- Explore Options

Research career paths

Sign in for full access to careers in medicine’s tools, learn if you are eligible for a free subscription.

- Academic medicine

Careers in Medicine (“CiM”) is an online resource owned and operated by the Association of American Medical Colleges (“AAMC”). After purchase, the CiM online content (“CiM Material”) is made available through https://careersinmedicine.aamc.org (the “Site”). Acceptance of Terms of Use These terms and conditions (“Terms”) govern your purchase and use of the CiM Material. In addition, the AAMC Website Terms and Conditions are incorporated herein by reference, if a conflict exists these Terms shall take precedence. If you do not accept these Terms, do not purchase the CiM Material nor use the services provided through the Site. By visiting the Site, you also agree we may revise these Terms from time to time without providing notice to you. Your continued use of the Site after such revision marks your acceptance of the Terms as revised. We recommend you review these Terms regularly as they are subject to change. Personal Information Personal information submitted in connection with the use of the CiM Material is subject to the AAMC Privacy Statement, as it may be amended from time to time, which is incorporated into these Terms by reference. Your CiM assessment and exercise results are confidential. However, designated school representatives can view individual registration, login, and assessment dates. Permitted Use and Access The AAMC grants you a personal, non-exclusive, non-transferrable, limited privilege to access the Site and CiM Material. Your permitted use of the Site and CiM Material is limited solely to career planning and decision making. No other use of the Site or CiM Material is permitted under these Terms. Your access to the Site is limited to the forward-facing portions of the Site and CIM Material webpages. Unauthorized access includes, but is not limited to, attempts to gain access to any portion or feature of the Site or CIM Material, or any other systems or networks connected to the Site, CIM Material, or associated server, or to any of the services offered on or through the Site or CIM Material, by hacking, password mining, application or scripts or other electronic means, or any other illegitimate means. The AAMC reserves the right to refuse service or provide CiM Material access to any person or entity at our sole discretion.

- Mayo Clinic Careers

- Anesthesiology

- Dermatology

- Emergency Medicine

- Family Medicine

- Internal Medicine

- Lung Transplant

- Psychiatry & Psychology

- Nurse Practitioner & Physician Assistant

- Ambulance Service

- Clinical Labs

- Radiology Imaging

- Clinical Research Coordinator

- Respiratory Care

- Senior Care

- Surgical Services

- Travel Surgical Tech

- Practice Operations

- Administrative Fellowship Program

- Administrative Internship Program

- Career Exploration

- Nurse Residency and Training Program

- Nursing Intern/Extern Programs

- Residencies & Fellowships (Allied Health)

- Residencies & Fellowships (Medical)

- SkillBridge Internship Program

- Training Programs & Internships

- Diversity, Equity & Inclusion

- Employees with Disabilities

Life-changing careers

Search life-changing careers.

Search by Role or Keyword

Enter Location

- United States Applicants

- United Kingdom Applicants

- United Arab Emirate Applicants

- Current Employees

To improve health care and offer new solutions and hope for patients, Mayo Clinic conducts basic, translational, clinical and epidemiological research at its campuses in Arizona, Florida and Minnesota and throughout Mayo Clinic Health System. Researchers investigate today’s medical mysteries, generating new knowledge and translating discoveries into therapies to advance patient care. You will become a vital member of a dynamic health care team, where you’ll experience the exceptional environment of one of the world’s cutting edge health care institutions.

You will discover a culture of teamwork, professionalism and mutual respect, with colleagues who inspire you to stretch and grow. Most of all, you will find a career that can change your life!

Research Jobs

- Intern Undergraduate – Zhang Lab 330817 Research Jacksonville, Florida

- Research Technologist - Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome 329985 Research Rochester, Minnesota

- Technical Specialist - Biorepository 330309 Research Phoenix, Arizona

- Associate Research Protocol Specialist - Remote 329592 Research

- Research Technologist - Hematology Research -Limited Tenure 330583 Research Rochester, Minnesota

- Research Technologist-Hematology Research - Limited Tenure 330544 Research Rochester, Minnesota

- Intern - Bioinformatics PHD 330427 Research Jacksonville, Florida

- Program Coordinator- Research 330512 Research Jacksonville, Florida

- Graduate Intern-Otolaryngology 330410 Research Jacksonville, Florida

- Clinical Data Associate- Research 330675 Research Jacksonville, Florida

Equal opportunity

All qualified applicants will receive consideration for employment without regard to race, color, religion, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, national origin, protected veteran status, or disability status. Learn more about "EEO is the Law." Mayo Clinic participates in E-Verify and may provide the Social Security Administration and, if necessary, the Department of Homeland Security with information from each new employee's Form I-9 to confirm work authorization.

Reasonable accommodations

Mayo Clinic provides reasonable accommodations to individuals with disabilities to increase opportunities and eliminate barriers to employment. If you need a reasonable accommodation in the application process; to access job postings, to apply for a job, for a job interview, for pre-employment testing, or with the onboarding process, please contact HR Connect at 507-266-0440 or 888-266-0440.

Job offers are contingent upon successful completion of a post offer placement assessment including a urine drug screen, immunization review and tuberculin (TB) skin testing, if applicable.

Recruitment Fraud

Learn more about recruitment fraud and job scams

Advertising

Mayo Clinic is a not-for-profit organization and proceeds from Web advertising help support our mission. Mayo Clinic does not endorse any of the third party products and services advertised.

Advertising and sponsorship policy | Advertising and sponsorship opportunities

Reprint permissions

A single copy of these materials may be reprinted for noncommercial personal use only. "Mayo," "Mayo Clinic," "MayoClinic.org," "Mayo Clinic Healthy Living," and the triple-shield Mayo Clinic logo are trademarks of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.

Any use of this site constitutes your agreement to the Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy linked below.

Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy | Notice of Privacy Practices | Notice of Nondiscrimination

© 1998-2024 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved.

Join Our Talent Community

Sign up, stay connected and get opportunities that match your skills sent right to your inbox

Email Address

Phone Number

Upload Resume/CV (Must be under 1MB) Remove

Job Category* Select One Advanced Practice Providers Business Education Engineering Executive Facilities Support Global Security Housekeeping Information Technology Internship Laboratory Nursing Office Support Patient Care - Other Pharmacy Phlebotomy Physician Post Doctoral Radiology Imaging Research Scientist Surgical Services Therapy

Location Select Location Albert Lea, Minnesota Arcadia, Wisconsin Austin, Minnesota Barron, Wisconsin Bloomer, Wisconsin Caledonia, Minnesota Cannon Falls, Minnesota Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin Decorah, Iowa Duluth, Minnesota Eau Claire, Wisconsin Fairmont, Minnesota Faribault, Minnesota Holmen, Wisconsin Jacksonville, Florida Kasson, Minnesota La Crosse, Wisconsin Lake City, Minnesota London, England Mankato, Minnesota Menomonie, Wisconsin Minneapolis-St. Paul-Bloomington, Minnesota New Prague, Minnesota Onalaska, Wisconsin Osseo, Wisconsin Owatonna, Minnesota Phoenix, Arizona Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin Red Wing, Minnesota Rice Lake, Wisconsin Rochester, Minnesota Saint Cloud, Minnesota Saint James, Minnesota Saint Peter, Minnesota Scottsdale, Arizona Sparta, Wisconsin Waseca, Minnesota Zumbrota, Minnesota

Area of Interest Select One Nursing Research Laboratory Medicine & Pathology Radiology Surgery Pharmacy Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation Facilities Psychiatry & Psychology Licensed Practical Nurse (LPN) Surgical Technician Finance Cardiovascular Medicine Respiratory Therapy General Services Emergency Medicine Neurology Mayo Collaborative Services Environmental Services Ambulance Services Social Work Anesthesiology & Perioperative Medicine Cardiovascular Surgery Family Medicine Gastroenterology & Hepatology Information Technology Medical Oncology Global Security International Orthopedics Urology Mayo Clinic Laboratories Radiation Oncology Surgical Assistant Healthcare Technology Management Transplant Critical Care Hematology Hospital Internal Medicine Obstetrics & Gynecology Office Support Pediatrics Education Ophthalmology Administration Artificial Intelligence & Informatics Biochemistry & Molecular Biology Desk Operations Linen & Central Services Oncology Senior Care Community Internal Medicine Engineering Pulmonary/Sleep Medicine Clinical Nutrition Dermatology Digital Hospice & Palliative Care Otolaryngology (ENT) Patient Scheduling Physiology & Biomedical Engineering Clinical Genomics Development/Philanthropy Endocrinology General Internal Medicine Molecular Medicine Rheumatology Sports Medicine Business Development Cancer Center Comparative Medicine Epidemiology Infectious Diseases Mayo Clinic Platform Neurologic Surgery Travel Immunology Nephrology & Hypertension Neurosciences Quality Risk Management Volunteer Services Addiction Services Cancer Biology Clinical Trials & Biostatistics Dental Specialities Executive Office Health Care Delivery Research Legal Marketing Molecular Pharmacology & Experimental Therapeutics Primary Care Regenerative Biotherapeutics Spiritual Care Center for Individualized Medicine Communications Computational Biology Geriatric Medicine & Gerontology Health Information Management Services Informatics Information Security Occupational/Preventative Medicine Pain Medicine Spine Center Women's Health

Confirm Email

By submitting your information, you consent to receive email communication from Mayo Clinic.

Careers in Medical Research

New section.

Learn more about careers in medical research.

If you have an interest in scientific exploration and a desire to break new ground in medical knowledge, a career in medical research might be for you.

MD-PhD programs provide training in both medicine and research. They are specifically designed for those who want to become research physicians.

The AAMC MD/PhD section is committed to recruiting and training a diverse Physician-Scientist workforce and an inclusive learning and working environment.

Biomedical scientists bridge the gap between the basic sciences and medicine. The PhD degree is the gateway to a career in biomedical research.

Transforming the understanding and treatment of mental illnesses.

Información en español

Celebrating 75 Years! Learn More >>

- About the Director

- Advisory Boards and Groups

- Strategic Plan

- Offices and Divisions

Careers at NIMH

- Staff Directories

- Getting to NIMH

NIMH is looking for a wide range of passionate and inspired administrative and scientific people to support our mission of transforming the understanding and treatment of mental illnesses through basic and clinical research, paving the way for prevention, recovery, and cure.

Email Updates

Sign up to receive email updates about NIMH job opportunities.

Type email address...

Andrea Horvath Marques, M.D., Ph.D., M.P.H.

Public Health Psychiatrist Global Mental Health Dissemination & Implementation Research Program

With a diverse background in clinical practice, research, and public health, Andrea oversees global mental health projects focusing on dissemination and implementation science, suicide prevention, and integrating mental health care into health care systems. Her passion lies in making a difference worldwide and providing evidence-based mental health care through NIMH-supported research.

Working at NIMH

Diversity and inclusion in the biomedical research workforce spurs collaboration and innovation, improves the quality of research, and increases the likelihood that research outcomes will benefit everyone. We are committed to prioritizing and promoting diversity and inclusion in our science and our scientific workforce to achieve this mission.

The People Behind NIMH

At NIMH, our employees are the driving force that brings our mission to life. From supporting and training the next generation of scientists to exploring the mysteries of the brain, meet some of the passionate individuals who are working to make people's lives better.

Opportunities at NIMH

There are a wide range of opportunities available at NIMH.

Extramural Research Program (ERP) careers are scientific research positions that support research grants and contracts across the country through the extramural research programs.

Intramural Research Program (IRP) careers are scientific research or clinical positions in the internal research division of NIMH that may involve lab work or patient care. Over 40 research groups at NIMH conduct basic neuroscience research and clinical investigations of mental illnesses, brain function, and behavior.

Extramural Research Program Opportunities

- Clinical Informatics Applications Specialist – Office of Clinical Research (OCR)

- Health Scientist Administrator (Program Officer) – Center for Global Mental Health Research (CGMHR)

- Deputy Director – Office of Clinical Research (OCR)

- Social and Behavioral Sciences Administrator/Health Scientist Administrator (Program Officer) - Services Research and Clinical Epidemiology Branch (SRCEB)

- Technical Information Specialist - Electronic Communications Branch (ECB)

- Management Analyst - Executive Office (EO)

- Health Scientist Administrator (Program Officer) - Translational Genomics for Mental Health (TGMH)

- Health Scientist Administrator/Social and Behavioral Science Administrator (Program Officer) – Division of Services and Intervention Research (DSIR), Adult Psychosocial Interventions Research Program

- Health Scientist Administrator (Program Officer) - Genomics Research Branch

Intramural Research Program Opportunities

- Staff Scientist 1 – Section on Learning and Plasticity (SLP)

- Management Analyst (Emergency Management Contractor) - Intramural Administrative Oversight Branch (IAOB)

- Program Coordinator - Neurodevelopmental and Behavioral Phenotyping Service (NBPS)

- Staff Scientist 1 - The Office of the Scientific Director (OSD)

- Staff Clinician 1 (Research Psychiatrist) - Molecular Imaging Branch (MIB)

- Psychiatry Consultant Liaison/Staff Clinician 1 - The Office of the Clinical Director (OCD)

- Staff Scientist 1 - Developmental Neuroscience and Neurodevelopmental Disorders

- Staff Scientist 1 - Section on Cellular and Cognitive Neurodevelopment (SCCN)

Administrative Opportunities

- Deputy Chief Grants Management Officer - Grants Management Branch

- Scientific Review Officer - Extramural Review Branch

- Grants Management Specialist - Grants Management Branch

- Ethics Specialist - Ethics Branch

- Budget Analyst - Budget and Analytics Branch

- Computer Systems Analyst - Office of Science Policy, Planning, and Communications (OSPPC)

- Health Science Policy Analyst (OSPPC)

NIMH Detail Opportunities for Current Federal Employees

The following internal detail opportunities are available to current federal employees within NIH, the Department of Health and Human Services, and other federal organizations. Detail opportunities offer several benefits for existing federal employees, including professional development, networking opportunities, and career advancement.

- Management Analyst - Emergency Preparedness Specialist

- Management Analyst – Records Management – NIMH Executive Office

NIMH may be advertising other jobs on www.USAJOBS.gov , which lists job opportunities within the federal government. Users can create profiles, save resumes, and set up notifications for new job postings. Visit the USAJobs Help Center to get started.

Training and Career Development at NIMH

- Research Training and Career Development - Extramural

- Research Training and Career Development - Intramural

Jobs at the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)

- Employment Information from the Department of Health and Human Services

- Commissioned Corps of the U.S. Public Health Service - The uniformed service of the HHS

Jobs at the National Institutes of Health (NIH)

- Employment and Internship Opportunities at NIH

- NIH Office of Human Resources Management

Working for the Federal Government

- U.S. Office of Personnel Management - Everything you need to know about working for the Federal Government

- OPM Federal Pay Schedules

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Issues We Care About

- Digital Divide

- Affordability

- College Readiness

- Environmental Barriers

Measuring Impact

- WGU's Success Metrics

- Policy Priorities

- Annual Report

- WGU's Story

- Careers at WGU

- Impact Blog

10 Jobs You Can Get with a Health Sciences Degree

- See More Tags

If you’re considering a career in health, you might not know exactly where to start. Health sciences are a great option if you’d like to choose from a breadth of lucrative jobs that allow you to develop and apply skills in research, technology, leadership, and interpersonal communication to a meaningful career. Health sciences comprise a variety of disciplines, including hospital administration, healthcare management, and patient care.

Applying the science of health to real-world scenarios is vitally important to individual and societal well-being. Earning a health sciences degree could open doors to an in-demand career that improves the health of entire communities. Many health sciences degrees grant students a well-balanced understanding of healthcare, equipping them with a dynamic tool set for highly sought-after job roles in the industry.

This article discusses 10 jobs that a health sciences degree can prepare you for, including day-to-day responsibilities and skill qualifications for each.

Jobs You Can Pursue with a Health Sciences Degree

1. pharmaceutical sales representative.

Pharmaceutical sales representatives [hyperlink to CG when ready] offer medications and other medical supplies to healthcare facilities like hospitals and clinics. They research the prescription needs of doctors and healthcare professionals and then sell and promote products, often traveling to do so. These representatives may host product seminars for clients and often attend pharmaceutical trade shows and conferences.

Common skills for the role include the following:

- Communication and negotiation skills

- Presentation skills

- Assertiveness

- Understanding of pharmaceutical products for sale

- Knowledge of industry market trends

2. Patient Educator

Patient educators work alongside clinical staff to help patients understand treatment plans. They answer patient questions and discuss expectations before and after treatment is administered. To perform their jobs effectively, patient educators must also communicate regularly with doctors, nurses, and healthcare providers about how to best treat and care for patients.

Patient educators often develop skills in the following areas:

- Treatment plan knowledge

- Empathy and cultural awareness

- Understanding of medical technology

- Listening skills and attentiveness

- Teamwork and collaboration

3. Clinical Technologist

Many—if not all—healthcare centers employ clinical technologists to assist doctors and other staff with diagnostic procedures. These individuals use medical equipment and technology to help diagnose patients, test for disease or illness, collect biological samples, and more. Some clinical technologists might specialize in a field like phlebotomy or immunology, while others perform more general tasks like recording patient height, weight, or blood pressure.

For clinical technologists to succeed in their role, they should be skilled in operating and maintaining equipment and develop a detail-oriented mindset to yield accurate test results.

4. Clinical Director

A clinical director plays an indispensable role in supervising a healthcare facility’s overall operation. These leaders employ various management strategies to ensure that patients are properly cared for. Directing responsibilities often involve hiring and training staff, managing finances, and executing on big-picture goals to optimize business performance.

Clinical directors need to understand how clinical procedures and policies factor into their role, applying skills in organizational planning, leadership, clinical knowledge, and effective communication.

5. Clinical Manager

Clinical managers often carry out administrative tasks set by clinical directors. Their responsibilities may include onboarding new hires, developing training materials, organizing patient health records, or syncing with physicians, nurses, and other staff members as needed. Even though clinical managers might not be in daily contact with patients, their efforts help to keep clinics, hospitals, and other facilities functioning smoothly.

Clinical managers should be confident in a leadership role, exercising skills in communication, clinical computer software, and human resources.

6. Nursing Home Manager

Nursing homes and assisted living centers often require sensitive, empathetic care of residents. These patients can experience a wide variety of health challenges as they strive to live comfortably. Nursing home managers are responsible for fostering that comfort through planning budgets, maintaining effective patient treatment plans, organizing nursing staff schedules, and consistently training employees on best practices.

Nursing home managers can thrive in their career as long as they apply their skills in interpersonal communication, problem-solving, and leadership.

7. Resident Care Coordinator

Resident care coordinators —sometimes called “residential care facilitators”—focus on providing the best possible care to patients in assisted living facilities. Specific day-to-day tasks of a resident care coordinator include creating patient care policies, instructing nurses on administering treatment plans, and communicating with staff members to establish standardized performance goals.

Resident care coordinators should be equally skilled in business administration and healthcare management. Though they hold a high-level position, resident care coordinators should always have strong empathy toward their coworkers and their patients.

8. Patient Experience Manager

Whether they work in a hospital, doctor’s office, mental health clinic, or another similar environment, patient experience managers devote their time to educating and supporting patients. Depending on their patients’ health situations, patient experience managers may develop treatment plans, encourage patients during occupational or physical therapy, or act as liaisons between patients and care providers. Patient experience managers also keep up-to-date records on patient progress.

Common skills for patient experience managers include the following:

- Understanding of patient management software

- Knowledge of and compliance with healthcare regulations

9. Care Manager

Care managers assist patients through their treatment processes, therapy regimens, and post-procedure recovery. Most care managers collaborate closely with doctors, surgeons, therapists, and other similar professionals to learn how they can best support patients. Care managers are primarily concerned with their patients’ medical well-being, often helping them navigate the details of various medical services and resources.

For the best patient outcomes, care managers should develop skills in communication, patient education, and problem-solving.

10. Case Manager

Case managers perform similar tasks to care managers but tend to focus more on the administrative aspects of patient health. Most case management work involves helping patients find the best treatment plans, educating patients on health insurance policies, and referring patients to relevant social services as needed.

Patients benefit the most when their case managers are skilled in navigating complex healthcare systems and have a thorough understanding of healthcare providers.

Exploring the Boundless Opportunities in Health Sciences Careers

As you prepare for a career in health sciences, spend time reflecting on your individual interests and professional goals. Do you like working with technology? What about serving in a leadership role? Would you rather be part of a team or spend one-on-one time with patients?

Answering these types of questions can help you find an enriching, fulfilling job that plays to your strengths. A varied skill set in health sciences could even help you pivot to other similar jobs so you can find the role best suited to you.

Ready to earn a degree and open doorways to opportunity? Consider WGU. We offer more than a dozen online, accredited bachelor’s and master’s programs in healthcare, including health sciences, health and human services , and healthcare administration . In addition, WGU’s competency-based education model means that you advance through coursework as quickly as you show mastery of the material, so you can potentially graduate faster and save money.

Get started today.

Ready to Start Your Journey?

HEALTH & NURSING

Recommended Articles

Take a look at other articles from WGU. Our articles feature information on a wide variety of subjects, written with the help of subject matter experts and researchers who are well-versed in their industries. This allows us to provide articles with interesting, relevant, and accurate information.

What Is Health Science?

Collective Impact to Address the Nursing Shortage

Empowering Lifelong Learning: Digital Wallets and Collaborative Innovation

WGU Addresses Health Equity and Workforce Challenges

Diversifying Rio Grande Valley’s Nursing Pipeline

Rio Grande Valley Healthcare Workforce Challenges

The university.

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

For Students

- Student Portal

- Alumni Services

Most Visited Links

- Business Programs

- Bachelor's Degrees

- Student Experience

- Online Degrees

- Scholarships

- Financial Aid

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- Testimonials

- Student Communities

Research Related Agreements Associate

🔍 business affairs, redwood city, california, united states.

There are currently two openings for this position.

Stanford University is one of Silicon Valley's largest employers - and one of the most unique. Our mission is to educate future leaders and promote interdisciplinary, world-class research and teaching. This passion makes Stanford an intensely creative, rewarding, and challenging place to work. At Stanford University, not only are you part of an exceptional team that values innovation and education, but you also become part of a culture that brings out the best in you. Stanford is committed to fostering a workplace culture that promotes diversity, collaboration, and professional growth. Our culture offers career development programs, competitive pay that reflects market trends and benefits that increase financial stability and promote healthy, fulfilling lives.

Research—the creation of new knowledge—is key to Stanford’s educational mission. Stanford research has led to breakthrough remedies, devices, tools, and concepts, and hundreds of initiatives solely for the betterment of humanity. Among the inventions and discoveries that have resulted from Stanford research are MRI technology, DNA cloning, the Pill, heart transplantation, and digital music.

Stanford is investing unprecedented resources in the Office of Research Administration (ORA) due to a growth in the research enterprise that continues to surpass 12% yearly. This position is one of many new staff positions that have been created to enhance our ability to provide high-quality, personalized services and expertise to support our faculty and campus community. ORA submits over 5,000 new proposals, reviews and negotiates over 7000 agreements, and manages more than 7,500 active sponsored projects annually with a total research budget approaching $2 billion.

This position may be considered for domestic (US) remote work.

JOB PURPOSE Our team is growing! Stanford’s Office of Research Administration (ORA) is expanding our team of Research Related Agreements Associates (RRAA) focused on non-sponsored agreements that support research. The cross-functional RRAA will have a flexible assignment based on areas of need. RRAA responsibilities may include reviewing requests for data use and other research related agreements, gathering project information from researchers, coordination of compliance documentation, preparation of select agreements for Contract Officer approval. The RRAA may also prepare negotiate, and oversee select agreements on behalf of Stanford University. In addition, the RRAA will play a key role in supporting ORA initiatives and special projects. As part of a service-driven organization, ORA is looking for dynamic, flexible, and motivated Associates who approach learning and problem solving with enthusiasm, who are organized and focused to manage a significant workload, who adapt easily to changing situations and views new opportunities as creative challenges.

CORE DUTIES*:

- Achieve and maintain delegated signature authority on behalf of Stanford University.

- Conduct comprehensive analysis and negotiation of select agreements. Ensure contract terms are consistent with University policy.

- Coordinate escalation of issues in contract terms to appropriate university stakeholders (e.g., Risk Management, Office of General Counsel), as needed.

- Resolve problems arising in the course of the project; consult with department administrators, principal investigators and staff.

- Partner with Contract and Grant Officers to deliver excellent client services to Stanford faculty and research administration community.

- Support key initiatives and special projects at the organizational level.

- * - Other duties may also be assigned

MINIMUM REQUIREMENTS

Education & Experience:

Bachelor's degree and one year of relevant experience, or combination of education and relevant experience.

Knowledge, Skills and Abilities:

- Demonstrated understanding of university research environment and policies.

- Experience with university research administration or related experience preferred.

- Working knowledge of and experience applying regulatory requirements as applied to research and research administration.

- Demonstrated ability to: o Draft, negotiate and execute select agreements. o Communicate knowledge and ideas both verbally and in writing with clarity and effectiveness to internal and external audiences, client groups and all levels of management. o Make good decisions based on critical and analytical thinking, experience and judgement. o Deliver high quality service and work products that can be relied upon by clients and colleagues to meet business requirements. o Drive change and continuous improvement through individual contributions. o Function effectively and independently in a fast-paced environment subject to external pressure and frequent interruptions. o Collaborate and work effectively in a distributed team environment.

- Work well with colleagues and clients.

- Demonstrates curiosity and is comfortable with uncertainty and ambiguity.

- Strong service orientation, demonstrated ability to work effectively in a fast-paced, action-oriented, customer-focused service environment.

- Strong organizational skills and the ability to prioritize a variety of tasks and demands.

- Strong computer skills, including Microsoft Office Suite and ability to learn applicable university and departmental systems.

Certifications and Licenses:

PHYSICAL REQUIREMENTS:

- Frequently sitting, grasping lightly, use fine manipulation and a computer (keyboard, mouse, monitor).

- Occasionally use a telephone, rarely stand/walk, twist, bend, stoop, squat, write by hand, sort, and file paperwork or parts.

- Rarely lift, carry push, and pull objects that weigh up to 10 pounds.

WORKING CONDITIONS:

- May have occasional extended or weekend work hours during peak business cycles.

WORK STANDARDS:

- Interpersonal Skills: Demonstrates the ability to work well with Stanford colleagues and clients and with external organizations.

- Promote Culture of Safety: Demonstrates commitment to personal responsibility and value for safety; communicates safety concerns; uses and promotes safe behaviors based on training and lessons learned.

- Subject to and expected to comply with all applicable University policies and procedures, including but not limited to the personnel policies and other policies found in the University's Administrative Guide, http://adminguide.stanford.edu .

This role is open to candidates anywhere in the United States. Stanford University has five Regional Pay Structures . The compensation for this position will be based on the location of the successful candidate.

The expected pay range for this position is $57,000 to $87,000 per annum.

Stanford University provides pay ranges representing its good faith estimate of what the university reasonably expects to pay for a position. The pay offered to a selected candidate will be determined based on factors such as (but not limited to) the scope and responsibilities of the position, the qualifications of the selected candidate, departmental budget availability, internal equity, geographic location, and external market pay for comparable jobs.

At Stanford University, base pay represents only one aspect of the comprehensive rewards package. The Cardinal at Work website ( https://cardinalatwork.stanford.edu/benefits-rewards ) provides detailed information on Stanford’s extensive range of benefits and rewards offered to employees. Specifics about the rewards package for this position may be discussed during the hiring process.

Why Stanford is for You Imagine a world without search engines or social platforms. Consider lives saved through first-ever organ transplants and research to cure illnesses. Stanford University has revolutionized the way we live and enrich the world. Supporting this mission is our diverse and dedicated 17,000 staff. We seek talent driven to impact the future of our legacy. Our culture and unique perks empower you with:

- Freedom to grow . We offer career development programs, tuition reimbursement, or course auditing. Join a TedTalk, film screening, or listen to a renowned author or global leader speak.

- A caring culture . We provide superb retirement plans, generous time-off, and family care resources.

- A healthier you . Climb our rock wall or choose from hundreds of health or fitness classes at our world-class exercise facilities. We also provide excellent health care benefits.

- Discovery and fun . Stroll through historic sculptures, trails, and museums.

- Enviable resources . Enjoy free commuter programs, ridesharing incentives, discounts and more

The job duties listed are typical examples of work performed by positions in this job classification and are not designed to contain or be interpreted as a comprehensive inventory of all duties, tasks, and responsibilities. Specific duties and responsibilities may vary depending on department or program needs without changing the general nature and scope of the job or level of responsibility. Employees may also perform other duties as assigned. Consistent with its obligations under the law, the University will provide reasonable accommodations to applicants and employees with disabilities. Applicants requiring a reasonable accommodation for any part of the application or hiring process should contact Stanford University Human Resources at [email protected] . For all other inquiries, please submit a contact form . Stanford is an equal employment opportunity and affirmative action employer. All qualified applicants will receive consideration for employment without regard to race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, national origin, disability, protected veteran status, or any other characteristic protected by law.

- Schedule: Full-time

- Job Code: 4571

- Employee Status: Regular

- Requisition ID: 102835

- Work Arrangement : Hybrid Eligible, Remote Eligible, On Site

My Submissions

Track your opportunities.

Similar Listings

Business Affairs, Redwood City, California, United States

📁 Compliance Legal

Post Date: Apr 03, 2024

Post Date: Apr 02, 2024

Post Date: Mar 06, 2024

Global Impact We believe in having a global impact

Climate and sustainability.

Stanford's deep commitment to sustainability practices has earned us a Platinum rating and inspired a new school aimed at tackling climate change.

Medical Innovations

Stanford's Innovative Medicines Accelerator is currently focused entirely on helping faculty generate and test new medicines that can slow the spread of COVID-19.

From Google and PayPal to Netflix and Snapchat, Stanford has housed some of the most celebrated innovations in Silicon Valley.

Advancing Education

Through rigorous research, model training programs and partnerships with educators worldwide, Stanford is pursuing equitable, accessible and effective learning for all.

Working Here We believe you matter as much as the work

I love that Stanford is supportive of learning, and as an education institution, that pursuit of knowledge extends to staff members through professional development, wellness, financial planning and staff affinity groups.

School of Engineering

I get to apply my real-world experiences in a setting that welcomes diversity in thinking and offers support in applying new methods. In my short time at Stanford, I've been able to streamline processes that provide better and faster information to our students.

Phillip Cheng

Office of the Vice Provost for Student Affairs

Besides its contributions to science, health, and medicine, Stanford is also the home of pioneers across disciplines. Joining Stanford has been a great way to contribute to our society by supporting emerging leaders.

Denisha Clark

School of Medicine

I like working in a place where ideas matter. Working at Stanford means being part of a vibrant, international culture in addition to getting to do meaningful work.

Office of the President and Provost

Getting Started We believe that you can love your job

Join Stanford in shaping a better tomorrow for your community, humanity and the planet we call home.

- 4.2 Review Ratings

- 81% Recommend to a Friend

View All Jobs

- See us on facebook

- See us on twitter

- See us on youtube

- See us on linkedin

- See us on instagram

Stanford Medicine study flags unexpected cells in lung as suspected source of severe COVID

A previously overlooked type of immune cell allows SARS-CoV-2 to proliferate, Stanford Medicine scientists have found. The discovery has important implications for preventing severe COVID-19.

April 10, 2024 - By Bruce Goldman

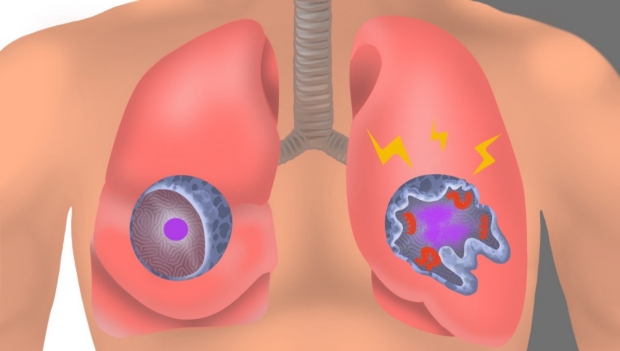

In an uninfected interstitial macrophage, the nucleus (purple) and outer cell membrane (blue) are intact. In an infected interstitial macrophage, the nucleus is shattered, copious newly made viral components (red) clump together, and the cell broadcasts inflammatory and scar-tissue-inducing chemical signals (yellow). Emily Moskal

The lung-cell type that’s most susceptible to infection by SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is not the one previously assumed to be most vulnerable. What’s more, the virus enters this susceptible cell via an unexpected route. The medical consequences may be significant.

Stanford Medicine investigators have implicated a type of immune cell known as an interstitial macrophage in the critical transition from a merely bothersome COVID-19 case to a potentially deadly one. Interstitial macrophages are situated deep in the lungs, ordinarily protecting that precious organby, among other things, engorging viruses, bacteria, fungi and dust particles that make their way down our airways. But it’s these very cells, the researchers have shown in a study published online April 10 in the Journal of Experimental Medicine , that of all known types of cells composing lung tissue are most susceptible to infection by SARS-CoV-2.

SARS-CoV-2-infected interstitial macrophages, the scientists have learned, morph into virus producersand squirt out inflammatory and scar-tissue-inducing chemical signals, potentially paving the road to pneumonia and damaging the lungs to the point where the virus, along with those potent secreted substances, can break out of the lungs and wreak havoc throughout the body.

The surprising findings point to new approaches in preventing a SARS-CoV-2 infection from becoming a life-threatening disease. Indeed, they may explain why monoclonal antibodies meant to combat severe COVID didn’t work well, if at all — and when they did work, it was only when they were administered early in the course of infection, when the virus was infecting cells in the upper airways leading to the lungs but hadn’t yet ensconced itself in lung tissue.

The virus surprises

“We’ve overturned a number of false assumptions about how the virus actually replicates in the human lung,” said Catherine Blish , MD, PhD, a professor of infectious diseases and of microbiology and immunology and the George E. and Lucy Becker Professor in Medicine and associate dean for basic and translational research.

Blish is the co-senior author of the study, along with Mark Krasnow , MD, PhD, the Paul and Mildred Berg Professor of biochemistry and the Executive Director of the Vera Moulton Wall Center for pulmonary vascular disease.

“The critical step, we think, is when the virus infects interstitial macrophages, triggering a massive inflammatory reaction that can flood the lungs and spread infection and inflammation to other organs,” Krasnow said. Blocking that step, he said, could prove to be a major therapeutic advance. But there’s a plot twist: The virus has an unusual way of getting inside these cells — a route drug developers have not yet learned how to block effectively — necessitating a new focus on that alternative mechanism, he added.

Catherine Blish

In a paper published in Nature in early 2020, Krasnow and his colleagues including then-graduate student Kyle Travaglini, PhD — who is also one of the new study’s co-lead authors along with MD-PhD student Timothy Wu — described a technique they’d worked out for isolating fresh human lungs; dissociating the cells from one another; and characterizing them, one by one, on the basis of which genes within each cell were active and how much so. Using that technique, the Krasnow lab and collaborators were able to discern more than 50 distinct cell types, assembling an atlas of healthy lung cells.

“We’d just compiled this atlas when the COVID-19 pandemic hit,” Krasnow said. Soon afterward, he learned that Blish and Arjun Rustagi , MD, PhD, instructor of infectious diseases and another lead co-author of the study, were building an ultra-safe facility where they could safely grow SARS-CoV-2 and infect cells with it.

A collaboration ensued. Krasnow and Blish and their associates obtained fresh healthy lung tissue excised from seven surgical patients and five deceased lung donors whose lungs were virus-free but for one reason or another not used in transplants. After infecting the lung tissue with SARS-CoV-2 and waiting one to three days for the infection to spread, they separated and typed the cells to generate an infected-lung-cell atlas, analogous to the one Krasnow’s team had created with healthy lung cells. They saw most of the cell types that Krasnow’s team had identified in healthy lung tissue.

Now the scientists could compare pristine versus SARS-CoV-2-infected lungs cells of the same cell type and see how they differed: They wanted to know which cells the virus infected, how easily SARS-CoV-2 replicated in infected cells, and which genes the infected cells cranked up or dialed down compared with their healthy counterparts’ activity levels. They were able to do this for each of the dozens of different cell types they’d identified in both healthy and infected lungs.

“It was a straightforward experiment, and the questions we were asking were obvious,” Krasnow said. “It was the answers we weren’t prepared for.”

It’s been assumed that the cells in the lungs that are most vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2 infection are those known as alveolar type 2 cells. That’s because the surfaces of these cells, along with those of numerous other cell types in the heart, gut and other organs, sport many copies of a molecule known as ACE2. SARS-CoV-2 has been shown to be able to grab onto ACE2 and manipulate it in a way that allows the virus to maneuver its way into cells.

Alveolar type 2 cells are somewhat vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2, the scientists found. But the cell types that were by far the most frequently infected turned out to be two varieties of a cell type called a macrophage.

Virus factories

The word “macrophage” comes from two Greek terms meaning, roughly, “big eater.” This name is not unearned. The air we inhale carries not only oxygen but, unfortunately, tiny airborne dirt particles, fungal spores, bacteria and viruses. A macrophage earns its keep by, among other things, gobbling up these foreign bodies.

Mark Krasnow

The airways leading to our lungs culminate in myriad alveoli, minuscule one-cell-thick air sacs, whichare abutted by abundant capillaries. This interface, called the interstitium, is where oxygen in the air we breathe enters the bloodstream and is then distributed to the rest of the body by the circulatory system.

The two kinds of SARS-CoV-2-susceptible lung-associated macrophages are positioned in two different places. So-called alveolar macrophages hang out in the air spaces within the alveoli. Once infected, these cells smolder, producing and dribbling out some viral progeny at a casual pace but more or less keeping a stiff upper lip and maintaining their normal function. This behavior may allow them to feed SARS-CoV-2’s progression by incubating and generating a steady supply of new viral particles that escape by stealth and penetrate the layer of cells enclosing the alveoli.

Interstitial macrophages, the other cell type revealed to be easily and profoundly infected by SARS-CoV-2, patrol the far side of the alveoli, where the rubber of oxygen meets the road of red blood cells. If an invading viral particle or other microbe manages to evade alveolar macrophages’ vigilance, infect and punch through the layer of cells enclosing the alveoli, jeopardizing not only the lungs but the rest of the body, interstitial macrophages are ready to jump in and protect the neighborhood.

At least, usually. But when an interstitial macrophage meets SARS-CoV-2, it’s a different story. Rather than get eaten by the omnivorous immune cell, the virus infects it.

And an infected interstitial macrophage doesn’t just smolder; it catches on fire. All hell breaks loose as the virus literally seizes the controls and takes over, hijacking a cell’s protein- and nucleic-acid-making machinery. In the course of producing massive numbers of copies of itself, SARS-CoV-2 destroys the boundaries separating the cell nucleus from the rest of the cell like a spatula shattering and scattering the yolk of a raw egg. The viral progeny exit the spent macrophage and move on to infect other cells.

But that’s not all. In contrast to alveolar macrophages, infected interstitial macrophages pump out substances that signal other immune cells elsewhere in the body to head for the lungs. In a patient, Krasnow suggested, this would trigger an inflammatory influx of such cells. As the lungs fill with cells and fluid that comes with them, oxygen exchange becomes impossible. The barrier maintaining alveolar integrity grows progressively damaged. Leakage of infected fluids from damaged alveoli propels viral progeny into the bloodstream, blasting the infection and inflammation to distant organs.

Yet other substances released by SARS-CoV-2-infected interstitial macrophages stimulate the production of fibrous material in connective tissue, resulting in scarring of the lungs. In a living patient, the replacement of oxygen-permeable cells with scar tissue would further render the lungs incapable of executing oxygen exchange.

“We can’t say that a lung cell sitting in a dish is going to get COVID,” Blish said. “But we suspect this may be the point where, in an actual patient, the infection transitions from manageable to severe.”

Another point of entry

Compounding this unexpected finding is the discovery that SARS-CoV-2 uses a different route to infect interstitial macrophages than the one it uses to infect the other types.

Unlike alveolar type 2 cells and alveolar macrophages, to which the virus gains access by clinging to ACE2 on their surfaces, SARS-CoV-2 breaks into interstitial macrophages using a different receptor these cells display. In the study, blocking SARS-CoV-2’s binding to ACE2 protected the former cells but failed to dent the latter cells’ susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

“SARS-CoV-2 was not using ACE2 to get into interstitial macrophages,” Krasnow said. “It enters via another receptor called CD209.”

That would seem to explain why monoclonal antibodies developed specifically to block SARS-CoV-2/ACE2 interaction failed to mitigate or prevent severe COVID-19 cases.

It’s time to find a whole new set of drugs that can impede SARS-CoV-2/CD209 binding. Now, Krasnow said.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (grants K08AI163369, T32AI007502 and T32DK007217), the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Chan Zuckerberg Biohub, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, Stanford Chem-H, the Stanford Innovative Medicine Accelerator, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

About Stanford Medicine

Stanford Medicine is an integrated academic health system comprising the Stanford School of Medicine and adult and pediatric health care delivery systems. Together, they harness the full potential of biomedicine through collaborative research, education and clinical care for patients. For more information, please visit med.stanford.edu .

Artificial intelligence

Exploring ways AI is applied to health care

Irregular job schedules may be linked to poor sleep and faltering health by age 50

With the rise of the US service economy and technological progress, researchers are taking a closer look at the impact of erratic work hours on the health of employees—nurses who make rounds into the predawn hours, burger flippers with irregular shifts, and software engineers who stay “in the zone” long past midnight.

There’s new evidence that schedule chaos, an increasing phenomenon, can take a serious toll. Those with nonstandard employment patterns starting at 22 are more likely to report sleep issues, poor health, and depressive symptoms by age 50, according to a new study by Wen-Jui Han, an NYU Silver School of Social Work professor with training in sociology, economics, developmental psychology, and public policy. Her recent research has explored the impact of parents’ work schedules on their own well-being and that of their children.

The new study on erratic schedules, published in the journal PLOS ONE on April 3, looks at how one’s social position “plays a significant role in these adverse health consequences” from working jobs with shifts outside the more traditional 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. The findings show that individuals occupying a lower social position, such as those who did not go to college or whose employment status may be precarious, are more likely than some others to suffer from inadequate or poor sleep.

“In reality, our work patterns are more volatile and diverse than we can imagine.”

Here are some additional takeaways from the study:

● Han’s research is the first scholarship to use longitudinal studies and a life-course perspective (with sequence analysis) to examine how work schedule patterns, whether consistently or periodically irregular starting in our early 20s, might be associated with our sleep and health as we approach mid-life.

● Her analysis relies on the National Longitudinal Study of Youth, a nationally representative sample of about 7,000 people in the US conducted over three decades. The data collection began in 1979, asking participants about their sleep and mental and physical health over time along with their evolving work schedules.

● Nonstandard work schedules, very prevalent across the US since at least the 1980s, are increasingly becoming a global phenomenon.

● The significantly poorer sleep and health outcomes observed through the longitudinal analysis are concentrated among people with vulnerable social positions, such as women, racial minorities, and those without a college degree.

● As expected, socioeconomic factors such as wages, marital status, education, and poverty are significantly associated with problematic sleep and health. But there are exceptions. Black workers, both women and men, reported a lower likelihood of having depressive symptoms than their White counterparts, for example. White women, particularly those with less than a high school education, reported the highest likelihood of depressive symptoms.

“In reality, our work patterns are more volatile and diverse than we can imagine,” says Han, whose research revealed that shifting schedules were relatively common among workers between ages 22 and 49, whether they started out working standard hours and transitioned to something more variable, or worked mainly 9-to-5 with some night shifts mixed in. “About three-quarters of the work patterns we observed did not strictly conform to working stably during daytime hours throughout our working years. This has repercussions.”

People with work patterns involving any degree of volatility, she explains, were more likely to have fewer hours of sleep per day, lower sleep quality, lower physical and mental functions, and a higher likelihood of reporting poor health and depressive symptoms at 50 years old than those with stable standard work schedules. Those adverse health consequences from nonstandard work schedule patterns—whether taking care of one’s own children at home or working a job for pay—are “alarming,” the study concludes, especially in light of the scholarship revealing that an adequate amount of quality sleep is important for heading off anxiety and depression, hypertension, obesity, or even stroke.

And “the picture becomes grimmer if we further disentangle these links by social position,” Han writes.

Press Contact

- Open access

- Published: 10 April 2024

Stress, interpersonal and inter-role conflicts, and psychological health conditions among nurses: vicious and virtuous circles within and beyond the wards

- Federica Vallone 1 &

- Maria Clelia Zurlo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0045-2800 2

BMC Psychology volume 12 , Article number: 197 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

The increasing costs of nurses’ occupational-stress, conflicts, and violence within healthcare services have raised international interest. Yet, research/interventions should consider that perceived stress and conflicts– but also potential resources– within the wards can crossover the healthcare settings, impacting nurses’ private lives and viceversa , potentially creating vicious circles exacerbating stress, conflicts/violence or, conversely, virtuous circles of psychological/relational wellbeing. Based on the Demands-Resources-and-Individual-Effects (DRIVE) Nurses Model , and responding to the need to go in-depth into this complex dynamic, this study aims to explore potential vicious circles featured by the negative effects of the interplay (main/mediating effects) between perceived stressors in nursing linked to interpersonal conflicts (Conflicts-with-Physicians, Peers, Supervisors, Patients/their families), work-family inter-role conflicts (Work-Family/Family-Work-Conflicts), and work-related stress (Effort-Reward-Imbalance) on nurses’ psychological/relational health (Anxiety, Depression, Somatization, Interpersonal-Sensitivity, Hostility). The potential moderating role of work-resources (Job-Control, Social-Support, Job-Satisfaction) in breaking vicious circles/promoting virtuous circles was also explored.

The STROBE Checklist was used to report this cross-sectional multi-centre study. Overall, 265 nurses completed self-report questionnaires. Main/mediating/moderating hypotheses were tested by using Correlational-Analyses and Hayes-PROCESS-tool.

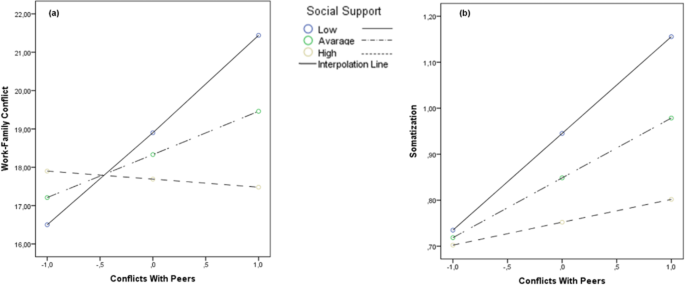

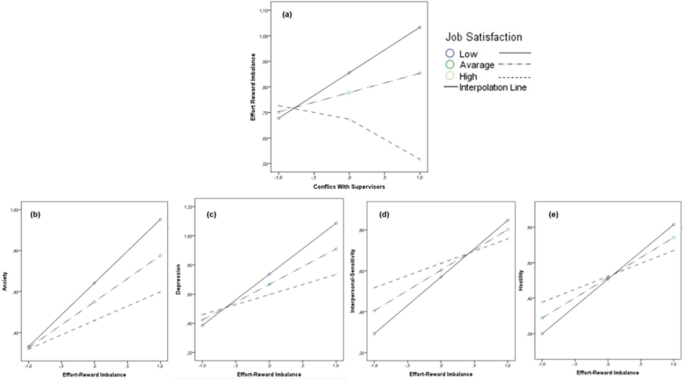

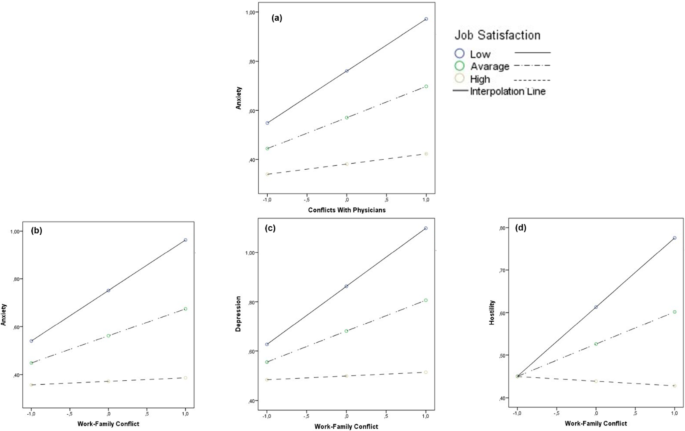

Data confirmed the hypothesized detrimental vicious circles (main/mediating effects), impairing nurses’ psychological health conditions at individual level (Anxiety, Depression, Somatization), but also at relational level (Hostility and Interpersonal-Sensitivity). The moderating role of all work resources was fully supported.

Findings could be used to implement interventions/practices to effectively prevent the maintenance/exacerbation of vicious circles and promote psychological/relational wellbeing in healthcare settings and beyond.

Peer Review reports

Promoting occupational health and safety in the healthcare sector is a serious concern globally, and it is still at the heart of the international debate [ 1 , 2 ]. Specifically, in recent decades, growing concern and attention have been given to nursing professionals [ 3 , 4 ], who are required to achieve gold standard with fewer resources (e.g., staff shortage), to perform more of the daily care activities in direct contact with patients/their relatives, as well as to coordinate– to a greater extent– with colleagues (other nurses and physicians). This results in higher risk of perceiving imbalance between expended efforts and received rewards/recognitions for their work [ 5 , 6 ] and feeling more emotionally exhausted than other healthcare professionals [ 7 , 8 ].

Recently, responding to the need to provide a tailored tool to assess work-related stress and develop effective interventions promoting occupational health among nursing professionals, research has provided a statistically valid multidimensional transactional model [ 9 ]. Based on the Demands-Resources and Individual Effects Model ( DRIVE Model ) [ 10 , 11 , 12 ], this model, namely the DRIVE-Nurses Model , allows to simultaneously account for the impact of the complex interplay (main, mediating, moderating effects) of a wide range of individual, situational, and relational dimensions to be adopted in the public healthcare services for a broad assessment of risks and protective factors influencing nurses’ psychological and physical health conditions [ 9 ]. Specifically, the model includes the following dimensions: Work Characteristics – integrating Effort-Reward Imbalance Model dimensions [ 13 ] and Job Demands-Control-Support Model dimensions [ 14 ]– along with Individual Characteristics (i.e., socio-demographics, coping strategies, personality factors), and Work–Family Interface Dimensions (i.e., Work–family inter-role conflict; job/life satisfaction).

Noticeably, the abovementioned model fully embodies the more renowned perspective for achieving a greater and more comprehensive understanding of workers’ life, namely the Work-Family Spillover perspective [ 15 , 16 ]. The latter approach reconceptualises the complexity of the workers’ lives, extending to the understanding of individual’s life. It suggests that research/interventions need to take into account that the positive and the negative feelings/experiences in one domain (workplace or family/private) are able to crossover their boundaries, having a positive (enrichment) or negative (conflict) impact also on the other one domain.

In line with this, recent research applications of the DRIVE-Nurses Model specifically targeted the examination of perceived inter-role conflict among nurses [ 17 ]. In particular, evidence was provided for the detrimental impact of perceived work-family conflict among both male and female nurses, yet it was also supported the moderating role of work-resources, such as perceived job control, social support, and job satisfaction. These resources were indeed found able to significantly buffer/counteract the negative effects of perceived inter-role conflict among nurses.

Nowadays, besides the meaningful of focussing on perceived conflict between work and private life, and in line with the spillover perspective , research highlighted another key issue that needs to be carefully targeted globally, namely perceived conflict and violence within the healthcare settings [ 18 , 19 , 20 ]. Indeed, about 63% of healthcare workers worldwide reported they have experienced any form of violence and conflict within the workplace [ 2 , 21 ], including verbal abuses, such as threatening/bullying/offending/excluding behaviours (e.g., shouting, insults, overload in work shifts), and/or physical abuses (e.g., assaults/aggressions, attempted assaults/aggressions).

This already high rate should however be evaluated with caution, since episodes of violence– mainly linked to exacerbation of conflicts and non-physical abuses– are still often not reported, underreported and/or partially documented by nurses, mainly due to the stigma of victimization (i.e., shame, fear of judgement, blame/non-supportive environment), fear of consequences for their selves/fear of lack of consequences for the perpetrators, as well as due to the lack of knowledge about the reporting process/systems [ 22 , 23 ]. Furthermore, there is still lack of knowledge and clarity on what constitute a violence, thus verbal abuses and exacerbation of interpersonal conflicts are often not reported since they are underestimated and believed as not enough serious to seek for support [ 24 , 25 , 26 ].

Notwithstanding, in recent decades, research targeted this key topic, underlining the need to identify both the potentially different actors/critical relations involved onto conflictual/violent dynamics (i.e., stressors linked to interpersonal conflict) and the consequences of such issue [ 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 ]. Indeed, several studies have underlined not only nurses’ risk of reporting decreasing performance, lower quality of care, and higher turnover intention [ 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ], but also the severe risk for nurses’ psychological health conditions, in terms of anxiety, depression [ 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 ], and somatization [ 39 , 40 ]. Some studies have also underlined the impact of perceived workplace violence in terms of increasing frustration, disruptions in the relationships with co-workers [ 41 ], inappropriate professional communication [ 4 ], and growing hostility [ 32 , 34 , 42 ], with even some evidence suggesting the risk of a spiral effect of violence and interpersonal conflict [ 43 ].

Nonetheless, despite the well-demonstrated worrisome high prevalence of perceived occupational stress, violence/conflicts towards and between nurses, and the growing implementation of programmes targeting this issue, there is still lack of research focusing on this phenomenon by adopting a more comprehensive and dynamic approach. This, however, could allow gaining further insight into the complex relationship between perceived stress, conflicts and psychological/relational wellbeing experienced within and outside the wards. Indeed, the interplay between work and private lives is rather complex and tangled [ 44 ]. Accordingly, perceived sources of stress and conflicts– along with the potential resources– within the wards are able to crossover the healthcare settings, impacting nurses’ personal lives and viceversa , thus potentially creating vicious circles exacerbating stress, conflicts, imbalances, psychological suffering, anger and hostility or, conversely, sustaining virtuous circles of psychological and relational wellbeing.

Therefore, there is a need to provide updated evidence which based on exploring in-depth more complex dynamics featuring the reciprocity of the experiences within the wards and outside the wards. Additionally, there is a need to investigate the impact of workplace violence and conflicts by assessing the risk of reporting a wider range of potential outcomes, such as interpersonal-sensitivity and hostility, which are of particular interest when examining interpersonal relationships. Unveiling vicious and virtuous circles could indeed effectively inform the development of tailored research and evidence-based interventions.

The present study proposed a research application of the DRIVE-Nurses Model [ 9 ] to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the issue of stress, violence and conflictual dynamics in nursing. In the present paper, we will analyse the issue of workplace violence and conflict by assessing perceived stressors linked to interpersonal conflict in nursing [ 45 ]– namely perceived stress linked to problems/conflicts with physicians, with peers, with supervisors as well as with patients and their families– rather than by assessing the frequency of episodes of violence/conflicts occurred. This choice was made given the phenomena of underreported/underestimated events of violence and conflicts– mainly non-physical ones [ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]. It was indeed hoped that focusing on perceived problems and conflicts in the interpersonal life of nurses– rather than assessing events of violence within these relationships– would elicit a more open reflection on this hidden phenomenon, giving further research attention to the more subtle forms of experiences of violence in nursing.

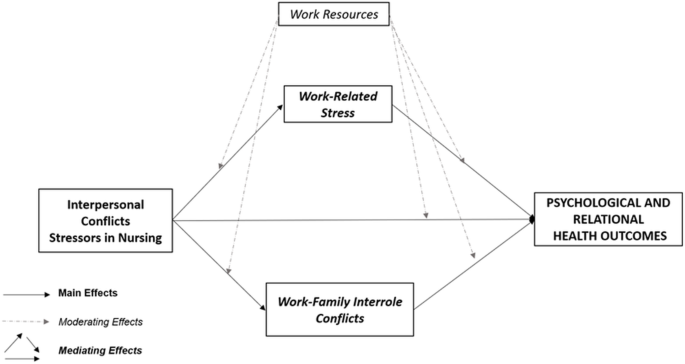

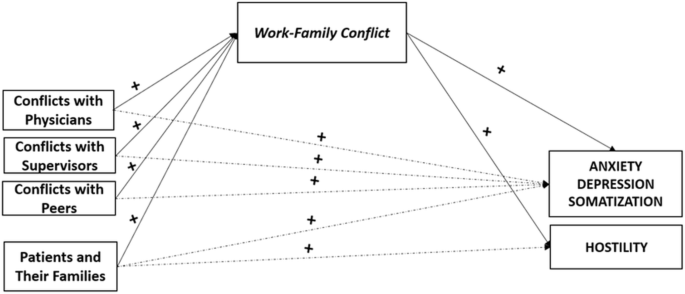

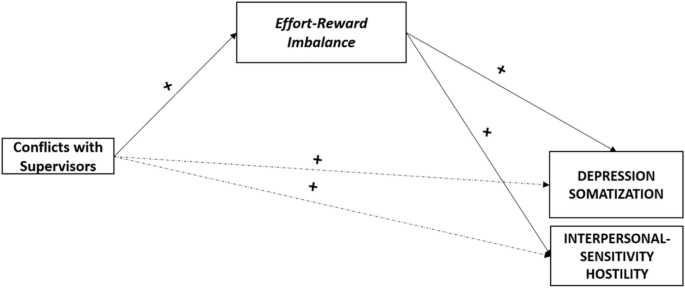

Specifically, the study has a twofold objective in mind: (1) To explore potential vicious circles featured by the negative effects of the interplay (main/mediating effects) between perceived stressors in nursing linked to interpersonal conflicts (Conflicts-with-Physicians, Peers, Supervisors, Patients/their families), work-family inter-role conflicts (Work-Family/Family-Work Conflicts), and work-related stress dimensions (Effort-Reward-Imbalance) on nurses’ psychological and relational health conditions (Anxiety, Depression, Somatization, Interpersonal-Sensitivity, Hostility); (2) To test the potential moderating role of work resources (Job-Control, Social-Support, Job-Satisfaction) in breaking vicious circles/promoting virtuous circles. Accordingly, detailed hypotheses have been developed and tested (Fig. 1 ).

Conceptual Framework: Main, Mediating and Moderating Hypotheses

Firstly, considering the evidence suggesting the detrimental impact of workplace violence and conflicts [ 4 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 39 , 41 , 46 , 47 ], of work-family inter-role conflict [ 4 , 17 ], as well as of work-related stress [ 9 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 ] on nurses’ psychological and relational health conditions, the following hypothesis was proposed:

Hypothesis one (H1)– Main Effects . Perceived stressors in nursing linked to interpersonal conflicts (H1a), work-family inter-role conflicts (H1b), and work-related stress (H1c) dimensions will be positively related to nurses’ psychological and relational health conditions.

Secondly, considering the evidence suggesting the potential of perceived workplace conflict/violence in exacerbating perceived levels of work-family inter-role conflicts [ 4 , 53 ], and work-related stress [ 33 , 54 , 55 , 56 ], as well as the potential of vicious circles of stress and conflicts exacerbating psychological and relational suffering [ 43 ], the following hypothesis was tested.

Hypothesis two (H2)– Mediating Effects . Perceived stressors in nursing linked to interpersonal conflicts will be positively related to work-family inter-role conflicts (H2a) and to work-related stress (H2b) dimensions. In addition, work-family inter-role conflicts (H2c) and work-related stress (H2d) dimensions will play as mediators in the associations between stressors in nursing linked to interpersonal conflicts and nurses’ psychological and relational health conditions.

Finally, considering the well-demonstrated protective role of work-resources [ 9 , 17 ] and, in particular, the moderating role of perceived control [ 57 , 58 ], organizational support [ 59 , 60 , 61 ], and job satisfaction [ 62 , 63 ], the following hypothesis was tested:

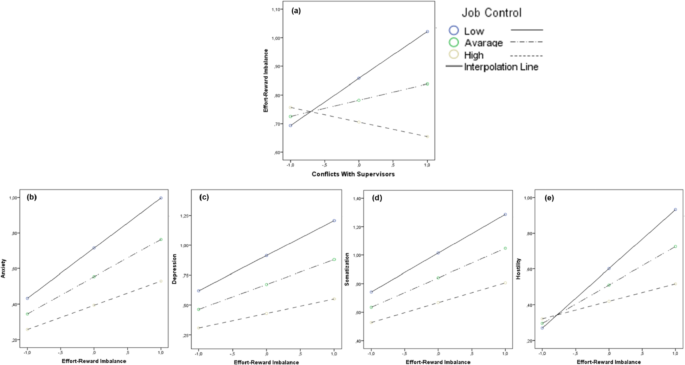

Hypothesis three (H3)– Moderating Effects . Perceived Work-Resources, namely Job Control (H3a), Social Support (H3b), and Job Satisfaction (H3c) will significantly moderate/buffer the relationships between perceived stressors in nursing linked to interpersonal conflicts and, respectively, work-family inter-role conflicts, work-related stress, and psychological and relational health conditions. In addition, Work-Resources will also significantly moderate/buffer the relationships between, respectively, work-family inter-role conflicts and work-related stress with psychological and relational health conditions.

Materials and methods

The present cross-sectional multi-centre study was carried out in a sample of 265 nurses, recruited from Italian Hospitals of the Public Health Service between January and August 2023. The STROBE Checklist was used to report this study. Chairpersons and– where available– Nursing Managers were contacted to ask for the permission for administering a questionnaire to the nursing staff (in-presence administration, with a trained psychologist always available to respond to any doubt/queries). Afterwards, nurses were directly contacted and given all the information about the research objective as well as about the confidentiality of the data collection procedure. To be included, participants need to be nurses working in Public Health Service (i.e., high-specialized hospital, academic hospital, general hospital). Those nurses working in private settings were not covered in the present study. The study was performed in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards, and it was approved by the Ethics Committee of Psychological Research of University of Naples Federico II. A total of 265 out of 300 nurses agreed to participate in the study, provided the informed consent, and completed the questionnaire in all its section (Response Rate = 88.3%). There were no missing data. Overall, the sample is representative of the diverse nursing workforce for sex and age. Indeed, 39.6% ( n = 105) were men, 60.7% ( n = 160) were women, and the ages ranged from 21 to 65 years ( M = 44.3, SD = 10.0).

The questionnaire included a section for registering nurses’ background information, along with validated measures for the assessment of perceived stressors in nursing linked to interpersonal conflicts, work-family inter-role conflicts, work-related stress, work-resources, and psychological and relational health conditions.

Stressors in nursing-interpersonal conflicts

Perceived stress linked to interpersonal conflicts was assessed by using the Expanded Nursing Stress Scale (ENSS) [ 45 ], which consists of 57 items on a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = “never stressful” to 4 = “extremely stressful”, with 0 = “does not apply”) and divided into nine subscales, namely Death and Dying, Inadequate Emotional Preparation, Discrimination, Uncertainty Concerning Treatments, Workload, Conflicts with Physicians, Conflicts with Peers, Conflicts with Supervisors, Patients and their Families. In line with our research objectives, four subscales out of nine of the ENSS were used, namely Conflicts with Physicians (5 items, e.g., “Criticism by a physician”); Conflicts with Peers (6 items; e.g., “Difficulty with another nurse in immediate work setting”); Conflicts with Supervisors (7 items, e.g., “Criticisms by a supervisor”); and Patients and their Families (8 items, e.g., “Dealing with abusive patients”). In the present study, Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s ω values were satisfactory (Supplementary Table 1 ).

Work-family inter-role conflicts

Perceived work–family inter-role conflicts were assessed by using the Work–Family Conflict and Family–Work Conflict Scales (WFC and FWC) [ 64 , 65 ]. Each scale (WFC; e.g., “My job produces strain that makes it difficult to fulfil family duties”; FWC, e.g., “The demands of my family or spouse/partner interfere with work-related activities”) consists of 5 items on a 7-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = “Strongly disagree” to 7 = “Strongly agree”). In this study, Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s ω values were satisfactory (Supplementary Table 1 ).

- Work-related stress

Perceived work-related stress was assessed by using the Effort-Reward Imbalance Test (ERI Test) [ 13 , 66 ], which consists of 17 items on a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = “Disagree” to 5 = “Agree, and I am very distressed”) divided into three subscales, namely Effort (6 items, e.g., “Over the past few years, my job has become more and more demanding”), Material Reward (7 items, e.g., “Considering all my efforts and achievement, my salary/income is adequate”) and Esteem Reward (4 items, e.g., “I received the respect I deserve from my superiors”). In line with the ERI Model [ 13 ], in the present study, we have adopted the Effort-Reward Imbalance (ERI) ratio, which represents the ratio of perceived Effort (numerator) and perceived Rewards (denominator). ERI ratio can be calculated by using the following formula i.e., Effort score/Total Rewards score multiplied by a correction factor derived from the difference in the number of items for Effort and Rewards. ERI ratio increases with increasing values of the ratio, with cut-off score of 1 (ERI ratio > 1) indicating high levels of perceived imbalance [ 13 , 67 ]. In the present study, Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s ω values for Effort and Total Reward scales were satisfactory (Supplementary Table 1 ).

Work-resources

Perceived work resources were assessed by using the Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ) [ 14 ] and the Job Satisfaction Subscale from the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ) [ 68 ].

The Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ) [ 14 ] consists of 27 items on a four-point Likert scale (ranging from 0 = “Often” to 3 = “Never”) divided into three subscales, namely Job Demands, Job Control, and Social Support. In the present study, we used the two subscales of job control (14 items, e.g., “Do you have a choice in deciding how you do your work?”), and social support (4 items, e.g., “How often do you get help and support from your immediate superior?”). The Job Satisfaction subscale from the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ) [ 68 ] consists of four items on a 4-point Likert scale (ranging from 0 = “Highly unsatisfied” to 3 = “Very satisfied”), covering perceived satisfaction in the form of working conditions, perspectives and usage of abilities (4 items, e.g., Regarding your work in general, how pleased are you with your work prospects?). In the present study, Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s ω values for all Work-Resources were satisfactory (Supplementary Table 1 ).

Psychological and relational health conditions

Perceived levels of psychological and relational health conditions were assessed by using the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R) [ 69 , 70 ], which consists of 90 items on a five-point Likert scale (ranging from 0 = “Not at all” to 4 = “Extremely”), and divided into nine subscales, namely Anxiety, Phobic-Anxiety, Obsessive–Compulsive, Somatization, Depression, Interpersonal-Sensitivity, Hostility, Psychoticism, and Paranoid Ideation. In line with our research objectives, four subscales out of nine of the SCL-90-R were used, namely Anxiety (10 items, e.g., “Tense or keyed up”), Depression (13 items, e.g., “Hopeless about future”), Somatization (12 items, e.g., “Feeling weak”), Interpersonal-Sensitivity (9 items, e.g., “Feeling that people are unfriendly or dislike you”), and Hostility (6 items, e.g., “Having urges to break or smash things”). Additionally, in order to identify nurses reporting clinically relevant levels of symptoms, scores were also converted into percentages by using the cut-off points provided in the Italian validation study [ 70 ] according to age (adults) and to sex (i.e., Anxiety: cut-off men = 0.91, women = 1.31; Depression: cut-off men = 1.08, women = 1.62; Somatization: cut-off men = 1.09, women = 1.67; Interpersonal-Sensitivity: cut-off men = 1.01, women = 1.34; Hostility: cut-off men = 1.18, women = 1.34).

Data analysis