The Family History Guide Blog

… See the latest news about your free learning and training site for family history!

The Value of Case Studies in Family History

“Could I have an example, please?” This is one of the most common questions we all have, about almost any subject, whether or not we ask it out loud. Good examples help us connect the dots in our learning. They help us see relationships between pieces of information, how cause and effect works, and how we can apply principles in a variety of ways.

On the other hand, an example that’s unfocused or unclear might be confusing and worse than no example at all.

It’s much the same in family history. We can find some great tools or pieces of information, but how do we apply them in our own research? That’s where a good case study can be really valuable. It not only walks us through solving a research problem, but it also does the following:

- Highlights the principles that were used

- Explains why they were effective

- Offers suggestions on how you might use them in your research

As you might expect, not all case studies are created equal. Sometimes you have to dig a bit to identify the principles and how you can use them. Be prepared to use “intelligent filters”—skip past any parts that are repetitious or wandering, and read between the lines to find nuggets of information you might need. In some ways, it’s like mining a historical record for insights. The tips and trick you learn will prove valuable as you search for clues in your own ancestors’ stories.

In this newspaper case study, the author helps us find research clues by using the following elements:

- Background : This sets the stage for the person we are following.

- Comparisons : The primary account of the story is compared with accounts from other newspapers. This shows the value of working with multiple sources in research.

- Next Steps : The author suggests additional approaches and record searches. This is good for a brief case study, while more extensive ones will provide details of what was found in the extra research.

- Takeaway : This is the main point learned from the case study. You can add your own takeaways, from your analysis of what you have read.

Case Studies in The Family History Guide

There are plenty of links to research case studies in The Family History Guide, from basic record finds, to tracing immigrant ancestors, to breaking through walls with DNA results, and more. Many of them are included in the Country and Ethnic pages, plus more in the Vault.

Here are a few of the case studies to get you started, in video and article formats (videos noted with their timings):

- ExploreGenealogy: Overcoming a Family History Roadblock

- Family Locket: Hooking Teens on Research with Land Patents

- Family Locket: Putting Your Ancestors in their Place

- BYU FHL: Case Studies in Migration for Genealogists —67:54

- FamilySearch: Using English Records— 16:00

- FamilySearch: A French Case Study: Church Records —5:54

- Ancestry DNA: Genealogy Brick Wall Case Study —21:26

- The Root: Who Were My Kin Born During Slavery?

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Categories: Case Studies Research U.S. Research

Related Posts

Family History: The Great Connector

Resources for the Mayflower Passengers and Their Descendants

Using DNA Results for Family History

Where was the event? Where are the records?

Goldie May Subway Map Now Works with Ancestry.com

New QRB Video: Starting Your Genealogy Research in Scotland

- EXPLORE Random Article

How to Write a Family History

Last Updated: October 11, 2022 Approved

wikiHow is a “wiki,” similar to Wikipedia, which means that many of our articles are co-written by multiple authors. To create this article, 14 people, some anonymous, worked to edit and improve it over time. There are 16 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. wikiHow marks an article as reader-approved once it receives enough positive feedback. In this case, 84% of readers who voted found the article helpful, earning it our reader-approved status. This article has been viewed 43,972 times.

Writing a family history can be a very special project to undertake. Not only will you find answers to the mystery of your ancestors' lives, but you will also compile a document that your future family members can use for generations to come. But family histories can be very large projects to manage. Having a clear plan of your scope and research resources will help you create an accessible text for your entire family.

Researching Your Family's History

- Get a rough idea of how far back in history you intend to search. This will help you decide what kinds of resources you need to explore.

- In addition to deciding how many ancestors you want to include, you should also consider if there is a particular geographical location you want to stick to. If your ancestors immigrated, do you want to conduct research about their lives in another country or do you want to keep it centered in one specific location?

- For instance, do you want to know why one branch of your family moved to another region of the country? Do you want to know the source of an old feud with another family? Asking something specific will help you narrow your scope and then branch out into other information. [3] X Research source

- Decide what you already know. How much information do your already have on your family? What gaps in knowledge exist? How do you intend to fill them?

- Land deeds and records (often available about the National Archives' web site for the U.S. as well as the records division of your local county courthouse)

- Census information (available at the U.S. Census Bureau's web site)

- Military records (National Archives)

- Ship passenger arrival records and land border entries (National Archives and The Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation Inc. web sites)

- Engagement/wedding announcements, birth announcements and obituaries (often in local newspapers or church bulletins)

- School yearbooks or old transcripts (usually available from the person's alma mater)

- Legal documents such as wills and testaments (also available at their corresponding courthouse)

- Church registries (check with local churches if you know your family has a history there)

- Old letters, journals or diaries from ancestors (ask older relatives if they have these)

- Family recipes and/or cookbooks

- Look for other physical items such as childhood toys, clothing, jewelry, kitchenware, and mementos/keepsakes kept by your older family members to include in your family history. These items will give you a sense of your relatives' tastes and interests beyond a basic genealogical record.

- Some of the most well-known genealogy libraries in the U.S. include the Library of Congress, the New York Public Library, the Midwest Genealogy Center, the Family History Center in Salt Lake City, the New England Historic Genealogical Research Center Library, and the Clayton Library Center for Genealogical Research in Houston. [6] X Research source

- You may find that taking the time to visit one of these libraries will actually save you time in the long run because of the wealth of resources they provide all in one place.

- You should also check your local library system to see what kind of genealogical resources they provide.

- They will often provide timelines and checklists so you can properly organize the information that you are gathering and save it in a digital space.

- On-line resources will also be convenient for sharing materials and records with other family members if you don't plan to send a physical copy of your family history to many readers. [8] X Research source

- Schedule the interview for a time and place that is convenient for your subject. This may be in their own home or in a more public place.

- Document the interview. You should plan to take notes during the discussion -- don't just assume that you will remember everything afterwards. If you don't want to take notes, try to record the interview with a recorder or video camera. [10] X Research source

- Ask important questions. These should include fact-finding questions (like the names of relatives/dates of important events), but you can also ask substantial questions about family traditions or customs, family trips, and how your subject related to their local communities.

- Respect sensitive subjects. Over the course of a person's life, they may experience something very painful or have a moment they do not want to revisit. Respect your interviewee when they say they don't want to discuss something -- don't push them or make them feel uncomfortable. [11] X Research source

- If you do not know your interview subject well, consider asking if a close friend or relative of theirs will accompany you during the interview. This might make your subject more comfortable while they are talking to you if you are a stranger. [12] X Research source

Drafting Your Family History

- Focus on narrating the story of your family rather than simply making lists on a family tree. Give details about your ancestors based on the research you have compiled. Did the family suffer financial ruin at one point? Did they have any disputes in court? Did anyone commit a major crime? These are the kind of substantial details that can make your history a compelling text to read.

- Consider if you want to divide sections of your history by time or by geography. For example, if one branch of your family is from one state, but another branch of the family still lives in a different country, consider dividing the family history into regional or geographical sections rather than by a historical timeline.

- The Index will be especially helpful to a reader who wants to learn about one member of the family in particular. [14] X Research source

- Instead, open with a compelling anecdote about your subject. Have you found a long lost love letter from Beauregard to his wife? Do you have evidence that he was entangled in a bitter land dispute with a neighbor? These are more compelling stories to use as an introduction to his history and they will hook your reader early on.

- You will generally need to cite a source whenever you directly quote from it or whenever you refer to it generally (as when you paraphrase or summarize a section from it).

- Most citations require the name of the author of the source, the date it was published, and the title of the work (such as The Journal of Beauregard Fortiscue, 1888-89 ).

- Sources from records such as the census or other similar documents should also be cited. Consult the style guide for specific instructions on how to cite it properly.

- If you have some extra money, you can also consider taking a class in non-fiction writing at your local college to help improve your writing skills.

- Writing groups will also give you a set of deadlines to meet while you are drafting your project.

- Look for local printers who use Xerox DocuTech if you only want to print a limited number of copies. These are often lower-cost options that also provide a quick turnaround. [20] X Research source

- Consider print-on-demand publishing. On web sites like Lulu, you can print one book at a time directly from a computer file (rates begin at $13 for 24 pages). This is a good option if you think you might only want a couple copies of your history. [21] X Research source

- You can also turn your history into an e-book for free on web sites like Scribd. [22] X Research source

- The website PlaceStories allows you to pick notable addresses on a digital map and then attach stories to them. You can consider using this site if you want to base your history geographically. [23] X Research source

- Vlog your research. You can also make a series of videos in which you discuss your research and then upload them to sites such as YouTube or Vimeo if you want to orally tell the story of your family.

- Consider using a digital newsletter that you can email to your friends and family. Each newsletter can feature a story about a different relative in your family history and it will present the information in easily digestible chunks as opposed to one long book. You can use services like MailChimp or ConstantContact to create these kinds of newsletters and mailing lists.

Understanding the Benefits of a Family History

- If you have been looking for a way to get closer to relatives you don't know very well or whom you have lost touch with, then researching a family history can be a great way to do this.

- Not surprisingly, the mental work of writing has also been shown to boost your memory. [28] X Trustworthy Source PubMed Central Journal archive from the U.S. National Institutes of Health Go to source

Expert Q&A

- If you find yourself suffering from writer's block, set manageable goals for yourself. Instead of sitting down to write for hours at a time (which can feel overwhelming and contribute to your block), give yourself a much more manageable amount of time, like 30-45 minutes. Writing even just a couple paragraphs can help you overcome mental hurdles. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://www.genealogy.com/articles/research/74_sharon.html

- ↑ https://familysearch.org/learn/wiki/en/Create_a_Family_History#Introduction.C2.A0.C2.A0_Happy_Family.jpg

- ↑ http://www.genealogy.com/articles/learn/101_course1.html

- ↑ http://www.familytreemagazine.com/article/9-libraries

- ↑ http://www.familytreemagazine.com/article/25-best-genealogy-websites-for-beginners

- ↑ http://www.nypl.org/blog/2015/01/07/conducting-interviews-genealogical-research

- ↑ http://www.writerswrite.com/journal/jul02/writing-a-non-boring-family-history-7024

- ↑ http://www.genealogy.com/articles/research/19_wylie.html

- ↑ https://familysearch.org/learn/wiki/en/A_Guide_to_Printing_Your_Family_History

- ↑ https://www.scribd.com

- ↑ http://placestories.com/about

- ↑ http://www.nypl.org/blog/2015/02/09/reasons-to-write-your-family-history

- ↑ http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0005789406000487

- ↑ http://jco.ascopubs.org/content/early/2014/01/21/JCO.2013.50.3532.abstract

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11561925

About this article

To write a family history, start by coming up with a specific question, like when your family came to America, to help you narrow down the scope of your research. Then, visit a genealogical library or use a website like ancestry.com to find information about your relatives, such as birth records or land deeds. Additionally, try to find some old family photographs to make your family history more visually interesting. Finally, make sure to include intriguing details about family members, like crimes they committed or financial struggles they overcame. For advice on how to publish your family history so you can share it with others, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

Reader Success Stories

Gayle McRitchie

Jun 12, 2017

Did this article help you?

Christina Huth

Oct 9, 2016

Abigail Bozzuto

Feb 7, 2017

- About wikiHow

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Choosing the Right Format When Writing Your Family History

Home » Blog » Choosing the Right Format When Writing Your Family History

CHOOSING THE RIGHT FORMAT WHEN WRITING YOUR FAMILY HISTORY

You’ve dreamed of writing a family history book for years. In fact, you’ve even started wading through old documents, photos, and records.

But after countless hours of research, you’re stuck.

What do you do with all of the materials you’ve gathered? What’s the best way to present your family’s history? What kind of a story do you want to tell — and how do you want to tell it?

Where do you even start?

The great thing about family history projects is that the options are almost limitless.

Want to keep things simple? You can stick to a just-the-facts family tree.

Want a sweeping epic that spans generations? Consider writing a novel-length family biography that weaves your ancestors’ stories together with important historical events.

Not a huge fan of writing? You can tell your family’s story through a collection of letters, journals, photographs, and other documents.

Of course, the drawback to all of these choices is choosing the right one for your family and your goals for the project.

Not sure which option is right for you? Join us for a deep dive into some of our favorite options — along with the pros and cons of each one.

Traditional Genealogy

Traditional styles are, by far, is the most straightforward way to organize your family history. The traditional, basic format shows how each person in your lineage is connected.

Considering this approach? Try one of these options:

Family Tree Style.

This style offers the bare facts of your ancestors, including names, birth and death dates, and how they relate to each other within the family line.

Family tree diagrams are great for illustrating smaller family relations, but can easily become quite cumbersome for larger families.

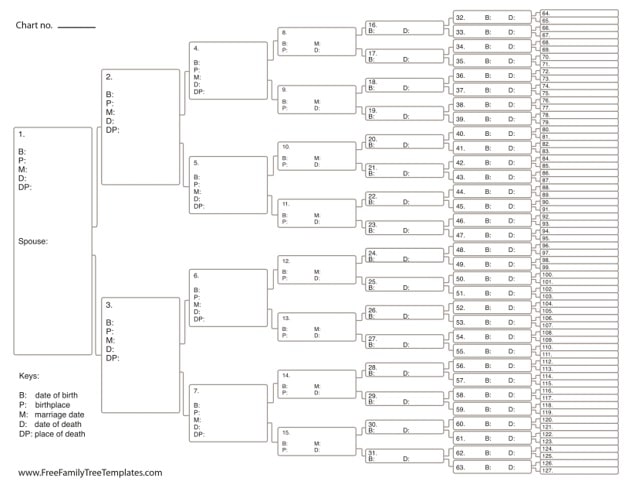

Ahnentafel Style.

Also known as a 'pedigree chart,' this option is similar to -- but more complex than -- a family tree and is a popular choice for historian archivists.

These charts can vary in layout, but they are always organized with the information starting in the present and moving backward into the past along the direct lineage. The information is organized based on a specific numbering and charting system that tracks family units or groups.

Register Style.

Another popular option with historic archivists and professional genealogists. Also known as the “Descendancy,” this style is the opposite of the Ahnentafel as it works from the past into the present from a common ancestor. Like the Anhentafel, though, this option uses a numbering system to organize people into families. However, registers also feature a very basic paragraph about each person that includes: the place of birth/baptism and birth/baptism date(s); place of death/burial and death/burial date(s); and place of marriage and marriage date.

Why go traditional?

All three styles of traditional genealogy are a great way to organize your research and data while compiling your family history.

And, since these options are focused on names, dates, and places, they’re great options if you’re not interested in doing a lot of writing.

They are also perfect for the genealogist and anyone else who wants to organize their information before starting a more writing-intensive option.

Drawbacks to consider:

While these formats make it easy to organize the data in a logical way, they’re not very exciting.

The end result is a dry, bare-bones list of names and dates, with no in-depth details about your family’s rich history.

Journaled Scrapbook

Also known as a “heritage scrapbook,” this style of family history includes names and dates, but it keeps things interesting with the addition of photos, notes, stories, documents, letters, journal entries, newspaper clippings, and anything else you can think of.

You can use a scanner and simple layout software to create your scrapbook digitally. This gives you the option to print multiple copies for several members of your family.

Or you can keep things old-school and create a one-of-a kind, paper-crafted scrapbook that that is placed within a binder.

Why this is a great option:

With the journaled scrapbook format, you can use a lot more of the documents and old photos you found in your research instead of letting them sit in a box.

Photos help give a rich element to your family history. You can even embellish them in a creative way with written narratives and any other documents you like.

Things to consider:

Printing can increase the overall cost of your project — especially if you’re using lots of photos and other graphics.

On the other hand, if you choose to do a paper-crafted scrapbook, you can save money — but you’ll be limited to only one copy to share with your family.

Theme-Based Family History

A theme-based family history is a great way to capture that interest while also chronicling the people along your lineage.

Did your family love to cook? Write a book of recipes shared across the generations, along with the stories about where the recipes came from and other interesting details.

Were there a lot of military men and women in your family? Write about their bravery and experiences during their service, and how that affected the family line.

Maybe there were plenty of “black sheep,” adventurers, or renegades in your family line. Base your family history around their colorful experiences.

Really, there is no shortage of ideas on topics you could use to present your family histories.

Why choose a theme-based option:

There are lots of topics you can choose from within your family history to write about.

Whether visual or narrative in form, it is a great way to present a special family theme that can be shared with all your relatives. You can mix photos, documents, and narratives along with items like recipes, letters, etc.

What to know before you start:

Just like with a journaled scrapbook, theme-based history books often include lots of photos, notes, and other documents, which means it can be costly to print.

Creating a book with a special theme or narrow scope also means leaving out many other aspects and stories — or even people — that don’t fit within the book’s focus.

Family Biography

A family biography is a narrative story of a whole family’s history, and it can provide a look at a direct family line/surname or a broader view of several directly connected lines.

This format is a lot like a novel.

You write a narrative about your ancestors using notes, memories, and a bit of creative license here and there.

Your family’s narrative is set against a historical backdrop and often includes information about historical events, politics, economic conditions, and other historical circumstances that influenced your descendants.

Why a biography?

This format gives you the ability to use all the facts you collected in a more compelling way while bringing your family’s history alive.

You can get in-depth and provide meaning and context. You can also tell some amazing stories without worrying if they’ll “fit” within a specific space or theme.

Drawbacks of a biography-style book:

This option works best if you have plentiful resources to draw upon, such as old letters and journals actually written by family members you are writing about.

Without that firsthand perspective, it’s all too easy to make assumptions about your ancestors’ actions, beliefs, and decisions.

Anthology-Style History

This format an anthology, which is a collection of stories typically written to fit into a certain subject or theme.

To use this format you would select which family members’ stories you want to highlight and write each one separately.

Each family member’s story would be a chapter or section in our book, and each story would work together in some way to illustrate a certain theme, idea, time period, or even a memory.

Again, there is no shortage of ideas for compiling an anthology-style family history. You could write stories about all the women or all the men in one direct line.

Or you could even transcribe family members’ memories or interpretations of a certain important family event.

The benefits of an anthology:

This format can include more in-depth information into each individual, creating a more complete portrait of each family member you write about.

You can also ask family members to write their own stories and send them to you, which means less writing work for you — and more colorful and varied stories for readers.

The challenges of an anthology-style approach:

While it is said everyone has a story to tell, not every family member’s story will be equally compelling.

You’ll need to make sure that you have enough stories to make an interesting book, and you should be willing to scale the project up or down as needed.

For example, you might find that, out of ten women in your family, only six have stories that would be interesting to others.

And if you are having other family members write their own stories, you may find they don’t write well and may get narrative back that needs to be rewritten.

CAPTURE THEIR VOICES, TODAY

Preserve your family history

HIRE A GHOSTWRITER

Event Histories

Another interesting way to write your family’s history is by capturing certain events and writing about how they affected your ancestors.

Going from past to present, taking a large, or even smaller, historical event that your ancestors experienced can be an interesting way of presenting the facts of both the event and your family and show how it shaped the family line.

Examples: Did you have groups of ancestors who documented their experiences during the Civil War?

Maybe you have a relative who was alive during the 1906 San Francisco earthquake?

Or maybe you’d like to focus on a direct ancestor’s arrival in America and how that changed his life and future of the family.

The pros of taking a historical approach: Writing about your ancestors in a historical context can bring out stories you may never have thought of before.

And learning how certain events influenced them or pushed them to do certain things and see life in a certain way can add a great richness to your family history.

A few cons to consider: Certain events — such as war, natural disasters, and the like — can be difficult or even depressing to write about, and you may even hear a few stories that you wish you hadn’t.

This isn’t to say that every story in your family history has to have a happy ending — but it’s best to be prepared to hear some less-than-positive details.

A memoir is a historical account written from one’s own personal experience.

To write a memoir about your family history, you, the writer, would write an account of your family history and the members of your family.

You could also consider writing about an important event as it relates to your family from your own memories, interpretations, experiences, and your conducted research.

While some people choose to interview family members for their perspectives when writing a memoir, most memoirs are written solely from the perspective of the author.

Depending on your age and your memory recall, the time span of your family’s history would be closer to the present and be more subjective in nature than complete fact.

Example: The Hillbilly Elegy by J.D. Vance

This format offers you flexibility and creativity to blend family facts with your own memories and personal interpretation. If you enjoy writing, you’ll likely find that this is one of the most interesting and compelling ways to highlight your family’s history through your own personal lens.

The (potentially) not-so-good:

One of the biggest problems with this sort of family history is the subjective nature of the writing.

It is typically based mostly on your own interpretation and assumptions with no room for other family member’s input. You may find that you are too personally entwined with the events, which it can cloud your memory and hinder your ability to write objectively.

Living Memory

Instead of relying solely on YOUR memory, you can collect all the memories you can from living relatives and combine them with surviving historical documents to produce a single narrative, anthology, or scrapbook.

Examples: To help get you started capturing the memories of your family members, consider these resources: Your Story: A Guided Interview Through Your Personal & Family History by Gift to the Future2000 Inc (Author), Inc Staff Gift To The Future 200 (Author) ; The Story of a Lifetime: A Keepsake of Personal Memoirs by Pamela Pavuk (Author), J. Richard Huxen (Author) ; To Our Children’s Children: Preserving Family Histories for Generations to Come by Bob Greene (Author), D. G. Fulford (Author)

What’s great about this option:

By including stories from multiple family members, you’re sure to get a wide variety of viewpoints, ideas, and stories to include in your book.

Your relatives will feel more included and this format really makes the book a true family story.

What ‘s challenging about it:

People often remember things differently — and with so many different voices and viewpoints, you might get conflicting memories to the same stories.

You may also get stories that don’t work cohesively together (this is why it might be helpful to provide family members with pre-written questions or to interview them in groups).

Of course, if you love the idea of putting together a family history — but feel apprehensive about the amount of research or writing required for your preferred format – a ghostwriter can help. Bringing in an outside resource can help you stay organized, keep your project on track, and help you fine-tune your writing.

Whether you choose a handmade scrapbook, an anthology of personal narratives, or a short-and-sweet family tree, you’ll find that this project will be rewarding for everyone involved. And you’ll likely learn a thing or two about your family along the way.

Related Content

6 thoughts on “ Choosing the Right Format When Writing Your Family History ”

I want see about my last name for corff family tree please thank you

Hi Catherine! We’d love to help you with your family tree project! Please feel free to contact us through our website ( https://www.thewritersforhire.com/contact/ )or by calling us at 713-465-6860.

I would like to write a book about one branch of my family from when they arrived in America to current living family members. I have photos, documents, letters, many stories about certain members, much research about their occupations in some case. I have also researched inventions of the times that changed their standard of living. I can easily add current events of their time. What format is best to use in your opinion?

It sounds like you have put a lot of work into your family history! If you have a lot of images and documents that you want to include, you may want to consider a journaled scrapbook. However, if your content is more heavily story-based, we’d recommend going the biography or anthology route.

Good luck! And please let us know if we can help you with your book.

The payoff for all this detective work is nothing less than time traveling through your family history. You will get to know your ancestors in a more intimate and meaningful way.

We couldn’t agree more!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Subscribe to Newsletter

- The Impact of AI-Generated Content on SEO Rankings

- Top Tools for Harnessing AI for Your Content

- 5 Ways to Make Your Content Marketing Campaign About Your Customers, Not You

- Harnessing AI Created Content for Thought Leadership Success

- Networking: Building Your Network with Content Marketing Best Practices

- Copywriting & PR

- Editing & Proofreading

- Writer's Resources

- Training & HR Material

- Ghostwriting & Books

- Social Content

- Web Content

- Corporate & Stakeholder Communications

- Technical Writing

- Medical Copy

- O&G Copy

- Thought Leadership Content

- RFPs & Proposals

- Speeches & Presentations

- Watercooler

ADVERTISEMENT

9 Tips for Getting Started on Writing Your Family History

Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

" * " indicates required fields

Written by Diane Haddad, unless otherwise noted.

Once you’ve been doing genealogy research for a while, and you have a family tree or a computer hard drive or a filing cabinet with a bunch of notes and old records, you might wonder what to do with it all. Or perhaps you’ve always harbored the dream of sharing your family history, and you’re not sure how.

It’s a hard truth: Few people have much use for an unstructured assortment of documents and computer files. Even folks who are curious about their family history—and that describes most I’ve met—aren’t likely to sort through your research and rebuild the store of knowledge you’ve amassed over years.

If your family research is to live beyond you, you’ll need to do the work of putting it into some shareable, lasting form. That usually means summarizing your finds in writing, maybe enhanced with photos and images of interesting documents. Whether you go all-out with a self-published hardback or just pass out stapled pages at the next family reunion, you’ll create a legacy—a framework others can use to understand your family’s story and the genealogical evidence you’ve gathered.

We can’t promise the project will be a breeze, but we can promise it’ll be easier when you follow these tips and use our handy organizing worksheet.

1. Know Your Purpose

Before you begin, it’s important to know what you hope to accomplish with this writing project. Do you want to summarize all your research, share your family legacy, pass down the stories Grandpa told, tell how your family fits into local history, share the story of an ancestor or family you admire, celebrate your ethnic heritage, or something else?

A strong focus makes the project more manageable, says Sunny Jane Morton, author of Story of My Life . “A small, finished project is better than a three-volume tome that exists only in your dreams.”

Need help narrowing the scope? Morton advises looking at your research for the most compelling story or interesting person. Author Sophia Wilson, who penned an 160,000-word history of her family, started her project by writing as many family stories as she could think of, then turning them into short biographies of the people involved. She wrote every day for at least 15 minutes, but sometimes for hours at a time. Taken together, those biographies served as the starting point for her project.

Alternately, you could choose a topic that commemorates an upcoming family milestone, such as your parents’ 40th wedding anniversary. Or you might start with whatever is most doable.

Your audience is an important aspect of your goal. For a project just family will see, you might use a casual writing style, refer to relatives with familiar titles (“Great-grandpa Thornton”), and use in-text source information. If other genealogists will read your work in a newsletter, journal or published book, you’ll want a more authoritative style with an emphasis on your research process, and formal source citations in footnotes and source lists.

Think about your audience’s age (or level of maturity), too. Wilson recalls how her research turned up stories that might not be appropriate to a younger audience. “Instead of shifting the focus of my book, I decided that children could simply read the unvarnished truth once they were mature enough,” Wilson says. “Age-appropriate stories could be extracted and adapted for a younger audience, for whom I would also write at a lower reading level.”

“I kept coming back to what I wanted the project to accomplish (preserving and sharing memories for the younger generation) and letting that guide my decisions,” she says.

2. Make a Plan

An outline gives you a framework for building your project, especially if it involves multiple people or a long time span. Make a list of elements you want to include. Don’t worry about organizing the list yet.

Here’s an example for my maternal family history opus:

- a family tree of Mom’s family

- information about the places the family came from with a map, including why so many immigrated from each place

- names and immigration details of all the immigrant ancestors: Henry Seeger, Eduard Thoss, Mary Mairose, Thomas Frost, Edward Norris, Elizabeth Butler, Henry Hoernemann, Anna Maria Weyer, and so on.

- where these families settled in the United States, their jobs and their children

- Eduard Thoss tavern in Northern Kentucky

- info on Cincinnati Over-the-Rhine neighborhood, where so many settled

- Dierkes boys in family cemetery plot

- Henry Seeger’s cigar store, with photos and timeline, and two babies who died as infants

- Thomas Frost/Mary Wolking divorce

- Ade Thoss and the Covington Blue Sox

- possible family connection to Windthorst, Kan.

- death of Elizabeth Teipel Thoss and several of her children

- Benjamin Teipel trap-shooting invention and death

- Civil War service of Frank and Benjamin Thoss

- firefighter Raymond Norris and Newton Tea & Spice Co. Fire

- how Grandma and Grandpa met

Your list might cause you to rethink your project scope. For example, I’m seeing that I could divide up my project by family branches, breaking it down into smaller parts (and this is only part of my list).

When you know the topics you want to cover, arrange them in an order that makes sense to you. You could do chronological order, geographical order (group all information related to Germany, all immigration information, all second generation information), family branches one at a time, or some other arrangement. You could opt for a general overview then add several shorter profiles of specific ancestors or families.

Wilson shares how she thought about structure while planning her project:

One option would be maintaining individual biographies, organized in the book by birth year, generation or location. Or I could combine all biographies into a single narrative chronology, or even organize the stories by theme (women, farming, culture, etc.). I opted for the most straightforward and comprehensive order: chronological. With this approach, I gained a deeper understanding of how my ancestors’ lives developed over time, and how one event flowed into another.

Next, create an outline by organizing topics into sections or chapters. Read published family histories for examples. One of my favorites is Family by Ian Frazier.

3. Say It with Pictures

Pictures and graphs will engage your readers, help them follow complicated lineages and show what you’re talking about. “Plan as you go which pictures, documents, maps, charts and genealogical reports will best illustrate your narrative,” Morton advises.

Depending how many photos and documents you’ve found, you’ll want to winnow the options to those from key moments in your family history, selecting those that will reproduce well in the finished product. Consider adding transcriptions for hard-to-read or foreign-language documents.

Keep copyright in mind. If you plan to publish your work (including on a website), get permission from the copyright holder or owner of any images you didn’t create or that aren’t in your personal collection. For a quick read about understanding copyright laws, check out this article .

4. Get Organized and Utilize Apps

Now you’re ready to write. As you work, go over your records for families and people you’re writing about. Wilson developed a filing system that automatically sorted documents by individual. “I created a separate document for every event so I could easily insert new findings, titling each with the event, the date and the location,” she says. “I then grouped the documents into folders, one folder for each year.”

To help you organize source references, add in-text references with the title, author and page or record number in parentheses when you use information from a record, article, book or website. Also create a bibliography of sources as you go. This should include everything needed to find that source again: title, author, publisher or creator (such as the National Archives), publication date and place, website, etc.

Later, when your project is mostly complete, you can keep the in-text references, or number the references and create footnotes (short-form citations at the bottom of the page) or end notes (short-form citations at the end of a chapter). Include the bibliography at the end of your work. For help with source citations, use the book Evidence Explained by Elizabeth Shown Mills (Genealogical Publishing Co.).

You might have a writing head start if you can pull together blog posts or short essays you’ve already written about your family history. Your genealogy software or online tree might offer a timeline you can follow, or even generate a narrative report for you. For an ambitious project or if you do a lot of writing, you might invest in software such as Scrivener . Additionally, writing apps can help you create an outline, organize and edit your story.

Read: How to Create a Genealogy Source Citation

5. Generate Ideas through Prompts and Research

If you’re still having trouble knowing what to write, try answering the family history writing prompts in a book such as Stories From My Grandparent or from Family Tree Magazine . These will help you flesh out ideas and take your family stories in new directions.

Revisit your research for story ideas, and let what you find in documents inspire you. Wilson consulted books (both digital and physical) about her ancestors’ location and ethnic group, as well as documents on genealogy websites like Ancestry.com and Newspapers.com. One book on Ancestry.com contained all the church records for her ancestors, some written by her great-great-great-grandfather’s best friend.

Wilson also revisited local histories and newspapers she had found early in her project. “Now that I was further in my research, I recognized more names and better understood the relationships among them,” she says. “People I had dismissed as “townsfolk” turned out to be in-laws and close friends of my lineal ancestors.”

6. Seek Out Help

Look for writers’ groups and classes in your community. From online groups to friends and family members, having a community you can rely on for feedback and encouragement is essential.

Reaching out can also lead to new research finds, important for sourcing the details in your stories. Wilson connected with other family historians, as well as genealogical societies and libraries (who scanned entire chapters of reference books for her to consult). One cousin-in-law even sent her photos and a relevant family keepsake they found on eBay.

7. Begin in the Middle

Don’t let the “how to start” roadblock stall your project right out of the gate. If you don’t know how to begin, just start writing a story you like—maybe it’s about an ancestor’s immigration, military service or venture to the wrong side of the law. The words will flow from there.

“My goal wasn’t perfection, just to get memories on the page,” Wilson says about her first step of writing family biographies. “I didn’t waste time checking spelling and grammar—that would come later.” An interesting or dramatic event is often the best way to begin a story, anyway. Remember, you’re not carving in stone: You can always rearrange things later.

8. Write Naturally

If you’re writing for relatives, pretend you’re telling your family story to a friend. If you’re writing for a publication, tailor your work to that publication’s style.

Wilson had to wrestle with how to balance facts she found in her research with storytelling. “I thought of how much I hated history class growing up—all those names-places-dates to memorize, and no story to latch onto,” Wilson says. “I resolved to … strive for historical accuracy without resorting to the dry tone of a textbook.”

9. Take Your Time

A deadline can motivate you, but give yourself plenty of time. You want this project to add fulfillment to your family research, not cause stress. Start now and work on your writing project a little at a time, once a week or every evening if you can manage it. Imagine where you’ll be a year from now.

A version of this article appeared in the December 2018 issue of Family Tree Magazine , written by Diane Haddad. Sophia Wilson’s article on the steps she took to write her family history narrative appeared in the March/April 2022 issue of Family Tree Magazine .

Related Reads

Editors of Family Tree Magazine

related articles

7 creative forms for sharing your family history.

Storytelling, Writing

How to create an outline for writing an interesting family history.

Storytelling

How to share family history stories on the big genealogy websites.

Ancestry, FamilySearch, MyHeritage, Storytelling

10 story-building strategies from the finding your roots team.

.png)

Tips for Writing Family History

When you find your family history, you should consider writing it down for others to read- especially your own family. Along with simply knowing about ancestors, writing family history can be a gift to present and future gen e rations.

Family History Writing Mistake to Avoid: Telling Only Happy Family Stories

Fight Modernity's Flawed Perception of the Past - Write Your Family History

A Gentle Approach to Perfecting Your Family Histories

Reveal Amazing Genealogy Research Clues Via Timelines

Improve Your Family History With These Passive Voice Checkers

3 Pro Writing Tips DRAMATICALLY Changed My Family History

Ancestry StoryMaker Studio: Unleash Your Storytelling Potential

We're All Storytellers: Writing Family History Joyfully

Quickly Transform Your Family History With Boxed Text

Improve Writing Skills By Serving the US World War II Fallen - Stories Behind The Stars

Writing Family History Quickly: Unleash Your Creativity with Story Projects

Avoid Plagiarism While Crafting Engaging Family Histories

Even more writing tips

The Non-Writers Writing Guide to Write Your Family History

Share this post.

- ancestral stories , family history , family stories , preserving discoveries , story crafting , storytelling

I’ve heard from many of you that you don’t write your family history because you either don’t feel confident with your writing skills or aren’t sure how to start.

You aren’t alone. Many other family historians have felt the same way, including me.

Genealogy documentaries have set a bar high for storytelling. They explore rich, exciting histories and tell them in the perfect setting. How can you compete with that?

And that old saying about “everyone has a book inside them”? Pffft. You aren’t sure you have enough to fill a Christmas card.

A few years ago, I decided to put together a “This is your life” heritage book for my mother. Knowing that writing wasn’t my strong suit, I had multiple contributors lined up to share their stories. This book was going to practically write itself.

Four weeks before B-Day, most of the people who agreed to write something pulled out. I had no stories, and I’d never written anything longer than a multiple page letter. I wasn’t up for the task. However, I promised my siblings we’d have a book for Mum’s birthday, so we were going to have a book.

The next few weeks weren’t pretty, but we handed Mum a 188-page hardcover book in a custom slipcase on her birthday.

The hardest part is starting. I probably never would have if I hadn’t made a promise to deliver a book to Mum.

You can do it too. Even if you:

- think you’re not creative

- haven’t written more than a Christmas card in years

- don’t consider yourself a writer.

Techniques to use to write your family history

As a non-writer full of self-doubt, I tried every shortcut I read about it, even those AI writing sites. None worked. Why? Because the story comes from you.

It’s the knowledge you’ve gained from years of research, the theories you’ve developed and the insight you have after hours of analysis that creates the story. U nfortunately, there is no AI writing app or “fill-in-the-blanks” template that can do that for you.

However, there are different techniques you can use to share what you’ve discovered and create a book, a blog or a binder of stories for your descendants to enjoy.

The first step is to reframe what you tell yourself to take the pressure off. Don’t aim to be a writer, instead consider yourself a storyteller. As a storyteller, you don’t need to be a writer; you’re just documenting what you’ve discovered to share with others.

The next step is to experiment with these three options to write your family stories.

Commit to trying at least one but preferably all of them. You don’t have to show your work to anyone until you are ready. The best way to gain confidence in a skill is to practice.

1. Say it out loud

Skip the writing step and tell yourself the story while using a voice-to-text app to record it.

You want to feel comfortable while talking and for the story to come out naturally. So, if it feels a bit weird talking to yourself, then tell the account to a relative, pet or even your favourite plant. The critical part is that you use your computer or phone to record and convert each word to text as you say it.

Voice-to-text software isn’t perfect, so expect to see some errors in the draft that is created. Mistakes usually happen when the AI misinterprets what you’ve said, mainly when talking too fast, using slang or local colloquialisms. So rather than fixing the issues on the go, finish the draft and correct any errors in editing.

Be sure to speak slowly and clearly so that the microphone picks up your voice, and the AI can interpret and convert each word as you say it.

You don’t need any fancy apps or software to get started. Instead, try any note-taking app on your phone, hit the microphone icon near the space bar, and start talking.

Speak the punctuation that you want to include, such as:

- question mark

- exclamation point.

To include quotation marks, you’ll say:

- close quote.

For single quotes, you’ll say:

- open single quote

- close single quote.

To move to the following line, say either:

- new paragraph.

Depending on the app you use, saying “new line” or the alternatives may exit you from the voice-to-text functionality. If that happens, press the microphone icon again to keep “typing”.

Note-taking apps for writing from your smartphone

Look for an app that saves the document in the cloud (e.g. Dropbox, Google Drive, OneDrive etc.) so that you can easily access it from any device or computer. Such as:

- Microsoft Word

2. Summarize each discovery as you make it

Don’t overthink the process and build your ancestor’s story by crafting a summary of each discovery you make.

Everything you uncover represents an event that happened in your ancestors’ life, from being born, getting married, moving house or enrolling in the military. So capturing your interpretation of that event builds their story one discovery at a time.

Your ancestor’s story isn’t only repeating the facts you discovered, such as date of birth, place of marriage or their final resting place. It’s also your interpretation of the discovery and how that event connects to the other things that you know about them. That includes your thoughts, theories and questions that come up as you’re reviewing each discovery.

If you already have an analysis process for your genealogy research, re-purpose the summary you’re already writing for each discovery.

Not summarising your discoveries? Start now. Review what you know about each ancestor and write a few paragraphs on it, using the questions below to prompt you.

- When did this event happen?

- Where did it take place?

- What happened?

- Which other ancestors were involved in the event?

- How does this discovery answer any of the questions you have about this ancestor?

- How does it connect to what you already know about them?

- What was your key learning?

- What new questions do you have after reading this discovery?

- Does this confirm any existing theories or inspire new ones?

- What new clues do you have to research?

Don’t overthink it; write your thoughts for each question. When you’re done, that’s a block of text towards the draft of your ancestor’s story.

Find out more about discovery analysis and crafting summaries.

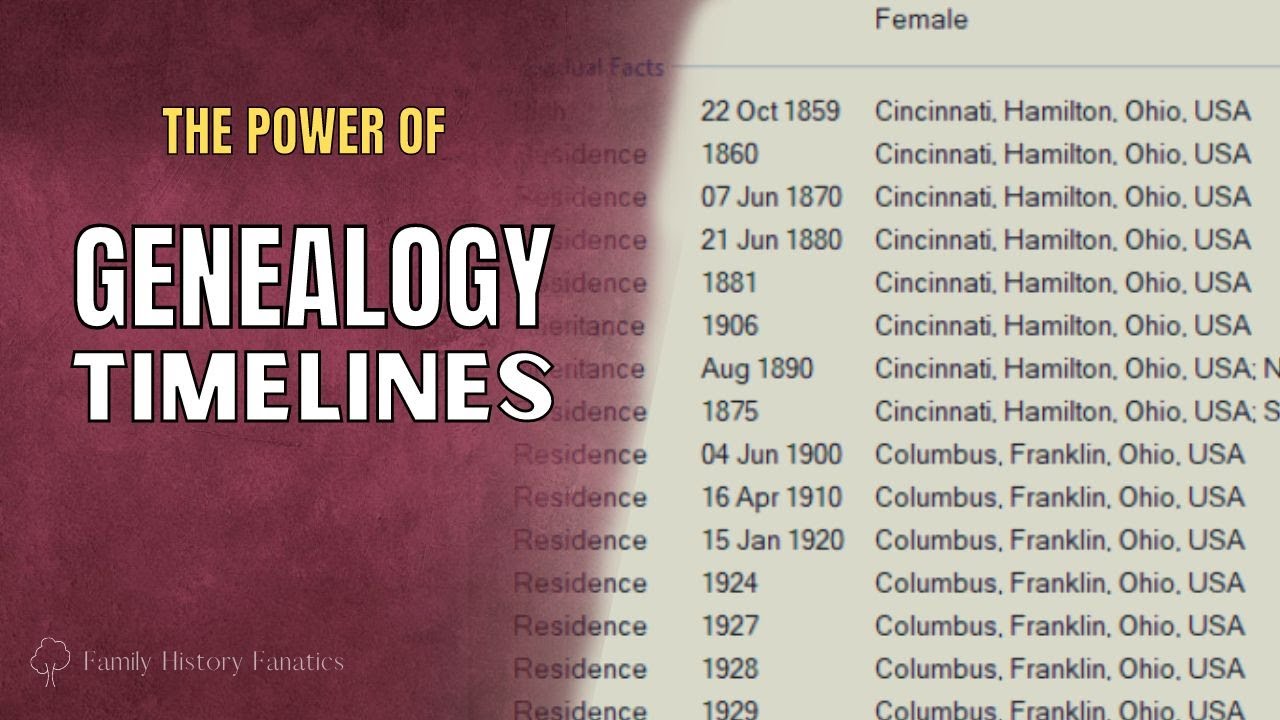

3. convert your ancestral timeline into story format.

Your ancestral timelines are the story outline of your ancestor’s lives.

If you’re not already using timelines, this is a great time to start. Of course, your genealogy software will already be creating one as you log each discovery. But it’s also easy to create your own.

Create a timeline in Microsoft Word, Google Docs or your favourite app. Any note-taking app will work as long as you can create a hierarchy using headings, body text and bullet points.

Don’t overthink the process because that overwhelms you and stops you from writing your ancestor’s story. Keep it simple and try something like this process:

- Add each year of your ancestor’s life

- Underneath each year, including the date

- After the event date, add the event’s name (for example, death of father, left school etc.)

- Use bullet points to summarise what happened

Don’t have any events? Include general historical events such as war, major financial or weather events instead. You can also include this type of information even if it’s a year where you have events in your ancestor’s life.

Once you’ve finished with the outline, go back through each event, and convert the facts into paragraphs. Be sure to include any theories or questions this event raised for you so that your reader can go on the journey with you.

When you’re done converting each event into a few paragraphs, you’ll have a draft of your ancestor’s story.

You can write your family history even if you’re not a writer

You don’t need to be Stephen King, Nora Roberts or Agatha Christie to write your family stories. Your family history is your story to tell and should be done in your voice.

Keep the process simple, and don’t overthink it, as that’s when the doubts creep in. All you need to do is tell your reader

- what you’ve discovered

- your theories

- questions you have

- how it connects to other things.

“Inside each of us is a natural-born storyteller just waiting to be released.” Robin Moore, Awakening the Hidden Storyteller

Experiment with different ways of creating the first draft.

- Use voice-to-text functionality to convert the story to text as you talk.

- Analyse and summarise each discovery to build the draft one block at a time.

- Convert your ancestral timelines into paragraphs to capture your ancestor’s story.

The best advice I have is to start. You don’t have to ever show those first few paragraphs to anyone. You may surprise yourself, though. Once you see the sections adding up and the story coming together, then you’ll be keen to share it with your loved one.

After all, stories are written one sentence, one word at a time.

Ready for your next step?

Ready to dive deep into my non-writers writing formula and convert your research into engaging stories? Learn more about the Ancestral Stories course .

Discover more

Your daily dose of inspiration

Organise your genealogy discoveries, track what you’ve found and decide where to look next.

- © 2016-2024 The Creative Family Historian • All rights reserved.

How to Write Your Family History

- Genealogy Fun

- Vital Records Around the World

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

Choose a Format

Define the scope, set realistic deadlines.

- Choose a Plot and Themes

Do Your Background Research

- Don't Be Afraid to Use Records and Documents

Include an Index and Source Citations

- Certificate in Genealogical Research, Boston University

- B.A., Carnegie Mellon University

Writing a family history may seem like a daunting task, but when the relatives start nagging, you can follow these five easy steps to make your family history project a reality.

What do you envision for your family history project? A simple photocopied booklet shared only with family members or a full-scale, hard-bound book to serve as a reference for other genealogists? Perhaps you'd rather produce a family newsletter, cookbook, or website. Now is the time to be honest with yourself about the type of family history that meetings your needs and your schedule. Otherwise, you'll have a half-finished product nagging you for years to come.

Considering your interests, potential audience, and the types of materials you have to work with, here are some forms your family history can take:

- Memoir/Narrative: A combination of story and personal experience, memoirs, and narratives do not need to be all-inclusive or objective. Memoirs usually focus on a specific episode or time period in the life of a single ancestor, while a narrative generally encompasses a group of ancestors.

- Cookbook: Share your family's favorite recipes while writing about the people who created them. A fun project to assemble, cookbooks help carry on the family tradition of cooking and eating together.

- Scrapbook or Album: If you're fortunate enough to have a large collection of family photos and memorabilia, a scrapbook or photo album can be a fun way to tell your family's story. Include your photos in chronological order and include stories, descriptions, and family trees to complement the pictures.

Most family histories are generally narrative in nature, with a combination of personal stories, photos, and family trees.

Do you intend to write mostly about just one particular relative, or everyone in your family tree ? As the author, you need to choose a focus for your family history book. Some possibilities include:

- Single Line of Descent: Begin with the earliest known ancestor for a particular surname and follows him/her through a single line of descent (to yourself, for example). Each chapter of your book would cover one ancestor or generation.

- All Descendants Of...: Begin with an individual or couple and cover all of their descendants, with chapters organized by generation. If you're focusing your family history on an immigrant ancestor, this is a good way to go.

- Grandparents: Include a section on each of your four grandparents, or eight great-grandparents, or sixteen great-great-grandparents if you are feeling ambitious. Each individual section should focus on one grandparent and work backward through their ancestry or forward from his/her earliest known ancestor.

Again, these suggestions can easily be adapted to fit your interests, time constraints, and creativity.

Even though you'll likely find yourself scrambling to meet them, deadlines force you to complete each stage of your project. The goal here is to get each piece done within a specified time frame. Revising and polishing can always be done later. The best way to meet these deadlines is to schedule writing time, just as you would a visit to the doctor or the hairdresser.

Choose a Plot and Themes

Thinking of your ancestors as characters in your family story, ask yourself: what problems and obstacles did they face? A plot gives your family history interest and focus. Popular family history plots and themes include:

- Immigration/Migration

- Rags to Riches

- Pioneer or Farm Life

- War Survival

If you want your family history to read more like a suspense novel than a dull, dry textbook, it is important to make the reader feel like an eyewitness to your family's life. Even when your ancestors didn't leave accounts of their daily lives, social histories can help you learn about the experiences of people in a given time and place. Read town and city histories to learn what life was life during certain periods of interest. Research timelines of wars, natural disasters, and epidemics to see if any might have influenced your ancestors. Read up on the fashions, art, transportation, and common foods of the time. If you haven't already, be sure to interview all of your living relatives. Family stories told in a relative's own words will add a personal touch to your book.

Don't Be Afraid to Use Records and Documents

Photos, pedigree charts, maps, and other illustrations can also add interest to family history and help break up the writing into manageable chunks for the reader. Be sure to include detailed captions for any photos or illustrations that you incorporate.

Source citations are an essential part of any family book, to both provide credibility to your research, and to leave a trail that others can follow to verify your findings.

- Celebrate Family History Month and Explore Your Lineage

- Scrapbooking Your Family History

- 5 Great Ways to Share Your Family History

- Fun Family History Activities for Family Reunions

- Tracing Your Family Medical History

- 8 Places to Put Your Family Tree Online

- Best Things to Make With Desktop Publishing Software

- How Are Cousins Related?

- Creating a Digital Scrapbook on Your Computer

- Publishing Your Family History Book

- 10 Fabulous Sources for Family History Books Online

- Filling out Genealogical Forms

- Make Your Own Family Photo Calendar

- Make a Memory Book for Your Family

- Family Tree Lesson Plans

- Researching Famous (or Infamous) Ancestors

How to Go From Boring to Brilliant Family History Writing

So, you’ve done so much family history research that you’re drowning in facts and you’ve decided – that’s it – I’ve got to start writing some of this up!

Only now you are stuck. Don’t worry, you are not alone.

Unless you’re a bit of a Marvin (from Hitchhikers Guide To The Galaxy) you are probably perfectly fine at telling stories. I mean, we tell snippets of stories all the time, whether it’s moaning to the postman about our encounter with a grumpy lady in Tesco’s. Or explaining our Great-Grandfather to our 3rd cousin twice removed. We tell stories daily.

It’s often only when we come to write these stories down that we struggle. We can’t find the “right” words. We lose our voice. We get bogged down in details. We forget about our core story. The thing that made us want to tell it in the first place. We either stare at a blank white page, unable to even start writing OR we write tons of words – read them back and decide we’d like to delete the lot.

In this article, I’ll share some tips that’ll transform your family history writing. I’m not saying you are going to become a world-renowned author. We’re not all JK Rowling. But, when you give your cousin Sue the story about your great-gran, you can be sure she’ll read it, enjoy it and therefore remember it.

Table of Contents

Before you start writing your family history, decide your audience.

Sometimes our audience is clear, such as I’m writing this for my children. But, we don’t always have a particular person in mind. You may be writing up your family history for fun, to check for gaps in your research, as ‘cousin bait’, as a blog for fellow genealogists or professional reasons.

That’s fine, but you need to try to imagine who might be reading. Let’s use my blog post on my Woodrow witch ancestor as an example. It could attract unknown cousins, fellow genealogists or person’s interested in family history. It might attract those that like reading true stories.

These readers all have some things in common. They are unlikely to be children. They are likely to enjoy history. Yet, some readers may have lots of family history knowledge, others none at all. I need to ensure I don’t alienate anyone. For example, I use language appropriate to their reading age but without jargon.

Envisioning your audience, their likes and dislikes will help inform your writing.

Decide On The Message For Each Piece of Family History Writing

Your writing doesn’t have to have a deep and meaningful message. But, it does have to have some sort of point. For example, my blog post ‘ Blue Blood ‘ explores my illegitimate ancestor. I wanted to make my research journey clear and to inform readers of the parentage of my ancestor. That was my message. Whereas, my blog post ‘A Hidden Victim of Ripper Mania ‘ had a statement at its heart. I wanted to use my ancestor’s story to explore the effect of constricted gender roles. I wanted to show her story of suicide as a possible consequence of Victorian rigidity.

Regardless of whether your message is divisive, exploratory or informative, decide it before you start. Don’t let it get lost or diluted. Keep checking on your message. Are you getting to the point? Is it clear?

Set A Plan & Avoid Tangents

Before writing your family history make a plan. Exactly which ancestors are you going to cover? Over what time? Who will you start with? How will you break up their story? How does this plan work with your decided audience? Where will you show your message?

Setting a plan will give your writing structure. It’ll ensure you cover all the points you want to explore. It’ll ensure your message comes through. It’ll help you weed out or avoid random tangents.

Odd pieces of off-topic text can be very distracting. It’s easy to fall into a trap of including things because they are ‘interesting’. This is an error. Adding random pieces of content dilutes your story. It starts to feel rambling and the message becomes lost.

Writing Your Family History

If you can't write it, say it.

One of my favourite writing styles, especially for short stories, is ‘conversational’. I like to feel like the writer is sat next to me, sharing their tale over a cuppa. That’s not always easy to emulate. So cheat! Record yourself whilst you explain the story.

You don’t need anything fancy to do this. Download the free app Otter ( Google Play or Apple Store ) onto your phone. This nifty programme will listen to you talk and convert your words into text. It’s not perfect but its accuracy is impressive.

Next, take that speech-to-text and edit it. Use it as a starting point and build upon it.

Pay special attention to the words you use or turns of phase. This is your real voice. Use those phases in your family history writing to make it feel more authentic.

Use Endnotes or Footnotes to separate your family history writing from sources

You don’t have to put all your details within the body of the text. I have read a lot of family histories that start like this:

“My ancestor, John Brown was born on 5th June 1857. He was christened on 10 June 1857 in St Michael’s Church, Basingstoke. His older brother, Thomas was christened on the same day. Thomas was born on 20th March 1855.”

For an instant win, try putting some of those details in footnotes or endnotes, alongside any source information. Doing so transforms our sentence, to something like this:

“John and his older brother Thomas were both christened in the summer of 1857 at St Michael’s Church, Basingstoke.”

Bring Your Family History Writing To Life

Reading a list of facts is boring. We need details to help spark our imagination. Writing family history is challenging because we need both accuracy and imagination.

Let’s look at our 1857 christening example. It took place in the summer and it’d be easy to presume that the weather was hot. We need to check though! That June may have been infamous for its terrible weather.

Our example took place in a church. We may look at a photo of that stone building and presume it looked the same way in 1857. Again we need to check. What if the church flooded that year? What if the building we see today is a replica?

Once we’ve got our confirmed details though, we can use them to create texts rich in detail:

“Summer 1857 was hot and the parishioners of St Michael’s Church must have felt relieved to sit within the cool of the church’s thick stone walls. On 10th June the Brown family filled the congregation. A generation of bottoms squashed into the tiny pews. I imagine the new Brown babies (Thomas and John) cried as the icy holy water splashed onto their foreheads. Three years before them, a daughter had been baptised using that same deep stone font. Her little bottom was missing from the row of Browns that watched the ceremony. Perhaps her mother, Elizabeth was thinking of her as she hushed her son’s bawl…”

Find The Right Words

Successful authors tend to have a fantastic vocabulary. Reading widely can help you to expand your own. But, you can also use a thesaurus to aid you – especially if you find you are using the same words repetitively. There are loads of free thesaurus’ online.

It is also worth bearing in mind that old adage, “show not tell”. If you find your text is full of adjectives (describing words) then start pruning them! Replacing those adjectives with strong nouns can actually enhance your writing.

I recommend reading “ Kill Your Adjectives “. It really explains this concept in much more detail and gives some great examples.

Use Tech To Help With Grammar

Even the very best of writers make mistakes. That’s why they have proof readers and editors. Now, whilst using a real-life person is always best, that’s not always possible. So, use apps to try to fill the gap. Hemingway is a free editor. Type in your text and using various colours, it’ll highlight sections that use a passive voice or are hard to read. It’ll point out your use of adverbs too. Fixing these errors will lead to better writing.

Other apps that can help include, Grammarly (a free app or chrome extension). It will point out all your spelling and grammatical errors. Underlined. In red. I hate it. I love it. It’s one of those kinds of relationships.

Editing and Proof-Reading

Apps aside, nothing beats a human eye on your work. In an ideal world, once completed, put your writing away. Leave it for at least a couple of weeks before you pick it up and start editing. Then finally hand it to someone else to read. Proof-reading is a talent. It’s why people get paid to do it! So, do what you can. Pass it to who you can. Don’t beat yourself up if 3 months later you look at it again and there’s an apostrophe in the wrong place.

Enhance Your Family History Writing

An image is worth 1000 words.

Those of us writing up our family history today have a huge advantage over our ancestors. We have the mighty power of the internet. Within seconds we can have access to quality photographs to add to our work.

Use images to “back up” the detail you’ve written or to separate large pieces of writing. These don’t have to be images of your ancestors. Use photos of buildings, maps, artwork, newspapers. Mix it up!

On a practical note, ensure you are not breaking any copyright laws. On Google Images select Settings-Advanced Search and filter by ‘Usage Rights’ to find images marked as shareable. Read the different levels of copyright and attribute your images as appropriate. If in doubt, check with whoever owns the image before you use it. If you can’t find someone to ask and are still unsure, then don’t use it. And yes, I know exactly how frustrating that can be!

Geograph is great for free images of places and buildings within the UK. You can also utilise sites like Unsplash , Pixabay and Pexels to find free pictures. Use Canva to curate your own images and text graphics.

Add Charts To Your Family History Writing

Make use of another advantage available to modern genealogists. Create and add family tree diagrams to your text. These not only break up long passages but make the text itself easier to follow. Use charts to explain genetic relationships. Create these either within your family tree package or using Microsoft PowerPoint or Excel, or your Mac or Google equivalent.

Break Up Your Family History Writing

Depending on the length of your family history writing, consider using tools to make it easier to navigate. Very long works benefit from contents pages and indexes. All easily created in Word.

Shorter pieces may benefit from section breaks and sub-headings.

Give It A Title

People make snap decisions about what to read. Give your text the very best chance by giving it a great title. Use the Headline Analyser to see which of your ideas is worth pursuing. Or browse these 100+ blog title ideas to get your creative juices flowing.

Do You Enjoy Writing Your Family History Stories?

Writing up your family history should be enjoyable. Be honest with yourself. If writing your family history feels like a form of torture then don’t do it! It’ll come through in your writing anyway. Writing up your ancestors’ lives is not the only method of recording their histories. You could simply do some oral recordings. You could try making a presentation.

Or you could join my Curious Descendants Club! With regular workshops and challenges, this Club is designed to help you write your family history. You can find all the details here, including testimonials from existing members .

Stay in touch...

I send semi-regular emails packed with family history writing tips, ideas and stories. Plus you’ll never miss one of my articles (or an episode of #TwiceRemoved) ever again.

STAY IN TOUCH

Never miss a blog post or an episode of #TwiceRemoved ever again. Plus get semi-regular family history writing tips delivered straight to your inbox. All for FREE!

More Posts:

- Write Your Family History With Style

- Why Everyone Should Write Their Family History

- #TwiceRemoved with Matthew Roberts

- #TwiceRemoved with Justin Bengry

- 5 Tips to Make The Most of Genealogy Research Rabbit Holes

Purchases made via these links may earn me a small commission – helping me to keep blogging!

Read my other articles

The learning centre.

- CURIOUS DESCENDANTS CLUB

Start writing your family history today. Turn your facts into narratives with the help of the Curious Descendants Club workshops and community.

TALKS & WORKSHOPS

Looking for a guest speaker? Or a tutor on your family history course? I offer a range of talks with a focus on technology, writing and sharing genealogy stories.

HOW I CAN HELP

- TALKS & WORKSHOPS

- [email protected]

CONNECT WITH ME

Copyright © 2020 Genealogy Stories | All Rights Reserved | Privacy Policy | Cookies

Privacy Overview

Get semi-regular emails packed with family history writing challenges, hints, tips and ideas. All delivered straight to your inbox FREE! Never miss a blog posts or episode of #TwiceRemoved ever again.

p.s. I hate spam so I make sure that you can unsubscribe from my emails at any time (or adjust your settings to hear more / less from me).

- SOCIAL SECURITY DEATH INDEX

How to Write a Family History

Writing a family history is an enlightening process that will help you form an appreciation of your heritage and the characters who helped forge it. On one hand, you’re playing detective: immersing yourself in research and stumbling upon discoveries. On the other, you’re a storyteller: gold mining for the ingredients of a rich narrative through the lives of your ancestors.

It is a highly rewarding exercise both for you and for your next of kin, who will benefit from your findings. That said, the act of writing your family history isn’t all glamor. Not all genealogists have a natural knack for storytelling. In unpacking how to write a family history, we wish to present a simple structure to serve as a guideline for what we promise will be a worthwhile process.

Do Your Research

Before you can start the process of writing your family history, you must immerse yourself in family research. Depending on the amount of ancestral data that you have access to, you may want to grab from a number of sources and throw yourself into a variety of records, archives, and articles in order to piece together the puzzle of your heritage. Genealogy records that you might want to search when tracing your family history include:

- U.S. Census records

- Newspaper archives

- Family stories and diaries

- Court records

- Congressional records for private claims

- Military records

- Passport applications

Newspaper archives are an invaluable resource for finding facts and stories about your ancestors that have been lost over time. From marriage and birth announcements to long-lost family photos to articles about local events, you’ll learn more from old newspapers than just names and dates. In newspaper archives you can also find obituaries to learn more details about your ancestors’ lives, and many obituaries include photos and mentions of related family members.

Another powerful genealogy resource for compiling data for your family story are U.S. Census Records . The Federal Census can help track down valuable information and serve as a direct tool connecting you to deceased relatives.

Additional Records for Writing a Family History

Government records are another centerpiece to tracing your family history. Understanding your family timeline through clues deducted from land deeds or cemetery maps is a key research tool. Also, finding widows’ claims or war pension records can help to decipher accurate dates and length of life.

Choose a Writing Style