Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.4 The Effects of the Internet and Globalization on Popular Culture and Interpersonal Communication

Learning objectives.

- Describe the effects of globalization on culture.

- Identify the possible effects of news migrating to the Internet.

- Define the Internet paradox.

It’s in the name: World Wide Web . The Internet has broken down communication barriers between cultures in a way that could only be dreamed of in earlier generations. Now, almost any news service across the globe can be accessed on the Internet and, with the various translation services available (like Babelfish and Google Translate), be relatively understandable. In addition to the spread of American culture throughout the world, smaller countries are now able to cheaply export culture, news, entertainment, and even propaganda.

The Internet has been a key factor in driving globalization in recent years. Many jobs can now be outsourced entirely via the Internet. Teams of software programmers in India can have a website up and running in very little time, for far less money than it would take to hire American counterparts. Communicating with these teams is now as simple as sending e-mails and instant messages back and forth, and often the most difficult aspect of setting up an international video conference online is figuring out the time difference. Especially for electronic services such as software, outsourcing over the Internet has greatly reduced the cost to develop a professionally coded site.

Electronic Media and the Globalization of Culture

The increase of globalization has been an economic force throughout the last century, but economic interdependency is not its only by-product. At its core, globalization is the lowering of economic and cultural impediments to communication between countries all over the globe. Globalization in the sphere of culture and communication can take the form of access to foreign newspapers (without the difficulty of procuring a printed copy) or, conversely, the ability of people living in previously closed countries to communicate experiences to the outside world relatively cheaply.

TV, especially satellite TV, has been one of the primary ways for American entertainment to reach foreign shores. This trend has been going on for some time now, for example, with the launch of MTV Arabia (Arango, 2008). American popular culture is, and has been, a crucial export.

At the Eisenhower Fellowship Conference in Singapore in 2005, U.S. ambassador Frank Lavin gave a defense of American culture that differed somewhat from previous arguments. It would not be all Starbucks, MTV, or Baywatch , he said, because American culture is more diverse than that. Instead, he said that “America is a nation of immigrants,” and asked, “When Mel Gibson or Jackie Chan come to the United States to produce a movie, whose culture is being exported (Lavin, 2005)?” This idea of a truly globalized culture—one in which content can be distributed as easily as it can be received—now has the potential to be realized through the Internet. While some political and social barriers still remain, from a technological standpoint there is nothing to stop the two-way flow of information and culture across the globe.

China, Globalization, and the Internet

The scarcity of artistic resources, the time lag of transmission to a foreign country, and censorship by the host government are a few of the possible impediments to transmission of entertainment and culture. China provides a valuable example of the ways the Internet has helped to overcome (or highlight) all three of these hurdles.

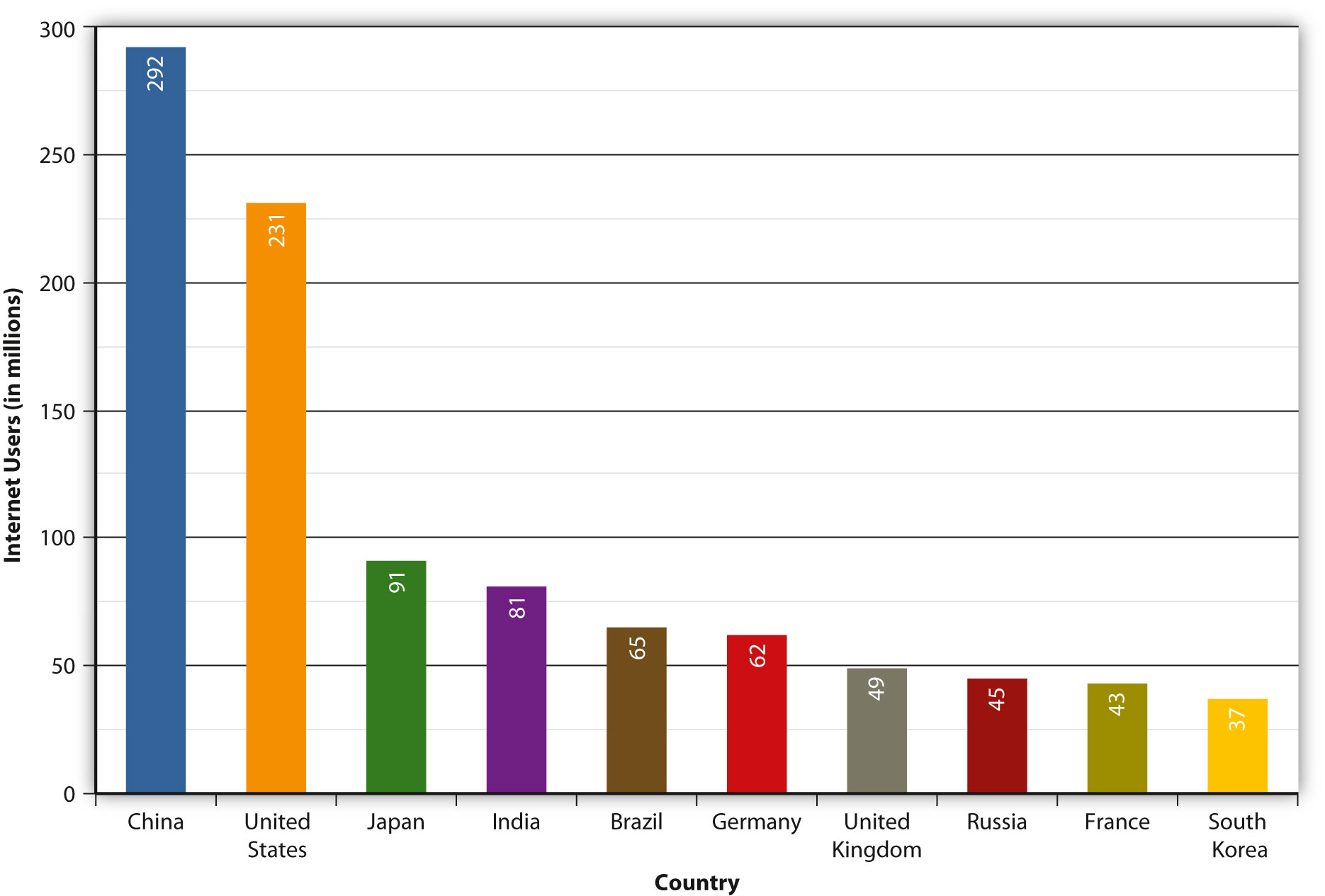

China, as the world’s most populous country and one of its leading economic powers, has considerable clout when it comes to the Internet. In addition, the country is ruled by a single political party that uses censorship extensively in an effort to maintain control. Because the Internet is an open resource by nature, and because China is an extremely well-connected country—with 22.5 percent (roughly 300 million people, or the population of the entire United States) of the country online as of 2008 (Google, 2010)—China has been a case study in how the Internet makes resistance to globalization increasingly difficult.

Figure 11.7

China has more Internet users than any other country.

On January 21, 2010, Hillary Clinton gave a speech in front of the Newseum in Washington, DC, where she said, “We stand for a single Internet where all of humanity has equal access to knowledge and ideas (Ryan & Halper, 2010).” That same month, Google decided it would stop censoring search results on Google.cn, its Chinese-language search engine, as a result of a serious cyber-attack on the company originating in China. In addition, Google stated that if an agreement with the Chinese government could not be reached over the censorship of search results, Google would pull out of China completely. Because Google has complied (albeit uneasily) with the Chinese government in the past, this change in policy was a major reversal.

Withdrawing from one of the largest expanding markets in the world is shocking coming from a company that has been aggressively expanding into foreign markets. This move highlights the fundamental tension between China’s censorship policy and Google’s core values. Google’s company motto, “Don’t be evil,” had long been at odds with its decision to censor search results in China. Google’s compliance with the Chinese government did not help it make inroads into the Chinese Internet search market—although Google held about a quarter of the market in China, most of the search traffic went to the tightly controlled Chinese search engine Baidu. However, Google’s departure from China would be a blow to antigovernment forces in the country. Since Baidu has a closer relationship with the Chinese government, political dissidents tend to use Google’s Gmail, which uses encrypted servers based in the United States. Google’s threat to withdraw from China raises the possibility that globalization could indeed hit roadblocks due to the ways that foreign governments may choose to censor the Internet.

New Media: Internet Convergence and American Society

One only needs to go to CNN’s official Twitter feed and begin to click random faces in the “Following” column to see the effect of media convergence through the Internet. Hundreds of different options abound, many of them individual journalists’ Twitter feeds, and many of those following other journalists. Considering CNN’s motto, “The most trusted name in network news,” its presence on Twitter might seem at odds with providing in-depth, reliable coverage. After all, how in-depth can 140 characters get?

The truth is that many of these traditional media outlets use Twitter not as a communication tool in itself, but as a way to allow viewers to aggregate a large amount of information they may have missed. Instead of visiting multiple home pages to see the day’s top stories from multiple viewpoints, Twitter users only have to check their own Twitter pages to get updates from all the organizations they “follow.” Media conglomerates then use Twitter as part of an overall integration of media outlets; the Twitter feed is there to support the news content, not to report the content itself.

Internet-Only Sources

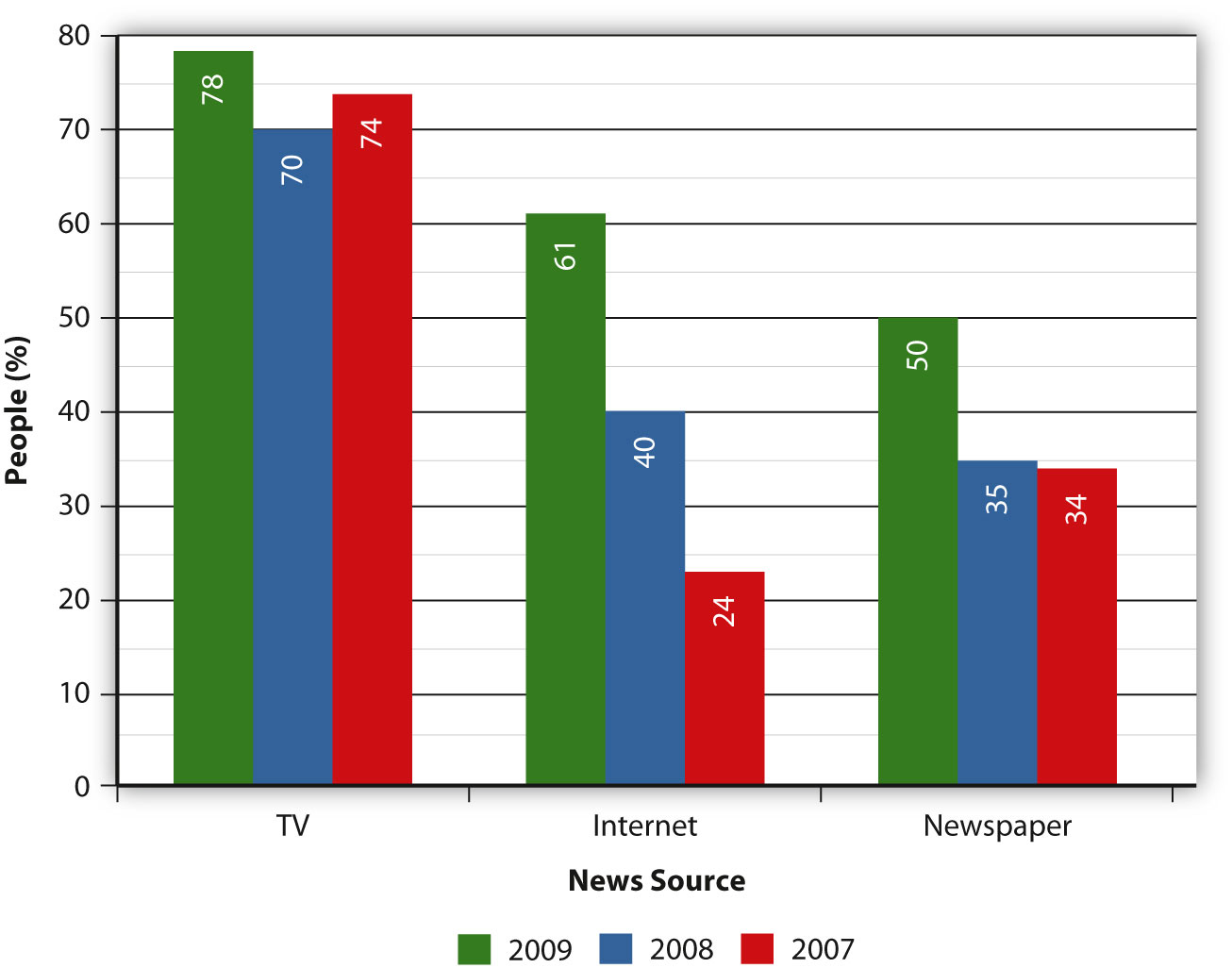

The threshold was crossed in 2008: The Internet overtook print media as a primary source of information for national and international news in the U.S. Television is still far in the lead, but especially among younger demographics, the Internet is quickly catching up as a way to learn about the day’s news. With 40 percent of the public receiving their news from the Internet (see Figure 11.8 ) (Pew Research Center for the People, 2008), media outlets have been scrambling to set up large presences on the web. Yet one of the most remarkable shifts has been in the establishment of online-only news sources.

Figure 11.8

Americans now receive more national and international news from the Internet than they do from newspapers.

The conventional argument claims that the anonymity and the echo chamber of the Internet undermine worthwhile news reporting, especially for topics that are expensive to report on. The ability of large news organizations to put reporters in the field is one of their most important contributions and (because of its cost) is often one of the first things to be cut back during times of budget problems. However, as the Internet has become a primary news source for more and more people, new media outlets—publications existing entirely online—have begun to appear.

In 2006, two reporters for the Washington Post , John F. Harris and Jim VandeHei, left the newspaper to start a politically centered website called Politico. Rather than simply repeating the day’s news in a blog, they were determined to start a journalistically viable news organization on the web. Four years later, the site has over 6,000,000 unique monthly visitors and about a hundred staff members, and there is now a Politico reporter on almost every White House trip (Wolff, 2009).

Far from being a collection of amateurs trying to make it big on the Internet, Politico’s senior White House correspondent is Mike Allen, who previously wrote for The New York Times , Washington Post , and Time . His daily Playbook column appears at around 7 a.m. each morning and is read by much of the politically centered media. The different ways that Politico reaches out to its supporters—blogs, Twitter feeds, regular news articles, and now even a print edition—show how media convergence has even occurred within the Internet itself. The interactive nature of its services and the active comment boards on the site also show how the media have become a two-way street: more of a public forum than a straight news service.

“Live” From New York …

Top-notch political content is not the only medium moving to the Internet, however. Saturday Night Live ( SNL ) has built an entire entertainment model around its broadcast time slot. Every weekend, around 11:40 p.m. on Saturday, someone interrupts a skit, turns toward the camera, shouts “Live from New York, it’s Saturday Night!” and the band starts playing. Yet the show’s sketch comedy style also seems to lend itself to the watch-anytime convenience of the Internet. In fact, the online TV service Hulu carries a full eight episodes of SNL at any given time, with regular 3.5-minute commercial breaks replaced by Hulu-specific minute-long advertisements. The time listed for an SNL episode on Hulu is just over an hour—a full half-hour less than the time it takes to watch it live on Saturday night.

Hulu calls its product “online premium video,” primarily because of its desire to attract not the YouTube amateur, but rather a partnership of large media organizations. Although many networks, like NBC and Comedy Central, stream video on their websites, Hulu builds its business by offering a legal way to see all these shows on the same site; a user can switch from South Park to SNL with a single click, rather than having to move to a different website.

Premium Online Video Content

Hulu’s success points to a high demand among Internet users for a wide variety of content collected and packaged in one easy-to-use interface. Hulu was rated the Website of the Year by the Associated Press (Coyle, 2008) and even received an Emmy nomination for a commercial featuring Alec Baldwin and Tina Fey, the stars of the NBC comedy 30 Rock (Neil, 2009). Hulu’s success has not been the product of the usual dot-com underdog startup, however. Its two parent companies, News Corporation and NBC Universal, are two of the world’s media giants. In many ways, this was a logical step for these companies to take after fighting online video for so long. In December 2005, the video “Lazy Sunday,” an SNL digital short featuring Andy Samberg and Chris Parnell, went viral with over 5,000,000 views on YouTube before February 2006, when NBC demanded that YouTube take down the video (Biggs, 2006). NBC later posted the video on Hulu, where it could sell advertising for it.

Hulu allows users to break out of programming models controlled by broadcast and cable TV providers and choose freely what shows to watch and when to watch them. This seems to work especially well for cult programs that are no longer available on TV. In 2008, the show Arrested Development , which was canceled in 2006 after repeated time slot shifts, was Hulu’s second-most-popular program.

Hulu certainly seems to have leveled the playing field for some shows that have had difficulty finding an audience through traditional means. 30 Rock , much like Arrested Development , suffered from a lack of viewers in its early years. In 2008, New York Magazine described the show as a “fragile suckling that critics coddle but that America never quite warms up to (Sternbergh, 2008).” However, even as 30 Rock shifted time slots mid-season, its viewer base continued to grow through the NBC partner of Hulu. The nontraditional media approach of NBC’s programming culminated in October 2008, when NBC decided to launch the new season of 30 Rock on Hulu a full week before it was broadcast over the airwaves (Wortham, 2008). Hulu’s strategy of providing premium online content seems to have paid off: As of March 2011, Hulu provided 143,673,000 viewing sessions to more than 27 million unique visitors, according to Nielsen (ComScore, 2011).

Unlike other “premium” services, Hulu does not charge for its content; rather, the word premium in its slogan seems to imply that it could charge for content if it wanted to. Other platforms, like Sony’s PlayStation 3, block Hulu for this very reason—Sony’s online store sells the products that Hulu gives away for free. However, Hulu has been considering moving to a paid subscription model that would allow users to access its entire back catalog of shows. Like many other fledgling web enterprises, Hulu seeks to create reliable revenue streams to avoid the fate of many of the companies that folded during the dot-com crash (Sandoval, 2009).

Like Politico, Hulu has packaged professionally produced content into an on-demand web service that can be used without the normal constraints of traditional media. Just as users can comment on Politico articles (and now, on most newspapers’ articles), they can rate Hulu videos, and Hulu will take this into account. Even when users do not produce the content themselves, they still want this same “two-way street” service.

Table 11.2 Top 10 U.S. Online Video Brands, Home and Work

The Role of the Internet in Social Alienation

In the early years, the Internet was stigmatized as a tool for introverts to avoid “real” social interactions, thereby increasing their alienation from society. Yet the Internet was also seen as the potentially great connecting force between cultures all over the world. The idea that something that allowed communication across the globe could breed social alienation seemed counterintuitive. The American Psychological Association (APA) coined this concept the “ Internet paradox .”

Studies like the APA’s “Internet paradox: A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being (Kraut, et. al., 1998)?” which came out in 1998, suggested that teens who spent lots of time on the Internet showed much greater rates of self-reported loneliness and other signs of psychological distress. Even though the Internet had been around for a while by 1998, the increasing concern among parents was that teenagers were spending all their time in chat rooms and online. The fact was that teenagers spent much more time on the Internet than adults, due to their increased free time, curiosity, and familiarity with technology.

However, this did not necessarily mean that “kids these days” were antisocial or that the Internet caused depression and loneliness. In his critical analysis “Deconstructing the Internet Paradox,” computer scientist, writer, and PhD recipient from Carnegie Mellon University Joseph M. Newcomer points out that the APA study did not include a control group to adjust for what may be normal “lonely” feelings in teenagers. Again, he suggests that “involvement in any new, self-absorbing activity which has opportunity for failure can increase depression,” seeing Internet use as just another time-consuming hobby, much like learning a musical instrument or playing chess (Newcomer, 2000).

The general concept that teenagers were spending all their time in chat rooms and online forums instead of hanging out with flesh-and-blood friends was not especially new; the same thing had generally been thought of the computer hobbyists who pioneered the esoteric Usenet. However, the concerns were amplified when a wider range of young people began using the Internet, and the trend was especially strong in the younger demographics.

The “Internet Paradox” and Facebook

As they developed, it became quickly apparent that the Internet generation did not suffer from perpetual loneliness as a rule. After all, the generation that was raised on instant messaging invented Facebook and still makes up most of Facebook’s audience. As detailed earlier in the chapter, Facebook began as a service limited to college students—a requirement that practically excluded older participants. As a social tool and as a reflection of the way younger people now connect with each other over the Internet, Facebook has provided a comprehensive model for the Internet’s effect on social skills and especially on education.

A study by the Michigan State University Department of Telecommunication, Information Studies, and Media has shown that college-age Facebook users connect with offline friends twice as often as they connect with purely online “friends (Ellison, et. al., 2007).” In fact, 90 percent of the participants in the study reported that high school friends, classmates, and other friends were the top three groups that their Facebook profiles were directed toward.

In 2007, when this study took place, one of Facebook’s most remarkable tools for studying the ways that young people connect was its “networks” feature. Originally, a Facebook user’s network consisted of all the people at his or her college e-mail domain: the “mycollege” portion of “[email protected].” The MSU study, performed in April 2006, just 6 months after Facebook opened its doors to high school students, found that first-year students met new people on Facebook 36 percent more often than seniors did. These freshmen, in April 2006, were not as active on Facebook as high schoolers (Facebook began allowing high schoolers on its site during these students’ first semester in school) (Rosen, 2005). The study concluded that they could “definitively state that there is a positive relationship between certain kinds of Facebook use and the maintenance and creation of social capital (Ellison, et. al., 2007).” In other words, even though the study cannot show whether Facebook use causes or results from social connections, it can say that Facebook plays both an important and a nondestructive role in the forming of social bonds.

Although this study provides a complete and balanced picture of the role that Facebook played for college students in early 2006, there have been many changes in Facebook’s design and in its popularity. In 2006, many of a user’s “friends” were from the same college, and the whole college network might be mapped as a “friend-of-a-friend” web. If users allowed all people within a single network access to their profiles, it would create a voluntary school-wide directory of students. Since a university e-mail address was required for signup, there was a certain level of trust. The results of this Facebook study, still relatively current in terms of showing the Internet’s effects on social capital, show that not only do social networking tools not lead to more isolation, but that they actually have become integral to some types of networking.

However, as Facebook began to grow and as high school and regional networks (such as “New York City” or “Ireland”) were incorporated, users’ networks of friends grew exponentially, and the networking feature became increasingly unwieldy for privacy purposes. In 2009, Facebook discontinued regional networks over concerns that networks consisting of millions of people were “no longer the best way for you to control your privacy (Zuckerberg, 2009).” Where privacy controls once consisted of allowing everyone at one’s college access to specific information, Facebook now allows only three levels: friends, friends of friends, and everyone.

Meetup.com : Meeting Up “IRL”

Of course, not everyone on teenagers’ online friends lists are actually their friends outside of the virtual world. In the parlance of the early days of the Internet, meeting up “IRL” (shorthand for “in real life”) was one of the main reasons that many people got online. This practice was often looked at with suspicion by those not familiar with it, especially because of the anonymity of the Internet. The fear among many was that children would go into chat rooms and agree to meet up in person with a total stranger, and that stranger would turn out to have less-than-friendly motives. This fear led to law enforcement officers posing as underage girls in chat rooms, agreeing to meet for sex with older men (after the men brought up the topic—the other way around could be considered entrapment), and then arresting the men at the agreed-upon meeting spot.

In recent years, however, the Internet has become a hub of activity for all sorts of people. In 2002, Scott Heiferman started Meetup.com based on the “simple idea of using the Internet to get people off the Internet (Heiferman, 2009).” The entire purpose of Meetup.com is not to foster global interaction and collaboration (as is the purpose of something like Usenet,) but rather to allow people to organize locally. There are Meetups for politics (popular during Barack Obama’s presidential campaign), for New Yorkers who own Boston terriers (Fairbanks, 2008), for vegan cooking, for board games, and for practically everything else. Essentially, the service (which charges a small fee to Meetup organizers) separates itself from other social networking sites by encouraging real-life interaction. Whereas a member of a Facebook group may never see or interact with fellow members, Meetup.com actually keeps track of the (self-reported) real-life activity of its groups—ideally, groups with more activity are more desirable to join. However much time these groups spend together on or off the Internet, one group of people undoubtedly has the upper hand when it comes to online interaction: World of Warcraft players.

World of Warcraft : Social Interaction Through Avatars

A writer for Time states the reasons for the massive popularity of online role-playing games quite well: “[My generation’s] assumptions were based on the idea that video games would never grow up. But no genre has worked harder to disprove that maxim than MMORPGs—Massively Multiplayer Online Games (Coates, 2007).” World of Warcraft (WoW , for short) is the most popular MMORPG of all time, with over 11 million subscriptions and counting. The game is inherently social; players must complete “quests” in order to advance in the game, and many of the quests are significantly easier with multiple people. Players often form small, four-to five-person groups in the beginning of the game, but by the end of the game these larger groups (called “raiding parties”) can reach up to 40 players.

In addition, WoW provides a highly developed social networking feature called “guilds.” Players create or join a guild, which they can then use to band with other guilds in order to complete some of the toughest quests. “But once you’ve got a posse, the social dynamic just makes the game more addictive and time-consuming,” writes Clive Thompson for Slate (Thompson, 2005). Although these guilds do occasionally meet up in real life, most of their time together is spent online for hours per day (which amounts to quite a bit of time together), and some of the guild leaders profess to seeing real-life improvements. Joi Ito, an Internet business and investment guru, joined WoW long after he had worked with some of the most successful Internet companies; he says he “definitely (Pinckard, 2006)” learned new lessons about leadership from playing the game. Writer Jane Pinckard, for video game blog 1UP , lists some of Ito’s favorite activities as “looking after newbs [lower-level players] and pleasing the veterans,” which he calls a “delicate balancing act (Pinckard, 2006),” even for an ex-CEO.

Figure 11.9

Guilds often go on “raiding parties”—just one of the many semisocial activities in World of Warcraft .

monsieur paradis – gathering in Kargath before a raid – CC BY-NC 2.0.

With over 12 million subscribers, WoW necessarily breaks the boundaries of previous MMORPGs. The social nature of the game has attracted unprecedented numbers of female players (although men still make up the vast majority of players), and its players cannot easily be pegged as antisocial video game addicts. On the contrary, they may even be called social video game players, judging from the general responses given by players as to why they enjoy the game. This type of play certainly points to a new way of online interaction that may continue to grow in coming years.

Social Interaction on the Internet Among Low-Income Groups

In 2006, the journal Developmental Psychology published a study looking at the educational benefits of the Internet for teenagers in low-income households. It found that “children who used the Internet more had higher grade point averages (GPA) after one year and higher scores after standardized tests of reading achievement after six months than did children who used it less,” and that continuing to use the Internet more as the study went on led to an even greater increase in GPA and standardized test scores in reading (there was no change in mathematics test scores) (Jackson, et. al., 2006).

One of the most interesting aspects of the study’s results is the suggestion that the academic benefits may exclude low-performing children in low-income households. The reason for this, the study suggests, is that children in low-income households likely have a social circle consisting of other children from low-income households who are also unlikely to be connected to the Internet. As a result, after 16 months of Internet usage, only 16 percent of the participants were using e-mail and only 25 percent were using instant messaging services. Another reason researchers suggested was that because “African-American culture is historically an ‘oral culture,’” and 83 percent of the participants were African American, the “impersonal nature of the Internet’s typical communication tools” may have led participants to continue to prefer face-to-face contact. In other words, social interaction on the Internet can only happen if your friends are also on the Internet.

The Way Forward: Communication, Convergence, and Corporations

On February 15, 2010, the firm Compete, which analyzes Internet traffic, reported that Facebook surpassed Google as the No. 1 site to drive traffic toward news and entertainment media on both Yahoo! and MSN (Ingram, 2010). This statistic is a strong indicator that social networks are quickly becoming one of the most effective ways for people to sift through the ever-increasing amount of information on the Internet. It also suggests that people are content to get their news the way they did before the Internet or most other forms of mass media were invented—by word of mouth.

Many companies now use the Internet to leverage word-of-mouth social networking. The expansion of corporations into Facebook has given the service a big publicity boost, which has no doubt contributed to the growth of its user base, which in turn helps the corporations that put marketing efforts into the service. Putting a corporation on Facebook is not without risk; any corporation posting on Facebook runs the risk of being commented on by over 500 million users, and of course there is no way to ensure that those users will say positive things about the corporation. Good or bad, communicating with corporations is now a two-way street.

Key Takeaways

- The Internet has made pop culture transmission a two-way street. The power to influence popular culture no longer lies with the relative few with control over traditional forms of mass media; it is now available to the great mass of people with access to the Internet. As a result, the cross-fertilization of pop culture from around the world has become a commonplace occurrence.

- The Internet’s key difference from traditional media is that it does not operate on a set intervallic time schedule. It is not “periodical” in the sense that it comes out in daily or weekly editions; it is always updated. As a result, many journalists file both “regular” news stories and blog posts that may be updated and that can come at varied intervals as necessary. This allows them to stay up-to-date with breaking news without necessarily sacrificing the next day’s more in-depth story.

- The “Internet paradox” is the hypothesis that although the Internet is a tool for communication, many teenagers who use the Internet lack social interaction and become antisocial and depressed. It has been largely disproved, especially since the Internet has grown so drastically. Many sites, such as Meetup.com or even Facebook, work to allow users to organize for offline events. Other services, like the video game World of Warcraft , serve as an alternate social world.

- Make a list of ways you interact with friends, either in person or on the Internet. Are there particular methods of communication that only exist in person?

- Are there methods that exist on the Internet that would be much more difficult to replicate in person?

- How do these disprove the “Internet paradox” and contribute to the globalization of culture?

- Pick a method of in-person communication and a method of Internet communication, and compare and contrast these using a Venn diagram.

Arango, Tim. “World Falls for American Media, Even as It Sours on America,” New York Times , November 30, 2008, http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/01/business/media/01soft.html .

Biggs, John. “A Video Clip Goes Viral, and a TV Network Wants to Control It,” New York Times , February 20, 2006, http://www.nytimes.com/2006/02/20/business/media/20youtube.html .

Coates, Ta-Nehisi Paul. “Confessions of a 30-Year-Old Gamer,” Time , January 12, 2007, http://www.time.com/time/arts/article/0,8599,1577502,00.html .

ComScore, “ComScore release March 2011 US Online Video Rankings,” April 12, 2011, http://www.comscore.com/Press_Events/Press_Releases/2011/4/ comScore_Releases_March_2011_U.S._Online_Video_Rankings .

Coyle, Jake. “On the Net: Hulu Is Web Site of the Year,” Seattle Times , December 19, 2008, http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/entertainment/2008539776_aponthenetsiteoftheyear.html .

Ellison, Nicole B. Charles Steinfield, and Cliff Lampe, “The Benefits of Facebook ‘Friends’: Social Capital and College Students’ Use of Online Social Network Sites,” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 14, no. 4 (2007).

Fairbanks, Amanda M. “Funny Thing Happened at the Dog Run,” New York Times , August 23, 2008, cse http://www.nytimes.com/2008/08/24/nyregion/24meetup.html .

Google, “Internet users as percentage of population: China,” February 19, 2010, http://www.google.com/publicdata?ds=wb-wdi&met=it_net_user_p2&idim=country: CHN&dl=en&hl=en&q=china+internet+users .

Heiferman, Scott. “The Pursuit of Community,” New York Times , September 5, 2009, cse http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/06/jobs/06boss.html .

Ingram, Mathew. “Facebook Driving More Traffic Than Google,” New York Times , February 15, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/external/gigaom/2010/02/15/15gigaom-facebook-driving-more-traffic-than-google-42970.html .

Jackson, Linda A. and others, “Does Home Internet Use Influence the Academic Performance of Low-Income Children?” Developmental Psychology 42, no. 3 (2006): 433–434.

Kraut, Robert and others, “Internet Paradox: A Social Technology That Reduces Social Involvement and Psychological Well-Being?” American Psychologist, September 1998, http://psycnet.apa.org/index.cfm?fa=buy.optionToBuy&id=1998-10886-001 .

Lavin, Frank. “‘Globalization and Culture’: Remarks by Ambassador Frank Lavin at the Eisenhower Fellowship Conference in Singapore,” U.S. Embassy in Singapore, June 28, 2005, http://singapore.usembassy.gov/062805.html .

Neil, Dan. “‘30 Rock’ Gets a Wink and a Nod From Two Emmy-Nominated Spots,” Los Angeles Times , July 21, 2009, http://articles.latimes.com/2009/jul/21/business/fi-ct-neil21 .

Newcomer, Joseph M. “Deconstructing the Internet Paradox,” Ubiquity , Association for Computing Machinery, April 2000, http://ubiquity.acm.org/article.cfm?id=334533 . (Originally published as an op-ed in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette , September 27, 1998.).

Pew Research Center for the People & the Press, “Internet Overtakes Newspapers as News Outlet,” December 23, 2008, http://people-press.org/report/479/internet-overtakes-newspapers-as-news-source .

Pinckard, Jane. “Is World of Warcraft the New Golf?” 1UP.com , February 8, 2006, http://www.1up.com/news/world-warcraft-golf .

Rosen, Ellen. “THE INTERNET; Facebook.com Goes to High School,” New York Times , October 16, 2005, http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C05EEDA173FF935A25753C1A9639C8B63&scp=5&sq=facebook&st=nyt .

Ryan, Johnny and Stefan Halper, “Google vs China: Capitalist Model, Virtual Wall,” OpenDemocracy, January 22, 2010, http://www.opendemocracy.net/johnny-ryan-stefan-halper/google-vs-china-capitalist-model-virtual-wall .

Sandoval, Greg. “More Signs Hulu Subscription Service Is Coming,” CNET , October 22, 2009, http://news.cnet.com/8301-31001_3-10381622-261.html .

Sternbergh, Adam. “‘The Office’ vs. ‘30 Rock’: Comedy Goes Back to Work,” New York Magazine , April 10, 2008, http://nymag.com/daily/entertainment/2008/04/the_office_vs_30_rock_comedy_g.html .

Thompson, Clive. “An Elf’s Progress: Finally, Online Role-Playing Games That Won’t Destroy Your Life,” Slate , March 7, 2005, http://www.slate.com/id/2114354 .

Wolff, Michael. “Politico’s Washington Coup,” Vanity Fair , August 2009, http://www.vanityfair.com/politics/features/2009/08/wolff200908 .

Wortham, Jenna. “Hulu Airs Season Premiere of 30 Rock a Week Early,” Wired , October 23, 2008, http://www.wired.com/underwire/2008/10/hulu-airs-seaso/ .

Zuckerberg, Mark. “An Open Letter from Facebook Founder Mark Zuckerberg,” Facebook, December 1, 2009, http://blog.facebook.com/blog.php?post=190423927130 .

Understanding Media and Culture Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Social Science Japan Journal

- About the Institute of Social Sciences at the University of Tokyo

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

Popular Culture, Globalization and Japan

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Shawn BENDER, Popular Culture, Globalization and Japan, Social Science Japan Journal , Volume 10, Issue 1, April 2007, Pages 146–149, https://doi.org/10.1093/ssjj/jym014

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The study of contemporary Japanese society over the past 20 years can be loosely divided into pre- and post-bubble periods. Before the bubble burst, studies tended to concentrate on sites of production, such as corporations, factories, schools and cities. As the economic threat posed by Japan receded after the collapse of the economic bubble in 1989, the academic focus on Japanese society gradually shifted to sites of consumption and performance. Anxiety over the ‘hard’ power of Japan's expanding gross national product gave way to a new appreciation for the ‘soft’ power of Japan's emergent ‘Gross National Cool’ ( McGray 2002). Whereas an earlier era of scholarship attempted to unlock the unique cultural patterns that made the Japanese ‘economic animals’ so formidable, studies in the post-bubble era emphasize the heterogeneity of Japanese society. This new scholarship embraces the products of Japan's dynamic popular culture, not just its traditional culture, as expressions of contemporary society. Instead of limiting the study of Japan to its territorial borders, researchers investigate the impact of economic and cultural globalization on Japan as well as Japan's significant cultural impact on the world.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1468-2680

- Print ISSN 1369-1465

- Copyright © 2024 University of Tokyo and Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 3. Culture

3.3. Culture as Innovation: Pop Culture, Subculture, Global Culture

In the introduction to this chapter, culture was defined as the source of the shared meanings through which people interpret and orient themselves to the world. While cultural practices are in some respects always a response to biological givens or to the structure of the socioeconomic formation, they are not determined by these factors. Culture is innovative. It expresses the human imagination in its capacity to go beyond what is given, to solve problems, to produce innovations — new objects, ideas, or ways of being introduced to culture for the first time. At the same time, people are born into cultures that pre-exist them and shape them. Languages, ways of thinking, ways of doing things, and artifacts are elements of culture people do not invent but inherit. They are ready-made forms of life that people fit themselves into. Culture can, therefore, also be restrictive, imposing ways of life, beliefs, and practices on people, and limiting the possibilities of what they can think and do. As Karl Marx (1852) said, “the tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.”

The next two sections of this chapter will examine aspects of culture which are innovative — high culture and popular culture, subcultures, and global culture — and aspects of culture which are restrictive — rationalization and consumerism.

High Culture and Popular Culture

Does a person prefer listening to opera or hip hop music? Do they like watching horse jumping or NASCAR? Do they read books of poetry or magazines about celebrities? In each of these choices, one type of entertainment is considered high culture and the other low culture. Sociologists use the term high culture to describe forms of cultural experience that are meant to cultivate and refine people’s sensibility: their ability to appreciate and respond to complex emotional, intellectual, or aesthetic influences. High cultural forms are characterized by formal complexity, eternal values, originality, and authenticity such as is provided by Beethoven’s string quartets, Picasso’s paintings, Sergei Diaghilev’s ballets, or James Joyce’s Ulysses . People often associate high culture with intellectualism, aesthetic taste, elitism, wealth, and prestige because it is not immediately accessible and requires cultivation or education to appreciate.

Pierre Bourdieu (1984) argues further that high culture is not only a symbol of cultural distinction, but a means of maintaining status and power distinctions through the transfer of cultural capital : the knowledge, skills, tastes, mannerisms, speaking style, posture, material possessions, credentials, etc. that a person acquires from their family and class background. Events considered high culture can be expensive and formal — attending a ballet, seeing a play, or listening to a live symphony performance — and the people who are in a position to appreciate these events are often those who have enjoyed the benefits of an enriched and exclusive educational background. Their sophistication is the product of an investment in cultural refinement that serves as the basis of status distinctions in society. Nevertheless, high culture itself is a product of focused and intensive cultural innovation and creativity.

The term popular culture refers to forms of cultural experience and attitude that circulate in mainstream society: cultural experiences that are well-liked by “the people.” Popular culture events might include folk music, hip hop, parades, hockey games, or rock concerts. Some popular culture originated in folk traditions like quilting, carnival festivities, fiddle music, spirit dancing, commedia dell’arte and religious festivals. Other pop culture is considered popular because it is commercialized and marketed to a wide audience. Rock and pop music — “pop” is short for “popular” — are part of modern popular culture that developed first with the publication of sheet music and then with recordings. In modern times, popular culture is often expressed and spread via commercial media such as radio, television, movies, the music industry, bestseller publishers, and corporate-run websites. Unlike high culture, popular culture is known and accessible to most people. One can expect to be able to share a discussion of favourite hockey teams with a new coworker, or comment on a current TV show when making small talk in the check-out line at the grocery store. But if you tried to launch into a deep discussion on the classical Greek play Antigone , few members of Canadian society today would be familiar with it.

Although high culture may be viewed as artistically superior to popular culture, the labels of high culture and popular culture vary over time and place. Shakespearean plays, considered pop culture when they were written, are now among Canadian society’s high culture. In the current “Second Golden Age of Television” (2000s to the present, the first Golden Age was in the 1950s and 1960s), television programming has gone from mass audience situation comedies, soap operas, and crime dramas to the development of “high-quality” series with increasingly sophisticated characters, narratives, and themes that require full attention and cultural capital to follow (e.g., The Sopranos , Breaking Bad , Game of Thrones, The Crown ).

Contemporary popular culture is frequently referred to as a postmodern culture. This is often presented in contrast to modern culture, or modernity. The term modernity refers to the culture associated with the rise of capitalism in which the world came to be experienced as a place of constant change and transformation, and culture as a sequence of new or contemporary “nows” in which the things of today are “modern” and those of yesterday old and no longer relevant (Sayer, 1991).

In the era of modern culture, or modernity, the distinction between high culture and popular culture framed the experience of culture in a more or less a clear way. One side of high culture in the 19 th and 20 th century was experimental and avant-garde, seeking new and original forms in literature, art, and music to authentically express the elusive, transient, ever-changing experiences of modern life. The other side of high culture was the tradition of conserving and passing down the highest and most refined expressions of human cultural possibility: the eternal values and noble sensibilities contained in the “great works” of culture. High culture had a civilizing mission to either capture and articulate new forms of experiencing the world, or to preserve, pass down and renew what was eternal in the tradition. In both forms, high culture appealed to a limited but sophisticated audience.

Popular culture, on the other hand, was simply the culture of the people; it was immediately accessible and easily digestible, either in the form of folk traditions or commercialized mass culture. It had no pretension to be more than entertainment and the site of momentary enthusiasms and fads — hit songs, bestsellers, popular film stars, fashion trends, house decor styles, dance crazes, etc.

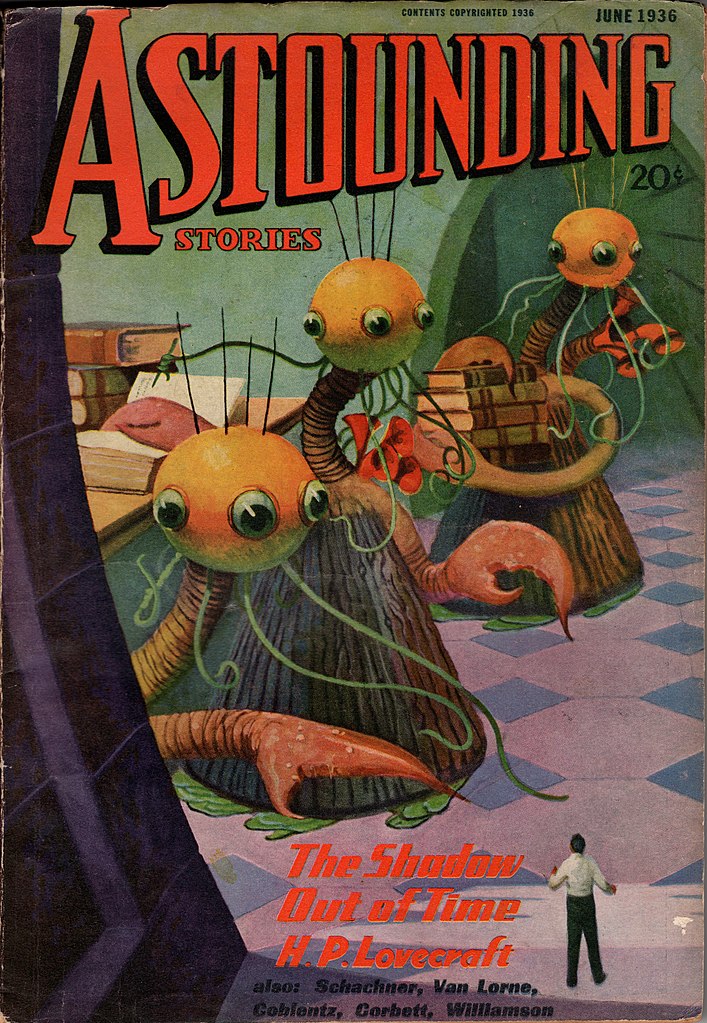

In postmodern culture — the form of culture that comes after or ‘post’ modern culture — this distinction begins to break down, and it becomes more common to find various sorts of mash-ups of high and low: Serious literature combined with themes from zombie movies; pop music constructed from recycled samples of original hooks and melodies; symphony orchestras performing the soundtracks of cartoons; architecture that playfully borrows and blends historical styles instead of inventing new ones; etc. Rock music is now the subject of many high brow histories and academic analyses, just as the common objects of popular culture are transformed into symbols with depth of meaning as high art (e.g., Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans or Marvel Studios epics based on kid’s comic books of the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s). The dominant sensibility of postmodern popular culture is both playful and ironic, as if the blending and mixing of cultural sources, like in the television show The Simpsons , is one big in-joke based on references that only people ‘in the know’ will get. Postmodern culture has therefore been referred to as a “culture of quotations” (Jameson, 1985) in the sense that instead of searching for new, authentic forms, as in avant-garde modernism, or preserving and revering high cultural sensibilities, as in the classics, it recycles and remixes (i.e., quotes) elements of previous cultural production, often with a tongue in cheek ironic attitude.

Frederic Jameson (1985) argues that the mixing and blending of postmodern culture is not just a cultural trend or fashion, but reflects an underlying shift in the nature of culture itself. From a historical materialist perspective, if the culture of modernity was tied to the rise of industrial capitalism, the culture of postmodernity is tied to late capitalism . The culture of modernity was focused on the new, just as capitalism has to constantly innovate in the pursuit of markets and profitability. But the categories of high and low remained stable, just as the commodities of industrial capitalism remained concrete: resources, appliances, automobiles, etc. However, late capitalism is much less concrete. The commodities of late capitalism are frequently images, brands, services and knowledge rather than tangible industrial products. The dominant technologies are computer codes and instantaneous communication networks rather than railroads and industrial machinery. Flows of capital investment are globalized rather than centered in particular national economies and cultures. Jameson argues that under these circumstances it becomes increasingly difficult to “cognitively map” ones location in this complex global space, although this is what a culture is suppose to do.

The outcome is the emergence of a postmodern culture, which is seen to challenge modern culture in a number of key ways. The postmodern eclectic mix of elements from different times and places challenges the modernist concepts of authentic expression and progress. The idea that cultural creations can and should seek new and innovative ways to express the truths and deep meanings of life was linked to a belief in social progress. The playfulness and irony of postmodern culture seem to undermine the core values of modernity, especially the idea that cultural critique or innovations in architecture, art, and literature, etc. have an important role in, not just entertaining people, but improving the quality of social life. In postmodernity, nothing is to be taken very seriously, even people themselves. Moreover, in postmodernity everyone with access to a computer and some editing software is seen to be a cultural producer; everyone has a voice and with enough “likes” any voice can be important and influential. Access to knowledge does not require arduous and careful research but is simply a matter of crowd-sourcing. The modernist myth of the great creator or genius is rejected in favour of populism and a plurality of voices.

Jean Francois Lyotard (1984) defines postmodern culture as “incredulity towards metanarratives” meaning that postmoderns no longer really believe in the big (i.e., meta) stories and social projects of modernity: progress towards universalization, rationalization, and systemization. Postmoderns are skeptical of the claims that scientific knowledge leads to progress, that political change creates human emancipation, that Truth sets people free.

Some argue pessimistically that the outcome of this erosion of authority and decline in consensus around core values is a thorough relativism of values in which no standard exists to judge one thing to be more significant than another. Everyone makes up their own little stories, each as valid as the next — as sociologists have observed with regard to conspiracy theories, or people “doing their own research” on the science of climate change or vaccines. The outcome of the postmodern condition is a culture without a consensus on common, shared standards of truth, value or even a shared reality.

Others argue optimistically that the outcome leads to pluralization, an emancipation from centralized institutions of authority, and a weakening of attachments to the dominant culture. It brings a loosening of social bonds and increased freedom. Postmodernism enables a necessary critique of the unexamined assumptions of power and authority in modern culture — the rhetoric of patriotism, “family values,” or “scientific progress” lampooned in The Simpsons, for example. Instead of the privileged truths of elites and authorities, postmodernity witnesses the emergence of a plurality of different voices that had been relegated to the margins. Culture moves away from homogeneous sameness and uniformity to heterogeneous diversity.

Subculture and Counterculture

A subculture is just as it sounds — a smaller cultural group within a larger parent culture. People of a subculture are part of the parent culture, but also share a specific identity within a smaller group that distinguishes them. Many subcultures exist within Canada. Within larger ethnic groups, who share the language, food, and customs of their heritage, are subcultures like Rastafarianism, Bhangra, or Chadō. Other subcultures are united by shared pastimes. For example, biker culture revolves around a dedication to motorcycles. Some subcultures are formed by members who possess traits or preferences that differ from the majority of a society’s population. The body modification community embraces aesthetic additions to the human body, such as tattoos, piercings, and certain forms of plastic surgery. But even as members of a subculture band together around a distinct identity, they still identify with and hold many things in common with their larger parent culture.

As Hall, Jefferson and Roberts (1975) point out with respect to bohemian subculture for example:

The bohemian sub-culture of the avant-garde which has arisen from time to time in the modern city, is both distinct from its ‘parent’ culture (the urban culture of the middle class intelligentsia) and yet also a part of it (sharing with it a modernising outlook, standards of education, a privileged position vis-a-vis productive labour, and so on).

Sociologists distinguish subcultures from countercultures , which are a type of subculture that explicitly reject the larger culture’s norms and values. In contrast to subcultures, which operate relatively smoothly within the larger society, countercultures actively defy larger society by developing their own set of rules and norms to live by, sometimes even creating alternative communities that operate outside of the greater society. Vegans who choose to not eat meat, fish or dairy products because they like the health benefits, cuisine or lifestyle of the vegan diet would be an example of a subculture. Although this dietary choice is distinct from the dominant culture, dietary health, pleasure in good food and making lifestyle choices are consistent with dominant cultural values. However, vegans who reject the industrial food system and the harvesting of animals for human consumption entirely have to take more radical steps to build a life which is consistant in itself and outside or counter to the dominant norms and structures of society.

The post-World War II period was characterized by a series of “spectacular” youth cultures — teddy boys, beatniks, mods, hippies, bikers, skinheads, Rastas, punks, new wavers, ravers, hip-hoppers, and hipsters — who in various ways sought to reject the values of their parents’ generation. For some, joining these groups was just for the music, clothing or style of life. But for others, the rejection of the dominant culture had more radical implications. The hippies, for example, were a subculture that became a counterculture, blending protest against the Vietnam War, industrial technology, and consumer culture with a back to the land movement, non-Western forms of spirituality, and the practice of voluntary simplicity. They “explored ‘alternative institutions’ to the central institutions of the dominant culture: new patterns of living, of family-life, of work or even ‘un-careers’” (Hall, Jefferson and Roberts, 1975). Counterculture, in this example, refers to the culture or way of life taken by a political and social protest movement.

Cults, a word derived from cultus or the “care” owed to the observance of spiritual rituals, are also considered countercultural groups. They are usually informal, transient, religious groups or movements that deviate from orthodox beliefs and often, but not always, involve an intense emotional commitment to the group and allegiance to a charismatic leader. In pluralistic societies like Canada, they represent quasi-legitimate forms of social experimentation with alternate forms of religious practice, community, sexuality and gender relations, proselytizing, economic organization, healing, and therapy (Dawson and Thiessen, 2014). However, sometimes their challenge to conventional laws and norms is regarded as going too far by the dominant society. For example, the group Yearning for Zion (YFZ) in Eldorado, Texas existed outside the mainstream, and the limelight, until its leader was accused of statutory rape and underage marriage. The sect’s formal norms clashed too severely to be tolerated by U.S. law, and in 2008 authorities raided the compound, removing more than 200 women and children from the property (Oprah.com, 2009).

The degree to which countercultures reject the larger culture’s norms and values is questionable, however. In the analysis of spectacular, British working class youth subcultures like the teddy boys, mods, and skinheads, Phil Cohen (1972) noted that the style and the focal concerns of the groups could be seen as a “compromise solution between two contradictory needs: the need to create and express autonomy and difference from parents…and the need to maintain parental identifications” (as cited in Hebdige, 1979). In the 1960s and 70s, for example, skinheads shaved their heads, listened to ska music from Jamaica, participated in racist chants at soccer games, and wore highly polished Doctor Marten boots (“Doc Martens”) in a manner that deliberately alienated their working class parents while expressing their own adherence to blue collar working class imagery. At the same time, noted Cohen, their subcultural outfit was more or less a “caricature of the model worker” their parents aspired to, and their attitude simply exaggerated the proletarian, puritanical, and chauvinist traits of their parents’ generation. On one hand, the invention of skinhead culture was an innovative cultural creation that seemed to reject the dominant culture; on the other hand, it just exaggerated and reproduced the already existing contradictions of the skinheads’ class position and that of their parents.

Making Connections: Sociology in the Real World

The evolution of north american hipster subculture.

Skinny jeans, chunky glasses, ironic moustaches, retro-style single speed bicycles, and T-shirts with vintage logos — the hipster is a recognizable figure in contemporary North American culture. Predominantly based in metropolitan areas, hipsters seek to define themselves by a rejection of mainstream norms and fashion styles. As a subculture, hipsters spurn many values and beliefs of North American society, tending to prefer a bohemian lifestyle over one defined by the accumulation of power and wealth. At the same time they evince a concern that borders on a fetish with the pedigree of the music, styles, and objects that identify their focal concerns.

When did hipster subculture begin? While commonly viewed as a recent trend among middle-class youth, the history of the group stretches back to the early decades of the 1900s. In the 1940s, black American jazz music was on the rise in the United States. Musicians were known as hepcats and had a smooth, relaxed style that contrasted with more conservative and mainstream expressions of cultural taste. Norman Mailer (1923 – 2007), in his essay The White Negro: Superficial Reflections on the Hipster (1957), defined those who were “hep” or “hip” as largely white youth living by a black jazz-inspired code of resistance, while those who were “square” lived according to society’s rules and conventions.As hipster attitudes spread and young people were increasingly drawn to alternative music and fashion, attitudes and language derived from the culture of jazz were adopted. Unlike the vernacular of the day, hipster slang was purposefully ambiguous. When hipsters said, “It’s cool, man,” they meant not that everything was good, but that it was the way it was.

By the 1950s, another variation on the subculture was on the rise. The beat generation, a title coined by Quebecois-American writer Jack Kerouac (1922-1969), was defined as a generation that was nonconformist and anti-materialistic. Prominent in this movement were writers and poets who listened to jazz, studied Eastern religions, experimented with different states of experience, and embraced radical politics of personal liberation. They “bummed around,” hitchhiked the country, sought experience, and lived marginally. Even in the early stages of the development of the subculture there was a difference between the emphasis in beat and hipster styles:

. . . the hipster was . . . [a] typical lower-class dandy, dressed up like a pimp, affecting a very cool, cerebral tone — to distinguish him from the gross, impulsive types that surrounded him in the ghetto — and aspiring to the finer things in life, like very good “tea,” the finest of sounds — jazz or Afro-Cuban . . . [whereas] . . . the Beat was originally some earnest middle-class college boy like Kerouac, who was stifled by the cities and the culture he had inherited and who wanted to cut out for distant and exotic places, where he could live like the “people,” write, smoke and meditate (Goldman as cited in Hebdige, 1979)

While the beat was focused on inner experience, the hipster was focused on the external style.

By the end of the 1950s, the influence of jazz was winding down and many traits of hepcat culture were becoming mainstream. College students, questioning the relevance and vitality of the American dream in the face of post-war skepticism, clutched copies of Kerouac’s On the Road , dressed in berets, black turtlenecks, and black-rimmed glasses. Women wore black leotards and grew their hair long. The subculture became visible and was covered in Life magazine, Esquire , Playboy , and other mainstream media. Herb Caen (1916-1997), a San Francisco journalist, used the suffix from Sputnik 1 , the Russian satellite that orbited Earth in 1957, to dub the movement’s followers as “beatniks.” They were subsequently lampooned as lazy layabouts in television shows like The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis (1959-1963) or dangerous, drug-abusing delinquents in movies like High School Confidential (1958).

As the beat generation faded, a new related movement began. It too focused on breaking social boundaries, but also advocated freedom of expression, philosophy, and love. It took its name from the generations before; in fact, some theorists claim that the beats themselves coined the term to describe their children. Over time, the “little hipsters” of the 1960s and 70s became known simply as hippies. Others note that hippie was a derogatory label invented by the mainstream press to discredit and stereotype the movement and its non-materialist aspirations.

Contemporary expressions of the hipster rose out of the hippie movement in the same way that hippies evolved from the beats and beats from hepcats. Although today’s hipster may not seem to have much in common with the jazz-inspired youth of the 1940s, or the long-haired, back-to-the-land movement of the 1960s, an emphasis on nonconformity persists. The sociologist Mark Greif set about investigating the hipster subculture of the United States and found that much of what tied the group together was not a specific set of fashion or music choices, nor a specific point of contention with the mainstream. What has emerged, rather, is an appropriation of consumer capitalism that seeks authenticity in and of itself. In his New York Times article “The Hipster in the Mirror” Greif wrote, “All hipsters play at being the inventors or first adopters of novelties: pride comes from knowing, and deciding, what’s cool in advance of the rest of the world” (2010). What tends to be cool is an ironic pastiche of borrowed styles or tastes that signify other identities or histories: alternative music (sometimes very obscure), used vintage clothing, organic and artisanal foods and products, single gear bikes, and countercultural values and lifestyles.

Young people are often drawn to oppose mainstream conventions. Much as the hepcats of the jazz era opposed common culture with carefully crafted appearances of coolness and relaxation, modern hipsters reject mainstream values with a purposeful apathy, while embracing their particular enthusiasms with what seems to others like excessive intensity and attention to detail. Ironic, cool to the point of non-caring, and intellectual, hipsters continue to embody a subculture while simultaneously impacting mainstream culture.

Global Culture

The integration of world markets, technological advances, global media communications, and international migration of the last decades have allowed for greater exchange between cultures through the processes of globalization and diffusion . As noted in Chapter 1. An Introduction to Sociology , globalization refers to the ways in which people no longer “live and act in the self-enclosed spaces of national states and their respective national societies” (Beck, 2000). Globalization is the process by which “a supraterritorial dimension of social relations” emerges and spreads (Scholte, 2000). The world is becoming one place, like a “global village,” as Canadian media theorist, Marshall McLuhan (1962) described. In this context, culture itself has become increasingly globalized. Life styles, activities, cuisines, clothing styles, cultural references, religions, music preferences, images, news reports and many other facets of contemporary cultural life are no longer pinned to the location where people live or grew up.

Globalization has been a process underway for 500 years but it has intensified over the last 30 years. Arjun Appadurai (1996) describes five dimensions of global cultural “flow” that have reshaped the landscape of culture in the 21st century.

- First is the increased movement or flow of people who bring their local cultures with them. He refers to this process as the creation of a new global ethnoscape : “tourists, immigrants, refugees, exiles, guest workers, and other moving groups and individuals constitute an essential feature of the world and appear to affect the politics of (and between) nations to a hitherto unprecedented degree.”

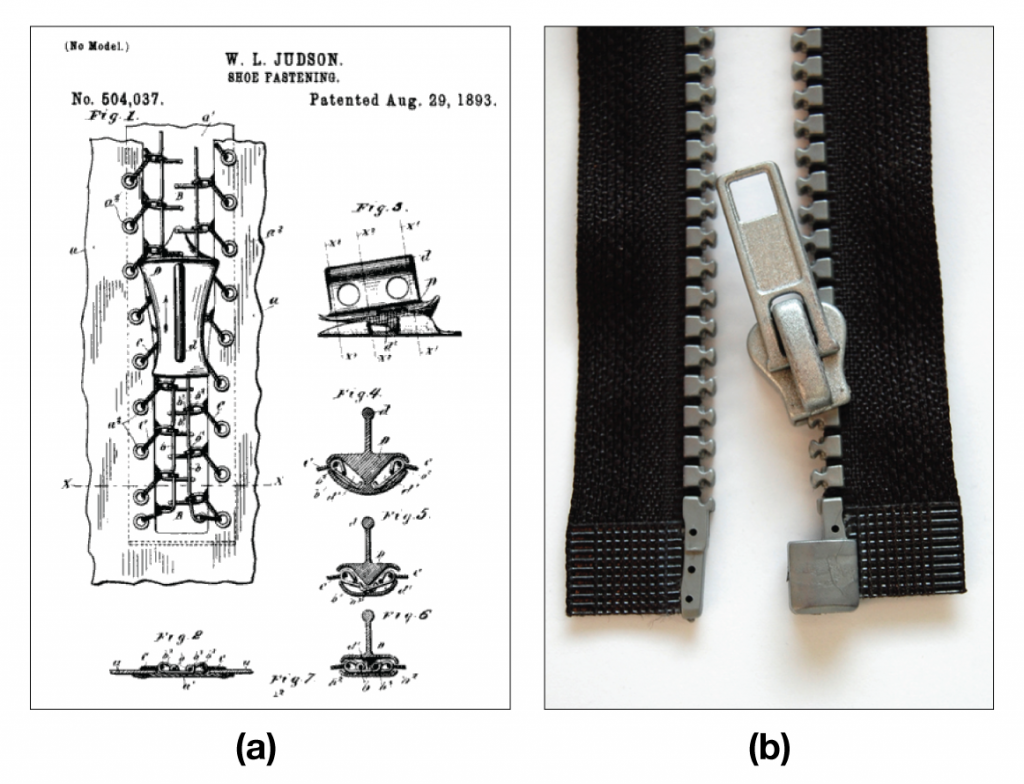

- Second is the spread of technologies across borders, from electric toothbrushes and automobile parts to smart phones and biotech, which creates a global technological configuration or technoscape . Among other things, the global spread of technologies requires an immense amount of global cooperation to define the 22,000 international standards that allow technical components to work together (Frost, 2018).

- Third is the creation of new financescapes. Beginning in the 1970s, Western governments began to deregulate social services while granting greater liberties to private businesses. As a result of this process of neoliberalization, world markets became dominated by unregulated, international flows of capital investment and new multinational networks of corporations. A global economy emerged to surpass nationally-based economies.

- Finally Appadurai describes the new mediascapes and ideoscapes that emerge as people consume media content and political or religious discourses from different locations through global film and TV distribution, social media platforms like Google, Facebook and Twitter, and other electronic means of news and personal communication. These create “large and complex repertoires of images, narratives, and ethnoscapes to viewers throughout the world, in which the world of commodities and the world of news and politics are profoundly mixed” (Appadurai, 1996). The world shares a common information (and disinformation) space.

These processes of cultural globalization can be summed up by the term diffusion , which refers to the spread of material and non-material culture. Middle-class North Americans can fly overseas and return with a new appreciation of Thai noodles or Italian gelato. Access to television and the internet has brought the lifestyles and values portrayed in Hollywood sitcoms and “reality” TV series into homes around the globe. Twitter feeds from public demonstrations in one nation have encouraged political protesters in other countries. When this kind of diffusion occurs, material objects and ideas from one culture are introduced into another creating new and complex landscapes of cultural diversity.

Diaspora and Hybridity

One aspect of this complex landscape of cultural diversity is the creation of diasporas . The increasing flows of global migrants, temporary foreign workers, and political or economic refugees create globalized and displaced local communities as people from around the world spread out into global diasporas: the communities that emerge through resettlement of a people from their original homeland to new locations. As Arjun Appadurai (1996) suggests, “More people than ever before seem to imagine routinely the possibility that they or their children will live and work in places other than where they were born: this is the wellspring of the increased rates of migration at every level of social, national, and global life.” This likelihood of movement, whether actual or imagined, changes the cultural coordinates of how people see themselves in the world.

All migrants, refugees, temporary foreign workers, or travelers bring their beliefs, attitudes, languages, cuisines, music, religious practices, and other elements of local ways of life with them when they move, and they encounter new ones in the places where they arrive. What would appear to be different in the contemporary era of global migration is the way in which electronic media make it possible for migrants and travelers to keep in touch daily with not only friends and family, but also favourite TV shows, current events, sports, music, and other elements of culture from home. In the same way, electronic media give migrants access to the culture of their new homes just as they allow local residents to imagine future homes elsewhere in the world. In the era of globalization, the experience of culture is increasingly disembedded from location. The ways people imagine themselves and define their individual attachments, interests, and aspirations criss-cross and intertwine the divisions between cultures formerly established by the territorial boundaries of societies.

Hybridity in cultures is one of the consequences of the increased global flows of capital, people, culture, and entertainment. Hybrid cultures refer to new forms of culture that arise from cross-cultural exchange, especially in the aftermath of the colonial era. On one hand, there are blendings of different cultural elements that had at one time been distinct and locally based: fusion cuisines, mixed martial arts, and New Age shamanism. On the other hand, there are processes of Indigenization and appropriation in which local cultures adopt and redefine foreign cultural forms. The classic examples are the cargo cults of Melanesia in which isolated Indigenous peoples “re-purposed” Western goods (cargo) within their own ritualistic practices in order to make sense of Westerners’ material wealth. Other examples include Arjun Appadurai’s (1996) discussion of how the colonial Victorian game of cricket has been taken over and absorbed as a national passion into the culture of the Indian subcontinent. Similarly, Chinese “duplitecture” reconstructs famous European and North American buildings, or in the case of Hallstatt, Austria, entire villages, in Chinese housing developments (Bosker, 2013). As cultural diasporas or emigrant communities begin to introduce their cultural traditions to new homelands and absorb the cultural traditions they find there, opportunities for new and unpredictable forms of hybrid culture emerge.

Making Connections: Big Picture

Is there a canadian identity.

The 2014 purchase of the Canadian coffee and donut chain Tim Hortons by 3G Capital, the American-Brazilian consortium that owns Burger King, raised questions about Canadian identity that never seem far from the surface in discussions of Canadian culture. For example, an article by Joe Friesen (2014) in The Globe and Mail emphasized the potential loss to Canadian culture by the sale to foreign owners of a successful Canadian-owned business that is also a kind of Canadian institution. Tim Hortons’s self-promotion has always emphasized its Canadianness: from its original ownership partner, Tim Horton (1930-1974), who was a Toronto Maple Leafs defenceman, to being a kind of “anti-Starbucks,” the place where “ordinary Canadians” go. Friesen’s article reads a number of Canadian characteristics into the brand image of Tim Hortons. For example, the personality of Tim Horton himself is equated with Canadianness of the chain: “He wasn’t a flashy player, but he was strong and reliable, traits in keeping with Canadian narratives of solidity and self-effacement” (Friesen).

How do we understand Canadian culture and Canadian identity in this example? Earlier in the chapter, we described culture as a product of the socioeconomic formation. Therefore, if we ask the question of whether a specific Canadian culture or Canadian identity exists, we would begin by listing a set of distinctive Canadian cultural characteristics and then attempt to explain their distinctiveness in terms of the way the Canadian socioeconomic formation developed.

Seymour Martin Lipset (1990) famously described several characteristics that distinguished Canadians from Americans:

- Canadians are less self-reliant and more dependent on state programs than Americans to provide for everyday needs of citizens.

- Canadians are more “elitist” than Americans in the sense that they are more respectful and deferential towards authorities.

- Canadians are less individualistic and more collectivistic than Americans, especially in instances where personal liberties conflict with the collective good.

- Overall, Canadians are more conservative than Americans, and less likely to embrace a belief in progress or a forward looking, liberal outlook on political or economic issues.

Lipset’s explanation for these differences is that while both Canada and the United States retain elements from their British colonial experiences, like their language and legal systems, their founding historical events were opposite: the United States was created through violent revolution against British rule (1775-1783); whereas, Canada’s origins were counter revolutionary. Canada was settled in part by United Empire Loyalists who fled America to remain loyal to Britain, and it did not become an independent nation state until it was created by an act of the British Parliament (the British North America Act of 1867). While Lipset’s analysis is disputed, especially by those who do not see American and Canadian cultural differences as being so great (Baer et al., 1990), the logic of his analysis is to see the cultural difference between the nations as a variable dependent on their different socioeconomic formations. (Note: The idea that Canada — with its influential socialist tradition responsible for Canada’s universal health care, welfare and employment insurance, strong union movement, culture of collective responsibility, etc. — is more conservative than the United States may strike the reader as strange. Lipset’s assessment is based on uniquely American cultural definitions of conservatism and liberalism.)

In this analysis, the national characteristics that Friesen argues are embodied by Tim Hortons — modesty, unpretentiousness, politeness, respect, etc. — would be seen as qualities that emerged as a result of a uniquely Canadian historical socioeconomic development. However, how well do they actually represent Canadian culture? As we saw earlier in the chapter, one prominent aspect of contemporary Canadian cultural identity is the idea of multiculturalism. The impact of globalization on Canada has been an increased cultural diversity (see Chapter 11. Race and Ethnicity ). The 2011 census noted that visible minorities made up 19.1% of the Canadian population, or almost one out of every five Canadians. In Toronto and Vancouver, almost half the population are visible minorities. In a certain way, the existence of diverse cultures in Canada undermines the notion that a unified Canadian identity exists. Canada would appear to be a fragmented nation of hyphenated identities — British-Canadians, French-Canadians, Chinese-Canadians, South Asian-Canadians, Caribbean-Canadians, Indigenous-Canadians, etc. — each with its unique cultural traditions, languages, and viewpoints. In what way are we still able to speak about a Canadian identity except insofar as it is defined by multiculturalism — essentially, many identities?

Media Attributions

- Figure 3.26 Cover of Astounding Stories magazine, June 1936 : The Shadow out of Time by Howard V. Brown, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain .

- Figure 3.27 Celebration Town Hall in the Walt Disney town of Celebration, Florida by trevor.patt via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 licence.

- Figure 3.28 Colonna Infame Skinhead by Flavia, April 2010, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence.

- Figure 3.29 I FINALLY GOT A BIKE! by Lorena Cupcake via Flickr, is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

- Figure 3.30 [ Portrait of Bill (Buddy) De Arango, Terry Gibbs, and Harry Biss, Club Troubadour, New York, N.Y., between 1946 and 1948 ] by William P. Gottlieb/Ira and Leonore S. Gershwin Fund Collection, Music Division, Library of Congress, is in the public domain .

- Figure 3.31 Beatnik paper doll by Sarah, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 licence.

- Figure 3.32 Photo (a) Judson improved shoe fastening 1893 by U.S. Patent Office, via Wikimedia Commons; Photo (b) Reißverschluss offen [zipper open] by Rabensteiner via Wikimedia Commons; both in the public domain .

- Figure 3.33 Always a Line at Tim Horton’s by Caribb, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence.

Introduction to Sociology – 3rd Canadian Edition Copyright © 2023 by William Little is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Browse by Subjects

- New Releases

- Coming Soon

- Chases's Calendar

- Browse by Course

- Instructor's Copies

- Monographs & Research

- Intelligence & Security

- Library Services

- Business & Leadership

- Museum Studies

- Pastoral Resources

- Psychotherapy

Globalization and American Popular Culture

Fifth edition, lane crothers.

Now in a fully updated edition, this concise book explores the ways American movies, TV, music, fast food, sports, gaming, and fashion influence globalization. Projecting the future impact of popular culture, from both the United States and elsewhere, Crothers makes a powerful argument for its central role in shaping global politics and economies.

ALSO AVAILABLE

Managing Global Expansion in the K-Pop Industry: Strategic Lessons from YG Entertainment

- First Online: 01 January 2022

Cite this chapter

- Susan Bartholomew 4 &

- Joey Nadasdi 4

Part of the book series: Advances in Theory and Practice of Emerging Markets ((ATPEM))

1857 Accesses

1 Citations