Voice speed

Text translation, source text, translation results, document translation, drag and drop.

Website translation

Enter a URL

Image translation

- 0 Shopping Cart

Nepal Earthquake 2015

A case study of an earthquake in a low income country (LIC).

Nepal, one of the poorest countries in the world, is a low-income country. Nepal is located between China and India in Asia along the Himalayan Mountains.

A map to show the location of Nepal in Asia

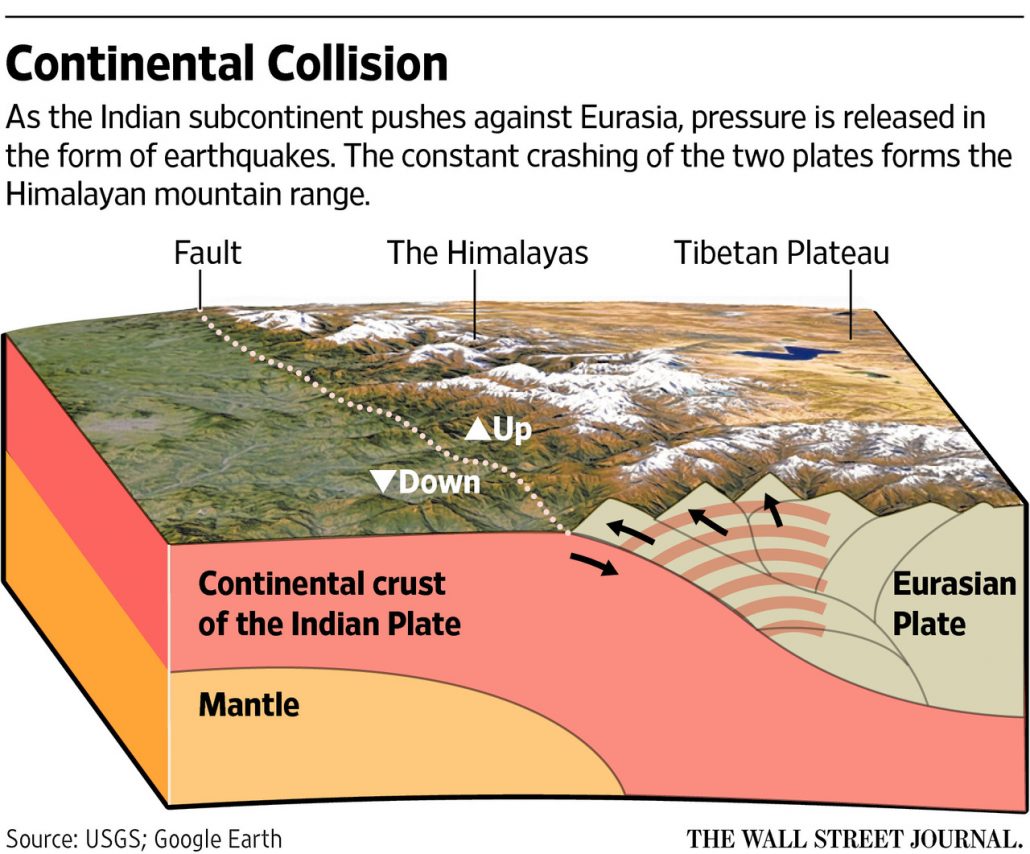

What caused the Nepal Earthquake?

The earthquake occurred on a collision plate boundary between the Indian and Eurasian plates.

What were the impacts of the Nepal earthquake?

Infrastructure.

- Centuries-old buildings were destroyed at UNESCO World Heritage Sites in the Kathmandu Valley, including some at the Changu Narayan Temple and the Dharahara Tower.

- Thousands of houses were destroyed across many districts of the country.

Social and economic

- Eight thousand six hundred thirty-two dead and 19,009 injured.

- It was the worst earthquake in Nepal in more than 80 years.

- People chose to sleep outside in cold temperatures due to the risk of aftershocks causing damaged buildings to collapse.

- Hundreds of thousands of people were made homeless, with entire villages flattened.

- Harvests were reduced or lost that season.

- Economic losses were estimated to be between nine per cent to 50 per cent of GDP by The United States Geological Survey (USGS).

- Tourism is a significant source of revenue in Nepal, and the earthquake led to a sharp drop in the number of visitors.

- An avalanche killed at least 17 people at the Mount Everest Base Camp.

- Many landslides occurred along steep valleys. For example, 250 people were killed when the village of Ghodatabela was covered in material.

What were the primary effects of the 2015 earthquake in Nepal?

The primary effects of the 2015 earthquake in Nepal include:

- Nine thousand people died, and 19,000 people were injured – over 8 million people were affected.

- Three million people were made homeless.

- Electricity and water supplies, along with communications, were affected.

- 1.4 million people needed support with access to water, food and shelter in the days and weeks after the earthquake

- Seven thousand schools were destroyed.

- Hospitals were overwhelmed.

- As aid arrived, the international airport became congested.

- 50% of shops were destroyed, affecting supplies of food and people’s livelihoods.

- The cost of the earthquake was estimated to be US$5 billion.

What were the secondary effects of the 2015 earthquake in Nepal?

The secondary effects of the 2015 earthquake in Nepal include:

- Avalanches and landslides were triggered by the quake, blocking rocks and hampering the relief effort.

- At least nineteen people lost their lives on Mount Everest due to avalanches.

- Two hundred fifty people were missing in the Langtang region due to an avalanche.

- The Kali Gandaki River was blocked by a landslide leading many people to be evacuated due to the increased risk of flooding.

- Tourism employment and income declined.

- Rice seed ruined, causing food shortage and income loss.

What were the immediate responses to the Nepal earthquake?

- India and China provided over $1 billion of international aid .

- Over 100 search and rescue responders, medics and disaster and rescue experts were provided by The UK, along with three Chinook helicopters for use by the Nepali government.

- The GIS tool “Crisis mapping” was used to coordinate the response.

- Aid workers from charities such as the Red Cross came to help.

- Temporary housing was provided, including a ‘Tent city’ in Kathmandu.

- Search and rescue teams, and water and medical support arrived quickly from China, the UK and India.

- Half a million tents were provided to shelter the homeless.

- Helicopters rescued people caught in avalanches on Mount Everest and delivered aid to villages cut off by landslides.

- Field hospitals were set up to take pressure off hospitals.

- Three hundred thousand people migrated from Kathmandu to seek shelter and support from friends and family.

- Facebook launched a safety feature for users to indicate they were safe.

What were the long-term responses to the Nepal earthquake?

- A $3 million grant was provided by The Asian Development Bank (ADB) for immediate relief efforts and up to $200 million for the first phase of rehabilitation.

- Many countries donated aid. £73 million was donated by the UK (£23 million by the government and £50 million by the public). In addition to this, the UK provided 30 tonnes of humanitarian aid and eight tonnes of equipment.

- Landslides were cleared, and roads were repaired.

- Lakes that formed behind rivers damned by landslides were drained to avoid flooding.

- Stricter building codes were introduced.

- Thousands of homeless people were rehoused, and damaged homes were repaired.

- Over 7000 schools were rebuilt.

- Repairs were made to Everest base camp and trekking routes – by August 2015, new routes were established, and the government reopened the mountain to tourists.

- A blockade at the Indian border was cleared in late 2015, allowing better movement of fuels, medicines and construction materials.

Premium Resources

Please support internet geography.

If you've found the resources on this page useful please consider making a secure donation via PayPal to support the development of the site. The site is self-funded and your support is really appreciated.

Related Topics

Use the images below to explore related GeoTopics.

Previous Topic Page

Topic home, amatrice earthquake case study, share this:.

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

If you've found the resources on this site useful please consider making a secure donation via PayPal to support the development of the site. The site is self-funded and your support is really appreciated.

Search Internet Geography

Top posts and pages.

Latest Blog Entries

Pin It on Pinterest

- Click to share

- Print Friendly

Results for case study translation from English to Nepali

Human contributions.

From professional translators, enterprises, web pages and freely available translation repositories.

Add a translation

मामला अध्ययन

Last Update: 2018-12-11 Usage Frequency: 1 Quality: Reference: Anonymous

Last Update: 2021-05-12 Usage Frequency: 1 Quality: Reference: Anonymous

case study example

Last Update: 2021-02-09 Usage Frequency: 1 Quality: Reference: Anonymous

Last Update: 2019-10-24 Usage Frequency: 1 Quality: Reference: Anonymous

epidemiologic study

रसद व्यवस्थापन

Last Update: 2020-03-15 Usage Frequency: 1 Quality: Reference: Anonymous

केस प्रयोग गर्नुहोस्

Last Update: 2014-08-20 Usage Frequency: 4 Quality: Reference: Anonymous

case sensitive

केस सम्वेदनशील

Last Update: 2014-08-20 Usage Frequency: 5 Quality: Reference: Anonymous

change case...

à¤à¤² à¤à¥à¤¸à¤¾à¤à¤¨à¥à¤¹à¥à¤¸à¥

Last Update: 2011-10-23 Usage Frequency: 1 Quality: Reference: Anonymous

& title case

Last Update: 2011-10-23 Usage Frequency: 1 Quality: Reference: Anonymous Warning: Contains invisible HTML formatting

polycystic ovary syndrome: a case control study

polycystic अंडाकार सिंड्रोम: एक मामला नियंत्रण अध्ययन

Last Update: 2018-08-10 Usage Frequency: 1 Quality: Reference: Anonymous

case study hr shortge in the nepales construction industry

नेप्लेस निर्माण उद्योगमा केस स्टडी एचआर छोटो

Last Update: 2021-06-25 Usage Frequency: 1 Quality: Reference: Anonymous

c_hange case

परिवर्तित रेखा

Last Update: 2014-08-20 Usage Frequency: 1 Quality: Reference: Anonymous

business studies

व्यापार अध्ययन

Last Update: 2022-09-20 Usage Frequency: 1 Quality: Reference: Anonymous

Get a better translation with 7,712,660,171 human contributions

Users are now asking for help:.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Glob Ment Health (Camb)

Culture and mental health in Nepal: an interdisciplinary scoping review

L. e. chase.

1 McGill University - Global Mental Health Program, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

R. P. Sapkota

2 Division of Social and Transcultural Psychiatry, McGill University, Montreal, Canada

3 Integrated Program in Neuroscience, McGill University, Montreal, Canada

L. J. Kirmayer

Efforts to address global mental health disparities have given new urgency to longstanding debates on the relevance of cultural variations in the experience and expression of distress for the design and delivery of effective services. This scoping review examines available information on culture and mental health in Nepal, a low-income country with a four-decade history of humanitarian mental health intervention. Structured searches were performed using PsycINFO, Web of Science, Medline, and Proquest Dissertation for relevant book chapters, doctoral theses, and journal articles published up to May 2017. A total of 38 publications met inclusion criteria (nine published since 2015). Publications represented a range of disciplines, including anthropology, sociology, cultural psychiatry, and psychology and explored culture in relation to mental health in four broad areas: (1) cultural determinants of mental illness; (2) beliefs and values that shape illness experience, including symptom experience and expression and help-seeking; (3) cultural knowledge of mental health and healing practices; and (4) culturally informed mental health research and service design. The review identified divergent approaches to understanding and addressing mental health problems. Results can inform the development of mental health systems and services in Nepal as well as international efforts to integrate attention to culture in global mental health.

Introduction

While mental health problems are increasingly recognized as a global health priority, debate continues over the relevance of cultural variation for the application of psychiatric diagnoses and treatments (Chisholm et al . 2007 ; Collins et al . 2011 ; Patel et al . 2011 ; Whitley, 2015 ). This debate has taken on renewed importance with recent calls by global mental health advocates for rapid scale-up of mental health services in low- and middle-income countries (Patel et al . 2011 , 2016 ; Bhugra et al . 2017 ). Cultural and contextual factors are now understood to influence every aspect of mental health and illness (Alarcón et al . 2009 ; Kirmayer, 2013 ; Napier et al . 2014 ). Diagnostic and treatment guidelines and frameworks for mental health systems recognize cultural variation in the manifestation of distress and disorders and call for culturally appropriate interventions (Psychosocial Working Group, 2003 ; Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), 2007 ; American Psychiatric Association, 2013 ; World Health Organization, 2013 b ; Khenti et al . 2016 ).

Yet critics have pointed to a gap between the rhetoric of global mental health, which recognizes the importance of social and cultural context, and practice, in which local knowledge is often overlooked in favor of a generic biomedical psychiatric or psychosocial approach (Watters, 2010 ; Campbell & Burgess, 2012 ; Summerfield, 2012 ; Clark, 2014 ; Fernando, 2014 ; Mills, 2014 ; Bracken et al . 2016 ). There is continued concern over whether methods of research, diagnosis, and treatment that have been developed primarily in urban, high-income, and industrialized settings will meet the needs of populations in which the greatest mental health disparities are found. Failure to adequately address social and cultural contexts may limit the effectiveness of interventions and have other negative impacts, including promoting the medicalization of social suffering and undermining indigenous knowledge and support systems (Desjarlais et al . 1995 ; Argenti-Pillen, 2003 ; Clark, 2014 ; Whitley, 2015 ). The literatures of medical anthropology and sociology contain rich descriptions of many settings where global mental health is active; however, the generalizability of these accounts and their relevance to current mental health issues are not always clear to practitioners (Greene et al . 2017 ).

Nepal offers a useful case study in this discussion because it has seen many decades of social science research and there is a current need for information to guide ongoing efforts to scale up mental health services. A small landlocked country of about 29 million people with the third lowest human development rating in South Asia (United Nations Development Programme, 2016 ), Nepal has about 110 psychiatrists, 15 clinical psychologists, and 400–500 paraprofessional psychosocial workers (Luitel et al . 2015 ; Sherchan et al . 2017 ). Government investment in mental health in Nepal has historically been very limited (around 0.7% of the health budget), with more than half of available services provided by non-governmental organizations (NGOs) [World Health Organization (WHO), 2011 ; Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Reference Group for Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings, 2015 ].

The development of formal mental health services in Nepal has been led by an array of local and international humanitarian actors over the past four decades. The WHO began mental health work in Nepal in 1980 and the United Mission to Nepal launched the first community mental health services in 1984 (Acland, 2002 ). The first mental health NGOs were established in the 1990s to treat those affected by the ongoing Maoist insurgency and the mass influx of refugees from Bhutan (Jordans & Sharma, 2004 ; Tol et al. 2005 ; Jordans et al . 2007 ; Center for Victims of Torture Nepal, 2011 ). With the end of the civil conflict in 2006, mental health NGOs and advocates shifted their focus to strengthening the mental health system (Upadhaya et al . 2014 ). Nepal became an implementation site for several high-profile global mental health projects (Hanlon et al . 2014 ; Mendenhall et al . 2014 ; Kohrt et al . 2015 ; Jordans et al . 2016 ). In 2015, Nepal was struck by a major earthquake, inspiring a proliferation of mental health and psychosocial projects (Seale-Feldman & Upadhaya, 2015 ). The financial resources and political will elicited by the disaster contributed to advancing national global mental health agendas (Chase et al . 2018 ).

While Nepal has been a popular site for research on social, cultural, and ritual aspects of healing, few attempts have been made to consolidate this body of work or explore its relevance to ongoing health development initiatives. A desk review published shortly after the 2015 earthquake drew attention to existing literature on cultural aspects of mental health in Nepal (IASC Reference Group for Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings, 2015 ). However, this review was not conducted with the methodological rigor of a scholarly report and did not capture publications produced during the period of heightened interest and investment in mental health following the disaster. The present scoping review, completed 2 years after the earthquake, takes stock of the current state of scholarship on culture and mental health in Nepal, including relevant literature from across the health and social sciences.

We employed a scoping review methodology (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005 ) with the guiding research question: ‘What knowledge exists on the relationship between culture and mental health in Nepal?’ For the purposes of this review, mental health was interpreted as encompassing mental health/wellbeing and mental illness/disorder, where ‘psychiatric’, ‘psychological’, and ‘psychosocial’ were acceptable replacements for ‘mental’. Culture was interpreted as ‘values, beliefs, knowledge, norms, and practices and the notion that these are shared among a specific set of people’ (Hruschka & Hadley, 2008 , p. 947). Publications addressing social and structural issues that exist in many societies (e.g. gender inequality and mental health stigma) that were not explicitly linked to Nepali culture in some way were excluded. Publications addressing culture among ethnic minority groups in Nepal and ethnically Nepali Bhutanese refugees were included, while those focused exclusively on populations living outside Nepal were excluded.

Searches were carried out in collaboration with a medical librarian in PsycINFO, Web of Science, Medline, and Proquest Dissertation. Terms used to study mental health and illness in both social science (e.g. ‘healing’) and clinical (e.g. ‘treatment’) fields were included, as were transliterated Nepali words commonly referenced in the mental health literature [e.g. sato , meaning ‘spirit or soul’ as used in the Nepali idiom ‘soul loss’ (see Kohrt & Hruschka, 2010 ); chhopne , literally ‘to catch, to get hold of, and to cover by someone or something’, used to describe experiences of dissociation or possession (Sapkota et al . 2014 , p. 645); NB: definitions may vary according to the context and ethnic/linguistic group]. The following search terms were used in all databases: (Mental* OR Madness OR Psycholog* OR Distress* OR Idioms* OR Caus* OR Cultur* OR Belief* OR help seeking OR Healing OR Somatic* OR Possession OR Soul* OR Spirit* OR Sato* OR Rog* OR Dokh OR Psychosocial* OR Counsel* OR Witch* OR Ritual OR Chhopne OR Ethno* OR Festival OR Treatment) AND Nepal*. Texts published up to 22 May 2017, when the searches were completed, were included in this review.

Results from the searches were screened according to the following inclusion criteria: (1) English or Nepali; (2) peer-reviewed journal article, book/book chapter, or doctoral thesis; and (3) substantial original discussion of culture in relation to mental health in Nepal. Initial screening of titles and abstracts was carried out by bilingual (English/Nepali) team members with graduate training in transcultural psychiatry. All full texts of publications appearing to meet criteria were then screened by two team members. When there was disagreement among reviewers on whether a publication met inclusion criteria, additional coauthors reviewed the full text and consensus was reached through discussion. Additional items were identified by screening the reference lists of all included texts, the aforementioned desk review (IASC Reference Group for Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings, 2015 ), and a bibliography of psychological research in Nepal (Maharjan, 2012 ).

Texts meeting inclusion criteria were divided among team members for ‘charting’ (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005 ): key information was extracted using a form covering methods, focus, and key findings; reviewers also indicated whether the text reflected an applied orientation, defined as including discussion of how findings could inform or improve mental health services for culturally Nepali populations. Finally, texts were collated and summarized (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005 ) by the first author with input from other team members.

The search yielded 6488 results, of which 38 met inclusion criteria (see Fig. 1 and Table 1 for an overview of the search process and included texts). To facilitate practical use of this review, we have collated publications into four thematic categories.

Search strategy.

Overview of texts included in the review

(1) Cultural determinants of mental health problems

Six publications addressed how culture influences the etiology of mental distress and disorder, in particular by shaping patterns of social organization and inequality. Kohrt et al . ( 2009 ) examined the correlation between low caste and rates of depression and anxiety, identifying poverty, lack of social support, and stressful life events as mediators. In a related article, Kohrt ( 2009 ) interpreted associations between low caste and psychological morbidity though a policy analysis, highlighting the role of restrictions in social life and access to resources that affect low caste groups in the Nepali context. A book chapter by Jack et al . ( 2010 ) described how traditional Hindu Brahmanical models of the ‘good woman’ may lead to self-silencing and consequently contribute to depression among women in Nepal. Similarly, Kohrt & Bourey ( 2016 ) explored how cultural norms related to gender (e.g. perceived lack of autonomy, lack of social support for women leaving a marriage) contribute to the risk for comorbid maternal mental illness by influencing exposure to intimate partner violence.

Two articles considered how cultural values contribute to the development of mental health problems. Furr's ( 2005 ) sociological study found that ‘Western orientation’, as measured through a self-developed questionnaire assessing attitudes toward gender and caste norms and language/media preferences, was associated with lower depression scores. In a comparative study, Boehnke et al . ( 1998 ) found that Asian samples (Nepali and Fijian) valued tradition, conformity, and power more highly than Europeans (German) and had more microsocial (personal) than macrosocial (e.g. national or environmental) worries. In Nepal, microsocial worries were negatively related to mental wellbeing, but there was no direct relationship between cultural values and wellbeing.

(2) Culture and mental illness experience

A second set of 14 publications framed culture as a set of beliefs and values that shape mental illness experience. Several focused specifically on the ways that mental health problems manifest or are expressed in Nepali cultural contexts. Sharma & van Ommeren ( 1998 ) identified salient ‘idioms of distress’ (Nichter, 1981 ) among Bhutanese refugee torture survivors, including emotion-related idioms (e.g. dukha lāgyo or sadness) and somatic idioms (e.g. headache, dizziness); many attributed their suffering to bad deeds committed in previous lives ( karmako phal ). Hoge et al . ( 2006 ) found that Nepalis with generalized anxiety disorder showed more somatic symptoms and fewer psychological symptoms compared with Americans and offered possible explanations related to cultural differences in stigma, mind–body distinctions, introspection, and acceptable means of expressing distress. By contrast, Kohrt et al .’s ( 2005 ) work on jhum-jhum (a common somatic complaint in Nepal involving numbness or tingling) among depressed patients found that once the local burden of physical illness had been accounted for, rates of somatization in Nepal were comparable to those in Western settings.

Five studies explored how culture mediates the interpretation of particular symptoms and behaviors as deviant or pathological. Furr ( 2004 ) found that teachers with a more ‘Western’ orientation according to the aforementioned measure (Furr, 2005 ) were more likely to pathologize deviant child behavior. Adhikari et al . ( 2015 ) identified behaviors commonly reported as problematic among children in Nepal (e.g. addiction, negligence of studies, anger); these were mainly attributed to the social environment and intervention strategies ranged from talking to physical punishment. Burkey et al . ( 2016 b ) identified local social goals and gender norms that influenced when specific child behaviors were deemed pathological. Heys et al .’s ( 2017 ) study of Nepali understandings of autism identified beliefs that could interfere with help-seeking, especially attributions to poor parenting. Finally, Kim et al . ( 2017 ) examined which manifestations of grief among Nepali widows were locally considered pathological, finding some overlap with criteria for persistent complex bereavement disorder (e.g. prolonged duration, role/identity confusion, impaired daily functioning, mistrust).

More generally, Böker ( 1992 ) explored concepts of mental illness among mental hospital patients (likely suffering from severe/psychotic disorders) and their relatives. Most attributed the illness to spirit possession, physical problems in the body, fever, and separation or conflicts within the family. Pach III's ( 1998 ) book chapter explored Nepali villagers’ perceptions of individuals described as being baulāhā (mad), finding that afflicted individuals experienced social marginality that constrained their access to care and was at times more distressing than the illness itself. Kaplan's ( 1999 ) doctoral thesis explored the meaning of psychiatric symptomatology in rural Nepal, including common supernatural attributions (e.g. witchcraft, the intervention of ghosts and spirits), as well as treatment modalities believed to address these causes. Clarke et al . ( 2014 ) studied Nepali mothers’ concepts of psychological distress; distress was often attributed to family- and gender-related factors and women's responses to it were shaped by a fatalistic worldview.

Finally, two publications addressed indigenous illness categories. Sapkota et al . ( 2014 ) examined mental health factors associated with unintentional spirit possession. They argue that rather than mapping onto a single diagnostic category, spirit possession may function as an idiom of distress facilitating expression of ‘suffering related to mental illness, socio-political violence, traumatic events, and the oppression of women’ (p. 643). Evers et al . ( 2016 ) used the case of ‘soul loss’ in the wake of Nepal's civil conflict to illustrate how socially and spiritually anchored conceptions of the self influence the experience of psychopathology and the course of healing.

(3) Cultural knowledge of mental health and healing

A third set of 11 publications explored cultural knowledge on mental health and healing in Nepal. Several of these document aspects of Nepali ‘ethnopsychology’, or ‘cultural concepts of self, mind-body divisions, emotions, human nature, motivation, and personality’ (Kohrt & Maharjan, 2009 , p. 115). Kohrt & Harper ( 2008 ) elaborated elements of self that are ‘central to understanding conceptions of mental health and psychological wellbeing and subsequent stigma’ (p. 468) in Nepal, including the soul, heart–mind, brain–mind, body, and social status. In a 2009 publication, Kohrt and Maharjan provided an overview of Nepali concepts of child development and the perceived effects of violence and psychological trauma. Kohrt & Hruschka ( 2010 ) explored Nepali concepts of psychological trauma and associated idioms of distress and emotion terms. They highlight how the attribution of traumatic experiences to one's actions in a past or present life ( karma ) can lead to blame and stigma, with implications for help-seeking.

Three studies explored cultural concepts of and pathways to wellbeing. Bragin et al . ( 2014 ) identified locally salient domains of wellbeing in three conflict-affected countries (including, specific to Nepal, having all basic needs met and freedom of movement) and describe the influence of spiritual traditions on understanding wellbeing, evident in the use of terms such as ānanda (transcendent bliss). Chase & Bhattarai ( 2013 ) explored resilience among Bhutanese refugees in the USA and Nepal; they present idioms of wellbeing and describe processes that promote resilience, such as daily worship ( pūjā ) and involvement in community groups. Finally, a book chapter by Kohrt ( 2015 ) describes how the practice of certain Nepali traditional rituals can promote psychosocial wellbeing, particularly during reintegration of child soldiers. For example, Swasthāni , a fasting ritual performed by women for the wellbeing of male relatives and atonement of sins, may lead to increased acceptance of girl soldiers.

Several publications addressed expert or esoteric cultural knowledge – that of practitioners of indigenous healing systems. Peters’ article (1978) and subsequent book (1981) on the Tamang ethnic group draws parallels between techniques used by shamans and those of Western psychotherapy, including mediation in social conflict, facilitation of catharsis, and providing a symbolic structure for understanding illness. Skultans ( 1988 ) compared the practice of a psychiatric outpatient clinic with that of a ‘tāntrik healer’ – a type of healer known for ‘sweeping away the negative forces believed to account for ill health or misfortune, and blowing on the positive and regenerative forces in their place’ ( jhar-phuk ; Dietrich, 1998 , p. ix). The healer had adopted elements of psychiatric practice (e.g. speed and standardization) but offered causal attributions that were more likely to reinforce family support. Soubrouillard's doctoral thesis (1995) explored how Nepali shamans understand, assess, attribute and treat madness; diagnostic methods including divination are described in detail. Finally, Jolly ( 1999 ) described how a Nepali soldier in the British army was cured of psychiatric symptoms by visiting a traditional healer, noting parallels with the practice of mental health professionals. The study by Böker ( 1992 ) described above also discusses treatment-seeking pathways, including preferences for traditional healers.

(4) Culturally informed mental health care

Finally, six publications explored how attention to culture can be integrated into the detection and treatment of mental health problems. With regard to detection, Kohrt et al . ( 2011 ) proposed six evaluation questions to guide cross-cultural validation of instruments for child mental health research. Using the examples of the Depression Self-Rating Scale (DSRS) and Child PTSD Symptom Scale (CPSS), they demonstrate how these questions can guide effective translation of instruments by trained mental health paraprofessionals and discuss adaptations made (e.g. incorporation of pictographic scales). Kohrt et al . ( 2016 ) adapted the PHQ-9 for use in Nepal, developed two additional questions based on local idioms of distress, and validated these among primary care patients. They determined that an algorithm involving initial screening for heart–mind problems and impaired functioning could improve the efficiency and accuracy of screening with PHQ-9. Burkey et al . ( 2016 a ) explored the overlap between local categories of problematic behavior and Western diagnostic criteria as reflected in the Disruptive Behavior international Scale-Nepal version (DBIS).

With regard to treatment, Harper's ( 2014 ) book chapter examined how United Mission to Nepal introduced psychiatric services and psychotropic drugs in Nepal, describing how diagnostic procedures were adapted to the local cultural context; for example, the label of ‘nerves disease’ ( nasā rog ) was used to make depression treatment more socially acceptable. Jordans et al . ( 2003 ) described cultural adaptations made by the Centre for Victims of Torture, Nepal (CVICT; see also Sharma & van Ommeren, 1998 ) in training psychosocial counsellors, including demonstrating respect for clients’ social status, applying indirect ways of questioning, and specialized training modules focused on stigmatization and supernatural attributions. Tol et al. ( 2005 ) outlined some ‘cultural challenges’ CVICT faced in establishing psychosocial counselling in Nepal, as well as adaptations made to address issues related to the therapeutic relationship, illness beliefs, locus of control, and views of the self and introspection. Finally, Kohrt et al . ( 2012 ) discuss possible adaptations to cognitive behavior therapy, interpersonal therapy, and dialectical behavior therapy to accommodate Nepali ethnopsychology, with the goal of improving care of Bhutanese refugees.

This scoping review identified a modest body of literature on culture and mental health in Nepal. Publications represented a range of disciplines and research methods. Culture was investigated variously as a contributor to mental illness, a set of beliefs and values that shape mental illness experience and help-seeking, a repository of indigenous knowledge about mental health, and a factor that could be effectively integrated in mental health research and service design. Much of the literature in this area published before 2015 was synthesized in the post-earthquake desk review (IASC Reference Group for Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings, 2015 ). However, it is striking that nearly 25% of identified texts were published since the beginning of 2015. This may reflect growing interest in the critical role of social context in mental health and illness (Tol et al. 2010 ) as well as the increased attention to mental health issues occasioned by disasters (World Health Organization, 2013 a ).

Nearly 75% of included publications reflected an applied orientation. Many of these were published within the past 15 years by researchers affiliated with Nepali mental health NGOs. Some applied work strived to directly integrate culture into mental health research and practice with the goal of improving quality of and access to services. Other studies conducted in affiliation with these NGOs adopted a broader focus, contributing to our understanding of Nepali concepts of distress, pathology, trauma, child development, and resilience.

At the same time, we noted that applied research (with a few important exceptions such as the work on ethnopsychology) tended to be structured around concepts emerging from globalized psychiatric knowledge, with accounts of culture often reduced to one or two dimensions that shaped or interfered with conventional methods of research and practice. Only three studies were framed around indigenous illness categories (Kohrt et al . 2005 ; Sapkota et al . 2014 ; Evers et al . 2016 ). All of the included research on traditional healing was conducted prior to the year 2000, despite the fact that these healers continue to be the primary source of treatment for mental health problems in Nepal (Luitel et al . 2015 ). In some cases, narrow and essentializing conceptualizations of ‘Nepali culture’ were evident. For example, Furr ( 2004 , 2005 ) considered willingness to support female political leaders to be an indication of ‘Western’ (as opposed to ‘Nepali’) cultural orientation – yet, Nepal has now elected a female president well in advance of many Western countries. Moreover, there is evidence that cultural beliefs and idioms take on new meanings when instrumentalized within mental health diagnosis and service provision, raising questions about the limits of culturally adapted interventions (Abramowitz, 2010 ). There remains a need for long-term ethnographic research that examines local understandings and experiences of mental health problems. In addition to improving our understanding of the contexts and consequences of global mental health interventions, studies of this nature may shed light on underlying processes of psychopathology and intervention strategies grounded in local ethnopsychologies and indigenous healing systems that can contribute to a truly global psychiatry (Chase & Sapkota, 2017 ).

The body of literature outlined here can and should inform mental health policy and practice in Nepal (Kirmayer & Pedersen, 2014 ). This review comes at a critical historical moment: Nepal's government has allocated a budget for mental health care at the district level for the first time, revised mental health policy is pending after 20 years, and the Ministry of Health has demonstrated a commitment to addressing mental health in the context of its action against non-communicable diseases (Chase et al . 2018 ; Government of Nepal, 2014 ). Findings may be relevant to a range of stakeholders involved in the anticipated scaling up of services. The national baseline psychiatric epidemiological study that is currently being planned may use instruments described here that have undergone a culturally informed validation process. The wealth of information identified in this review about idioms of distress, concepts of causality, and indigenous illness categories could enhance the assessment of mental health problems, and should thus inform future revisions of the Standard Treatment Protocol for mental health in primary care as well as efforts to improve and contextualize medical school curricula on mental health and mhGAP-based trainings for physicians. Clinicians working in Nepal should consider incorporating the cultural adaptations to psychological and psychosocial treatments documented above.

One possible barrier to the application of research findings is disciplinary variation in jargon and writing conventions; social scientists seeking to inform practitioners should consider publishing versions of their findings in clear accessible language (Greene et al . 2017 ). Working in collaboration with patients, clinicians, policy makers and other knowledge users may help researchers find the appropriate vocabulary to translate their findings into practical applications. The recent development of a ‘community informant detection tool’ in Nepal (Subba et al . 2017 ; published shortly after our review) offers an excellent model for collaborative, culturally informed mental health work of this nature.

Finally, it is noteworthy that only three included publications had a Nepali first author. The small number of Nepali scholars who have published in this area has implications for the peer review process, as relying mainly on non-Nepali reviewers could result in the dissemination of limited or misleading interpretations of local terms and perspectives. Findings of this review thus lend support to calls for greater representation of scholars from low-income countries in the global mental health literature (Kohrt et al . 2014 ).

Limitations

This scoping review has several limitations. Nepali language search terms could have been transliterated in multiple ways and we did not include search terms in Devanagari script. Following Arskey & O'Malley ( 2005 ), this study did not assess the quality of included texts; caution is therefore needed in applying findings. In addition to considering information summarized in Table 1 , readers should refer to the full texts of publications. Our stringent inclusion criteria may have led to the exclusion of some relevant literature. Some potentially relevant work on emotions, coping, and self-hood that did not make an explicit link to mental health and illness was excluded (e.g. Mchugh, 1989 ; Cole & Tamang, 1998 ; Cole et al . 2002 ; Chase et al . 2013 ). Some instrument validation studies that did not meet the criterion of ‘substantial original discussion’ of culture and mental health did make references to the culture and context and may be relevant for researchers planning to use these scales in Nepal (e.g. Kohrt et al . 2002 , 2003 ; Haroz et al . 2017 ; Sochos & Lokshum, 2017 ; see Chen et al . 2013 for more on psychiatric scales used in Nepal). We recommend that all future studies reporting successful cross-cultural validation of instruments describe the translation process and adaptations made in detail. Finally, we note the exclusion of a rich body of ethnographic literature that explores suffering and healing in local Nepali terms, without employing the language of mental health and illness (e.g. Hitchcock, 1967 ; Hitchcock & Jones, 1976 ; Stone, 1976 ; Desjarlais, 1989 , 1992 ; Maskarinec, 1992 ; Subba, 2007 ). More work is needed on ways to integrate this rich body of contextual knowledge in global mental health programs.

We identified 38 papers, book chapters and monographs that explicitly addressed cultural dimensions of mental health and illness in Nepal. As documentation of four decades of work focused on translating among divergent approaches to understanding and addressing mental suffering, this review speaks to ongoing debates about the significance of cultural variation in psychiatric distress and disorder. Although still modest, the available literature on Nepal does not support claims that service development initiatives have completely overlooked local cultures. On the contrary, applied work done by a new generation of clinician–researchers with interdisciplinary interests and training is refining our knowledge of how culture shapes the experience, expression, and interpretation of suffering and the translatability of biomedical diagnostic categories and treatments. While this review does not speak to how well available knowledge has been applied at the level of health systems or service delivery, it suggests there is a growing interest in culturally informed mental health research and practice in Nepal. At the same time, findings suggest that applied research geared toward mental health service development still needs to engage with long-term, ethnographic studies that attend holistically to local knowledge and experience. Gaps remain in our understanding of indigenous illness concepts and healing approaches. There is a continued need to build capacity in Nepal for research driven by the needs and concerns of local stakeholders, particularly people with mental health problems and traditional healers, and to engage with open-ended methods of inquiry that recognize diverse modes of understanding mental suffering and healing.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr Danielle Groleau who provided mentorship to the second author during early stages of planning and carrying out searches. We would like to thank Teodora Constantinescu, medical librarian at the Institute of Community & Family Psychiatry, Jewish General Hospital, Montreal Canada, for help in conducting searches. We are further thankful to four anonymous reviewers for Global Mental Health , whose input led to important improvements.

Financial support

This project was supported by the McGill Global Mental Health Program ( www.mcgill.ca/gmh ).

Conflict of interest

Ethical standards.

Not applicable.

- Abramowitz SA (2010). Trauma and humanitarian translation in Liberia: the tale of Open Mole . Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 34 , 353–379. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Acland S (2002). Mental health services in primary care: the case of Nepal In The World Mental Health Casebook: Social and Mental Health Programs in Low-Income Countries (ed. Cohen A., Kleinman A., Saraceno B.), pp. 121–152. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Press: New York. [ Google Scholar ]

- Adhikari RP, Upadhaya N, Gurung D, Luitel NP, Burkey MD, Kohrt BA, Jordans MJD (2015). Perceived behavioral problems of school aged children in rural Nepal: a qualitative study . Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health 9 , 1–9. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Alarcón RD, Becker AE, Lewis-Fernández R, Like RC, Desai P, Foulks E, Gonzales J, Hansen H, Kopelowicz A, Lu FG, Oquendo MA, Primm A (2009). Issues for DSM-V: the role of culture in psychiatric diagnosis . The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 197 , 559–660. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders , 5th edn American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC. [ Google Scholar ]

- Argenti-Pillen A (2003). Masking Terror: How Women Contain Violence in Southern Sri Lanka . University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia. [ Google Scholar ]

- Arksey H, O'Malley L (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework . International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 , 19–32. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bhugra D, Tasman A, Pathare S, Priebe S, Smith S, Torous J, Arbuckle MR, Langford A, Alarcón RD, Chiu HFK, First MB, Kay J, Sunkel C, Thapar A, Udomratn P, Baingana FK, Kestel D, Ng RMK, Patel A, De Picker L, McKenzie KJ, Moussaoui D, Muijen M, Bartlett P, Davison S, Exworthy T, Loza N, Rose D, Torales J, Brown M, Christensen H, Firth J, Keshavan M, Li A, Onnela JP, Wykes T, Elkholy H, Kalra G, Lovett KF, Travis MJ, Ventriglio A (2017). The WPA-Lancet Psychiatry Commission on the future of psychiatry . The Lancet Psychiatry 4 , 775–818. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Boehnke K, Stromberg C, Regmi MP, Richmond BO, Chandra S (1998). Reflecting the world ‘out there’: a cross-cultural perspective on worries, values and well-being . Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 17 , 227–247. [ Google Scholar ]

- Böker H (1992). Concepts of mental illness: an ethnopsychiatric study of the mental hospital's in- and out-patients in the Kathmandu Valley . Contributions to Nepalese Studies 19 , 27–50. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bracken P, Giller J, Summerfield D (2016). Primum non nocere. The case for a critical approach to global mental health . Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 25 , 506–510. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bragin M, Onta K, Nzeyimana G (2014). To be well at heart: women's perceptions of psychosocial well- being in 3 conflict-affected countries – Burundi, Nepal, and Uganda . Intervention 12 , 187–209. [ Google Scholar ]

- Burkey MD, Ghimire L, Adhikari RP, Kohrt BA, Jordans MJD, Haroz EE, Wissow LS (2016 a ). Development process of an assessment tool for disruptive behavior problems in cross-cultural settings: the Disruptive Behavior International Scale – Nepal version (DBIS-N) . International Journal of Culture and Mental Health 9 , 387–398. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Burkey MD, Ghimire L, Adhikari RP, Wissow LS, Jordans MJD, Kohrt BA (2016 b ). The ecocultural context and child behavior problems: a qualitative analysis in rural Nepal . Social Science & Medicine 159 , 73–82. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Campbell C, Burgess R (2012). The role of communities in advancing the goals of the Movement for Global Mental Health . Transcultural Psychiatry 49 , 379–395. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Center for Victims of Torture Nepal (2011). Community Mental Health Promotion Program in Nepal . Kathmandu. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chase LE, Bhattarai D (2013). Making Peace In The Heart-Mind: towards an ethnopsychology of resilience among Bhutanese refugees . European Bulletin of Himalayan Research 43 , 144–166. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chase LE, Marahatta K, Sidgel K, Shrestha S, Gautam K, Luitel N, Dotel BR, Samuel R (2018). Building back better? Taking stock of the post-earthquake mental health and psychosocial response in Nepal . International Journal of Mental Health Systems 12 , 1–12. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chase L, Sapkota RP (2017). ‘In our community, a friend is a psychologist’: an ethnographic study of informal care in two Bhutanese refugee communities . Transcultural Psychiatry 54 , 400–422. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chase LE, Welton-Mitchell C, Bhattarai S (2013). ‘Solving tension:’ coping among Bhutanese refugees in Nepal . International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care 9 , 71–83. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen P, Ganesan S, Mckenna M (2013). Overview of psychiatric scales used in Nepal: their reliability, validity and cultural appropriateness . Asia-Pacific Psychiatry 5 , 113–118. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chisholm D, Flisher A, Lund C, Patel V, Saxena S, Thornicroft G, Tomlinson M (2007). Scale up services for mental disorders: a call for action . The Lancet 370 , 1241–1252. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Clark J (2014). Medicalization of global health 2: the medicalization of global mental health . Global Health Action 7 1, 24000, DOI: 10.3402/gha.v7.24000 Available from: 10.3402/gha.v7.24000. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Clarke K, Saville N, Bhandari B, Giri K, Ghising M, Jha M, Jha S, Magar J, Roy R, Shrestha B, Thakur B, Tiwari R, Costello A, Manandhar D, King M, Osrin D, Prost A (2014). Understanding psychological distress among mothers in rural Nepal: a qualitative grounded theory exploration . BMC Psychiatry 14 , 1–13. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/14/60 . [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cole PM, Bruschi CJ, Tamang BL (2002). Cultural differences in children's emotional reactions to difficult situations . Child Development 73 , 983–996. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cole PM, Tamang BL (1998). Nepali children's ideas about emotional displays in hypothetical challenges . Developmental Psychology 34 , 640–646. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Collins PY, Patel V, Joestl SS, March D, Insel TR, Daar AS (2011). Grand challenges in global mental health . Nature 475 , 27–30. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Desjarlais RR (1989). Healing through images: the magical flight and healing geography of Nepali shamans . Ethos (Berkeley, California ) 17 , 289–307. [ Google Scholar ]

- Desjarlais RR (1992). Body and Emotion: The Aesthetics of Illness and Healing in the Nepal Himalayas . University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia. [ Google Scholar ]

- Desjarlais R, Eisenberg L, Good B, Kleinman A (1995). World Mental Health: Problems and Priorities in Low-Income Countries . Oxford University Press: New York. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dietrich A (1998). Tantric Healing in the Kathmandu Valley: A Comparative Study of Hindu and Buddhist Spiritual Healing Traditions in Urban Nepalese Society . Book Faith India: Delhi. [ Google Scholar ]

- Evers S, Van Der Brug M, Van Wesel F, Krabbendam L, Amsterdam VU, Studies E, Amsterdam VU (2016). Mending the levee: how supernaturally anchored conceptions of the person impact on trauma perception and healing among children (cases from Madagascar and Nepal) . Children and Society 30 , 423–433. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fernando S (2014). Globalization of psychiatry – a barrier to mental health development . International Review of Psychiatry 26 , 551–557. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Furr LA (2004). Medicalization in Nepal: a study of the influence of westernization on defining deviant and illness behavior in a developing country . International Journal of Comparative Sociology 45 , 131–142. [ Google Scholar ]

- Furr LA (2005). On the relationship between cultural values and preferences and affective health in Nepal . International Journal of Social Psychiatry 51 , 71–82. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Government of Nepal (2014). Multisectoral Action Plan for the Prevention of Non Communicable Diseases (2014–2020) . Government of Nepal: Kathmandu. [ Google Scholar ]

- Greene MC, Jordans MJD, Kohrt BA, Ventevogel P, Kirmayer LJ, Hassan G, Chiumento A, van Ommeren M, Tol WA (2017). Addressing culture and context in humanitarian response: preparing desk reviews to inform mental health and psychosocial support . Conflict and Health 11 , 1–10. DOI: 10.1186/s13031-017-0123-z. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hanlon C, Luitel NP, Kathree T, Murhar V, Shrivasta S, Medhin G, Ssebunnya J, Fekadu A, Shidhaye R, Petersen I, Jordans M, Kigozi F, Thornicroft G, Patel V, Tomlinson M, Lund C, Breuer E, De Silva M, Prince M (2014). Challenges and opportunities for implementing integrated mental health care: a district level situation analysis from five low- and middle-income countries . PLoS ONE 9 , e88437. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Haroz EE, Jordans M, de Jong J, Gross A, Bass J, Tol W (2017). Measuring hope among children affected by armed conflict: cross-cultural construct validity of the children's hope scale . Assessment 24 , 528–539. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Harper I (2014). Dealing with ‘multiple physical complaints’: introducing psychiatric services In Development and Public Health in the Himalaya: Reflections on Healing in Contemporary Nepal , pp. 83–102. Routledge: New York. [ Google Scholar ]

- Heys M, Alexander A, Medeiros E, Tumbahangphe KM, Gibbons F, Shrestha R, Manandhar M, Wickenden M, Shrestha M, Costello A, Manandhar D, Pellicano E (2017). Understanding parents' and professionals' knowledge and awareness of autism in Nepal . Autism 21 , 436–449. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hitchcock JT (1967). A Nepalese shamanism and the classic inner Asian tradition . History of Religions 7 , 149–158. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hitchcock JT, Jones RL (eds) (1976). Spirit Possession in the Nepal Himalayas . Aris & Phillips Ltd.: Warminster. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hoge EA, Tamrakar SM, Christian KM, Mahara N, Nepal MK, Pollack MH, Simon NM (2006). Cross-cultural differences in somatic presentation in patients with generalized anxiety disorder . Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease 194 , 962–966. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hruschka DJ, Hadley C. 2008. A glossary of culture in epidemiology . Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 62 , 947–951. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Inter-Agency Standing Committee (2007). IASC Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings . IASC: Geneva. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Reference Group for Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings (2015). Nepal Earthquakes 2015: Desk Review of Existing Information with Relevance to Mental Health & Psychosocial Support . Kathmandu, Nepal. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jack DC, Pokharel B, Subba U (2010). ‘I don't express my feelings to anyone’: how self-silencing relates to gender and depression in Nepal In Silencing the Self Across Cultures: Depression and Gender in the Social World (ed. Jack DC, Ali A), pp. 147–173. Oxford University Press: Oxford. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jolly A (1999). Indigenous mental health care among Gurkha soldiers based in the United Kingdom . Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps 145 , 15–17. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jordans MJ, Keen AS, Pradhan H, Tol WA (2007). Psychosocial counselling in Nepal: perspectives of counsellors and beneficiaries . International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling 29 , 57–68. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jordans MJD, Luitel NP, Pokhrel P, Patel V (2016). Development and pilot testing of a mental healthcare plan in Nepal . British Journal of Psychiatry 208 , s21–s28. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jordans MJD, Sharma B (2004). Integration of psychosocial counselling in care systems in Nepal . Intervention 2 , 171–180. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jordans MJD, Tol WA, Sharma B, van Ommeren M (2003). Training psychosocial counselling in Nepal: content review of a specialized training program . Intervention 1 , 18–35. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kaplan AS (1999). An Exploration of the Meaning of Psychiatric Symptomatology in Rural Nepal . Unpublished doctoral dissertation University of Hawaii: Honolulu, US. [ Google Scholar ]

- Khenti A, Fréel S, Trainor R, Mohamoud S, Diaz P, Suh E, Bobbili SJ, Sapag JC (2016). Developing a holistic policy and intervention framework for global mental health . Health Policy and Planning 31 , 37–45. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kim J, Tol WA, Shrestha A, Kafle HM, Rayamajhi R, Luitel NP, Thapa L, Surkan PJ (2017). Persistent complex bereavement disorder and culture: early and prolonged grief in Nepali widows . Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes 80 , 1–16. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kirmayer LJ (2013). 50 years of transcultural psychiatry . Transcultural Psychiatry 50 , 3–5. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kirmayer LJ, Pedersen D (2014). Toward a new architecture for global mental health . Transcultural Psychiatry 51 , 759–776. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kohrt BA (2009). Vulnerable social groups in postconflict settings: a mixed methods policy analysis and epidemiology study of caste and psychological morbidity in Nepal . Intervention 7 , 239–264. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kohrt BA (2015). The role of traditional rituals for reintegration and psychosocial well-being of child soldiers in Nepal In Genocide and Mass Violence (ed. Hinton DE, Hinton AL), pp. 369–387. Cambridge University Press: New York. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kohrt BA, Bourey C (2016). Culture and comorbidity: intimate partner violence as a common risk factor for maternal mental illness and reproductive health problems among former child soldiers in Nepal . Medical Anthropology Quarterly 30 , 515–535. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kohrt BA, Harper I (2008). Navigating diagnoses: understanding mind-body relations, mental health, and stigma in Nepal . Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 32 , 462–491. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kohrt BA, Hruschka DJ (2010). Nepali concepts of psychological trauma: the role of idioms of distress, ethnopsychology and ethnophysiology in alleviating suffering and preventing stigma . Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 34 , 322–352. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kohrt BS, Jordans MJ, Tol WA, Luitel NP, Maharjan SM, Upadhaya N (2011). Validation of cross-cultural child mental health and psychosocial research instruments: adapting the Depression Self-Rating Scale and Child PTSD Symptom Scale in Nepal . BMC Psychiatry 11 , 1–17. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kohrt BA, Kunz RD, Baldwin JL, Koirala NR, Sharma VD, Nepal MK (2005). ‘Somatization’ and ‘comorbidity’: a study of Jhum-Jhum and depression in rural Nepal . Ethos (Berkeley, California ) 33 , 125–147. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kohrt BA, Kunz RD, Koirala NR, Sharma VD (2003). Validation of the Nepali version of beck anxiety inventory . Journal of Institute of Medicine 25 , 1–4. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kohrt BA, Kunz RD, Koirala NR, Sharma VD, Nepal MK (2002). Validation of a Nepali version of the Beck Depression Inventory . Nepalese Journal of Psychiatry 2 , 123–130. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kohrt BA, Luitel NP, Acharya P, Jordans MJD (2016). Detection of depression in low resource settings: validation of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and cultural concepts of distress in Nepal . BMC Psychiatry 16 , 1–14. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kohrt BA, Maharjan SM (2009). When a child is no longer a child: Nepali ethnopsychology of child development and violence . Studies in Nepali History and Society 14 , 107–142. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kohrt BA, Maharjan SM, Timsina D, Griffith J (2012). Applying Nepali ethnopsychology to psychotherapy for the treatment of mental illness and prevention of suicide among Bhutanese refugees . Annals of Anthropological Practice 36 , 88–112. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kohrt BA, Ramaiya MK, Rai S, Bhardwaj A, Jordans MJD (2015). Development of a scoring system for non-specialist ratings of clinical competence in global mental health: a qualitative process evaluation of the Enhancing Assessment of Common Therapeutic Factors (ENACT) scale . Global Mental Health 2 , e23. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kohrt BA, Speckman RA, Kunz RD, Baldwin JL, Upadhaya N, Acharya NR, Sharma VD, Nepal MK, Worthman CM (2009). Culture in psychiatric epidemiology: using ethnography and multiple mediator models to assess the relationship of caste with depression and anxiety in Nepal . Annals of Human Biology 36 , 261–280. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kohrt BA, Upadhaya N, Luitel NP, Maharjan SM, Kaiser BN, Macfarlane EK, Khan N (2014). Authorship in global mental health research: recommendations for collaborative approaches to writing and publishing . Annals of Global Health 80 , 134–142. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Luitel NP, Jordans MJ, Adhikari A, Upadhaya N, Hanlon C, Lund C, Komproe IH (2015). Mental health care in Nepal: current situation and challenges for development of a district mental health care plan . Conflict and Health 9 , 1–11. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Maharjan SM (2012). Bibliography of Psychological Research in Nepal . Martin Chautari: Kathmandu. [ Google Scholar ]

- Maskarinec GG (1992). A shamanic etiology of affliction in Western Nepal . Social Science & Medicine 35 , 723–734. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mchugh E (1989). Concepts of the person among the Gurungs of Nepal . American Ethnologist 16 , 75–86. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mendenhall E, De Silva MJ, Hanlon C, Petersen I, Shidhaye R, Jordans M, Luitel N, Ssebunnya J, Fekadu A, Patel V, Tomlinson M, Lund C (2014). Acceptability and feasibility of using non-specialist health workers to deliver mental health care: stakeholder perceptions from the PRIME district sites in Ethiopia, India, Nepal, South Africa, and Uganda . Social Science & Medicine 118C , 33–42. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mills C (2014). Decolonizing Global Mental Health: The Psychiatrization of the Majority World . Routledge: New York. [ Google Scholar ]

- Napier AD, Ancarno C, Butler B, Calabrese J, Chater A, Chatterjee H, Guesnet F, Horne R, Jacyna S, Jadhav S, Macdonald A, Neuendorf U, Parkhurst A, Reynolds R, Scambler G, Shamdasani S, Smith SZ, Stougaard-Nielsen J, Thomson L, Tyler N, Volkmann A-M, Walker T, Watson J, de Williams ACC, Willott C, Wilson J, Woolf K (2014). Culture and health . The Lancet 384 , 1607–1639. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nichter M (1981). Idioms of distress: alternatives in the expression of psychosocial distress: a case study from South India . Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 5 , 379–408. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pach A III (1998). Narrative constructions of madness in a Hindu village in Nepal In Selves in Time and Place: Identities, Experience, and History in Nepal (ed. Skinner D, Pach A III, Holland D), pp. 111–128. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.: Lanham. [ Google Scholar ]

- Patel V, Chisholm D, Parikh R, Charlson FJ, Degenhardt L, Dua T, Ferrari AJ, Hyman S, Laxminarayan R, Levin C, Lund C, Medina Mora ME, Petersen I, Scott J, Shidhaye R, Vijayakumar L, Thornicroft G, Whiteford H (2016). Addressing the burden of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders: key messages from Disease Control Priorities, 3rd edition . The Lancet 387 , 1672–1685. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Patel V, Collins PY, Copeland J, Kakuma R, Katontoka S, Lamichhane J, Naik S, Skeen S (2011). The movement for global mental health . British Journal of Psychiatry 198 , 88–90. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Peters L (1978). Psychotherapy in Tamang shamanism . Ethos (Berkeley, California ) 6 , 63–91. [ Google Scholar ]

- Peters L (1981). Ecstasy and Healing in Nepal: An Ethnopsychiatric Study of Tamang Shamanism . Undena Publications: Malibu. [ Google Scholar ]

- Psychosocial Working Group (2003). Psychosocial Intervention in Complex Emergencies: A Conceptual Framework . Edinburgh. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sapkota R, Gurung D, Neupane D, Shah S, Kienzler H, Kirmayer LJ (2014). A village possessed by ‘witches’: a study of possession and common mental disorders in Nepal . Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 38 , 642–668. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Seale-Feldman A, Upadhaya N (2015). Mental Health after the Earthquake: Building Nepal's Mental Health System in Times of Emergency Hotspots, Cultural Anthropology Website, October 14 2015. Available from: https://culanth.org/fieldsights/736-mental-health-after-the-earthquake-building-nepal-s-mental-health-system-in-times-of-emergency .

- Sharma B, van Ommeren M (1998). Preventing torture and rehabilitating survivors in Nepal . Transcultural Psychiatry 35 , 85–97. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sherchan S, Samuel R, Marahatta K, Anwar N, Van Ommeren MH, Ofrin R (2017). Post-disaster mental health and psychosocial support: experience from the 2015 Nepal earthquake . WHO South-East Asia Journal of Public Health 6 , 22–29. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Skultans V (1988). A comparative study of the psychiatric practice of a tantrik healer and a hospital out-patient clinic in the Kathmandu Valley . Psychological Medicine 18 , 969–981. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sochos A, Lokshum C (2017). Adolescent attachment in Nepal: testing the factorial validity of two scales . European Journal of Developmental Psychology 14 , 498–508. [ Google Scholar ]

- Soubrouillard B (1995). A Psychological Study of the Vision and Treatment of Mental Illness by Nepalese Shamans . Unpublished doctoral dissertation Pacifica Graduate Institute: Carpinteria, USA. [ Google Scholar ]

- Stone L (1976). Concepts of illness and curing in a central Nepal village . Contributions to Nepalese Studies 3 , 54–82. [ Google Scholar ]

- Subba S (2007). Socio-Cultural Construction of Illness: Oral Recitals of Genesis, Causes and Cure of Roga (naturally caused illnesses) . Ms. Usha Kiran Subba: Kathmandu, Nepal: Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Shishir_Subba/publication/220024800_Sociocultural_Construction_of_Illness_Oral_Recitals_of_Genesis_Causes_and_Cure_of_Naturally_Caused_Illnesses/links/00463515716d542b08000000/Sociocultural-Construction-of-Illness-Oral-Recitals-of-Genesis-Causes-and-Cure-of-Naturally-Caused-Illnesses.pdf [ Google Scholar ]

- Subba P, Luitel NP, Kohrt BA, Jordans MJD (2017). Improving detection of mental health problems in community settings in Nepal: development and pilot testing of the community informant detection tool . Conflict and Health 11 , 28. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Summerfield D (2012). Afterword: against ‘global mental health’ . Transcultural Psychiatry 49 , 519–530. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tol WA, Jordans MJD, Regmi S, Sharma B (2005). Cultural challenges to psychosocial counselling in Nepal . Transcultural Psychiatry 42 , 317–333. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tol WA, Kohrt BA, Jordans MJD, Thapa SB, Pettigrew J, Upadhaya N, de Jong JTVM (2010). Political violence and mental health: a multi-disciplinary review of the literature on Nepal . Social Science & Medicine (1982) 70 , 35–44. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- United Nations Development Programme (2016). Human Development Report 2016 . United Nation Development Programme, New York. [ Google Scholar ]

- Upadhaya N, Luitel NP, Koirala S, Ramesh P, Gurung D, Shrestha P, Tol WA, Brandon A, Jordans MJD (2014). The role of mental health and psychosocial support nongovernmental organisations: reflections from post conflict Nepal . Intervention 12 , 113–128. [ Google Scholar ]

- van Ommeren M, Sharma B, Thapa S, Makaju R, Prasain D, Bhattarai R, de Jong J (1999). Preparing instruments for transcultural research: use of the translation monitoring form with Nepali-speaking Bhutanese refugees . Transcultural Psychiatry 36 , 285–301. [ Google Scholar ]

- Watters E (2010). Crazy Like Us: The Globalization of the Western Mind . Robinson: London. [ Google Scholar ]

- Whitley R (2015). Global Mental Health: concepts, conflicts and controversies . Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 24 , 285–291. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- World Health Organization (2011). Mental Health Atlas 2011: Nepal . Geneva. [ Google Scholar ]

- World Health Organization (2013 a ). Building Back Better: Sustainable Mental Health Care after Emergencies . Geneva. [ Google Scholar ]

- World Health Organization (2013 b ). Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020 . Geneva. [ Google Scholar ]

Loss of Meaning in Translation: The Case Study of a Nepali Novel ‘Basain’

- Dr. Ramesh Prasad Adhikary Assistant Professor (English) TU, M. M. Campus, Nepalgunj, Nepal

The research paper titled‘Loss of Meaning in Translation: The Case Study of a Nepali Novel Basain’ was an attempt of the researcher to find out the cases of cultural meaning loss in the translation of a novel ‘Basain’. It further aimed to explore the causes of loss of meaning in translation. In addition, it aimed to analyze the ways that can be used to compensate the meaning gap in translation as well. Only the secondary sources of data were used in the study employing descriptive and analytical design along with qualitative data. Twenty two cases of meaning loss in the translation of the novel Basain were found. The study also explored causes of the loss of meaning to occur in translation. Some of the major causes were pointed out i.e. cultural gap, deletion, negligence of the translator, lack of functional equivalence, lack of co-cultural and socio-cultural knowledge (of the SL) of the translator, over generalization of the meaning, carelessness of the translator, incomplete linguistic knowledge (of the SL) of the translator, transliteration and so on.

Author Biography

Dr. ramesh prasad adhikary, assistant professor (english) tu, m. m. campus, nepalgunj, nepal.

Dr. Ramesh Prasad Adhikary is an assistant professor of Tribhuwan University, Kathmandu, Nepal. He has been teaching English literature at M.M. Campus since 2007. He has completed his PhD in Existential philosophy and has been researching on English language, literature and literary theories. He has created more than 40 international articles and 18 books on various topics of English literature.

Bhandari, G. (2007). Study on techniques and gaps of translation of cultural terms: A case of the novel ‘Basain’ (unpublished M. Ed. thesis). Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Bhattarai, G. R. (2002). Bridging gaps in translation: An experience of rendering. Journal of Nepali Literature, Art and Culture, 4(2), 68-70.

Bhattarai, G. R. (2007). An introduction to translation studies. Kathmandu, Nepal: Ratna Pustak Bhandar.

Crystal, D. (1987). The Cambridge encyclopedia of language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

House, J. (1994). Translation: Evaluation. In R. E. Asher & J. M. Y. Simpson (Eds.), The Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics (pp. 4700-4708). Oxford and New York: Pergamon Press.

House, J. (2002). Universality versus culture specificity in translation. In A. Riccardi (Ed.), Translation Studies: Perspectives on an Emerging Discipline (pp. 92-110). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ivir, V. (1987). Procedure and strategies for the translation of culture. Indian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 13(2), 35-46.

Newmark, P. (1981). Approaches to translation (language teaching methodology series). Oxford: Pergamum Press.

Newmark, P. (1988). A textbook of translation (Vol. 66). New York: Prentice Hall.

Richards, J. C., Platt, J., & Weber, H. (1985). Longman dictionary of applied linguistics. Hongkong: Longman Group Ltd.

Sharma, B. K. (2004). An evaluation of translation: A case study of a translated textbook of social studies for grade ten (unpublished M. Ed. thesis). Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Wilss, W. (1982). The science of translation: Problems and methods. Tubinger: Gunter Narr Verlag.

How to Cite

- Endnote/Zotero/Mendeley (RIS)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

License Terms

All articles published by MARS Publishers are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. This means:

- everyone has free and unlimited access to the full-text of all articles published in MARS Publishers' journals;

- everyone is free to re-use the published material if proper accreditation/citation of the original publication is given.

Most read articles by the same author(s)

- Dr. Ramesh Prasad Adhikary, English Subject Teachers’ Perceptions and Strategies in Managing Large Classes: A Case Study of Nepal , Linguistic Forum - A Journal of Linguistics: Vol. 2 No. 1 (2020): Linguistic Forum - A Journal of Linguistics

Journal Cover

Journal highlights.

E-ISSN: 2707-5273

DOI Prefix: 10.53057/linfo

Publication Frequency: Quarterly

Started: 2018

Language: English

Make a Submission

Current issue, information.

- For Readers

- For Authors

- For Librarians

Social Contact

Find out more

- Aims and Scope

- Call for Papers

- Google Scholar Citations

ISSN Online 2707-5273

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

Advertisement

English teachers’ awareness of collaborative learning: a case study in Nepal

- Original Paper

- Published: 01 July 2022

- Volume 2 , article number 107 , ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Kesh Rana ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7997-8452 1 &

- Karna Rana ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3665-878X 1

122 Accesses

Explore all metrics

This article reports the examination of secondary English teachers’ awareness of collaborative learning strategies. This study based on qualitative research employed a semi-structured interview with secondary English teachers and students to investigate English teachers’ practices of collaborative learning strategies in their classrooms. Classroom observation revealed how the teachers managed a collaborative environment and involved students in learning activities. This study involved English teachers and students from eight secondary schools representing different parts of the country. Teachers’ classes were observed to crystalise the data elicited from the interviews. The sociocultural theory (SCT) has provided a lens to analyse the qualitative data. The findings indicate that teachers’ traditional pedagogy dominated the limited collaborative language learning activities in the classrooms. Group work, peer support, and dialogue, albeit limited, have been identified as effective collaborative learning strategies in the English language classroom. Teachers’ limited knowledge of collaborative learning, however, seemed to be a barrier to implementing collaborative learning activities extensively in the English classrooms. Adequate training would develop English teachers’ ability to involve students in various collaborative activities and allow them to learn English from interactivities.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Exploring the role of social media in collaborative learning the new domain of learning

Jamal Abdul Nasir Ansari & Nawab Ali Khan

Investigating blended learning interactions in Philippine schools through the community of inquiry framework

Juliet Aleta R. Villanueva, Petrea Redmond, … Douglas Eacersall

Creating a Motivating Classroom Environment

Availability of data and material.

Available upon request.

Code availability

Aghaei P, Bavali M, Behjat F (2020) An in-depth qualitative study of teachers’ role identities: a case of Iranian EFL teachers. Int J Instruct 13(2):601–620. https://doi.org/10.29333/iji.2020.13241a

Article Google Scholar

Aimin L (2013) The study of second language acquisition under socio-cultural theory. Am J Educ Res 1(5):162–167. https://doi.org/10.12691/education-1-5-3

Alamri WA (2018) Communicative language teaching: possible alternative approaches to CLT and teaching contexts. Engl Lang Teach 11(10):132–138. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v11n10p132

Bilen D, Tavil ZM (2015) The Effects of cooperative learning strategies on vocabulary skills of 4th grade students. J Educ Train Stud 3(6):151–165. https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v3i6.1062

Bransford J, Derry S, Berliner D, Hammerness K, Beckett KL (2005) Theories of learning and their roles in teaching. In: Darling-Hammond L, Bransford J (eds) Preparing teachers for a changing world: WHAT teachers should learn and be able to do. Wiley, New York, pp 40–87

Google Scholar

Braun V, Clarke V, Weate P (2016) Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In: Smith B, Sparkes AC (eds) Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise. Taylor & Francis, New York, pp 191–205

Bruffee KA (1995) Sharing our toys: cooperative learning versus collaborative learning. Change Mag High Learn 27(1):12–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.1995.9937722

Bryman A (2016) Social research methods. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Buchs C, Filippou D, Pulfrey C, Volpé Y (2017) Challenges for cooperative learning implementation: reports from elementary school teachers. J Educ Teach 43(3):296–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2017.1321673

Bulakh V, Shandruk S, Akhmetshin E, Nogovitsina O, Panachev V, Legotkin L, Ponomarev N (2019) Professional training of teachers in the united states as an example for improving the professionalism and competence of pedagogues in Ukraine. Space Cul India 7(2):101–111. https://doi.org/10.20896/saci.v7i2.454

Cirocki A, Farrell TSC (2019) Professional development of secondary school EFL teachers: Voices from Indonesia. System 85:102111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2019.102111

Cohen L, Manion L, Morrison K (2007) Research methods in education, vol 6. Routledge, London

Book Google Scholar

Cooke M, Simpson J (2012) Discourses about linguistic diversity. In: Martin-Jones M, Blackledge A, Creese A (eds) The Routledge handbook of multilingualism. Routledge, London, pp 116–130

Creese A, Blackledge A (2010) Translanguaging in the bilingual classroom: a pedagogy for learning and teaching? Mod Lang J 94(1):103–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2009.00986.x

Curriculum Development Centre (2021) Secondary education curriculum. Curriculum Development Centre. http://202.45.146.138/elibrary/pages/view.php?ref=9872&k=#

Damon W, Phelps E (1989) Critical distinctions among three approaches to peer education. Int J Educ Res 13(1):9–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-0355(89)90013-X

Danli L (2017) Autonomy in scaffolding as learning in teacher-student negotiation of meaning in a university EFL classroom. Chin J Appl Ling 40(4):410. https://doi.org/10.1515/cjal-2017-0024

Davidson N, Major CH (2014) Boundary crossings: cooperative learning, collaborative learning, and problem-based learning. J Excel Coll Teach 25(3–4):7–55