- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Book of the day You Are Here by David Nicholls review – love is in the fresh air

Thrillers of the month Crime and thrillers of the month – review

Memoir Knife by Salman Rushdie review – a story of hatred defeated by love

‘why didn’t i fight why didn’t i run’ 10 things we learned from salman rushdie’s knife.

The big idea The big idea: are we about to discover a new force of nature?

Carol Rumens's poem of the week Poem of the week: Sea Rose by HD

Book of the day Travels Over Feeling: Arthur Russell, a Life review – down the rabbit hole with a musical maverick

Fiction Mania by Lionel Shriver review – we need to talk about stupidity

- All stories

Books of the year

Books of the year The best books of 2023

2023 in Culture The best books to give as presents this Christmas

Alison flood’s best crime novels and thrillers of 2023, rachel cooke’s best graphic novels of 2023, what to read.

Paperbacks This month’s best paperbacks: Anne Enright, Sarah Bernstein and more

Five of the best Five of the best books about siblings

100 best novels of all time From The Pilgrim's Progress to True History of the Kelly Gang

The 100 best books of the 21st century

100 best nonfiction books of all time From Naomi Klein to the Bible – the full list

Non-fiction reviews.

History books An African History of Africa by Zeinab Badawi review – an insider’s take

Autobiography and memoir A Body Made of Glass by Caroline Crampton review – anatomy of hypochondria

Biography books Spinoza: Freedom’s Messiah by Ian Buruma review – a man of his time… and ours

Autobiography and memoir The Half Bird by Susan Smillie review – a life less ordinary

History books Nostalgia: A History of a Dangerous Emotion by Agnes Arnold-Forster review – no place like home

Politics books head north by andy burnham and steve rotheram review – northern mayors’ manifesto for hope.

Society books A Necessary Kindness by Juno Carey review – demystifying abortion: an insider’s account of its long and painful history

Fiction & poetry reviews.

Science fiction roundup The best recent science fiction, fantasy and horror – reviews roundup

Fiction Hagstone by Sinéad Gleeson review – portrait of an artist

Poetry Crystal by Ellen Cranitch review – a devastating insight into drug dependency

Fiction Levitation for Beginners by Suzannah Dunn review – the dark side of a 70s childhood

Fiction james by percival everett review – a gripping reimagining of huckleberry finn.

Fiction Dead Animals by Phoebe Stuckes review – a searing ‘sad girl’ tale

Fiction Hagstone by Sinéad Gleeson review – art, solitude and the supernatural

Children's and ya books.

Children's book reviews round-up Picture books for children – reviews

Children's book roundup The best new picture books and novels

Children's book reviews round-up Young adult books roundup – reviews

‘I’d love a scathing review’ Novelist Percival Everett on American Fiction and rewriting Huckleberry Finn

Michael Magee There’s a disbelief at how I’ve ended up

‘I will defeat Richard Osman!’ Holly Jackson on being Britain’s top selling female crime author

Helen garner people would give me death stares in the street.

Liu Cixin I’m often asked – there’s science fiction in China?

Mat Osman I wanted to write about a real London – dirty, dangerous, working class

Barbi Marković The real horror story is life itself

The books of my life Marian Keyes: ‘Books have one shot to impress me and if you miss, you miss’

Big idea the big idea: are we about to discover a new force of nature.

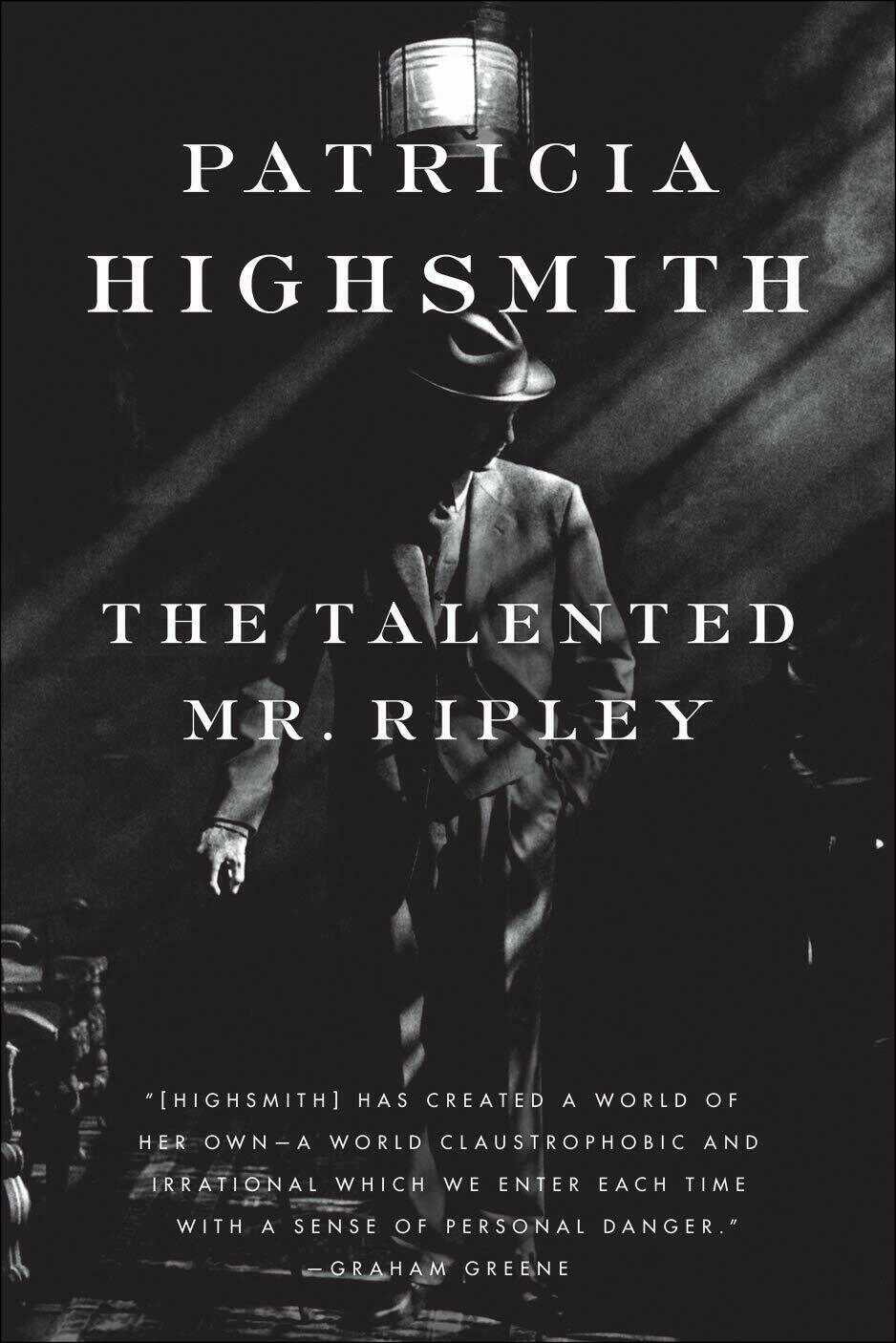

Where to start with Where to start with: Patricia Highsmith

You may have missed.

Sad girl novels The dubious branding of women’s emotive fiction

‘She was like an auntie to me’ Lynne Reid Banks remembered by Michael Morpurgo

Obituaries lynne reid banks, news lynne reid banks, author of the indian in the cupboard, dies aged 94.

Cloud Atlas at 20 What makes a novel tattoo-worthy?

Edinburgh international book festival Event announces ‘relaunch’ as sponsor row remains unresolved

Most viewed, most viewed in books, most viewed across the guardian, you are here by david nicholls review – love is in the fresh air, crime and thrillers of the month – review, ‘why didn’t i fight why didn’t i run’: 10 things we learned from salman rushdie’s knife, the big idea: are we about to discover a new force of nature, poem of the week: sea rose by hd, knife by salman rushdie review – a story of hatred defeated by love, mania by lionel shriver review – we need to talk about stupidity, five of the best psychological thrillers by women, ‘so it’s you. here you are’: salman rushdie describes moment he was stabbed, the 100 best books of the 21st century, live middle east crisis live: israel’s war cabinet to meet again to discuss response to iran’s attack, europe live: scores of emergency workers fight fire at copenhagen’s old stock exchange – as it happened, conman who swindled $175m in ‘massive’ psychic fraud scheme sentenced to 10 years, undersea ‘hybrid warfare’ threatens security of 1bn, nato commander warns, beijing half marathon hit by controversy as china’s he jie allowed to win, astronomers discover milky way’s biggest stellar black hole – 33 times size of sun, live russia-ukraine war live: kyiv says it ‘ran out of missiles’ to stop russian strike on power plant, liz truss has kindly offered to ‘save the west’. but who will save her from her delusions, at 50, i had a flashback to a priest abusing me as a child. then i decided to confront him, live natcon conference continues in brussels after police leave without enforcing closure – uk politics live.

- Autobiography and memoir

- Biography books

- Crime fiction

- Salman Rushdie

The best recent thrillers – review roundup

A brilliant slice of suburban nightmare, a tense airborne drama and the return of India’s first female detective, Persis Wadia

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share via Email

Good Neighbours

Sarah Langan Titan Books, £8.99, pp304

Maple Street is a picture-perfect, crescent-shaped block bordering a park on Long Island, New York. Its inhabitants are the sort of people who “dressed for work in business casual”, who channel everything into their kids, who are “obsessed with college. Harvard in particular”. Newcomers the Wildes are different. Father, Arlo, is a former rocker, mother, Gertie, has never been told “that mom cleavage isn’t cool”, while the kids, Julia and Larry, “made fart sounds in public, and also farted in public”. When a sinkhole opens in the park, and the daughter of neighbourhood matriarch Rhea falls in, something very dark begins circulating in Maple Street, and the Wildes watch as tensions mount against them. Langan, who has won awards for her horror novels in the past, draws the dread at the heart of Good Neighbours from the terrible things people do to one another, and from what might lie in wait for a child at the bottom of a sinkhole, or in their bedroom. “The children of Maple Street were skittering over the surface of something dangerous. One of them was about to fall in.” A brilliant slice of suburban nightmare.

The Night She Disappeared

Lisa Jewell Century, £14.99, pp480

As Kim babysits her grandson, Noah, daughter Tallulah, a young mother at 19, has gone for a rare evening out with her boyfriend Zach. They don’t come home, and as the hours, the days and then the weeks pass, Kim fights for her daughter’s disappearance to be taken seriously. A year later, crime novelist Sophie arrives in the Surrey hills at nearby private school Maypole House with her boyfriend, Shaun, the new headmaster. She finds a sign in her back garden reading “dig here”, and is drawn into the mystery of Tallulah and Zach’s disappearance, channelling the detective skills of her fictional sleuths. Sophie is a fine companion with whom to solve this thorny mystery, while Jewell gives tender glimpses into the life of teenage mother Tallulah, and her deep love for the baby boy Kim is adamant she wouldn’t abandon, as she shifts her story back and forth in time. Gripping and satisfying, this had me in tears at the end.

Clare Mackintosh Sphere, £14.99, pp400

Flight attendant Mina is told that her young daughter Sophia will die unless she allows a terrorist to enter the cockpit of her plane. Mina is on board an inaugural non-stop flight from London to Sydney, a job she has wrangled her way on to in order to forget her troubled marriage to policeman Adam. There are 353 people on board, and Mackintosh moves between the perspective of Mina, fraught, terrified, with a terrible decision to make, and that of Adam at home, with secrets of his own. We also hear from various passengers – celebrities, journalists, new mothers and fathers. “I am surrounded by parents, grandparents, children,” writes a reporter aboard the aircraft. “The families of these passengers will no doubt struggle to understand why their loved ones’ lives should be worth less than one woman’s child.” Mackintosh builds Mina’s dilemma into a rip-roaring finale.

The Dying Day

Vaseem Khan Hodder & Stoughton, £16.99, pp352

Khan returns to the world of post-independence India in 1950s Bombay, and to the travails of India’s first female police detective, Persis Wadia, in the second in this excellent series. This time, Wadia is out to find a priceless artefact, a 600-year-old copy of Dante’s The Divine Comedy , which has gone missing from the Asiatic Society along with the scholar who was studying it. Fortunately for Persis, and for Khan’s readers, a series of cryptic clues have been left behind, and she sets to work solving them with her sidekick Archie Blackfinch, an English forensics expert. Wadia, who is not only contending with a dangerous mystery with links to fascism but also a general lack of respect from her male counterparts, is as tough and no-nonsense as she was in her debut appearance, Midnight at Malabar House . This is even more enjoyable – a delicious treat of a historical crime novel.

• To order Good Neighbours , The Night She Disappeared , Hostage , or The Dying Day and support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com . Delivery charges may apply

{{topLeft}}

{{bottomLeft}}

{{topRight}}

{{bottomRight}}

{{heading}}

- Thrillers of the month

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on WhatsApp

- Share on Messenger

{{#isVideo}} {{/isVideo}}{{#isGallery}} {{/isGallery}}{{#isAudio}} {{/isAudio}} {{#isComment}} {{/isComment}} {{headline}}

- {{ title }}

- Sign in / Register

Switch edition

- {{ displayName }}

Marjorie Taylor Greene's New Book Reads Like 1 Thing, Says Searing Guardian Review

Reporter, HuffPost

A new book by far-right Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.) “duly reads like an audition for the No 2 slot on the 2024 Republican presidential ticket,” according to a scathing review published by Britain’s Guardian newspaper.

“Venom, score-settling, fiction, self-absolution, self-aggrandizement. Greene’s book, ‘MTG,’ has it all,” former Justice Department attorney Lloyd Green wrote in the critique , published Sunday.

Greene toadies up to former president and Republican 2024 front-runner Donald Trump , lies about the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, “embraces the insurrectionists who attacked Congress,” and “offers a meandering defense of her famous comment about so-called Jewish space lasers, insisting she is not antisemitic,” says the reviewer.

Despite promising to tell her “side of the story” in the Canada-printed memoir, the lawmaker does not directly address some of her most controversial moments, such as when her support of the idea of executing Democrats saw her stripped of House committee assignments, Green notes.

“Under Trump, retribution and vengeance are Republicans ’ fuel. Greene wants to sit at his right hand,” Green concluded his review of the book, which was released by the Donald Trump Jr. -founded Winning Team Publishing.

Critics on social media, meanwhile, have suggested another use for the tome.

Read the full review here .

Support HuffPost

Our 2024 coverage needs you, your loyalty means the world to us.

At HuffPost, we believe that everyone needs high-quality journalism, but we understand that not everyone can afford to pay for expensive news subscriptions. That is why we are committed to providing deeply reported, carefully fact-checked news that is freely accessible to everyone.

Whether you come to HuffPost for updates on the 2024 presidential race, hard-hitting investigations into critical issues facing our country today, or trending stories that make you laugh, we appreciate you. The truth is, news costs money to produce, and we are proud that we have never put our stories behind an expensive paywall.

Would you join us to help keep our stories free for all? Your contribution of as little as $2 will go a long way.

Can't afford to donate? Support HuffPost by creating a free account and log in while you read.

As Americans head to the polls in 2024, the very future of our country is at stake. At HuffPost, we believe that a free press is critical to creating well-informed voters. That's why our journalism is free for everyone, even though other newsrooms retreat behind expensive paywalls.

Our journalists will continue to cover the twists and turns during this historic presidential election. With your help, we'll bring you hard-hitting investigations, well-researched analysis and timely takes you can't find elsewhere. Reporting in this current political climate is a responsibility we do not take lightly, and we thank you for your support.

Contribute as little as $2 to keep our news free for all.

Dear HuffPost Reader

Thank you for your past contribution to HuffPost. We are sincerely grateful for readers like you who help us ensure that we can keep our journalism free for everyone.

The stakes are high this year, and our 2024 coverage could use continued support. Would you consider becoming a regular HuffPost contributor?

The stakes are high this year, and our 2024 coverage could use continued support. If circumstances have changed since you last contributed, we hope you’ll consider contributing to HuffPost once more.

Already contributed? Log in to hide these messages.

Popular in the Community

From our partner, more in politics.

Advertisement

More from the Review

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Best of The New York Review, plus books, events, and other items of interest

- The New York Review of Books: recent articles and content from nybooks.com

- The Reader's Catalog and NYR Shop: gifts for readers and NYR merchandise offers

- New York Review Books: news and offers about the books we publish

- I consent to having NYR add my email to their mailing list.

- Hidden Form Source

April 18, 2024

Current Issue

Two Centuries of ‘The Guardian’

May 27, 2021 issue

Katy Stoddard

Alan Rusbridger, then editor of The Guardian , addressing the newsroom after the paper won the Pulitzer Prize for its reporting on the documents leaked by Edward Snowden, London, April 2014

Submit a letter:

Email us [email protected]

The Guardian has never been much of a business. Its owners never got rich; in fact, they gave the newspaper away. Its history is peppered with financial crises and near-death experiences. Perhaps it was placed on earth to make “righteousness readable” (in the centenary words of Lord Robert Cecil), but the paper has nearly always struggled to make it remunerative.

And yet this year it is celebrating its two hundredth anniversary. Born on the day Napoleon Bonaparte died—May 5, 1821— The Guardian now has around $1.4 billion in the bank, more than a million paying supporters or subscribers, and profitable operations in the US and Australia, which enable it to report around the clock and to reach well over 1.5 billion online readers around the world every year. Not bad for a paper that began life being cranked out on a primitive handpress at 125 copies an hour.

The 750 journalists who work at The Guardian today can reflect that their predecessors eventually got around to reporting the death of Napoleon nearly two months later and recorded the celebrations for the coronation of George IV the same year. The paper had a man on the spot to capture in perhaps too much graphic detail the death throes of William Huskisson, a member of Parliament taken unawares in 1830 by the speed of the engineer George Stephenson’s Rocket steam locomotive. (“Lord Wilson put a handkerchief round the mangled limb and twisted it with a stick to form a tourniquet for the purpose of stopping the effusion of blood.”) It had a ringside seat for the great struggle for parliamentary reform in 1832 and backed Prime Minister William Gladstone’s Home Rule for Ireland campaign fifty-odd years later.

In 1887 the paper’s features (“colour”) writer attended Queen Victoria’s garden party in celebration of her fifty years on the throne and made a note of her “swimming, sweeping gait.” One of its reporters was on the beach at Gallipoli in 1915, another made it to Dublin in time for the climax of the Easter Rising the following year, and yet another was at the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg in December 1917 when it was stormed by the Bolsheviks. Its correspondent conducted a day-long interview with Leo Tolstoy in 1905. (“Russian ladies nowadays write excellently…only, they have nothing to say.”) Lenin granted a somewhat shorter interview in 1919.

The Guardian saw Niccolò Paganini perform in Manchester in 1832 and Henry Irving play Charles I in 1873. Its music critic watched from the wings as Richard Wagner rehearsed his singers for the first Bayreuth Festival in 1876. The paper’s critics were still puzzled by Gustav Mahler in 1920 but impressed by Sergei Eisenstein’s silent film Battleship Potemkin when it was shown in the UK in 1929. After seeing a Luigi Pirandello play on a prototype Baird television set in August 1930, its drama critic was reluctant to write the medium off altogether.

Its reporter C.B. Marriott sent dispatches from the Paris Commune siege in 1871. J.M. Synge wrote on Irish poverty in 1905, Arthur Ransome on famine in the Volga region in 1921, F.A. Voigt on the rise of fascism in March 1933, and Martha Gellhorn on Vietnam in 1966. When Neville Chamberlain pronounced peace with honor in October 1938, The Guardian didn’t believe him.

The paper has, in other words, seen a lot, and has had a lot to say.

The original investors were not in it for a quick buck: indeed, they were quite ready to lose their seed capital. They came together to start a newspaper because they felt that Manchester—a city built on the growth of the cotton industry, powered by new factories and mills, and gripped by the hunger for political reform—needed one, even though it already had at least five.

A clue to their motives can be found in the Peterloo Massacre of August 16, 1819. Eighteen people were killed and as many as 670 were injured when the cavalry, encouraged by the local Manchester magistrates, charged into a crowd of working-class protesters peacefully demanding greater political representation.

How public opinion was formed in 1819 was not so different from the present day. There were widely conflicting accounts of what had happened, with the magistrates keen to promote their version through the press and the courts: that their forces had come under attack from a violent mob. They were not short of newspapers that would put political interests above the truth.

Whom to believe? John Edward Taylor, a prominent cotton merchant and civic leader, was in the crowd that day and predicted the tide of propaganda, which began with the magistrates sending false accounts to the Home Office. He also knew The Times ’s correspondent, John Tyas, was in custody and unable to file a report. So he wrote a hurried account himself and got it on the mail coach to London. It was published on August 18. It is fascinating to read The Times over the subsequent days, as the paper’s great editor, Thomas Barnes, attempted to establish a common foundation of evidence for what had happened. He used what we might now call crowd-sourcing (“I was there”) and aggregation (“here’s the Liverpool Mercury and the Manchester Herald account”) to build up a kaleidoscope of eyewitness testimony. It was, in the end, overwhelmingly supportive of Taylor’s account.

The historian E.P. Thompson later described this battle for truth as one between the “OK witness” (i.e., bishops and generals) and the “non-OK witnesses” (i.e., working-class). Thanks in large part to Taylor, Tyas, and The Times , the non-OK side eventually triumphed. Thompson’s judgment, written in 1957, was that “never since Peterloo has authority dared to use equal violence on a peaceful British crowd.” Peterloo, according to The Guardian ’s centenary historian and chief reporter, William Haslam Mills, marked “the début of the reporter in English public life.” 1

About eighteen months later Taylor hatched a plan to launch The Manchester Guardian . The dozen founders were all Nonconformists (Protestants outside the Church of England), and at least ten were Unitarians (a church linked with social reform). Most were liberal campaigners, although connected with the cotton trade. Each contributed £100 (around $15,000 in today’s currency). If the paper succeeded, their investment would be repaid; if it failed, they would write off their losses. Sophia Russell Scott, Taylor’s future wife, wrote to her brother, Russell: “Their view was public advantage. They were willing to take the risk without wishing to have any share in the profits.”

The first edition—a four-page folio—carried a stamp to indicate compliance with the four-penny tax then levied on all newspapers (there was an additional tax of three shillings and six pence on each of the forty-seven advertisements). The stamp duty “tax on knowledge” deliberately put newspapers beyond the means of anyone but the elite, but they were passed from hand to hand and read aloud at large public meetings. Each copy might be devoured by as many as thirty people.

It seems clear that in starting The Guardian , Taylor had two aims: to bear reliable witness in a world of information confusion and to shape views. “A newspaper in that age had much soul and very little substance,” wrote Mills in the centenary history. “It was most probably established, not to make money, but to make opinion. It had something to say but very little to tell. It thought much more than it knew.”

Twin purposes, but not to be muddled. “Comment is free, but facts are sacred,” The Guardian ’s greatest editor, C.P. Scott, pronounced one hundred years after its birth. Over that period the paper had built up a reputation for both fair and, at times, fearless reporting alongside the influencing of opinion. Then as now, it was important to distinguish between the two.

One of the first hires was Jeremiah Garnett, whose skills included printing, reporting, and, later, editing. Another early hire was John Harland, of the Hull Packet , who for thirty years used his formidable proficiency at shorthand to record political speeches. For the first time in history a wide public could read verbatim accounts of the main agitators for—and against—political reform.

The paper may have been born in an age of radical ferment—some feared a revolution because of dissatisfaction with Parliament, which was riddled with “rotten boroughs” having virtually no voters, and just 2 percent of the population had the vote—but its politics, at least in its early days, remained what Mills termed “studiously moderate and opportunistic.” Its centrist views (doubtless trimmed so as not to alienate the new cotton middle class) sometimes managed to offend Tories as well as Radicals (supporters of parliamentary reform), but it was successful in attracting a broad readership. By 1840 the paper was the market leader in Manchester and the third-biggest provincial paper in the UK, but it dismayed those seeking more reforming fire and campaigning edge.

The paper initially fared well financially. Advertising flooded in. There are purists who deplore the (until recently) overwhelming dependence of newspapers on advertising, but they forget that—as the press historian Francis Williams wrote in 1957—“the daily press would never have come into existence as a force in public and social life if it had not been for the need of men of commerce to advertise.” The Guardian and newspapers like it published small ads on the front page, which bought them, at last, independence from political parties. The ads also meant that Taylor could repay the original investors, with interest.

In 1824 Taylor married Sophia, his first cousin. The bond between their families was further strengthened with the appointment of Sophia’s twenty-five-year-old nephew, C.P. Scott, as editor of the paper in 1872. By the time he retired fifty-seven years later, Scott had become a towering figure in local, national, and international journalism. He had also become his own proprietor, having purchased the paper along with the consistently profitable Manchester Evening News (using his own personal means and borrowed money) in 1907.

Whether as owner or editor, Scott never doubted that the editorial imperative trumped any commercial considerations. His centenary essay was clear:

A newspaper has two sides to it. It is a business, like any other, and has to pay in the material sense in order to live. But it is much more than a business; it is an institution; it reflects and it influences the life of a whole community; it may affect even wider destinies…. It may educate, stimulate, assist, or it may do the opposite. It has, therefore, a moral as well as a material existence, and its character and influence are in the main determined by the balance of these two forces. It may make profit or power its first object, or it may conceive itself as fulfilling a higher and more exacting function. I think I may honestly say that, from the day of its foundation, there has not been much doubt as to which way the balance tipped…. Had it not been so, personally I could not have served it.

In a speech on his eightieth birthday, in 1926, Scott underlined these priorities, describing a newspaper as “a public-utility service…essential to the interests of the public.”

Six years later Scott was dead. Within four months, his forty-eight-year-old son, Ted, who had briefly succeeded him as editor, drowned while sailing. C.P.’s third child, J.R., now manager of the family business, placed the two papers into a trust—the Scott Trust, formally established in 1936 (and reconstituted in 1948, and again in 2008).

In effectively giving away the paper, J.R. Scott prevented it from being snapped up by a press baron such as Lord Beaverbrook or Lord Northcliffe. For the rest of his working life he drew only a normal salary. “He could have been a rich man,” wrote Sir William Haley, later the editor of The Times . “He chose a Spartan existence.” (Not everyone approved of this singular act of philanthropy. Gavin Simonds, the future Lord Chancellor, who was advising Scott, told him, “It seems to me that you are trying to do something very repugnant to the law of England. You are trying to divest yourself of a property right.”)

The sole official object of the Scott Trust, which continues to own The Guardian (and still has a Scott on its board), is that the newspaper “shall be conducted in the future on the same lines and in the same spirit as heretofore.” Since 1936, that is the only instruction given to incoming editors (of which there have, since that date, been just six): “As heretofore.”

Numerous books have been written about newspaper proprietors, from William Randolph Hearst, Joseph Pulitzer, and Edward Scripps to Lord Northcliffe, Robert Maxwell, and Rupert Murdoch. Less examined is what it means for journalists not to have one. What if no one is telling you what to write, or whom not to offend?

Editors with no proprietor have a freedom—and assume a power—that is unthinkable under the watchful eye of a Murdoch or a Barclay brother (owners of the Telegraph ). They are likely to have a different kind of relationship with their staff and with their readers. The organization is bound to be less of a pyramid, pointing up to a usually elusive figure on high. It is likely to listen more closely to the reporter in the field than any voice from above.

Decision-making among peers can undoubtedly be messy and subject to group-think. The morning editorial conference—open to all—can be a fermentation vessel for ideas, and can also be a place of furious disagreement. There is no “line to take” on Europe, Putin, whom to support in a general election, Israel-Palestine, or Syria. The editorial staff, with the editor, have to decide for themselves.

The trust officially has no views. When I was editor of The Guardian , from 1995 to 2015, I sometimes turned to the chair of the trust for advice—being first to publish the Edward Snowden revelations in 2013 (rewarded with a Pulitzer Prize, shared with The Washington Post ) was certainly one such moment—but I felt free to ignore it without consequences.

There are, inevitably, occasional tensions between the trust—there to protect the “heretofore” of editorial independence—and the business-side executives (with their own management and oversight boards) who have to keep the paper afloat (the preferred internal term is “profit-seeking” rather than “nonprofit”). One wonder of the past two hundred years is how seldom those tensions have broken through.

James Murdoch famously concluded a lecture in 2009 with the ringing cry: “The only reliable, durable, and perpetual guarantor of independence is profit.” The more alert in the room asked themselves, “Independence from whom?” No amount of profit will buy you independence from Rupert Murdoch, if he happens to own you. Scott and his successors were free to think and report what they liked—even, sometimes, at a short-term cost to the business.

Somewhat to the alarm of his business managers, Scott became more radical in his politics from the mid-1880s onward. He vigorously supported Gladstone’s drive for Irish self-rule within the UK, and went on to oppose imperialism in Africa, to support the suffragists, and to help define the liberal politics that grew out of the decline of the Whigs. “Scott threw the whole weight of the paper on the side of Home Rule, that is to say, to the left,” wrote Dennis McKeown in a 1972 Ph.D. dissertation on him, “and this just as its readers were going over in droves to the right.” 2 Scott didn’t stop there, vociferously opposing the Boer War and publishing searing accounts from his correspondent Emily Hobhouse on the disgraceful conditions in the concentration camps the British had constructed in South Africa to hold Boer families who had been burned out of their farms.

Large sections of the public, in full patriotic fervor, loathed what they saw as the paper’s treachery. The Guardian ’s offices and Scott’s house were put under police protection. The paper lost a dangerous number of readers, leading David Ayerst to write in his “Guardian”: Biography of a Newspaper (1971), “What happened between the Diamond Jubilee in 1897 and the end of the Boer War in 1902 nearly killed the Guardian .”

There was a similarly virulent reaction in 1956, when Britain and France seized the Suez Canal. “An act of folly without justification in any terms but brief expediency,” rasped the editorials written by the newly installed Alastair Hetherington. “It pours petrol on a growing fire…. It is wrong on every count—moral, military, and political.” These were rousing phrases, but caused initial mass defections among readers, as the circulation manager reported to then chairman Laurence Scott. He told Hetherington not to let the figures influence his editorial judgment.

In both cases it proved good for business in the longer term for the paper to hold its editorial nerve. Readers can often have an acute instinct for when a newspaper is acting out of principle—a relevant lesson in the present age, when metrics can be designed to reward or prioritize content that is seen to please the audience (or, at the very least, not alienate it). Metrics might have demanded support for Britain’s actions in South Africa and Suez. Metrics would have been wrong.

The reluctance of the Scott Trust, not to mention the boards that oversee the paper on its behalf, to intervene in editorial issues can give the newsroom a rare shield of protection. When, in 2013, a number of parliamentarians tried to persuade the Guardian Media Group board and the Scott Trust to prevent me, as editor, from reporting on Snowden’s surveillance revelations, both bodies responded that they literally had no powers to intervene.

The cabinet secretary, Sir Jeremy Heywood, had done his best to persuade us that, about two weeks after the first story appeared, it was time to stop. Fearing that we would face an injunction, we transferred the top-secret leaked material to The New York Times , since there is greater protection against prior restraint in the US. I was then hauled in front of a House of Commons select committee—with two police officers, by then investigating me, waiting in the next room as I was asked by an MP , “Do you love your country?”

It was at moments such as this that trust ownership came into its own.

There have been both lean and comfortable times over the decades. The 1930s—battered by an economic depression—were precarious. The late 1850s had been as well, mainly due to the rising cost of paper and the rising cost of producing a newspaper by then selling for only a penny: the severe cutbacks in the editorial budget were remarked on by Friedrich Engels, who wrote to Karl Marx in April 1858, “The Guardian chaps have reduced all expenses, correspondents’ contributions etc. Their attempt to produce a first-class provincial paper has completely collapsed.”

By the end of World War I advertising revenues were healthy and profits were rising. In subsequent lean years The Guardian came to rely on cross-subsidies from the much more profitable Manchester Evening News , which raked in local advertising and had none of the national or international editorial costs of its sister paper.

In 1959 The Guardian dared to drop “Manchester” from its title in bold anticipation of being regarded as a truly national paper. There was a near-death crisis after it started printing in London in 1961 and moved its editorial headquarters there in 1964. By 1965 Laurence Scott believed The Guardian couldn’t survive: it was losing £900,000 a year (about $21 million in today’s money). He began covert negotiations to merge it with The Times , but the plan was scuppered when Hetherington heard about it. Editors of The Guardian did not inevitably have veto power, but, in C.P. Scott’s 1921 phrase, they marched “just an inch or two in advance” of the business manager.

Financial salvation eventually came in two forms. The first was the astute buildup of classified job advertising: by 1992 the paper had a commanding position in the UK market. (This went into reverse with the collapse of “small ads” in print and the rise of not only Craigslist but Big Tech, as a result of which The Guardian last made a profit in 2004.) The other was the purchase and development of Auto Trader , a magazine and subsequently a website for selling used cars. As the revenues from the Manchester Evening News also began to decline, The Guardian became more reliant on a subsidy from the profits of Auto Trader .

In 1993 the Scott Trust acquired the highly unprofitable Observer , the world’s oldest Sunday newspaper, in a bid to stave off competition from the burgeoning Independent and Independent on Sunday . The Guardian and The Observer now coexist, sharing a number of journalists and back-office facilities. By 2014 the trust was able to sell the flourishing Auto Trader and create an endowment of around $1.3 billion to help secure the future of The Guardian . In 2019–2020 The Guardian and The Observer (by now jointly accounted for) lost around $39 million—covered by a cautious drawdown from the endowment. The company recently announced a £16 million ($22 million) “cash outflow” for 2020–2021.

Twenty-five years into the digital whirlwind it is obvious that ruthless and indiscriminate cutting back on editorial costs combined with the merging of more and more titles into ever larger asset-stripping vehicles is seldom a recipe for editorial or commercial success. Any news business that does not place journalism at its heart cannot expect to flourish.

The Guardian has chosen to remain accessible by all while attracting both subscriptions and voluntary support. In 2017 the trust also announced the creation of theguardian.org, a US-based nonprofit with tax-exempt status to attract philanthropic giving in support of public interest journalism, including projects on climate change, guns, and health inequality. In 2012 it had come up with the idea of some form of membership to The Guardian , in the hope that readers would support “their” paper as a public good (“I pay so that everyone can read it”) rather than a private one (“I pay so that I can read it”). The company recently announced that readers contributed £69 million ($95.7 million) in subscriptions and donations in 2020–2021—a growth of 61 percent. The Australian edition, launched in 2013, is now profitable and, with reader donations, employs more than seventy journalists.

The paper was simultaneously investing heavily in investigative journalism. The Wikileaks releases about secret US Defense Department documents and diplomatic cables relating to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan caught international attention. The five-year investigation into phone-hacking at News Corps led to the closure of the News of the World , the jailing of its editor, and the subsequent government inquiry into press ethics. There followed influential series on corporate and individual tax avoidance, torture and rendition by Western intelligence agencies, modern slavery around the world, and toxic dumping by Western companies in African countries. A long investigation into undercover surveillance, involving police officers who formed relationships with activists, including members of environmental and black justice groups, sometimes even fathering children with them, has led to another public inquiry. The Snowden revelations again catapulted The Guardian to international notice in 2013.

That reporting—challenging, expensive, legally fraught, and unpredictable as it was—turned out to be a kind of business model, attracting readers who might think, “If that’s the kind of journalism you produce, I’ll support it.”

Of course, The Guardian will never be universally admired. Paul Dacre, the former editor of The Daily Mail , a large-circulation conservative tabloid, denounced in a 2007 lecture what he termed the “subsidariat”—he included The Times , the BBC , The Independent , and The Guardian —for being unable to connect with enough readers to be commercially viable in the way tabloids do. He found this both morally and editorially reprehensible. A self-appointed elite, he argued, was able “to impose minority values on the great majority.”

But the criticisms come as often from the left. Capitalism’s Conscience , a collection of essays published to coincide with The Guardian ’s bicentenary, contests the notion that—in the words of the book’s editor, Des Freedman of Goldsmiths College, University of London—“the Guardian has ever been a reliable ally for the left.” In his introductory essay, Freedman deplores the tendency (by Guardian staff, he says, as well as its chroniclers) to “fetishize” the actions of the founder, John Edward Taylor, as those of a brave truthteller:

It is an uncomfortable reality for the Guardian that the capital required for its start-up came largely from an industry whose own wealth was intimately bound up with the profits accrued from the slave trade, and the prospectus clearly illustrates that the title was designed to be the house organ of cotton interests.

Gary Younge, until recently a prominent columnist on the paper, writes in the collection that The Guardian can never live up to the left’s expectations:

The Guardian is perceived as a left-wing paper in relation to what else is on offer. People on the left, therefore, expect more from it—more from it than it has ever given and more than it probably would ever give. But because it’s the one place where people on the left feel that they may see themselves or their worldview, then it disappoints more keenly precisely because they expect more from it.

Very similar things were written about the paper in the 1820s.

The most recent disappointment for those on the left was the paper’s failure—as they saw it—to wholeheartedly embrace Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour Party. Younge writes:

The issue I raised internally, repeatedly, was not that we should support Corbyn—newspapers should not act as adjuncts to political parties—but that we should be more curious about what he represented and why. It wasn’t our job to predict the outcome but it was necessary to describe and interpret what we saw.

Capitalism’s Conscience does acknowledge remarkably positive and progressive aspects of The Guardian ’s more recent history, including in-depth coverage of the developing world, a better-than-some track record on diversity, a commitment to investigative reporting, and a balanced approach to Brexit. The Guardian ’s women’s page, started in 1957, became “an important site of consciousness raising for what was then unfolding in the UK to become the Women’s Liberation Movement,” according to an essay by Hannah Hamad. On the other hand, Mareile Pfannebecker and Jilly Boyce Kay criticize the paper’s “centrist feminism,” which is, they say, pitted against trans rights.

So the paper can disappoint the left and anger the right. To my understanding of its “heretofore,” some of the criticism stems from some confusion about its origins. The point of Taylor’s response to Peterloo was not that he should have backed all the demands of the Radicals. He simply believed no progress was possible without an agreed-upon version of the facts.

Maybe, after recent years of increasingly not knowing whom or what to believe, we can look back at that modest two-hundred-year-old aspiration with a degree of gratitude. No one now buys a newspaper to make long-term profits. Maybe the Taylor-Scott vision of news as public service could return to fashion.

May 27, 2021

Ending the Kennedy Romance

Russian Metamorphoses

A Snob’s Progress

Subscribe to our Newsletters

More by Alan Rusbridger

December 8, 2016 issue

Will the revelations lead not only to prosecution, but to effective prevention of attempts to avoid paying billions in taxes?

November 10, 2016 issue

A message pinged onto a reporter’s laptop: “Hello. This is John doe. Interested in data? I’m happy to share.”

October 27, 2016 issue

Alan Rusbridger is the Principal of Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford, and Chair of the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. For twenty years he was Editor in Chief of The Guardian . He sits on the Facebook Oversight Board. His most recent book is News and How to Use It . (May 2021)

The Manchester Guardian: A Century of History (London: Chatto and Windus, 1921). ↩

Michael Dennis McKeown, The Principles and Politics of “The Manchester Guardian” Under C.P. Scott to 1914 , Ph.D. dissertation, Case Western Reserve University, 1972. ↩

The Opening Editorial

November 7, 2013 issue

Short Review

July 14, 1977 issue

Short Reviews

October 12, 1978 issue

Mixed Feelings

April 3, 1975 issue

November 25, 1976 issue

New Editions

February 1, 1963 issue

December 17, 1981 issue

Art and Society Again

June 11, 1964 issue

Subscribe and save 50%!

Get immediate access to the current issue and over 25,000 articles from the archives, plus the NYR App.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Popular Topics

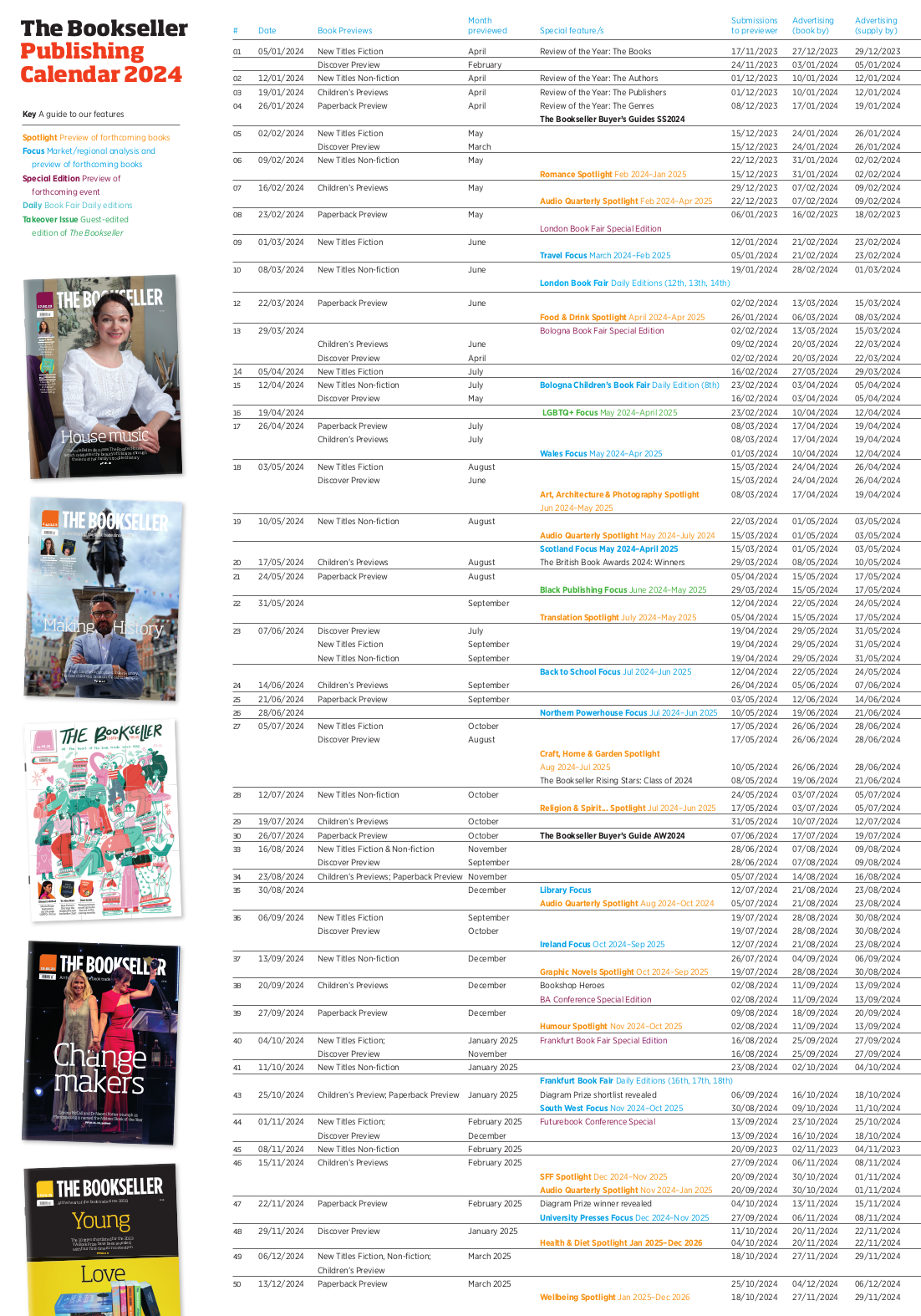

Publishing Calendar

Books from Czechia

Rizzoli International Publications acquires Chelsea Green Publishing

Shock delay to opening of Thalia's new flagship bookshop in Hamburg

Abigail Barclay promoted to managing director of Inspired Search

Bloomsbury joins Hachette UK Distribution after 25 years with MDL

Alice Slater, Megan Davis and Stig Abell up for debut award at CrimeFest

- Most Viewed

- Most Commented

Carrie Plitt moves to US, becoming Felicity Bryan Agency's 'woman on the ground in New York'

Bologna Children’s Book Fair 2025 to run just 18 days after London Book Fair

Bloomsbury bags global deal for Amber Hamilton's gothic YA début romantasy

Little Tiger roars for former Penguin editor Eric Huang's East Asian mythology-inspired series

A third of translators report losing work to generative AI systems, SoA survey reveals

Latest issue, 12th april 2024.

- Lead Story: Bologna Children’s Book Fair 2024

- Bookshop Spotlight: The Wivenhoe Bookshop

- Author Profiles: Kevin Barry and Katie Kirby

- New Titles Non-Fiction: July

- Category Spotlight: Discover (May)

Submit your titles for the upcoming Buyer's Guides

The deadline to submit titles for the autumn/winter Buyer's Guides is NEXT FRIDAY, 28th April. Submit your titles for inclusion now.

FIND OUT MORE

Subscribe Today

Advertisement

Supported by

Parenting in a Pandemic, and Other Tales of Woe

Gillian Linden’s slim debut novel, “Negative Space,” explores the being and nothingness of modern motherhood.

- Share full article

By Lynn Steger Strong

Lynn Steger Strong is the author of “ Flight ,” among other books.

NEGATIVE SPACE, by Gillian Linden

Reading Gillian Linden’s “Negative Space,” I kept thinking of the Lydia Davis story “Fear.” The story opens with a woman running out of her house, “face white and overcoat flapping wildly.” “Emergency, emergency,” the woman says. In the next sentence, Davis tells us that “nothing has really happened” to this woman, but still the community comes out to comfort her. “Fear,” like Linden’s novel, grapples with an amorphous sense of something coming, threatening; it situates the reader inside a world in which awful things exist but nothing, really, has happened yet. In the meantime, the world around both the woman in Davis’s story and the one in Linden’s novel mostly wants her to be quiet.

“Negative Space” has a straightforward enough shape: We are with our narrator, a wife and mother of two, over the course of a week. At the outset, her daughter has a gum infection. A not-quite emergency — a couple of her baby teeth will have to be extracted; all will almost certainly be fine. Our narrator goes on to work at the Manhattan private school where she teaches English part time. It’s almost June and she’s waiting to hear if she’ll have work in the next school year.

While searching for a class set of Shakespeare plays (Shakespeare can be taught only at the end of the year, because, in the eyes of the private school’s customer-parents, he is problematic, but also perhaps necessary), she sees the head of her department — the man who will decide whether to bring her back on staff — maybe “nuzzling,” maybe “nudging” a troubled student in what looks to the narrator like an overly intimate way.

Insofar as the book has an engine, this is it: Jane, the daughter, with her gum infection, is anxious about the tooth extraction; our narrator attempts to report her boss, to talk through what she saw with various friends and administrators, but it mostly comes to naught. There are faculty meetings, family dinners, a phone call with a friend and another later with our narrator’s mother. Nothing really happens, in other words, but then, as the title tells us, that nothing really is the book’s interest.

The prose throughout is lapidary, sharp. Linden is spare with the metaphors so that when they come, they stick and crystallize affectingly in your brain. “You could discover anything on the phone — reassuring news, more often troubling news,” she writes. “The phone was like the children’s toy baskets, in which I’d find the felt doll Lewis had lost, and also dried-up clementine peels, a toothbrush with darkened bristles, a watch face missing its strap.” She is quick to build a scene and exit it, elegantly depicting the almost constant yearning that lives inside a life that feels both vaguely like one you might like and also like a trap.

It’s the year after the first round of Covid vaccinations. Kids still wear masks in school. It’s unseasonably warm out, as it is almost always now unseasonably warm. Our narrator’s husband, who used to travel for work, has managed to be home over the past year-plus and still stay mostly absent. Negative space, in other words, lack and unknown threat, are everywhere.

Often, lately, I’ve been thinking about what books are supposed to do, what we want or need from them at this, but also any, moment. “Negative Space” beautifully executes a good amount of what feels imperative; acutely, assuredly, it mirrors a particular world back to us. That might sound easy, but it isn’t. Even more so because depicting absence, making it feel concrete and alive, often renders a book hollow and shapeless, and Linden’s has both shape and heft. What I yearned for was a moment, a shift or observation that reflected this experience back at me but also made me ask questions. Something that expanded, complicated or troubled what I thought this world was, or could be.

NEGATIVE SPACE | By Gillian Linden | Norton | 176 pp. | $26.99

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

What can fiction tell us about the apocalypse? The writer Ayana Mathis finds unexpected hope in novels of crisis by Ling Ma, Jenny Offill and Jesmyn Ward .

At 28, the poet Tayi Tibble has been hailed as the funny, fresh and immensely skilled voice of a generation in Māori writing .

Amid a surge in book bans, the most challenged books in the United States in 2023 continued to focus on the experiences of L.G.B.T.Q. people or explore themes of race.

Stephen King, who has dominated horror fiction for decades , published his first novel, “Carrie,” in 1974. Margaret Atwood explains the book’s enduring appeal .

Do you want to be a better reader? Here’s some helpful advice to show you how to get the most out of your literary endeavor .

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Why Patricia Highsmith's most famous creature, Tom Ripley, continues to fascinate

Carole V. Bell

Andrew Scott plays Tom Ripley in the new Netflix series, Ripley , drawn from Patricia Highsmith's novel. Lorenzo Sisti/Netflix © 2021 hide caption

Andrew Scott plays Tom Ripley in the new Netflix series, Ripley , drawn from Patricia Highsmith's novel.

For a total psychopath, Tom Ripley is remarkably popular. As we near the 25th anniversary of the acclaimed Oscar-nominated big screen adaptation of Patricia Highsmith's most infamous creation, The Talented Mr. Ripley, Netflix has released a striking new reimagining, simply titled Ripley. Sinister and visually stunning, the series reminds us why the book continues to influence popular culture.

Through seven decades, Highsmith's novel, The Talented Mr. Ripley has grown in allure as a masterwork of American noir, boosted by – but distinct from – its adaptations. The core story is always the same: A wealthy man enlists fraudster Tom Ripley, his son's distant acquaintance, to travel to Italy and woo his errant, playboy son back to the fold; but rather than returning Dickie to his family, an envious Tom disposes of him and assumes his identity. Other murders follow to cover the first.

This bloody-minded serial killer fantasist and antisocial social climber would become Patricia Highsmith's best known and best loved creation. She published five Ripley novels in all from 1955 to 1991, the last a few years before her death. Since his debut, her all-American psychopath has inspired six screen adaptations, a play by Phyllis Nagy, and a musical staging. That legacy is a testament to Ripley's complicated appeal – amoral, unassuming and audacious — and Highsmith's scalpel-sharp writing. There's something irresistible about an unapologetic grifter, who seizes the chance at a better life by stealing someone else's. The text is rich enough to handle wildly different interpretations that feel true to the original and brilliant in their own right.

A window into Ripley's roots

In the first Ripley novel, one childhood scene is especially vivid. When he was 12, and his parents long dead, Tom's reluctant guardian Aunt Dottie made him get out of her car and run an errand on foot while stuck in traffic. When the cars started moving again, Tom was forced into "running between huge, inching cars, always about to touch the door of Aunt Dottie's car and never being quite able to..." Instead of waiting, his aunt "had kept inching along as fast as she could go..." Worse, she taunted him, "yelling, 'Come on, come on, slowpoke!' out the window." The memory ends with Tom in teary frustration and his aunt hurling a slur at him: "Sissy! He's a sissy from the ground up. Just like his father!"

Untangling the contradictions of crime novelist Patricia Highsmith

This story bubbles up into the memory of the adult con man Tom Ripley while he's lying on a ship deck chair on the way to Europe. Buoyed in body and spirit by the luxury and abundance of his surroundings, Tom starts to plot a brighter future for himself. But he keeps returning to past indignities, and that cruel vignette stands out. Looking back from his comfortable perch, Ripley thinks, "It was a wonder he had emerged from such treatment as well as he had." This isn't justification, just a part of Ripley's essence – Ripley as a vulnerable boy rather than cipher or leech or thief, a man whose emotional and physical deprivations curdle into resentment and violence.

Andrew Scott as Tom Ripley in the Netflix series Ripley. Philippe Antonello/Netflix © 2023 hide caption

That window into Ripley's roots is one reason I loved re-reading the novel in the lead up to a new adaptation. Highsmith illuminates the inner life of what she recognized as her "psychopath hero" with identification rather than judgment (Highsmith was openly enamored of her creation). That intense interiority is one reason Highsmith is often credited with helping reinvent and popularize the psychological thriller, a genre with roots in the 19th century, and why her influence persists despite a deservedly controversial reputation . Her debut novel became Hitchcock's Strangers on a Train (1951) less than a year after publication, and her 1957 novel Deep Water appears on The Atlantic's list of 100 Great American novels.

With Ripley, the narration lives outside of Tom but close enough for dissection. We learn that he's a loner but not completely, that he gets antsy around people, only able to sustain a performance of normalcy for so long. He's caught between a need for independence born of his smothering yet loveless upbringing and an aching desire for other people's good regard.

In proximity to beauty and privilege but not of it, Tom's neediness escalates. He's ruthless and amoral, but human and self-conscious. He sobs! And he yearns.. Scene by masterful scene, sentence by sentence, with each disturbing thought and memory, Highsmith reveals how Ripley's psyche veers out of bounds, a slow drip punctuated by shocking jumps. When Dickie and Tom give a taxi home to a local girl they bump into, and she thanks them, calling them the nicest Americans she's ever met, Tom remarks to Dickie, "You know what most crummy Americans would do in a case like that—rape her." It's a sharp kick in the midst of banality.

Don't call him a sociopath: Here's how Andrew Scott humanizes 'Ripley'

Worse, when real violent thoughts finally result in action, Tom revels like a pig in mud in his stolen persona. Feeling "blameless and free," he likens his confidence in Dickie's shoes to how "a fine actor probably feels when he plays an important role on a stage with the conviction that the role he is playing could not be played better by anyone else." The great beauty of Highsmith's novel lies in moments like this, illuminating the dark recesses of a psyche spinning out of control.

A story ripe for retelling

A portrait this faceted begs for retelling and reinvention — it's a dream role for an actor — but the text also defies total capture. Highsmith could make a two-act play out of the domestic symbolism and social psychological dynamics of Dickie purchasing a refrigerator.

The beauty of the 1999 movie and 2024 series interpretations of Ripley, despite this high bar, is that they're fully formed artworks of their own.

Gwyneth Paltrow and Jude Law in the film The Talented Mr. Ripley. Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo hide caption

Netflix's series has both the text and the sublimely entertaining 1999 movie with its constellation of Hollywood stars to live up to. Matt Damon and Jude Law were at the height of their powers as Tom Ripley and Dickie Greenleaf (Law earned a best supporting actor Oscar nomination), and Gwyneth Paltrow was incandescent and multidimensional as Dickie's girlfriend Marge. They're memorably supported by Cate Blanchette and Philip Seymour Hoffman as trust fund-babies abroad. Their production is gorgeously shot in the sun-drenched Amalfi coast and the Oscar nominated soundtrack beautifully amplifies the emotion and story. In Anthony Minghella's screenplay, when the nastiness and violence emerge from Dickie as well as Tom it's an arresting aberration against this deliberately effervescent, candy-colored backdrop.

The appeal of Minghella's acclaimed and popular film has more than endured, but it's not the only classic iteration of Ripley's debut. The first significant big screen rendering was the 1960 French thriller Purple Noon, starring Alain Delon as a Ripley with beauty that rivals Dickie's. There are three less celebrated adaptations of other Ripley novels. 2023's Saltburn wasn't a Ripley reimagining but its story of upper class ruin at the hands of an interloper seem to spring from a similar well. Plus, the film's most audacious interlude reads as an homage to Jude Law and Matt Damon's homoerotic bathtub scene, and the movie and discourse around added new heat to the Highsmith mystique.

Anthony Minghella, far left, director of the film "The Talented Mr. Ripley," poses with cast members, from left, Matt Damon, Jude Law, Gwyneth Paltrow, Cate Blanchett and Philip Seymour Hoffman at the premiere of the film on Dec. 12, 1999, in the Westwood section of Los Angeles. Chris Pizzello/AP hide caption

Anthony Minghella, far left, director of the film "The Talented Mr. Ripley," poses with cast members, from left, Matt Damon, Jude Law, Gwyneth Paltrow, Cate Blanchett and Philip Seymour Hoffman at the premiere of the film on Dec. 12, 1999, in the Westwood section of Los Angeles.

Despite all that history, the pedigreed new Netflix production successfully forges its own haunting vision of Ripley. Written and directed by Steve Zaillian (screenwriter of Schindler's List and The Irishman ), Ripley (mostly) benefits from having more space to breathe than the film – and from Andrew Scott's unflinching performance.

Netflix's stylish 'Ripley' stretches the grift — and the tension — to the max

Leaving the Hot Priest of Fleabag fame behind, Scott gives a harder, colder interpretation of the title role. Though significantly older than Highsmith's 25-year-old antihero, the 47-year-old BAFTA winner Scott ( All of Us Strangers , Sherlock ) fully embodies the brooding and seething Ripley. Rather than charming and boyish, Netflix's Tom Ripley is visibly creased and battered. Instead of Highsmith's peevish 25-year-old, who notices with pleasure and opportunism physical resemblances with his privileged friend, Ripley and Dickie's relationship is more clearly grifter and target. Ripley director Zaillan also advances the timeline to 1961, plunging Ripley into a more modern and edgy world.

Scott is well supported by Johnny Flynn ( Emma ) as a feckless Dickie, and Dakota Fanning, who delivers a mannered and pricklier Marge, the role that Gwyneth Paltrow made famous. If there's one flaw, it's that Ripley masters the style and techniques of Hitchcockian noir, without its momentum. This series' slow deliberate pace and eerie quiet can sometimes feel like a slog.

Pop Culture Happy Hour

'ripley' returns in black and white — and is so much better for it.

Still, Ripley 's performances and striking style elevate the series. Rendered in stark Black and white tones, each shot is as visually arresting as the best still photo. Anthropological and artistic, it's the opposite of Anthony Minghella's bright Italian playground presided over by Jude Law as a golden god. This approach transforms even the most ordinary scene —a cat on a bench in a Roman rooming house — into a foreboding tableau. The noirish visuals are the perfect look for this seedier and more cerebral thriller. So too are the peeling paint, decaying edifices, and too many steps on which the camera lingers. All together, the aesthetic looks like something out of an avant-garde European movie like Jean Cocteau 's La Belle et La Bête or a painting by Caravaggio. The series significantly expands on what Highsmith wrote about Tom's relationship with high art, spinning the idea that he had "discovered an interest in paintings'' from emulating Dickie into an obsessive identification with a 17th-century Italian painter known for his bloody and brutal canvases, interplay of shadow and light, and for murder. It's an ingenious representation of Tom's descent on screen.

With these inspired creative choices, the Anthony Minghella film and the Netflix series stand on their own. But if you have the inclination, the two major screen productions and the novel form a phenomenal triple bill.

A slow runner and fast reader, Carole V. Bell is a cultural critic and communication scholar focusing on media, politics and identity. You can find her on Twitter @BellCV .

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Civil War review – Alex Garland’s delirious dive into divided US society

Fratricidal warfare has exploded in North America, and war photographers including Lee (Kirsten Dunst) are eager to capture the money shot in this violent action thriller

W riter-director Alex Garland stages a spectacular if evasively apolitical “civil war” in this futurist-dystopian action thriller, involving hundreds of extras lying on the road next to upturned blackened cars with CGI-mutilated buildings in the smoky distance. The film’s fence-sitting reluctance to name any of the issues that might actually result in a civil war arguably means that the film can be enjoyed by the widest possible audience base. But the whole thing does finally snap into shape for a Call of Duty melee in the heart of American democracy, an ugly denouement possibly riffing on the January 6 Capitol attack, in which something seems to be clearly at stake and which (belatedly) gives us a glimpse of believable horror and delirium.

The scene is an America whose evident but unspecified divisions have exploded into open fratricidal warfare. The states of Texas and California are now ruled by the rebellious secessionists, the Western Forces, or WF, making massive advances on Washington DC, a situation about which the president ( Nick Offerman ) is in denial, making delusional TV addresses about how well he’s doing.

A group of photojournalists now plans to make the terrifyingly dangerous journey in a press SUV behind WF lines, possibly hoping to tag along with their advance on the capital, each secretly dreaming of the ultimate money shot: the capture or execution of the commander-in-chief. Veteran war photographer Lee is played by Kirsten Dunst with a permanently sorrowful and disapproving schoolteacherly expression of dismay; her buddy is Reuters reporter Joel (Wagner Moura) who is a warfare-adrenaline junkie, euphoric after each scary shoot up. (“Holy fuckin’ shit! What a fuckin’ rush!”) Ageing veteran Sammy (Stephen McKinley Henderson) is a New York Times reporter, the voice of wisdom. Just-out-of-college newbie Jessie, played by Cailee Spaeny, cheekily sweet-talks Joel into letting her ride along in their grownups’ car and almost overnight turns from a callow student into a cool wiseacre. They have conversations, in the time honoured manner of fictional war journalists, about subjects like whether journalism makes a difference and what they would be prepared to photograph – but weirdly don’t talk about what has caused this civil war.

It is clearly a reasonably diverse group, although it is this very diversity that gives us an easier task of guessing which of them is going to make a self-sacrificial gesture of courage to save the others. For their journey, Garland gives them freaky and surreal episodes and encounters, underscored by interesting and emphatic musical choices that mimic their dissociative trauma, although sometimes these episodes will be suddenly curtailed. At one stage they’re pinned down by a sniper in an abandoned outdoor play area with Christmas music bizarrely playing … the next thing we know they’re safely back in the car. How? It’s a strange, violent dream of disorder, drained of ideological meaning.

after newsletter promotion

- Peter Bradshaw's film of the week

- Alex Garland

- Kirsten Dunst

- Science fiction and fantasy films

- Action and adventure films

Most viewed

IMAGES

COMMENTS

The best recent science fiction, fantasy and horror - reviews roundup ... About 42,266 results for Books + Reviews. ... direct from the Guardian every morning

Discover the latest books news, reviews and analysis from the Guardian, the world's leading liberal voice on literature and culture.

Kennedy 35 by Charles Cumming (HarperCollins, £18.99) The third book in Cumming's excellent Box 88 series is a time slip between the present and 1995, when protagonist Lachlan Kite, who was ...

Guardian review. 20 September 2021. Trump may be gone, but Covid has not seen off populism ... From 9/11 to the storming of the Capitol, a new book by Biden biographer Evan Osnos covers a ...

Rachel Roddy on the best food books of the year, from stories of growing up in a Chinese takeaway to pressure cooker recipes and a guide to snacking. To browse all of the Guardian's best books ...

The best fiction of 2023. The book I've recommended most this year - and had the most enthusiastic feedback about, a whopping 656 pages later - is without doubt Paul Murray's Booker-shortlisted tragicomedy, The Bee Sting (Hamish Hamilton). This story of an Irish family's tribulations told from four points of view combines freewheeling ...

The best recent science fiction, fantasy and horror - reviews roundup. 12 Apr 2024. Audiobook of the week. Tremor by Teju Cole audiobook review - colonialism's long shadow. 12 Apr 2024 ...

When on the morning of 12 August 2022, in Chautauqua in upstate New York, on stage to talk about (of all things) the importance of keeping writers safe from harm, he saw a figure in black rushing ...

Best fiction of 2022. Some of the year's biggest books were the most divisive. In her follow-up to A Little Life, To Paradise (Picador), Hanya Yanagihara split the critics with an epic if inconclusive saga of privilege and suffering in three alternative Americas: a genderqueered late 19th century, the Aids-blasted 1980s, and a totalitarian ...

For the 10th year running, here's the Observer New Review's annual pick of debut novels we reckon you won't want to miss.No one could accuse us of failing to read the runes last time out, when our selection included Bonnie Garmus's gazillion-selling Lessons in Chemistry, Louise Kennedy's Trespasses - the title most frequently cited as the best book of 2022, according to industry ...

The village life of a 10-year-old girl is disrupted by a newcomer in a tale of youthful mystery and shifting emotions For the past 20 years, Suzannah Dunn has been known for historical novels ...

Kathryn Hughes picks titles about Andy Warhol, Artemisia Gentileschi and Lucian Freud, plus a clear-eyed view of London's changing landscape. Read the whole list: Best art books of 2020. Food. Mouthwatering pastries, simple one‑tin bakes, a new Ottolenghi and a rapturous account by Nigella ….

The Actual Star by Monica Byrne (Voyager, £20) In her second novel, Byrne braids together three storylines, each set a thousand years apart. The final days of 1012 are depicted through the experiences of three royal siblings in the early post-classical Mayan era; in December 2012, Leah, a 19-year-old mixed race American, makes the journey of a lifetime to Belize; and in 3012, as the last of ...

The best recent crime and thrillers - review roundup. The titular dwelling in Melissa Ginsburg's second novel, The House Uptown (Faber, £12.99), is the New Orleans home of boho artist Lane. Her slow drift into dementia on skeins of marijuana smoke is interrupted by the arrival of her granddaughter Ava, whose mother, Lane's daughter ...

The best recent science fiction, fantasy and horror - reviews roundup Latin American authors on rise in International Booker prize lists Marian Keyes: 'Books have one shot to impress me and if you miss, you miss'

Titan Books, £8.99, pp304. Maple Street is a picture-perfect, crescent-shaped block bordering a park on Long Island, New York. Its inhabitants are the sort of people who "dressed for work in business casual", who channel everything into their kids, who are "obsessed with college. Harvard in particular". Newcomers the Wildes are different.

April 16, 2024, 5:00 a.m. ET. CROOKED SEEDS, by Karen Jennings. When Nelson Mandela was released from Victor Verster Prison in 1990, after 27 years of incarceration, there was hope in the air. He ...

Here are the Books We Love: 380+ great 2023 reads recommended by NPR. November 20, 2023 • Books We Love returns with 380+ new titles handpicked by NPR staff and trusted critics. Find 11 years of ...

Far-right Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene's (R-Ga.) new book "duly reads like an audition for the No 2 slot on the 2024 Republican presidential ticket," according to a scathing review published by Britain's Guardian newspaper. "Venom, score-settling, fiction, self-absolution, self-aggrandizement. Greene's book, 'MTG,' has it all ...

April 2, 2024 • Eric Rickstad's novel is full of sadness and rage; it forces readers to look at one of the ugliest parts of U.S. culture, a too-common occurrence that is extremely rare in other ...

Two Centuries of 'The Guardian'. Alan Rusbridger. There have been both lean and comfortable times over the decades, but the paper has held its editorial nerve. May 27, 2021 issue. Katy Stoddard. Alan Rusbridger, then editor of The Guardian, addressing the newsroom after the paper won the Pulitzer Prize for its reporting on the documents ...

J. Alfred Prufrock measured his life out in coffee spoons.Caleb Carr has done so in cats. Carr is best known for his 1994 best-selling novel "The Alienist," about the search for a serial ...

Last modified on Tue 9 Apr 2024 11.37 EDT. Staff at technology company Meta discussed buying publishing house Simon & Schuster last year in order to procure books to train the company's ...

avg rating 4.03 — 7,858 ratings — published 2014. Want to Read. Rate this book. 1 of 5 stars 2 of 5 stars 3 of 5 stars 4 of 5 stars 5 of 5 stars. Books shelved as guardian-book-reviews: What Time is Love? by Holly Williams, The Wordhord: Daily Life in Old English by Hana Videen, Misfits: A Personal...

The Guardian Review section, home of its books coverage, has closed a year after a shake-up of the Saturday edition was announced. ao link Subscribe from less than £3.50 a week

The Guardian obtained a copy. The book appears with the Ukraine war grinding into its third year but with $60bn of new US military aid to Kyiv blocked by far-right Republicans in the US House, ...

In the meantime, the world around both the woman in Davis's story and the one in Linden's novel mostly wants her to be quiet. "Negative Space" has a straightforward enough shape: We are ...

Challengers review - Zendaya aces uproariously sexy tennis-set love triangle. Luca Guadagnino's terrifically absorbing screwball dramedy features a devastatingly cool leading lady, Josh O ...

Andrew Scott plays Tom Ripley n the new Netflix series. For a total psychopath, Tom Ripley is remarkably popular. As we near the 25th anniversary of the acclaimed Oscar-nominated big screen ...

Fratricidal warfare has exploded in North America, and war photographers including Lee (Kirsten Dunst) are eager to capture the money shot in this delirious action thriller