Handwashing in Communities: Clean Hands Save Lives

Regular handwashing is one of the best ways to remove germs, avoid getting sick, and prevent the spread of germs to others. Whether you are at home, at work, traveling, or out in the community, find out how handwashing with soap and water can protect you and your family.

Keeping hands clean can prevent 1 in 3 diarrheal illnesses and 1 in 5 respiratory infections, such as a cold or the flu.

School-based programs promoting hand hygiene can result in less illness and fewer missed school days.

When your family is healthy, you don’t have to worry about missing school, work, or other activities.

See CDC’s recommendations and resources for hand hygiene in healthcare settings.

Learn about key times to wash, the five steps, and more information.

See the data behind handwashing and using hand sanitizer.

Learn ways to promote hand hygiene in your home and community.

Learn information about when and how to use hand sanitizer.

Use resources to promote handwashing and prevent illness.

Find information on key hand hygiene topics.

Each year on October 15, this observance highlights the importance of handwashing.

Find links to information on trainings and educational resources.

Use CDC materials to raise awareness of hand hygiene in your community:

- Fact Sheets

- Social media library

To receive email updates about this topic, enter your email address:

Get answers to frequently asked questions about washing your hands and using hand sanitizer in community settings.

- Hand Hygiene at Work

- Handwashing: A Healthy Habit in the Kitchen

- Show Me the Science – How to Wash Your Hands

- Show Me the Science – When & How to Use Hand Sanitizer in Community Settings

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Yes, washing our hands really can help curb the spread of coronavirus

Professor and Programme Director, SA MRC Centre for Health Economics and Decision Science - PRICELESS SA (Priority Cost Effective Lessons in Systems Strengthening South Africa), University of the Witwatersrand

Associate Professor in the SAMRC Centre for Health Economics and Decision Science - PRICELESS SA (Priority Cost Effective Lessons in Systems Strengthening South Africa), University of the Witwatersrand

Disclosure statement

Karen Hofman currently receives research funding from the IDRC (Canada), UK Wellcome Trust, UK National Institutes for Health Research, Bloomberg Philanthropies and the South African Medical Research Council. In the past, she has also received funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, WHO and UNFPA.

Susan Goldstein is Associate Professor at the SA MRC Centre for Health Economics and Decision Science - PRICELESS SA (Priority Cost Effective Lessons in Systems Strengthening South Africa), School of Public Health, University of the Witwatersrand.

University of the Witwatersrand provides support as a hosting partner of The Conversation AFRICA.

View all partners

Much of the media discussion about coronavirus revolves around diagnosis and management of suspected cases. But the first piece of advice that is essential for anyone worried about contracting the coronavirus is something your grandparents might have suggested: wash your hands. It’s at the top of the list of many of the players trying to prevent the spread of the disease. This includes the World Health Organisation (WHO), the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other health authorities around the world.

But, ask the cynics, could preventing the spread of disease really be as simple as washing my hands?

The answer is yes. Because the science says so.

Hand washing is a tried and true, scientifically proven preventive strategy that reduces the likelihood of transmitting both viral and bacterial borne diseases. It has been shown to decrease both respiratory and diarrhoeal diseases in countries across the world. One review found that hand washing reduced diarrhoea cases by 30%. This is because it prevented bacteria being transmitted from faeces to the mouth.

It may seem like a low-cost – and incredibly simple – intervention. But not emphasising it would be a huge missed opportunity.

Read more: Why hand-washing really is as important as doctors say

The American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends the following five‑step approach:

1) Wet your hands and turn off the tap (to save water),

3) Rub your hands together for at least 20 seconds (possibly while singing Happy Birthday twice),

4) Rinse, and

Do this multiple times a day, especially before eating. Using hand sanitiser is another option, as long as it is composed of 60% or more alcohol.

The benefits of hand washing over other preventive measures are clear: soap is easy to access. Both soap and an alcohol-based products for cleaning hands are cost effective interventions.

But millions of us don’t wash our hands as often and as well as we should. A study done in South Korea indicated that 93.2% of 2,800 survey respondents did not wash their hands after coughing or sneezing.

The history

The current outbreak of the new coronavirus disease (COVID-19) was first reported on 31 December 2019 in Wuhan, China. By early March 2020 more than 90,000 people from 71 countries had been infected. More than 3,000 people have died so far. It is not clear what the fatality rate is and this may not be known until the outbreak is over – but it has been quoted as around 2.5% by the WHO.

Other diseases carry much higher fatalities. For example, tuberculosis claims the lives of 4,100 people worldwide every day. And the Ebola virus fatality rate is 50% .

Nevertheless, the spread of the new virus has set off alarm bells, with China famously building two hospitals in 10 days , cruise ships being quarantined and cities effectively being shut down .

The reason for the panic is that Corona-19 (more correctly named SARS-CoV-2) is a newly discovered virus. We don’t know exactly how infectious it is or who is at risk and why. As the WHO director-general said: we are entering uncharted territory .

Apart from hand washing it’s important to try not to touch one’s face and not shake hands. Face masks are really only useful for those who already have the virus or are caring with someone known to have the virus. Proper use of face masks is explained by the WHO.

Consideration should also be given to the fact that a run on medical masks could cause a shortage for public health-care workers who need them for protection against other diseases such as drug-resistant TB. This is particularly true in South Africa.

What the science says about hand washing

Research shows that hand washing isn’t just effective in preventing transmission of coronavirus. MIT recently conducted a study to identify the most effective mitigation strategy for hand hygiene that could contribute most to the reduction of global epidemic risk. Researchers used modelling and data‐driven simulations.

The study found that if 60% of travellers moving through airports worldwide had clean hands, global disease spread could be curbed by almost 70%. And if this rate could be maintained in only 10 of the busiest airports internationally, an astounding 37% of infections could be prevented.

Research has also shown that hand washing can prevent about 30% of diarrhoea-related sicknesses and about 20% of respiratory infections . Some scientists go as far as to argue that 80% of diseases can be prevented by proper hand washing.

Not everyone is convinced. Hand washing has been treated with scepticism as a significant disease prevention and eradication measure by some who favour “hard science interventions”.

This is not without precedent.

A Hungarian-born physician in the mid-19th century, Ignaz Semmelweis , was ostracised and shunned by his colleagues because he was so bold as to make a link between decreased maternal mortality and hand washing for doctors who went directly from the dissection halls to deliver babies.

Despite the growing body of research showing its effectiveness, hand washing habits are inadequate.

The MIT study assumes that 30% of people do not wash their hands at all after using a bathroom, and that correct hand washing is practised at such low rates that only 20% of people in airports actually have clean hands.

In South Africa, a national hand hygiene behaviour strategy estimated that only 20% of South Africans washed their hands with soap at critical times such as before, during and after preparing food, after going to the toilet, after sneezing or coughing, after touching animals, after changing nappies of babies, and after caring for an ill person.

Hand washing is simple and should already be part of everyone’s daily routine. If it became a habit for everyone in the world, it would not just prevent mortality and illness from coronavirus. It could be the start of a more viable strategy to prevent death from other bacterial and viral diseases.

While the full implications of this global pandemic are still unfolding, and a vaccine has yet to be developed, we need to act without delay using the one tool we already have.

- Public health

- Infectious diseases

- Coronavirus

- Hand hygiene

- Hand washing

- Disease prevention

Project Offier - Diversity & Inclusion

Senior Lecturer - Earth System Science

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Deputy Social Media Producer

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

Healthdirect Free Australian health advice you can count on.

Medical problem? Call 1800 022 222. If you need urgent medical help, call triple zero immediately

healthdirect Australia is a free service where you can talk to a nurse or doctor who can help you know what to do.

Hand washing

6-minute read

Share via email

There is a total of 5 error s on this form, details are below.

- Please enter your name

- Please enter your email

- Your email is invalid. Please check and try again

- Please enter recipient's email

- Recipient's email is invalid. Please check and try again

- Agree to Terms required

Error: This is required

Error: Not a valid value

- Hand washing is important because it helps to prevent the spread of infections such as COVID-19, colds, the flu and gastroenteritis.

- You should wash your hands before touching anything that needs to stay clean, and after touching anything that might contaminate your hands.

- Warm, soapy water is the best option for washing your hands when they are visibly dirty.

- Hand sanitiser is only effective if your hands have no visible dirt on them.

Why is good hand hygiene important?

Germs collect on your hands as you go about everyday life. When you touch your eyes, nose or mouth, the germs can spread to these vulnerable areas. So one of the best ways to avoid getting sick and spreading illness is to frequently wash your hands.

Hand washing helps prevent the spread of infections such as common colds, flu, COVID-19 and gastroenteritis . This is important, especially if you care for babies, older people or sick people who are more vulnerable to these illnesses.

Babies and children need to wash their hands too. They’re more vulnerable to getting infections because their immune systems aren’t yet mature.

If your child is too young to stand at a hand basin, you can wash their hands with disposable wipes or a wet, soapy cloth. Always make sure all soap is rinsed off and their hands thoroughly dried.

Teaching children good hand hygiene sets up lifelong habits to stop the spread of infection.

Hand washing is also one of the most important ways to prevent the spread of infection among people in hospital. People’s immune systems are often weakened after illness or surgery, so infections are easy to catch and can be hard to treat. They may then become life-threatening.

When should I wash my hands?

You should wash your hands before touching anything that needs to stay clean. You should also wash your hands after touching anything that might contaminate your hands or make them dirty.

Examples of times when you should wash your hands include:

- when your hands are visibly dirty

- after going to the toilet

- after helping a child go to the toilet, or changing a nappy

- after handling rubbish, household or garden chemicals, or anything that could be contaminated

- before you prepare or eat food

- after touching raw meat

- after blowing your nose or sneezing, or wiping a child’s nose

- after patting an animal

- after cleaning up blood, vomit or other body fluids

- after cleaning the bathroom

- before and after you visit a sick person in hospital

- before and after touching a wound, cut or rash

- before breastfeeding or feeding a child

- before handling medicine or applying ointment

- when holding a sick child

What is the best way to wash my hands?

Warm, soapy water is the best option for washing your hands when they are visibly dirty. Follow these simple tips on good hand hygiene.

To wash your hands:

- Wet hands with running water (preferably warm).

- Apply soap or liquid soap — enough to cover all of your hands. Normal soap is just as good as antibacterial soap.

- Rub your hands together for at least 20 seconds.

- Make sure you cover all surfaces, including the backs of your hands and in between your fingers.

- Rinse hands, making sure you remove all soap, and turn off the tap using the towel or paper towel.

- Dry your hands thoroughly with a paper towel, a clean hand towel or an air dryer if you are in a public toilet.

When should I use waterless hand sanitiser?

An alcohol-based hand rub (hand sanitiser) is a good way to clean your hands if you don't have access to soap and water. Hand sanitiser is only effective if your hands have no visible dirt on them.

To use hand sanitiser:

- Put about half a teaspoon of the product in the palm of your hand, rub your hands together, covering all the surfaces of your hand, including between your fingers.

- Keep rubbing until your hands are dry (about 20 to 30 seconds).

Alcohol-based hand sanitiser can be poisonous if swallowed. Follow these tips to keep kids safe around hand sanitiser.

Other tips for good hand hygiene

- Carry some hand sanitiser with you and use it whenever you want to decontaminate your hands, for example, after using public transport.

- Cough or sneeze into a tissue or your elbow, instead of into your hands.

- Wear disposable gloves before handling dirty nappies or cleaning up blood or any other body fluid.

- Be a good role model and encourage children to wash their hands properly and frequently.

- When using cloth towels to dry your hands, hang the towel up to dry after each use, and launder the towels regularly.

Learn more here about the development and quality assurance of healthdirect content .

Last reviewed: December 2023

Search our site for

- Food Hygiene

- Respiratory Hygiene

Need more information?

These trusted information partners have more on this topic.

Top results

How to hand wash correctly

Read more on St John Ambulance Australia website

Hand washing for hygiene | Health and wellbeing | Queensland Government

How to protect yourself from flu, e-coli, measles and other diseases by washing your hands.

Read more on Queensland Health website

Hand Hygiene | SA Health

Hand hygiene refers to any method which effectively removes soil and any harmful germs.

Read more on SA Health website

Handwashing - Why it's important - Better Health Channel

Washing your hands with soap and warm water can help stop the spread of infectious diseases.

Read more on Better Health Channel website

Patients and Carers - Sepsis Australia

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (USA) Global Sepsis Alliance Hand Hygiene Australia Infection Prevention & Healthcare Facilities – Australasian College for Infection Prevention and Control Limbs for Life Amputee Peer Support National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) Sepsis Factsheet Sepsis Alliance website Information on Treatment When a…

Read more on Sepsis Australia website

Hand Washing - Miracle Babies

Most illnesses are transmitted to infants by the hands; therefore regular hand washing is essential and is the single best way to avoid the spread of disease

Read more on Miracle Babies Foundation website

Hand washing | National Centre for Farmer Health

Washing your hands is one of the simplest, yet most effective, things you can do to protect your health and the health of others. Farmers come in contact with many potential sources of disease and illness. Read more...

Read more on National Centre for Farmer Health website

No Germs on Me | NT.GOV.AU

No Germs on Me campaign to promote hand washing in your community.

Read more on NT Health website

Childhood infections: minimising the spread - MyDr.com.au

The 3 most effective ways of stopping the spread of childhood infections are: getting your children vaccinated; keeping them at home when they are sick; and careful hand washing.

Read more on myDr website

Personal hygiene for children: in pictures | Raising Children Network

Our illustrated guide to personal hygiene for children covers hand-washing, bathing, toileting, cleaning teeth, blowing noses and more. Download or print.

Read more on raisingchildren.net.au website

Hand Hygiene | Ausmed

Thousands of people around the world die every day from infections caught while in care, and appropriate and adequate hand hygiene is a crucial prevention technique we can all utilise to reduce the spread of harmful infections and diseases.

Read more on Ausmed Education website

Compulsions | CRUfAD

CONTACT US URGENT CARE About Us Our Research For Patients For Clinicians Select Page Compulsions OCD Pages 271-276 from the Management of Mental Disorders, published by World Health Organization, Sydney

Read more on CRUfAD – Clinical Research Unit for Anxiety and Depression website

Superbugs Explained | Ausmed

Resistance to an antibiotic occurs when a microorganism grows in the presence of an antibiotic which would usually be sufficient to inhibit or kill organisms of the same species. The severity of a superbug depends on the number of different antibiotics the microorganism is resistant to.

Stool culture | Pathology Tests Explained

The stool culture is a test that detects and identifies bacteria that cause infections of the lower digestive tract. The test distinguishes between the types

Read more on Pathology Tests Explained website

Mycoplasma | Pathology Tests Explained

Mycoplasma testing is used to determine whether someone currently has or recently had a mycoplasma infection. It is a group of tests that either measure anti

Gastroenteritis Symptoms, Spread and Prevention | Ausmed

Gastroenteritis is an infection and inflammation of the stomach and intestines. It is a common illness with a variety of causes including viruses, bacteria, parasites, toxins, chemicals and drugs. There are many kinds of gastroenteritis, most of them contagious.

Cytomegalovirus | Pathology Tests Explained

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a common virus that occurs widely but rarely causes symptoms. In Australia, by the age of 20 years, around 50% of adults have been i

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) | Pathology Tests Explained

RSV testing is used to detect respiratory syncytial virus, the most common cause of lower respiratory tract infections in infants around the world. RSV tends

Healthdirect Australia is not responsible for the content and advertising on the external website you are now entering.

Healthdirect 24hr 7 days a week hotline

24 hour health advice you can count on

1800 022 222

Government Accredited with over 140 information partners

We are a government-funded service, providing quality, approved health information and advice

Healthdirect Australia acknowledges the Traditional Owners of Country throughout Australia and their continuing connection to land, sea and community. We pay our respects to the Traditional Owners and to Elders both past and present.

© 2024 Healthdirect Australia Limited

Support for this browser is being discontinued

Support for this browser is being discontinued for this site

- Internet Explorer 11 and lower

We currently support Microsoft Edge, Chrome, Firefox and Safari. For more information, please visit the links below:

- Chrome by Google

- Firefox by Mozilla

- Microsoft Edge

- Safari by Apple

You are welcome to continue browsing this site with this browser. Some features, tools or interaction may not work correctly.

- Publications

- Amplify! Blog

How handy is your handwashing policy?

Handwashing and drying might sound trivial to the uninitiated, but getting it right is a major action for reducing the spread of infectious diseases and staying healthy when working with children.

By CELA on 24 Sep, 2018

Handwashing and drying might sound trivial to the uninitiated, but getting it right is a major action for reducing the spread of infectious diseases and staying healthy when working with children. This story is by CELA Writers Margaret Paton and Bec Lloyd

Along with curriculum and ethics, work safety and inclusion, there’s another core topic most professional educators learn: how to wash and dry their hands correctly and how to teach children to do the same.

Gastrointestinal (gastro) and respiratory infections (colds and flu) of children attending early learning or OSHC are frustratingly common.

Wherever human beings gather together, there’s a risk of contagion. When you add in a high level of physical contact (including toileting) and lower immunity among young children who haven’t yet been exposed to every common germ, you can expect to see an even higher rate of transmission.

Dangers to children

While far less common in developed countries with ready access to clean water, the Centre for Disease Control estimates:

About 1.8 million children under the age of 5 die each year from diarrheal diseases and pneumonia, the top two killers of young children around the world 8 .

- Handwashing with soap could protect about 1 out of every 3 young children who get sick with diarrhea 2 , 3 and almost 1 out of 5 young children with respiratory infections like pneumonia 3 , 5 .

- Although people around the world clean their hands with water, very few use soap to wash their hands. Washing hands with soap removes germs much more effectively 9 .

- Handwashing education and access to soap in schools can help improve attendance 10 , 11 , 12 .

- Good handwashing early in life may help improve child development in some settings 13 .

- Estimated global rates of handwashing after using the toilet are only 19% 6 .

In Australia, new parents are often warned by friends and family to expect a couple of years of ‘catching everything’ when their baby or toddler commences long day care, with the consolation that many families see fewer missed school days later on because of increased immunity built up through earlier illnesses.

As one of the ‘bibles’ of this sector, Staying Healthy , explains, good handwashing practices are the single most important thing you can do to reduce exposure to many infectious illnesses for yourself, your colleagues, the children and their families.

Handwashing in the NQF

Handwashing is a fundamental means of supporting the aims of the National Quality Framework , particularly Element 2.1.2. You can also read in the need for good handwashing practices in Regulation 88 and Regulation 168(2)(c) of the Education and Care Services National Regulations (last updated 1 July 2018).

In fact, the regulations say that if an approved provider doesn’t take ‘reasonable steps’ to ‘prevent the spread of … infectious disease’ after an outbreak, they face a penalty of $2000, and another penalty of $1000 applies if providers fail to have appropriate policies and procedures in place to prevent infectious diseases – of course, this includes the critical act of washing and drying hands.

Apart from the penalties, there’s an awareness day coming up to remind us all how important this is. With Global Handwashing Day approaching on October 15 this year, it’s a good time to think about how handwashing works in your service or office.

Have you found a balance around the sustainability around water use and drying options, for example? Do you have a song or transition habit for the children’s handwashing that reinforces the practice? Do you make it easy for families to be your partners so that handwashing practices at your service are mirrored at home, too?

How good are Australians at handwashing?

The Hand Hygiene Australia (HHA) organisation collects data nationally – but mostly from hospitals.

Its three-month audit to the end of June this year showed an 85% good handwashing compliance rate. However, HHA is happy with that result, because the National Hand Hygiene Benchmark (which the Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council have set) is 80%.

Their site has smartphone apps to enter hand hygiene audit data, and collect data on a mobile. Plus you can learn more about the issue and complete an online training module . There’s even a free annual Hand Hygiene Workshop , which is being held in Brisbane this year on 18 November.

What works?

Dutch researchers who took on this topic in early childhood centres found that explicit instructions and prompts for adults (more so than the children) were best practice. Their research showed when visible, practical interventions were developed to target educators’ compliance with hand washing, they worked.

The interventions included free refills of paper towels, soap, alcohol-based hand sanitiser and hand cream for six months.

The educators were also given more individual training, an information booklet, and team training to work out how they could further improve. The research showed that children’s handwashing habits also improved in the services being studied.

When to wash

There are several credible resources to help you form or update your service’s policy and practices. Apart from Staying Healthy , the Australian Government’s Health Direct website has a good overview for anyone (not just people working with children) on when you need to wash your.

We’ve combined that list with other reputable sources to create this summary:

- on arriving and leaving your service

- when your hands are visibly dirty

- after going to the toilet

- after helping a child go to the toilet, or changing a nappy

- after handling rubbish, household or garden chemicals, or anything that could be contaminated

- before you prepare or eat food or handle a baby’s bottle

- after touching raw meat

- after wiping/blowing your nose or sneezing

- after patting an animal

- after cleaning up or touching sores, a wound/cut, blood, vomit or other body fluids or faeces

- after removing gloves

- before and after giving medication

- after playing outside

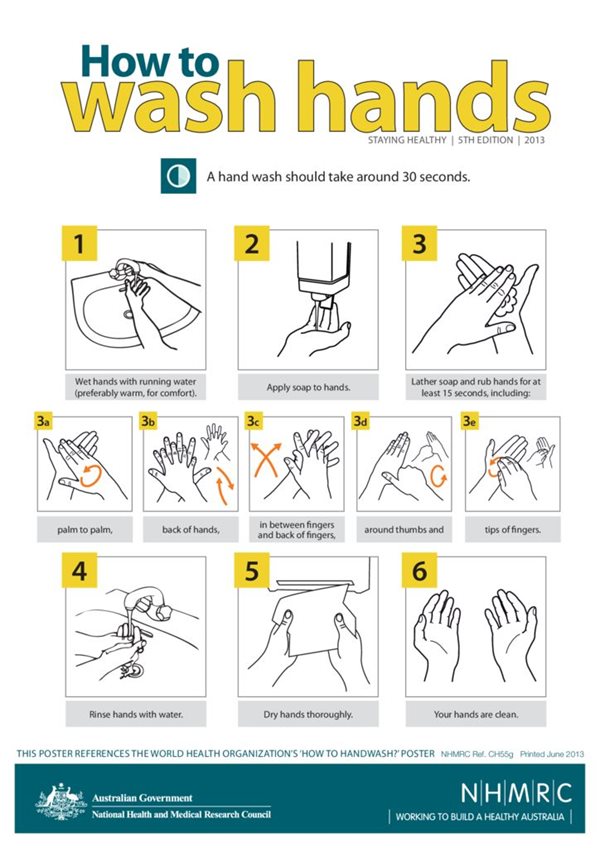

How to wash

Here’s the National Health and Medical Research Council’s six steps in a downloadable poster .

The key to good handwashing is time – around 30 seconds is the current recommendation, which is about the time it takes to sing two rounds of the Happy Birthday To You song.

The kinds of soap you use might vary according to special needs in your service for skin sensitivities or for the physical set up in your bathrooms and kitchens.

Be aware, though, that hand sanitiser is not recommended as a substitute for handwashing. Bacteria are clever at avoiding death-by-disinfectant and hand sanitisers are reportedly losing their effectiveness against some germs.

Read this recent NPR report for the story of how hand sanitisers in Australian hospitals may have actually increased the spread of some diseases.

A handwashing song ( If you’re happy and you know it tune)

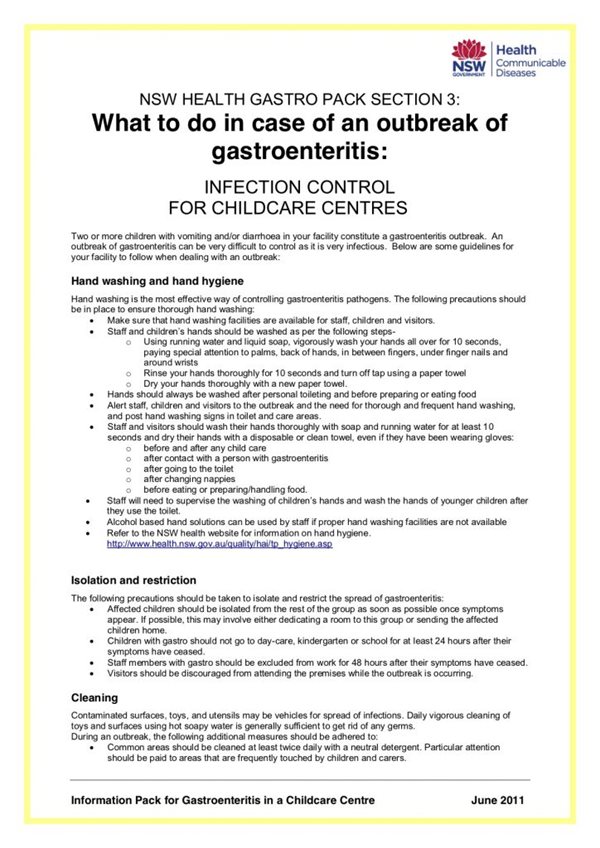

As for hand drying, paper towels are favoured by most of the sources we consulted. Take a look at NSW Health’s Gastro Pack advice about controlling infections in the early learning sector. We’ve included an extract below.

But it’s not all clear cut. A study in the international Infection, Disease & Health journal found children who dried their hands with a retractable cloth towel and a warm air dryer significantly reduced “bacterial numbers translocating to skin, food or a toy”.

Meanwhile, WorkSafe Western Australia’s Guidance Note on Reducing the Risk of Infectious Disease in Child Care Workplaces suggests using a paper towel or dryer. And a study from the Mayo Clinic in the USA comes out strongly recommending paper towels ‘in locations where hygiene is paramount, such as in hospitals and clinics’. That’s also endorsed by this researcher from the United Kingdom who completed a peer-reviewed study.

Sustainability balancing act

However, paper towels kill trees! So when handwashing appears in a service’s sustainability policy , it’s not unusual to see something like this approach we are quoting from Goolwa Children’s Centre in South Australia:

…where relevant, review policies and procedures within the service to find more sustainable outcomes, eg using hand dryers or washers instead of paper towel to dry hands.

It can be tricky to find a balance for two important outcomes – sanitation and sustainability – and like many other aspects of your professional procedures, where there is evidence backing a number of possible approaches you may just have to choose which is the best ‘fit’ for your service and your community.

And when in doubt, you can always turn to the Wiggles! The is a resource sheet here , and a UNICEF promoted video here.

Share your handwashing and drying habits with us in the comments – how are you doing it differently than in the past?

Related articles and resources

- Examples of a service’s hand washing policy and another one here

- ACECQA – Occasional Paper 2: Quality Area 2: Children’s health and safety

- Wash Your Hands song – Pinkfong Songs for Children on YouTube

- Myriam Sidibe’s TED talk on The Simple Power of Hand-washing

- Global Handwashing Day – October 15

- Downloads from Staying Healthy: Preventing infectious diseases in early childhood education and care services (5th Edition)

- Staying Healthy: Preventing infectious diseases in early childhood education and care services (5th Edition) (PDF, 3.3MB)

- The chain of infection – Poster (PDF, 211KB)

- Changing a nappy without spreading germs – Poster (PDF, 847KB)

- How to use alcohol-based hand rub – Poster (PDF, 552KB)

- How to wash hands – Poster (PDF, 771KB)

- Recommended minimum exclusion periods – Poster (856KB)

- The role of hands in the spread of infection – Poster (PDF, 325KB)

- Exclusion periods explained – Information for families (PDF, 1MB)

- Breaking the chain of infection – Information for families (PDF, 1.3MB)

- What causes infections – Information for families (PDF, 917KB)

- regulations

- sustainability

- The Wiggles

Community Early Learning Australia is a not for profit organisation with a focus on amplifying the value of early learning for every child across Australia - representing our members and uniting our sector as a force for quality education and care.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Guild Insurance

CELA’s insurer of choice. Protecting Australian businesses and individuals with tailored insurance products and caring personal service.

Thank you for requesting a new password.

If your email address is registered with CELA, you will receive a link to reset your password from us shortly. Please check your inbox and spam folder. If you need help, please call us on 1800 157 818.

Warm regards, The CELA team

Guest checkout

Join CELA to access discounts and member benefits.

Don't forget to log in to save!

Log in to access discounts and member benefits

Member Login

Forgot your password?

Don't have an account yet? Become a member today to access great free resources and discounted prices!

Become a member and save!

We launched our refreshed website on Friday 23 July. If you are logging in for the first time since the launch, you will need to request a new password using the 'forgot your password?' link below the 'confirm membership' box. Please check your spam inbox if you can’t find the new password, or call us on 1800 157 818 .

- Open access

- Published: 18 April 2024

Research ethics and artificial intelligence for global health: perspectives from the global forum on bioethics in research

- James Shaw 1 , 13 ,

- Joseph Ali 2 , 3 ,

- Caesar A. Atuire 4 , 5 ,

- Phaik Yeong Cheah 6 ,

- Armando Guio Español 7 ,

- Judy Wawira Gichoya 8 ,

- Adrienne Hunt 9 ,

- Daudi Jjingo 10 ,

- Katherine Littler 9 ,

- Daniela Paolotti 11 &

- Effy Vayena 12

BMC Medical Ethics volume 25 , Article number: 46 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

641 Accesses

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

The ethical governance of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in health care and public health continues to be an urgent issue for attention in policy, research, and practice. In this paper we report on central themes related to challenges and strategies for promoting ethics in research involving AI in global health, arising from the Global Forum on Bioethics in Research (GFBR), held in Cape Town, South Africa in November 2022.

The GFBR is an annual meeting organized by the World Health Organization and supported by the Wellcome Trust, the US National Institutes of Health, the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) and the South African MRC. The forum aims to bring together ethicists, researchers, policymakers, research ethics committee members and other actors to engage with challenges and opportunities specifically related to research ethics. In 2022 the focus of the GFBR was “Ethics of AI in Global Health Research”. The forum consisted of 6 case study presentations, 16 governance presentations, and a series of small group and large group discussions. A total of 87 participants attended the forum from 31 countries around the world, representing disciplines of bioethics, AI, health policy, health professional practice, research funding, and bioinformatics. In this paper, we highlight central insights arising from GFBR 2022.

We describe the significance of four thematic insights arising from the forum: (1) Appropriateness of building AI, (2) Transferability of AI systems, (3) Accountability for AI decision-making and outcomes, and (4) Individual consent. We then describe eight recommendations for governance leaders to enhance the ethical governance of AI in global health research, addressing issues such as AI impact assessments, environmental values, and fair partnerships.

Conclusions

The 2022 Global Forum on Bioethics in Research illustrated several innovations in ethical governance of AI for global health research, as well as several areas in need of urgent attention internationally. This summary is intended to inform international and domestic efforts to strengthen research ethics and support the evolution of governance leadership to meet the demands of AI in global health research.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The ethical governance of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in health care and public health continues to be an urgent issue for attention in policy, research, and practice [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. Beyond the growing number of AI applications being implemented in health care, capabilities of AI models such as Large Language Models (LLMs) expand the potential reach and significance of AI technologies across health-related fields [ 4 , 5 ]. Discussion about effective, ethical governance of AI technologies has spanned a range of governance approaches, including government regulation, organizational decision-making, professional self-regulation, and research ethics review [ 6 , 7 , 8 ]. In this paper, we report on central themes related to challenges and strategies for promoting ethics in research involving AI in global health research, arising from the Global Forum on Bioethics in Research (GFBR), held in Cape Town, South Africa in November 2022. Although applications of AI for research, health care, and public health are diverse and advancing rapidly, the insights generated at the forum remain highly relevant from a global health perspective. After summarizing important context for work in this domain, we highlight categories of ethical issues emphasized at the forum for attention from a research ethics perspective internationally. We then outline strategies proposed for research, innovation, and governance to support more ethical AI for global health.

In this paper, we adopt the definition of AI systems provided by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) as our starting point. Their definition states that an AI system is “a machine-based system that can, for a given set of human-defined objectives, make predictions, recommendations, or decisions influencing real or virtual environments. AI systems are designed to operate with varying levels of autonomy” [ 9 ]. The conceptualization of an algorithm as helping to constitute an AI system, along with hardware, other elements of software, and a particular context of use, illustrates the wide variety of ways in which AI can be applied. We have found it useful to differentiate applications of AI in research as those classified as “AI systems for discovery” and “AI systems for intervention”. An AI system for discovery is one that is intended to generate new knowledge, for example in drug discovery or public health research in which researchers are seeking potential targets for intervention, innovation, or further research. An AI system for intervention is one that directly contributes to enacting an intervention in a particular context, for example informing decision-making at the point of care or assisting with accuracy in a surgical procedure.

The mandate of the GFBR is to take a broad view of what constitutes research and its regulation in global health, with special attention to bioethics in Low- and Middle- Income Countries. AI as a group of technologies demands such a broad view. AI development for health occurs in a variety of environments, including universities and academic health sciences centers where research ethics review remains an important element of the governance of science and innovation internationally [ 10 , 11 ]. In these settings, research ethics committees (RECs; also known by different names such as Institutional Review Boards or IRBs) make decisions about the ethical appropriateness of projects proposed by researchers and other institutional members, ultimately determining whether a given project is allowed to proceed on ethical grounds [ 12 ].

However, research involving AI for health also takes place in large corporations and smaller scale start-ups, which in some jurisdictions fall outside the scope of research ethics regulation. In the domain of AI, the question of what constitutes research also becomes blurred. For example, is the development of an algorithm itself considered a part of the research process? Or only when that algorithm is tested under the formal constraints of a systematic research methodology? In this paper we take an inclusive view, in which AI development is included in the definition of research activity and within scope for our inquiry, regardless of the setting in which it takes place. This broad perspective characterizes the approach to “research ethics” we take in this paper, extending beyond the work of RECs to include the ethical analysis of the wide range of activities that constitute research as the generation of new knowledge and intervention in the world.

Ethical governance of AI in global health

The ethical governance of AI for global health has been widely discussed in recent years. The World Health Organization (WHO) released its guidelines on ethics and governance of AI for health in 2021, endorsing a set of six ethical principles and exploring the relevance of those principles through a variety of use cases. The WHO guidelines also provided an overview of AI governance, defining governance as covering “a range of steering and rule-making functions of governments and other decision-makers, including international health agencies, for the achievement of national health policy objectives conducive to universal health coverage.” (p. 81) The report usefully provided a series of recommendations related to governance of seven domains pertaining to AI for health: data, benefit sharing, the private sector, the public sector, regulation, policy observatories/model legislation, and global governance. The report acknowledges that much work is yet to be done to advance international cooperation on AI governance, especially related to prioritizing voices from Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) in global dialogue.

One important point emphasized in the WHO report that reinforces the broader literature on global governance of AI is the distribution of responsibility across a wide range of actors in the AI ecosystem. This is especially important to highlight when focused on research for global health, which is specifically about work that transcends national borders. Alami et al. (2020) discussed the unique risks raised by AI research in global health, ranging from the unavailability of data in many LMICs required to train locally relevant AI models to the capacity of health systems to absorb new AI technologies that demand the use of resources from elsewhere in the system. These observations illustrate the need to identify the unique issues posed by AI research for global health specifically, and the strategies that can be employed by all those implicated in AI governance to promote ethically responsible use of AI in global health research.

RECs and the regulation of research involving AI

RECs represent an important element of the governance of AI for global health research, and thus warrant further commentary as background to our paper. Despite the importance of RECs, foundational questions have been raised about their capabilities to accurately understand and address ethical issues raised by studies involving AI. Rahimzadeh et al. (2023) outlined how RECs in the United States are under-prepared to align with recent federal policy requiring that RECs review data sharing and management plans with attention to the unique ethical issues raised in AI research for health [ 13 ]. Similar research in South Africa identified variability in understanding of existing regulations and ethical issues associated with health-related big data sharing and management among research ethics committee members [ 14 , 15 ]. The effort to address harms accruing to groups or communities as opposed to individuals whose data are included in AI research has also been identified as a unique challenge for RECs [ 16 , 17 ]. Doerr and Meeder (2022) suggested that current regulatory frameworks for research ethics might actually prevent RECs from adequately addressing such issues, as they are deemed out of scope of REC review [ 16 ]. Furthermore, research in the United Kingdom and Canada has suggested that researchers using AI methods for health tend to distinguish between ethical issues and social impact of their research, adopting an overly narrow view of what constitutes ethical issues in their work [ 18 ].

The challenges for RECs in adequately addressing ethical issues in AI research for health care and public health exceed a straightforward survey of ethical considerations. As Ferretti et al. (2021) contend, some capabilities of RECs adequately cover certain issues in AI-based health research, such as the common occurrence of conflicts of interest where researchers who accept funds from commercial technology providers are implicitly incentivized to produce results that align with commercial interests [ 12 ]. However, some features of REC review require reform to adequately meet ethical needs. Ferretti et al. outlined weaknesses of RECs that are longstanding and those that are novel to AI-related projects, proposing a series of directions for development that are regulatory, procedural, and complementary to REC functionality. The work required on a global scale to update the REC function in response to the demands of research involving AI is substantial.

These issues take greater urgency in the context of global health [ 19 ]. Teixeira da Silva (2022) described the global practice of “ethics dumping”, where researchers from high income countries bring ethically contentious practices to RECs in low-income countries as a strategy to gain approval and move projects forward [ 20 ]. Although not yet systematically documented in AI research for health, risk of ethics dumping in AI research is high. Evidence is already emerging of practices of “health data colonialism”, in which AI researchers and developers from large organizations in high-income countries acquire data to build algorithms in LMICs to avoid stricter regulations [ 21 ]. This specific practice is part of a larger collection of practices that characterize health data colonialism, involving the broader exploitation of data and the populations they represent primarily for commercial gain [ 21 , 22 ]. As an additional complication, AI algorithms trained on data from high-income contexts are unlikely to apply in straightforward ways to LMIC settings [ 21 , 23 ]. In the context of global health, there is widespread acknowledgement about the need to not only enhance the knowledge base of REC members about AI-based methods internationally, but to acknowledge the broader shifts required to encourage their capabilities to more fully address these and other ethical issues associated with AI research for health [ 8 ].

Although RECs are an important part of the story of the ethical governance of AI for global health research, they are not the only part. The responsibilities of supra-national entities such as the World Health Organization, national governments, organizational leaders, commercial AI technology providers, health care professionals, and other groups continue to be worked out internationally. In this context of ongoing work, examining issues that demand attention and strategies to address them remains an urgent and valuable task.

The GFBR is an annual meeting organized by the World Health Organization and supported by the Wellcome Trust, the US National Institutes of Health, the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) and the South African MRC. The forum aims to bring together ethicists, researchers, policymakers, REC members and other actors to engage with challenges and opportunities specifically related to research ethics. Each year the GFBR meeting includes a series of case studies and keynotes presented in plenary format to an audience of approximately 100 people who have applied and been competitively selected to attend, along with small-group breakout discussions to advance thinking on related issues. The specific topic of the forum changes each year, with past topics including ethical issues in research with people living with mental health conditions (2021), genome editing (2019), and biobanking/data sharing (2018). The forum is intended to remain grounded in the practical challenges of engaging in research ethics, with special interest in low resource settings from a global health perspective. A post-meeting fellowship scheme is open to all LMIC participants, providing a unique opportunity to apply for funding to further explore and address the ethical challenges that are identified during the meeting.

In 2022, the focus of the GFBR was “Ethics of AI in Global Health Research”. The forum consisted of 6 case study presentations (both short and long form) reporting on specific initiatives related to research ethics and AI for health, and 16 governance presentations (both short and long form) reporting on actual approaches to governing AI in different country settings. A keynote presentation from Professor Effy Vayena addressed the topic of the broader context for AI ethics in a rapidly evolving field. A total of 87 participants attended the forum from 31 countries around the world, representing disciplines of bioethics, AI, health policy, health professional practice, research funding, and bioinformatics. The 2-day forum addressed a wide range of themes. The conference report provides a detailed overview of each of the specific topics addressed while a policy paper outlines the cross-cutting themes (both documents are available at the GFBR website: https://www.gfbr.global/past-meetings/16th-forum-cape-town-south-africa-29-30-november-2022/ ). As opposed to providing a detailed summary in this paper, we aim to briefly highlight central issues raised, solutions proposed, and the challenges facing the research ethics community in the years to come.

In this way, our primary aim in this paper is to present a synthesis of the challenges and opportunities raised at the GFBR meeting and in the planning process, followed by our reflections as a group of authors on their significance for governance leaders in the coming years. We acknowledge that the views represented at the meeting and in our results are a partial representation of the universe of views on this topic; however, the GFBR leadership invested a great deal of resources in convening a deeply diverse and thoughtful group of researchers and practitioners working on themes of bioethics related to AI for global health including those based in LMICs. We contend that it remains rare to convene such a strong group for an extended time and believe that many of the challenges and opportunities raised demand attention for more ethical futures of AI for health. Nonetheless, our results are primarily descriptive and are thus not explicitly grounded in a normative argument. We make effort in the Discussion section to contextualize our results by describing their significance and connecting them to broader efforts to reform global health research and practice.

Uniquely important ethical issues for AI in global health research

Presentations and group dialogue over the course of the forum raised several issues for consideration, and here we describe four overarching themes for the ethical governance of AI in global health research. Brief descriptions of each issue can be found in Table 1 . Reports referred to throughout the paper are available at the GFBR website provided above.

The first overarching thematic issue relates to the appropriateness of building AI technologies in response to health-related challenges in the first place. Case study presentations referred to initiatives where AI technologies were highly appropriate, such as in ear shape biometric identification to more accurately link electronic health care records to individual patients in Zambia (Alinani Simukanga). Although important ethical issues were raised with respect to privacy, trust, and community engagement in this initiative, the AI-based solution was appropriately matched to the challenge of accurately linking electronic records to specific patient identities. In contrast, forum participants raised questions about the appropriateness of an initiative using AI to improve the quality of handwashing practices in an acute care hospital in India (Niyoshi Shah), which led to gaming the algorithm. Overall, participants acknowledged the dangers of techno-solutionism, in which AI researchers and developers treat AI technologies as the most obvious solutions to problems that in actuality demand much more complex strategies to address [ 24 ]. However, forum participants agreed that RECs in different contexts have differing degrees of power to raise issues of the appropriateness of an AI-based intervention.

The second overarching thematic issue related to whether and how AI-based systems transfer from one national health context to another. One central issue raised by a number of case study presentations related to the challenges of validating an algorithm with data collected in a local environment. For example, one case study presentation described a project that would involve the collection of personally identifiable data for sensitive group identities, such as tribe, clan, or religion, in the jurisdictions involved (South Africa, Nigeria, Tanzania, Uganda and the US; Gakii Masunga). Doing so would enable the team to ensure that those groups were adequately represented in the dataset to ensure the resulting algorithm was not biased against specific community groups when deployed in that context. However, some members of these communities might desire to be represented in the dataset, whereas others might not, illustrating the need to balance autonomy and inclusivity. It was also widely recognized that collecting these data is an immense challenge, particularly when historically oppressive practices have led to a low-trust environment for international organizations and the technologies they produce. It is important to note that in some countries such as South Africa and Rwanda, it is illegal to collect information such as race and tribal identities, re-emphasizing the importance for cultural awareness and avoiding “one size fits all” solutions.

The third overarching thematic issue is related to understanding accountabilities for both the impacts of AI technologies and governance decision-making regarding their use. Where global health research involving AI leads to longer-term harms that might fall outside the usual scope of issues considered by a REC, who is to be held accountable, and how? This question was raised as one that requires much further attention, with law being mixed internationally regarding the mechanisms available to hold researchers, innovators, and their institutions accountable over the longer term. However, it was recognized in breakout group discussion that many jurisdictions are developing strong data protection regimes related specifically to international collaboration for research involving health data. For example, Kenya’s Data Protection Act requires that any internationally funded projects have a local principal investigator who will hold accountability for how data are shared and used [ 25 ]. The issue of research partnerships with commercial entities was raised by many participants in the context of accountability, pointing toward the urgent need for clear principles related to strategies for engagement with commercial technology companies in global health research.

The fourth and final overarching thematic issue raised here is that of consent. The issue of consent was framed by the widely shared recognition that models of individual, explicit consent might not produce a supportive environment for AI innovation that relies on the secondary uses of health-related datasets to build AI algorithms. Given this recognition, approaches such as community oversight of health data uses were suggested as a potential solution. However, the details of implementing such community oversight mechanisms require much further attention, particularly given the unique perspectives on health data in different country settings in global health research. Furthermore, some uses of health data do continue to require consent. One case study of South Africa, Nigeria, Kenya, Ethiopia and Uganda suggested that when health data are shared across borders, individual consent remains necessary when data is transferred from certain countries (Nezerith Cengiz). Broader clarity is necessary to support the ethical governance of health data uses for AI in global health research.

Recommendations for ethical governance of AI in global health research

Dialogue at the forum led to a range of suggestions for promoting ethical conduct of AI research for global health, related to the various roles of actors involved in the governance of AI research broadly defined. The strategies are written for actors we refer to as “governance leaders”, those people distributed throughout the AI for global health research ecosystem who are responsible for ensuring the ethical and socially responsible conduct of global health research involving AI (including researchers themselves). These include RECs, government regulators, health care leaders, health professionals, corporate social accountability officers, and others. Enacting these strategies would bolster the ethical governance of AI for global health more generally, enabling multiple actors to fulfill their roles related to governing research and development activities carried out across multiple organizations, including universities, academic health sciences centers, start-ups, and technology corporations. Specific suggestions are summarized in Table 2 .

First, forum participants suggested that governance leaders including RECs, should remain up to date on recent advances in the regulation of AI for health. Regulation of AI for health advances rapidly and takes on different forms in jurisdictions around the world. RECs play an important role in governance, but only a partial role; it was deemed important for RECs to acknowledge how they fit within a broader governance ecosystem in order to more effectively address the issues within their scope. Not only RECs but organizational leaders responsible for procurement, researchers, and commercial actors should all commit to efforts to remain up to date about the relevant approaches to regulating AI for health care and public health in jurisdictions internationally. In this way, governance can more adequately remain up to date with advances in regulation.

Second, forum participants suggested that governance leaders should focus on ethical governance of health data as a basis for ethical global health AI research. Health data are considered the foundation of AI development, being used to train AI algorithms for various uses [ 26 ]. By focusing on ethical governance of health data generation, sharing, and use, multiple actors will help to build an ethical foundation for AI development among global health researchers.

Third, forum participants believed that governance processes should incorporate AI impact assessments where appropriate. An AI impact assessment is the process of evaluating the potential effects, both positive and negative, of implementing an AI algorithm on individuals, society, and various stakeholders, generally over time frames specified in advance of implementation [ 27 ]. Although not all types of AI research in global health would warrant an AI impact assessment, this is especially relevant for those studies aiming to implement an AI system for intervention into health care or public health. Organizations such as RECs can use AI impact assessments to boost understanding of potential harms at the outset of a research project, encouraging researchers to more deeply consider potential harms in the development of their study.

Fourth, forum participants suggested that governance decisions should incorporate the use of environmental impact assessments, or at least the incorporation of environment values when assessing the potential impact of an AI system. An environmental impact assessment involves evaluating and anticipating the potential environmental effects of a proposed project to inform ethical decision-making that supports sustainability [ 28 ]. Although a relatively new consideration in research ethics conversations [ 29 ], the environmental impact of building technologies is a crucial consideration for the public health commitment to environmental sustainability. Governance leaders can use environmental impact assessments to boost understanding of potential environmental harms linked to AI research projects in global health over both the shorter and longer terms.

Fifth, forum participants suggested that governance leaders should require stronger transparency in the development of AI algorithms in global health research. Transparency was considered essential in the design and development of AI algorithms for global health to ensure ethical and accountable decision-making throughout the process. Furthermore, whether and how researchers have considered the unique contexts into which such algorithms may be deployed can be surfaced through stronger transparency, for example in describing what primary considerations were made at the outset of the project and which stakeholders were consulted along the way. Sharing information about data provenance and methods used in AI development will also enhance the trustworthiness of the AI-based research process.

Sixth, forum participants suggested that governance leaders can encourage or require community engagement at various points throughout an AI project. It was considered that engaging patients and communities is crucial in AI algorithm development to ensure that the technology aligns with community needs and values. However, participants acknowledged that this is not a straightforward process. Effective community engagement requires lengthy commitments to meeting with and hearing from diverse communities in a given setting, and demands a particular set of skills in communication and dialogue that are not possessed by all researchers. Encouraging AI researchers to begin this process early and build long-term partnerships with community members is a promising strategy to deepen community engagement in AI research for global health. One notable recommendation was that research funders have an opportunity to incentivize and enable community engagement with funds dedicated to these activities in AI research in global health.

Seventh, forum participants suggested that governance leaders can encourage researchers to build strong, fair partnerships between institutions and individuals across country settings. In a context of longstanding imbalances in geopolitical and economic power, fair partnerships in global health demand a priori commitments to share benefits related to advances in medical technologies, knowledge, and financial gains. Although enforcement of this point might be beyond the remit of RECs, commentary will encourage researchers to consider stronger, fairer partnerships in global health in the longer term.

Eighth, it became evident that it is necessary to explore new forms of regulatory experimentation given the complexity of regulating a technology of this nature. In addition, the health sector has a series of particularities that make it especially complicated to generate rules that have not been previously tested. Several participants highlighted the desire to promote spaces for experimentation such as regulatory sandboxes or innovation hubs in health. These spaces can have several benefits for addressing issues surrounding the regulation of AI in the health sector, such as: (i) increasing the capacities and knowledge of health authorities about this technology; (ii) identifying the major problems surrounding AI regulation in the health sector; (iii) establishing possibilities for exchange and learning with other authorities; (iv) promoting innovation and entrepreneurship in AI in health; and (vi) identifying the need to regulate AI in this sector and update other existing regulations.

Ninth and finally, forum participants believed that the capabilities of governance leaders need to evolve to better incorporate expertise related to AI in ways that make sense within a given jurisdiction. With respect to RECs, for example, it might not make sense for every REC to recruit a member with expertise in AI methods. Rather, it will make more sense in some jurisdictions to consult with members of the scientific community with expertise in AI when research protocols are submitted that demand such expertise. Furthermore, RECs and other approaches to research governance in jurisdictions around the world will need to evolve in order to adopt the suggestions outlined above, developing processes that apply specifically to the ethical governance of research using AI methods in global health.

Research involving the development and implementation of AI technologies continues to grow in global health, posing important challenges for ethical governance of AI in global health research around the world. In this paper we have summarized insights from the 2022 GFBR, focused specifically on issues in research ethics related to AI for global health research. We summarized four thematic challenges for governance related to AI in global health research and nine suggestions arising from presentations and dialogue at the forum. In this brief discussion section, we present an overarching observation about power imbalances that frames efforts to evolve the role of governance in global health research, and then outline two important opportunity areas as the field develops to meet the challenges of AI in global health research.

Dialogue about power is not unfamiliar in global health, especially given recent contributions exploring what it would mean to de-colonize global health research, funding, and practice [ 30 , 31 ]. Discussions of research ethics applied to AI research in global health contexts are deeply infused with power imbalances. The existing context of global health is one in which high-income countries primarily located in the “Global North” charitably invest in projects taking place primarily in the “Global South” while recouping knowledge, financial, and reputational benefits [ 32 ]. With respect to AI development in particular, recent examples of digital colonialism frame dialogue about global partnerships, raising attention to the role of large commercial entities and global financial capitalism in global health research [ 21 , 22 ]. Furthermore, the power of governance organizations such as RECs to intervene in the process of AI research in global health varies widely around the world, depending on the authorities assigned to them by domestic research governance policies. These observations frame the challenges outlined in our paper, highlighting the difficulties associated with making meaningful change in this field.

Despite these overarching challenges of the global health research context, there are clear strategies for progress in this domain. Firstly, AI innovation is rapidly evolving, which means approaches to the governance of AI for health are rapidly evolving too. Such rapid evolution presents an important opportunity for governance leaders to clarify their vision and influence over AI innovation in global health research, boosting the expertise, structure, and functionality required to meet the demands of research involving AI. Secondly, the research ethics community has strong international ties, linked to a global scholarly community that is committed to sharing insights and best practices around the world. This global community can be leveraged to coordinate efforts to produce advances in the capabilities and authorities of governance leaders to meaningfully govern AI research for global health given the challenges summarized in our paper.

Limitations

Our paper includes two specific limitations that we address explicitly here. First, it is still early in the lifetime of the development of applications of AI for use in global health, and as such, the global community has had limited opportunity to learn from experience. For example, there were many fewer case studies, which detail experiences with the actual implementation of an AI technology, submitted to GFBR 2022 for consideration than was expected. In contrast, there were many more governance reports submitted, which detail the processes and outputs of governance processes that anticipate the development and dissemination of AI technologies. This observation represents both a success and a challenge. It is a success that so many groups are engaging in anticipatory governance of AI technologies, exploring evidence of their likely impacts and governing technologies in novel and well-designed ways. It is a challenge that there is little experience to build upon of the successful implementation of AI technologies in ways that have limited harms while promoting innovation. Further experience with AI technologies in global health will contribute to revising and enhancing the challenges and recommendations we have outlined in our paper.

Second, global trends in the politics and economics of AI technologies are evolving rapidly. Although some nations are advancing detailed policy approaches to regulating AI more generally, including for uses in health care and public health, the impacts of corporate investments in AI and political responses related to governance remain to be seen. The excitement around large language models (LLMs) and large multimodal models (LMMs) has drawn deeper attention to the challenges of regulating AI in any general sense, opening dialogue about health sector-specific regulations. The direction of this global dialogue, strongly linked to high-profile corporate actors and multi-national governance institutions, will strongly influence the development of boundaries around what is possible for the ethical governance of AI for global health. We have written this paper at a point when these developments are proceeding rapidly, and as such, we acknowledge that our recommendations will need updating as the broader field evolves.

Ultimately, coordination and collaboration between many stakeholders in the research ethics ecosystem will be necessary to strengthen the ethical governance of AI in global health research. The 2022 GFBR illustrated several innovations in ethical governance of AI for global health research, as well as several areas in need of urgent attention internationally. This summary is intended to inform international and domestic efforts to strengthen research ethics and support the evolution of governance leadership to meet the demands of AI in global health research.

Data availability

All data and materials analyzed to produce this paper are available on the GFBR website: https://www.gfbr.global/past-meetings/16th-forum-cape-town-south-africa-29-30-november-2022/ .

Clark P, Kim J, Aphinyanaphongs Y, Marketing, Food US. Drug Administration Clearance of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Enabled Software in and as Medical devices: a systematic review. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(7):e2321792–2321792.

Article Google Scholar

Potnis KC, Ross JS, Aneja S, Gross CP, Richman IB. Artificial intelligence in breast cancer screening: evaluation of FDA device regulation and future recommendations. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(12):1306–12.

Siala H, Wang Y. SHIFTing artificial intelligence to be responsible in healthcare: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2022;296:114782.

Yang X, Chen A, PourNejatian N, Shin HC, Smith KE, Parisien C, et al. A large language model for electronic health records. NPJ Digit Med. 2022;5(1):194.

Meskó B, Topol EJ. The imperative for regulatory oversight of large language models (or generative AI) in healthcare. NPJ Digit Med. 2023;6(1):120.

Jobin A, Ienca M, Vayena E. The global landscape of AI ethics guidelines. Nat Mach Intell. 2019;1(9):389–99.

Minssen T, Vayena E, Cohen IG. The challenges for Regulating Medical Use of ChatGPT and other large Language models. JAMA. 2023.

Ho CWL, Malpani R. Scaling up the research ethics framework for healthcare machine learning as global health ethics and governance. Am J Bioeth. 2022;22(5):36–8.

Yeung K. Recommendation of the council on artificial intelligence (OECD). Int Leg Mater. 2020;59(1):27–34.

Maddox TM, Rumsfeld JS, Payne PR. Questions for artificial intelligence in health care. JAMA. 2019;321(1):31–2.

Dzau VJ, Balatbat CA, Ellaissi WF. Revisiting academic health sciences systems a decade later: discovery to health to population to society. Lancet. 2021;398(10318):2300–4.

Ferretti A, Ienca M, Sheehan M, Blasimme A, Dove ES, Farsides B, et al. Ethics review of big data research: what should stay and what should be reformed? BMC Med Ethics. 2021;22(1):1–13.

Rahimzadeh V, Serpico K, Gelinas L. Institutional review boards need new skills to review data sharing and management plans. Nat Med. 2023;1–3.

Kling S, Singh S, Burgess TL, Nair G. The role of an ethics advisory committee in data science research in sub-saharan Africa. South Afr J Sci. 2023;119(5–6):1–3.

Google Scholar

Cengiz N, Kabanda SM, Esterhuizen TM, Moodley K. Exploring perspectives of research ethics committee members on the governance of big data in sub-saharan Africa. South Afr J Sci. 2023;119(5–6):1–9.

Doerr M, Meeder S. Big health data research and group harm: the scope of IRB review. Ethics Hum Res. 2022;44(4):34–8.

Ballantyne A, Stewart C. Big data and public-private partnerships in healthcare and research: the application of an ethics framework for big data in health and research. Asian Bioeth Rev. 2019;11(3):315–26.

Samuel G, Chubb J, Derrick G. Boundaries between research ethics and ethical research use in artificial intelligence health research. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2021;16(3):325–37.

Murphy K, Di Ruggiero E, Upshur R, Willison DJ, Malhotra N, Cai JC, et al. Artificial intelligence for good health: a scoping review of the ethics literature. BMC Med Ethics. 2021;22(1):1–17.

Teixeira da Silva JA. Handling ethics dumping and neo-colonial research: from the laboratory to the academic literature. J Bioethical Inq. 2022;19(3):433–43.

Ferryman K. The dangers of data colonialism in precision public health. Glob Policy. 2021;12:90–2.

Couldry N, Mejias UA. Data colonialism: rethinking big data’s relation to the contemporary subject. Telev New Media. 2019;20(4):336–49.

Organization WH. Ethics and governance of artificial intelligence for health: WHO guidance. 2021.

Metcalf J, Moss E. Owning ethics: corporate logics, silicon valley, and the institutionalization of ethics. Soc Res Int Q. 2019;86(2):449–76.

Data Protection Act - OFFICE OF THE DATA PROTECTION COMMISSIONER KENYA [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2023 Sep 30]. https://www.odpc.go.ke/dpa-act/ .

Sharon T, Lucivero F. Introduction to the special theme: the expansion of the health data ecosystem–rethinking data ethics and governance. Big Data & Society. Volume 6. London, England: SAGE Publications Sage UK; 2019. p. 2053951719852969.

Reisman D, Schultz J, Crawford K, Whittaker M. Algorithmic impact assessments: a practical Framework for Public Agency. AI Now. 2018.

Morgan RK. Environmental impact assessment: the state of the art. Impact Assess Proj Apprais. 2012;30(1):5–14.

Samuel G, Richie C. Reimagining research ethics to include environmental sustainability: a principled approach, including a case study of data-driven health research. J Med Ethics. 2023;49(6):428–33.

Kwete X, Tang K, Chen L, Ren R, Chen Q, Wu Z, et al. Decolonizing global health: what should be the target of this movement and where does it lead us? Glob Health Res Policy. 2022;7(1):3.

Abimbola S, Asthana S, Montenegro C, Guinto RR, Jumbam DT, Louskieter L, et al. Addressing power asymmetries in global health: imperatives in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS Med. 2021;18(4):e1003604.

Benatar S. Politics, power, poverty and global health: systems and frames. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2016;5(10):599.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the outstanding contributions of the attendees of GFBR 2022 in Cape Town, South Africa. This paper is authored by members of the GFBR 2022 Planning Committee. We would like to acknowledge additional members Tamra Lysaght, National University of Singapore, and Niresh Bhagwandin, South African Medical Research Council, for their input during the planning stages and as reviewers of the applications to attend the Forum.

This work was supported by Wellcome [222525/Z/21/Z], the US National Institutes of Health, the UK Medical Research Council (part of UK Research and Innovation), and the South African Medical Research Council through funding to the Global Forum on Bioethics in Research.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Physical Therapy, Temerty Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

Berman Institute of Bioethics, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA

Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA

Department of Philosophy and Classics, University of Ghana, Legon-Accra, Ghana

Caesar A. Atuire

Centre for Tropical Medicine and Global Health, Nuffield Department of Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

Mahidol Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit, Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand

Phaik Yeong Cheah

Berkman Klein Center, Harvard University, Bogotá, Colombia

Armando Guio Español

Department of Radiology and Informatics, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA

Judy Wawira Gichoya

Health Ethics & Governance Unit, Research for Health Department, Science Division, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

Adrienne Hunt & Katherine Littler

African Center of Excellence in Bioinformatics and Data Intensive Science, Infectious Diseases Institute, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

Daudi Jjingo

ISI Foundation, Turin, Italy

Daniela Paolotti

Department of Health Sciences and Technology, ETH Zurich, Zürich, Switzerland

Effy Vayena

Joint Centre for Bioethics, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada