Advertisement

Natural disasters, resilience-building, and risk: achieving sustainable cities and human settlements

- Original Paper

- Published: 24 May 2023

- Volume 118 , pages 611–640, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Muhammad Tariq Iqbal Khan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8557-3390 1 ,

- Sofia Anwar 1 ,

- Samuel Asumadu Sarkodie 2 ,

- Muhammad Rizwan Yaseen 1 ,

- Abdul Majeed Nadeem 1 &

- Qamar Ali 3

596 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Reducing natural disasters and their related economic losses remains critical to achieving sustainable development. However, there is a lack of comprehensive studies that assess sustainable cities and human settlements in efforts to attain sustainable development goal 11.5. Here, the present research explains the effect of disaster risk and disaster resilience on human loss due to natural disasters (deaths, injured, and affected) in 90 countries spanning 1995 to 2019. We develop global risk and resilience indices through IMF index-making steps across 24 high, 24 upper-middle, 30 lower-middle, and 12 low-income countries. The negative binomial regression shows an increase in disaster-related loss to human beings (deaths, injured, and affected) due to disaster risk in all panels. The empirical results reveal a favorable impact of disaster resilience––resilience declines disaster-related losses in developed countries. We observe that focusing on basic infrastructure, economic stability, public awareness, hygiene practices, ICT, and effective institutions leads to disaster resilience, mitigation, and speedy post-disaster recovery. Due to the insignificant impact of resilience in developing countries, high-income countries could provide financial resources, modern and DRR technologies, especially to low-income economies. This study encourages countries to follow seven targets and four dimensions of the Sendai Framework to enhance disaster resilience.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Early Warning Systems and Their Role in Disaster Risk Reduction

Disaster preparedness of local governments in Panay Island, Philippines

Johnny D. Dariagan, Ramil B. Atando & Jay Lord B. Asis

From Poverty to Disaster and Back: a Review of the Literature

Stéphane Hallegatte, Adrien Vogt-Schilb, … Chloé Beaudet

Availability of data and material

Data will be available upon request.

Aghapour AH, Yazdani M, Jolai F, Mojtahedi M (2019) Capacity planning and reconfiguration for disaster-resilient health infrastructure. J Build Eng 26:100853. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2019.100853

Article Google Scholar

Ahmed J, Jaman MH, Saha G, Ghosh P (2021) Effect of environmental and socio economic factors on the spreading of COVID-19 at 70 cities/provinces. Heliyon 7:e06979. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06979

Alam K, Rahman MH (2017) Chapter 29: the role of women in disaster resilience. In: Madu CN, Kuel C (eds) Handbook of disaster risk reduction & management. World Scientific Publishing, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1142/9789813207950_0029

Chapter Google Scholar

Albuquerque PH, Rajhi W (2019) Banking stability, natural disasters, and state fragility: panel VAR evidence from developing countries. Res Int Bus Finance 50:430–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2019.06.001

Ali Q, Yaseen MR, Anwar S, Makhdum MSA, Khan MTI (2021) The impact of tourism, renewable energy, and economic growth on ecological footprint and natural resources: A panel data analysis. Resour Policy 74:102365

Al-Maruf A (2017) Enhancing disaster resilience through human capital: Prospects for adaptation to cyclones in coastal Bangladesh. University of Cologne, Germany

Google Scholar

Arouri M, Nguyen C, Youssef AB (2015) Natural disasters, household welfare, and resilience: evidence from rural Vietnam. World Dev 70:59–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.12.017

Asadzadeha A, Köttera T, Salehib P, Birkmann J (2017) Operationalizing a concept: The systematic review of composite indicator building for measuring community disaster resilience. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 25:147–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.09.015

Ashmawy IKIM (2020) Stakeholder involvement in community resilience: evidence from Egypt. Environ Dev Sustain 23:7996–8011. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-00894-9

Balaei B, Noy I, Wilkinson S, Potangaroa R (2021) Economic factors affecting water supply resilience to disasters. Socio-Econ Plan Sci 76:100961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2020.100961

Benali N, Abdelkafi I, Feki R (2018) Natural-disaster shocks and government’s behavior: evidence from middle income countries. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 27:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2016.12.014

Birkmann J (2006) Measuring vulnerability to promote disaster-resilient societies: conceptual frameworks and definitions, In: Measuring vulnerability to natural hazards: towards disaster resilient societies; United Nations University: New York, NY, USA

Bonnet J, Coll-Martínez E, Renou-Maissant P (2021) Evaluating sustainable development by composite index: evidence from French departments. Sustainability 13:761. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020761

Cavallo A, Ireland V (2014) Preparing for complex interdependent risks: a system of systems approach to building disaster resilience. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 9:181–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2014.05.001

Centre for research on the epidemiology of disasters (CRED) (2021) EM-DAT The international disaster database. Institute health and society UClouvain, Belgium, www.emdat.be , Accessed 01 April 2021

Chok NS (2008) Pearson’s versus Spearman’s and Kendall’s correlation coefficients for continuous data. M.Sc. thesis, University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the United States

Chowdhury JR, Parida Y, Goel PA (2021) Does inequality-adjusted human development reduce the impact of natural disasters? A gendered perspective. World Dev 141:105394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105394

Chun H, Chi S, Hwang B (2017) A spatial disaster assessment model of social resilience based on geographically weighted regression. Sustainability 9:2222. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122222

Cimellaro GP, Reinhorn AM, Bruneau M (2011) Performance-based metamodel for healthcare facilities. Earthq Eng Struct Dyn 40:1197–1217. https://doi.org/10.1002/eqe.1084

Cimellaro GP, Tinebra A, Renschler C, Fragiadakis M (2016) New resilience index for urban water distribution networks. J Struct Eng 142:C4015014. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ST.1943-541X.0001433

Davies TRH, Davies AJ (2018) Increasing communities’ resilience to disasters; an impact-based approach. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 31:742–749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.07.026

Dayton-Johnson J (2006) Natural disaster and vulnerability. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/202670544086

Eisensee T, Stromberg D (2007) News droughts, news floods, and US disaster relief. Q J Econ 122:693–728

Firdhous MFM, Karuratane PM (2018) A model for enhancing the role of information and communication technologies for improving the resilience of rural communities to disasters. Procedia Eng 212:707–714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2018.01.091

Fischer S (2021) Post-disaster spillovers: Evidence from Iranian provinces. J Risk Financ Manag 14:193. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14050193

French EL, Birchall SJ, Landman K, Brown RD (2019) Designing public open space to support seismic resilience: a systematic review. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 34:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.11.001

Gaiha R, Hill K, Thapa G (2010) Natural disasters in South Asia. ASARC Working Paper 2010/06, Australia South Asia research centre. The Australian National University, Australia

Gaillard J (2010) Vulnerability, capacity and resilience: perspectives for climate and development policy. J Int Dev 22:218–232. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1675

Global state of democracy (GSD) (2021) World Bank, https://govdata360.worldbank.org/ , Accessed 01 Aug 2021

Graveline N, Grémont M (2017) Measuring and understanding the microeconomic resilience of businesses to lifeline service interruptions due to natural disasters. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 24:526–538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.05.012

Guha-Sapir D, Vos F, Below R, Ponserre S (2012) Annual disaster statistical review 2011: the numbers and trends. Brussels: C.R.E.D. Retrieved from www.cred.be/sites/default/files/ADSR_2011.pdf

Habiba U, Abedin MA, Shaw R (2016) Chapter 6: Food security, climate change adaptation, and disaster risk. In: Uitto JI, Shaw R (eds) Sustainable development and disaster risk reduction. Disaster risk reduction, Springer, Tokyo. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-55078-5_1

Haen HD, Hemrich G (2007) The economics of natural disasters: implications and challenges for food security. Agri Econ 37:31–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-0862.2007.00233.x

Haque CE (2003) Perspectives of natural disaster in East and South Asia, and the Pacific Island states: socioeconomic correlates and need assessment. Nat Hazards 29:465–483. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024765608135

Havko J, Mitašová V, Pavlenko T, Titko M, Kováčová J (2017) Financing the disaster resilient city in the Slovak Republic. Procedia Eng 192:301–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2017.06.052

Holling CS (1973) Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 4:1–23. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.es.04.110173.000245

Husted T, Nickerson D (2021) Private support for public disaster aid. J Risk Financ Manag 14:247. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14060247

Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN) (2021) University of Notre Dame, https://gain.nd.edu/ , Accessed 01 Aug 2021

International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2021) International Monetary Fund, http://data.imf.org/?sk=F8032E80-B36C-43B1-AC26-493C5B1CD33B , Accessed 01 Aug 2021

Kahn ME (2005) The death toll from natural disasters: the role of income, geography and institutions. Rev Econ Stat 87:271–284

Khan MTI, Anwar S, Batool Z (2022) The role of infrastructure, socio-economic development, and food security to mitigate the loss of natural disasters. Environ Sci Pollut Res 29:52412–52437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-19293-w

Kontokosta CE, Malik A (2018) The resilience to emergencies and disasters index: applying big data to benchmark and validate neighborhood resilience capacity. Sustain Cities Soc 36:272–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2017.10.025

Ludin SM, Rohaizat M, Arbon P (2019) The association between social cohesion and community disaster resilience: a cross-sectional study. Health Soc Care Community 27(3):621–631. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12674

McDaniels T, Chang S, Hawkins D, Chew G, Longstaff H (2015) Towards disaster- resilient cities: an approach for setting priorities in infrastructure mitigation efforts. Environ Syst Decis 35:252–263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10669-015-9544-7

Moreno J, Shaw D (2018) Women’s empowerment following disaster: a longitudinal study of social change. Nat Hazards 92:205–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-018-3204-4

Naudé WA, Bezuidenhout H (2014) Migrant remittances provide resilience against disasters in Africa. Atl Econ J 42:79–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11293-014-9403-9

Noy I (2009) The macroeconomic consequences of disasters. J Dev Econ 88:221–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2008.02.005

Noy I, Yonson R (2018) Economic vulnerability and resilience to natural hazards: a survey of concepts and measurements. Sustainability 10:2850. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10082850

Oztig LI, Askin OE (2020) Human mobility and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a negative binomial regression analysis. Public Health 185:364–367.

Padli J, Habibullah MS (2009) Natural disaster and socio-economic factors in selected Asian countries: A panel analysis. Asian Soc Sci 5:65–71. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v5n4p65

Padli J, Habibullah MS, Baharom AH (2010) Economic impact of natural disasters’ fatalities. Int J Soc Econ 37:429–441. https://doi.org/10.1108/03068291011042319

Padli J, Habibullah MS, Baharom AH (2018) The impact of human development on natural disaster fatalities and damage: panel data evidence. Econ Res 31:1557–1573. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2018.1504689

Panwar V, Sen S (2019) Economic impact of natural disasters: An empirical re-examination. Margin J Appl Econ Res 13:109–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973801018800087

Persson TA, Povitkina M (2017) “Gimme Shelter”: The role of democracy and institutional quality in disaster preparedness. Political Res Q. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912917716335

Pingali P, Alinovi L, Sutton J (2005) Food security in complex emergencies: enhancing food system resilience. Disasters 29:S5–S24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0361-3666.2005.00282.x

Qin Y, Shi X, Li X, Yan J (2021) Geographical indication agricultural products, livelihood capital, and resilience to meteorological disasters: evidence from kiwifruit farmers in China. Environ Sci Pollut Res 28:65832–65847. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-15547-1

Qureshi MI, Yusoff RM, Hishan SS, Alam ASAF, Zaman K, Rasli AM (2019) Natural disasters and Malaysian economic growth: policy reforms for disasters management. Environ Sci Pollut Res 26:15496–15509. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-04866-z

Rahman MH (2018) Earthquakes don’t kill, built environment does: Evidence from cross country data. Econ Model 70:458–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2017.08.027

Raschky PA (2008) Institution and the losses from natural disasters. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 8:627–634. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-8-627-2008

Rose A (2004) Defining and measuring economic resilience to disasters. Disaster Prev Manag 13:307–314. https://doi.org/10.1108/09653560410556528

Sarker MNI, Peng Y, Yiran C, Shouse RC (2020) Disaster resilience through big data: Way to environmental sustainability. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 51:101769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101769

Shah AA, Shaw R, Ye J, Abid M, Amir SM, Pervez AKMK, Naz N (2019) Current capacities, preparedness and needs of local institutions in dealing with disaster risk reduction in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 34:165–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.11.014

Shi Y, Sun J (2021) The influence of neighboring jurisdictions matters: examining the impact of natural disasters on local government fiscal accounts. Public Finance Rev 49:435–463. https://doi.org/10.1177/10911421211025740

Songwathana K (2018) The relationship between natural disaster and economic development: a panel data analysis. Procedia Eng 212:1068–1074. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2018.01.138

Story WT, Tura H, Rubin J, Engidawork B, Ahmed A, Jundi F, Iddosa T, Abrha TH (2018) Social capital and disaster preparedness in Oromia, Ethiopia: an evaluation of the “women empowered” approach. Soc Sci Med 257:111907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.08.027

Sun Y, Chau PH, Wong M, Woo J (2017) Place- and age-responsive disaster risk reduction for Hong Kong: collaborative place audit and social vulnerability index for elders. Int J Disaster Risk Sci 8:121–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-017-0128-7

Svirydzenka K (2016) Introducing a new broad-based index of financial development. IMF Working Paper No. WP/16/5. Strategy, policy, and review department, Washington, D.C., the United States

Swathi JM, González MA, Delgado RC (2017) Disaster management and primary health care: implications for medical education. Int J Med Educ 8:414–415. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.5a07.1e1b

Taghizadeh-Hesary F, Sarker T, Yoshino N, Mortha A, Vo XV (2021) Quality infrastructure and natural disaster resiliency: a panel analysis of Asia and the Pacific. Econ Anal Policy 69:394–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2020.12.021

Taghizadeh-Hesary F, Yoshino N, Mortha A, Sarker T (2019) Quality infrastructure and natural disaster resiliency. ADBI Working Paper Series No. 991. Asian development bank institute, Japan. https://www.adb.org/publications/quality-infrastructure-and-natural-disaster-resiliency

Tammar A, Abosuliman SS, Rahaman KR (2020) Social capital and disaster resilience nexus: A study of flash flood recovery in Jeddah city. Sustainability 12:4668. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114668

Tanesab JP (2020) Institutional effectiveness and inclusions: Public perceptions on Indonesia’s disaster management authorities. Int J Disaster Manag 3:1–15. https://doi.org/10.24815/ijdm.v3i2.17621

Tarhan C, Aydin C, Tecim V (2016) How can be disaster resilience built with using sustainable development? Procedia-Soc Behav Sci 216:452–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.12.059

The climate change knowledge portal (TCCKP) (2021) The World Bank Group, https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/download-data , Accessed 15 May 2021

The United Nations office for disaster risk reduction (UNDRR) (2021) Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction 2015–2030. The disaster information management system (DesInventar), https://www.desinventar.net/index.html , Accessed 01 Apr 2021

The United Nations office for disaster risk reduction (UNISDR) (2019) global assessment report on disaster risk reduction 2019. 9–11 Rue de Varembé, CH 1202, Geneva, Switzerland, https://gar.unisdr.org

The World Bank and The United Nations (2010) Natural hazards, unnatural disasters: The economics of effective prevention. The World Bank, Washington DC

Thywissen K (2006) Core terminology of disaster reduction. In Measuring vulnerability to natural hazards: tow ards disaster resilient societies; Birkmann J (Ed.), United Nations University: New York, NY, USA

Toya H, Skidmore M (2007) Economic development and the impact of natural disasters. Econ Lett 94:20–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2006.06.020

Tselios V, Tompkins E (2017) Local government, political decentralisation and resilience to natural hazard-associated disasters. Environ Hazards 16:228–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/17477891.2016.1277967

United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR) (2004) Terminology: Basic Terms of Disaster Risk Reduction. UNISDR, Geneva

Weerasekara S, Wilson C, Lee B, Hoang V-N, Managi S, Rajapaksa D (2021) The impacts of climate induced disasters on the economy: Winners and losers in Sri Lanka. Ecol Econ 185:107043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107043

World development indicators (WDI) (2021) World Bank. http://databank.worldbank.org , Accessed 01 Apr 2021

World governance indicators (WGI) (2021) World Bank, https://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/Home/Reports , Accessed 20 Mar 2021

World inequality database (WID) (2021) World inequality lab . https://wid.world/data/ , Accessed 15 July 2021

Yun SD, Kim A (2021) Economic impact of natural disasters: a myth or mismeasurement? Appl Econ Lett. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2021.1896667

Download references

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters–CRED, Belgium, for access to EM-DAT database.

This research has no funding from any organization.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Economics, Government College University, Faisalabad, 38000, Pakistan

Muhammad Tariq Iqbal Khan, Sofia Anwar, Muhammad Rizwan Yaseen & Abdul Majeed Nadeem

Nord University Business School (HHN), Post Box 1490, 8049, Bodø, Norway

Samuel Asumadu Sarkodie

Department of Economics, Virtual University of Pakistan, Faisalabad, 38000, Pakistan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Muhammad Tariq Iqbal Khan .

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

List of selected countries

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Khan, M.T.I., Anwar, S., Sarkodie, S.A. et al. Natural disasters, resilience-building, and risk: achieving sustainable cities and human settlements. Nat Hazards 118 , 611–640 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-023-06021-x

Download citation

Received : 06 March 2022

Accepted : 14 May 2023

Published : 24 May 2023

Issue Date : August 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-023-06021-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Disaster risk reduction

- Index-making

- Natural disasters

- Negative binomial regression

- Sendai framework 2015–30

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- 26 July 2023

Meet the scientists planning for disasters

- Nikki Forrester 0

Nikki Forrester is a science journalist based in West Virginia.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You have full access to this article via your institution.

In 2021, the La Soufrière Volcano in St. Vincent and the Grenadines erupted explosively. Credit: Steve Wallace/World Bank

Natural hazards, such as earthquakes, hurricanes, floods, landslides, wildfires and droughts are increasing in frequency and intensity, in large part because of climate change ( M. Coronese et al . Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116 , 21450–21455; 2019 ). In 2022, at least one event occurred every day, according to data from EM-DAT, an international disaster database. And a 2021 report from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization stated that the “annual occurrence of disasters is now more than three times that of the 1970s and 1980s” (see go.nature.com/43pmeke ).

But natural-hazard events don’t necessarily have to escalate into widespread disasters. Even though they are more common today than they were in the past, the number of deaths from them has drastically declined. In 1920–29, for example, more than 8.5 million people died globally as a result of natural disasters, compared with just over 503,000 in 2010–19, according to data from EM-DAT. This can be attributed partly to improvements in disaster risk reduction and preparedness measures. Nature talked to five disaster researchers about how they are working to reduce the risks and impacts of natural-hazard events.

EROUSCILLA JOSEPH: Volcanic activity under lockdown

Volcanologist at the Seismic Research Centre at the University of the West Indies in Saint Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago.

Here in the West Indies, we face hurricanes and tropical storms every year, and flooding, landslides and volcanic eruptions are routine. I work for the Seismic Research Centre at the University of the West Indies in Saint Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago, which began monitoring seismic and volcanic activity in the region 70 years ago. We cover an area of 800 kilometres, stretching from the islands of Saint Kitts and Nevis down to Trinidad and Tobago. We monitor 9 territories and 17 volcanoes.

In 2008, I became the first student to officially graduate with a PhD in volcanology from the centre. In March 2020, COVID-19 hit. That December, the La Soufrière volcano on Saint Vincent and the Grenadines erupted, beginning with a slow extrusion, but becoming explosive on 9 April 2021. It was truly a trial by fire to navigate that process during a pandemic, under lockdown and without vaccines.

Nature Spotlight: Disaster preparedness

Seismic data and information from satellite imagery warned us of unusual activity two days after Christmas. Some staff members at the Soufrière Monitoring Unit of the Saint Vincent and the Grenadines’ National Emergency Management Organisation went up to have a look, and they saw that a new dome had emerged from the floor of the crater. We immediately deployed staff to reactivate the local observatory, upgrade the monitoring network, provide real-time updates to the authorities and support education and outreach related to the volcanic activity ( E. P. Joseph et al . Nature Commun . 13 , 4129; 2022 ).

The eruption started off effusively, and we had to put measures in place to deal with the possibility of it transitioning to explosive. Effusive means that magma erupts at the surface of a volcano and forms a lava flow or dome, whereas explosive describes when magma explodes out of a volcano, often sending ash, gas and lava into the air. On the basis of the data we saw, we provided advice to the prime minister of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, the government of Barbados and several other disaster-management agencies on the likelihood of an eruption, so that they could raise alert levels and start coordinating a response.

We helped with communication to stakeholders and the public about what was happening and how to prepare. Because of limited resources and the pandemic, the centre’s outreach team had to hold virtual community meetings and use trucks with megaphones to keep people informed. In April 2021, the activity of the volcano began to change. More than 22,000 people were evacuated over a period of 24 hours, just before the explosive eruption began. We rotated teams of scientists on the island until November 2021.

We’re a small agency operating in an under-resourced part of the world, and we were able to respond to this volcanic eruption quickly and before any lives were lost. It was a major success, and our achievement was recognized globally by the 2022 Volcanic Surveillance and Crisis Management Award presented by the International Association of Volcanology and Chemistry of the Earth’s Interior. Things can fall apart easily if there is no coordination between the teams, government and disaster organizations. But if you work together and rely on each other, you can push forward, even in an emergency situation.

Emmanuel Raju’s involvement in the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami was a career-defining moment. Credit: Courtesy Emmanuel Raju

EMMANUEL RAJU: Stop blaming nature

Global-health researcher at the University of Copenhagen and director of the Copenhagen Center for Disaster Research.

When you grow up in India, you grow up with natural hazards. I’ve seen a number of cyclones and experienced many school closures due to heavy rains in the monsoon season. At the time of the Indian Ocean tsunami in 2004, I was an undergraduate student studying economics, political science and sociology at St. Joseph’s College in Bengaluru. I volunteered to help mobilize support to some of the main areas that were affected. That experience left a big impression on me. When I graduated in 2007, I learnt that the Tata Institute of Social Sciences in Mumbai had launched a disaster management programme, one of the first of its kind in the region.

Most of my work now deals with trying to challenge conventional notions of how we understand disasters. Disasters are often seen as ‘natural’ in some way, but they occur because of vulnerabilities in society. I work a lot in South Asia. When a disaster occurs, some individuals are disproportionately affected, depending on their social status, caste, religion, gender and other social and economic characteristics. We need to stop blaming nature for the damage caused to the lives and livelihoods of individuals: it is human action and inaction that contribute to many forms of disaster risk.

Another major challenge is breaking disciplinary silos of how disasters are studied. Much of my work at the Copenhagen Center for Disaster Research focuses on bringing together people from various disciplines. You cannot solve issues caused by disasters and climate change with just one discipline. You need different voices from around the world and from many disciplines, including law, economics, physics, social science and health services.

RASHMIN GUNASEKERA: Restoring order after chaos

Disaster risk-management specialist at the World Bank in Washington DC and leader of the Global Program for Disaster Risk Analytics at the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery in Washington DC.

Soon after disasters happen, governments are often left in chaotic situations. Officials need to assess the impacts, so they can make decisions about where to send resources and how to quickly get money to the places that need it. The Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery is a partnership set up by the World Bank and funded by 11 countries that helps low- and middle-income countries to manage and reduce risks from natural hazards and climate change.

Lessons learnt from doing research amid a humanitarian crisis

Some of the work I do as part of the programme is to help with rapid assessments of the impact of disasters to give a monetary value to the damages. People go to the field to conduct these assessments, which take about six to eight weeks. Soon after the massive earthquake in Nepal in April 2015, we started using hazard modelling, engineering and census data to estimate the damage remotely. Our assessment methodology has an accuracy of 90% and takes only about two weeks to do.

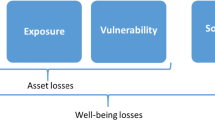

My work with the World Bank, where I started in 2012, involves assessing risk, which is pivotal for disaster risk reduction and preparedness. It’s a complicated subject area that blends principles of science, technology, engineering and economics. Assessing risk consists of three parts. One is the built-up environment, which captures the types of building in a location, how they are spatially distributed and who lives in them. Another is the type, magnitude and frequency of the hazard itself. The third is vulnerability. I combine these three pieces of information to estimate the future potential for damage.

I strive to build effective partnerships and share knowledge across academia and the private and public sectors. We make our methodology for risk assessment available to anyone who wants to use it. In April, I travelled to Fiji to help some of my colleagues to work out what data sets are available and how to put different types of data together to understand how to represent a built-up environment, and more broadly, how to assess the risk of disaster in this location.

Ultimately, progress can happen only when knowledge is taken up by governments, risk-and disaster-management agencies and academia. I’m still an academic at heart, so one of the most satisfying things to see is the impact of the knowledge you generate.

Emily Chan investigates how extreme events affect human populations. Credit: CCOUC (2016)

EMILY CHAN: Linking human health to the climate

Medical researcher at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) and director of the Collaborating Centre for Oxford University and CUHK for Disaster and Medical Humanitarian Response.

As a researcher and practitioner of humanitarian medicine, I try to understand how extreme events might affect human populations. I’ve always been curious about what people do when they experience a disaster such as an earthquake, and why. How do response decision makers and medical workers mobilize resources to help those affected? What do affected people remember, and what do they feel emotional about? Why do researchers choose to document certain information? How do we prevent important knowledge from being carelessly left unrecorded?

A large part of my work involves building models to examine the impact that the climate might have on human health in urban contexts, mostly in Chinese cities. Specifically, I study the impacts of temperature, rainfall, sea-level rise and extreme events on injury, disease, hospitalizations and mortality. For instance, people can have problems with extremely high or low temperatures when they are exposed to them for a prolonged period of time. Rainfall can make freshwater flooding and extreme drought worse, and a rise in sea level can be corrosive and affect the prevalence of infectious diseases such as cholera.

Keep talking to make fieldwork a true team effort

After my colleagues and I began publishing models linking human health to the climate about 10 years ago, we were invited to join a number of committees and talk about our work. Some of our evidence was quoted by the Hong Kong government, and warning policies were changed on the basis of the relationships we found between temperature and mortality ( E. Y. Y. Chan et al. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 66 , 322–327; 2012 ).

Developing policies is another crucial part of what I do. I’m one of the co-chairs of the World Health Organization’s Health Emergency and Disaster Risk Management research group. In 2020, I became a co-chair of the organization’s COVID-19 Social Science working group. When there are major infectious-disease crises globally, researchers and policymakers need to work together to look at the latest evidence and share it with governments so that they can work out what to do in regards to evacuation, lockdowns, isolation, the use of face masks and even ethical research policies.

STERN KITA: An agrarian economy under threat

Disaster and climate-change researcher at the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) in Lilongwe.

In Malawi, the three most common hazards are flooding, drought and strong winds. Because our economy is agrarian, droughts and pest infestations can cause serious cases of food insecurity. We are also affected by tropical cyclones, landslides, earthquakes, fires and outbreaks of cholera and other diseases. I’m often busy.

I worked for the Malawi government for about 11 years and then joined the United Nations in 2020. My work focuses on mitigation and disaster preparedness measures. For instance, I help to develop early-warning systems so that communities are notified of a hazard in advance. I also support projects that protect riverbanks by planting trees to slow the speed of water during a flood, and we’re working to improve drainage systems in urban areas.

In March and April, I travelled a lot to check in on these projects and to support the government in conducting a needs assessment after tropical cyclone Freddy hit the southern part of Malawi. Raising public awareness and building capacity are key parts of my job. I teach disaster risk management at the Malawi University of Science and Technology in Thyolo, and I am helping to build a team that can coordinate and implement disaster risk reduction actions at various levels in the country.

For me, this work is exciting. You can see the results of your efforts and people becoming more resilient to disasters. We have crises almost every day in almost every country. We need to ensure that we provide as much information as we can to build resilience.

Nature 619 , S1-S3 (2023)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-02312-2

These interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

This article is part of Nature Spotlight: Disaster preparedness , an editorially independent supplement. Advertisers have no influence over the content.

Related Articles

Partner content: Connect to protect: working together for a safer green energy transition

Partner content: Wildfire smoke puts heat on hospital admissions

Partner content: How a mega-tsunami impacted marine ecosystems

Partner content: Massive monitoring helps prepare for megaquakes

How I harnessed media engagement to supercharge my research career

Career Column 09 APR 24

How we landed job interviews for professorships straight out of our PhD programmes

Career Column 08 APR 24

Three ways ChatGPT helps me in my academic writing

Long COVID still has no cure — so these patients are turning to research

News Feature 02 APR 24

Google AI could soon use a person’s cough to diagnose disease

News 21 MAR 24

COVID’s toll on the brain: new clues emerge

News 20 MAR 24

Use fines from EU social-media act to fund research on adolescent mental health

Correspondence 09 APR 24

AI-fuelled election campaigns are here — where are the rules?

World View 09 APR 24

Why loneliness is bad for your health

News Feature 03 APR 24

Westlake University ‘Frontiers of Life Sciences’ International Undergraduate Summer Camp 2024

he 2024 summer camp is open to undergraduate students in their junior or senior year who are majoring in life sciences-related fields.

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Westlake University

Call for Global Talents Recruitment Information of Nankai University

Nankai University welcomes global outstanding talents to join for common development.

Tianjin, China

Nankai University

Equipment Service Technician

Memphis, Tennessee

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (St. Jude)

Supv-Environmental Services

Biomedical technician.

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Natural Disasters

Where and from which disasters do people die? What can we do to prevent deaths from natural disasters?

By Hannah Ritchie and Pablo Rosado

This page was first published in December 2022 and last revised in January 2024.

Natural disasters – from earthquakes and floods to storms and droughts – affect millions of people every year. However, we are not defenseless against them, and the global death toll, especially from droughts and floods, has been reduced.

While natural disasters account for a small fraction of all deaths globally , they can have a large impact, especially on vulnerable populations in low-to-middle-income countries with insufficient infrastructure to protect and respond effectively. Understanding the frequency, intensity, and impact of natural disasters is crucial if we want to be better prepared and protect people’s lives and livelihoods.

On this page, you will find our complete collection of data, charts, and research on natural disasters and their human and economic costs.

See all charts on Natural Disasters ↓

Other research and writing on Natural Disasters on Our World in Data:

- Not all deaths are equal: How many deaths make a natural disaster newsworthy?

Natural disasters data explorer

Natural disasters kill tens of thousands each year.

The number of deaths from natural disasters can be highly variable from year to year; some years pass with very few deaths before a large disaster event claims many lives. On average, over the past couple of decades, natural disasters have annually resulted in the deaths of tens of thousands of individuals worldwide.

In the visualizations shown here, we see the annual variability in the number and share of deaths from natural disasters in recent decades.

What we see is that in many years, the number of deaths can be very low – often less than 10,000, and accounting for as low as 0.01% of total deaths. But we also see the devastating impact of shock events: the 1983-85 famine and drought in Ethiopia; the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami ; Cyclone Nargis which struck Myanmar in 2008; and the 2010 Port-au-Prince earthquake which resulted in approximately 70% of all deaths that year in Haiti. All of these events pushed global disaster deaths to over 200,000 – more than 0.4% of deaths in these years.

Low-frequency, high-impact events such as earthquakes and tsunamis are not preventable, but such high losses of human life are. We know from historical data that the world has seen a significant reduction in disaster deaths through earlier prediction, more resilient infrastructure, emergency preparedness, and response systems. Those at low incomes are often the most vulnerable to disaster events: improving living standards, infrastructure, and response systems in these regions will be key to preventing deaths from natural disasters in the coming decades.

Number of deaths from natural disasters

Annual deaths from natural disasters.

In the visualization shown here, we see the long-term global trend in natural disaster deaths. This shows the estimated annual number of deaths from disasters from 1900 onwards from the EM-DAT International Disaster Database . 1

What we see is that in the early-to-mid 20th century, the annual death toll from disasters was high, often reaching over one million per year. In recent decades we have seen a substantial decline in deaths. Even in peak years with high-impact events, the death toll has not exceeded 500,000 since the mid-1960s.

This decline is even more impressive when we consider the rate of population growth over this period. When we correct for population – showing this data in terms of death rates (measured per 100,000 people) – we see an even greater decline over the past century. This chart can be viewed here .

The annual number of deaths from natural disasters is also available by country since 1990. This can be explored in the interactive map.

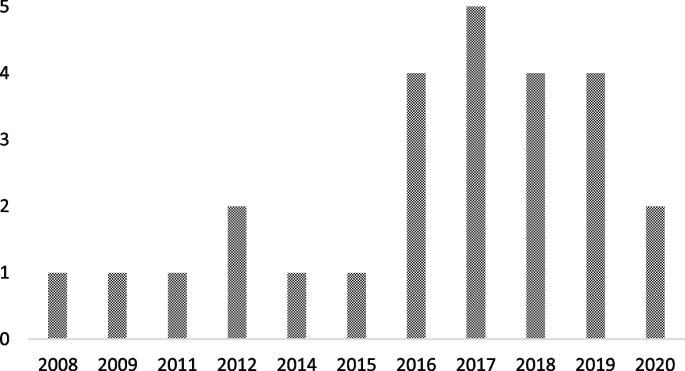

Average number of deaths by decade

In the chart, we show global deaths from natural disasters since 1900, but rather than reporting annual deaths, we show the annual average by decade.

As we see, over the course of the 20th century there was a significant decline in global deaths from natural disasters. In the early 1900s, the annual average was often in the range of 400,000 to 500,000 deaths. In the second half of the century and into the early 2000s, we have seen a significant decline to less than 100,000 – at least five times lower than these peaks. This decline is even more impressive when we consider the rate of population growth over this period. When we correct for population – showing this data in terms of death rates (measured per 100,000 people) – then we see a more than 10-fold decline over the past century. This chart can be viewed here .

Number of deaths by type of natural disaster

With almost minute-by-minute updates on what’s happening in the world, we are constantly reminded of the latest disaster. These stories are, of course, important but they do not give us a sense of how the toll of disasters has changed over time.

For most of us, it is hard to know whether any given year was a particularly deadly one in the context of previous years.

To understand the devastating toll of disasters today, and in the past, we have built a Natural Disasters Data Explorer which provides estimates of fatalities, displacement, and economic damage for every country since 1900. This is based on data sourced from EM-DAT; a project that undertakes the important work of building these incredibly detailed histories of disasters. 2

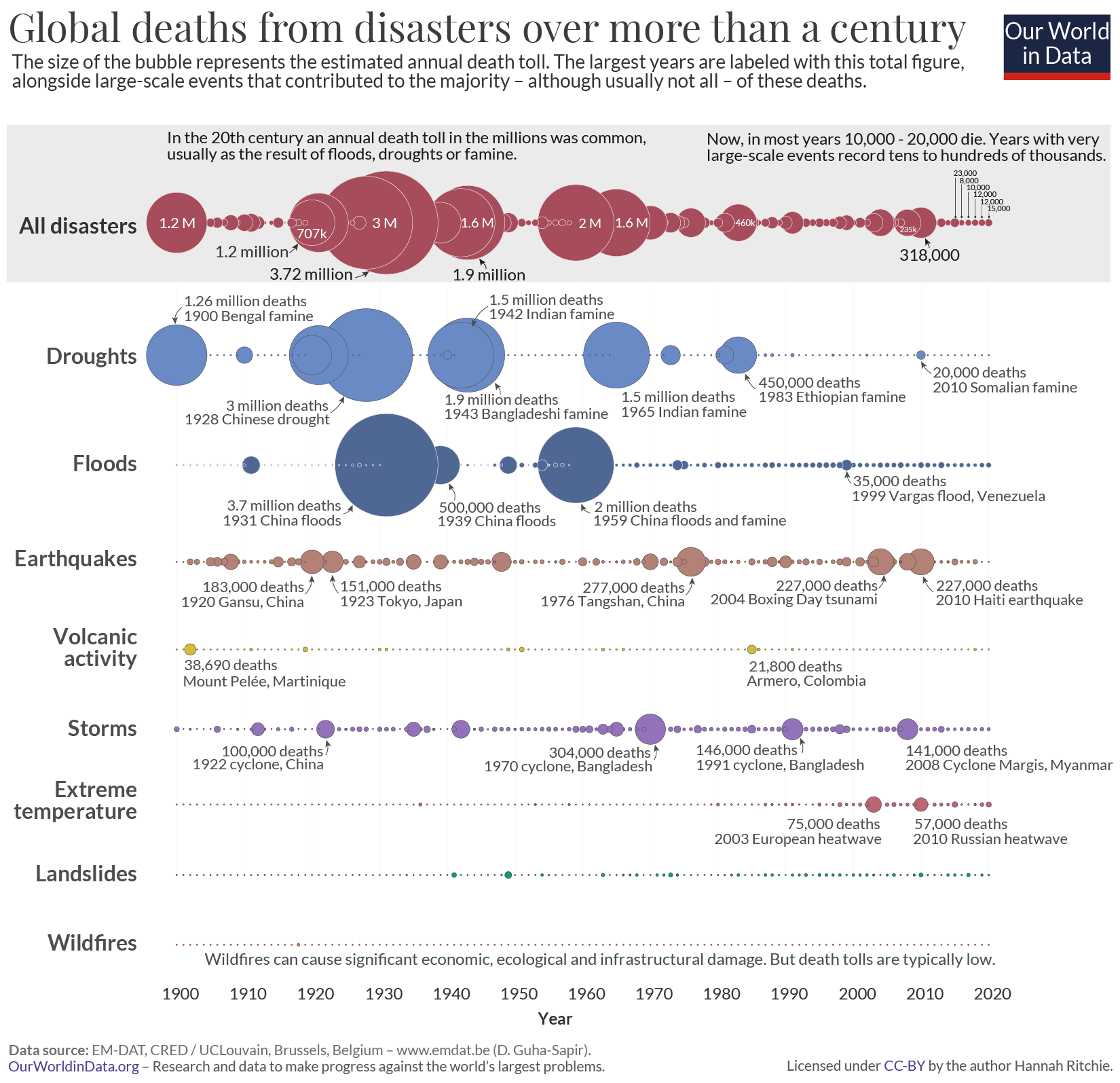

In this visualization, I give a sense of how the global picture has evolved over the last century. It shows the estimated annual death toll – from all disasters at the top, followed by a breakdown by type. The size of the bubble represents the total death toll for that year.

I’ve labeled most of the years with the largest death tolls. This usually provokes the follow-up question: “Why? What event happened?”. So I’ve also noted large-scale events that contributed to the majority – but not necessarily all – of the deaths in that year.

For example, the estimated global death toll from storms in 2008 was approximately 141,000. 138,366 of these deaths occurred in Cyclone Margis, which struck Myanmar and is labeled on the chart.

What we see is that in the 20th century, it was common to have years where the death toll was in the millions. This was usually the result of major droughts or floods. Often these would lead to famines. We look at the long history of famines here .

Improved food security, resilience to other disasters, and better national and international responses mean that the world has not experienced death tolls of this scale in many decades. Famines today are usually driven by civil war and political unrest.

In most years, the death toll from disasters is now in the range of 10,000 to 20,000 people. In the most fatal years – which tend to be those with major earthquakes or cyclones – this can reach tens to hundreds of thousands.

This trend does not mean that disasters have become less frequent, or less intense. It means the world today is much better at preventing deaths from disasters than in the past. This will become increasingly important in our response and adaptation to climate change .

Injuries and displacement from disasters

Human impacts from natural disasters are not fully captured in mortality rates. Injury, homelessness, and displacement can all have a significant impact on populations.

The visualization below shows the number of people displaced internally (i.e. within a given country) from natural disasters. Note that these figures report on the basis of new cases of displaced persons: if someone is forced to flee their home from natural disasters more than once in any given year, they will be recorded only once within these statistics.

Interactive charts on the following global impacts are available using the links below:

- Injuries : The number of people injured is defined as "People suffering from physical injuries, trauma, or an illness requiring immediate medical assistance as a direct result of a disaster."

- Homelessness : The number of people homeless is defined as the "Number of people whose house is destroyed or heavily damaged and therefore need shelter after an event."

- Requiring assistance : The number of people requiring assistance is defined as "People requiring immediate assistance during a period of emergency, i.e. requiring basic survival needs such as food, water, shelter, sanitation, and immediate medical assistance."

- Total number affected : The total number of people affected is defined as "the sum of the injured, affected, and left homeless after a disaster."

Natural disasters by type

Earthquakes, earthquake events.

Earthquake events occur across the world every day. The US Geological Survey (USGS) tracks and reports global earthquakes, with (close to) real-time updates which you can find here .

However, the earthquakes that occur most frequently are often too small to cause significant damage (whether to human life or in economic terms).

In the chart below we show the long history of known earthquakes classified by the National Geophysical Data Center (NGDC) of the NOAA as 'significant' earthquakes. Significant earthquakes are those which are large enough to cause notable damage. They must meet at least one of the following criteria: caused deaths, moderate damage ($1 million or more), a magnitude 7.5 or greater, Modified Mercalli Intensity (MMI) X or greater, or generated a tsunami.

Available data — which you can explore in the chart below — extends back to 2150 BC. But we should be aware that the most recent records will be much more complete than our long-run historical estimates. An increase in the number of recorded earthquakes doesn't necessarily mean this was the true trend over time. By clicking on a country in the map below, you can view its full series of known significant earthquakes.

Deaths from earthquakes

Alongside estimates of the number of earthquake events, the National Geophysical Data Center (NGDC) of the NOAA also publishes estimates of the number of deaths over this long-term series. In the chart below we see the estimated mortality numbers extending back to 1500.

These figures can be found for specific countries using the "change country" function in the bottom-left of the chart, or by selecting the "map" on the bottom right.

At the global level, we see that earthquake deaths have been a persistent human risk through time.

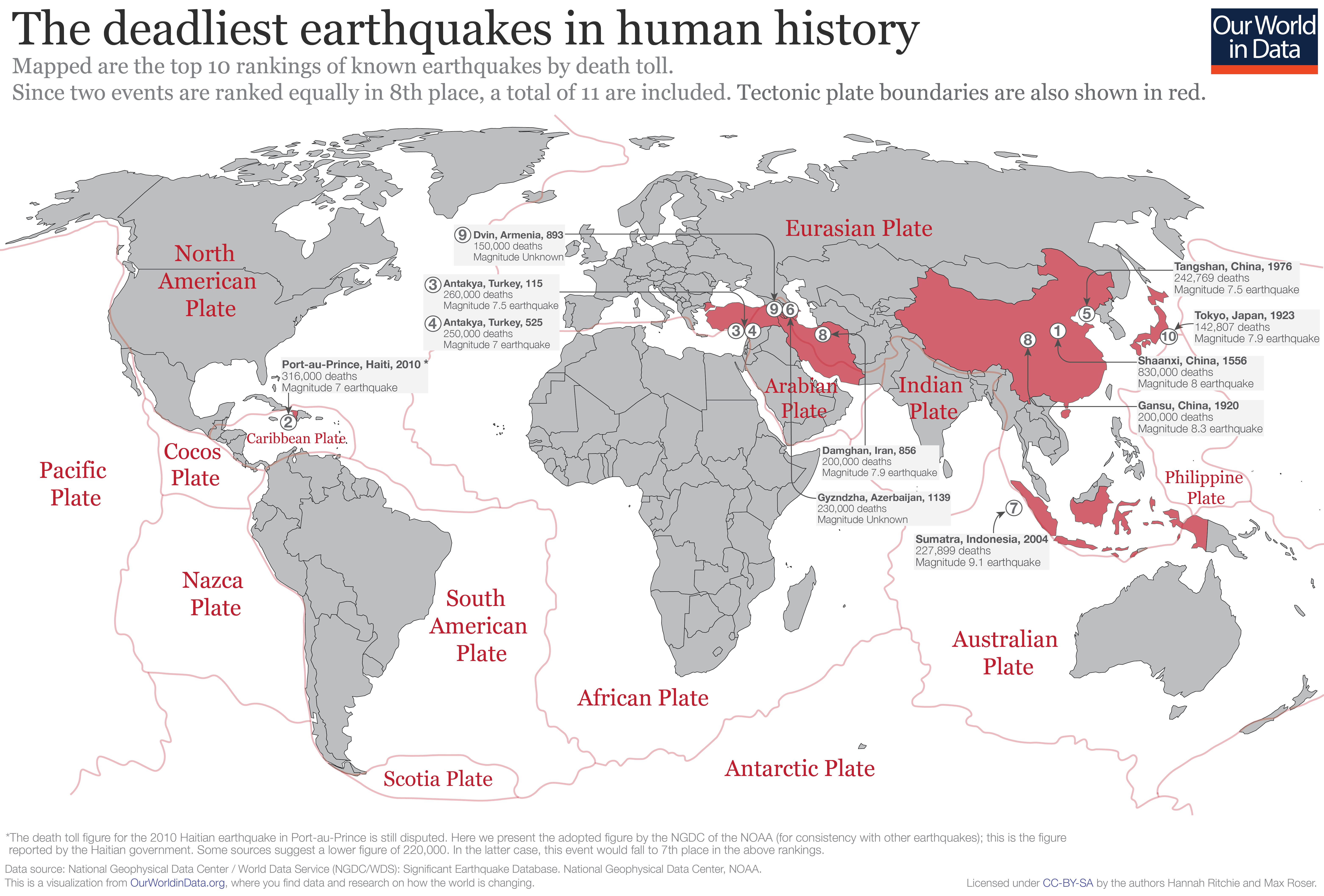

What were the world's deadliest earthquakes?

The number of people dying in natural disasters is lower today than it was in the past, and the world has become more resilient.

Earthquakes, however, can still claim a large number of lives. Whilst historically floods, droughts, and epidemics dominated disaster deaths , a high annual death toll now often results from a major earthquake and possibly a tsunami caused by them. Since 2000, the two peak years in annual death tolls (reaching 100s of thousands) were 2004 and 2010. Both events (the Sumatra earthquake and tsunami of 2004, and the Port-au-Prince earthquake in 2010) are in the deadliest earthquake rankings below.

What have been the most deadly earthquakes in human history? In the visualization, we have mapped the top 10 rankings of known earthquakes which resulted in the largest number of deaths. 3 This ranking is based on mortality estimates from the NOAA's National Geophysical Data Center (NGDC). 4

Clicking on the visualization will open it in higher resolution. This ranking is also summarized in table form.

The most deadly earthquake in history was in Shaanxi, China in 1556. It's estimated to have killed 830,000 people. This is more than twice that of the second most fatal: the recent Port-au-Prince earthquake in Haiti in 2010. It's reported that 316,000 people died as a result. 5

Two very recent earthquakes — the Sumatra earthquake and tsunami of 2004, and the 2010 Port-au-Prince earthquake — feature amongst the most deadly in human history. But equally, some of the most fatal occurred in the very distant past. Making the top three was the earthquake in Antakya (Turkey) in the year 115. Both old and very recent features are near the top of the list. The deadly nature of earthquakes has been a persistent threat throughout our history.

Number of significant volcanic eruptions

There are a large number of volcanoes across the world that are volcanically active but display little or only very low-level activity. In the map, we see the number of significant volcanic eruptions that occur in each country in a given year. A significant eruption is classified as one that meets at least one of the following criteria: caused fatalities, caused moderate damage (approximately $1 million or more), with a Volcanic Explosivity Index of 6 or larger, caused a tsunami, or was associated with a major earthquake. 6

Estimates of volcanic eruptions are available dating back as early as 1750 BCE, however, the data completeness for long historic events will be much lower than in the recent past.

Deaths from volcanic eruptions

In the visualization, we see the number of deaths from significant volcanic eruptions across the world. Using the timeline on the map we can see the frequency of volcanic activity deaths over time. If we look at deaths over the past century we see several high-impact events: the Nevado del Ruiz eruption in Colombia in 1985; the Mount Pelée eruption in Martinique in 1902; and the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa in Indonesia.

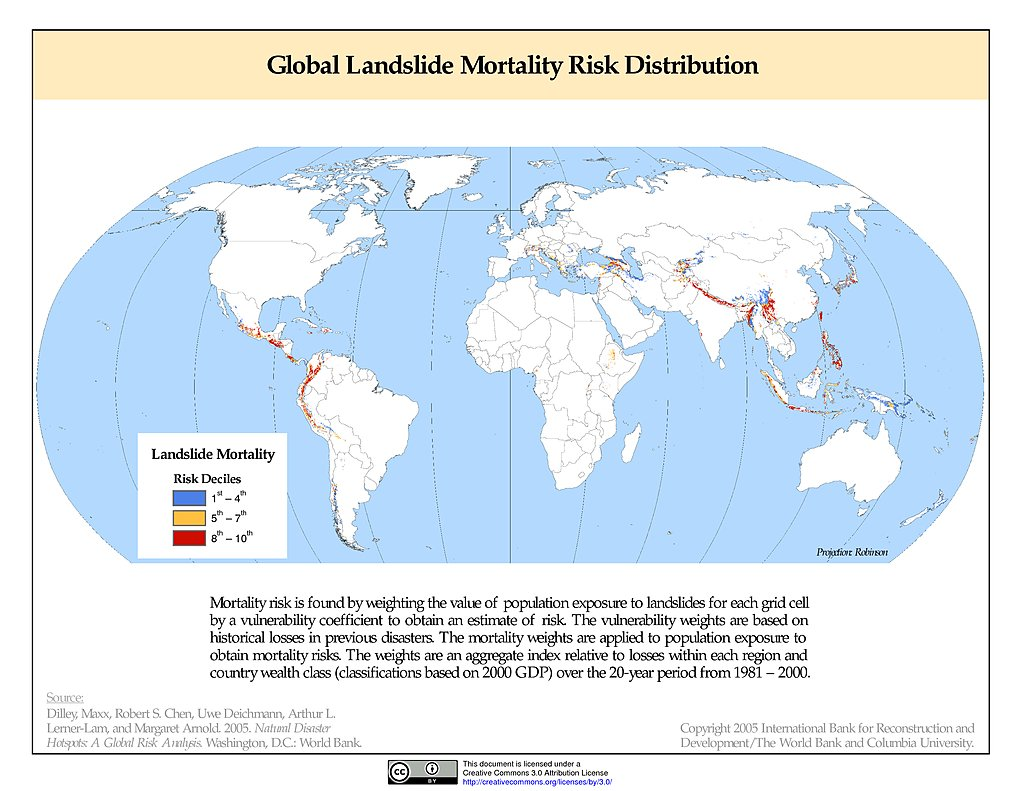

This visualization – sourced from the NASA Socioeconomic Data And Applications Center (SEDAC) – shows the distribution of mortality risk from landslides across the world. As we would expect, the risks of landslides are much greater close to highly mountainous regions with dense neighboring populations. This makes the mortality risk highest across the Andes region in South America, and the Himalayas across Asia.

Famines & Droughts

We cover the history of Famines in detail in our dedicated entry here . For this research, we assembled a global dataset on famines dating back to the 1860s.

In the visualization shown here, we see trends in drought severity in the United States. Given is the annual data of drought severity, plus the 9-year average. This is measured by the Palmer Drought Severity Index: the average moisture conditions observed between 1931 and 1990 at a given location are given an index value of zero. A positive value means conditions are wetter than average, while a negative value is drier than average. A value between -2 and -3 indicates moderate drought, -3 to -4 is severe drought, and -4 or below indicates extreme drought.

Hurricanes, Tornados, and Cyclones

Long-term trends in deaths from us weather events.

Trends in the US provide some of the most complete data on impacts and deaths from weather events over time. This chart shows death rates from lightning and other weather events in the United States over time. Death rates are given as the number of deaths per million individuals. Over this period, we see that on average each has seen a significant decline in death rates. This is primarily the result of improved infrastructure and predicted and response systems to disaster events.

Intensity of North Atlantic Hurricanes

A key metric for assessing hurricane severity is their intensity and the power they carry. The visualizations here use two metrics to define this: the accumulated cyclone energy (ACE), an index that measures the activity of a cyclone season; and the power dissipation index of cyclones.

Extreme precipitation and flooding

Precipitation anomalies.

In the visualization shown, we see the global precipitation anomaly each year; trends in the US-specific anomaly can be found here .

This precipitation anomaly is measured relative to the century average from 1901 to 2000. Positive values indicate a wetter year than normal; negative values indicate a drier year.

Also shown is US-specific data on the share of land area that experiences unusually high precipitation in any given year.

Precipitation extremes

We can look at precipitation anomalies over the course of the year, however, flooding events are often caused by intense rainfall over much shorter periods. Flooding events tend to occur when there is extremely high rainfall for hours or days.

The visualization here shows the extent of extreme one-day precipitation in the US. What we see is a general upward trend in the extent of extreme rainfall in recent decades.

Extreme Temperature (Heat & Cold)

Extreme temperature risks to human health and mortality can result from exposure to extreme heat and cold.

Heatwaves and high temperatures

In the visualizations shown here, we see long-term data on heatwaves and unusually high temperatures in the United States.

Overall we see there is significant year-to-year variability in the extent of heatwave events. What stands out over the past century of data was the 1936 North American heatwave – one of the most extreme heat wave events in modern history, which coincided with the Great Depression and Dust Bowl of the 1930s.

When we look at the trajectory of unusually high summer temperatures over time (defined as 'unusually high' in the context of historical records) we see an upward trend in recent decades.

Cold temperatures

Whilst we often focus on the heatwaves and warm temperatures in relation to weather extremes, extremely low temperatures can often have a high toll on human health and mortality. In the visualization here we show trends in the share of US land area experiencing unusually low winter temperatures. In recent years there appears to have been a declining trend in the extent of the US experiencing particularly cold winters.

US Wildfires

How are the frequency and extent of wildfires in the United States changing over time?

In the charts below we provide three overviews: the number of wildfires, the total acres burned, and the average acres burned per wildfire. This data is shown from 1983 onwards when comparable data recording began.

Over the past 30-35 years we notice three general trends in the charts below (although there is significant year-to-year variability):

- on average, the annual number of wildfires has not changed much;

- on average, the total acres burned has increased from the 1980s and 1990s into the 21st century;

- The combination of these two factors suggests that the average number of acres burned per wildfire has increased.

There has been significant media coverage of the long-run statistics of US wildfires reported by the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC). The original statistics are available back to the year 1926. When we look at this long-term series it suggests there has been a significant decline in acres burned over the past century. However, the NIFC explicitly states:

Prior to 1983, sources of these figures were not known, or could not be confirmed, and were not derived from the current situation reporting process. As a result, the figures prior to 1983 should not be compared to later data.

Representatives from the NIFC have again confirmed (see the Carbon Brief's coverage here ) that these historic statistics are not comparable to those since 1983. The lack of reliable methods of measurement and reporting means some historical statistics may in fact be double or triple-counted in national statistics.

This means we cannot compare the recent data below with old, historic records. But it also doesn't confirm that acres burned today are higher than in the first half of the 20th century. Historically, fires were an often-used method of clearing land for agriculture, for example. It's not implausible to expect that wildfires of the past may have been larger than today but the available data is not reliable enough to confirm this.

Long-term trends in US lightning strikes

This chart shows the declining death rate due to lightning strikes in the US. In the first decade of the 20th century, the average annual rate of deaths was 4.5 per million people in the US. In the first 15 years of the 21st century, the death rate had declined to an average of 0.12 deaths per million. This is a 37-fold reduction in the likelihood of being killed by lightning in the US.

Lightning strikes across the world

The map here shows the distribution of lightning strikes across the world. This is given as the lightning strike density – the average number of strikes per square kilometer each year. In particular, we see the high frequency of strikes across the Equatorial regions, especially across central Africa.

![research questions for natural disasters World Map of Frequency of lightning strikes – Wikipedia [NASA data]0](https://ourworldindata.org/images/published/ourworldindata_world-map-of-frequency-of-lightning-strikes-%E2%80%93-wikipedia-nasa-data0.png)

Economic costs

Global disaster costs.

Natural disasters not only have devastating impacts in terms of the loss of human life but can also cause severe destruction with economic costs. When we look at global economic costs over time in absolute terms we tend to see rising costs. But, importantly, the world – and most countries – have also gotten richer . Global gross domestic product has increased more than four-fold since 1970. We might therefore expect that for any given disaster, the absolute economic costs could be higher than in the past.

A more appropriate metric to compare economic costs over time is to look at them in relation to GDP. This is the indicator adopted by all countries as part of the UN Sustainable Development Goals to monitor progress on resilience to disaster costs.

In the chart, we see global direct disaster losses given as a share of GDP.

Disaster costs by country

Since economic losses from disasters in relation to GDP is the indicator adopted by all countries within the UN Sustainable Development Goals, this data is also now reported for each country.

The map shows direct disaster costs for each country as a share of its GDP. Here we see large variations by country. This data can be found in absolute terms here .

Link between poverty and deaths from natural disasters

One of the major successes over the past century has been the dramatic decline in global deaths from natural disasters – this is despite the fact that the human population has increased rapidly over this period.

Behind this improvement has been the improvement in living standards; access to and development of resilient infrastructure; and effective response systems. These factors have been driven by an increase in incomes across the world.

What remains true today is that populations in low-income countries – those where a large percentage of the population still lives in extreme poverty or score low on the Human Development Index – are more vulnerable to the effects of natural disasters.

We see this effect in the visualization shown. This chart shows the death rates from natural disasters – the number of deaths per 100,000 population – of countries grouped by their socio-demographic index (SDI). SDI is a metric of development, where low SDI denotes countries with low standards of living.

What we see is that the large spikes in death rates occur almost exclusively for countries with a low or low-middle SDI. Highly developed countries are much more resilient to disaster events and therefore have a consistently low death rate from natural disasters.

Note that this does not mean low-income countries have high death tolls from disasters year-to-year: the data here shows that in most years they also have very low death rates. But when low-frequency, high-impact events do occur they are particularly vulnerable to its effects.

Overall development, poverty alleviation, and knowledge-sharing of how to increase resilience to natural disasters will therefore be key to reducing the toll of disasters in the decades to come.

Definitions & Metrics

Hurricanes, cyclones & typhoons.

There are multiple terms used to describe extreme weather events: hurricanes, typhoons, cyclones, and tornadoes. What is the difference between these terms, and how are they defined?

The terms hurricane , cyclone, and typhoon all refer to the same thing; they can be used interchangeably. Hurricanes and typhoons are both described as the weather phenomenon 'tropical cyclone'. A tropical cyclone is a weather event that originates over tropical or subtropical waters and results in a rotating, organized system of clouds and thunderstorms. Its circulation patterns should be closed and low-level.

The choice of terminology is location-specific and depends on where the storm originates. The term hurricane is used to describe a tropical cyclone that originates in the North Atlantic, central North Pacific, and eastern North Pacific. When it originates in the Northwest Pacific, we call it a typhoon . In the South Pacific and Indian Ocean the general term tropical cyclone is used.

In other words, the only difference between a hurricane and a typhoon is where it occurs.

When does a storm become a hurricane?

The characteristics of a hurricane are described in detail on the NASA website .

A hurricane evolves from a tropical disturbance or storm based on a threshold of wind speed.

A tropical disturbance arises over warm ocean waters. It can grow into a tropical depression which is an area of rotating thunderstorms with winds up to 62 kilometers (38 miles) per hour. From there, a depression evolves into a tropical storm if its wind speed reaches 63 km/hr (39 mph).

Finally, a hurricane is formed when a tropical storm reaches a wind speed of 119 km/hr (74 mph).

Difference between hurricanes and tornadoes

But, hurricanes/typhoons/cyclones are distinctly different from tornadoes.

Whilst hurricanes and tornadoes have a characteristic circulatory wind pattern, they are very different weather systems. The main difference between the systems is scale (tornadoes are small-scale circulatory systems; hurricanes are large-scale). These differences are highlighted in the table below:

Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI)

The intensity or size of volcanic eruptions is most commonly defined by a metric termed the 'volcanic explosivity index (VEI)'. The VEI is derived based on the erupted mass or deposit of an eruption. The scale for VEI was outlined by Newhall & Self (1982) but is now commonly adopted in geophysical reporting. 7

The table below provides a summary (from the NOAA's National Geophysical Data Center ) of the characteristics of eruptions of different VEI values. A 'Significant Volcanic Eruption' is often defined as an eruption with a VEI value of 6 or greater. Historic eruptions that were definitely explosive, but carry no other descriptive information are assigned a default VEI of 2.

Interactive charts on natural disasters

Data quality, number of reported disaster events.

A key issue of data quality is the consistency of even reporting over time. For long-term trends in natural disaster events, we know that reporting and recording of events today is much more advanced and complete than in the past. This can lead to significant underreporting or uncertainty of events in the distant past. In the chart here we show data on the number of reported natural disasters over time.

This change over time can be influenced by several factors, namely the increased coverage of reporting over time. The increase over time is therefore not directly reflective of the actual trend in disaster events.

Number of reported disasters by type

This same data is shown here as the number of reported disaster events by type. Again, the incompleteness of historical data can lead to significant underreporting in the past. The increase over time is therefore not directly reflective of the actual trend in disaster events.

EMDAT (2019): OFDA/CRED International Disaster Database, Université Catholique de Louvain – Brussels – Belgium

EM-DAT, CRED / UCLouvain, Brussels, Belgium – www.emdat.be (D. Guha-Sapir)

Since two events are ranked equally in 8th place, a total of 11 are included.

National Geophysical Data Center / World Data Service (NGDC/WDS): Significant Earthquake Database. National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA. Available at: https://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/hazel/view/hazards/earthquake/search .

The death toll of the Haitian earthquake is still disputed. Here we present the adopted figure by the NGDC of the NOAA (for consistency with other earthquakes); this is the figure reported by the Haitian government. Some sources suggest a lower figure of 220,000. In the latter case, this event would fall to 7th place in the above rankings.

This data is sourced from the Significant Volcanic Eruption Database is a global listing of over 500 significant eruptions.

Newhall, C.G. and Self, S (1982). The volcanic explosivity index (VEI): an estimate of explosive magnitude for historical volcanism. Jour Geophys Res (Oceans & Atmospheres) , 87:1231-1238. Available at: https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/JC087iC02p01231 .

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this topic page, please also cite the underlying data sources. This topic page can be cited as:

BibTeX citation

Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license . You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.

Our World in Data is free and accessible for everyone.

Help us do this work by making a donation.

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS. A lock ( Lock Locked padlock ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Disaster Risk and Resilience

For decades, the U.S. National Science Foundation has invested in fundamental research to understand and predict natural hazards and promote resilience.

Each year, extreme events — such as storms, wildfires, floods, heat waves, earthquakes and landslides — claim lives, devastate communities and strain social systems ranging from healthcare to food supplies.

While threats from natural disasters and other hazards cannot be eliminated, research can reduce vulnerabilities and increase community resilience.

On this page

Brought to you by nsf, weather forecasting.

NSF–funded research has helped improve the capabilities of the national radar network, which produces weather forecasting and provides advanced warning of impending storms.

Earthquake monitoring

NSF is a part of the Global Seismographic Network, state-of-the-art sensors that extend across the globe and even to the oceans' depths — serving as an early-warning system for earthquakes and tsunamis.

Building standards for fires

Research funded by NSF and the National Institute of Standards and Technology led to the development of new drapery and construction standards that help save lives during fires.

Forecasting volcanic eruptions

NSF funded the development of Earth- and space-based technologies that help forecast and detect volcanic eruptions.

What we support

Fundamental research

We support research that yields insights into natural hazards — such as hurricanes, floods, wildfires, earthquakes, coastal erosion, severe thunderstorms and tornadoes, volcanoes, emerging epidemics, and disruption of the power grid by space weather — and methods to reduce their harmful impacts.

Research infrastructure

We support the development of state-of-the-art facilities and testbeds across the U.S. to expand knowledge of natural hazards and test new technologies for resilience.

Education and workforce development

We support the creation of a diverse workforce ready to design, implement and manage innovative solutions to natural disasters, hazards and climate change.

Partnerships to accelerate progress

We partner with other federal agencies, industry and nonprofits to share data, tools, expertise and other resources; strengthen workforce development; and translate research into products and services that benefit society.

Featured funding

America's Seed Fund (SBIR/STTR)

Supports startups and small businesses to translate research into products and services — including environmental technologies — for the public good.

Biodiversity on a Changing Planet

Supports design and implementation projects studying functional biodiversity in the context of unprecedented environmental change.

Centers for Research and Innovation in Science, the Environment and Society

Invites planning proposals for interdisciplinary research to create evidence-based solutions that strengthen human resilience, security, and quality of life by addressing seemingly intractable challenges that confront society.

Civic Innovation Challenge

Supports planning and implementation of community-university partnerships for significant near-term impacts in one of two focus areas: building climate-resilient communities and bridging the gap between essential resources and services and community needs.

Combustion and Fire Systems

Supports research on combustion and fire prediction and mitigation. Priority areas include basic combustion science, combustion science related to clean energy, wildland fire prediction and prevention, and turbulence-chemistry interactions.

Confronting Hazards, Impacts and Risks for a Resilient Planet

Invites projects focusing on innovative and transformative research to advance Earth system hazard knowledge and risk mitigation in partnership with affected communities.

Engineering for Civil Infrastructure

Supports fundamental research in infrastructure materials and architectural, geotechnical and structural engineering. Focus areas include geomaterials and geostructures, structural materials, structural and non-structural systems, and building envelopes.

Humans, Disasters and the Built Environment

Supports fundamental research on the interactions between humans and the built environment within and among communities exposed to natural disasters, pandemics and other hazards.

Modeling of Catastrophic Impacts and Risk Assessment Due to Climate Change

Supports the creation of an industry-university research partnership focused on modeling catastrophic impacts and risk assessment of climate change, targeting the needs of the financial and insurance sectors of the economy.

Responsible Design, Development, and Deployment of Technologies

Supports research, implementation and education projects involving multi-sector teams that focus on the responsible design, development or deployment of technologies.

Smart and Connected Communities

Supports use-inspired research that addresses communities' social, economic and environmental challenges. Projects must work with community stakeholders on pilots that integrate intelligent technologies with the natural and built environments.

Strengthening American Infrastructure

Supports research that incorporates scientific insights about human behavior and social dynamics to better design, develop, rehabilitate and maintain strong and effective American infrastructure.

NSF directorates supporting disaster-related research

Engineering (eng), geosciences (geo), biological sciences (bio), social, behavioral and economic sciences (sbe), computer and information science and engineering (cise), mathematical and physical sciences (mps), stem education (edu), integrative activities (oia), international science and engineering (oise), technology, innovation and partnerships (tip), featured news.

Wildfires transform aquatic ecosystems, with implications for wildlife and water quality

New model adds human reactions to flood risk assessment

Scientists isolate early-warning tremor pattern in lab-made earthquakes

Additional resources.

- National Earthquake Hazards Reduction Program Strategic Plan Outlines a coordinated federal program of earthquake monitoring, research, implementation and outreach in collaboration with other organizations.

- National Ecological Observatory Network A continental-scale ecological observatory with sensor networks, instrumentation, observational sampling, natural history archives and remote sensing.

- National Center for Atmospheric Research Supports research in atmospheric and geospace science, environmental sciences and geosciences.

- National Windstorm Impact Reduction Program Strategic Plan Outlines a coordinated federal program of windstorm research, development, implementation and outreach in collaboration with other organizations.

- Natural Hazards Engineering Research Infrastructure Supports state-of-the-art research facilities, like the world's largest outdoor experimental earthquake facility, to study natural hazards.

- NSF CONVERGE Natural Hazards Center Advances the ethical conduct and scientific rigor of hazards and disaster research and strengthens networks between research communities.

- U.S. Global Change Research Program A coordinated federal approach to research on the forces shaping the global environment and their impacts on society.

- WIFIRE Uses Big Data from cameras, weather stations, topography and other sources to quickly predict where wildfires will spread.

- Wildfire Interdisciplinary Research Center Conducts wildfire research with the goal of improving tools and strategies used by communities and first responders to address wildfires.

- "CHIPS and Science Act of 2022" The act authorizes historic investments in use-inspired, solutions-oriented research and innovation in key technology focus areas.

- Frontiers in Public Health

- Public Mental Health

- Research Topics

Natural Disasters and Mental Health Consequences

Total Downloads

Total Views and Downloads

About this Research Topic

Natural Disasters are large-scale events that are often unexpected and cause death, trauma, and destruction of property. Disasters affect millions of people around the globe every year. Many studies reported there were increased short term and long-term mental health consequences, such as depression, post ...

Keywords : Natural Disasters, Mental Health, Depression, PTSD

Important Note : All contributions to this Research Topic must be within the scope of the section and journal to which they are submitted, as defined in their mission statements. Frontiers reserves the right to guide an out-of-scope manuscript to a more suitable section or journal at any stage of peer review.

Topic Editors

Topic coordinators, recent articles, submission deadlines.

Submission closed.

Participating Journals

Total views.

- Demographics

No records found

total views article views downloads topic views

Top countries

Top referring sites, about frontiers research topics.