An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Orthop Case Rep

- v.6(3); Jul-Aug 2016

How much Literature Review is enough for a Case Report?

Ashok shyam.

1 Indian Orthopaedic Research Group, Thane, India

Literature review is an essential part of any scientific document. It’s the foundation on which the premise of scientific research is built. Every scientific study has to be seen in context of the existing knowledge and literature. However literature is growing at exponential rate today and especially with so many online journals today it’s really difficult to review all literature. This poses unique challenge to authors who wish to submit a case report for Journal of Orthopaedic Case Reports.

First issue is how much important is literature review for a case report. From early days of case reports, literature review is been the most important cornerstone of a case report. Especially since earlier only rare cases were considered as case reports [ 1 ]. So to establish the rarity of the case it was important to thoroughly review the literature. For us at Journal of Orthopaedic Case Report, literature review is one of the most significant part of the case report. Most of the times it is the section which decides on acceptance or rejection of borderline cases. For cases that are rare we recommend our authors to do a thorough review of literature and also prepare a table of literature review which should be added to the manuscript. For cases where is the focus is on a specific clinical learning point, the literature review needs to be more exhaustive. When a clinical point has to be made, the literature review should cover all the alternative plans that are already described in literature or at least similar cases that have used a different plan. Many cases that are published in Journal of Orthopaedic Case Reports are more on clinical strategies that are improvised and applied to clinical cases. In these scenario we wish our authors to provide rationale for their choices with back up from literature. Also a thorough review of all exiting strategies should be added to the review. The intention is to make the reader aware of all existing management options and then understand why particular option was chosen in the particular patient. This will also help effective communication between the authors and reviewers and ultimately the readers.

The second issue is how much literature to review. With so much literature available at times literature review may miss important article which is relevant to the case. At times it happens that too much literature is added to the article making it bulky and in need for repeated editing. To resolve these issues we would recommend authors to do a thorough PubMed and google Scholar review which will include most important of the articles. If the number of articles relevant to your search are exceeding thirty you may apply filters like selecting articles published in last 5 years or selecting articles only from PubMed. Selecting article only on PubMed will help get the most relevant articles in your review but an additional scrutiny of google result will help you not miss out on important articles. Google will most of the times provide a very comprehensive list of articles and it may need some effort on part of authors to find the relevant articles. But combining both search strategies will definitely make the review more complete and relevant. The number of references should be limited to maximum of 30 for journal of orthopaedic case reports. This will again require authors to review select the most relevant articles from the literature search. Try and include the most recent articles and also from the most relevant authors and medical centres. In case a particular authors has written multiple articles on similar topic, one of his most relevant can be included while others can be left. Articles that are most close to your clinical scenario should be preferred over other articles. Also articles that have chosen strategies similar to yours should be preferred. If the number of articles is still much more, try to limit the references in terms of geography and include articles that are relevant in your country or geographical location to make is more comparable. Also patient profiles can be matched in terms of age and gender to provide for a better comparison between your case and the case from literature. As far as possible provide a literature review table with list of articles, authors names, number of patients, interventions, results and complications to provide a complete perspective to reader. Review of complications needs a special mention and it should be a part of every surgical case that is reported.

In the end try and weave a continuous narrative including parts from your case and reference to context from literature and make an interesting story for readers and editors. We all love a good story which is told in a well woven text and has relevant learning points underlined.

Editor-Journal of Orthopaedic Case Reports

Conflict of Interest: Nil

Source of Support: None

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved April 1, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 30 January 2023

A student guide to writing a case report

- Maeve McAllister 1

BDJ Student volume 30 , pages 12–13 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

21 Accesses

Metrics details

As a student, it can be hard to know where to start when reading or writing a clinical case report either for university or out of special interest in a Journal. I have collated five top tips for writing an insightful and relevant case report.

A case report is a structured report of the clinical process of a patient's diagnostic pathway, including symptoms, signs, diagnosis, treatment planning (short and long term), clinical outcomes and follow-up. 1 Some of these case reports can sometimes have simple titles, to the more unusual, for example, 'Oral Tuberculosis', 'The escapee wisdom tooth', 'A difficult diagnosis'. They normally begin with the word 'Sir' and follow an introduction from this.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

We are sorry, but there is no personal subscription option available for your country.

Buy this article

Purchase on Springer Link

Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Guidelines To Writing a Clinical Case Report. Heart Views 2017; 18 , 104-105.

British Dental Journal. Case reports. Available online at: www.nature.com/bdj/articles?searchType=journalSearch&sort=PubDate&type=case-report&page=2 (accessed August 17, 2022).

Chate R, Chate C. Achenbach's syndrome. Br Dent J 2021; 231: 147.

Abdulgani A, Muhamad, A-H and Watted N. Dental case report for publication; step by step. J Dent Med Sci 2014; 3 : 94-100.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Queen´s University Belfast, Belfast, United Kingdom

Maeve McAllister

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Maeve McAllister .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

McAllister, M. A student guide to writing a case report. BDJ Student 30 , 12–13 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41406-023-0925-y

Download citation

Published : 30 January 2023

Issue Date : 30 January 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41406-023-0925-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Writing a Case Report: Literature Review

- Introduction

- Literature Review

- Additional Help

Common Questions about Literature Reviews

- What a Literature Review is NOT

- What is a Literature Review?

- How is a Literature Review different from an academic research paper?

- Why do we write Literature Reviews?

- Who writes Literature Reviews?

OK. You’ve got to write a literature review. You dust off a novel and a book of poetry, settle down in your chair, and get ready to issue a “thumbs up” or “thumbs down” as you leaf through the pages. “Literature review” done. Right?

Wrong! The “literature” of a literature review refers to any collection of materials on a topic, not necessarily the great literary texts of the world. “Literature” could be anything from a set of government pamphlets on British colonial methods in Africa to scholarly articles on the treatment of a torn ACL. And a review does not necessarily mean that your reader wants you to give your personal opinion on whether or not you liked these sources.

A literature review discusses published information in a particular subject area, and sometimes information in a particular subject area within a certain time period.

A literature review can be just a simple summary of the sources, but it usually has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis. A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information. It might give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations. Or it might trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates. And depending on the situation, the literature review may evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant.

The main focus of an academic research paper is to develop a new argument, and a research paper is likely to contain a literature review as one of its parts. In a research paper, you use the literature as a foundation and as support for a new insight that you contribute. The focus of a literature review, however, is to summarize and synthesize the arguments and ideas of others without adding new contributions.

Literature reviews provide you with a handy guide to a particular topic. If you have limited time to conduct research, literature reviews can give you an overview or act as a stepping stone. For professionals, they are useful reports that keep them up to date with what is current in the field. For scholars, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the writer in his or her field. Literature reviews also provide a solid background for a research paper’s investigation. Comprehensive knowledge of the literature of the field is essential to most research papers.

Literature reviews are written occasionally in the humanities, but mostly in the sciences and social sciences; in experiment and lab reports, they constitute a section of the paper. Sometimes a literature review is written as a paper in itself.

Things to consider before starting your Literature Review

- Find models

- Narrow your topic

- Consider whether your sources are current

If your assignment is not very specific, seek clarification from your instructor:

- Roughly how many sources should you include?

- What types of sources (books, journal articles, websites)?

- Should you summarize, synthesize, or critique your sources by discussing a common theme or issue?

- Should you evaluate your sources?

- Should you provide subheadings and other background information, such as definitions and/or a history?

Look for other literature reviews in your area of interest or in the discipline and read them to get a sense of the types of themes you might want to look for in your own research or ways to organize your final review. You can simply put the word “review” in your search engine along with your other topic terms to find articles of this type on the Internet or in an electronic database. The bibliography or reference section of sources you’ve already read are also excellent entry points into your own research.

There are hundreds or even thousands of articles and books on most areas of study. The narrower your topic, the easier it will be to limit the number of sources you need to read in order to get a good survey of the material. Your instructor will probably not expect you to read everything that’s out there on the topic, but you’ll make your job easier if you first limit your scope.

And don’t forget to tap into your professor’s (or other professors’) knowledge in the field. Ask your professor questions such as: “If you had to read only one book from the 90’s on topic X, what would it be?” Questions such as this help you to find and determine quickly the most seminal pieces in the field.

Some disciplines require that you use information that is as current as possible. In the sciences, for instance, treatments for medical problems are constantly changing according to the latest studies. Information even two years old could be obsolete. However, if you are writing a review in the humanities, history, or social sciences, a survey of the history of the literature may be what is needed, because what is important is how perspectives have changed through the years or within a certain time period. Try sorting through some other current bibliographies or literature reviews in the field to get a sense of what your discipline expects. You can also use this method to consider what is currently of interest to scholars in this field and what is not.

Strategies for writing a Literature Review

- Finding a focus

- Convey it to your reader

- Consider organization

A literature review, like a term paper, is usually organized around ideas, not the sources themselves as an annotated bibliography would be organized. This means that you will not just simply list your sources and go into detail about each one of them, one at a time. No. As you read widely but selectively in your topic area, consider instead what themes or issues connect your sources together. Do they present one or different solutions? Is there an aspect of the field that is missing? How well do they present the material and do they portray it according to an appropriate theory? Do they reveal a trend in the field? A raging debate? Pick one of these themes to focus the organization of your review.

A literature review may not have a traditional thesis statement (one that makes an argument), but you do need to tell readers what to expect. Try writing a simple statement that lets the reader know what is your main organizing principle. Here are a couple of examples:

- The current trend in treatment for congestive heart failure combines surgery and medicine.

- More and more cultural studies scholars are accepting popular media as a subject worthy of academic consideration.

You’ve got a focus, and you’ve stated it clearly and directly. Now what is the most effective way of presenting the information? What are the most important topics, subtopics, etc., that your review needs to include? And in what order should you present them? Develop an organization for your review at both a global and local level:

First, cover the basic categories

Just like most academic papers, literature reviews also must contain at least three basic elements: an introduction or background information section; the body of the review containing the discussion of sources; and, finally, a conclusion and/or recommendations section to end the paper. The following provides a brief description of the content of each:

- Introduction: Gives a quick idea of the topic of the literature review, such as the central theme or organizational pattern.

- Body: Contains your discussion of sources and is organized either chronologically, thematically, or methodologically (see below for more information on each).

- Conclusions/Recommendations: Discuss what you have drawn from reviewing literature so far. Where might the discussion proceed?

Begin Writing

- Use evidence

- Be selective

- Use quotes sparingly

- Summarize and synthesize

- Keep your own voice

- Use caution when paraphrasing

Once you’ve settled on a general pattern of organization, you’re ready to write each section. There are a few guidelines you should follow during the writing stage as well. Here is a sample paragraph from a literature review about sexism and language to illuminate the following discussion:

However, other studies have shown that even gender-neutral antecedents are more likely to produce masculine images than feminine ones (Gastil, 1990). Hamilton (1988) asked students to complete sentences that required them to fill in pronouns that agreed with gender-neutral antecedents such as “writer,” “pedestrian,” and “persons.” The students were asked to describe any image they had when writing the sentence. Hamilton found that people imagined 3.3 men to each woman in the masculine “generic” condition and 1.5 men per woman in the unbiased condition. Thus, while ambient sexism accounted for some of the masculine bias, sexist language amplified the effect. (Source: Erika Falk and Jordan Mills, “Why Sexist Language Affects Persuasion: The Role of Homophily, Intended Audience, and Offense,” Women and Language19:2).

In the example, the writers refer to several other sources when making their point. A literature review in this sense is just like any other academic research paper. Your interpretation of the available sources must be backed up with evidence to show that what you are saying is valid.

Select only the most important points in each source to highlight in the review. The type of information you choose to mention should relate directly to the review’s focus, whether it is thematic, methodological, or chronological.

Falk and Mills do not use any direct quotes. That is because the survey nature of the literature review does not allow for in-depth discussion or detailed quotes from the text. Some short quotes here and there are okay, though, if you want to emphasize a point, or if what the author said just cannot be rewritten in your own words. Notice that Falk and Mills do quote certain terms that were coined by the author, not common knowledge, or taken directly from the study. But if you find yourself wanting to put in more quotes, check with your instructor.

Remember to summarize and synthesize your sources within each paragraph as well as throughout the review. The authors here recapitulate important features of Hamilton’s study, but then synthesize it by rephrasing the study’s significance and relating it to their own work.

While the literature review presents others’ ideas, your voice (the writer’s) should remain front and center. Notice that Falk and Mills weave references to other sources into their own text, but they still maintain their own voice by starting and ending the paragraph with their own ideas and their own words. The sources support what Falk and Mills are saying.

When paraphrasing a source that is not your own, be sure to represent the author’s information or opinions accurately and in your own words. In the preceding example, Falk and Mills either directly refer in the text to the author of their source, such as Hamilton, or they provide ample notation in the text when the ideas they are mentioning are not their own, for example, Gastil’s. For more information, please see our student handbook .

Revise, revise, revise

Draft in hand? Now you’re ready to revise. Spending a lot of time revising is a wise idea, because your main objective is to present the material, not the argument. So check over your review again to make sure it follows the assignment and/or your outline. Then, just as you would for most other academic forms of writing, rewrite or rework the language of your review so that you’ve presented your information in the most concise manner possible. Be sure to use terminology familiar to your audience; get rid of unnecessary jargon or slang. Finally, double check that you’ve documented your sources and formatted the review appropriately for your discipline.

Writing a Literature Review

How to Organize

- Chronological

- By publication

- Methodological

- Other Sections

Once you have the basic categories in place, then you must consider how you will present the sources themselves within the body of your paper. Create an organizational method to focus this section even further.

To help you come up with an overall organizational framework for your review, consider the following scenario:

You’ve decided to focus your literature review on materials dealing with sperm whales. This is because you’ve just finished reading Moby Dick, and you wonder if that whale’s portrayal is really real. You start with some articles about the physiology of sperm whales in biology journals written in the 1980’s. But these articles refer to some British biological studies performed on whales in the early 18th century. So you check those out. Then you look up a book written in 1968 with information on how sperm whales have been portrayed in other forms of art, such as in Alaskan poetry, in French painting, or on whale bone, as the whale hunters in the late 19th century used to do. This makes you wonder about American whaling methods during the time portrayed in Moby Dick, so you find some academic articles published in the last five years on how accurately Herman Melville portrayed the whaling scene in his novel.

Now consider some typical ways of organizing the sources into a review:

If your review follows the chronological method, you could write about the materials above according to when they were published. For instance, first you would talk about the British biological studies of the 18th century, then about Moby Dick, published in 1851, then the book on sperm whales in other art (1968), and finally the biology articles (1980s) and the recent articles on American whaling of the 19th century. But there is relatively no continuity among subjects here. And notice that even though the sources on sperm whales in other art and on American whaling are written recently, they are about other subjects/objects that were created much earlier. Thus, the review loses its chronological focus.

Order your sources by publication chronology, then, only if the order demonstrates a more important trend. For instance, you could order a review of literature on biological studies of sperm whales if the progression revealed a change in dissection practices of the researchers who wrote and/or conducted the studies.

A better way to organize the above sources chronologically is to examine the sources under another trend, such as the history of whaling. Then your review would have subsections according to eras within this period. For instance, the review might examine whaling from pre-1600-1699, 1700-1799, and 1800-1899. Under this method, you would combine the recent studies on American whaling in the 19th century with Moby Dick itself in the 1800-1899 category, even though the authors wrote a century apart.

Thematic reviews of literature are organized around a topic or issue, rather than the progression of time. However, progression of time may still be an important factor in a thematic review. For instance, the sperm whale review could focus on the development of the harpoon for whale hunting. While the study focuses on one topic, harpoon technology, it will still be organized chronologically. The only difference here between a “chronological” and a “thematic” approach is what is emphasized the most: the development of the harpoon or the harpoon technology. But more authentic thematic reviews tend to break away from chronological order. For instance, a thematic review of material on sperm whales might examine how they are portrayed as “evil” in cultural documents. The subsections might include how they are personified, how their proportions are exaggerated, and their behaviors misunderstood. A review organized in this manner would shift between time periods within each section according to the point made.

A methodological approach differs from the two above in that the focusing factor usually does not have to do with the content of the material. Instead, it focuses on the “methods” of the researcher or writer. For the sperm whale project, one methodological approach would be to look at cultural differences between the portrayal of whales in American, British, and French art work. Or the review might focus on the economic impact of whaling on a community. A methodological scope will influence either the types of documents in the review or the way in which these documents are discussed.

Once you’ve decided on the organizational method for the body of the review, the sections you need to include in the paper should be easy to figure out. They should arise out of your organizational strategy. In other words, a chronological review would have subsections for each vital time period. A thematic review would have subtopics based upon factors that relate to the theme or issue.

Sometimes, though, you might need to add additional sections that are necessary for your study, but do not fit in the organizational strategy of the body. What other sections you include in the body is up to you. Put in only what is necessary. Here are a few other sections you might want to consider

- Current Situation: Information necessary to understand the topic or focus of the literature review.

- History: The chronological progression of the field, the literature, or an idea that is necessary to understand the literature review, if the body of the literature review is not already a chronology.

- Methods and/or Standards: The criteria you used to select the sources in your literature review or the way in which you present your information. For instance, you might explain that your review includes only peer-reviewed articles and journals.

- Questions for Further Research : What questions about the field has the review sparked? How will you further your research as a result of the review?

- Works Consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the OCOM Library AMA Guide . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M. and Robert A. Schwegler. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers. 6th edition. New York: Longman, 2010.

Jones, Robert, Patrick Bizzaro, and Cynthia Selfe. The Harcourt Brace Guide to Writing in the Disciplines. New York: Harcourt Brace, 1997.

Lamb, Sandra E. How to Write It: A Complete Guide to Everything You’ll Ever Write. Berkeley, Calif.: Ten Speed Press, 1998.

Rosen, Leonard J. and Laurence Behrens. The Allyn and Bacon Handbook. 4th edition. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 2000.

Troyka, Lynn Quitman. Simon and Schuster Handbook for Writers. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 2002.

- << Previous: Introduction

- Next: Examples >>

- Last Updated: Nov 2, 2023 2:12 PM

- URL: https://ocomlibrary.libguides.com/casereport

OCOM Library

Email us at [email protected]

Phone us at 503-253-3443x132

Visit us at 75 NW Couch St, Portland, OR 97209

- Case Reports

- Open access

- Published: 25 February 2021

Renal leiomyoma: a case report and literature review

- Sajal Gerdharee 1 ,

- Abrie van Wyk 2 ,

- Heidi van Deventer ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7472-1773 1 &

- Andre van der Merwe 1

African Journal of Urology volume 27 , Article number: 39 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

2657 Accesses

1 Citations

Metrics details

Renal leiomyomas are exceptionally rare, benign, mesenchymal tumours originating from smooth muscle in the kidney. Historically, because of their small size, most renal leiomyoma cases were discovered incidentally based on autopsy findings. However, since the advent and improved access to imaging modalities such as ultrasound and computed tomography (CT), renal leiomyomas are being discovered more frequently. Although usually incidental discoveries, clinical presenting signs and symptoms comprise abdominal or flank pain, a palpable flank mass, and haematuria in 20% of those with symptoms.

Case presentation

We study the case of an incidentally found, asymptomatic, left kidney mass that presented in a 60-year-old female. Initial suspicions on CT imaging of either renal cell carcinoma or oncocytoma resulted in a radical nephrectomy of the left kidney. Postoperative pathological examination of the mass revealed a renal leiomyoma; a rare, benign tumour that is mostly indistinguishable from malignant tumours on imaging.

Conclusions

With the current availability of ultrasonography and CT, they are often discovered incidentally, and the radiological differential diagnoses are often inadequate or challenging in such cases. The gold standard management of these suspicious cancer cases is still a radical nephrectomy with postoperative pathological and immunohistochemical analysis. Due to its benign nature, patients enjoy excellent prognoses without recurrence. We discuss and briefly review the relevant literature of the clinical, imaging and pathological features of renal leiomyomas and those of the differential diagnoses.

1 Background

Renal leiomyomas are exceptionally rare, benign, mesenchymal tumours originating from smooth muscle in the kidney. Renal smooth muscle can be found within the renal capsule, calyces, pelvis, and blood vessels; hence, any of these areas can be a site of origin for leiomyomas.

Steiner and colleagues found that of symptomatic leiomyomas, 53% of tumours were localised subcapsular, 37% capsular, and 10% within the renal pelvis [ 1 ].

Historically, because of their small size, most renal leiomyoma cases were discovered incidentally based on autopsy findings [ 2 ]. However, since the advent and improved access to imaging modalities such as ultrasound and CT, renal leiomyomas are being discovered more frequently.

Although usually incidental discoveries, clinical presenting signs and symptoms comprise abdominal or flank pain, a palpable flank mass, and haematuria in 20% of those with symptoms. Cases suggest a higher prevalence in adult females, with an average age of 42 at presentation [ 1 , 3 ]. Leiomyomas of the kidney are even rarer in the paediatric population, and there have been very few reported cases of these tumours in the literature. Some cases of interest included a six-year-old boy with an initially suspected Wilms tumour; a leiomyoma occurring in a transplanted kidney in association with the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), five years post renal transplant; and a vascular renal leiomyoma in an 11-year-old with bilateral RCC [ 4 ].

Over ten years, the Brady Urological Institute reviewed several consecutive nephrectomies as a result of renal tumours. Of a total of 1030 nephrectomies, renal leiomyomas comprised 0.3% of the total, and 1.5% of all benign tumours removed [ 5 ].

In terms of etiological factors leading to the development of a renal leiomyoma, there are various theories and suggested causative factors. Krishnan and colleagues showed a possible causal relationship between Epstein-Barr virus and renal leiomyoma in immunocompromised patients, while Tsujimura and colleagues suggested a possible link with tuberous sclerosis; a condition more commonly associated with renal angiomyolipoma (AML) [ 6 , 7 ].

When considering the relevant differential diagnosis concerning clinical presentation and imaging studies, three renal tumours that are more commonly found are AML, oncocytoma, and the diagnostic importance that lies in distinguishing them from the malignant RCC [ 8 ]. Renal cell carcinomas make up the majority of contrast-enhancing small renal masses, the most prevalent histological type being the clear cell RCC. Frank and colleagues demonstrated a clear cell RCC incidence of 55% after 2770 surgeries (radical nephrectomies or nephron-sparing) for solid, unilateral, non-metastatic tumours [ 9 ].

AMLs are benign tumours in the perivascular epithelioid cell tumour family, comprising variable mixtures of thick-walled blood vessels, mature fat, and smooth muscle. It may sometimes be represented by dominance of the smooth muscle component, hence its likeness to a leiomyoma. Furthermore, they are characterised by smooth muscle and melanocytic marker (HMB-45) co-expression [ 10 ]. In contrast to this, renal leiomyoma tumour cells typically test negative for HMB-45, but express smooth muscle actin and desmin. Angiomyolipoma is also relatively well-distinguished radiologically as an enhancing mass with macroscopic fat, devoid of calcification. Small, fat-poor tumours can be more challenging to distinguish from RCC [ 11 ].

Oncocytoma often displays the appearance of a well-circumscribed, homogeneous, and solid lesion, and may often demonstrate central scarring—features that are not mutually exclusive with the presentation of RCC [ 12 ]. Postoperatively the pathologist also needs to differentiate leiomyoma from leiomyosarcoma [ 10 ]. Histological features associated with leiomyosarcoma are tumour necrosis, nuclear pleomorphism, and increased mitotic activity [ 13 ].

2 Case presentation

2.1 clinical history.

The patient under study is a 60-year-old female, previously diagnosed with hypertension, diabetes mellitus (type II) and congestive cardiac failure. After a routine chest radiograph displayed suspicious nodularity in both lung apices, a CT was performed, and the nodules were queried to be post-infective changes or suspicious of metastases. An abdominal CT was then performed in search of a primary neoplastic lesion and a mixed, solid-cystic mass in the lower pole of the left kidney was discovered. The mass was asymptomatic, and she had no associated pain, discomfort or haematuria.

2.2 Investigations

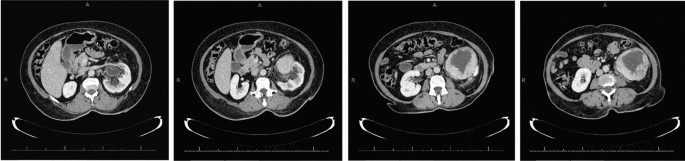

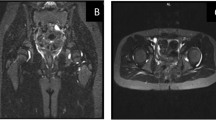

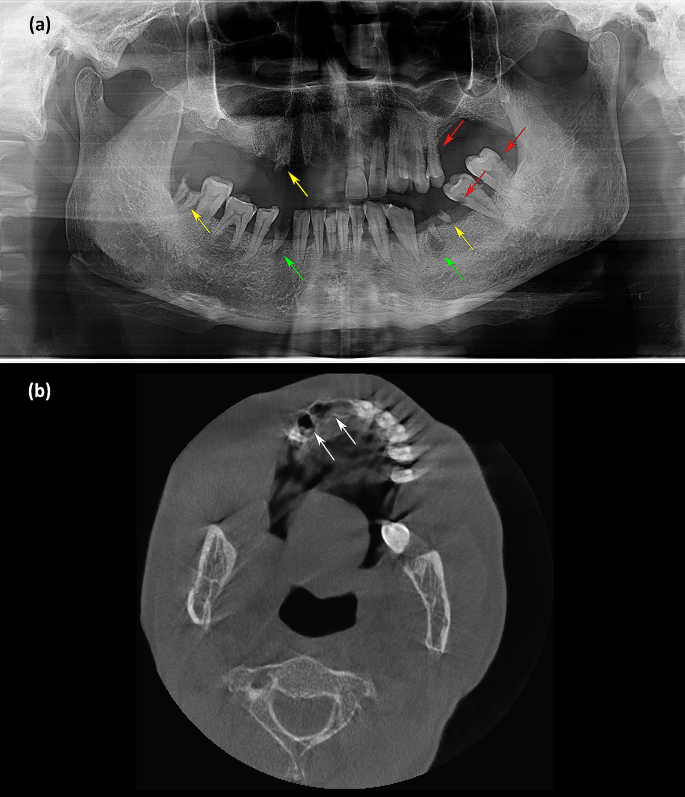

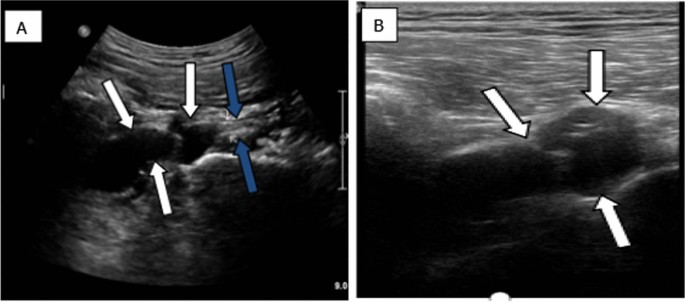

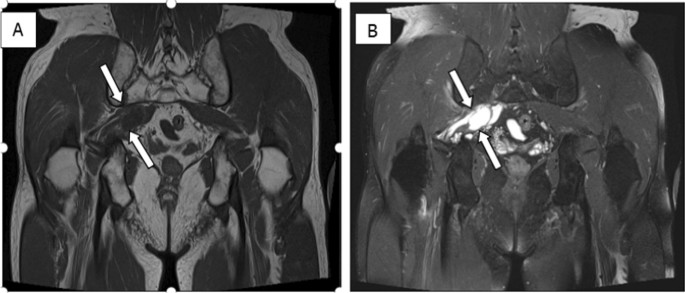

The abdominal CT showed a large solid/cystic tumour in the lower pole of the left kidney. The dimensions of the renal mass was 9 cm × 8 cm, demonstrating peripheral soft tissue enhancement with a central, cystic component measuring 12 HU (Hounsfield Units). It was highly suspicious of an RCC with central necrosis. Two months later, a repeat contrasted CT was done to evaluate for the progression of the suspicious lung lesions, which may have indicated metastases, and for the appearance of new intra-abdominal metastases. CT findings were unchanged from before, as seen in Figs. 1 and 2 .

Abdominal CT demonstrating renal mass

There was displacement of the lower pole of the kidney with marked compression of the proximal ureter, which was splayed around the mass—resulting in mild hydronephrosis. The mass demonstrated fat stranding and bordered the retroperitoneal fascia but did not bridge or enter the peritoneal cavity. Similarly, renal vessels were splayed but not infiltrated, with no signs of neovascularisation. There was no clear claw sign demonstrated to suggest renal origin, and no associated lymphadenopathy or distant metastases. These features were not in keeping with an aggressive RCC, and a possible diagnosis of a renal oncocytoma was considered. However, it is noted that the absence of a renal claw sign and clear origin from the renal cortex remains atypical for either of the diagnoses mentioned.

The patient was prepared for surgery and underwent a radical nephrectomy. The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged.

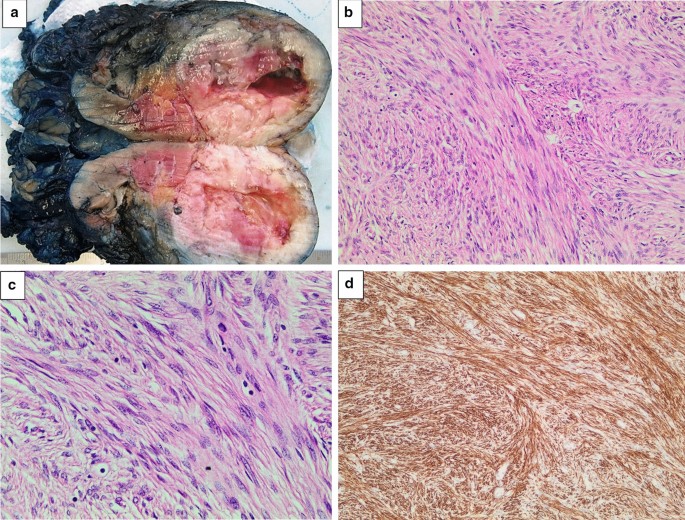

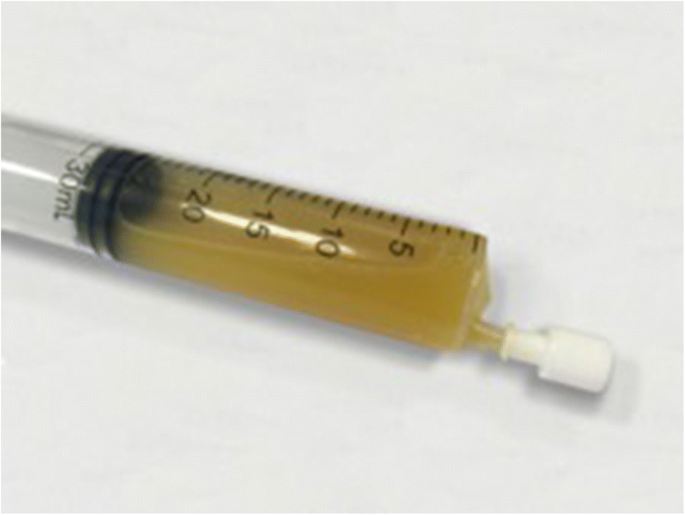

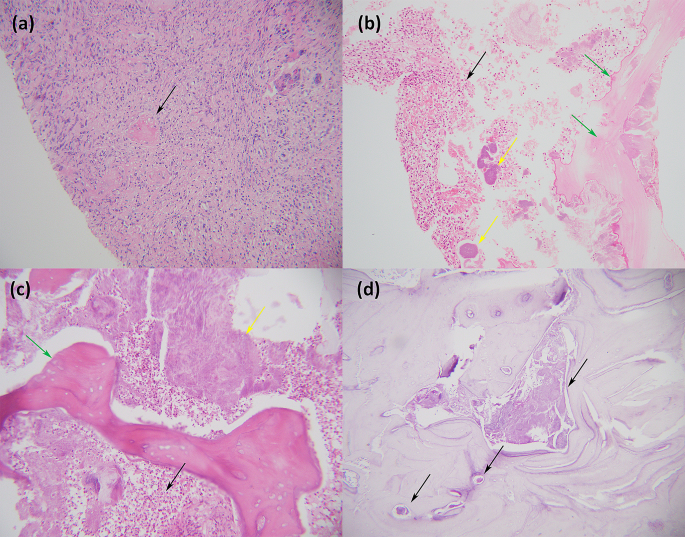

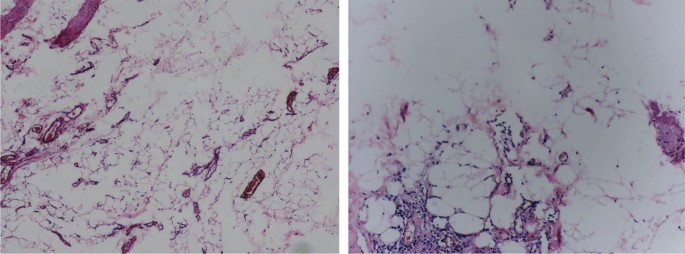

Histological sections of the tumour displayed a well-circumscribed, unencapsulated mass comprising spindled cells with a fascicular growth pattern (Fig. 3 ). There was central cystic degeneration, associated with degenerative atypia but without any mitotic figures noted. There was no evidence of vascular invasion or necrosis. Immunohistochemically, the lesion was strongly positive for desmin and smooth muscle actin and negative for HMB-45 and melan A. Chromogenic in situ hybridisation for Epstein-Barr encoded RNA was negative, excluding EBV associated smooth muscle neoplasm, which may have similar morphology. These results, in keeping with clinically absent features of tuberous sclerosis, favoured a diagnosis of a renal leiomyoma. There was unfortunately no mention made by the histological report of whether the tumour originated from capsular or subcapsular renal tissue.

a Left kidney bisected. A round, well-circumscribed tumour with central cystic degeneration is present in the lower pole of the kidney. b The tumour is composed of spindle-shaped cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm growing in intersecting fascicles. Haematoxylin and eosin, original magnification × 200. c The nuclei of the tumour cells often have rounded ends (“cigar-shaped” nuclei). Scattered lymphocytes are noted in the background. Significant pleomorphism, tumour necrosis and increased mitotic activity are absent. Haematoxylin and eosin, original magnification × 400. d An immunohistochemical stain for desmin shows strong and diffuse cytoplasmic staining. Original magnification × 200

3 Discussion

The literature reviewed comprised entirely of case studies that included a diagnosis of renal leiomyoma, within no specific time period. Provided that the diagnosis of a renal leiomyoma was made, there were no other exclusion criteria other than the patient’s age being older than 16 years—of which no such cases were eliminated thereby. Cases were reviewed and added on a case-to-case basis as they were found. Search engines utilised in English, comprised primarily of PubMed, and the university library e-databases.

We reviewed 20 cases of renal leiomyomas in adults (19 from the literature and one of our own), summarised in Table 1 . The mean age was 49, with a 70% predominance of female patients. Sixty-eight per cent of these cases were symptomatic before the discovery of their renal leiomyomas. Of those cases reporting signs, 53% had abdominal pain, 32% had a flank mass, while only 26% were haematuric. Only one of nineteen presented with all three clinical features simultaneously, while 32% had at least two of the features present. In cases where tumour origin was mentioned, there was a 50% predominance of capsular leiomyomas, and only two cases were located in the subcapsular area. Of the cases that reported immunohistochemical testing, 100% of tumours tested negative for HMB-45. All the tumours that were tested for smooth muscle actin and/or desmin were positive for these markers. Tumour sizes ranged from 1.3 to 32 cm, with an average diameter of 9.6 cm.

Some of these results differ slightly from the literature represented earlier concerning presentation, which is likely due to the sample size and lack of reporting on the various clinical and pathological characteristics in many of these cases.

3.1 Pre-operative diagnostics

On ultra-sonographic imaging, leiomyomas typically appear hypoechoic with either a solid or a cystic appearance [ 10 ]. Some helpful CT features were pointed out by Derchi and colleagues to help with the differential diagnosis. Firstly, the density before contrast of all leiomyomas displayed a likeness to that of muscle and was hyper-dense. After the addition of contrast, the masses had lower enhancement in comparison with the renal parenchyma. Secondly, the lesions display no infiltration of neighbouring tissue and are usually well-circumscribed and located peripherally. These features see the addition of a renal leiomyoma to the differential; however, malignant disease still cannot be excluded. The presence of infiltration virtually excludes a benign renal leiomyoma [ 1 , 14 ].

The size and enhancement of incidentally discovered, small, asymptomatic renal masses may be of value in determining the likely nature of such lesions.

A study of 2770 renal tumours found that almost half the number of non-metastatic tumours smaller than 1 cm were benign, while tumours of 7 cm or larger comprised only 6.3% of benign tumours [ 9 ]. O’Connor and colleagues discovered incidental renal lesions greater than 1 cm in 433 of 3001 (14%) in asymptomatic adults after an abdominopelvic CT for screening colonography. Of these, 87% were radiologically characterised as benign and a further 13% of “indeterminate significance” [ 15 ]. Radiologically, the enhancement of a renal lesion is considered a valuable characteristic in determining the nature of the lesion. While there is some consensus that enhancement of 20 HU or more is significant in identifying malignant lesions, some authors suggest that lesions displaying 10 HU or more should still be considered significantly suspicious of malignancy. Therefore, lesions displaying attenuation from 10 HU to 19 HU are considered “indeterminate”.

This determination has some implications when considering the possibility of pre-operative diagnosis in the form of CT-guided core biopsies. Although it remains controversial, Eshed and colleagues believe that due to the low complication rate and value in implementing disease-tailored management, indication for core biopsies should include radiographically indeterminate lesions and small renal masses. In agreement, Romero and colleagues suggest that there is a place for biopsy and conservative management in patients with radiographic and clinical evidence of a diagnosis other than RCC. These lesions with benign biopsy results can then undergo resection, re-evaluation or close clinical or imaging surveillance [ 5 , 16 ]. Where availability and resources allow for such, the use of Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) in the diagnosis of renal masses is another area of diagnostics which may benefit pre-operative diagnostics. However, in a resource-poor setting, this modality is a less feasible option than CT due to limited availability in the public sector, and cost. It is thus not further discussed in this paper.

Currently, management of larger lesions still holds surgical resection as its gold standard, with radical nephrectomy being the usual approach to suspicious lesions. Lesions equal to, or smaller than, 4 cm allow consideration for nephron-sparing resections, and smaller renal masses can be biopsied—although still considered a somewhat controversial practice [ 1 ]. In the ideal setting, nephron-sparing resection could also be a consideration, given the availability of extemporaneous examination during the surgical procedure. Likewise, the same remains true with regard to performing an initial renal biopsy for immunohistological diagnosis. The indications for either of which would also need to be correlated with pre-operative imaging findings.

4 Conclusion

Accurate detection of renal leiomyomas may be challenging in the pre-operative setting, given the variety of findings on imaging. There are very few characteristics that may help rule in or rule out the leiomyoma amongst its differential, especially when suspicious or malignant lesions have to be considered. Pre-operative, image-guided core biopsy would undoubtedly aid in distinguishing the leiomyoma. However, its use is dependent on multiple factors ranging from clinical presentation to size and contrast enhancement of the lesion, and availability of resources. In addition to being viewed as a controversial practice, the place for biopsy in the resource-poor setting is yet to be determined. Until more rigid indications are established surrounding conservative treatment, definitive management will invariably be surgical, as these patients enjoy an excellent prognosis without recurrence.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing does not apply to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

Angiomyolipoma

Computed tomography

Epstein–Barr virus

Hounsfield units

Renal cell carcinoma

Steiner M, Quinlan D, Goldman S, Millmond S, Hallowell M, Stutzman R et al (1990) Leiomyoma of the kidney: presentation of 4 new cases and the role of computerized tomography. J Urol 143(5):994–998

Article CAS Google Scholar

Belis J, Post G, Rochman S, Franklin MD (1979) Genitourinary leiomyomas. Urology 13(4):424–429

Andreoiu M, Drachenberg D, Macmahon R (2009) Giant renal leiomyoma: a case report and brief review of the literature. Can UrolAssoc J 3(5):58–60

Google Scholar

Nakib G, Mahgoub N, Calcaterra V, Pelizzo G (2017) Renal leiomyoma in pediatric age: a rare case report with review of the literature. J PediatrSurg Case Rep 27:43–46

Romero F, Kohanim S, Lima G, Permpongkosol S, Fine S, Kavoussi L (2005) Leiomyomas of the kidney: emphasis on conservative diagnosis and treatment. Urology 66(6):1319.e1–3

Article Google Scholar

Krishnan R, Freeman J, Creager A (1999) Epstein–Barr virus induced renal leiomyoma. J Urol 161(1):212

Tsujimura A, Miki T, Sugao H, Takaha M, Takeda M, Kurata A (1996) Renal leiomyoma associated with tuberous sclerosis. UrolInt 57(3):192–193

CAS Google Scholar

Nagar A, Raut A, Narlawar R, Bhatgadde V, Rege S, Thapar V (2004) Giant renal capsular leiomyoma: study of two cases. Br J Radiol 77(923):957–958

Frank I, Blute M, Cheville J, Lohse C, Weaver A, Zincke H (2003) Solid renal tumors: an analysis of pathological features related to tumor size. J Urol 170(6 Pt 1):2217–2220

Brunocilla E, Pultrone C, Schiavina R, Vagnoni V, Caprara G, Martorana G (2012) Renal leiomyoma: case report and literature review. Can UrolAssoc J 6(2):E87-90

Kim J, Park S, Shon J, Cho K (2004) Angiomyolipoma with minimal fat: differentiation from renal cell carcinoma at biphasic helical CT. Radiology 230(3):677–684

Perez-Ordonez B, Hamed G, Campbell S, Erlandson RA, Russo P, Gaudin PB et al (1997) Renal oncocytoma: a clinicopathologic study of 70 cases. Am J SurgPathol 21(8):871–883

Hogan A, Smyth G, D’Arcy C, O’Brien A, Quinlan D (2008) Renal capsular leiomyoma. Urology 71(6):1226.e1–3

Derchi L, Grenier N, Heinz-Peer G, Dogra V, Franco F, Rollandi G et al (2008) Imaging of renal leiomyomas. ActaRadiol 49(7):833–838

O’Connor S, Pickhardt P, Kim D, Oliva M, Silverman S (2011) Incidental Finding of renal masses at unenhanced CT: prevalence and analysis of features for guiding management. Am J Roentgenol 197(1):139–145

Eshed I, Elias S, Sidi A (2004) Diagnostic value of CT-guided biopsy of indeterminate renal masses. ClinRadiol 59(3):262–267

Mitra B, Debnath S, Pal M, Paul B, Saha T, Maiti A (2012) Leiomyoma of kidney: an Indian experience with literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep 3(11):569–573

Larbcharoensub N, Limprasert V, Pangpunyakulchai D, Sanpaphant S, Wiratkapun C, Kijvikai K (2017) Renal leiomyoma: a case report and review of the literature. Urol Case Rep 7(13):3–5

Akbulut F, Şahan M, Üçpınar B, Savun M, Özgör F, Arslan B et al (2016) A rare case of renal leiomyoma treated with laparoscopic partial nephrectomy. Med Bull Haseki 54(1):41–43

Kocak C, Kabay S, Isler B (2015) Leiomyoma of the renal vein: a rare tumor presenting as a renal mass. Case Rep Urol 5(2015):1–3

Lal A, Galwa R, Chandrasekar P, Sachdeva M, Vashisht R, Khandelwal N (2009) A huge renal capsular leiomyoma mimicking retroperitoneal sarcoma. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 20(6):1069–1071

PubMed Google Scholar

Takezaki T, Nakama M, Ogawa A (1985) Renal leiomyoma with extensive cystic degeneration. Urology 25(4):401–403

Fu L, Humphrey P, Adeniran A (2015) Renal leiomyoma. J Urol 193(3):997–998

Patil P, McKenney J, Trpkov K, Hes O, Montironi R, Scarpelli M et al (2015) Renal leiomyoma: a contemporary multi-institution study of an infrequent and frequently misclassified neoplasm. Am J SurgPathol 39(3):349–356

Download references

Acknowledgements

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Division of Urology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Tygerberg Hospital, Stellenbosch University, P.O. Box 19063, Tygerberg, 7505, South Africa

Sajal Gerdharee, Heidi van Deventer & Andre van der Merwe

Division of Anatomical Pathology, NHLS Tygerberg and University of Stellenbosch, Cape Town, South Africa

Abrie van Wyk

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

SG did the write up of the case report and literature review as part of his undergraduate studies. HVD and AVDM contributed equally to the writing of the manuscript. AVW reviewed the pathology section of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Heidi van Deventer .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethics approval was obtained from the Health Research Ethics Committee of Stellenbosch University with the reference number of UC19/10/048. Consent to participate is not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication of the patient’s clinical details and clinical images was obtained from the patient.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Gerdharee, S., van Wyk, A., van Deventer, H. et al. Renal leiomyoma: a case report and literature review. Afr J Urol 27 , 39 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12301-021-00143-z

Download citation

Received : 27 November 2019

Accepted : 12 February 2021

Published : 25 February 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12301-021-00143-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Renal leiomyoma

- Case report

- Renal leiomyoma diagnosis

- Literature review

- Renal leiomyoma imaging

CC0006 Basics of Report Writing

Structure of a report (case study, literature review or survey).

- Structure of report (Site visit)

- Citing Sources

- Tips and Resources

The information in the report has to be organised in the best possible way for the reader to understand the issue being investigated, analysis of the findings and recommendations or implications that relate directly to the findings. Given below are the main sections of a standard report. Click on each section heading to learn more about it.

- Tells the reader what the report is about

- Informative, short, catchy

Example - Sea level rise in Singapore : Causes, Impact and Solution

The title page must also include group name, group members and their matriculation numbers.

Content s Page

- Has headings and subheadings that show the reader where the various sections of the report are located

- Written on a separate page

- Includes the page numbers of each section

- Briefly summarises the report, the process of research and final conclusions

- Provides a quick overview of the report and describes the main highlights

- Short, usually not more than 150 words in length

- Mention briefly why you choose this project, what are the implications and what kind of problems it will solve

Usually, the abstract is written last, ie. after writing the other sections and you know the key points to draw out from these sections. Abstracts allow readers who may be interested in the report to decide whether it is relevant to their purposes.

Introduction

- Discusses the background and sets the context

- Introduces the topic, significance of the problem, and the purpose of research

- Gives the scope ie shows what it includes and excludes

In the introduction, write about what motivates your project, what makes it interesting, what questions do you aim to answer by doing your project. The introduction lays the foundation for understanding the research problem and should be written in a way that leads the reader from the general subject area of the topic to the particular topic of research.

Literature Review

- Helps to gain an understanding of the existing research in that topic

- To develop on your own ideas and build your ideas based on the existing knowledge

- Prevents duplication of the research done by others

Search the existing literature for information. Identify the data pertinent to your topic. Review, extract the relevant information for eg how the study was conducted and the findings. Summarise the information. Write what is already known about the topic and what do the sources that you have reviewed say. Identify conflicts in previous studies, open questions, or gaps that may exist. If you are doing

- Case study - look for background information and if any similar case studies have been done before.

- Literature review - find out from literature, what is the background to the questions that you are looking into

- Site visit - use the literature review to read up and prepare good questions before hand.

- Survey - find out if similar surveys have been done before and what did they find?

Keep a record of the source details of any information you want to use in your report so that you can reference them accurately.

Methodology

Methodology is the approach that you take to gather data and arrive at the recommendation(s). Choose a method that is appropriate for the research topic and explain it in detail.

In this section, address the following: a) How the data was collected b) How it was analysed and c) Explain or justify why a particular method was chosen.

Usually, the methodology is written in the past tense and can be in the passive voice. Some examples of the different methods that you can use to gather data are given below. The data collected provides evidence to build your arguments. Collect data, integrate the findings and perspectives from different studies and add your own analysis of its feasibility.

- Explore the literature/news/internet sources to know the topic in depth

- Give a description of how you selected the literature for your project

- Compare the studies, and highlight the findings, gaps or limitations.

- An in-depth, detailed examination of specific cases within a real-world context.

- Enables you to examine the data within a specific context.

- Examine a well defined case to identify the essential factors, process and relationship.

- Write the case description, the context and the process involved.

- Make sense of the evidence in the case(s) to answer the research question

- Gather data from a predefined group of respondents by asking relevant questions

- Can be conducted in person or online

- Why you chose this method (questionnaires, focus group, experimental procedure, etc)

- How you carried out the survey. Include techniques and any equipment you used

- If there were participants in your research, who were they? How did you select them and how may were there?

- How the survey questions address the different aspects of the research question

- Analyse the technology / policy approaches by visiting the required sites

- Make a detailed report on its features and your understanding of it

Results and Analysis

- Present the results of the study. You may consider visualising the results in tables and graphs, graphics etc.

- Analyse the results to obtain answer to the research question.

- Provide an analysis of the technical and financial feasibility, social acceptability etc

Discussion, Limitation(s) and Implication(s)

- Discuss your interpretations of the analysis and the significance of your findings

- Explain any new understanding or insights that emerged as a result of your research

- Consider the different perspectives (social, economic and environmental)in the discussion

- Explain the limitation(s)

- Explain how could what you found be used to make a difference for sustainability

Conclusion and Recommendations

- Summarise the significance and outcome of the study highlighting the key points.

- Come up with alternatives and propose specific actions based on the alternatives

- Describe the result or improvement it would achieve

- Explain how it will be implemented

Recommendations should have an innovative approach and should be feasible. It should make a significant difference in solving the issue under discussion.

- List the sources you have referred to in your writing

- Use the recommended citation style consistently in your report

Appendix (if necessary/any)

Include any material relating to the report and research that does not fit in the body of the report, in the appendix. For example, you may include survey questionnaire and results in the appendix.

- << Previous: Structure of a report

- Next: Structure of report (Site visit) >>

- Last Updated: Jan 12, 2024 11:52 AM

- URL: https://libguides.ntu.edu.sg/report-writing

You are expected to comply with University policies and guidelines namely, Appropriate Use of Information Resources Policy , IT Usage Policy and Social Media Policy . Users will be personally liable for any infringement of Copyright and Licensing laws. Unless otherwise stated, all guide content is licensed by CC BY-NC 4.0 .

CASE REPORT article

Case report: a case report and literature review on severe bullous skin reaction induced by anti-pd-1 immunotherapy in a cervical cancer patient.

- 1 The Fifth Department of Oncology, Jinshazhou Hospital of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou, China

- 2 The Second Clinical Medical College, Henan University of Chinese Medicine, Zhengzhou, China

- 3 Pediatric Ward, Henan Province Hospital of TCM, Zhengzhou, China

- 4 Department of Oncology, Fuda Cancer Hospital Guangzhou, Guangzhou, China

Background: Anti-programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) has been successfully used in carcinomas treatment. However, it causes significant adverse effects (AEs), including cutaneous reactions, particularly the life-threatening severe bullous skin reactions (SBSR) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN).

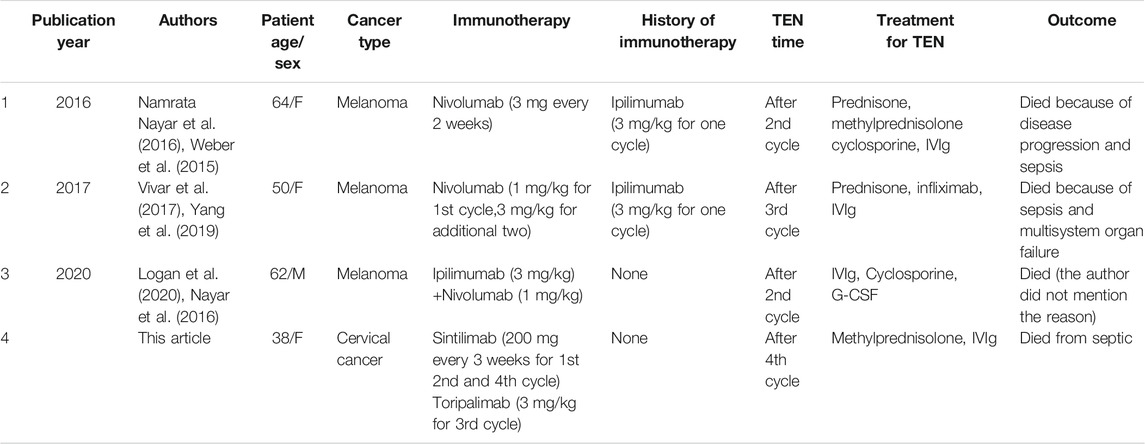

Case summary: Herein, we described for the first time a case report of SBSR induced by anti-PD-1 therapy in a cervical cancer patient. In addition, we revised existing literature on anti-PD-1 induced cutaneous reactions. We reported a cervical cancer patient who was treated with four successive cycles of Sintilimab and Toripalimab injections and developed systemic rashes, bullae, and epidermal desquamation, which worsened and led to infection, eventually causing death after being unresponsive to aggressive treatments.

Conclusion: Anti-PD-1 antibodies commonly cause skin toxicity effects, some of which may be deadly. Therefore, healthcare providers should observe early symptoms and administer proper treatment to prevent aggravation of symptoms.

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women ( Colombo et al., 2012 ). Its main treatment consists of platinum-based chemotherapy, with limited therapeutic outcomes and severe side effects ( Greer et al., 2010 ; Pfaendler and Tewari, 2016 ). Since the introduction of programmed death 1 (PD-1) protein monoclonal antibodies, they have shown outstanding clinical efficacy in multiple cancer types, including advanced cervical cancer ( Martínez and Del Campo, 2017 ; Wang and Li, 2019 ). In this regard, Pembrolizumab was used for advanced cervical cancer in the KEYNOTE-028 clinical study, demonstrating the efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in advanced cervical cancer ( Frenel et al., 2017 ). PD-1 monoclonal antibodies have been shown to potentiate T lymphocytes cytotoxic activity against tumor cells and control tumor growth ( Pedoeem et al., 2014 ; Tumeh et al., 2014 ). Most patients tolerated anti-PD-1 therapy, whereas some presented toxic and side effects ( Champiat et al., 2016 ). Major anti-PD-1 associated adverse effects (AEs) included skin toxicity, endocrine reaction, gastrointestinal reaction, hepatitis, and renal dysfunction ( Hofmann et al., 2016 ; Ansell, 2017 ; Nishijima et al., 2017 ; O’Kane et al., 2017 ; Tie et al., 2017 ; Gubens et al., 2019 ). The most common AEs involved skin reactions such as lichenoid reaction, eczema, vitiligo, and pruritus ( Joseph et al., 2015 ; Robert et al., 2015a ; Weber et al., 2015 ; Ciccarese et al., 2016 ; Hwang et al., 2016 ; Yang et al., 2019 ). However, the most severe skin reaction observed was toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) in three cases of malignant melanoma ( Nayar et al., 2016 ; Vivar et al., 2017 ; Logan et al., 2020 ).

Case Presentations