Inside Zelensky’s World

T he nights are the hardest, when he lies there on his cot, the whine of the air-raid sirens in his ears and his phone still buzzing beside him. Its screen makes his face look like a ghost in the dark, his eyes scanning messages he didn’t have a chance to read during the day. Some from his wife and kids, many from his advisers, a few from his troops, surrounded in their bunkers, asking him again and again for more weapons to break the Russian siege.

Inside his own bunker, the President has a habit of staring at his daily agenda even when the day is over. He lies awake and wonders whether he missed something, forgot someone. “It’s pointless,” Volodymyr Zelensky told me at the presidential compound in Kyiv , just outside the office where he sometimes sleeps. “It’s the same agenda. I see it’s over for today. But I look at it several times and sense that something is wrong.” It’s not anxiety that keeps his eyes from closing. “It’s my conscience bothering me.”

The same thought keeps turning over in his head: “I’ve let myself sleep, but now what? Something is happening right now.” Somewhere in Ukraine the bombs are still falling. Civilians are still trapped in basements or under the rubble. The Russians are still committing crimes of war, rape, and torture . Their bombs are leveling entire towns. The city of Mariupol and its last defenders are besieged. A critical battle has started in the east. Amid all this, Zelensky, the comedian turned President, still needs to keep the world engaged, and to convince foreign leaders that his country needs their help right now, at any cost.

Outside Ukraine, Zelensky told me, “People see this war on Instagram, on social media. When they get sick of it, they will scroll away.” It’s human nature. Horrors have a way of making us close our eyes. “It’s a lot of blood,” he explains. “It’s a lot of emotion.” Zelensky senses the world’s attention flagging, and it troubles him nearly as much as the Russian bombs. Most nights, when he scans his agenda, his list of tasks has less to do with the war itself than with the way it is perceived. His mission is to make the free world experience this war the way Ukraine does: as a matter of its own survival.

He seems to be pulling it off. The U.S. and Europe have rushed to his aid, providing more weapons to Ukraine than they have given any other country since World War II. Thousands of journalists have come to Kyiv, filling the inboxes of his staff with interview requests.

My request was not just for a chance to question the President. It was to see the war the way he and his team have experienced it. Over two weeks in April, they allowed me to do that in the presidential compound on Bankova Street, to observe their routines and hang around the offices where they now live and work. Zelensky and his staff made the place feel almost normal. We cracked jokes, drank coffee, waited for meetings to start or end. Only the soldiers, our ever present chaperones, embodied the war as they took us around, shining flashlights down dark corridors, past the rooms where they slept on the floor.

Read More: TIME’s Interview with Volodymyr Zelensky

The experience illustrated how much Zelensky has changed since we first met three years ago, backstage at his comedy show in Kyiv, when he was still an actor running for President. His sense of humor is still intact. “It’s a means of survival,” he says. But two months of war have made him harder, quicker to anger, and a lot more comfortable with risk. Russian troops came within minutes of finding him and his family in the first hours of the war, their gunfire once audible inside his office walls. Images of dead civilians haunt him. So do the daily appeals from his troops, hundreds of whom are trapped belowground, running out of food, water, and ammunition.

This account of Zelensky at war is based on interviews with him and nearly a dozen of his aides. Most of them were thrown into this experience with no real preparation. Many of them, like Zelensky himself, come from the worlds of acting and show business. Others were known in Ukraine as bloggers and journalists before the war.

On the day we last met—the 55th of the invasion—Zelensky announced the start of a battle that could end the war. Russian forces had regrouped after sustaining heavy losses around Kyiv, and they had begun a fresh assault in the east. There, Zelensky says, the armies of one side or the other will likely be destroyed. “This will be a full-scale battle, bigger than any we have seen on the territory of Ukraine,” Zelensky told me on April 19. “If we hold out,” he says, “it will be a decisive moment for us. The tipping point.”

In the first weeks of the invasion , when the Russian artillery was within striking distance of Kyiv, Zelensky seldom waited for sunrise before calling his top general for a status report. Their first call usually took place around 5 a.m., before the light began peeking through the sandbags in the windows of the compound. Later they moved the conversation back by a couple of hours, enough time for Zelensky to have breakfast—invariably eggs— and to make his way to the presidential chambers.

This set of rooms changed little after the invasion. It remained a cocoon of gold leaf and palatial furniture that Zelensky’s staff find oppressive. (“At least if the place gets bombed,” one of them joked, “we won’t have to look at this stuff anymore.”) But the streets around the compound became a maze of checkpoints and barricades. Civilian cars cannot get close, and soldiers ask pedestrians for secret passwords that change daily, often nonsense phrases, like coffee cup suitor, that would be hard for a Russian to pronounce.

Beyond the checkpoints is the government district, known as the Triangle, which Russian forces tried to seize at the start of the invasion. When those first hours came up in our interview, Zelensky warned me the memories exist “in a fragmented way,” a disjointed set of images and sounds. Among the most vivid took place before sunrise on Feb. 24, when he and his wife Olena Zelenska went to tell their children the bombing had started, and to prepare them to flee their home. Their daughter is 17 and their son is 9, both old enough to understand they were in danger. “We woke them up,” Zelensky told me, his eyes turning inward. “It was loud. There were explosions over there.”

It soon became clear the presidential offices were not the safest place to be. The military informed Zelensky that Russian strike teams had parachuted into Kyiv to kill or capture him and his family. “Before that night, we had only ever seen such things in the movies,” says Andriy Yermak, the President’s chief of staff.

As Ukrainian troops fought the Russians back in the streets, the presidential guard tried to seal the compound with whatever they could find. A gate at the rear entrance was blocked with a pile of police barricades and plywood boards, resembling a mound of junkyard scrap more than a fortification.

Friends and allies rushed to Zelensky’s side, sometimes in violation of security protocols. Several brought their families to the compound. If the President were to be killed, the chain of succession in Ukraine calls for the Speaker of parliament to take command. But Ruslan Stefanchuk, who holds that post, drove straight to Bankova Street on the morning of the invasion rather than taking shelter at a distance.

Stefanchuk was among the first to see the President in his office that day. “It wasn’t fear on his face,” he told me. “It was a question: How could this be?” For months Zelensky had downplayed warnings from Washington that Russia was about to invade. Now he registered the fact that an all-out war had broken out, but could not yet grasp the totality of what it meant. “Maybe these words sound vague or pompous,” says Stefanchuk. “But we sensed the order of the world collapsing.” Soon the Speaker rushed down the street to the parliament and presided over a vote to impose martial law across the country. Zelensky signed the decree that afternoon.

As night fell that first evening, gunfights broke out around the government quarter. Guards inside the compound shut the lights and brought bulletproof vests and assault rifles for Zelensky and about a dozen of his aides. Only a few of them knew how to handle the weapons. One was Oleksiy Arestovych, a veteran of Ukraine’s military intelligence service. “It was an absolute madhouse,” he told me. “Automatics for everyone.” Russian troops, he says, made two attempts to storm the compound. Zelensky later told me that his wife and children were still there at the time.

Offers came in from American and British forces to evacuate the President and his team. The idea was to help them set up a government in exile, most likely in eastern Poland, that could continue to lead from afar. None of Zelensky’s advisers recall him giving these offers any serious consideration. Speaking on a secure landline with the Americans, he responded with a zinger that made headlines around the world: “I need ammunition, not a ride.”

“We thought that was brave,” says a U.S. official briefed on the call. “But very risky.” Zelensky’s bodyguards felt the same. They also urged him to leave the compound right away. Its buildings are nestled in a densely populated neighborhood, surrounded by private homes that could serve as nests for enemy snipers. Some houses are close enough to throw a grenade through the window from across the street. “The place was wide open,” says Arestovych. “We didn’t even have concrete blocks to close the street.”

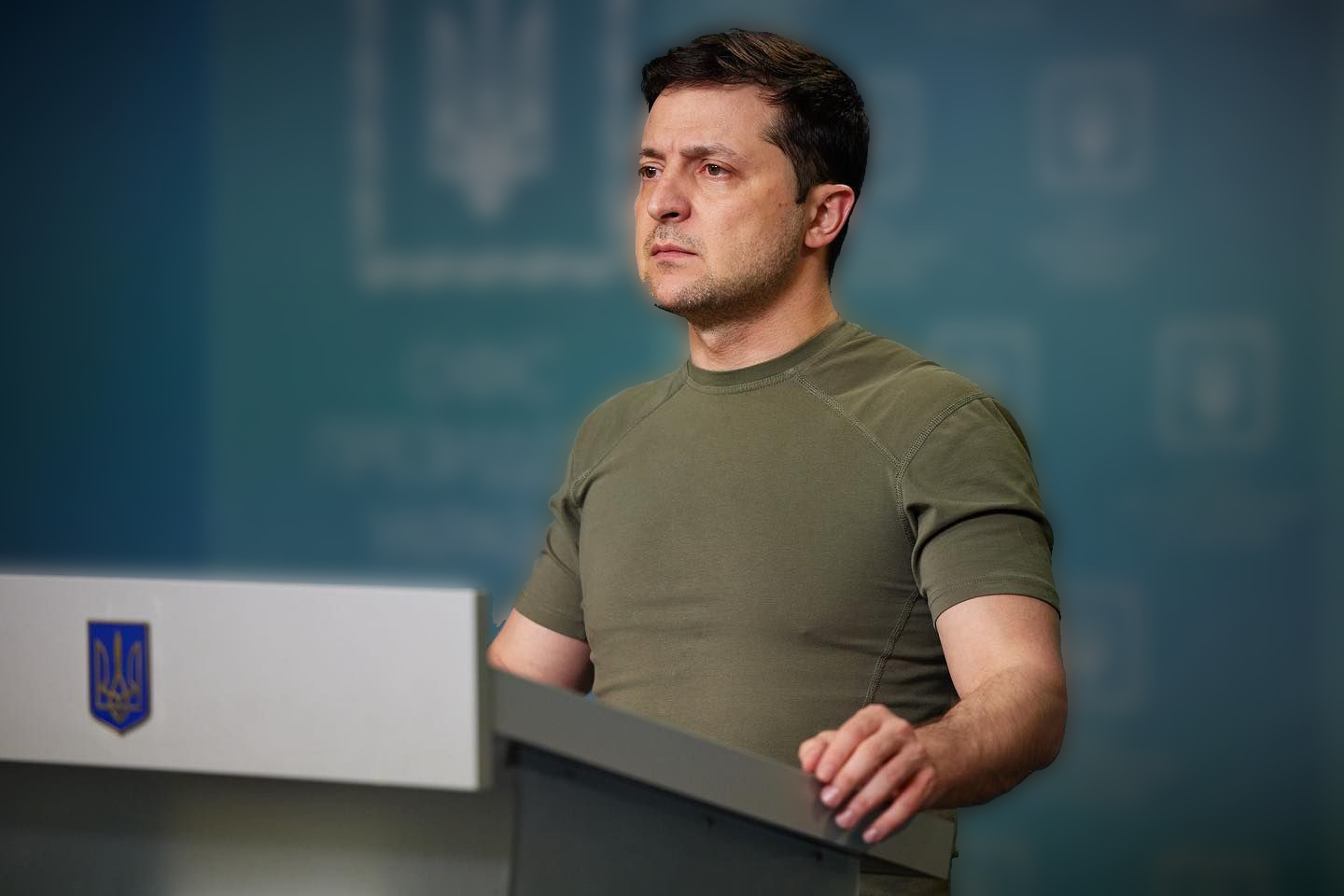

Somewhere outside the capital, a secure bunker was waiting for the President, equipped to withstand a lengthy siege. Zelensky refused to go there. Instead, on the second night of the invasion, while Ukrainian forces were fighting the Russians in nearby streets, the President decided to walk outside into the courtyard and film a video message on his phone. “We’re all here,” Zelensky said after doing a roll call of the officials by his side. They were dressed in the army green T-shirts and jackets that would become their war-time uniforms. “Defending our independence, our country.”

By then, Zelensky understood his role in this war. The eyes of his people and much of the world were fixed on him. “You understand that they’re watching,” he says. “You’re a symbol. You need to act the way the head of state must act.”

Read More: ‘Hope Gives You the Strength to Act.’ Portraits of Russians Risking Everything to Support Ukraine

When he posted the 40-second clip to Instagram on Feb. 25, the sense of unity it projected was a bit misleading. Zelensky had been alarmed by the number of officials and even military officers who had fled. He did not respond with threats or ultimatums. If they needed some time to evacuate their families, he allowed it. Then he asked them to come back to their posts. Most of them did.

Other people volunteered to live in the bunkers of the presidential compound. Serhiy Leshchenko, a prominent journalist and lawmaker, arrived a few days after the invasion to help the team counter Russian disinformation . He had to sign a nondisclosure agreement, forbidding him from sharing any details about the bunker’s design, location, or amenities. All its inhabitants are bound by this pledge of secrecy. They are not even allowed to talk about the food they eat down there.

Its isolation often forced Zelensky’s team to experience the war through their screens, somewhat like the rest of us. Footage of battles and rocket attacks tended to appear on social media before the military could brief Zelensky on these events. It was typical for the President and his staff to gather around a phone or laptop in the bunker, cursing images of devastation or cheering a drone strike on a Russian tank.

“This was a favorite,” Leshchenko told me, pulling up a clip of a Russian helicopter getting blown out of the sky. Memes and viral videos were a frequent source of levity, as were the war ballads that Ukrainians wrote, recorded and posted online. One of them went like this:

Look how our people, how all Ukraine United the world against the Russians Soon all the Russians, they’ll be gone And we’ll have peace in all the world.

It wasn’t long before Zelensky insisted on going to see the action for himself. In early March, when the Russians were still shelling Kyiv and trying to encircle the capital, the President drove out of his compound in secret, accompanied by two of his friends and a small team of bodyguards. “We made the decision to go on the fly,” says Yermak, the chief of staff. There were no cameras with them. Some of Zelensky’s closest aides only learned about the trip nearly two months later, when he brought it up during our interview.

Heading north from Bankova Street, the group went to a collapsed bridge that marked the front line at the edge of the city. It was the first time Zelensky had seen the effects of the fighting up close. He marveled at the size of a crater left by an explosion in the road. When they stopped to talk to Ukrainian troops at a checkpoint, Zelensky’s bodyguards, he says, “were losing their minds.” The President had no pressing reason to be that close to the Russian positions. He says he just wanted to have a look, and to talk to the people on the front lines.

A few days later, Zelensky went on a ride that aides refer to as “the borscht trip.” At a checkpoint near the edge of the city, the President met a man who would bring a fresh pot of borscht for the troops every day. They stood there, within range of enemy snipers and artillery, and had a bowl of soup with bread, talking about the Soviet Union and what the Russians had become since its collapse. “He told me how much he hated the Russians,” Zelensky recalls. Then the cook went to the trunk of his car and pulled out some medals he had earned while serving in the Soviet military. The conversation left a deep impression on Zelensky. “It felt right,” says Yermak. “Just talking to the people we work for.”

Such outings were rare. Though he received frequent updates from his generals and gave them broad instructions, Zelensky did not pretend to be a tactical savant. His Defense Minister was seldom by his side. Nor were any of Ukraine’s top military commanders. “He lets them do the fighting,” says Arestovych, his adviser on military affairs.

His days were a succession of statements, meetings, and interviews, usually conducted through the screen of a laptop or a phone. Courtesy calls took up time, like one Zoom session with the actors Mila Kunis and Ashton Kutcher, who had raised money for Ukraine through a GoFundMe campaign . Ahead of his nightly address to the nation, Zelensky would set out themes in conversation with his staff. “Very often people ask who is Zelensky’s speechwriter,” says Dasha Zarivna, a communications adviser. “The main one is him,” she says. “He works on every line.”

Through March and early April, Zelensky averaged about one speech per day, addressing venues as diverse as the parliament of South Korea, the World Bank, and the Grammy Awards. Each one was crafted with his audience in mind. When he spoke to the U.S. Congress, he referenced Pearl Harbor and 9/11. The German parliament heard him invoke the history of the Holocaust and the Berlin Wall.

The constant rush of urgent tasks and small emergencies had a numbing effect on the team, distending the passage of time in ways that one adviser describes as hallucinogenic. Days would feel like hours, and hours like days. The fear became acute only in the moments before sleep. “That’s when reality catches up with you,” says Leshchenko. “That’s when you lay there and think about the bombs.”

In early April , the team began emerging much more often from the bunker. The Ukrainian forces had driven the enemy back from the suburbs of Kyiv, and the Russians were moving their forces to the battle for the east. On the 40th day of the invasion, Zelensky made another trip outside the compound, this time with cameras in tow. He rode that morning in a convoy of armored vehicles to Bucha, a well-to-do commuter town where Russian troops had slaughtered hundreds of civilians .

Their bodies were left scattered around town, Zelensky said, “found in barrels, basements, strangled, tortured.” Nearly all had fatal gunshot wounds. Some had been lying in the streets for days. As Zelensky and his team saw the atrocities up close, their horror quickly turned to rage. “We wanted to call off all peace talks,” says David Arakhamia, whom Zelensky had chosen to lead negotiations with the Russians. “I could barely even look them in the face.”

On April 8, while investigators were still exhuming mass graves in Bucha , Russian missiles struck a train station in Kramatorsk , in eastern Ukraine. Thousands of women, children, and elderly people had gathered with their luggage and their pets, hoping to catch evacuation trains. The missiles killed at least 50 and injured more than a hundred others. Several children lost limbs.

Zelensky learned about the attack through a series of photos taken at the scene and forwarded to him that morning. One lingers in his mind. It showed a woman who had been beheaded by the explosion. “She was wearing these bright, memorable clothes,” he says. He could not shake the image that afternoon, when he walked into one of the most important meetings of his career. Ursula von der Leyen, the top official in the E.U., had traveled to Kyiv by train to offer Ukraine a fast track to membership. The country had been waiting for this opportunity for decades. But when the moment finally came, the President could not stop thinking about that headless woman on the ground.

As he took the podium next to von der Leyen, his face was a shade of green and his usual gift for oratory failed him. He could not even muster the presence of mind to mention the missile attack in his remarks. “It was one of those times when your arms and legs are doing one thing, but your head does not listen,” he later told me. “Because your head is there at the station, and you need to be present here.”

The visit was the first in a parade of European leaders who began coming to Kyiv in April. Smartphones were not allowed inside the compound during these visits. A large cluster of phone signals, all transmitting from one place, could allow an enemy surveillance drone to pinpoint the location of the gathering. “And then: kaboom,” one guard explained, tracing the arc of a rocket with his hand.

Zelensky and his team still spent most nights and held some meetings in bunkers underneath the compound. But the Russian retreat allowed them to work in their usual rooms, which looked a lot like they did before the war. One obvious difference was the darkness. Many of the windows were covered with sandbags. Lights were switched off to make it harder for enemy snipers. Other precautions made no apparent sense. Guards had ripped the lights out of an elevator leading up to the executive offices. A tangle of wires protruded from the holes where they had been, and Zelensky’s aides rode up and down in the dark. Nobody remembered why.

On days when I came to the compound alone, the mood was more relaxed. Custodians dusted the cabinets and put fresh lining in wastebaskets. The first time it surprised me to find the metal detector and X-ray machine unplugged at the entrance while a janitor worked around them with a mop. Later it felt normal for a tired guard to glance in my bag and let me through.

Upstairs the war began to feel far away. Mykhailo Podolyak, one of a quartet of the President’s closest advisers, declined to barricade the windows in his office. He didn’t even close the drapes. When he invited me to meet him one day in April, the room was easy to find, because his nameplate was still on the door. “We go downstairs when we hear the air-raid sirens,” he explained with a shrug, referring to the bunker. “But this is my office. I like it here.”

Such faith in Kyiv’s air defenses seems like a coping mechanism, the offspring of defiance and denial. There is no way to stop the type of hyper-sonic missiles that Russia has deployed against Ukraine. The Kinzhal—the name means dagger in Russian—can travel at more than five times the speed of sound while zigzagging to avoid interceptors. It can also carry one of Russia’s nuclear warheads. But Podolyak sees no point in dwelling on this information. “The strike is coming,” he told me. “They’ll hit us here, and it’ll all be ruins.” There was no fear in his voice as he said this. “What can we do?” he asked. “We’ve got to keep working.”

The fatalism functioned as an organizing principle. Some crude precautions—barricaded gates, bulletproof vests—had felt necessary during the war’s opening stage. Later, when there was no longer a risk of Russian commandos bursting through the doors, Zelensky’s team understood that such defenses were ultimately futile. They were facing an invader with a nuclear arsenal. They had decided not to run. What was the point of hiding?

Read More: Ukrainians Are Speaking Up About Rape as a War Crime to Ensure the World Holds Russia Accountable

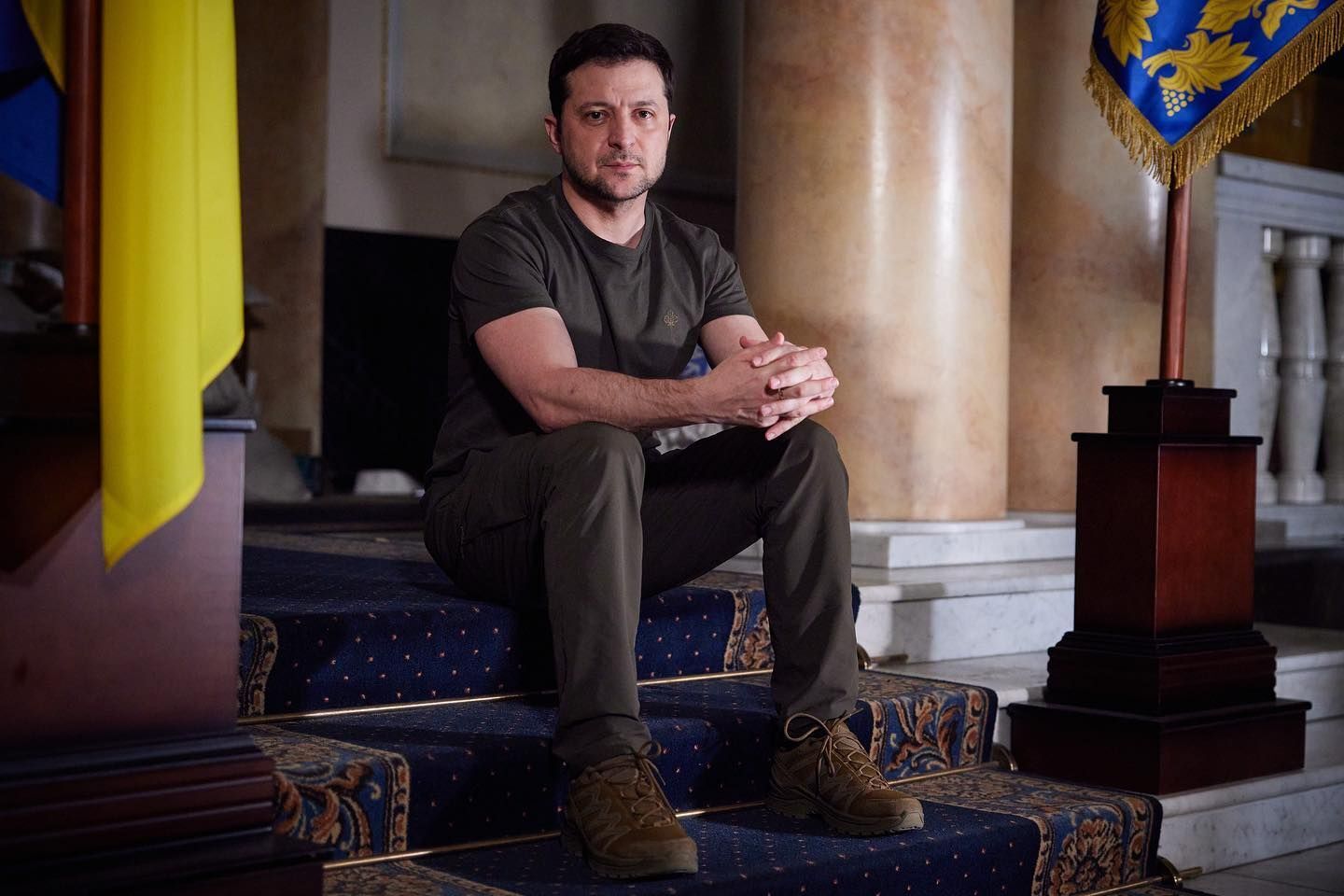

Zelensky now works most often in the compound’s Situation Room, which is neither belowground nor fortified. It is a windowless boardroom with one embellishment: a trident, the state symbol of Ukraine, glowing on the wall behind Zelensky’s chair. Large screens run along the other walls, and a camera faces the President from the center of the conference table. At around 9 a.m. on April 19, the faces of his generals and intelligence chiefs filled the screens in front of Zelensky.

Overnight, the President had given a video address to the nation, announcing the start of the battle for eastern Ukraine. Now he wanted to hear where the fighting was most intense, where his troops had retreated, who had deserted, what help they needed, and where they had managed to advance. “At certain points in the east, it’s just insane,” he told me later that day, summarizing the generals’ briefing. “Really horrible in terms of the frequency of the strikes, the heavy artillery fire, and the losses.”

For over a month, Zelensky had been texting with two Ukrainian commanders. They were the last defenders of Mariupol , a city of half a million people that the Russians encircled at the start of the invasion. A small force is still holding out inside an enormous steel factory. One of their leaders, Major Serhiy Volynsky of the 36th Separate Marine Brigade, had been in touch with Zelensky for weeks. “We know each other well by now,” Zelensky told me. Most days they call or text each other, sometimes in the middle of the night. Early on, the soldier sent the President a selfie they had taken together long before the invasion. “We’re even embracing there, like friends,” he says.

The Russian assault on Mariupol has decimated the brigade. Zelensky told me about 200 of its troops have survived. Before they found shelter and supplies inside the steel factory, they had run out of food, water, and ammunition.“They had it very hard,” Zelensky says. “We tried to support each other.”

But there was little Zelensky could do on his own. Ukraine does not have enough heavy weaponry to break through the encirclement of Mariupol. Across the east, the Russian forces have clear advantages. “They outnumber us by several times,” says Yermak.

In almost every conversation with foreign leaders, Zelensky asks for weapons that could help level the odds. Some countries, like the U.S., the U.K., and the Netherlands, have agreed to provide them. Others wavered, most critically the Germans. “With the Germans the situation is really difficult,” Zelensky says. “They are acting as though they do not want to lose their relationship with Russia.” Germany relies on Russia for a lot of its natural gas supplies . “It’s their German pragmatism,” says Zelensky. “But it costs us a lot.”

Ukraine has made its frustration clear. In the middle of April, German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier was already on his way to visit Kyiv when Zelensky’s team asked him not to come.

At times the President’s bluntness can feel like an affront, as when he told the U.N. Security Council that it should consider dissolving itself. Olaf Scholz , the German Chancellor, told me he would have appreciated if Steinmeier had been invited to Kyiv “as what he is, a friend.” But Zelensky has learned that friendly requests will not get Ukraine the weapons it needs. That is how Zelensky understands his core responsibility. Not as a military strategist empowered to move battalions around a map, but as a communicator, a living symbol of the state, whose ability to grab and hold the world’s attention will help determine whether his nation lives or dies.

His aides are keenly aware of that mission, and some give Zelensky mixed reviews. “Sometimes he slips into the role and starts to talk like an actor playing the President,” says Arestovych, who was himself a theater actor in Kyiv for many years. “I don’t think that helps us.” It is only when Zelensky is exhausted, he says, that the mask comes off. “When he is tired, he cannot act. He can only speak his mind,” Arestovych told me. “When he is himself, he makes the greatest impression as a man of integrity and humanity.”

Perhaps it was lucky for me to meet the President toward the end of a very long day. Nearly two months into the invasion, he had changed. There were new creases in his face, and he no longer searched the room for his advisers when considering an answer to a question. “I’ve gotten older,” he admitted. “I’ve aged from all this wisdom that I never wanted. It’s the wisdom tied to the number of people who have died, and the torture the Russian soldiers perpetrated. That kind of wisdom,” he added, trailing off. “To be honest, I never had the goal of attaining knowledge like that.”

It made me wonder whether he regretted the choice he made three years ago, around the time we first met. His comedy show had been a hit. Standing in his dressing room, he was still glowing from the admiration of the crowd. Friends waited backstage to start the after-party. Fans gathered outside to take a picture with him. This was just three months into his run for the presidency, when it was not too late for Zelensky to turn back.

But he does not regret the choice he made, not even with the hindsight of the war. “Not for a second,” he told me in the presidential compound. He doesn’t know how the war will end, or how history will describe his place in it. In this moment, he only knows Ukraine needs a wartime President. And that is the role he intends to play.

— With reporting by Nik Poli/ Washington and Simmone Shah/ New York

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

- Work & Careers

- Life & Arts

FT Person of the Year: Volodymyr Zelenskyy. ‘I am more responsible than brave’

- FT Person of the Year: Volodymyr Zelenskyy. ‘I am more responsible than brave’ on x (opens in a new window)

- FT Person of the Year: Volodymyr Zelenskyy. ‘I am more responsible than brave’ on facebook (opens in a new window)

- FT Person of the Year: Volodymyr Zelenskyy. ‘I am more responsible than brave’ on linkedin (opens in a new window)

- FT Person of the Year: Volodymyr Zelenskyy. ‘I am more responsible than brave’ on whatsapp (opens in a new window)

Roula Khalaf , Christopher Miller and Ben Hall in Kyiv

Simply sign up to the War in Ukraine myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Nine months into a brutal struggle for national survival against Russian invaders, Volodymyr Zelenskyy looks tired, with dark circles under his eyes. What he would like to be doing instead of confronting a merciless invader is fishing with his son. “I just want to catch a carp in the Dnipro river,” he says.

For a taste of normal life, the unlikely president may still have a long wait, despite the surprising streak of battlefield successes for Ukraine’s forces. But the folksy message is characteristic of a leader who still depicts himself as an everyman with humble tastes and a deep sense of humanity, qualities that have earned him the admiration of Ukrainians and their supporters abroad.

It is the mirror image of the fictional ordinary-guy-turned-president he played in a satirical hit television series that skyrocketed him to fame. It is also the antithesis of Russian president Vladimir Putin, hidden away in the Kremlin, whose obsession with rebuilding an empire has cost tens, possibly hundreds, of thousands of lives.

Written off by many Ukrainians before the February invasion as something of a joke, an amateur struggling to rise to the challenge of high office, the 44-year-old Zelenskyy has earned a place in history for his extraordinary display of leadership and fortitude.

Ukraine surprised the world by fending off the Russian assault on Kyiv and with its counteroffensives in Kharkiv and Kherson provinces. It has retaken half of the territory Moscow’s troops had seized this year. Zelenskyy’s forces now are pressing ahead in the south and the east, even as winter sets in, with the goal of liberating all Ukrainian territory, including the Donbas region and Crimea.

Just as Winston Churchill went on the radio to rally his country during the Blitz, Zelenskyy has used social media to campaign relentlessly for western military and financial support, turning the plight of his people into moral leverage over leaders in Europe and the US. He has persuaded Europeans to bear the huge costs of standing up to Putin and to offer Kyiv a path to EU membership.

Along the way, he has become a standard bearer for liberal democracy in the wider global contest with authoritarianism that could define the course of the 21st century.

Zelenskyy has also come to embody the courage and resilience of the Ukrainian people in their fight against Russian aggression. It is for these reasons that the Financial Times has chosen Zelenskyy as the person of the year.

In an interview with the FT, Zelenskyy recalls the early days of the invasion and says he is not really courageous: “I am more responsible than I am brave . . . I just hate to let people down.”

Zelenskyy’s powerful chief of staff, Andriy Yermak, recalls how three years ago he told a group of western journalists that “our president would be the most famous and strongest leader of his time”. He adds: “I won’t say I told you so, but I was right.”

A close call

Zelenskyy’s decision to remain in Kyiv at the start of the invasion rather than accept a US offer of evacuation was one of the most consequential moments in the war, galvanising Ukraine’s military and its people to resist. It was a surprise to Ukrainians and western allies, who had low expectations of the country’s political leaders.

For days before the invasion, Zelenskyy seemed in denial about the prospect of an all-out Russian assault on his country. “I’m the president of Ukraine and I’m based here and I think I know the details better here,” he told reporters after speaking to US President Joe Biden.

When the invasion started 10 days later, it was unclear whether Zelenskyy would survive the day. He was asleep beside his wife, Olena Zelenska, at the presidential palace in Kyiv as the first missiles struck and Russian tanks streamed across the border. Russia, the president would later say, had marked him “target number one” and his family “target number two”.

While Olena and their children were evacuated to an undisclosed location, the president was moved with staff and bodyguards into an underground bunker in the palace. Soon after, Russian special forces were parachuted in. Local collaborators who had infiltrated the ranks of the Ukrainian security service and quietly moved into safe houses close to the government quarter attempted to storm his office. They were unsuccessful, but it was a close call.

You are seeing a snapshot of an interactive graphic. This is most likely due to being offline or JavaScript being disabled in your browser.

EU leaders were horrified when Zelenskyy told them by video link that it might be the last time they saw him alive. But later that night Zelenskyy, standing out in the open near the presidential office and flanked by his closest advisers, sent a message by video selfie that millions of Ukrainians had wanted to hear: “The president is here. We are all here. Our soldiers are here.”

Nine months later, Russian forces are long gone from Kyiv — although they continue to menace the capital with weekly missile strikes against the power network, plunging millions into darkness. At the presidential palace, no one is taking chances: sandbagged shooting positions are placed along the corridors as if Russian special forces could again storm the building.

Life imitates art

Zelenskyy was born into a Ukrainian-Jewish family in Kryvyi Rih, a steelmaking city in south-central Ukraine. In the post-Soviet 1990s it was a rough-and-tumble type of place where a youngster like Zelenskyy had to make his own luck, but his upbringing was relatively comfortable. His mother is an engineer and his father a computer science professor. He was the teachers’ pet in school, he said, because he was very dependable and funny. “Everybody loved me. I was the energy of every group,” he says.

Zelenskyy met Olena in school and they grew close at university, where he studied law and she studied architecture. They went on to form a wildly successful comedy troupe and production company. Named after the district where they grew up, Kvartal 95, it toured Ukraine and Russia, before producing a hit TV series that launched Zelenskyy’s career in politics.

He announced his presidential run on New Year’s Eve in 2018, with an anti-establishment and anti-corruption platform strikingly similar to that of the character he played on TV. Less than four months later, he defeated incumbent Petro Poroshenko by a landslide, winning 73 per cent of the vote.

The political novice inherited a country that had been at war with Russia since it first invaded in 2014 and he vowed to bring peace. Ukrainians, tired of Poroshenko’s broken promises and militant attitude, saw Zelenskyy, a native Russian speaker supposedly viewed more positively in Moscow, as someone who just might be able to hammer out a deal to end the bloodshed. Putin, it turned out, was not open to any compromise.

On other fronts, Zelenskyy’s record during the first two and half years of his presidency was mixed at best. He passed important reforms, including on land sales, but made little headway in tackling corruption or reducing the influence of Ukraine’s oligarchs.

He governed via a small clique of trusted but often ill-qualified lieutenants, many of them longtime friends or associates from his showbusiness career. “There’s a lot of strange people around him, a lot of strange decisions,” says a former member of his government.

Some accused Zelenskyy of an authoritarian streak. He fired officials for failing to produce instant results. An anti-oligarch law passed in 2021, although perhaps well intentioned, in effect gave the president arbitrary powers for pursuing personal or political vendettas. His attempt to have his predecessor Poroshenko, a confectionery magnate, prosecuted for treason was denounced by western capitals.

Even some of Zelenskyy’s staff admit he can be thin-skinned. He himself says one thing he has learnt since February is “don’t be offended by the small things”. Diplomats who have followed his presidency say he distrusts western motives and still fears betrayal.

‘Fate has chosen us’

Doubts about Zelenskyy’s suitability to lead his nation in war dissipated with Russia’s attack. The president appeared to step into a new role — along with new khaki garb.

Iuliia Mendel, who served as Zelenskyy’s press secretary, says he lacked the experience and discipline to be a great peacetime leader but was better suited to lead during the tumult of war. “He is a person of chaos,” she says. “In war, it is chaos. He feels at home.”

Ruslan Stefanchuk, speaker of the Ukrainian parliament and a close political ally, noted the change at the first meeting of the National Security and Defence Council on February 24. “He was in a very, very, I would say, combative mood. And he said, look, history has chosen us. Fate has chosen us. And now we have to live up to that.”

It was not just the military that needed to mobilise but the entire state. Zelenskyy streamlined decision-making between his office, government and parliament. He also learnt to make decisions swiftly, identifying it as the key to success, and to delegate tasks, trusting others to carry them out. Operational decisions were left to military commanders, allowing forces the flexibility to react quickly to conditions on the battlefield.

But it is Zelenskyy’s never-ending communications that have been most remarkable. His nightly video messages and Telegram posts have been a tonic for a weary population. A message directed at Moscow in September — “Without light or without you? Without you” — turned into a social media rallying cry for many Ukrainians.

Zelenskyy has addressed countless parliaments, conferences and events — from the Grammy Awards to the Glastonbury Festival. Each time he has tailored the message to the audience, often appealing to the hearts and minds of the people over their governments. He has used his pulpit to press — and sometimes shame — governments into providing vast quantities of weapons.

In a speech to the Bundestag in March, he skewered German leaders for putting their economic interests before security, saying they were adding stones to the new Berlin Wall that Russia was building across Europe. Western officials on occasion found that agreements discussed in private were immediately relayed on social media by the president or his staff, giving partners no room to back out.

His communication has rarely gone awry, although it has grated with some allies. One exception to Zelenskyy’s sure-footed messaging was his insistence that a missile strike that killed two people in Poland on November 15 was Russia’s doing. Although Polish and US officials said it was likely to have been a stray Ukrainian anti-aircraft rocket, Zelenskyy called it a “very significant escalation” that required an allied response — putting him at odds with Washington, Warsaw and other European capitals anxious not to get sucked into the war.

A peacetime leader?

Ukraine’s torment is far from over. Evicting Russian troops from the Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions in the south will be difficult enough, let alone from the well-defended positions in Donetsk, Luhansk and Crimea, areas occupied for eight years.

Nonetheless, Ukrainians are already debating whether their leader, like his illustrious British predecessor, may be the right man for a war of national survival but the wrong one for the peace that follows.

Victory will not only belong to Ukraine’s president. Some Ukrainians are making a name for themselves in the war and have political ambitions. The astonishing mobilisation of Ukrainian civil society since February can be expected to make the country more demanding of its leaders.

When the fighting eventually comes to an end, Zelenskyy will face tough questions about the failure to sufficiently prepare Ukraine for a full-blown invasion. The security services did not lay mines or blow up bridges along Russia’s lines of attack from the north and south, leading large swaths of territory to be captured quickly and easily by Putin’s troops.

Zelenskyy says that despite the public warnings by western officials, Kyiv was never given intelligence it could act on about the impending Russian attack.

“Nobody showed us specific material saying it would come from this or that direction,” he says.

Zelenskyy repeatedly attempted to call Putin in the run-up to the invasion. He wanted to tell him it would be a “great mistake, a great tragedy” but the Russian leader would not take his calls. “We are fighting against insane people,” says Zelenskyy of the Russian leadership. He is adamant that Ukraine must liberate all of its territories from Russian occupation, otherwise the war will simply resume at a later date.

But the success of Ukraine’s counteroffensives will hinge on the amount of advanced weaponry its supporters and, above all, the US are willing to supply.

The interests of Kyiv and the west could diverge. Death, destruction and anger over Russian war crimes have hardened Ukrainian public opinion against compromises with Moscow. Some allies fear a Ukrainian attempt to retake Crimea could lead to a dangerous escalation by Putin, possibly with nuclear weapons.

Already there are faint calls for negotiating with Russia, appeals that Zelenskyy rejects. “The world is not a doctor with extensive experience, it is not Putin’s doctor, and Putin is not a patient of this world.”

Despite the “absolute evil” of Russia’s war, the former comic actor still finds moments for humour, just as millions of Ukrainians find succour by sharing memes and jokes about their Russian attackers on social media. “If you don’t sometimes smile because of these people you enter a depression, and you can’t make decisions when in a depression,” he says.

Last week, Russian missile strikes left millions of Ukrainians and swaths of the country, including the capital, without running water for more than 24 hours after power was cut. The president’s office was no exception. Zelenskyy recalls with a chuckle how a visitor to his office had asked to borrow his toilet. “I refused. I said: ‘I know what it will be like in several hours.’ It was very funny.”

Promoted Content

Follow the topics in this article.

- War in Ukraine Add to myFT

- Volodymyr Zelenskyy Add to myFT

- The Big Read Add to myFT

- Christopher Miller Add to myFT

- Roula Khalaf Add to myFT

International Edition

- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- Personal Finance

- AP Investigations

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- AP Buyline Shopping

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Election Results

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- Auto Racing

- 2024 Paris Olympic Games

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Personal finance

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

Zelenskyy’s unlikely journey, from comedy to wartime leader

FILE - Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy speaks during a media conference at an Eastern Partnership Summit in Brussels, Dec. 15, 2021. (Johanna Geron/ Pool Photo via AP, File)

FILE - Russian President Vladimir Putin, right, and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy arrive for a working session at the Elysee Palace, Dec. 9, 2019, in Paris. (Ian Langsdon/Pool via AP, File)

FILE - Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy surrounded by servicemen as he visits the war-hit Donetsk region, eastern Ukraine, on Oct. 14, 2021. (Ukrainian Presidential Press Office via AP, File)

In this photo provided by the Ukrainian Presidential Press Office, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy speaks to the nation via his phone in the center of Kyiv, Ukraine, Saturday, Feb. 26, 2022. Russian troops stormed toward Ukraine’s capital Saturday, and street fighting broke out as city officials urged residents to take shelter. The country’s president refused an American offer to evacuate, insisting that he would stay. “The fight is here,” he said. (Ukrainian Presidential Press Office via AP)

Ukrainian comedian and presidential candidate Volodymyr Zelenskyy performs during a show in Brovary, near Kiev, Ukraine on March 29, 2019. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti, File)

FILE - Ukrainian comedian and presidential candidate Volodymyr Zelenskyy, left, is surrounded by journalists after voting at a polling station, during the presidential elections in Kiev, Ukraine, March. 31, 2019. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti, File)

FILE - Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy takes a selfie at the first congress of his party called Servant of the People in the city Botanical Garden, Kiev, Ukraine, June 9, 2019. (AP Photo/Zoya Shu, File)

FILE - Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy attends a talk with journalists in Kyiv, Ukraine on Oct. 10, 2019. (AP Photo/Efrem Lukatsky, File)

FILE - Ukrainian comedian and presidential candidate Volodymyr Zelenskiy, center, and his wife Olena Zelenska celebrate a victory with their supporters at his headquarters after the second round of presidential elections in Kiev, Ukraine, April 21, 2019. (AP Photo/Sergei Grits, File)

FILE - In this undated file photo provided by the Ukrainian Presidential Press Office, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy looks at a front-line position from a shelter as he visits eastern Ukraine, where the country’s military has been locked in a conflict with Russia-backed separatists. (Ukrainian Presidential Press Office via AP, File)

- Copy Link copied

WARSAW, Poland (AP) — When Volodymyr Zelenskyy was growing up in southeastern Ukraine, his Jewish family spoke Russian and his father once forbade the younger Zelenskyy from going abroad to study in Israel. Instead, Zelenskyy studied law at home. Upon graduation, he found a new home in movie acting and comedy — rocketing in the 2010s to become one of Ukraine’s top entertainers with the TV series “Servant of the People.”

In it, he portrayed a lovable high school teacher fed up with corrupt politicians who accidentally becomes president.

Fast forward just a few years, and Zelenskyy is the president of Ukraine for real. At times in the runup to the Russian invasion, the comedian-turned-statesman had seemed inconsistent, berating the West for fearmongering one day, and for not doing enough the next. But his bravery and refusal to leave as rockets have rained down on the capital have also made him an unlikely hero to many around the world.

With courage, good humor and grace under fire that has rallied his people and impressed his Western counterparts, the compact, dark-haired, 44-year-old former actor has stayed even though he says he has a target on his back from the Russian invaders.

After an offer from the United States to transport him to safety, Zelenskyy shot back on Saturday: “I need ammunition, not a ride,” he said in Ukrainian, according to a senior American intelligence official with direct knowledge of the conversation.

Russian forces on Saturday were encircling Kyiv in the third day of the war. The chief objective, say military observers, is to reach the capital to depose Zelenskyy and his government and install someone more compliant to Russian President Vladimir Putin.

The boldness of Zelenskyy’s stand for Ukraine’s sovereignty might not have been expected from a man whose biggest political liability for many years was the feeling that he was too apt to seek compromise with Moscow. He ran for office in part on a platform that he could negotiate peace with Russia, which had seized Crimea from Ukraine and propped up two pro-Russian separatist regions in 2014, leading to a frozen conflict that had killed an estimated 15,000.

Although Zelenskyy managed a prisoner exchange, the efforts for reconciliation faltered as Putin’s insistence that Ukraine back away from the West became ever more intense, painting the Kyiv government as a nest of extremism run by Washington.

Zelenskyy has used his own history to demonstrate that his is a country of possibility, not the hate-filled polity of Putin’s imagination.

In spite of Ukraine’s dark history of antisemitism, reaching back centuries to Cossack pogroms and the collaboration of some anti-Soviet nationalists with Nazi genocide during World War II, Ukraine after Zelenskyy’s election in 2019 became the only country outside of Israel with both a president and prime minister who were Jewish. (Zelenskyy’s grandfather fought in the Soviet Army against the Nazis, while other family died in the Holocaust.)

Like his TV character, Zelenskyy came to office in a landslide democratic election, defeating a billionaire businessman. He promised to break the power of corrupt oligarchs who haphazardly controlled Ukraine since the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

That this fresh-faced upstart, campaigning primarily on social media, could come out of nowhere to claim the country’s top office likely was disturbing to Putin, who has slowly tamed and corralled his own political opposition in Russia.

Putin’s leading political rival, Alexei Navalny, also a comedic, anti-corruption crusader, was poisoned by Russian secret services in 2020 with a nerve agent applied to his underwear. He was fighting for his life when he was allowed under international diplomatic pressure to leave for Germany for medical treatment, and when doctors there saved him, he chose to go back to Russia despite certain risk.

Navalny, now in a Russian prison, has denounced Putin’s military operation in Ukraine.

Both Zelenskyy and Navalny seem to share a perspective that they must face the consequences of their beliefs, no matter what.

“It’s a frightening experience when you come to visit the president of a neighboring country, your colleague, to support him in a difficult situation, (and) you hear from him that you may never meet him again because he is staying there and will defend his country to the last,” Polish President Andrzej Duda said Friday.

He spent time with Zelenskyy on Wednesday just before the fighting started, one of many political leaders who have met with the Ukrainian president over the past month, including U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris.

Zelenskyy first came to the attention of many Americans during the administration of President Donald Trump, who in a phone call with Zelenskyy in 2019 leaned on him to dig up dirt on then presidential candidate Biden and his son Hunter that could aid Trump’s re-election campaign. That “perfect” phone call, as Trump later called it, resulted in Trump’s impeachment by the House of Representatives on charges of using his office, and the threat of withholding $400 million in authorized military support for Ukraine, for personal political gain.

Zelenskyy refused to criticize Trump’s call, saying he did not want to get involved in another country’s politics.

Putin’s attack, which the Russian president has termed a “special military operation,” began early Thursday. Putin denied for months that he had any intent to invade, and accused Biden of stirring up war hysteria when Biden revealed the numbers of Russian troops and weapons that had been deployed along Ukraine’s borders with Russia and Belarus — surrounding Ukraine on three sides.

Putin justified the attack by saying it was to defend two breakaway districts in eastern Ukraine from “genocide.”

With Russian media presenting such a picture of his country, Zelenskyy recorded a message to Russians to refute the notion that Ukraine is the aggressor and that he is any kind of warmonger: “They told you I ordered an offensive on the Donbas, to shoot, to bomb, that there’s no question about it. But there are questions, and very simple ones. To shoot whom, to bomb what? Donetsk?”

Recounting his many visits and friends in the region — “I’ve seen the faces, the eyes” — he said, “It’s our land, it’s our history. What are we going to fight over, and with whom?”

Unshaven and in olive green khaki shirts, he has taped other messages to his compatriots on the internet in the last few days to bolster morale and to emphasize that he is going nowhere, but will stay to defend Ukraine. “We are here. Honor to Ukraine,” he declares.

In the runup to the Russian invasion, Zelenskyy was critical of President Joe Biden’s open and detailed warnings about Putin’s intentions, saying they were premature and could cause panic. Then after the war began, he has criticized Washington for not doing more to protect Ukraine, including defending it militarily or accelerating its bid to join NATO.

Zelenskyy and his wife, Olena, an architect, have a 17-year-old daughter and 9-year-old son. He said this week that they remained in Ukraine, not joining the exodus of mainly women and children refugees seeking safety abroad.

“The war has transformed the former comedian from a provincial politician with delusions of grandeur into a bona fide statesman,” wrote Melinda Haring of the Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center for Foreign Affairs on Friday.

Though he can be faulted for not carrying out political reforms quickly enough and for dragging his feet on hardening Ukraine’s long border with Russia over the last year, Haring said, Zelenskyy “has shown a stiff upper lip. He has demonstrated enormous physical courage, refusing to sit in a bunker but instead traveling openly with soldiers, and an unwavering patriotism that few expected from a Russian speaker from eastern Ukraine.”

“To his great credit, he has been unmovable.”

Associated Press writer Monika Scislowska contributed to this report from Warsaw.

Who is Volodymyr Zelenskyy? The past, present and future of the Ukrainian president

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy met with President Joe Biden in December 2022 in the U.S., marking his first trip outside of Ukraine since Russia began its invasion of the country in February.

Biden invited Zelenskyy to address Congress to reinforce the U.S. “stands with Ukraine for as long as it takes.” Zelenskyy has entered the international eye largely since the war began and is TIME Magazine's Person of the Year 2022 .

Here’s what you need to know about the Ukrainian leader:

Sunflowers for Ukraine: NYC fabric flowers highlight war, refugees

War in Ukraine: Plotting the locations of 'one of the biggest rocket attacks' Russia has unleashed

Who is Volodymyr Zelenskyy?

Zelenskyy is the sixth President of Ukraine, elected in April 2019. The 44-year-old unseated incumbent Petro Poroshenko with 73% of the vote. Poroshenko had been in office since 2014.

Since Russia invaded in February 2022, Zelenskyy has been the face of Ukrainian resistance, notably for his visibility online and his pleas to other countries for support. When Russian state media began spreading misinformation that Zelenskyy had fled Kyiv, Zelenskyy filmed himself in the streets of the capital saying that he would not leave Ukraine. He also declined the U.S. invitation to help him evacuate the city, saying “The fight is here; I need ammunition, not a ride.”

- Zelenskyy was born in southern Ukraine in 1978 and is fluent in Russian, Ukrainian and English. He relocated to Mongolia with his family as a child before returning to Ukraine and entering school.

- Zelenskyy graduated with a law degree from Kyiv National Economic University, but became active in theater as a student and would later pursue that rather than law.

- Zelenskyy's grandfather, Semyon Ivanovich Zelenskyy, fought for the Soviet Union during World War II. Zelenskyy, who is Jewish, had family members who were killed by Nazi Germany during the Holocaust.

Shortly before his inauguration in 2019, Zelenskyy visited the grave of his grandfather in his hometown of Kryvy Rih on May 9 in what he called his family's "Thanksgiving," also known as Victory Day: the anniversary of the day Nazi Germany surrendered.

"Thanksgiving for the fact that the inhuman ideology of Nazism is a thing of the past, thanksgiving to those who fought against Nazism – and won, thanksgiving everyone for the opportunity to be born and live," he wrote in a Facebook post . "No one has the right to privatize this victory, to say that it could have happened without Ukrainians. We remember those who had lost their lives. And we honor those who are still alive, there are very few of them left."

Before he was President, Zelenskyy was an actor and comedian

Zelenskyy’s career in entertainment includes comedy, acting, screenwriting, producing and directing roles. In 2003, he founded production company Studio Kvartal 95 with school friends. Kvartal 95 produces films, cartoons and comedy shows, including “Servant of the People,” perhaps Zelenskyy’s most well-known role other than the highest seat in Ukraine.

In “Servant of the People,” which ran from 2015-2019, Zelenskyy plays a Ukrainian high school teacher whose tirade against government corruption goes viral and lands him as president of Ukraine.

It was this show that served as Zelenskyy’s path forward into the presidency — the show was a hit and Kvartal 95 registered Servant of the People as a political party in Ukraine in 2018 to promote Zelenskyy’s campaign. Servant of the People follows a “Ukrainian centrism” approach when it comes to ideology, rather than nationalism, communism or neoliberalism, Kyiv Post reports.

Zelenskyy and the United States

It was a conversation between former President Donald trump and Zelenskyy that led to the House filing an impeachment inquiry against Trump in 2019.

In August 2019, an unnamed official in the intelligence community filed a complaint saying Trump had a phone call with Zelenskyy. In the call, Trump urged the Ukrainian president to investigate Burisma Group, a Ukrainian energy company for which President Joe Biden's son Hunter had served on the board of directors, as his administration was holding up millions of dollars in military aid for Ukraine approved by Congress.

After Trump was acquitted, Zelenskyy pushed back on Trump's claims that Ukraine was a corrupt country.

Most of the Biden administration's relations with Ukraine have been concerning the Russian invasion. In 2021, Zelenskyy appealed to Biden to let Ukraine join NATO. Despite a long standing intention to join, Ukraine is still not a NATO member but is a NATO partner country.

Zelenskyy's visit to the U.S. marks the 300th day since Russian invasion. The U.S. has provided about $68 billion in military, economic and humanitarian assistance to Ukraine and lawmakers are about to vote on an additional $45 billion in emergency assistance.

Biden and Zelenskyy are scheduled to hold a joint press conference Wednesday, and the U.S. president is expected to commit $2 billion in additional U.S. security assistance to Ukraine amid Russian missile and drone bombing.

What is NATO?: History, facts, members and why it was created

Russian strike: 60 missiles launched into four Ukraine cities

Who is Zelenskyy’s wife?

Ukrainian first lady Olena Zelenska is a longtime comedy writer. She was born to an engineer and professor and was in junior high school when Ukraine gained independence in 1991. She and Zelenskyy — last names are gendered in Ukrainian — met in high school and started dating in university, she told Vogue.

Zelenska graduated with a degree in architecture but, like her husband, wanted to pursue satirical comedy. Zelenska helped found Kvartal 95.

Zelenska traveled to the U.S. to appeal to Congress in July, asking for the U.S. to stand with Ukraine and provide more weapons to protect the country. She also thanked the U.S. for the billions of dollars already committed to aiding Ukraine.

"You help us and your help is very strong," Zelenska said. "While Russia kills, America saves, and you should know about it. We thank you for that."

In an interview with NBC News, Zelenska noted the toll the Russian invasion has taken on children.

“Before the war, my son used to go to the folk dance ensemble. He played piano. He learned English. He of course attended sports club,” Zelenska said through a translator . “And now, I cannot bring him back to doing arts and humanities. The only thing he wants to do is martial arts and how to use a rifle.”

The pair share two children, Kyryrlo, 9, and Oleksandra, 18.

Contributing: Jordan Mendoza

- The war in Ukraine: Plotting the locations of 'one of the biggest rocket attacks' Russia has unleashed on Ukraine

- Christmas in Ukraine: Retired military couple helps remove bombs in war-torn country

- 82,000 Ukrainians living in US: "U4U" program allows Ukrainians to stay in the U.S. for two years.

- Person of Year: Volodymyr Zelenskyy and the spirit of Ukraine named Time's 2022 Person of the Year

- The war in Ukraine: A visual breakdown of Russian military bases set ablaze by drone strikes

3 years ago Zelenskyy was a TV comedian. Now he’s standing up to Putin’s army.

Three years ago, he was playing a president in a popular television comedy. Today, he is Ukraine’s president, confronting Russia’s fearsome military might .

Volodymyr Zelenskyy is leading his country during an invasion that threatens to explode into the worst conflict in Europe’s post-World War II history.

On Friday, as Russian troops reached Kyiv , he posted a defiant handheld video to social media showing him next to the presidential palace in the heart of the Ukrainian capital, surrounded by members of his Cabinet.

“We are all here,” he said. “We are defending our independence, our country.”

The message capped a head-spinning transformation of a man whose job used to be making jokes on television into a wartime leader. Who is this man at the helm as Ukraine faces the gravest of challenges?

Zelenskyy, 44, who was elected president in 2019, was educated as a lawyer, but found his true calling as an entertainer.

Married to Olena Zelenska, with whom he has two children, he was born in the central Ukrainian city of Kryvyi Rih in the then-Soviet Union to Jewish parents.

His family’s story tracks his homeland’s and the continent’s bloody history: He has said three of his grandfather’s brothers were killed by Nazi occupiers, while his grandfather survived WWII.

Raised during communism, Zelenskyy went into politics months before the 2019 election with no prior experience or solid policies. Instead, he ran on a promise to inject integrity into his country’s leadership.

Unlike many of his counterparts in the region, his past did not turn him into a dour politician in the Soviet mold. On the contrary, his public persona is encapsulated by one of his best-known quips: “You don’t need experience to be president. You just need to be a decent human being.”

As a product of the entertainment industry, he is known for his personable style and his ability to speak to people of all kinds.

“He is quite empathetic as a person. He finds good connections with people,” said Orysia Lutsevych, a research fellow at the London think tank Chatham House. “That’s why he’s successful in politics.”

A native Russian speaker, Zelenskyy used his charisma and immense popularity to win a landslide victory , supported by voters in Ukraine’s south and east — where millions of Russian-speaking Ukrainians felt disenfranchised by previous administrations. It is this alienation that Russia has tried to capitalize on by supporting separatists who have been fighting Ukrainian forces for eight years.

This week’s invasion, which came after months of Russia massing troops on Ukraine’s borders and demands from President Vladimir Putin that NATO bar Ukraine from joining the military alliance, is not the first time Zelenskyy has been thrust into the spotlight.

Just months into his presidency, a phone conversation in which then-President Donald Trump pressed him to investigate corruption allegations against Joe Biden garnered international attention. The scandal led to the first impeachment of Trump, who was acquitted in early 2020.

By this time, Zelenskyy had already disrupted the Ukrainian political system, bringing into the government people who wanted to modernize the country, Lutsevych said.

He tried to rein in Ukraine’s rampant corruption and disrupt the existing pillars of power, but “didn’t muster enough political power to crack the bone of Ukrainian corruption within the system,” she added.

At the same time, he’s been praised by many in Ukraine for keeping the country of 44 million firmly on a pro-Western path. Russia and Ukraine stayed aligned after the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991, but began drifting apart in the 2000s as Kyiv sought deeper integration with Europe.

In 2014, pro-Kremlin President Viktor Yanukovych was swept from power after refusing to sign an association agreement with the European Union.

The mere fact that Ukraine is a democracy has been threatening to the Kremlin, and Russian officials accuse Zelenskyy of being a Western “marionette.” He is often mocked by the Kremlin’s propagandists as being incapable.

Zelenskyy has also been criticized for not delivering on his biggest campaign promise — to end the long-simmering war between government forces and the Moscow-backed separatists in Ukraine’s east. The conflict that has left 14,000 dead became a flashpoint last week after Russia officially recognized the breakaway territories, Donetsk People’s Republic and Luhansk People’s Republic. The move paved the way for the invasion days later.

While rallying support for Ukraine as tensions rose in the run-up to the invasion, Zelenskyy chose to play down dire warnings coming out of Washington that Moscow was about to attack, saying it was hurting Ukraine’s already fragile economy and morale.

He spooked the markets and sent the foreign media into a frenzy earlier this month when — in his characteristically sarcastic style — he appeared to say in a speech that Russia would attack on Feb. 16, later clarifying he was only referring to media reports of an invasion on this date.

Many questioned his calm tone as being too relaxed, even making him the butt of a joke for American late night show hosts.

But as it became clear last week, Ukraine was running out of diplomatic options to appease Putin, and while Zelenskyy still preached calm, he took on a more serious tone. He insisted Ukraine was ready for any threat while calling for peace.

Assessing Zelenskyy’s performance in the lead-up to the invasion and as commander in chief, Valentyn Gladkykh, a Kyiv-based political analyst, told NBC News that the Ukrainian president had managed to morph into a wartime leader and, for now, Ukrainian society, including his peacetime opponents, seem to be supporting him.

“No Ukrainian president has ever dealt with a full-on invasion on his territory,” Gladkykh said. “Having encountered the unprecedented threat, Zelenskyy has shown his best side.”

But his best side may not be enough — he and Ukraine are trapped in a true David and Goliath contest. Vast nuclear-powered Russia spans 11 time zones and its army counts as one of the largest in the world, leaving the army of Texas-size Ukraine outnumbered and outgunned.

The contrast isn’t only down to size and military might. Within hours of Russia’s first strikes, the difference between Zelenskyy and his counterpart in the Kremlin could not have been more stark.

In his address to justify an incursion into Ukraine late Wednesday, a typically expressionless Putin spoke in his stern ex-KGB officer tone, invoking Russia’s nuclear arsenal and warning anyone who tries to stop him.

“No one should have any doubts that a direct attack on our country will lead to defeat and dire consequences for any potential aggressor,” he said.

A few hours earlier, a visibly exhausted Zelenskyy delivered an impassioned, last-minute plea for peace, appealing to Russian citizens directly — in Russian .

“The people of Ukraine want peace,” he said, warning about the devastation that the war would bring to both people.

“If the Russian leaders don’t want to sit with us behind the table for the sake of peace, maybe they will sit behind the table with you,” Zelenskyy pleaded . “Do Russians want war? I would like to know the answer. But the answer depends only on you.”

Even as Putin’s bombs started falling on Ukrainian soil, Zelenskyy urged Russians to speak up against the war. He thanked those who did Friday, saying “keep fighting for us.”

There is widespread speculation among observers that Putin’s endgame in Ukraine might be to topple Zelenskyy and to install a president more willing to bend before Moscow. Last month, Britain said the Kremlin was seeking to install a pro-Russian leader in Ukraine as part of its plans for an invasion .

“They want to destroy Ukraine politically by destroying its head of state,” Zelenskyy said Thursday, saying he was now “target No. 1” for the Russian forces, but vowed to remain in the capital.

Later Friday, Putin urged Ukrainian soldiers to overthrow their government, even as he suggested he might be willing to enter talks while his forces continued their advance across the country .

But Zelenskyy is left with few options as the Russian offensive intensifies. He could concede ground to Moscow, a move that is likely to be unpopular with many Ukrainians, or hold his position and face the full wrath of the Russian army.

For now, he remains defiant.

“It will continue like this,” he said in the video posted Friday. “Glory to our defenders, glory to Ukraine.”

Yuliya Talmazan is a reporter for NBC News Digital, based in London.

clock This article was published more than 2 years ago

What to know about Volodymyr Zelensky, Ukraine’s TV president turned wartime leader

Just a few years ago, Volodymyr Zelensky was a comedian and actor playing Ukraine’s president on television. Now, he’s a real-life wartime leader directing his country in its fight against a Russian invasion.

Though Zelensky says he has become the Kremlin’s “target No. 1,” he has earned the respect of much of the Ukrainian public by refusing to flee the capital. Instead, he has walked the streets of Kyiv and urged Ukrainians to resist, while crafting a successful communications strategy that has won the hearts and minds of European leaders and voters.

While acknowledging that Moscow has vastly superior forces that it has not yet deployed, Western officials say Zelensky’s leadership has firmed up Ukrainian resolve. Here’s what you need to know about the president.

Who is Olena Zelenska, Ukraine’s first lady and Volodymyr Zelensky’s wife?

- How Russia learned from mistakes to slow Ukraine’s counteroffensive September 8, 2023 How Russia learned from mistakes to slow Ukraine’s counteroffensive September 8, 2023

- Before Prigozhin plane crash, Russia was preparing for life after Wagner August 28, 2023 Before Prigozhin plane crash, Russia was preparing for life after Wagner August 28, 2023

- Inside the Russian effort to build 6,000 attack drones with Iran’s help August 17, 2023 Inside the Russian effort to build 6,000 attack drones with Iran’s help August 17, 2023

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

How war changed Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy

Dave Davies

Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy sings the national anthem during a visit to the city of Izium, in the Kharkiv, Sept. 14, 2022. Ukrainian Presidential Press Office via AP hide caption

Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy sings the national anthem during a visit to the city of Izium, in the Kharkiv, Sept. 14, 2022.

Nearly two years into Russia's war in Ukraine , Time correspondent Simon Shuster says Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy is "almost unrecognizable" from the happy-go-lucky, optimistic comedian Shuster first met in 2019.

"There's just a toughness and a certain darkness about him now that really didn't exist before," Shuster says of the former sitcom star. "He's still extremely committed to this war, to winning this war. ... And he's very single minded, almost obsessive, in pursuing that goal."

Shuster, who has a Russian father and a Ukrainian mother, has been reporting on the region for 17 years and spent months embedded with Zelenskyy's team in Kyiv as the Russian invasion of Ukraine unfolded in February 2022. His new book is The Showman: Inside the Invasion That Shook the World and Made a Leader of Volodymyr Zelensky.

Reporter describes an astounding amount of military hardware going in to help Ukraine

Although the U.S. had warned that a Russian invasion was imminent, Shuster writes that Zelenskyy did not believe that the capital would be attacked. In fact, Shuster says, Ukrainian first lady Olena Zelenska was "totally shocked" by the invasion, and hadn't even packed a suitcase.

From the very beginning, Shuster says Zelenskyy drew on his background as an entertainer to help communicate the Ukrainian plight to a broader audience — even as he worried that the world's attention would eventually fade.

Ukraine invasion — explained

"Often his military tactical decisions were guided by a desire to have these demonstrative victories, something that could really grab the world's attention, whether it's bombing the bridge that connects Russia to Crimea, or various battles ... that maybe were not strategically the most important, but they were dramatic," Shuster says.

Shuster says, looking ahead, that Zelenskyy and his team are open to negotiating for peace with Russia, but they are also developing ways to sustain the war — even if Western support declines.

Volodymyr Zelenskyy went from comedian to icon of democracy. This is how he did it

"President Zelenskyy and his team have a clear vision of where this goes next," Shuster says. "They ... are actively developing ways to sustain the fight, not to be pushed into a capitulation or a negotiation that they don't want to participate in, and to continue fighting on their own resources, their own weapons."

Interview highlights

On Zelenskyy's reaction to the destruction and atrocities in Bucha

Zelenskyy takes center stage in Davos as he tries to rally support for Ukraine

On a personal level, it was absolutely devastating to him. I think, to an extent, that surprised me; he really takes the suffering of civilians close to the heart. He doesn't see them as some kind of abstract mass, sacrificing for the nation. He really feels the pain of individual victims of this war. So that day when he went to Bucha and he saw the atrocities committed there, hundreds of civilians massacred, some tortured, it was just the worst kinds of scenes you could imagine at war time, he was deeply affected by that emotionally.

In Bucha, death, devastation and a graveyard of mines

Ravaged by Russian troops, Bucha rises from the ashes

He later described it as the worst day of that tragic year. He said it taught him that the devil is not far away, not some figment of our imagination but he's right here on this earth. He said he saw the work of the devil there in Bucha. The next phase, when he sort of took in that pain, he moved on to the next stage of the war. He still had a war to fight. And he invited the media to visit Bucha ... and he began inviting his international partners and allies, Europeans, Americans from all over the world. Every time they made a visit to President Zelenskyy in Kyiv, he encouraged them to visit Bucha, to see it for themselves. ... They saw the atrocities for themselves, and it would encourage them to maintain a much higher level of support when they went back home to their capitals after having seen up close the mass graves and the real evidence of Russian war crimes.

On surprising concessions Zelenskyy was willing to make in negotiations with Russia

They continued the negotiations even after the atrocities were revealed in Bucha — even after many of Zelenskyy's own advisers told him, 'We can't go on with these negotiations. We can't talk to these monsters after what they've done to us.' Zelenskyy would continue insisting that no, even though this is a genocidal war, we need to continue trying to find peace at the negotiating table. So they did offer a series of concessions, very serious ones. One of them, the main one was this idea of permanent neutrality. So Ukraine would agree to give up its ambition of joining the NATO alliance. This was one of the main excuses that Vladimir Putin used to justify this horrific invasion, that he wanted to stop NATO from admitting Ukraine. Not that NATO had any plans to admit Ukraine anytime soon, but this was kind of one of the paranoid risks that Putin pointed to. So Zelenskyy said, alright, if that's what you're afraid of, we will make a formal commitment to remain neutral. He even agreed that any military exercises that involve foreign troops on the territory of Ukraine would not happen without Russian approval, if Russia saw those exercises as a risk. So he was willing to really go far in granting concessions early in the invasion. And those negotiations gradually broke apart. One of the reasons was Bucha and the atrocities uncovered. But I think also what we saw was that in April, there were a series of victories that Ukraine achieved on the battlefield that convinced Zelenskyy that, hey, maybe we should see how far we can push this militarily while we have the momentum. Maybe we don't need to negotiate right now. Maybe we fight first, push the Russians back, and then potentially negotiate from a position of strength.

On the July 2019 phone call between Zelenzkyy and President Trump, which later became the basis of Trump's first impeachment

If you read closely the White House transcript that was later released of that phone call, at the end Trump promises to arrange a visit for Zelenskyy to the White House. And it's hard to overstate the importance of that kind of visit for any Ukrainian leader. The United States is by far the most important ally, not only because of relying on U.S. weapons, but also for political support, diplomatic support, financial aid loans. Any incoming Ukrainian president, any Ukrainian president, period, needs to constantly demonstrate the strength of his or her relationship with the United States.

READ: House Intel Committee Releases Whistleblower Complaint On Trump-Ukraine Call