- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

The Writing Assignment That Changes Lives

Anya Kamenetz

Why do you do what you do? What is the engine that keeps you up late at night or gets you going in the morning? Where is your happy place? What stands between you and your ultimate dream?

Heavy questions. One researcher believes that writing down the answers can be decisive for students.

He co-authored a paper that demonstrates a startling effect: nearly erasing the gender and ethnic minority achievement gap for 700 students over the course of two years with a short written exercise in setting goals.

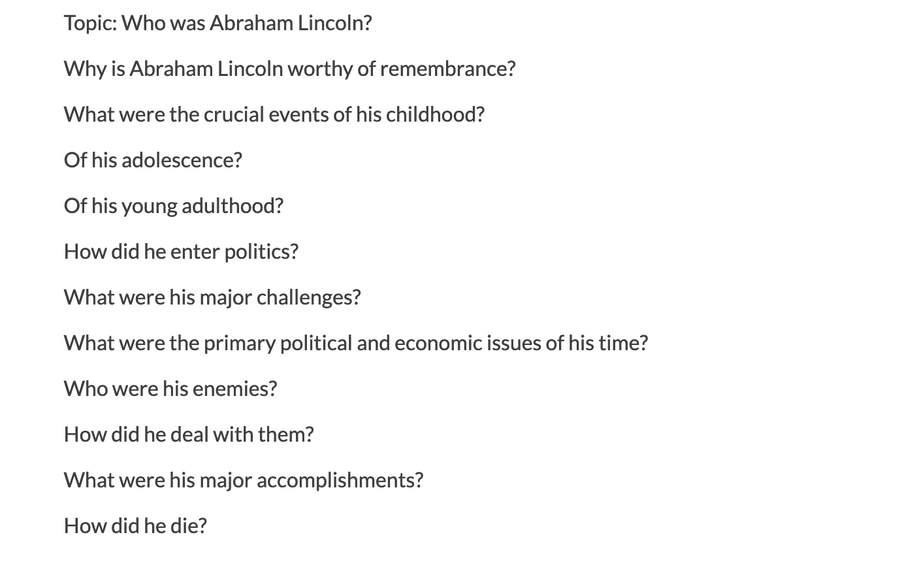

Jordan Peterson teaches in the department of psychology at the University of Toronto. For decades, he has been fascinated by the effects of writing on organizing thoughts and emotions.

Experiments going back to the 1980s have shown that "therapeutic" or "expressive" writing can reduce depression, increase productivity and even cut down on visits to the doctor.

"The act of writing is more powerful than people think," Peterson says.

Most people grapple at some time or another with free-floating anxiety that saps energy and increases stress. Through written reflection, you may realize that a certain unpleasant feeling ties back to, say, a difficult interaction with your mother. That type of insight, research has shown, can help locate, ground and ultimately resolve the emotion and the associated stress.

At the same time, "goal-setting theory" holds that writing down concrete, specific goals and strategies can help people overcome obstacles and achieve.

'It Turned My Life Around'

Recently, researchers have been getting more and more interested in the role that mental motivation plays in academic achievement — sometimes conceptualized as "grit" or "growth mindset" or "executive functioning."

Peterson wondered whether writing could be shown to affect student motivation. He created an undergraduate course called Maps of Meaning. In it, students complete a set of writing exercises that combine expressive writing with goal-setting.

Students reflect on important moments in their past, identify key personal motivations and create plans for the future, including specific goals and strategies to overcome obstacles. Peterson calls the two parts "past authoring" and "future authoring."

"It completely turned my life around," says Christine Brophy, who, as an undergraduate several years ago, was battling drug abuse and health problems and was on the verge of dropping out. After taking Peterson's course at the University of Toronto, she changed her major. Today she is a doctoral student and one of Peterson's main research assistants.

In an early study at McGill University in Montreal, the course showed a powerful positive effect with at-risk students, reducing the dropout rate and increasing academic achievement.

Peterson is seeking a larger audience for what he has dubbed "self-authoring." He started a for-profit company and is selling a version of the curriculum online. Brophy and Peterson have found a receptive audience in the Netherlands.

At the Rotterdam School of Management, a shortened version of self-authoring has been mandatory for all first-year students since 2011. (These are undergraduates — they choose majors early in Europe).

The latest paper, published in June, compares the performance of the first complete class of freshmen to use self-authoring with that of the three previous classes.

Overall, the "self-authoring" students greatly improved the number of credits earned and their likelihood of staying in school. And after two years, ethnic and gender-group differences in performance among the students had all but disappeared.

The ethnic minorities in question made up about one-fifth of the students. They are first- and second-generation immigrants from non-Western backgrounds — Africa, Asia and the Middle East.

While the history and legacy of racial oppression are different from that in the United States, the Netherlands still struggles with large differences in wealth and educational attainment among majority and minority groups.

'Zeroes Are Deadly'

At the Rotterdam school, minorities generally underperformed the majority by more than a third, earning on average eight fewer credits their first year and four fewer credits their second year. But for minority students who had done this set of writing exercises, that gap dropped to five credits the first year and to just one-fourth of one credit in the second year.

How could a bunch of essays possibly have this effect on academic performance? Is this replicable?

Melinda Karp is the assistant director for staff and institutional development at the Community College Research Center at Teachers College, Columbia University. She leads studies on interventions that can improve college completion. She calls Peterson's paper "intriguing." But, she adds, "I don't believe there are silver bullets for any of this in higher ed."

Peterson believes that formal goal-setting can especially help minority students overcome what's often called "stereotype threat," or, in other words, to reject the damaging belief that generalizations about ethnic-group academic performance will apply to them personally.

Karp agrees. "When you enter a new social role, such as entering college as a student, the expectations aren't always clear." There's a greater risk for students who may be academically underprepared or who lack role models. "Students need help not just setting vague goals but figuring out a plan to reach them."

The key for this intervention came at crunch time, says Peterson. "We increased the probability that students would actually take their exams and hand in their assignments." The act of goal-setting helped them overcome obstacles when the stakes were highest. "You don't have to be a genius to get through school; you don't even have to be that interested. But zeroes are deadly."

Karp has a theory for how this might be working. She says you often see at-risk students engage in self-defeating behavior "to save face."

"If you aren't sure you belong in college, and you don't hand in that paper," she explains, "you can say to yourself, 'That's because I didn't do the work, not because I don't belong here.' "

Writing down their internal motivations and connecting daily efforts to blue-sky goals may have helped these young people solidify their identities as students.

Brophy is testing versions of the self-authoring curriculum at two high schools in Rotterdam, and monitoring their psychological well-being, school attendance and tendency to procrastinate.

Early results are promising, she says: "It helps students understand what they really want to do."

How to Write an Essay - The Jordan Peterson Writing Template

qualiablog.com

79.6K reads

Problem Solving

Communication

Reading & Writing

Personal Development

Learn more about problemsolving with this collection

Productivity Systems

How to set achievable goals

How to create and stick to a schedule

How to break down large projects into smaller manageable tasks

Discover 46 similar ideas in

It takes just

6 mins to read

JORDAN PETERSON

8.77K reads

The Levels of Resolution

An essay exists at multiple levels:

- The choice of words

- The formation of sentences

- The arrangement of sentences in a paragraph

- The arrangement of paragraphs in a logical progression, beginning to end

- The essay as a whole

A good essay works at every one of those levels simultaneously.

6.96K reads

Step 1: Choose Topic, Read & Take Notes

Writing begins with these 3 steps:

- Pick a topic: because your essay should answer a central question.

- Make a reading list: You should aim to read 5-10 books before you write an essay. And plenty of online sources.

- Take Notes: of everything that catches your attention.

Step 2: Make an Outline

The outline is the skeleton of the essay and provides its structure.

An essay that is 1,000 words requires a 10 sentence outline.

7.36K reads

Jordan Peterson's Rules of Thumb for Note Taking

- Take note of anything that catches your attention.

- Don't highlight or underline . (That doesn't work.)

- Read a bit, then write down what you have learned or any questions that arise.

- Take about 2 to 3 times as many notes by word as you will need for your essay.

Step 3: Write Paragraphs

Use your notes. You can work back and forth between changing the outline and your sentences.

6.32K reads

Jordan Peterson's Rules of Thumb for Writing

- Your first draft should be 25% longer than your final draft. This will give you material to throw away during the editing process.

- Each paragraph in your final draft should be about 10 sentences or 100 words long. If your paragraph is much shorter than this, that is a sign that your idea isn't substantial enough. If your paragraph is much longer, it's a sign you have multiple ideas going and need to split them into separate paragraphs.

5.84K reads

Step 4: Edit Your Sentences

Working paragraph by paragraph, take each one of your sentences and write a better version of it.

Peterson advises you place each sentence on its own line and write the revised version underneath.

5.27K reads

Jordan Peterson's Editing Advice

- Make your sentences shorter , eliminating all unnecessary words. U should cut each sentence by 15-25%.

- Make sure each word is precisely the right word to express your meaning. Don't use vocabulary you haven't fully mastered.

- Read each sentence aloud and listen to how it sounds. If it sounds awkward, try saying it a different way, then write that down.

4.81K reads

Steps 5&6: Reorder Sentences & Paragraphs

Within each paragraph, see if your sentences are in the best possible order. Get rid of any sentences that are no longer necessary.

Same for paragraphs: They should help the essay flow in the best, most logical progression. Move the corresponding paragraphs until they are in the most appropriate order.

Step 7: Make a NEW Outline

After finishing your first draft: write a NEW outline of 10-15 sentences. DON'T LOOK BACK AT YOUR ESSAY WHILE YOU DO THIS!!!

The purpose of this step is to force yourself to reconstruct your argument from memory. Generally, when you remember something, you simplify it and retain only what is most important. Doing this, you will remove what is useless and keep what is vital.

Step 8,9&10: Repeat Editing & Add References & Format

To continue improving your essay, you can repeat the process of re-writing and re-ordering your sentences, re-ordering your paragraphs, and re-outlining. Add references, links, biography.

Then format it: 12pt font, tabbed idents.

4.86K reads

Jordan Peterson Writing Template

For Peterson, writing is not just a matter of fulfilling an assignment; it is a skill with deeply existential consequences.

6.98K reads

Never stop learning new things, no matter how old you are.

Related collections

Managing Email Effectively

The Art of Decision-Making

7 Books on Habits

Behavioral Economics, Explained

More like this

How to Write Strong Paragraphs

grammarly.com

How to Edit Your Own Writing

nytimes.com

How to Write Usefully

paulgraham.com

Explore the World’s Best Ideas

200,000+ ideas on pretty much any topic. created by the smartest people around & well-organized so you can explore at will., an idea for everything.

Explore the biggest library of insights. And we've infused it with powerful filtering tools so you can easily find what you need.

Knowledge Library

Powerful Saving & Organizational Tools

Save ideas for later reading, for personalized stashes, or for remembering it later.

Think Outside the Box

Lifelong learning 101.

# Personal Growth

Take Your Ideas Anywhere

Organize your ideas & listen on the go. and with pro, there are no limits., listen on the go.

Just press play and we take care of the words.

Never worry about spotty connections

No Internet access? No problem. Within the mobile app, all your ideas are available, even when offline.

Get Organized with Stashes

Ideas for your next work project? Quotes that inspire you? Put them in the right place so you never lose them.

Self-Made Billionaires Secrets

Inside the mind of elon musk.

2 Million Stashers

5,740 Reviews

72,690 Reviews

Google Play

Don’t look further if you love learning new things. A refreshing concept that provides quick ideas for busy thought leaders.

Shankul Varada

Best app ever! You heard it right. This app has helped me get back on my quest to get things done while equipping myself with knowledge everyday.

Ashley Anthony

This app is LOADED with RELEVANT, HELPFUL, AND EDUCATIONAL material. It is creatively intellectual, yet minimal enough to not overstimulate and create a learning block. I am exceptionally impressed with this app!

Great interesting short snippets of informative articles. Highly recommended to anyone who loves information and lacks patience.

Ghazala Begum

Even five minutes a day will improve your thinking. I've come across new ideas and learnt to improve existing ways to become more motivated, confident and happier.

Laetitia Berton

I have only been using it for a few days now, but I have found answers to questions I had never consciously formulated, or to problems I face everyday at work or at home. I wish I had found this earlier, highly recommended!

Jamyson Haug

Great for quick bits of information and interesting ideas around whatever topics you are interested in. Visually, it looks great as well.

Giovanna Scalzone

Brilliant. It feels fresh and encouraging. So many interesting pieces of information that are just enough to absorb and apply. So happy I found this.

Read & Learn

without deep stash

with deep stash

Access to 200,000+ ideas

Access to the mobile app

Unlimited idea saving & library

Unlimited history

Unlimited listening to ideas

Downloading & offline access

Personalized recommendations

Supercharge your mind with one idea per day

Enter your email and spend 1 minute every day to learn something new.

I agree to receive email updates

Collections

Articles, advice and tutorials from the Essay team

Writing Philosophy

How to write with Essay

Advanced Features

How to use the advanced features of Essay

Tutorial Articles

A collection of articles to help a writer follow Dr. Jordan B Peterson's essay writing process using essay.app

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Jordan Peterson’s Gospel of Masculinity

By Kelefa Sanneh

Audio: Listen to this story. To hear more feature stories, download the Audm app for your iPhone.

In February, 2000, The American Journal of Psychiatry published a concise review of a not-at-all-concise book. The book, “ Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief ,” was nearly six hundred pages long, and, although it was published by the academic press Routledge, it fit neatly within no scholarly discipline. The reviewer, a sympathetic professor of psychiatry, bravely attempted to explain such forbidding phrases as “the grammatical structure of transformational mythology.” Then he admitted defeat. “Doing justice to this tome in a two-paragraph synopsis is impossible,” he concluded. “This is not a book to be abstracted and summarized.” But he expressed the hope that curious souls would nevertheless discover this curious book, and savor it “at leisure.”

Eighteen years later, the author of “Maps of Meaning,” Jordan B. Peterson, has produced a sequel, of sorts. It’s called “ 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos ,” and it has become an international blockbuster. Peterson, formerly an obscure professor, is now one of the most influential—and polarizing—public intellectuals in the English-speaking world. Lots of fans find him on YouTube, where he is an unusual sort of celebrity, a stern but mercurial lecturer who often holds forth for hours, mixing polemics with pep talks. Peterson grew up in Fairview, Canada, a small town in Northern Alberta, and he has a fondness for quaint slang; his accent and vocabulary combine to make him seem like a man out of time and out of place, especially in America. His central message is a thoroughgoing critique of modern liberal culture, which he views as suicidal in its eagerness to upend age-old verities. And he has learned to distill his wide-ranging theories into pithy sentences, including one that has become his de facto catchphrase, a possibly spurious quote that nevertheless captures his style and his substance: “Sort yourself out, bucko.”

Peterson is fifty-five, and his delayed success should give hope to underappreciated academics everywhere. For a few years, in the nineteen-nineties, he taught psychology at Harvard; by the time he published “Maps of Meaning,” in 1999, he was back in Canada—teaching at the University of Toronto, working as a clinical psychologist, and building a reputation, on television, as an acerbic pundit. His fame grew in 2016, during the debate over a Canadian bill known as C-16. The bill sought to expand human-rights law by adding “gender identity and gender expression” to the list of grounds upon which discrimination is prohibited. In a series of videotaped lectures, Peterson argued that such a law could be a serious infringement of free speech. His main focus was the issue of pronouns: many transgender or gender-nonbinary people use pronouns different from the ones they were assigned at birth—including, sometimes, “they,” in the singular, or nontraditional ones, like “ze.” The Ontario Human Rights Commission had found that, in a workplace or a school, “refusing to refer to a trans person by their chosen name and a personal pronoun that matches their gender identity” would probably be considered discrimination. Peterson resented the idea that the government might force him to use what he called neologisms of politically correct “authoritarians.” During one debate, recorded at the University of Toronto, he said, “I am not going to be a mouthpiece for language that I detest.” Then he folded his arms, adding, “And that’s that!”

Such videos reached millions of online viewers, including plenty with no particular stake in Canadian human-rights legislation. To many people disturbed by reports of intolerant radicals on campus, Peterson was a rallying figure: a fearsomely self-assured debater, unintimidated by liberal condemnation. Students staged rowdy protests. The dean of the university sent him a letter warning that his pledge not to use certain pronouns revealed “discriminatory intentions”; the letter also warned, “The impact of your behavior runs the risk of undermining your ability to conduct essential components of your job as a faculty member.” Last fall, a teaching assistant at Wilfrid Laurier University, in Waterloo, Ontario, was reprimanded by professors for showing her class a clip of one of Peterson’s debates. (The university later apologized.) The reprisals only raised Peterson’s profile, and he capitalized on the attention on his Patreon page, where devotees can pledge monthly payments in exchange for exclusive Q. & A. sessions and online courses.

Earlier this year, Peterson appeared on Channel 4 News, in Britain. The interviewer, Cathy Newman, asked what gave him the right to offend transgender people. He asked, cheerfully, what gave her the right to risk offending him . Newman paused for an excruciating few moments, and Peterson allowed himself a moment of triumph. “Ha! Gotcha,” he said. David Brooks, in the Times , said that Peterson reminded him of “a young William F. Buckley.” Tucker Carlson, on Fox News, called the exchange with Newman “one of the great interviews of all time.”

Given the popularity of these online debates, it can be easy to forget that arguing against political correctness is not Peterson’s main occupation. He remains a psychology professor by trade, and he still spends much of his time doing something like therapy. Anyone in need of his counsel can find plenty of it in “12 Rules for Life.” The book is far easier to comprehend than its predecessor, though it may confuse those who know Peterson only as a culture warrior. One of his many fans is PewDiePie, a Swedish video gamer who is known as the most widely viewed YouTube personality in the world—his channel has more than sixty million subscribers. In a video review of “12 Rules for Life,” PewDiePie confessed that the book had surprised him. “It’s a self-help book!” he said. “I don’t think I ever would have read a self-help book.” (He nonetheless declared that Peterson’s book, at least the parts he read, was “very interesting.”) Peterson himself embraces the self-help genre, to a point. The book is built around forthright and perhaps impractically specific advice, from Chapter 1, “Stand Up Straight with Your Shoulders Back,” to Chapter 12, “Pet a Cat When You Encounter One on the Street.” Political polemic plays a relatively small role; Peterson’s goal is less to help his readers change the world than to help them find a stable place within it. One of his most compelling maxims is strikingly modest: “You should do what other people do, unless you have a very good reason not to.” Of course, he is famous today precisely because he has determined that, in a range of circumstances, there are good reasons to buck the popular tide. He is, by turns, a defender of conformity and a critic of it, and he thinks that if readers pay close attention, they, too, can learn when to be which.

Like many conversion stories, Peterson’s begins with a crisis of faith—a series of them, in fact. He was raised Protestant, and as a boy he was sent to confirmation class, where he asked the teacher to defend the literal truth of Biblical creation stories. The teacher’s response was convincing neither to Peterson nor, Peterson suspected, to the teacher himself. In “Maps of Meaning,” he remembered his reaction. “Religion was for the ignorant, weak, and superstitious,” he wrote. “I stopped attending church, and joined the modern world.” He turned first to socialism and then to political science, seeking an explanation for “the general social and political insanity and evil of the world,” and each time finding himself unsatisfied. (This was the Cold War era, and Peterson was preoccupied by the possibility of nuclear annihilation.) The question was, he decided, a psychological one, so he sought psychological answers, and eventually earned a Ph.D. from McGill University, having written a thesis examining the heritability of alcoholism.

All the while, Peterson was also pursuing a grander, stranger project. He had fallen under the sway of Carl Jung, the mystical Swiss psychology pioneer who interpreted modern life as an endless drama, haunted by ancient myths. (Peterson calls Jung “ever-terrifying,” which is a very Jungian sort of compliment.) In “Maps of Meaning,” Peterson drew from Jung, and from evolutionary psychology: he wanted to show that modern culture is “natural,” having evolved over hundreds of thousands of years to reflect and meet our human needs. Then, rather audaciously, he sought to explain exactly how our minds work, illustrating his theory with elaborate geometric diagrams (“The Constituent Elements of Experience as Personality, Territory, and Process”) that seemed to have been created for the purpose of torturing undergraduates.

The new book replaces charts with cheerful drawings of Peterson’s children acting out his advice. In the foreword, Peterson’s friend Norman Doidge, a prominent psychiatrist, tells about meeting him at an outdoor lunch at the house of a mutual friend; Peterson was wearing cowboy boots, and determinedly ignoring a swarm of bees. “He had this odd habit,” Doidge writes, “of speaking about the deepest questions to whoever was at this table—most of them new acquaintances—as though he were just making small talk.”

Throughout the book, Peterson supplies small and strange interjections of autobiography. He recalls the time an old friend named Ed came to visit, accompanied by another guy who was, in Peterson’s estimation, “stoned out of his gourd.” Alarmed, Peterson staged a kind of intervention. “I took Ed aside and told him politely that he had to leave,” Peterson writes. “I said that he shouldn’t have brought his useless bastard of a companion.” Ed took his friend and left—fearing, perhaps, to discover what a less polite admonition would have sounded like.

Peterson has a way of making even the mildest pronouncement sound like the dying declaration of a political prisoner. In “Maps of Meaning,” he traced this sense of urgency to a feeling of fraudulence that overcame him in college. When he started to speak, he would hear a voice telling him, “You don’t believe that. That isn’t true.” To ward off mental breakdown, he resolved not to say anything unless he was sure he believed it; this practice calmed the inner voice, and in time it shaped his rhetorical style, which is forceful but careful. In “12 Rules for Life,” Peterson recounts a similar experience when, as a psychologist, he worked with a client diagnosed with paranoia. He says that such patients are “almost uncanny in their ability to detect mixed motives, judgment, and falsehood,” and so he redoubled his efforts to say only what he meant. “You have to listen very carefully and tell the truth if you are going to get a paranoid person to open up to you,” he writes. Peterson seems to have found that this approach works on much of the general population, too.

If he once had a tendency to shut himself up, Peterson has wholly overcome it. “Do Not Bother Children When They Are Skateboarding,” he proclaims (Rule 11), but the expected riff about “overprotected” children leads elsewhere: to a grim story about a troubled friend who committed suicide, and then to a remembrance of a professor who boasted that he and his wife had made an ethical decision to have only one child, and from there to an argument that both the unhappy friend and the arrogant professor were “anti-human, to the core.” Elsewhere in the chapter, he writes that “boys’ interests tilt towards things” and “girls’ interests tilt towards people,” and that these interests are “strongly influenced by biological factors.” He is particularly concerned about boys and men, and he flatters them with regular doses of tough love. “Boys are suffering in the modern world,” he writes, and he suggests that the problem is that they’re not boyish enough. Near the end of the chapter, he tries to coin a new catchphrase: “Toughen up, you weasel.”

When he does battle as a culture warrior, especially on television, Peterson sometimes assumes the role of a strident anti-feminist, intent on ending the oppression of males by destroying the myth of male oppression. (He once referred to his critics as “rabid harpies.”) But his tone is more pragmatic in this book, and some of his critics might be surprised to find much of the advice he offers unobjectionable, if old-fashioned: he wants young men to be better fathers, better husbands, better community members. In this way, he might be seen as an heir to older gurus of manhood like Elbert Hubbard, who in 1899 published a stern and wildly popular homily called “ A Message to Garcia .” (What young men most needed, Hubbard wrote, was “a stiffening of the vertebrae.”) Peterson is an heir, too, to the professional pickup artists who proliferated in the aughts, making a different appeal to feckless men. Where the pickup artists promised to make guys better sexual salesmen (sexual consummation was called “full close,” as in closing a deal), Peterson, more ambitious, promises to help them get married and stay married. “You have to scour your psyche,” he tells them. “You have to clean the damned thing up.” When he claims to have identified “the culminating ethic of the canon of the West,” one might brace for provocation. But what follows, instead, is prescription so canonical that it seems self-evident: “Attend to the day, but aim at the highest good.” In urging men to overachieve, he is also urging them to fit in, and become productive members of Western society.

Every so often, Peterson pauses to remind his readers how lucky they are. “The highly functional infrastructure that surrounds us, particularly in the West,” he writes, “is a gift from our ancestors: the comparatively uncorrupt political and economic systems, the technology, the wealth, the lifespan, the freedom, the luxury, and the opportunity.” This may sound strange to readers in the United States, where a widespread perception of dysfunction unites politicians and commentators who agree on little else. But Peterson does not live in Donald Trump’s America; in Canada, the Prime Minister is Justin Trudeau, who seems to strike Peterson as the embodiment of wimpy and fraudulent liberalism. Recently, after Trudeau tried to cut off a rambling questioner by half-joking that she should say “peoplekind” instead of “mankind,” Peterson appeared on “Fox & Friends” to register his objection. “I’m afraid that our Prime Minister is only capable of running his ideas on a few very narrow ideological tracks,” he said.

Peterson seems to view Trump, by contrast, as a symptom of modern problems, rather than a cause of them. He suggests that Trump’s rise was unfortunate but inevitable—“part of the same process,” he writes, as the rise of “far-right” politicians in Europe. “If men are pushed too hard to feminize,” he warns, “they will become more and more interested in harsh, fascist political ideology.” Peterson sometimes asks audiences to view him as an alternative to political excesses on both sides. During an interview on BBC Radio 5, he said, “I’ve had thousands of letters from people who were tempted by the blandishments of the radical right, who’ve moved towards the reasonable center as a consequence of watching my videos.” But he typically sees liberals, or leftists, or “postmodernists,” as aggressors—which leads him, rather ironically, to frame some of those on the “radical right” as victims. Many of his political stances are built on this type of inversion. Postmodernists, he says, are obsessed with the idea of oppression, and, by waging war on oppressors real and imagined, they become oppressors themselves. Liberals, he says, are always talking about the importance of compassion—and yet “there’s nothing more horrible for children, and developing people, than an excess of compassion.” (This horror, he says, is embodied in the figure of the “Freudian devouring mother”; as an example, he cites Ursula, the sea witch from “The Little Mermaid.”) The danger, it seems, is that those who want to improve Western society may end up destroying it.

Peterson thinks that this danger has a lot to do with men and women, and the changing way we think about them. “The division of life into its twin sexes occurred before the evolution of multi-cellular animals,” he writes, by way of arguing that human beings are bound to care about this division. During his Channel 4 News debate, Cathy Newman pressed him on whether he supported gender equality, and he replied that it depended on what the term meant. “If it means equality of outcome, then almost certainly it’s undesirable,” he said. “Men and women won’t sort themselves into the same categories, if you leave them alone.” (He mentioned that in Scandinavia, an unusually egalitarian part of the world, men are vastly overrepresented among engineers, and women among nurses.) Convictions such as these inspire in him a general skepticism of efforts to redress gender inequality. He has argued that traditionally feminine traits, such as agreeableness, are not historically correlated with professional success. (He says that, as a psychologist, he has often counselled female clients to be more assertive at work.) When Newman suggested that this correlation might merely reflect the ways women have been shut out of corporate leadership, Peterson sounded doubtful. “It could be the case that if companies modified their behavior, and became more feminine, that they would be successful,” he said. “But there’s no evidence for that.”

Peterson is not primarily interested in policy, but he was eager to join the debate over C-16, the Canadian bill forbidding discrimination on the basis of gender identity or expression. In opposing the bill, Peterson claimed the mantle of free speech. “There’s a difference,” he explained, “between saying that there’s something you can’t say, and saying that there are things that you have to say.” But if laws against discrimination also prohibit harassment, they will necessarily prohibit some forms of verbal harassment—and they will therefore, to a greater or lesser extent, limit speech. Canada already limits speech in ways that the U.S. does not: a law against “hate speech” was repealed in 2013, but the government still bans “hate propaganda.” From an American perspective, such laws may seem ill-advised, or even oppressive. Still, like many free-speech arguments, this one was in large part a debate over the political status of a minority group.

The C-16 debate is over, for now—the bill passed and was enacted last summer. But Peterson remains a figurehead for the movement to block or curtail transgender rights. When he lampoons “made-up pronouns,” he sometimes seems to be lampooning the people who use them, encouraging his fans to view transgender or gender-nonbinary people as confused, or deluded. Once, after a lecture, he was approached on campus by a critic who wanted to know why he would not use nonbinary pronouns. “I don’t believe that using your pronouns will do you any good, in the long run,” he replied.

So what does Peterson actually believe about gender and pronouns? It can be hard to tell. Later in that campus conversation, when asked whether, in the absence of legal coercion, he would be willing to use pronouns such as “they” and “them” if a trans person asked him to, Peterson demurred. “It might depend on how they asked,” he said. One of his foundational beliefs is that cultures evolve, which suggests that nonstandard pronouns could become standard. In a debate about gender on Canadian television, in 2016, he tried to find some middle ground. “If our society comes to some sort of consensus over the next while about how we’ll solve the pronoun problem,” he said, “and that becomes part of popular parlance, and it seems to solve the problem properly, without sacrificing the distinction between singular and plural, and without requiring me to memorize an impossible list of an indefinite number of pronouns, then I would be willing to reconsider my position.”

Despite his fondness for moral absolutes, Peterson is something of a relativist; he is inclined to defer to a Western society that is changing in unpredictable ways. In discussing the many women who have criticized him, he has talked about how verbal disagreements commonly contain an implicit threat of violence, and about how such implicit threats are “forbidden” when men are addressing women. And yet, even when the topic is as elemental as male-female violence, our norms are changing: in the United States, laws against spousal violence were first enacted in the middle of the nineteenth century; laws against spousal rape are only a few decades old. Not long ago, these laws might have seemed intrusive and disruptive; now, many people shudder at the notion that it might ever have been legal for a man to physically assault his wife. Peterson excels at explaining why we should be careful about social change, but not at helping us assess which changes we should favor; just about any modern human arrangement could be portrayed as a radical deviation from what came before. In the case of gender identity, Peterson’s judgment is that “our society” has not yet agreed to adopt nontraditional pronouns, which isn’t quite an argument that we shouldn’t. And this judgment isn’t likely to be persuasive to people in places—like some North American college campuses, perhaps—where the singular “they” has already come to seem like part of the social fabric.

A different kind of culture warrior might express hostility to nontraditional pronouns in religious terms—in the United States, the fight against legal rights for L.G.B.T.Q. people has largely been led by believers. But Peterson—like his hero, Jung—has a complicated relationship to religious belief. He reveres the Bible for its stories, reasoning that any stories that we have been telling ourselves for so long must be, in some important sense, true. In a recent podcast interview, he mentioned that people sometimes ask him if he believes in God. “I don’t respond well to that question,” he said. “The answer to that question is forty hours long, and I can’t condense it into a sentence.” Forty hours, it turns out, is the approximate length of a lecture series that he created based on “Maps of Meaning.”

At times, Peterson emphasizes his interest in empirical knowledge and scientific research—although these tend to be the least convincing parts of “12 Rules for Life.” There is an extended analogy between human beings and lobsters, based on the observation that male lobsters that have proven themselves dominant produce more serotonin; he suggests that when people “slump around,” like weakling lobsters, they, too, will run short on serotonin, which will make them unhappy. The fact that serotonin has varied and sometimes contradictory effects scarcely matters here: Peterson’s story about the lobster is essentially a modern myth. He wants forlorn readers to imagine themselves as heroic lobsters; he wants an image of claws to appear in their mind whenever they feel themselves start to slump; he wants to help them.

Peterson wants to help everyone, in fact. In his least measured moments, he permits himself to dream of a world transformed. “Who knows,” he writes, “what existence might be like if we all decided to strive for the best?” His many years of study fostered in him a conviction that good and evil exist, and that we can discern them without recourse to any particular religious authority. This is a reassuring belief, especially in confusing times: “Each human being understands, a priori, perhaps not what is good, but certainly what is not.” No doubt there are therapists and life coaches all over the world dispensing some version of this formula, nudging their clients to pursue lives that better conform to their own moral intuitions. The problem is that, when it comes to the question of how to order our societies—when it comes, in other words, to politics—our intuitions have proved neither reliable nor coherent. The “highly functional infrastructure” he praises is the product of an unceasing argument over what is good, for all of us; over when to conform, and when to dissent. We can, most of us, sort ourselves out, or learn how to do it. That doesn’t mean we will ever agree on how to sort out everyone else. ♦

Books & Fiction

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Adam Gopnik

By Yuval Noah Harari

By Andrew Marantz

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

10 Step Guide To Clearer Thinking Through Essay Writing - Jordan B. Peterson

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

5 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

In collections.

Uploaded by Unknown on June 26, 2022

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Dr. Jordan B. Peterson is the bestselling writer of 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos, a clinical psychologist, and Professor of Psychology at the University of Toronto. "You can use this guide to write an excellent essay from beginning to end, using a ten-step process.

essays have to be spread out over the course, so that the TA does not get ridiculously overworked. Each essay must be 750 words long (plus or minus 50 words), typed and double-spaced. There are broad topic domains listed on the website. You have to choose a sub-topic, related to that broad topic, which can be intelligently addressed in the 750 ...

Dr. Jordan B. Peterson's Essay Writing Guide (with template) PART THREE: THE TOPIC AND THE READING LIST. The central question that you are trying to answer with the essay is the topic question.

PK !2'oWf ¥ [Content_Types].xml ¢ ( ´"ËjÃ0 E÷…þƒÑ¶ØJº(¥ÄÉ¢ e hú Š4NDõB£¼þ¾ã81¥$14ÉÆ ÏÜ{Ï 1ƒÑÚšl µw%ë =- "^i7+Ù×ä- d ...

First, select a word; then craft a sentence; finally, sequence sentences inside of a paragraph. Peterson suggests that each paragraph consist of at least 10 sentences or 100 words. Over time such ...

Jordan B. Peterson. Jordan B. Peterson is a Canadian clinical psychologist, self-help writer, cultural critic and professor of psychology at the University of Toronto. His main areas of study are in abnormal, social, and personality psychology, with a particular interest in the psychology of religious and ideological belief, and the assessment ...

Topics jordan peterson, writing, essay, thought, idea, thinking Collection opensource Language English. Jordan Peterson's approach to writing a good paper. Addeddate 2022-12-03 22:15:48 Identifier essay-writing-guide-jordan-peterson Identifier-ark ark:/13960/s2bcq5xqk25 Ocr tesseract 5.2.0-1-gc42a Ocr_detected_lang en Ocr_detected_lang_conf 1. ...

Jordan Peterson teaches in the department of psychology at the University of Toronto. For decades, he has been fascinated by the effects of writing on organizing thoughts and emotions.

Jordan B. Peterson - 10 Step Guide To Clearer Thinking Through Essay Writing. This is a summary with key lessons of Jordan B. Peterson's guide on how to write essays. It is a helpful guide that could help storytellers - or anyone else - to improve their writing skills. The full guide can be downloaded below. Download Full Guide. An essay is ...

This document outlines Dr. Jordan Peterson's 10-step guide for clearer thinking through essay writing. Peterson believes essay writing is an important way to clarify one's thinking and articulate ideas, not just to demonstrate knowledge to teachers. The guide explains that writing helps formulate coherent ideas by allowing the writer to develop and organize thoughts on paper where they can be ...

This video provides Jordan Peterson's most informative instructions on writing, and it summarizes his essay writing guide.1st clip is from Jordan B. Peterson...

Jordan Peterson teaches the importance of writing and why writing is a crucial skill. ... how to properly edit an essay, ... Find a topic that you're curious about and that tames your mind.

As I did a computer science degree, I never learned how to write formally; ergo, Jordan Peterson's essay writing guiding has been an invaluable resource for ...

First is the selection of the word. Second is the crafting of the sentence. Each word should be precisely the right word, in the right location in each sentence. The sentence itself should present a thought, part of the idea expressed in the paragraph, in a grammatically correct manner.

Peterson's 25-page writing guide is filled with valuable insights, such as why writing is an important life skill, tips on motivating yourself to write, how to properly edit an essay, and much more. Here are a few key takeaways from his guide. " The primary reason to write an essay is so that the writer can formulate and organize an ...

Step 1: Choose Topic, Read & Take Notes. Writing begins with these 3 steps: Pick a topic: because your essay should answer a central question. Make a reading list: You should aim to read 5-10 books before you write an essay. And plenty of online sources. Take Notes: of everything that catches your attention.

Jordan Peterson talks about how he brings a new thing to talk about every time he gives a talk. The value of writing essays and what the practice is all abou...

How to use the advanced features of Essay. 2 articles. Tutorial Articles. A collection of articles to help a writer follow Dr. Jordan B Peterson's essay writing process using essay.app. 7 articles. Videos. 1 article. Back to Essay; Roadmap; Essay writing guide;

Where the pickup artists promised to make guys better sexual salesmen (sexual consummation was called "full close," as in closing a deal), Peterson, more ambitious, promises to help them get ...

In conclusion, Jordan Peterson's 12 Rules for Life offers valuable insights and practical wisdom for individuals seeking to lead more meaningful and fulfilling lives. By embracing these principles ...

Julian Peterson appears on the Jordan B Peterson podcast to discuss Essay, writing, and other topics. Write your first bad draft today. Sign up for a 14-day free trial to see how you can take that draft and turn it into a powerful piece of writing. Start using Essay. Write Better. Think Better.

Microsoft Word - Essay_Writing_Guide.docx. Dr. Jordan Peterson's. Essay Writing Guide. You can use this word document to write an excellent essay from beginning to end, using a ten-step process. Most of the time, students or would-be essay writers are provided only with basic information about how to write, and most of that information ...

Topics jordan b. peterson, jordan peterson, essay, book, text, jbp, jordanbpeterson, jordanpeterson, 10 Step Guide To Clearer Thinking learer Thinking Through Essay Writing Collection opensource Language English