Enterprise Risk Management Case Studies: Heroes and Zeros

By Andy Marker | April 7, 2021

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

Link copied

We’ve compiled more than 20 case studies of enterprise risk management programs that illustrate how companies can prevent significant losses yet take risks with more confidence.

Included on this page, you’ll find case studies and examples by industry , case studies of major risk scenarios (and company responses), and examples of ERM successes and failures .

Enterprise Risk Management Examples and Case Studies

With enterprise risk management (ERM) , companies assess potential risks that could derail strategic objectives and implement measures to minimize or avoid those risks. You can analyze examples (or case studies) of enterprise risk management to better understand the concept and how to properly execute it.

The collection of examples and case studies on this page illustrates common risk management scenarios by industry, principle, and degree of success. For a basic overview of enterprise risk management, including major types of risks, how to develop policies, and how to identify key risk indicators (KRIs), read “ Enterprise Risk Management 101: Programs, Frameworks, and Advice from Experts .”

Enterprise Risk Management Framework Examples

An enterprise risk management framework is a system by which you assess and mitigate potential risks. The framework varies by industry, but most include roles and responsibilities, a methodology for risk identification, a risk appetite statement, risk prioritization, mitigation strategies, and monitoring and reporting.

To learn more about enterprise risk management and find examples of different frameworks, read our “ Ultimate Guide to Enterprise Risk Management .”

Enterprise Risk Management Examples and Case Studies by Industry

Though every firm faces unique risks, those in the same industry often share similar risks. By understanding industry-wide common risks, you can create and implement response plans that offer your firm a competitive advantage.

Enterprise Risk Management Example in Banking

Toronto-headquartered TD Bank organizes its risk management around two pillars: a risk management framework and risk appetite statement. The enterprise risk framework defines the risks the bank faces and lays out risk management practices to identify, assess, and control risk. The risk appetite statement outlines the bank’s willingness to take on risk to achieve its growth objectives. Both pillars are overseen by the risk committee of the company’s board of directors.

Risk management frameworks were an important part of the International Organization for Standardization’s 31000 standard when it was first written in 2009 and have been updated since then. The standards provide universal guidelines for risk management programs.

Risk management frameworks also resulted from the efforts of the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO). The group was formed to fight corporate fraud and included risk management as a dimension.

Once TD completes the ERM framework, the bank moves onto the risk appetite statement.

The bank, which built a large U.S. presence through major acquisitions, determined that it will only take on risks that meet the following three criteria:

- The risk fits the company’s strategy, and TD can understand and manage those risks.

- The risk does not render the bank vulnerable to significant loss from a single risk.

- The risk does not expose the company to potential harm to its brand and reputation.

Some of the major risks the bank faces include strategic risk, credit risk, market risk, liquidity risk, operational risk, insurance risk, capital adequacy risk, regulator risk, and reputation risk. Managers detail these categories in a risk inventory.

The risk framework and appetite statement, which are tracked on a dashboard against metrics such as capital adequacy and credit risk, are reviewed annually.

TD uses a three lines of defense (3LOD) strategy, an approach widely favored by ERM experts, to guard against risk. The three lines are as follows:

- A business unit and corporate policies that create controls, as well as manage and monitor risk

- Standards and governance that provide oversight and review of risks and compliance with the risk appetite and framework

- Internal audits that provide independent checks and verification that risk-management procedures are effective

Enterprise Risk Management Example in Pharmaceuticals

Drug companies’ risks include threats around product quality and safety, regulatory action, and consumer trust. To avoid these risks, ERM experts emphasize the importance of making sure that strategic goals do not conflict.

For Britain’s GlaxoSmithKline, such a conflict led to a breakdown in risk management, among other issues. In the early 2000s, the company was striving to increase sales and profitability while also ensuring safe and effective medicines. One risk the company faced was a failure to meet current good manufacturing practices (CGMP) at its plant in Cidra, Puerto Rico.

CGMP includes implementing oversight and controls of manufacturing, as well as managing the risk and confirming the safety of raw materials and finished drug products. Noncompliance with CGMP can result in escalating consequences, ranging from warnings to recalls to criminal prosecution.

GSK’s unit pleaded guilty and paid $750 million in 2010 to resolve U.S. charges related to drugs made at the Cidra plant, which the company later closed. A fired GSK quality manager alerted regulators and filed a whistleblower lawsuit in 2004. In announcing the consent decree, the U.S. Department of Justice said the plant had a history of bacterial contamination and multiple drugs created there in the early 2000s violated safety standards.

According to the whistleblower, GSK’s ERM process failed in several respects to act on signs of non-compliance with CGMP. The company received warning letters from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2001 about the plant’s practices, but did not resolve the issues.

Additionally, the company didn’t act on the quality manager’s compliance report, which advised GSK to close the plant for two weeks to fix the problems and notify the FDA. According to court filings, plant staff merely skimmed rejected products and sold them on the black market. They also scraped by hand the inside of an antibiotic tank to get more product and, in so doing, introduced bacteria into the product.

Enterprise Risk Management Example in Consumer Packaged Goods

Mars Inc., an international candy and food company, developed an ERM process. The company piloted and deployed the initiative through workshops with geographic, product, and functional teams from 2003 to 2012.

Driven by a desire to frame risk as an opportunity and to work within the company’s decentralized structure, Mars created a process that asked participants to identify potential risks and vote on which had the highest probability. The teams listed risk mitigation steps, then ranked and color-coded them according to probability of success.

Larry Warner, a Mars risk officer at the time, illustrated this process in a case study . An initiative to increase direct-to-consumer shipments by 12 percent was colored green, indicating a 75 percent or greater probability of achievement. The initiative to bring a new plant online by the end of Q3 was coded red, meaning less than a 50 percent probability of success.

The company’s results were hurt by a surprise at an operating unit that resulted from a so-coded red risk identified in a unit workshop. Executives had agreed that some red risk profile was to be expected, but they decided that when a unit encountered a red issue, it must be communicated upward when first identified. This became a rule.

This process led to the creation of an ERM dashboard that listed initiatives in priority order, with the profile of each risk faced in the quarter, the risk profile trend, and a comment column for a year-end view.

According to Warner, the key factors of success for ERM at Mars are as follows:

- The initiative focused on achieving operational and strategic objectives rather than compliance, which refers to adhering to established rules and regulations.

- The program evolved, often based on requests from business units, and incorporated continuous improvement.

- The ERM team did not overpromise. It set realistic objectives.

- The ERM team periodically surveyed business units, management teams, and board advisers.

Enterprise Risk Management Example in Retail

Walmart is the world’s biggest retailer. As such, the company understands that its risk makeup is complex, given the geographic spread of its operations and its large number of stores, vast supply chain, and high profile as an employer and buyer of goods.

In the 1990s, the company sought a simplified strategy for assessing risk and created an enterprise risk management plan with five steps founded on these four questions:

- What are the risks?

- What are we going to do about them?

- How will we know if we are raising or decreasing risk?

- How will we show shareholder value?

The process follows these five steps:

- Risk Identification: Senior Walmart leaders meet in workshops to identify risks, which are then plotted on a graph of probability vs. impact. Doing so helps to prioritize the biggest risks. The executives then look at seven risk categories (both internal and external): legal/regulatory, political, business environment, strategic, operational, financial, and integrity. Many ERM pros use risk registers to evaluate and determine the priority of risks. You can download templates that help correlate risk probability and potential impact in “ Free Risk Register Templates .”

- Risk Mitigation: Teams that include operational staff in the relevant area meet. They use existing inventory procedures to address the risks and determine if the procedures are effective.

- Action Planning: A project team identifies and implements next steps over the several months to follow.

- Performance Metrics: The group develops metrics to measure the impact of the changes. They also look at trends of actual performance compared to goal over time.

- Return on Investment and Shareholder Value: In this step, the group assesses the changes’ impact on sales and expenses to determine if the moves improved shareholder value and ROI.

To develop your own risk management planning, you can download a customizable template in “ Risk Management Plan Templates .”

Enterprise Risk Management Example in Agriculture

United Grain Growers (UGG), a Canadian grain distributor that now is part of Glencore Ltd., was hailed as an ERM innovator and became the subject of business school case studies for its enterprise risk management program. This initiative addressed the risks associated with weather for its business. Crop volume drove UGG’s revenue and profits.

In the late 1990s, UGG identified its major unaddressed risks. Using almost a century of data, risk analysts found that extreme weather events occurred 10 times as frequently as previously believed. The company worked with its insurance broker and the Swiss Re Group on a solution that added grain-volume risk (resulting from weather fluctuations) to its other insured risks, such as property and liability, in an integrated program.

The result was insurance that protected grain-handling earnings, which comprised half of UGG’s gross profits. The greater financial stability significantly enhanced the firm’s ability to achieve its strategic objectives.

Since then, the number and types of instruments to manage weather-related risks has multiplied rapidly. For example, over-the-counter derivatives, such as futures and options, began trading in 1997. The Chicago Mercantile Exchange now offers weather futures contracts on 12 U.S. and international cities.

Weather derivatives are linked to climate factors such as rainfall or temperature, and they hedge different kinds of risks than do insurance. These risks are much more common (e.g., a cooler-than-normal summer) than the earthquakes and floods that insurance typically covers. And the holders of derivatives do not have to incur any damage to collect on them.

These weather-linked instruments have found a wider audience than anticipated, including retailers that worry about freak storms decimating Christmas sales, amusement park operators fearing rainy summers will keep crowds away, and energy companies needing to hedge demand for heating and cooling.

This area of ERM continues to evolve because weather and crop insurance are not enough to address all the risks that agriculture faces. Arbol, Inc. estimates that more than $1 trillion of agricultural risk is uninsured. As such, it is launching a blockchain-based platform that offers contracts (customized by location and risk parameters) with payouts based on weather data. These contracts can cover risks associated with niche crops and small growing areas.

Enterprise Risk Management Example in Insurance

Switzerland’s Zurich Insurance Group understands that risk is inherent for insurers and seeks to practice disciplined risk-taking, within a predetermined risk tolerance.

The global insurer’s enterprise risk management framework aims to protect capital, liquidity, earnings, and reputation. Governance serves as the basis for risk management, and the framework lays out responsibilities for taking, managing, monitoring, and reporting risks.

The company uses a proprietary process called Total Risk Profiling (TRP) to monitor internal and external risks to its strategy and financial plan. TRP assesses risk on the basis of severity and probability, and helps define and implement mitigating moves.

Zurich’s risk appetite sets parameters for its tolerance within the goal of maintaining enough capital to achieve an AA rating from rating agencies. For this, the company uses its own Zurich economic capital model, referred to as Z-ECM. The model quantifies risk tolerance with a metric that assesses risk profile vs. risk tolerance.

To maintain the AA rating, the company aims to hold capital between 100 and 120 percent of capital at risk. Above 140 percent is considered overcapitalized (therefore at risk of throttling growth), and under 90 percent is below risk tolerance (meaning the risk is too high). On either side of 100 to 120 percent (90 to 100 percent and 120 to 140 percent), the insurer considers taking mitigating action.

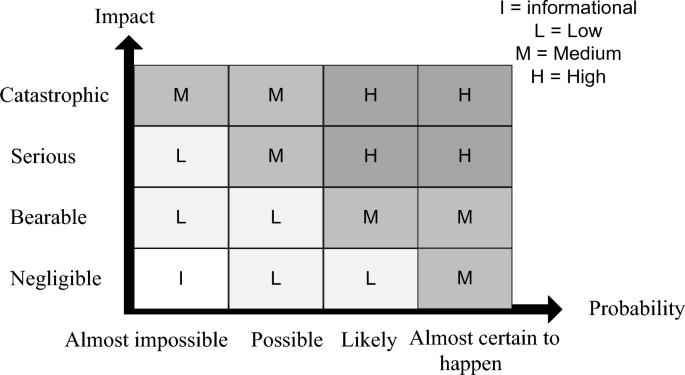

Zurich’s assessment of risk and the nature of those risks play a major role in determining how much capital regulators require the business to hold. A popular tool to assess risk is the risk matrix, and you can find a variety of templates in “ Free, Customizable Risk Matrix Templates .”

In 2020, Zurich found that its biggest exposures were market risk, such as falling asset valuations and interest-rate risk; insurance risk, such as big payouts for covered customer losses, which it hedges through diversification and reinsurance; credit risk in assets it holds and receivables; and operational risks, such as internal process failures and external fraud.

Enterprise Risk Management Example in Technology

Financial software maker Intuit has strengthened its enterprise risk management through evolution, according to a case study by former Chief Risk Officer Janet Nasburg.

The program is founded on the following five core principles:

- Use a common risk framework across the enterprise.

- Assess risks on an ongoing basis.

- Focus on the most important risks.

- Clearly define accountability for risk management.

- Commit to continuous improvement of performance measurement and monitoring.

ERM programs grow according to a maturity model, and as capability rises, the shareholder value from risk management becomes more visible and important.

The maturity phases include the following:

- Ad hoc risk management addresses a specific problem when it arises.

- Targeted or initial risk management approaches risks with multiple understandings of what constitutes risk and management occurs in silos.

- Integrated or repeatable risk management puts in place an organization-wide framework for risk assessment and response.

- Intelligent or managed risk management coordinates risk management across the business, using common tools.

- Risk leadership incorporates risk management into strategic decision-making.

Intuit emphasizes using key risk indicators (KRIs) to understand risks, along with key performance indicators (KPIs) to gauge the effectiveness of risk management.

Early in its ERM journey, Intuit measured performance on risk management process participation and risk assessment impact. For participation, the targeted rate was 80 percent of executive management and business-line leaders. This helped benchmark risk awareness and current risk management, at a time when ERM at the company was not mature.

Conduct an annual risk assessment at corporate and business-line levels to plot risks, so the most likely and most impactful risks are graphed in the upper-right quadrant. Doing so focuses attention on these risks and helps business leaders understand the risk’s impact on performance toward strategic objectives.

In the company’s second phase of ERM, Intuit turned its attention to building risk management capacity and sought to ensure that risk management activities addressed the most important risks. The company evaluated performance using color-coded status symbols (red, yellow, green) to indicate risk trend and progress on risk mitigation measures.

In its third phase, Intuit moved to actively monitoring the most important risks and ensuring that leaders modified their strategies to manage risks and take advantage of opportunities. An executive dashboard uses KRIs, KPIs, an overall risk rating, and red-yellow-green coding. The board of directors regularly reviews this dashboard.

Over this evolution, the company has moved from narrow, tactical risk management to holistic, strategic, and long-term ERM.

Enterprise Risk Management Case Studies by Principle

ERM veterans agree that in addition to KPIs and KRIs, other principles are equally important to follow. Below, you’ll find examples of enterprise risk management programs by principles.

ERM Principle #1: Make Sure Your Program Aligns with Your Values

Raytheon Case Study U.S. defense contractor Raytheon states that its highest priority is delivering on its commitment to provide ethical business practices and abide by anti-corruption laws.

Raytheon backs up this statement through its ERM program. Among other measures, the company performs an annual risk assessment for each function, including the anti-corruption group under the Chief Ethics and Compliance Officer. In addition, Raytheon asks 70 of its sites to perform an anti-corruption self-assessment each year to identify gaps and risks. From there, a compliance team tracks improvement actions.

Every quarter, the company surveys 600 staff members who may face higher anti-corruption risks, such as the potential for bribes. The survey asks them to report any potential issues in the past quarter.

Also on a quarterly basis, the finance and internal controls teams review higher-risk profile payments, such as donations and gratuities to confirm accuracy and compliance. Oversight and compliance teams add other checks, and they update a risk-based audit plan continuously.

ERM Principle #2: Embrace Diversity to Reduce Risk

State Street Global Advisors Case Study In 2016, the asset management firm State Street Global Advisors introduced measures to increase gender diversity in its leadership as a way of reducing portfolio risk, among other goals.

The company relied on research that showed that companies with more women senior managers had a better return on equity, reduced volatility, and fewer governance problems such as corruption and fraud.

Among the initiatives was a campaign to influence companies where State Street had invested, in order to increase female membership on their boards. State Street also developed an investment product that tracks the performance of companies with the highest level of senior female leadership relative to peers in their sector.

In 2020, the company announced some of the results of its effort. Among the 1,384 companies targeted by the firm, 681 added at least one female director.

ERM Principle #3: Do Not Overlook Resource Risks

Infosys Case Study India-based technology consulting company Infosys, which employees more than 240,000 people, has long recognized the risk of water shortages to its operations.

India’s rapidly growing population and development has increased the risk of water scarcity. A 2020 report by the World Wide Fund for Nature said 30 cities in India faced the risk of severe water scarcity over the next three decades.

Infosys has dozens of facilities in India and considers water to be a significant short-term risk. At its campuses, the company uses the water for cooking, drinking, cleaning, restrooms, landscaping, and cooling. Water shortages could halt Infosys operations and prevent it from completing customer projects and reaching its performance objectives.

In an enterprise risk assessment example, Infosys’ ERM team conducts corporate water-risk assessments while sustainability teams produce detailed water-risk assessments for individual locations, according to a report by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development .

The company uses the COSO ERM framework to respond to the risks and decide whether to accept, avoid, reduce, or share these risks. The company uses root-cause analysis (which focuses on identifying underlying causes rather than symptoms) and the site assessments to plan steps to reduce risks.

Infosys has implemented various water conservation measures, such as water-efficient fixtures and water recycling, rainwater collection and use, recharging aquifers, underground reservoirs to hold five days of water supply at locations, and smart-meter usage monitoring. Infosys’ ERM team tracks metrics for per-capita water consumption, along with rainfall data, availability and cost of water by tanker trucks, and water usage from external suppliers.

In the 2020 fiscal year, the company reported a nearly 64 percent drop in per-capita water consumption by its workforce from the 2008 fiscal year.

The business advantages of this risk management include an ability to open locations where water shortages may preclude competitors, and being able to maintain operations during water scarcity, protecting profitability.

ERM Principle #4: Fight Silos for Stronger Enterprise Risk Management

U.S. Government Case Study The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, revealed that the U.S. government’s then-current approach to managing intelligence was not adequate to address the threats — and, by extension, so was the government’s risk management procedure. Since the Cold War, sensitive information had been managed on a “need to know” basis that resulted in data silos.

In the case of 9/11, this meant that different parts of the government knew some relevant intelligence that could have helped prevent the attacks. But no one had the opportunity to put the information together and see the whole picture. A congressional commission determined there were 10 lost operational opportunities to derail the plot. Silos existed between law enforcement and intelligence, as well as between and within agencies.

After the attacks, the government moved toward greater information sharing and collaboration. Based on a task force’s recommendations, data moved from a centralized network to a distributed model, and social networking tools now allow colleagues throughout the government to connect. Staff began working across agency lines more often.

Enterprise Risk Management Examples by Scenario

While some scenarios are too unlikely to receive high-priority status, low-probability risks are still worth running through the ERM process. Robust risk management creates a culture and response capacity that better positions a company to deal with a crisis.

In the following enterprise risk examples, you will find scenarios and details of how organizations manage the risks they face.

Scenario: ERM and the Global Pandemic While most businesses do not have the resources to do in-depth ERM planning for the rare occurrence of a global pandemic, companies with a risk-aware culture will be at an advantage if a pandemic does hit.

These businesses already have processes in place to escalate trouble signs for immediate attention and an ERM team or leader monitoring the threat environment. A strong ERM function gives clear and effective guidance that helps the company respond.

A report by Vodafone found that companies identified as “future ready” fared better in the COVID-19 pandemic. The attributes of future-ready businesses have a lot in common with those of companies that excel at ERM. These include viewing change as an opportunity; having detailed business strategies that are documented, funded, and measured; working to understand the forces that shape their environments; having roadmaps in place for technological transformation; and being able to react more quickly than competitors.

Only about 20 percent of companies in the Vodafone study met the definition of “future ready.” But 54 percent of these firms had a fully developed and tested business continuity plan, compared to 30 percent of all businesses. And 82 percent felt their continuity plans worked well during the COVID-19 crisis. Nearly 50 percent of all businesses reported decreased profits, while 30 percent of future-ready organizations saw profits rise.

Scenario: ERM and the Economic Crisis The 2008 economic crisis in the United States resulted from the domino effect of rising interest rates, a collapse in housing prices, and a dramatic increase in foreclosures among mortgage borrowers with poor creditworthiness. This led to bank failures, a credit crunch, and layoffs, and the U.S. government had to rescue banks and other financial institutions to stabilize the financial system.

Some commentators said these events revealed the shortcomings of ERM because it did not prevent the banks’ mistakes or collapse. But Sim Segal, an ERM consultant and director of Columbia University’s ERM master’s degree program, analyzed how banks performed on 10 key ERM criteria.

Segal says a risk-management program that incorporates all 10 criteria has these characteristics:

- Risk management has an enterprise-wide scope.

- The program includes all risk categories: financial, operational, and strategic.

- The focus is on the most important risks, not all possible risks.

- Risk management is integrated across risk types.

- Aggregated metrics show risk exposure and appetite across the enterprise.

- Risk management incorporates decision-making, not just reporting.

- The effort balances risk and return management.

- There is a process for disclosure of risk.

- The program measures risk in terms of potential impact on company value.

- The focus of risk management is on the primary stakeholder, such as shareholders, rather than regulators or rating agencies.

In his book Corporate Value of Enterprise Risk Management , Segal concluded that most banks did not actually use ERM practices, which contributed to the financial crisis. He scored banks as failing on nine of the 10 criteria, only giving them a passing grade for focusing on the most important risks.

Scenario: ERM and Technology Risk The story of retailer Target’s failed expansion to Canada, where it shut down 133 loss-making stores in 2015, has been well documented. But one dimension that analysts have sometimes overlooked was Target’s handling of technology risk.

A case study by Canadian Business magazine traced some of the biggest issues to software and data-quality problems that dramatically undermined the Canadian launch.

As with other forms of ERM, technology risk management requires companies to ask what could go wrong, what the consequences would be, how they might prevent the risks, and how they should deal with the consequences.

But with its technology plan for Canada, Target did not heed risk warning signs.

In the United States, Target had custom systems for ordering products from vendors, processing items at warehouses, and distributing merchandise to stores quickly. But that software would need customization to work with the Canadian dollar, metric system, and French-language characters.

Target decided to go with new ERP software on an aggressive two-year timeline. As Target began ordering products for the Canadian stores in 2012, problems arose. Some items did not fit into shipping containers or on store shelves, and information needed for customs agents to clear imported items was not correct in Target's system.

Target found that its supply chain software data was full of errors. Product dimensions were in inches, not centimeters; height and width measurements were mixed up. An internal investigation showed that only about 30 percent of the data was accurate.

In an attempt to fix these errors, Target merchandisers spent a week double-checking with vendors up to 80 data points for each of the retailer’s 75,000 products. They discovered that the dummy data entered into the software during setup had not been altered. To make any corrections, employees had to send the new information to an office in India where staff would enter it into the system.

As the launch approached, the technology errors left the company vulnerable to stockouts, few people understood how the system worked, and the point-of-sale checkout system did not function correctly. Soon after stores opened in 2013, consumers began complaining about empty shelves. Meanwhile, Target Canada distribution centers overflowed due to excess ordering based on poor data fed into forecasting software.

The rushed launch compounded problems because it did not allow the company enough time to find solutions or alternative technology. While the retailer fixed some issues by the end of 2014, it was too late. Target Canada filed for bankruptcy protection in early 2015.

Scenario: ERM and Cybersecurity System hacks and data theft are major worries for companies. But as a relatively new field, cyber-risk management faces unique hurdles.

For example, risk managers and information security officers have difficulty quantifying the likelihood and business impact of a cybersecurity attack. The rise of cloud-based software exposes companies to third-party risks that make these projections even more difficult to calculate.

As the field evolves, risk managers say it’s important for IT security officers to look beyond technical issues, such as the need to patch a vulnerability, and instead look more broadly at business impacts to make a cost benefit analysis of risk mitigation. Frameworks such as the Risk Management Framework for Information Systems and Organizations by the National Institute of Standards and Technology can help.

Health insurer Aetna considers cybersecurity threats as a part of operational risk within its ERM framework and calculates a daily risk score, adjusted with changes in the cyberthreat landscape.

Aetna studies threats from external actors by working through information sharing and analysis centers for the financial services and health industries. Aetna staff reverse-engineers malware to determine controls. The company says this type of activity helps ensure the resiliency of its business processes and greatly improves its ability to help protect member information.

For internal threats, Aetna uses models that compare current user behavior to past behavior and identify anomalies. (The company says it was the first organization to do this at scale across the enterprise.) Aetna gives staff permissions to networks and data based on what they need to perform their job. This segmentation restricts access to raw data and strengthens governance.

Another risk initiative scans outgoing employee emails for code patterns, such as credit card or Social Security numbers. The system flags the email, and a security officer assesses it before the email is released.

Examples of Poor Enterprise Risk Management

Case studies of failed enterprise risk management often highlight mistakes that managers could and should have spotted — and corrected — before a full-blown crisis erupted. The focus of these examples is often on determining why that did not happen.

ERM Case Study: General Motors

In 2014, General Motors recalled the first of what would become 29 million cars due to faulty ignition switches and paid compensation for 124 related deaths. GM knew of the problem for at least 10 years but did not act, the automaker later acknowledged. The company entered a deferred prosecution agreement and paid a $900 million penalty.

Pointing to the length of time the company failed to disclose the safety problem, ERM specialists say it shows the problem did not reside with a single department. “Rather, it reflects a failure to properly manage risk,” wrote Steve Minsky, a writer on ERM and CEO of an ERM software company, in Risk Management magazine.

“ERM is designed to keep all parties across the organization, from the front lines to the board to regulators, apprised of these kinds of problems as they become evident. Unfortunately, GM failed to implement such a program, ultimately leading to a tragic and costly scandal,” Minsky said.

Also in the auto sector, an enterprise risk management case study of Toyota looked at its problems with unintended acceleration of vehicles from 2002 to 2009. Several studies, including a case study by Carnegie Mellon University Professor Phil Koopman , blamed poor software design and company culture. A whistleblower later revealed a coverup by Toyota. The company paid more than $2.5 billion in fines and settlements.

ERM Case Study: Lululemon

In 2013, following customer complaints that its black yoga pants were too sheer, the athletic apparel maker recalled 17 percent of its inventory at a cost of $67 million. The company had previously identified risks related to fabric supply and quality. The CEO said the issue was inadequate testing.

Analysts raised concerns about the company’s controls, including oversight of factories and product quality. A case study by Stanford University professors noted that Lululemon’s episode illustrated a common disconnect between identifying risks and being prepared to manage them when they materialize. Lululemon’s reporting and analysis of risks was also inadequate, especially as related to social media. In addition, the case study highlighted the need for a system to escalate risk-related issues to the board.

ERM Case Study: Kodak

Once an iconic brand, the photo film company failed for decades to act on the threat that digital photography posed to its business and eventually filed for bankruptcy in 2012. The company’s own research in 1981 found that digital photos could ultimately replace Kodak’s film technology and estimated it had 10 years to prepare.

Unfortunately, Kodak did not prepare and stayed locked into the film paradigm. The board reinforced this course when in 1989 it chose as CEO a candidate who came from the film business over an executive interested in digital technology.

Had the company acknowledged the risks and employed ERM strategies, it might have pursued a variety of strategies to remain successful. The company’s rival, Fuji Film, took the money it made from film and invested in new initiatives, some of which paid off. Kodak, on the other hand, kept investing in the old core business.

Case Studies of Successful Enterprise Risk Management

Successful enterprise risk management usually requires strong performance in multiple dimensions, and is therefore more likely to occur in organizations where ERM has matured. The following examples of enterprise risk management can be considered success stories.

ERM Case Study: Statoil

A major global oil producer, Statoil of Norway stands out for the way it practices ERM by looking at both downside risk and upside potential. Taking risks is vital in a business that depends on finding new oil reserves.

According to a case study, the company developed its own framework founded on two basic goals: creating value and avoiding accidents.

The company aims to understand risks thoroughly, and unlike many ERM programs, Statoil maps risks on both the downside and upside. It graphs risk on probability vs. impact on pre-tax earnings, and it examines each risk from both positive and negative perspectives.

For example, the case study cites a risk that the company assessed as having a 5 percent probability of a somewhat better-than-expected outcome but a 10 percent probability of a significant loss relative to forecast. In this case, the downside risk was greater than the upside potential.

ERM Case Study: Lego

The Danish toy maker’s ERM evolved over the following four phases, according to a case study by one of the chief architects of its program:

- Traditional management of financial, operational, and other risks. Strategic risk management joined the ERM program in 2006.

- The company added Monte Carlo simulations in 2008 to model financial performance volatility so that budgeting and financial processes could incorporate risk management. The technique is used in budget simulations, to assess risk in its credit portfolio, and to consolidate risk exposure.

- Active risk and opportunity planning is part of making a business case for new projects before final decisions.

- The company prepares for uncertainty so that long-term strategies remain relevant and resilient under different scenarios.

As part of its scenario modeling, Lego developed its PAPA (park, adapt, prepare, act) model.

- Park: The company parks risks that occur slowly and have a low probability of happening, meaning it does not forget nor actively deal with them.

- Adapt: This response is for risks that evolve slowly and are certain or highly probable to occur. For example, a risk in this category is the changing nature of play and the evolution of buying power in different parts of the world. In this phase, the company adjusts, monitors the trend, and follows developments.

- Prepare: This category includes risks that have a low probability of occurring — but when they do, they emerge rapidly. These risks go into the ERM risk database with contingency plans, early warning indicators, and mitigation measures in place.

- Act: These are high-probability, fast-moving risks that must be acted upon to maintain strategy. For example, developments around connectivity, mobile devices, and online activity are in this category because of the rapid pace of change and the influence on the way children play.

Lego views risk management as a way to better equip itself to take risks than its competitors. In the case study, the writer likens this approach to the need for the fastest race cars to have the best brakes and steering to achieve top speeds.

ERM Case Study: University of California

The University of California, one of the biggest U.S. public university systems, introduced a new view of risk to its workforce when it implemented enterprise risk management in 2005. Previously, the function was merely seen as a compliance requirement.

ERM became a way to support the university’s mission of education and research, drawing on collaboration of the system’s employees across departments. “Our philosophy is, ‘Everyone is a risk manager,’” Erike Young, deputy director of ERM told Treasury and Risk magazine. “Anyone who’s in a management position technically manages some type of risk.”

The university faces a diverse set of risks, including cybersecurity, hospital liability, reduced government financial support, and earthquakes.

The ERM department had to overhaul systems to create a unified view of risk because its information and processes were not linked. Software enabled both an organizational picture of risk and highly detailed drilldowns on individual risks. Risk managers also developed tools for risk assessment, risk ranking, and risk modeling.

Better risk management has provided more than $100 million in annual cost savings and nearly $500 million in cost avoidance, according to UC officials.

UC drives ERM with risk management departments at each of its 10 locations and leverages university subject matter experts to form multidisciplinary workgroups that develop process improvements.

APQC, a standards quality organization, recognized UC as a top global ERM practice organization, and the university system has won other awards. The university says in 2010 it was the first nonfinancial organization to win credit-rating agency recognition of its ERM program.

Examples of How Technology Is Transforming Enterprise Risk Management

Business intelligence software has propelled major progress in enterprise risk management because the technology enables risk managers to bring their information together, analyze it, and forecast how risk scenarios would impact their business.

ERM organizations are using computing and data-handling advancements such as blockchain for new innovations in strengthening risk management. Following are case studies of a few examples.

ERM Case Study: Bank of New York Mellon

In 2021, the bank joined with Google Cloud to use machine learning and artificial intelligence to predict and reduce the risk that transactions in the $22 trillion U.S. Treasury market will fail to settle. Settlement failure means a buyer and seller do not exchange cash and securities by the close of business on the scheduled date.

The party that fails to settle is assessed a daily financial penalty, and a high level of settlement failures can indicate market liquidity problems and rising risk. BNY says that, on average, about 2 percent of transactions fail to settle.

The bank trained models with millions of trades to consider every factor that could result in settlement failure. The service uses market-wide intraday trading metrics, trading velocity, scarcity indicators, volume, the number of trades settled per hour, seasonality, issuance patterns, and other signals.

The bank said it predicts about 40 percent of settlement failures with 90 percent accuracy. But it also cautioned against overconfidence in the technology as the model continues to improve.

AI-driven forecasting reduces risk for BNY clients in the Treasury market and saves costs. For example, a predictive view of settlement risks helps bond dealers more accurately manage their liquidity buffers, avoid penalties, optimize their funding sources, and offset the risks of failed settlements. In the long run, such forecasting tools could improve the health of the financial market.

ERM Case Study: PwC

Consulting company PwC has leveraged a vast information storehouse known as a data lake to help its customers manage risk from suppliers.

A data lake stores both structured or unstructured information, meaning data in highly organized, standardized formats as well as unstandardized data. This means that everything from raw audio to credit card numbers can live in a data lake.

Using techniques pioneered in national security, PwC built a risk data lake that integrates information from client companies, public databases, user devices, and industry sources. Algorithms find patterns that can signify unidentified risks.

One of PwC’s first uses of this data lake was a program to help companies uncover risks from their vendors and suppliers. Companies can violate laws, harm their reputations, suffer fraud, and risk their proprietary information by doing business with the wrong vendor.

Today’s complex global supply chains mean companies may be several degrees removed from the source of this risk, which makes it hard to spot and mitigate. For example, a product made with outlawed child labor could be traded through several intermediaries before it reaches a retailer.

PwC’s service helps companies recognize risk beyond their primary vendors and continue to monitor that risk over time as more information enters the data lake.

ERM Case Study: Financial Services

As analytics have become a pillar of forecasting and risk management for banks and other financial institutions, a new risk has emerged: model risk . This refers to the risk that machine-learning models will lead users to an unreliable understanding of risk or have unintended consequences.

For example, a 6 percent drop in the value of the British pound over the course of a few minutes in 2016 stemmed from currency trading algorithms that spiralled into a negative loop. A Twitter-reading program began an automated selling of the pound after comments by a French official, and other selling algorithms kicked in once the currency dropped below a certain level.

U.S. banking regulators are so concerned about model risk that the Federal Reserve set up a model validation council in 2012 to assess the models that banks use in running risk simulations for capital adequacy requirements. Regulators in Europe and elsewhere also require model validation.

A form of managing risk from a risk-management tool, model validation is an effort to reduce risk from machine learning. The technology-driven rise in modeling capacity has caused such models to proliferate, and banks can use hundreds of models to assess different risks.

Model risk management can reduce rising costs for modeling by an estimated 20 to 30 percent by building a validation workflow, prioritizing models that are most important to business decisions, and implementing automation for testing and other tasks, according to McKinsey.

Streamline Your Enterprise Risk Management Efforts with Real-Time Work Management in Smartsheet

Empower your people to go above and beyond with a flexible platform designed to match the needs of your team — and adapt as those needs change.

The Smartsheet platform makes it easy to plan, capture, manage, and report on work from anywhere, helping your team be more effective and get more done. Report on key metrics and get real-time visibility into work as it happens with roll-up reports, dashboards, and automated workflows built to keep your team connected and informed.

When teams have clarity into the work getting done, there’s no telling how much more they can accomplish in the same amount of time. Try Smartsheet for free, today.

Discover why over 90% of Fortune 100 companies trust Smartsheet to get work done.

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

RiskandUncertainty →

No results found in working knowledge.

- Were any results found in one of the other content buckets on the left?

- Try removing some search filters.

- Use different search filters.

- Harvard Business School →

- Faculty & Research →

- July 2008 (Revised January 2012)

- HBS Case Collection

Enterprise Risk Management at Hydro One (A)

- Format: Print

- | Pages: 22

More from the Author

- Winter 2015

- Journal of Applied Corporate Finance

When One Size Doesn't Fit All: Evolving Directions in the Research and Practice of Enterprise Risk Management

- August 2014

- Faculty Research

Enterprise Risk Management at Hydro One (B): How Risky are Smart Meters?

Learning from the kursk submarine rescue failure: the case for pluralistic risk management.

- When One Size Doesn't Fit All: Evolving Directions in the Research and Practice of Enterprise Risk Management By: Anette Mikes and Robert S. Kaplan

- Enterprise Risk Management at Hydro One (B): How Risky are Smart Meters? By: Anette Mikes and Amram Migdal

- Learning from the Kursk Submarine Rescue Failure: the Case for Pluralistic Risk Management By: Anette Mikes and Amram Migdal

- Predict! Software Suite

- Training and Coaching

- Predict! Risk Controller

- Rapid Deployment

- Predict! Risk Analyser

- Predict! Risk Reporter

- Predict! Risk Visualiser

- Predict! Cloud Hosting

- BOOK A DEMO

- Risk Vision

- Win Proposals with Risk Analysis

- Case Studies

- Video Gallery

- White Papers

- Upcoming Events

- Past Events

Fehmarnbelt case study

. . . . . learn more

Lend Lease case study

ASC case study

Tornado IPT case study

LLW Repository case study

OHL case study

Babcock case study

HUMS case study

UK Chinook case study

- EMEA: +44 (0) 1865 987 466

- Americas: +1 (0) 437 269 0697

- APAC: +61 499 520 456

Subscribe for Updates

Copyright © 2024 risk decisions. All rights reserved.

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Company Registration No: 01878114

Powered by The Communications Group

- How it works

- Case studies

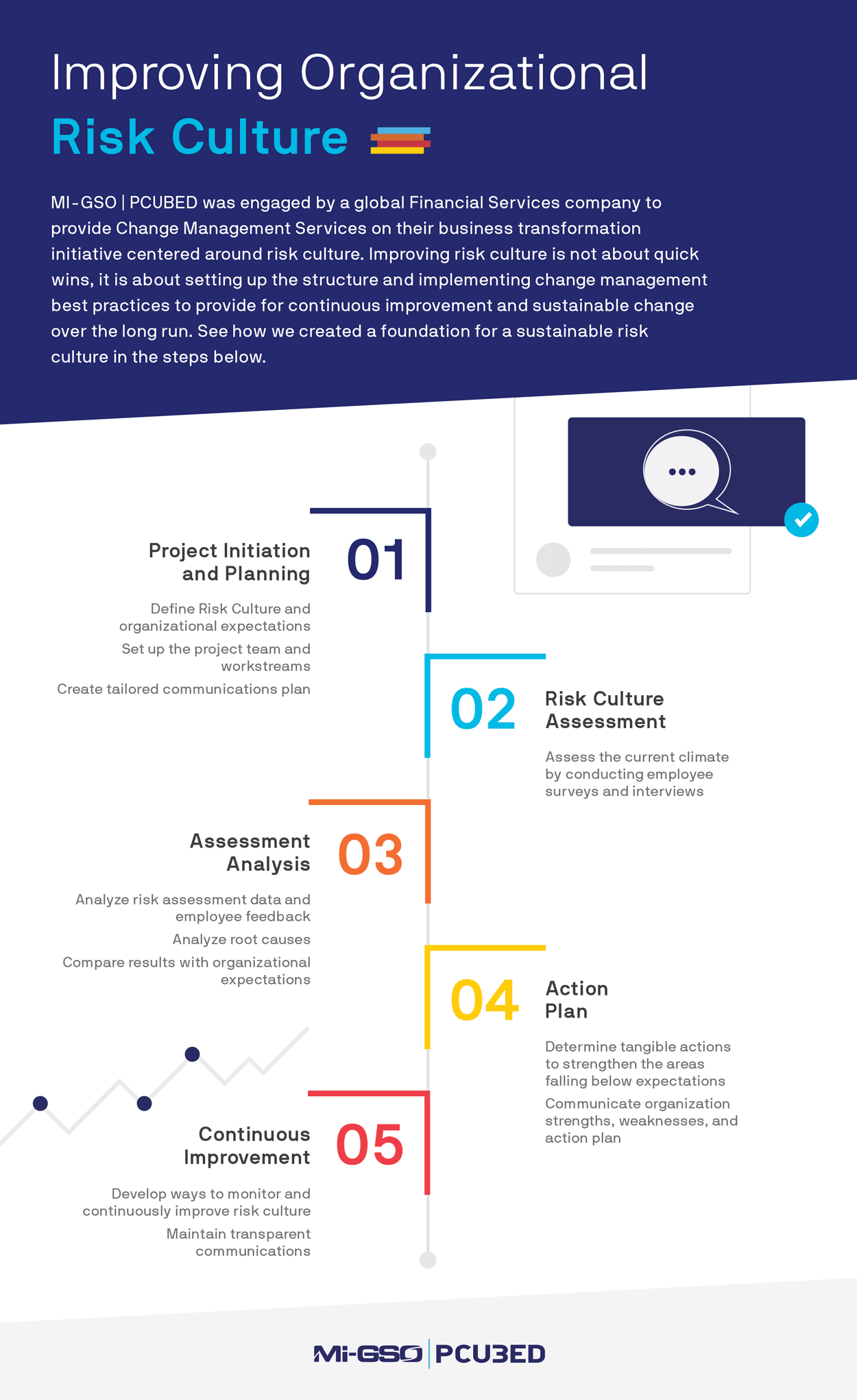

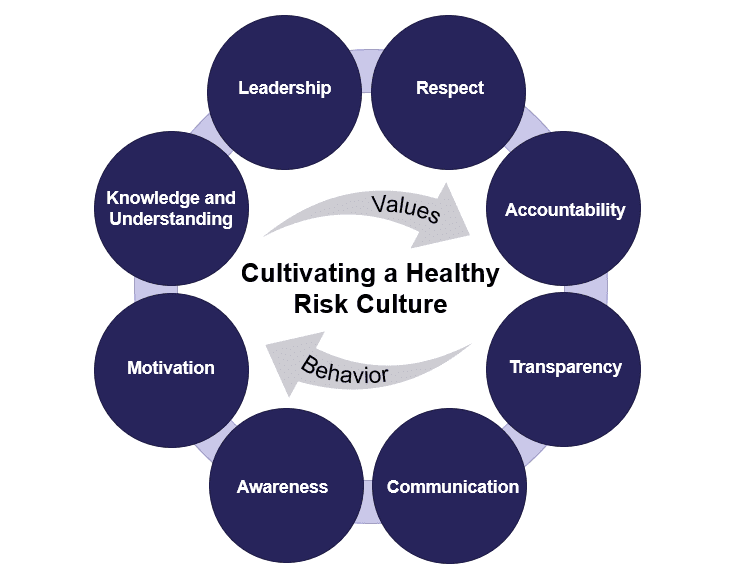

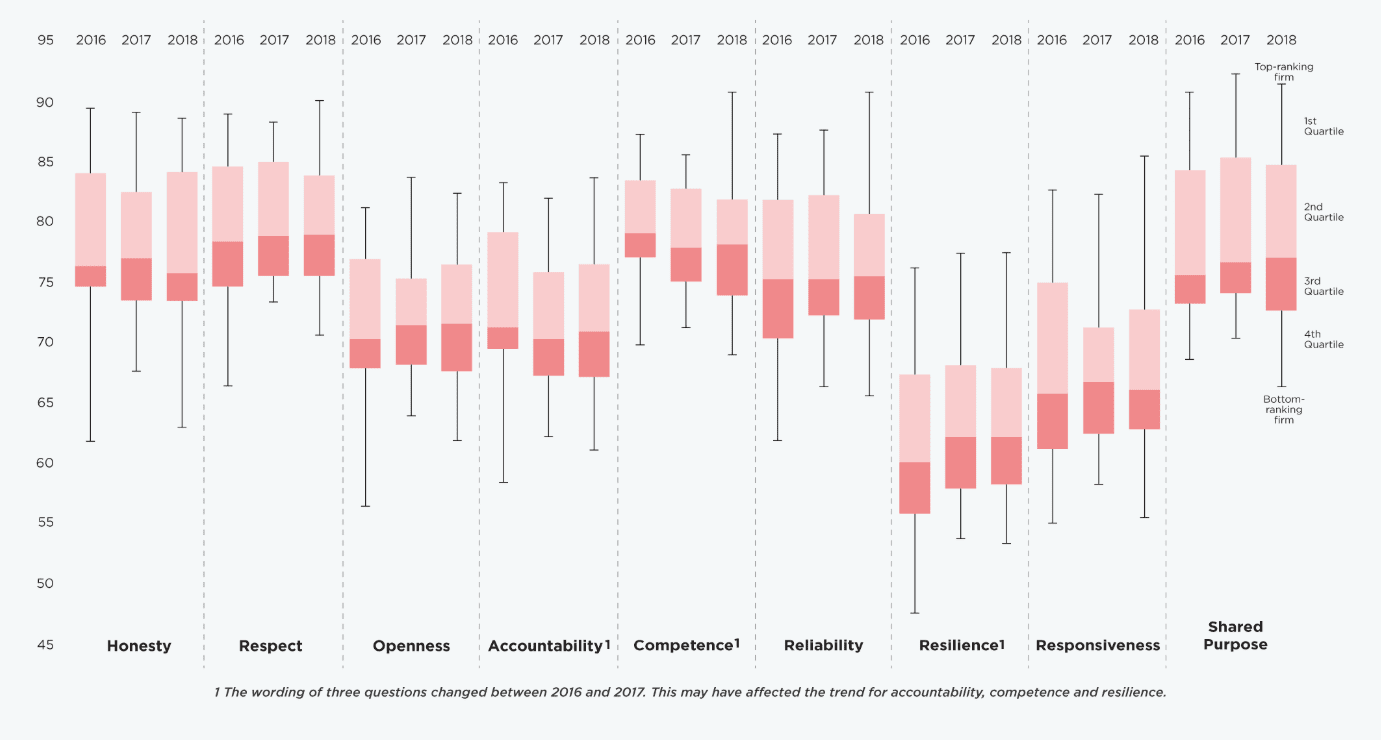

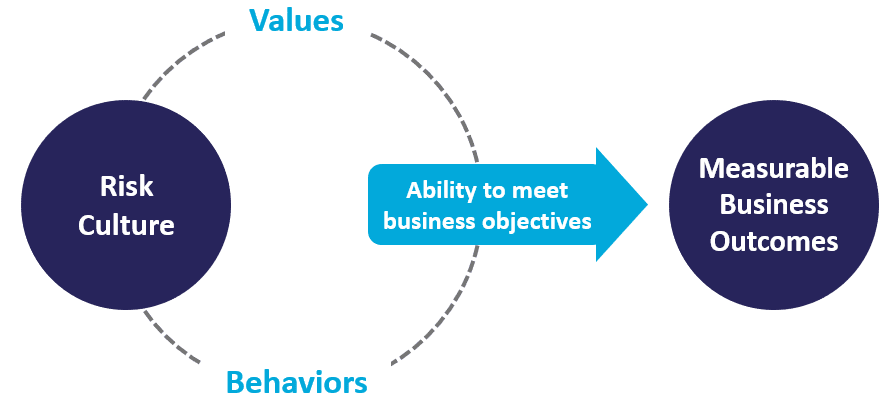

13 case studies on how risk managers are assessing their risk culture

Continuing on from last week's post, There’s no such thing as risk culture, or is there? , this is the third in a series of blogs in which we are summarising key insights gained from about 50 risk managers and CROs interviewed between December 2019 and May 2020.

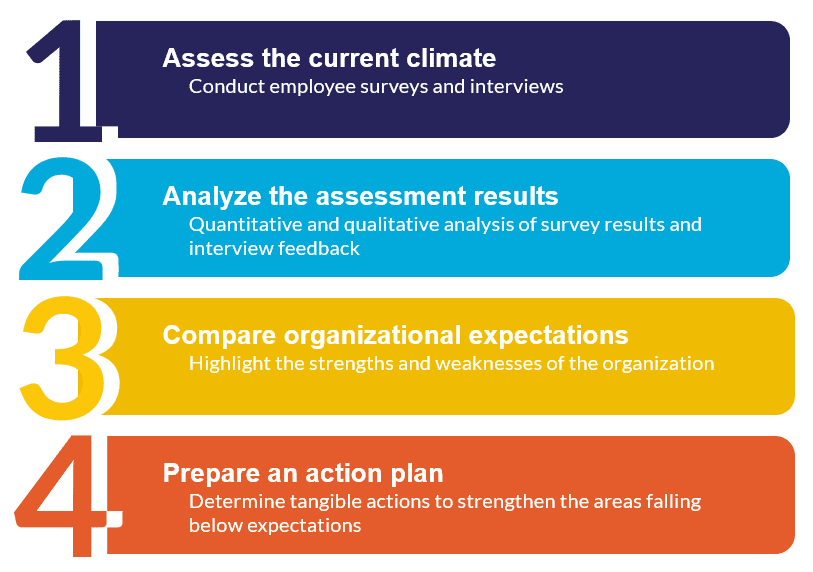

There are various techniques and different mindsets on how to assess and measure risk culture. We round-up the very best case studies, tools and templates used by risk managers around the world.

To survey or not to survey?

If you start from a base of assuming you need a survey (or perhaps you have an executive or board who want one), then you are faced with two main choices:

- Include a number of questions in a larger employee engagement/culture survey, probably being run by HR (as one of our Member organisations did, only to discover the results didn’t align with their anecdotal feedback and experiences)

- Conduct a dedicated risk culture survey, which might later be re-run as a benchmark (as one former CRO at an international airline did upon joining the organisation).

However, not everyone believes a survey is the way to go. Or at least, not a survey in isolation.

It’s a self-assessment tool, for one thing, as former Bank of Queensland CRO Peter Deans pointed out in a recent Intelligence contribution (Members: access this here ). You may not get the true risk picture you need, if you are only asking people if they believe they are making risk-aware decisions and are satisfied with the culture.

UK risk consultant Roger Noon shared with us a variety of tools risk managers can use in-house to help understand behaviours and diagnose culture (Members: access these tools here) . Of quantitative risk culture surveys, he says: “Survey instruments can also be used so long as you and your sponsors recognise that they are typically very blunt tools, often with poor validity. They're very ‘point in time and context’ driven, and they don't really provide you with objective observable output.

“However, they can be used to generate interesting data that creates helpful dialogue at the senior management table. They’re also useful to build engagement with the people that are part of the culture, and as part of a wider, triangulated set of data.”

In other instances, risk managers found it was not employees they initially needed to survey, but their board. Across different industries, different understandings of risk culture exist. If your board is asking about risk culture, it can be a good idea to check in that you (and they, among themselves) are all on the same page before beginning any broader projects. (Members: take a look at some sample questions about risk culture for the board here .)

So overt it’s covert

When it comes to an organisation’s overall approach to assessing and changing risk culture, there are also a few fundamentally different mindsets.

For some companies, the ‘culture overhaul’ needs to be a large project with lots of publicity and a big push from the top. In such cases, when it comes to driving change, extensive engagement and communications programs are planned, potentially including video.

We collected one case study, however, that stood out for its far more subtle and positive approach. In it, the head of risk at a large organisation with a few thousand staff spread across nine departments said there were a lot of preconceptions and quite a bit of nervousness around the idea of ‘working on risk culture’. This risk manager had therefore developed a different kind of self-assessment tool, which helped participants map their own risk culture using evidence-based attributes.

At the end of the initial meeting (which took no more than an hour and a half), participants had identified their own areas for improvement and incorporated culture elements into their future risk planning. (Members: access this case study here .)

Sometimes risk managers reach a point where they simply have to be realistic about their resources and prospects for implementing large scale change.

In another example from the Middle East, an expat risk manager found it was a case of trying to move his company’s risk culture at different ‘clock speeds’ across the organisation’s verticals, catering to different levels of appetite, awareness and need for change between delivery teams and the C-Suite. (Members: access this case study here .)

And, finally, sometimes risk managers reach a point where they simply have to be realistic about their resources and prospects for implementing large scale change. If there’s no appetite from the top for a risk culture shift, the risk manager will have an uphill battle. We’ve collected ideas from the former risk leader at a government utility, who devised tactics for embedding changes into existing systems and processes to deliver better risk outcomes for the business. (Members: access these ideas here .)

Measuring, reporting and dashboards

We found that the facet of culture where everybody most wanted to know what everybody else was measuring and what they were doing in terms of reporting and dashboards.

Again, there were a number of different methods shared by our Members and contributors, as well as contrasting views on what actually should be measured.

For example, is it redundant to actually measure ‘risk culture’? After all, isn’t the entire point of improving risk culture to improve risk outcomes? Why not just focus on measuring the risk outcomes, with culture change happening in the background to facilitate?

Certainly, this was the view of the former risk manager at a prominent United States government organisation, who spoke to us about building up their organisation’s risk capability over several years. (Members: read more on this here .)

Is it redundant to actually measure ‘risk culture’? After all, isn’t the entire point of improving risk culture to improve risk outcomes?

However, others saw value in tracking specific culture metrics, even if these goals were a means to an end. A scorecard or dashboard became a talking point to launch difficult conversations with different managers or executives, and the ability to show progress over time helped maintain momentum and commitment.

Over time, Peter Deans at BOQ developed and refined a ‘basket of risk culture measures’ along the same lines as the consumer price index, which he regularly updated and used to give leadership a ‘big picture view’ of how risk culture was doing.

Other contributing risk managers shared their scorecards and dashboards with us as templates, such as a scorecard example using a traffic light system across nine key risk indicators. We also collected ideas for dashboard metrics and a spreadsheet-based sunburst tool, alongside risk culture pillars.

On a final note, UK risk advisor Danny Wong shared a detailed case study on how to use data to drive an impactful risk narrative. For any risk managers who are striving to bring risk into line with many other functions in contemporary business – such as product development, sales, operations, and others that regularly use data strategically to inform decision making and best practice – this piece is essential reading. (Members: access this piece here .)

Risk Leadership Network’s Intelligence platform – our searchable database of peer-contributed case-studies, tools and templates – delves deeper into risk culture with more on diagnosing culture , addressing culture and ethics , and building a risk culture survey of boards . (Members only)

Are you an in-house risk manager who could benefit from collaborating with a global network of senior risk professionals talk to us about becoming a member today ., related posts you may be interested in.

5 ways to become a better leader in risk culture

There’s no such thing as risk culture, or is there?

Three useful tools to optimise a risk culture review

Get new posts by email.

Case Study: Companies Excelling in Risk Management

In this article

In the modern business landscape, navigating uncertainties and pitfalls is essential for sustainable growth and longevity. Effective risk management emerges as a shield against potential threats – and it also unlocks opportunities for innovation and advancement. In this article, we will explore risk management and its significance and criteria for excellence. We will also examine case studies of two companies that have excelled in this domain. Through these insights, we aim to glean valuable lessons and best practices. As such, businesses across diverse industries can fortify their risk management frameworks.

The Significance of Risk Management

Risk management is vital for the sustenance and prosperity of companies, regardless of their size or industry. At its core, it is the identification, assessment and mitigation of potential risks that may impede organisational objectives or lead to adverse outcomes. Having a robust risk management approach means businesses can safeguard their assets, reputation and bottom line.

The statistics are somewhat alarming. According to research , 69% of executives are not confident with their current risk management policies and practices. What’s more, only 36% of organisations have a formal enterprise risk management (ERM) programme.

Proactive risk management isn’t just a defensive measure; rather, it is necessary for sustainability and growth. With 62% of organisations experiencing a critical risk event in the last three years, it is important to be proactive. By identifying and addressing potential risks, organisations can become more resilient to external shocks and internal disruptions. This means they’re better able to survive through difficult times and maintain operational continuity. Moreover, a proactive stance enables companies to seize strategic advantages. It allows them to innovate, expand into new markets and capitalise on emerging trends with confidence.

Criteria for Excellence in Risk Management

Achieving excellence in risk management means adhering to several key criteria:

- Ability to Identify Risks: Exceptional risk management begins with identifying potential risks comprehensively. This involves a thorough understanding of both internal and external factors that could impact the organisation. It includes market volatility, regulatory changes, cybersecurity threats and operational vulnerabilities.

- Assessment of Risks: Once identified, risks must be assessed to gauge their potential impact and likelihood of occurrence. This involves using risk assessment methodologies like quantitative analysis, scenario planning and risk heat mapping, to prioritise risks based on their severity and urgency.

- Mitigation Strategies and Control Measures: Effective risk management relies on proactive mitigation strategies to minimise the likelihood of risk occurrence and mitigate its potential impact. This may involve implementing control measures, diversifying risk exposure, investing in risk transfer mechanisms such as insurance and enhancing resilience through business continuity planning.

- Adaptability to Change: Organisations need to be ready to adapt to emerging risks and changing circumstances. This requires a culture of continuous learning and improvement. This means lessons are learned from past experiences to enhance risk management practices and anticipate future challenges.

- Leadership Commitment: Effective leaders demonstrate a clear understanding of the importance of risk management. They know how to allocate adequate resources, support and incentives to prioritise risk management initiatives.

- Strong Risk Culture: A strong risk culture permeates every level of the organisation. This involves a mindset where risk management is viewed as everyone’s responsibility.

- Robust Risk Management Frameworks: Finally, excellence in risk management requires robust frameworks and processes to guide risk identification, assessment and mitigation efforts. This includes defining clear roles and responsibilities, implementing effective governance structures and leveraging technology and data analytics to enhance risk visibility and decision-making.

Company A: Case Study in Risk Management Excellence

Now, let’s take a look at a case study that highlights risk management excellence in practice.

ApexTech Solutions is a company known for its exemplary risk management practices. Founded in 2005 by visionary entrepreneur Sarah Lawson, ApexTech began as a small start-up in the tech industry. It specialises in software development and IT consulting services.

Over the years, under Lawson’s leadership, the company expanded its offerings and diversified into various sectors, including cybersecurity solutions, cloud computing and artificial intelligence. Today, ApexTech is a prominent player in the global technology market, serving clients ranging from small businesses to Fortune 500 companies.

Risk management strategies and successes

ApexTech’s journey to risk management excellence can be attributed to several key strategies and initiatives:

- Comprehensive Risk Assessment: ApexTech conducts regular and thorough risk assessments to identify potential threats and vulnerabilities across its operations.

- Investment in Technology and Innovation: ApexTech prioritises investments in cutting-edge technologies such as AI-driven analytics, predictive modelling and threat intelligence solutions.

- Customer-Centric Approach: ApexTech tailors its risk management solutions to meet specific needs and preferences. This fosters trust and long-term partnerships.

- Cybersecurity Measures: ApexTech has made cybersecurity a top priority. The company employs a multi-layered approach to cybersecurity to mitigate the risk of cyberattacks.

- Continual Improvement and Adaptation: ApexTech fosters a culture of continual improvement and adaptation. The company encourages feedback and collaboration among employees at all levels so they can identify areas for improvement and implement solutions to mitigate risks effectively.

By proactively identifying and addressing operational risks, such as supply chain disruptions and regulatory compliance challenges, ApexTech has maintained operational continuity and minimised potential disruptions to its business operations.

ApexTech Solutions serves as a compelling example of a company that has excelled in risk management excellence by embracing proactive strategies, leveraging advanced technologies and fostering a culture of innovation and adaptation.

Company B: Case Study in Risk Management Excellence

TerraSafe Pharmaceuticals is a renowned company in the pharmaceutical industry, dedicated to developing and manufacturing innovative medications to improve global health outcomes. Established in 1998 by Dr Elena Chen, TerraSafe initially focused on the production of generic drugs to address critical healthcare needs.

Over the years, the company has expanded its portfolio to include novel biopharmaceuticals and speciality medications.

TerraSafe Pharmaceuticals has a holistic approach to identifying, assessing and mitigating risks across its operations:

- Rigorous Quality Assurance Standards: TerraSafe prioritises stringent quality assurance measures throughout the drug development and manufacturing process. This ensures product safety, efficacy and compliance with regulatory requirements.

- Investment in Research and Development (R&D): TerraSafe allocates significant resources to research and development initiatives. These are aimed at advancing scientific knowledge and discovering breakthrough therapies. With its culture of innovation and collaboration, the company mitigates the risk of product obsolescence.

- Regulatory Compliance and Risk Monitoring: TerraSafe maintains a dedicated regulatory affairs department. This team stays abreast of evolving regulatory requirements and industry standards. They monitor regulatory changes proactively and engage with regulatory authorities to ensure timely compliance with applicable laws and standards. This reduces the risk of non-compliance penalties and legal disputes.

- Supply Chain Resilience: TerraSafe works closely with its suppliers and logistics partners to assess and mitigate supply chain risks like raw material shortages, transportation disruptions and geopolitical instability. It implements contingency planning and diversification of sourcing strategies.

- Focus on Patient Safety and Ethical Practices: The company adheres to stringent ethical guidelines and clinical trial protocols to protect patient welfare and maintain public trust in its products and services.

By investing in R&D and adhering to rigorous quality assurance standards, TerraSafe has successfully developed and commercialised several breakthrough medications that address unmet medical needs and improve patient outcomes. What’s more, the company’s proactive approach to regulatory compliance has facilitated the timely approval and market authorisation of its products in key global markets. This has enabled the company to expand its geographic footprint and reach new patient populations.

Key Takeaways and Best Practices

Despite being in different industries, both companies share similarities. Both ApexTech and TerraSafe Pharmaceuticals know the importance of proactive risk management. They have procedures in place that work to identify, assess and mitigate risks before they escalate. What’s more, both companies are led by visionary leaders who set the tone for decision-making. They prioritise building a strong risk culture with all employees knowing their role in risk management.

Best practices and strategies employed

- Conducting Regular Risk Assessments: Both companies conduct regular and comprehensive risk assessments to identify potential threats and vulnerabilities across their operations.

- Investing in Training and Education: Both invest in training and education programmes so that employees are equipped with the knowledge and skills necessary to identify and manage risks effectively. Employees at all levels contribute to risk management efforts.

- Collaboration and Communication: Both companies know the importance of collaboration and communication in risk management. They create channels for open dialogue and information sharing. Stakeholders collaborate on risk identification, assessment and mitigation efforts.

- Continual Improvement: Both companies have a culture of continual improvement. They encourage feedback and innovation to adapt to changing circumstances and emerging risks.

- Tailored Risk Management Approaches: Both companies develop customised risk management frameworks and strategies that align with their objectives and priorities.

Emerging Trends in Risk Management

One of the most prominent trends in risk management is the increasing integration of technology into risk management processes. Advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning and automation are revolutionising risk assessment, prediction and mitigation. These technologies mean companies can analyse vast amounts of data in real time. This allows them to identify patterns and trends and predict potential risks more accurately.

Data analytics is another key trend reshaping risk management practices. Companies are leveraging big data analytics tools and techniques to gain deeper insights. By analysing historical data and real-time information, they can identify emerging risks, detect anomalies and make more informed risk management decisions.

Cybersecurity risks have become a major concern. Threats such as data breaches, ransomware attacks and phishing scams pose significant risks to companies’ data, operation and reputation. Companies are investing heavily in cybersecurity measures and adopting proactive approaches to protect their digital assets and mitigate cyber risks.

Companies are integrating global risk management into their overall risk management strategy too. They are monitoring global developments, assessing the impact of global risks on their business operations and developing contingency plans.

The Role of Leadership

Leadership plays a pivotal role in shaping organisational culture and driving initiatives that promote risk management excellence. Effective leaders recognise the importance of risk management but also actively champion its integration into the fabric of the organisation. Effective leaders:

- Set the Tone: Leaders set the tone by articulating a clear vision and commitment to risk management from the top down.

- Lead by Example: Leaders demonstrate their own commitment to risk management through their actions and decisions.

- Empower Employees: Leaders empower employees at all levels to actively participate in risk management efforts. They encourage employees to voice their concerns and contribute.

- Provide Resources and Support: Effective leaders invest in training and development programmes to enhance employees’ risk management skills and knowledge.

- Encourage Innovation: Leaders encourage employees to think creatively and experiment with new approaches to risk management.

- Promote Continuous Improvement: Leaders create opportunities for reflection and evaluation to identify areas for improvement and drive learning.

Encouraging a Risk-Aware Culture

For organisations to identify, assess and mitigate risks at all levels effectively, they need to encourage a risk-aware culture. Here are some tips for encouraging a risk-aware culture:

Communication and transparency:

- Encourage open communication channels where employees feel comfortable discussing risks and raising concerns.

- Provide regular updates on the organisation’s risk landscape, including emerging risks and mitigation strategies.

- Foster transparency in decision-making processes, particularly regarding risk-related decisions.

Education and training:

- Provide comprehensive training programmes on risk management principles, processes and tools for employees at all levels.

- Offer specialised training sessions on specific risk areas relevant to employees’ roles and responsibilities.

- Incorporate real-life case studies and examples to illustrate the importance of risk awareness and effective risk management.

Empowerment and ownership:

- Empower employees to take ownership of risk management within their respective areas of expertise.

- Encourage employees to identify and assess risks in their day-to-day activities and propose mitigation strategies.

- Recognise and reward employees who demonstrate proactive risk awareness and contribute to effective risk management practices.

Integration into performance management:

- Include risk management objectives and key performance indicators (KPIs) in employee performance evaluations.

- Link performance bonuses or incentives to successful risk management outcomes and adherence to risk management protocols.

- Provide feedback and coaching to employees on their risk management performance, highlighting areas for improvement and best practices.

Challenges in Risk Management

Challenges in risk management are inevitable, even for companies excelling in this domain. Despite their proactive efforts, all organisations encounter obstacles that can impede their risk management practices. Here are some common challenges and strategies for addressing them:

Complexity and interconnectedness:

- Challenge: The modern business environment is increasingly complex and interconnected, making it challenging for organisations to anticipate and mitigate all potential risks comprehensively.

- Strategy: Implement a holistic risk management approach that considers both internal and external factors impacting the organisation. Create cross-functional collaboration and information sharing to gain a comprehensive understanding of risks across departments and business units.

Rapidly evolving risks:

- Challenge: Risks are constantly evolving due to technological advancements, regulatory changes and global events such as pandemics or geopolitical shifts. Organisations may struggle to keep pace with emerging risks and adapt their risk management strategies accordingly.

- Strategy: Stay informed about emerging trends and developments that may impact the organisation’s risk landscape. Maintain flexibility and agility in risk management processes to respond promptly to new challenges.

Resource constraints:

- Challenge: Limited resources, including budgetary constraints and staffing limitations, can hinder organisations’ ability to invest adequately in risk management initiatives and tools.

- Strategy: Prioritise risk management activities based on their potential impact on organisational objectives and allocate resources accordingly. Leverage technology and automation to streamline risk management processes and maximise efficiency.

Compliance and regulatory burden:

- Challenge: Meeting regulatory requirements and compliance standards can be burdensome and complex.

- Strategy: Stay abreast of regulatory developments and ensure compliance with applicable laws and regulations. Implement robust governance frameworks and internal controls to demonstrate regulatory compliance and mitigate legal and reputational risks. Invest in compliance training and education for employees.

Human factors and behavioural biases:

- Challenge: Human factors such as cognitive biases, organisational politics and resistance to change can undermine effective risk management practices, leading to decision-making errors and oversight of critical risks.

- Strategy: Raise awareness about common cognitive biases and behavioural tendencies that may influence risk perception and decision-making. Create a culture of psychological safety where employees feel comfortable challenging assumptions and raising concerns about potential risks.

Conclusion: Striving for Excellence

In this article, we have explored the importance of effective risk management for businesses. We have delved into the criteria for excellence in risk management, showcasing companies such as ApexTech Solutions and TerraSafe Pharmaceuticals that exemplify these principles through their proactive strategies and robust frameworks.

From embracing technology and fostering a culture of innovation to prioritising regulatory compliance and empowering employees, these companies have demonstrated remarkable achievements in navigating complex risk landscapes and achieving sustainable success.

However, it’s essential to recognise that even companies excelling in risk management face challenges. By acknowledging these and implementing strategies to address them, organisations can enhance their resilience and effectiveness in managing risks over the long term.

Assessing Risk

Study online and gain a full CPD certificate posted out to you the very next working day.

Take a look at this course

About the author

Louise Woffindin

Louise is a writer and translator from Sheffield. Before turning to writing, she worked as a secondary school language teacher. Outside of work, she is a keen runner and also enjoys reading and walking her dog Chaos.

Similar posts

Top Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Diseases and How to Mitigate Them

The Role of Therapy and Counselling in Anger Management

Case Study: Inspirational Stories of Individuals Regaining Confidence

How Play Enhances Cognitive, Social and Physical Development

Celebrating our clients and partners.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

A case study exploring field-level risk assessments as a leading safety indicator

Lead research behavioral scientist and research behavioral scientist, respectively, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

B.P. Connor

J. vendetti.

Manager, mining operations, Solvay Soda Ash & Derivatives North America, Green River, WY, USA

CSP, Mine production superintendent, Solvay Chemicals Inc., Green River, WY, USA