Covering a story? Visit our page for journalists or call (773) 702-8360.

UChicago Class Visits

Top stories.

- Ecologist tracks how insects can devastate forests—and how to stop them

- Author and ‘Odyssey’ translator Daniel Mendelsohn to deliver Berlin Family Lectures beginning April 23

National study finds in-school, high-dosage tutoring can reverse pandemic-era learning loss

Are children’s books becoming more diverse new research reveals persistent bias, using ai tools, researchers find that ‘mainstream’ books still lack non-white, non-male characters.

For much of American history, the books that children read have largely centered on white, male characters—but is that starting to change? Not very much, and not very quickly, suggests new research from the University of Chicago.

In a new working paper, Asst. Prof. Anjali Adukia of the Harris School of Public Policy found that over the past 100 years, characters in children’s books—as measured by images and text—are largely white and male. This white/male dominance is even true of books published in recent decades, which have seen heightened awareness about race and gender issues.

In fact, Adukia and her co-authors— Emileigh Harrison , Teodora Szasz and Hakizumwami Birali Runesha of the University of Chicago, and Alex Eble of Teachers College, Columbia University—found that mainstream children’s books have grown less representative in terms of skin color of characters pictured over the last two decades. Surprisingly, children themselves are underrepresented in children’s books as well.

“These findings have important implications for educators and publishers, and others concerned about the influence of books on childhood development,” said Adukia, whose research focuses on educational inequalities. “Research has demonstrated that the way that people are represented within books can contribute to children’s understanding about what roles they and others can or cannot inhabit.”

So how do children’s books stack up in terms of issues pertaining to race and gender?

To answer this question, the authors developed new artificial intelligence tools to analyze images in books, building on advances in the field of computer vision. They trained AI models to detect faces, classify skin color, and predict the race, gender and age of the faces. The effort analyzed 1,133 children’s books totaling more than 160,000 pages that were likely to appear in homes, classrooms and school libraries over the last century.

The works were categorized as either: “mainstream books,” those selected without explicit intention to highlight an identity group; and “diversity books,” which did explicitly highlight an identity group. They found that children were twice as likely to check out mainstream books from a major public library system relative to other books, suggesting greater exposure to the messages in these books.

“We find that mainstream books, which children are more likely to encounter, are more likely to depict characters with lighter skin than ‘diversity books,’ which are specifically selected to highlight people of color or females,” Adukia said. “Perhaps most surprising was that children are portrayed with lighter skin than adults in each collection, which has concerning implications for how perceptions related to youth and innocence may be shaped.”

In short, mainstream children’s books have gotten whiter in recent years. The authors’ analysis of images revealed the following about race in children’s books:

- Books in the mainstream collection are more likely to depict lighter-skinned characters than those in the diversity collection, perhaps speaking to the assumptions of book publishers about the assumed preferences of the median reader.

- Also, while female characters have always appeared in pictures over time (still less than 50% on average, but closer to 50% than in text), they are predominantly white.

- Particularly surprising is that despite no systematic differences in skin tones across ages in society, children are more likely than adults to be shown with lighter skin, regardless of collection.

The authors also compared the incidence of female appearances in images to female mentions in text to find that:

- Female characters are more consistently visualized (seen) in images than spoken about (heard) in the text, except in the collection of books specifically selected to highlight women and girls. This suggests that many books symbolically include female characters in pictures without substantive inclusion in the actual story.

- This underrepresentation holds regardless of the measure used: predicted gender of the pictured character, pronoun counts, specific gendered words, famous figure gender, and character first names.

Males, especially white males, are persistently more likely to be represented by every measure, with little change over time despite substantial changes in female societal participation.

Even though these books are targeted to children, adults are depicted more often than children in both images and text.

“The process of education itself—and its associated books and curricular materials—necessarily, and by design, transmits not only the values of society, but also whose space it is. The inclusion and exclusion of different identities send messages which can contribute to how children view their own potential and the potential of others which can then, in turn, shape subconscious defaults,” Adukia said. “Understanding what identities are being presented to children through their everyday books is a needed step in order to be able to make informed decisions about what content to include in curricula and to help mitigate the structural inequality that pervades society and our daily lives.“

The authors anticipate that their innovative application of AI will lead to further development of tools that can measure how people are represented in books and other media, and thereby help determine what content depicts characters in their full humanity. In addition, their methodology offers the promise of further inquiry into other forms of text and visual media, including literature and nonfiction, journalism, websites, art, photography, television, videos, movies and many others.

—Versions of this story were previously published by the Becker Friedman Institute and the Harris School of Public Policy .

Get more with UChicago News delivered to your inbox.

Recommended stories

How gender bias impacts college career guidance—and dissuades women…

UChicago students team up with pro athletes to fight inequality

Related Topics

Latest news, big brains podcast: what dogs are teaching us about aging.

Department of Race, Diaspora, and Indigeneity

Course on Afrofuturism brings together UChicago students and community members

Eclipse 2024

What eclipses have meant to people across the ages

Dark matter

First results from BREAD experiment demonstrate a new approach to searching for dark matter

Where do breakthrough discoveries and ideas come from?

Explore The Day Tomorrow Began

Study finds increase in suicides among Black and Latino Chicagoans

Education Lab

Around UChicago

It’s in our core

New initiative highlights UChicago’s unique undergraduate experience

Alumni Awards

Two Nobel laureates among recipients of UChicago’s 2024 Alumni Awards

Faculty Awards

Profs. John MacAloon and Martha Nussbaum to receive 2024 Norman Maclean Faculty…

Sloan Research Fellowships

Five UChicago scholars awarded prestigious Sloan Fellowships in 2024

Convocation

Prof. John List named speaker for UChicago’s 2024 Convocation ceremony

The College

Anna Chlumsky, AB’02, named UChicago’s 2024 Class Day speaker

UChicago Medicine

“I saw an opportunity to leverage the intellectual firepower of a world-class university for advancing cancer research and care.”

Announcement

Ethan Bueno de Mesquita appointed dean of the Harris School of Public Policy

December 1, 2023

Are Children’s Books Improving Representation?

Racial and gender disparities persist in award-winning kids’ literature despite recent gains in representation

By Jesse Greenspan

monkeybusinessimages/Getty Images

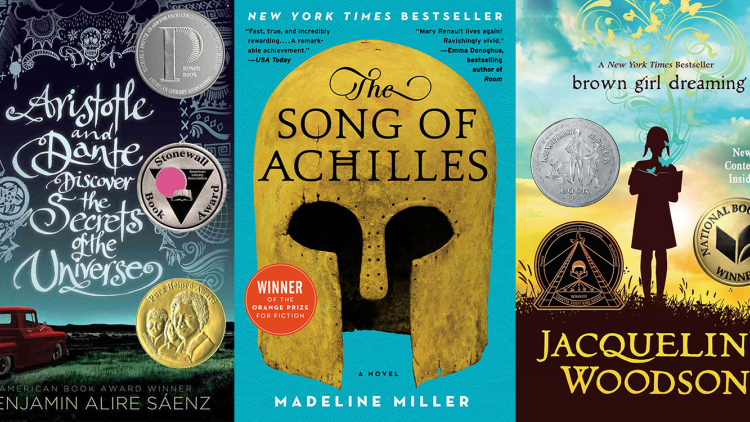

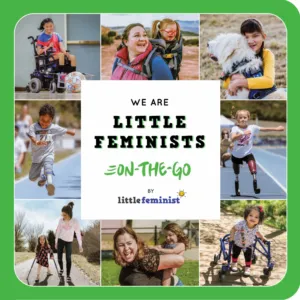

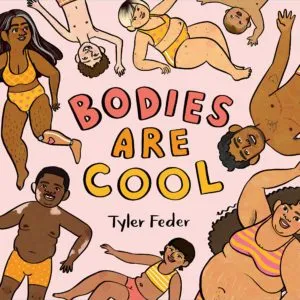

Children's literature has become far more diverse in the past decade, helping more kids than ever to see themselves in their favorite books. Of the thousands of kids' and teens' books reviewed in a 2022 analysis , about 45 percent had a nonwhite author, illustrator or compiler, up from 8 percent in 2014. “There are just so many more choices of books [reflecting] the multifaceted complexity of individual lives,” says Tessa Michaelson Schmidt, director of the Cooperative Children's Book Center at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

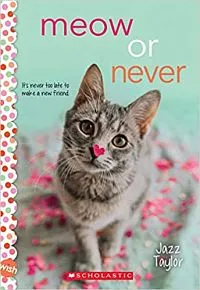

But white males remain overrepresented in the most influential children's stories, the authors of a recent study concluded. The research, published in the Quarterly Journal of Economics , examined the winners and honorees of the Newbery and Caldecott medals—widely considered the most prestigious prizes in kids' literature—and the recipients of 17 awards for diversity. University of Chicago social scientist Anjali Adukia and her colleagues scanned 1,130 of these award-winning books, covering more than 162,000 pages, and used an artificial-intelligence program trained to detect faces and determine the age, race and gender of each pictured character.

Machine learning let the researchers pick up on details they may have missed if they had combed through the books by hand. For example, on average, youngsters were depicted with lighter skin than adults of the same race. And female characters appeared more often in images than in text, which “suggests more symbolic inclusion ... rather than substantive inclusion,” according to the study's authors. They also found that the vast majority of famous people mentioned in Newbery- and Caldecott-winning books are white.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The results come amid a nationwide cultural clash, with diversity campaigns running alongside attempts to ban books that address aspects of race and sexual identity. But kids crave exposure to stories about people like them, which build up their feelings of self-worth and help them maintain an interest in reading, says Caroline Tung Richmond, an author of young adult fiction and executive director of the nonprofit organization We Need Diverse Books. At the same time, she says, young people benefit from stories that allow them “to see into a different culture or identity and build empathy.”

.jpg?w=900)

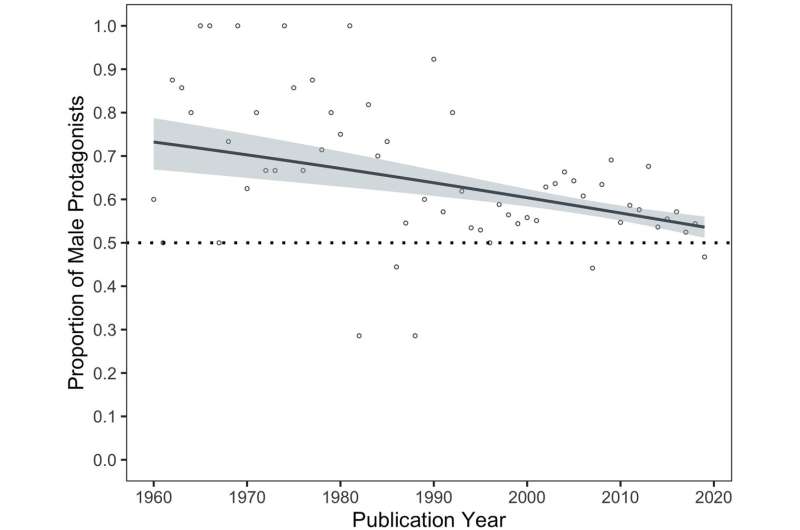

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Source: “What We Teach about Race and Gender: Representation in Images and Text of Chilren’s Books,” by Anjali Adukia et al., in Quarterly Journal of Economics , Vol. 138; 2023 ( data )

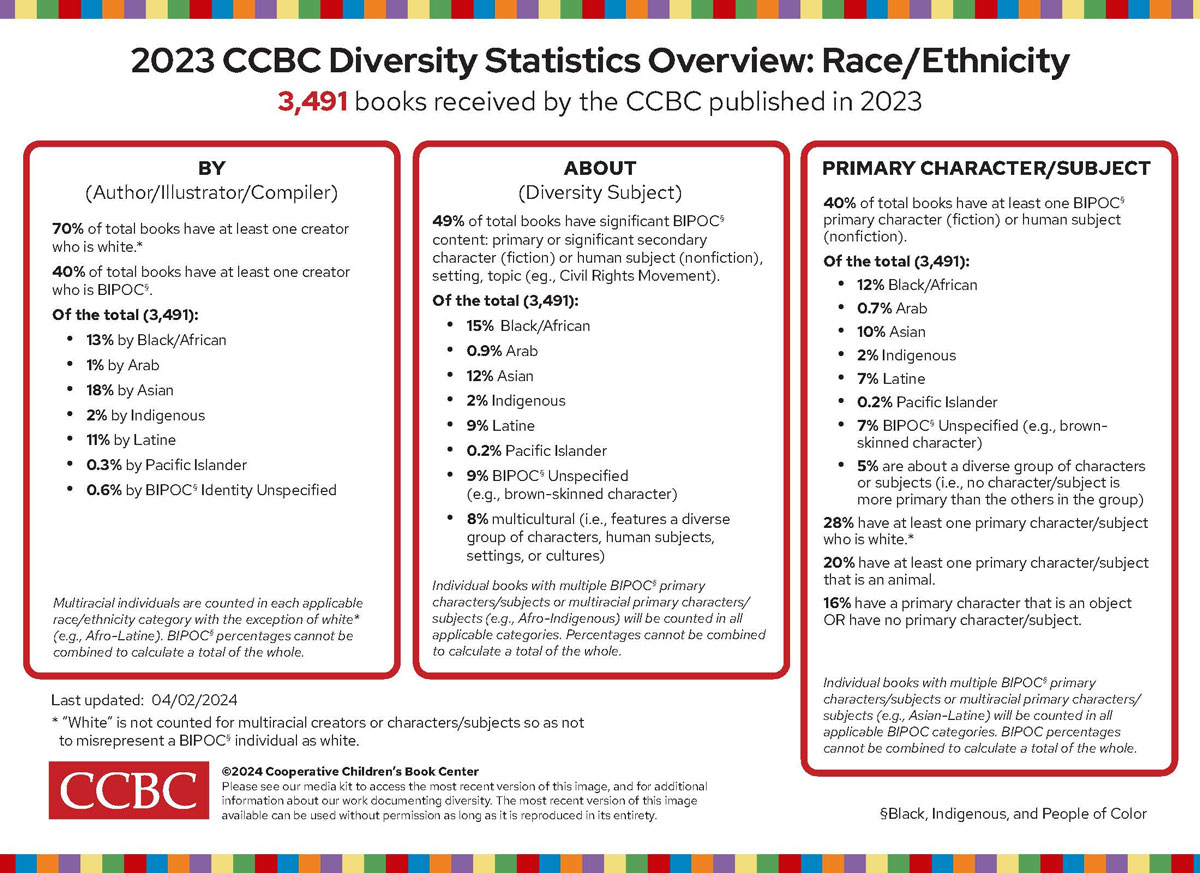

CCBC Diversity Statistics

The CCBC has been documenting books for children and teens it receives annually by and about Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) since 1994. Before that, between 1985 and 1993, we documented books by and about Black people only.

Beginning in 2018, we began to document the content of every new book we receive. Also in 2018, we began to document additional aspects of identity in our analysis, including disability, LGBTQ+, and religion.

Our annual data on Books by and about Black, Indigenous and People of Color (links below), which we’ve been compiling since 1985, and our Diversity Statistics Media Kit , are the most readily accessible and accurate summaries of the CCBC’s Diversity Statistics.

The CCBC Diversity Statistics FAQs provide essential context for understanding and interpreting this data.

Books by and about Black, Indigenous and People of Color

- All Years (1985-Present)

- 2018 – Present (All publishers and U.S.-only publishers)

- 2002-2017 (All publishers and U.S-only publishers)

- Diversity Statistics FAQs More

- Diversity Resources More

- On Books and Publishing More

White Characters Still Dominate Kids’ Books and School Texts, Report Finds

- Share article

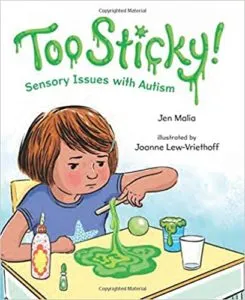

Educational materials don’t reflect the diversity of the nation’s schoolchildren, a new report finds—and many works that do feature characters of color reinforce stereotypes.

The research review , published by New America, a left-of-center think tank, analyzed more than 160 studies and published works on representation in children’s books, textbooks, and other media dating from the mid-20th century through the present. The report draws on quantitative and qualitative studies, dissertations, institutional reports, and books.

“Over time, what the research shows is that we’ve made progress as far as having more gender-balanced representation, though ... that gender representation tends to be from a binary perspective,” said Amanda LaTasha Armstrong, a research fellow in New America’s Education Policy Program, and the author of the report. “We’re also having more representation from communities of different racial and ethnic groups, but there’s still a very clear disparity.”

This review comes at a time when there’s increased national attention on what children are reading in school. Over the last year and a half, conversations about race and gender in assigned readings, library books, and textbooks have loomed large in classrooms and school board meetings across the country.

After the murder of George Floyd in May 2020, the ensuing protests for racial justice prompted some teachers and school systems to rethink the make-up of their classroom libraries and syllabi , including by adding more books by and about Black Americans and people of color. Other schools had already taken on this work of diversifying reading lists in years past.

But in recent months, parents and school board members in some communities have mobilized in attempts to ban books that address race and gender , claiming that these books are divisive or sexually explicit. Titles such as The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison, The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas, and Fun Home by Alison Bechdel have all faced recent challenges.

A slew of state laws restricting how teachers can discuss racism and sexism in the classroom have also affected schoolbooks. In Tennessee, for instance, the legislature passed a law that prohibits teachers from saying that any individual is inherently racist due to their race, or that individuals are responsible for actions taken by members of their race in the past. In one district there, parents challenged an autobiography of Ruby Bridges on the grounds that it violated the state’s law by teaching that “ white people are bad ” and “America is unjust.”

But Armstrong said that featuring books that represent a diversity of experiences and backgrounds is about supporting students, and that it’s crucial for creating strong learning environments. The report notes research that has shown that books and stories that represent students’ identities and experiences can foster student engagement in their own learning .

“It’s really about having a fair representation, or authentic representation, of American society, American people,” she said.

White, male characters still dominate children’s media

Over the past decades, children’s media has changed, Armstrong said: More races and ethnicities are represented in children’s books now, and male/female gender representation has moved closer to equal.

Even so, the review found that white characters still dominate children’s media. This holds true within picture books and children’s literature, but also within many school textbooks. Characters of color are underrepresented compared to the demographics of U.S. youth (a little more than half of all schoolchildren in the country are children of color).

Female characters are also underrepresented, though there has been an uptick over time. Still, girls of color may be left out: One cited 2020 study of books that won the Newbery Medal, an award for children’s literature, found that only 20 percent of Black characters and 25 percent of Asian American characters were female.

There is less research on transgender representation in books, though the report cites one study on books with LGBTQ themes that found 14 percent of primary characters and 21 percent of secondary characters were transgender.

It’s hard to know how these disparities translate to U.S. classrooms—are the racial and gender breakdowns in children’s media as a whole reflected in curricula and classroom libraries?

A separate study suggests that classroom libraries, at least, have become more diverse over the past year.

A forthcoming paper in Management Science from researchers at Carnegie Mellon University looked at requests for classroom books on the crowdfunding site DonorsChoose.org in the immediate aftermath of George Floyd’s death. The study found a sharp uptick in requests for books by and about Black Americans, but also in requests for books about Latinos, Asians, Muslims, and Jews.

More than 90 percent of these projects were fully funded, translating to $3.4 million spent on books that reached more than a half-million students.

Some books present multifaceted portrayals of characters of color; others, stereotypes

When people of color and women are present in children’s media, how they’re portrayed varies widely, the New America report finds.

History textbooks don’t often cover Black Americans’ resistance to race-based oppression, outside of the context of the Civil Rights movement. Textbooks also portray attacks on Black people “as if they are isolated events.” In descriptions of the colonial period, Native Americans are often shown as racially inferior to white colonists. Other racial groups are mostly missing from U.S. history textbooks—one study found that Latinos are generally only referenced in relation to immigration and labor movements, for example.

Children’s books show a different picture. Surveys looking at these books have found many examples of multifaceted, positive, and affirming depictions of people of color: books about family and community life, books that accurately portray lesser-known historical events, books that feature characters with a variety of experiences and perspectives.

Some of these trends are the result of relatively recent changes; for example, a 2018 study found that fewer books depict Asian Americans as “foreigners” than in years past. Other studies found that books about characters who shared the same racial or ethnic identity as the author—often called “own voices” stories—presented more positive portrayals.

But books with stereotypes still abound. In stories about Native Americans, Native peoples are often described as aggressive, and traditions from different tribal groups are often mixed together. Some books about Asian Americans uphold the “model minority” stereotype. Stories about Native Hawaiians often exoticize their culture.

Portrayals are also often one-dimensional. A 2018 study from researchers at Bates College in Maine found that races and ethnicities were slotted into different themes in children’s books. For example, most books about experiences of oppression featured Black characters. And while a lot of books about culture and heritage featured Latino characters, there weren’t as many biographies about Latino figures.

Diversity within racial and ethnic groups also isn’t always explored. For example, Armstrong said, most Asian Americans in children’s books are East Asian, without much representation of South or Southeast Asians. That portrayal can frame readers’ perception of who counts as “Asian American,” and who doesn’t, Armstrong said.

“We still need to do a lot of work in terms of having more diverse representation, and in seeing how different communities are represented in the American story,” she said.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

IFLA Literacy and Reading Section Blog

An informal and interactive exchange on issues surrounding libraries, literacy and reading across the world, bicop representation in children’s books.

The modest increases in diversity in children’s literature continued in 2023, according to the latest Diversity Statistics report released by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC). In 2023, 49 percent of the books the CCBC documented had significant BIPOC content (up from 46 percent in 2022) and 40 percent had at least one BIPOC primary character (up from 39 percent in 2022). The number of books with at least one BIPOC creator was about the same as 2022. Those numbers continue the trend of slow growth in representation year to year. In 2022, the books with significant BIPOC content went up two percent (from 44 to 46) while BIPOC primary characters jumped three percent (from 36 to 39). For this report, the CCBC analyzed 3,491 books for children and teens that were published in 2023. For details, go to https://www.slj.com/story/Books%20%26%20Media/BIPOC-Representation-Childrens-Literatures-Continues-Its-Slow-rise-According-CCBC-Diversity-Statistics

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

share this!

December 15, 2021

60 years of children's books reveal persistent overrepresentation of male protagonists

by Public Library of Science

An analysis of thousands of children's books published in the last 60 years suggests that, while a higher proportion of books now feature female protagonists, male protagonists remain overrepresented. Stella Lourenco of Emory University, U.S., and colleagues present these findings in the open-access journal PLOS ONE on December 15, 2021 and explore the factors associated with representation.

A large body of evidence points to a bias in male versus female representation among protagonists in children's books published prior to 2000. However, evidence is lacking as to whether that bias has persisted. In addition, it has been unclear which factors, such as author gender, may be associated with male versus female protagonists.

To help clarify whether gender bias still exists in American children's literature, the authors conducted a statistical analysis of the frequency of male versus female protagonists in 3,280 books, aimed for audiences aged 0 to 16 years and published between 1960 and 2020. They selected books that can be purchased online in the United States, either as hard copies or as digital books, and primarily written in English (<1% written in multiple languages). To enable direct comparison of the rates of appearance of male versus female central characters, they focused on books featuring a single central protagonist, and also only included books for which the gender of the book author was identifiable and matched for all authors if there was more than one.

The analysis found that, since 1960, the proportion of female central protagonists has increased—and is still increasing—but books published since 2000 still feature a disproportionate number of male central protagonists.

The researchers also found associations between the ratio of male versus female protagonists and several relevant factors. Specifically, they found that gender bias is higher for fiction featuring non-human characters than for fiction with human characters. Meanwhile, non-fiction books have a greater degree of gender bias than fiction books, especially when the characters are human.

Books by male authors showed a decline in bias since 1960, but only in books written for younger audiences. Books by female authors also declined in bias over time, ultimately with more female than male central protagonists featured in books for older children and in books with human characters.

These findings could help guide efforts toward more equitable gender representation in children's books, which could impact child development and societal attitudes. Future research could build on this work by considering reading rates of specific books, as well as books with non-binary characters.

The authors add: "Although male protagonists remain overrepresented in books written for children (even post-2000), the present study found that the male-to-female ratio of protagonists varied according to author gender, age of the target audience, character type, and book genre. In other words, some authors and types of books were more equitable in the gender representation of protagonists in children 's books ."

Journal information: PLoS ONE

Provided by Public Library of Science

Explore further

Feedback to editors

A microbial plastic factory for high-quality green plastic

4 hours ago

Can the bias in algorithms help us see our own?

6 hours ago

Humans have converted at least 250,000 acres of estuaries to cities and farms in last 35 years, study finds

7 hours ago

Mysterious bones may have belonged to gigantic ichthyosaurs

Hurricane risk perception drops after storms hit, study shows

Peter Higgs, who proposed the existence of the 'God particle,' has died at 94

Scientists help link climate change to Madagascar's megadrought

9 hours ago

Heat from El Niño can warm oceans off West Antarctica—and melt floating ice shelves from below

10 hours ago

Peregrine falcons expose lasting harms of flame retardant use

11 hours ago

The hidden role of the Milky Way in ancient Egyptian mythology

Relevant physicsforums posts, what are your favorite disco "classics".

8 hours ago

Cover songs versus the original track, which ones are better?

Interesting anecdotes in the history of physics.

15 hours ago

Biographies, history, personal accounts

Apr 7, 2024

Purpose of the Roman bronze dodecahedrons: are you convinced?

Apr 6, 2024

Favorite Mashups - All Your Favorites in One Place

Apr 5, 2024

More from Art, Music, History, and Linguistics

Related Stories

Study shows stories written by children are more likely to have male characters

Aug 10, 2021

Persistent gender bias found in scientific research and related course materials: A long-term linguistic analysis

Dec 6, 2021

In review of 100 best-selling picture books, female protagonists are largely invisible

Jun 3, 2019

Studies of children's stories shows differences in Russian, U.S. approaches to emotion

Dec 2, 2021

AI tools reveal lack of non-white, non-male characters in 'mainstream' books

May 27, 2021

Male physicians refer patients to male surgeons at disproportionate rates, study shows

Nov 10, 2021

Recommended for you

First languages of North America traced back to two very different language groups from Siberia

14 hours ago

The 'Iron Pipeline': Is Interstate 95 the connection for moving guns up and down the East Coast?

13 hours ago

Americans are bad at recognizing conspiracy theories when they believe they're true, says study

Apr 8, 2024

Earth, the sun and a bike wheel: Why your high-school textbook was wrong about the shape of Earth's orbit

Giving eyeglasses to workers in developing countries boosts income

Let us know if there is a problem with our content.

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Phys.org in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Sixty years of gender representation in children’s books: Conditions associated with overrepresentation of male versus female protagonists

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Psychology, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey, United States of America

Roles Validation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Psychology, Emory University, Druid Hills, Georgia, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

- Kennedy Casey,

- Kylee Novick,

- Stella F. Lourenco

- Published: December 15, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260566

- Reader Comments

As a reflection of prominent cultural norms, children’s literature plays an integral role in the acquisition and development of societal attitudes. Previous reports of male overrepresentation in books targeted towards children are consistent with a history of gender disparity across media and society. However, it is unknown whether such bias has been attenuated in recent years with increasing emphasis on gender equity and greater accessibility of books. Here, we provide an up-to-date estimate of the relative proportion of males and females featured as single protagonists in 3,280 children’s books (0–16 years) published between 1960–2020. We find that although the proportion of female protagonists has increased over this 60-year period, male protagonists remain overrepresented even in recent years. Importantly, we also find persistent effects related to author gender, age of the target audience, character type (human vs. non-human), and book genre (fiction vs. non-fiction) on the male-to-female ratio of protagonists. We suggest that this comprehensive account of the factors influencing the rates of appearance of male and female protagonists can be leveraged to develop specific recommendations for promoting more equitable gender representation in children’s literature, with important consequences for child development and society.

Citation: Casey K, Novick K, Lourenco SF (2021) Sixty years of gender representation in children’s books: Conditions associated with overrepresentation of male versus female protagonists. PLoS ONE 16(12): e0260566. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260566

Editor: Jennifer Steele, York University, CANADA

Received: April 1, 2021; Accepted: November 12, 2021; Published: December 15, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Casey et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All data and materials are publicly available on the Open Science Framework ( https://osf.io/97gfk/ ).

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Despite roughly equal numbers of males and females across the world’s population [ 1 ], women are underrepresented in a variety of consequential domains. For example, men outnumber women in STEM disciplines [ 2 , 3 ], politics [ 4 , 5 ], and top-ranking corporate jobs [ 6 ]. Such male overrepresentation is especially pervasive in media, including primetime television programming and television commercials [ 7 , 8 ], virtual platforms [ 9 , 10 ], and sports news coverage [ 11 ]. Often referred to as ‘symbolic annihilation’, disproportionate gender representation negatively impacts women (and men alike) by sustaining explicit and implicit biases against the female gender and diminishing women’s sense of self-worth and belonging [ 12 ].

Symbolic annihilation is also readily apparent in media targeted towards children, where the negative consequences on self-worth and belonging may be especially detrimental [ 13 ]. Accumulating evidence suggests that, in children’s literature, male characters are more prevalent than female characters [ 14 – 20 ], including in titles and illustrations [ 21 ]. In the largest study to date, McCabe et al. [ 22 ] examined the gender representation of central characters as indicated by the title, book description, and/or storyline. Their analysis included 5,618 books published between 1900 and 2000 from three sources: Caldecott award-winning books, Little Golden Books, and the Children’s Catalog. McCabe and colleagues found that male protagonists were overrepresented compared to female protagonists across all sources. There was some improvement in the frequency of female characters across the twentieth century, but even the more recent books in their sample (i.e., 1990–1999) depicted male characters with greater frequency (male-to-female ratio ≈ 1.2:1).

Importantly, McCabe and colleagues also found that specific book features affected the proportion of male and female central characters. In particular, the gender bias was larger when central characters were depicted as non-human animals instead of humans, or as adults instead of children. In another study, Hamilton et al. [ 23 ] examined the role of author gender on the proportion of male and female protagonists. Across a sample of 200 children’s books published between 1995 and 2001, they reported that female authors depicted male and female characters in comparable numbers, whereas male authors overrepresented male characters. Such findings are consistent with a broader literature suggesting that women are paramount in promoting diversity. For instance, female role models in STEM encourage more female representation [ 24 , 25 ], and the presence of women in key positions, including hiring and colloquium committees, improves institutional performance and results in more diverse employees and speakers [ 26 ].

Other studies, however, have failed to find an effect of author gender on gender representation of characters in children’s books [ 27 – 29 ], raising questions about the robustness of this potential moderator. It is worth noting that these studies included books published prior to 1995, during which time female authors may have been underrepresented [ 15 ]. Thus, it is an open question whether author gender impacts the gender bias in children’s books, as might be expected, and importantly, to what extent such an effect may have changed over time, particularly in more recent years when the number of female authors is likely to have grown.

The differential frequency of male and female characters in media might be less consequential if the accompanying content counteracted the disproportionate numbers. However, studies examining the content of children’s literature report stereotypical portrayals of male and female characters [ 17 , 30 ]. For example, males are more likely to be the bread-winners across a broad range of professions and to be depicted outdoors and as adventurous. By contrast, females are typically depicted indoors and as filling domestic roles, such as performing household chores and caring for children [ 23 , 29 , 31 , 32 ].

Despite ample evidence of gender bias in children’s books prior to 2000, there is a dearth of evidence post 2000. Moreover, the evidence that does exist post 2000 is contradictory, with some data suggesting little or no improvement in the frequency of female characters [ 33 ] and other data suggesting that the numbers of male and female characters have reached parity [ 34 ]. A potential explanation for the discrepancy is that these studies have been limited in scope, with potentially confounding variables, such as character type and author gender, not accounted for in the analyses. Previous studies have also typically focused on award-winning books or restricted their sample to only those books available in a single library or school [e.g., 23 , 32 , 35 ], potentially leading to unrepresentative estimates of gender distribution.

Present study

In addition to the impact on reading ability and language development [ 36 ], children’s books have long been considered an important source of enculturation [ 37 , 38 ]. With increasing accessibility of children’s books [ 39 ], questions related to trends in gender representation are of special importance, especially if we are to understand the early forces of gender bias and how best to overcome their cognitive and affective consequences. Thus, the present study sought to provide an updated account of the gender representation in the literature targeted towards children within the last 60 years: 1960 to 2020, with a particular focus on books published post 2000 and on books featuring a single protagonist to allow for direct comparison of the rates of appearance of male versus female central characters.

In order to obtain a representative sample of the books available to children, we analyzed books accessible online for hard copy purchase or digital reading. This approach was used to gauge widespread trends in gender representation across the 60-year period of interest, and it is an approach that overcomes limitations of previous studies, which have typically restricted their analyses to award-winning titles or books available in a specific library or school setting. Although the current approach does not guarantee a direct link to reading rates, it nevertheless addresses a critical question about publication—namely, whether books featuring male versus female protagonists are more likely to be published. Addressing this question is a crucial first step in increasing our understanding of gender bias and the potential impact on cognitive and emotional development.

As noted above, previous research points to the importance of considering moderating variables when characterizing bias in the representation of central characters. We would argue that the potential influence of moderators is especially critical when considering trends across time. Following previous research, we analyzed potentially relevant variables, including author gender (male vs. female) and character type (human vs. non-human). We also included age of the target audience as well as book genre (fiction vs. non-fiction), which, to our knowledge, have not been previously examined. Books targeted to children include those suitable for infants and young toddlers, which may feature more non-human than human characters and may more often be fiction than non-fiction. Given other research suggesting that males are overrepresented when characters are non-human, at least in fiction, the prediction was that books targeted to young children might be less equitable in the representation of male and female characters than books targeted to older children, which could be particularly consequential for our understanding of the early roots of gender biases.

To summarize, the primary aims of the present study were two-fold: (1) to provide an up-to-date estimate of the rates of gender representation in books published within the last two decades, relative to earlier years; and (2) to examine the effect of potential moderators of gender representation across this timeframe. By analyzing trends in the publication of books featuring male versus female protagonists over the last 60 years, while also considering the influence of previously unexamined variables, such as age of the target audience and book genre, we can better understand where (if at all) progress towards gender parity has been most successful and identify where future work may be needed to achieve equitable gender representation in children’s books.

All data and materials are publicly available on the Open Science Framework ( https://osf.io/97gfk/ ). We report all measures collected, along with exclusion information below.

Web search.

We conducted an entirely web-based analysis of the gender representation of central characters in children’s books published between 1960 and 2020. In order to obtain a large, representative sample of books available to children, we included titles from a variety of sources: award winners, best sellers from top retailers at the time of collection (e.g., Amazon and Barnes & Noble), specific recommendations to parents or teachers, and publishing catalogs. As an indicator of representativeness, there is substantial overlap between the current sample and existing children’s book corpora, including all titles from the Wisconsin Children’s Book Corpus [ 30 ] and the Montag corpus [ 40 ], as well as over 300 titles from the Infant Bookreading Database [ 41 ].

Inclusion criteria.

Following the convention established in previous work [e.g., 22 ], we restricted the present analyses to only those books with a single identifiable protagonist. We chose to maintain this approach because this is arguably the most blatant indicator of gender bias in publication, and when considering the potential influence on children’s perception of gender in children’s books, the impact of a single gender is more straightforwardly interpreted than the genders of multiple characters. Recent work suggests that the central character’s gender strongly influences young children’s learning of gender stereotypes [ 42 ], while the relative influence of multiple gendered characters has not been established. Additionally, we only included books for which the gender of the book author was identifiable and matched for all authors if there was more than one (see below for details).

Our search parameters included books, primarily written in English (<1% written in multiple languages) and available for purchase in the United States, that: (1) featured a single protagonist, (2) were published between 1960 and 2020, and (3) were targeted to children ranging in age from 0 to 16 years. All search queries were conducted in Summer 2019 and yielded 6,580 unique hits from 67 sources (see OSF for links). However, a large proportion of books ( n = 2,998) captured by these sampling methods failed to meet our pre-defined inclusion criteria, most often due to the fact that the books featured multiple central characters ( n = 2,801) or were published outside the 60-year window of interest ( n = 196). For transparency, we report the full list of these unanalyzed titles (see OSF).

Additional exclusions were required for the following reasons: ungendered central character ( n = 161), multiple authors with different genders ( n = 68), ungendered author ( n = 37), indeterminable author gender ( n = 3), adult target age range ( n = 1), or indeterminable target age range ( n = 33). Thus, the final sample consisted of 3,280 children’s books published between 1960 and 2020 with either a male or female central character (see OSF for full dataset). The sample includes multiple books in a given series. This decision was made to account for the fact that the central character could theoretically change across publications (e.g., The Baby-Sitter’s Club ). The majority of books ( n = 2,638) were published in the year 2000 or later, ensuring an up-to-date sample. Given the range of publication dates, the size of our dataset was comparable to that of McCabe et al. [ 22 ], currently the largest study on gender representation of central characters in children’s books.

Of the titles meeting inclusion criteria for analysis ( n = 3,280), we coded for: (1) gender of central character, (2) publication year, (3) gender of book author, (4) age of target audience, (5) character type (human vs. non-human), and (6) book genre (fiction vs. non-fiction).

Coding decisions for each variable were made based on information provided in the title, description, front or back cover, and/or dust jacket. As needed, further clarification was sought from the book itself (when freely accessible online), or additional Google searches were conducted to supplement the information found in the book description (e.g., to determine author gender if pronouns were not provided or to determine the original publication year if the book was a reprint edition). A detailed description of the coding guidelines is available on OSF, and a breakdown of the characteristics of our sample by variable of interest is provided in Table 1 .

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260566.t001

Gender of central character.

After identifying each book’s protagonist (i.e., the character highlighted in the book description and/or featured in the book title), the central character’s gender was categorized as male or female based on available information. Critically, gender coding was based solely on textual information, as in previous research. We avoided reliance on visual cues since gender judgments from illustrations are particularly susceptible to cultural assumptions as well as personal conceptions of gender stereotypicality [ 15 ]. Gender coding decisions were made based on normative understandings of gendered nouns (e.g., boy , girl ) and pronouns (e.g., he , she ). If no explicit, text-based gender identification was provided other than the name of the character, then we determined gender based on whether the name was commonly recognized as masculine or feminine (as done by [ 23 ]). For instances in which the central character’s name was gender-ambiguous, where no name was provided, or where the character was ungendered or identified as non-binary, books were excluded from further analysis ( n = 161, or 2.45% of the dataset).

Publication year.

We coded publication year as the original publication date. In the case of reprints, the publication year was coded as the original, so long as the author and content of the book did not change in the newer edition. Conversely, for adaptations of classic stories, the latest publication year was coded, and author credit was given to the adapter, rather than the original author, since more recent publications could involve updates to the gender of the protagonist or other variables of interest (e.g., character type or target audience). As noted above, all books were published or reprinted between 1960 and 2020.

Gender of book author.

As for the gender of the central character, author gender was coded as male or female according to the gender pronouns, and if necessary, based on the author’s name. For books with multiple authors, books were excluded from all analyses if both male and female individuals held authorship ( n = 68, or 1.03% of the dataset) but were retained if all authors identified with the same gender. For books where the author was listed as a publishing company or an organization, or when the author used gender-neutral pronouns, books were excluded from further analysis ( n = 40, or 0.61% of the dataset). Illustrator gender was not coded since the present investigation relied solely on textual information to examine gender representation.

Age of target audience.

We coded the minimum and maximum age of children (in years) for which the book was recommended. We then characterized target audience using six age groups and determined coding according to the minimum age recommendation since some sources used the form ‘X and up’ to specify the target age range: infant/toddler (0 to 2 years), preschool (3 to 5 years), early elementary (6 to 8 years), middle elementary (9 to 10 years), late elementary (11 to 12 years), and teen (13 to 16 years). All analyses reported below use minimum age to categorize target audience group, though the results are qualitatively similar when categorized according to the average of the minimum and maximum ages, or when age is instead treated as a continuous variable. Because of the smaller number of books for teens in our sample, as a robustness check, we ran all analyses on the full set (including teens) and the subset of books targeted to children under age 13. All reported effects hold when the books for teens are excluded, unless otherwise indicated.

Character type.

Character type was coded as either human or non-human . Following [ 43 ], the non-human category not only included animals but also inanimate objects (e.g., vehicles, toys, plants).

Genre was coded as either fiction or non-fiction . Coding was determined based on the explicit genre classification (when provided), or based on the presence of fantastical elements ( fiction ) versus facts about a real-life individual or stories based on true events ( non-fiction ).

Reliability

The primary coder performed the initial exclusion and coded all remaining titles. To ensure satisfactory coding reliability, a randomly selected 30% of books meeting inclusion criteria were re-coded by a second coder, blind to the primary coder’s responses. Inter-rater reliability was high (α > 0.90 for all variables of interest). Additionally, the second coder re-coded a randomly selected 30% of excluded books to confirm reliability in determining whether books met inclusion criteria for analysis (α > 0.95). Discrepancies were resolved by discussion between the two coders. Additional arbitration by a third party was only needed for three items.

Descriptive analyses

In preliminary analyses, we examined whether the distribution of children’s books for the variables of interest varied across time. Binomial logistic regression revealed that the proportion of female authors, relative to male authors, increased between 1960 and 2020 ( B = 0.02, Z = 5.04, p < .001, OR = 1.02, 95% CI = [1.01, 1.02]; Fig 1A ) and so, too, did the proportion of non-fiction books, relative to fiction ( B = 0.04, Z = 8.48, p < .001, OR = 1.04, 95% CI = [1.03, 1.05]; Fig 1B ). The proportion of books targeted to older children (ages 9+), compared to younger children, did not vary during this time period ( B = 0.004, Z = 0.98, p = .327, OR = 1.004, 95% CI = [1.00, 1.01]; Fig 1C ), nor did the proportion of books with human versus non-human protagonists ( B = 0.005, Z = 1.53, p = .127, OR = 1.005, 95% CI = [1.00, 1.01]; Fig 1D ).

Individual points reflect proportion estimates for each year. Shaded regions show standard errors of binomial logistic regression model fits.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260566.g001

These analyses also revealed that the books written by male authors included relatively more non-human characters than did books written by female authors ( B = 0.61, Z = 6.98, p < .001, OR = 0.55, 95% CI = [0.46, 0.65]; S1A Fig ). There were also more non-human characters in fiction ( B = 2.60, Z = 11.77, p < .001, OR = 13.44, 95% CI = [8.94, 21.33]; S1B Fig ) and in books targeted to younger children ( B = 1.32, Z = 18.07, p < .001, OR = 3.74, 95% CI = [2.25, 4.32]; S1C Fig ).

Male-to-female ratio of protagonists across time

In subsequent analyses, we addressed our first question of interest: has the gender representation in children’s books become more equitable over time? A binomial logistic regression analysis revealed that the ratio of male to female central characters changed significantly over the sampled time frame, such that the proportion of male protagonists decreased between 1960 and 2020, reflecting a trend towards parity, B = -0.02, Z = -4.63, p < .001, OR = 0.99, 95% CI = [0.98, 0.99] ( Fig 2 ). Because a critical contribution of the present study was the examination of gender representation in books published post 2000, we also ran this analysis on this most recent subset of books. In the time period from 2000 to 2020, we found the same significant trend towards parity, suggesting that progress towards equitable representation has continued rather than plateaued in the last two decades, B = -0.02, Z = -3.35, p < .001, OR = 0.98, 95% CI = [0.96, 0.99]. Nevertheless, female protagonists remain underrepresented in the most recently published books ( male-to-female ratio = 1.22:1 for the last decade, and 1.12:1 for the last five years).

Individual points reflect proportion estimates for each year. The dotted line at 0.5 denotes parity. The shaded region shows the standard error of the binomial logistic regression model fit.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260566.g002

Moderators of the male-to-female ratio of protagonists

The next set of analyses targeted our second question of interest by examining the extent to which author gender (male vs. female), target audience (age of children), character type (human vs. non-human), and genre (fiction vs. non-fiction) affected the male-to-female ratio of central characters. First, we tested whether each variable independently predicted the male-to-female ratio. A binomial regression model with the four potential moderators as predictors (publication year not included in this analysis) revealed a significant effect for each of the variables tested. Our results clearly demonstrated that the male-to-female ratio was larger for books authored by men compared to women, B = 1.27, Z = 15.63, p < .001, OR = 3.57, 95% CI = [3.05, 4.20] ( Fig 3A ). As in previous studies, we also found that the male-to-female ratio was larger when the central character was non-human compared to human, B = 0.96, Z = 10.01, p < .001, OR = 2.60, 95% CI = [2.16, 3.15] ( Fig 3B ). We found a larger male-to-female ratio for non-fiction compared to fiction books, B = 0.29, Z = 3.46, p < .001, OR = 1.33, 95% CI = [1.13, 1.57] ( Fig 3C ). Moreover, we found that the male-to-female ratio was larger for books targeted to younger children than older children, B = -0.13, Z = -3.86, p < .001, OR = 0.88, 95% CI = [0.83, 0.94] ( Fig 3D ). See the next set of analyses for additional context in relation to these main effects.

The dotted line reflects parity (1:1 male-to-female ratio). Error bars denote 95% confidence intervals for ratio estimates.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260566.g003

We then tested a binomial logistic regression model with all four moderators (i.e., author gender, target audience, character type, genre) and publication year included as predictors. These analyses revealed four significant two-way interactions, described in detail below. No other two- or three-way interactions reached statistical significance (all p s >.05). Notably, these null interactions included those with publication year, suggesting persistent effects of the moderators of the male-to-female ratio across time.

First, we found a significant two-way interaction between author gender and target audience, B = 0.39, Z = 4.64, p < .001, OR = 1.48, 95% CI = [1.26, 1.76] ( Fig 4A ). Male authors overrepresented male protagonists across all age groups, and there was a trend of increasing male overrepresentation as a function of the age of the target audience in books authored by males, though this effect did not reach statistical significance ( B = 0.11, Z = 1.81, p = .071, OR = 1.12, 95% CI = [0.99, 1.27]). Conversely, female authors showed significantly less male overrepresentation as the age of the target audience increased ( B = -0.25, Z = -5.88, p < .001, OR = 0.78, 95% CI = [0.71, 0.84]).

The dotted line at 0.5 denotes parity. Error bars denote 95% confidence intervals for proportion estimates.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260566.g004

Second, there was a significant two-way interaction between author gender and character type, B = 0.52, Z = 2.35, p = .019, OR = 1.68, 95% CI = [1.09, 2.59] ( Fig 4B ). Male authors depicted more male protagonists regardless of character type ( male-to-female ratio : human = 2.95:1, χ 2 = 107.98, p < .001; non-human = 4.19:1, χ 2 = 66.87, p < .001). By contrast, female authors only showed male overrepresentation for non-human protagonists (2.27:1, χ 2 = 17.75, p < .001). When the characters were human, they depicted more female protagonists (0.75:1, χ 2 = 28.32, p < .001).

Third, there was a significant two-way interaction between character type and genre, B = 1.64, Z = 3.54, p < .001, OR = 5.13, 95% CI = [2.06, 12.86] ( Fig 4C ), such that there was male overrepresentation in fiction but only if the characters were non-human ( male-to-female ratio = 3.09:1, χ 2 = 93.24, p < .001). Importantly, there was also male overrepresentation in non-fiction when the characters were human (1.73:1, χ 2 = 28.02, p < .001). By contrast, there was gender parity in fiction when the characters were human (0.95:1, χ 2 = 0.51, p = .473) and in non-fiction when the characters were non-human (1:1, χ 2 = 0.00, p = 1.00).

Fourth, there was a significant two-way interaction between genre and target audience, B = 0.20, Z = 2.01, p < .001, OR = 1.22, 95% CI = [1.26, 1.76] ( Fig 4D ). The overrepresentation of male protagonists in non-fiction increased as age of the target audience increased, though this effect did not reach statistical significance ( B = 0.15, Z = 1.79, p = .074, OR = 1.16, 95% CI = [0.99, 1.36] except when books for teens were excluded from the analysis ( B = 0.21, Z = 2.34, p = .019, OR = 1.23 [1.04, 1.47]). However, male protagonists tended to be overrepresented in fiction books targeted to younger children, and overrepresentation decreased as the age of the target audience increased ( B = -0.21, Z = -5.65, p < .001, OR = 0.81, 95% CI = [0.75, 0.87]).

Moderators across time

The aforementioned effects did not indicate any interactions with publication year, suggesting stability of these effects across time. However, these previous analyses do not address whether the individual moderators were associated with reduced male overrepresentation across time, as suggested by the main effect of publication year ( Fig 2 ). To this end, we examined each moderator, and the corresponding interactions, across time. Moreover, as a robustness check, and given the focus of the present study, we also conducted all subsequent analyses on the subset of books published between 2000 and 2020. The reported effects hold for the most recent decades unless otherwise indicated.

First, to better understand the effect of author gender, we compared male and female authors when books were written for younger versus older children ( Fig 5A ) and when the books involved human versus non-human protagonists ( Fig 5B ). We found that, across time, both male and female authors decreased their overrepresentation of male characters in books targeted to younger children, but only the effect for male authors reached statistical significance ( B = -0.02, Z = -2.52, p = .012, OR = 0.98, 95% CI = [0.97, 1.00]). However, in more recent years (i.e., 2000–2020), only female authors were found to significantly decrease their overrepresentation of male characters in books for younger children. Although male authors consistently overrepresented male characters in books for older children across the entire 60-year period, female authors decreased their overrepresentation of male characters in these books over time ( B = -0.03, Z = -2.76, p = .006, OR = 0.97, 95% CI = [0.95, 0.99]). Additionally, we found that only female authors significantly decreased their overrepresentation of male human characters across time ( B = -0.01, Z = -2.32, p = .021, OR = 0.99, 95% CI = [0.98, 1.00]); however, this effect did not hold when books targeted to teens were excluded from this analysis. Neither male nor female authors significantly decreased their representation of male non-human characters, but when books targeted towards teens were excluded from this analysis, we found a significant trend towards parity for male authors ( B = -0.02, Z = -1.96, p = 0.0499, OR = 0.98, 95% CI = [0.96, 0.99]) and a marginal trend for female authors ( B = -0.02, Z = -1.77 p = 0.077, OR = 0.98, 95% CI = [0.95, 1.00]). Altogether, these analyses revealed that the changes over time were largely consistent for male and female authors. The main difference is that female authors showed less male overrepresentation, except when writing books featuring non-human central characters.

The dotted line at 0.5 denotes parity. The shaded regions show standard errors of binomial logistic regression model fits.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260566.g005

Next, we further examined the effect of book genre. We compared fiction and non-fiction books when they involved human versus non-human characters ( Fig 5C ) and when the target audience was younger versus older children ( Fig 5D ). We found that, across time, overrepresentation of male characters in fiction books significantly decreased for human ( B = -0.02, Z = -4.73, p < .001, OR = 0.98, 95% CI = [0.97, 0.99]) and non-human characters ( B = -0.02, Z = -2.45, p = .014, OR = 0.98, 95% CI = [0.97, 1.00]), but these effects did not hold when considering only the subset of books published within the last two decades. By contrast, overrepresentation of male characters in non-fiction books, both human and non-human, did not decrease significantly across the entire 60-year period, though there was a significant decrease in male overrepresentation in non-fiction books featuring human characters when only considering the last two decades ( B = -0.03, Z = -2.35, p = 0.019, OR = 0.97, 95% CI = [0.94, 0.99]). We found a similar effect of book genre in relation to age of the target audience, where only changes for fiction books reached statistical significance for the entire 60-year period. That is, male overrepresentation decreased in fiction books for both younger ( B = -0.02, Z = -4.21, p < .001, OR = 0.985, 95% CI = [0.98, 0.99]) and older children ( B = -0.02, Z = -2.63, p = .008, OR = 0.98, 95% CI = [0.96, 0.99]) across the last 60 years, though the effect for younger children did not hold in the most recent subset of books (i.e., 2000–2020). Altogether, these analyses revealed that trends across time were largely consistent in fiction and non-fiction books, but that statistically significant changes in gender representation were seen only in fiction books across the full 60-year period.

How has gender representation changed in the last 60 years?

Our findings demonstrate that the male-to-female ratio of central characters has improved in the children’s books published between 1960 and 2020. During this time, there has been an increasing trend towards parity, though male protagonists remain overrepresented compared to female protagonists. Our findings are consistent with other research suggesting androcentrism in media, even post 2000 [ 44 ].

Importantly, we also found that particular combinations of author gender, target audience, character type, and genre impacted the male-to-female ratio throughout this 60-year period. Previous studies have investigated character type and author gender, but the impact of book genre and target audience on gender representation has remained largely unexplored. Our findings reveal important effects of all the variables of interest. We found that non-human characters are overrepresented as male, but only in fiction books, though overrepresentation has decreased across time. Moreover, human characters are also overrepresented as male, at least in non-fiction books. Thus, it appears to be the combination of character type and genre that results in significant male overrepresentation, rather than character type or genre alone.

Finally, although previous findings have suggested that female authors represent male and female characters at equitable rates [ 23 , 34 ], no study to date has discussed the interaction between author gender and other important variables, namely character type and target audience. Our findings revealed that male authors showed improvement in the male-to-female ratio of central characters across the 60-year period, but this was limited to books targeted to younger children. Female authors also showed improvement during this time and even depicted more female protagonists, at least with human characters and in books for older children, though there was no significant improvement in books with non-human characters (where male overrepresentation remains). Taken together, the results from the current study suggest important multiple confluences of gender representation in children’s books.

Patterns of gender representation explained

Although significant progress towards gender parity was observed, it is notable that, overall, male protagonists have been overrepresented in children’s books across the last 60 years, between 1960 and 2020. During this time, women have made great social and economic strides. There have been multiple waves of feminist movements [ 45 ], and social media has emerged as a mechanism by which to promote feminist doctrine broadly and expediently [ 46 ]. So, why does the gender bias in the literature targeted towards children persist?

One straightforward reason is that gender stereotypes persist in society. Even if explicit gender discrimination occurs less frequently today than in the past, implicit attitudes about females being submissive and less worthy than males remain pervasive [ 47 , 48 ]. Consistent with this possibility is the observation that males are considered more prototypical than females when categorizing humans [ 49 ]. Such attitudes could result in male overrepresentation in children’s books, with male characters appearing as the default. They may also explain why ambiguous contexts are more likely to be interpreted as male [ 50 ]. For example, mothers refer to gender-unspecified animal characters as male when reading or discussing books with their children [ 51 ], as do children themselves [ 52 ].

Persistent overrepresentation of male characters could also be a historical artifact. Older books, which may reflect the cultural dominance of male figures of years past, have remained popular and continue to be published, such that the overrepresentation of male characters may reflect an earlier perspective. Older books may be adapted and reprinted, and in the current dataset, some of these books were coded according to their most recent publication date. Future research should consider analyzing these books separately to determine the extent to which the reprints of older books (and persisting popularity of classic stories) contribute to continued male overrepresentation.

Another potential explanation for the greater male representation in children’s books is that books with male central characters sell better, such that publishers will be motivated to produce more books featuring male protagonists because of their wider appeal [ 53 ]. That such books sell better is consistent with research showing that parents prefer media with male characters and believe that their sons prefer male-oriented books [ 54 ]. Parents’ preferences for books with male characters may stem from their own experience with older, classic books [ 55 ]. Additionally, parents’ assumptions about their sons’ preferences may come directly from boys responding more favorably to books with male characters [ 54 , 56 ] and/or adults’ resistance to boys engaging in stereotypically feminine activities [ 57 ].

Yet another potential reason for male overrepresentation is that it reflects linguistic properties. In English, female is the marked (irregular) category because the affix “fe” is added to the unmarked (standard) form of “male”. Thus, authors may default to using male characters because male word forms are considered the norm. Even children default to using male word forms indiscriminately [ 58 , 59 ]. The challenge with the male generic is that even when intended to inclusively refer to all genders, the gender bias in prototypicality may lead people to interpret the male generic as referring specifically to males [ 60 ].

Although the aforementioned explanations do well to account for general male overrepresentation in children’s books, what is needed is an account that illuminates the variation across the different combinations of variables. In particular, explanations are needed for why there is greater parity for human characters when the books are fiction and for non-human characters when the books are non-fiction. Moreover, why do female authors show greater parity than male authors, especially in books targeted to older children and in books featuring human protagonists?

We suggest that although there are historical, linguistic, and economic forces working in favor of male overrepresentation, there is also cultural awareness of gender bias. With such awareness, there may be a motivation to ensure parity in the gender of children’s book characters. Yet, implementation of such parity may be more straightforward in specific contexts. Our data point to two such contexts: with human characters in fiction and with non-human characters in non-fiction. It may be easier to depict female human characters in fictional stories because authors need not adhere to real events in which there is greater prevalence of men in particular professions or scenarios. Similarly, when the stories are non-fiction, authors may have greater flexibility in representing characters when they are non-human (e.g., by describing facts about a female animal, such as A Mother’s Journey by Sandra Markle).

It is also important to note that some of the aforementioned effects depend critically on author gender. From 1960 to 2020, male authors consistently overrepresented central characters as male in books targeted to children of all ages. The overrepresentation of male characters (e.g., superheroes) in such contexts may reflect male authors’ own preferences for male fictitious characters. By contrast, female authors represented the gender of protagonists more equitably and even overrepresented female characters in books targeted to older children. This trend may reflect their beliefs that older children are better able to understand gender inequities and so may benefit from greater female representation. Such a perspective is consistent with other research showing that women (and other minorities) play a significant role in promoting diversity and may be integral in ensuring equity across genders [ 61 ].

Remaining considerations and conclusion

The underrepresentation of female characters in children’s books, and media more generally, has been referred to as ‘symbolic annihilation’ because it is believed to promote the marginalization of women and girls by suggesting that they play a less significant role in society. In the present study, we investigated gender disparity in children’s literature in its most blatant form—the male-to-female ratio of central characters. However, other research suggests that stereotypes permeate children’s books at multiple levels, including text [ 14 , 30 , 62 ] and illustrations [ 32 , 63 ]. Even when female characters appear as protagonists, they are often portrayed as more emotional [ 19 , 30 ], less active [ 64 ], and less associated with STEM [ 63 , 65 ]. Thus, it is not only necessary to strive for equitable representation in the numbers of male and female characters, but also for non-stereotypical depictions of these characters. In fact, recent work suggests that exposure to counter-stereotypical protagonists in books can reduce children’s endorsement of gender stereotypes [ 66 ] and promote less stereotypical behavior [ 67 ].

A notable caveat of the present study is that our analyses do not reflect actual reading rates. In other words, we analyzed children’s books available on the internet to estimate general trends in publication, but some books will be more popular than others, with variation across ages. For example, although we did not find that the male-to-female ratio of central characters depended on an interaction between character type and age of the target audience, it is nevertheless possible that younger children are read more books with non-human characters than older children, and thus may experience greater exposure to male characters. Future research might track which books children of different ages are exposed to in order to determine the conditions under which younger and older children are differentially exposed to unrepresentative samples of book characters.

It is also worth noting that the gender coding in the present study was based on a strict dichotomy of male versus female. Given the limited number of books with non-binary central characters, we did not formally assess this category. However, future research would do well to examine trends in the representation of non-binary protagonists to better understand gender diversity in children’s books. Additionally, the present study focused only on books with a single identifiable male or female protagonist and therefore does not address gender representation at all character levels. In future research, it will be important to examine the relative rates of appearance of gendered characters in shared protagonist (or supporting) roles, as well as how these dynamics may influence children’s perceptions of gender. For instance, female characters may be more likely to appear in stories with multiple protagonists, perhaps reflecting endorsement of stereotypical beliefs about women and girls being more community-oriented [e.g., 68 , 69 ], or may be more likely to be featured as supporting characters [e.g., 21 ]. It is also possible that patterns of representation may differ across cultural contexts [e.g., 70 ], highlighting a need for further characterization of gender representation in children’s books from sources outside of the United States.

In conclusion, our analysis of the frequency of male and female central characters clearly demonstrates that although female representation has improved over the last 60 years, parity has not yet been achieved in all types of books or by all authors. Moreover, and perhaps surprisingly, the determinants of gender representation—author gender, target audience, character type, and book genre—are largely unchanged over this period. Yet, the persistence of these predictors, as indicated by the present study, provides crucial data about where disparities in gender representation remain. Knowledge of these effects may allow publishers and authors to increase their awareness of the susceptibility to gender bias and strive to achieve gender equity in children’s books. Even before trends in publication reach parity, knowledge of these effects may help parents and educators to select less biased samples of books for individual children.

Supporting information

S1 fig. proportion of non-human protagonists in (a) books authored by males vs. females, (b) fiction vs. non-fiction books, and (c) books targeted to specific age ranges of children..

Error bars denote 95% confidence intervals for proportion estimates.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260566.s001

- 1. United Nations, Department of Economic Social Affairs. World population prospects 2019. United Nations; 2019.

- 2. Rivers E. Women, minorities, and persons with disabilities in science and engineering. National Science Foundation. 2017.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 12. Tuchman G. The symbolic annihilation of women by the mass media. Culture and politics: Springer; 2000. p. 150–74.

- 26. Noland M, Moran T, Kotschwar BR. Is gender diversity profitable? Evidence from a global survey. Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper. 2016;(16–3).

- 30. Lewis M, Borkenhagen MC, Converse E, Lupyan G, Seidenberg MS. What might books be teaching young children about gender? 2020.

- 33. Yello N. A contact analysis of Caldecott medal and honor books from 2001–2011 examining gender issues and equity in 21st century children’s picture books. 2012.

- 47. Field A, Tsvetkov Y. Unsupervised discovery of implicit gender bias. arXiv preprint arXiv:200408361. 2020.

- 53. Rider EA. Our voices: Psychology of women: Wadsworth Publishing Company; 2000.

Kids Books Still Have A Lack-Of-Diversity Problem, Powerful Image Shows

Parents Editor, HuffPost Canada

In 1990, scholar Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop wrote that books are mirrors , reflecting our own lives back at us, and that reading is therefore a means of self-affirmation. That idea is the inspiration behind a powerful new image that shows just how badly children’s books are failing our kids.

In the infographic, children of colour gaze skeptically into small and cracked mirrors while, nearby, a white child — and a bear — smile into full-length ones.

It’s based on some troubling, new U.S. publishing statistics that in 2018 there were more children’s books featuring animals and other non-human characters (27 per cent) than all types of visible minorities combined (23 per cent). Meanwhile, half of all the children’s books reviewed featured white kids.

“The positive ‘mirror’ experience is exactly why representation matters. Actually seeing someone who looks like you doing something you never thought of, it can give you the idea that ‘this could be me someday,’” U.S. children’s book illustrator David Huyck , who drew the image, told HuffPost Canada.

Huyck created the image along with Sarah Park Dahlen , a professor in library and information science at St. Catherine University in St. Paul, Minn. Dahlen, who is Korean-American, wrote on her website that the cracks in the mirrors represent how many of the books that do have diverse characters get it wrong.

“Children’s literature continues to misrepresent underrepresented communities, and we wanted this infographic to show not just the low quantity of existing literature, but also the inaccuracy and uneven quality of some of those books,” Dahlen wrote.

To create the infographic, Dahlen and Huyck used data from the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Education Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC), which has been compiling statistics on diversity in U.S. children’s books since 1985.