- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Did Yellow Journalism Fuel the Outbreak of the Spanish American War?

By: Lesley Kennedy

Updated: August 22, 2019 | Original: August 21, 2019

The Spanish American War , while dominating the media, also fueled the United States’ first media wars in the era of yellow journalism. Newspapers at the time screamed outrage, with headlines including, “Who Destroyed the Maine? $50,000 Reward,” “Spanish Treachery” and “Invasion!”

But while many newspapers in the late 19th century shifted to more of a tabloid style, the notion that their headlines played a major part in starting the war is often overblown, according to W. Joseph Campbell , a professor of communication at American University in Washington, D.C.

“No serious historian of the Spanish American War period embraces the notion that the yellow press of [ William Randolph] Hearst and [Joseph] Pulitzer fomented or brought on the war with Spain in 1898,” he says.

“Newspapers, after all, did not create the real policy differences between the United States and Spain over Spain's harsh colonial rule of Cuba.”

Newspapers Shift to Feature Bold Headlines and Illustrations

The media scene at the end of the 19th century was robust and highly competitive. It was also experimental, says Campbell. Most newspapers at the time had been typographically bland, with narrow columns and headlines and few illustrations. Then, starting in 1897, half-tone photographs were incorporated into daily issues.

According to Campbell, yellow journalism, in turn, was a distinct genre that featured bold typography, multicolumn headlines, generous and imaginative illustrations, as well as “a keen taste for self-promotion, and an inclination to take an activist role in news reporting.”

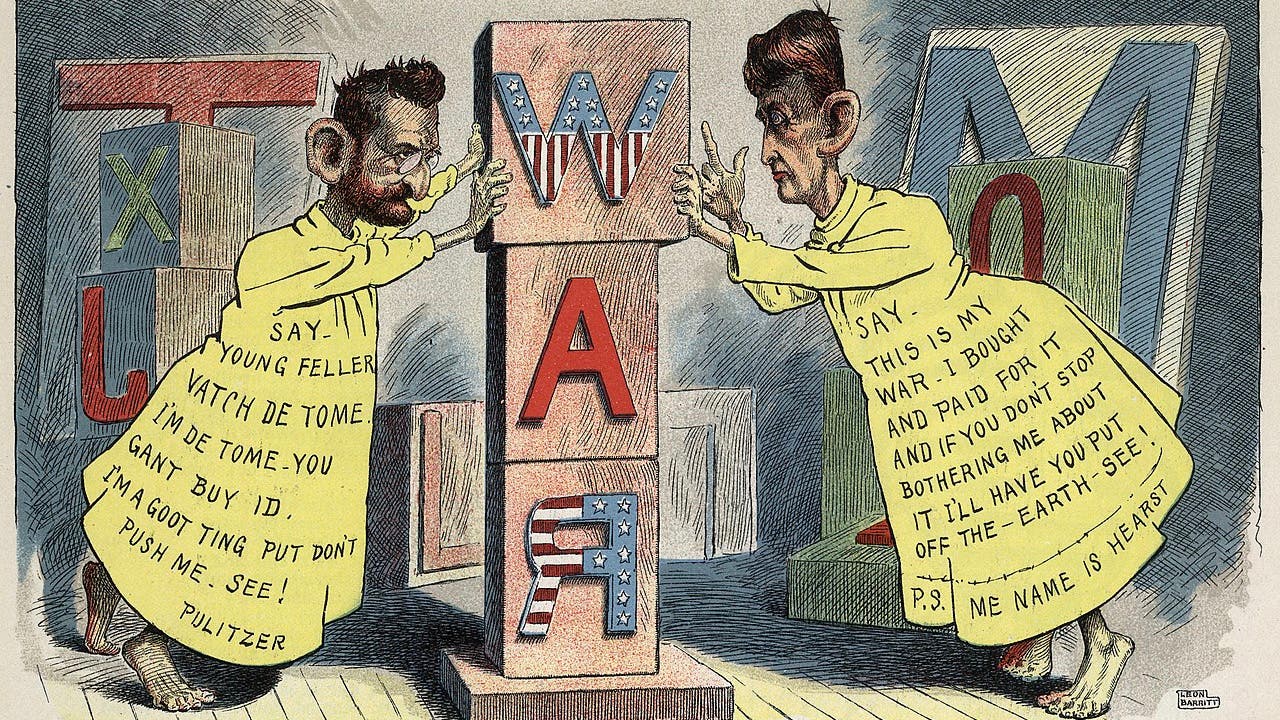

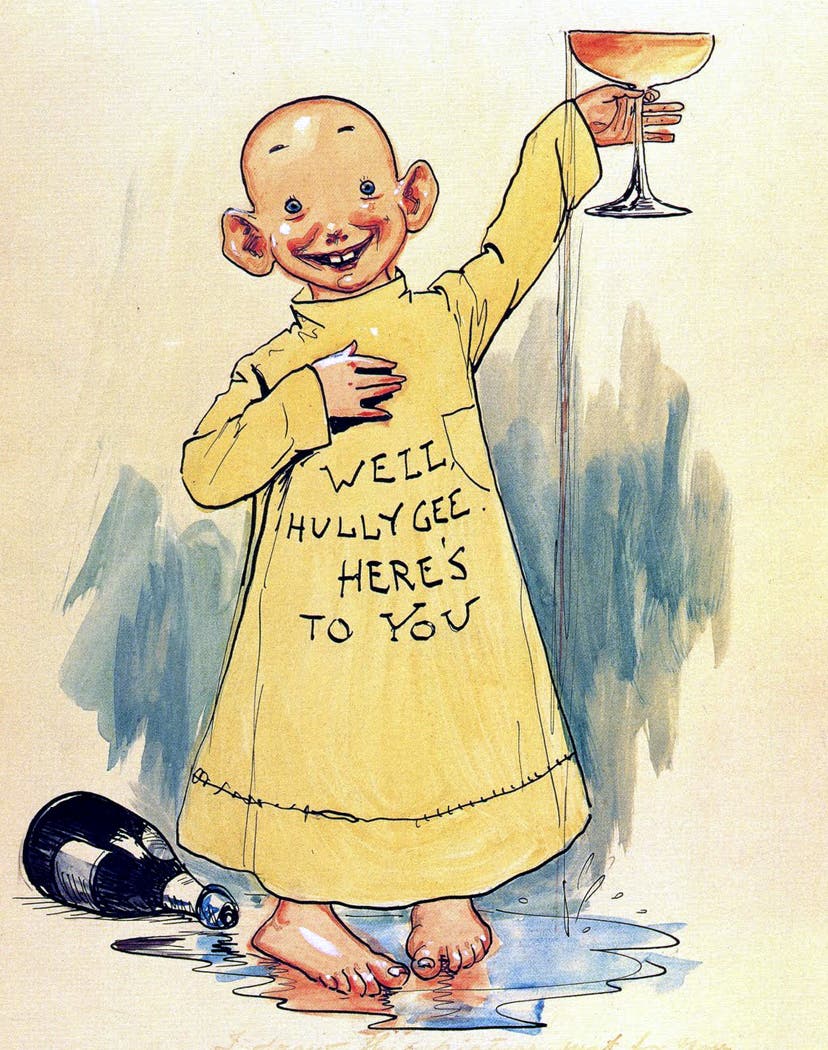

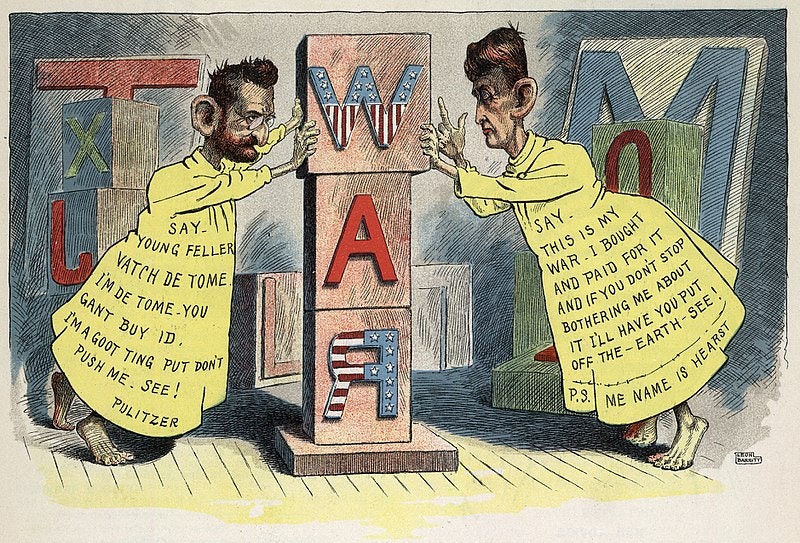

In fact, the term "yellow journalism" was born from a rivalry between the two newspaper giants of the era: Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World and William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal. Starting in 1895, Pulitzer printed a comic strip featuring a boy in a yellow nightshirt, entitled the “Yellow Kid.” Hearst then poached the cartoon’s creator and ran the strip in his newspaper. A critic at the New York Press, in an effort to shame the newspapers' sensationalistic approach, coined the term "Yellow-Kid Journalism" after the cartoon. The term was then shortened to "Yellow Journalism."

“It was said of Hearst that he wanted New York American readers to look at page one and say, ‘Gee whiz,’ to turn to page two and exclaim, ‘Holy Moses,’ and then at page three, shout ‘God Almighty!’” writes Edwin Diamond in his book, Behind the Times .

That sort of attention-grabbing was evident in the media’s coverage of the Spanish American War. But while the era’s newspapers may have heightened public calls for U.S. entry into the conflict, there were multiple political factors that led to the war’s outbreak.

“Newspapers did not cause the Cuban rebellion that began in 1895 and was a precursor to the Spanish American War,” says Campbell. “And there is no evidence that the administration of President William McKinley turned to the yellow press for foreign policy guidance.”

“But this notion lives on because, like most media myths, it makes for a delicious tale, one readily retold,” Campbell says. “It also strips away complexity and offers an easy-to-grasp, if badly misleading, explanation about why the country went to war in 1898.”

The myth also survives, Campbell says, because it purports the power of the news media at its most malignant. “That is, the media at their worst can lead the country into a war it otherwise would not have fought,” he says.

Sinking of U.S.S. Maine Bring Tensions to a Head

According to the U.S. Office of the Historian , tensions had been brewing in the long-held Spanish colony of Cuba off and on for much of the 19th century, intensifying in the 1890s, with many Americans calling on Spain to withdraw.

“Hearst and Pulitzer devoted more and more attention to the Cuban struggle for independence, at times accentuating the harshness of Spanish rule or the nobility of the revolutionaries, and occasionally printing rousing stories that proved to be false,” the office states. “This sort of coverage, complete with bold headlines and creative drawings of events, sold a lot of papers for both publishers.”

Things came to a head in Cuba on February 15, 1898, with the sinking of the USS Maine in Havana harbor.

“Sober observers and an initial report by the colonial government of Cuba concluded that the explosion had occurred on board, but Hearst and Pulitzer, who had for several years been selling papers by fanning anti-Spanish public opinion in the United States, published rumors of plots to sink the ship,” the Office of the Historian reports. “... By early May, the Spanish American War had begun .”

Despite intense newspaper coverage of the strife, the office agrees that while yellow journalism showed the media could capture attention and influence public reaction, it did not cause the war.

“In spite of Hearst’s often quoted statement—’You furnish the pictures, I’ll provide the war!’—other factors played a greater role in leading to the outbreak of war,” the office states. “The papers did not create anti-Spanish sentiments out of thin air, nor did the publishers fabricate the events to which the U.S. public and politicians reacted so strongly.”

The office further points out that influential figures like Theodore Roosevelt had been leading a drive for U.S. expansion overseas. And that push had been gaining strength since the 1880s.

In the meantime, newspapers’ active voice in the buildup to the war spun forward a shift in the medium.

“Out of yellow journalism’s excess came a fine new model of newspapering,” Geneva Overholser writes in the forward of David Spencer’s book, The Yellow Journalism: The Press and America , “and Pulitzer’s name is now linked with the best work the craft can produce.”

HISTORY Vault

Stream thousands of hours of acclaimed series, probing documentaries and captivating specials commercial-free in HISTORY Vault

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Collections

- Support PDR

Search The Public Domain Review

Yellow Journalism: The “Fake News” of the 19th Century

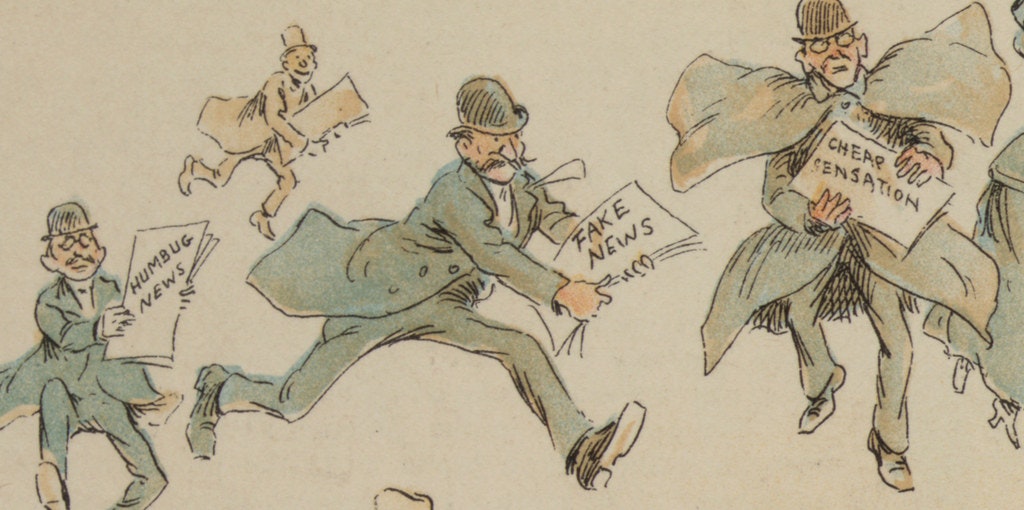

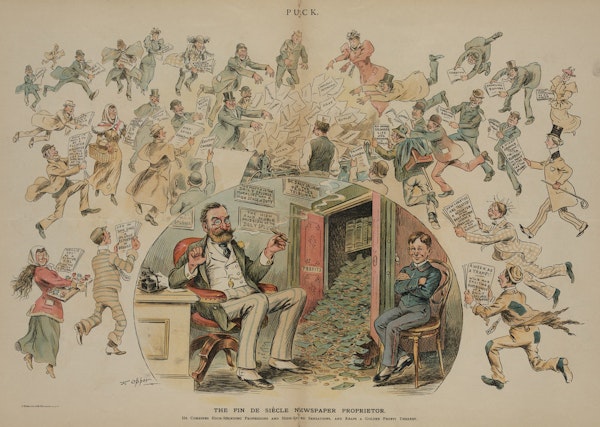

Detail from The Fin de Siècle Newspaper Proprietor , an illustration featured in an 1894 issue of Puck magazine. Amid the flurry of eager paper-clutching public, one holds a publication brandished with the words "Fake News". See full image below — Source .

It is perhaps not so surprising to hear that the problem of "fake news" — media outlets adopting sensationalism to the point of fantasy — is nothing new. Although, as Robert Darnton explained in the NYRB recently, the peddling of public lies for political gain (or simply financial profit) can be found in most periods of history dating back to antiquity, it is in the late 19th-century phenomenon of "Yellow Journalism" that it first seems to reach the widespread outcry and fever pitch of scandal familiar today. Why yellow? The reasons are not totally clear. Some sources point to the yellow ink the publications would sometimes use, though it more likely stems from the popular Yellow Kid cartoon that first ran in Joseph Pulitzer's New York World , and later William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal , the two newspapers engaged in the circulation war at the heart of the furore.

Although these days his name is somewhat synonymous with journalism of the highest standards, through association with the Pulitzer Prize established by provisions in his will, Joseph Pulitzer had a very different reputation while alive. After purchasing The New York World in 1884 and rapidly increasing circulation through the publication of sensationalist stories he earned the dubious honour of being the pioneer of tabloid journalism. He soon had a competitor in the field when his rival William Randolph Hearst acquired the The New York Journal in 1885 (originally begun by Joseph's brother Albert). The rivalry was fierce, each trying to out do each other with ever more sensational and salacious stories. At a meeting of prominent journalists in 1889 Florida Daily Citizen editor Lorettus Metcalf claimed that due to their competition “the evil grew until publishers all over the country began to think that perhaps at heart the public might really prefer vulgarity”.

The phenomenon can be seen to reach its most rampant heights, and most exemplary period, in the lead up to the Spanish-American War — a conflict that some dubbed " The Journal 's War" due to Hearst's immense influence in stoking the fires of anti-Spanish sentiment in the U.S. Much of the coverage by both The New York World and The New York Journal was tainted by unsubstantiated claims, sensationalist propaganda, and outright factual errors. When the USS Maine exploded and sank in Havana Harbor on the evening of 15 February 1898, huge headlines in the Journal blamed Spain with no evidence at all. The phrase, "remember the Maine, to Hell with Spain", became a populist rousing call to action. The Spanish–American War began later that year.

Editorial cartoon by Leon Barritt for June 1898 issue of Vim magazine, showing Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst both attired as the Yellow Kid comics character and competitively claiming ownership of the war — Source .

As we've witnessed over recent weeks, from certain mouths the use of the term "fake news" has strayed from simply describing factually incorrect reporting. Likewise would those in power paste the label of "yellow journalism" on factually correct reporting which didn't quite paint the picture they'd like? Yes, indeed. As Timeline reports , in 1925 a certain Benito Mussolini derided reports of his ill health as being lies by the "yellow press", saying the papers were "ready to stop at nothing to increase circulation and to make more money". The reports, however, turned out to be factually accurate. He'd go onto rule the country for another eighteen years.

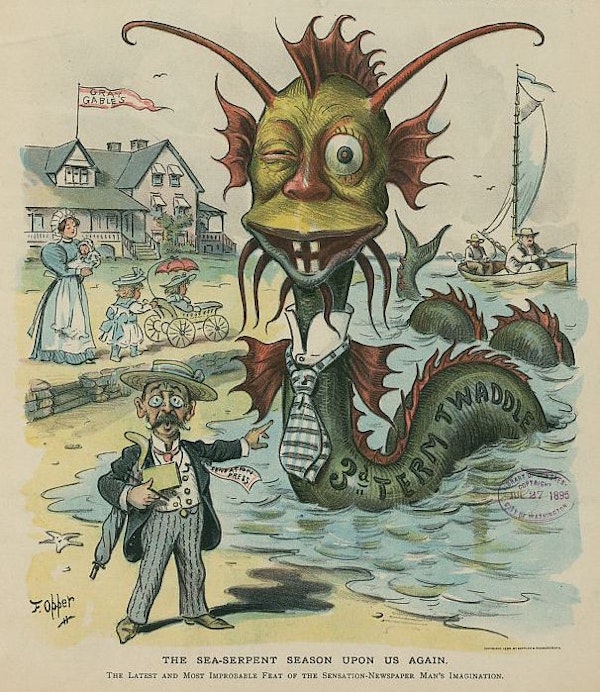

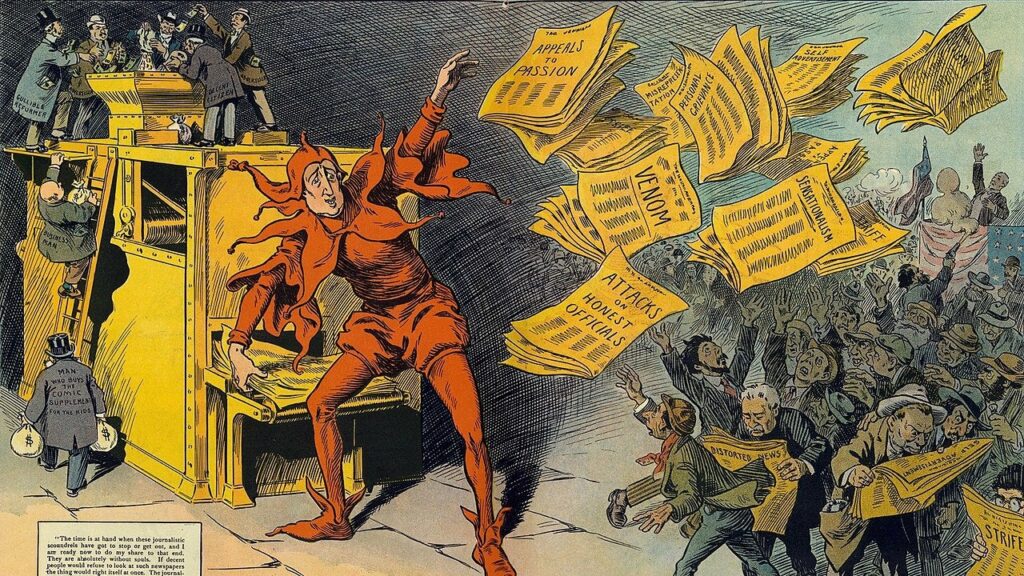

Featured below are a selection of illustrations from the wonderful Puck magazine commenting on the phenomenon, all found in the collection of the Library of Congress.

- Humour & Satire

- Illustrations

- 19th Century

- 20th Century

Indexed under…

- Yellow journalism

The Yellow Press , illustration from 1910 depicting William Randolph Hearst as a jester tossing newspapers with headlines such as 'Appeals to Passion, Venom, Sensationalism, Attacks on Honest Officials, Strife, Distorted News, Personal Grievance, [and] Misrepresentation' to a crowd of eager readers — Source .

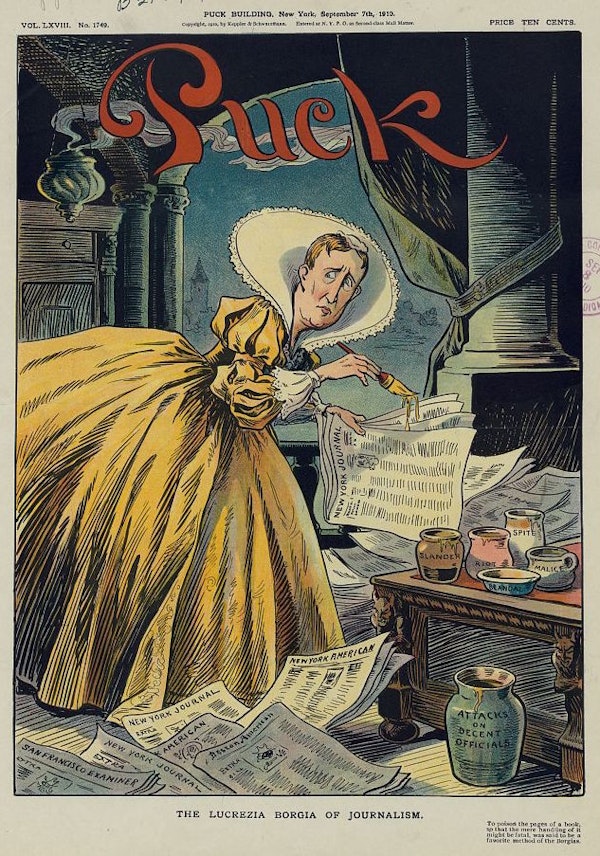

The Lucrezia Borgia of Journalism (1910) — William Randolph Hearst, wearing a bright yellow dress, as Lucrezia Borgia painting poison from pots labeled 'Slander', 'Riot', 'Scandal', 'Malice', and 'Spite' on various newspapers scattered on the floor, where also sits a further tub labelled 'Attacks on Decent Officials'. The note to the bottom right explains: 'To poison the pages of a book, so that the mere handling of it might be fatal, was said to be a favorite method of the Borgias' — Source .

Uncle Sam's Dream of Conquest and Carnage - Caused by Reading the Jingo Newspapers (1895) — Source .

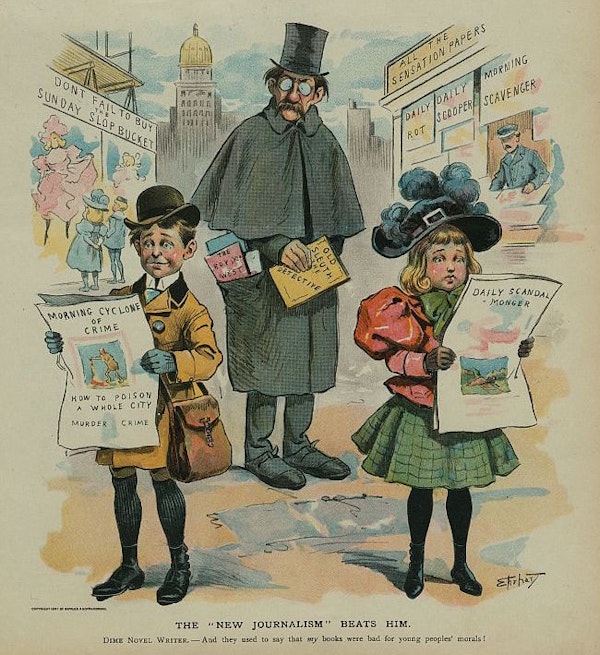

The 'New Journalism' Beats Him (1897) — Source .

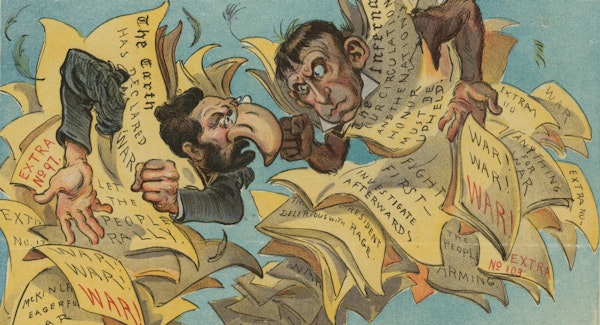

Detail from Honor to McKinley! (1898), showing Pulitzer and Hearst, caricatured as a parrot and monkey respectively, battling it out amid a flurry of pages from the Yellow Press. The rest of the picture shows President McKinley below them ignoring their cries for war. Instead he reads a paper entitled 'The People of the United States have full confidence in your Patriotism, Integrity, & Bravery. They know you will act justly and wisely: decent press'. Such praise of McKinley's resistance to war would not last for long: a month later he asked Congress for authority to send American troops to Cuba — Source .

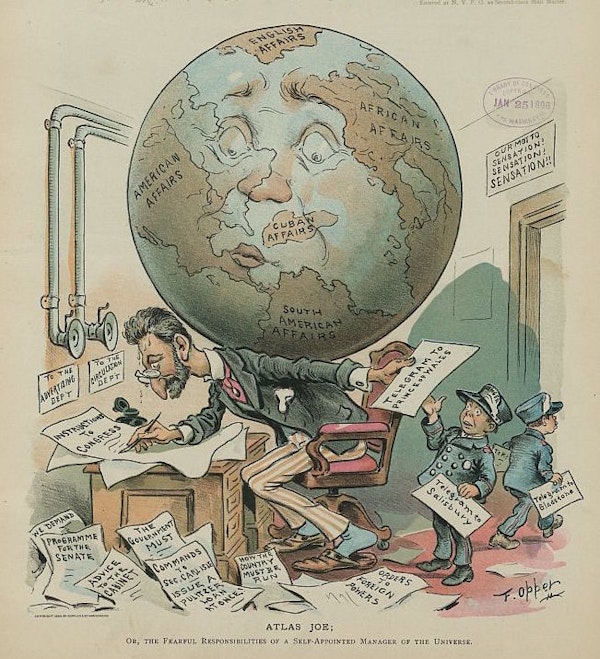

Atlas Joe; or, The Fearful Responsibilities of a Self-Appointed Manager of the Universe (1896), note the message hanging on the wall: 'Our Motto - Sensation! Sensation! Sensation!!' — Source .

The Fin de Siècle Newspaper Proprietor (1894), the central figure presumably Joseph Pulitzer — Source .

The Rape of Lucrece (1906) — Source .

The Sea-Serpent Season Upon us Again (1895) — Source .

Feb 21, 2017

If You Liked This…

Get Our Newsletter

Our latest content, your inbox, every fortnight

Prints for Your Walls

Explore our selection of fine art prints, all custom made to the highest standards, framed or unframed, and shipped to your door.

Start Exploring

{{ $localize("payment.title") }}

{{ $localize('payment.no_payment') }}

Pay by Credit Card

Pay with PayPal

{{ $localize('cart.summary') }}

Click for Delivery Estimates

Sorry, we cannot ship to P.O. Boxes.

- Corrections

What Was Yellow Journalism? A History of the Free Press in America

Although many might think the term “fake news” is a recent phenomenon, media bias has been around as long as the free press, thanks to yellow journalism!

In the late 1800s, as more Americans moved to urban areas and began to read newspapers, rival newspapers began competing for readers by focusing on sensationalism rather than pure facts. Yellow journalism printed highly sensationalized news, partisan, and prone to editorialism (opinions) rather than simply informing readers of the facts. The famous competition between rival publishers Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst intensified in the 1890s during the Cuban War of Independence, which coincided with newspapers’ incorporations of photographs and colored ink. To sell more newspapers, publishers incorporated illustrations and sensational titles. Allegedly, this media sensationalism helped push America into the Spanish-American War in 1898.

History of the Free Press in America

The first newspaper was printed in the Thirteen Colonies in 1690 but quickly folded. Thirty years later, a newspaper returned, run by the older brother of famous Founding Father Benjamin Franklin. Franklin was later given the paper, which he named The Pennsylvania Gazette . He published opinionated letters written by readers, as well as his own musings. After its initial foray into partisanship during the French and Indian War (1754-63) , the Gazette became more partisan during the American Revolution Era , when it heavily criticized British taxes and repressions of the colonies.

In nearby New York City, The New York Weekly Journal was founded by John Peter Zenger in 1733. It quickly began criticizing the colonial governor, who had Zenger arrested. A jury acquitted Zenger because it believed the newspaper’s criticisms of the governor to be true. This groundbreaking trial established the precedent of a free press in America: a newspaper could not be punished for telling the truth, even if the truth upset political leaders.

Free Press in the Early American Republic

Newspapers had helped rally public opinion during the American Revolution by criticizing the British. When the Bill of Rights was written in 1789 to add to the United States Constitution, its First Amendment was devoted to the freedom of expression. It included freedom of the press. If the Bill of Rights or Constitution protected something, no law could be arbitrarily passed that limited it. In 1798, the Sedition Act was passed to prevent Americans from criticizing the government, which some considered to be a major violation of the First Amendment.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription.

The Sedition Act expired in 1801 , and new US President Thomas Jefferson pardoned all of those who had been convicted of breaking it. While this was a move in favor of the free press, it did not answer the question of whether or not a law like the Sedition Act was constitutional. By this point, there were about 200 newspapers in the United States. Since relatively few Americans were literate, newspapers tended to publish information favored by the merchant class and wealthy landowners. Although the news was biased, the lack of widespread readership prevented the need for competitive sensationalism.

Partisan & Penny Newspaper Era (1830-1860)

A surge in newspaper readership began in the 1820s. Thanks to industrialization and increased literacy, there was now both the supply of and demand for newspaper print. In urban areas, newspapers competed for an audience among the new middle class. Now that there was competition to attract readers, these new penny papers (named for their one-cent price) began using sensationalism and popular rhetoric to appear to common citizens. Ironically, it was partisan newspapers, which were allied with a local political party, that were less sensational. These more expensive newspapers tended to have government support and a loyal readership, meaning competing penny papers had to become more entertaining to attract readers.

In New York City, competing penny papers–the New York Herald and the New York Sun –often criticized each other and were highly susceptible to any whims of editors. By the 1850s, however, newspapers became more orderly and professional, with their respective staffs trying to make them more logical and orderly to read. Although newspapers became more professional in terms of delivering news, they did not shed their partisan leanings . Part of this was due to partisan leanings of owners and editors, while part was due to government subsidies established by partisan politicians.

The US Civil War & Its Effect on Journalism

The outbreak of the US Civil War in 1861 led to a tremendous demand for news, which led newspapers to adopt new technologies like the telegraph and use extensive railroad travel to get reporters and correspondents to the action. For the first time, the public could learn about the results of battles within days rather than weeks. As the public also wanted images, newspapers dramatically increased their use of illustrations (photographs would not enter newspapers until 1880 ). Reporters were sent to battlefields for the first time to provide up-to-date and accurate information.

Due to the intense emotions surrounding the conflict, partisanship and satire were common. Northern newspapers frequently mocked the Confederacy in political cartoons and articles and vice versa. However, the Confederacy had relatively few newspapers due to both having few large cities and having few printing presses. Due to the lack of photographs, newspapers may have used emotional language and elaborate drawings to attract readers and convey the same level of intensity as photos. The tragic assassination of US President Abraham Lincoln only weeks before the end of the Civil War received elaborate news coverage.

Stirring Up the Masses: Gilded Age Journalism

After the US Civil War (1861-65), the Republican Party, which was the political party of the Union, dominated national politics. In urban areas, newspapers went from being divided along political party lines to being more focused on populist issues. A continued increase in literacy rates meant that newspapers could be successful by appealing to the middle class rather than the wealthy. As a result, journalism during the Gilded Age (late 1860s-1890s) became focused on exposing the corruption of the wealthy and political leaders.

The theme of rooting out corruption was well-founded, as politics during the era included political machines in large cities. In this era, prior to civil service laws, elected officials had tremendous control over the distribution of government jobs and services. Political loyalists were awarded government jobs, even if they were entirely unqualified. City neighborhoods that did not vote for a winning candidate could be denied municipal services like water, sewer, police protection, fire protection, and parks. Although newspaper coverage was still heavily biased, it did hold government officials accountable by exposing corruption to angry voters.

Yellow [Kid] Journalism

Improved newspaper technology during the Gilded Age allowed for new innovations like the inclusion of photographs and colored cartoons . The first colored cartoons, in 1894, were published by newspaper tycoon Joseph Pulitzer. One popular comic, Hogan’s Alley , had a character named “the yellow kid.” Rival publisher William Randolph Hearst wanted his own popular “yellow kid” and even hired the original artist away from Pulitzer. Thus, the sensationalized news reporting of the era, which newspapers used to compete for readers, became known as yellow journalism.

Yellow journalism became most known through the Spanish-American War of 1898 . Between 1895 and 1898, the growing Cuban War of Independence between Spain’s colony of Cuba and its imperial ruler was sensationalized by Pulitzer and Hearst. Both publishers sensationalized the situation in Cuba and even printed false stories to make Spain look more barbaric. When the USS Maine exploded in Havana Harbor in early 1898, newspapers quickly blamed Spain and encouraged swift retribution. Although the US government had its own goals in defeating Spain and seizing its colonies, it is undoubted that yellow journalism assisted in rallying public support around that goal.

Sensationalism vs. Censorship in Wartime

While newspapers were highly partisan and sensationalized between 1800 and 1900, the US Civil War set a precedent of government censorship during wartime. In 1861, the Post Office Department was allowed to censor newspapers that were allegedly printing pro-South material. Similar to its refusal to deliver mail from the South, the Post Office would refuse to deliver any newspapers it thought unpatriotic to the Union. The following year, the War Department began directly censoring the printing of newspapers in the North.

Censorship returned during World War I , with stories from the front having to be approved by military authorities . News had to be patriotic, support the war effort, and “maintain high morale.” During this era, newspapers were also limited in which battlefield photos they could publish, including that they could hurt public morale . However, this began to change during World War II . In September 1943, the efforts of Life magazine correspondent Cal Whipple convinced US President Franklin D. Roosevelt to reverse course and allow the publication of the now-famous photo by George Strock of dead US soldiers on a beach in the Pacific theater of the war. It turned out that the American public appreciated the honesty.

Unfiltered Images: 1960s & Television News

Unfortunately, the debate over the appropriate role and action of the media returned with a vengeance in the 1950s. A new medium, television news, spread rapidly, complementing radio news that had been popular since the 1920s. For the first time, Americans could watch newsworthy events and not have information filtered through a journalist. Many accused the news media of returning to sensationalized coverage during the Second Red Scare of the early 1950s , amplifying fear of alleged communists in American society. However, the media could also be used strategically: the downfall of ultraconservative US Senator Joseph McCarthy , known for persecuting suspected communists and using false information to do so, began when the White House leaked damaging info about him to the press.

Television news proved to be extremely powerful in shaping public opinion. During the early 1960s , video clips were broadcast around the world showing violent police responses to peaceful Civil Rights protesters . Public support for segregationists and racists quickly evaporated, and major Civil Rights legislation was finally passed in Congress. Television news was difficult to accuse of sensationalism, as it simply showed the actual events occurring. Later in the same decade, television news also quickly eroded public support for the Vietnam War . Although US President Lyndon B. Johnson complained that TV coverage of the war was divisive, censorship of non-secret information did not return.

Changing Norms in Reporting Politics

The Second Red Scare , Civil Rights Movement, and Vietnam War opened deep social and cultural divides in the United States. Many accused the news media, via newspapers, radio, and television, of furthering the divide. During the 1960s, political norms regarding media deference to political leaders began to wane. Up through the presidency of John F. Kennedy, the news media largely ignored the sex scandals of presidents. Part of this may have been rooted in the patriarchy, as women were poorly represented in newsrooms during the era.

However, media deference toward presidents collapsed during the Vietnam War. Richard M. Nixon, the winner of the 1968 presidential election, had an especially negative relationship with the news media. He issued blanket criticisms of “the press” and hated the principle of the media using anonymous sources. As a result of Nixon’s heavy-handed disdain for “the media,” it was not unsurprising that the media did not hold back on its reporting of the Watergate Scandal that erupted in 1973. When Nixon eventually resigned in August 1974, the news media was allegedly at its peak of public support: the free press had overcome political threats to report the facts and root out corruption.

Post-Nixon: 24-Hour News Cycle & Media Bias

After the Watergate scandal, the relationship between the media and political figures changed. In 1987, the Gary Hart scandal was widely reported by both the mainstream media and the tabloids, raising questions about the proper role of the media regarding politicians’ personal lives. The media focus on the personal life of US Senator Gary Hart (D-CO) was a break from precedent and utterly destroyed his candidacy for the 1988 Democratic presidential nomination. This new era where the media could, and would, focus on the personal lives and histories of politicians and others raised debates about media bias.

One reason for the expansion of what the media could focus on was the birth of the 24-hour news cycle , which began around 1980. The rise of cable television had created many more viewing options, and TV stations had to compete for viewers. Similar to the expansion of newspapers leading to sensationalized coverage 150 years earlier, the expansion of TV news into a 24-hour cycle resulted in more aggressive journalism. Many people, however, thought the coverage was often biased based on the political leanings of the journalists and media companies: liberal-leaning networks would nitpick the lives and actions of conservatives but leave liberals largely unscathed, and conservative-learning networks would do the opposite.

Today: Internet News & “Fake News”

In the early 2000s, the 24-hour news cycle became supplemented by the rise of Internet news. Today, Internet news and social media have largely replaced printed newspapers , moving yellow journalism to a new medium featuring terms like “ clickbait ” and “ going viral .” Similar to newspapers trying to attract readers with colorful images (“yellow kid” journalism), today’s news websites use dramatic titles and descriptions to try to draw viewers. The use of such titles is known as clickbait and is often criticized as misleading. However, Internet news differs from the newspaper era in one key aspect: instead of trying to draw in all readers, media outlets are accused of playing to their distinct groups of readers .

Instead of focusing on the facts, news outlets are often criticized for focusing on parts of stories that will appeal to existing viewers and readers. This has led to the rise of accusations of “fake news.” Although fake news technically means news stories containing false information, the term has become genericized to include information that is seen as biased. A common term for media and political focus on unimportant trivialities to criticize an individual or group is often called a “nothing-burger .” However, the Internet allows people to visually alter photographs and news stories to include false information and then spread them via social media, making widespread fake news a recent phenomenon .

The French & Indian War: Setting the Stage for the American Revolution

By Owen Rust MA Economics in progress w/ MPA Owen is a high school teacher and college adjunct in West Texas. He has an MPA degree from the University of Wyoming and is close to completing a Master’s in Finance and Economics from West Texas A&M. He has taught World History, U.S. History, and freshman and sophomore English at the high school level, and Economics, Government, and Sociology at the college level as a dual-credit instructor and adjunct. His interests include Government and Politics, Economics, and Sociology.

Frequently Read Together

The Political Effects of the American Revolutionary War

The Political Effects of the American Civil War

The Spanish-American War: US Domination in the Western Hemisphere

- Subscriber Services

- For Authors

- Publications

- Archaeology

- Art & Architecture

- Bilingual dictionaries

- Classical studies

- Encyclopedias

- English Dictionaries and Thesauri

- Language reference

- Linguistics

- Media studies

- Medicine and health

- Names studies

- Performing arts

- Science and technology

- Social sciences

- Society and culture

- Overview Pages

- Subject Reference

- English Dictionaries

- Bilingual Dictionaries

Recently viewed (0)

- Save Search

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Related Content

Related overviews.

Joseph Pulitzer (1847—1911) Hungarian-born American newspaper proprietor and editor

William Randolph Hearst (1863—1951) American newspaper publisher and tycoon

More Like This

Show all results sharing these subjects:

- Business and Management

yellow journalism

Quick reference.

The forerunner of what we know today as sensationalist journalism. Developed at the turn of the 20th century in the US, the phrase was originally used to describe the journalism of Joseph Pulitzer, but became synonymous with the newspapers of William Randolph Hearst. At this time, when newspapers were the main source of news in America, it was common practice for a newspaper to report the editor's interpretation of the news rather than objective facts. If the information reported was inaccurate or biased, the public had little means of verification. Newspapers wielded much political power and, in order to increase circulation, the publishers of these papers often exploited their powerful position by sponsoring a flamboyant approach to news reporting that became known as ‘yellow journalism’. Hearst, for example, is often accused of having started the Spanish-American War of 1898 by inflaming opinion using this type of approach.

From: yellow journalism in A Dictionary of Marketing »

Subjects: Social sciences — Business and Management

Related content in Oxford Reference

Reference entries.

View all related items in Oxford Reference »

Search for: 'yellow journalism' in Oxford Reference »

- Oxford University Press

PRINTED FROM OXFORD REFERENCE (www.oxfordreference.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2023. All Rights Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single entry from a reference work in OR for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice ).

date: 31 March 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|195.158.225.230]

- 195.158.225.230

Character limit 500 /500

To Fix Fake News, Look To Yellow Journalism

Fake news has plenty of precedents in the history of mass media, and particularly, in the history of American journalism.

How The Internet Ruined Everything (Or Did It?)

Fake news is the latest culprit in the continuing saga of How The Internet Ruined Everything.

Here’s how the story goes: a mix of cynical political operators and business opportunists have blanketed the internet, and social networks in particular, with wholly manufactured news stories and publications. Conservative voters are far more susceptible to fake news, so the net effect of our fake news epidemic was to deliver the U.S. election to Donald Trump.

It’s hard to argue with the narrative, which has now been backed up with interviews by fake news producers , and with data on the spread of fake new stories . In answer to the big question this narrative raises—what now?—Jeff Jarvis and John Bothrick have written a terrific piece outlining some specific ways to combat fake news .

Yet we are unlikely to prevail in this battle if we treat the problem of fake news as a creature of the internet—or, for that matter, as a problem unto itself. Fake news is part of a larger problem of “click journalism”: media that focuses on getting online click-throughs, or on “clicking” with our pre-conceived bias.

Fake News’ Print-World Antecedents

Click journalism has plenty of precedents in the history of mass media , and particularly, in the history of American journalism. That history includes a period of journalism so disreputable that it coined a term: “yellow journalism.” As described by Joseph Patrick McKerns in his 1976 History of American Journalism :

The yellow journalism of the 1890’s and tabloid journalism of the 1920’s and the 1930’s stigmatized the press as a profit motivated purveyor of cheap thrills and vicarious experiences. To its many critics it seemed as though the press was using the freedom from regulation it enjoyed under the First Amendment to make money instead of using it to fulfill its vital role as an independent source of information in a democracy. The Commission on Freedom of the Press, chaired by Robert M. Hutchins, issued a report in 1947, A Free and Responsible Press (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1947) which urged the press to be “socially responsible.”

Thomas Arthur Gullason enumerates the features of yellow journalism as

a dependence on “the familiar aspects of sensationalism—crime news, scandal and gossip, divorces and sex, and stress upon the reporting of disasters and sports”; “the lavish use of pictures, many of them without significance, inviting the abuses of picture-stealing and ‘faked’ pictures;” and “impostures and frauds of various kinds, such as ‘faked’ interviews and stories.”

In her 1910 critique of the newspaper industry , Frances Fenton quoted President Theodore Roosevelt’s own accusation that contemporary newspapers “habitually and continually and as a matter of business practice every form of mendacity known to man, from the suppression of the truth and the suggestion of the false to the lie direct.”

Yellow Journalism’s Critics

Both at the time and in retrospect, critics of yellow journalism saw its sensationalism and dishonesty as a business strategy. Writing in 1922, Victor Yarros noted that

Some writers have not hesitated to indict the entire newspaper business-or profession-on such charges as deliberate suppression of certain kinds of news, distortion of news actually published, studied unfairness toward certain classes, political organizations and social movements, systematic catering to powerful groups of advertisers, brazen and vicious “faking,” and reckless disregard of decency, proportion and taste for the sake of increased profits.

That profit motive was even cited as a driver of the Spanish-American War, which by many accounts was fed by yellow journalism, and in particular, by the way the New York Press covered the sinking of the U.S.S. Maine in the port of Havana. Louis A. Pérez , himself part of the scholarly movement to question this tidy historical narrative, quotes a typical argument, made by Joseph E. Wisan in 1934: “the Spanish-American War would not have occurred had not the appearance of Hearst in New York journalism precipitated a bitter battle for newspaper circulation.”

History being made by an unscrupulous press, driven to sensationalize stories and fabricate facts in a quest for eyeballs and dollars….yep, sounds familiar. But it’s not a straight line from the yellow journalism of a century ago to the fake news of today’s internet, unless you want to skip over a bunch of decades in which we had some expectation of the news being actually true.

The Rise of Real News

As early as 1898, Sidney Pomerantz notes in his history of the New York Press , a publication for the newspaper industry wrote that “The public is becoming heartily sick of fake news and fake extras. Some of the newspapers in this town have printed so many lying dispatches that people are beginning to mistrust any statement they make.” Pomerantz himself argues that “[b]y the turn of the century, yellow journalism was on the decline, with the World leading the way back to ‘normalcy.’” He attributes this shift to the success of the New York Times , which proved the profitability of a “highly conservative paper,” particularly relative to the hard times at the New York Journal , the flagship “yellow” publication owned by William Randolph Hearst.

But to say that yellow journalism waned because the public wanted something better is to oversimplify the story. Alongside the public, the courts’ attitudes towards the media shifted, inspired less by the outright falsehoods published in turn-of-the-century papers than by their intrusions into the lives of public figures. In her article “ Judging Journalism ,” Amy Gajda points out that our notion of a constitutional right to privacy actually traces back to late nineteenth-century concern with “ the prying eyes of yellow journalists and gossip-mongers.” This fed a growing body of legal scholarship and opinion that placed privacy rights ahead of First Amendment rights: Gajda notes that by the 1920s and 30s, “the weight of decisions during this period held newspapers and other related media responsible for privacy invasions with growing frequency.”

In addition to public opinions and the courts, the early twentieth century saw a third check on yellow journalism and fake news: the newspaper industry itself. In 1910, W.E. Miller proposed the industry’s first code of ethics , as adopted by the Kansas State Editorial Association:

Lies . We condemn against truth: (1) The publication of fake illustrations of men and events of news interest, however marked their similarity, without an accompanying statement that they are not real pictures of the event or person but only suggestive imitations. (2) The publication of fake interviews made up of the assumed views of an individual, without his consent. (3) The publication of interviews in quotations unless the exact, approved language of the interviewed be used. When an interview is not an exact quotation it should be obvious in the reading that only the thought and impression of the interviewer is being reported. (4) The issuance of fake news dispatches whether the same have for their purpose the influencing of stock quotations, elections, or the sale of securities or merchandise. Some of the greatest advertising in the world has been stolen through the news columns in the form of dispatches from unscrupulous press agents. Millions have been made on the rise and fall of stock quotations caused by newspaper lies, sent out by designing reporters.

Writing about the Kansas code 12 years later, Alfred G. Hill argued that it had been successful in establishing a norm of media truthfulness:

In regard to the condemning of untruthful statements, there has been an advance since the adoption of the Code. There is now practically no use of fake illustrations and fake interviews. However, interviews are still published in Kansas, just as in other states, which violate the requirement in the Code that only exact quotations be used in quotation marks.

The adoption of similar codes across the US was so widespread that by 1955, Eustace Cullinan could reasonably claim in the American Bar Association Journal that “[i]n recent decades the press of the nation has developed a code of ethics to which it adheres within reason, though sometimes stooping a little to get results.”

Both the waxing and waning of yellow journalism offer important insights into the problem of fake news as it exists today. First and foremost, we have to stop seeing this as a technology story: lousy, irresponsible media not only predates the internet, but it predates the printing press. (Do you really think Homer recounted every detail of the Trojan War with precise accuracy?) The internet may have made fake news a bigger problem, and it has certainly made it a more complicated problem to tackle, but there is a longstanding tension between a public interest in conscientious reporting and private interests in salacious headlines and easy profits.

Just as important, we have to stop seeing this as a fake news story. While early twentieth-century media critics invariably cited outright fabrication as part of the yellow journalism phenomenon, they recognized that fake news was only part of a larger problem of sensationalistic headlines, intrusive reporting, and journalism that placed sales over accuracy.

Where That Leaves Us

What observers of yellow journalism recognized —and what we need to recognize today—is that fake news does not appear in a vacuum. Established media outlets and social networks are not just supported by the dollars-for-clicks they earn by displaying fake news headlines; they are increasingly built upon a common culture of clickbait-y headlines, partisan hyperbole, and a prioritization of human interest stories over hard news.

We can feel superior for fact-checking what we share, and recognizing the difference between a true and a false headline. But we’re not going to conquer the problem of fake news unless we reject the much broader set of stories, news sources, and websites in which they are situated: the ever-growing slice of online, print, and broadcast media that feeds us celebrity gossip and listicles in place of actual content.

Just as with the demise of yellow journalism, each of us has a role to play in shaping the relative profitability of quality journalism and the click journalism with which fake news is profoundly entangled. As long as we give our time, our dollars and our clicks to unreputable sites like these , fake news will continue to thrive. Or we can read, share and support the news and commentary produced by responsible media outlets, and see click journalism wither away, just as yellow journalism did a century ago.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

More Stories

- The Border Presidents and Civil Rights

- Eurasianism: A Primer

- Saffron: The Story of the World’s Most Expensive Spice

- The Fencing Moral Panic of Elizabethan London

Recent Posts

- The Genius of Georgette Chen

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Yellow Journalism: “Fake News” in the 19th century

Saying that we have a tumultuous relationship with the media and journalism these days is an understatement. Every bit of news that comes out has its naysayers and those who insist that it just isn’t true. This distrust for journalism of all sorts isn’t new, though. In fact, it’s been around since the 1890s, and actually has a name associated with it–yellow journalism.

Yellow journalism isn’t fake news, per se, but instead, is journalism that uses attention-grabbing headlines while having very little substance otherwise. This type of journalism relies on sensationalizing even the mundane, just to draw readers in.

The headlines could be used to shock and mislead readers while also making the stories within sound irresistible. In this way, the newspapers that partook in the yellow journalism trend were able to sell quite a few more papers than usual.

While the idea of yellow journalism seems simple enough, it actually has a long, somewhat convoluted history. Let’s look a little deeper into this unsavory practice and its storied past.

What is Yellow Journalism?

Yellow journalism refers to a style of journalism that leans towards sensationalistic, and even false, claims and headlines to boost readership and sales. This style of journalism takes advantage of the emotions of the readers, catching their attention and making consumers feel like they have to know what the story is about.

Unfortunately, beneath the eye-catching headlines, the stories associated with yellow journalism often lacked truth and accurate reporting. Instead, it would exaggerate and distort the truth to appeal to the readers, even at the cost of honesty.

A few yellow journalism examples are:

- When the USS Maine sank in the Havana harbor in Cuba, suspicions were immediately high. Newspapers like the Journal were quick to blame Spain for the explosion, even when there were no concrete conclusions about the real cause of the tragedy. Headlines like these drummed up anti-Spain sentiment and played a big part in the outbreak of the Spanish-American War.

- Another sensationalist headline in the New York Journal, this article used the words “Awful Slaughter” to full effect, printing them in bold, capital letters, much larger than any other headlines. Referencing the Philippine-American War, the Journal made sure to drum up negative emotions in order to convince readers to purchase the paper so they could read about this so-called slaughter.

The Beginning of Yellow Journalism

Born in the late 1800s, yellow journalism first appeared in the newspapers of the day. Specifically, the trend was started during a feud between two New York City newspapers, the New York World and the New York Journal.

The two papers were competing for readers, but the heart of this feud was actually between the publishers Joseph Pultizer, of the Pulitzer prize fame, and William Randolph Hearst.

Pulitzer had bought the New York World in 1883, turning the relatively small paper into one of the biggest in the country using yellow journalism. Even if it didn’t have the yellow journalism moniker at the time, Pulitzer was clearly sensationalizing the headlines in his paper, reporting on politics and social issues that were close to the hearts of many New Yorkers.

At first, he stood unchallenged, but in 1895, that all changed. William Randolph Hearst arrived in New York City and quickly bought the rival newspaper to the New York World , the New York Journal.

Hearst, the son of a mining tycoon from California, was experienced with bringing success to newspapers. His previous paper, the San Francisco Examiner , was a huge success back in California, and by the time Hearst moved to New York, he was ready for a repeat with the Journal.

The Rivalry Heats Up

Once Hearst acquired the Journal, he started to hire journalists and cartoonists to fill out his new paper. One employee that he lured away from the New York World was comic author Richard F. Outcault.

Richard’s comics were one of the biggest draws of the World, and thus, when he switched teams, his readers from the World were quick to switch to the Journal. A character from one of Richard’s comic strips, Hogan’s Alley, would be the inspiration for giving yellow journalism its name.

This character was aptly named The Yellow Kid and was a bald child wearing a long yellow shirt. With loud, brash dialogue and catchphrases on his yellow smock, The Yellow Kid was a fitting mascot for yellow journalism and was even more fitting for the fact he had been featured in both the World and the Journal at different times.

The name “yellow journalism” was first created by Edwin Wardman, an editor of yet another New York paper, the New York Press. He was the first to publish the term, using both “yellow journalism” and “yellow kid journalism” to refer to the type of writing coming out of the Pulitzer-Hearst feud.

Yellow Journalism and the Spanish-American War

The rivalry between Heart and Pulitver hit its peak between the years of 1895 and 1898, and this just so happened to coincide with the start of the Spanish-American War. When it comes to dramatic, overblown headlines, there is no better fodder than war.

It all began with the Cuban War of Independence in Spain’s Cuban colony. Both Heast and Pulitzer printed stories greatly exaggerate the conflict, which involved Cuba looking to become independent. Both publishers were hyper-critical of the Spanish occupation, even printing false stories just to garner attention. It wasn’t long, though, before the conflict would provide even more yellow journalism material for the World and Journal.

In 1898, the American battleship, the U.S.S Maine, had docked in the Havana harbor in Cuba. Its presence was meant to be a display of power for the U.S. and to help keep the simmering conflict between Spain and Cuba from boiling over into the United States.

The Maine wasn’t there long before tragedy struck. On February 15, 1898, an explosion ricocheted through the harbor, originating from the American battleship. The explosion was violent and devastating for those aboard the ship–266 of the 354 people aboard the ship perished.

Even now, there is no concrete explanation for the sinking of the Maine, but at the time, the prevailing idea was that Spain had sunk the battleship. This idea was spurred on by yellow journalism coming from newspapers across the United States, but the New York World and New York Journal were exceptionally harsh and sensationalistic.

Hearst especially was fixated on fanning the flames of war. One quote had him telling artist Frederic Remington,

“You furnish the pictures and I’ll furnish the war.”

With anti-Spain sentiment at an all-time high, the public in New York City was clamoring for stories that reflected their already strong opinions. So while Hearst, and to a lesser extent, Pulitzer, would publish stories with varying degrees of truth in them, readers still purchased the papers. They didn’t need to be convinced that the stories in the paper were truthful–their minds had already been made up, and the yellow journalism in the papers only validated these already existing opinions.

It’s not known if the yellow journalism in these publications swayed political officials one way or the other when it came to the war with Spain. War was inevitable, though, and once a naval investigation came to the conclusion that the Maine must have been sunk by an underwater mine, yellow journalism had people ready to enter the fray.

In May of that same year, the Spanish-American War began in earnest. Hearst and Pulizter continued to produce pieces that were more inflammatory than they were honest, but in just a few short years, their guilt started to catch up to them.

In response, Hearst traveled to Cuba to report on the atrocities of the war firsthand, giving an honest view of the country and the battle for independence they were facing. Pultizer didn’t leave the country, but he did shift the focus of his paper back to its ethical journalistic roots.

Yellow Journalism After the Spanish-American War

Once the war had ended, the influence of yellow journalism could still be seen in papers across the country, but its effects were gradually diminishing. Publications were starting to see the value of ethical journalism over yellow journalism, and how important it was to report things factually instead of relying so much on sensationalism.

The gradual shift towards more responsible reporting continued through the 20th century, with the Society of Professional Journalists being established in 1909. This society advocated for ethical journalism practices and emphasized accuracy, fairness, and integrity instead of relying on flashy, attention-grabbing pieces.

As for Hearst and Pulitzer, their rivalry also dimmed once the war was over. Hearst tried his hand at entering the political field but had little success. He faced outrage when articles published in his paper called for the assassination of President McKinley, who was later shot on September 6, 1901.

Hearst insisted that he was unaware of the articles, and the one that he was made aware of he pulled from the paper right away. Even so, critics of Hearst accused him and his yellow journalism of playing a possible part in driving the shooter, Leon Czolgosz, to act.

Pulitzer, on the other hand, spent time rebuilding the tarnished reputation of his paper until it was a respected publication instead of a tabloid-esque haven for yellow journalism. After his death, his successes and innovations in the world of journalism led Columbia to create the Pulitzer Prize awards for outstanding journalism.

Yellow Journalism in the Present Day

Even though the heyday of yellow journalism has long since passed, it lives on in many types of media today. The twenty-four-hour news cycle and the availability of the internet make it incredibly easy to access these entertainment-based types of news media.

Tabloids are the most notorious successor to yellow journalism, using scintillating headlines and paparazzi photos to garner readers’ attention. They are considered classless, and even predatory in nature, similar to how yellow journalism was viewed in the late 1800s.

Another more recent offspring of yellow journalism are clickbait articles on the internet . Almost identical to the tactics of yellow journalism, clickbait uses irresistible, often misleading titles to get internet users to click on web pages and videos. These clickbait articles or videos will often use sensationalized, edited pictures to grab attention, too.

Characteristics of Yellow Journalism

- Sensational headlines- As previously stated, attention-grabbing headlines are the cornerstone of yellow journalism. Altering the truth to fit these headlines and cause the strongest emotions was the goal. Strong emotions equal more sales.

- Emphasis on Scandal- Important issues like politics and world events sometimes seem boring compared to smaller-scale, scandalous stories. Because of this, another characteristic of yellow journalism is a focus on stories about scandal and crime over real, objective reporting on events that really matter.

- Illustrations- One of the first examples of yellow journalism was a cartoon known as “The Yellow Kid”. Keeping up with this trend, comics and illustrations often accompanied articles that utilized yellow journalism with the intention of grabbing the attention of potential customers with their bright colors and often inflammatory subjects.

- Political Influence: Since yellow journalism was often untruthful, it wasn’t unheard of for the newspapers that featured yellow journalism to have a political agenda. Publishers would use their papers to push their political opinions, writing headlines and articles that were blatantly false and passing them off as truth to try and make their preferences appear to be reality. These sorts of yellow journalism examples were especially notorious, as their existence made it difficult for the public to research politics and form their own opinion with everything being presented as fact and written with a specific agenda in mind.

References

“U.S. Diplomacy and Yellow Journalism, 1895–1898”

https://history.state.gov/milestones/1866-1898/yellow-journalism#:~:text=Yellow%20journalism%20was%20a%20style,territory%20by%20the%20United%20States.

“Yellow Journalism”

https://www.britannica.com/topic/yellow-journalism

Related Posts

The Lovers of Valdaro – A Double Burial From Neolithic Italy

Quiz: How well do you know US presidents?

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

U.S. Diplomacy and Yellow Journalism, 1895–1898

Milestones: 1866–1898.

Yellow journalism was a style of newspaper reporting that emphasized sensationalism over facts. During its heyday in the late 19th century it was one of many factors that helped push the United States and Spain into war in Cuba and the Philippines, leading to the acquisition of overseas territory by the United States.

The term originated in the competition over the New York City newspaper market between major newspaper publishers Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst . At first, yellow journalism had nothing to do with reporting, but instead derived from a popular cartoon strip about life in New York’s slums called Hogan’s Alley, drawn by Richard F. Outcault. Published in color by Pulitzer’s New York World, the comic’s most well-known character came to be known as the Yellow Kid, and his popularity accounted in no small part for a tremendous increase in sales of the World. In 1896, in an effort to boost sales of his New York Journal, Hearst hired Outcault away from Pulitzer, launching a fierce bidding war between the two publishers over the cartoonist. Hearst ultimately won this battle, but Pulitzer refused to give in and hired a new cartoonist to continue drawing the cartoon for his paper. This battle over the Yellow Kid and a greater market share gave rise to the term yellow journalism.

Once the term had been coined, it extended to the sensationalist style employed by the two publishers in their profit-driven coverage of world events, particularly developments in Cuba. Cuba had long been a Spanish colony and the revolutionary movement, which had been simmering on and off there for much of the 19th century, intensified during the 1890s. Many in the United States called upon Spain to withdraw from the island, and some even gave material support to the Cuban revolutionaries. Hearst and Pulitzer devoted more and more attention to the Cuban struggle for independence, at times accentuating the harshness of Spanish rule or the nobility of the revolutionaries, and occasionally printing rousing stories that proved to be false. This sort of coverage, complete with bold headlines and creative drawings of events, sold a lot of papers for both publishers.

The peak of yellow journalism, in terms of both intensity and influence, came in early 1898, when a U.S. battleship, the Maine, sunk in Havana harbor. The naval vessel had been sent there not long before in a display of U.S. power and, in conjunction with the planned visit of a Spanish ship to New York, an effort to defuse growing tensions between the United States and Spain. On the night of February 15, an explosion tore through the ship’s hull, and the Maine went down. Sober observers and an initial report by the colonial government of Cuba concluded that the explosion had occurred on board, but Hearst and Pulitzer, who had for several years been selling papers by fanning anti-Spanish public opinion in the United States, published rumors of plots to sink the ship. When a U.S. naval investigation later stated that the explosion had come from a mine in the harbor, the proponents of yellow journalism seized upon it and called for war. By early May, the Spanish-American War had begun .

The rise of yellow journalism helped to create a climate conducive to the outbreak of international conflict and the expansion of U.S. influence overseas, but it did not by itself cause the war. In spite of Hearst’s often quoted statement—“You furnish the pictures, I’ll provide the war!”—other factors played a greater role in leading to the outbreak of war. The papers did not create anti-Spanish sentiments out of thin air, nor did the publishers fabricate the events to which the U.S. public and politicians reacted so strongly. Moreover, influential figures such as Theodore Roosevelt led a drive for U.S. overseas expansion that had been gaining strength since the 1880s. Nevertheless, yellow journalism of this period is significant to the history of U.S. foreign relations in that its centrality to the history of the Spanish American War shows that the press had the power to capture the attention of a large readership and to influence public reaction to international events. The dramatic style of yellow journalism contributed to creating public support for the Spanish-American War, a war that would ultimately expand the global reach of the United States.

The War at Stanford

I didn’t know that college would be a factory of unreason.

Listen to this article

Produced by ElevenLabs and News Over Audio (NOA) using AI narration.

This article was featured in the One Story to Read Today newsletter. Sign up for it here .

ne of the section leaders for my computer-science class, Hamza El Boudali, believes that President Joe Biden should be killed. “I’m not calling for a civilian to do it, but I think a military should,” the 23-year-old Stanford University student told a small group of protesters last month. “I’d be happy if Biden was dead.” He thinks that Stanford is complicit in what he calls the genocide of Palestinians, and that Biden is not only complicit but responsible for it. “I’m not calling for a vigilante to do it,” he later clarified, “but I’m saying he is guilty of mass murder and should be treated in the same way that a terrorist with darker skin would be (and we all know terrorists with dark skin are typically bombed and drone striked by American planes).” El Boudali has also said that he believes that Hamas’s October 7 attack was a justifiable act of resistance, and that he would actually prefer Hamas rule America in place of its current government (though he clarified later that he “doesn’t mean Hamas is perfect”). When you ask him what his cause is, he answers: “Peace.”

I switched to a different computer-science section.

Israel is 7,500 miles away from Stanford’s campus, where I am a sophomore. But the Hamas invasion and the Israeli counterinvasion have fractured my university, a place typically less focused on geopolitics than on venture-capital funding for the latest dorm-based tech start-up. Few students would call for Biden’s head—I think—but many of the same young people who say they want peace in Gaza don’t seem to realize that they are in fact advocating for violence. Extremism has swept through classrooms and dorms, and it is becoming normal for students to be harassed and intimidated for their faith, heritage, or appearance—they have been called perpetrators of genocide for wearing kippahs, and accused of supporting terrorism for wearing keffiyehs. The extremism and anti-Semitism at Ivy League universities on the East Coast have attracted so much media and congressional attention that two Ivy presidents have lost their jobs. But few people seem to have noticed the culture war that has taken over our California campus.

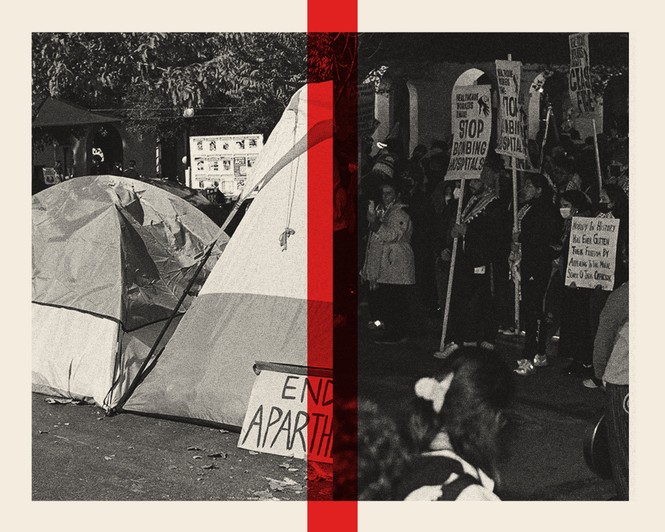

For four months, two rival groups of protesters, separated by a narrow bike path, faced off on Stanford’s palm-covered grounds. The “Sit-In to Stop Genocide” encampment was erected by students in mid-October, even before Israeli troops had crossed into Gaza, to demand that the university divest from Israel and condemn its behavior. Posters were hung equating Hamas with Ukraine and Nelson Mandela. Across from the sit-in, a rival group of pro-Israel students eventually set up the “Blue and White Tent” to provide, as one activist put it, a “safe space” to “be a proud Jew on campus.” Soon it became the center of its own cluster of tents, with photos of Hamas’s victims sitting opposite the rubble-ridden images of Gaza and a long (and incomplete) list of the names of slain Palestinians displayed by the students at the sit-in.

Some days the dueling encampments would host only a few people each, but on a sunny weekday afternoon, there could be dozens. Most of the time, the groups tolerated each other. But not always. Students on both sides were reportedly spit on and yelled at, and had their belongings destroyed. (The perpetrators in many cases seemed to be adults who weren’t affiliated with Stanford, a security guard told me.) The university put in place round-the-clock security, but when something actually happened, no one quite knew what to do.

Conor Friedersdorf: How October 7 changed America’s free speech culture

Stanford has a policy barring overnight camping, but for months didn’t enforce it, “out of a desire to support the peaceful expression of free speech in the ways that students choose to exercise that expression”—and, the administration told alumni, because the university feared that confronting the students would only make the conflict worse. When the school finally said the tents had to go last month, enormous protests against the university administration, and against Israel, followed.

“We don’t want no two states! We want all of ’48!” students chanted, a slogan advocating that Israel be dismantled and replaced by a single Arab nation. Palestinian flags flew alongside bright “Welcome!” banners left over from new-student orientation. A young woman gave a speech that seemed to capture the sense of urgency and power that so many students here feel. “We are Stanford University!” she shouted. “We control things!”

“W e’ve had protests in the past,” Richard Saller, the university’s interim president, told me in November—about the environment, and apartheid, and Vietnam. But they didn’t pit “students against each other” the way that this conflict has.

I’ve spoken with Saller, a scholar of Roman history, a few times over the past six months in my capacity as a student journalist. We first met in September, a few weeks into his tenure. His predecessor, Marc Tessier-Lavigne, had resigned as president after my reporting for The Stanford Daily exposed misconduct in his academic research. (Tessier-Lavigne had failed to retract papers with faked data over the course of 20 years. In his resignation statement , he denied allegations of fraud and misconduct; a Stanford investigation determined that he had not personally manipulated data or ordered any manipulation but that he had repeatedly “failed to decisively and forthrightly correct mistakes” from his lab.)

In that first conversation, Saller told me that everyone was “eager to move on” from the Tessier-Lavigne scandal. He was cheerful and upbeat. He knew he wasn’t staying in the job long; he hadn’t even bothered to move into the recently vacated presidential manor. In any case, campus, at that time, was serene. Then, a week later, came October 7.

The attack was as clear a litmus test as one could imagine for the Middle East conflict. Hamas insurgents raided homes and a music festival with the goal of slaughtering as many civilians as possible. Some victims were raped and mutilated, several independent investigations found. Hundreds of hostages were taken into Gaza and many have been tortured.

This, of course, was bad. Saying this was bad does not negate or marginalize the abuses and suffering Palestinians have experienced in Gaza and elsewhere. Everyone, of every ideology, should be able to say that this was bad. But much of this campus failed that simple test.

Two days after the deadliest massacre of Jews since the Holocaust, Stanford released milquetoast statements marking the “moment of intense emotion” and declaring “deep concern” over “the crisis in Israel and Palestine.” The official statements did not use the words Hamas or violence .

The absence of a clear institutional response led some teachers to take matters into their own hands. During a mandatory freshman seminar on October 10, a lecturer named Ameer Loggins tossed out his lesson plan to tell students that the actions of the Palestinian “military force” had been justified, that Israelis were colonizers, and that the Holocaust had been overemphasized, according to interviews I conducted with students in the class. Loggins then asked the Jewish students to identify themselves. He instructed one of them to “stand up, face the window, and he kind of kicked away his chair,” a witness told me. Loggins described this as an effort to demonstrate Israel’s treatment of Palestinians. (Loggins did not reply to a request for comment; a spokesperson for Stanford said that there were “different recollections of the details regarding what happened” in the class.)

“We’re only in our third week of college, and we’re afraid to be here,” three students in the class wrote in an email that night to administrators. “This isn’t what Stanford was supposed to be.” The class Loggins taught is called COLLEGE, short for “Civic, Liberal, and Global Education,” and it is billed as an effort to develop “the skills that empower and enable us to live together.”

Loggins was suspended from teaching duties and an investigation was opened; this angered pro-Palestine activists, who organized a petition that garnered more than 1,700 signatures contesting the suspension. A pamphlet from the petitioners argued that Loggins’s behavior had not been out of bounds.

The day after the class, Stanford put out a statement written by Saller and Jenny Martinez, the university provost, more forcefully condemning the Hamas attack. Immediately, this new statement generated backlash.

Pro-Palestine activists complained about it during an event held the same day, the first of several “teach-ins” about the conflict. Students gathered in one of Stanford’s dorms to “bear witness to the struggles of decolonization.” The grievances and pain shared by Palestinian students were real. They told of discrimination and violence, of frightened family members subjected to harsh conditions. But the most raucous reaction from the crowd was in response to a young woman who said, “You ask us, do we condemn Hamas? Fuck you!” She added that she was “so proud of my resistance.”

David Palumbo-Liu, a professor of comparative literature with a focus on postcolonial studies, also spoke at the teach-in, explaining to the crowd that “European settlers” had come to “replace” Palestine’s “native population.”

Palumbo-Liu is known as an intelligent and supportive professor, and is popular among students, who call him by his initials, DPL. I wanted to ask him about his involvement in the teach-in, so we met one day in a café a few hundred feet away from the tents. I asked if he could elaborate on what he’d said at the event about Palestine’s native population. He was happy to expand: This was “one of those discussions that could go on forever. Like, who is actually native? At what point does nativism lapse, right? Well, you haven’t been native for X number of years, so …” In the end, he said, “you have two people who both feel they have a claim to the land,” and “they have to live together. Both sides have to cede something.”

The struggle at Stanford, he told me, “is to find a way in which open discussions can be had that allow people to disagree.” It’s true that Stanford has utterly failed in its efforts to encourage productive dialogue. But I still found it hard to reconcile DPL’s words with his public statements on Israel, which he’d recently said on Facebook should be “the most hated nation in the world.” He also wrote: “When Zionists say they don’t feel ‘safe’ on campus, I’ve come to see that as they no longer feel immune to criticism of Israel.” He continued: “Well as the saying goes, get used to it.”

Z ionists, and indeed Jewish students of all political beliefs, have been given good reason to fear for their safety. They’ve been followed, harassed, and called derogatory racial epithets. At least one was told he was a “dirty Jew.” At least twice, mezuzahs have been ripped from students’ doors, and swastikas have been drawn in dorms. Arab and Muslim students also face alarming threats. The computer-science section leader, El Boudali, a pro-Palestine activist, told me he felt “safe personally,” but knew others who did not: “Some people have reported feeling like they’re followed, especially women who wear the hijab.”

In a remarkably short period of time, aggression and abuse have become commonplace, an accepted part of campus activism. In January, Jewish students organized an event dedicated to ameliorating anti-Semitism. It marked one of Saller’s first public appearances in the new year. Its topic seemed uncontroversial, and I thought it would generate little backlash.

Protests began before the panel discussion even started, with activists lining the stairs leading to the auditorium. During the event they drowned out the panelists, one of whom was Israel’s special envoy for combatting anti-Semitism, by demanding a cease-fire. After participants began cycling out into the dark, things got ugly.

Activists, their faces covered by keffiyehs or medical masks, confronted attendees. “Go back to Brooklyn!” a young woman shouted at Jewish students. One protester, who emerged as the leader of the group, said that she and her compatriots would “take all of your places and ensure Israel falls.” She told attendees to get “off our fucking campus” and launched into conspiracy theories about Jews being involved in “child trafficking.” As a rabbi tried to leave the event, protesters pursued him, chanting, “There is only one solution! Intifada revolution!”

At one point, some members of the group turned on a few Stanford employees, including another rabbi, an imam, and a chaplain, telling them, “We know your names and we know where you work.” The ringleader added: “And we’ll soon find out where you live.” The religious leaders formed a protective barrier in front of the Jewish students. The rabbi and the imam appeared to be crying.

S aller avoided the protest by leaving through another door. Early that morning, his private residence had been vandalized. Protesters frequently tell him he “can’t hide” and shout him down. “We charge you with genocide!” they chant, demanding that Stanford divest from Israel. (When asked whether Stanford actually invested in Israel, a spokesperson replied that, beyond small exposures from passive funds that track indexes such as the S&P 500, the university’s endowment “has no direct holdings in Israeli companies, or direct holdings in defense contractors.”)

When the university finally said the protest tents had to be removed, students responded by accusing Saller of suppressing their right to free speech. This is probably the last charge he expected to face. Saller once served as provost at the University of Chicago, which is known for holding itself to a position of strict institutional neutrality so that its students can freely explore ideas for themselves. Saller has a lifelong belief in First Amendment rights. But that conviction in impartial college governance does not align with Stanford’s behavior in recent years. Despite the fact that many students seemed largely uninterested in the headlines before this year, Stanford’s administrative leadership has often taken positions on political issues and events, such as the Paris climate conference and the murder of George Floyd. After Russia invaded Ukraine, Stanford’s Hoover Tower was lit up in blue and yellow, and the school released a statement in solidarity.

Thomas Chatterton Williams: Let the activists have their loathsome rallies

When we first met, a week before October 7, I asked Saller about this. Did Stanford have a moral duty to denounce the war in Ukraine, for example, or the ethnic cleansing of Uyghur Muslims in China? “On international political issues, no,” he said. “That’s not a responsibility for the university as a whole, as an institution.”

But when Saller tried to apply his convictions on neutrality for the first time as president, dozens of faculty members condemned the response, many pro-Israel alumni were outraged, donors had private discussions about pulling funding, and an Israeli university sent an open letter to Saller and Martinez saying, “Stanford’s administration has failed us.” The initial statement had tried to make clear that the school’s policy was not Israel-specific: It noted that the university would not take a position on the turmoil in Nagorno-Karabakh (where Armenians are undergoing ethnic cleansing) either. But the message didn’t get through.

Saller had to beat an awkward retreat or risk the exact sort of public humiliation that he, as caretaker president, had presumably been hired to avoid. He came up with a compromise that landed somewhere in the middle: an unequivocal condemnation of Hamas’s “intolerable atrocities” paired with a statement making clear that Stanford would commit to institutional neutrality going forward.

“The events in Israel and Gaza this week have affected and engaged large numbers of students on our campus in ways that many other events have not,” the statement read. “This is why we feel compelled to both address the impact of these events on our campus and to explain why our general policy of not issuing statements about news events not directly connected to campus has limited the breadth of our comments thus far, and why you should not expect frequent commentary from us in the future.”

I asked Saller why he had changed tack on Israel and not on Nagorno-Karabakh. “We don’t feel as if we should be making statements on every war crime and atrocity,” he told me. This felt like a statement in and of itself.

In making such decisions, Saller works closely with Martinez, Stanford’s provost. I happened to interview her, too, a few days before October 7, not long after she’d been appointed. When I asked about her hopes for the job, she said that a “priority is ensuring an environment in which free speech and academic freedom are preserved.”