Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- French Abstracts

- Portuguese Abstracts

- Spanish Abstracts

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About International Journal for Quality in Health Care

- About the International Society for Quality in Health Care

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Contact ISQua

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, results of data synthesis, conclusions, acknowledgements.

- < Previous

How are medication errors defined? A systematic literature review of definitions and characteristics

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

M. Lisby, L.P. Nielsen, B. Brock, J. Mainz, How are medication errors defined? A systematic literature review of definitions and characteristics, International Journal for Quality in Health Care , Volume 22, Issue 6, December 2010, Pages 507–518, https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzq059

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Multiplicity in terminology has been suggested as a possible explanation for the variation in the prevalence of medication errors. So far, few empirical studies have challenged this assertion. The objective of this review was, therefore, to describe the extent and characteristics of medication error definitions in hospitals and to consider the consequences for measuring the prevalence of medication errors.

Studies were searched for in PubMed, PsychINFO, Embase and CINAHL employing primary search terms such as ‘medication errors’ and ‘adverse drug events’. Peer-reviewed articles containing these terms as primary end-points were included. Study country, year, aim, design, data-collection methods, sample-size, interventions and main results were extracted.

Forty-five of 203 relevant studies provided a generic definition of medication errors including 26 different forms of wordings. The studies conducted in nine countries represented a variety of clinical settings and the approach was mainly descriptive. Of utmost importance is the documented prevalence of medication errors, which ranged from 2 to 75% with no associations found between definitions and prevalence.

Inconsistency in defining medication errors has been confirmed. It appears that definitions and methods of detection rather than being reproducible and reliable methods are subject to the individual researcher's preferences. Thus, application of a clear-cut definition, standardized terminology and reliable methods has the potential to greatly improve the quality and consistency of medication error reporting. Efforts to achieve a common accepted definition that defines the scope and content are therefore needed.

In the Harvard Medical Practice studies of adverse events in hospitals, medication errors were found to be the main contributor constituting around one in five of the events, which were subsequently confirmed in comparable studies and studies of adverse drug events (ADEs) [ 1–4 ]. This has led to an increased focus on epidemiology and prevention of medication error in hospital settings around the world prompting numerous studies [ 5–13 ]. However, this contribution has not provided clarity or consistent findings with respect to medication errors. Quite the contrary, there appears to be a multiplicity of terms involved in defining the clinical range of medication errors and classifying consequences e.g. error, failure, near miss, rule violation, deviation, preventable ADE and potential ADE [ 14–18 ]. Moreover, it has been suggested that this inconsistency has contributed to the substantial variation in the reported occurrences of medication errors [ 19–21 ]. Thus, compared with other epidemiological fields in health care, no single definition is currently being used to determine medication errors although attempts to develop an international definition have been made e.g. National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERP) [ 22 ], which is clearly reflected in the referred literature. As an important consequence, this lack of clarity hinders reliable comparison of findings across studies, clinical settings and countries.

Another obstacle to achieving consensus of a common definition is the different approaches towards interpreting and detecting medication errors such as the system-oriented approach using mandatory or voluntary-based reporting systems in contrast to the epidemiological approach using specific research methods. Choice of reliable methods, including denominators, data completeness and systematic data collection, is essential in the epidemiological approach. However, these considerations are likely to be secondary in a system approach where causation is paramount. Unfortunately, identifying error causes without consistent, reliable measures is unlikely to lead to well-targeted prevention strategies. So far, the literature has mainly emphasized the problem of inconsistent use of definitions and data collection methods, whereas few studies have explored medical error subsets, and these have often been in specific clinical settings or particular to specific patient safety organizations [ 5 , 19–21 , 23–25 ]. Most importantly, no studies have to our knowledge systematically provided an overview of the extent of existing definitions and their possible impact on the occurrence of medication errors. Hence, the objective of this study was to investigate definitions of medication errors and, furthermore, to describe characteristics as well as to assess whether or not there were any associations between definitions and observed prevalence in hospitals.

Data sources

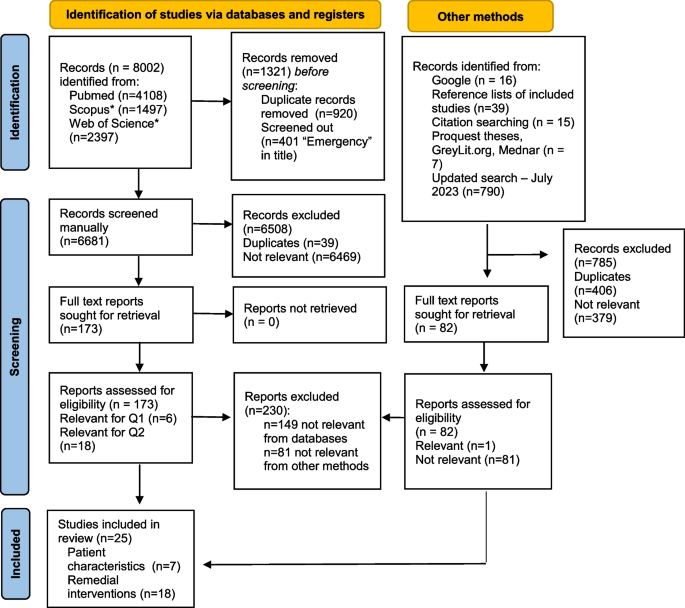

A systematic search of studies related to medication errors was performed in the databases on 18 December 2006 in PubMed (1951), Embase (1948), CINAHL (1981) and PsycINFO (1806) using the following key terms: ‘medication errors’, ‘adverse drug events’, ‘adverse drug events and errors’ and ‘medication errors and adverse drug events’ (Fig. 1 ). To capture all possible studies of medication errors in hospitals, the search was not restricted to MeSH terms in PubMed. However, a comparable search using the MeSH term ‘medication errors’ was performed in which all studies from the key term search could be retrieved.

Summary of search and review process.

Study selection

Only studies performed in hospital settings having medication errors and/or ADEs as the main objective were included in the present review, excluding studies performed solely in primary health care and literature reviews of medication errors and ADE (Fig. 1 ). Although there is no reason to believe that the occurrence of medication errors would be significantly different from hospitals, primary health care was excluded in this review due to assumed differences in medication handling and to the limited amount of completed medication error research in primary health care when the literature search was conducted. Finally, the search was limited to peer-reviewed studies with abstracts and studies presented in English.

First, titles and abstracts were examined in accordance with inclusion and exclusion criteria. Secondly, papers that met the inclusion criteria or papers in which inclusion could not be determined directly e.g. whether a setting was representing primary care were obtained. Thirdly, all duplicates between databases, papers that did not meet the inclusion criteria or papers that could not be obtained were excluded.

Data extraction

Definitions of medication errors and ADEs were registered along with included error types and whether the paper focused on ordering, dispensing, administering and monitoring. Moreover, general information regarding journal, author, year, title, aim, setting, participants, design, methods, intervention, results and evidence level were registered in an Access database.

Determination of evidence level was based on modified Oxford Criteria (Table 1 ). Studies in which evidence level could not be determined on behalf of available information, were discussed with a clinical pharmacologist and a professor in Public Health.

Levels of evidence, Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine (2001) and pharmaco-epidemiological study design

In Table 1 , study-designs, in respectively, Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine (therapy/prevention/aetiology/harm) and in the Pharmaco-epidemiological literature are provided along with the matching evidence levels (right column). In the present review, the evidence levels of the included studies were classified in accordance to these study-designs, as appropriate.

Due to the obvious lack of standard methodology and outcome measures, data could not be statistically summarized. However, prevalences of medication errors were reported for studies in which denominators were accessible. In pre–post studies and controlled studies, only prevalences of medication errors at baseline or from a control group were presented, whereas no prevalences could be calculated in studies using data from reporting systems [ 26 ]. Definitions were analysed with regard to similarities in content leading to the following five categories: (i) studies using the term error; (ii) studies using the NCC MERP definition; (iii) studies using failure; (iv) studies using deviation; and, finally (v) other terms. In each category, definitions from included studies were presented along with study characteristics. Finally, possible tendencies towards associations between definitions and prevalences were examined.

The literature search revealed 203 eligible papers (Fig. 1 ) of which 45 (23%) included a generic definition of medication errors. An additional 30 studies included a stage-specific definition; 22 prescribing, 3 in dispensing, 5 in administering and, finally, 4 studies contained a definition of intravenous errors. However, in 124 studies, no definitions were provided.

Overall characteristics

The 45 included studies were published in 26 different peer-reviewed journals in the period from 1984 to 2006 with half of them in the period 2005–06. The majority of studies were conducted in North America, representing 36 studies; 2 were done in Australia, 6 in Western Europe and, finally, 1 in Asia. The studies were conducted in a variety of clinical settings with almost 50% assessing more than one type of setting e.g. medical and surgical departments. Moreover, 20 studies included only adults, 9 studies only children, 9 studies both adults and children and, finally, 8 studies included other types of participants e.g. nurses and pharmacists. In 13 studies an intervention was addressed of which 9 were technologies in the medication process (e.g. computerized order entry (CPOE) either alone or combined with clinical decision support (CDS) systems, dose dispensing systems and infusion pumps with CDS). Descriptive designs were employed in 37 studies, whereas 2 studies were conducted as randomized clinical controlled studies, 1 as a case–control study and 1 as a prospective cohort study, and, finally, 4 studies were conducted using other designs e.g. case reports. Nine out of 10 studies were classified as evidence level IV or V, and, finally, chart review and reporting systems were the most frequently used methods to detect medication errors.

Prevalence of medication errors

In 21 of 45 studies, it was not possible to determine a prevalence of medication errors due to lack of valid denominators. These were in particular studies using reporting systems, interview and questionnaires as data collection method. Overall, a prevalence of 75% was found, with the majority being below <10% (Tables 2–4 ).

Studies using errors in definition of medication errors

a Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine Levels of Evidence. Abbreviations: P: prescription; T: transcription; D: dispensing; A: administration; CPOE: computerized order entry; CDS: clinical decision support; OE: opportunities for errors; MEOS: medication error outcome scale. b Pre-intervention. c Preventable ADE + potential ADE.

Studies using the NCC MERP definition of medication errors

NCC MERP definition: ‘Any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is in control of the health-care professional, patient or consumer. Such events may be related to professional practice, health-care products, procedures and systems, including prescribing; order communication; product labelling, packaging and nomenclature; compounding; dispensing; distribution; administration; education; monitoring; and use.’ a Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine Levels of Evidence. Abbreviations: P: prescription; T: transcription; D: dispensing; A: administration; CPOE: computerized order entry; CDS: clinical decision support; N/A: not applicable.

Studies using ‘failure, deviation or other’ terms in definition of medication errors

a Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine Levels of Evidence. Abbreviations: AUS: Australia; UK: United Kingdom; P: prescription; T: transcription; D: dispensing; A: administration; CPOE: computerized order entry; CDS: clinical decision support; OE: opportunities for errors; N/A: not applicable; MEOS: medication error outcome scale. b Prevalence from a control group or pre-intervention.

An average of nine error types (min/max: 1/38) were identified in 38 of the 45 studies. In seven studies no error types were included due to study design. The study having one error type, namely, overdose (gentamicin) accounted for the highest prevalence in the review. Unfortunately, it was not possible to retrieve prevalence in the study using the highest number of error types, as data were collected from voluntary reporting. Dosing errors were the most frequent single error type, and in studies including all stages in the medication process, prescribing errors accounted for the highest percentage.

Definitions

Of the 45 definitions, 26 differed in wording and/or content. One definition used harm or potential for harm as a criterion for medication error, whereas one explicitly included intercepted medication errors [ 27–29 ]. Finally, five definitions were limited to deviations between ordered and administered drugs and doses [ 30–34 ]. In all other definitions no restrictions were specified.

A crude categorization of the revealed definitions was performed based on similarities in wording and/or content. Tables 2–4 provide an overview of definitions and characteristics of each study. Table 2 shows 15 definitions using the word ‘error/s’ followed by information about included stages in the medication process. In seven definitions, information regarding injury or intercepted errors is stated. Table 3 reveals characteristics of 17 studies using the definition from NCC MERP [ 22 ]. Finally, Table 4 presents five definitions using failure instead of error; five focusing on deviations between ordered and administered drugs/doses and three using other definitions.

Trends towards association between definition and prevalence

In the first category (Table 2 ), it was possible to ascertain prevalence in all studies ranging from 2 to 75% with the two European studies as the main contributors. In the second category (Table 3 ), which included studies using the definition from NCC MERP, it was possible to retrieve prevalence in 1 out of 17 studies, due to the use of reporting systems. This study revealed a prevalence of 8%. In the third category (Table 4 ) consisting of five studies using the term ‘failure’, it was not possible to provide information about prevalence due to study design and data collection methods. Finally, in the fourth category (Table 4 ), a prevalence of 3–16% was observed in studies focusing on deviations between ordered and administered drugs/doses.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically explore the extent and impact of generic definitions of medication errors in hospital settings. The literature review confirmed an inconsistent use of definitions. However, other aspects have to be considered in order to explain the variation in prevalence of medication errors, as interpretation of the included definitions did not suggest any tendencies.

It is of particular relevance that fewer than half of the studies explicitly defined medication errors either as an overall definition (generic) or a stage/route-specific term. Furthermore, fewer than a quarter presented a generic definition despite that being the main objective of the studies. Thus, the inconsistency in terminology only represents the tip of the iceberg. Additionally, the present review has confirmed that the overall poor understanding of the epidemiology of medication errors can, at least, partly be explained by choice of design, data collection methods and study population, including denominators [ 19–21 , 23 ]. Based on these shortcomings, we have revealed a prevalence of 2–75% in studies that included a generic definition of medication error.

The second important problem is the choice of denominator or study population. It has previously been suggested that to use opportunities for errors rather than number of patients as denominator reduces the risk of case-mix bias [ 26 ]. Here we demonstrated a variety of denominators including drug order, doses, opportunities for errors, patients, nurses, reports and triggers. In addition, the frequent use of a reporting system excluded calculation of valid prevalence in almost half of all the studies thereby increasing the lack of clarity.

Thirdly, the impact of error types should be considered. It could be assumed that increasing the number of error types being measured, would automatically result in higher occurrences of medication errors due to an increased probability of detecting more errors. However, the study with the highest prevalence of errors (75%) in the present review included only one error type, namely, dosing errors, which conflicts with this assumption [ 35 ]. On the other hand, not all error types are mutually exclusive e.g. dosing errors, which inevitably includes all errors resulting in wrong or omitted dose (under-dose, overdose, omission of dose). Thus, the number of error types has to be weighed against type of error and the sensitivity of error detection methods. Unfortunately, the present review did not provide sufficient information on the impact of error types with regard to prevalence.

Finally, choice of data collection method should be considered important. Previously, chart review has been considered as the most appropriate method to detect prescribing errors and direct observation the most sensitive method to detect dispensing and administration errors, as opposed to voluntary reporting, which was found to be the least sensitive method [ 32 , 36 ]. In recent years the availability of computer-generated signals in error detection has increased, which allow an objective detection of all incidents that have been defined as an error in the computer. Thus, it can be assumed that such systems will increase the detection of systematic documented electronic data such as dosing of gentamicin [ 35 ]. In the present review the most frequently applied error detection method was chart review, which might have contributed to an underestimation of the occurrence of medication errors when applied to detection of errors other than prescribing.

Definition and prevalence

Interestingly, definitions, which at first glance appeared to be similar (Table 2 ), turned out to have the widest range in prevalence of medication errors. A closer scrutiny revealed that 10 of 15 studies in this category were affiliated with the same institutions in Boston, USA [ 7 , 15 , 28 , 37–43 ]. In addition, these studies demonstrated the lowest occurrence of medication errors ranging from 2 to 8% regardless of whether intercepted errors were included or not, suggesting consistency in error detection methods. However, prevalence in the two studies from Europe exceeded the American studies by as much as eight times, despite use of virtually identical definitions [ 10 , 35 ]. No obvious circumstances can explain these extreme differences, apart from use of data collection methods, as the study with the highest prevalence used computer-generated signals to detect dosing errors [ 35 ].

The majority of studies used the definition by NCC MERP. Unfortunately, it was only possible to retrieve one valid prevalence of medication errors [ 44 ]. This definition was initially developed for medication error reporting and, therefore, was an obvious choice for studies using reporting systems, which was the case for almost all the studies in this category [ 22 ]. An important drawback to reporting systems is an increased risk of underestimating the occurrence of medication errors due to the reporter's awareness of errors, attitudes towards reporting errors and fear of sanctions [ 45 ]. In addition, reporting systems are by nature denominator free as they do not provide information on the whole population; on the contrary, retrospective fitted denominators, such as time period or admissions, are frequently employed to demonstrate error rates [ 26 ]. Thus, reports of incidence or prevalence in studies using reporting systems should be avoided or interpreted with caution. Unfortunately, this expelled a unique opportunity to compare prevalence in studies using identical definitions.

Surprisingly, only 1 of the 45 definitions restricted medication errors to failures that either result in harm or have the potential to lead to harm [ 27 ]. Contrary to other definitions of medication errors in the present review, this approach relates process and outcome factors within the same definition, which previously has been suggested as minimizing the risk of accepting associations between errors and processes as synonyms for causation [ 46 ]. Moreover, this definition has been tested in an Australian study, in which it proved to be the most robust among other definitions, when evaluated in comparison with different medication error scenarios [ 25 ]. However, due to the design of this study it was not possible to elucidate that a restricted definition would lead to lower occurrences of medication errors compared with more profound definitions [ 15 ].

Finally, definitions that considered a medication error as a deviation between an ordered and administered drug and dose seemed to be more homogeneous with regard to prevalence despite representing different countries and employing different study designs [ 30 , 32–34 , 47 ]. However, these studies predominantly used the same types of denominator (opportunities for errors; doses and orders) as well as the most sensitive and appropriate data collection methods, e.g. direct observation in studies of dispensing and administration errors. A possible explanation for this consistency is the clear-cut limitation to deviations, which might appear simpler and be a less subjective approach in determination of medication errors. However, this approach excludes prescribing errors, as prescriptions serve as the gold standard in these definitions.

Limitations

The aim of this review was to investigate the multiplicity of definitions used in studies having medication errors and/or ADEs as the main objective. Hence, the characteristics and prevalence reported here might not reflect the overall occurrence of medication errors. However, it could be assumed that prevalence ranging from 2 to 75% represents the vast majority of studies in medication errors. Secondly, the literature search was limited to four major databases and restricted to papers in the English language. It is, therefore, possible that studies that would have met the inclusion criteria, were not indexed by these databases or were published in other languages than English. Nevertheless, due to experience from the current literature search, in which studies from a time span of >20 years were included, we assume that studies that might have been unintentionally disregarded in the search strategy would rather have added to the current inconsistency than contributed to clarification of the terminology. Third, the groupings we selected were somewhat arbitrary and this might have affected our chances of seeing an effect.

In the present systematic literature review of 45 studies we have confirmed inconsistency in defining medication errors as well as lack of definitions. Most of the definitions were profound, including minor deviations as well as fatal errors, whereas a single definition was restricted to harmful or potentially harmful errors.

Most importantly, it appears that definitions of medication errors and methods of detection, rather than being reproducible and reliable methods, are subject to individual researcher's preferences. Thus, it is obvious that application of a clear-cut definition, standardized terminology and reliable methods will greatly improve the quality and consistency of medication error findings. Efforts to achieve a commonly accepted definition that defines the scope and content is required in future studies.

We would like to thank, Prof. D.W. Bates, Harvard Medical School and Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA, for commenting on the present article.

Google Scholar

- medication errors

Supplementary data

Email alerts, citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1464-3677

- Print ISSN 1353-4505

- Copyright © 2024 International Society for Quality in Health Care and Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Libraries | Research Guides

Literature reviews, what is a literature review, learning more about how to do a literature review.

- Planning the Review

- The Research Question

- Choosing Where to Search

- Organizing the Review

- Writing the Review

A literature review is a review and synthesis of existing research on a topic or research question. A literature review is meant to analyze the scholarly literature, make connections across writings and identify strengths, weaknesses, trends, and missing conversations. A literature review should address different aspects of a topic as it relates to your research question. A literature review goes beyond a description or summary of the literature you have read.

- Sage Research Methods Core Collection This link opens in a new window SAGE Research Methods supports research at all levels by providing material to guide users through every step of the research process. SAGE Research Methods is the ultimate methods library with more than 1000 books, reference works, journal articles, and instructional videos by world-leading academics from across the social sciences, including the largest collection of qualitative methods books available online from any scholarly publisher. – Publisher

- Next: Planning the Review >>

- Last Updated: Jan 17, 2024 10:05 AM

- URL: https://libguides.northwestern.edu/literaturereviews

An official website of the Department of Health & Human Services

- Search All AHRQ Sites

- Email Updates

1. Use quotes to search for an exact match of a phrase.

2. Put a minus sign just before words you don't want.

3. Enter any important keywords in any order to find entries where all these terms appear.

- The PSNet Collection

- All Content

- Perspectives

- Current Weekly Issue

- Past Weekly Issues

- Curated Libraries

- Clinical Areas

- Patient Safety 101

- The Fundamentals

- Training and Education

- Continuing Education

- WebM&M: Case Studies

- Training Catalog

- Submit a Case

- Improvement Resources

- Innovations

- Submit an Innovation

- About PSNet

- Editorial Team

- Technical Expert Panel

How are medication errors defined? A systematic literature review of definitions and characteristics.

Lisby M, Nielsen LP, Brock B, et al. How are medication errors defined? A systematic literature review of definitions and characteristics. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2010;22(6). doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzq059.

This systematic review found wide variation in how medication errors are defined between studies. This variation has significant implications for determining the prevalence of medication errors. Prior commentaries have noted the need for standardized, universally applicable definitions of adverse drug events.

How should medication errors be defined? Development and test of a definition. May 30, 2012

Errors in the medication process: frequency, type, and potential clinical consequences. March 6, 2005

Identifying high-risk medication: a systematic literature review. August 13, 2014

Case study: getting boards on board at Allen Memorial Hospital, Iowa Health System. April 2, 2008

Association of hospital participation in a regional trauma quality improvement collaborative with patient outcomes. June 20, 2018

Selection of indicators for continuous monitoring of patient safety: recommendations of the project 'safety improvement for patients in Europe.' June 10, 2009

Novel analysis of clinically relevant diagnostic errors in point-of-care devices. October 19, 2011

Measuring patient safety climate: a review of surveys. October 12, 2005

National Patient Safety Foundation agenda for research and development in patient safety. March 27, 2005

Physician assistants and the disclosure of medical error. June 18, 2014

Insulin dosing error in a patient with severe hyperkalemia. January 17, 2018

Effective interventions and implementation strategies to reduce adverse drug events in the Veterans Affairs (VA) system. February 20, 2008

Implementing an error disclosure coaching model: a multicenter case study. February 22, 2017

Building safer systems by ecological design: using restoration science to develop a medication safety intervention. April 12, 2006

Disclosing adverse events in clinical practice: the delicate act of being open. February 2, 2022

Use of a safety climate questionnaire in UK health care: factor structure, reliability and usability. November 22, 2006

Using standardised patients in an objective structured clinical examination as a patient safety tool. March 6, 2005

Time of day effects on the incidence of anesthetic adverse events. August 23, 2006

Discrimination, abuse, harassment, and burnout in surgical residency training. November 20, 2019

Effect of computerized physician order entry and a team intervention on prevention of serious medication errors. March 27, 2005

Relationship between tort claims and patient incident reports in the Veterans Health Administration. April 21, 2005

An intervention to decrease patient identification band errors in a children's hospital. May 12, 2010

"Every error counts": a web-based incident reporting and learning system for general practice. August 20, 2008

Effects of skilled nursing facility structure and process factors on medication errors during nursing home admission. November 5, 2014

Frequency and type of situational awareness errors contributing to death and brain damage: a closed claims analysis. May 24, 2017

A simulation design for research evaluating safety innovations in anaesthesia. January 28, 2009

Teaching teamwork during the Neonatal Resuscitation Program: a randomized trial. June 20, 2007

Implementation of bar-code medication administration to reduce patient harm. February 20, 2019

Design and implementation of a point-of-care computerized system for drug therapy in Stockholm metropolitan health region--bridging the gap between knowledge and practice. August 29, 2007

Analysis of suicides reported as adverse events in psychiatry resulted in nine quality improvement initiatives. July 21, 2021

Nil per os orders for imaging: a teachable moment. September 27, 2017

An observational study of direct oral anticoagulant awareness indicating inadequate recognition with potential for patient harm. April 13, 2016

Clinical pharmacists and inpatient medical care: a systematic review. May 17, 2006

Safety learning among young newly employed workers in three sectors: a challenge to the assumed order of things. November 17, 2021

Competencies for patient safety and quality improvement: a synthesis of recommendations in influential position papers. April 6, 2016

Patterns of potential opioid misuse and subsequent adverse outcomes in Medicare, 2008 to 2012. June 6, 2018

Video capture of clinical care to enhance patient safety. March 1, 2006

Do faculty and resident physicians discuss their medical errors? October 15, 2008

Getting teams to talk: development and pilot implementation of a checklist to promote interprofessional communication in the OR. October 19, 2005

Why psychiatry is different--challenges and difficulties in managing a nosocomial outbreak of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in hospital care. January 20, 2021

The "Seven Pillars" response to patient safety incidents: effects on medical liability processes and outcomes. September 7, 2016

Regional surveillance of emergency-department visits for outpatient adverse drug events. April 22, 2009

Errors with concentrated epinephrine in otolaryngology. September 3, 2008

Doctors debate safety of their white coats. December 2, 2015

Multicentre study to develop a medication safety package for decreasing inpatient harm from omission of time-critical medications. March 4, 2015

Strengthening leadership as a catalyst for enhanced patient safety culture: a repeated cross-sectional experimental study. June 22, 2016

Errors during the preparation of drug infusions: a randomized controlled trial. August 22, 2012

The impact of a tele-ICU on provider attitudes about teamwork and safety climate. May 26, 2010

Non-intercepted dose errors in prescribing antineoplastic treatment: a prospective, comparative cohort study. March 11, 2015

Polypharmacy in hospitalized older adult cancer patients: experience from a prospective, observational study of an oncology-acute care for elders unit. August 5, 2009

Anaesthetists' management of oxygen pipeline failure: room for improvement. January 31, 2007

Attitudes and barriers to incident reporting: a collaborative hospital study. February 22, 2006

Using simulation to identify sources of medical diagnostic error in child physical abuse. April 27, 2016

An alternative strategy for studying adverse events in medical care. March 27, 2005

A prospective study of patient safety in the operating room. February 22, 2006

Wrong-site sinus surgery in otolaryngology. August 11, 2010

Reducing serious safety events and priority hospital-acquired conditions in a pediatric hospital with the implementation of a patient safety program. June 6, 2018

The SAGES Fundamental Use of Surgical Energy program (FUSE): history, development, and purpose. February 14, 2018

Does a suggested diagnosis in a general practitioners' referral question impact diagnostic reasoning: an experimental study. April 27, 2022

Adverse-event-reporting practices by US hospitals: results of a national survey. January 7, 2009

Involvement of parents in critical incidents in a neonatal-paediatric intensive care unit. December 16, 2009

Using computerized virtual cases to explore diagnostic error in practicing physicians. February 13, 2019

The role of housestaff in implementing medication reconciliation on admission at an academic medical center. June 16, 2010

The Safety Attitudes Questionnaire: psychometric properties, benchmarking data, and emerging research. April 19, 2006

National Partnership for Maternal Safety: Consensus Bundle on Venous Thromboembolism. December 7, 2016

Enhancing psychological safety in mental health services. June 9, 2021

Teamwork behaviours and errors during neonatal resuscitation. March 24, 2010

The use of medical emergency teams in medical and surgical patients: impact of patient, nurse and organisational characteristics. October 29, 2008

Relationship between complaints and quality of care in New Zealand: a descriptive analysis of complainants and non-complainants following adverse events. February 15, 2006

Augmenting health care failure modes and effects analysis with simulation. March 5, 2014

Medication safety program reduces adverse drug events in a community hospital. June 22, 2005

Nurses' perspective on a serious adverse drug event. March 6, 2005

Disclosing large scale adverse events in the US Veterans Health Administration: lessons from media responses. April 13, 2016

Beyond "see one, do one, teach one": toward a different training paradigm. February 25, 2009

The experiences of risk managers in providing emotional support for health care workers after adverse events. May 11, 2016

Risk managers' descriptions of programs to support second victims after adverse events. May 13, 2015

Interprofessional education in team communication: working together to improve patient safety. March 27, 2013

Effect of an in-hospital multifaceted clinical pharmacist intervention on the risk of readmission: a randomized clinical trial. February 7, 2018

Preventable errors in organ transplantation: an emerging patient safety issue? July 11, 2012

Levels of agreement on the grading, analysis and reporting of significant events by general practitioners: a cross-sectional study. October 29, 2008

The impact of trained assistance on error rates in anaesthesia: a simulation-based randomised controlled trial. February 25, 2009

The effect of executive walk rounds on nurse safety climate attitudes: a randomized trial of clinical units. April 27, 2005

Association of surgical resident wellness with medical errors and patient outcomes. May 6, 2020

Relationship between patient complaints and surgical complications. February 15, 2006

Error rating tool to identify and analyse technical errors and events in laparoscopic surgery. September 11, 2013

The influence of standardisation and task load on team coordination patterns during anaesthesia inductions. April 29, 2009

Incident reporting system does not detect adverse drug events: a problem for quality improvement. March 27, 2005

A systematic review of clinical decision support systems for clinical oncology practice. May 15, 2019

Development and validation of a taxonomy of adverse handover events in hospital settings. February 18, 2015

Evaluation of reasons why surgical residents exceeded 2011 duty hour requirements when offered flexibility. June 20, 2018

Error, stress, and teamwork in medicine and aviation: cross sectional surveys. December 21, 2005

Readiness for organisational change among general practice staff. April 28, 2010

Universal surveillance for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in 3 affiliated hospitals. April 2, 2008

The costs of adverse drug events in hospitalized patients. March 27, 2005

Medication administration discrepancies persist despite electronic ordering. November 28, 2007

A family-centered rounds checklist, family engagement, and patient safety: a randomized trial. May 31, 2017

Improving team information sharing with a structured call-out in anaesthetic emergencies: a randomized controlled trial. March 12, 2014

Communication failures contributing to patient injury in anaesthesia malpractice claims. September 1, 2021

Are informed policies in place to promote safe and usable EHRs? A cross-industry comparison. March 8, 2017

Evaluation of adverse drug events and medication discrepancies in transitions of care between hospital discharge and primary care follow-up. October 29, 2014

Thematic reviews of patient safety incidents as a tool for systems thinking: a quality improvement report. May 17, 2023

Driving Learning and Improvement After RCA2 Event Reviews. January 26, 2023 - January 26, 2023

HSIB Education. October 19, 2022

Interventions to reduce medication dispensing, administration, and monitoring errors in pediatric professional healthcare settings: a systematic review. September 29, 2021

Critical incidents involving the medical emergency team: a 5-year retrospective assessment for healthcare improvement. April 28, 2021

Suicide as an incident of severe patient harm: a retrospective cohort study of investigations after suicide in Swedish healthcare in a 13-year perspective. March 31, 2021

Learning from incident reporting? Analysis of incidents resulting in patient injuries in a web-based system in Swedish health care. December 9, 2020

How incident reporting systems can stimulate social and participative learning: a mixed-methods study. September 2, 2020

Register-based research of adverse events revealing incomplete records threatening patient safety. August 19, 2020

Identifying no-harm incidents in home healthcare: a cohort study using trigger tool methodology. August 5, 2020

Apparent cause analysis: a safety tool. May 20, 2020

Medical teamwork and the evolution of safety science: a critical review. March 11, 2020

The Field Guide to Human Error Investigations, Third Edition. August 24, 2017

Monitoring the anaesthetist in the operating theatre—professional competence and patient safety. March 1, 2017

Measurement of patient safety: a systematic review of the reliability and validity of adverse event detection with record review. September 28, 2016

Is there evidence for a better health care for cancer patients after a second opinion? A systematic review. September 28, 2016

Healthcare staff wellbeing, burnout, and patient safety: a systematic review. August 24, 2016

Performance of the Global Assessment of Pediatric Patient Safety (GAPPS) tool. June 15, 2016

Vaccination errors in general practice: creation of a preventive checklist based on a multimodal analysis of declared errors. June 15, 2016

Medical error—the third leading cause of death in the US. May 11, 2016

Patients' views of adverse events in primary and ambulatory care: a systematic review to assess methods and the content of what patients consider to be adverse events. February 17, 2016

Aviation and healthcare: a comparative review with implications for patient safety. February 3, 2016

Interorganizational complexity and organizational accident risk: a literature review. November 25, 2015

Interventions to reduce nurses' medication administration errors in inpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. September 30, 2015

The influence of context on the effectiveness of hospital quality improvement strategies: a review of systematic reviews. September 16, 2015

Ethical issues in patient safety research: a systematic review of the literature. September 9, 2015

"First, know thyself": cognition and error in medicine. June 3, 2015

Insulin pump risks and benefits: a clinical appraisal of pump safety standards, adverse event reporting, and research needs: a joint statement of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes and the American Diabetes Association Diabetes Technology Working Group. May 6, 2015

Hospital organisation, management, and structure for prevention of health-care-associated infection: a systematic review and expert consensus. March 11, 2015

Peer review of medical practices: missed opportunities to learn. January 28, 2015

Connect With Us

Sign up for Email Updates

To sign up for updates or to access your subscriber preferences, please enter your email address below.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

5600 Fishers Lane Rockville, MD 20857 Telephone: (301) 427-1364

- Accessibility

- Disclaimers

- Electronic Policies

- HHS Digital Strategy

- HHS Nondiscrimination Notice

- Inspector General

- Plain Writing Act

- Privacy Policy

- Viewers & Players

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- The White House

- Don't have an account? Sign up to PSNet

Submit Your Innovations

Please select your preferred way to submit an innovation.

Continue as a Guest

Track and save your innovation

in My Innovations

Edit your innovation as a draft

Continue Logged In

Please select your preferred way to submit an innovation. Note that even if you have an account, you can still choose to submit an innovation as a guest.

Continue logged in

New users to the psnet site.

Access to quizzes and start earning

CME, CEU, or Trainee Certification.

Get email alerts when new content

matching your topics of interest

in My Innovations.

The Quintessence of Basic and Clinical Research and Scientific Publishing pp 645–656 Cite as

Literature Reviews: An Overview of Systematic, Integrated, and Scoping Reviews

- John R. Turner 4

- First Online: 01 October 2023

698 Accesses

Literature reviews are a main part of the research process. Literature Reviews can be stand-alone research projects, or they can be part of a larger research study. In both cases, literature reviews must follow specific guidelines so they can meet the rigorous requirements for being classified as a scientific contribution. More importantly, these reviews must be transparent so that they can be replicated or reproduced if desired. The rigorous requirements set out by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) aim to support researchers in conducting literature reviews as well as address the replication crisis that has challenged scientific disciplines over the past decade. The current chapter identifies some of the requirements along with highlighting different types of reviews and recommendations for conducting a rigorous review.

- Literature review

- Integrated review

- Systematic review

- Scoping review

- Cooper’s taxonomy

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Begley GC, Ioannidis JPA (2015) Reproducibility in science: improving the standard for basic and preclinical research. Circ Res 116:116–126. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303819

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Romero F (2019) Philosophy of science and the replicability crisis. Philos Compass 14:e12633. https://doi.org/10.1111/phc3.12633

Article Google Scholar

Van Bavel JJ, Mende-Siedlecki P, Brady WJ, Reinero DA (2016) Contextual sensitivity in scientific reproducibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:6454–6459. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1521897113

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ioannidis JPA (2012) Why science is not necessarily self-correcting. Perspect Psychol Sci 7:645–654. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612464056

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bollen K, Cacioppo JT, Kaplan RM, Krosnick JA, Olds JL (2015) Social, behavioral, and economic sciences perspectives on robust and reliable science. https://www.nsf.gov/sbe/AC_Materials/SBE_Robust_and_Reliable_Research_Report.pdf . Accessed 15 Sept 2022

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD et al (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Imel S (2011) Writing a literature review. In: Tonette RS, Hatcher T (eds) The handbook of scholarly writing and publishing. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA, pp 145–160

Google Scholar

Boote DN, Beile P (2005) Scholars before researchers: on the centrality of the dissertation literature review in research preparation. Educ Res 34:3–15. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X034006003

Bryman A (2008) Social research methods. Oxford University Press, New York, NY

Taylor D (n.d.) The literature review: a few tips on conducting it. https://advice.writing.utoronto.ca/types-of-writing/literature-review/ . Accessed 1 Oct 2022

Torraco RJ (2005) Writing integrative literature reviews: guidelines and examples. Hum Resour Dev Rev 4(3):356–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484305278283

Cooper HM (1988) Organizing knowledge syntheses: a taxonomy of literature reviews. Knowl Soc 1:104–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03177550

Cooper H (2010) Research synthesis and meta-analysis. 4th ed. Applied social research methods series, vol 2. Sage, Los Angelas, CA

Cooper H (2003) Psychological bulletin: editorial. Psychol Bull 129:3–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.3

Hart C (2018) Doing a literature review: releasing the research imagination, 2nd edn. Sage, Los Angelas, CA

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien K, Colquhoun H, Kastner M et al (2016) A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 16:15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-016-0116-4

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Torraco RJ (2016) Writing integrative literature reviews: using the past and present to explore the future. Hum Resour Dev Rev 15:404–428. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484316671606

Doty DH, Glick WH (1994) Typologies as a unique form of theory building: toward improved understanding and modeling. Acad Manag Rev 19:230–251. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.1994.9410210748

Leedy PD, Ormrod JE (2005) Practical research: planning and design, 8th edn. Pearson, Upper Saddle River, NJ

Ragins BR (2012) Reflections on the craft of clear writing. Acad Manag Rev 37:493–501. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2012.0165

King S (2000) On writing: a memoir of the craft. Scribner, New York, NY

Torraco RJ (2016) Research methods for theory building in applied disciplines: a comparative analysis. Adv Dev Hum Resour 4:355–376. https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422302043008

Pendleton-Jullian AM, Brown JS (2018) Design unbound: designing for emergence in a white water world. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Book Google Scholar

Simon HA (2019) The sciences of the artificial [reissue of 3rd ed.]. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Klir GJ (2009) W. Ross Ashby: a pioneer of systems science. Int J Gen Syst 38:175–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/03081070802601434

Reen J (2020) The evolution of knowledge: rethinking science for the anthropocene. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

Download references

Conflict of Interest

No conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of North Texas, Denton, TX, USA

John R. Turner

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to John R. Turner .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Retired Senior Expert Pharmacologist at the Office of Cardiology, Hematology, Endocrinology, and Nephrology, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD, USA

Gowraganahalli Jagadeesh

Professor & Director, Research Training and Publications, The Office of Research and Development, Periyar Maniammai Institute of Science & Technology (Deemed to be University), Vallam, Tamil Nadu, India

Pitchai Balakumar

Division Cardiology & Nephrology, Office of Cardiology, Hematology, Endocrinology and Nephrology, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD, USA

Fortunato Senatore

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Turner, J.R. (2023). Literature Reviews: An Overview of Systematic, Integrated, and Scoping Reviews. In: Jagadeesh, G., Balakumar, P., Senatore, F. (eds) The Quintessence of Basic and Clinical Research and Scientific Publishing. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-1284-1_38

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-1284-1_38

Published : 01 October 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-99-1283-4

Online ISBN : 978-981-99-1284-1

eBook Packages : Biomedical and Life Sciences Biomedical and Life Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Literature Reviews

Introduction, what is a literature review.

- Literature Reviews for Thesis or Dissertation

- Stand-alone and Systemic Reviews

- Purposes of a Literature Review

- Texts on Conducting a Literature Review

- Identifying the Research Topic

- The Persuasive Argument

- Searching the Literature

- Creating a Synthesis

- Critiquing the Literature

- Building the Case for the Literature Review Document

- Presenting the Literature Review

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Higher Education Research

- Meta-Analysis and Research Synthesis in Education

- Methodologies for Conducting Education Research

- Mixed Methods Research

- Philosophy of Education

- Politics of Education

- Qualitative Data Analysis Techniques

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Gender, Power, and Politics in the Academy

- Girls' Education in the Developing World

- Non-Formal & Informal Environmental Education

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Literature Reviews by Lawrence A. Machi , Brenda T. McEvoy LAST REVIEWED: 21 April 2021 LAST MODIFIED: 27 October 2016 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199756810-0169

Literature reviews play a foundational role in the development and execution of a research project. They provide access to the academic conversation surrounding the topic of the proposed study. By engaging in this scholarly exercise, the researcher is able to learn and to share knowledge about the topic. The literature review acts as the springboard for new research, in that it lays out a logically argued case, founded on a comprehensive understanding of the current state of knowledge about the topic. The case produced provides the justification for the research question or problem of a proposed study, and the methodological scheme best suited to conduct the research. It can also be a research project in itself, arguing policy or practice implementation, based on a comprehensive analysis of the research in a field. The term literature review can refer to the output or the product of a review. It can also refer to the process of Conducting a Literature Review . Novice researchers, when attempting their first research projects, tend to ask two questions: What is a Literature Review? How do you do one? While this annotated bibliography is neither definitive nor exhaustive in its treatment of the subject, it is designed to provide a beginning researcher, who is pursuing an academic degree, an entry point for answering the two previous questions. The article is divided into two parts. The first four sections of the article provide a general overview of the topic. They address definitions, types, purposes, and processes for doing a literature review. The second part presents the process and procedures for doing a literature review. Arranged in a sequential fashion, the remaining eight sections provide references addressing each step of the literature review process. References included in this article were selected based on their ability to assist the beginning researcher. Additionally, the authors attempted to include texts from various disciplines in social science to present various points of view on the subject.

Novice researchers often have a misguided perception of how to do a literature review and what the document should contain. Literature reviews are not narrative annotated bibliographies nor book reports (see Bruce 1994 ). Their form, function, and outcomes vary, due to how they depend on the research question, the standards and criteria of the academic discipline, and the orthodoxies of the research community charged with the research. The term literature review can refer to the process of doing a review as well as the product resulting from conducting a review. The product resulting from reviewing the literature is the concern of this section. Literature reviews for research studies at the master’s and doctoral levels have various definitions. Machi and McEvoy 2016 presents a general definition of a literature review. Lambert 2012 defines a literature review as a critical analysis of what is known about the study topic, the themes related to it, and the various perspectives expressed regarding the topic. Fink 2010 defines a literature review as a systematic review of existing body of data that identifies, evaluates, and synthesizes for explicit presentation. Jesson, et al. 2011 defines the literature review as a critical description and appraisal of a topic. Hart 1998 sees the literature review as producing two products: the presentation of information, ideas, data, and evidence to express viewpoints on the nature of the topic, as well as how it is to be investigated. When considering literature reviews beyond the novice level, Ridley 2012 defines and differentiates the systematic review from literature reviews associated with primary research conducted in academic degree programs of study, including stand-alone literature reviews. Cooper 1998 states the product of literature review is dependent on the research study’s goal and focus, and defines synthesis reviews as literature reviews that seek to summarize and draw conclusions from past empirical research to determine what issues have yet to be resolved. Theoretical reviews compare and contrast the predictive ability of theories that explain the phenomenon, arguing which theory holds the most validity in describing the nature of that phenomenon. Grant and Booth 2009 identified fourteen types of reviews used in both degree granting and advanced research projects, describing their attributes and methodologies.

Bruce, Christine Susan. 1994. Research students’ early experiences of the dissertation literature review. Studies in Higher Education 19.2: 217–229.

DOI: 10.1080/03075079412331382057

A phenomenological analysis was conducted with forty-one neophyte research scholars. The responses to the questions, “What do you mean when you use the words literature review?” and “What is the meaning of a literature review for your research?” identified six concepts. The results conclude that doing a literature review is a problem area for students.

Cooper, Harris. 1998. Synthesizing research . Vol. 2. 3d ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

The introductory chapter of this text provides a cogent explanation of Cooper’s understanding of literature reviews. Chapter 4 presents a comprehensive discussion of the synthesis review. Chapter 5 discusses meta-analysis and depth.

Fink, Arlene. 2010. Conducting research literature reviews: From the Internet to paper . 3d ed. Los Angeles: SAGE.

The first chapter of this text (pp. 1–16) provides a short but clear discussion of what a literature review is in reference to its application to a broad range of social sciences disciplines and their related professions.

Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. 2009. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal 26.2: 91–108. Print.

DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

This article reports a scoping review that was conducted using the “Search, Appraisal, Synthesis, and Analysis” (SALSA) framework. Fourteen literature review types and associated methodology make up the resulting typology. Each type is described by its key characteristics and analyzed for its strengths and weaknesses.

Hart, Chris. 1998. Doing a literature review: Releasing the social science research imagination . London: SAGE.

Chapter 1 of this text explains Hart’s definition of a literature review. Additionally, it describes the roles of the literature review, the skills of a literature reviewer, and the research context for a literature review. Of note is Hart’s discussion of the literature review requirements for master’s degree and doctoral degree work.

Jesson, Jill, Lydia Matheson, and Fiona M. Lacey. 2011. Doing your literature review: Traditional and systematic techniques . Los Angeles: SAGE.