- Product Management

How to Generate and Validate Product Hypotheses

What is a product hypothesis.

A hypothesis is a testable statement that predicts the relationship between two or more variables. In product development, we generate hypotheses to validate assumptions about customer behavior, market needs, or the potential impact of product changes. These experimental efforts help us refine the user experience and get closer to finding a product-market fit.

Product hypotheses are a key element of data-driven product development and decision-making. Testing them enables us to solve problems more efficiently and remove our own biases from the solutions we put forward.

Here’s an example: ‘If we improve the page load speed on our website (variable 1), then we will increase the number of signups by 15% (variable 2).’ So if we improve the page load speed, and the number of signups increases, then our hypothesis has been proven. If the number did not increase significantly (or not at all), then our hypothesis has been disproven.

In general, product managers are constantly creating and testing hypotheses. But in the context of new product development , hypothesis generation/testing occurs during the validation stage, right after idea screening .

Now before we go any further, let’s get one thing straight: What’s the difference between an idea and a hypothesis?

Idea vs hypothesis

Innovation expert Michael Schrage makes this distinction between hypotheses and ideas – unlike an idea, a hypothesis comes with built-in accountability. “But what’s the accountability for a good idea?” Schrage asks. “The fact that a lot of people think it’s a good idea? That’s a popularity contest.” So, not only should a hypothesis be tested, but by its very nature, it can be tested.

At Railsware, we’ve built our product development services on the careful selection, prioritization, and validation of ideas. Here’s how we distinguish between ideas and hypotheses:

Idea: A creative suggestion about how we might exploit a gap in the market, add value to an existing product, or bring attention to our product. Crucially, an idea is just a thought. It can form the basis of a hypothesis but it is not necessarily expected to be proven or disproven.

- We should get an interview with the CEO of our company published on TechCrunch.

- Why don’t we redesign our website?

- The Coupler.io team should create video tutorials on how to export data from different apps, and publish them on YouTube.

- Why not add a new ‘email templates’ feature to our Mailtrap product?

Hypothesis: A way of framing an idea or assumption so that it is testable, specific, and aligns with our wider product/team/organizational goals.

Examples:

- If we add a new ‘email templates’ feature to Mailtrap, we’ll see an increase in active usage of our email-sending API.

- Creating relevant video tutorials and uploading them to YouTube will lead to an increase in Coupler.io signups.

- If we publish an interview with our CEO on TechCrunch, 500 people will visit our website and 10 of them will install our product.

Now, it’s worth mentioning that not all hypotheses require testing . Sometimes, the process of creating hypotheses is just an exercise in critical thinking. And the simple act of analyzing your statement tells whether you should run an experiment or not. Remember: testing isn’t mandatory, but your hypotheses should always be inherently testable.

Let’s consider the TechCrunch article example again. In that hypothesis, we expect 500 readers to visit our product website, and a 2% conversion rate of those unique visitors to product users i.e. 10 people. But is that marginal increase worth all the effort? Conducting an interview with our CEO, creating the content, and collaborating with the TechCrunch content team – all of these tasks take time (and money) to execute. And by formulating that hypothesis, we can clearly see that in this case, the drawbacks (efforts) outweigh the benefits. So, no need to test it.

In a similar vein, a hypothesis statement can be a tool to prioritize your activities based on impact. We typically use the following criteria:

- The quality of impact

- The size of the impact

- The probability of impact

This lets us organize our efforts according to their potential outcomes – not the coolness of the idea, its popularity among the team, etc.

Now that we’ve established what a product hypothesis is, let’s discuss how to create one.

Start with a problem statement

Before you jump into product hypothesis generation, we highly recommend formulating a problem statement. This is a short, concise description of the issue you are trying to solve. It helps teams stay on track as they formalize the hypothesis and design the product experiments. It can also be shared with stakeholders to ensure that everyone is on the same page.

The statement can be worded however you like, as long as it’s actionable, specific, and based on data-driven insights or research. It should clearly outline the problem or opportunity you want to address.

Here’s an example: Our bounce rate is high (more than 90%) and we are struggling to convert website visitors into actual users. How might we improve site performance to boost our conversion rate?

How to generate product hypotheses

Now let’s explore some common, everyday scenarios that lead to product hypothesis generation. For our teams here at Railsware, it’s when:

- There’s a problem with an unclear root cause e.g. a sudden drop in one part of the onboarding funnel. We identify these issues by checking our product metrics or reviewing customer complaints.

- We are running ideation sessions on how to reach our goals (increase MRR, increase the number of users invited to an account, etc.)

- We are exploring growth opportunities e.g. changing a pricing plan, making product improvements , breaking into a new market.

- We receive customer feedback. For example, some users have complained about difficulties setting up a workspace within the product. So, we build a hypothesis on how to help them with the setup.

BRIDGES framework for ideation

When we are tackling a complex problem or looking for ways to grow the product, our teams use BRIDGeS – a robust decision-making and ideation framework. BRIDGeS makes our product discovery sessions more efficient. It lets us dive deep into the context of our problem so that we can develop targeted solutions worthy of testing.

Between 2-8 stakeholders take part in a BRIDGeS session. The ideation sessions are usually led by a product manager and can include other subject matter experts such as developers, designers, data analysts, or marketing specialists. You can use a virtual whiteboard such as Figjam or Miro (see our Figma template ) to record each colored note.

In the first half of a BRIDGeS session, participants examine the Benefits, Risks, Issues, and Goals of their subject in the ‘Problem Space.’ A subject is anything that is being described or dealt with; for instance, Coupler.io’s growth opportunities. Benefits are the value that a future solution can bring, Risks are potential issues they might face, Issues are their existing problems, and Goals are what the subject hopes to gain from the future solution. Each descriptor should have a designated color.

After we have broken down the problem using each of these descriptors, we move into the Solution Space. This is where we develop solution variations based on all of the benefits/risks/issues identified in the Problem Space (see the Uber case study for an in-depth example).

In the Solution Space, we start prioritizing those solutions and deciding which ones are worthy of further exploration outside of the framework – via product hypothesis formulation and testing, for example. At the very least, after the session, we will have a list of epics and nested tasks ready to add to our product roadmap.

How to write a product hypothesis statement

Across organizations, product hypothesis statements might vary in their subject, tone, and precise wording. But some elements never change. As we mentioned earlier, a hypothesis statement must always have two or more variables and a connecting factor.

1. Identify variables

Since these components form the bulk of a hypothesis statement, let’s start with a brief definition.

First of all, variables in a hypothesis statement can be split into two camps: dependent and independent. Without getting too theoretical, we can describe the independent variable as the cause, and the dependent variable as the effect . So in the Mailtrap example we mentioned earlier, the ‘add email templates feature’ is the cause i.e. the element we want to manipulate. Meanwhile, ‘increased usage of email sending API’ is the effect i.e the element we will observe.

Independent variables can be any change you plan to make to your product. For example, tweaking some landing page copy, adding a chatbot to the homepage, or enhancing the search bar filter functionality.

Dependent variables are usually metrics. Here are a few that we often test in product development:

- Number of sign-ups

- Number of purchases

- Activation rate (activation signals differ from product to product)

- Number of specific plans purchased

- Feature usage (API activation, for example)

- Number of active users

Bear in mind that your concept or desired change can be measured with different metrics. Make sure that your variables are well-defined, and be deliberate in how you measure your concepts so that there’s no room for misinterpretation or ambiguity.

For example, in the hypothesis ‘Users drop off because they find it hard to set up a project’ variables are poorly defined. Phrases like ‘drop off’ and ‘hard to set up’ are too vague. A much better way of saying it would be: If project automation rules are pre-defined (email sequence to responsible, scheduled tickets creation), we’ll see a decrease in churn. In this example, it’s clear which dependent variable has been chosen and why.

And remember, when product managers focus on delighting users and building something of value, it’s easier to market and monetize it. That’s why at Railsware, our product hypotheses often focus on how to increase the usage of a feature or product. If users love our product(s) and know how to leverage its benefits, we can spend less time worrying about how to improve conversion rates or actively grow our revenue, and more time enhancing the user experience and nurturing our audience.

2. Make the connection

The relationship between variables should be clear and logical. If it’s not, then it doesn’t matter how well-chosen your variables are – your test results won’t be reliable.

To demonstrate this point, let’s explore a previous example again: page load speed and signups.

Through prior research, you might already know that conversion rates are 3x higher for sites that load in 1 second compared to sites that take 5 seconds to load. Since there appears to be a strong connection between load speed and signups in general, you might want to see if this is also true for your product.

Here are some common pitfalls to avoid when defining the relationship between two or more variables:

Relationship is weak. Let’s say you hypothesize that an increase in website traffic will lead to an increase in sign-ups. This is a weak connection since website visitors aren’t necessarily motivated to use your product; there are more steps involved. A better example is ‘If we change the CTA on the pricing page, then the number of signups will increase.’ This connection is much stronger and more direct.

Relationship is far-fetched. This often happens when one of the variables is founded on a vanity metric. For example, increasing the number of social media subscribers will lead to an increase in sign-ups. However, there’s no particular reason why a social media follower would be interested in using your product. Oftentimes, it’s simply your social media content that appeals to them (and your audience isn’t interested in a product).

Variables are co-dependent. Variables should always be isolated from one another. Let’s say we removed the option “Register with Google” from our app. In this case, we can expect fewer users with Google workspace accounts to register. Obviously, it’s because there’s a direct dependency between variables (no registration with Google→no users with Google workspace accounts).

3. Set validation criteria

First, build some confirmation criteria into your statement . Think in terms of percentages (e.g. increase/decrease by 5%) and choose a relevant product metric to track e.g. activation rate if your hypothesis relates to onboarding. Consider that you don’t always have to hit the bullseye for your hypothesis to be considered valid. Perhaps a 3% increase is just as acceptable as a 5% one. And it still proves that a connection between your variables exists.

Secondly, you should also make sure that your hypothesis statement is realistic . Let’s say you have a hypothesis that ‘If we show users a banner with our new feature, then feature usage will increase by 10%.’ A few questions to ask yourself are: Is 10% a reasonable increase, based on your current feature usage data? Do you have the resources to create the tests (experimenting with multiple variations, distributing on different channels: in-app, emails, blog posts)?

Null hypothesis and alternative hypothesis

In statistical research, there are two ways of stating a hypothesis: null or alternative. But this scientific method has its place in hypothesis-driven development too…

Alternative hypothesis: A statement that you intend to prove as being true by running an experiment and analyzing the results. Hint: it’s the same as the other hypothesis examples we’ve described so far.

Example: If we change the landing page copy, then the number of signups will increase.

Null hypothesis: A statement you want to disprove by running an experiment and analyzing the results. It predicts that your new feature or change to the user experience will not have the desired effect.

Example: The number of signups will not increase if we make a change to the landing page copy.

What’s the point? Well, let’s consider the phrase ‘innocent until proven guilty’ as a version of a null hypothesis. We don’t assume that there is any relationship between the ‘defendant’ and the ‘crime’ until we have proof. So, we run a test, gather data, and analyze our findings — which gives us enough proof to reject the null hypothesis and validate the alternative. All of this helps us to have more confidence in our results.

Now that you have generated your hypotheses, and created statements, it’s time to prepare your list for testing.

Prioritizing hypotheses for testing

Not all hypotheses are created equal. Some will be essential to your immediate goal of growing the product e.g. adding a new data destination for Coupler.io. Others will be based on nice-to-haves or small fixes e.g. updating graphics on the website homepage.

Prioritization helps us focus on the most impactful solutions as we are building a product roadmap or narrowing down the backlog . To determine which hypotheses are the most critical, we use the MoSCoW framework. It allows us to assign a level of urgency and importance to each product hypothesis so we can filter the best 3-5 for testing.

MoSCoW is an acronym for Must-have, Should-have, Could-have, and Won’t-have. Here’s a breakdown:

- Must-have – hypotheses that must be tested, because they are strongly linked to our immediate project goals.

- Should-have – hypotheses that are closely related to our immediate project goals, but aren’t the top priority.

- Could-have – hypotheses of nice-to-haves that can wait until later for testing.

- Won’t-have – low-priority hypotheses that we may or may not test later on when we have more time.

How to test product hypotheses

Once you have selected a hypothesis, it’s time to test it. This will involve running one or more product experiments in order to check the validity of your claim.

The tricky part is deciding what type of experiment to run, and how many. Ultimately, this all depends on the subject of your hypothesis – whether it’s a simple copy change or a whole new feature. For instance, it’s not necessary to create a clickable prototype for a landing page redesign. In that case, a user-wide update would do.

On that note, here are some of the approaches we take to hypothesis testing at Railsware:

A/B testing

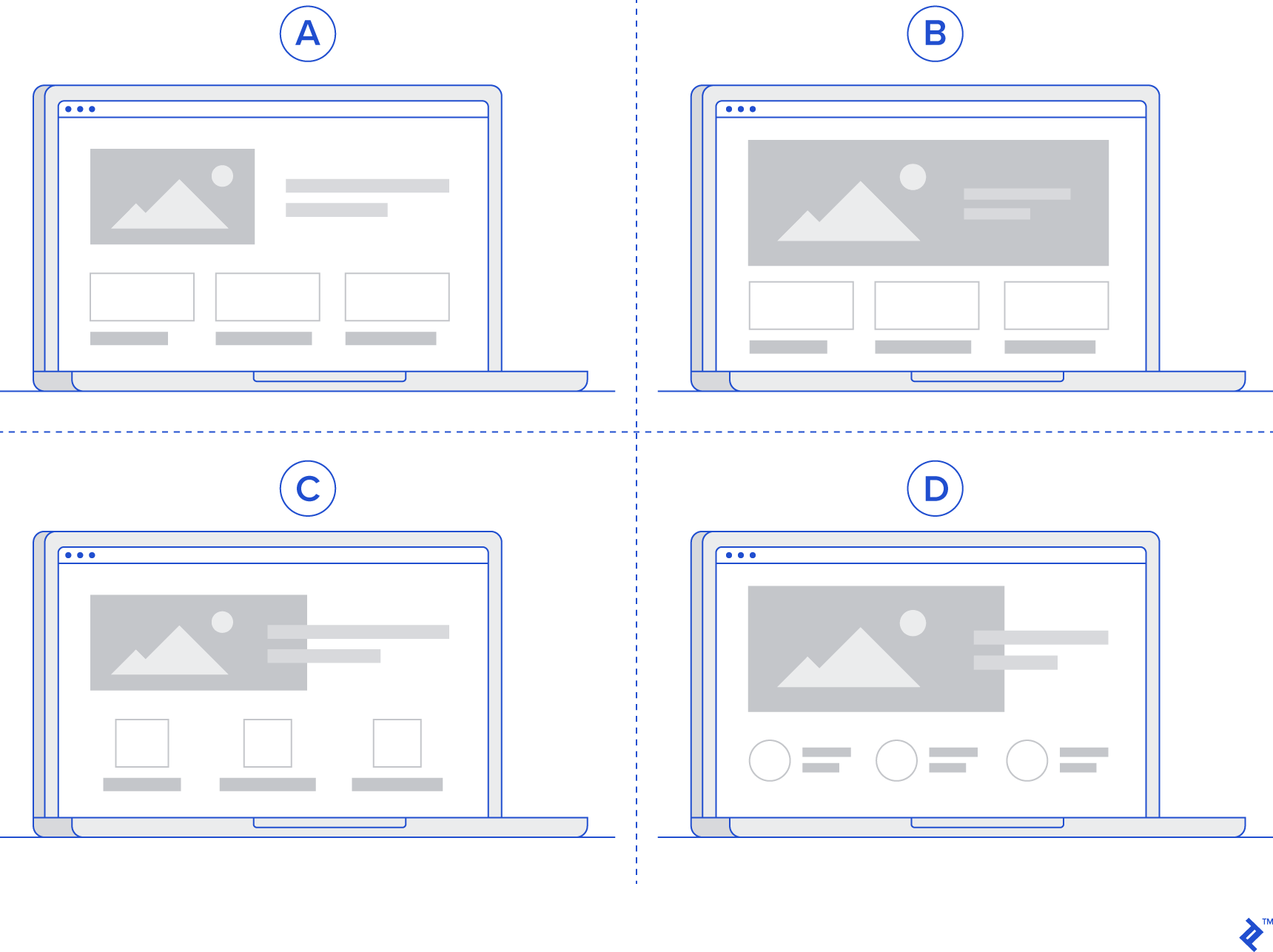

A/B or split testing involves creating two or more different versions of a webpage/feature/functionality and collecting information about how users respond to them.

Let’s say you wanted to validate a hypothesis about the placement of a search bar on your application homepage. You could design an A/B test that shows two different versions of that search bar’s placement to your users (who have been split equally into two camps: a control group and a variant group). Then, you would choose the best option based on user data. A/B tests are suitable for testing responses to user experience changes, especially if you have more than one solution to test.

Prototyping

When it comes to testing a new product design, prototyping is the method of choice for many Lean startups and organizations. It’s a cost-effective way of collecting feedback from users, fast, and it’s possible to create prototypes of individual features too. You may take this approach to hypothesis testing if you are working on rolling out a significant new change e.g adding a brand-new feature, redesigning some aspect of the user flow, etc. To control costs at this point in the new product development process , choose the right tools — think Figma for clickable walkthroughs or no-code platforms like Bubble.

Deliveroo feature prototype example

Let’s look at how feature prototyping worked for the food delivery app, Deliveroo, when their product team wanted to ‘explore personalized recommendations, better filtering and improved search’ in 2018. To begin, they created a prototype of the customer discovery feature using web design application, Framer.

One of the most important aspects of this feature prototype was that it contained live data — real restaurants, real locations. For test users, this made the hypothetical feature feel more authentic. They were seeing listings and recommendations for real restaurants in their area, which helped immerse them in the user experience, and generate more honest and specific feedback. Deliveroo was then able to implement this feedback in subsequent iterations.

Asking your users

Interviewing customers is an excellent way to validate product hypotheses. It’s a form of qualitative testing that, in our experience, produces better insights than user surveys or general user research. Sessions are typically run by product managers and involve asking in-depth interview questions to one customer at a time. They can be conducted in person or online (through a virtual call center , for instance) and last anywhere between 30 minutes to 1 hour.

Although CustDev interviews may require more effort to execute than other tests (the process of finding participants, devising questions, organizing interviews, and honing interview skills can be time-consuming), it’s still a highly rewarding approach. You can quickly validate assumptions by asking customers about their pain points, concerns, habits, processes they follow, and analyzing how your solution fits into all of that.

Wizard of Oz

The Wizard of Oz approach is suitable for gauging user interest in new features or functionalities. It’s done by creating a prototype of a fake or future feature and monitoring how your customers or test users interact with it.

For example, you might have a hypothesis that your number of active users will increase by 15% if you introduce a new feature. So, you design a new bare-bones page or simple button that invites users to access it. But when they click on the button, a pop-up appears with a message such as ‘coming soon.’

By measuring the frequency of those clicks, you could learn a lot about the demand for this new feature/functionality. However, while these tests can deliver fast results, they carry the risk of backfiring. Some customers may find fake features misleading, making them less likely to engage with your product in the future.

User-wide updates

One of the speediest ways to test your hypothesis is by rolling out an update for all users. It can take less time and effort to set up than other tests (depending on how big of an update it is). But due to the risk involved, you should stick to only performing these kinds of tests on small-scale hypotheses. Our teams only take this approach when we are almost certain that our hypothesis is valid.

For example, we once had an assumption that the name of one of Mailtrap ’s entities was the root cause of a low activation rate. Being an active Mailtrap customer meant that you were regularly sending test emails to a place called ‘Demo Inbox.’ We hypothesized that the name was confusing (the word ‘demo’ implied it was not the main inbox) and this was preventing new users from engaging with their accounts. So, we updated the page, changed the name to ‘My Inbox’ and added some ‘to-do’ steps for new users. We saw an increase in our activation rate almost immediately, validating our hypothesis.

Feature flags

Creating feature flags involves only releasing a new feature to a particular subset or small percentage of users. These features come with a built-in kill switch; a piece of code that can be executed or skipped, depending on who’s interacting with your product.

Since you are only showing this new feature to a selected group, feature flags are an especially low-risk method of testing your product hypothesis (compared to Wizard of Oz, for example, where you have much less control). However, they are also a little bit more complex to execute than the others — you will need to have an actual coded product for starters, as well as some technical knowledge, in order to add the modifiers ( only when… ) to your new coded feature.

Let’s revisit the landing page copy example again, this time in the context of testing.

So, for the hypothesis ‘If we change the landing page copy, then the number of signups will increase,’ there are several options for experimentation. We could share the copy with a small sample of our users, or even release a user-wide update. But A/B testing is probably the best fit for this task. Depending on our budget and goal, we could test several different pieces of copy, such as:

- The current landing page copy

- Copy that we paid a marketing agency 10 grand for

- Generic copy we wrote ourselves, or removing most of the original copy – just to see how making even a small change might affect our numbers.

Remember, every hypothesis test must have a reasonable endpoint. The exact length of the test will depend on the type of feature/functionality you are testing, the size of your user base, and how much data you need to gather. Just make sure that the experiment running time matches the hypothesis scope. For instance, there is no need to spend 8 weeks experimenting with a piece of landing page copy. That timeline is more appropriate for say, a Wizard of Oz feature.

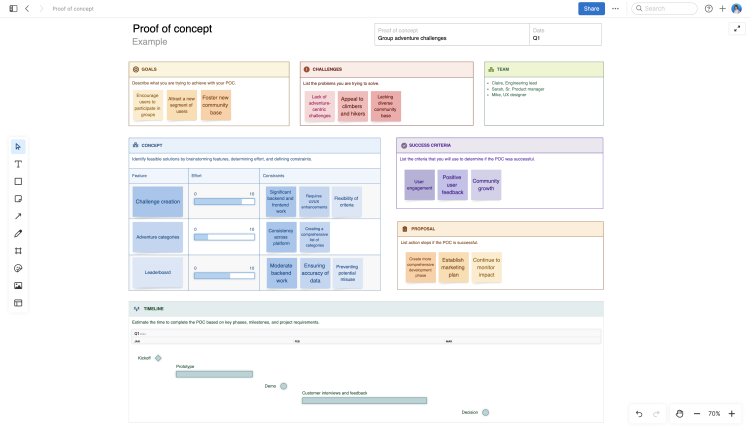

Recording hypotheses statements and test results

Finally, it’s time to talk about where you will write down and keep track of your hypotheses. Creating a single source of truth will enable you to track all aspects of hypothesis generation and testing with ease.

At Railsware, our product managers create a document for each individual hypothesis, using tools such as Coda or Google Sheets. In that document, we record the hypothesis statement, as well as our plans, process, results, screenshots, product metrics, and assumptions.

We share this document with our team and stakeholders, to ensure transparency and invite feedback. It’s also a resource we can refer back to when we are discussing a new hypothesis — a place where we can quickly access information relating to a previous test.

Understanding test results and taking action

The other half of validating product hypotheses involves evaluating data and drawing reasonable conclusions based on what you find. We do so by analyzing our chosen product metric(s) and deciding whether there is enough data available to make a solid decision. If not, we may extend the test’s duration or run another one. Otherwise, we move forward. An experimental feature becomes a real feature, a chatbot gets implemented on the customer support page, and so on.

Something to keep in mind: the integrity of your data is tied to how well the test was executed, so here are a few points to consider when you are testing and analyzing results:

Gather and analyze data carefully. Ensure that your data is clean and up-to-date when running quantitative tests and tracking responses via analytics dashboards. If you are doing customer interviews, make sure to record the meetings (with consent) so that your notes will be as accurate as possible.

Conduct the right amount of product experiments. It can take more than one test to determine whether your hypothesis is valid or invalid. However, don’t waste too much time experimenting in the hopes of getting the result you want. Know when to accept the evidence and move on.

Choose the right audience segment. Don’t cast your net too wide. Be specific about who you want to collect data from prior to running the test. Otherwise, your test results will be misleading and you won’t learn anything new.

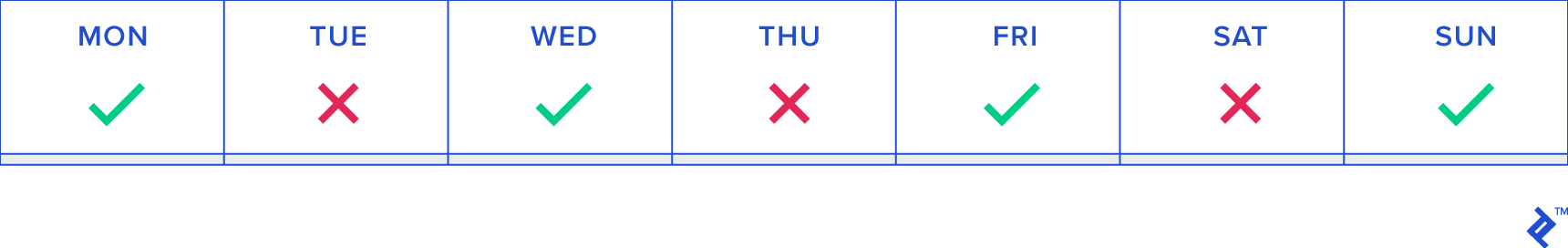

Watch out for bias. Avoid confirmation bias at all costs. Don’t make the mistake of including irrelevant data just because it bolsters your results. For example, if you are gathering data about how users are interacting with your product Monday-Friday, don’t include weekend data just because doing so would alter the data and ‘validate’ your hypothesis.

- Not all failed hypotheses should be treated as losses. Even if you didn’t get the outcome you were hoping for, you may still have improved your product. Let’s say you implemented SSO authentication for premium users, but unfortunately, your free users didn’t end up switching to premium plans. In this case, you still added value to the product by streamlining the login process for paying users.

- Yes, taking a hypothesis-driven approach to product development is important. But remember, you don’t have to test everything . Use common sense first. For example, if your website copy is confusing and doesn’t portray the value of the product, then you should still strive to replace it with better copy – regardless of how this affects your numbers in the short term.

Wrapping Up

The process of generating and validating product hypotheses is actually pretty straightforward once you’ve got the hang of it. All you need is a valid question or problem, a testable statement, and a method of validation. Sure, hypothesis-driven development requires more of a time commitment than just ‘giving it a go.’ But ultimately, it will help you tune the product to the wants and needs of your customers.

If you share our data-driven approach to product development and engineering, check out our services page to learn more about how we work with our clients!

How to Generate and Validate Product Hypotheses

Every product owner knows that it takes effort to build something that'll cater to user needs. You'll have to make many tough calls if you wish to grow the company and evolve the product so it delivers more value. But how do you decide what to change in the product, your marketing strategy, or the overall direction to succeed? And how do you make a product that truly resonates with your target audience?

There are many unknowns in business, so many fundamental decisions start from a simple "what if?". But they can't be based on guesses, as you need some proof to fill in the blanks reasonably.

Because there's no universal recipe for successfully building a product, teams collect data, do research, study the dynamics, and generate hypotheses according to the given facts. They then take corresponding actions to find out whether they were right or wrong, make conclusions, and most likely restart the process again.

On this page, we thoroughly inspect product hypotheses. We'll go over what they are, how to create hypothesis statements and validate them, and what goes after this step.

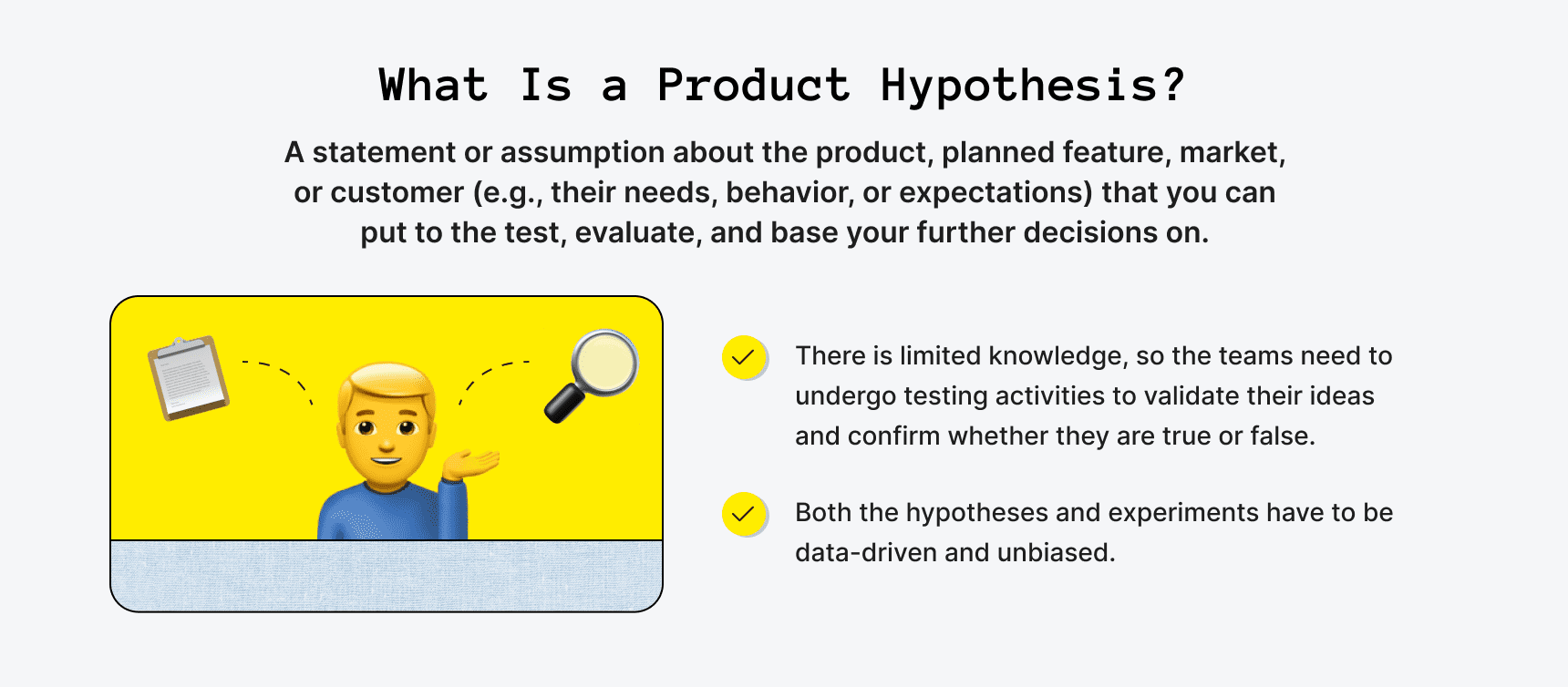

What Is a Hypothesis in Product Management?

A hypothesis in product development and product management is a statement or assumption about the product, planned feature, market, or customer (e.g., their needs, behavior, or expectations) that you can put to the test, evaluate, and base your further decisions on . This may, for instance, regard the upcoming product changes as well as the impact they can result in.

A hypothesis implies that there is limited knowledge. Hence, the teams need to undergo testing activities to validate their ideas and confirm whether they are true or false.

Hypotheses guide the product development process and may point at important findings to help build a better product that'll serve user needs. In essence, teams create hypothesis statements in an attempt to improve the offering, boost engagement, increase revenue, find product-market fit quicker, or for other business-related reasons.

It's sort of like an experiment with trial and error, yet, it is data-driven and should be unbiased . This means that teams don't make assumptions out of the blue. Instead, they turn to the collected data, conducted market research , and factual information, which helps avoid completely missing the mark. The obtained results are then carefully analyzed and may influence decision-making.

Such experiments backed by data and analysis are an integral aspect of successful product development and allow startups or businesses to dodge costly startup mistakes .

When do teams create hypothesis statements and validate them? To some extent, hypothesis testing is an ongoing process to work on constantly. It may occur during various product development life cycle stages, from early phases like initiation to late ones like scaling.

In any event, the key here is learning how to generate hypothesis statements and validate them effectively. We'll go over this in more detail later on.

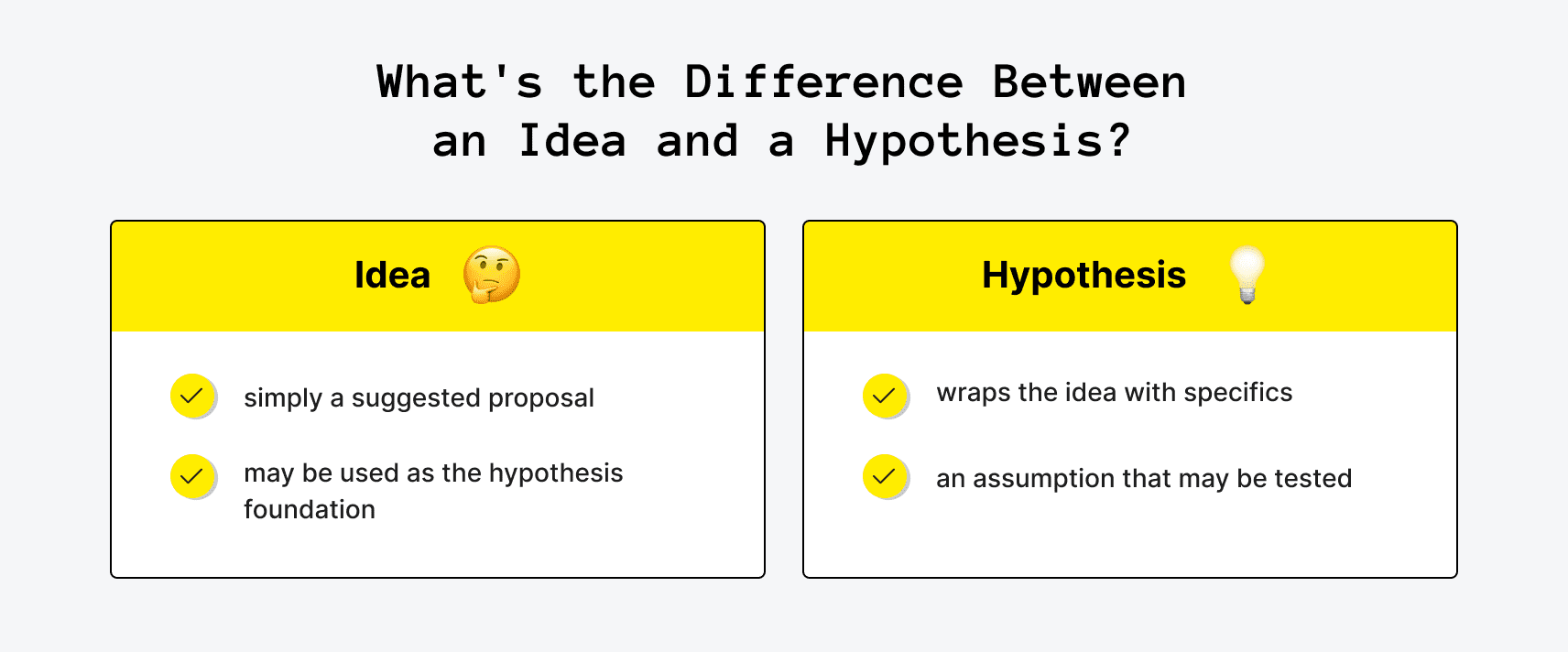

Idea vs. Hypothesis Compared

You might be wondering whether ideas and hypotheses are the same thing. Well, there are a few distinctions.

An idea is simply a suggested proposal. Say, a teammate comes up with something you can bring to life during a brainstorming session or pitches in a suggestion like "How about we shorten the checkout process?". You can jot down such ideas and then consider working on them if they'll truly make a difference and improve the product, strategy, or result in other business benefits. Ideas may thus be used as the hypothesis foundation when you decide to prove a concept.

A hypothesis is the next step, when an idea gets wrapped with specifics to become an assumption that may be tested. As such, you can refine the idea by adding details to it. The previously mentioned idea can be worded into a product hypothesis statement like: "The cart abandonment rate is high, and many users flee at checkout. But if we shorten the checkout process by cutting down the number of steps to only two and get rid of four excessive fields, we'll simplify the user journey, boost satisfaction, and may get up to 15% more completed orders".

A hypothesis is something you can test in an attempt to reach a certain goal. Testing isn't obligatory in this scenario, of course, but the idea may be tested if you weigh the pros and cons and decide that the required effort is worth a try. We'll explain how to create hypothesis statements next.

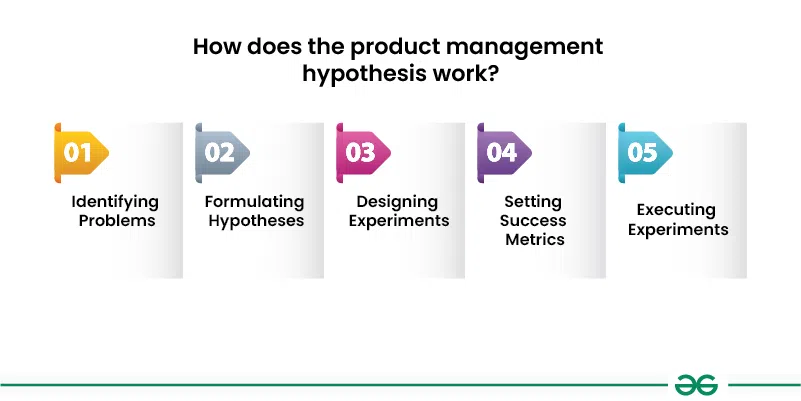

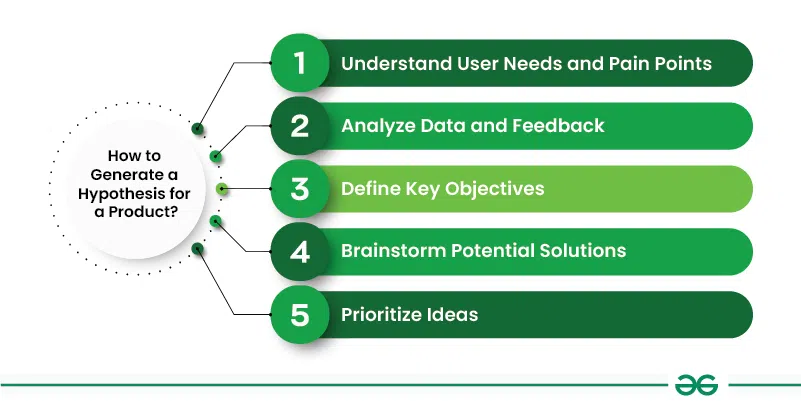

How to Generate a Hypothesis for a Product

The last thing those developing a product want is to invest time and effort into something that won't bring any visible results, fall short of customer expectations, or won't live up to their needs. Therefore, to increase the chances of achieving a successful outcome and product-led growth , teams may need to revisit their product development approach by optimizing one of the starting points of the process: learning to make reasonable product hypotheses.

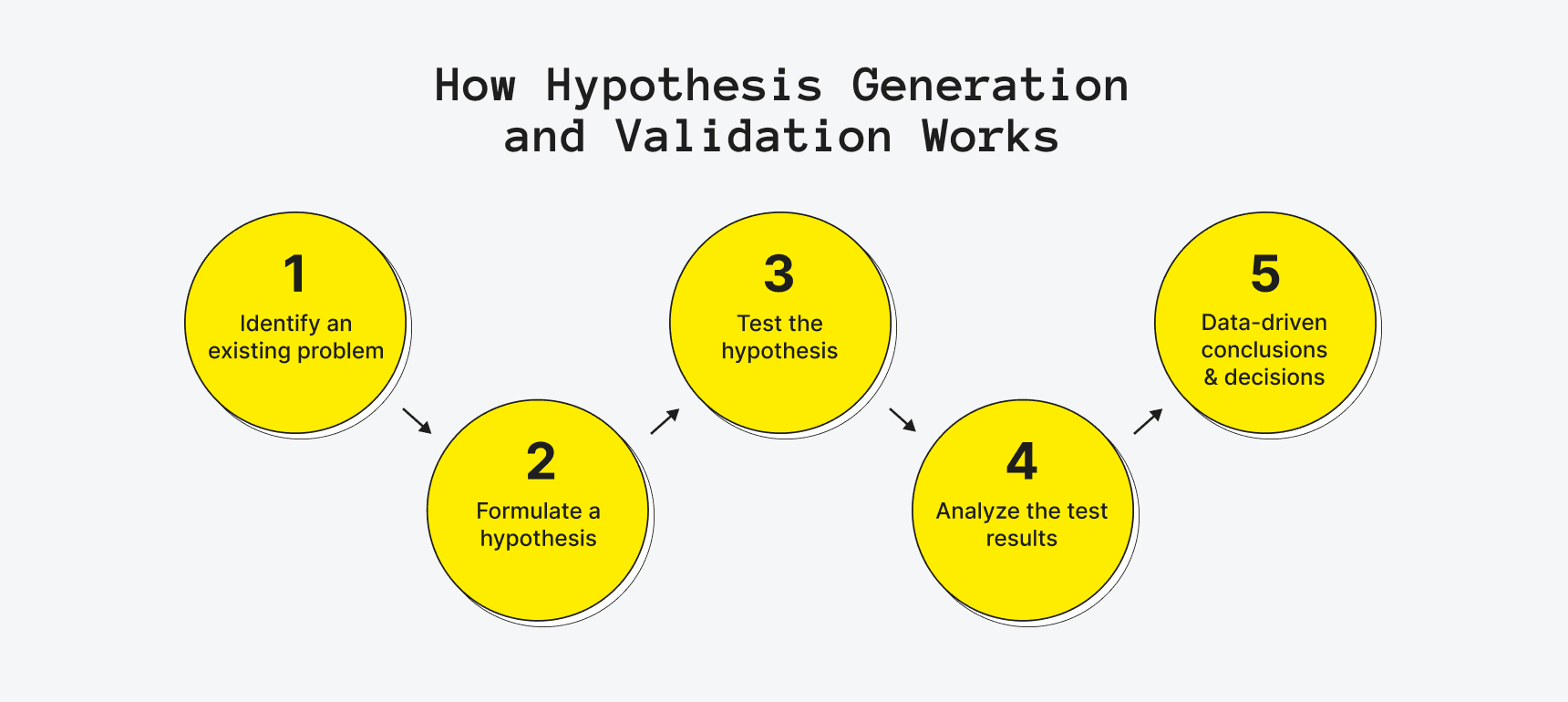

If the entire procedure is structured, this may assist you during such stages as the discovery phase and raise the odds of reaching your product goals and setting your business up for success. Yet, what's the entire process like?

- It all starts with identifying an existing problem . Is there a product area that's experiencing a downfall, a visible trend, or a market gap? Are users often complaining about something in their feedback? Or is there something you're willing to change (say, if you aim to get more profit, increase engagement, optimize a process, expand to a new market, or reach your OKRs and KPIs faster)?

- Teams then need to work on formulating a hypothesis . They put the statement into concise and short wording that describes what is expected to achieve. Importantly, it has to be relevant, actionable, backed by data, and without generalizations.

- Next, they have to test the hypothesis by running experiments to validate it (for instance, via A/B or multivariate testing, prototyping, feedback collection, or other ways).

- Then, the obtained results of the test must be analyzed . Did one element or page version outperform the other? Depending on what you're testing, you can look into various merits or product performance metrics (such as the click rate, bounce rate, or the number of sign-ups) to assess whether your prediction was correct.

- Finally, the teams can make conclusions that could lead to data-driven decisions. For example, they can make corresponding changes or roll back a step.

How Else Can You Generate Product Hypotheses?

Such processes imply sharing ideas when a problem is spotted by digging deep into facts and studying the possible risks, goals, benefits, and outcomes. You may apply various MVP tools like (FigJam, Notion, or Miro) that were designed to simplify brainstorming sessions, systemize pitched suggestions, and keep everyone organized without losing any ideas.

Predictive product analysis can also be integrated into this process, leveraging data and insights to anticipate market trends and consumer preferences, thus enhancing decision-making and product development strategies. This approach fosters a more proactive and informed approach to innovation, ensuring products are not only relevant but also resonate with the target audience, ultimately increasing their chances of success in the market.

Besides, you can settle on one of the many frameworks that facilitate decision-making processes , ideation phases, or feature prioritization . Such frameworks are best applicable if you need to test your assumptions and structure the validation process. These are a few common ones if you're looking toward a systematic approach:

- Business Model Canvas (used to establish the foundation of the business model and helps find answers to vitals like your value proposition, finding the right customer segment, or the ways to make revenue);

- Lean Startup framework (the lean startup framework uses a diagram-like format for capturing major processes and can be handy for testing various hypotheses like how much value a product brings or assumptions on personas, the problem, growth, etc.);

- Design Thinking Process (is all about interactive learning and involves getting an in-depth understanding of the customer needs and pain points, which can be formulated into hypotheses followed by simple prototypes and tests).

Need a hand with product development?

Upsilon's team of pros is ready to share our expertise in building tech products.

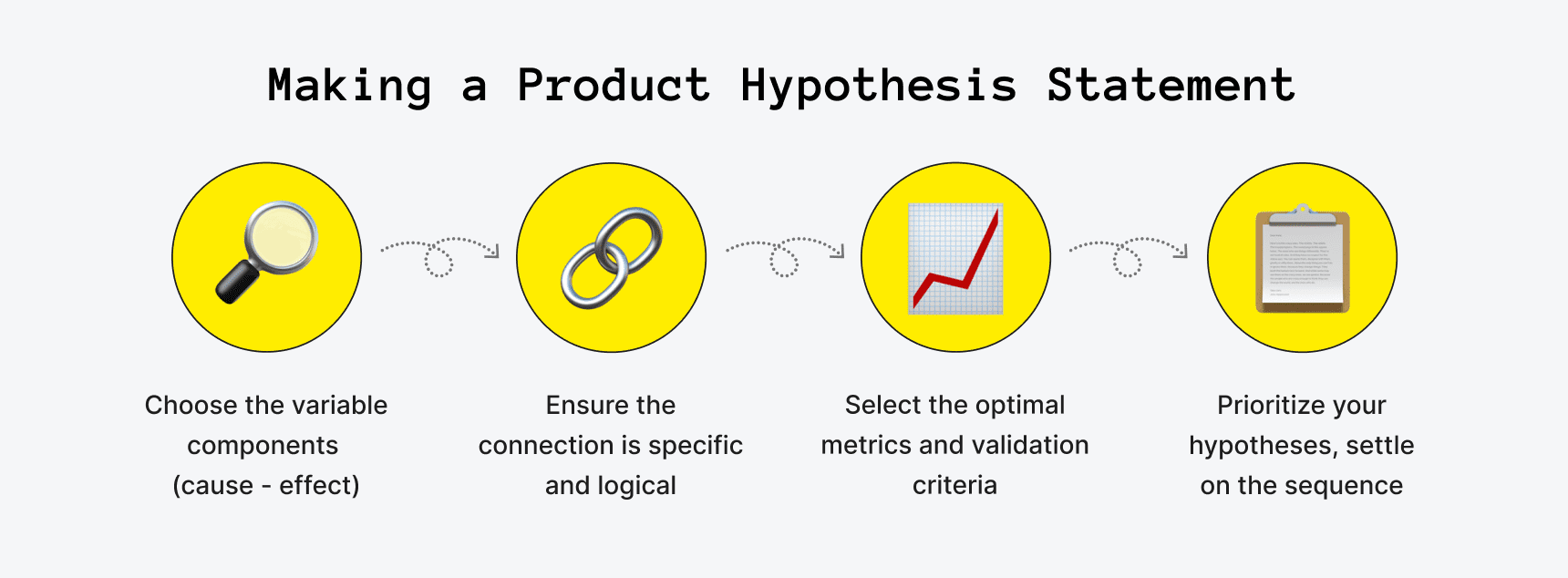

How to Make a Hypothesis Statement for a Product

Once you've indicated the addressable problem or opportunity and broken down the issue in focus, you need to work on formulating the hypotheses and associated tasks. By the way, it works the same way if you want to prove that something will be false (a.k.a null hypothesis).

If you're unsure how to write a hypothesis statement, let's explore the essential steps that'll set you on the right track.

Step 1: Allocate the Variable Components

Product hypotheses are generally different for each case, so begin by pinpointing the major variables, i.e., the cause and effect . You'll need to outline what you think is supposed to happen if a change or action gets implemented.

Put simply, the "cause" is what you're planning to change, and the "effect" is what will indicate whether the change is bringing in the expected results. Falling back on the example we brought up earlier, the ineffective checkout process can be the cause, while the increased percentage of completed orders is the metric that'll show the effect.

Make sure to also note such vital points as:

- what the problem and solution are;

- what are the benefits or the expected impact/successful outcome;

- which user group is affected;

- what are the risks;

- what kind of experiments can help test the hypothesis;

- what can measure whether you were right or wrong.

Step 2: Ensure the Connection Is Specific and Logical

Mind that generic connections that lack specifics will get you nowhere. So if you're thinking about how to word a hypothesis statement, make sure that the cause and effect include clear reasons and a logical dependency .

Think about what can be the precise and link showing why A affects B. In our checkout example, it could be: fewer steps in the checkout and the removed excessive fields will speed up the process, help avoid confusion, irritate users less, and lead to more completed orders. That's much more explicit than just stating the fact that the checkout needs to be changed to get more completed orders.

Step 3: Decide on the Data You'll Collect

Certainly, multiple things can be used to measure the effect. Therefore, you need to choose the optimal metrics and validation criteria that'll best envision if you're moving in the right direction.

If you need a tip on how to create hypothesis statements that won't result in a waste of time, try to avoid vagueness and be as specific as you can when selecting what can best measure and assess the results of your hypothesis test. The criteria must be measurable and tied to the hypotheses . This can be a realistic percentage or number (say, you expect a 15% increase in completed orders or 2x fewer cart abandonment cases during the checkout phase).

Once again, if you're not realistic, then you might end up misinterpreting the results. Remember that sometimes an increase that's even as little as 2% can make a huge difference, so why make 50% the merit if it's not achievable in the first place?

Step 4: Settle on the Sequence

It's quite common that you'll end up with multiple product hypotheses. Some are more important than others, of course, and some will require more effort and input.

Therefore, just as with the features on your product development roadmap , prioritize your hypotheses according to their impact and importance. Then, group and order them, especially if the results of some hypotheses influence others on your list.

Product Hypothesis Examples

To demonstrate how to formulate your assumptions clearly, here are several more apart from the example of a hypothesis statement given above:

- Adding a wishlist feature to the cart with the possibility to send a gift hint to friends via email will increase the likelihood of making a sale and bring in additional sign-ups.

- Placing a limited-time promo code banner stripe on the home page will increase the number of sales in March.

- Moving up the call to action element on the landing page and changing the button text will increase the click-through rate twice.

- By highlighting a new way to use the product, we'll target a niche customer segment (i.e., single parents under 30) and acquire 5% more leads.

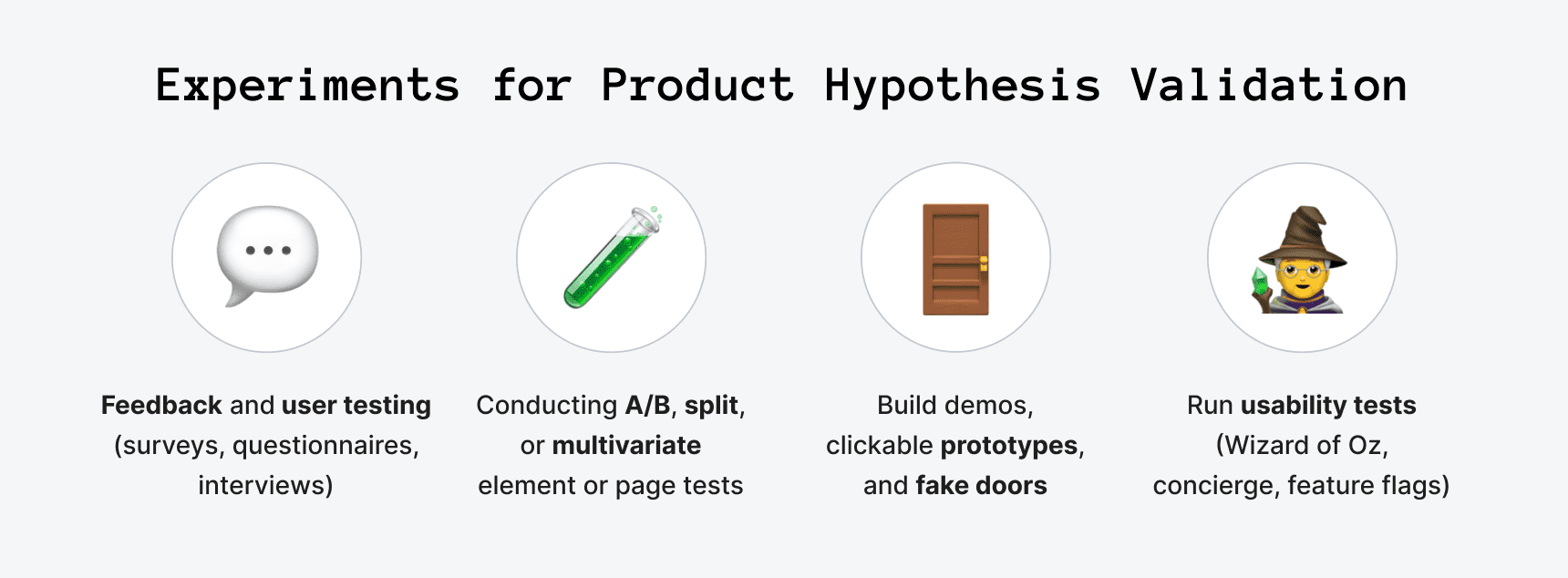

How to Validate Hypothesis Statements: The Process Explained

There are multiple options when it comes to validating hypothesis statements. To get appropriate results, you have to come up with the right experiment that'll help you test the hypothesis. You'll need a control group or people who represent your target audience segments or groups to participate (otherwise, your results might not be accurate).

What can serve as the experiment you may run? Experiments may take tons of different forms, and you'll need to choose the one that clicks best with your hypothesis goals (and your available resources, of course). The same goes for how long you'll have to carry out the test (say, a time period of two months or as little as two weeks). Here are several to get you started.

Feedback and User Testing

Talking to users, potential customers, or members of your own online startup community can be another way to test your hypotheses. You may use surveys, questionnaires, or opt for more extensive interviews to validate hypothesis statements and find out what people think. This assumption validation approach involves your existing or potential users and might require some additional time, but can bring you many insights.

Conduct A/B or Multivariate Tests

One of the experiments you may develop involves making more than one version of an element or page to see which option resonates with the users more. As such, you can have a call to action block with different wording or play around with the colors, imagery, visuals, and other things.

To run such split experiments, you can apply tools like VWO that allows to easily construct alternative designs and split what your users see (e.g., one half of the users will see version one, while the other half will see version two). You can track various metrics and apply heatmaps, click maps, and screen recordings to learn more about user response and behavior. Mind, though, that the key to such tests is to get as many users as you can give the tests time. Don't jump to conclusions too soon or if very few people participated in your experiment.

Build Prototypes and Fake Doors

Demos and clickable prototypes can be a great way to save time and money on costly feature or product development. A prototype also allows you to refine the design. However, they can also serve as experiments for validating hypotheses, collecting data, and getting feedback.

For instance, if you have a new feature in mind and want to ensure there is interest, you can utilize such MVP types as fake doors . Make a short demo recording of the feature and place it on your landing page to track interest or test how many people sign up.

Usability Testing

Similarly, you can run experiments to observe how users interact with the feature, page, product, etc. Usually, such experiments are held on prototype testing platforms with a focus group representing your target visitors. By showing a prototype or early version of the design to users, you can view how people use the solution, where they face problems, or what they don't understand. This may be very helpful if you have hypotheses regarding redesigns and user experience improvements before you move on from prototype to MVP development.

You can even take it a few steps further and build a barebone feature version that people can really interact with, yet you'll be the one behind the curtain to make it happen. There were many MVP examples when companies applied Wizard of Oz or concierge MVPs to validate their hypotheses.

Or you can actually develop some functionality but release it for only a limited number of people to see. This is referred to as a feature flag , which can show really specific results but is effort-intensive.

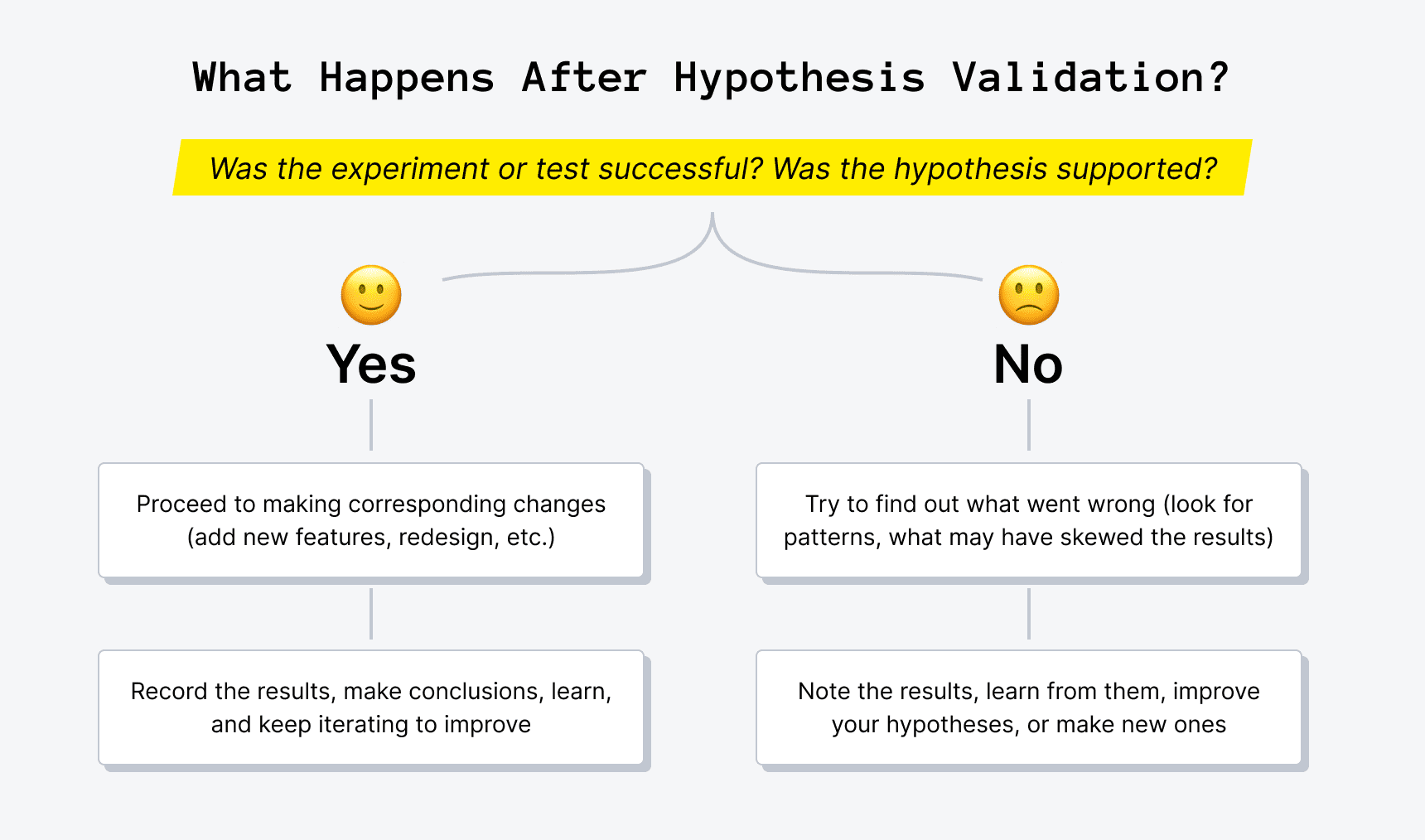

What Comes After Hypothesis Validation?

Analysis is what you move on to once you've run the experiment. This is the time to review the collected data, metrics, and feedback to validate (or invalidate) the hypothesis.

You have to evaluate the experiment's results to determine whether your product hypotheses were valid or not. For example, if you were testing two versions of an element design, color scheme, or copy, look into which one performed best.

It is crucial to be certain that you have enough data to draw conclusions, though, and that it's accurate and unbiased . Because if you don't, this may be a sign that your experiment needs to be run for some additional time, be altered, or held once again. You won't want to make a solid decision based on uncertain or misleading results, right?

- If the hypothesis was supported , proceed to making corresponding changes (such as implementing a new feature, changing the design, rephrasing your copy, etc.). Remember that your aim was to learn and iterate to improve.

- If your hypothesis was proven false , think of it as a valuable learning experience. The main goal is to learn from the results and be able to adjust your processes accordingly. Dig deep to find out what went wrong, look for patterns and things that may have skewed the results. But if all signs show that you were wrong with your hypothesis, accept this outcome as a fact, and move on. This can help you make conclusions on how to better formulate your product hypotheses next time. Don't be too judgemental, though, as a failed experiment might only mean that you need to improve the current hypothesis, revise it, or create a new one based on the results of this experiment, and run the process once more.

On another note, make sure to record your hypotheses and experiment results . Some companies use CRMs to jot down the key findings, while others use something as simple as Google Docs. Either way, this can be your single source of truth that can help you avoid running the same experiments or allow you to compare results over time.

Have doubts about how to bring your product to life?

Upsilon's team of pros can help you build a product most optimally.

Final Thoughts on Product Hypotheses

The hypothesis-driven approach in product development is a great way to avoid uncalled-for risks and pricey mistakes. You can back up your assumptions with facts, observe your target audience's reactions, and be more certain that this move will deliver value.

However, this only makes sense if the validation of hypothesis statements is backed by relevant data that'll allow you to determine whether the hypothesis is valid or not. By doing so, you can be certain that you're developing and testing hypotheses to accelerate your product management and avoiding decisions based on guesswork.

Certainly, a failed experiment may bring you just as much knowledge and findings as one that succeeds. Teams have to learn from their mistakes, boost their hypothesis generation and testing knowledge, and make improvements according to the results of their experiments. This is an ongoing process, of course, as no product can grow if it isn't iterated and improved.

If you're only planning to or are currently building a product, Upsilon can lend you a helping hand. Our team has years of experience providing product development services for growth-stage startups and building MVPs for early-stage businesses , so you can use our expertise and knowledge to dodge many mistakes. Don't be shy to contact us to discuss your needs!

Information Architecture Design: A Product Discovery Step

How to Prototype a Product: Steps, Tips, and Best Practices

What Is Wireframing and Its Role in Product Development

Never miss an update.

SHARE THIS POST

Product best practices

Product hypothesis - a guide to create meaningful hypotheses.

13 December, 2023

Growth Manager

Data-driven development is no different than a scientific experiment. You repeatedly form hypotheses, test them, and either implement (or reject) them based on the results. It’s a proven system that leads to better apps and happier users.

Let’s get started.

What is a product hypothesis?

A product hypothesis is an educated guess about how a change to a product will impact important metrics like revenue or user engagement. It's a testable statement that needs to be validated to determine its accuracy.

The most common format for product hypotheses is “If… than…”:

“If we increase the font size on our homepage, then more customers will convert.”

“If we reduce form fields from 5 to 3, then more users will complete the signup process.”

At UXCam, we believe in a data-driven approach to developing product features. Hypotheses provide an effective way to structure development and measure results so you can make informed decisions about how your product evolves over time.

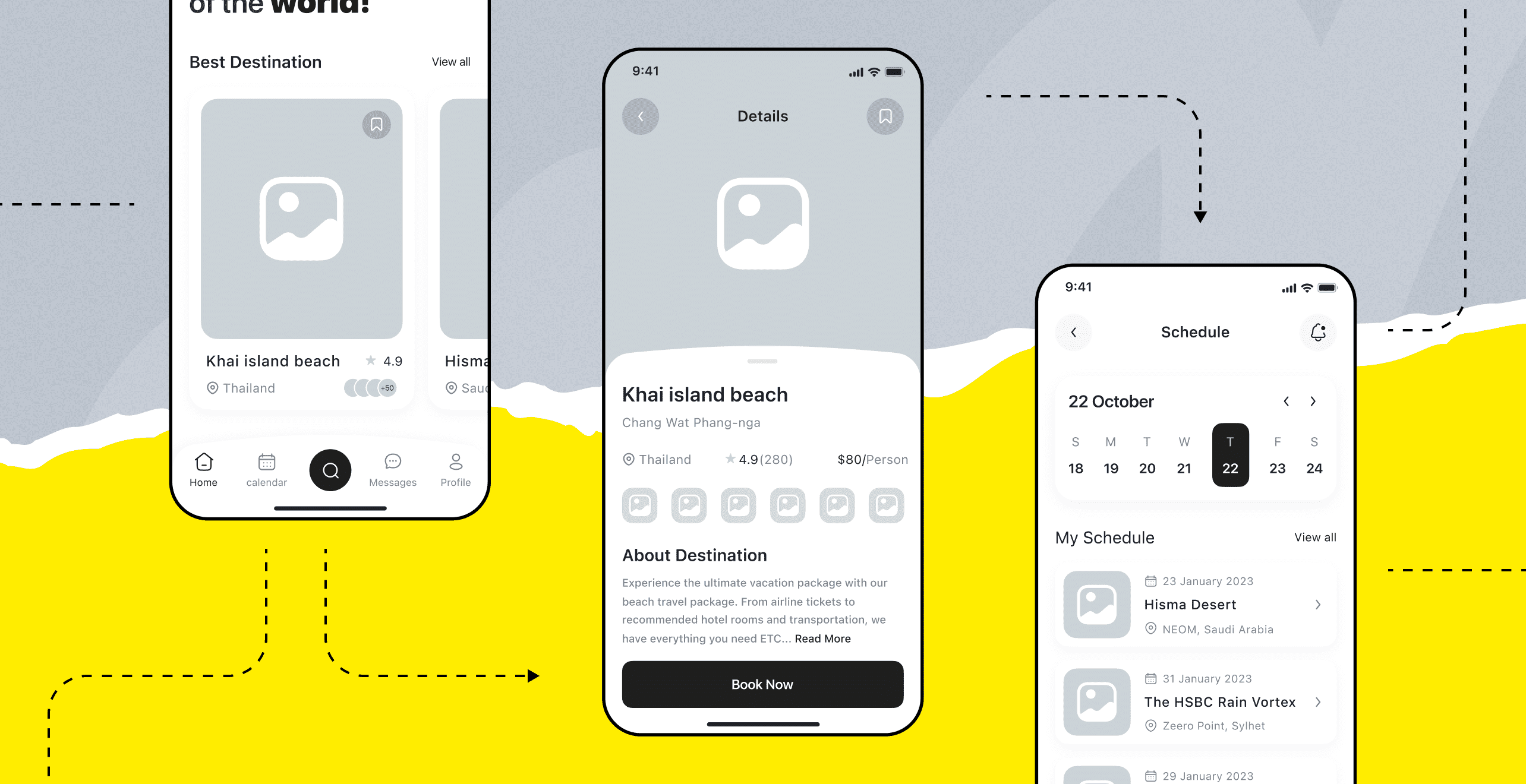

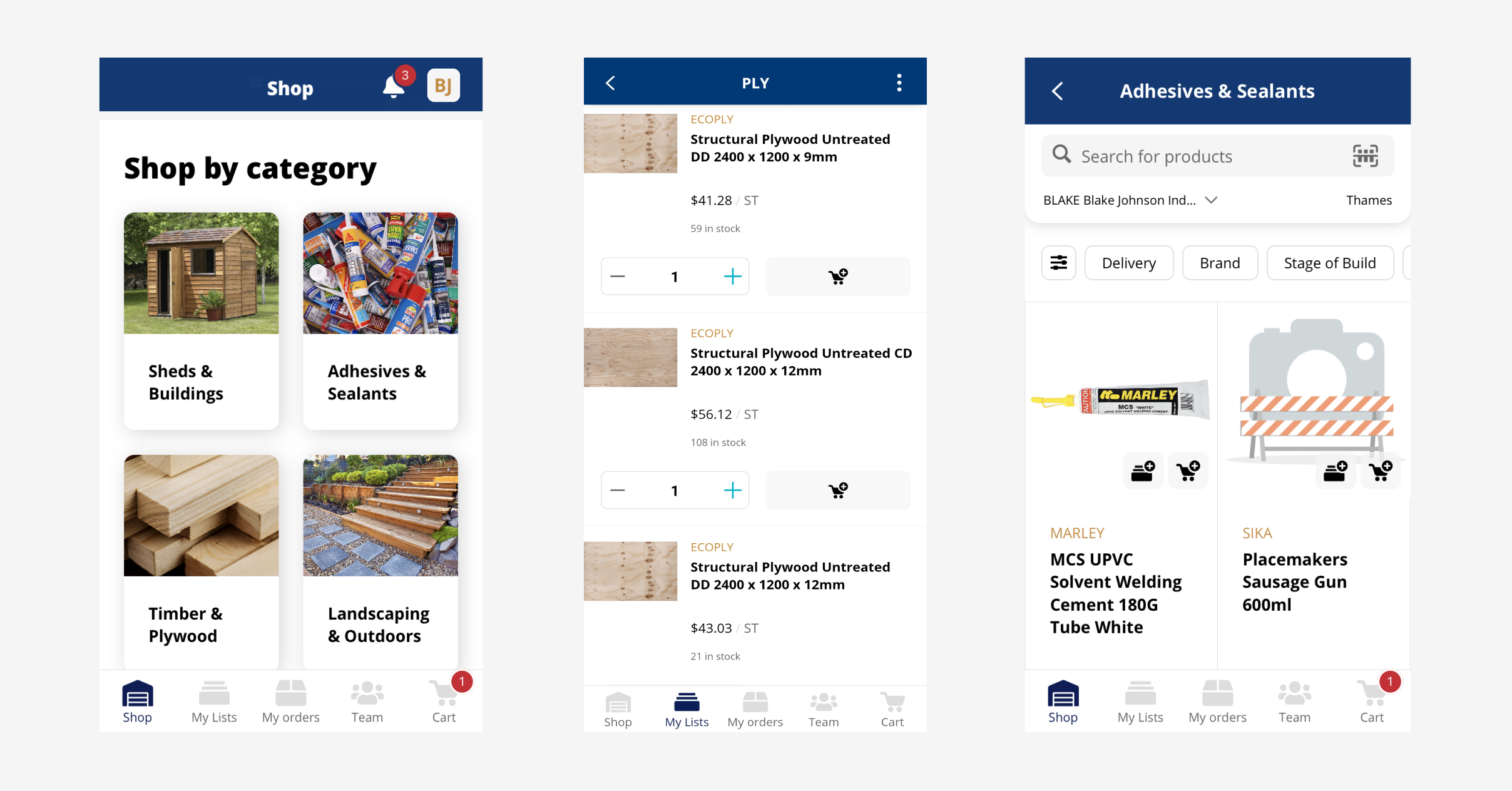

Take PlaceMakers , for example.

PlaceMakers faced challenges with their app during the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to supply chain shortages, stock levels were not being updated in real-time, causing customers to add unavailable products to their baskets. The team added a “Constrained Product” label, but this caused sales to plummet.

The team then turned to UXCam’s session replays and heatmaps to investigate, and hypothesized that their messaging for constrained products was too strong. The team redesigned the messaging with a more positive approach, and sales didn’t just recover—they doubled.

Types of product hypothesis

1. counter-hypothesis.

A counter-hypothesis is an alternative proposition that challenges the initial hypothesis. It’s used to test the robustness of the original hypothesis and make sure that the product development process considers all possible scenarios.

For instance, if the original hypothesis is “Reducing the sign-up steps from 3 to 1 will increase sign-ups by 25% for new visitors after 1,000 visits to the sign-up page,” a counter-hypothesis could be “Reducing the sign-up steps will not significantly affect the sign-up rate.

2. Alternative hypothesis

An alternative hypothesis predicts an effect in the population. It’s the opposite of the null hypothesis, which states there’s no effect.

For example, if the null hypothesis is “improving the page load speed on our mobile app will not affect the number of sign-ups,” the alternative hypothesis could be “improving the page load speed on our mobile app will increase the number of sign-ups by 15%.”

3. Second-order hypothesis

Second-order hypotheses are derived from the initial hypothesis and provide more specific predictions.

For instance, “if the initial hypothesis is Improving the page load speed on our mobile app will increase the number of sign-ups,” a second-order hypothesis could be “Improving the page load speed on our mobile app will increase the number of sign-ups.”

Why is a product hypothesis important?

Guided product development.

A product hypothesis serves as a guiding light in the product development process. In the case of PlaceMakers, the product owner’s hypothesis that users would benefit from knowing the availability of items upfront before adding them to the basket helped their team focus on the most critical aspects of the product. It ensured that their efforts were directed towards features and improvements that have the potential to deliver the most value.

Improved efficiency

Product hypotheses enable teams to solve problems more efficiently and remove biases from the solutions they put forward. By testing the hypothesis, PlaceMakers aimed to improve efficiency by addressing the issue of stock levels not being updated in real-time and customers adding unavailable products to their baskets.

Risk mitigation

By validating assumptions before building the product, teams can significantly reduce the risk of failure. This is particularly important in today’s fast-paced, highly competitive business environment, where the cost of failure can be high.

Validating assumptions through the hypothesis helped mitigate the risk of failure for PlaceMakers, as they were able to identify and solve the issue within a three-day period.

Data-driven decision-making

Product hypotheses are a key element of data-driven product development and decision-making. They provide a solid foundation for making informed, data-driven decisions, which can lead to more effective and successful product development strategies.

The use of UXCam's Session Replay and Heatmaps features provided valuable data for data-driven decision-making, allowing PlaceMakers to quickly identify the problem and revise their messaging approach, leading to a doubling of sales.

How to create a great product hypothesis

Map important user flows

Identify any bottlenecks

Look for interesting behavior patterns

Turn patterns into hypotheses

Step 1 - Map important user flows

A good product hypothesis starts with an understanding of how users more around your product—what paths they take, what features they use, how often they return, etc. Before you can begin hypothesizing, it’s important to map out key user flows and journey maps that will help inform your hypothesis.

To do that, you’ll need to use a monitoring tool like UXCam .

UXCam integrates with your app through a lightweight SDK and automatically tracks every user interaction using tagless autocapture. That leads to tons of data on user behavior that you can use to form hypotheses.

At this stage, there are two specific visualizations that are especially helpful:

Funnels : Funnels are great for identifying drop off points and understanding which steps in a process, transition or journey lead to success.

In other words, you’re using these two tools to define key in-app flows and to measure the effectiveness of these flows (in that order).

Average time to conversion in highlights bar.

Step 2 - Identify any bottlenecks

Once you’ve set up monitoring and have started collecting data, you’ll start looking for bottlenecks—points along a key app flow that are tripping users up. At every stage in a funnel, there’s going to be dropoffs, but too many dropoffs can be a sign of a problem.

UXCam makes it easy to spot dropoffs by displaying them visually in every funnel. While there’s no benchmark for when you should be concerned, anything above a 10% dropoff could mean that further investigation is needed.

How do you investigate? By zooming in.

Step 3 - Look for interesting behavior patterns

At this stage, you’ve noticed a concerning trend and are zooming in on individual user experiences to humanize the trend and add important context.

The best way to do this is with session replay tools and event analytics. With a tool like UXCam, you can segment app data to isolate sessions that fit the trend. You can then investigate real user sessions by watching videos of their experience or by looking into their event logs. This helps you see exactly what caused the behavior you’re investigating.

For example, let’s say you notice that 20% of users who add an item to their cart leave the app about 5 minutes later. You can use session replay to look for the behavioral patterns that lead up to users leaving—such as how long they linger on a certain page or if they get stuck in the checkout process.

Step 4 - Turn patterns into hypotheses

Once you’ve checked out a number of user sessions, you can start to craft a product hypothesis.

This usually takes the form of an “If… then…” statement, like:

“If we optimize the checkout process for mobile users, then more customers will complete their purchase.”

These hypotheses can be tested using A/B testing and other user research tools to help you understand if your changes are having an impact on user behavior.

Product hypothesis emphasizes the importance of formulating clear and testable hypotheses when developing a product. It highlights that a well-defined hypothesis can guide the product development process, align stakeholders, and minimize uncertainty.

UXCam arms product teams with all the tools they need to form meaningful hypotheses that drive development in a positive direction. Put your app’s data to work and start optimizing today— sign up for a free account .

You might also be interested in these;

Product experimentation framework for mobile product teams

7 Best AB testing tools for mobile apps

A practical guide to product experimentation

5 Best product experimentation tools & software

How to use data to challenge the HiPPO

Ardent technophile exploring the world of mobile app product management at UXCam.

Get the latest from UXCam

Stay up-to-date with UXCam's latest features, insights, and industry news for an exceptional user experience.

Related articles

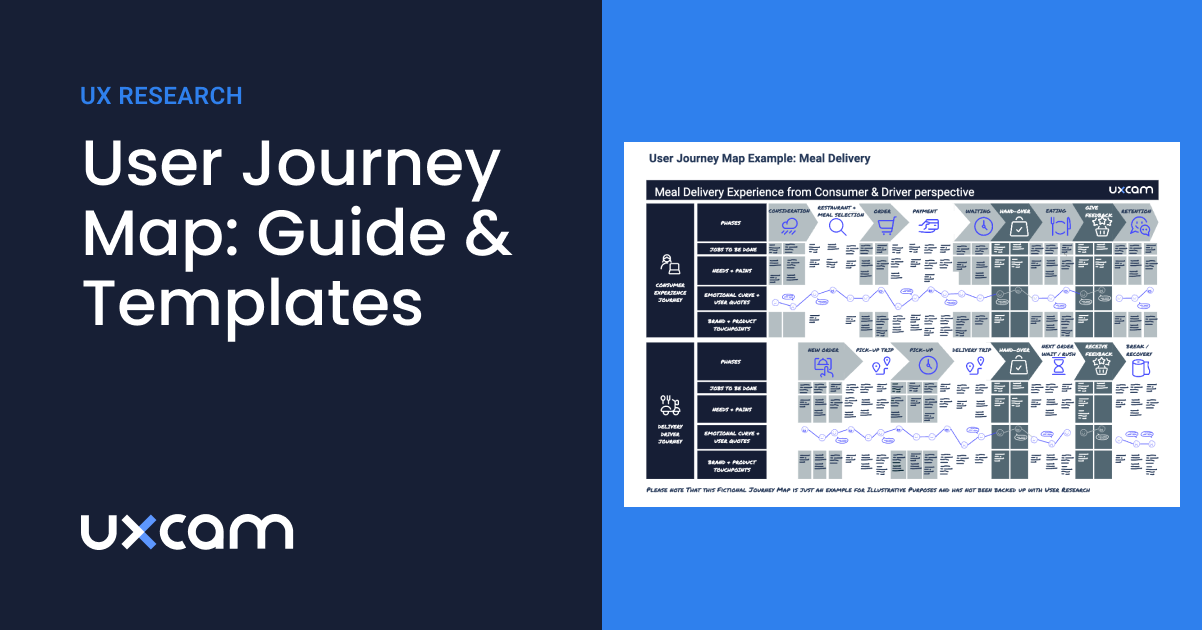

User Journey Map Guide with Examples & FREE Templates

Learn experience mapping basics and benefits using templates and examples with mixed-methods UX researcher Alice...

Alice Ruddigkeit

Senior UX Researcher

45 Mobile App Best Practices: The Ultimate List 2024

Proven best practices to improve user experience and performance of your mobile...

Jonas Kurzweg

Growth Lead

North Star Metric Examples from Tech Giants

Discover 9 North Star Metric examples to guide your business growth strategy, from user engagement to revenue, and align your team's...

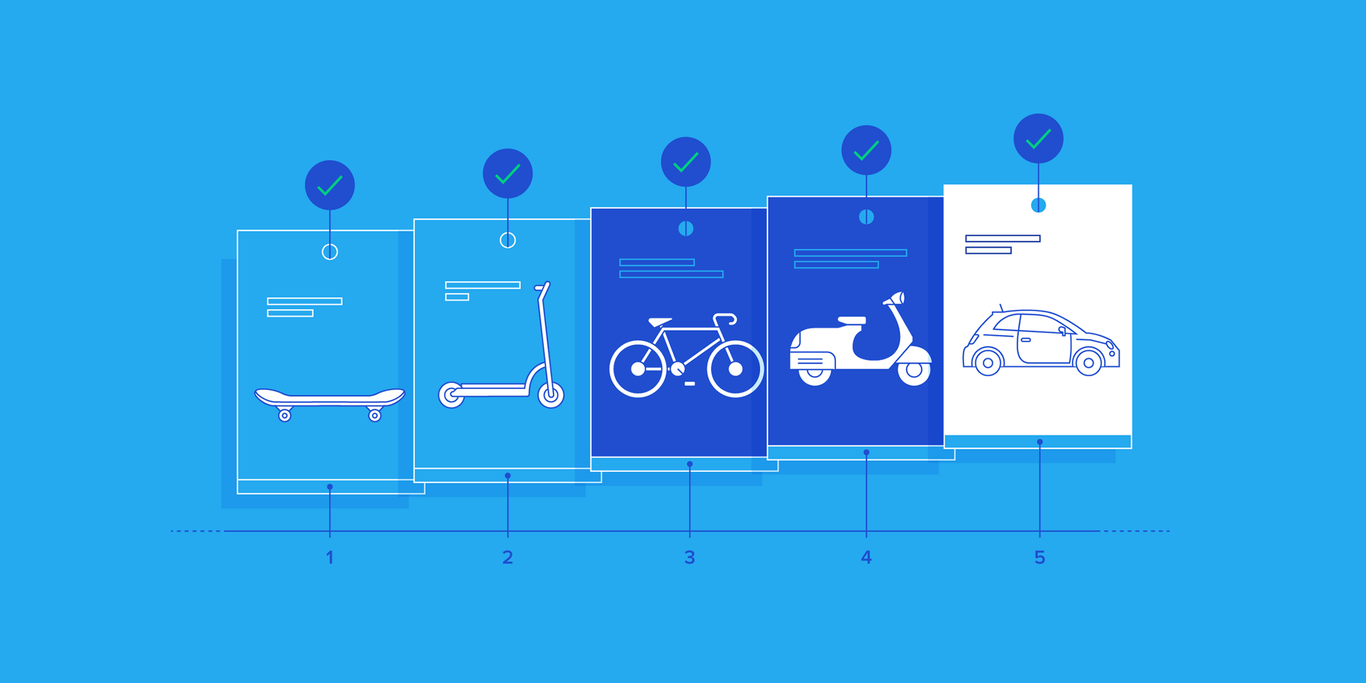

Shipping Your Product in Iterations: A Guide to Hypothesis Testing

Glancing at the App Store on any phone will reveal that most installed apps have had updates released within the last week. Software products today are shipped in iterations to validate assumptions and hypotheses about what makes the product experience better for users.

By Kumara Raghavendra

Kumara has successfully delivered high-impact products in various industries ranging from eCommerce, healthcare, travel, and ride-hailing.

PREVIOUSLY AT

A look at the App Store on any phone will reveal that most installed apps have had updates released within the last week. A website visit after a few weeks might show some changes in the layout, user experience, or copy.

Today, software is shipped in iterations to validate assumptions and the product hypothesis about what makes a better user experience. At any given time, companies like booking.com (where I worked before) run hundreds of A/B tests on their sites for this very purpose.

For applications delivered over the internet, there is no need to decide on the look of a product 12-18 months in advance, and then build and eventually ship it. Instead, it is perfectly practical to release small changes that deliver value to users as they are being implemented, removing the need to make assumptions about user preferences and ideal solutions—for every assumption and hypothesis can be validated by designing a test to isolate the effect of each change.

In addition to delivering continuous value through improvements, this approach allows a product team to gather continuous feedback from users and then course-correct as needed. Creating and testing hypotheses every couple of weeks is a cheaper and easier way to build a course-correcting and iterative approach to creating product value .

What Is Hypothesis Testing in Product Management?

While shipping a feature to users, it is imperative to validate assumptions about design and features in order to understand their impact in the real world.

This validation is traditionally done through product hypothesis testing , during which the experimenter outlines a hypothesis for a change and then defines success. For instance, if a data product manager at Amazon has a hypothesis that showing bigger product images will raise conversion rates, then success is defined by higher conversion rates.

One of the key aspects of hypothesis testing is the isolation of different variables in the product experience in order to be able to attribute success (or failure) to the changes made. So, if our Amazon product manager had a further hypothesis that showing customer reviews right next to product images would improve conversion, it would not be possible to test both hypotheses at the same time. Doing so would result in failure to properly attribute causes and effects; therefore, the two changes must be isolated and tested individually.

Thus, product decisions on features should be backed by hypothesis testing to validate the performance of features.

Different Types of Hypothesis Testing

A/b testing.

One of the most common use cases to achieve hypothesis validation is randomized A/B testing, in which a change or feature is released at random to one-half of users (A) and withheld from the other half (B). Returning to the hypothesis of bigger product images improving conversion on Amazon, one-half of users will be shown the change, while the other half will see the website as it was before. The conversion will then be measured for each group (A and B) and compared. In case of a significant uplift in conversion for the group shown bigger product images, the conclusion would be that the original hypothesis was correct, and the change can be rolled out to all users.

Multivariate Testing

Ideally, each variable should be isolated and tested separately so as to conclusively attribute changes. However, such a sequential approach to testing can be very slow, especially when there are several versions to test. To continue with the example, in the hypothesis that bigger product images lead to higher conversion rates on Amazon, “bigger” is subjective, and several versions of “bigger” (e.g., 1.1x, 1.3x, and 1.5x) might need to be tested.

Instead of testing such cases sequentially, a multivariate test can be adopted, in which users are not split in half but into multiple variants. For instance, four groups (A, B, C, D) are made up of 25% of users each, where A-group users will not see any change, whereas those in variants B, C, and D will see images bigger by 1.1x, 1.3x, and 1.5x, respectively. In this test, multiple variants are simultaneously tested against the current version of the product in order to identify the best variant.

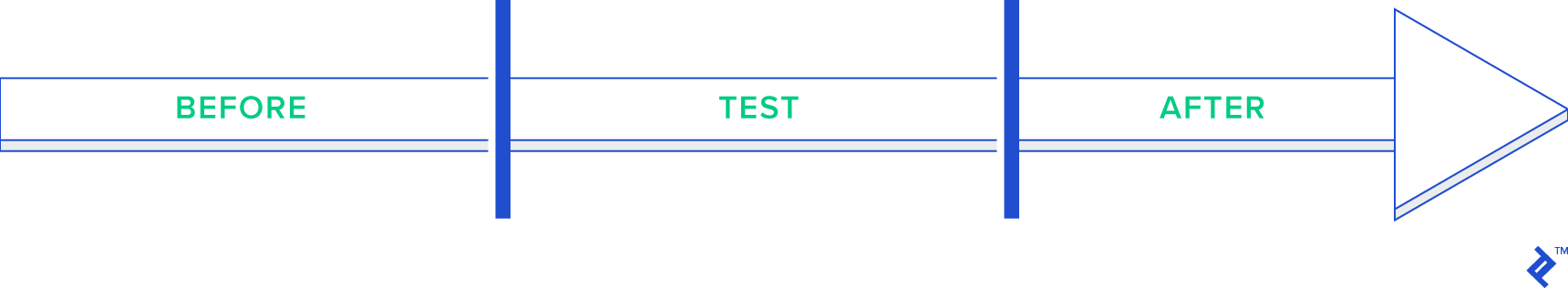

Before/After Testing

Sometimes, it is not possible to split the users in half (or into multiple variants) as there might be network effects in place. For example, if the test involves determining whether one logic for formulating surge prices on Uber is better than another, the drivers cannot be divided into different variants, as the logic takes into account the demand and supply mismatch of the entire city. In such cases, a test will have to compare the effects before the change and after the change in order to arrive at a conclusion.

However, the constraint here is the inability to isolate the effects of seasonality and externality that can differently affect the test and control periods. Suppose a change to the logic that determines surge pricing on Uber is made at time t , such that logic A is used before and logic B is used after. While the effects before and after time t can be compared, there is no guarantee that the effects are solely due to the change in logic. There could have been a difference in demand or other factors between the two time periods that resulted in a difference between the two.

Time-based On/Off Testing

The downsides of before/after testing can be overcome to a large extent by deploying time-based on/off testing, in which the change is introduced to all users for a certain period of time, turned off for an equal period of time, and then repeated for a longer duration.

For example, in the Uber use case, the change can be shown to drivers on Monday, withdrawn on Tuesday, shown again on Wednesday, and so on.

While this method doesn’t fully remove the effects of seasonality and externality, it does reduce them significantly, making such tests more robust.

Test Design

Choosing the right test for the use case at hand is an essential step in validating a hypothesis in the quickest and most robust way. Once the choice is made, the details of the test design can be outlined.

The test design is simply a coherent outline of:

- The hypothesis to be tested: Showing users bigger product images will lead them to purchase more products.

- Success metrics for the test: Customer conversion

- Decision-making criteria for the test: The test validates the hypothesis that users in the variant show a higher conversion rate than those in the control group.

- Metrics that need to be instrumented to learn from the test: Customer conversion, clicks on product images

In the case of the product hypothesis example that bigger product images will lead to improved conversion on Amazon, the success metric is conversion and the decision criteria is an improvement in conversion.

After the right test is chosen and designed, and the success criteria and metrics are identified, the results must be analyzed. To do that, some statistical concepts are necessary.

When running tests, it is important to ensure that the two variants picked for the test (A and B) do not have a bias with respect to the success metric. For instance, if the variant that sees the bigger images already has a higher conversion than the variant that doesn’t see the change, then the test is biased and can lead to wrong conclusions.

In order to ensure no bias in sampling, one can observe the mean and variance for the success metric before the change is introduced.

Significance and Power

Once a difference between the two variants is observed, it is important to conclude that the change observed is an actual effect and not a random one. This can be done by computing the significance of the change in the success metric.

In layman’s terms, significance measures the frequency with which the test shows that bigger images lead to higher conversion when they actually don’t. Power measures the frequency with which the test tells us that bigger images lead to higher conversion when they actually do.

So, tests need to have a high value of power and a low value of significance for more accurate results.

While an in-depth exploration of the statistical concepts involved in product management hypothesis testing is out of scope here, the following actions are recommended to enhance knowledge on this front:

- Data analysts and data engineers are usually adept at identifying the right test designs and can guide product managers, so make sure to utilize their expertise early in the process.

- There are numerous online courses on hypothesis testing, A/B testing, and related statistical concepts, such as Udemy , Udacity , and Coursera .

- Using tools such as Google’s Firebase and Optimizely can make the process easier thanks to a large amount of out-of-the-box capabilities for running the right tests.

Using Hypothesis Testing for Successful Product Management

In order to continuously deliver value to users, it is imperative to test various hypotheses, for the purpose of which several types of product hypothesis testing can be employed. Each hypothesis needs to have an accompanying test design, as described above, in order to conclusively validate or invalidate it.

This approach helps to quantify the value delivered by new changes and features, bring focus to the most valuable features, and deliver incremental iterations.

- How to Conduct Remote User Interviews [Infographic]

- A/B Testing UX for Component-based Frameworks

- Building an AI Product? Maximize Value With an Implementation Framework

Further Reading on the Toptal Blog:

- Evolving UX: Experimental Product Design with a CXO

- How to Conduct Usability Testing in Six Steps

- 3 Product-led Growth Frameworks to Build Your Business

- A Product Designer’s Guide to Competitive Analysis

Understanding the basics

What is a product hypothesis.

A product hypothesis is an assumption that some improvement in the product will bring an increase in important metrics like revenue or product usage statistics.

What are the three required parts of a hypothesis?

The three required parts of a hypothesis are the assumption, the condition, and the prediction.

Why do we do A/B testing?

We do A/B testing to make sure that any improvement in the product increases our tracked metrics.

What is A/B testing used for?

A/B testing is used to check if our product improvements create the desired change in metrics.

What is A/B testing and multivariate testing?

A/B testing and multivariate testing are types of hypothesis testing. A/B testing checks how important metrics change with and without a single change in the product. Multivariate testing can track multiple variations of the same product improvement.

Kumara Raghavendra

Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Member since August 6, 2019

About the author

World-class articles, delivered weekly.

By entering your email, you are agreeing to our privacy policy .

Toptal Product Managers

- Artificial Intelligence Product Managers

- Blockchain Product Managers

- Business Systems Analysts

- Cloud Product Managers

- Data Science Product Managers

- Digital Marketing Product Managers

- Digital Product Managers

- Directors of Product

- eCommerce Product Managers

- Enterprise Product Managers

- Enterprise Resource Planning Product Managers

- Freelance Product Managers

- Interim CPOs

- Jira Product Managers

- Kanban Product Managers

- Lean Product Managers

- Mobile Product Managers

- Product Consultants

- Product Development Managers

- Product Owners

- Product Portfolio Managers

- Product Strategy Consultants

- Product Tour Consultants

- Robotic Process Automation Product Managers

- Robotics Product Managers

- SaaS Product Managers

- Salesforce Product Managers

- Scrum Product Owner Contractors

- Web Product Managers

- View More Freelance Product Managers

Join the Toptal ® community.

Advisory boards aren’t only for executives. Join the LogRocket Content Advisory Board today →

- Product Management

- Solve User-Reported Issues

- Find Issues Faster

- Optimize Conversion and Adoption

How to write an effective hypothesis

Hypothesis validation is the bread and butter of product discovery. Understanding what should be prioritized and why is the most important task of a product manager. It doesn’t matter how well you validate your findings if you’re trying to answer the wrong question.

A question is as good as the answer it can provide. If your hypothesis is well written, but you can’t read its conclusion, it’s a bad hypothesis. Alternatively, if your hypothesis has embedded bias and answers itself, it’s also not going to help you.

There are several different tools available to build hypotheses, and it would be exhaustive to list them all. Apart from being superficial, focusing on the frameworks alone shifts the attention away from the hypothesis itself.

In this article, you will learn what a hypothesis is, the fundamental aspects of a good hypothesis, and what you should expect to get out of one.

The 4 product risks

Mitigating the four product risks is the reason why product managers exist in the first place and it’s where good hypothesis crafting starts.

The four product risks are assessments of everything that could go wrong with your delivery. Our natural thought process is to focus on the happy path at the expense of unknown traps. The risks are a constant reminder that knowing why something won’t work is probably more important than knowing why something might work.

These are the fundamental questions that should fuel your hypothesis creation:

Is it viable for the business?

Is it relevant for the user, can we build it, is it ethical to deliver.

Is this hypothesis the best one to validate now? Is this the most cost-effective initiative we can take? Will this answer help us achieve our goals? How much money can we make from it?

Has the user manifested interest in this solution? Will they be able to use it? Does it solve our users’ challenges? Is it aesthetically pleasing? Is it vital for the user, or just a luxury?

Do we have the resources and know-how to deliver it? Can we scale this solution? How much will it cost? Will it depreciate fast? Is it the best cost-effective solution? Will it deliver on what the user needs?

Is this solution safe both for the user and for the business? Is it inclusive enough? Is there a risk of public opinion whiplash? Is our solution enabling wrongdoers? Are we jeopardizing some to privilege others?

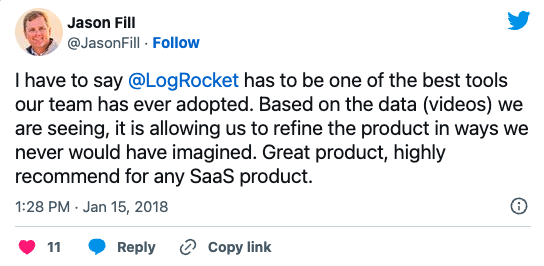

Over 200k developers and product managers use LogRocket to create better digital experiences

There is an infinite amount of questions that can surface from these risks, and most of those will be context dependent. Your industry, company, marketplace, team composition, and even the type of product you handle will impose different questions, but the risks remain the same.

How to decide whether your hypothesis is worthy of validation

Assuming you came up with a hefty batch of risks to validate, you must now address them. To address a risk, you could do one of three things: collect concrete evidence that you can mitigate that risk, infer possible ways you can mitigate a risk and, finally, deep dive into that risk because you’re not sure about its repercussions.

This three way road can be illustrated by a CSD matrix :

Certainties

Suppositions.

Everything you’re sure can help you to mitigate whatever risk. An example would be, on the risk “how to build it,” assessing if your engineering team is capable of integrating with a certain API. If your team has made it a thousand times in the past, it’s not something worth validating. You can assume it is true and mark this particular risk as solved.

To put it simply, a supposition is something that you think you know, but you’re not sure. This is the most fertile ground to explore hypotheses, since this is the precise type of answer that needs validation. The most common usage of supposition is addressing the “is it relevant for the user” risk. You presume that clients will enjoy a new feature, but before you talk to them, you can’t say you are sure.

Doubts are different from suppositions because they have no answer whatsoever. A doubt is an open question about a risk which you have no clue on how to solve. A product manager that tries to mitigate the “is it ethical to deliver” risk from an industry that they have absolute no familiarity with is poised to generate a lot of doubts, but no suppositions or certainties. Doubts are not good hypothesis sources, since you have no idea on how to validate it.

A hypothesis worth validating comes from a place of uncertainty, not confidence or doubt. If you are sure about a risk mitigation, coming up with a hypothesis to validate it is just a waste of time and resources. Alternatively, trying to come up with a risk assessment for a problem you are clueless about will probably generate hypotheses disconnected with the problem itself.

That said, it’s important to make it clear that suppositions are different from hypotheses. A supposition is merely a mental exercise, creativity executed. A hypothesis is a measurable, cartesian instrument to transform suppositions into certainties, therefore making sure you can mitigate a risk.

How to craft a hypothesis

A good hypothesis comes from a supposed solution to a specific product risk. That alone is good enough to build half of a good hypothesis, but you also need to have measurable confidence.

More great articles from LogRocket:

- How to implement issue management to improve your product

- 8 ways to reduce cycle time and build a better product

- What is a PERT chart and how to make one

- Discover how to use behavioral analytics to create a great product experience

- Explore six tried and true product management frameworks you should know

- Advisory boards aren’t just for executives. Join LogRocket’s Content Advisory Board. You’ll help inform the type of content we create and get access to exclusive meetups, social accreditation, and swag.

You’ll rarely transform a supposition into a certainty without an objective. Returning to the API example we gave when talking about certainties, you know the “can we build it” risk doesn’t need validation because your team has made tens of API integrations before. The “tens” is the quantifiable, measurable indication that gives you the confidence to be sure about mitigating a risk.

What you need from your hypothesis is exactly this quantifiable evidence, the number or hard fact able to give you enough confidence to treat your supposition as a certainty. To achieve that goal, you must come up with a target when creating the hypothesis. A hypothesis without a target can’t be validated, and therefore it’s useless.

Imagine you’re the product manager for an ecommerce app. Your users are predominantly mobile users, and your objective is to increase sales conversions. After some research, you came across the one click check-out experience, made famous by Amazon, but broadly used by ecommerces everywhere.

You know you can build it, but it’s a huge endeavor for your team. You best make sure your bet on one click check-out will work out, otherwise you’ll waste a lot of time and resources on something that won’t be able to influence the sales conversion KPI.

You identify your first risk then: is it valuable to the business?

Literature is abundant on the topic, so you are almost sure that it will bear results, but you’re not sure enough. You only can suppose that implementing the one click functionality will increase sales conversion.

During case study and data exploration, you have reasons to believe that a 30 percent increase of sales conversion is a reasonable target to be achieved. To make sure one click check-out is valuable to the business then, you would have a hypothesis such as this:

We believe that if we implement a one-click checkout on our ecommerce, we can grow our sales conversion by 30 percent