However, our documented totals for food pantries in Detroit, Michigan are very similar to previous research conducted 4 to 5 years earlier; in addition to foodpantries.org , authors also utilized Local Harvest and several local sources to identify food pantries [ 12 ].

Second, faith-based affiliations were subjectively determined using a collection of common Judeo-Christian terms, which may have led to some misclassification. This approach identified 63.2% of food pantries as Christian faith-based. In her 1998 book, Poppendieck states that “more than 70 percent of the pantries and kitchens affiliated with the Second Harvest Network are sponsored by churches or other religious organizations” and that this is likely an underestimate of “the prevalence of religious orientation” [ 20 ] (p188–89).

Third, while many food pantries are open at least once a week, the quantity of food available per family, their form (pre-packaged food boxes or grocery store style), and the quality of the food provided is unknown. Research suggests that the quality of food available at food pantries does not meet recommendations put in place by health professionals [ 52 ]. Furthermore, we are missing data on days of operation for nearly a third of food pantries.

Fourth, food pantries that are only open a few times a year (i.e., one to four times) are also included in the foodpantries.org directory. These food pantries likely operate only during specific holidays (i.e., Christmas and Thanksgiving); while they can address immediate hunger, they will have limited impact on individual or population-level food insecurity.

Fifth, the proportion of food pantries per population used the most recent population estimates from the US Census that could be stratified by urban and rural census areas, which were estimated 8 years prior to the date that the number of food pantries was determined. The populations increase slightly each year, therefore, the proportions are likely over-estimated. Lastly, the inclusion of only 12 states may limit the generalizability of the data to the United States as a whole, though it is also unlikely that the 12 states selected are completely unique to the country.

To validate the completeness of the dataset, extensive ground truthing exercises and/or comparison to other existing local datasets collected through other means could be completed. This may mitigate some of the limitations previously described. This dataset could be updated through identical methods, and corresponding validation procedures. Ideally, all countries with charitable food systems, particularly those receiving public funds, should be keeping public records or datasets of food pantries to track the distribution of charitable food. Ensuring accurate and complete data is critical to informing policy related to food security.

In conclusion, food pantries in these 12 states are mostly set in urban areas, and affiliated with Judeo-Christian organizations. Their operation hours vary considerably; however, many are open at least once a week. The dataset developed in this study may be linked to food access and food environment data to further explore associations between concentration of food pantries and other aspects of the consumer food system and prevalence of health outcomes, such as diabetes, from a systems perspective. Additional linkage with the U.S. Religion Census Data may be useful to examine associations between church communities and the spatial distribution of food pantries. The number of food pantries has increased since their inception in the 1960s, which may be attributed to ongoing deficiencies in publicly-funded food security and social programs. However, the extent to which the existence of food pantries is dependent on faith-based communities and associated volunteers is concerning given the precarity of operations and declines in church participation [ 29 ]. We must understand the implications of the charitable food system to the larger food and economic system, prior to continuing to grow the charitable sector, either directly with funding, or indirectly through reduced spending to social programs.

Availability of data and materials

All data sources used in this study are publicly available.

Riediger, Natalie, 2022, “Charitable Food Descriptors located in 12 States in America”, https://doi.org/10.34990/FK2/GHL06P , University of Manitoba, V1, UNF:6:B8jxycLhATZEObfR8BW2mQ== [fileUNF].

United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Food Access Research Atlas. 2017. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-access-research-atlas/ . Accessed November 10, 2021.

United States Census Bureau. United States Summary: 2010. Population and Housing Unit Counts. 2012. https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/cph-2-1.pdf . Accessed November 11, 2021.

Abbreviations

Charitable Food Dataset

Supplemental Nutrition Access Program

United States Census Bureau

United States Department of Agriculture

Women, Infants, and Children program

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Rome Declaration on World Food Security and World Food Summit Plan of Action. 2006. https://www.fao.org/3/W3613E/W3613E00.htm . Accessed 10 Nov 10, 2021.

Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Gregory CA, Singh A. Household food security in the United States in 2019. United States department of Agriculture. September 2020. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/99282/err-275.pdf?v=3785.8

United States Department of Agriculture. COVID-19 Economic Implications for Agriculture, Food, and Rural America: Food and Consumers. https://www.ers.usda.gov/covid-19/food-and-consumers/

Chiu CY, Brooks J, An R. Beyond food insecurity. Br Food J. 2016;118(11):2614–31.

Article Google Scholar

Kirk SFL, Kuhle S, McIsaac J-LD, Williams PL, Rossiter M, Ohinmaa A, et al. Food security status among grade 5 students in Nova Scotia, Canada and its association with health outcomes. Public Health Nutr. 2014;18(16):2943–51.

Sharkey JR, Johnson C, Dean WR. Relationship of household food insecurity to health-related quality of life in a large sample of rural and urban women. Women Health. 2011;51(5):442–60.

Strings S, Ranchod YK, Laraia B, Nuru-Jeter A. Race and sex differences in the association between food insecurity and type 2 diabetes. Ethn Dis. 2016;26(3):427–33.

Ray EB, Holben DH, Holcomb JP Jr. Food security status and produce intake behaviors, health status, and diabetes risk among women with children living on a Navajo reservation. J Hunger Envir Nutr. 2012;7(1):91–100.

Tarasuk V, Dachner N, de Oliviera C, Kurdyak P, Cheng J, Gundersen C. Association between household food insecurity and annual health care costs. CMAJ. 2015;187(14):e429–36.

Collins PA, Power EM, Little MH. Municipal-level responses to household food insecurity in Canada: a call for critical, evaluative research. Can J Public Health. 2014;105(2):e138–41.

Bazerghi C, McKay FH, Dunn M. The role of food banks in addressing food insecurity: a systematic review. J Community Health. 2016;41(4):732–40.

Taylor DE, Ard KJ. Food availability and the food desert frame in Detroit: an overview of the City’s food system. Environ Pract. 2015;17:102–33.

Caplan P. Big society or broken society? Food banks in the UK. Anthropol Today. 2016;32(1):5–9.

Bhawra J, Cooke MJ, Hanning R, Gonneville SLH. Community perspectives of food insecurity and obesity: focus groups with caregivers of Métis and off-reserve first nations children. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14(1):96.

van der Horst H, Pascucci S, Bol W. The, “dark side” of food banks? Exploring emotional responses of food bank receivers in the Netherlands. Br Food J. 2014;116(9):1506–20.

Campbell E, Hudson H, Webb K, Crawford PB. Food preferences of users of the emergency food system. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2011;6(2):179–87.

Power E. Canadian food banks: obscuring the reality of hunger and poverty. Food Ethics. 2011;6:18–20.

Google Scholar

Ippolito MM, Lyles CR, Prendergast K, Marshall MB, Waxman E, Seligman HK. Food insecurity and diabetes self-management among food pantry clients. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(1):183–9.

Garthwaite KA, Collins PJ, Bambra C. Food for thought: An ethnographic study of negotiating ill health and food insecurity in a UK food bank. Soc Sci Med. 2015;132:38–44.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Poppendieck J. Sweet charity? Emergency food and the end of entitlement. Penguin; 1999.

Lindberg R, Lawrence M, Caraher M. Kitchens and pantries—helping or hindering? The perspectives of emergency food users in Victoria, Australia. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2017;12(1):26–45.

Tarasuk V, Eakin JM. Charitable food assistance as symbolic gesture: An ethnographic study of food banks in Ontario. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(7):1505–15.

Sobal J, Khan LK, Bisogni C. A conceptual model of the food and nutrition system. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47(7):853–63.

Dror Y. Policy analysts: a new professional role in government service. Public Adm Rev. 1967;27(3):197–203.

Hammond RA, Dubé L. A systems science perspective and transdisciplinary models for food and nutrition security. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:12356–63.

Daponte BO, Bade S. How the private food assistance network evolved: interactions between public and private responses to hunger. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q. 2006;35(4):668–90.

Tarasuk V, Eakin JM. Food assistance through "surplus" food: insights from an ethnographic study of food bank work. Agri Human Values. 2005;22(2):177–86.

Pew Research Center (2013). Canada’s changing religious landscape. Retrieved from https://www.pewforum.org/2013/06/27/canadas-changing-religious-landscape/ . Accessed 10 Nov 2021.

Pew Research Center (2018). Young adults around the world are less religious by several measures. Retrieved from https://www.pewforum.org/2018/06/13/young-adults-around-the-world-are-less-religious-by-several-measures/ . Accessed 10 Nov 2021.

Beaulac J, Kristjansson E, Cummins S. A systematic review of food deserts, 1966–2007. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6(3):A105.

Food Pantries. Find Food Pantries . https://www.foodpantries.org/ . Accessed 10 Nov 2021.

Riediger, Natalie, 2022, "Charitable food descriptors located in 12 states in America", https://doi.org/10.34990/FK2/GHL06P , University of Manitoba, V1, UNF:6:B8jxycLhATZEObfR8BW2mQ== [fileUNF].

United States Census Bureau. https://geocoding.geo.census.gov/geocoder/ . Accessed 10 Nov 2021.

Google Maps. https://www.google.ca/maps/ . Accessed 10 Nov 2021.

United States Census Bureau. 2010 Census tract reference maps . 2018 https://wwwcensusgov/geographies/reference-maps/2010/geo/2010-census-tract-mapshtml Accessed 10 Nov 2021.

United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Food Access Research Atlas . 2017. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-access-research-atlas/ . Accessed 10 Nov 2021.

United States Census Bureau. United States Summary: 2010. Population and Housing Unit Counts 2012. https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/cph-2-1.pdf . Accessed 11 Nov 2021.

United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Documentation. 2017. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-access-research-atlas/documentation/ . Accessed 11 Nov 2021.

Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Gregory CA, Singh A. Household food security in the United States in 2020, ERR-298, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2021. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/102076/err-298.pdf?v=4819.7 . Accessed 16 Nov 2021.

Gundersen C, Ziliak JP. Food insecurity research in the United States: where we have been and where we need to go. Appl Econ Persp Policy. 2018;40(1):119–35.

Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt M, Gregory C, Singh A. Household food security in the United States in 2017, ERR-256, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2018. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/90023/err-256.pdf?v=0 . Accessed 10 Nov 2021.

Coleman-Jensen A, Nord M, Andrews M, Carlson S. Statistical supplement to household food security in the United States in 2016. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2016. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/84981/ap-077.pdf?v=0 . Accessed 10 Nov 2021.

Baum F, Fisher M. Why behavioural health promotion endures despite its failure to reduce health inequities. Sociol Health Illness. 2014;36(2):213–25.

Raphael D. Grasping at straws: a recent history of health promotion in Canada. Crit Public Health. 2008;18(4):483–95.

Carey G, Malbon E, Crammond B, Pescud M, Baker P. Can the sociology of social problems help us to understand and manage ‘lifestyle drift’? Health Promot Int. 2016;32(4):755–61.

U.S Religion Census (2019). The 2010 U.S. religion census. Retrieved from: http://usreligioncensus.org/ . Accessed 10 Nov 2021.

Gundersen C, Dewey A, Hake M, Engelhard E, Crumbaugh AS. Food insecurity across the rural-urban divide: are counties in need being reached by charitable food assistance? Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2017;672(1):217–37.

Campbell MK, Hudson MA, Resnicow K, Blakeney N, Paxton A, Baskin M. Church-based health promotion interventions: evidence and lessons learned. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:213–34.

Stroope S, Baker JO. Whose moral community? Religiosity, secularity, and self-rated health across communal religious contexts. J Health Soc Behav. 2018;59(2):185–99.

Idler E, Levin J, VanderWeele TJ, Khan A. Partnerships between public health agencies and faith communities. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(3):346–7.

Kaiser ML, Cafer AM. Exploring long-term food pantry use: differences between persistent and prolonged typologies of use. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2017;12(1):46–63.

Irwin JD, Ng VK, Rush TJ, Nguyen C, He M. Can food banks sustain nutrient requirements? Can J Public Health. 2007;98(1):17–20.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the students involved in data collection and Kelsey Mann for her editorial support.

This study was funded through start-up funds to NDR from the University of Manitoba and the University Research Grants Program (2016). NDR is funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Early Career Investigator Award (grant number 155435). RB was funded by the Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Scholarship Program (2017–2018).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Food and Human Nutritional Sciences, Faculty of Agricultural and Food Sciences, University of Manitoba, 209 Human Ecology Building, Winnipeg, MB, Canada

Natalie D. Riediger, Lindsey Dahl & Adriana N. Mudryj

Department of Community Health Sciences, Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada

Natalie D. Riediger & Mahmoud Torabi

Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, Department of Community Health Sciences, Max Rady College of Medicine, Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada

Lindsey Dahl

Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, India

Rajeshwari A. Biradar

Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, KLE Academy of Higher Education & Research (K.A.H.E.R) Nehru Nagar, Belagavi, Karnataka, India

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

NR was involved in formulating the research question, designing the study, and drafting the manuscript. LD was involved in data analysis, contributing to interpretation, and drafting the manuscript. RB was involved in collecting the data, data analysis, contributing to interpretation, and reviewing the manuscript for intellectual content. AM was involved in designing the study, collecting the data, contributing to interpretation, and reviewing the manuscript for intellectual content. MT was involved in designing the study, contributing to interpretation, and reviewing the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Natalie D. Riediger .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors have no conflicts of interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions