Nursing: Literature Review

- Required Texts

- Writing Assistance and Organizing & Citing References

- NCLEX Resources

- Literature Review

- MSN Students

- Physical Examination

- Drug Information

- Professional Organizations

- Mobile Apps

- Evidence-based Medicine

- Certifications

- Recommended Nursing Textbooks

- DNP Students

- Conducting Research

- Scoping Reviews

- Systematic Reviews

- Distance Education Students

- Ordering from your Home Library

Good Place to Start: Citation Databases

Interdisciplinary Citation Databases:

A good place to start your research is to search a research citation database to view the scope of literature available on your topic.

TIP #1: SEED ARTICLE Begin your research with a "seed article" - an article that strongly supports your research topic. Then use a citation database to follow the studies published by finding articles which have cited that article, either because they support it or because they disagree with it.

TIP #2: SNOWBALLING Snowballing is the process where researchers will begin with a select number of articles they have identified relevant/strongly supports their topic and then search each articles' references reviewing the studies cited to determine if they are relevant to your research.

BONUS POINTS: This process also helps identify key highly cited authors within a topic to help establish the "experts" in the field.

Begin by constructing a focused research question to help you then convert it into an effective search strategy.

- Identify keywords or synonyms

- Type of study/resources

- Which database(s) to search

- Asking a Good Question (PICO)

- PICO - AHRQ

- PICO - Worksheet

- What Is a PICOT Question?

Seminal Works: Search Key Indexing/Citation Databases

- Google Scholar

- Web of Science

TIP – How to Locate Seminal Works

- DO NOT: Limit by date range or you might overlook the seminal works

- DO: Look at highly cited references (Seminal articles are frequently referred to “cited” in the research)

- DO: Search citation databases like Scopus, Web of Science and Google Scholar

Web Resources

What is a literature review?

A literature review is a comprehensive and up-to-date overview of published information on a subject area. Conducting a literature review demands a careful examination of a body of literature that has been published that helps answer your research question (See PICO). Literature reviewed includes scholarly journals, scholarly books, authoritative databases, primary sources and grey literature.

A literature review attempts to answer the following:

- What is known about the subject?

- What is the chronology of knowledge about my subject?

- Are there any gaps in the literature?

- Is there a consensus/debate on issues?

- Create a clear research question/statement

- Define the scope of the review include limitations (i.e. gender, age, location, nationality...)

- Search existing literature including classic works on your topic and grey literature

- Evaluate results and the evidence (Avoid discounting information that contradicts your research)

- Track and organize references

- How to conduct an effective literature search.

- Social Work Literature Review Guidelines (OWL Purdue Online Writing Lab)

What is PICO?

The PICO model can help you formulate a good clinical question. Sometimes it's referred to as PICO-T, containing an optional 5th factor.

Search Example

- << Previous: NCLEX Resources

- Next: MSN Students >>

- Last Updated: Apr 9, 2024 1:30 PM

- URL: https://guides.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/Nursing

- Himmelfarb Intranet

- Privacy Notice

- Terms of Use

- GW is committed to digital accessibility. If you experience a barrier that affects your ability to access content on this page, let us know via the Accessibility Feedback Form .

- Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library

- 2300 Eye St., NW, Washington, DC 20037

- Phone: (202) 994-2850

- [email protected]

- https://himmelfarb.gwu.edu

Nursing: How to Write a Literature Review

- Traditional or Narrative Literature Review

Getting started

1. start with your research question, 2. search the literature, 3. read & evaluate, 4. finalize results, 5. write & revise, brainfuse online tutoring and writing review.

- RESEARCH HELP

The best way to approach your literature review is to break it down into steps. Remember, research is an iterative process, not a linear one. You will revisit steps and revise along the way. Get started with the handout, information, and tips from various university Writing Centers below that provides an excellent overview. Then move on to the specific steps recommended on this page.

- UNC- Chapel Hill Writing Center Literature Review Handout, from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- University of Wisconsin-Madison Writing Center Learn how to write a review of literature, from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- University of Toronto-- Writing Advice The Literature Review: A few tips on conducting it, from the University of Toronto.

- Begin with a topic.

- Understand the topic.

- Familiarize yourself with the terminology. Note what words are being used and keep track of these for use as database search keywords.

- See what research has been done on this topic before you commit to the topic. Review articles can be helpful to understand what research has been done .

- Develop your research question. (see handout below)

- How comprehensive should it be?

- Is it for a course assignment or a dissertation?

- How many years should it cover?

- Developing a good nursing research question Handout. Reviews PICO method and provides search tips.

Your next step is to construct a search strategy and then locate & retrieve articles.

- There are often 2-4 key concepts in a research question.

- Search for primary sources (original research articles.)

- These are based on the key concepts in your research question.

- Remember to consider synonyms and related terms.

- Which databases to search?

- What limiters should be applied (peer-reviewed, publication date, geographic location, etc.)?

Review articles (secondary sources)

Use to identify literature on your topic, the way you would use a bibliography. Then locate and retrieve the original studies discussed in the review article. Review articles are considered secondary sources.

- Once you have some relevant articles, review reference lists to see if there are any useful articles.

- Which articles were written later and have cited some of your useful articles? Are these, in turn, articles that will be useful to you?

- Keep track of what terms you used and what databases you searched.

- Use database tools such as save search history in EBSCO to help.

- Keep track of the citations for the articles you will be using in your literature review.

- Use RefWorks or another method of tracking this information.

- Database Search Strategy Worksheet Handout. How to construct a search.

- TUTORIAL: How to do a search based on your research question This is a self-paced, interactive tutorial that reviews how to construct and perform a database search in CINAHL.

The next step is to read, review, and understand the articles.

- Start by reviewing abstracts.

- Make sure you are selecting primary sources (original research articles).

- Note any keywords authors report using when searching for prior studies.

- You will need to evaluate and critique them and write a synthesis related to your research question.

- Consider using a matrix to organize and compare and contrast the articles .

- Which authors are conducting research in this area? Search by author.

- Are there certain authors’ whose work is cited in many of your articles? Did they write an early, seminal article that is often cited?

- Searching is a cyclical process where you will run searches, review results, modify searches, run again, review again, etc.

- Critique articles. Keep or exclude based on whether they are relevant to your research question.

- When you have done a thorough search using several databases plus Google Scholar, using appropriate keywords or subject terms, plus author’s names, and you begin to find the same articles over and over.

- Remember to consider the scope of your project and the length of your paper. A dissertation will have a more exhaustive literature review than an 8 page paper, for example.

- What are common findings among each group or where do they disagree?

- Identify common themes. Identify controversial or problematic areas in the research.

- Use your matrix to organize this.

- Once you have read and re-read your articles and organized your findings, you are ready to begin the process of writing the literature review.

2. Synthesize. (see handout below)

- Include a synthesis of the articles you have chosen for your literature review.

- A literature review is NOT a list or a summary of what has been written on a particular topic.

- It analyzes the articles in terms of how they relate to your research question.

- While reading, look for similarities and differences (compare and contrast) among the articles. You will create your synthesis from this.

- Synthesis Examples Handout. Sample excerpts that illustrate synthesis.

Regis Online students have access to Brainfuse. Brainfuse is an online tutoring service available through a link in Moodle. Meet with a tutor in a live session or submit your paper for review.

- Brainfuse Tutoring and Writing Assistance for Regis Online Students by Tricia Reinhart Last Updated Oct 26, 2023 81 views this year

- << Previous: Traditional or Narrative Literature Review

- Next: eBooks >>

- Last Updated: Feb 21, 2024 12:05 PM

- URL: https://libguides.regiscollege.edu/nursing_litreview

University Library

- Research Guides

- Literature Reviews

- Evidence-Based Practice

- Books & Media

What is a Literature Review?

Key questions for a literature review, examples of literature reviews, useful links, evidence matrix for literature reviews.

- Annotated Bibliographies

The Scholarly Conversation

A literature review provides an overview of previous research on a topic that critically evaluates, classifies, and compares what has already been published on a particular topic. It allows the author to synthesize and place into context the research and scholarly literature relevant to the topic. It helps map the different approaches to a given question and reveals patterns. It forms the foundation for the author’s subsequent research and justifies the significance of the new investigation.

A literature review can be a short introductory section of a research article or a report or policy paper that focuses on recent research. Or, in the case of dissertations, theses, and review articles, it can be an extensive review of all relevant research.

- The format is usually a bibliographic essay; sources are briefly cited within the body of the essay, with full bibliographic citations at the end.

- The introduction should define the topic and set the context for the literature review. It will include the author's perspective or point of view on the topic, how they have defined the scope of the topic (including what's not included), and how the review will be organized. It can point out overall trends, conflicts in methodology or conclusions, and gaps in the research.

- In the body of the review, the author should organize the research into major topics and subtopics. These groupings may be by subject, (e.g., globalization of clothing manufacturing), type of research (e.g., case studies), methodology (e.g., qualitative), genre, chronology, or other common characteristics. Within these groups, the author can then discuss the merits of each article and analyze and compare the importance of each article to similar ones.

- The conclusion will summarize the main findings, make clear how this review of the literature supports (or not) the research to follow, and may point the direction for further research.

- The list of references will include full citations for all of the items mentioned in the literature review.

A literature review should try to answer questions such as

- Who are the key researchers on this topic?

- What has been the focus of the research efforts so far and what is the current status?

- How have certain studies built on prior studies? Where are the connections? Are there new interpretations of the research?

- Have there been any controversies or debate about the research? Is there consensus? Are there any contradictions?

- Which areas have been identified as needing further research? Have any pathways been suggested?

- How will your topic uniquely contribute to this body of knowledge?

- Which methodologies have researchers used and which appear to be the most productive?

- What sources of information or data were identified that might be useful to you?

- How does your particular topic fit into the larger context of what has already been done?

- How has the research that has already been done help frame your current investigation ?

Example of a literature review at the beginning of an article: Forbes, C. C., Blanchard, C. M., Mummery, W. K., & Courneya, K. S. (2015, March). Prevalence and correlates of strength exercise among breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer survivors . Oncology Nursing Forum, 42(2), 118+. Retrieved from http://go.galegroup.com.sonoma.idm.oclc.org/ps/i.do?p=HRCA&sw=w&u=sonomacsu&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CA422059606&asid=27e45873fddc413ac1bebbc129f7649c Example of a comprehensive review of the literature: Wilson, J. L. (2016). An exploration of bullying behaviours in nursing: a review of the literature. British Journal Of Nursing , 25 (6), 303-306. For additional examples, see:

Galvan, J., Galvan, M., & ProQuest. (2017). Writing literature reviews: A guide for students of the social and behavioral sciences (Seventh ed.). [Electronic book]

Pan, M., & Lopez, M. (2008). Preparing literature reviews: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (3rd ed.). Glendale, CA: Pyrczak Pub. [ Q180.55.E9 P36 2008]

- Write a Literature Review (UCSC)

- Literature Reviews (Purdue)

- Literature Reviews: overview (UNC)

- Review of Literature (UW-Madison)

The Evidence Matrix can help you organize your research before writing your lit review. Use it to identify patterns and commonalities in the articles you have found--similar methodologies ? common theoretical frameworks ? It helps you make sure that all your major concepts covered. It also helps you see how your research fits into the context of the overall topic.

- Evidence Matrix Special thanks to Dr. Cindy Stearns, SSU Sociology Dept, for permission to use this Matrix as an example.

- << Previous: Misc

- Next: Annotated Bibliographies >>

- Last Updated: Jan 8, 2024 2:58 PM

- URL: https://libguides.sonoma.edu/nursing

- University of Detroit Mercy

- Health Professions

- Writing a Literature Review

- Find Articles (Databases)

- Evidence Based Nursing

- Searching Tips

- Books / eBooks

- Nursing Theory

- Adult-Gerontology Clinical Nurse Specialist

- Doctor of Nursing Practice

- NHL and CNL (Clinical Nurse Leader)

- Nurse Anesthesia

- Nursing Education

- Nurse Practitioner (FNP / ENP)

- Undergraduate Nursing - Clinical Reference Library

- General Writing Support

- Creating & Printing Posters

- Statistics: Health / Medical

- Health Measurement Instruments

- Streaming Video

- Anatomy Resources

- Database & Library Help

- Web Resources

- Evaluating Websites

- Medical / Nursing Apps & Mobile Sites

- Faculty Publications

Literature Review Overview

What is a Literature Review? Why Are They Important?

A literature review is important because it presents the "state of the science" or accumulated knowledge on a specific topic. It summarizes, analyzes, and compares the available research, reporting study strengths and weaknesses, results, gaps in the research, conclusions, and authors’ interpretations.

Tips and techniques for conducting a literature review are described more fully in the subsequent boxes:

- Literature review steps

- Strategies for organizing the information for your review

- Literature reviews sections

- In-depth resources to assist in writing a literature review

- Templates to start your review

- Literature review examples

Literature Review Steps

Graphic used with permission: Torres, E. Librarian, Hawai'i Pacific University

1. Choose a topic and define your research question

- Try to choose a topic of interest. You will be working with this subject for several weeks to months.

- Ideas for topics can be found by scanning medical news sources (e.g MedPage Today), journals / magazines, work experiences, interesting patient cases, or family or personal health issues.

- Do a bit of background reading on topic ideas to familiarize yourself with terminology and issues. Note the words and terms that are used.

- Develop a focused research question using PICO(T) or other framework (FINER, SPICE, etc - there are many options) to help guide you.

- Run a few sample database searches to make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow.

- If possible, discuss your topic with your professor.

2. Determine the scope of your review

The scope of your review will be determined by your professor during your program. Check your assignment requirements for parameters for the Literature Review.

- How many studies will you need to include?

- How many years should it cover? (usually 5-7 depending on the professor)

- For the nurses, are you required to limit to nursing literature?

3. Develop a search plan

- Determine which databases to search. This will depend on your topic. If you are not sure, check your program specific library website (Physician Asst / Nursing / Health Services Admin) for recommendations.

- Create an initial search string using the main concepts from your research (PICO, etc) question. Include synonyms and related words connected by Boolean operators

- Contact your librarian for assistance, if needed.

4. Conduct searches and find relevant literature

- Keep notes as you search - tracking keywords and search strings used in each database in order to avoid wasting time duplicating a search that has already been tried

- Read abstracts and write down new terms to search as you find them

- Check MeSH or other subject headings listed in relevant articles for additional search terms

- Scan author provided keywords if available

- Check the references of relevant articles looking for other useful articles (ancestry searching)

- Check articles that have cited your relevant article for more useful articles (descendancy searching). Both PubMed and CINAHL offer Cited By links

- Revise the search to broaden or narrow your topic focus as you peruse the available literature

- Conducting a literature search is a repetitive process. Searches can be revised and re-run multiple times during the process.

- Track the citations for your relevant articles in a software citation manager such as RefWorks, Zotero, or Mendeley

5. Review the literature

- Read the full articles. Do not rely solely on the abstracts. Authors frequently cannot include all results within the confines of an abstract. Exclude articles that do not address your research question.

- While reading, note research findings relevant to your project and summarize. Are the findings conflicting? There are matrices available than can help with organization. See the Organizing Information box below.

- Critique / evaluate the quality of the articles, and record your findings in your matrix or summary table. Tools are available to prompt you what to look for. (See Resources for Appraising a Research Study box on the HSA, Nursing , and PA guides )

- You may need to revise your search and re-run it based on your findings.

6. Organize and synthesize

- Compile the findings and analysis from each resource into a single narrative.

- Using an outline can be helpful. Start broad, addressing the overall findings and then narrow, discussing each resource and how it relates to your question and to the other resources.

- Cite as you write to keep sources organized.

- Write in structured paragraphs using topic sentences and transition words to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

- Don't present one study after another, but rather relate one study's findings to another. Speak to how the studies are connected and how they relate to your work.

Organizing Information

Options to assist in organizing sources and information :

1. Synthesis Matrix

- helps provide overview of the literature

- information from individual sources is entered into a grid to enable writers to discern patterns and themes

- article summary, analysis, or results

- thoughts, reflections, or issues

- each reference gets its own row

- mind maps, concept maps, flowcharts

- at top of page record PICO or research question

- record major concepts / themes from literature

- list concepts that branch out from major concepts underneath - keep going downward hierarchically, until most specific ideas are recorded

- enclose concepts in circles and connect the concept with lines - add brief explanation as needed

3. Summary Table

- information is recorded in a grid to help with recall and sorting information when writing

- allows comparing and contrasting individual studies easily

- purpose of study

- methodology (study population, data collection tool)

Efron, S. E., & Ravid, R. (2019). Writing the literature review : A practical guide . Guilford Press.

Literature Review Sections

- Lit reviews can be part of a larger paper / research study or they can be the focus of the paper

- Lit reviews focus on research studies to provide evidence

- New topics may not have much that has been published

* The sections included may depend on the purpose of the literature review (standalone paper or section within a research paper)

Standalone Literature Review (aka Narrative Review):

- presents your topic or PICO question

- includes the why of the literature review and your goals for the review.

- provides background for your the topic and previews the key points

- Narrative Reviews: tmay not have an explanation of methods.

- include where the search was conducted (which databases) what subject terms or keywords were used, and any limits or filters that were applied and why - this will help others re-create the search

- describe how studies were analyzed for inclusion or exclusion

- review the purpose and answer the research question

- thematically - using recurring themes in the literature

- chronologically - present the development of the topic over time

- methodological - compare and contrast findings based on various methodologies used to research the topic (e.g. qualitative vs quantitative, etc.)

- theoretical - organized content based on various theories

- provide an overview of the main points of each source then synthesize the findings into a coherent summary of the whole

- present common themes among the studies

- compare and contrast the various study results

- interpret the results and address the implications of the findings

- do the results support the original hypothesis or conflict with it

- provide your own analysis and interpretation (eg. discuss the significance of findings; evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of the studies, noting any problems)

- discuss common and unusual patterns and offer explanations

- stay away from opinions, personal biases and unsupported recommendations

- summarize the key findings and relate them back to your PICO/research question

- note gaps in the research and suggest areas for further research

- this section should not contain "new" information that had not been previously discussed in one of the sections above

- provide a list of all the studies and other sources used in proper APA 7

Literature Review as Part of a Research Study Manuscript:

- Compares the study with other research and includes how a study fills a gap in the research.

- Focus on the body of the review which includes the synthesized Findings and Discussion

Literature Reviews vs Systematic Reviews

Systematic Reviews are NOT the same as a Literature Review:

Literature Reviews:

- Literature reviews may or may not follow strict systematic methods to find, select, and analyze articles, but rather they selectively and broadly review the literature on a topic

- Research included in a Literature Review can be "cherry-picked" and therefore, can be very subjective

Systematic Reviews:

- Systemic reviews are designed to provide a comprehensive summary of the evidence for a focused research question

- rigorous and strictly structured, using standardized reporting guidelines (e.g. PRISMA, see link below)

- uses exhaustive, systematic searches of all relevant databases

- best practice dictates search strategies are peer reviewed

- uses predetermined study inclusion and exclusion criteria in order to minimize bias

- aims to capture and synthesize all literature (including unpublished research - grey literature) that meet the predefined criteria on a focused topic resulting in high quality evidence

Literature Review Examples

- Breastfeeding initiation and support: A literature review of what women value and the impact of early discharge (2017). Women and Birth : Journal of the Australian College of Midwives

- Community-based participatory research to promote healthy diet and nutrition and prevent and control obesity among African-Americans: A literature review (2017). Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities

- Vitamin D deficiency in individuals with a spinal cord injury: A literature review (2017). Spinal Cord

Resources for Writing a Literature Review

These sources have been used in developing this guide.

Resources Used on This Page

Aveyard, H. (2010). Doing a literature review in health and social care : A practical guide . McGraw-Hill Education.

Purdue Online Writing Lab. (n.d.). Writing a literature review . Purdue University. https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/conducting_research/writing_a_literature_review.html

Torres, E. (2021, October 21). Nursing - graduate studies research guide: Literature review. Hawai'i Pacific University Libraries. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://hpu.libguides.com/c.php?g=543891&p=3727230

- << Previous: General Writing Support

- Next: Creating & Printing Posters >>

- Last Updated: Apr 8, 2024 2:53 PM

- URL: https://udmercy.libguides.com/nursing

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

4.10: Literature Review

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 16523

- Lapum et al.

- Ryerson University (Daphne Cockwell School of Nursing) via Ryerson University Library

What it is?

A literature review involves summarizing what is known about a particular topic based on your examination of existing scholarly sources. You may be asked to write a literature review as a stand-alone assignment or as part of a larger assignment or research project. It will provide you and your readers with a summary of what is known and the gaps and inconsistencies in the existing literature and/or research approaches used.

A literature review involves synthesizing ideas. A synthesis combines multiple ideas and text into a larger whole. When you are synthesizing multiple texts, you should organize your writing based on the content as opposed to the individual sources. Consider the similar themes across multiple sources and organize your writing according to these themes. You should identify the main ideas in the literature and compare/contrast them with purpose.

Table 4.4 describes the types of literature reviews used in nursing. Various approaches can be used to frame reviews, but all literature reviews involve synthesis skills, with the exception of annotated bibliographies.

Table 4.4: Types of literature reviews

How to do it?

The following discussion explores annotated bibliographies and narrative reviews because these are common in undergraduate nursing curricula.

Annotated Bibliography

There are many ways to complete an annotated bibliography , depending on the assignment requirements. See Figure 4.7 outlining the two components of the annotated bibliography including the citation and the annotation

Figure 4.7 : Components of an annotated bibliography

Here are some general steps to take when completing an annotated bibliography :

- Identify your topic for the bibliography and the number of texts to be included.

- If the texts are not provided for you, search the literature for articles or other types of texts that relate to your topic.

- Take notes while reading and critiquing the identified texts.

- Review your notes and then construct a short annotation summarizing each text’s main points. If a text presents the results of a research study, you also include the study purpose, methods, and conclusions.

- Depending on the outlined requirements or your instructor’s expectations, the annotation may also include brief comments critiquing each text, comparing and contrasting texts, and describing how each text adds to the overall topic of the bibliography.

- A bibliographic citation is included prior to the written annotation. The citation will vary based on what reference style is required; APA formatting is often required in nursing.

**see Chapter 3 and Chapter 9 for more information on critiquing a text for quality and APA style rules.

Narrative literature reviews

Here are some general steps for writing a narrative literature review :

- Narrow and define your topic , and then review the existing literature in that area. You may limit your literature search to certain dates (e.g., the last five years) or certain countries, or certain types of literature such as empirical, theoretical, and/or discussion. You need to decide what sources are acceptable to include, such as journal articles, books, and/or grey literature. You may also check the reference lists of the literature you have found.

- Take notes about the main points and critique the literature while doing pre-reading and during the full reading of the literature that you have located.

- Gather your notes and consider the literature you have reviewed as a whole. Think about: What are the main points across all sources reviewed? Are there common findings across sources? Do some sources contradict each other? What are the strengths and weaknesses in the literature? What are the gaps in the literature?

- Make decisions on how to structure your review . The structure is often based on content trends across the various sources; these trends can be used as sub-headings to help you categorize and organize your writing. You might also organize a literature review chronologically, particularly if “time” is an important element. Some literature reviews are organized by method, with sub-sections focusing on theoretical, qualitative, survey, and intervention studies.

- Use topic sentences in each paragraph and logically link each paragraph and section to the next.

What to keep in mind?

As you are writing literature reviews, keep in mind several points:

- Annotated bibliographies are concise and typically presented as one paragraph, ranging from 100–300 words, but expectations vary, so check the assignment guidelines or ask your instructor.

- Narrative literature reviews are much longer and vary in length based on the reason for writing it. If it is part of a larger assignment, your instructor may provide you a specific length. If it is part of an article publishing results from a study, it may serve as a background section and be fairly short (a few paragraphs). If it is part of a graduate thesis, it may form one of your chapters and may be many pages long.

Activity: Check Your Understanding

The original version of this chapter contained H5P content. You may want to remove or replace this element.

Reviews of Literature in Nursing Research: Methodological Considerations and Defining Characteristics

Affiliation.

- 1 School of Nursing, Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada (Ms Silva and Drs Woo, Galica, Wilson, and Luctkar-Flude); School of Nursing, Federal University of Santa Catarina, Santa Catarina, Brazil (Dr Padilha and Ms Petry); and Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada (Dr Silva E Silva).

- PMID: 35213877

- DOI: 10.1097/ANS.0000000000000418

Despite the availability of guidelines about the different types of review literature, the identification of the best approach is not always clear for nursing researchers. Therefore, in this article, we provide a comprehensive guide to be used by health care and nursing scholars while choosing among 4 popular types of reviews (narrative, integrative, scoping, and systematic review), including a descriptive discussion, critical analysis, and decision map tree. Although some review methodologies are more rigorous, it would be inaccurate to say that one is preferable over the others. Instead, each methodology is adequate for a certain type of investigation, nursing methodology research, and research paradigm.

Copyright © 2022 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Delivery of Health Care

- Nursing Research*

- Research Design

- Research Personnel

- Review Literature as Topic*

MSU Libraries

- Need help? Ask a Librarian

Nursing Literature and Other Types of Reviews

- Literature and Other Types of Reviews

- Starting Your Search

- Constructing Your Search

- Selecting Databases and Saving Your Search

- Levels of Evidence

- Creating a PRISMA Table

- Literature Table and Synthesis

- Other Resources

Introduction

There are many types of literature reviews, but all should follow a similar search process. Below are a few types of literature reviews, as well as definitions and examples. Much of this information can be found in the article A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.

Additional information about types of reviews, including an updated list of 48 types of reviews can be found in the article Meeting the Review Family: Exploring Review Types and Associated Information Retrieval Techniques

Literature Review : This is a generic term that can cover a wide range of subjects, and varies in completeness and comprehensiveness. They are typically narrative, and analysis may be chronological, conceptual, thematic, or however the author decides to organize the material. Anesthesia Personnel's Experiences With Digital Anesthesia Information Management Systems: A Literature Review.

Scoping Review : A preliminary assessment of the size and scope of available published literature. A scoping review is intended to identify current research and the extent of such research, and determine if a more comprehensive review is viable. Can include research in progress, and the completeness of searching is determined by time/scope. Traumatic Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Scoping Review

Mapping Review: Looks at existing literature and maps out future directions and current gaps in the research literature. Search may be determined by time/scope. Classification of Mild Stroke: A Mapping Review

Rapid Review : Assessment of what is already known about a policy or practice issue. Uses systematic review methods to search and critically evaluate existing research, but search is limited by time constraints. The Current State Of Telehealth Evidence: A Rapid Review

State-of-the-art/state-of-the-literature review: Addresses current matters as opposed to other types of reviews that address retrospective and current approaches. Comprehensive searching of the literature, and looks for current state of knowledge and sets priorities for future investigation and research. Artificial Intelligence for the Otolaryngologist: A State of the Art Review

Integrative Review: Combines empirical and theoretical research to examine research on a given area. Includes non-experimental research, and can include case studies, observational studies, theories, guidelines, etc., and is generally used to inform healthcare policy and practice. An Integrative Review of Yoga and Mindfulness-Based Approaches for Children and Adolescents with Asthma

Systematic Review: Seeks to systematically search, appraise, and synthesize research evidence. Requires exhaustive, comprehensive searching, including searching of grey literature. The efficacy of rehabilitation in people with Guillain-Barrè syndrome: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials

Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: Includes all of systematic review, but requires quantitative analysis for the meta-analysis piece. The Efficacy and Safety of Disease-Modifying Osteoarthritis Drugs for Knee and Hip Osteoarthritis—a Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis

Umbrella Review: Specifically refers to searching for reviews only-usually systematic reviews only. Should discuss what is known, unknown, and recommendations for future research. Coffee consumption and health: umbrella review of meta-analyses of multiple health outcomes

Which Type of Review Should I Do?

- Which Review Is Right For You? A great diagram and flow chart for picking the type of review that is right for you, based on scope, time, and research team.

- Which Review Is Right For You? A survey tool designed to help determine the most appropriate method for your review. It's not a prescriptive tool, but is intended to help identify options for your review.

- Next: Starting Your Search >>

- Last Updated: Mar 27, 2024 3:56 PM

- URL: https://libguides.lib.msu.edu/nursinglitreview

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 21, Issue 2

- Reviewing the literature: choosing a review design

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Helen Noble 1 ,

- Joanna Smith 2

- 1 School of Nursing and Midwifery , Queen’s University Belfast , Belfast , UK

- 2 School of Healthcare , University of Leeds , Leeds , UK

- Correspondence to Dr Helen Noble, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast BT9 7BL, UK; helen.noble{at}qub.ac.uk

https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2018-102895

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Many health professionals, students and academics including health researchers will have grappled with the challenges of undertaking a review of the literature and choosing a suitable design or framework to structure the review. For many undergraduate and master’s healthcare students their final year dissertation involves undertaking a review of the literature as a way of assessing their understanding and ability to critique and apply research findings to practice. For PhD and Master’s by Research students, a rigorous summary of research is usually expected to identify the state of knowledge and gaps in the evidence related to their topic focus and to provide justification for the empirical work they subsequently undertake. From discussions with students and colleagues, there appears to be much confusion about review designs and in particular the use and perhaps misuse of the term ‘systematic review’. For example, some quantitatively focused researchers subscribe to a ‘Cochrane’ approach as the only method to undertake a ‘systematic review’, with other researchers having a more pragmatic view, recognising the different purposes of a review and ways of applying systematic methods to undertake a review of the literature. Traditionally, systematic reviews have included only quantitative, experimental studies, usually randomised controlled trials. 1 More recently, systematic reviews of qualitative studies have emerged, 2 and integrative reviews which include both quantitative and qualitative studies. 3

In this article, we will build on a previous Research Made Simple article that outlined the key principles of undertaking a review of the literature in a structured and systemic way 4 by further exploring review designs and their key features to assist you in choosing an appropriate design. A reference to an example of each review outlined will be provided.

What is the purpose of undertaking a review of the evidence?

The purpose of a review of healthcare literature is primarily to summarise the knowledge around a specific question or topic, or to make recommendations that can support health professionals and organisations make decisions about a specific intervention or care issue. 5 In addition, reviews can highlight gaps in knowledge to guide future research. The most common approach to summarising, interpreting and making recommendations from synthesising the evidence in healthcare is a traditional systematic review of the literature to answer a specific clinical question. These reviews follow explicit, prespecified and reproducible methods in order to identify, evaluate and summarise the findings of all relevant individual studies. 6 Systematic reviews are typically associated with evaluating interventions, and therefore where appropriate, combine the results of several empirical studies to give a more reliable estimate of an intervention’s effectiveness than a single study. 6 However, over the past decade the range of approaches to reviewing the literature has expanded to reflect broader types of evidence/research designs and questions reflecting the increased complexity of healthcare. While this should be welcomed, this adds to the challenges in choosing the best review approach/design that meets the purpose of the review.

What approaches can be adopted to review the evidence?

- View inline

Key features of the common types of healthcare review

In summary, we have identified and described a variety of review designs and offered reasons for choosing a specific approach. Reviews are vital research methodology and help make sense of a body of research. They offer a succinct analysis which avoids the need for accessing individual research reports included in the review, increasingly vital for health professionals in light of the increasing vast amount of literature available. The field of reviews of the literature continues to change and while new approaches are emerging, ensuring methods are robust and remain paramount. This paper offers guidance to help direct choices when deciding on a review and provides an example of each approach.

- 5. ↵ Canadian Institutes of Health Research . Knowledge translation. Canadian Institutes of Health Research . 2008 . http://www.cihr.ca/e/29418.html ( accessed Jan 2018 ).

- 6. ↵ Centre for Reviews and Dissemination . Guidance for undertaking reviews in heathcare . 3rd ed . York University, York : CRD , 2009 .

- Buchwald H ,

- Braunwald E , et al

- Horvath M ,

- Massey K , et al

- Sheehan KJ ,

- Sobolev B ,

- Villán Villán YF , et al

- Christmals CD ,

- Whittemore R ,

- McInnes S ,

- Bonney A , et al

- Greenhalgh T ,

- Harvey G , et al

- Rycroft-Malone J ,

- McCormack B ,

- DeCorby K , et al

- Mitchison D ,

- 19. Joanna Briggs Institute Umbrella reviews . 2014 . http://joannabriggs.org/assets/docs/sumari/ReviewersManual-Methodology-JBI_Umbrella_Reviews-2014.pdf ( accessed Jan 2018 )

- van der Linde R , et al

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res

- v.18(1); Jan-Feb 2013

Nursing ethical values and definitions: A literature review

Mohsen shahriari.

Nursing and Midwifery Care Research Center, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran

Eesa Mohammadi

1 Department of Nursing, Medical Sciences Faculty, Tarbiat Modares University, Bridge Nasr (Gisha), Tehran, Iran

Abbas Abbaszadeh

2 Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Masoud Bahrami

3 Nursing and Midwifery Care Research Center, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran

Background:

Ethical values offer a framework for behavior assessment, and nursing values influence nurses’ goals, strategies, and actions. A literature review was adopted in order to determine and define ethical values for nurses.

Materials and Methods:

This literature review was conducted based on the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination guidelines. The key words used to search relevant sources were nursing, ethics, ethical values, and nursing values. The search of articles in English was carried out in Medline, CINAHL, PubMed, Scopus, Ovid, and Proquest databases. The search of articles in Persian was conducted in databases of Magiran, SID, and Irandoc publications. After assessing and analyzing the obtained data, 17 articles which had a distinct definition of ethical values were chosen and subjected to a thorough study.

The search yielded 10 nursing ethical values: Human dignity, privacy, justice, autonomy in decision making, precision and accuracy in caring, commitment, human relationship, sympathy, honesty, and individual and professional competency.

Conclusions:

This study showed that common ethical values are generally shared within the global community. However, in several areas, influences of social, cultural, and economical status and religious beliefs on values result in a different definition of these values. This study revealed that based on humanistic nature of nursing, common values in nursing protect human dignity and respect to the patients. Recognizing and definition of ethical values can help to improve nursing practice and develop codes of ethics.

I NTRODUCTION

Nurses as one of the health service providers and members in health system who are responsible for giving care to the clients and patients based on ethical issues.[ 1 ] They need ethical knowledge to conduct their appropriate function to manage situations and to give safe and proper legal and ethical care in today's changing world.[ 2 ] With regard to practical care, they always try to answer the question of “What can I do?,” whereas they should try to answer what is essential to be done for the patients in the context of ethical principles.[ 3 ] Ethics seek the best way of taking care of the patients as well as the best nursing function.[ 4 ]

Nurses are responsible for their clinical function, and their main responsibility is to take care of the clients and patients who deserve appropriate and safe care.[ 5 ] They act based on the values they have selected. These values form a framework to evaluate their activities influencing their goals, strategies, and function.[ 6 ] These values can also be counted as a resource for nurses’ conduct toward clinical ethical competency and their confrontation with contemporary ethical concerns. Values conduct human life priorities and form the world we live in. They act as one of the most basic parts of human life. Ethical values are inseparable components of the society and, as a result, nursing profession.[ 7 , 8 ]

Discovery of basic values and reaching an agreement on clinical ethical values are essential with regard to constant changes in nurses’ social class and role.[ 9 ] Nurses’ awareness of their values and the effect of these values on their behavior is a core part of humanistic nursing care.[ 10 ] They need to tailor their function to the value system and cultural beliefs of their service recipients.[ 11 ] Values originate from cultural environment, social groups, religion, lived experiences, and the past. Social, cultural, religious, political, and economic considerations influence individuals and their value system,[ 6 ] and ultimately, health, education, social strategies, and patients’ care. Numerous documents have been prepared in nursing texts and literature concerning these values and clarification of their traits.[ 7 , 9 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ]

Recognition and definition of nursing ethical values in various communities can help nurses have mutual understanding in international level. It can also bring nurses closer to reach a common meaning of care in patients with different cultures. However, there is a paucity of research particularly in the Iranian context to deeply explore nursing ethical values. Therefore, in the first step, the main aim of the study was to identify and explore nursing ethical values reflected in nursing texts. This search was then used to prepare code of ethics and clinical guidelines for Iranian nurses, along with other documents and evidences. Results of other aspects of the study have been reported in other articles from the researchers.

M ATERIALS AND M ETHODS

This study is a part of a bigger study conducted in the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. A literature review was carried out in 2010 to determine ethical values and related definitions in nursing systems of various countries.

In this literature review, the York University four-step approach was applied. These steps are as follows: Forming questions and determining search strategies, extracting synthesis, providing quality assessments and applying study evaluation tools, and suggesting methods to analyze and data synthesis.[ 17 ]

Search strategy

The study tried to answer the following questions:

- What nursing ethical values are determined and offered in this study?

- What is the definition of each value?

In this literature review, all published articles in English language from 1995 to 2010, as well as articles in Persian from 1996 to 2010 were searched by separated keywords and then keywords in combination, respectively. AND/OR was used combination and collection of various key words together. A manual search was also adopted and the references of the articles were studied as well. The search yielded about 82 articles whose titles and abstracts were studied. The articles not meeting the inclusion criteria were left out. Inclusion criteria were: Articles published in English or Persian and those articles on nursing ethical values in patients’ care. At this stage, 37 articles were excluded and 45 were selected and comprehensively reviewed. In the next stage, the articles were completely studied with regard to inclusion criteria and their answers to the questions of the present study.

Finally, 17 related articles were selected and considered for the study. Data were extracted through firstly writing down the detected values and their definitions in the related articles. Then, the research team compared the findings and recorded them in a table, and selected the best definition of each value among the suggested definitions. Finally, after comparison of the names and words, a unique definition for each value was achieved based on the trait of definition.

Research team checked all selected articles concerning assessment of quality based on criteria of study quality evaluation tool. This tool was designed by the research team with regard to the study goal. Two questions were considered with respect to the various research methods employed in the selected articles. The questions were as follows:

- Does the article express nursing ethical values?

- Does the article contain a clear and specific definition for the expressed ethical values?

In order to increase study credibility, the abstracts were studied by researchers individually and the obscure points were discussed by the research team. In case of a disagreement to include an article in the study, a third member of the research team conducted further investigations, the obscure points were discussed in the group, and a final decision was made.

In the stage of data combination, all textual obtained data from the selected articles were classified and completely described. After textual data had been extracted and studied critically, the traits were separated and finalized based on the obtained definition for each value or ethical concept and finally a unique definition was obtained. Each obtained defined value has been explained in the section “Discussion.” These defined values suggested appropriate answers to literature review questions.

Articles methodological traits

The articles were from 12 countries: Four from US, two from Canada, five from European countries (Belgium, England, Finland), and six from Asian countries (Iran, Japan, China, Thailand, and Taiwan).

Reviewed articles included two quantitative studies, eight qualitative studies, three literature reviews, two philosophical inquiries, and two action research philosophical methods. Various sampling methods had been precisely employed in these studies. 1360 subjects comprised the recruited subjects in these 17 articles. In two quantitative descriptive studies, 922 clinical nurses and nursing students had been randomly selected through census sampling. In qualitative researches, the participants comprised 438, randomly selected through purposive sampling. The number of participants ranged between 20 and 300 individuals. In most of these qualitative studies, the participants included clinical nurses accompanied by nurse educators.[ 9 , 18 , 19 , 20 ] In one study, the participants were just clinical nurses, and in another,[ 21 ] they were just nursing students.[ 22 ]

The data were mostly collected through individual interviews which were, in some cases, the only source of data and in some other cases accompanied by other methods. The data had been collected by different methods: One by individual interviews and group discussion,[ 20 ] one by individual interview and observation,[ 18 ] one by narration and individual interview,[ 19 ] one by group discussion and narration,[ 22 ] and finally, in only one by group discussion.[ 9 ] In two studies, data had been collected through literature content analysis;[ 10 , 13 ] in two, by applying intervention;[ 16 , 23 ] in two other, through literature review;[ 7 , 24 ] and finally, in two studies, the data had been collected through philosophical inquiries.[ 6 , 25 ]

In two quantitative studies adopted to collect data, standard tools had been employed. In the study of Weis (2000), Nurses’ Professional Values Scale (NPVS) with confirmed reliability and validity had been utilized.[ 26 ] Rassin (2008) used nursing code of ethics related to International Nursing Association to evaluate nurses’ professional values as well as the Rokeach Values Survey with confirmed reliability and content validity to assess nurses’ personal values.[ 15 ]

Quality appraisal

The selected articles were reviewed concerning their quality. Application of a systematic literature scientific method in the present literature review study let the research review the articles based on research questions, research project, data collection method, data analysis method, data credibility, ethical considerations, and the results.

In quantitative studies reviewed, standard questionnaires had been adopted for data collection, data analysis method had been clearly defined, and the necessary permissions had been obtained from university and other needed institutes to respect ethical considerations. The results were also in the direction of research questions.

In qualitative studies, research methodology and data analysis had been clearly stated, and participants’ consents had been obtained to respect ethical considerations. Various methods had been employed for credibility: Data collection from various methods,[ 19 , 20 , 22 ] precise transcription, and data recheck and conformability with participants and colleagues.[ 18 , 19 , 20 ]

Data analysis methods of the studies, conducted based on philosophical research methodology and action research, had not been clearly mentioned, but their results were related.

General traits of reviewed studies

General traits of reviewed studies in the context of nursing ethical values have been presented in Table 1 . The reviewed articles had investigated nurses’ ethical values from different aspects.

Outline of studies included in the review

In various studies, the values had been differently introduced and defined. Most of the reviewed articles had focused on common nursing ethical values.[ 22 ] In some, several values and in some other, only one value had been introduced and defined. Konishi (2009) had only studied the value of harmony in nursing and had suggested that as one of the most fundamental values in Japan.[ 13 ] Verpeet (2003) had defined values as nurses’ responsibility against their patients, profession, other health team members, and society.[ 10 ] Naden (2004) in his study to define components of human dignity indicated braveness, responsibility, respect, commitment, and ethical desires.[ 18 ] Wros (2004) reported a significant difference in ethical value of decision making among the nurses in two countries.[ 19 ] Trailer (2004) claims that respect to the patients has the highest priority among codes of ethics and acts as a basic value to design the nursing ethical codes which include three main elements of respect, reliability, and mutuality.[ 25 ]

Shih (2009) reported that 75% of the participants had indicated taking care of the patients and their related individuals and altruism as the most common nursing values. Other values in his study were provision of holistic professional and appropriate care, promotion of personal and professional competency, disease prevention, health promotion, promotion of interpersonal communication skills, and receiving fair reward.[ 9 ]

Weis (2000), through factor analysis, introduced eight factors for professional values of which the most important one was nurses’ role in care and dimension of commitment.[ 26 ] Pang (2009) stated nursing professional values in seven themes of altruism, care, respecting the dignity, trust, accountability, independency, and justice.[ 20 ] Mahmoodi (2008) indicated responsibility, having mental and emotional communication, value, and ethics criteria such as honesty in work, mutual respect, religious margins and confidentiality, justice and fairness.[ 21 ] Shaw (2008) and Fahrenwald (2005) in our studies, in a different way, investigated application of five nursing professional values in nursing education, including altruism, independency, respect to dignity, nursing interventions’ integrity, and social justice.[ 16 , 23 ] Horton (2007) stated that personal and organizational values have effects on nursing and introduced values such as responsibility, honesty, patients’ participation, integrity and humanity protection, patients’ independency, deep humanistic relationship, dignity, hope, passion, teamwork, differentiation, versatility, altruism, nurturing, integrity and support, reciprocal trust, sound knowledge, clinical competence, communications, unity, homogeneity, coordination, self-sacrifice and devotion, self-protection, privacy preservation, creativity, aesthetics, management, economizing, braveness, commitment, ethical attitude, personal orientation, judgment, freedom, individualism, acknowledgment, and personal success.[ 7 ] Two studies had stated detection of ethical values as the basis for collection of codes of ethics.[ 24 , 27 ]

D ISCUSSION

In all of the articles studied in the present literature review, patients’ dignity and respect had been stated as the most frequent value indicated in 12 articles, equality and justice in 8 articles, and altruism and precise care and making appropriate relationships were indicated in 6 articles, respectively.

Comparison and finalization of the obtained data concerning nursing ethical values in patients’ care yielded 10 values mostly indicated in the articles: Human dignity, altruism, social justice, autonomy in decision making, precision and accuracy in caring, responsibility, human relationship, individual and professional competency, sympathy, and trust. The 10 obtained values in this literature review and their definitional traits are presented subsequently.

Human dignity

Respecting human dignity was the most common value indicated in the reviewed articles. Respect to individuals including the persons, their families, and the society has been mentioned as an important nursing ethical value. Dignity respect has been defined with definitional traits as consideration of human innate values, respecting patient's beliefs and preservation of their dignity and privacy during clinical procedures, and communication with the patients, and contains understanding the patients and devoting to fulfill clients’ needs.[ 15 , 16 , 18 , 20 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 27 ] Pang (2009) argues that nurses should accept that people deserve respect and dignity in action. They should practically cover patients’ body parts if exposed and keep patients’ secrets confidential.[ 20 ]

This value has been suggested in most of the articles possibly as a result of humanistic nature of nursing profession in helping others. This value had been emphasized in all articles of Asian countries, reflecting cultural similarities in these countries. This value has also been indicated in most of the codes of ethics in various countries all over the world.

Social justice

Justice is an ethical value suggested in nursing literatures. Social justice has been defined by the traits which, in addition to consideration of individuals’ dignity and respect, focus on equal access to health services and the right of being fairly treated and cared free of economic, social, and cultural status.[ 9 , 10 , 15 , 16 , 20 , 21 , 23 ] Social justice had been the indication in most of the countries and had been defined as fair distribution of resources and provision of individuals’ equal treatment and care.

Verpeet (2003) stated that equality means access of all individuals to health services. She claims every individual in Belgium is supposed to have equal right of receiving equal nursing care.[ 10 ]

Altruism is a common nursing value in various countries. It has been defined with traits of consideration of human as the axis of attention and focus in nursing, helping others and provision of the utmost health and welfare for the clients, their families, and the society, selflessness, and self-devotion.[ 6 , 9 , 13 , 15 , 16 , 18 , 22 , 23 , 27 ] Therefore, altruism is defined as focusing on clients as a human and struggling to preserve their health and well-being. Pang (2009) debated that based on the principle of altruism, nurses should have spirit of selflessness and helpfulness toward others.[ 20 ]

Autonomy in decision making

Independency in decision making is a value suggested in some studies as a nursing ethical value. Nurses have defined its traits as having right of independency in decision making, right to accept or reject suggested treatments, interventions, or care. In addition, autonomy in decision making necessitates giving appropriate and adequate information to the clients and, if necessary, to their families.[ 13 , 15 , 23 ] So, autonomy in decision making occurs when nurses let patients be informed, free, and independent to decide on the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention through giving them appropriate information.

Konishi (2009) debates that conscious adult patients should themselves decide. With regard to nursing profession, nurses should provide the patients with information, explain suggested interventions, and let them free to either accept or reject oncoming procedures so that they and their families can make a decision about their condition.[ 13 ]

Precision and accuracy in caring

Precise and accurate care has been indicated as a nursing ethical value. Based on this definition, this sort of care is a precise, safe, appropriate, multidimensional, and kind care given to the patients by nurses. This is also thoughtful, based on adequate clinical skills and nursing knowledge to fulfill clients’ needs, promote their health, and relieve their pain and suffering. It is also based on standards and results in patients’ safety and satisfaction.[ 6 , 9 , 15 , 23 , 24 , 27 ] In this regard, Shih (2009) states that holistic and appropriate professional care is to prevent diseases, promote health, and make the feeling of comfort and safety for the patients.[ 9 ]

Responsibility

Responsibility has been defined as a nursing ethical value. It is defined with traits of commitment, feeling responsible for the duties toward patients, and respecting the patients’ rights for decision making.[ 15 , 18 , 19 , 21 , 24 , 26 , 28 ] Based on this definition, nurses are responsible for giving evidence-based care, best clinical function, and applicable and valid research, and are accountable for their actions and duties. Verpeet (2005) argues that nurses are responsible for promotion of patients’ well-being, having a holistic approach toward them and completing their duties.[ 28 ]

Human relationship

Human relationship has been indicated as a nursing ethical value with traits of mutual respect, trust, and reliance which are accompanied by patients’ confidentiality and privacy. It can be verbal or non-verbal and defined through having honesty in words and practice, sympathy and mutual understanding, courtesy, and friendliness.[ 9 , 15 , 19 , 21 , 25 ]

In this regard, giving care is possible only through making humanistic, efficient, and effective relationship, a relationship based on mutual respect and understanding.

Individual and professional competency

Individual and professional competency as a nursing ethical value has been defined with traits of struggling to make nursing as a profession, feeling the need to acquire personal and professional competency so that nurses can grow and develop in the direction of advances and new technology. Personal competency and development of the nurses result in acquiring up-to-date knowledge and promotion of clinical skills and practical abilities, and the ability to give more holistic and comprehensive care. Promotion of personal and professional competency comes true when nurses make a background for the best patients’ care by trying to give evidence-based care, and their empowerment for participation in activities in relation with other health team members and interpersonal and inter-professional skills development.[ 7 , 9 , 15 , 20 , 24 ] Pang (2009) debates that participation in continuing professional development suggests that individuals should preserve their competency in their activities and participate in professional continuing education programs throughout their occupational life.[ 20 ]

Sympathy has been indicated as a nursing ethical value with traits of understanding patients’ and their families’ needs and giving care based on making a fair communication.[ 6 , 19 ] In some cultures, such as Japanese, nurses share patients’ physical and mental pains and sufferings.[ 19 ]

Trust has been indicated as a nursing ethical value and is defined by traits of honesty in words and practice. Nurses should gain patients’, their families,’ and society's trust through understanding patients’ situation and status and appropriate conformation with them.[ 15 , 20 , 23 , 24 ] Based on this definition, gaining clients’ trust and reliance comes true when nurses are honest in their words and practice, and gain individuals’ trust and reliance by doing their duties appropriately.

C ONCLUSION

This study showed that nursing ethical values in patients’ and clients’ care are similar in many cases due to a common core in humanistic and spiritual approach of nursing profession, which is taking care of a human. Values such as human dignity, kindness and sympathy, altruism, responsibility and commitment, justice and honesty, and personal and professional competency were similar in most of the cultures.

Despite the similarities in ethical and professional values among various countries, it is essential to detect and highlight these values in each country, for example, in Iran, with regard to the prevalent social, cultural, economic, and religious conditions. Detection and declaration of nursing ethical values in each country can be a valuable, scientific, valid, and essential document to design nursing codes of ethics. This search was used to prepare proposed code of ethics and clinical guidelines for Iranian nurses. Findings of this study search must be considered within its limitation. An attempt was made to conduct a search as vast as possible. However, it might be possible that we could not access to all articles available in the period of the search.

A CKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would also like to acknowledge the Nursing and Midwifery Care Research Center, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, for supporting this work.

Source of Support: Nursing and Midwifery Care Research Center, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences

Conflict of Interest: None

R EFERENCES

- Open access

- Published: 17 November 2023

Reversing frailty in older adults: a scoping review

- Aurélie Tonjock Kolle 1 ,

- Krystina B. Lewis 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Michelle Lalonde 1 , 4 &

- Chantal Backman 1 , 2 , 5

BMC Geriatrics volume 23 , Article number: 751 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

2366 Accesses

1 Citations

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

Individuals 65 years or older are presumably more susceptible to becoming frail, which increases their risk of multiple adverse health outcomes. Reversing frailty has received recent attention; however, little is understood about what it means and how to achieve it. Thus, the purpose of this scoping review is to synthesize the evidence regarding the impact of frail-related interventions on older adults living with frailty, identify what interventions resulted in frailty reversal and clarify the concept of reverse frailty.

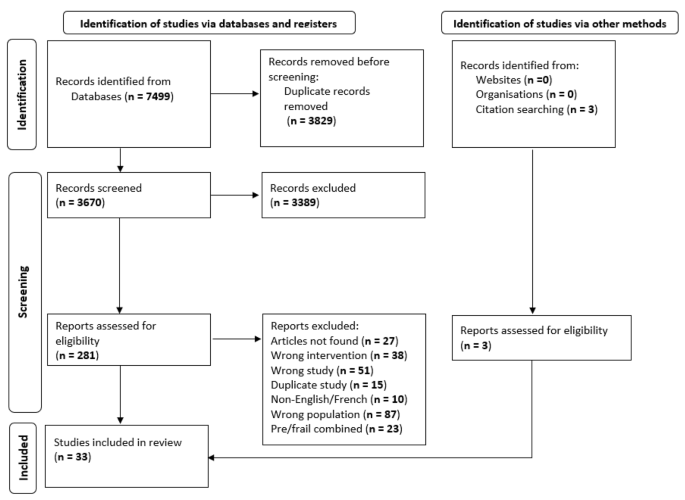

We followed Arksey and O’Malley’s five-stage scoping review approach and conducted searches in CINAHL, EMBASE, PubMed, and Web of Science. We hand-searched the reference list of included studies and conducted a grey literature search. Two independent reviewers completed the title, abstract screenings, and full-text review using the eligibility criteria, and independently extracted approximately 10% of the studies. We critically appraised studies using Joanna Briggs critical appraisal checklist/tool, and we used a descriptive and narrative method to synthesize and analyze data.

Of 7499 articles, thirty met the criteria and three studies were identified in the references of included studies. Seventeen studies (56.7%) framed frailty as a reversible condition, with 11 studies (36.7%) selecting it as their primary outcome. Reversing frailty varied from either frail to pre-frail, frail to non-frail, and severe to mild frailty. We identified different types of single and multi-component interventions each targeting various domains of frailty. The physical domain was most frequently targeted (n = 32, 97%). Interventions also varied in their frequencies of delivery, intensities, and durations, and targeted participants from different settings, most commonly from community dwellings (n = 23; 69.7%).

Some studies indicated that it is possible to reverse frailty. However, this depended on how the researchers assessed or measured frailty. The current understanding of reverse frailty is a shift from a frail or severely frail state to at least a pre-frail or mildly frail state. To gain further insight into reversing frailty, we recommend a concept analysis. Furthermore, we recommend more primary studies considering the participant’s lived experiences to guide intervention delivery.

Peer Review reports

Within the next few decades, the population of people aged 65 and over will continue to rise more than all other age groups, with roughly one in six people over 65 by 2050, compared to one in eleven in 2019 [ 1 ]. Individuals over 65 years are presumably at greater risk of becoming frail [ 2 , 3 , 4 ]. Theoretically, frailty is considered a clinically recognized state of vulnerability that results from an age-related decline in reserve and function, compromising an individual’s ability to cope with the daily challenges of life [ 5 , 6 ]. The Frailty Phenotype (FP), which is the most dominant conceptual model in literature [ 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ], considers an individual frail by the presence of at least three of five phenotypes: weakness, low levels of physical activity, unintentional weight loss, slow walking speed, and exhaustion. Physical, cognitive, psychological, and social impairments often characterize the different domains of frailty [ 11 ]. The physical domain is devoted to FP-related conditions [ 12 ], the cognitive domain is the co-existence of physical deficits and mild cognitive impairments [ 13 ], the psychological domain focuses on an individual’s coping mechanisms based on their own experiences [ 14 ], and the social domain looks at a person’s limited participation in social activities and limitations in social support [ 15 ]. Frail older adults are prone to adverse outcomes such as frequent falls, hospitalizations, disabilities, loneliness, cognitive decline, depression, poor quality of life, and even death [ 16 , 17 , 18 ]. In response, researchers have proposed various interventions to prevent or slow frailty progression by either targeting a single domain (e.g., physical, social, cognitive, etc.) using single component interventions or targeting two or more domains using multi-component interventions.

For example, Hergott and colleagues investigated the effects of a single-component intervention, functional exercise, on acromegaly-induced frailty [ 19 ]. Abizanda and colleagues examined the effects of a multi-component intervention, composed of nutrition and physical activity, on frail older people’s physical function and quality of life [ 20 ]. Some studies indicate that certain single or multi-component interventions can either reduce frailty, slow its progression, and possibly reverse it [ 3 , 21 , 22 ]. The current understanding of reverse frailty lacks clarity, and the characteristics of interventions related to frailty reversal have not yet been examined in a systematic manner.

Authors have determined the reversal of frailty using various measures. For instance, Kim and colleagues’ study evaluating an intervention composed of exercise and nutritional supplementation in frail elderly community-dwellers demonstrated reversals in FP components [ 23 ]. Components included fatigue, low physical activity, and slow walking, an improvement from the presence of 5 components of frailty (according to the FP) to 2, considered a pre-frail state [ 23 ]. Conversely, De Souto and colleagues demonstrated frailty reversal based on changes in frailty index (FI) scores, a measure of accumulation of deficits [ 24 ]. A FI score of 0.22 or greater indicates frailty, score less than or equal to 0.10 indicates a non-frail state [ 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 ]. Hergott et al. (2020) used frailty severity to indicate frailty reversal. Participants in their study reversed frailty from a severe state to a mild state [ 19 ]. These studies demonstrate the variability in how reversing frailty is measured and understood. For a more comprehensive understanding of reverse frailty and the characteristics of interventions associated with it, a comprehensive review of the literature on this topic is needed. Therefore, through a scoping review, the aim of this study is to provide an overview and synthesis of interventions that have been implemented for frail older adults, to determine whether some interventions have had an impact on reversing frailty.