Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

- Collections

- Research Help

YSN Doctoral Programs: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Biomedical Databases

- Global (Public Health) Databases

- Soc. Sci., History, and Law Databases

- Grey Literature

- Trials Registers

- Data and Statistics

- Public Policy

- Google Tips

- Recommended Books

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an integrated analysis -- not just a summary-- of scholarly writings and other relevant evidence related directly to your research question. That is, it represents a synthesis of the evidence that provides background information on your topic and shows a association between the evidence and your research question.

A literature review may be a stand alone work or the introduction to a larger research paper, depending on the assignment. Rely heavily on the guidelines your instructor has given you.

Why is it important?

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Identifies critical gaps and points of disagreement.

- Discusses further research questions that logically come out of the previous studies.

APA7 Style resources

APA Style Blog - for those harder to find answers

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by your central research question. The literature represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow. Is it manageable?

- Begin writing down terms that are related to your question. These will be useful for searches later.

- If you have the opportunity, discuss your topic with your professor and your class mates.

2. Decide on the scope of your review

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment. How many sources does the assignment require?

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

Make a list of the databases you will search.

Where to find databases:

- use the tabs on this guide

- Find other databases in the Nursing Information Resources web page

- More on the Medical Library web page

- ... and more on the Yale University Library web page

4. Conduct your searches to find the evidence. Keep track of your searches.

- Use the key words in your question, as well as synonyms for those words, as terms in your search. Use the database tutorials for help.

- Save the searches in the databases. This saves time when you want to redo, or modify, the searches. It is also helpful to use as a guide is the searches are not finding any useful results.

- Review the abstracts of research studies carefully. This will save you time.

- Use the bibliographies and references of research studies you find to locate others.

- Check with your professor, or a subject expert in the field, if you are missing any key works in the field.

- Ask your librarian for help at any time.

- Use a citation manager, such as EndNote as the repository for your citations. See the EndNote tutorials for help.

Review the literature

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question of the study you are reviewing? What were the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze its literature review, the samples and variables used, the results, and the conclusions.

- Does the research seem to be complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicting studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Has this study been cited? If so, how has it been analyzed?

Tips:

- Review the abstracts carefully.

- Keep careful notes so that you may track your thought processes during the research process.

- Create a matrix of the studies for easy analysis, and synthesis, across all of the studies.

- << Previous: Recommended Books

- Last Updated: Jan 4, 2024 10:52 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/YSNDoctoral

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved April 15, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, what is your plagiarism score.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

- What Is a PhD Literature Review?

- Doing a PhD

A literature review is a critical analysis of published academic literature, mainly peer-reviewed papers and books, on a specific topic. This isn’t just a list of published studies but is a document summarising and critically appraising the main work by researchers in the field, the key findings, limitations and gaps identified in the knowledge.

- The aim of a literature review is to critically assess the literature in your chosen field of research and be able to present an overview of the current knowledge gained from previous work.

- By the conclusion of your literature review, you as a researcher should have identified the gaps in knowledge in your field; i.e. the unanswered research questions which your PhD project will help to answer.

- Quality not quantity is the approach to use when writing a literature review for a PhD but as a general rule of thumb, most are between 6,000 and 12,000 words.

What Is the Purpose of a Literature Review?

First, to be clear on what a PhD literature review is NOT: it is not a ‘paper by paper’ summary of what others have done in your field. All you’re doing here is listing out all the papers and book chapters you’ve found with some text joining things together. This is a common mistake made by PhD students early on in their research project. This is a sign of poor academic writing and if it’s not picked up by your supervisor, it’ll definitely be by your examiners.

The biggest issue your examiners will have here is that you won’t have demonstrated an application of critical thinking when examining existing knowledge from previous research. This is an important part of the research process as a PhD student. It’s needed to show where the gaps in knowledge were, and how then you were able to identify the novelty of each research question and subsequent work.

The five main outcomes from carrying out a good literature review should be:

- An understanding of what has been published in your subject area of research,

- An appreciation of the leading research groups and authors in your field and their key contributions to the research topic,

- Knowledge of the key theories in your field,

- Knowledge of the main research areas within your field of interest,

- A clear understanding of the research gap in knowledge that will help to motivate your PhD research questions .

When assessing the academic papers or books that you’ve come across, you must think about the strengths and weaknesses of them; what was novel about their work and what were the limitations? Are different sources of relevant literature coming to similar conclusions and complementing each other, or are you seeing different outcomes on the same topic by different researchers?

When Should I Write My Literature Review?

In the structure of your PhD thesis , your literature review is effectively your first main chapter. It’s at the start of your thesis and should, therefore, be a task you perform at the start of your research. After all, you need to have reviewed the literature to work out how your research can contribute novel findings to your area of research. Sometimes, however, in particular when you apply for a PhD project with a pre-defined research title and research questions, your supervisor may already know where the gaps in knowledge are.

You may be tempted to skip the literature review and dive straight into tackling the set questions (then completing the review at the end before thesis submission) but we strongly advise against this. Whilst your supervisor will be very familiar with the area, you as a doctoral student will not be and so it is essential that you gain this understanding before getting into the research.

How Long Should the Literature Review Be?

As your literature review will be one of your main thesis chapters, it needs to be a substantial body of work. It’s not a good strategy to have a thesis writing process here based on a specific word count, but know that most reviews are typically between 6,000 and 12,000 words. The length will depend on how much relevant material has previously been published in your field.

A point to remember though is that the review needs to be easy to read and avoid being filled with unnecessary information; in your search of selected literature, consider filtering out publications that don’t appear to add anything novel to the discussion – this might be useful in fields with hundreds of papers.

How Do I Write the Literature Review?

Before you start writing your literature review, you need to be clear on the topic you are researching.

1. Evaluating and Selecting the Publications

After completing your literature search and downloading all the papers you find, you may find that you have a lot of papers to read through ! You may find that you have so many papers that it’s unreasonable to read through all of them in their entirety, so you need to find a way to understand what they’re about and decide if they’re important quickly.

A good starting point is to read the abstract of the paper to gauge if it is useful and, as you do so, consider the following questions in your mind:

- What was the overarching aim of the paper?

- What was the methodology used by the authors?

- Was this an experimental study or was this more theoretical in its approach?

- What were the results and what did the authors conclude in their paper?

- How does the data presented in this paper relate to other publications within this field?

- Does it add new knowledge, does it raise more questions or does it confirm what is already known in your field? What is the key concept that the study described?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of this study, and in particular, what are the limitations?

2. Identifying Themes

To put together the structure of your literature review you need to identify the common themes that emerge from the collective papers and books that you have read. Key things to think about are:

- Are there common methodologies different authors have used or have these changed over time?

- Do the research questions change over time or are the key question’s still unanswered?

- Is there general agreement between different research groups in the main results and outcomes, or do different authors provide differing points of view and different conclusions?

- What are the key papers in your field that have had the biggest impact on the research?

- Have different publications identified similar weaknesses or limitations or gaps in the knowledge that still need to be addressed?

Structuring and Writing Your Literature Review

There are several ways in which you can structure a literature review and this may depend on if, for example, your project is a science or non-science based PhD.

One approach may be to tell a story about how your research area has developed over time. You need to be careful here that you don’t just describe the different papers published in chronological order but that you discuss how different studies have motivated subsequent studies, how the knowledge has developed over time in your field, concluding with what is currently known, and what is currently not understood.

Alternatively, you may find from reading your papers that common themes emerge and it may be easier to develop your review around these, i.e. a thematic review. For example, if you are writing up about bridge design, you may structure the review around the themes of regulation, analysis, and sustainability.

As another approach, you might want to talk about the different research methodologies that have been used. You could then compare and contrast the results and ultimate conclusions that have been drawn from each.

As with all your chapters in your thesis, your literature review will be broken up into three key headings, with the basic structure being the introduction, the main body and conclusion. Within the main body, you will use several subheadings to separate out the topics depending on if you’re structuring it by the time period, the methods used or the common themes that have emerged.

The important thing to think about as you write your main body of text is to summarise the key takeaway messages from each research paper and how they come together to give one or more conclusions. Don’t just stop at summarising the papers though, instead continue on to give your analysis and your opinion on how these previous publications fit into the wider research field and where they have an impact. Emphasise the strengths of the studies you have evaluated also be clear on the limitations of previous work how these may have influenced the results and conclusions of the studies.

In your concluding paragraphs focus your discussion on how your critical evaluation of literature has helped you identify unanswered research questions and how you plan to address these in your PhD project. State the research problem you’re going to address and end with the overarching aim and key objectives of your work .

When writing at a graduate level, you have to take a critical approach when reading existing literature in your field to determine if and how it added value to existing knowledge. You may find that a large number of the papers on your reference list have the right academic context but are essentially saying the same thing. As a graduate student, you’ll need to take a methodological approach to work through this existing research to identify what is relevant literature and what is not.

You then need to go one step further to interpret and articulate the current state of what is known, based on existing theories, and where the research gaps are. It is these gaps in the literature that you will address in your own research project.

- Decide on a research area and an associated research question.

- Decide on the extent of your scope and start looking for literature.

- Review and evaluate the literature.

- Plan an outline for your literature review and start writing it.

Browse PhDs Now

Join thousands of students.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 04 December 2020

- Correction 09 December 2020

How to write a superb literature review

Andy Tay is a freelance writer based in Singapore.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Literature reviews are important resources for scientists. They provide historical context for a field while offering opinions on its future trajectory. Creating them can provide inspiration for one’s own research, as well as some practice in writing. But few scientists are trained in how to write a review — or in what constitutes an excellent one. Even picking the appropriate software to use can be an involved decision (see ‘Tools and techniques’). So Nature asked editors and working scientists with well-cited reviews for their tips.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03422-x

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Updates & Corrections

Correction 09 December 2020 : An earlier version of the tables in this article included some incorrect details about the programs Zotero, Endnote and Manubot. These have now been corrected.

Hsing, I.-M., Xu, Y. & Zhao, W. Electroanalysis 19 , 755–768 (2007).

Article Google Scholar

Ledesma, H. A. et al. Nature Nanotechnol. 14 , 645–657 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Brahlek, M., Koirala, N., Bansal, N. & Oh, S. Solid State Commun. 215–216 , 54–62 (2015).

Choi, Y. & Lee, S. Y. Nature Rev. Chem . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41570-020-00221-w (2020).

Download references

Related Articles

- Research management

Shrouded in secrecy: how science is harmed by the bullying and harassment rumour mill

Career Feature 16 APR 24

‘Shrugging off failure is hard’: the $400-million grant setback that shaped the Smithsonian lead scientist’s career

Career Column 15 APR 24

Citizenship privilege harms science

Comment 15 APR 24

How we landed job interviews for professorships straight out of our PhD programmes

Career Column 08 APR 24

How two PhD students overcame the odds to snag tenure-track jobs

Adopt universal standards for study adaptation to boost health, education and social-science research

Correspondence 02 APR 24

Structure peer review to make it more robust

World View 16 APR 24

Is ChatGPT corrupting peer review? Telltale words hint at AI use

News 10 APR 24

Rwanda 30 years on: understanding the horror of genocide

Editorial 09 APR 24

Associate or Senior Editor (Immunology), Nature Communications

The Editor in Immunology at Nature Communications will handle original research papers and work on all aspects of the editorial process.

London, Beijing or Shanghai - Hybrid working model

Springer Nature Ltd

Assistant Professor - Cell Physiology & Molecular Biophysics

Opportunity in the Department of Cell Physiology and Molecular Biophysics (CPMB) at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center (TTUHSC)

Lubbock, Texas

Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, School of Medicine

Postdoctoral Associate- Curing Brain Tumors

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Energy AI / Grid Modernization / Hydrogen Energy / Power Semiconductor Concentration / KENTECH College

21, Kentech-gil, Naju-si, Jeollanam-do, Republic of Korea(KR)

Korea Institute of Energy Technology

Professor in Macromolecular Chemistry

The Department of Chemistry - Ångström conducts research and education in Chemistry. The department has 260 employees and has a turnover of 290 mil...

Uppsala (Stad) (SE)

Uppsala University

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Undergraduate courses

- Postgraduate courses

- Foundation courses

- Apprenticeships

- Part-time and short courses

- Apply undergraduate

- Apply postgraduate

Search for a course

Search by course name, subject, and more

- Undergraduate

- Postgraduate

- (suspended) - Available in Clearing Not available in Clearing location-sign UCAS

Fees and funding

- Tuition fees

- Scholarships

- Funding your studies

- Student finance

- Cost of living support

Why study at Kent

Student life.

- Careers and employability

- Student support and wellbeing

- Our locations

- Placements and internships

- Year abroad

- Student stories

- Schools and colleges

- International

- International students

- Your country

- Applicant FAQs

- International scholarships

- University of Kent International College

- Campus Tours

- Applicant Events

- Postgraduate events

- Maps and directions

- Research strengths

- Research centres

- Research impact

Research institutes

- Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology

- Institute of Cyber Security for Society

- Institute of Cultural and Creative Industries

- Institute of Health, Social Care and Wellbeing

Research students

- Graduate and Researcher College

- Research degrees

- Find a supervisor

- How to apply

Popular searches

- Visits and Open Days

- Jobs and vacancies

- Accommodation

- Student guide

- Library and IT

- Partner with us

- Student Guide

- Student Help

- Health & wellbeing

- Student voice

- Living at Kent

- Careers & volunteering

- Diversity at Kent

- Finance & funding

- Life after graduation

Literature reviews

Writing a literature review.

The following guide has been created for you by the Student Learning Advisory Service . For more detailed guidance and to speak to one of our advisers, please book an appointment or join one of our workshops . Alternatively, have a look at our SkillBuilder skills videos.

Preparing a literature review involves:

- Searching for reliable, accurate and up-to-date material on a topic or subject

- Reading and summarising the key points from this literature

- Synthesising these key ideas, theories and concepts into a summary of what is known

- Discussing and evaluating these ideas, theories and concepts

- Identifying particular areas of debate or controversy

- Preparing the ground for the application of these ideas to new research

Finding and choosing material

Ensure you are clear on what you are looking for. ask yourself:.

- What is the specific question, topic or focus of my assignment?

- What kind of material do I need (e.g. theory, policy, empirical data)?

- What type of literature is available (e.g. journals, books, government documents)?

What kind of literature is particularly authoritative in this academic discipline (e.g. psychology, sociology, pharmacy)?

How much do you need?

This will depend on the length of the dissertation, the nature of the subject, and the level of study (undergraduate, Masters, PhD). As a very rough rule of thumb – you may choose 8-10 significant pieces (books and/or articles) for an 8,000 word dissertation, up to 20 major pieces of work for 12-15,000 words, and so on. Bear in mind that if your dissertation is based mainly around an interaction with existing scholarship you will need a longer literature review than if it is there as a prelude to new empirical research. Use your judgement or ask your supervisor for guidance.

Where to find suitable material

Your literature review should include a balance between substantial academic books, journal articles and other scholarly publications. All these sources should be as up-to-date as possible, with the exception of ‘classic texts’ such as major works written by leading scholars setting out formative ideas and theories central to your subject. There are several ways to locate suitable material:

Module bibliography: for undergraduate dissertations, look first at the bibliography provided with the module documentation. Choose one or two likely looking books or articles and then scan through the bibliographies provided by these authors. Skim read some of this material looking for clues: can you use these leads to identify key theories and authors or track down other appropriate material?

Library catalogue search engine: enter a few key words to capture a range of items, but avoid over-generalisations; if you type in something as broad as ‘social theory’ you are likely to get several thousand results. Be more specific: for example, ‘Heidegger, existentialism’. Ideally, you should narrow the field to obtain just a few dozen results. Skim through these quickly to identity texts which are most likely to contribute to your study.

Library bookshelves: browse the library shelves in the relevant subject area and examine the books that catch your eye. Check the contents and index pages, or skim through the introductions (or abstracts, in the case of journal articles) to see if they contain relevant material, and replace them if not. Don’t be afraid to ask one of the subject librarians for further help. Your supervisor may also be able to point you in the direction of some of the important literature , but remember this is your literature search, not theirs.

Online: for recent journal articles you will almost certainly need to use one of the online search engines. These can be found on the ‘Indexing Services’ button on the Templeman Library website. Kent students based at Medway still need to use the Templeman pages to access online journals, although you can get to these pages through the Drill Hall Library catalogue. Take a look as well at the Subject Guides on both the Templeman and DHL websites.

Check that you have made the right selection by asking:

- Has my search been wide enough to ensure that I have identified all the relevant material, but narrow enough to exclude irrelevant material?

- Is there a good enough sample of literature for the level (PhD, Masters, undergraduate) of my dissertation or thesis?

- Have I considered as many alternative points of view as possible?

- Will the reader find my literature review relevant and useful?

Assessing the literature

Read the material you have chosen carefully, considering the following:

- The key point discussed by the author: is this clearly defined

- What evidence has the author produced to support this central idea?

- How convincing are the reasons given for the author’s point of view?

- Could the evidence be interpreted in other ways?

- What is the author's research method (e.g. qualitative, quantitative, experimental, etc.)?

- What is the author's theoretical framework (e.g. psychological, developmental, feminist)?

- What is the relationship assumed by the author between theory and practice?

- Has the author critically evaluated the other literature in the field?

- Does the author include literature opposing their point of view?

- Is the research data based on a reliable method and accurate information?

- Can you ‘deconstruct’ the argument – identify the gaps or jumps in the logic?

- What are the strengths and limitations of this study?

- What does this book or article contribute to the field or topic?

- What does this book or article contribute to my own topic or thesis?

As you note down the key content of each book or journal article (together with the reference details of each source) record your responses to these questions. You will then be able to summarise each piece of material from two perspectives:

Content: a brief description of the content of the book or article. Remember, an author will often make just one key point; so, what is the point they are making, and how does it relate to your own research project or assignment?

Critical analysis: an assessment of the relative strengths and weaknesses of the evidence used, and the arguments presented. Has anything conveniently been left out or skated over? Is there a counter-argument, and has the author dealt with this adequately? Can the evidence presented be interpreted another way? Does the author demonstrate any obvious bias which could affect their reliability? Overall, based on the above analysis of the author’s work, how do you evaluate its contribution to the scholarly understanding and knowledge surrounding the topic?

Structuring the literature review

In a PhD thesis, the literature review typically comprises one chapter (perhaps 8-10,000 words), for a Masters dissertation it may be around 2-3,000 words, and for an undergraduate dissertation it may be no more than 2,000 words. In each case the word count can vary depending on a range of factors and it is always best, if in doubt, to ask your supervisor.

The overall structure of the section or chapter should be like any other: it should have a beginning, middle and end. You will need to guide the reader through the literature review, outlining the strategy you have adopted for selecting the books or articles, presenting the topic theme for the review, then using most of the word limit to analyse the chosen books or articles thoroughly before pulling everything together briefly in the conclusion.

Some people prefer a less linear approach. Instead of simply working through a list of 8-20 items on your book review list, you might want to try a thematic approach, grouping key ideas, facts, concepts or approaches together and then bouncing the ideas off each other. This is a slightly more creative (and interesting) way of producing the review, but a little more risky as it is harder to establish coherence and logical sequencing.

Whichever approach you adopt, make sure everything flows smoothly – that one idea or book leads neatly to the next. Take your reader effortlessly through a sequence of thought that is clear, accurate, precise and interesting.

Writing up your literature review

As with essays generally, only attempt to write up the literature review when you have completed all the reading and note-taking, and carefully planned its content and structure. Find an appropriate way of introducing the review, then guide the reader through the material clearly and directly, bearing in mind the following:

- Be selective in the number of points you draw out from each piece of literature; remember that one of your objectives is to demonstrate that you can use your judgement to identify what is central and what is secondary.

- Summarise and synthesise – use your own words to sum up what you think is important or controversial about the book or article.

- Never claim more than the evidence will support. Too many dissertations and theses are let down by sweeping generalisations. Be tentative and careful in the way you interpret the evidence.

- Keep your own voice – you are entitled to your own point of view provided it is based on evidence and clear argument.

- At the same time, aim to project an objective and tentative tone by using the 3rd person, (for example, ‘this tends to suggest’, ‘it could be argued’ and so on).

- Even with a literature review you should avoid using too many, or overlong, quotes. Summarise material in your own words as much as possible. Save the quotes for ‘punch-lines’ to drive a particular point home.

- Revise, revise, revise: refine and edit the draft as much as you can. Check for fluency, structure, evidence, criticality and referencing, and don’t forget the basics of good grammar, punctuation and spelling.

What’s Included: Literature Review Template

This template is structure is based on the tried and trusted best-practice format for formal academic research projects such as dissertations and theses. The literature review template includes the following sections:

- Before you start – essential groundwork to ensure you’re ready

- The introduction section

- The core/body section

- The conclusion /summary

- Extra free resources

Each section is explained in plain, straightforward language , followed by an overview of the key elements that you need to cover. We’ve also included practical examples and links to more free videos and guides to help you understand exactly what’s required in each section.

The cleanly-formatted Google Doc can be downloaded as a fully editable MS Word Document (DOCX format), so you can use it as-is or convert it to LaTeX.

PS – if you’d like a high-level template for the entire thesis, you can we’ve got that too .

FAQs: Literature Review Template

What format is the template (doc, pdf, ppt, etc.).

The literature review chapter template is provided as a Google Doc. You can download it in MS Word format or make a copy to your Google Drive. You’re also welcome to convert it to whatever format works best for you, such as LaTeX or PDF.

What types of literature reviews can this template be used for?

The template follows the standard format for academic literature reviews, which means it will be suitable for the vast majority of academic research projects (especially those within the sciences), whether they are qualitative or quantitative in terms of design.

Keep in mind that the exact requirements for the literature review chapter will vary between universities and degree programs. These are typically minor, but it’s always a good idea to double-check your university’s requirements before you finalize your structure.

Is this template for an undergrad, Master or PhD-level thesis?

This template can be used for a literature review at any level of study. Doctoral-level projects typically require the literature review to be more extensive/comprehensive, but the structure will typically remain the same.

Can I modify the template to suit my topic/area?

Absolutely. While the template provides a general structure, you should adapt it to fit the specific requirements and focus of your literature review.

What structural style does this literature review template use?

The template assumes a thematic structure (as opposed to a chronological or methodological structure), as this is the most common approach. However, this is only one dimension of the template, so it will still be useful if you are adopting a different structure.

Does this template include the Excel literature catalog?

No, that is a separate template, which you can download for free here . This template is for the write-up of the actual literature review chapter, whereas the catalog is for use during the literature sourcing and sorting phase.

How long should the literature review chapter be?

This depends on your university’s specific requirements, so it’s best to check with them. As a general ballpark, literature reviews for Masters-level projects are usually 2,000 – 3,000 words in length, while Doctoral-level projects can reach multiples of this.

Can I include literature that contradicts my hypothesis?

Yes, it’s important to acknowledge and discuss literature that presents different viewpoints or contradicts your hypothesis. So, don’t shy away from existing research that takes an opposing view to yours.

How do I avoid plagiarism in my literature review?

Always cite your sources correctly and paraphrase ideas in your own words while maintaining the original meaning. You can always check our plagiarism score before submitting your work to help ease your mind.

Do you have an example of a populated template?

We provide a walkthrough of the template and review an example of a high-quality literature research chapter here .

Can I share this literature review template with my friends/colleagues?

Yes, you’re welcome to share this template in its original format (no editing allowed). If you want to post about it on your blog or social media, all we ask is that you reference this page as your source.

Do you have templates for the other dissertation/thesis chapters?

Yes, we do. You can find our full collection of templates here .

Can Grad Coach help me with my literature review?

Yes, you’re welcome to get in touch with us to discuss our private coaching services , where we can help you work through the literature review chapter (and any other chapters).

- Library Catalogue

Literature reviews for graduate students

On this page, what is a literature review, literature review type definitions, literature review protocols and guidelines, to google scholar, or not to google scholar, subject headings vs. keywords, keeping track of your research, project management software, citation management software, saved searches.

Related guides:

- Systematic, scoping, and rapid reviews: An overview

- Academic writing: what is a literature review , a guide that addresses the writing and composition aspect of a literature review

- Media literature reviews: how to conduct a literature review using news sources

- Literature reviews in the applied sciences

- Start your research here , literature review searching, mainly of interest to newer researchers

For more assistance, please contact the Liaison Librarian in your subject area .

Most generally, a literature review is a search within a defined range of information source types, such as, for instance, journals and books, to discover what has been already written about a specific subject or topic. A literature review is a key component of almost all research papers. However, the term is often applied loosely to describe a wide range of methodological approaches. A literature review in a first or second year course may involve browsing the library databases to get a sense of the research landscape in your topic and including 3-4 journal articles in your paper. At the other end of the continuum, the review may involve completing a comprehensive search, complete with documented search strategies and a listing of article inclusion and exclusion criteria. In the most rigorous format - a Systematic Review - a team of researchers may compile and review over 100,000 journal articles in a project spanning one to two years! These are out of scope for most graduate students, but it is important to be aware of the range of types of reviews possible.

One of the first steps in conducting a lit review is thus to clarify what kind of review you are doing, and its associated expectations.

Factors determining review approach are varied, including departmental/discipline conventions, granting agency stipulations, evolving standards for evidence-based research (and the corollary need for documented, replicable search strategies), and available time and resources.

The standards are also continually evolving in light of changing technology and evidence-based research about literature review methodology effectiveness. The availability of new tools such as large-scale library search engines and sophisticated citation management software continues to influence the research process.

Some specific types of lit reviews types include systematic reviews , scoping reviews , realist reviews , narrative reviews , mapping reviews, and qualitative systematic reviews , just to name a few. The protocols and distinctions for review types are particularly delineated in health research fields, but we are seeing conventions quickly establishing themselves in other academic fields.

The below definitions are quoted from the very helpful book, Booth, A., Papaioannou, D., & Sutton, A. (2012). Systematic approaches to a successful literature review . London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

For more definitions, try:

- Grant, M.J. & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of the 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal , 26(2), 91-108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Sage Research Methods Online. A database devoted to research methodology. Includes handbooks, encyclopedia entries, and a research concepts map.

- Research Methods

- Report Writing

- Research--Methodology

- Research--Methodology--Handbooks, manuals, etc.

Note: There is unfortunately no subject heading specifically for "literature reviews" which brings together all related material.

Mapping Review : "A rapid search of the literature aiming to give a broad overview of the characteristics of a topic area. Mapping of existing research, identification of gaps, and a summary assessment of the quantity and quality of the available evidence helps to decide future areas for research or for systematic reviews." (Booth, Papaioannou & Sutton, 2012, p. 264)

Mixed Method Review : "A literature review that seeks to bring together data from quantitative and qualitative studies integrating them in a way that facilitates subsequent analysis" (Booth et al., p. 265).

Meta-analysis : "The process of combining statistically quantitative studies that have measured the same effect using similar methods and a common outcome measure" (Booth et al., p. 264).

Narrative Review: "A term used to describe a conventional overview of the literature, particularly when contrasted with a systematic review" (Booth et al., p. 265).

Note: this term is often used pejoratively, describing a review that is inadvertently guided by a confirmation bias.

Qualitative Evidence Synthesis : "An umbrella term increasingly used to describe a group of review types that attempt to synthesize and analyze findings from primary qualitative research studies" (Booth et al., p. 267).

Rapid Review : "Assessment of what is already known about a policy or practice issue, by using systematic review methods to search and critically appraise existing research" (Grant & Booth, 2009, p.96).

Note: Rapid reviews are often done when there are insufficient time and/or resources to conduct a systematic review. As stated by Butler et. al, "They aim to be rigorous and explicit in method and thus systematic but make concessions to the breadth or depth of the process by limiting particular aspects of the systematic review process" (as cited in Grant & Booth, 2009, p. 100).

Scoping Review: "A type of review that has as its primary objective the identification of the size and quality of research in a topic area in order to inform subsequent review" (Booth et al., p. 269).

Systematic Review : "A review of a clearly formulated question that uses systematic and explicit methods to identify, select and critically appraise relevant research and to collect and analyse data from the studies that are included in the review" (Booth et al., p. 271).

Note : a systematic review (SR) is the most extensive and well-documented type of lit review, as well as potentially the most time-consuming. The idea with SRs is that the search process becomes a replicable scientific study in itself. This level of review will possibly not be necessary (or desirable) for your research project.

Many lit review types are based on organization-driven specific protocols for conducting the reviews. These protocols provide specific frameworks, checklists, and other guidance to the generic literature review sub-types. Here are a few popular examples:

Cochrane Review - known as the "gold standard" of systematic reviews, designed by the Cochrane Collaboration. Primarily used in health research literature reviews.

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions . "The official document that describes in detail the process of preparing and maintaining Cochrane systematic reviews".

Campbell Review - the sister organization of the Cochrane Institute which focuses on systematic reviews in the social sciences.

- So you want to write a Campbell Systematic review?

- Campbell Information Retrieval Guide. The details of effective information searching

Literature Reviews in Psychology

A recent article in the Annual Review of Psychology provides a very helpful guide to conducting literature reviews specifically in the field of Psychology.

How to Do a Systematic Review: A Best Practice Guide for Conducting and Reporting Narrative Reviews, Meta-Analyses, and Meta-Syntheses. (2019). Annual Review of Psychology, 70 (1), 747-770. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102803

Rapid Reviews have become increasingly common due to their flexibility, as well as the lack of time and resources available to do a comprehensive systematic review. McMaster University's National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools (NCCMT) has created a Rapid Review Guidebook , which "details each step in the rapid review process, with notes on how to tailor the process given resource limitations."

Scoping Review

There is no strict protocol for a scoping review (unlike Campbell and Cochrane reviews). The following are some recommended guidelines for scoping reviews:

- Scoping Reviews from the JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis

- Current best practices for the conduct of scoping reviews, from the EQUATOR Network

In addition to protocols which provide holistic guidance for conducting specific kinds of reviews, there are also a vast number of frameworks, checklists, and other tools available to help focus your review and ensure comprehensiveness. Some provide broader-level guidance; others are targeted to specific parts of your reviews such as data extraction or reporting out results.

- PICO or PICOC A framework for posing a researchable question (population, intervention, comparisons, outcomes, context/environment)

- PRISMA Minimum items to report upon in a systematic review, as well as its extensions , such as PRISMA-ScR (for scoping reviews)

- SALSA framework: frames the literature review into four parts: search (S), appraisal(AL), synthesis(S), analysis(A)

- STARLITE Minimum requirements for reporting out on literature reviews.

- Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) Checklists Includes a checklist for evaluating Systematic Reviews.

These are just a sampling of specific guides generated from the ever-growing literature review industry.

Much of the online discussion about the use of Google Scholar in literature reviews seems to focus more on values and ideals, rather than a technical assessment of the search engine's role. Here are some things to keep in mind.

- It's good practice to use both Google Scholar and subject-specific databases (example: PsycINFO) for conducting a lit review of any type. For most graduate-level literature reviews, it is usually recommended to use both.

- You should search Google Scholar through the library's website when off-campus. This way you can avoid being prompted for payment to access articles that the SFU Library already subscribes to.

- Search tips for Google and Google Scholar

Google Advantages:

- Allows you to cast a wide net in your search.

- The most popular articles are revealed

- A high volume of articles are retrieved

- Google's algorithm helps compensate for poorly designed searches

- Full-text indexing of articles is now being done in Google Scholar

- A search feature allow you to search within articles citing your key article

- Excellent for known-item searching or locating a quote/citation

- Helpful when searching for very unique terminology (e.g., places and people)

- Times cited tool can help identify relevant articles

- Extensive searching of non-article, but academic, information items: universities' institutional repositories, US case law, grey literature , academic websites, etc.

Disadvantages:

- The database is not mapped to a specific discipline

- Much less search sophistication and manipulation supported

- Psuedo-Boolean operators

- Missing deep data (e.g., statistics)

- Mysterious algorithms and unknown source coverage at odds with the systematic and transparent requirement of a literature review.

- Searches are optimized (for example, by your location), thwarting the replicability criteria of most literature review types

- Low level of subject and author collocation - that is, bringing together all works by one author or one sub-topic

- Challenging to run searches that involve common words. A search for "art AND time", for example, might bring up results on the art of time management when you are looking for the representation of time in art. In contrast, searching by topic is readily facilitated by use of subject headings in discipline-specific databases. Google Scholar has no subject headings.

- New articles might not be pushed up if the popularity of an article is prioritized

- Indexes articles from predatory publishers , which may be hard to identify if working outside of your field

Unlike Google Scholar, subject specific databases such as PsycINFO , Medline , or Criminal Justice Abstracts are mapped to a disciplinary perspective. Article citations contain high-quality and detailed metadata. Metadata can be used to build specific searches and apply search limits relevant to your subject area. These databases also often offer access to specialized material in your area such as grey literature , psychological tests, statistics, books and dissertations.

For most graduate-level literature reviews, it is usually recommended to use both. Build careful searches in the subject/academic databases, and check Google Scholar as well.

For most graduate-level lit reviews, you will want to make use of the subject headings (aka descriptors) found in the various databases.

Subject headings are words or phrases assigned to articles, books, and other info items that describe the subject of their content. They are designed to succinctly capture a document's concepts, allowing the researcher to retrieve all articles/info items about that concept using one term. By identifying the subject headings associated with your research areas, and subsequently searching the database for other articles and materials assigned with that same subject heading, you are taking a significant measure to ensure the comprehensiveness of your literature review.

About subject headings:

- They are applied systematically : articles and books will usually have about 3-8 subject headings assigned to their bibliographic record.

- The subject headings come from a finite pool of terms - one that is updated frequently.

- They are often organized in a hierarchical taxonomy , with subject headings belonging to broader headings, and/or having narrower headings beneath them. Sometimes there are related terms (lateral) as well.

- They provide a standardized way to describe a concept. For instance, a subject heading of "physician" may be used to capture many of the natural language words that describe a physician such as doctor, family doctor, GP, and MD.

One way to identify subject headings (SHs) of interest to you is to start with a keyword search in a database, and see which SHs are associated with the articles of interest.

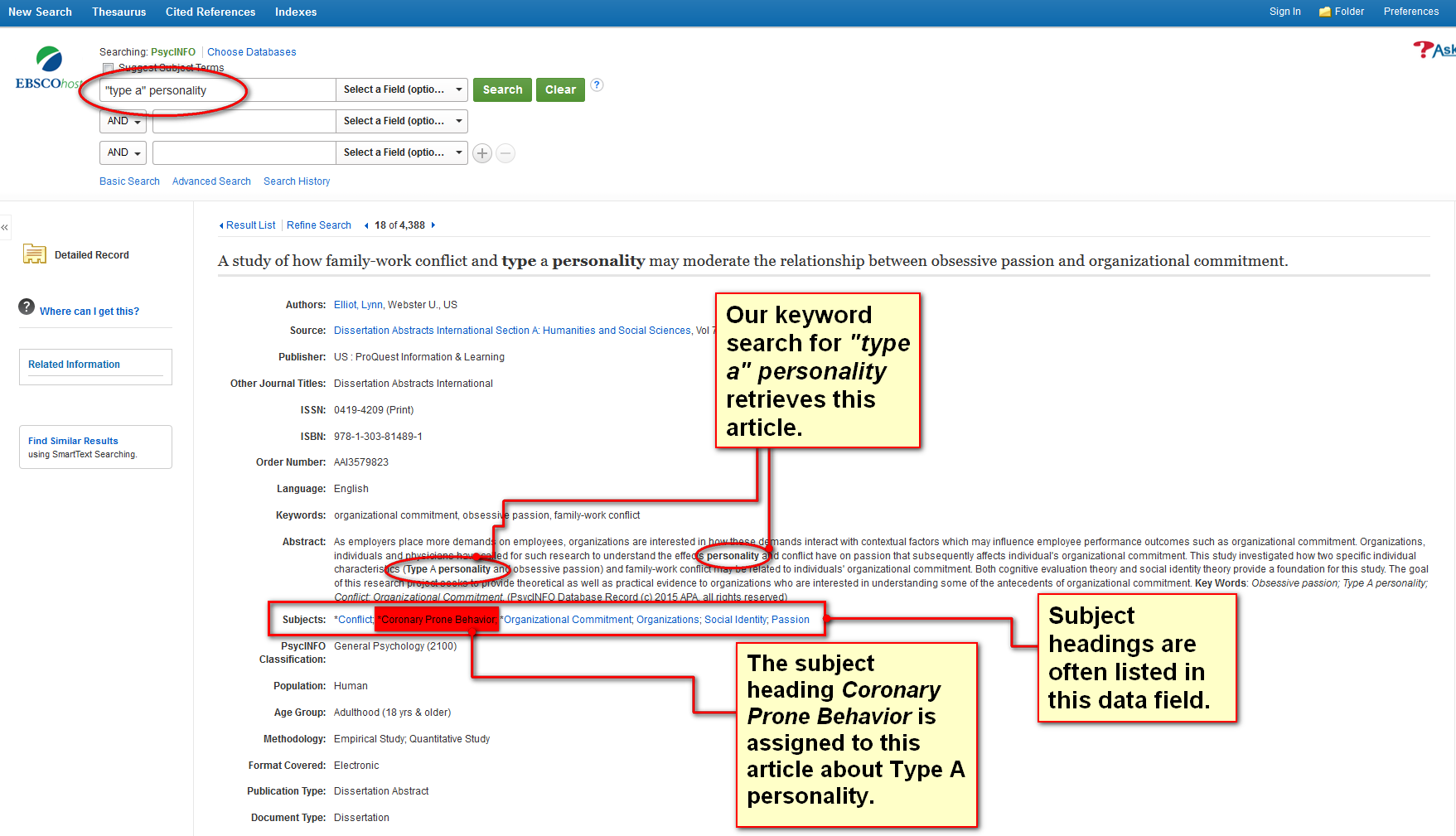

A. In the below example, we start with a keyword search for "type a" personality in PsycINFO . A more contemporary term to describe this phenomena is then found in the subject heading field:

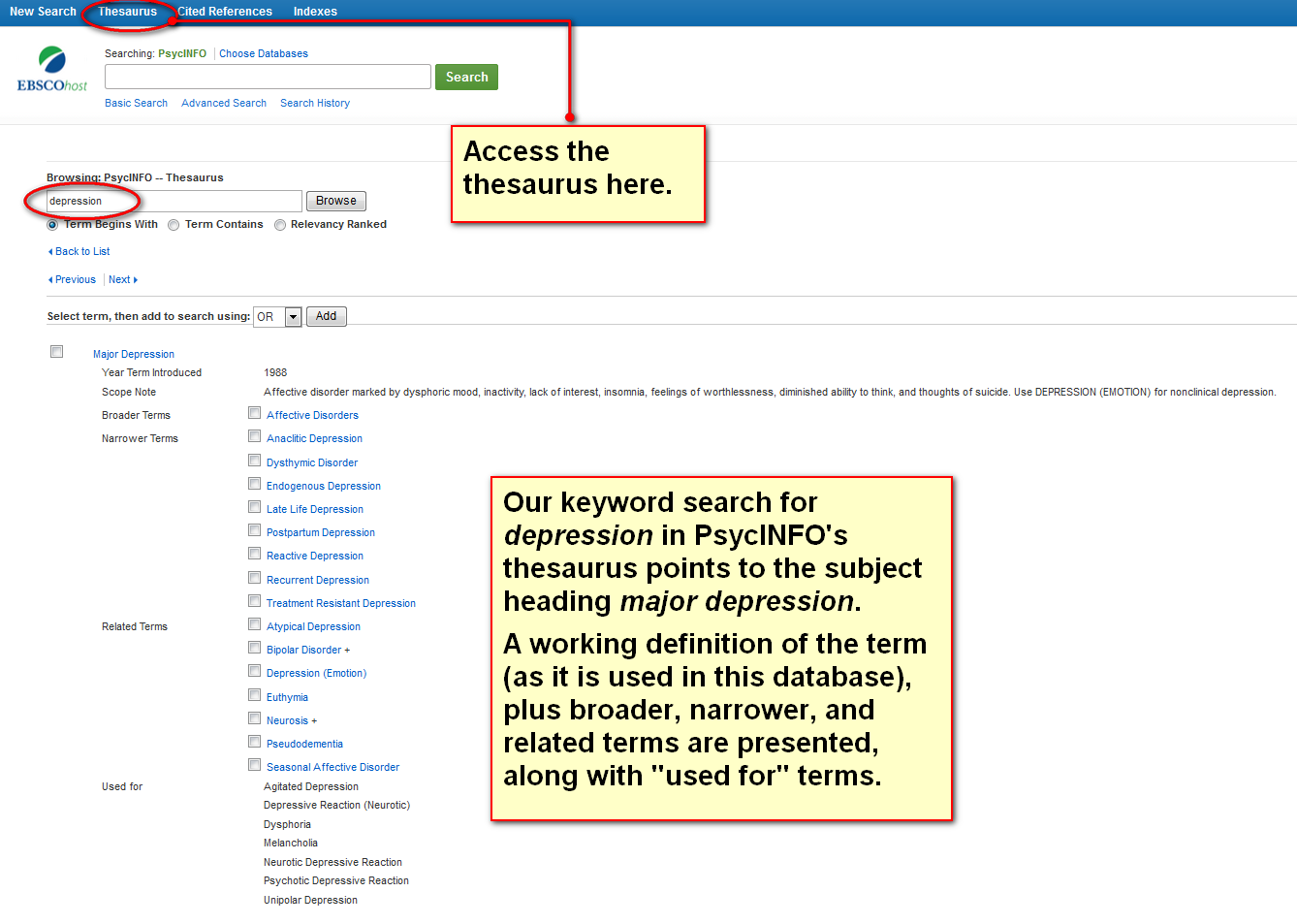

B. Another way to identify subject headings related to your topic is to go directly to a database's thesaurus or index. For example, if we are researching depression, the PsycINFO entry for major depression suggests some narrower terms we could focus our search by.

For more in-depth help with using subject headings in a literature review, please contact the Liaison Librarian in your subject area .

- NEW! Covidence . Covidence is a web-based literature review tool that will help you through the process of screening your references, data extraction, and keeping track of your work. Ideal for streamlining systematic reviews, scoping reviews, meta-analyses, and other related methods of evidence synthesis.

- NVivo is a robust software package that helps with management and analysis of qualitative information.The Library's Research Commons offers extensive support for NVivo.

- Research Support Software offered by the Research Commons

Citation management software such as Zotero, Mendeley, or Endnote is essential for completing a substantial lit review. Citation software is a centralized, online location for managing your sources. Specifically, it allows you to:

- Access and manage your sources online, all in one place

- Import references from library databases and websites

- Automatically generate bibliographies and in-text citations within Microsoft Word

- Share your collection of sources with others, and work collaboratively with references

- De-duplicate your search results* (*Note: Mendeley is not recommended for deduplication in systematic reviews.)

- Annotate your citations. Some software allows you to mark up PDFs.

- Note trends in your research such as which journals or authors you cite from the most.

More information on Citation Management Software

Did you know that many databases allow you to save your search strategies? The advantages of saving and tracking your search strategies online in a literature review include:

- Developing your search strategy in a methodological manner, section by section. For instance, you can run searches for all synonyms and subjects headings associated with one concept, then combine them with different concepts in various combinations.

- Re-running your well-executed search in the future

- Creating search alerts based on a well-designed search, allowing you to stay notified of new research in your area

- Tracking and remember all of the searches you have done. Avoid inadvertently re-doing your searches by being well-documented and systematic as you go along - it's worth the extra effort!

Databases housed on the EBSCO plaform (examples: Business Source Complete, PsycINFO, Medline, Academic Search Premier) allow you to create an free account where you might save your searches:

- Using the EBSCOhost Search History - Tutorial [2:08]

- Creating a Search Alert in EBSCOhost - Tutorial [1:26]

- UWF Libraries

Literature Review: Conducting & Writing

- Sample Literature Reviews

- Steps for Conducting a Lit Review

- Finding "The Literature"

- Organizing/Writing

- APA Style This link opens in a new window

- Chicago: Notes Bibliography This link opens in a new window

- MLA Style This link opens in a new window