- < Previous

Home > ETD > ETD_BACHELORS > 9418

Bachelor's Theses

The filipino online dating: filipino young adults' perception on online relationships.

Margarita Cielo Cambay Ma. Ana Pauline Salazar Quintos Russell Encarnacion Castellano Rafael Rosal Gonzales

Date of Publication

Document type.

Bachelor's Thesis

Degree Name

Bachelor of Arts Major in Psychology

College of Liberal Arts

Department/Unit

Thesis adviser.

Jaymee Abigail K. Pantaleon

Defense Panel Member

Filemon R. Cruz

Abstract/Summary

In the Philippines, the interdependent culture plays a role in how Filipinos perceive online dating and how it motivates them to use the medium. The researchers interviewed Filipino young adults, age 20-35 years old currently living in Metro Manila Philippines who tried online dating at least once. The researchers analyze the data through the requirements and guidelines of thematic analysis, a qualitative analysis that focuses on themes that come from analyzing, identifying and reporting patterns. The researchers discovered that online dating can help individuals meet potential romantic partners online, then transition into traditional dating. However, the researchers would like to note that not all online relationships can lead to successful long term relationships. It is found also that Filipino young adults are motivated to try online dating because of the influence of the experience of other individuals and they find online dating as an avenue not only in finding romantic relationships, but a convenient way to learn about other people and broaden their connections.

Abstract Format

Accession number, shelf location.

Archives, The Learning Commons, 12F, Henry Sy Sr. Hall

Physical Description

120 leaves : illustrations (some color) ; 29 cm.

Online dating--Philippines; Dating (Social customs)--Philippines

Recommended Citation

Cambay, M., Quintos, M. S., Castellano, R. E., & Gonzales, R. (2017). The Filipino online dating: Filipino young adults' perception on online relationships. Retrieved from https://animorepository.dlsu.edu.ph/etd_bachelors/9418

This document is currently not available here.

Since September 26, 2021

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

- Collections

- Disciplines

- Colleges and Units

- Submission Consent Form

- Animo Repository Policies

- Animo Repository Guide

- AnimoSearch

- DLSU Libraries

- DLSU Website

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

The Digital Cupid: The Impact of FilipinoCupid.com on the Attitudes of Filipino Women towards Online Dating

This study investigated the world of niche online dating in Barangay Arnedo, Bolinao, Pangasinan, Philippines. It explored the impact of FilipinoCupid.com on the attitudes of the female online daters towards online dating. The researchers interviewed Filipino women who have been using FilipinoCupid.com for at least one year. Fifteen (15) women aged 18 to 45 were interviewed about their online dating experiences. Data gathering was divided into two phases. The first phase began with the search for respondents through snowball sampling. To locate participants whose credibility could be verified and who we can contact again for verification and follow-up interviews, we started off by interviewing a key informant who is a user of FilipinoCupid.com and knows other women that date online. Questionnaires were also employed to collect respondents’ demographic data and to know their online dating habits and activity. The second phase of data gathering involved one-on-one interviews with the respondents. Data from the questionnaires were analyzed quantitatively. Data from the interviews, on the other hand, were analyzed qualitatively. The researchers used Marshall McLuhan’s theory of Media Ecology to explain the results of the study. This study proved that the online dating site FilipinoCupid.com has a significant impact on the attitudes of Filipino women towards online dating. Moreover, the study discovered the reasons and motivations of these women for engaging in online dating.

Related Papers

Symposium on Social Science 2020 "Rethinking the Social World in the 21st Century" Conference Proceeding

Mashita Phitaloka Fandia Purwaningtyas

The advancement of internet and digital media has brought new dynamics in the micro level of communication: interpersonal communication. Digital apps and social media platforms became integral parts in human's interaction pattern and fulfillment of needs, including the activity of looking for new friends and dating partners. Nowadays, online dating apps is one of youth's choices to build relationship. However, in Indonesia, the usage practice of online dating apps brings up certain problem surrounding the socio-cultural condition, in which the common view of the society in regards to morality and religion has clashed with modern influence brought by cultural transnationalism and globalization. At this level, the concept of self-disclosure and intimacy is significant in determining the interpersonal communication takes place in online dating platform. Thus, this research aims to analyze the interpersonal relationship built by online dating apps' users. The study area of this research covers the interpersonal communication studies, particularly in the relation between media psychology and the forming of digital culture among youth users. Data and research method used is virtual ethnography as the main method, with new ethnography as supporting method, in order to gain depth personal experience of online dating apps user. Expected findings of this research include why certain self-disclosure practice and meaning of intimacy developed by youth amidst the socio-cultural condition in Indonesia, in the usage practice of online dating apps. The significance of this research lies in the effort to approach media and communication issue in this digital era from the perspective of interpersonal human communication culturally and critically, notably the issue of online dating, self, and intimacy.

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences

MONIZA WAHEED / FBMK

International Journal of Business and Management

İlayda Tüter

One of the popular tools of twenty first century is with no doubt online dating apps. Researchers investigated and still investigating the possible reasons why people search for a partner, friend, friendzone, or other things on web. To have fun, enjoy conversation with a like -minded individual, sexual intercourse and marriage are one of those reasons why people go behind the screens to search for partner. While there are many more reasons underneath there are many risks pertaining online dating as well. Deceptive or fake self-presentation, online dating romance scam and cyber-crime are some of those risks. On the other hand, there are many people who find their partner on online dating apps and live happily with them. That is why, it is important to understand what people are looking for on the apps which are the reasons and intentions behind online dating apps. As a popular saying states apps do not have intentions, but people do have intentions and it drives them to get what they...

Plaridel: A Philippine Journal of Communication, Media, and Society

Jonalou S Labor

Mobile dating applications have become self-presentation spaces and stages among the youth. In the search for romance and sexual relationships, young Filipinos create and act out pre and co-constructed selves that enable them to find dating partners. Using the musings and experiences of 50 Filipino young adults who have been using dating apps to search for love or lust, the study found that created mobile/ online selves or faces reflect presentation strategies that include the show of sincerity, dramatic execution of the role, use of personal front, maintenance of control over the information, mystification, ideal-ization, and misrepresentation. The study concludes that self-presentations range from the authentic to the inauthentic portrayal of the self to advance motives and intents in the use of dating apps.

Almond Aguila

By late 2004, the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration determined that there were already as many as eight million Filipinos living temporarily or permanently overseas. That number is expected to rise in the years to come with close to a million nationals packing their bags annually for more lucrative careers and better living conditions abroad. The impact of this burgeoning migration on Philippine society can only be described as profound. We have reached a moment in the country’s history when practically every Filipino has a friend, family member or relative living abroad. These close ties are maintained over great distances through, among other tools, the Internet and cellular phone. In other words, Filipinos anywhere in the world keep in touch through Computer-Mediated Communication (CMC). This study presents a view of Filipino long-distance relationships (LDRs) among lovers, family members, married couples and friends whose interactions unavoidably entail the exchange of new ideas on gender roles, nationalism, family relations and dominant-subordinate relations that lead to cultural change. Theories used for this study were Marshall McLuhan’s Technological Determinism Theory, Stuart Hall’s Critical Cultural Theory and Irwin Altman and Dalmas Taylor’s Social Penetration Theory. Research methods applied were Online Forum (through the E-group), Online Survey (through E-mail), Focus Interview (both offline and online through E-mail and Chat), Observation and Participant Observation. The convenience and speed provided by CMC produced virtual closeness among most key informants and allowed them to have dynamic relationships despite the distance. Running parallel to McLuhan’s view that “the medium is the message,” these relationships underwent rapid development or deterioration through the use of CMC. Stability, closeness and tension reflected in their LDRs became extensions of the relationships they had prior to their separation. Though they actively used these tools based on conscious decision-making, CMC unavoidably contributed to their alternative concepts of Filipino family, friendship and romance amid increasing migration. The Internet and cellular phone have made it easier to accept the harsh reality that loved ones must live apart to survive. Meanwhile, the use of the online forum via e-group, online survey via e-mail and online focus interview via e-mail or Yahoo! Messenger chat were proven to be efficient and prolific research methods. These are highly recommended for use especially for distant key informants as well as research topics related to communication technology.

Meriç T Tuncez

An interdisciplinary book, Internet-Infused Romantic Interactions and Dating Practices, under contract with the publishing house of the Institute of Network Cultures, Amsterdam, aims to analyze intricacies of internet-infused romantic interactions and dating practices. The proposed collection aims to include contributions from communication scholars, social scientists, computer scientists, humanities scholars and design experts whose research and practice will shed light on the romantic interplay of affect, cognition, and behavior on the internet with special attention given to social media platforms such as Tinder, Facebook, Grinder, and OkCupid. The collection would aim to offer an array of international perspectives and methodological novelties and feature a volume of scientific research and practice from a multitude of disciplines and interdisciplinary outlooks. Quantitative as well as qualitative empirical research, theoretical essays and research reviews are all welcome. We aim to provide the readers with a theoretical and methodological assortment that is sensitive towards various approaches to the study of intimate relationships and romance as reflected in new media-from discourse analysis to visual network analysis; from in-depth interviews to experimental designs; from ethnographic observations to cross-sectional and longitudinal survey studies.

Paula Quinon

In this paper we evaluate the role that online dating plays in establishing successful and sustainable romantic relationships. We reject radically optimistic accounts (online dating enables creation of particularly successful relationships) and radically pessimistic accounts (online dating is destructive for relationships). In our argumentation in favor of a moderated liberal position we rely upon the conceptual framework of American pragmatism (James and Rorty) and in particular upon their analyses of " experience ". Rorty's account enables us to speak of interpersonal experience that does not involve physical contact and relies uniquely on the language. In such cases the language stops being a medium and becomes the experience itself. This is our main tool to speak of experience in the context of interpersonal relations fully mediated by internet. Building upon American pragmatism, we use the concept of an " extra-layer " of experience that covers internet-mediated interpersonal relations. We claim that the extra-layer fully integrates with other layers of human experience, and enables us to speak of " mixed reality ". We conclude that internet-mediated interactions-ubiquitous nowadays for a non negligible part of the society-shall be treated as an inevitable extensions of physical face-to-face experience. As such they become a natural part of our lives and as such cannot be proclaimed simply good or simply bad. In consequence, there is no one possible way in which online dating can be evaluated uniformly as a separate phenomenon. Keywords: #online dating #media theory #social media #mixed reality #experience #American pragmatism

Professor Adebayo D . Oluwole

Nigeria is one of the biggest and fastest growing telecom markets in Africa, attracting huge amounts of foreign investment, and is yet standing at very low levels of market penetration. The mobile sector, shared by four operators, has seen triple-digit growth rates every year since competition has been introduced. The transformation of Nigeria’s telecommunications landscape since the licensing of three GSM networks in 2001 and a fourth one in 2002 has been nothing short of astounding. The country continues to be one of the fastest growing markets in Africa with triple-digit growth rates almost every single year since 2001. It surpassed Egypt and Morocco in 2004 to become the continent’s second largest mobile market after South Africa (http://www.internetworldstats.com/af/ng.htm). And yet it has only reached about one quarter of its estimated ultimate market potential. Giving details of the current internet penetration in Nigeria, the Director General of National Information Technology Development Agency, Cleopas Angaye said that the Nigeria internet population witnessed tremendous growth with a boost from 2,418,679 users in 2005 to an estimated number of about 10 million users in 2008 and currently over 44 million internet users, thereby, positioning Nigeria as one of the fastest growing internet users in sub-Saharan Africa (thisdaylive, 2012). According to Bargh and McKenna (2004), the internet is but the latest in a series of technological advances that have changed the world in fundamental ways. One of these advances is cyber dating. In Nigeria today, young adults are adventurous and proactive in heterosexual encounters through the new technology of internet. Cyber dating is a channel for this exercise starting with online gossiping (Oluwole, 2009). Also, so many male adolescents are proving their masculinity (Oluwole, 2010) by foraging into the virtual space pretending as adults. Cyber dating is one of the several benefits of internet technology. However, as good as this innovation is, there are several conceptions, misconceptions and dangers of cyber dating. This is the focus of this paper.

RELATED PAPERS

Rafael Lira

Imanensi: Jurnal Ekonomi, Manajemen, dan Akuntansi Islam

Andi Chairil Furqan

Indra Gadhvi

Franca d'Agostini

Wajid Hussain

British Journal for Military History

Stuart Crawford

Trayectorias Universitarias

Raymond Marquina

Pasundan Social Science Development

abdillah amin

Darwin Artigas

laser.cs.umass.edu

George Avrunin

Turkish Journal of Parasitology

Fatih Karakaya

Andrea Cantarelli

Wahid syaifudin

Malaysian Journal of Syariah and Law

Amalina Tajudin

Biomedicines

Antonella Galli

Environmental Science & Technology

Staffan Sjöberg

Materials Sciences and Applications

Gisele Cristina Valle Iulianelli

Priyank Ghewari

hgkjhgh tghjfg

Turkiye Klinikleri Journal of Gastroenterohepatology

Nursen Bilgin Kadayıfçıoğlu

Davide Dal Bianco

hjhfggf hjgfdf

Indian Journal of Medical Specialities

David Arnulfo Miranda Mendoza

See More Documents Like This

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

Dating Apps and Their Sociodemographic and Psychosocial Correlates: A Systematic Review

The emergence and popularization of dating apps have changed the way people meet and interact with potential romantic and sexual partners. In parallel with the increased use of these applications, a remarkable scientific literature has developed. However, due to the recency of the phenomenon, some gaps in the existing research can be expected. Therefore, the objective of this study was to conduct a systematic review of the empirical research of the psychosocial content published in the last five years (2016–2020) on dating apps. A search was conducted in different databases, and we identified 502 articles in our initial search. After screening titles and abstracts and examining articles in detail, 70 studies were included in the review. The most relevant data (author/s and year, sample size and characteristics, methodology) and their findings were extracted from each study and grouped into four blocks: user dating apps characteristics, usage characteristics, motives for use, and benefits and risks of use. The limitations of the literature consulted are discussed, as well as the practical implications of the results obtained, highlighting the relevance of dating apps, which have become a tool widely used by millions of people around the world.

1. Introduction

In the last decade, the popularization of the Internet and the use of the smartphone and the emergence of real-time location-based dating apps (e.g., Tinder, Grindr) have transformed traditional pathways of socialization and promoted new ways of meeting and relating to potential romantic and/or sexual partners [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ].

It is difficult to know reliably how many users currently make use of dating apps, due to the secrecy of the developer companies. However, thanks to the information provided by different reports and studies, the magnitude of the phenomenon can be seen online. For example, the Statista Market Forecast [ 5 ] portal estimated that by the end of 2019, there were more than 200 million active users of dating apps worldwide. It has been noted that more than ten million people use Tinder daily, which has been downloaded more than a hundred million times worldwide [ 6 , 7 ]. In addition, studies conducted in different geographical and cultural contexts have shown that around 40% of single adults are looking for an online partner [ 8 ], or that around 25% of new couples met through this means [ 9 ].

Some theoretical reviews related to users and uses of dating apps have been published, although they have focused on specific groups, such as men who have sex with men (MSM [ 10 , 11 ]) or on certain risks, such as aggression and abuse through apps [ 12 ].

Anzani et al. [ 1 ] conducted a review of the literature on the use of apps to find a sexual partner, in which they focused on users’ sociodemographic characteristics, usage patterns, and the transition from online to offline contact. However, this is not a systematic review of the results of studies published up to that point and it leaves out some relevant aspects that have received considerable research attention, such as the reasons for use of dating apps, or their associated advantages and risks.

Thus, we find a recent and changing object of study, which has achieved great social relevance in recent years and whose impact on research has not been adequately studied and evaluated so far. Therefore, the objective of this study was to conduct a systematic review of the empirical research of psychosocial content published in the last five years (2016–2020) on dating apps. By doing so, we intend to assess the state of the literature in terms of several relevant aspects (i.e., users’ profile, uses and motives for use, advantages, and associated risks), pointing out some limitations and posing possible future lines of research. Practical implications will be highlighted.

2. Materials and Methods

The systematic literature review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [ 13 , 14 ], and following the recommendations of Gough et al. [ 15 ]. However, it should be noted that, as the objective of this study was to provide a state of the art view of the published literature on dating apps in the last five years and without statistical data processing, there are several principles included in the PRISMA that could not be met (e.g., summary measures, planned methods of analysis, additional analysis, risk of bias within studies). However, following the advice of the developers of these guidelines concerning the specific nature of systematic reviews, the procedure followed has been described in a clear, precise, and replicable manner [ 13 ].

2.1. Literature Search and Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

We examined the databases of the Web of Science, Scopus, and Medline, as well as PsycInfo and Psycarticle and Google Scholar, between 1 March and 6 April 2020. In all the databases consulted, we limited the search to documents from the last five years (2016–2020) and used general search terms, such as “dating apps” and “online dating” (linking the latter with “apps”), in addition to the names of some of the most popular and frequently used dating apps worldwide, such as “tinder”, “grindr”, and “momo”, to identify articles that met the inclusion criteria (see below).

The selection criteria in this systematic review were established and agreed on by the two authors of this study. The database search was carried out by one researcher. In case of doubt about whether or not a study should be included in the review, consultation occurred and the decision was agreed upon by the two researchers.

Four-hundred and ninety-three results were located, to which were added 15 documents that were found through other resources (e.g., social networks, e-mail alerts, newspapers, the web). After these documents were reviewed and the duplicates removed, a total of 502 records remained, as shown by the flowchart presented in Figure 1 . At that time, the following inclusion criteria were applied: (1) empirical, quantitative or qualitative articles; (2) published on paper or in electronic format (including “online first”) between 2016 and 2020 (we decided to include articles published since 2016 after finding that the previous empirical literature in databases on dating apps from a psychosocial point of view was not very large; in fact, the earliest studies of Tinder included in Scopus dated back to 2016; (3) to be written in English or Spanish; and (4) with psychosocial content. No theoretical reviews, case studies/ethnography, user profile content analyses, institutional reports, conference presentations, proceeding papers, etc., were taken into account.

Flowchart of the systematic review process.

Thus, the process of refining the results, which can be viewed graphically in Figure 1 , was as follows. Of the initial 502 results, the following exclusion criteria were applied: (1) pre-2016 documents (96 records excluded); (2) documents that either did not refer to dating apps or did so from a technological approach (identified through title and abstract; 239 records excluded); (3) published in a language other than English or Spanish (10 records excluded); (4) institutional reports, or analysis of the results of such reports (six records excluded); (5) proceeding papers (six records excluded); (6) systematic reviews and theoretical reflections (26 records excluded); (7) case studies/ethnography (nine records excluded); (8) non-empirical studies of a sociological nature (20 records excluded); (9) analysis of user profile content and campaigns on dating apps and other social networks (e.g., Instagram; nine records excluded); and (10) studies with confusing methodology, which did not explain the methodology followed, the instruments used, and/or the characteristics of the participants (11 records excluded). This process led to a final sample of 70 empirical studies (55 quantitative studies, 11 qualitative studies, and 4 mixed studies), as shown by the flowchart presented in Figure 1 .

2.2. Data Collection Process and Data Items

One review author extracted the data from the included studies, and the second author checked the extracted data. Information was extracted from each included study of: (1) author/s and year; (2) sample size and characteristics; (3) methodology used; (4) main findings.

Table 1 shows the information extracted from each of the articles included in this systematic review. The main findings drawn from these studies are also presented below, distributed in different sections.

Characteristics of reviewed studies.

3.1. Characteristics of Reviewed Studies

First, the characteristics of the 70 articles included in the systematic review were analyzed. An annual increase in production can be seen, with 2019 being the most productive year, with 31.4% ( n = 22) of included articles. More articles (11) were published in the first three months of 2020 than in 2016. It is curious to note, on the other hand, how, in the titles of the articles, some similar formulas were repeated, even the same articles (e.g., Love me Tinder), playing with the swipe characteristic of this type of application (e.g., Swiping more, Swiping right, Swiping me).

As for the methodology used, the first aspect to note is that all the localized studies were cross-sectional and there were no longitudinal ones. As mentioned above, 80% ( n = 55) of the studies were quantitative, especially through online survey ( n = 49; 70%). 15.7% ( n = 11) used a qualitative methodology, either through semi-structured interviews or focus groups. And 5.7% ( n = 4) used a mixed methodology, both through surveys and interviews. It is worth noting the increasing use of tools such as Amazon Mechanical Turk ( n = 9, 12.9%) or Qualtrics ( n = 8, 11.4%) for the selection of participants and data collection.

The studies included in the review were conducted in different geographical and cultural contexts. More than one in five investigations was conducted in the United States (22.8%, n = 16), to which the two studies carried out in Canada can be added. Concerning other contexts, 20% ( n = 14) of the included studies was carried out in different European countries (e.g., Belgium, The Netherlands, UK, Spain), whereas 15.7% ( n = 11) was carried out in China, and 8.6% ( n = 6) in other countries (e.g., Thailand, Australia). However, 21.4% ( n = 15) of the investigations did not specify the context they were studying.

Finally, 57.1% ( n = 40) of the studies included in the systematic review asked about dating apps use, without specifying which one. The results of these studies showed that Tinder was the most used dating app among heterosexual people and Grindr among sexual minorities. Furthermore, 35% ( n = 25) of the studies included in the review focused on the use of Tinder, while 5.7% ( n = 4) focused on Grindr.

3.2. Characteristics of Dating App Users

It is difficult to find studies that offer an overall user profile of dating apps, as many of them have focused on specific populations or groups. However, based on the information collected in the studies included in this review, some features of the users of these applications may be highlighted.

Gender. Traditionally, it has been claimed that men use dating apps more than women and that they engage in more casual sex relationships through apps [ 3 ]. In fact, some authors, such as Weiser et al. [ 75 ], collected data that indicated that 60% of the users of these applications were male and 40% were female. Some current studies endorse that being male predicts the use of dating apps [ 23 ], but research has also been published in recent years that has shown no differences in the proportion of male and female users [ 59 , 68 ].

To explain these similar prevalence rates, some authors, such as Chan [ 27 ], have proposed a feminist perspective, stating that women use dating apps to gain greater control over their relationships and sexuality, thus countering structural gender inequality. On the other hand, other authors have referred to the perpetuation of traditional masculinity and femmephobic language in these applications [ 28 , 53 ].

Age. Specific studies have been conducted on people of different ages: adolescents [ 49 ], young people (e.g., [ 21 , 23 , 71 ]), and middle-aged and older people [ 58 ]. The most studied group has been young people between 18 and 30 years old, mainly university students, and some authors have concluded that the age subgroup with a higher prevalence of use of dating apps is between 24 and 30 years of age [ 44 , 59 ].

Sexual orientation. This is a fundamental variable in research on dating apps. In recent years, especially after the success of Tinder, the use of these applications by heterosexuals, both men and women, has increased, which has affected the increase of research on this group [ 3 , 59 ]. However, the most studied group with the highest prevalence rates of dating apps use is that of men from sexual minorities [ 18 , 40 ]. There is considerable literature on this collective, both among adolescents [ 49 ], young people [ 18 ], and older people [ 58 ], in different geographical contexts and both in urban and rural areas [ 24 , 36 , 43 , 79 ]. Moreover, being a member of a sexual minority, especially among men, seems to be a good predictor of the use of dating apps [ 23 ].

For these people, being able to communicate online can be particularly valuable, especially for those who may have trouble expressing their sexual orientation and/or finding a partner [ 3 , 80 ]. There is much less research on non-heterosexual women and this focuses precisely on their need to reaffirm their own identity and discourse, against the traditional values of hetero-patriate societies [ 35 , 69 ].

Relationship status. It has traditionally been argued that the prevalence of the use of dating apps was much higher among singles than among those with a partner [ 72 ]. This remains the case, as some studies have shown that being single was the most powerful sociodemographic predictor of using these applications [ 23 ]. However, several investigations have concluded that there is a remarkable percentage of users, between 10 and 29%, who have a partner [ 4 , 17 , 72 ]. From what has been studied, usually aimed at evaluating infidelity [ 17 , 75 ], the reasons for using Tinder are very different depending on the relational state, and the users of this app who had a partner had had more sexual and romantic partners than the singles who used it [ 72 ].

Other sociodemographic variables. Some studies, such as the one of Shapiro et al. [ 64 ], have found a direct relationship between the level of education and the use of dating apps. However, most studies that contemplated this variable have focused on university students (see, for example [ 21 , 23 , 31 , 38 ]), so there may be a bias in the interpretation of their results. The findings of Shapiro et al. [ 64 ] presented a paradox: while they found a direct link between Tinder use and educational level, they also found that those who did not use any app achieved better grades. Another striking result about the educational level is that of the study of Neyt et al. [ 9 ] about their users’ characteristics and those that are sought in potential partners through the apps. These authors found a heterogeneous effect of educational level by gender: whereas women preferred a potential male partner with a high educational level, this hypothesis was not refuted in men, who preferred female partners with lower educational levels.

Other variables evaluated in the literature on dating apps are place of residence or income level. As for the former, app users tend to live in urban contexts, so studies are usually performed in large cities (e.g., [ 11 , 28 , 45 ]), although it is true that in recent years studies are beginning to be seen in rural contexts to know the reality of the people who live there [ 43 ]. It has also been shown that dating app users have a higher income level than non-users, although this can be understood as a feature associated with young people with high educational levels. However, it seems that the use of these applications is present in all social layers, as it has been documented even among homeless youth in the United States [ 66 ].

Personality and other psychosocial variables. The literature that relates the use of dating apps to different psychosocial variables is increasingly extensive and diverse. The most evaluated variable concerning the use of these applications is self-esteem, although the results are inconclusive. It seems established that self-esteem is the most important psychological predictor of using dating apps [ 6 , 8 , 59 ]. But some authors, such as Orosz et al. [ 55 ], warn that the meaning of that relationship is unclear: apps can function both as a resource for and a booster of self-esteem (e.g., having a lot of matches) or to decrease it (e.g., lack of matches, ignorance of usage patterns).

The relationship between dating app use and attachment has also been studied. Chin et al. [ 29 ] concluded that people with a more anxious attachment orientation and those with a less avoidant orientation were more likely to use these apps.

Sociosexuality is another important variable concerning the use of dating apps. It has been found that users of these applications tended to have a less restrictive sociosexuality, especially those who used them to have casual sex [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 21 ].

Finally, the most studied approach in this field is the one that relates the use of dating apps with certain personality traits, both from the Big Five and from the dark personality model. As for the Big Five model, Castro et al. [ 23 ] found that the only trait that allowed the prediction of the current use of these applications was open-mindedness. Other studies looked at the use of apps, these personality traits, and relational status. Thus, Timmermans and De Caluwé [ 71 ] found that single users of Tinder were more outgoing and open to new experiences than non-user singles, who scored higher in conscientiousness. For their part, Timmermans et al. [ 72 ] concluded that Tinder users who had a partner scored lower in agreeableness and conscientiousness and higher in neuroticism than people with partners who did not use Tinder.

The dark personality, on the other hand, has been used to predict the different reasons for using dating apps [ 48 ], as well as certain antisocial behaviors in Tinder [ 6 , 51 ]. As for the differences in dark personality traits between users and non-users of dating apps, the results are inconclusive. A study was localized that highlighted the relevance of psychopathy [ 3 ] whereas another study found no predictive power as a global indicator of dark personality [ 23 ].

3.3. Characteristics of Dating App Use

It is very difficult to know not only the actual number of users of dating apps in any country in the world but also the prevalence of use. This varies depending on the collectives studied and the sampling techniques used. Given this caveat, the results of some studies do allow an idea of the proportion of people using these apps. It has been found to vary between the 12.7% found by Castro et al. [ 23 ] and the 60% found by LeFebvre [ 44 ]. Most common, however, is to find a participant prevalence of between 40–50% [ 3 , 4 , 39 , 62 , 64 ], being slightly higher among men from sexual minorities [ 18 , 50 ].

The study of Botnen et al. [ 21 ] among Norwegian university students concluded that about half of the participants appeared to be a user of dating apps, past or present. But only one-fifth were current users, a result similar to those found by Castro et al. [ 23 ] among Spanish university students. The most widely used, and therefore the most examined, apps in the studies are Tinder and Grindr. The first is the most popular among heterosexuals, and the second among men of sexual minorities [ 3 , 18 , 36 , 70 ].

Findings from existing research on the characteristics of the use of dating apps can be divided among those referring to before (e.g., profiling), during (e.g., use), and after (e.g., offline behavior with other app users). Regarding before , the studies focus on users’ profile-building and self-presentation more among men of sexual minorities [ 52 , 77 ]. Ward [ 74 ] highlighted the importance of the process of choosing the profile picture in applications that are based on physical appearance. Like Ranzini and Lutz [ 59 ], Ward [ 74 ] mentions the differences between the “real self” and the “ideal self” created in dating apps, where one should try to maintain a balance between one and the other. Self-esteem plays a fundamental role in this process, as it has been shown that higher self-esteem encourages real self-presentation [ 59 ].

Most of the studies that analyze the use of dating apps focus on during , i.e. on how applications are used. As for the frequency of use and the connection time, Chin et al. [ 29 ] found that Tinder users opened the app up to 11 times a day, investing up to 90 minutes per day. Strubel and Petrie [ 67 ] found that 23% of Tinder users opened the app two to three times a day, and 14% did so once a day. Meanwhile, Sumter and Vandenbosch [ 3 ] concluded that 23% of the users opened Tinder daily.

It seems that the frequency and intensity of use, in addition to the way users behave on dating apps, vary depending on sexual orientation and sex. Members of sexual minorities, especially men, use these applications more times per day and for longer times [ 18 ]. As for sex, different patterns of behavior have been observed both in men and women, as the study of Timmermans and Courtois [ 4 ] shows. Men use apps more often and more intensely, but women use them more selectively and effectively. They accumulate more matches than men and do so much faster, allowing them to choose and have a greater sense of control. Therefore, it is concluded that the number of swipes and likes of app users does not guarantee a high number of matches in Tinder [ 4 ].

Some authors are alert to various behaviors observed in dating apps which, in some cases, may be negative for the user. For example, Yeo and Fung [ 77 ] mention the fast and hasty way of acting in apps, which is incongruous with cultural norms for the formation of friendships and committed relationships and ends up frustrating those who seek more lasting relationships. Parisi and Comunello [ 57 ] highlighted a key to the use of apps and a paradox. They referred to relational homophilia, that is, the tendency to be attracted to people similar to oneself. But, at the same time, this occurs in a context that increases the diversity of intimate interactions, thus expanding pre-existing networks. Finally, Licoppe [ 45 ] concluded that users of Grindr and Tinder present almost opposite types of communication and interaction. In Grindr, quick conversations seem to take precedence, aimed at organizing immediate sexual encounters, whereas, in Tinder, there are longer conversations and more exchange of information.

The latest group of studies focuses on offline behavior with contacts made through dating apps. Differences have been observed in the prevalence of encounters with other app users, possibly related to participants’ sociodemographic characteristics. Whereas Strugo and Muise [ 2 ], and Macapagal et al. [ 49 ] found that between 60 and 70% of their participants had had an encounter with another person known through these applications, in other studies this is less common, with prevalence being less than 50% [ 3 , 4 , 62 ]. In fact, Griffin et al. [ 39 ] stated that in-person encounters were relatively rare among users of dating apps.

There are also differences in the types of relationships that arose after offline encounters with other users. Strugo and Muise [ 2 ] concluded that 33% of participants had found a romantic partner and that 52% had had casual sex with at least one partner met through an app. Timmermans and Courtois [ 4 ] found that one-third of the offline encounters ended in casual sex and one-fourth in a committed relationship. Sumter and Vandenbosch [ 3 ], for their part, concluded that 18.6% of the participants had had sex with another person they had met on Tinder. And finally, the participants in the study of Timmermans and De Caluwé [ 71 ] indicated that: (1) they had met face-to-face with an average of 4.25 people whom they had met on Tinder; (2) they had had one romantic relationship with people met on Tinder; (3) they had had casual sex with an average of 1.57 people met on Tinder; and (4) they had become friends with an average of 2.19 people met on Tinder.

3.4. Motives for Dating App Use

There is a stereotype that dating apps are used only, or above all, to look for casual sex [ 44 ]. In fact, these applications have been accused of generating a hookup culture, associated with superficiality and sexual frivolity [ 2 ]. However, this is not the case. In the last five years, a large body of literature has been generated on the reasons why people use dating apps, especially Tinder, and the conclusion is unanimous: apps serve multiple purposes, among which casual sex is only one [ 1 , 4 , 44 ]. It has been found that up to 70% of the app users participating in a study [ 18 ] indicated that their goal when using it was not sex-seeking.

An evolution of research interest can be traced regarding the reasons that guide people to use dating apps [ 55 ]. The first classification of reasons for using Tinder was published by Ranzini and Lutz [ 59 ], who adapted a previous scale, designed for Grindr, composed of six motives: hooking up/sex (finding sexual partners), friendship (building a social network), relationship (finding a romantic partner), traveling (having dates in different places), self-validation (self-improvement), and entertainment (satisfying social curiosity). They found that the reason given by most users was those of entertainment, followed by those of self-validation and traveling, with the search for sex occupying fourth place in importance. However, the adaptation of this scale did not have adequate psychometric properties and it has not been reused.

Subsequently, Sumter et al. [ 68 ] generated a new classification of reasons to use Tinder, later refined by Sumter and Vandenbosch [ 3 ]. They proposed six reasons for use, both relational (love, casual sex), intrapersonal (ease of communication, self-worth validation), and entertainment (the thrill of excitement, trendiness). The motivation most indicated by the participants was that of love, and the authors concluded that Tinder is used: (1) to find love and/or sex; (2) because it is easy to communicate; (3) to feel better about oneself; and (4) because it’s fun and exciting.

At the same time, Timmermans and De Caluwé [ 70 ] developed the Tinder Motives Scale, which evaluates up to 13 reasons for using Tinder. The reasons, sorted by the scores obtained, were: to pass time/entertainment, curiosity, socializing, relationship-seeking, social approval, distraction, flirting/social skills, sexual orientation, peer pressure, traveling, sexual experience, ex, and belongingness. So far, the most recently published classification of reasons is that of Orosz et al. [ 55 ], who in the Tinder Use Motivations Scale proposed four groups of reasons: boredom (individual reasons to use Tinder to overcome boredom), self-esteem (use of Tinder to improve self-esteem), sex (use of Tinder to satisfy sexual need) and love (use of Tinder to find love). As in the previous scales, the reasons of seeking sex did not score higher on this scale, so it can be concluded that dating apps are not mainly used for this reason.

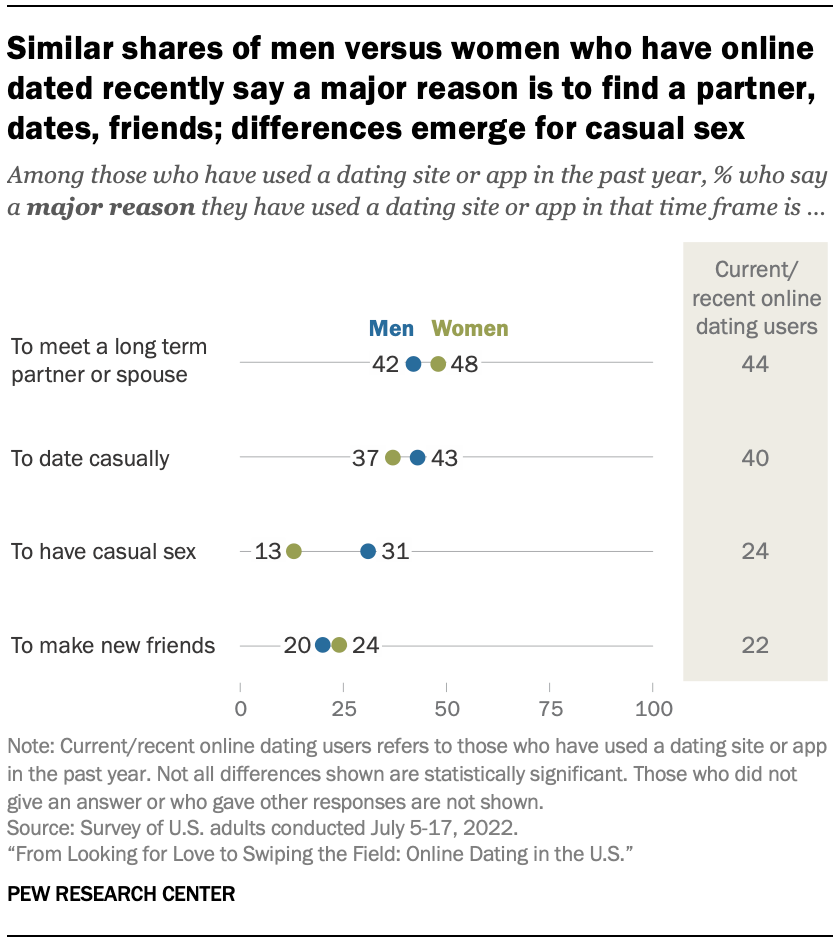

The existing literature indicates that reasons for the use of dating apps may vary depending on different sociodemographic and personality variables [ 1 ]. As for sex, Ranzini and Lutz [ 59 ] found that women used Tinder more for friendship and self-validation, whereas men used it more to seek sex and relationships. Sumter et al. [ 68 ] found something similar: men scored higher than women in casual sex motivation and also in the motives of ease of communication and thrill of excitement.

With regard to age, Ward [ 74 ] concluded that motivations change over time and Sumter et al. [ 68 ] found a direct association with the motives of love, casual sex, and ease of communication. In terms of sexual orientation, it has become commoner for people from sexual minorities, especially men, than for heterosexual participants to use these applications much more in the search for casual sex [ 18 ].

Finally, other studies have concluded that personality guides the motivations for the use of dating apps [ 3 , 72 ]. A line of research initiated in recent years links dark personality traits to the reasons for using Tinder. In this investigation, Lyons et al. [ 48 ] found that people who score high in Machiavellianism and psychopathy offer more reasons for use (e.g., get casual sex, acquiring social or flirting skills).

3.5. Benefits and Risks of Using Dating Apps

In the latter section, the benefits and advantages of the use of dating apps are analyzed. There is also an extensive literature on the risks associated with use. Many studies indicate that dating apps have opened a new horizon in how to meet potential partners, allowing access to many [ 3 , 6 , 8 ], which may be even more positive for certain individuals and groups who have been silenced or marginalized, such as some men from sexual minorities [ 80 ]. It has also been emphasized that these applications are a non-intimidating way to start connecting, they are flexible and free, and require less time and effort than other traditional means of communication [ 1 , 55 ].

On the other hand, the advantages of apps based on the technology they use and the possibilities they pose to users have been highlighted. Ranzini and Lutz [ 59 ] underlined four aspects. First is the portability of smartphones and tablets, which allows the use of apps in any location, both private and public. Second is availability, as their operation increases the spontaneity and frequency of use of the apps, and this, in turn, allows a quick face-to-face encounter, turning online interactions into offline relationships [ 70 , 77 ]. Thirdly is locatability, as dating apps allow matches, messages, and encounters with other users who are geographically close [ 77 ]. Finally is multimediality, the relevance of the visual, closely related to physical appearance, which results in two channels of communication (photos and messages) and the possibility of linking the profile with that of other social networks, such as Facebook and Instagram [ 4 ].

There is also considerable literature focused on the potential risks associated with using these applications. The topics covered in the studies can be grouped into four blocks, having in common the negative consequences that these apps can generate in users’ mental, relational, and sexual health. The first block focuses on the configuration and use of the applications themselves. Their emergence and popularization have been so rapid that apps pose risks associated with security, intimacy, and privacy [ 16 , 20 ]. This can lead to more insecure contacts, especially among women, and fears related to the ease of localization and the inclusion of personal data in apps [ 39 ]. Some authors highlight the paradox that many users suffer: they have more chances of contact than ever before, but at the same time this makes them more vulnerable [ 26 , 80 ].

This block can also include studies on the problematic use of apps, which can affect the daily lives of users [ 34 , 56 ], and research that focuses on the possible negative psychological effects of their use, as a link has been shown between using dating apps and loneliness, dissatisfaction with life, and feeling excluded from the world [ 24 , 34 , 78 ].

The second block of studies on the risks associated with dating apps refers to discrimination and aggression. Some authors, such as Conner [ 81 ] and Lauckner et al. [ 43 ], have argued that technology, instead of reducing certain abusive cultural practices associated with deception, discrimination, or abuse (e.g., about body types, weight, age, rural environments, racism, HIV stigma), has accentuated them, and this can affect users’ mental health. Moreover, certain antisocial behaviors in apps, such as trolling [ 6 , 51 ], have been studied, and a relationship has been found between being a user of these applications and suffering some episode of sexual victimization, both in childhood and adulthood [ 30 ].

The following block refers to the risks of dating app use regarding diet and body image. These applications, focusing on appearance and physical attractiveness, can promote excessive concerns about body image, as well as various negative consequences associated with it (e.g., unhealthy weight management behaviors, low satisfaction and high shame about the body, more comparisons with appearance [ 22 , 36 , 67 , 73 ]). These risks have been more closely associated with men than with women [ 61 ], perhaps because of the standards of physical attractiveness prevalent among men of sexual minorities, which have been the most studied collective.

The last block of studies on the risks of dating app use focuses on their relationship with risky sexual behaviors. This is probably the most studied topic in different populations (e.g., sexual minority men, heterosexual people). The use of these applications can contribute to a greater performance of risky sexual behaviors, which results in a higher prevalence of sexually transmitted illnesses (STIs). However, the results of the studies analyzed are inconclusive [ 40 ].

On the one hand, some studies find a relationship between being a user of dating apps and performing more risky sexual behaviors (e.g., having more sexual partners, less condom use, more relationships under the effects of alcohol and other drugs), both among men from sexual minorities [ 19 ] and among heterosexual individuals [ 32 , 41 , 62 ]. On the other hand, some research has found that, although app users perform more risky behaviors, especially having more partners, they also engage in more prevention behaviors (e.g., more sex counseling, more HIV tests, more treatment) and they do not use the condoms less than non-users [ 18 , 50 , 64 , 79 ]. Studies such as that of Luo et al. [ 46 ] and that of Wu [ 76 ] also found greater use of condoms among app users than among non-users.

Finally, some studies make relevant appraisals of this topic. For example, Green et al. [ 38 ] concluded that risky sexual behaviors are more likely to be performed when sex is performed with a person met through a dating app with whom some common connection was made (e.g., shared friends in Facebook or Instagram). This is because these users tend to avoid discussing issues related to prevention, either because they treat that person more familiarly, or for fear of possible gossip. Finally, Hahn et al. [ 40 ] found that, among men from sexual minorities, the contact time prior to meeting in person was associated with greater prevention. The less time between the conversation and the first encounter, the more likely the performance of risky behaviors.

4. Discussion

In a very few years, dating apps have revolutionized the way of meeting and interacting with potential partners. In parallel with the popularization of these applications, a large body of knowledge has been generated which, however, has not been collected in any systematic review. Given the social relevance that this phenomenon has reached, we performed this study to gather and analyze the main findings of empirical research on psychosocial content published in the last five years (2016–2020) on dating apps.

Seventy studies were located and analyzed, after applying stringent inclusion criteria that, for various reasons, left out a large number of investigations. Thus, it has been found that the literature on the subject is extensive and varied. Studies of different types and methodologies have been published, in very diverse contexts, on very varied populations and focusing on different aspects, some general and others very specific. Therefore, the first and main conclusion of this study is that the phenomenon of dating apps is transversal, and very present in the daily lives of millions of people around the world.

This transversality has been evident in the analysis of the characteristics of the users of dating apps. Apps have been found to be used, regardless of sex [ 59 , 68 ], age [ 49 , 58 , 71 ], sexual orientation [ 3 , 59 ], relational status [ 72 ], educational and income level [ 9 , 66 ], or personality traits [ 23 , 48 , 72 ].

Another conclusion that can be drawn from this analysis is that there are many preconceived ideas and stereotypes about dating apps, both at the research and social level, which are supported by the literature, but with nuances. For example, although the stereotype says that apps are mostly used by men, studies have concluded that women use them in a similar proportion, and more effectively [ 4 ]. The same goes for sexual orientation or relational status; the stereotype says that dating apps are mostly used by men of sexual minorities and singles [ 1 ], but some apps (e.g., Tinder) are used more by heterosexual people [ 3 , 59 ] and there is a remarkable proportion of people with a partner who use these apps [ 4 , 17 ].

A third conclusion of the review of the studies is that to know and be able to foresee the possible consequences of the use of dating apps, how and why they are used are particularly relevant. For this reason, both the use and the motives for use of these applications have been analyzed, confirming the enormous relevance of different psychosocial processes and variables (e.g., self-esteem, communication, and interaction processes), both before (profiling), during (use), and after (off-line encounters) of the use of dating apps.

However, in this section, what stands out most is the difficulty in estimating the prevalence of the use of dating apps. Very disparate prevalence have been found not only because of the possible differences between places and groups (see, for example [ 18 , 23 , 44 , 64 ]), but also because of the use of different sampling and information collection procedures, which in some cases, over-represent app users. All this hinders the characterization and assessment of the phenomenon of dating apps, as well as the work of the researchers. After selecting the group to be studied, it would be more appropriate to collect information from a representative sample, without conditioning or directing the study toward users, as this may inflate the prevalence rates.

The study of motives for the use of dating apps may contain the strongest findings of all those appraised in this review. Here, once again, a preconceived idea has been refuted, not only among researchers but across society. Since their appearance, there is a stereotype that dating apps are mostly used for casual sex [ 2 , 44 ]. However, studies constantly and consistently show that this is not the case. The classifications of the reasons analyzed for their use have concluded that people use dating apps for a variety of reasons, such as to entertain themselves, out of curiosity, to socialize, and to seek relationships, both sexual and romantic [ 3 , 59 , 68 , 70 ]. Thus, these apps should not be seen as merely for casual sex, but as much more [ 68 ].

Understanding the reasons for using dating apps provides a necessary starting point for research questions regarding the positive and negative effects of use [ 70 ]. Thus, the former result block reflected findings on the advantages and risks associated with using dating apps. In this topic, there may be a paradox in the sense that something that is an advantage (e.g., access to a multitude of potential partners, facilitates meeting people) turns into a drawback (e.g., loss of intimacy and privacy). Research on the benefits of using dating apps is relatively scarce, but it has stressed that these tools are making life and relationships easier for many people worldwide [ 6 , 80 ].

The literature on the risks associated with using dating apps is much broader, perhaps explaining the negative social vision of them that still exists nowadays. These risks have highlighted body image, aggression, and the performance of risky sexual behaviors. Apps represent a contemporary environment that, based on appearance and physical attractiveness, is associated with several negative pressures and perceptions about the body, which can have detrimental consequences for the physical and mental health of the individual [ 67 ]. As for assaults, there is a growing literature alerting us to the increasing amount of sexual harassment and abuse related to dating apps, especially in more vulnerable groups, such as women, or among people of sexual minorities (e.g., [ 12 , 82 ]).

Finally, there is considerable research that has analyzed the relationship between the use of dating apps and risky sexual behaviors, in different groups and with inconclusive results, as has already been shown [ 40 , 46 , 76 ]. In any case, as dating apps favor contact and interaction between potential partners, and given that a remarkable percentage of sexual contacts are unprotected [ 10 , 83 ], further research should be carried out on this topic.

Limitations and Future Directions

The meteoric appearance and popularization of dating apps have generated high interest in researchers around the world in knowing how they work, the profile of users, and the psychosocial processes involved. However, due to the recency of the phenomenon, there are many gaps in the current literature on these applications. That is why, in general terms, more research is needed to improve the understanding of all the elements involved in the functioning of dating apps.

It is strange to note that many studies have been conducted focusing on very specific aspects related to apps while other central aspects, such as the profile of users, had not yet been consolidated. Thus, it is advisable to improve the understanding of the sociodemographic and personality characteristics of those who use dating apps, to assess possible differences with those who do not use them. Attention should also be paid to certain groups that have been poorly studied (e.g., women from sexual minorities), as research has routinely focused on men and heterosexual people.

Similarly, limitations in understanding the actual data of prevalence of use have been highlighted, due to the over-representation of the number of users of dating apps seen in some studies. Therefore, it would be appropriate to perform studies in which the app user would not be prioritized, to know the actual use of these tools among the population at large. Although further studies must continue to be carried out on the risks of using these applications (e.g., risky sexual behaviors), it is also important to highlight the positive sexual and relational consequences of their use, in order to try to mitigate the negative social vision that still exists about dating app users. Last but not least, as all the studies consulted and included in this systematic review were cross-sectional, longitudinal studies are necessary which can evaluate the evolution of dating apps, their users and their uses, motives, and consequences.

The main limitations of this systematic review concern the enormous amount of information currently existing on dating apps. Despite having applied rigorous exclusion criteria, limiting the studies to the 2016–2020 period, and that the final sample was of 70 studies, much information has been analyzed and a significant number of studies and findings that may be relevant were left out. In future, the theoretical reviews that are made will have to be more specific, focused on certain groups and/or problems.

Another limitation—in this case, methodological, to do with the characteristics of the topic analyzed and the studies included—is that not all the criteria of the PRISMA guidelines were followed [ 13 , 14 ]. We intended to make known the state of the art in a subject well-studied in recent years, and to gather the existing literature without statistical treatment of the data. Therefore, there are certain criteria of PRISMA (e.g., summary measures, planned methods of analysis, additional analysis, risk of bias within studies) that cannot be satisfied.

However, as stated in the Method section, the developers of the PRISMA guidelines themselves have stated that some systematic reviews are of a different nature and that not all of them can meet these criteria. Thus, their main recommendation, to present methods with adequate clarity and transparency to enable readers to critically judge the available evidence and replicate or update the research, has been followed [ 13 ].

Finally, as the initial search in the different databases was carried by only one of the authors, some bias could have been introduced. However, as previously noted, with any doubt about the inclusion of any study, the final decision was agreed between both authors, so we expect this possible bias to be small.

5. Conclusions

Dating apps have come to stay and constitute an unstoppable social phenomenon, as evidenced by the usage and published literature on the subject over the past five years. These apps have become a new way to meet and interact with potential partners, changing the rules of the game and romantic and sexual relationships for millions of people all over the world. Thus, it is important to understand them and integrate them into the relational and sexual life of users [ 76 ].

The findings of this systematic review have relevant implications for various groups (i.e., researchers, clinicians, health prevention professionals, users). Detailed information has been provided on the characteristics of users and the use of dating apps, the most common reasons for using them, and the benefits and risks associated with them. This can guide researchers to see what has been done and how it has been done and to design future research.

Second, there are implications for clinicians and health prevention and health professionals, concerning mental, relational, and sexual health. These individuals will have a starting point for designing more effective information and educational programs. These programs could harness the potential of the apps themselves and be integrated into them, as suggested by some authors [ 42 , 84 ].

Finally and unavoidably, knowledge about the phenomenon of dating apps collected in this systematic review can have positive implications for users, who may have at their disposal the necessary tools to make a healthy and responsible use of these applications, maximizing their advantages and reducing the risks posed by this new form of communication present in the daily life of so many people.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Á.C. and J.R.B.; methodology, Á.C. and J.R.B.; formal analysis, Á.C. and J.R.B.; investigation, Á.C. and J.R.B.; resources, Á.C. and J.R.B.; data curation, Á.C. and J.R.B.; writing—original draft preparation, Á.C.; writing—review and editing, J.R.B. and Á.C.; project administration, Á.C.; funding acquisition, Á.C. and J.R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This research was funded by: (1) Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities, Government of Spain (PGC2018-097086-A-I00); and (2) Government of Aragón (Group S31_20D). Department of Innovation, Research and University and FEDER 2014-2020, “Building Europe from Aragón”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 04 March 2020

Swipe-based dating applications use and its association with mental health outcomes: a cross-sectional study

- Nicol Holtzhausen 1 ,

- Keersten Fitzgerald 1 ,

- Ishaan Thakur 1 ,

- Jack Ashley 1 ,

- Margaret Rolfe 2 &

- Sabrina Winona Pit ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2410-0703 1 , 2

BMC Psychology volume 8 , Article number: 22 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

53k Accesses

26 Citations

256 Altmetric

Metrics details

Swipe-Based Dating Applications (SBDAs) function similarly to other social media and online dating platforms but have the unique feature of “swiping” the screen to either like or dislike another user’s profile. There is a lack of research into the relationship between SBDAs and mental health outcomes.

The aim of this study was to study whether adult SBDA users report higher levels of psychological distress, anxiety, depression, and lower self-esteem, compared to people who do not use SBDAs.

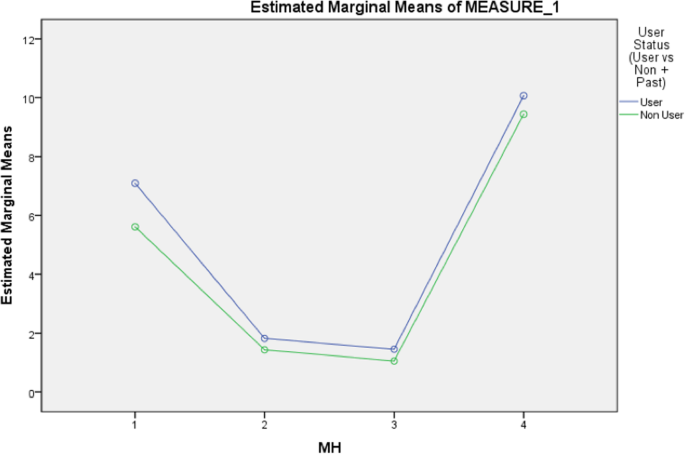

A cross-sectional online survey was completed by 437 participants. Mental health (MH) outcomes included the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale, Generalised Anxiety Disorder-2 scale, Patient Health Questionnaire-2, and Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Logistic regressions were used to estimate odds ratios of having a MH condition. A repeated measures analysis of variance was used with an apriori model which considered all four mental health scores together in a single analysis. The apriori model included user status, age and gender.

Thirty percent were current SBDA users. The majority of users and past users had met people face-to-face, with 26.1%(60/230) having met > 5 people, and only 22.6%(52/230) having never arranged a meeting. Almost 40%(39.1%; 90/230) had previously entered into a serious relationship with someone they had met on a SBDA. More participants reported a positive impact on self-esteem as a result of SBDA use (40.4%; 93/230), than a negative impact (28.7%;66/230).

Being a SBDA user was significantly associated with having psychological distress (OR = 2.51,95%CI (1.32–4.77)), p = 0.001), and depression (OR = 1.91,95%CI (1.04–3.52), p = 0.037) in the multivariable logistic regression models, adjusting for age, gender and sexual orientation. When the four MH scores were analysed together there was a significant difference ( p = 0.037) between being a user or non-user, with SDBA users having significantly higher mean scores for distress ( p = 0.001), anxiety ( p = 0.015) and depression ( p = 0.005). Increased frequency of use and longer duration of use were both associated with greater psychological distress and depression ( p < 0.05).

SBDA use is common and users report higher levels of depression, anxiety and distress compared to those who do not use the applications. Further studies are needed to determine causality and investigate specific patterns of SBDA use that are detrimental to mental health.

Peer Review reports

Swipe-Based Dating Applications (SBDAs) provide a platform for individuals to interact and form romantic or sexual connections before meeting face-to-face. SBDAs differ from other online dating platforms based on the feature of swiping on a mobile screen. Each user has a profile which other users can approve or reject by swiping the screen to the right or the left. If two individuals approve of each other’s profiles, it is considered a “match” and they can initiate a messaging interaction. Other differentiating characteristics include brief, image-dominated profiles and the incorporation of geolocation, facilitating user matches within a set geographical radius. There are a variety of SBDAs which follow this concept, such as Tinder, Bumble, Happn, and OkCupid.

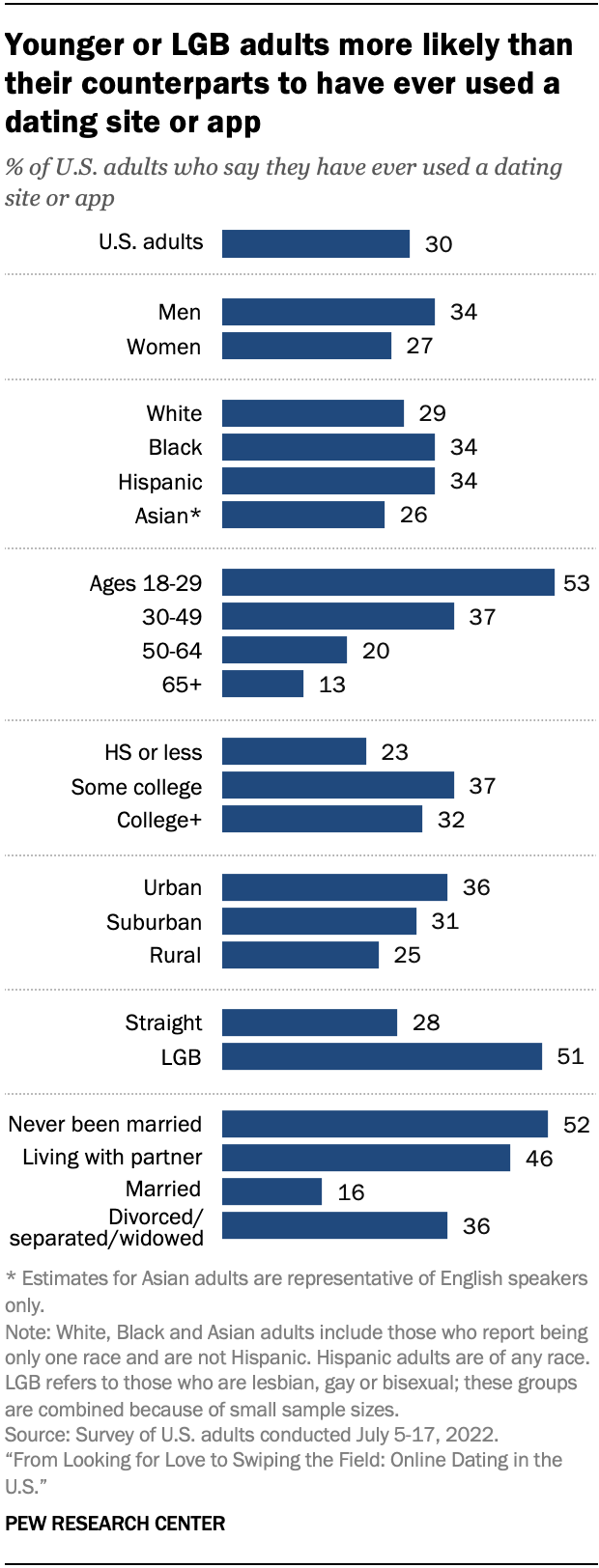

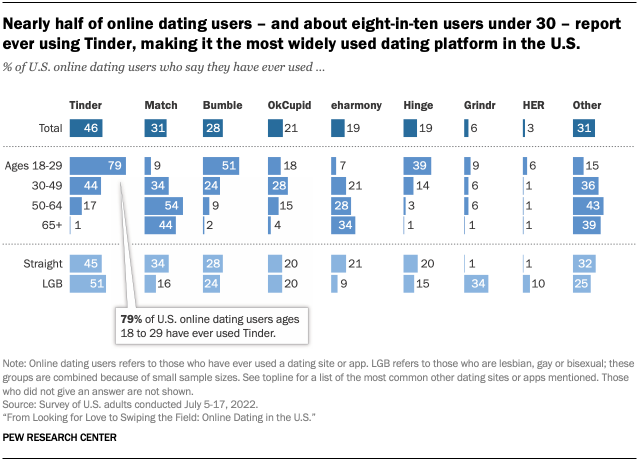

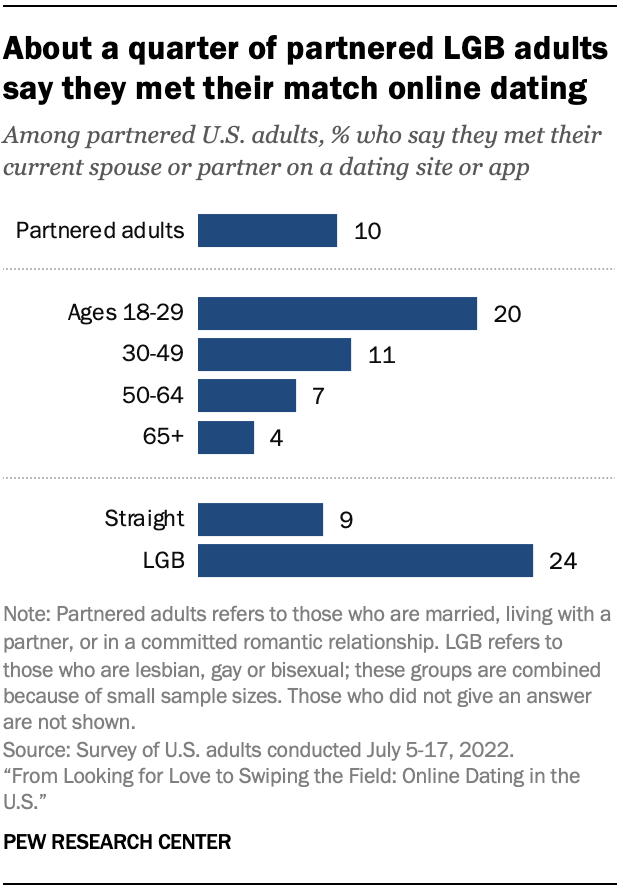

The Australian population of SBDA users is rapidly growing. In 2018, Tinder was the most popular mobile dating app in Australia, with approximately 57 million users worldwide [ 1 , 2 ]. Most SBDA users are aged between 18 and 34, and the largest increase in SBDA use has been amongst 18–24 year-olds. However, there has also been a sharp increase in SBDA use amongst 45–54 year-olds, rising by over 60%, and 55–64 year-olds, where SBDA use has doubled [ 3 ]. SBDA use is also rising internationally; of internet users in the United States, 19% are engaging in online dating (sites or applications) [ 4 ]. The role of SBDAs in formation of long term relationships is already significant and also rising; a 2017 survey of 14,000 recently married or engaged individuals in the United States found that almost one in five had met their partner via online dating [ 5 ]. A large, nationally representative survey and audit conducted by eHarmony predicted that by 2040, 70% of relationships will begin online [ 6 ].

With SBDA use increasing at such a rapid rate, investigation into the health implications of these applications is warranted. Such research has to date focused on investigating the link between these applications and high-risk sexual behaviour, particularly in men who have sex with men [ 7 ]. Currently, there is a paucity of research into the health impacts of SBDAs, especially with regards to mental health [ 8 ].

The significance of mental health as a public health issue is well established [ 9 , 10 ]; of Australians aged 16–85, 45% report having experienced a mental illness at least once in their lifetime. Amongst 18–34 year-olds, those who use SBDAs most, the annual prevalence of mental illness is approximately 25% [ 11 ]. Moreover, mental illness and substance abuse disorders were estimated to account for 12% of the total burden of disease in Australia [ 10 ]. However, mental health refers not only to the absence of mental illness, but to a state of wellbeing, characterised by productivity, appropriate coping and social contribution [ 12 ]. Therefore, while mental illness presents a significant public health burden and must be considered when investigating the health impacts of social and lifestyle factors, such as SBDA use, a broader view of implications for psychological wellbeing must also be considered.

A few studies have investigated the psychological impact of dating applications, assessing the relationship between Tinder use, self-esteem, body image and weight management. Strubel & Petrie found that Tinder use was significantly associated with decreased face and body satisfaction, more appearance comparisons and greater body shame, and, amongst males, lower self-esteem [ 8 ]. On the other hand, Rönnestad found only a weak relationship between increased intensity of Tinder use and decreased self-esteem; however this may be explained by the low intensity of use in this study. Correlations were 0.18 or lower for self-esteem and the scores for app usage, dating behaviour and tinder intensity [ 13 ]. A study by Tran et al. of almost 1800 adults found that dating application users were significantly more likely to engage in unhealthy weight control behaviours (such as laxative use, self-induced vomiting and use of anabolic steroids) compared to non-users [ 14 ].

To our knowledge, there have been no studies investigating the association between SBDA use and mood-based mental health outcomes, such as psychological distress or features of anxiety and depression. However, there have been studies investigating the relationship between mental health outcomes and social media use. SBDAs are innately similar to social media as they provide users a medium through which to interact and to bestow and receive peer approval; the ‘likes’ of Facebook and Instagram are replaced with ‘right swipes’ on Tinder and Bumble [ 8 ].

To date, research into the psychological impact of social media has yielded conflicting evidence. One study found a significant, dose-response association of increased frequency of social media use (with measures such as time per day and site visits per week) with increased likelihood of depression [ 15 ]. Contrarily, Primack et al. found the use of multiple social media platforms to be associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety independent of the total amount of time spent of social media [ 16 ]. However, some studies found no association between social media use and poorer mental health outcomes, such as suicidal ideation [ 17 , 18 , 19 ]. Other studies have investigated other aspects of use, beyond frequency and intensity; ‘problematic’ Facebook use, defined as Facebook use with addictive components similar to gambling addiction, has been associated with increased depressive symptoms and psychological distress [ 20 , 21 ]. A study of 18–29 year olds by Stapleton et al. found that while Instagram use did not directly impact user self-esteem, engaging in social comparison and validation-seeking via Instagram did negatively impact self-esteem [ 22 ]. A meta-analysis by Yoon et al. found a significant association between total time spent on social media and frequency of use with higher levels of depression [ 23 ]. This analysis also found that social comparisons made on social media had a greater relationship with depression levels than the overall level of use [ 23 ], providing a possible mediator of effect of social media on mental health, and one that may be present in SBDAs as well.

Existing research on the connection between social media use and mental health outcomes suggests that the way these applications and websites are used (to compare [ 22 , 23 ]; to seek validation [ 22 ]; with additive components [ 20 , 21 ]) is more significant than the frequency or time spent doing so. This validation-seeking is also seen in SBDAs.

Strubel & Petrie argue that SBDAs create a paradigm of instant gratification or rejection, placing users in a vulnerable position [ 8 ]. Furthermore, Sumter et al. found the pursuit of self-worth validation to be a key motivation for Tinder use in adults, further increasing the vulnerability of users to others’ acceptance or rejection [ 24 ]. This, combined with the emphasis placed on user images in SBDA [ 25 ], enhances the sexual objectification in these applications. The objectification theory suggests that such sexual objectification leads to internalisation of cultural standards of attractiveness and self-objectification, which in turn promotes body shame and prevents motivational states crucial to psychological wellbeing [ 8 , 26 ]. The pursuit of external peer validation seen in both social media and SBDAs, which may be implicated in poorer mental health outcomes associated with social media use, may also lead to poorer mental health in SBDA users.

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between Swipe-Based Dating Applications (SBDAs) and mental health outcomes by examining whether SBDA users over the age of 18 report higher levels of psychological distress, anxiety, depression, and lower self-esteem, compared to people who do not use SBDAs. Based on the similarities between social media and SBDAs, particularly the exposure to peer validation and rejection, we hypothesised that there would be similarities between the mental health implications of their use. As the pursuit of validation has already been found to be a motivator in Tinder use [ 24 ], and implicated in the adverse mental health impacts of social media [ 22 ], we hypothesised that SBDA users would experience poorer mental health compared to people who did not use SBDAs, reflected in increased psychological distress, symptoms of anxiety and depression, and lower self-esteem.

Recruitment and data collection

A cross sectional survey was conducted online using convenience sampling over a 3 month period between August and October 2018. Participants were recruited largely online via social media, including Facebook and Instagram. Administrative approval was sought before posting the survey link in relevant groups on these sites, including dating groups such as “Facebook Dating Australia” and community groups. A link to the survey was also disseminated by academic organisations and the Positive Adolescent Sexual Health Consortium. The survey was also disseminated via personal social networks, such as personal social media pages. The survey was created online using the secure Qualtrics software (version Aug-Oct 2018 Qualtrics, Provo, Utah).