Romanticism in Literature: Definition and Examples

Finding beauty in nature and the common man.

Apic / Getty Images

- Authors & Texts

- Top Picks Lists

- Study Guides

- Best Sellers

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/JS800-800-5b70ad0c46e0fb00501895cd.jpg)

- B.A., English, Rutgers University

Romanticism was a literary movement that began in the late 18th century, ending around the middle of the 19th century—although its influence continues to this day. Marked by a focus on the individual (and the unique perspective of a person, often guided by irrational, emotional impulses), a respect for nature and the primitive, and a celebration of the common man, Romanticism can be seen as a reaction to the huge changes in society that occurred during this period, including the revolutions that burned through countries like France and the United States, ushering in grand experiments in democracy.

Key Takeaways: Romanticism in Literature

- Romanticism is a literary movement spanning roughly 1790–1850.

- The movement was characterized by a celebration of nature and the common man, a focus on individual experience, an idealization of women, and an embrace of isolation and melancholy.

- Prominent Romantic writers include John Keats, William Wordsworth, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and Mary Shelley.

Romanticism Definition

The term Romanticism does not stem directly from the concept of love, but rather from the French word romaunt (a romantic story told in verse). Romanticism focused on emotions and the inner life of the writer, and often used autobiographical material to inform the work or even provide a template for it, unlike traditional literature at the time.

Romanticism celebrated the primitive and elevated "regular people" as being deserving of celebration, which was an innovation at the time. Romanticism also fixated on nature as a primordial force and encouraged the concept of isolation as necessary for spiritual and artistic development.

Characteristics of Romanticism

Romantic literature is marked by six primary characteristics: celebration of nature, focus on the individual and spirituality, celebration of isolation and melancholy, interest in the common man, idealization of women, and personification and pathetic fallacy.

Celebration of Nature

Romantic writers saw nature as a teacher and a source of infinite beauty. One of the most famous works of Romanticism is John Keats’ To Autumn (1820):

Where are the songs of Spring? Ay, where are they? Think not of them, thou hast thy music too,– While barred clouds bloom the soft-dying day, And touch the stubble-plains with rosy hue; Then in a wailful choir the small gnats mourn Among the river sallows, borne aloft Or sinking as the light wind lives or dies;

Keats personifies the season and follows its progression from the initial arrival after summer, through the harvest season, and finally to autumn’s end as winter takes its place.

Focus on the Individual and Spirituality

Romantic writers turned inward, valuing the individual experience above all else. This in turn led to heightened sense of spirituality in Romantic work, and the addition of occult and supernatural elements.

The work of Edgar Allan Poe exemplifies this aspect of the movement; for example, The Raven tells the story of a man grieving for his dead love (an idealized woman in the Romantic tradition) when a seemingly sentient Raven arrives and torments him, which can be interpreted literally or seen as a manifestation of his mental instability.

Celebration of Isolation and Melancholy

Ralph Waldo Emerson was a very influential writer in Romanticism; his books of essays explored many of the themes of the literary movement and codified them. His 1841 essay Self-Reliance is a seminal work of Romantic writing in which he exhorts the value of looking inward and determining your own path, and relying on only your own resources.

Related to the insistence on isolation, melancholy is a key feature of many works of Romanticism, usually seen as a reaction to inevitable failure—writers wished to express the pure beauty they perceived and failure to do so adequately resulted in despair like the sort expressed by Percy Bysshe Shelley in A Lament :

O world! O life! O time! On whose last steps I climb. Trembling at that where I had stood before; When will return the glory of your prime? No more—Oh, never more!

Interest in the Common Man

William Wordsworth was one of the first poets to embrace the concept of writing that could be read, enjoyed, and understood by anyone. He eschewed overly stylized language and references to classical works in favor of emotional imagery conveyed in simple, elegant language, as in his most famous poem I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud :

I wandered lonely as a Cloud That floats on high o'er vales and Hills, When all at once I saw a crowd, A host, of golden Daffodils; Beside the Lake, beneath the trees, Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

Idealization of Women

In works such as Poe’s The Raven , women were always presented as idealized love interests, pure and beautiful, but usually without anything else to offer. Ironically, the most notable novels of the period were written by women (Jane Austen, Charlotte Brontë, and Mary Shelley, for example), but had to be initially published under male pseudonyms because of these attitudes. Much Romantic literature is infused with the concept of women being perfect innocent beings to be adored, mourned, and respected—but never touched or relied upon.

Personification and Pathetic Fallacy

Romantic literature’s fixation on nature is characterized by the heavy use of both personification and pathetic fallacy. Mary Shelley used these techniques to great effect in Frankenstein :

Its fair lakes reflect a blue and gentle sky; and, when troubled by the winds, their tumult is but as the play of a lively infant, when compared to the roarings of the giant ocean.

Romanticism continues to influence literature today; Stephenie Meyers’ Twilight novels are clear descendants of the movement, incorporating most of the characteristics of classic Romanticism despite being published a century and half after the end of the movement’s active life.

- The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. “Romanticism.” Encyclopedia Britannica, Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc., 19 Nov. 2019, https://www.britannica.com/art/Romanticism.

- Parker, James. “A Book That Examines the Writing Processes of Two Poetry Giants.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 23 July 2019, https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2019/07/how-two-literary-giants-wrote-their-best-poetry/594514/.

- Alhathani, Safa. “EN571: Literature & Technology.” EN571 Literature Technology, 13 May 2018, https://commons.marymount.edu/571sp17/2018/05/13/analysis-of-romanticism-in-frankenstein-through-digital-tools/.

- “William Wordsworth.” Poetry Foundation, Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/william-wordsworth.

- An Introduction to the Romantic Period

- A Classic Collection of Bird Poems

- Romanticism in Art History From 1800-1880

- 14 Classic Poems Everyone Should Know

- A Brief Overview of British Literary Periods

- Personification

- Poems of Protest and Revolution

- 42 Must-Read Feminist Female Authors

- Biography of Mary Shelley, English Novelist, Author of 'Frankenstein'

- What Was the Main Goal of Mary Wollstonecraft's Advocacy?

- Inexpressibility (Rhetoric)

- A Guide to Wordsworth's Themes of Memory and Nature in 'Tintern Abbey'

- William Wordsworth

- A Collection of Classic Love Poetry for Your Sweetheart

- How to Find the Main Idea - Worksheet

- William Wordsworth's 'Daffodils' Poem

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

- Romanticism

Théodore Gericault

Evening: Landscape with an Aqueduct

Alfred Dedreux (1810–1860) as a Child

The Start of the Race of the Riderless Horses

Horace Vernet

Jean-Louis-André-Théodore Gericault (1791–1824)

Inundated Ruins of a Monastery

Karl Blechen

Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop's Grounds

John Constable

Eugène Delacroix

Royal Tiger

Stormy Coast Scene after a Shipwreck

French Painter

Mother and Child by the Sea

Johan Christian Dahl

The Natchez

Wanderer in the Storm

Julius von Leypold

The Abduction of Rebecca

Jewish Woman of Algiers Seated on the Ground

Théodore Chassériau

The Virgin Adoring the Host

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres

Ovid among the Scythians

Kathryn Calley Galitz Department of European Paintings, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2004

Romanticism, first defined as an aesthetic in literary criticism around 1800, gained momentum as an artistic movement in France and Britain in the early decades of the nineteenth century and flourished until mid-century. With its emphasis on the imagination and emotion, Romanticism emerged as a response to the disillusionment with the Enlightenment values of reason and order in the aftermath of the French Revolution of 1789. Though often posited in opposition to Neoclassicism , early Romanticism was shaped largely by artists trained in Jacques Louis David’s studio, including Baron Antoine Jean Gros, Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson, and Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres. This blurring of stylistic boundaries is best expressed in Ingres’ Apotheosis of Homer and Eugène Delacroix’s Death of Sardanapalus (both Museé du Louvre, Paris), which polarized the public at the Salon of 1827 in Paris. While Ingres’ work seemingly embodied the ordered classicism of David in contrast to the disorder and tumult of Delacroix, in fact both works draw from the Davidian tradition but each ultimately subverts that model, asserting the originality of the artist—a central notion of Romanticism.

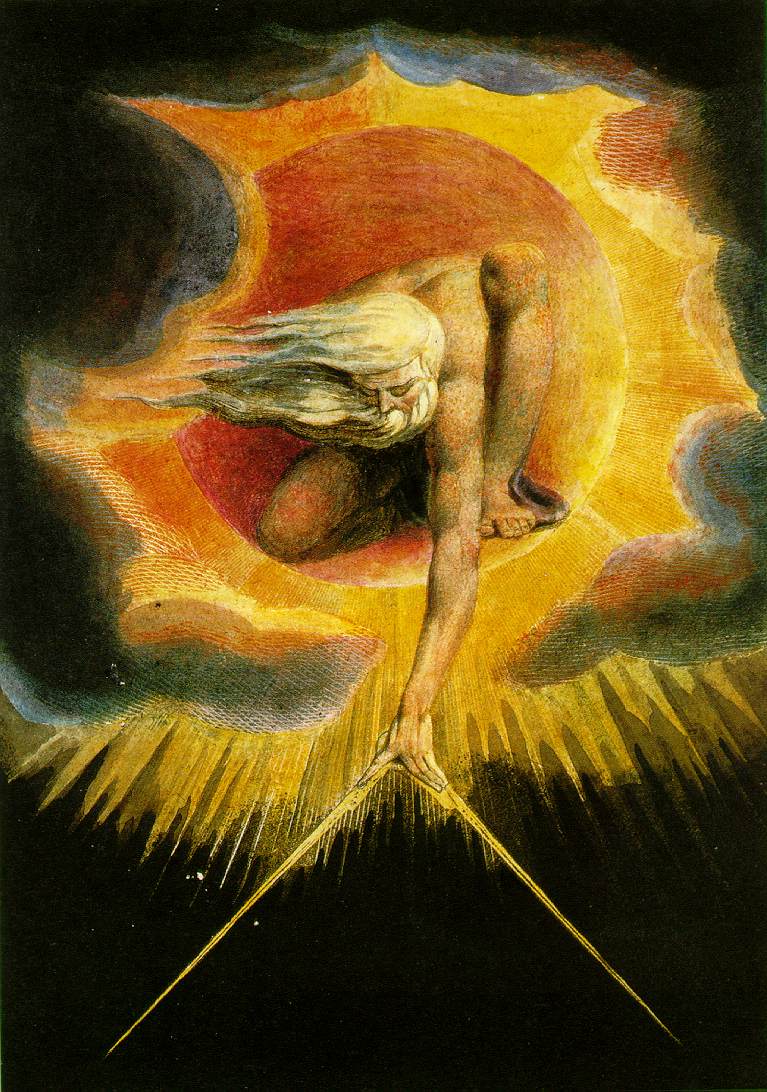

In Romantic art, nature—with its uncontrollable power, unpredictability, and potential for cataclysmic extremes—offered an alternative to the ordered world of Enlightenment thought. The violent and terrifying images of nature conjured by Romantic artists recall the eighteenth-century aesthetic of the Sublime. As articulated by the British statesman Edmund Burke in a 1757 treatise and echoed by the French philosopher Denis Diderot a decade later, “all that stuns the soul, all that imprints a feeling of terror, leads to the sublime.” In French and British painting of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the recurrence of images of shipwrecks ( 2003.42.56 ) and other representations of man’s struggle against the awesome power of nature manifest this sensibility. Scenes of shipwrecks culminated in 1819 with Théodore Gericault’s strikingly original Raft of the Medusa (Louvre), based on a contemporary event. In its horrifying explicitness, emotional intensity, and conspicuous lack of a hero, The Raft of the Medusa became an icon of the emerging Romantic style. Similarly, J. M. W. Turner’s 1812 depiction of Hannibal and his army crossing the Alps (Tate, London), in which the general and his troops are dwarfed by the overwhelming scale of the landscape and engulfed in the swirling vortex of snow, embodies the Romantic sensibility in landscape painting. Gericault also explored the Romantic landscape in a series of views representing different times of day; in Evening: Landscape with an Aqueduct ( 1989.183 ), the dramatic sky, blasted tree, and classical ruins evoke a sense of melancholic reverie.

Another facet of the Romantic attitude toward nature emerges in the landscapes of John Constable , whose art expresses his response to his native English countryside. For his major paintings, Constable executed full-scale sketches, as in a view of Salisbury Cathedral ( 50.145.8 ); he wrote that a sketch represents “nothing but one state of mind—that which you were in at the time.” When his landscapes were exhibited in Paris at the Salon of 1824, critics and artists embraced his art as “nature itself.” Constable’s subjective, highly personal view of nature accords with the individuality that is a central tenet of Romanticism.

This interest in the individual and subjective—at odds with eighteenth-century rationalism—is mirrored in the Romantic approach to portraiture. Traditionally, records of individual likeness, portraits became vehicles for expressing a range of psychological and emotional states in the hands of Romantic painters. Gericault probed the extremes of mental illness in his portraits of psychiatric patients, as well as the darker side of childhood in his unconventional portrayals of children. In his portrait of Alfred Dedreux ( 41.17 ), a young boy of about five or six, the child appears intensely serious, more adult than childlike, while the dark clouds in the background convey an unsettling, ominous quality.

Such explorations of emotional states extended into the animal kingdom, marking the Romantic fascination with animals as both forces of nature and metaphors for human behavior. This curiosity is manifest in the sketches of wild animals done in the menageries of Paris and London in the 1820s by artists such as Delacroix, Antoine-Louis Barye, and Edwin Landseer. Gericault depicted horses of all breeds—from workhorses to racehorses—in his work. Lord Byron’s 1819 tale of Mazeppa tied to a wild horse captivated Romantic artists from Delacroix to Théodore Chassériau, who exploited the violence and passion inherent in the story. Similarly, Horace Vernet, who exhibited two scenes from Mazeppa in the Salon of 1827 (both Musée Calvet, Avignon), also painted the riderless horse race that marked the end of the Roman Carnival, which he witnessed during his 1820 visit to Rome. His oil sketch ( 87.15.47 ) captures the frenetic energy of the spectacle, just before the start of the race. Images of wild, unbridled animals evoked primal states that stirred the Romantic imagination.

Along with plumbing emotional and behavioral extremes, Romantic artists expanded the repertoire of subject matter, rejecting the didacticism of Neoclassical history painting in favor of imaginary and exotic subjects. Orientalism and the worlds of literature stimulated new dialogues with the past as well as the present. Ingres’ sinuous odalisques ( 38.65 ) reflect the contemporary fascination with the exoticism of the harem, albeit a purely imagined Orient, as he never traveled beyond Italy. In 1832, Delacroix journeyed to Morocco, and his trip to North Africa prompted other artists to follow. In 1846, Chassériau documented his visit to Algeria in notebooks filled with watercolors and drawings, which later served as models for paintings done in his Paris studio ( 64.188 ). Literature offered an alternative form of escapism. The novels of Sir Walter Scott, the poetry of Lord Byron, and the drama of Shakespeare transported art to other worlds and eras. Medieval England is the setting of Delacroix’s tumultuous Abduction of Rebecca ( 03.30 ), which illustrates an episode from Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe .

In its stylistic diversity and range of subjects, Romanticism defies simple categorization. As the poet and critic Charles Baudelaire wrote in 1846, “Romanticism is precisely situated neither in choice of subject nor in exact truth, but in a way of feeling.”

Galitz, Kathryn Calley. “Romanticism.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/roma/hd_roma.htm (October 2004)

Further Reading

Brookner, Anita. Romanticism and Its Discontents . New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux; : , 2000.

Honour, Hugh. Romanticism . New York: Harper & Row, 1979.

Additional Essays by Kathryn Calley Galitz

- Galitz, Kathryn Calley. “ The Legacy of Jacques Louis David (1748–1825) .” (October 2004)

- Galitz, Kathryn Calley. “ Gustave Courbet (1819–1877) .” (May 2009)

- Galitz, Kathryn Calley. “ The French Academy in Rome .” (October 2003)

Related Essays

- John Constable (1776–1837)

- Poets, Lovers, and Heroes in Italian Mythological Prints

- The Salon and the Royal Academy in the Nineteenth Century

- The Transformation of Landscape Painting in France

- Watercolor Painting in Britain, 1750–1850

- The Aesthetic of the Sketch in Nineteenth-Century France

- Auguste Rodin (1840–1917)

- The Countess da Castiglione

- Gustave Courbet (1819–1877)

- James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903) as Etcher

- The Legacy of Jacques Louis David (1748–1825)

- Lithography in the Nineteenth Century

- The Nabis and Decorative Painting

- Nadar (1820–1910)

- Nineteenth-Century Classical Music

- Nineteenth-Century French Realism

- Orientalism in Nineteenth-Century Art

- Paolo Veronese (1528–1588)

- The Pre-Raphaelites

- Shakespeare and Art, 1709–1922

- Shakespeare Portrayed

- Sixteenth-Century Painting in Venice and the Veneto

- Thomas Eakins (1844–1916): Painting

- Women Artists in Nineteenth-Century France

- France, 1800–1900 A.D.

- Great Britain and Ireland, 1800–1900 A.D.

- 19th Century A.D.

- Architecture

- British Literature / Poetry

- Classical Ruins

- French Literature / Poetry

- Great Britain and Ireland

- History Painting

- Literature / Poetry

- Oil on Canvas

- Orientalism

- Preparatory Study

Artist or Maker

- Adamson, Robert

- Blake, William

- Blechen, Karl

- Chassériau, Théodore

- Constable, John

- Dahl, Johan Christian

- David, Jacques Louis

- Delacroix, Eugène

- Eakins, Thomas

- Friedrich, Caspar David

- Fuseli, Henry

- Gericault, Théodore

- Girodet-Trioson, Anne-Louis

- Gros, Antoine Jean

- Ingres, Jean Auguste Dominique

- Købke, Christen

- Turner, Joseph Mallord William

- Vernet, Horace

- Von Carolsfeld, Julius Schnorr

- Von Leypold, Julius

Online Features

- 82nd & Fifth: “Motion Picture” by Asher Miller

- Connections: “Fatherhood” by Tim Healing

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Literature › Romanticism in England

Romanticism in England

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on November 29, 2017 • ( 9 )

In England, the ground for Romanticism was prepared in the latter half of the eighteenth century through the economic, political, and cultural transformations mentioned in the preceding chapters. The system of absolute government crumbled even earlier in Britain than elsewhere; nationalistic sentiment sharpened, imperialistic endeavors widened, and the century saw an increasing growth of periodical literature which catered to the middle classes. The ideals of neoclassicism, such as decorum, order, normality of experience, and moderation, were increasingly displaced by an emphasis on individual experience. The moral function of literature was increasingly counterbalanced by an emphasis on aesthetic pleasure and the psychology of the reader’s response to beauty and sublimity. An emphasis on originality and genius supplanted the primacy of imitation of classical authors or nature. Thinkers such as Locke , Hume , and Burke had been instrumental in these shifts of taste and philosophical orientation. Critics such as Edward Young , William Duff , and Joseph Warton produced influential treatises: Young’s Conjectures on Original Composition (1759) and Duff’s An Essay on Original Genius (1767) stressed the claims of originality, genius, and the creative imagination. Poets and critics of this period, such as Richard Hurd , idealized the Middle Ages and expressed an admiration for primitive societies and a native literary tradition, in which the figures of Chaucer, Spenser, and Shakespeare were accorded prominence. The artist Sir Joshua Reynolds praised the genius and sublimity of the Renaissance painter Michelangelo .

The early British practitioners of Romanticism included Thomas Gray , Oliver Goldsmith , and Robert Burns . The English movement reached its most mature expression in the work of William Wordsworth , who saw nature as embodying a universal spirit, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge who, drawing on the work of Kant, Fichte, and Schelling, gave archetypal formulation to the powers of the poetic imagination. Like their European counterparts, the English Romantics reacted at first favorably to the French Revolution and saw their own cultural and literary program as revolutionary. As many critics, ranging from Lukács to Abrams and Raymond Williams , have noted, the Romantics saw themselves as inheriting a world disfigured by the squalor of bourgeois economic and political practice, a world fragmented by dualisms such as individual and society, past and present, sensation and intellect, reason and emotion; their task was to seek once again a unifying vision, usually through the aesthetic and cultural realms.

Shelley ’s A Defence of Poetry is a powerful and beautifully expressed manifesto of fundamental Romantic principles, detailing the supremacy of imagination over reason, and the exalted status of poetry. Keats’ brief literary-critical insights are centered around the notion of “ negative capability .” In a letter to Benjamin Bailey , Keats suggests that, in poetic creation, the poet acts as a catalyst for the reaction of other elements, stating that “Men of Genius are great as certain ethereal Chemicals operating on the Mass of neutral intellect . . . they have not any individuality, any determined Character.”1 Writing to Richard Woodhouse , Keats distances himself from “the wordsworthian or egotistical sublime”: “the poetical Character . . . has no self – it is every thing and nothing – It has no character . . . A Poet . . . has no Identity – he is continually in for – and filling some other Body” ( Letters , 386–387). The idea behind this “annihilation” of character is that the poet’s mentality infuses, and is infused by, everything. Deploying what Keats calls the “negative capability” of abstaining from particular positions or dogmas, it loses itself wholly among the objects and events of the external world which are its poetic material ( Letters , 184, 386–387). The ego, then, should not interpose itself between the poet and his “direct” sensations. Keats ’ apparent identification of beauty with truth in his Ode on a Grecian Urn has received much critical attention. Though the Romantics are often viewed as writing confessional poetry and expressing personality, it is significant that both Keats and Shelley rejected this notion. Like Shelley, Byron rebelled against conventional beliefs, and in his poems such as Don Juan engaged in pungent satire of the hypocrisy and corruption of those in power. His stormy and eccentric life ended in the struggle for Greek independence.

Share this:

Categories: Literature

Tags: A Defence of Poetry , An Essay on Original Genius , Benjamin Bailey , Conjectures on Original Composition , David Hume , Don Juan , Dorothy Wordsworth , Edward Young , Frankenstein , John Keats , Joseph Warton , Kant , Literary Criticism , Literary Theory , Locke , Lord Byron , Mary Shelley , Michelangelo , negative capability , Oliver Goldsmith , PB Shelley , Poetry , Pursuits of Literature , Richard Hurd , Richard Woodhouse , Robert Burns , Romanticism , Romanticism in England , Samuel Taylor Coleridge , Sir Joshua Reynolds , The Marriage of Heaven and Hell , Thomas Gray , Thomas James Mathias , William Blake , William Duff , Wordsworth

Related Articles

- Romanticism in America – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Literary Criticism of Giovanni Boccaccio – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Literary Criticism of Edmund Burke – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Romanticism in Germany – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Romanticism in France – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Literary Criticism of Germaine de Staël – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Science Fiction Criticism – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Introduction to Science Fiction – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Feminist Novels and Novelists | Literary Theory and Criticism

Romantic Age in English Literature

The late 18th century through the middle of the 19th century, known as the Romantic Period in English literature, was a pivotal time marked by a significant shift in socioeconomic, philosophical, and artistic perspectives. The Enlightenment ideas and the rapid industrialization triggered an intense reaction that gave rise to this era.

The Romantics defended the superiority of passion, individuality, and imagination in opposition to the Enlightenment’s focus on reason, rationality, and empiricism. They looked for inspiration and insight by delving into the depths of human emotion, the mysteries of nature, and the capacity of the human imagination. This was a shift from the Enlightenment’s belief that reason and science were the main forces behind advancement in society.

Table of Contents

Historical and Cultural Background

The cultural and historical context of the Romantic Period in English literature was greatly affected by a number of important factors that helped to define this period.

The worldview of the Romantics was significantly influenced by the French Revolution and political instability. The turbulent events of the French Revolution in the late 18th century inspired political idealism, optimism, and revolt throughout Europe. The Romantics, which included writers like William Wordsworth and Lord Byron, were profoundly influenced by the revolutionary spirit and saw in it a chance for societal transformation and the emancipation of the individual from repressive structures. However, they also had to deal with the violence and despair that frequently followed revolutionary fervor, giving rise to complicated and even contradictory perspectives on political change.

Read More: Enlightenment in English Literature

Romanticism ‘s strong affinity for the sublime and the natural world developed in response to the era’s rapid industrialization and urbanization. The natural world was valued by the Romantics as a source of creativity, comfort, and spiritual regeneration. They saw the natural world as both a haven for the human spirit and a window towards the divine. The idea of the sublime, which included both the stupendous majesty of nature and the overwhelming strength of human emotions, also emerged as a major theme in Romantic literature. John Keats and Samuel Taylor Coleridge were two authors who explored the sublime in their writings, creating sensations of both transcendence and dread.

Read More: Romanticism in English Literature

The Romantic Period was greatly influenced by technological development and socioeconomic transformations, notably the rapid industrialization of society. Although these changes helped in economic development, they also brought about social inequality, labor exploitation, and environmental deterioration. The Romantics sharply criticized these unfavorable effects and frequently illustrated how industrialization caused alienation from and a loss of connection to nature. Their works represented a yearning for a life that was less complicated, more peaceful, and in harmony with the cycles of nature.

Literature of the Romantic Period

The literature of the Romantic Period was distinguished by a wide variety of subjects and genres, which captured the significant social and cultural transformations of the time.

Poetry of Nature and Emotion: The praise of the natural world and the exploration of profound human emotions were two of the most notable and enduring features of Romantic literature. William Wordsworth , Samuel Taylor Coleridge , and John Keats were among the poets of this time who focused on the splendor and grandeur of the natural world. They regarded nature as a way to connect with more profound emotional and spiritual truths as well as a source of aesthetic inspiration. Wordsworth’s “Lines Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey” perfectly encapsulates this romanticism that is rooted in nature, while Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan” explores the mystical and surreal facets of nature. In contrast, Keats wrote odes that praised love, beauty, and mortality, as shown in poems like “Ode to a Nightingale” and “Ode on a Grecian Urn.”

Read More: Coleridge’s concept of imagination and fancy

Gothic Literature

As a result of the Romantic Era’s interest in the enigmatic, supernatural, and darker facets of human nature, Gothic literature developed into a unique and distinctive literary style. With frequent blending of the real and the supernatural, gothic literature tried to explore the eerie, the macabre, and the weird.

The ideas and aesthetic of Gothic literature from the Romantic Era are best exemplified in two classic works. The revolutionary book “ Frankenstein” by Mary Shelley, which was first published in 1818, examines the effects of scientific experimentation as well as the urge to go beyond natural limitations. Bram Stoker’s “Dracula,” published in 1897, introduced readers to the iconic vampire Count Dracula and established many of the tropes associated with vampire lore. Immortality, sexuality, and the conflict between reason and the supernatural are some of the topics that are explored in the novel.

Prose and Essays

The prose and essays of the Romantic Era were distinguished by a rich tapestry of political and philosophical writings that captured the intellectual fervor of the time. The works of authors like Thomas De Quincey and William Hazlitt, who provided profound insights into the intellectual and political currents of their period, made a substantial contribution to this genre.

Read More: John Keats as a romantic poet

Thomas De Quincey is most known for his autobiographical work “Confessions of an English Opium-Eater,” in which he explored the nature of consciousness, dreams, and the human mind in addition to revealing his struggles with addiction. The essays of De Quincey were prime examples of Romanticism ‘s preoccupation with the inner workings of the human soul. The prolific essayist William Hazlitt, on the other hand, wrote essays like “Table-Talk” and “The Spirit of the Age,” which offered scathing comments on the literary figures and cultural trends of the day. Hazlitt became a recognized figure in both literary and political circles due to his essays which were distinguished by their eloquence and impassioned engagement with the events of the day.

Key Themes and Characteristics

The Romantic Period’s focus on individualism and the unrestrained power of the human imagination was one of its most important and enduring literary themes. Romantic authors fought for the idea that every person has a special inner world of emotions, creativity, and imagination that should be honored and expressed.

Romantic literature frequently explored the complexity of love, passion, sorrow, and wonder by delving into the depths of human emotions. John Keats’ poetry , for example, is a prime example of the Romantic movement’s preoccupation with the depth of human emotion. The Romantic confidence in the capacity of the individual imagination to handle life’s difficulties was typified by Keats’ discovery of the “negative capability,” the capacity to embrace doubt and uncertainty.

Read More: John Keats concept of negative capability

The Romantics also praised the power of unrestrained imagination and creativity as transformational forces that could shape the world and inspire social reform. For instance, William Blake’s poetry has a visionary aspect and envisioned a universe in which the human mind might go beyond the bounds of the real world.

Idealization of Nature

The Romantic Era was characterized by a deep and idealized relationship to nature, with poets and writers of the time praising nature as a source of creativity, consolation, and spiritual rejuvenation. This idealization of nature was a powerful response to the era’s rapid urbanization and industrialization.

Nature as a source of inspiration and solace: Romantic authors found in nature an endless fountain of inspiration for their imagination. They were inspired by the beauty, wonder, and amazement of the natural world. Poets like William Wordsworth saw nature as a living thing with profound significance rather than merely a picturesque backdrop. His well-known poem “Lines Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey” examines the healing potential of nature and how it might help people feel more connected to a higher, more transcendent reality. Similar to this, Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” investigates the spiritual aspects of nature by using the natural world as a setting for ethical and metaphysical exploration.

Rebellion Against Convention

The romantic era witnessed authors and artists resist against convention by criticizing society norms and institutions while promoting nonconformity and artistic independence.

Critique of societal norms and institutions: Romantics had an extremely critical view of the institutions and societal norms of their time. They questioned established religion’s restrictions, rigid social systems, and restrictions on personal freedom. For instance, Lord Byron’s poem “Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage” reflected a mood of discontent with the existing quo by expressing a sense of disappointment with the social and political order. The Romantics frequently disagreed with the established systems of society and expressed their dissatisfaction at the limitations imposed on free speech and creativity.

Percy Bysshe Shelley’s writings exhibit this attitude of defiance against tradition, notably in his poem “Ode to the West Wind,” in which he yearns for the wind’s ability to “Make me thy Lyre, even as the forests are.” The Romantic ideal of a more emancipated and harmonious existence is reflected in Shelley’s demand for a peaceful coexistence with nature’s powers.

Notable Figures of the Romantic Period

William Wordsworth is often regarded as one of the foundational figures of the Romantic movement. His poems emphasized the importance of individual experience and emotions in artistic creation while praising the splendor and strength of nature. His work on the “Lyrical Ballads” with Samuel Taylor Coleridge is regarded as a turning point in Romantic literature, and his poem “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud” continues to be one of the most celebrated examples of the Romantic idealization of nature.

Wordsworth’s close friend and fellow poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge is renowned for his inventive and lyrical poetry. A masterwork of Romantic literature, his poem “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” explores themes of guilt, atonement, and the supernatural. Coleridge’s writings also explored the fields of philosophy and literary criticism, significantly enhancing the Romantic Era’s intellectual landscape.

Lord Byron was a well-known poet and leader of the Romantic movement. Byron, who was famous for his audacious and ferocious poems, frequently explored themes of love, revolt, and independence. Both his narrative poem “Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage” and his dramatic poem “Manfred” demonstrate his connection with Romantic ideals of individual independence and criticism of social norms.

John Keats had a profound impact on Romantic poetry despite having a brief life. His odes, such as “Ode to a Nightingale” and “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” are praised for their examination of beauty, death, and the sublime force of art.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, the Romantic Period in English literature is seen as a transformative and significant period that had a profound impact on both the literary world and the larger cultural consciousness. The writings of renowned figures like Wordsworth, Coleridge , Shelley, Byron, and Keats during this time were characterized by the flourishing of important topics like the celebration of individualism and imagination, the idealization of nature, revolt against convention, and the search for personal independence. The legacy of the Romantic Era stands as a tribute to the enduring human spirit, the limitless power of the imagination, and the ageless pursuit of freedom and self-expression. It is a significant and cherished chapter in the ever-evolving history of English literature and culture because its themes and values are still relevant in modern literature and art.

- The use of irony in Austen’s Pride and Prejudice

- Women Characters in Pride and Prejudice

- The Monk in “The Canterbury Tales”

- Charles Lamb as an essayist

- Henrik Ibsen as a dramatist

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

200, 300, 350, & 400 Word Essay on Romanticism with Examples in English

Table of Contents

200 Words Argumentative Essay on Romanticism in English

Romanticism is a complex and multifaceted movement that has lasting impacts on literature and art worldwide. It is a movement that began in the late 18th century and continued into the 19th century. It is characterized by a focus on emotions, individualism, and nature. It was a reaction to the Enlightenment and neoclassical ideals of rationality and order.

Romanticism was a reaction to the Industrial Revolution and its effects on society. It was a celebration of the individual and a rejection of mechanization and commercialization. Romanticism saw nature as a refuge from modern artificiality and idealized the rural and the wilderness. Nature was seen as a source of inspiration, healing, and solace.

Romanticism also celebrated individualism and imagination. It encouraged people to explore their own feelings and emotions and express them creatively. It rejected the Enlightenment’s emphasis on reason and order, and instead embraced emotion and creativity. Romanticism also emphasized the power of the imagination to create new realities and shape the world.

Romanticism was a revolutionary and conservative movement. It was revolutionary in its rejection of traditional values and embrace of individualism and imagination. At the same time, it was conservative in its celebration of nature and rejection of the Industrial Revolution.

Romanticism profoundly affected literature and art. It is responsible for some of the greatest Romanticism literature works, such as William Wordsworth, Mary Shelley, and Lord Byron. It also had a major influence on art development, with painters such as Caspar David Friedrich and J.M.W. Turner creating works that embraced romantic ideals of emotion, nature, and individualism.

Romanticism was a movement of remarkable complexity and diversity. It celebrated individualism and imagination, rejected modern mechanization, and embraced nature. It was a movement that had a lasting impact on literature and art and continues to influence our worldview today.

300 Words Descriptive Essay on Romanticism in English

Romanticism was a major literary, artistic, and philosophical movement that began in the late 18th century and lasted until the mid-19th century. It was a period of intense creativity and imagination. It was characterized by a focus on personal expression and emotion, a celebration of nature, and a belief in the power of the individual.

Romanticism was a reaction to the rationalism of the Enlightenment. Instead of relying on reason and logic, Romanticism embraced emotion, intuition, and imagination. It was a celebration of individual and personal expression. Writers, poets, and artists were encouraged to explore their innermost feelings and express them freely.

Romanticism also celebrated nature. The Romantics believed that nature was a source of beauty and inspiration, and they sought to capture its beauty in their works. They wrote about nature in a passionate and spiritual way, expressing their awe and reverence for the natural world.

Romanticism also believed in the individual’s power. Rather than accepting the status quo, the Romantics sought to challenge society’s norms and create their own paths. They believed in the power of the individual to make a difference and shape the world.

Romanticism influenced literature, art, and philosophy. Writers like Wordsworth, Shelley, and Keats utilized the romantic style to explore their innermost feelings and express their love for nature. Artists like Turner and Constable used the same style to capture the natural world’s beauty. Philosophers like Rousseau and Schiller used the romantic style to express their ideas about the power of the individual and the importance of personal expression.

Romanticism has lasting effects on the world. Its focus on emotion, imagination, and nature has inspired generations of writers, artists, and philosophers. Its celebration of the individual is a source of hope and strength for those who challenge the status quo. Romanticism has been a powerful force in shaping the world, and it will continue to be a source of inspiration for many years to come.

350 Words Expository Essay on Romanticism in English

Romanticism is an artistic and intellectual movement that began in the late 18th century and has had lasting impacts on literature, art, and culture. It was a reaction to the Enlightenment, which saw reason and science as the only valid forms of knowledge. The Romantics sought to focus on emotion, passion, and intuition as valid forms of knowledge and celebrate the power of the individual.

Romanticism emphasizes emotion, imagination, and individualism. It is associated with a deep appreciation for nature and a belief in the power of the individual to create art and beauty. It was a reaction to the Enlightenment’s rationalism, which sought to explain the natural world through science and reason.

Romanticism is often associated with the arts, particularly literature and music. Writers such as William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge were some of the most influential figures in the Romantic era. Their poetry is still widely read and studied today. Similarly, composers such as Ludwig van Beethoven and Franz Schubert wrote works profoundly influenced by the Romantic spirit.

Romanticism also had a profound effect on visual art, with painters such as Eugene Delacroix and Caspar David Friedrich creating works inspired by Romantic ideals. These works often featured nature scenes and sought to evoke awe and wonder.

Romanticism is also associated with social and political movements, such as the French Revolution and slavery abolition. The Romantics saw these movements as a sign of hope and progress and sought to contribute to them through their art and writing.

In conclusion, Romanticism was a movement that had a profound impact on the arts, literature, and culture. It was a reaction to the Enlightenment and its focus on reason and science and sought to emphasize emotion, imagination, and individualism. The works of Romantic writers, painters, and musicians are still widely read and studied today, and their influence can be seen in many aspects of modern culture.

400 Words Persuasive Essay on Romanticism in English

Romanticism is a movement that deeply influences literature, music, and art throughout the centuries. It is an aesthetic sensibility that emphasizes the beauty and power of emotion, imagination, and nature. It is a passionate, emotive, and revolutionary style of art and expression.

Romanticism is a vital movement to understand to appreciate the literature, music, and art of the period. It is a style of writing characterized by personal experience and emotion. It is a reaction to the Enlightenment’s rationalism and the emphasis on reason and logic in the period’s work. Romanticism is a rebellion against the limits of the established order and a celebration of individualism and the potential of the human spirit.

Romanticism also emphasizes nature’s beauty and power. Nature is a source of inspiration and healing. This idea of nature as a source of solace and comfort can be observed in Romantic poets such as William Wordsworth and John Keats. Nature is seen as a reflection of the divine and a source of spiritual renewal.

Romanticism also focuses on the supernatural and the spiritual. It is an aesthetic that emphasizes the idea of the sublime, which is an experience of awe and wonder in the face of the infinite. This idea of the sublime can be seen in the work of Romantic painters such as Caspar David Friedrich and J.M.W. Turner.

Romanticism is an aesthetic sensibility that emphasizes emotion, imagination, and nature. It is a passionate, emotive, and revolutionary style of art and expression. It is a vital movement to understand to appreciate the period’s literature, music, and art. It is a rebellion against the limits of the established order and a celebration of individualism and the potential of the human spirit.

It is a source of solace, comfort, and spiritual renewal. It is an aesthetic that emphasizes the sublime, and it is an experience of awe and wonder in the face of the infinite. Romanticism is a movement that has deeply influenced literature, music, and art throughout the centuries, and it is still relevant today.

Romanticism and Art Characteristics

Romanticism was an artistic, literary, and intellectual movement that emerged in the late 18th century and reached its peak during the 19th century. It was a reaction to the Enlightenment’s rationalism and order, emphasizing emotion, individualism, and nature. Romanticism greatly influenced various art forms, including painting, literature, music, and sculpture. Here are some key characteristics of Romanticism in art:

- Emotion and Expression: Romantic artists sought to evoke deep emotions and feelings through their work. They aimed to move the viewer or audience emotionally, often focusing on themes such as love, passion, awe, fear, and nostalgia.

- Individualism: Romantic artists celebrated the individual and emphasized the uniqueness of each person’s experiences and emotions. They often depicted heroic figures, outcasts, or individuals in moments of intense personal contemplation.

- Nature: Nature played a significant role in Romantic art. Artists were fascinated by the beauty and power of the natural world, portraying landscapes, storms, mountains, and wild environments to evoke a sense of the sublime and the awe-inspiring.

- Imagination and Fantasy: Romantic artists embraced the power of imagination and fantasy. They explored dreamlike and surreal scenes, mythological themes, and supernatural elements to create an otherworldly atmosphere.

- Medievalism and Nostalgia: Many Romantic artists drew inspiration from medieval art and literature, seeing it as a time of heroism and chivalry. This longing for the past and a sense of nostalgia can be seen in their works.

- Nationalism and Patriotism: In a time of political and social upheaval, Romantic artists often expressed a strong sense of national identity and pride in their works. They celebrated their native cultures, folklore, and history.

- Exoticism: As travel and exploration expanded during the 19th century, Romantic artists became intrigued by foreign lands and cultures. This fascination with the exotic is evident in some of their works.

- Symbolism and Allegory: Romantic artists frequently used symbols and allegorical elements to convey deeper meanings and hidden messages in their artworks.

- Introspection and the Sublime: The Romantic movement encouraged introspection and contemplation of the human condition. They explored themes related to the human psyche, the sublime, and the vastness of the universe.

- Emotional Intensity and Drama: Romantic artists often depicted dramatic and emotionally charged scenes, creating a sense of tension and intensity in their works.

Notable Romantic artists include J.M.W. Turner, Caspar David Friedrich, Francisco Goya, Eugène Delacroix, and William Blake. These artists, along with many others, left a profound impact on art development during the Romantic period.

Romanticism Examples

Certainly! Here are some notable examples of Romanticism in various art forms:

- “Wanderer above the Sea of Fog” by Caspar David Friedrich: This iconic painting portrays a lone figure standing on a rocky precipice, gazing into a misty landscape, symbolizing the Romantic fascination with nature’s vastness and the individual’s contemplation.

- “Liberty Leading the People” by Eugène Delacroix: This painting depicts a powerful and allegorical figure of Liberty leading the people during the July Revolution of 1830 in France. It represents the Romantic themes of liberty, nationalism, and political upheaval.

- “Frankenstein” by Mary Shelley: This Gothic novel, published in 1818, explores themes of science, creation, and the consequences of playing god, while also delving into the complexities of human emotions and the darker aspects of human nature.

- “Wuthering Heights” by Emily Brontë: A classic novel known for its passionate and intense depiction of love and revenge, set against the backdrop of the desolate and wild Yorkshire moors.

- “Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125” (commonly known as “Choral Symphony”) by Ludwig van Beethoven: This monumental symphony is known for its final movement, featuring the “Ode to Joy,” expressing the ideals of universal brotherhood and joy, reflecting the Romantic emphasis on emotions and humanity.

- “Nocturnes” by Frédéric Chopin: Chopin’s compositions, particularly his Nocturnes, are famous for their lyrical, emotional, and introspective qualities, capturing the essence of Romanticism in music.

- “Ode to a Nightingale” by John Keats: This poem explores themes of mortality, escape, and the beauty of nature, showcasing the Romantic fascination with the natural world and the expression of intense emotions.

- “The Raven” by Edgar Allan Poe: This Gothic poem is a haunting exploration of grief, loss, and the macabre, illustrating the darker side of Romanticism.

These examples provide a glimpse into Romanticism’s diversity and richness across different art forms. Each contributes to the movement’s lasting impact on the 19th-century cultural and artistic landscape.

Why is it called the Romantic period?

The term “Romantic period” or “Romanticism” refers to the artistic, literary, and intellectual movement that emerged in the late 18th century and reached its peak during the 19th century. The movement was given this name because of its association with the concept of “romance,” which, in this context, doesn’t refer to love stories as we commonly understand it today.

The word “romance” in this context has its roots in ancient literature, where “romances” were tales of heroism, chivalry, and adventure. Medieval romances focused on individual experiences, emotions, and wonderment. The Romantic movement drew inspiration from these medieval romances and embraced similar themes. However, it expanded them to include a broader range of emotions and experiences.

During the Romantic period, artists, writers, and intellectuals sought to break away from the rationalism and order of the Enlightenment era that came before it. They emphasized the importance of emotion, imagination, individualism, and nature in contrast to the Enlightenment’s focus on reason, science, and societal conventions.

As the movement gained momentum, critics and scholars called it “Romanticism” to capture its association with romance, individualism, and emotional expression. The term “Romantic period” has since become the standard way to describe this influential artistic and intellectual movement that left a profound impact on Western culture and shaped literature, art, and philosophy for years to come.

Romanticism Summary

Romanticism was a cultural, artistic, and intellectual movement that emerged in the late 18th century and flourished during the 19th century. It was a reaction to the Enlightenment’s rationalism and order, emphasizing emotion, individualism, nature, and imagination. Here’s a summary of Romanticism:

- Emphasis on Emotion: Romanticism celebrated intense emotions and emotional expression. Artists, writers, and musicians sought to evoke deep feelings and moved away from the restrained and rational approach of the previous era.

- Individualism: Romanticism celebrated the uniqueness and importance of the individual. It focused on the inner world of the human psyche and the expression of personal experiences and emotions.

- Nature as a Source of Inspiration: Nature played a significant role in Romantic art and literature. Artists were captivated by the beauty, power, and mystery of the natural world, portraying landscapes and elements of nature to evoke a sense of awe and the sublime.

- Imagination and Fantasy: Romantic artists embraced the power of imagination and explored fantastical and dreamlike elements in their works. They drew inspiration from myths, legends, and the supernatural, creating otherworldly and imaginative atmospheres.

- Nationalism and Patriotism: In a time of political and social change, Romanticism fostered a sense of national identity and pride. Artists celebrated their native cultures, folklore, and history.

- Medievalism and Nostalgia: Romantic artists looked back to the medieval era with a sense of nostalgia, seeing it as a time of heroism, chivalry, and simpler, more authentic values.

- Symbolism and Allegory: Romantic artists often used symbols and allegorical elements to convey deeper meanings and messages in their artworks.

- Rejection of Industrialization: With the advent of the Industrial Revolution, many Romantic thinkers criticized the negative impact of industrialization on nature, society, and the human spirit.

- Contemplation of the Sublime: Romanticism explored the concept of the sublime—the overwhelming and awe-inspiring aspects of nature and human experience, which could be both beautiful and terrifying.

- Interest in the Exotic: As travel expanded, Romantic artists were intrigued by foreign lands and cultures, and this fascination with the exotic is evident in their works.

The Romantic period produced some of the most influential and enduring works in literature, art, music, and philosophy. It challenged conventional norms and encouraged a more profound exploration of the human experience. This left a lasting impact on Western culture and artistic movements.

Essay on My Mother: From 100 to 500 Words

200, 300, 350, 400, & 450 Word Essay on Uselessness of Science in English & Hindi

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

38 Literature and Philosophy