Smart. Open. Grounded. Inventive. Read our Ideas Made to Matter.

Which program is right for you?

Through intellectual rigor and experiential learning, this full-time, two-year MBA program develops leaders who make a difference in the world.

A rigorous, hands-on program that prepares adaptive problem solvers for premier finance careers.

A 12-month program focused on applying the tools of modern data science, optimization and machine learning to solve real-world business problems.

Earn your MBA and SM in engineering with this transformative two-year program.

Combine an international MBA with a deep dive into management science. A special opportunity for partner and affiliate schools only.

A doctoral program that produces outstanding scholars who are leading in their fields of research.

Bring a business perspective to your technical and quantitative expertise with a bachelor’s degree in management, business analytics, or finance.

A joint program for mid-career professionals that integrates engineering and systems thinking. Earn your master’s degree in engineering and management.

An interdisciplinary program that combines engineering, management, and design, leading to a master’s degree in engineering and management.

Executive Programs

A full-time MBA program for mid-career leaders eager to dedicate one year of discovery for a lifetime of impact.

This 20-month MBA program equips experienced executives to enhance their impact on their organizations and the world.

Non-degree programs for senior executives and high-potential managers.

A non-degree, customizable program for mid-career professionals.

How AI helps acquired businesses grow

Leading the AI-driven organization

New AI insights from MIT Sloan Management Review

Credit: Mimi Phan

Ideas Made to Matter

Design thinking, explained

Rebecca Linke

Sep 14, 2017

What is design thinking?

Design thinking is an innovative problem-solving process rooted in a set of skills.The approach has been around for decades, but it only started gaining traction outside of the design community after the 2008 Harvard Business Review article [subscription required] titled “Design Thinking” by Tim Brown, CEO and president of design company IDEO.

Since then, the design thinking process has been applied to developing new products and services, and to a whole range of problems, from creating a business model for selling solar panels in Africa to the operation of Airbnb .

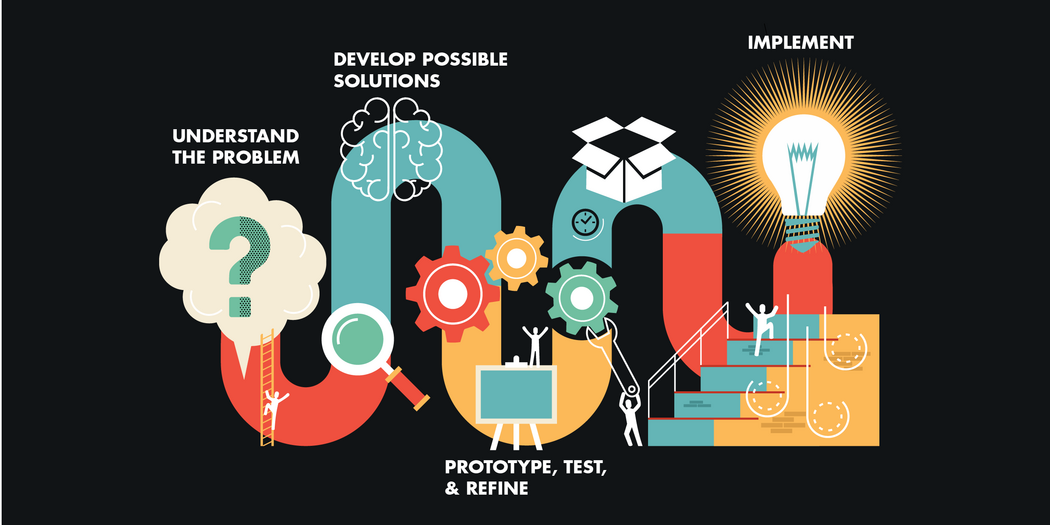

At a high level, the steps involved in the design thinking process are simple: first, fully understand the problem; second, explore a wide range of possible solutions; third, iterate extensively through prototyping and testing; and finally, implement through the customary deployment mechanisms.

The skills associated with these steps help people apply creativity to effectively solve real-world problems better than they otherwise would. They can be readily learned, but take effort. For instance, when trying to understand a problem, setting aside your own preconceptions is vital, but it’s hard.

Creative brainstorming is necessary for developing possible solutions, but many people don’t do it particularly well. And throughout the process it is critical to engage in modeling, analysis, prototyping, and testing, and to really learn from these many iterations.

Once you master the skills central to the design thinking approach, they can be applied to solve problems in daily life and any industry.

Here’s what you need to know to get started.

Understand the problem

The first step in design thinking is to understand the problem you are trying to solve before searching for solutions. Sometimes, the problem you need to address is not the one you originally set out to tackle.

“Most people don’t make much of an effort to explore the problem space before exploring the solution space,” said MIT Sloan professor Steve Eppinger. The mistake they make is to try and empathize, connecting the stated problem only to their own experiences. This falsely leads to the belief that you completely understand the situation. But the actual problem is always broader, more nuanced, or different than people originally assume.

Take the example of a meal delivery service in Holstebro, Denmark. When a team first began looking at the problem of poor nutrition and malnourishment among the elderly in the city, many of whom received meals from the service, it thought that simply updating the menu options would be a sufficient solution. But after closer observation, the team realized the scope of the problem was much larger , and that they would need to redesign the entire experience, not only for those receiving the meals, but for those preparing the meals as well. While the company changed almost everything about itself, including rebranding as The Good Kitchen, the most important change the company made when rethinking its business model was shifting how employees viewed themselves and their work. That, in turn, helped them create better meals (which were also drastically changed), yielding happier, better nourished customers.

Involve users

Imagine you are designing a new walker for rehabilitation patients and the elderly, but you have never used one. Could you fully understand what customers need? Certainly not, if you haven’t extensively observed and spoken with real customers. There is a reason that design thinking is often referred to as human-centered design.

“You have to immerse yourself in the problem,” Eppinger said.

How do you start to understand how to build a better walker? When a team from MIT’s Integrated Design and Management program together with the design firm Altitude took on that task, they met with walker users to interview them, observe them, and understand their experiences.

“We center the design process on human beings by understanding their needs at the beginning, and then include them throughout the development and testing process,” Eppinger said.

Central to the design thinking process is prototyping and testing (more on that later) which allows designers to try, to fail, and to learn what works. Testing also involves customers, and that continued involvement provides essential user feedback on potential designs and use cases. If the MIT-Altitude team studying walkers had ended user involvement after its initial interviews, it would likely have ended up with a walker that didn’t work very well for customers.

It is also important to interview and understand other stakeholders, like people selling the product, or those who are supporting the users throughout the product life cycle.

The second phase of design thinking is developing solutions to the problem (which you now fully understand). This begins with what most people know as brainstorming.

Hold nothing back during brainstorming sessions — except criticism. Infeasible ideas can generate useful solutions, but you’d never get there if you shoot down every impractical idea from the start.

“One of the key principles of brainstorming is to suspend judgment,” Eppinger said. “When we're exploring the solution space, we first broaden the search and generate lots of possibilities, including the wild and crazy ideas. Of course, the only way we're going to build on the wild and crazy ideas is if we consider them in the first place.”

That doesn’t mean you never judge the ideas, Eppinger said. That part comes later, in downselection. “But if we want 100 ideas to choose from, we can’t be very critical.”

In the case of The Good Kitchen, the kitchen employees were given new uniforms. Why? Uniforms don’t directly affect the competence of the cooks or the taste of the food.

But during interviews conducted with kitchen employees, designers realized that morale was low, in part because employees were bored preparing the same dishes over and over again, in part because they felt that others had a poor perception of them. The new, chef-style uniforms gave the cooks a greater sense of pride. It was only part of the solution, but if the idea had been rejected outright, or perhaps not even suggested, the company would have missed an important aspect of the solution.

Prototype and test. Repeat.

You’ve defined the problem. You’ve spoken to customers. You’ve brainstormed, come up with all sorts of ideas, and worked with your team to boil those ideas down to the ones you think may actually solve the problem you’ve defined.

“We don’t develop a good solution just by thinking about a list of ideas, bullet points and rough sketches,” Eppinger said. “We explore potential solutions through modeling and prototyping. We design, we build, we test, and repeat — this design iteration process is absolutely critical to effective design thinking.”

Repeating this loop of prototyping, testing, and gathering user feedback is crucial for making sure the design is right — that is, it works for customers, you can build it, and you can support it.

“After several iterations, we might get something that works, we validate it with real customers, and we often find that what we thought was a great solution is actually only just OK. But then we can make it a lot better through even just a few more iterations,” Eppinger said.

Implementation

The goal of all the steps that come before this is to have the best possible solution before you move into implementing the design. Your team will spend most of its time, its money, and its energy on this stage.

“Implementation involves detailed design, training, tooling, and ramping up. It is a huge amount of effort, so get it right before you expend that effort,” said Eppinger.

Design thinking isn’t just for “things.” If you are only applying the approach to physical products, you aren’t getting the most out of it. Design thinking can be applied to any problem that needs a creative solution. When Eppinger ran into a primary school educator who told him design thinking was big in his school, Eppinger thought he meant that they were teaching students the tenets of design thinking.

“It turns out they meant they were using design thinking in running their operations and improving the school programs. It’s being applied everywhere these days,” Eppinger said.

In another example from the education field, Peruvian entrepreneur Carlos Rodriguez-Pastor hired design consulting firm IDEO to redesign every aspect of the learning experience in a network of schools in Peru. The ultimate goal? To elevate Peru’s middle class.

As you’d expect, many large corporations have also adopted design thinking. IBM has adopted it at a company-wide level, training many of its nearly 400,000 employees in design thinking principles .

What can design thinking do for your business?

The impact of all the buzz around design thinking today is that people are realizing that “anybody who has a challenge that needs creative problem solving could benefit from this approach,” Eppinger said. That means that managers can use it, not only to design a new product or service, “but anytime they’ve got a challenge, a problem to solve.”

Applying design thinking techniques to business problems can help executives across industries rethink their product offerings, grow their markets, offer greater value to customers, or innovate and stay relevant. “I don’t know industries that can’t use design thinking,” said Eppinger.

Ready to go deeper?

Read “ The Designful Company ” by Marty Neumeier, a book that focuses on how businesses can benefit from design thinking, and “ Product Design and Development ,” co-authored by Eppinger, to better understand the detailed methods.

Register for an MIT Sloan Executive Education course:

Systematic Innovation of Products, Processes, and Services , a five-day course taught by Eppinger and other MIT professors.

- Leadership by Design: Innovation Process and Culture , a two-day course taught by MIT Integrated Design and Management director Matthew Kressy.

- Managing Complex Technical Projects , a two-day course taught by Eppinger.

- Apply for M astering Design Thinking , a 3-month online certificate course taught by Eppinger and MIT Sloan senior lecturers Renée Richardson Gosline and David Robertson.

Steve Eppinger is a professor of management science and innovation at MIT Sloan. He holds the General Motors Leaders for Global Operations Chair and has a PhD from MIT in engineering. He is the faculty co-director of MIT's System Design and Management program and Integrated Design and Management program, both master’s degrees joint between the MIT Sloan and Engineering schools. His research focuses on product development and technical project management, and has been applied to improving complex engineering processes in many industries.

Read next: 10 agile ideas worth sharing

Related Articles

Solve Any Product Problem With the Design Thinking Framework

Design is about solving problems. As such, product teams are constantly looking for a process that allows them to solve problems quickly and effectively, and design thinking is one of the most popular approaches to do just that. As the name suggests, design thinking is a process that allows product teams to solve problems through design.

The Design Thinking Framework

Prototyping.

More From Nick Babich 16 Rules of Effective UX Writing

Design thinking is a five-step process that allows a product team to go from initial idea to implementation and validation. The approach was originally proposed by Herbert A. Simon in his book The Sciences of the Artificial and later popularized by the Hasso Plattner Institute of Design at Stanford and design agencies like IDEO .

The product team clearly defines the problem they need to solve. Typically, the definition step includes all relevant information about the problem, who experienced it and why it’s important, which involves articulating the solution’s value both to users and the business.

2. Research

The product team collects and analyses as much data as it can to better understand the problem it wants to solve and the needs of users and businesses.

3. Ideation

The product team proposes possible solutions based on the information it collected in the previous stage. At the end of this step, the team selects the best solution for prototyping.

4. Prototyping

A prototype is a functioning model of the best solution. During this stage, the product team makes the solution tangible so other people can interact with it.

5. Testing

The target audience tests the prototype to ensure that it effectively solves the original problem.

Principles of Design Thinking

Design thinking is more than just a process a team follows; it's a philosophy with a set of guiding principles. The essential principles are as follows:

3 Principles of Design Thinking

- A human-centric approach.

- There are no bad ideas.

- Product design is iterative in nature.

1. A Human-first way of thinking

Design thinking is about finding the best possible solution for the people who will use your product. This principle makes the testing phase crucial for design thinking because it helps the team validate the solution with the target audience.

2. There are no bad ideas

During the ideation phase, team members are invited to propose as many ideas as possible. No one should be afraid that theirs will be considered bad. Later on, the team will narrow them down to the best output.

3. Product design is iterative in nature

The more teams learn about user needs, the better solution they can create. Design thinking is a cyclical process. At the end of the testing phase, the team can return to the definition phase with new insights about user behavior and, thus, create a better solution.

Applying Design Thinking to Product Design

Let’s look at how a design thinking process can be used to design an app that will help users learn a new language.

The better you define a problem, the more focussed your design activities will be. Try to be explicit about what you want to build and why. For example, you provide plenty of detail about each part of the product: “ We want to build an app that will be focussed on beginners and intermediate students. The app will require 30 minutes of daily interaction at any part of the day, and a large part of the interaction will be typing. We will make money by showing advertisements to our users. ”

Notice that the definition includes information on how we will monetize our product. If we don't think about revenue right from the beginning, we minimize the chances of building a commercially successful product.

Learn as much as you can about your target audience and your market. Create a user persona (the archetype of your ideal user) , and conduct a series of interviews with people who represent your user target audience to learn more about their personal goals and lifestyles. Try to understand if the product can fit naturally into their daily routine. In our example, we want to figure out when users have a half-hour of free time to use the app so that we can tailor our reminders.

Don ’ t forget about your competitors. You also need to conduct market research to learn more about the business model of your direct and indirect competitors. What other language or educational apps are available? How else are people learning languages?

Once you have a lot of insights about your target audience, conduct a brainstorming session where you discuss possible solutions for your future product. Every team member must be able to participate in the discussion. When people from different domains participate in product design, you have a unique chance to gather different perspectives on the problems at hand. For instance, someone from marketing might have a great idea about how to differentiate our new product from existing language learning apps.

Expressing your ideas in plain words can be hard. That's why, during ideation, visualizing your ideas is essential. Invite team members to sketch schematic designs . The sketches can visualize the business logic of your application or individual design decisions (such as the design of the app's screens).

At the end of the brainstorming session, you need to collect all ideas and ask all team members to vote for the best idea. This voting part can be followed up with a quick discussion of what every member thinks about the selected solution.

Prototyping is not about building a final product; it ’ s about investing the least possible amount of time and energy into making a solution tangible. You need to follow the “fail fast” strategy, meaning that you should be able to quickly validate your hypothesis and adjust your product design decisions based on that failure. Thus, if you are only at the first iteration of the design thinking cycle, you can create a paper prototype or low-fidelity digital prototype that you will later validate with your test participants. We would roll out our prototype to a select group of trial users and see how well it helps them to learn a new language.

By testing a prototype with people who represent the target audience, the product team comes to understand whether their design hypothesis is valid. Testing also helps identify areas where products can perform better. So, based on our testing, we may decide to reduce the amount of typing involved in the product interaction and make it more voice-based.

Testing should not be expensive or time-consuming. During the first iteration of the design thinking cycle, the product team can use low-fidelity prototypes and ask test participants to perform the most common operations. For example, when it comes to learning a new language, the prototype test may just involve completing a daily lesson using your prototype.

Hiring test participants that match your criteria might not be easy. Fortunately, you don ’ t need a lot of participants to validate your concept. NNGroup suggests that five test participants can find 85 percent of usability problems .

Designing the Future A Beginner’s Guide To User Journey Mapping

Master Design Thinking to Build Great Products

Design thinking is a process that helps product teams better understand the problem space and people who will use your product. When a team has a clear understanding of what problem it solves, and for whom, it can create a much better solution. At the same time, design thinking minimizes the pressure that team members have when they build a product since product design is created in iterations.

RingCentral

Built In’s expert contributor network publishes thoughtful, solutions-oriented stories written by innovative tech professionals. It is the tech industry’s definitive destination for sharing compelling, first-person accounts of problem-solving on the road to innovation.

Great Companies Need Great People. That's Where We Come In.

How to solve problems with design thinking

May 18, 2023 Is it time to throw out the standard playbook when it comes to problem solving? Uniquely challenging times call for unique approaches, write Michael Birshan , Ben Sheppard , and coauthors in a recent article , and design thinking offers a much-needed fresh perspective for leaders navigating volatility. Design thinking is a systemic, intuitive, customer-focused problem-solving approach that can create significant value and boost organizational resilience. The proof is in the pudding: From 2013 to 2018, companies that embraced the business value of design had TSR that were 56 percentage points higher than that of their industry peers. Check out these insights to understand how to use design thinking to unleash the power of creativity in strategy and problem solving.

Designing out of difficult times

What is design thinking?

The power of design thinking

Leading by design

Author Talks: Don Norman designs a better world

Are you asking enough from your design leaders?

Tapping into the business value of design

Redesigning the design department

Author Talks: Design your future

A design-led approach to embracing an ecosystem strategy

More than a feeling: Ten design practices to deliver business value

MORE FROM MCKINSEY

How design helps incumbents build new businesses

- Reviews / Why join our community?

- For companies

- Frequently asked questions

What is Design Thinking and Why Is It So Popular?

Design Thinking is not an exclusive property of designers—all great innovators in literature, art, music, science, engineering, and business have practiced it. So, why call it Design Thinking? What’s special about Design Thinking is that designers’ work processes can help us systematically extract, teach, learn and apply these human-centered techniques to solve problems in a creative and innovative way—in our designs, in our businesses, in our countries, in our lives.

Some of the world’s leading brands, such as Apple, Google and Samsung, rapidly adopted the design thinking approach, and leading universities around the world teach the related methodology—including Stanford, Harvard, Imperial College London and the Srishti Institute in India. Before you incorporate design thinking into your own workflows, you need to know what it is and why it’s so popular. Here, we’ll cut to the chase and tell you what design thinking is all about and why it’s so in demand.

What is Design Thinking?

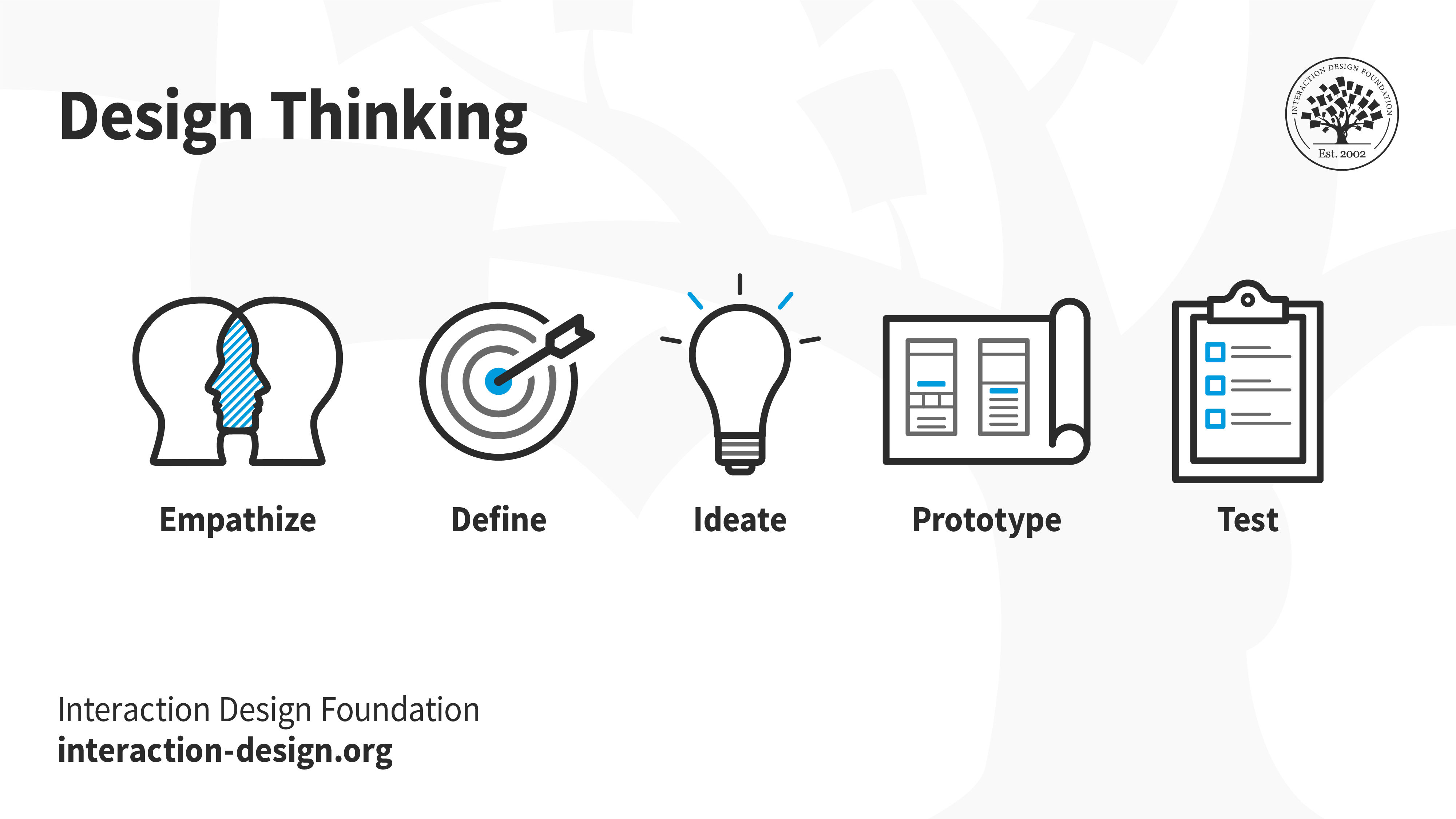

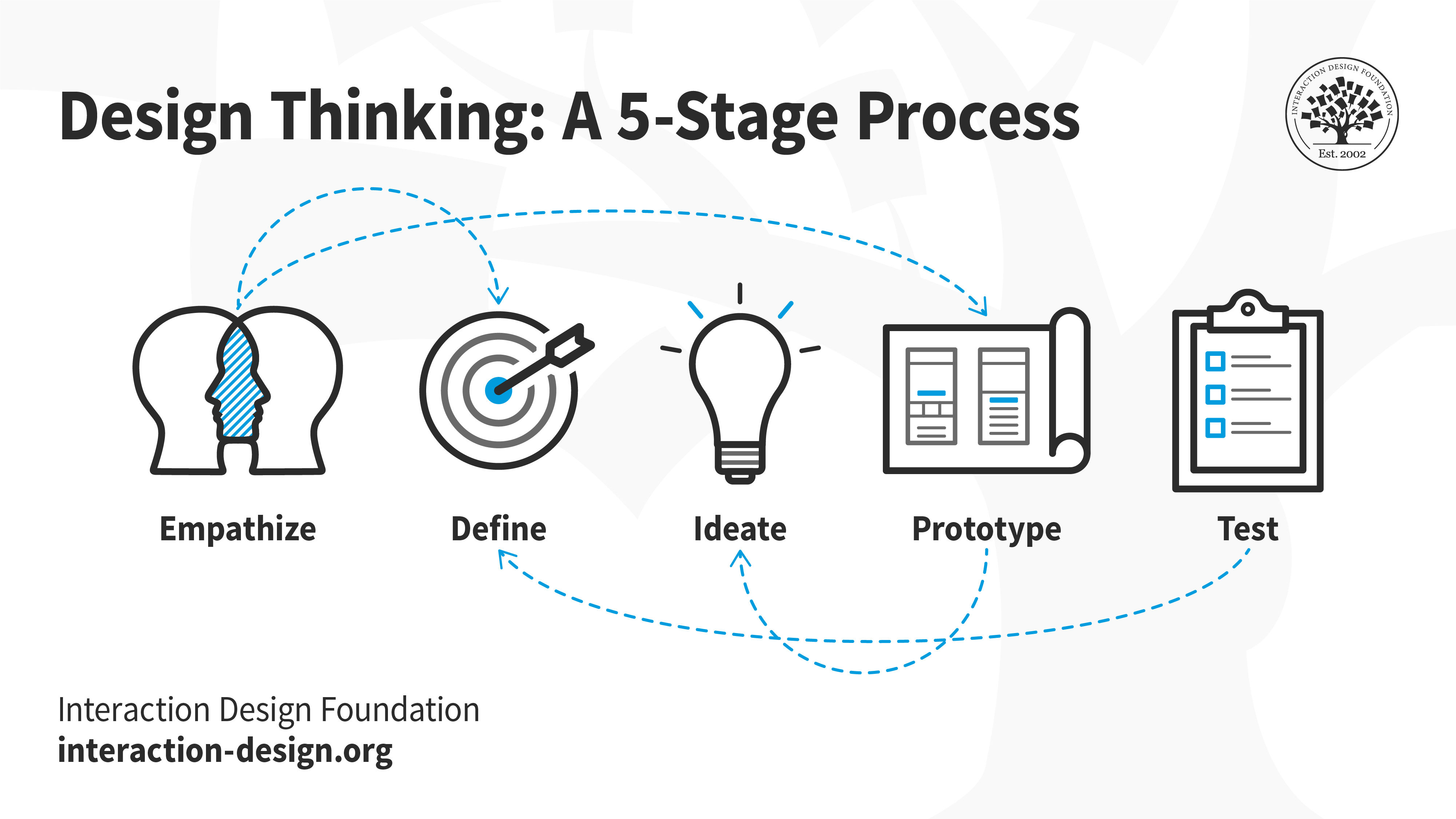

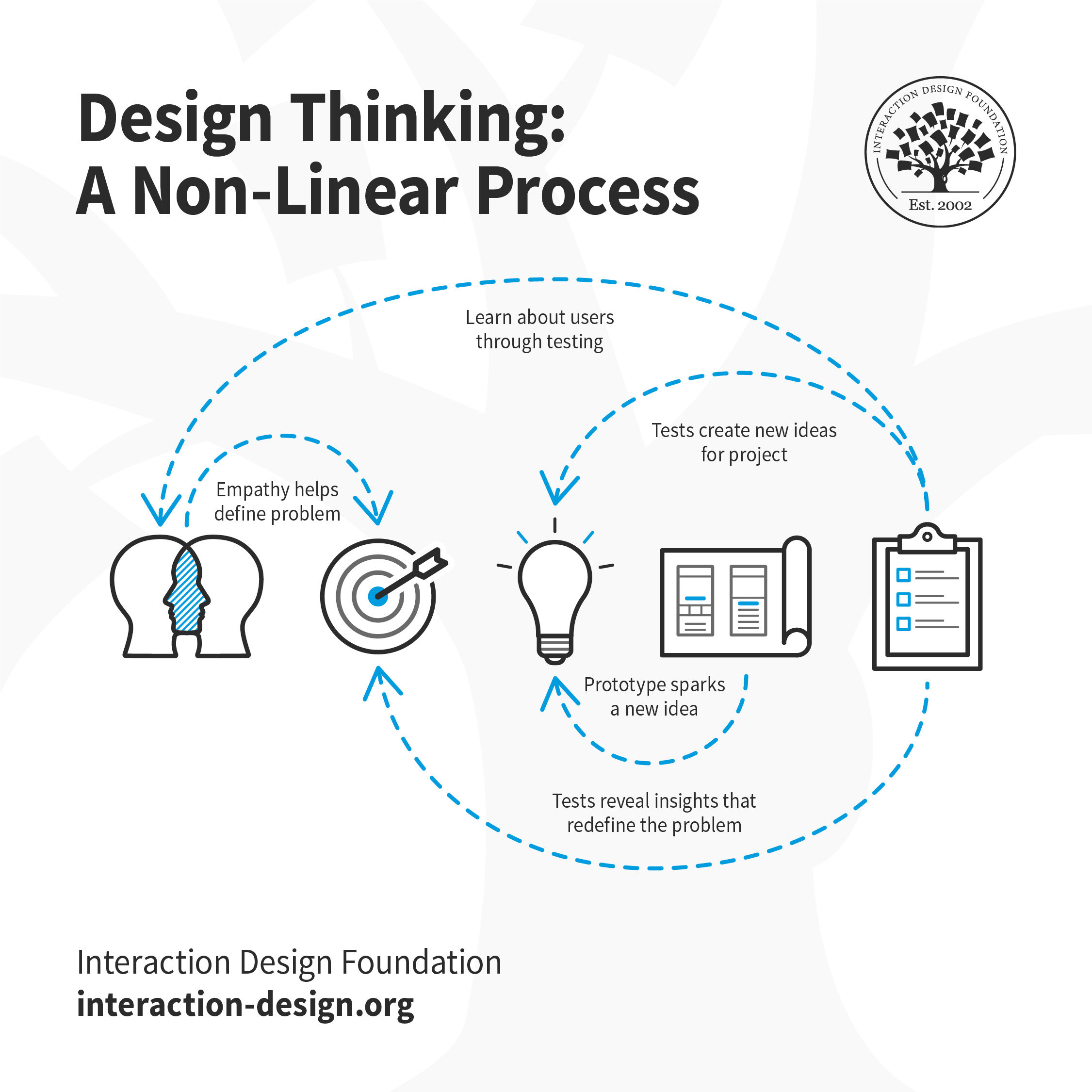

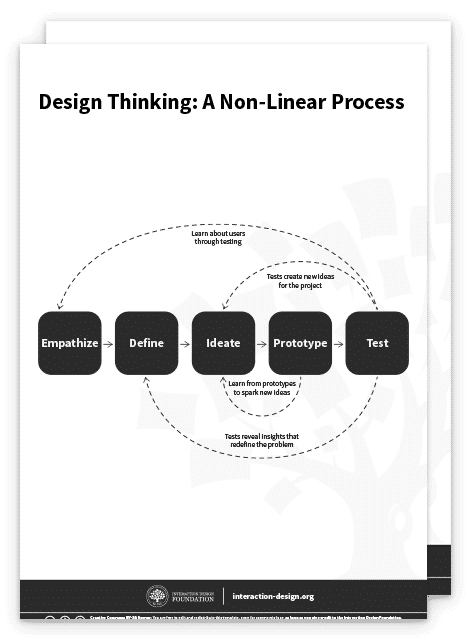

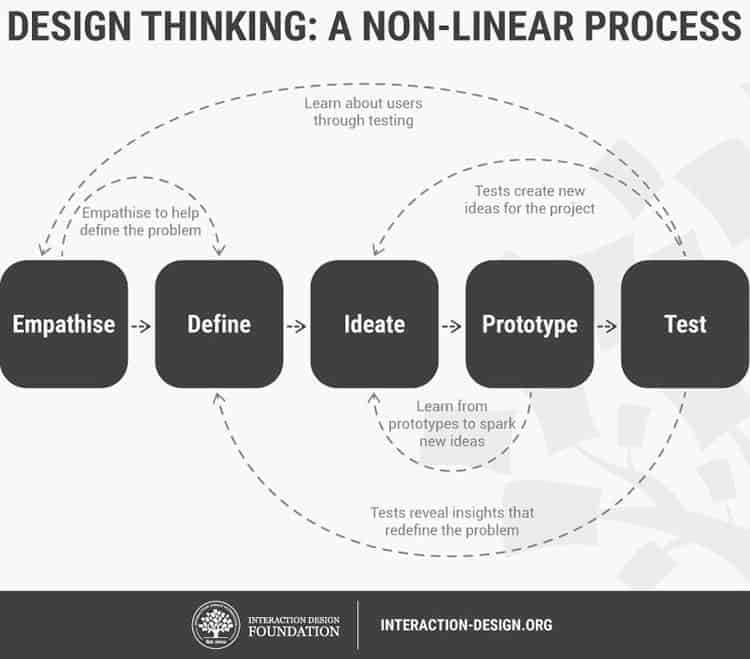

Design thinking is an iterative and non-linear process that contains five phases: 1. Empathize , 2. Define, 3. Ideate, 4. Prototype and 5. Test.

Design thinking is an iterative process in which you seek to understand your users, challenge assumptions , redefine problems and create innovative solutions which you can prototype and test. The overall goal is to identify alternative strategies and solutions that are not instantly apparent with your initial level of understanding.

Design thinking is more than just a process; it opens up an entirely new way to think, and it offers a collection of hands-on methods to help you apply this new mindset.

In essence, design thinking:

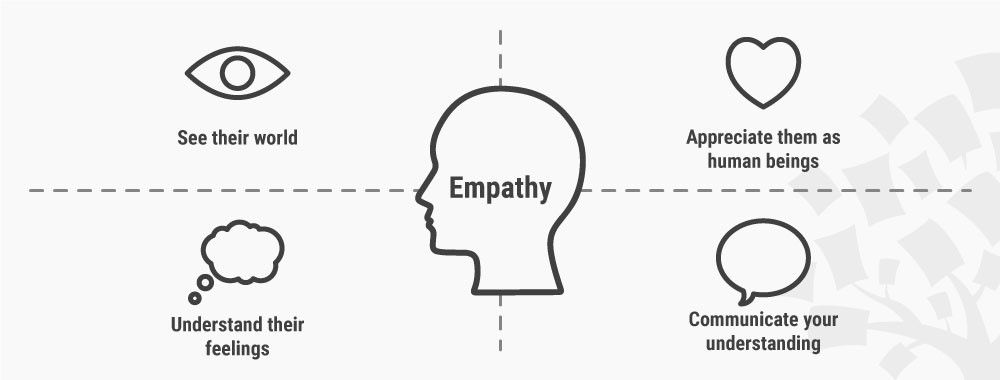

Revolves around a deep interest to understand the people for whom we design products and services.

Helps us observe and develop empathy with the target users.

Enhances our ability to question: in design thinking you question the problem, the assumptions and the implications.

Proves extremely useful when you tackle problems that are ill-defined or unknown.

Involves ongoing experimentation through sketches, prototypes, testing and trials of new concepts and ideas.

- Transcript loading…

In this video, Don Norman , the Grandfather of Human-Centered Design , explains how the approach and flexibility of design thinking can help us tackle major global challenges.

What Are the 5 Phases of Design Thinking?

Hasso-Platner Institute Panorama

Ludwig Wilhelm Wall, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Design thinking is an iterative and non-linear process that contains five phases: 1. Empathize, 2. Define, 3. Ideate, 4. Prototype and 5. Test. You can carry these stages out in parallel, repeat them and circle back to a previous stage at any point in the process.

The core purpose of the process is to allow you to work in a dynamic way to develop and launch innovative ideas.

Design thinking is an iterative and non-linear process that contains five phases: 1. Empathize, 2. Define, 3. Ideate, 4. Prototype and 5. Test.

Design Thinking Makes You Think Outside the Box

Design thinking can help people do out-of-the-box or outside-the-box thinking. People who use this methodology:

Attempt to develop new ways of thinking —ways that do not abide by the dominant or more common problem-solving methods.

Have the intention to improve products, services and processes. They seek to analyze and understand how users interact with products to investigate the conditions in which they operate.

Ask significant questions and challenge assumptions . One element of outside-the-box / out-of-the-box thinking is to falsify previous assumptions—i.e., make it possible to prove whether they’re valid or not.

As you can see, design thinking offers us a means to think outside the box and also dig that bit deeper into problem-solving. It helps us carry out the right kind of research, create prototypes and test our products and services to uncover new ways to meet our users’ needs.

The Grand Old Man of User Experience , Don Norman, who also coined the very term User Experience , explains what Design Thinking is and what’s so special about it:

“…the more I pondered the nature of design and reflected on my recent encounters with engineers, business people and others who blindly solved the problems they thought they were facing without question or further study, I realized that these people could benefit from a good dose of design thinking. Designers have developed a number of techniques to avoid being captured by too facile a solution. They take the original problem as a suggestion, not as a final statement, then think broadly about what the real issues underlying this problem statement might really be (for example by using the " Five Whys " approach to get at root causes). Most important of all, is that the process is iterative and expansive. Designers resist the temptation to jump immediately to a solution to the stated problem. Instead, they first spend time determining what the basic, fundamental (root) issue is that needs to be addressed. They don't try to search for a solution until they have determined the real problem, and even then, instead of solving that problem, they stop to consider a wide range of potential solutions. Only then will they finally converge upon their proposal. This process is called "Design Thinking." — Don Norman, Rethinking Design Thinking

Design Thinking is for Everybody

How many people are involved in the design process when your organization decides to create a new product or service? Teams that build products are often composed of people from a variety of different departments. For this reason, it can be difficult to develop, categorize and organize ideas and solutions for the problems you try to solve. One way you can keep a project on track, and organize the core ideas, is to use a design thinking approach—and everybody can get involved in that!

Tim Brown, CEO of the celebrated innovation and design firm IDEO, emphasizes this in his successful book Change by Design when he says design thinking techniques and strategies belong at every level of a business.

Design thinking is not only for designers but also for creative employees, freelancers and leaders who seek to infuse it into every level of an organization. This widespread adoption of design thinking will drive the creation of alternative products and services for both business and society.

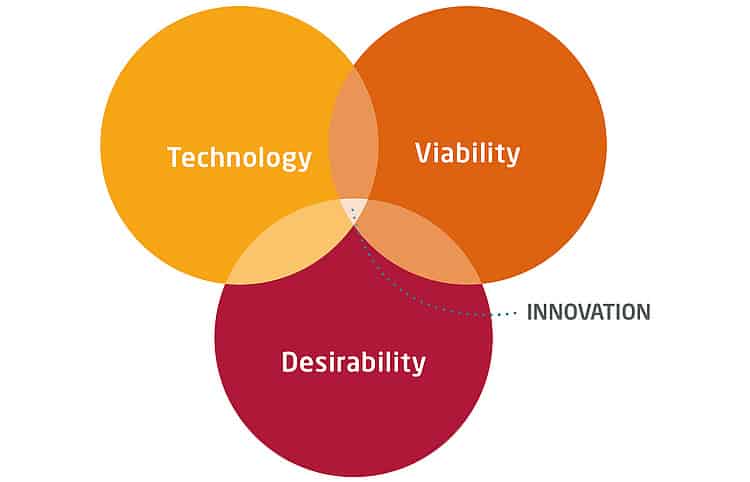

“Design thinking begins with skills designers have learned over many decades in their quest to match human needs with available technical resources within the practical constraints of business. By integrating what is desirable from a human point of view with what is technologically feasible and economically viable, designers have been able to create the products we enjoy today. Design thinking takes the next step, which is to put these tools into the hands of people who may have never thought of themselves as designers and apply them to a vastly greater range of problems.” — Tim Brown, Change by Design, Introduction

Design thinking techniques and strategies belong at every level of a business. You should involve colleagues from a wide range of departments to create a cross-functional team that can utilize knowledge and experience from different specialisms.

Tim Brown also shows how design thinking is not just for everybody—it’s about everybody, too. The process is firmly based on how you can generate a holistic and empathic understanding of the problems people face. Design thinking involves ambiguous, and inherently subjective, concepts such as emotions , needs, motivations and drivers of behavior.

In a solely scientific approach (for example, analyzing data), people are reduced to representative numbers, devoid of emotions. Design thinking, on the other hand, considers both quantitative as well as qualitative dimensions to gain a more complete understanding of user needs . For example, you might observe people performing a task such as shopping for groceries, and you might talk to a few shoppers who feel frustrated with the checkout process at the store (qualitative data). You can also ask them how many times a week they go shopping or feel a certain way at the checkout counter (quantitative data). You can then combine these data points to paint a holistic picture of user pain points, needs and problems.

Tim Brown sums up that design thinking provides a third way to look at problems. It’s essentially a problem-solving approach that has crystallized in the field of design to combine a holistic user-centered perspective with rational and analytical research—all with the goal to create innovative solutions.

“Design thinking taps into capacities we all have but that are overlooked by more conventional problem-solving practices. It is not only human-centered; it is deeply human in and of itself. Design thinking relies on our ability to be intuitive, to recognize patterns, to construct ideas that have emotional meaning as well as functionality , to express ourselves in media other than words or symbols. Nobody wants to run a business based on feeling, intuition, and inspiration, but an overreliance on the rational and the analytical can be just as dangerous. The integrated approach at the core of the design process suggests a ‘third way.’” — Tim Brown, Change by Design, Introduction

Design Thinking Has a Scientific Side

Design thinking is both an art and a science. It combines investigations into ambiguous elements of the problem with rational and analytical research —the scientific side in other words. This magical concoction reveals previously unknown parameters and helps to uncover alternative strategies which lead to truly innovative solutions.

The scientific activities analyze how users interact with products, and investigate the conditions in which they operate. They include tasks which:

Research users’ needs.

Pool experience from previous projects.

Consider present and future conditions specific to the product.

Test the parameters of the problem.

Test the practical application of alternative problem solutions.

Once you arrive at a number of potential solutions, the selection process is then underpinned by rationality. As a designer, you are encouraged to analyze and falsify these solutions to arrive at the best available option for each problem or obstacle identified during phases of the design process.

With this in mind, it may be more correct to say design thinking is not about thinking outside the box, but on its edge, its corner, its flap, and under its bar code—as Clint Runge put it.

Clint Runge is Founder and Managing Director of Archrival, a distinguished youth marketing agency, and adjunct Professor at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Resetting Our Mental Boxes and Developing a Fresh Mindset

Thinking outside of the box can provide an innovative solution to a sticky problem. However, thinking outside of the box can be a real challenge as we naturally develop patterns of thinking that are modeled on the repetitive activities and commonly accessed knowledge we surround ourselves with.

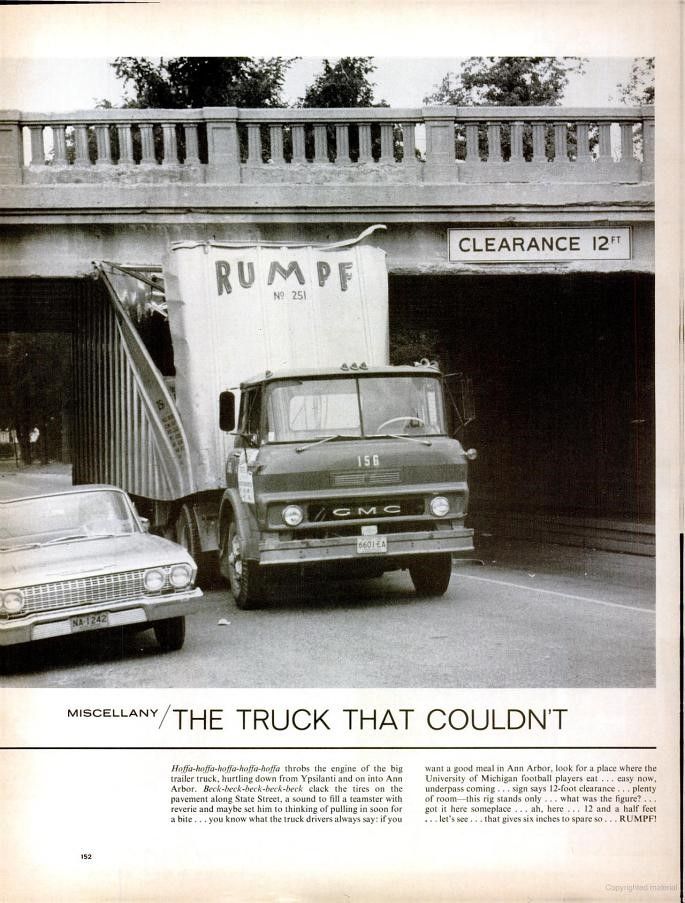

Some years ago, an incident occurred where a truck driver tried to pass under a low bridge. But he failed, and the truck was lodged firmly under the bridge. The driver was unable to continue driving through or reverse out.

The story goes that as the truck became stuck, it caused massive traffic problems, which resulted in emergency personnel, engineers, firefighters and truck drivers gathering to devise and negotiate various solutions for dislodging the trapped vehicle.

Emergency workers were debating whether to dismantle parts of the truck or chip away at parts of the bridge. Each spoke of a solution that fitted within his or her respective level of expertise.

A boy walking by and witnessing the intense debate looked at the truck, at the bridge, then looked at the road and said nonchalantly, “Why not just let the air out of the tires?” to the absolute amazement of all the specialists and experts trying to unpick the problem.

When the solution was tested, the truck was able to drive free with ease, having suffered only the damage caused by its initial attempt to pass underneath the bridge. The story symbolizes the struggles we face where oftentimes the most obvious solutions are the ones hardest to come by because of the self-imposed constraints we work within.

It’s often difficult for us humans to challenge our assumptions and everyday knowledge because we rely on building patterns of thinking in order to not have to learn everything from scratch every time. We rely on doing everyday processes more or less unconsciously—for example, when we get up in the morning, eat, walk, and read—but also when we assess challenges at work and in our private lives. In particular, experts and specialists rely on their solid thought patterns, and it can be very challenging and difficult for experts to start questioning their knowledge.

Stories Have the Power to Inspire

Why did we tell you this story about the truck and the bridge? Well, it’s because stories can help us inspire opportunities, ideas and solutions. Stories are framed around real people and their lives and are important because they’re accounts of specific events, not general statements. They provide us with concrete details which help us imagine solutions to particular problems.

Stories also help you develop the eye of a designer. As you walk around the world, you should try to look for the design stories that are all around you. Say to yourself “that’s an example of great design” or “that's an example of really bad design ” and try to figure out the reasons why.

When you come across something particularly significant, make sure you document it either through photos or video. This will prove beneficial not only to you and your design practice but also to others—your future clients, maybe.

The Take Away

Design Thinking is an iterative and non-linear process. This simply means that the design team continuously uses their results to review, question and improve their initial assumptions, understandings and results. Results from the final stage of the initial work process inform our understanding of the problem, help us determine the parameters of the problem, enable us to redefine the problem, and, perhaps most importantly, provide us with new insights so we can see any alternative solutions that might not have been available with our previous level of understanding.

Design thinking is a non-linear, iterative process that consists of 5 phases: 1. Empathize, 2. Define, 3. Ideate, 4. Prototype and 5. Test. You can carry out the stages in parallel, repeat them and circle back to a previous stage at any point in the process—you don’t have to follow them in order.

It’s a process that digs a bit deeper into problem-solving as you seek to understand your users, challenge assumptions and redefine problems. The design thinking process has both a scientific and artistic side to it, as it asks us to understand and challenge our natural, restrictive patterns of thinking and generate innovative solutions to the problems our users face.

Design thinking is essentially a problem-solving approach that has the intention to improve products. It helps you assess and analyze known aspects of a problem and identify the more ambiguous or peripheral factors that contribute to the conditions of a problem. This contrasts with a more scientific approach where the concrete and known aspects are tested in order to arrive at a solution.

The iterative and ideation -oriented nature of design thinking means we constantly question and acquire knowledge throughout the process. This helps us redefine a problem so we can identify alternative strategies and solutions that aren’t instantly apparent with our initial level of understanding.

Design thinking is often referred to as outside-the-box thinking, as designers attempt to develop new ways of thinking that do not abide by the dominant or more common problem-solving methods—just like artists do.

The design thinking process has become increasingly popular over the last few decades because it was key to the success of many high-profile, global organizations. This outside-the-box thinking is now taught at leading universities across the world and is encouraged at every level of business.

“The ‘Design Thinking’ label is not a myth. It is a description of the application of well-tried design process to new challenges and opportunities, used by people from both design and non-design backgrounds. I welcome the recognition of the term and hope that its use continues to expand and be more universally understood, so that eventually every leader knows how to use design and design thinking for innovation and better results.” — Bill Moggridge, co-founder of IDEO, in Design Thinking: Dear Don

References & Where to Learn More

Enroll in our engaging course, “Design Thinking: The Ultimate Guide”

Here are some examples of good and bad designs to inspire you to look for examples in your daily life.

Read this informative article “What Is Design Thinking, and How Can SMBs Accomplish It?” by Jackie Dove.

Read this insightful article “Rethinking Design Thinking” by Don Norman.

Check out Tim Brown’s book “Change by Design: How Design Thinking Transforms Organizations and Inspires Innovation Introduction,” 2009.

Learn more about Design Thinking in the article “Design Thinking: Dear Don” by Bill Moggridge.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 3.0

Design Thinking: The Ultimate Guide

Get Weekly Design Insights

Topics in this article, what you should read next, the 5 stages in the design thinking process.

- 1.8k shares

Personas – A Simple Introduction

- 1.5k shares

Stage 2 in the Design Thinking Process: Define the Problem and Interpret the Results

- 1.3k shares

What is Ideation – and How to Prepare for Ideation Sessions

- 1.2k shares

Stage 3 in the Design Thinking Process: Ideate

- 4 years ago

Stage 4 in the Design Thinking Process: Prototype

- 3 years ago

Affinity Diagrams: How to Cluster Your Ideas and Reveal Insights

Stage 1 in the Design Thinking Process: Empathise with Your Users

Empathy Map – Why and How to Use It

What Is Empathy and Why Is It So Important in Design Thinking?

Open Access—Link to us!

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge . Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change , cite this article , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge !

Privacy Settings

Our digital services use necessary tracking technologies, including third-party cookies, for security, functionality, and to uphold user rights. Optional cookies offer enhanced features, and analytics.

Experience the full potential of our site that remembers your preferences and supports secure sign-in.

Governs the storage of data necessary for maintaining website security, user authentication, and fraud prevention mechanisms.

Enhanced Functionality

Saves your settings and preferences, like your location, for a more personalized experience.

Referral Program

We use cookies to enable our referral program, giving you and your friends discounts.

Error Reporting

We share user ID with Bugsnag and NewRelic to help us track errors and fix issues.

Optimize your experience by allowing us to monitor site usage. You’ll enjoy a smoother, more personalized journey without compromising your privacy.

Analytics Storage

Collects anonymous data on how you navigate and interact, helping us make informed improvements.

Differentiates real visitors from automated bots, ensuring accurate usage data and improving your website experience.

Lets us tailor your digital ads to match your interests, making them more relevant and useful to you.

Advertising Storage

Stores information for better-targeted advertising, enhancing your online ad experience.

Personalization Storage

Permits storing data to personalize content and ads across Google services based on user behavior, enhancing overall user experience.

Advertising Personalization

Allows for content and ad personalization across Google services based on user behavior. This consent enhances user experiences.

Enables personalizing ads based on user data and interactions, allowing for more relevant advertising experiences across Google services.

Receive more relevant advertisements by sharing your interests and behavior with our trusted advertising partners.

Enables better ad targeting and measurement on Meta platforms, making ads you see more relevant.

Allows for improved ad effectiveness and measurement through Meta’s Conversions API, ensuring privacy-compliant data sharing.

LinkedIn Insights

Tracks conversions, retargeting, and web analytics for LinkedIn ad campaigns, enhancing ad relevance and performance.

LinkedIn CAPI

Enhances LinkedIn advertising through server-side event tracking, offering more accurate measurement and personalization.

Google Ads Tag

Tracks ad performance and user engagement, helping deliver ads that are most useful to you.

Share the knowledge!

Share this content on:

or copy link

Cite according to academic standards

Simply copy and paste the text below into your bibliographic reference list, onto your blog, or anywhere else. You can also just hyperlink to this article.

New to UX Design? We’re giving you a free ebook!

Download our free ebook The Basics of User Experience Design to learn about core concepts of UX design.

In 9 chapters, we’ll cover: conducting user interviews, design thinking, interaction design, mobile UX design, usability, UX research, and many more!

New to UX Design? We’re Giving You a Free ebook!

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- *New* Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

4 Stages of Design Thinking

- 08 Feb 2022

Design thinking has changed the way people think about innovation—especially in business. While the concept originated from designers, professionals have adapted the process to solve business problems more effectively.

Here’s what you need to know about the design thinking process and how you can apply it.

Access your free e-book today.

What Is Design Thinking?

Design thinking is an approach to problem-solving and innovation that’s both user-centric and solutions-based—that is, it focuses on finding solutions instead of problems.

For example, if a business is struggling with bad reviews, design thinking would advise it to focus on improving how it treats customer-facing employees (a solution) rather than scrutinizing reviews (the problem).

User-centric solutions require empathy at all stages and must consider how people are impacted. While this may seem obvious, it’s a crucial element that can’t be overlooked in the innovation process.

Four Stages of Design Thinking

There are several models that systematize the design thinking process. In the online course Design Thinking and Innovation , Harvard Business School Dean Srikant Datar leverages a four-stage framework: clarify, ideate, develop, and implement.

The clarification stage involves observing and framing findings. Your observations form the foundation of your design thinking, so it’s important to be unbiased.

First, identify and empathize with your audience. Where are they coming from? What are their common pain points? Why do they need your solution? How will they benefit?

Once your observations are clearly defined, consolidate them and take note of any that stand out. Outliers can help reframe findings into a problem statement or question that guides the design thinking process to the final stage.

Try to focus on the big picture, and don’t be afraid to frame and reframe observations as you glean additional insights. The clarification stage is vital to the entire process’s success.

With your problem statement or question defined, you can use observations to think of potential solutions. Don’t feel limited as you ideate.

There are several ways you can approach this phase:

- Search for similarities in pain points and categorize them.

- Evaluate what resources you have and consider how they can be used to solve the problem.

- Brainstorm ideas that could yield positive results.

Whatever method you choose, remember that all ideas are possible solutions.

The third stage focuses on developing ideas from the ideation phase. This is done through testing possible solutions and noting the successes and failures of each.

At this point, adjustments aren’t only acceptable but recommended. The purpose isn’t to find the final solution but to test, adjust, prototype, and experiment. If something doesn’t work, try an iteration of it or go back a stage or two in the process.

4. Implement

The final stage—implementation—is the culmination of the previous three phases. It’s where you take all your observations, ideas, and developments and implement a solution.

It’s important to note that testing and experimentation don’t abruptly end. You can expect additional iterations and modifications to the solution that entail returning to a previous stage. Continue refining until you find a successful solution and implement it. Once you’ve done that, the design thinking process is complete.

Check out the video about the design thinking process below, and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more explainer content!

The Importance of Design Thinking Across Industries

Design thinking can be applied in any industry to any problem. Whether you work in manufacturing or finance, you can utilize design thinking to address pain points.

For example, if you work for a finance company struggling with employee engagement—a common problem with the rise in remote work—you could benefit from an unconventional approach to problem-solving . Your leadership and human resources teams could use design thinking to come up with ways to increase employee satisfaction, such as offering more benefits or mental health-focused programs.

Design thinking can seem like a massive undertaking, but it’s an accessible and adaptable method for all professionals who recognize the value of user-centric, solutions-based innovation.

Design Thinking as a Tool

Design thinking is a valuable addition to your professional toolbox. Through its four stages, it teaches how to assess situations with an unbiased view, ideate without assumptions, and continually experiment, test, and reiterate for better results.

Are you interested in learning more about design thinking? Explore our online course Design Thinking and Innovation to discover how to use design thinking principles and innovative problem-solving tools to help you and your business succeed.

About the Author

Skip navigation

- Log in to UX Certification

World Leaders in Research-Based User Experience

Design Thinking 101

July 31, 2016 2016-07-31

- Email article

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on Twitter

In This Article:

Definition of design thinking, why — the advantage, flexibility — adapt to fit your needs, scalability — think bigger, history of design thinking.

Design thinking is an ideology supported by an accompanying process . A complete definition requires an understanding of both.

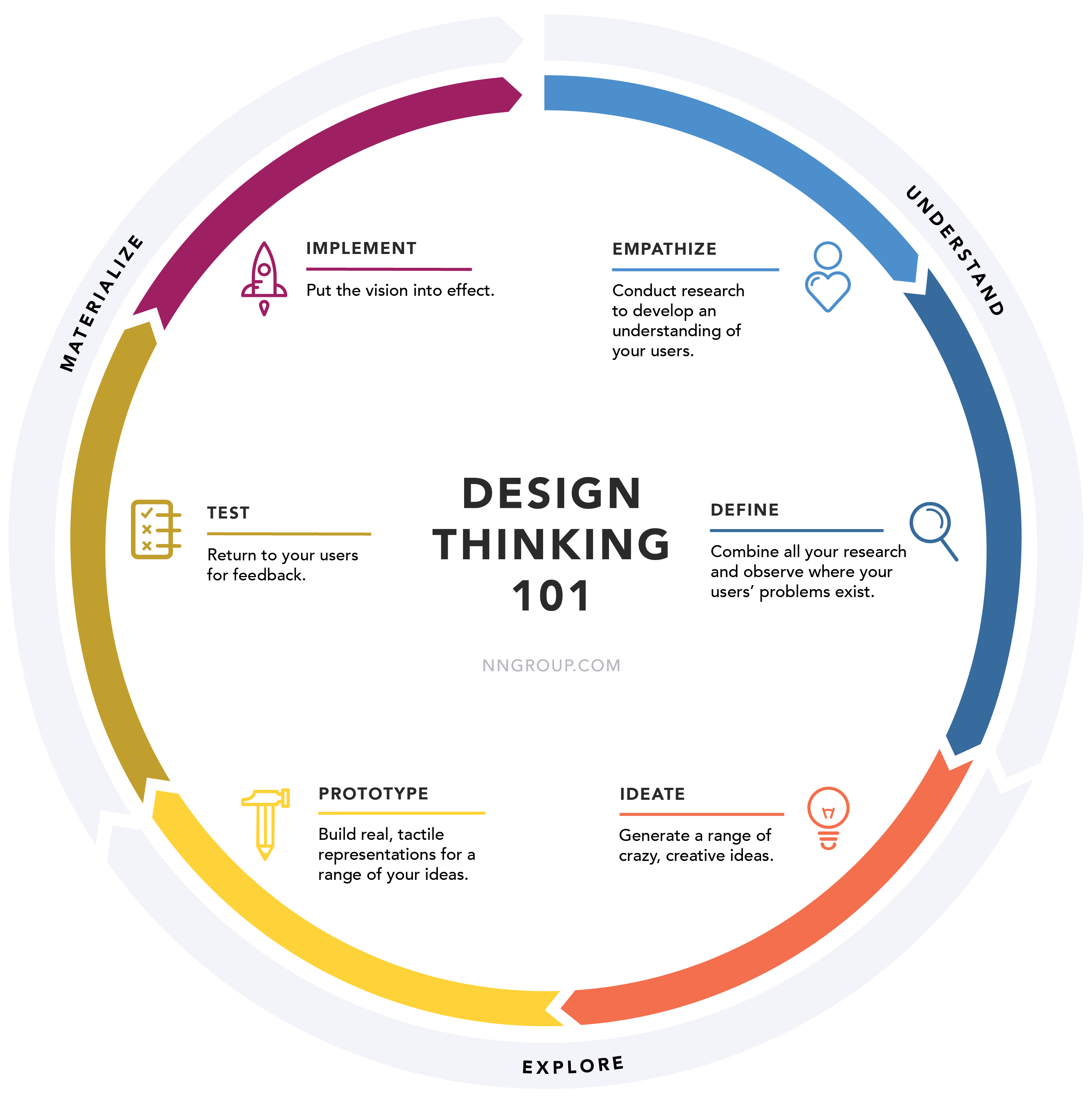

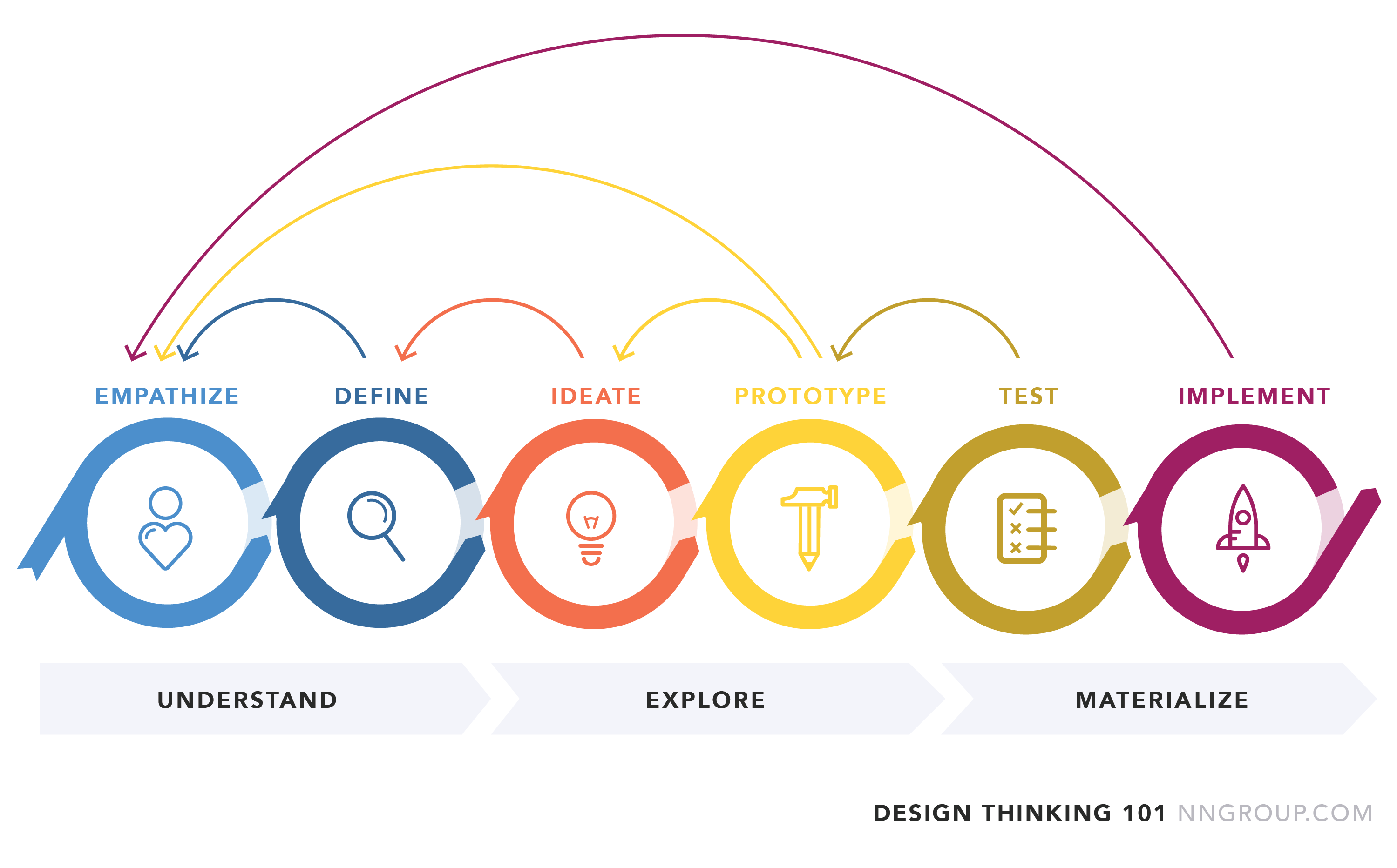

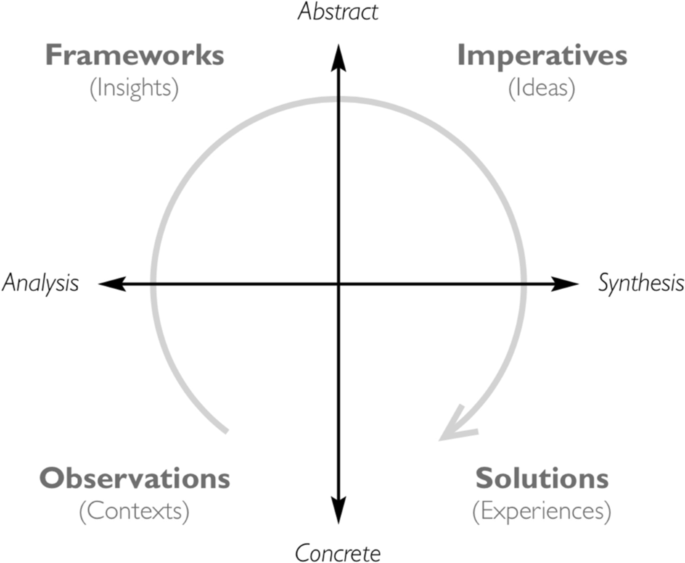

Definition: The design thinking ideology asserts that a hands-on, user-centric approach to problem solving can lead to innovation, and innovation can lead to differentiation and a competitive advantage. This hands-on, user-centric approach is defined by the design thinking process and comprises 6 distinct phases, as defined and illustrated below.

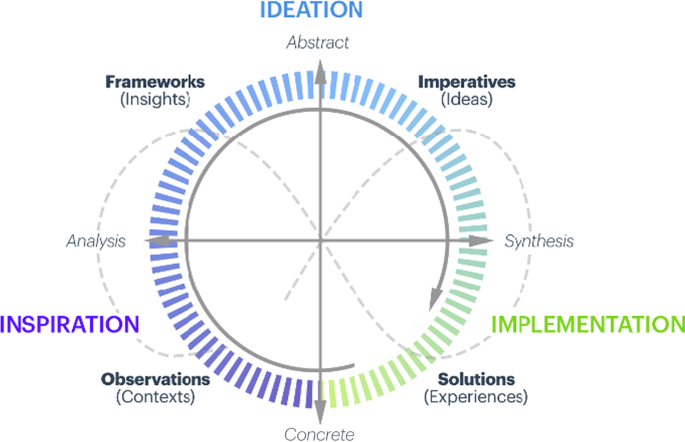

The design-thinking framework follows an overall flow of 1) understand, 2) explore, and 3) materialize. Within these larger buckets fall the 6 phases: empathize, define, ideate, prototype, test, and implement.

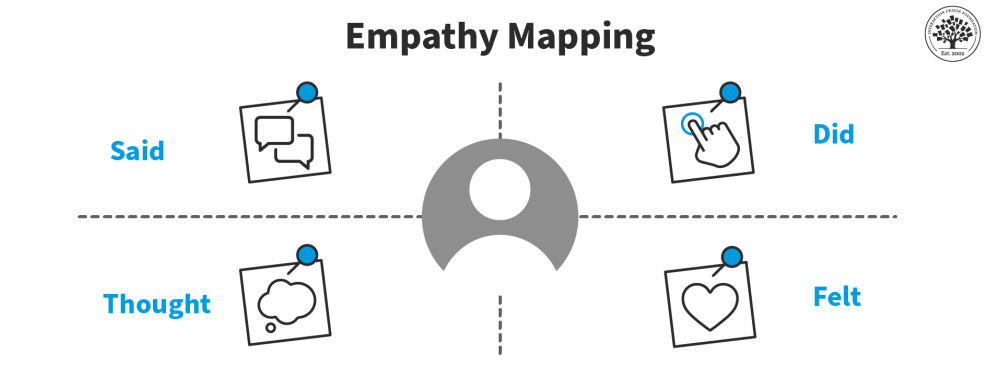

Conduct research in order to develop knowledge about what your users do, say, think, and feel .

Imagine your goal is to improve an onboarding experience for new users. In this phase, you talk to a range of actual users. Directly observe what they do, how they think, and what they want, asking yourself things like ‘what motivates or discourages users?’ or ‘where do they experience frustration?’ The goal is to gather enough observations that you can truly begin to empathize with your users and their perspectives.

Combine all your research and observe where your users’ problems exist. While pinpointing your users’ needs , begin to highlight opportunities for innovation.

Consider the onboarding example again. In the define phase, use the data gathered in the empathize phase to glean insights. Organize all your observations and draw parallels across your users’ current experiences. Is there a common pain point across many different users? Identify unmet user needs.

Brainstorm a range of crazy, creative ideas that address the unmet user needs identified in the define phase. Give yourself and your team total freedom; no idea is too farfetched and quantity supersedes quality.

At this phase, bring your team members together and sketch out many different ideas. Then, have them share ideas with one another, mixing and remixing, building on others' ideas.

Build real, tactile representations for a subset of your ideas. The goal of this phase is to understand what components of your ideas work, and which do not. In this phase you begin to weigh the impact vs. feasibility of your ideas through feedback on your prototypes.

Make your ideas tactile. If it is a new landing page, draw out a wireframe and get feedback internally. Change it based on feedback, then prototype it again in quick and dirty code. Then, share it with another group of people.

Return to your users for feedback. Ask yourself ‘Does this solution meet users’ needs?’ and ‘Has it improved how they feel, think, or do their tasks?’

Put your prototype in front of real customers and verify that it achieves your goals. Has the users’ perspective during onboarding improved? Does the new landing page increase time or money spent on your site? As you are executing your vision, continue to test along the way.

Put the vision into effect. Ensure that your solution is materialized and touches the lives of your end users.

This is the most important part of design thinking, but it is the one most often forgotten. As Don Norman preaches, “we need more design doing.” Design thinking does not free you from the actual design doing. It’s not magic.

“There’s no such thing as a creative type. As if creativity is a verb, a very time-consuming verb. It’s about taking an idea in your head, and transforming that idea into something real. And that’s always going to be a long and difficult process. If you’re doing it right, it’s going to feel like work.” - Milton Glaser

As impactful as design thinking can be for an organization, it only leads to true innovation if the vision is executed. The success of design thinking lies in its ability to transform an aspect of the end user’s life. This sixth step — implement — is crucial.

Why should we introduce a new way to think about product development? There are numerous reasons to engage in design thinking, enough to merit a standalone article, but in summary, design thinking achieves all these advantages at the same time.

Design thinking:

- Is a user-centered process that starts with user data, creates design artifacts that address real and not imaginary user needs, and then tests those artifacts with real users

- Leverages collective expertise and establishes a shared language, as well as buy-in amongst your team

- Encourages innovation by exploring multiple avenues for the same problem

Jakob Nielsen says “ a wonderful interface solving the wrong problem will fail ." Design thinking unfetters creative energies and focuses them on the right problem.

The above process will feel abstruse at first. Don’t think of it as if it were a prescribed step-by-step recipe for success. Instead, use it as scaffolding to support you when and where you need it. Be a master chef, not a line cook: take the recipe as a framework, then tweak as needed.

Each phase is meant to be iterative and cyclical as opposed to a strictly linear process, as depicted below. It is common to return to the two understanding phases, empathize and define, after an initial prototype is built and tested. This is because it is not until wireframes are prototyped and your ideas come to life that you are able to get a true representation of your design. For the first time, you can accurately assess if your solution really works. At this point, looping back to your user research is immensely helpful. What else do you need to know about the user in order to make decisions or to prioritize development order? What new use cases have arisen from the prototype that you didn’t previously research?

You can also repeat phases. It’s often necessary to do an exercise within a phase multiple times in order to arrive at the outcome needed to move forward. For example, in the define phase, different team members will have different backgrounds and expertise, and thus different approaches to problem identification. It’s common to spend an extended amount of time in the define phase, aligning a team to the same focus. Repetition is necessary if there are obstacles in establishing buy-in. The outcome of each phase should be sound enough to serve as a guiding principle throughout the rest of the process and to ensure that you never stray too far from your focus.

The packaged and accessible nature of design thinking makes it scalable. Organizations previously unable to shift their way of thinking now have a guide that can be comprehended regardless of expertise, mitigating the range of design talent while increasing the probability of success. This doesn’t just apply to traditional “designery” topics such as product design, but to a variety of societal, environmental, and economical issues. Design thinking is simple enough to be practiced at a range of scopes; even tough, undefined problems that might otherwise be overwhelming. While it can be applied over time to improve small functions like search, it can also be applied to design disruptive and transformative solutions, such as restructuring the career ladder for teachers in order to retain more talent.

It is a common misconception that design thinking is new. Design has been practiced for ages : monuments, bridges, automobiles, subway systems are all end-products of design processes. Throughout history, good designers have applied a human-centric creative process to build meaningful and effective solutions.

In the early 1900's husband and wife designers Charles and Ray Eames practiced “learning by doing,” exploring a range of needs and constraints before designing their Eames chairs, which continue to be in production even now, seventy years later. 1960's dressmaker Jean Muir was well known for her “common sense” approach to clothing design, placing as much emphasis on how her clothes felt to wear as they looked to others. These designers were innovators of their time. Their approaches can be viewed as early examples of design thinking — as they each developed a deep understanding of their users’ lives and unmet needs. Milton Glaser, the designer behind the famous I ♥ NY logo, describes this notion well: “We’re always looking, but we never really see…it’s the act of attention that allows you to really grasp something, to become fully conscious of it.”

Despite these (and other) early examples of human-centric products, design has historically been an afterthought in the business world, applied only to touch up a product’s aesthetics. This topical design application has resulted in corporations creating solutions which fail to meet their customers’ real needs. Consequently, some of these companies moved their designers from the end of the product-development process, where their contribution is limited, to the beginning. Their human-centric design approach proved to be a differentiator: those companies that used it have reaped the financial benefits of creating products shaped by human needs.

In order for this approach to be adopted across large organizations, it needed to be standardized. Cue design thinking, a formalized framework of applying the creative design process to traditional business problems.

The specific term "design thinking" was coined in the 1990's by David Kelley and Tim Brown of IDEO, with Roger Martin, and encapsulated methods and ideas that have been brewing for years into a single unified concept.

We live in an era of experiences , be they services or products, and we’ve come to have high expectations for these experiences. They are becoming more complex in nature as information and technology continues to evolve. With each evolution comes a new set of unmet needs. While design thinking is simply an approach to problem solving, it increases the probability of success and breakthrough innovation.

Learn more about design thinking in the full-day course Generating Big Ideas with Design Thinking .

Download the illustrations from this article from the link below in a high-resolution version that you can print as a poster or any desired size.

Free Downloads

Related courses, generating big ideas with design thinking.

Unearthing user pain points to drive breakthrough design concepts

Interaction

Service Blueprinting

Use service design to create processes that are core to your digital experience and everything that supports it

Assessing UX Designs Using Proven Principles

Generate insights, product scorecards and competitive analyses, even when you don’t have access to user data

Related Topics

- Design Process Design Process

- Managing UX Teams

Learn More:

Please accept marketing cookies to view the embedded video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6lmvCqvmjfE

The Role of Design

Don Norman · 5 min

Design Thinking Activities

Sarah Gibbons · 5 min

Design Thinking: Top 3 Challenges and Solutions

Related Articles:

Design Thinking: Study Guide

Kate Moran and Megan Brown · 4 min

Service Blueprinting in Practice: Who, When, What

Alita Joyce and Sarah Gibbons · 7 min

Design Thinking Builds Strong Teams

User-Centered Intranet Redesign: Set Up for Success in 11 Steps

Kara Pernice · 10 min

UX Responsibilities in Scrum Events

Anna Kaley · 13 min

Journey Mapping: 9 Frequently Asked Questions

Alita Joyce and Kate Kaplan · 7 min

.css-s5s6ko{margin-right:42px;color:#F5F4F3;}@media (max-width: 1120px){.css-s5s6ko{margin-right:12px;}} Join us: Learn how to build a trusted AI strategy to support your company's intelligent transformation, featuring Forrester .css-1ixh9fn{display:inline-block;}@media (max-width: 480px){.css-1ixh9fn{display:block;margin-top:12px;}} .css-1uaoevr-heading-6{font-size:14px;line-height:24px;font-weight:500;-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;color:#F5F4F3;}.css-1uaoevr-heading-6:hover{color:#F5F4F3;} .css-ora5nu-heading-6{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-box-pack:start;-ms-flex-pack:start;-webkit-justify-content:flex-start;justify-content:flex-start;color:#0D0E10;-webkit-transition:all 0.3s;transition:all 0.3s;position:relative;font-size:16px;line-height:28px;padding:0;font-size:14px;line-height:24px;font-weight:500;-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;color:#F5F4F3;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover{border-bottom:0;color:#CD4848;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover path{fill:#CD4848;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover div{border-color:#CD4848;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover div:before{border-left-color:#CD4848;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:active{border-bottom:0;background-color:#EBE8E8;color:#0D0E10;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:active path{fill:#0D0E10;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:active div{border-color:#0D0E10;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:active div:before{border-left-color:#0D0E10;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover{color:#F5F4F3;} Register now .css-1k6cidy{width:11px;height:11px;margin-left:8px;}.css-1k6cidy path{fill:currentColor;}

- Project planning |

- How to solve problems using the design ...

How to solve problems using the design thinking process

The design thinking process is a problem-solving design methodology that helps you develop solutions in a human-focused way. Initially designed at Stanford’s d.school, the five stage design thinking method can help solve ambiguous questions, or more open-ended problems. Learn how these five steps can help your team create innovative solutions to complex problems.

As humans, we’re approached with problems every single day. But how often do we come up with solutions to everyday problems that put the needs of individual humans first?

This is how the design thinking process started.

What is the design thinking process?

The design thinking process is a problem-solving design methodology that helps you tackle complex problems by framing the issue in a human-centric way. The design thinking process works especially well for problems that are not clearly defined or have a more ambiguous goal.

One of the first individuals to write about design thinking was John E. Arnold, a mechanical engineering professor at Stanford. Arnold wrote about four major areas of design thinking in his book, “Creative Engineering” in 1959. His work was later taught at Stanford’s Hasso-Plattner Institute of Design (also known as d.school), a design institute that pioneered the design thinking process.

This eventually led Nobel Prize laureate Herbert Simon to outline one of the first iterations of the design thinking process in his 1969 book, “The Sciences of the Artificial.” While there are many different variations of design thinking, “The Sciences of the Artificial” is often credited as the basis.

Anatomy of Work Special Report: How to spot—and overcome—the most crucial enterprise challenges

Learn how enterprises can improve processes and productivity, no matter how complex your organization is. With fewer redundancies, leaders and their teams can hit goals faster.

![design thinking is a problem solving framework [Resource Card] AOW Blog Image](https://assets.asana.biz/transform/fdc408f5-063d-4ea7-8d73-cb3ec61704fc/Global-AOW23-Black-Hole?io=transform:fill,width:2560&format=webp)

A non-linear design thinking approach

Design thinking is not a linear process. It’s important to understand that each stage of the process can (and should) inform the other steps. For example, when you’re going through user testing, you may learn about a new problem that didn’t come up during any of the previous stages. You may learn more about your target personas during the final testing phase, or discover that your initial problem statement can actually help solve even more problems, so you need to redefine the statement to include those as well.

Why use the design thinking process

The design thinking process is not the most intuitive way to solve a problem, but the results that come from it are worth the effort. Here are a few other reasons why implementing the design thinking process for your team is worth it.

Focus on problem solving

As human beings, we often don’t go out of our way to find problems. Since there’s always an abundance of problems to solve, we’re used to solving problems as they occur. The design thinking process forces you to look at problems from many different points of view.

The design thinking process requires focusing on human needs and behaviors, and how to create a solution to match those needs. This focus on problem solving can help your design team come up with creative solutions for complex problems.

Encourages collaboration and teamwork

The design thinking process cannot happen in a silo. It requires many different viewpoints from designers, future customers, and other stakeholders . Brainstorming sessions and collaboration are the backbone of the design thinking process.

Foster innovation

The design thinking process focuses on finding creative solutions that cater to human needs. This means your team is looking to find creative solutions for hyper specific and complex problems. If they’re solving unique problems, then the solutions they’re creating must be equally unique.

The iterative process of the design thinking process means that the innovation doesn’t have to end—your team can continue to update the usability of your product to ensure that your target audience’s problems are effectively solved.

The 5 stages of design thinking

Currently, one of the more popular models of design thinking is the model proposed by the Hasso-Plattner Institute of Design (or d.school) at Stanford. The main reason for its popularity is because of the success this process had in successful companies like Google, Apple, Toyota, and Nike. Here are the five steps designated by the d.school model that have helped many companies succeed.

1. Empathize stage

The first stage of the design thinking process is to look at the problem you’re trying to solve in an empathetic manner. To get an accurate representation of how the problem affects people, actively look for people who encountered this problem previously. Asking them how they would have liked to have the issue resolved is a good place to start, especially because of the human-centric nature of the design thinking process.

Empathy is an incredibly important aspect of the design thinking process. The design thinking process requires the designers to put aside any assumptions and unconscious biases they may have about the situation and put themselves in someone else’s shoes.

For example, if your team is looking to fix the employee onboarding process at your company, you may interview recent new hires to see how their onboarding experience went. Another option is to have a more tenured team member go through the onboarding process so they can experience exactly what a new hire experiences.

2. Define stage

Sometimes a designer will encounter a situation when there’s a general issue, but not a specific problem that needs to be solved. One way to help designers clearly define and outline a problem is to create human-centric problem statements.

A problem statement helps frame a problem in a way that provides relevant context in an easy to comprehend way. The main goal of a problem statement is to guide designers working on possible solutions for this problem. A problem statement frames the problem in a way that easily highlights the gap between the current state of things and the end goal.

Tip: Problem statements are best framed as a need for a specific individual. The more specific you are with your problem statement, the better designers can create a human-centric solution to the problem.

Examples of good problem statements:

We need to decrease the number of clicks a potential customer takes to go through the sign-up process.

We need to decrease the new subscriber unsubscribe rate by 10%.

We need to increase the Android app adoption rate by 20%.

3. Ideate stage

This is the stage where designers create potential solutions to solve the problem outlined in the problem statement. Use brainstorming techniques with your team to identify the human-centric solution to the problem defined in step two.

Here are a few brainstorming strategies you can use with your team to come up with a solution:

Standard brainstorm session: Your team gathers together and verbally discusses different ideas out loud.

Brainwrite: Everyone writes their ideas down on a piece of paper or a sticky note and each team member puts their ideas up on the whiteboard.

Worst possible idea: The inverse of your end goal. Your team produces the most goofy idea so nobody will look silly. This takes out the rigidity of other brainstorming techniques. This technique also helps you identify areas that you can improve upon in your actual solution by looking at the worst parts of an absurd solution.

It’s important that you don’t discount any ideas during the ideation phase of brainstorming. You want to have as many potential solutions as possible, as new ideas can help trigger even better ideas. Sometimes the most creative solution to a problem is the combination of many different ideas put together.

4. Prototype stage

During the prototype phase, you and your team design a few different variations of inexpensive or scaled down versions of the potential solution to the problem. Having different versions of the prototype gives your team opportunities to test out the solution and make any refinements.

Prototypes are often tested by other designers, team members outside of the initial design department, and trusted customers or members of the target audience. Having multiple versions of the product gives your team the opportunity to tweak and refine the design before testing with real users. During this process, it’s important to document the testers using the end product. This will give you valuable information as to what parts of the solution are good, and which require more changes.

After testing different prototypes out with teasers, your team should have different solutions for how your product can be improved. The testing and prototyping phase is an iterative process—so much so that it’s possible that some design projects never end.

After designers take the time to test, reiterate, and redesign new products, they may find new problems, different solutions, and gain an overall better understanding of the end-user. The design thinking framework is flexible and non-linear, so it’s totally normal for the process itself to influence the end design.

Tips for incorporating the design thinking process into your team

If you want your team to start using the design thinking process, but you’re unsure of how to start, here are a few tips to help you out.

Start small: Similar to how you would test a prototype on a small group of people, you want to test out the design thinking process with a smaller team to see how your team functions. Give this test team some small projects to work on so you can see how this team reacts. If it works out, you can slowly start rolling this process out to other teams.

Incorporate cross-functional team members : The design thinking process works best when your team members collaborate and brainstorm together. Identify who your designer’s key stakeholders are and ensure they’re included in the small test team.

Organize work in a collaborative project management software : Keep important design project documents such as user research, wireframes, and brainstorms in a collaborative tool like Asana . This way, team members will have one central source of truth for anything relating to the project they’re working on.

Foster collaborative design thinking with Asana

The design thinking process works best when your team works collaboratively. You don’t want something as simple as miscommunication to hinder your projects. Instead, compile all of the information your team needs about a design project in one place with Asana.

Related resources

Unmanaged business goals don’t work. Here’s what does.

How Asana uses work management to drive product development

How Asana uses work management to streamline project intake processes

How Asana uses work management for smoother creative production

About this site

Design thinking in context, design thinking today.

- Designer's Mindset

- Adoption and Integration

- Teaching and Learning

- New Applications

- Privacy Policy

Design Thinking Defined

—tim brown, executive chair of ideo.

Thinking like a designer can transform the way organizations develop products, services, processes, and strategy. This approach, which is known as design thinking, brings together what is desirable from a human point of view with what is technologically feasible and economically viable. It also allows people who aren't trained as designers to use creative tools to address a vast range of challenges.

IDEO did not invent design thinking, but we have become known for practicing it and applying it to solving problems small and large. It’s fair to say that we were in the right place at the right time. When we looked back over our shoulder, we discovered that there was a revolutionary movement behind us.

This design thinking site is just one small part of the IDEO network. There’s much more, including full online courses we've developed on many topics related to design thinking and its applications. We fundamentally believe in the power of design thinking as a methodology for creating positive impact in the world—and we bring that belief into our client engagements as well as into creating open resources such as this.

At IDEO, we’re often asked to share what we know about design thinking. We’ve developed this website in response to that request. Here, we introduce design thinking, how it came to be, how it is being used, and steps and tools for mastering it. You’ll find our particular take on design thinking, as well as the perspectives of others. Everything on this site is free for you to use and share with proper attribution .

(From 2008-2018, designthinking.ideo.com was the home of IDEO's design thinking blog, written by our CEO, Tim Brown . You can find that blog here .)