Transformational tourism – a systematic literature review and research agenda

Journal of Tourism Futures

ISSN : 2055-5911

Article publication date: 22 June 2022

Issue publication date: 22 September 2022

This paper aims to examine critically the literature on transformational tourism and explore a research agenda for a post-COVID future.

Design/methodology/approach

A systematic review of the transformational tourism literature is performed over a 42-year period from 1978 to 2020.

Further research is required in terms of how transformative experiences should be calibrated and measured both in qualitative and quantitative terms, particularly from the perspective of how tourists are transformed by their experiences. Similarly, the nature and depth of these transformative processes remain poorly understood, particularly given the many different types of tourism associated with transformative experiences, which range from religious pilgrimages to backpacking and include several forms of ecotourism.

Practical implications

Future research directions for transformational tourism are discussed with regard to how COVID-19 will transform the dynamics of tourism and travel, including the role of new smart technologies in the creation of enhanced transformational experiences, and the changing expectations and perceptions of transformative travel in the post-COVID era. In addition, the researchers call for future studies on transformational tourism to explore the role of host communities in the delivery of meaningful visitor experiences.

Originality/value

Transformational tourism is an emerging body of research, which has attracted a growing level of interest among tourism scholars in recent years. However, to this date, a systematic review of published literature in this field has not been conducted yet in a holistic sense. This paper offers a framework for future research in this field.

- Transformational tourism

Literature review

- Research agenda

Nandasena, R. , Morrison, A.M. and Coca-Stefaniak, J.A. (2022), "Transformational tourism – a systematic literature review and research agenda", Journal of Tourism Futures , Vol. 8 No. 3, pp. 282-297. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-02-2022-0038

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2022, Roshini Nandasena, Alastair M. Morrison and J. Andres Coca-Stefaniak

Published in Journal of Tourism Futures . Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode .

Introduction

Although transformational tourism would seem to be a novel emerging field of research ( Reisinger, 2013 ), the roots of this concept can be arguably traced back to Victorian England (e.g. the Grand Tour), when leisure-related travel was often linked to self-change and self-exploration. Indeed, authors in the 17th and 18th century, including James Boswell, Samuel Johnson and Mariano Vasi, among others, provided reflective accounts of their travels in continental Europe ( Knowles, 2013 ). From a more scholarly perspective, Mezirow's (1978) transformational theory set the foundations of what later evolved into transformational tourism with Bruner (1991) and Kotler (1998) as its pioneers. Today, scholarly research guided by transformational learning theory (see, for instance, Mezirow, 1991 , 2000 ; or Hobson and Welbourn, 1998 ) is well established and early tourism scholars built on these foundations to explore the therapeutic and experiential elements of travel ( Kotler, 1998 ). More recently, Ross (2010) defined transformative travel and tourism in terms of their aim to “honour the delicate interplay between the self and anyone who is different or the ‘other’ during the travel” (p. 55), with Lean (2012) arguing the key role of physical travel in this process.

Different aspects of transformational tourism have been explored adopting perspectives that have included existential-humanistic approaches ( Kirillova, 2017 ), co-creation ( Wengel et al. , 2019 ), volunteer tourism ( Knowlenberg et al. , 2014 ), pilgrimage tourism ( Nikjoo et al. , 2020 ), ecotourism ( Pookhao,2014 ), the sharing economy ( Guttentag, 2019 ), experience development ( Wolf et al. , 2017 ) and host–tourist relationships ( Lean, 2012 ; Soulard et al ., 2019 ; Robledo and Batle, 2017 ).

Reisinger (2013) defined transformational tourism as tourism that delivers “very rich and very deep sensual and emotional transformational experiences that enable people to achieve their full potential as unique and authentic human being” (p. 31). In spite of this tentative attempt to define the concept, the connection between lasting personal transformations and visitor experiences in the context of tourism remains poorly understood. This article seeks to contribute to existing knowledge through a bibliographic analysis of the literature in this field and a research agenda for future scholarly work beyond the on-going COVID-19 pandemic and building on similar systematic literature reviews (SLRs) on this topic published recently ( Teoh et al. , 2021 ), though adopting a more comprehensive approach to the literature beyond the merely experiential elements of this field of research. The research agenda suggested is deliberately thought-provoking in its stance, particularly at a stage when the world is beginning to emerge from one of the most traumatic global health crises in living memory. Travel and tourism have been one of the worst-hit sectors of the economy ( Škare et al. , 2021 ). However, the sector is uniquely positioned to capitalise on the use of much sought transformational experiences to drive strategies for recovery ( Abbas et al. , 2021 ; Pasquinelli et al. , 2022 ) and re-think the strategic positioning of tourism destinations adopting innovative future-based approaches ( Korstanje and George, 2022 ; Assaf et al. , 2022 ). First, the methodology of the systematic literature search is explained, with its main findings outlined. This is then followed by a review of the literature on transformational tourism and a proposed research agenda.

Systematic literature search methodology

Building on earlier literature reviews by Stone and Duffy's (2015) and, more recently, Teoh et al. (2021) , an SLR of transformational tourism (TT) was conducted as part of this study with the aim of eliciting key publications in this field as well as different theoretical perspectives and conceptual frameworks in this context. This SLR combined Davis et al .’s (2014 ) standard five-step Evidence-Based practice in Medicine (EBM) approach with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis) approach proposed by Moher et al. (2009) , as shown in Figure 1 . In line with this, Scopus and WoS (Web of Science) were chosen as the sources for the literature search over a 42-year period from January 1978 to July 2020.

First, a set of keywords linked to transformational tourism was selected for the systematic literature search. In order to do this, a selection of seminal scholarly works in this field was made first. These seminal works included Reisinger's (2013 and 2015) edited books on “Transformational Tourism (Tourist and Host perspectives)”, where various typologies of tourism are explored from a transformational perspective. In addition to these two books, two articles were selected ( Sterchele, 2020 ; Pung et al. , 2020 ), as they included the most up-to-date literature reviews at the time. Similarly, the first article to coin the concept of transformational tourism ( Bruner, 1991 ) was also selected. A content analysis of these publications was then conducted to elicit search keywords relevant to transformational tourism. Additionally, the five most-cited journal articles on transformational tourism were used as part of this content analysis to develop a set of keywords, which were then used for the systematic literature search process. The terms “transformative” and “transformational” were selected as some of the most often used keywords in these scholarly works. However, given that transformative experiences often involve a process of defining or re-defining an individual's self-identity, the following keywords were also deemed relevant to this study, based on the analysis of the publications cited above: “self-changing”; “self-development”; “self-improvement”; “self-responsibility”; “self-fulfilment”; “self-realisation”; “self-reflexive”; “self-monitoring”; “self-transformation”; “personal transformation”; “personal development”; “personal identity”; “transformational self”; “change in oneself”; “reflection on oneself”; “being true to oneself”; “immersing oneself”; “finding oneself”; and “life-changing”. Similarly, and given the different types of tourism often linked to transformational processes, the following search keywords were also adopted as part of this content analysis: “volunteer”; “ecotourism”; “adventure”; “backpacker”; “backpacking”; “yoga”; “religious”; “pilgrim”; “pilgrimage”; “wellness”; “wellbeing”; “well-being”; “spiritual”; “culture”; and “cultural heritage”.

The article search was performed by title, abstract and keywords, using Boolean operators “OR” and “AND” with an asterisk (“*”-proximity operator) to ensure that all alternative terms were captured. In addition to this, and given the limited amount of “hits” achieved initially, a number of search keyword combinations were implemented as part of the search query. For instance, “religious* Tourism” OR “religious* travel” AND “transform*” OR “life-changing” OR “self-change” OR “self-reflect” OR “personal transformation” OR “identify the life” were used as part of this exercise.

Figure 2 outlines the process followed in this systematic search of the literature on transformational tourism. For each search criteria, the number of scholarly sources found is indicated (e.g. n = 51). Only books and articles in peer-reviewed journals were considered in this systematic literature search. Editorial articles published in academic journals were not included in the analysis.

Overall, 194 scholarly sources related to transformational tourism were found to have been published between January 1978 and June 2020, following on from a preliminary screening process for validity and applicability to this study. Overall, it was found that scholarly interest in transformational tourism was rather embryonic among tourism scholars until 2007, with a significant growth in research activity between 2018 and 2020, which accounted for more than half of the total available documents, as shown in Figure 3 .

Research topics in transformational tourism

Further analysis of the data ( Figure 4 ) showed that 34 of these scholarly works were in pilgrimage/religious/spiritual tourism, with others related to cultural and heritage tourism (31), ecotourism (27), volunteer tourism (25), wellness/wellbeing/yoga tourism (14), backpacking tourism (9), adventure tourism (7) and dark tourism (5).

A qualitative analysis of keywords used was also performed. This is illustrated in the form of a network visualisation in Figure 5 . The analysis rendered 102 scholarly outputs with the highest level of connection with transformational tourism. This rendered 11 clusters and 364 links, with a total link strength value of 372. Higher weights rendered larger circle labels for “transformation”, “transformative travel”, “tourism development”and “sustainability”. For example, 13 items, including “memorable experience” and “transformational learning”, represented one cluster. On the other hand, 6 items, including “tourist behaviour” and “spiritual tourism”, represented 11 clusters, as shown in Table 1 .

Sources of scholarly works in transformational tourism

The highest proportion of journal articles on transformational tourism was published in Annals of Tourism Research ( Table 2 ). Other journals contributing to this field included, in descending order, Tourism Recreation Research , Journal of Sustainable Tourism , International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage , Current Issues in Tourism and International Journal of Tourism Research . A further 62 scholarly sources were published in a variety of other journals, excluding books and book chapters.

Research focus on transformational tourism

Qualitative research tended to dominate (47%) scholarly works on transformational tourism. This was followed by conceptual approaches (26%). It is noteworthy that only 12% of published journal articles on this topic involved quantitative research, though the lack of appropriate measurement scales and indexes may have influenced this.

A substantial proportion of research related to transformational tourism has tended to focus on aspects related to tourism demand (47%), including tourist behaviour, visitor experiences and transformational processes (e.g. personal and emotional changes, self-transformation). From a supply perspective, research on transformational tourism centred on tourism destinations accounted for 26% of scholarly output, with research focusing on host communities, local stakeholders, entrepreneurs, culture, economic development and environmental impacts accounting for 50 articles. In turn, conceptual research accounted for only 12% of scholarly output, with other categories seemingly rather unexplored, particularly, as regard sustainability (1%).

The 194 scholarly outputs identified by this systematic literature search could be broadly grouped into four themes, namely: tourism experiences; leadership; responsible tourism and the United Nations' sustainable development goals framework.

Tourism experiences

Visitor experiences contribute to the thought processes that result in transformational outcomes for individuals. These experiences may revolve around the socio-cultural exchange, escapism, risk-taking activities, facing challenges, gaining confidence, personal development in new roles and controlling negative emotions such as fear, anger and anxiety. Coghlan and Gooch (2011) have shown that Mezirow's (2000) transformation steps effectively link with these types of experiences well beyond volunteer tourism. Similarly, interaction with local communities at tourism destinations, the development of new relationships and reflecting on a new understanding of social realities around the world have been shown to contribute to these processes in a variety of contexts, including ecotourism ( Walter, 2016 ; Jernsand, 2017 ), voluntourism ( Lee and Woosnam, 2010 ; Coghlan and Gooch, 2011 ; Zavitz and Butz, 2011 ; Alexander, 2012 ; Adams, 2013 or Muller et al. , 2020 ), pilgrimage and spiritual tourism ( Bond et al. , 2015 ; Kurmanilyeva et al. , 2014 ), backpacker tourism ( Bosangit et al ., 2015 ; Yang et al. , 2018 ), wellness, wellbeing and yoga tourism ( Thal and Hudson, 2019 ; Dillette et al. , 2019 ; Voigt et al. , 2011 ; Kim et al. , 2019 ), adventure tourism ( Allman et al. , 2009 ; Gilbert and Gillett, 2014 ), cultural and heritage tourism ( Yamamura et al. , 2006 ; Marschall, 2008 ) and dark tourism ( Sharma and Rickly, 2019 ; Zheng et al. , 2020 ).

Similarly, transformative processes at the individual level have been linked by research studies to visitor experiences where escapism was a key motivation ( Chen et al. , 2014 ; Lochrie et al. , 2019 ), breaking away from daily routines and responsibilities ( Adams, 2013 ), where feelings of personal freedom induced by travel remained at the core of visitors' enjoyment ( O'Reilly, 2006 ). For instance, research by Deville and Wearing (2013) examined ecotourism's transformational potential in the context of organic farms, where budget travellers interacted with local communities over lengthy periods of time, resulting in strong bonds forged with those host communities. Moreover, research by Jernsand (2017) found that there are three aspects affecting the delivery of transformational experiences in tourism. These include embodied and situated learning, relationship building and acknowledging and sharing power that is derived from engaging in development projects. Similarly, Massingham et al. (2019) found that engagement in environmental conservation projects and its experiential elements (e.g. education, encounters with wildlife) were generally associated with participants' emotions, learning, connections and reflective processes.

In a completely different context, dark tourism has often contributed to transformational processes through the delivery of experiences that often generate negative feelings among visitors, even when these negative emotions do not necessarily equate to negative experiences ( Linayage et al. , 2015 ). Dark tourism may in some cases result in visitors being exposed to poverty, hunger or dramatic levels of deprivation, which can have profound emotional impacts on people witnessing these circumstances.

Using generally more positive emotions, scholars have argued that adventure tourism ( Gilbert and Gillet, 2014 ) can also lead to transformative experiences through risk-taking, overcoming personal fears, self-affirmation, teamwork and tourists realising their true potential, even if some scholars would posit that for adventure tourism to deliver truly transformative experiences, it needs to involve extreme situations that take people to the very limits of their emotions ( Allman et al. , 2009 ).

Overall, considering the overall trends that appear to emerge from the transformational tourism literature over the past four decades, scholarly research in this field appears to have shifted from individual transformations among tourists to a different level of understanding of these processes through different types of experiences where interactions with other individuals are beginning to be investigated in more depth, even if the research that takes into account host–visitor relationships remains still nascent. Similarly, from a more theoretical perspective, memorable experiences linked to tourism remain another fertile path for research – see, for instance, Pung et al .'s (2020) conceptual model, particularly, in terms of their measurement (note the transformational tourism experience scale developed by Soulard et al. , 2020 ) and links to various aspects of experience design, including the “disorienting dilemma” first outlined by Mezirow's (1978 , 2000) as a factor that significantly influences the development of transformational experiences. Research by Soulard et al. (2020) , for instance, discovered that this “disorienting dilemma” tends to occur once tourists have returned home, so it is not possible to research it while they are still at their destination of choice.

Leadership is increasingly developing into an emerging research theme in transformational tourism. Scholarly research in this field ( Spicer-Escalante, 2011 ; Robledo and Batle, 2017 ) posits that tourism experiences focusing on personal development, including improved communication, bonding with others, development of self-understanding and self-awareness are elements that tend to contribute to personality traits associated with leadership.

For instance, using Hanson's (2013) leadership development interface model, Cruz (2017) showed that pilgrimage tourism experiences often contain important metaphorical aspects that influence the development of leaders. In fact, Cruz (2017) described pilgrimage as a “foundational symbol for leadership development” (p. 50) as it delivers self-awareness, self-growth and self-understanding as a result of self-reflection.

Similarly, Ross (2019) and Robledo and Batle (2017) used the metaphor of Campbell's archetypal journey adopting transformational tourism as a “hero's journey”. Research by Gilbert and Gillett (2014) echoes this metaphor in their analysis of Mary Shaffer and Barbara Kingscote as horseback adventurers and their achievements in the “frontier stage of adventure” (p. 314), which often involved overcoming fear in order to achieve their goals. The study found that through embodied experiences in adventure tourism such as excitement and thrill based on risk, they were able to de-territorialize themselves.

Responsible tourism

Responsible tourism guides a destination's development and respects its overall tourism system through a balanced focus on its culture, environment, local economy and host community ( United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), 2018 ). In line with this philosophy, responsible tourists tend to be particularly predisposed to protecting the environment and its biodiversity. In turn, for local communities, it is the conservation and development of destinations that are often the priority ( Sin, 2010 ; Woo et al. , 2015 ), particularly with the aim of improving the quality of life of residents ( Lehto et al. , 2020 ), creating an increasingly resilient local economy and capitalising on the advantages of sustainable tourism ( Uysal et al. , 2016 ). However, the longer-term sustainability of a destination relies largely on a combination of responsible visitors and entrepreneurial residents with a good sense of environmental stewardship.

On this front, Ulusoy (2016) argued that “responsible [tourism and consumption] becomes an act of hybrid, of moral, rational, social, and ludic agencies” (p. 284) where tourists partaking in alternative break trips can undergo deep transformational experiences as a result of the acquisition of a sense of empowerment and a broader sense of responsibility. The same study found that participants in transformational experiences tend to develop responsible identities through their development of an organic community, unpretentious fun, embracing the other, developing and using capabilities, overcoming challenges and self-reflection. Ulusoy’s (2015) findings underline that the development of responsible behaviours and identities leads to self-interest and the creation of deep connections with “others”. Walker and Moscardo (2016) took this further within an indigenous tourism context by arguing that responsible tourism should also involve the development of a “sense of place” and a “care of place”. Moreover, they posit that these two spheres have the potential to deliver deeply transformational processes in tourists as well as their host communities, often influenced by periods of critical self-reflection.

Sustainable development (United Nations' sustainable development goals framework)

Transformational tourism has been interpreted by some scholars as a sustainable ambassador ( Lean, 2012 ) by encouraging the empowerment of local communities as well as helping host communities and tourists to reflect on their responsibilities. In line with this, it could be argued that transformational tourism has a role to play in sustainable development.

The tourism sector has been linked to the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals framework and the tourism development report in 2018 ( United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), 2018 ) illustrated five pillars in this respect, namely, sustainable economic growth; social inclusiveness, employment, and poverty reduction; resource efficiency, environmental protection, and climate change; cultural values, diversity and heritage; and mutual understanding, peace and security. Kim et al. (2019) , for instance, illustrate the link between community-based ecotourism and sustainable transformative economies. Similarly, Butcher (2011) highlights that ecotourism has the capability to tackle poverty and address the Millennium Development Goals. Massingham et al. (2019) feature aspects of experiences such as positive and negative emotions, connections, reflections and elements of experiences (animal encounters and educational shows) associated with ecotourism that support different types of conservational engagements. Higgins and Mundine (2008) allude implicitly to aspects of social inclusiveness, poverty reduction and resource efficiency in their analysis of transformative experiences in voluntourism. However, much of this research remains embryonic in terms of its contribution to clear links between transformational tourism and the UN's framework of Sustainable Development Goals.

Discussion and research agenda

As scholarly enquiry related to transformational tourism and, indeed, transformational experiences in this industry ( Teoh et al. , 2021 ) continues to develop, it would appear that an impending sense of Quo Vadis is emerging among researchers in this field. Far from being a sign of philosophical indecisiveness, creative dithering or even – far from it – lack of thought leadership, this may be more a product of the trans-modernity phenomenon first coined by Ghisi (2001) within the context of sustainability and discussed holistically with mesmerising profoundness by Ateljevic (2009 , 2020) . Indeed, in line with Ateljevic's argument, should transformational tourism focus solely on the neurological and psychological changes taking place at the level of the individual, the search for meaning by new generations in a hyperconnected world where, paradoxically, loneliness is on the rise, or the existentialist dilemmas emerging among communities around the world as the fallout of the largest global pandemic in living memory? This section attempts to discuss these issues and potential avenues for new research in transformational tourism adopting a futures-based approach. Inevitably, perhaps, questions are raised with no easy answers, at least not within the current business and management paradigm that dominates much of tourism research today.

Firstly, the concept of what should be classed as “transformative” or “transformational” merits further investigation, particularly, given that transformational thought processes arising from self-reflection are complex and tend to take time ( Coghlan and Weiler, 2018 ), as illustrated in Figure 6 . Similarly, in order for transformation of any given magnitude to take place, is a trigger in the form of, for instance, a memorable experience a pre-requisite? Would this mean that a more ordinary, and arguably less memorable tourism experience, would be unlikely to result in transformative thought processes? Furthermore, if a tourism experience is designed to be “transformational”, how would we evaluate its success given that the time scales associated with self-reflection processes may last several years? Similarly, the output of this transformation may differ among individuals. For some, the transformation may be purely cognitive, whereas, for others, the transformation may result in physical changes and even life-changing actions such as a major career epiphany, a move to a different part of the world (or simply from an urban environment to a more rural location), dietary changes (e.g. embracing vegetarianism) or a radical lifestyle change involving some or all of the above.

Secondly, what type of tourism would be more likely to deliver the type of transformational tourism experiences sought by future generations? So far, scholarly enquiry in this field has tended to favour pilgrimage tourism, backpacker tourism, voluntourism and other forms of tourism often clustered under the general umbrella term of “special interest tourism” (see Weiler and Firth, 2021 for a research agenda for this field). Increasingly, however, slow tourism (see, among others, Caffyn, 2012 ) is likely to develop as a channel for transformational tourism experiences as the world emerges from the current global COVID-19 pandemic. However, although this type of tourism has often been associated with nature-based tourism, urban tourism destinations are likely to become strong competitors for slow tourism over time. Urban tourism destinations will not only develop their nature-based offer in the future, including mega parks (e.g. Buckley et al. , 2021 ), geology-related attractions (e.g. Richards et al. , 2021 ) and urban wildlife (e.g. Simpson et al. , 2021 ), all of which have a positive impact on the mental health of residents and visitors alike. They will increasingly seek to evolve their smart tourism offer towards a different paradigm, coined by Coca-Stefaniak (2020) as “wise tourism cities”, which focusses more on a hybrid approach combining smart technologies and digital detox to trigger neurological processes leading to elusive (and often ephemeral) states of inner peace. Although these events need not result in transformational experiences at all in the short term, the effect of these experiences on visitors and residents alike will become an avenue of scholarly enquiry at various levels, particularly given that the impending Internet of the Senses revolution is poised to widen the array of options available to tourism professionals on this front ( Agapito, 2020 ; Pasolini et al. , 2020 ).

Thirdly, the majority of articles found in this systematic literature review focused on the tourists' perspective, with only a limited number of studies investigating the host and destination perspective ( Isaac, 2017 ; Wanitchakorn and Muangasame, 2021 ). However, transformational experiences embedded in any degree of – albeit contested – authenticity tend to rely on a social context where local host communities play a pivotal role in the delivery of immersive experiences for visitors ( Lehto et al. , 2020 ; Seeler et al. , 2021 ). Meaningful tourism experiences ( McIntosh and Mansfeld, 2006 ; Mason and O'Mahony, 2007 ) sought by new generations of tourists (e.g. Chirakranont and Sakdiyakorn, 2022 ; Wilson and Harris, 2006 ) will increasingly rely on this aspect of transformational tourism, which currently remains under-researched. This search for more meaningful travel may well be one of the trigger points arising from the fallout of the global COVID-19 pandemic, as some scholars have postulated, particularly in the context of sustainable tourism ( Lew et al. , 2020 ; Galvani et al. , 2020 ).

Conclusions

Transformational tourism remains an emerging field in tourism research. This study has provided a systematic analysis of the literature on this topic in terms of its predominant research approaches, focus and perspectives, including the contribution of scholarly works from related fields such as ecotourism, voluntourism, adventure tourism and pilgrimage tourism, among others. Overall, 194 articles have been reviewed spanning a 42-year period from 1978 until 2020. Most research in transformational tourism appears to adopt a demand-led focus, with scholarly enquiry adopting a host community perspective in need of further development. Similarly, in spite of the growing links between leadership development and transformational experiences or the parallels between transformational tourism and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals framework, these two aspects of scholarly enquiry remain under-researched. Moreover, the need for a tourism system-based approach to the analysis of transformational tourism processes is argued in this study with a framework suggested for further research in this field that considers the role of time in the development of transformational tourism experiences as well as a potential continuum in this process that also involves more “standard” or “ordinary” tourism experiences as well as memorable ones. Accordingly, recommendations for further research in transformational tourism are offered adopting a tourism futures approach to elicit not only the shorter-term impacts that the on-going global COVID-19 pandemic will have on the dynamics of tourism and travel but also longer-term trends, including the growing search among new generations of tourists for meaningful experiences, where local communities play an active role.

Systematic literature search process

Systematic literature review process with selection criteria

Growth in transformational tourism publications between 1978 and 2020

Articles in transformational tourism by topic (absolute numbers for 1978–2020 period)

VOS viewer network visualisation of themes related to transformational tourism research

Conceptual framework for future research in transformational tourism

Keyword co-occurrence

Sources (peer-reviewed journals) of transformational tourism articles

Abbas , J. , Mubeen , R. , Iorember , P.T. , Raza , S. and Mamirkulova , G. ( 2021 ), “ Exploring the impact of COVID-19 on tourism: transformational potential and implications for a sustainable recovery of the travel and leisure industry ”, Current Research in Behavioral Sciences , Vol. 2 , 100033 .

Adams , A.E. ( 2013 ), “ The pilgrimage transformed: how to decompartmentalize US volunteer tourism in central America ”, in Borland , K. and Adams , A.E. (Eds), International Volunteer Tourism , Palgrave Macmillan , New York , pp. 157 - 169 .

Agapito , D. ( 2020 ), “ The senses in tourism design: a bibliometric review ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 83 , 102934 .

Alexander , Z. ( 2012 ), “ International volunteer tourism experience in South Africa: an investigation into the impact on the tourist ”, Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management , Vol. 21 No. 7 , pp. 779 - 799 .

Allman , T.L. , Mittelstaedt , R.D. , Martin , B. and Goldenberg , M. ( 2009 ), “ Exploring the motivations of BASE jumpers: extreme sport enthusiasts ”, Journal of Sport and Tourism , Vol. 14 No. 4 , pp. 229 - 247 .

Assaf , A.G. , Kock , F. and Tsionas , M. ( 2022 ), “ Tourism during and after COVID-19: an expert-informed agenda for future research ”, Journal of Travel Research , Vol. 61 No. 2 , pp. 454 - 457 .

Ateljevic , I. ( 2009 ), “ Transmodernity: remaking our (tourism) world? ”, Philosophical Issues in Tourism , Channel View Publications , London , pp. 278 - 302 .

Ateljevic , I. ( 2020 ), “ Transforming the (tourism) world for good and (re) generating the potential ‘new normal ”, Tourism Geographies , Vol. 22 No. 3 , pp. 467 - 475 .

Bond , N. , Packer , J. and Ballantyne , R. ( 2015 ), “ Exploring visitor experiences, activities and benefits at three religious tourism sites ”, International Journal of Tourism Research , Vol. 17 , pp. 471 - 481 .

Bosangit , C. , Hibbert , S. and McCabe , S. ( 2015 ), “ ‘If I was going to die I should at least be having fun’: travel blogs, meaning and tourist experience ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 55 , pp. 1 - 14 .

Bruner , M.E. ( 1991 ), “ Transformation self in tourism ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 18 , pp. 238 - 250 .

Buckley , R. , Zhong , L. and Martin , S. ( 2021 ), “ Mental health key to tourism infrastructure in China's new megapark ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 82 , 104169 .

Butcher , J. ( 2011 ), “ Can ecotourism contribute to tackling poverty? The importance of ‘symbiosis’ ”, Current Issues in Tourism , Vol. 14 No. 3 , pp. 295 - 307 .

Caffyn , A. ( 2012 ), “ Advocating and implementing slow tourism ”, Tourism Recreation Research , Vol. 37 No. 1 , pp. 77 - 80 .

Chen , G. , Bao , J. and Huang , S. ( 2014 ), “ Segmenting Chinese backpackers by travel motivations ”, International Journal of Tourism Research , Vol. 16 , pp. 355 - 367 .

Chirakranont , R. and Sakdiyakorn , M. ( 2022 ), “ Conceptualizing meaningful tourism experiences: case study of a small craft beer brewery in Thailand ”, Journal of Destination Marketing and Management , Vol. 23 , 100691 .

Coca-Stefaniak , J.A. ( 2020 ), “ Beyond smart tourism cities–towards a new generation of ‘wise’ tourism destinations ”, Journal of Tourism Futures , Vol. 7 No. 2 , pp. 251 - 258 , doi: 10.1108/JTF-11-2019-0130 .

Coghlan , A. and Gooch , M. ( 2011 ), “ Applying a transformative learning framework to volunteer tourism ”, Journal of Sustainable Tourism , Vol. 19 No. 6 , pp. 713 - 728 .

Coghlan , A. and Weiler , B. ( 2018 ), “ Examining transformative processes in volunteer tourism ”, Current Issues in Tourism , Vol. 21 No. 5 , pp. 567 - 582 .

Cruz , J. ( 2017 ), “ Pilgrimage in leadership ”, International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage , Vol. 5 No. 2 , pp. 50 - 54 .

Davis , J. , Mengersen , K. , Bennett , S. and Mazerolle , L. ( 2014 ), “ Viewing systematic reviews and meta-analysis in social research through difference lenses ”, Springer Plus , Vol. 3 No. 511 , pp. 1 - 9 .

Deville , A. and Wearing , S. ( 2013 ), “ WWWOOFing tourists: beaten tracks and transformational paths ”, in Reisinger , Y. (Ed.), Transformational Tourism: Tourist Perspectives , CABI , Oxfordshire , pp. 151 - 168 .

Dillette , A.K. , Douglas , A.C. and Andrzejewski , C. ( 2019 ), “ Yoga tourism- a catalyst for transformation? ”, Annals of Leisure Research , Vol. 22 No. 1 , pp. 22 - 41 .

Galvani , A. , Lew , A.A. and Perez , M.S. ( 2020 ), “ COVID-19 is expanding global consciousness and the sustainability of travel and tourism ”, Tourism Geographies , Vol. 22 No. 3 , pp. 567 - 576 .

Ghisi , M.L. ( 2001 ), Au-delà de la modernité, du patriarcat et du capitalisme , L'Harmattan , Paris .

Gilbert , M. and Gillett , J. ( 2014 ), “ Into the mountains and across the country: emergent forms of equine adventure leisure in Canada ”, Society and Leisure , Vol. 37 No. 2 , pp. 313 - 325 .

Guttentag , D. ( 2019 ), “ Transformative experiences via Airbnb: is it the guests or the host communities that will be transformed? ”, Journal of Tourism Futures , Vol. 5 No. 2 , pp. 179 - 184 .

Hanson , B. ( 2013 ), “ The leadership development interface: aligning leaders and organizations toward more effective leadership learning ”, Advances in Developing Human Resources , Vol. 15 No. 1 , pp. 106 - 120 .

Higgins , D.F. and Mundine , R.G. ( 2008 ), “ Absences in the volunteer tourism phenomenon: the right to travel, solidarity tours and transformation beyond the one-way ”, in Lyon , K. and Wearing , S. (Eds), Journeys of Discovery in Volunteer Tourism , CABI , Cambridge , pp. 182 - 194 .

Hobson , P. and Welbourne , L. ( 1998 ), “ Adult development and transformative learning ”, International Journal of Lifelong Education , Vol. 17 No. 2 , pp. 72 - 86 .

Isaac , R.K. ( 2017 ), “ Transformational host communities: justice tourism and the water regime in Palestine ”, Tourism Culture and Communication, Cognizant Communication Corporation , Vol. 17 No. 2 , pp. 139 - 158 .

Jernsand , E.M. ( 2017 ), “ Engagement as transformation: learnings from a tourism development project in Dunga by Lake Victoria, Kenya ”, Action Research , Vol. 15 No. 1 , pp. 81 - 99 .

Kim , M. , Xie , Y. and Cirella , G.T. ( 2019 ), “ Sustainable transformative economy: community-based ecotourism ”, Sustainability , Vol. 11 No. 4977 , pp. 1 - 15 .

Kirillova , K. ( 2017 ), “ What triggers transformative tourism experiences? ”, Tourism Recreation Research , Vol. 42 No. 4 , pp. 498 - 511 .

Knollenberg , W. , McGehee , N.G. , Boley , B.B. and Clemmons , D. ( 2014 ), “ Motivation-based transformative learning and potential volunteer tourists: facilitating more sustainable outcomes ”, Journal of Sustainable Tourism , Vol. 22 No. 6 , pp. 922 - 941 .

Knowles , R. ( 2013 ), “ Regency history ”, available at: https://www.regencyhistory.net/2013/04/the-grand-tour.html ( accessed 17th October 2020 ).

Korstanje , M.E. and George , B. ( 2022 ), The Nature and Future of Tourism: A Post-COVID-19 Context , CRC Press , London .

Kottler , J.A. ( 1998 ), “ Transformative travel ”, The Futurist , Vol. 32 No. 3 , pp. 24 - 19 .

Kurmanaliyeva , Rysbekovab , Sh. , Duissenbayevac , A. and Izmailov , I. ( 2014 ), “ Religious tourism as a sociocultural phenomenon of the present ‘The unique sense today is a universal value tomorrow. This is the way religions are created and values are made’ ”, Social and Behavioural Sciences , Vol. 143 , pp. 958 - 963 .

Lean , G. ( 2012 ), “ Transformative travel: a mobilities perspective ”, Tourist Studies , Vol. 12 No. 2 , pp. 151 - 172 .

Lee , Y.J. and Woosnam , K.M. ( 2010 ), “ Voluntourist transformation and the theory of integrative cross-cultural adaption ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 37 No. 4 , pp. 1186 - 1189 .

Lehto , X. , Davari , D. and Park , S. ( 2020 ), “ Transforming the guest–host relationship: a convivial tourism approach ”, International Journal of Tourism Cities , Vol. 6 No. 4 , pp. 1069 - 1088 .

Lew , A.A. , Cheer , J.M. , Haywood , M. , Brouder , P. and Salazar , N.B. ( 2020 ), “ Visions of travel and tourism after the global COVID-19 transformation of 2020 ”, Tourism Geographies , Vol. 22 No. 3 , pp. 455 - 466 .

Liyanage , S. , Coca-Stefaniak , J.A. and Powell , R. ( 2015 ), “ Dark destinations-visitor reflections from a holocaust memorial site ”, International Journal of Tourism Cities , Vol. 1 No. 4 , pp. 282 - 298 .

Lochrie , S. , Baxter , W.F.I. , Collinson , E. , Curran , R. , Gannon , M.J. and Taheri , B. ( 2019 ), “ Self-expression and play: can religious tourism be hedonistic? ”, Tourism Recreation Research , Vol. 44 No. 1 , pp. 2 - 16 .

Marschall , S. ( 2008 ), “ Zulu heritage between institutionalized commemoration and tourist attraction ”, Visual Anthropology , Vol. 21 No. 3 , pp. 245 - 265 .

Mason , R. and O'Mahony , B. ( 2007 ), “ On the trail of food and wine: the tourist search for meaningful experience ”, Annals of Leisure Research , Vol. 10 Nos 3-4 , pp. 498 - 517 .

Massingham , E. , Fuller , R.A. and Dean , A.J. ( 2019 ), “ Pathways between contrasting ecotourism experiences and conservation engagement ”, Biodiversity and Conservation , Vol. 28 , pp. 827 - 845 .

McIntosh , A. and Mansfeld , Y. ( 2006 ), “ Spirituality and meaningful experiences in tourism ”, Tourism (Zagreb) , Vol. 54 No. 2 , pp. 95 - 185 .

Mezirow , J. ( 1978 ), “ Perspective transformation ”, Adult Education , Vol. 28 No. 2 , pp. 100 - 110 .

Mezirow , J. ( 1991 ), Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning , Jossey-Bass (publ.) , San Francisco .

Mezirow , J. ( 2000 ), Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress , Jossey-Bass , San Francisco .

Moher , D. , Liberati , A. , Tetzlaff , J. and Altman , D.G. ( 2009 ), “ Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement ”, PLoS Medicine , Vol. 6 No. 7 , pp. 1 - 6 .

Muller , C.V. , Scheffer , A.B.B. and Closs , L.Q. ( 2020 ), “ Volunteer tourism, transformative learning and its impacts on careers: the case of Brazilian volunteers ”, International Journal Tourism , Vol. 22 , pp. 726 - 738 .

Nikjoo , A. , Razavizadeh , N. and Giovine , M.A.D. ( 2020 ), “ What draws Shia Muslims to an insecure pilgrimage? The Iranian journey to Arbaeen, Iraq during the presence of ISIS ”, Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change , Vol. 19 No. 4 , pp. 1 - 22 .

O'Reilly , C. ( 2006 ), “ From drifter to gap year tourist mainstreaming backpacker travel ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 33 No. 4 , pp. 998 - 1017 .

Pasolini , G. , Guerra , A. , Guidi , F. , Decarli , N. and Dardari , D. ( 2020 ), “ Crowd-based cognitive perception of the physical world: towards the Internet of Senses ”, Sensors , Vol. 20 No. 9 , p. 2437 .

Pasquinelli , C. , Trunfio , M. , Bellini , N. and Rossi , S. ( 2022 ), “ Reimagining urban destinations: adaptive and transformative city brand attributes and values in the pandemic crisis ”, Cities , Vol. 124 , 103621 .

Pookhao , N. ( 2014 ), “ Community-based eco-tourism: the transformation of local community ”, SHS Web of Conferences , Vol. 12 , pp. 1 - 8 .

Pung , J.M. , Gnoth , J. and Chiappa , G.D. ( 2020 ), “ Tourist transformation: towards a conceptual model ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 81 , pp. 1 - 12 .

Reisinger , Y. ( 2013 ), Transformational Tourism: Tourist Perspectives , CABI , Oxfordshire .

Reisinger , Y. ( 2015 ), Transformational Tourism: Host Perspectives , CABI , Oxfordshire .

Richards , S. , Simpson , G. and Newsome , D. ( 2021 ), “ Appreciating geology in the urban environment ”, in Morrison , A.M. and Coca-Stefaniak , J.A. (Eds), Routledge Handbook of Tourism Cities , Routledge , London , pp. 520 - 539 .

Robledo , M. and Batle , J. ( 2017 ), “ Transformational tourism as a hero's journey ”, Current Issues in Tourism , Vol. 20 No. 16 , pp. 1736 - 1748 .

Ross , S. ( 2010 ), “ Transformative travel: an enjoyable way to foster radical change ”, ReVision , Vol. 32 No. 1 , pp. 54 - 61 .

Ross , S. ( 2019 ), “ The making of everyday heroes: women's experiences with transformation and integration ”, Journal of Humanistic Psychology , Vol. 59 No. 4 , pp. 499 - 521 .

Seeler , S. , Lück , M. and Schänzel , H. ( 2021 ), “ Paradoxes and actualities of off-the-beaten-track tourists ”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management , pp. 1 - 9 , doi: 10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.06.004 .

Sharma , N. and Rickly , J. ( 2019 ), “ ‘The smell of death and the smell of life’: authenticity, anxiety and perceptions of death at Varanasi's cremation grounds ”, Journal of Heritage Tourism , Vol. 14 Nos 5-6 , pp. 466 - 477 .

Simpson , G. , Patroni , J. , Kerr , D. , Verduin , J. and Newsome , D. ( 2021 ), “ Dolphins in the city ”, in Morrison , A.M. and Coca-Stefaniak , J.A. (Eds), Routledge Handbook of Tourism Cities , Routledge , London , pp. 540 - 550 .

Sin , H.L. ( 2010 ), “ Volunteer tourism — ‘involve me and I will learn’ ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 36 No. 3 , pp. 480 - 501 .

Škare , M. , Soriano , D.R. and Porada-Rochoń , M. ( 2021 ), “ Impact of COVID-19 on the travel and tourism industry ”, Technological Forecasting and Social Change , Vol. 163 , 120469 .

Soulard , J. , McGhee , N.G. and Stern , M. ( 2019 ), “ Transformative tourism organizations and glocalization ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 76 , pp. 91 - 104 .

Soulard , J. , McGehee , N. and Knollenberg , W. ( 2020 ), “ Developing and testing the transformative travel experience scale (TTES) ”, Journal of Travel Research , pp. 1 - 24 .

Spicer-Escalante , J.P. ( 2011 ), “ Ernesto Che Guevara, Reminiscences of the Cuban revolutionary war, and the politics of guerrilla travel writing ”, Studies in Travel Writing , Vol. 15 No. 4 , pp. 393 - 405 .

Sterchele , D. ( 2020 ), “ Memorable tourism experiences and their consequences: an interaction ritual (IR) theory approach ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 81 , pp. 311 - 322 .

Stone , A.G. and Duffy , N.L. ( 2015 ), “ Transforming Learning Theory: a systematic review of travel and tourism scholarship ”, Journal of Teaching in Travel and Tourism , Vol. 15 No. 3 , pp. 204 - 224 .

Teoh , M.W. , Wang , Y. and Kwek , A. ( 2021 ), “ Conceptualising co-created transformative tourism experiences: a systematic narrative review ”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management , Vol. 47 , pp. 176 - 189 .

Thal , K.I. and Hudson , S. ( 2019 ), “ A conceptual model of wellness destination characteristics that contribute to psychological well-being ”, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research , Vol. 43 No. 1 , pp. 41 - 57 .

Ulusoy , E. ( 2016 ), “ Experiential responsible consumption ”, Journal of Business Research , Vol. 69 , pp. 284 - 297 .

United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) . ( 2018 ), Tourism for Development – Volume I: Key Areas for Action , UNWTO , Madrid , doi: 10.18111/9789284419722 (accessed 20 March 2021) .

Uysal , M. , Sirgy , M.J. , Woo , E. and Kim , H. ( 2016 ), “ Quality of life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 53 , pp. 244 - 261 .

Voigt , C. , Brown , G. and Howat , G. ( 2011 ), “ Wellness tourists: in search of transformation ”, Tourism Review , Vol. 66 No. 1/2 , pp. 16 - 30 .

Walker , K. and Moscardo , G. ( 2016 ), “ Moving beyond sense of place to care of place: the role of Indigenous values and interpretation in promoting transformative change in tourists place images and personal values ”, Journal of Sustainable Tourism , Vol. 24 Nos 8-9 , pp. 1243 - 1261 .

Walter , P.G. ( 2016 ), “ Catalysts for transformative learning in community-based ecotourism ”, Current Issues in Tourism , Vol. 19 No. 13 , pp. 1356 - 1371 .

Wanitchakorn , T. and Muangasame , K. ( 2021 ), “ The identity change of rural–urban transformational tourism development in Chiang Mai heritage city: local residents’ perspectives ”, International Journal of Tourism Cities , Vol. 7 No. 4 , pp. 1008 - 1028 .

Weiler , B. and Firth , T. ( 2021 ), “ Special interest travel: reflections, rejections and reassertions ”, Consumer Tribes in Tourism , Springer , Singapore , pp. 11 - 25 .

Wengel , Y. , McIntosh , A. and Cockburn-Wootten , C. ( 2019 ), “ Co-creating knowledge in tourism research using the Ketso method ”, Tourism Recreation Research , Vol. 44 No. 3 , pp. 311 - 322 .

Wilson , E. and Harris , C. ( 2006 ), “ Meaningful travel: women, independent travel and the search for self and meaning ”, Tourism: An International Interdisciplinary Journal , Vol. 54 No. 2 , pp. 161 - 172 .

Wolf , I.D. , Ainsworth , G.B. and Crowley , J. ( 2017 ), “ Transformative travel as a sustainable market niche for protected areas: a new development, marketing and conservation model ”, Journal of Sustainable Tourism , Vol. 25 No. 11 , pp. 1650 - 1673 .

Woo , E. , Kim , H. and Uysal , M. ( 2015 ), “ Life satisfaction and support for tourism development ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 50 , pp. 84 - 97 .

Yamamura , T. , Zhang , T. and Fujiki , Y. ( 2006 ), “ The social and cultural impact of tourism development on world heritage sites: a case of the Old Town of Lijiang, China, 2000-2004 ”, WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment , Vol. 97 , pp. 117 - 127 .

Yang , E.C.L. , Khoo-Lattimore , C. and Arcodia , C. ( 2018 ), “ Power and empowerment: how Asian solo female travellers perceive and negotiate risks ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 68 , pp. 32 - 45 .

Zavilz , K.J. and Butz , D. ( 2011 ), “ Not that alternative: short-term volunteer tourism at an organic farming project in Costa Rica ”, An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies , Vol. 10 No. 3 , pp. 412 - 441 .

Zheng , C. , Zhang , J. , Qiu , M. , Guo , Y. and Zhang , H. ( 2020 ), “ From mixed emotional experience to spiritual meaning: learning in dark tourism places ”, Tourism Geographies , Vol. 22 No. 1 , pp. 105 - 126 .

Further reading

Folmer , A. , Tengxiage , A. , Kadijk , H. and Wright , A.J. ( 2019 ), “ Exploring Chinese millennials' experiential and transformative travel: a case study of mountain bikers in Tibet ”, Journal of Tourism Future , Vol. 5 No. 2 , pp. 142 - 156 .

Noy , C. ( 2004 ), “ This trip really changed me: backpackers' narratives of self-change ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 31 No. 1 , pp. 78 - 102 .

Sheldon , P.J. ( 2020 ), “ Designing tourism experiences for inner transformation ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 83 , pp. 1 - 12 .

The National Gallery ( 2020 ), “ The Grand Tour ”, available at: https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/learn-about-art/paintings-in-depth/the-grand-tour?viewPage=4 ( accessed 17 October 2020 ).

Watson , J. ( 1989 ), “ Transformative thinking and a caring curriculum ”, in Bevis , E.O. and Watson , J. (Eds), Towards a Caring Curriculum: A New Pedagogy for Nursing , New York , pp. 51 - 60 .

Wearing , S. and McGehee , G. ( 2013 ), “ Volunteer tourism: a review ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 38 , pp. 120 - 130 .

World Tourism Organization ( 2018 ), UNWTO Annual Report 2017 , UNWTO , Madrid , doi: 10.18111/9789284419807 (accessed 20 March 2021) .

Corresponding author

Related articles, we’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Advertisement

Impact of tourism development upon environmental sustainability: a suggested framework for sustainable ecotourism

- Research Article

- Published: 19 August 2022

- Volume 30 , pages 5917–5930, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Qadar Bakhsh Baloch 1 ,

- Syed Naseeb Shah 1 ,

- Nadeem Iqbal 2 ,

- Muhammad Sheeraz 3 ,

- Muhammad Asadullah 4 ,

- Sourath Mahar 5 &

- Asia Umar Khan 6

49k Accesses

78 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

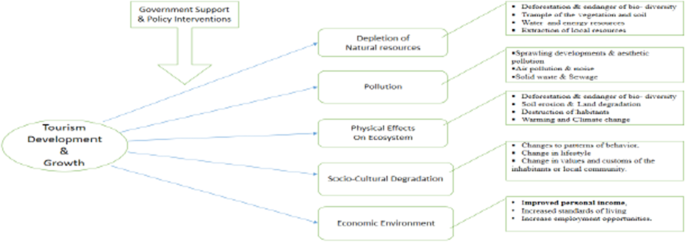

The empirical research investigated the relationship between tourism development and environmental suitability to propose a framework for sustainable ecotourism. The framework suggested a balance between business and environmental interests in maintaining an ecological system with the moderating help of government support and policy interventions. The study population encompasses tourism stakeholders, including tourists, representatives from local communities, members of civil administration, hoteliers, and tour operators serving the areas. A total of 650 questionnaires were distributed to respondents, along with a brief description of key study variables to develop a better understanding. After verifying the instrument’s reliability and validity, data analysis was conducted via hierarchical regression. The study findings revealed that a substantial number of people perceive socio-economic benefits, including employment and business openings, infrastructure development from tourism development, and growth. However, the state of the natural and environmental capital was found to be gradually degrading. Alongside the social environment, social vulnerability is reported due to the overutilization of land, intrusion from external cultures, and pollution in air and water due to traffic congestion, accumulation of solid waste, sewage, and carbon emissions. The study suggested a model framework for the development of sustained ecotourism, including supportive government policy interventions to ensure effective conservation of environmental and natural resources without compromising the economic viability and social well-beings of the locals. Furthermore, the variables and the constructs researched can be replicated to other destinations to seek valuable inputs for sustainable destination management elsewhere.

Similar content being viewed by others

Three pillars of sustainability: in search of conceptual origins

Ben Purvis, Yong Mao & Darren Robinson

Ecotourism and sustainable development: a scientometric review of global research trends

Lishan Xu, Changlin Ao, … Zhenyu Cai

Smart tourism: foundations and developments

Ulrike Gretzel, Marianna Sigala, … Chulmo Koo

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Tourism is a vibrant force that stimulates travel to explore nature, adventures, wonders, and societies, discover cultures, meet people, interact with values, and experience new traditions and events. Tourism development attracts tourists to a particular destination to develop and sustain a tourism industry. Moreover, environmental sustainability is the future-based conscious effort aimed at conserving socio-cultural heritage and preserving natural resources to protect environmental ecosystems through supporting people’s health and economic well-being. Environment sustainability can be reflected in clean and green natural landscaping, thriving biodiversity, virgin sea beaches, long stretches of desert steppes, socio-cultural values, and archeological heritage that epitomize tourists’ degree of motivation and willingness of the local community to welcome the visitors. In this context, tourism growth and environmental sustainability are considered interdependent constructs; therefore, the increase in tourism development and tourists’ arrivals directly affects the quality of sustained and green tourism (Azam et al. 2018 ; Hassan et al. 2020 ; Sun et al. 2021 ).

According to the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), tourism is one of the fastest-growing industries, contributing more than 10% to the global GDP (UNWTO 2017; Mikayilov et al. 2019 ). Twenty-five million international tourists in 1950 grew to 166 million in 1970, reaching 1.442 billion in 2018 and projected to be 1.8 billion by 2030. Mobilizing such a substantial human tourist’s mass is most likely to trickle environmental pollution along with its positive effects on employment, wealth creation, and the economy. The local pollution at tourist destinations may include air emissions, noise, solid waste, littering, sewage, oil and chemicals, architectural/visual pollution, heating, car use, and many more. In addition, an uncontrolled, overcrowded, and ill-planned tourist population has substantial adverse effects on the quality of the environment. It results in the over-consumption of natural resources, degradation of service quality, and an exponential increase in wastage and pollution. Furthermore, tourism arrivals beyond capacity bring problems rather than a blessing, such as leaving behind soil erosion, attrition of natural resources, accumulation of waste and air pollution, and endangering biodiversity, decomposition of socio-cultural habitats, and virginity of land and sea (Kostić et al. 2016 ; Shaheen et al. 2019 ; Andlib and Salcedo-Castro 2021 ).

Tourism growth and environmental pollution have been witnessed around the globe in different regions. The ASEAN countries referred to as heaven for air pollution, climate change, and global warming are experiencing economic tourism and pollution (Azam et al. 2018 ; Guzel and Okumus 2020 ). In China, more than fifty-eight major Chinese tourism destinations are inviting immediate policy measures to mitigate air pollution and improve environmental sustainability (Zhang et al. 2020 ). Similarly, Singapore, being a top-visited country, is facing negative ecological footprints and calling for a trade-off between tourism development and environmental sustainability (Khoi et al. 2021 ). The prior studies established that international tourism and the tourism-led growth surge tourists’ arrival, energy consumption, carbon dioxide (CO 2 ) emissions, and air pollution resultantly cause climate change (Aslan et al. 2021 ). South Asian countries, more specifically Sri Lanka and Pakistan, are on the verge of tourism growth and environmental pollution compared to other countries (Chishti et al. 2020 ; Tiwari et al. 2021 ).

Pakistan is acknowledged in the tourism world because of its magnificent mountains with the densest concentration of high peaks in the world, scenic beauty of Neelum Valley, Murree, Chitral, and swat Valleys’, Kaghan, Naran, Hunza, Gilgit Baltistan (Baloch 2007 ), sacred shrines of Sikhism, archeological sites of the Gandhara and Indus Valley civilizations such as Mohenjo-Daro, Taxila including pre-Islamic Kalasha community (Baloch and Rehman 2015 ). In addition, Pakistan’s hospitable and multicultural society offers rich traditions, customs, and festivals for the tourists to explore, commemorate, cherish, and enjoy. Pakistan’s geographical and socio-cultural environment represents its resource and an opportunity (Baloch and Rehman 2015 ); therefore, Pakistan is looking to capitalize on it as a promising source of the foreign reserve to compensate for its mounting trade deficit (Baloch et al. 2020 ).

Tourism expansion has been established as a very deleterious ecological cost vis-à-vis the socio-economic benefits it passes to the host communities (Pulido-Fernández et al. 2019 ; Simo-Kengne 2022 ). In this context, the research is motivated to investigate the relationships between Pakistan’s tourism development activities and environmental sustainability. Drawing from the arguments of Pulido-Fernández et al. ( 2019 ) and Simo-Kengne ( 2022 ), it is feared that Pakistan’s ongoing determination to tourism development is likely to cause environmental degradation in two ways. Firstly, the tourism infrastructure developmental process would consume natural resources in the form of air and water pollution, loss of nature, and biodiversity. Secondly, the proliferation of tourism-related energy-consuming activities harms the environment by adding CO 2 emissions (Andlib and Saceldo-Castro 2021 ; Chien et al. 2021a ). Therefore, to tape this tourism-rich potential without compromising the sustainability of the natural and socio-cultural environment in the area, there is a dire need to develop Pakistan’s tourism areas into environment-friendly destinations.

Against the backdrop of a widening level of trade deficit, Pakistan’s rich tourism potential is being perceived as an immediate alternative for earning revenue to compensate for the current account gap. However, the developing large-scale tourism industry is considered a threat to deforestation, and air and water pollution, endangering biodiversity trading on resilient ecological credentials. The research study attempts to find an all-inclusive and comprehensive answer to the socio-ecological environmental concerns of tourism development and growth. Therefore, the research investigates the relationship between tourism development and its environmental sustainability to suggest a model framework for the development and growth of Sustainable Ecotourism in Pakistan along with its most visited destinations.

Literature review

- Tourism development and growth

Tourism is considered a force of sound as it benefits travelers and communities in urban and suburban areas. Tourism development is the process of forming and sustaining a business for a particular or mix of segments of tourists’ as per their motivation in a particular area or at a specific destination. Primarily, tourism development refers to the all-encompassing process of planning, pursuing, and executing strategies to establish, develop, promote, and encourage tourism in a particular area or destination (Mandić et al. 2018 ; Ratnasari et al. 2020 ). A tourism destination may serve as a single motivation for a group of tourists or a mix of purposes, i.e., natural tourism, socio-cultural or religious tourism, adventure or business tourism, or a combination of two or more. Andlib and Salcedo-Castro ( 2021 ), drawing from an analysis approach, contended that tourism destinations in Pakistan offer a mix of promising and negative consequences concerning their socio-economic and environmental impressions on the host community. The promising socio-economic impacts for the local community are perceived in the form of employment and business opportunities, improved standard of living, and infrastructural development in the area. The adverse environmental outcomes include overcrowding, traffic congestion, air and noise pollution, environmental degradation, and encroachment of landscaping for the local community and the tourists. An extensive review of the literature exercise suggests the following benefits that the local community and the tourists accrue from the tour are as follows:

Generate revenue and monetary support for people and the community through local arts and culture commercialization.

Improve local resource infrastructure and quality of life, including employment generation and access to improved civic facilities.

Help to create awareness and understanding of different ethnic cultures, social values, and traditions, connecting them and preserving cultures.

Rehabilitate and conserve socio-cultural and historical heritage, including archeological and natural sites.

Establishment of natural parks, protracted areas, and scenic beauty spots.

Conservation of nature, biodiversity, and endangered species with control over animal poaching.

Improved water and air quality through afforestation, littering control, land and soil conservation, and recycling of used water and waste.

Tourism and hospitality business incorporates various business activities such as travel and transportation through the air or other modes of travel, lodging, messing, restaurants, and tourism destinations (Szpilko 2017 ; Bakhriddinovna and Qizi 2020 ). A tourist’s tourism experience is aimed at leisure, experiencing adventure, learning the culture or history of a particular area or ethnic entity, traveling for business or health, education, or religious purposes. The chain of activities adds value to the Tourism experience. Every activity contributes toward economic stimulation, job creation, revenue generation, and tourism development encompassing infrastructure for all activities involved in the tourism process. Tourism growth expresses the number of arrivals and the time of their stay/trips over a period of time. Tourism growth is measured through the interplay between tourists’ arrivals, tourism receipts, and travel time duration (Song et al. 2010 ; Arifin et al. 2019 ). The following factors drive the degree and level of tourism development and growth:

Environmental factors include scenic beauty, green spaces, snowy mountains, towering peaks, good climate and weather, the interconnectivity of destination, quality of infrastructure, etc.

Socio-economic factors: the distinctiveness of community, uniqueness of culture and social values, hospitality and adaptability, accessibility, accommodation, facilities and amenities, cost-effectiveness, price index, and enabling business environment.

Historical, cultural, and religious factors include historical and cultural heritage, religious sites, and cultural values and experiences.

The tourism development process and its different dynamics revolve around the nature of tourism planned for a particular destination or area, which can be specified as ecotourism, sustainable tourism, green tourism or regenerative tourism, etc. Ecotourism is “responsible travel to natural areas that conserves the environment, sustains the well-being of the local people, and involves interpretation and education” (Cheia, 2013 ; TIES, 2015). According to the World Conservation Union (IUCN), ecotourism involves “ Environmentally responsible travel to natural areas, to enjoy and appreciate nature (and accompanying cultural features, both past, and present) that promote conservation, have a low visitor impact and provide for beneficially active socio-economic involvement of local peoples ”. Moreover, Blangy and Wood ( 1993 ) defined it as “ responsible travel to natural areas that conserves the environment and sustains the well-being of local people ” (p. 32). The concept of ecotourism is grounded upon a well-defined set of principles including “environmental conservation and education, cultural preservation and experience, and economic benefits” (Cobbinah 2015 ; De Grosbois and Fennell 2021 ).

Ecotourism minimizes tourism’s impact on the tourism resources of a specific destination, including lessening physical, social, interactive, and psychosomatic impacts. Ecotourism is also about demonstrating a positive and responsible attitude from the tourists and hosts toward protecting and preserving all components of the environmental ecosystem. Ecotourism reflects a purpose-oriented mindset, responsible for creating and delivering value for the destination with a high degree of kindliness for local environmental, political, or social issues. Ecotourism generally differs from mass tourism because of its following features (Liang et al. 2018 ; Ding and Cao 2019 ; Confente and Scarpi 2021 ):

Conscientious behavior focuses on the low impact on the environment.

Sensitivity and warmth for local cultures, values, and biodiversity.

Supporting the sustenance of efforts for the conservation of local resources.

Sharing and delivering tourism benefits to the local communities.

Local participation as a tourism stakeholder in the decision-making process.

Educating the tourist and locals about the sensitivity and care of the environment because tourism without proper arrangement can endanger the ecosystems and indigenous cultures and lead to significant ecological degradation.

Sustainability aims to recognize all impacts of tourism, minimize the adverse impacts, and maximize the encouraging ones. Sustainable tourism involves sustainable practices to maintain viable support for the ecology of the tourism environment in and around the destination. Sustainable tourism is natural resource-based tourism that resembles ecotourism and focuses on creating travel openings with marginal impact and encouraging learning about nature having a low impact, conservation, and valuable consideration for the local community’s well-being (Fennell 2001 & 2020 ; Butowski 2021 ). On the other hand, ecotourism inspires tourists to learn and care about the environment and effectively participate in the conservation of nature and cultural activities. Therefore, ecotourism is inclusive of sustainable tourism, whereas the focus of sustainable tourism includes the following responsibilities:

Caring, protecting, and conserving the environment, natural capital, biodiversity, and wildlife.

Delivering socio-economic welfare for the people living in and around tourists' destinations.

Identifying, rehabilitating, conserving, and promoting cultural and historical heritage for visitors learning experiences.

Bringing tourists and local groups together for shared benefits.

Creating wide-ranging and reachable opportunities for tourists.

Environment and sustainability of ecosystem

The term “environment” is all-inclusive of all the natural, organic living, inorganic, and non-natural things. The environment also denotes the interface among all breathing species with the natural resources and other constituents of the environment. Humans’ activities are mainly responsible for environmental damage as people and nations have contemplated modifying the environment to suit their expediencies. Deforestation, overpopulation, exhaustion of natural capital, and accumulation of solid waste and sewage are the major human activities that result in polluted air and water, acid rain, amplified carbon dioxide levels, depletion of the ozone, climate change, global warming, extermination of species, etc. A clean, green, and hygienic fit environment has clean air, clean water, clean energy, and moderate temperature for the healthy living of humans, animals, and biodiversity as nature is destined for them by their creatures. Maintaining and sustaining a clean environment is indispensable for human and biodiversity existence, fostering growth and development for conducting business and creating wealth. The environment can be sustained through conservation, preservation, and appropriate management to provide clean air, water, and food safe from toxic contamination, waste, and sewage disposal, saving endangered species and land conservation.

The globalization process, known for building socio-economic partnerships across countries, is also charged with encouraging environmental degradation through the over-consumption of natural resources and energy consumption, deforestation, land erosion, and weakening (Adebayo and Kirikkaleli 2021 ; Sun et al. 2021 ). Chien et al. ( 2021b ), while studying the causality of environmental degradation in Pakistan, empirically confirmed the existence of a significant connection between CO 2 emissions and GDP growth, renewable energy, technological innovation, and globalization. However, Chien et al. ( 2021a ) suggested using solar energy as a source of economic intervention to control CO 2 emissions and improve environmental quality in China. The danger of air pollution is hard to escape as microscopic air pollutants pierce through the human respiratory and cardiovascular system, injuring the lungs, heart, and brain. Ill-planned and uncontrolled human activities negatively affect ecosystems, causing climate change, ocean acidification, melting glaciers, habitation loss, eutrophication, air pollution, contaminants, and extinction of endangered species ( Albrich et al. 2020 ) .

Humans have a more significant effect on their physical environment in numerous ways, such as pollution, contamination, overpopulation, deforestation, burning fossil fuels and driving to soil erosion, polluting air and water quality, climate change, etc. UNO Agenda for 2030 “Sustainable Development and its Sustainable Development Goals” (SDGs) mirrors the common premise that a healthy environment and human health are interlaced as integral to the satisfaction of fundamental human rights, i.e., right to life, well-being, food, water and sanitation, quality of life and biodiversity to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages (SDG3)—which includes air quality that is dependent upon terrestrial ecosystems (SDG15), oceans (SDG14), cities (SDG11), water, cleanliness, and hygiene (SDG6) (Swain 2018 ; Opoku 2019 ; Scharlemann et al. 2020 ). The UNEP stated that 58% of diarrhea cases in developing economies is due to the non-provision of clean water and inadequate sanitation facilities resulting in 3.5 million deaths globally (Desai 2016 ; Ekins and Gupta 2019 ).

Climate change overwhelmingly alters ecosystems’ ability to moderate life-threatening happenings, such as maintaining water quality, regulating water flows, unbalancing the temporal weather and maintaining glaciers, displacing or extinction biodiversity, wildfire, and drought (Zhu et al. 2019 ; Marengo et al. 2021 ). Research studies advocate that exposure to natural environments is correlated with mental health, and proximity to green space is associated with lowering stress and minimizing depression and anxiety (Noordzij et al. 2020 ; Slater et al. 2020 ; Callaghan et al. 2021 ). Furthermore, the Ecosystem is affected by pollution, over-exploitation of natural resources, climate change, invasive and displacing species, etc. Hence, providing clean air and water, hygienic places, and green spaces enriches the quality of life: condensed mortality, healthier value-added productivity, and is vital to maintaining mental health. On the other hand, climate change aggravates environment-related health hazards through adverse deviations to terrestrial ecology, oceans, biodiversity, and access to fresh and clean water.

Tourism development denotes all activities linked with creating and processing facilities providing services for the tourists on and around a destination. Infrastructure development is vital for developing a tourism destination to advance tourists’ living conditions and preserve natural and cultural heritage by constructing new tourist facilities, the destinations administrative and supporting echelons, including community living, etc. Development for tourism infrastructure and land use often burdens natural capital through over-consumption, leading to soil erosion, augmented pollution, loss of natural habitats, and endangered species. Development of tourism infrastructure and construction work has profound implications on environmental degradation, reduction in green spaces, deforestation, solid waste and sewage, overutilization of air and water, emission of CO 2 and other gases contributing to air and water pollution, climate change, loss and displacement of biodiversity, and the degradation of ecosystems. These negative consequences of tourism development result in many problems for the tourists and the indigenous people in the foreseeable future (Azam et al. 2018 ; Hoang et al. 2020 ).

A report published by UNEP titled “Infrastructure for climate action” has suggested governments introduce sustainable infrastructure as the prevailing one is responsible for causing 79% of all greenhouse gas emissions in struggling climate change, alleviation, and adaptation efforts. Sustainable infrastructure signifies that structures’ planning, construction, and functioning do not weaken the social, economic, and ecological systems (UNEP 2021 ; Krampe 2021 ). Sustainable infrastructure is the only solution that ensures societies, nature, and the environment flourish together. Therefore, Sustainable Ecotourism supports adapting pro-environment and nature-based climate change strategies that help resilient biodiversity and ecosystem to impact climate change. The proposed strategy is to focus on the conservation and restoration of ecosystems to combat climate hazards, fluctuating rainfalls, soil erosion, temperature variations, floods, and extreme wind storms (Niedziółka 2014 ; Setini 2021 )

Pakistan’s tourism infrastructure suffered a colossal amount of damage during the earthquake of October 8, 2005, which left widespread demolition and destruction to its human, economic assets, and infrastructure networks, especially in Kashmir and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa's tourism areas. The tourism-related infrastructure, including hotels, destination facilities of social service delivery and commerce, water channels, and communications networks, were either drained or virtually destroyed. The destruction in the aftermath of the earthquake was further added by the war against terror in tourism-hit areas, resulting in the redundancy of tourists and tourism facilities for a long time (Akbar et al. 2017 ; Zakaria and Ahmed 2019 ). The tourism revival activities during the post-earth quack, post-terrorism scenario, and COVID-19 period called for various entrepreneurial activities, including the construction of infrastructure, hotels, road networks, community living, etc. Development and reconstruction of the livelihood and hospitality infrastructure through entrepreneurship were undertaken intensively through a public-private partnership from national and international findings (Qamar and Baloch 2017 ; Sadiq 2021 ; Dogar et al. 2021 ).

The revival and reinvigoration of infrastructure in tourism areas were backed up by extensive deforestation, use of local green land, rebuilding of the road network, displacement of biodiversity, and overtaxing the consumption of water and other natural resources. The deforestation, extensive use of green land, and over-consumption of water and other natural resources have depleted the tourism value of the area on the one hand and degraded the environment on the other. However, it was the focused rehabilitation activities of earthquake and Pakistan’s Government’s socio-environment conservation strategy of the Billion Trees plantation program in the province, including dominating tourism areas. The afforestation and loss of green tops are being reclaimed through these efforts, and the tourism environment is soon expected to regenerate (Qamar and Baloch 2017 ; Rauf et al. 2019 ; Siddiqui and Siddiqui 2019 ).

Government support and policy interventions