Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

Reflective writing is a process of identifying, questioning, and critically evaluating course-based learning opportunities, integrated with your own observations, experiences, impressions, beliefs, assumptions, or biases, and which describes how this process stimulated new or creative understanding about the content of the course.

A reflective paper describes and explains in an introspective, first person narrative, your reactions and feelings about either a specific element of the class [e.g., a required reading; a film shown in class] or more generally how you experienced learning throughout the course. Reflective writing assignments can be in the form of a single paper, essays, portfolios, journals, diaries, or blogs. In some cases, your professor may include a reflective writing assignment as a way to obtain student feedback that helps improve the course, either in the moment or for when the class is taught again.

How to Write a Reflection Paper . Academic Skills, Trent University; Writing a Reflection Paper . Writing Center, Lewis University; Critical Reflection . Writing and Communication Centre, University of Waterloo; Tsingos-Lucas et al. "Using Reflective Writing as a Predictor of Academic Success in Different Assessment Formats." American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 81 (2017): Article 8.

Benefits of Reflective Writing Assignments

As the term implies, a reflective paper involves looking inward at oneself in contemplating and bringing meaning to the relationship between course content and the acquisition of new knowledge . Educational research [Bolton, 2010; Ryan, 2011; Tsingos-Lucas et al., 2017] demonstrates that assigning reflective writing tasks enhances learning because it challenges students to confront their own assumptions, biases, and belief systems around what is being taught in class and, in so doing, stimulate student’s decisions, actions, attitudes, and understanding about themselves as learners and in relation to having mastery over their learning. Reflection assignments are also an opportunity to write in a first person narrative about elements of the course, such as the required readings, separate from the exegetic and analytical prose of academic research papers.

Reflection writing often serves multiple purposes simultaneously. In no particular order, here are some of reasons why professors assign reflection papers:

- Enhances learning from previous knowledge and experience in order to improve future decision-making and reasoning in practice . Reflective writing in the applied social sciences enhances decision-making skills and academic performance in ways that can inform professional practice. The act of reflective writing creates self-awareness and understanding of others. This is particularly important in clinical and service-oriented professional settings.

- Allows students to make sense of classroom content and overall learning experiences in relation to oneself, others, and the conditions that shaped the content and classroom experiences . Reflective writing places you within the course content in ways that can deepen your understanding of the material. Because reflective thinking can help reveal hidden biases, it can help you critically interrogate moments when you do not like or agree with discussions, readings, or other aspects of the course.

- Increases awareness of one’s cognitive abilities and the evidence for these attributes . Reflective writing can break down personal doubts about yourself as a learner and highlight specific abilities that may have been hidden or suppressed due to prior assumptions about the strength of your academic abilities [e.g., reading comprehension; problem-solving skills]. Reflective writing, therefore, can have a positive affective [i.e., emotional] impact on your sense of self-worth.

- Applying theoretical knowledge and frameworks to real experiences . Reflective writing can help build a bridge of relevancy between theoretical knowledge and the real world. In so doing, this form of writing can lead to a better understanding of underlying theories and their analytical properties applied to professional practice.

- Reveals shortcomings that the reader will identify . Evidence suggests that reflective writing can uncover your own shortcomings as a learner, thereby, creating opportunities to anticipate the responses of your professor may have about the quality of your coursework. This can be particularly productive if the reflective paper is written before final submission of an assignment.

- Helps students identify their tacit [a.k.a., implicit] knowledge and possible gaps in that knowledge . Tacit knowledge refers to ways of knowing rooted in lived experience, insight, and intuition rather than formal, codified, categorical, or explicit knowledge. In so doing, reflective writing can stimulate students to question their beliefs about a research problem or an element of the course content beyond positivist modes of understanding and representation.

- Encourages students to actively monitor their learning processes over a period of time . On-going reflective writing in journals or blogs, for example, can help you maintain or adapt learning strategies in other contexts. The regular, purposeful act of reflection can facilitate continuous deep thinking about the course content as it evolves and changes throughout the term. This, in turn, can increase your overall confidence as a learner.

- Relates a student’s personal experience to a wider perspective . Reflection papers can help you see the big picture associated with the content of a course by forcing you to think about the connections between scholarly content and your lived experiences outside of school. It can provide a macro-level understanding of one’s own experiences in relation to the specifics of what is being taught.

- If reflective writing is shared, students can exchange stories about their learning experiences, thereby, creating an opportunity to reevaluate their original assumptions or perspectives . In most cases, reflective writing is only viewed by your professor in order to ensure candid feedback from students. However, occasionally, reflective writing is shared and openly discussed in class. During these discussions, new or different perspectives and alternative approaches to solving problems can be generated that would otherwise be hidden. Sharing student's reflections can also reveal collective patterns of thought and emotions about a particular element of the course.

Bolton, Gillie. Reflective Practice: Writing and Professional Development . London: Sage, 2010; Chang, Bo. "Reflection in Learning." Online Learning 23 (2019), 95-110; Cavilla, Derek. "The Effects of Student Reflection on Academic Performance and Motivation." Sage Open 7 (July-September 2017): 1–13; Culbert, Patrick. “Better Teaching? You Can Write On It “ Liberal Education (February 2022); McCabe, Gavin and Tobias Thejll-Madsen. The Reflection Toolkit . University of Edinburgh; The Purpose of Reflection . Introductory Composition at Purdue University; Practice-based and Reflective Learning . Study Advice Study Guides, University of Reading; Ryan, Mary. "Improving Reflective Writing in Higher Education: A Social Semiotic Perspective." Teaching in Higher Education 16 (2011): 99-111; Tsingos-Lucas et al. "Using Reflective Writing as a Predictor of Academic Success in Different Assessment Formats." American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 81 (2017): Article 8; What Benefits Might Reflective Writing Have for My Students? Writing Across the Curriculum Clearinghouse; Rykkje, Linda. "The Tacit Care Knowledge in Reflective Writing: A Practical Wisdom." International Practice Development Journal 7 (September 2017): Article 5; Using Reflective Writing to Deepen Student Learning . Center for Writing, University of Minnesota.

How to Approach Writing a Reflection Paper

Thinking About Reflective Thinking

Educational theorists have developed numerous models of reflective thinking that your professor may use to frame a reflective writing assignment. These models can help you systematically interpret your learning experiences, thereby ensuring that you ask the right questions and have a clear understanding of what should be covered. A model can also represent the overall structure of a reflective paper. Each model establishes a different approach to reflection and will require you to think about your writing differently. If you are unclear how to fit your writing within a particular reflective model, seek clarification from your professor. There are generally two types of reflective writing assignments, each approached in slightly different ways.

1. Reflective Thinking about Course Readings

This type of reflective writing focuses on thoughtfully thinking about the course readings that underpin how most students acquire new knowledge and understanding about the subject of a course. Reflecting on course readings is often assigned in freshmen-level, interdisciplinary courses where the required readings examine topics viewed from multiple perspectives and, as such, provide different ways of analyzing a topic, issue, event, or phenomenon. The purpose of reflective thinking about course readings in the social and behavioral sciences is to elicit your opinions, beliefs, and feelings about the research and its significance. This type of writing can provide an opportunity to break down key assumptions you may have and, in so doing, reveal potential biases in how you interpret the scholarship.

If you are assigned to reflect on course readings, consider the following methods of analysis as prompts that can help you get started :

- Examine carefully the main introductory elements of the reading, including the purpose of the study, the theoretical framework being used to test assumptions, and the research questions being addressed. Think about what ideas stood out to you. Why did they? Were these ideas new to you or familiar in some way based on your own lived experiences or prior knowledge?

- Develop your ideas around the readings by asking yourself, what do I know about this topic? Where does my existing knowledge about this topic come from? What are the observations or experiences in my life that influence my understanding of the topic? Do I agree or disagree with the main arguments, recommended course of actions, or conclusions made by the author(s)? Why do I feel this way and what is the basis of these feelings?

- Make connections between the text and your own beliefs, opinions, or feelings by considering questions like, how do the readings reinforce my existing ideas or assumptions? How the readings challenge these ideas or assumptions? How does this text help me to better understand this topic or research in ways that motivate me to learn more about this area of study?

2. Reflective Thinking about Course Experiences

This type of reflective writing asks you to critically reflect on locating yourself at the conceptual intersection of theory and practice. The purpose of experiential reflection is to evaluate theories or disciplinary-based analytical models based on your introspective assessment of the relationship between hypothetical thinking and practical reality; it offers a way to consider how your own knowledge and skills fit within professional practice. This type of writing also provides an opportunity to evaluate your decisions and actions, as well as how you managed your subsequent successes and failures, within a specific theoretical framework. As a result, abstract concepts can crystallize and become more relevant to you when considered within your own experiences. This can help you formulate plans for self-improvement as you learn.

If you are assigned to reflect on your experiences, consider the following questions as prompts to help you get started :

- Contextualize your reflection in relation to the overarching purpose of the course by asking yourself, what did you hope to learn from this course? What were the learning objectives for the course and how did I fit within each of them? How did these goals relate to the main themes or concepts of the course?

- Analyze how you experienced the course by asking yourself, what did I learn from this experience? What did I learn about myself? About working in this area of research and study? About how the course relates to my place in society? What assumptions about the course were supported or refuted?

- Think introspectively about the ways you experienced learning during the course by asking yourself, did your learning experiences align with the goals or concepts of the course? Why or why do you not feel this way? What was successful and why do you believe this? What would you do differently and why is this important? How will you prepare for a future experience in this area of study?

NOTE: If you are assigned to write a journal or other type of on-going reflection exercise, a helpful approach is to reflect on your reflections by re-reading what you have already written. In other words, review your previous entries as a way to contextualize your feelings, opinions, or beliefs regarding your overall learning experiences. Over time, this can also help reveal hidden patterns or themes related to how you processed your learning experiences. Consider concluding your reflective journal with a summary of how you felt about your learning experiences at critical junctures throughout the course, then use these to write about how you grew as a student learner and how the act of reflecting helped you gain new understanding about the subject of the course and its content.

ANOTHER NOTE: Regardless of whether you write a reflection paper or a journal, do not focus your writing on the past. The act of reflection is intended to think introspectively about previous learning experiences. However, reflective thinking should document the ways in which you progressed in obtaining new insights and understandings about your growth as a learner that can be carried forward in subsequent coursework or in future professional practice. Your writing should reflect a furtherance of increasing personal autonomy and confidence gained from understanding more about yourself as a learner.

Structure and Writing Style

There are no strict academic rules for writing a reflective paper. Reflective writing may be assigned in any class taught in the social and behavioral sciences and, therefore, requirements for the assignment can vary depending on disciplinary-based models of inquiry and learning. The organization of content can also depend on what your professor wants you to write about or based on the type of reflective model used to frame the writing assignment. Despite these possible variations, below is a basic approach to organizing and writing a good reflective paper, followed by a list of problems to avoid.

Pre-flection

In most cases, it's helpful to begin by thinking about your learning experiences and outline what you want to focus on before you begin to write the paper. This can help you organize your thoughts around what was most important to you and what experiences [good or bad] had the most impact on your learning. As described by the University of Waterloo Writing and Communication Centre, preparing to write a reflective paper involves a process of self-analysis that can help organize your thoughts around significant moments of in-class knowledge discovery.

- Using a thesis statement as a guide, note what experiences or course content stood out to you , then place these within the context of your observations, reactions, feelings, and opinions. This will help you develop a rough outline of key moments during the course that reflect your growth as a learner. To identify these moments, pose these questions to yourself: What happened? What was my reaction? What were my expectations and how were they different from what transpired? What did I learn?

- Critically think about your learning experiences and the course content . This will help you develop a deeper, more nuanced understanding about why these moments were significant or relevant to you. Use the ideas you formulated during the first stage of reflecting to help you think through these moments from both an academic and personal perspective. From an academic perspective, contemplate how the experience enhanced your understanding of a concept, theory, or skill. Ask yourself, did the experience confirm my previous understanding or challenge it in some way. As a result, did this highlight strengths or gaps in your current knowledge? From a personal perspective, think introspectively about why these experiences mattered, if previous expectations or assumptions were confirmed or refuted, and if this surprised, confused, or unnerved you in some way.

- Analyze how these experiences and your reactions to them will shape your future thinking and behavior . Reflection implies looking back, but the most important act of reflective writing is considering how beliefs, assumptions, opinions, and feelings were transformed in ways that better prepare you as a learner in the future. Note how this reflective analysis can lead to actions you will take as a result of your experiences, what you will do differently, and how you will apply what you learned in other courses or in professional practice.

Basic Structure and Writing Style

Reflective Background and Context

The first part of your reflection paper should briefly provide background and context in relation to the content or experiences that stood out to you. Highlight the settings, summarize the key readings, or narrate the experiences in relation to the course objectives. Provide background that sets the stage for your reflection. You do not need to go into great detail, but you should provide enough information for the reader to understand what sources of learning you are writing about [e.g., course readings, field experience, guest lecture, class discussions] and why they were important. This section should end with an explanatory thesis statement that expresses the central ideas of your paper and what you want the readers to know, believe, or understand after they finish reading your paper.

Reflective Interpretation

Drawing from your reflective analysis, this is where you can be personal, critical, and creative in expressing how you felt about the course content and learning experiences and how they influenced or altered your feelings, beliefs, assumptions, or biases about the subject of the course. This section is also where you explore the meaning of these experiences in the context of the course and how you gained an awareness of the connections between these moments and your own prior knowledge.

Guided by your thesis statement, a helpful approach is to interpret your learning throughout the course with a series of specific examples drawn from the course content and your learning experiences. These examples should be arranged in sequential order that illustrate your growth as a learner. Reflecting on each example can be done by: 1) introducing a theme or moment that was meaningful to you, 2) describing your previous position about the learning moment and what you thought about it, 3) explaining how your perspective was challenged and/or changed and why, and 4) introspectively stating your current or new feelings, opinions, or beliefs about that experience in class.

It is important to include specific examples drawn from the course and placed within the context of your assumptions, thoughts, opinions, and feelings. A reflective narrative without specific examples does not provide an effective way for the reader to understand the relationship between the course content and how you grew as a learner.

Reflective Conclusions

The conclusion of your reflective paper should provide a summary of your thoughts, feelings, or opinions regarding what you learned about yourself as a result of taking the course. Here are several ways you can frame your conclusions based on the examples you interpreted and reflected on what they meant to you. Each example would need to be tied to the basic theme [thesis statement] of your reflective background section.

- Your reflective conclusions can be described in relation to any expectations you had before taking the class [e.g., “I expected the readings to not be relevant to my own experiences growing up in a rural community, but the research actually helped me see that the challenges of developing my identity as a child of immigrants was not that unusual...”].

- Your reflective conclusions can explain how what you learned about yourself will change your actions in the future [e.g., “During a discussion in class about the challenges of helping homeless people, I realized that many of these people hate living on the street but lack the ability to see a way out. This made me realize that I wanted to take more classes in psychology...”].

- Your reflective conclusions can describe major insights you experienced a critical junctures during the course and how these moments enhanced how you see yourself as a student learner [e.g., "The guest speaker from the Head Start program made me realize why I wanted to pursue a career in elementary education..."].

- Your reflective conclusions can reconfigure or reframe how you will approach professional practice and your understanding of your future career aspirations [e.g.,, "The course changed my perceptions about seeking a career in business finance because it made me realize I want to be more engaged in customer service..."]

- Your reflective conclusions can explore any learning you derived from the act of reflecting itself [e.g., “Reflecting on the course readings that described how minority students perceive campus activities helped me identify my own biases about the benefits of those activities in acclimating to campus life...”].

NOTE: The length of a reflective paper in the social sciences is usually less than a traditional research paper. However, don’t assume that writing a reflective paper is easier than writing a research paper. A well-conceived critical reflection paper often requires as much time and effort as a research paper because you must purposeful engage in thinking about your learning in ways that you may not be comfortable with or used to. This is particular true while preparing to write because reflective papers are not as structured as a traditional research paper and, therefore, you have to think deliberately about how you want to organize the paper and what elements of the course you want to reflect upon.

ANOTHER NOTE: Do not limit yourself to using only text in reflecting on your learning. If you believe it would be helpful, consider using creative modes of thought or expression such as, illustrations, photographs, or material objects that reflects an experience related to the subject of the course that was important to you [e.g., like a ticket stub to a renowned speaker on campus]. Whatever non-textual element you include, be sure to describe the object's relevance to your personal relationship to the course content.

Problems to Avoid

A reflective paper is not a “mind dump” . Reflective papers document your personal and emotional experiences and, therefore, they do not conform to rigid structures, or schema, to organize information. However, the paper should not be a disjointed, stream-of-consciousness narrative. Reflective papers are still academic pieces of writing that require organized thought, that use academic language and tone , and that apply intellectually-driven critical thinking to the course content and your learning experiences and their significance.

A reflective paper is not a research paper . If you are asked to reflect on a course reading, the reflection will obviously include some description of the research. However, the goal of reflective writing is not to present extraneous ideas to the reader or to "educate" them about the course. The goal is to share a story about your relationship with the learning objectives of the course. Therefore, unlike research papers, you are expected to write from a first person point of view which includes an introspective examination of your own opinions, feelings, and personal assumptions.

A reflection paper is not a book review . Descriptions of the course readings using your own words is not a reflective paper. Reflective writing should focus on how you understood the implications of and were challenged by the course in relation to your own lived experiences or personal assumptions, combined with explanations of how you grew as a student learner based on this internal dialogue. Remember that you are the central object of the paper, not the research materials.

A reflective paper is not an all-inclusive meditation. Do not try to cover everything. The scope of your paper should be well-defined and limited to your specific opinions, feelings, and beliefs about what you determine to be the most significant content of the course and in relation to the learning that took place. Reflections should be detailed enough to covey what you think is important, but your thoughts should be expressed concisely and coherently [as is true for any academic writing assignment].

Critical Reflection . Writing and Communication Centre, University of Waterloo; Critical Reflection: Journals, Opinions, & Reactions . University Writing Center, Texas A&M University; Connor-Greene, Patricia A. “Making Connections: Evaluating the Effectiveness of Journal Writing in Enhancing Student Learning.” Teaching of Psychology 27 (2000): 44-46; Good vs. Bad Reflection Papers , Franklin University; Dyment, Janet E. and Timothy S. O’Connell. "The Quality of Reflection in Student Journals: A Review of Limiting and Enabling Factors." Innovative Higher Education 35 (2010): 233-244: How to Write a Reflection Paper . Academic Skills, Trent University; Amelia TaraJane House. Reflection Paper . Cordia Harrington Center for Excellence, University of Arkansas; Ramlal, Alana, and Désirée S. Augustin. “Engaging Students in Reflective Writing: An Action Research Project.” Educational Action Research 28 (2020): 518-533; Writing a Reflection Paper . Writing Center, Lewis University; McGuire, Lisa, Kathy Lay, and Jon Peters. “Pedagogy of Reflective Writing in Professional Education.” Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (2009): 93-107; Critical Reflection . Writing and Communication Centre, University of Waterloo; How Do I Write Reflectively? Academic Skills Toolkit, University of New South Wales Sydney; Reflective Writing . Skills@Library. University of Leeds; Walling, Anne, Johanna Shapiro, and Terry Ast. “What Makes a Good Reflective Paper?” Family Medicine 45 (2013): 7-12; Williams, Kate, Mary Woolliams, and Jane Spiro. Reflective Writing . 2nd edition. London: Red Globe Press, 2020; Yeh, Hui-Chin, Shih-hsien Yang, Jo Shan Fu, and Yen-Chen Shih. “Developing College Students’ Critical Thinking through Reflective Writing.” Higher Education Research and Development (2022): 1-16.

Writing Tip

Focus on Reflecting, Not on Describing

Minimal time and effort should be spent describing the course content you are asked to reflect upon. The purpose of a reflection assignment is to introspectively contemplate your reactions to and feeling about an element of the course. D eflecting the focus away from your own feelings by concentrating on describing the course content can happen particularly if "talking about yourself" [i.e., reflecting] makes you uncomfortable or it is intimidating. However, the intent of reflective writing is to overcome these inhibitions so as to maximize the benefits of introspectively assessing your learning experiences. Keep in mind that, if it is relevant, your feelings of discomfort could be a part of how you critically reflect on any challenges you had during the course [e.g., you realize this discomfort inhibited your willingness to ask questions during class, it fed into your propensity to procrastinate, or it made it difficult participating in groups].

Writing a Reflection Paper . Writing Center, Lewis University; Reflection Paper . Cordia Harrington Center for Excellence, University of Arkansas.

Another Writing Tip

Helpful Videos about Reflective Writing

These two short videos succinctly describe how to approach a reflective writing assignment. They are produced by the Academic Skills department at the University of Melbourne and the Skills Team of the University of Hull, respectively.

- << Previous: Writing a Policy Memo

- Next: Writing a Research Proposal >>

- Last Updated: Mar 6, 2024 1:00 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

Guide on How to Write a Reflection Paper with Free Tips and Example

A reflection paper is a very common type of paper among college students. Almost any subject you enroll in requires you to express your opinion on certain matters. In this article, we will explain how to write a reflection paper and provide examples and useful tips to make the essay writing process easier.

Reflection papers should have an academic tone yet be personal and subjective. In this paper, you should analyze and reflect upon how an experience, academic task, article, or lecture shaped your perception and thoughts on a subject.

Here is what you need to know about writing an effective critical reflection paper. Stick around until the end of our guide to get some useful writing tips from the writing team at EssayPro — a research paper writing service

What Is a Reflection Paper

A reflection paper is a type of paper that requires you to write your opinion on a topic, supporting it with your observations and personal experiences. As opposed to presenting your reader with the views of other academics and writers, in this essay, you get an opportunity to write your point of view—and the best part is that there is no wrong answer. It is YOUR opinion, and it is your job to express your thoughts in a manner that will be understandable and clear for all readers that will read your paper. The topic range is endless. Here are some examples: whether or not you think aliens exist, your favorite TV show, or your opinion on the outcome of WWII. You can write about pretty much anything.

There are three types of reflection paper; depending on which one you end up with, the tone you write with can be slightly different. The first type is the educational reflective paper. Here your job is to write feedback about a book, movie, or seminar you attended—in a manner that teaches the reader about it. The second is the professional paper. Usually, it is written by people who study or work in education or psychology. For example, it can be a reflection of someone’s behavior. And the last is the personal type, which explores your thoughts and feelings about an individual subject.

However, reflection paper writing will stop eventually with one very important final paper to write - your resume. This is where you will need to reflect on your entire life leading up to that moment. To learn how to list education on resume perfectly, follow the link on our dissertation writing services .

Unlock the potential of your thoughts with EssayPro . Order a reflection paper and explore a range of other academic services tailored to your needs. Dive deep into your experiences, analyze them with expert guidance, and turn your insights into an impactful reflection paper.

Free Reflection Paper Example

Now that we went over all of the essentials about a reflection paper and how to approach it, we would like to show you some examples that will definitely help you with getting started on your paper.

Reflection Paper Format

Reflection papers typically do not follow any specific format. Since it is your opinion, professors usually let you handle them in any comfortable way. It is best to write your thoughts freely, without guideline constraints. If a personal reflection paper was assigned to you, the format of your paper might depend on the criteria set by your professor. College reflection papers (also known as reflection essays) can typically range from about 400-800 words in length.

Here’s how we can suggest you format your reflection paper:

How to Start a Reflection Paper

The first thing to do when beginning to work on a reflection essay is to read your article thoroughly while taking notes. Whether you are reflecting on, for example, an activity, book/newspaper, or academic essay, you want to highlight key ideas and concepts.

You can start writing your reflection paper by summarizing the main concept of your notes to see if your essay includes all the information needed for your readers. It is helpful to add charts, diagrams, and lists to deliver your ideas to the audience in a better fashion.

After you have finished reading your article, it’s time to brainstorm. We’ve got a simple brainstorming technique for writing reflection papers. Just answer some of the basic questions below:

- How did the article affect you?

- How does this article catch the reader’s attention (or does it all)?

- Has the article changed your mind about something? If so, explain how.

- Has the article left you with any questions?

- Were there any unaddressed critical issues that didn’t appear in the article?

- Does the article relate to anything from your past reading experiences?

- Does the article agree with any of your past reading experiences?

Here are some reflection paper topic examples for you to keep in mind before preparing to write your own:

- How my views on rap music have changed over time

- My reflection and interpretation of Moby Dick by Herman Melville

- Why my theory about the size of the universe has changed over time

- How my observations for clinical psychological studies have developed in the last year

The result of your brainstorming should be a written outline of the contents of your future paper. Do not skip this step, as it will ensure that your essay will have a proper flow and appropriate organization.

Another good way to organize your ideas is to write them down in a 3-column chart or table.

Do you want your task look awesome?

If you would like your reflection paper to look professional, feel free to check out one of our articles on how to format MLA, APA or Chicago style

Writing a Reflection Paper Outline

Reflection paper should contain few key elements:

Introduction

Your introduction should specify what you’re reflecting upon. Make sure that your thesis informs your reader about your general position, or opinion, toward your subject.

- State what you are analyzing: a passage, a lecture, an academic article, an experience, etc...)

- Briefly summarize the work.

- Write a thesis statement stating how your subject has affected you.

One way you can start your thesis is to write:

Example: “After reading/experiencing (your chosen topic), I gained the knowledge of…”

Body Paragraphs

The body paragraphs should examine your ideas and experiences in context to your topic. Make sure each new body paragraph starts with a topic sentence.

Your reflection may include quotes and passages if you are writing about a book or an academic paper. They give your reader a point of reference to fully understand your feedback. Feel free to describe what you saw, what you heard, and how you felt.

Example: “I saw many people participating in our weight experiment. The atmosphere felt nervous yet inspiring. I was amazed by the excitement of the event.”

As with any conclusion, you should summarize what you’ve learned from the experience. Next, tell the reader how your newfound knowledge has affected your understanding of the subject in general. Finally, describe the feeling and overall lesson you had from the reading or experience.

There are a few good ways to conclude a reflection paper:

- Tie all the ideas from your body paragraphs together, and generalize the major insights you’ve experienced.

- Restate your thesis and summarize the content of your paper.

We have a separate blog post dedicated to writing a great conclusion. Be sure to check it out for an in-depth look at how to make a good final impression on your reader.

Need a hand? Get help from our writers. Edit, proofread or buy essay .

How to Write a Reflection Paper: Step-by-Step Guide

Step 1: create a main theme.

After you choose your topic, write a short summary about what you have learned about your experience with that topic. Then, let readers know how you feel about your case — and be honest. Chances are that your readers will likely be able to relate to your opinion or at least the way you form your perspective, which will help them better understand your reflection.

For example: After watching a TEDx episode on Wim Hof, I was able to reevaluate my preconceived notions about the negative effects of cold exposure.

Step 2: Brainstorm Ideas and Experiences You’ve Had Related to Your Topic

You can write down specific quotes, predispositions you have, things that influenced you, or anything memorable. Be personal and explain, in simple words, how you felt.

For example: • A lot of people think that even a small amount of carbohydrates will make people gain weight • A specific moment when I struggled with an excess weight where I avoided carbohydrates entirely • The consequences of my actions that gave rise to my research • The evidence and studies of nutritional science that claim carbohydrates alone are to blame for making people obese • My new experience with having a healthy diet with a well-balanced intake of nutrients • The influence of other people’s perceptions on the harm of carbohydrates, and the role their influence has had on me • New ideas I’ve created as a result of my shift in perspective

Step 3: Analyze How and Why These Ideas and Experiences Have Affected Your Interpretation of Your Theme

Pick an idea or experience you had from the last step, and analyze it further. Then, write your reasoning for agreeing or disagreeing with it.

For example, Idea: I was raised to think that carbohydrates make people gain weight.

Analysis: Most people think that if they eat any carbohydrates, such as bread, cereal, and sugar, they will gain weight. I believe in this misconception to such a great extent that I avoided carbohydrates entirely. As a result, my blood glucose levels were very low. I needed to do a lot of research to overcome my beliefs finally. Afterward, I adopted the philosophy of “everything in moderation” as a key to a healthy lifestyle.

For example: Idea: I was brought up to think that carbohydrates make people gain weight. Analysis: Most people think that if they eat any carbohydrates, such as bread, cereal, and sugar, they will gain weight. I believe in this misconception to such a great extent that I avoided carbohydrates entirely. As a result, my blood glucose levels were very low. I needed to do a lot of my own research to finally overcome my beliefs. After, I adopted the philosophy of “everything in moderation” as a key for having a healthy lifestyle.

Step 4: Make Connections Between Your Observations, Experiences, and Opinions

Try to connect your ideas and insights to form a cohesive picture for your theme. You can also try to recognize and break down your assumptions, which you may challenge in the future.

There are some subjects for reflection papers that are most commonly written about. They include:

- Book – Start by writing some information about the author’s biography and summarize the plot—without revealing the ending to keep your readers interested. Make sure to include the names of the characters, the main themes, and any issues mentioned in the book. Finally, express your thoughts and reflect on the book itself.

- Course – Including the course name and description is a good place to start. Then, you can write about the course flow, explain why you took this course, and tell readers what you learned from it. Since it is a reflection paper, express your opinion, supporting it with examples from the course.

- Project – The structure for a reflection paper about a project has identical guidelines to that of a course. One of the things you might want to add would be the pros and cons of the course. Also, mention some changes you might want to see, and evaluate how relevant the skills you acquired are to real life.

- Interview – First, introduce the person and briefly mention the discussion. Touch on the main points, controversies, and your opinion of that person.

Writing Tips

Everyone has their style of writing a reflective essay – and that's the beauty of it; you have plenty of leeway with this type of paper – but there are still a few tips everyone should incorporate.

Before you start your piece, read some examples of other papers; they will likely help you better understand what they are and how to approach yours. When picking your subject, try to write about something unusual and memorable — it is more likely to capture your readers' attention. Never write the whole essay at once. Space out the time slots when you work on your reflection paper to at least a day apart. This will allow your brain to generate new thoughts and reflections.

- Short and Sweet – Most reflection papers are between 250 and 750 words. Don't go off on tangents. Only include relevant information.

- Clear and Concise – Make your paper as clear and concise as possible. Use a strong thesis statement so your essay can follow it with the same strength.

- Maintain the Right Tone – Use a professional and academic tone—even though the writing is personal.

- Cite Your Sources – Try to cite authoritative sources and experts to back up your personal opinions.

- Proofreading – Not only should you proofread for spelling and grammatical errors, but you should proofread to focus on your organization as well. Answer the question presented in the introduction.

'If only someone could write my essay !' you may think. Ask for help our professional writers in case you need it.

Do You Need a Well-Written Reflection Paper?

Then send us your assignment requirements and we'll get it done in no time.

How To Write A Reflection Paper?

How to start a reflection paper, how long should a reflection paper be, related articles.

.webp)

- Other Guides

- How to Write a Reflection Paper: Definition, Outline, Steps & Examples

- Speech Topics

- Basics of Essay Writing

- Essay Topics

- Other Essays

- Main Academic Essays

- Research Paper Topics

- Basics of Research Paper Writing

- Miscellaneous

- Chicago/ Turabian

- Data & Statistics

- Methodology

- Admission Writing Tips

- Admission Advice

- Student Life

- Studying Tips

- Understanding Plagiarism

- Academic Writing Tips

- Basics of Dissertation & Thesis Writing

- Essay Guides

- Research Paper Guides

- Formatting Guides

- Basics of Research Process

- Admission Guides

- Dissertation & Thesis Guides

How to Write a Reflection Paper: Definition, Outline, Steps & Examples

Table of contents

Use our free Readability checker

Reflection paper is an opportunity to look at a topic, concept or event and analyze it. It can involve personal introspection, observations of a particular situation or event, and even critical analysis of other works. Students should share their emotions, opinions, and reflections, exploring how the subject matter has impacted their thinking and personal growth. Unlike other types of essays, a reflection paper is usually written in the first person.

Whether your teacher assigns an internship reflection paper or any other type of a reflection paper, don't write about the image in the mirror. On the contrary, study your thoughts on a given topic. Most students first encounter this type of writing when describing how they spent summer. However, this type of academic writing can cover much more. In this article, you will find everything you need to know about this type of academic piece!

What Is a Reflection Paper: A Detailed Definition

Reflection paper refers to a type of academic writing where you should analyze your personal life, and explore specific ideas of how your changes, development, or growth turned out. Consider this piece like diary entries. Except that others will be reading them. So it should have consistency, reasonable structure, and be easy to understand. In this respect, this work is very similar to any other academic assignment. Simply put, a reflective paper is a critique of life experiences. And with proper guidance, it is not very difficult to compose. Moreover, there are different types of reflection papers . After all, you can reflect on different things, not only your own experience. These types are:

- Educational reflection paper In this type of work you must write feedback about a book, movie, or seminar you attended.

- Professional paper It is usually written by people who study or work in education or psychology.

- Personal paper It goes without saying that this type is all about your own feelings and thoughts on a particular topic.

Reflection Paper Format: Which One to Choose

Reflection paper format can vary slightly depending on who your audience is. It is not uncommon that your paper format will be assigned specifically by your professor. However, some essential structural elements are typical for MLA, APA, or Chicago style formatting. These include introduction, body, and conclusion. You can find more information on paper formats in our blog. As always, paper writers for hire at StudyCrumb are at your hand 24/7.

How to Start a Reflection Paper: Guidelines

Here, we will explain how to begin a reflection paper. Working on how to start a body paragraph , review criteria for evaluation. This first step will help you concentrate on what is required. In the beginning, summarize brief information with no spoilers. Then professionally explain what thoughts you (if it is a personal paper) or a writer (if educational or professional paper) touch upon. But still, remember that essays should be written in first person and focus on "you."

Reflection Paper Outline

The best reflection paper outline consists of an introduction that attracts attention. After introduction, the plan includes the main body and, finally, conclusions. Adherence to this structure will allow you to clearly express your thinking. The detailed description of each part is right below.

Reflection Paper Introduction: Start With Hook

Reflection paper introduction starts with a hook. Find a way to intrigue your reader and make them interested in your assignment before they even read it. Also, you should briefly and informatively describe the background and thesis statement. Make it clear and concise, so neither you nor your reader would get confused later. Don't forget to state what it is you're writing about: an article, a personal experience, a book, or something else.

Number of Body Paragraphs in a Reflective Paper

Reflective paper body paragraphs explain how your thinking has changed according to something. Don't only share changes but also provide examples as supporting details. For example, if you discuss how to become more optimistic, describe what led to this change. Examples serve as supporting structure of your assignment. They are similar to evidence in, say, an argumentative essay. Keep in mind that your work doesn't have to be disengaged and aloof. It is your own experience you're sharing, after all.

How to End a Reflection Paper

In the short reflection paper conclusion, you summarize the thesis and personal experience. It's fascinating that in this academic work, you can reflect forward or backward on your experience. In the first case, you share what role the essay plays in your future. In the second case, you focus more on the past. You acknowledge the impact that the essay's story has on your life. Reflect on how you changed bit by bit, or, maybe, grew as a person. Perhaps, you have witnessed something so fascinating it changed your outlook on certain aspects of your life. This is how to write conclusion in research paper in the best way possible.

How to Write Reflection Paper: Full Step-By-Step Guide

Writing reflection paper could be initiated by the teacher at college. Or we can even do it by ourselves to challenge our evaluation skills and see how we have changed. In any case, it's not an issue anymore since we've prepared a super handy guide. Just follow it step by step, and you will be amazed at the result.

Step 1. Answer the Main Questions Before Writing a Reflection Paper

A reflection paper means you should provide your thoughts on the specific topic and cover some responses. So before writing, research the information you want to apply and note every idea. If you're writing an educational or professional paper ask yourself several questions, for example:

- What was my viewpoint before reading this book?

- How do I consider this situation now?

- What does this book teach me?

If your goal is to reflect on personal experience, you can start with asking questions like:

- What was your viewpoint before the experience?

- How did this experience change your viewpoint?

The more details you imagine, the better you can answer these questions.

Step 2. Identify the Main Theme of Your Reflection Paper

Reflection papers' suggested topics can be varied. Generally, it could be divided into four main categories to discuss:

- Articles or books.

- Social events.

- Persons or famous individuals.

- Personal experiences.

In any case, it's good to show your own attitude to a topic, and that it affects yourself. It is also suited to write about your own negative experiences and mistakes. You need to show how you overcame some obstacle, or maybe you're still dealing with the consequences of your choices. Consider what you learnt through this experience, and how it makes you who you are now.

Step 3. Summarize the Material for Reflection Paper

At this step of reflective paper, you can wait for inspiration and brainstorm. Don't be afraid of a blank sheet. Carefully read the topic suggested for the essay. Think about associations, comparisons, facts that immediately come to mind. If the teacher recommended particular literature, find it. If not, check the previous topic's background. Remember how to quote a quote that you liked, but be sure to indicate its author and source. Think of relevant examples or look for statistics, and analyze them. Just start drafting a summary of everything you know regarding this topic. And keep in mind, that main task is to describe your own thoughts and feelings.

Step 4. Analyze Main Aspects of Reflection Paper

A whole reflection paper's meaning lies in putting theory and your experience together. So fill in different ideas in your piece step by step until you realize there's enough material. If you may find some particular quotes, you should focus on your viewpoint and feelings. Who knows, maybe there is some relatable literature (or video material) that can highlight your idea and make it sound more engaging?

The Best Tips on Writing a Reflection Paper

We prepared tips on writing reflection paper to help you find evidence that your work was excellently done! Some, of course, go without saying. Edit your piece for some time after writing, when you cooled down a bit. Pay attention to whether your readers would be interested in this material. Write about things that not only are interesting for you, but have a sufficient amount of literature to read about. Below you will find more tips on various types of writing!

Tips on Writing a Critical Reflection Paper

Role of a critical reflection paper is to change your opinion about a particular subject, thus changing your behaviour. You may ask yourself how your experience could have been improved and what you have to do in order to achieve that. It could be one of the most challenging tasks if you choose the wrong topic. Usually, such works are written at the subject's culmination. This requires intensive, clear, evaluative, and critical context thinking.

- Describe experience in detail.

- Study topic of work well.

- Provide an in-depth analysis.

- Tell readers how this experience changed you.

- Find out how it will affect your future.

Tips on Writing a Course Reflection Paper

Course reflection paper is basically a personal experience of how a course at your college (or university) has affected you. It requires description and title of course, first of all.

- Clearly write information you discussed, how class went, and reasons you attended it.

- Identify basic concepts, theories and instructions studied. Then interpret them using real-life examples.

- Evaluate relevance and usefulness of course.

How to Write a Reflection Paper on a Book

A reflection paper on a book introduces relevant author's and piece's information. Focus on main characters. Explain what problems are revealed in work, their consequences, and their effectiveness. Share your experience or an example from your personal life.

How to Write a Reflection Paper on a Project

Main point of a reflection paper on a project is to share your journey during a process. It has the same structure and approach as previous works. Tell all about the obstacles that you needed to overcome. Explain what it took to overcome them. Share your thoughts! Compare your experience with what could have been if there were another approach. But the main task here is to support the pros or cons of the path you've taken. Suggest changes and recognize complexity or relevance to the real world.

How to Write a Reflection Paper on an Interview

A reflection paper on an interview requires a conclusion already in your introduction.

- Introduce the person.

- Then emphasize known points of view, focusing on arguments.

- Later, express what you like or dislike about this idea.

It is always a good idea to brainstorm and research certain interview questions you're planning on discussing with a person. Create an outline of how you want your interview to go. Also, don't digress from a standard 5-paragraph structure, keep your essay simple. You may need a guide on how to write a response paper as well. There is a blog with detailed steps on our website.

Reflection Paper Example

Before we've explained all fundamental basics to you. Now let's look at a reflection paper example. In this file, you'll find a visual structure model and way of thinking expressed.

Reflection Paper: Main Takeaways

A reflection paper is your flow of thoughts in an organized manner concerning any research paper topics . Format is similar to any other academic work. Start with a strong introduction, develop the main body, and end with conclusions. With the help of our article, you can write this piece only in 4 steps.

Our academic assistants are up for the task! Just pick a twitter to your liking, send them your paper requirements and they'll write your reflection paper for you!

Frequently Asked Questions About Reflection Paper

1. how long should a reflection paper be.

A reflection paper must be between 300 and 750 words. Still, it always depends on your previous research and original task requirements. The main task is to cover all essential questions in the narrative flow. So don't stick directly to the work's volume.

2. Do reflection papers need a cover sheet or title page?

A cover sheet or title page isn't necessary for reflection papers. But your teacher may directly require this page. Then you should include a front-page and format it accordingly.

3. Do I need to use citations and references with a reflection paper?

No, usually, you don't have to cite in your reflection paper. It should be only your personal experience and viewpoint. But in some cases, your teacher may require you to quote a certain number of sources. It's necessary that the previous research was completed, so check it beforehand.

4. What is the difference between a reflection paper and a reaction paper?

The research paper definition differs from reaction paper. Basically, the main point is in-depth of discussion. In the first case, you must fully describe how something affected you. While in the second one, it is just asked to provide a simple observation.

Daniel Howard is an Essay Writing guru. He helps students create essays that will strike a chord with the readers.

You may also like

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Am J Pharm Educ

- v.81(1); 2017 Feb 25

Using Reflective Writing as a Predictor of Academic Success in Different Assessment Formats

Cherie tsingos-lucas.

a University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia

b Graduate School of Health, University of Technology, Sydney, Sydney, Australia

Sinthia Bosnic-Anticevich

Carl r. schneider, lorraine smith.

Objectives. To investigate whether reflective-writing skills are associated with academic success.

Methods. Two hundred sixty-four students enrolled in a pharmacy practice course completed reflective statements. Regression procedures were conducted to determine whether reflective-writing skills were associated with academic success in different assessment formats: written, oral, and video tasks.

Results. Reflective-writing skills were found to be a predictor of academic performance in some formats of assessment: written examination; oral assessment task and overall score for the Unit of Study (UoS). Reflective writing skills were not found to predict academic success in the video assessment task.

Conclusions. Possessing good reflective-writing skills was associated with improved academic performance. Further research is recommended investigating the impact of reflective skill development on academic performance measures in other health education.

INTRODUCTION

Research has shown that fostering reflective skills in health professional education can assist students to improve their clinical decision-making skills and enhance academic performance. 1,2 Furthermore, enhancing reflective writing within health education has been at the forefront of the published literature in recent years. 1,3-5 The ability to reflect on a deeper level is a desirable attribute for all health professionals. 5-11 Reflective capacity is regarded as a skill to enhance learning from previous knowledge and experience in order to improve future clinical practice and clinical reasoning 2,5,7,10,12 In particular, reflective writing can be used as a tool to enhance reflective capacity. 9,13

Furthermore, in the medical field, awareness of the patient and of the health professional’s own mental processes can be enhanced through the reflective-writing process. This can potentially improve clinical decision-making ability. 14 In many cases, academic performance in health professional education is an indicator of effective clinical decision-making skills. Therefore, fostering reflective-writing skills may be a skill associated with improvement in clinical decision-making skills and academic performance.

Scholars posit that developing reflective-writing capacity will foster deeper learning and reflective thinking, which may lead learners to make better informed judgments and increase their ability to make optimal clinical decisions. 1,5,8,9,15,16 Previous research has shown that using the skills of reflective writing improves academic and/or clinical performance 17,18 and is perceived by students as a valuable exercise to enhance reflective learning, thus potentially improving their performance of future clinical tasks. 3,19 Furthermore, reflective narratives used in medical education have been shown to improve clinical-reasoning skills by nurturing the skills of observation, analysis, and interpretation. 1,20 Thus, effective reflective-writing skills may be beneficial for educating the pharmacy student and are fundamental for developing not only the reflective practitioner, but may assist with clinical reasoning and academic performance.

Reflective writing may take the forms of reflective statements, essays, portfolios, journals, diaries, or blogs. 9 Evidence of support for the use of reflective writing in portfolios and journals in health professions are numerous. 14,21-30 These tools are used to foster students’ thinking to challenge their biases, assumptions, and firmly held beliefs. 14 Moreover, reflective-writing instruments in the form of statements have been used as an effective educational tool to assess medical and surgical resident learning in the medical curriculum. 31 As some have advocated, using tools of reflective writing and working towards becoming a reflective practitioner should be considered a core attribute for professional development. 1,7,18,20,25,32-34 Health professions are now insisting on students developing reflective-writing abilities to document continuing professional development and competencies. 1,35

Despite the importance placed on reflective-writing skill development in health professional education, some researchers report “tension” between what students will write as an honest reflection and what they will write if a grade is associated with the task. This was illustrated in a Belgian study that investigated the perceptions of 142 midwifery students toward completing reflective writing exercises during their clinical training sessions. While most respondents perceived the reflective writing exercises as an effective learning tool, others reported that they wrote reflections that they believed would gain them a better assessment score. 3 This was also illustrated in another qualitative study involving eight focus groups of second-year UK medical students, which reported similar issues regarding the “tension” caused by grading written reflections. 36 Nevertheless, students from both studies perceived the exercises as a valuable learning experience that could enhance their performance of future clinical tasks and facilitate deeper understanding and learning. 3,36 Similarly, a study introducing reflective-writing processes into an undergraduate pharmacy curriculum indicated that students perceived this type of learning as challenging. 19 However, the majority of the students did perceive this learning exercise as valuable and indicated that the skill of reflective practice would be beneficial for improvement in other essential skill development including counseling and clinical decision-making. 19

Therefore, it can be argued that effective reflective-writing skills can be used as a tool to promote deeper understanding and learning, and thereby enhance clinical decision-making skills and improve academic performance. Research suggests that reflective ability is not necessarily an inherent skill, but can be taught through various strategies, models, and guidelines. 37-44 Moreover, the development of reflective capacity has been described as necessary for experiential learning in the practice setting. 3 Thus, developing and evaluating this fundamental skill should be a consideration in undergraduate and graduate health professions educational programs, 9 and further scaffolding these skills in practice settings may benefit immediate and long-term reflective learning. 3,5,8,9,11,19

Although reflective practice activities may enhance clinical reasoning skills, 2,45 there is little published research investigating the effect of reflective-writing skills on particular types of assessments. The aim of this research was to explore the relationship between reflective writing and academic performance in a cohort of undergraduate pharmacy students.

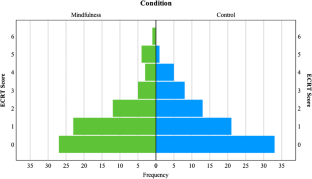

The sampling frame for this research was 264 second-year undergraduate pharmacy students (92 male students, 172 female students) enrolled in a pharmacy practice course. The classroom or laboratory structure used in this course involved 10 groups of 26-27 students. Each group was facilitated by a practicing pharmacist clinical educator affiliated with the university. The pharmacy practice unit of study was an introductory unit that explored disease states and management options, including nonpharmacological recommendations. It focused on methods of delivering patient care to individual patients as well as to the wider community with an emphasis on primary care.

The data from this project were analyzed as part of a larger research project 5 in which approval for the study was sought and granted by the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee. Approval for integrating reflective activities into curriculum was also received from the school’s Learning and Teaching Committee. As students were required as part of their regular course assessment to complete a reflective-writing task, all students in the second-year curriculum participated in this study.

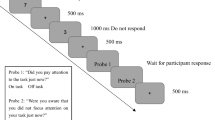

In 2014, a reflective-writing module was introduced into a second-year undergraduate pharmacy curriculum as part of the Reflective Ability Clinical Assessment (RACA). 5 We have described the process of the integration of reflective practice activities into the curriculum, and the structure of the Reflective Ability Clinical Assessment (RACA) and its evaluation in more detail in our previous paper. 5 Briefly, The RACA aimed to enhance the reflective-thinking capacity of students and involved three components: a clinical scenario; a video podcast, and a reflective writing component. The RACA tasks required students to develop a role play, counsel another student, video tape the counseling session (for a maximum of five minutes), and then reflect on the experience through an introspective reflective-writing task. The reflective-writing task took the form of a reflective statement ( Appendix 1 ).

Students were assigned one of 10 health problems that could be treated with nonprescription medication or nonpharmacological advice. These health problems included heartburn, sunburn, impetigo, worms, scabies, insomnia, head lice, traveler’s diarrhea, chicken pox, and ticks. The students were then asked to research the problem (signs, symptoms, required referrals, advice), develop a typical clinical discussion/counseling session between a pharmacist and a patient, counsel (as the pseudo pharmacist) another student (serving as the pseudo patient) and write reflectively about the task. As part of the assignment, students were also encouraged to view and reflect on each other’s videos to enhance self- and peer-reflection ( Figure 1 ). The objective of the end-of-semester oral examination was to assess effective counseling and clinical decision-making skills.

Utilization of video podcasts to enhance reflective capacity (self and peer reflection) of pharmacy students. 5

While the video podcast task (which counted 8% of the course grade) provided students with the opportunity to reflect on their counseling and clinical competency skills and those of a peer, it did not involve clinical decision-making skills as the student had prior knowledge of the clinical scenario. The main purpose of the video podcast task was to provide an opportunity for counseling practice prior to the end-of-semester oral assessment. No limit was placed on the number of podcasts recorded before uploading the best one to the Blackboard Learning Management System (LMS). Thus, this activity provided an opportunity for students to counsel each other several times. The video podcast counseling task was submitted mid-semester, along with the reflective statement.

The reflective statement consisted of guided questions ( Appendix 1 ) 5 and was assessed by one external assessor to ensure grading consistency. The external assessor had expertise in the area of reflective writing and possessed extensive clinical pharmacy experience. The statements were assessed via a reflective rubric which was developed from Boud and colleagues’ 40 stages of reflection and Mezirow’s 46 categories of reflection. Elements of the rubric were also drawn from Wetmore and colleagues’ reflective rubric, used in dental education ( Table 1 ). 47 The reflective statement counted 7% of the student’s overall grade for the unit of study.

Reflective Rubric to Assess Reflective Writing in Pharmacy Education 11 , a

The oral assessment was a high-stakes examination completed at the end of the semester that accounted for 30% of the overall grade for the unit of study. Students were required to pass this assessment in order to pass the unit of study. While the topic area is provided earlier, the assessment does not provide students with prior knowledge of the case, patient background, signs and/or symptoms. In contrast to the video podcast assessment task, the oral assessment required the student to make appropriate clinical decisions based on gathering patient information during a five-minute timeframe.

After the oral assessment, all students from the cohort completed the end of semester written examination, which included both short-answer and multiple-choice questions (single best answer). This assessment accounted for 55% of the total grade for the unit of study.

S cores from all assessment and examination tasks were analyzed using SPSS, version 20 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive analyses were performed to provide an overview of the scores allocated for the four dependent variables (1) overall marks for the unit of study excluding the reflective statement scores; (2) written examination scores (including short answer and multiple-choice); (3) video podcasts score and (4) end of semester oral examination score. The predictor variable used the reflective-writing task scores. Simple regression procedures were employed to determine if reflective-writing skills predicted academic success in these different assessment formats. The reflective statement scores were excluded in the regression analyses, as these scores were used as a predictor variable. An adjusted overall score that excluded the reflective statement scores was used for this research. Significance was set at p <.05.

From a sample size of 264 undergraduate students enrolled in the Pharmacy Practice course, 259 (98%) students completed the video podcasts counseling activity and a reflective writing task. Two hundred fifty-eight (98%) students completed the written end-of-semester examination ( Table 2 ).

Descriptive Statistics: Scores for Different Formats of Assessment in a Second Year Undergraduate Pharmacy Curriculum

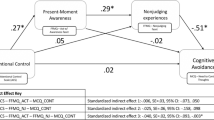

The results from simple regression analyses explaining 14% of its variance (R 2 = 0.14) with overall academic achievement are as follows:

- (i) Are reflective writing skills a predictor of academic success in the Overall Marks for one unit of study?

Reflective writing skills was found to be a predictor of academic success in the Overall marks for the Unit of Study, F(1,256)= 25.2, p <0.01

- (ii) Are reflective writing skills a predictor of academic success in the end of semester written examination?

Reflective writing skills was found to be a significant predictor of academic success in the end of semester written examination, F (1, 256) = 21.6 , p < 0.01

- (iii) Are reflective writing skills a predictor of academic success in the video counseling format of an assessment?

Reflective writing skills did not predict academic success in the video podcast counseling task, ( p= 0.08).

- (iv) Are reflective writing skills a predictor of academic success in the end of semester oral assessment?

Reflective writing skills was found to be a predictor of academic success in the end of semester Oral examination, F(1,257)= 8.5, p <0.01

In this study we examined the predictive relationship between reflective-writing skills and academic performance in four formats of assessment. The significant findings suggest that possessing reflective-writing skills is a predictor of academic success on the written examination and in the end-of-semester oral assessment. Interestingly, reflective-writing skills were not a predictor of academic success in the video podcast assessment task. There are two possible explanations for this. First, research has shown that reflective-writing skills may enhance decision-making skills. 48 Assessing the video podcast did not require the student to make any “on the spot” clinical decisions as the student had thoroughly researched the case prior to the counseling session. Conversely, the end-of-semester oral assessment did require students to demonstrate their clinical decision-making skills. Second, the video podcast assessment task was completed midsemester, prior to writing the reflective statement, and perhaps this contributed to the nonsignificant result, as reflection on that task was completed later. This study reported reflective writing had a stronger association with the written component compared to the oral assessment task. This may have been due to the fact that written skills were involved in completing the reflective task. In contrast, there were no written skills involved in completing the oral assessment.

These results, although significant, do not indicate a particularly strong effect size (14% of its variance with overall academic achievement). It is possible that the traditional assessment modalities that are employed in pharmacy education are by and large not directly assessing reflective skills. If educators wish to develop this skill in the health professions, we need to address this in our assessment practices. 11 Furthermore, the low effect size could be due to more specific details of the assessment strategies and to grades being allocated to content knowledge, written, and verbal communication skills compared to grades allocated specifically for reflective ability. The limitations of this study were that it involved only one course in an undergraduate curriculum at a single university and that it only involved pharmacy students.

This study advances understanding from previous research in the area of reflective learning of health professionals and the importance of considering the integration of reflective-writing skills into medical and other health professions educational curricula. Pharmacy students are not a homogenous group of future health professionals and this is also the case with the medical and other health professions. The use of reflective tools has been shown to improve decision-making skills. 45 Furthermore, it has been suggested that tools which encourage the reflective process allow for continuous evaluation of learning and development 48 as it encourages critiquing of practice, 49 thus developing the health professional into a reflective practitioner. 49 The findings from this study support the integration of reflective writing into health professional education.

Perhaps the greatest pedagogical challenge for educators of health professionals is how we can help them to write reflectively. Fostering students’ reflective writing skills may be one solution to further developing their critical-thinking and problem-solving skills so they will be able to make better informed clinical judgments. Reflective-writing skills are not necessarily inherent and therefore may be developed through inclusion in health care education programs. 20,38 For this to occur, a reflective framework or model may need to be further developed by health professional education systems to provide a springboard for fostering effective reflective writing. 9 Ideally these skills should develop over the course of the degree; therefore, time allocated within the curriculum to foster these skills may be a necessary consideration for educators. 9 Moreover, evaluating the effectiveness of such a fundamental skill through reflective rubrics may further enhance reflective capacity, particularly if reflective rubrics are provided to students prior to reflective-writing activities. 11 Also, well-designed reflective rubrics may assist in providing appropriate guidance for desired learning outcomes, such as enhanced reflective capacity. 11,50

Evidence from this study supports the notion that reflective-writing skills may be associated with improvement in pharmacy students’ clinical decision-making capacity and academic performance. It therefore stands to reason that further research into the effects of various reflective activities in other areas of health education, where effective clinical-reasoning ability is also an important attribute, should be considered.

CONCLUSIONS