The Psychology of Esports: A Systematic Literature Review

Affiliations.

- 1 Institute of Psychology, ELTE Eötvös Loránd University, Izabella utca 46, Budapest, 1064, Hungary.

- 2 Doctoral School of Psychology, ELTE Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary.

- 3 International Gaming Research Unit, Psychology Department, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK.

- 4 Institute of Psychology, ELTE Eötvös Loránd University, Izabella utca 46, Budapest, 1064, Hungary. [email protected].

- PMID: 29508260

- DOI: 10.1007/s10899-018-9763-1

Recently, the skill involved in playing and mastering video games has led to the professionalization of the activity in the form of 'esports' (electronic sports). The aim of the present paper was to review the main topics of psychological interest about esports and then to examine the similarities of esports to professional and problem gambling. As a result of a systematic literature search, eight studies were identified that had investigated three topics: (1) the process of becoming an esport player, (2) the characteristics of esport players such as mental skills and motivations, and (3) the motivations of esport spectators. These findings draw attention to the new research field of professional video game playing and provides some preliminary insight into the psychology of esports players. The paper also examines the similarities between esport players and professional gamblers (and more specifically poker players). It is suggested that future research should focus on esport players' psychological vulnerability because some studies have begun to investigate the difference between problematic and professional gambling and this might provide insights into whether the playing of esports could also be potentially problematic for some players.

Keywords: Competitive video gaming; Esport; Gambling; Gaming motivations; Poker; Professional video gaming; Video games.

Publication types

- Systematic Review

- Behavior, Addictive / psychology*

- Competitive Behavior

- Gambling / psychology*

- Internal-External Control*

- Video Games / psychology*

Grants and funding

- K111938/Hungarian National Research, Development and Innovation Office

- KKP126835/Hungarian National Research, Development and Innovation Office

- CA16207/Horizon 2020 Framework Programme of the European Union, COST Action

Keynote webinar | Spotlight on sleep in brain health

LIVE: Thursday 2nd May 2024, 18:00-19:30 (CEST)

Quality sleep is essential for health. But what happens to our brains when sleep patterns are disturbed? Join our experts to explore the interplay between sleep disruption and neurological diseases, and the questions that you need to be asking your patients to help you prevent the harmful effects of sleep deprivation.

Springer Medicine

01-06-2019 | Review Paper

The Psychology of Esports: A Systematic Literature Review

Authors: Fanni Bányai, Mark D. Griffiths, Orsolya Király, Zsolt Demetrovics

Published in: Journal of Gambling Studies | Issue 2/2019

Please log in to get access to this content

Other articles of this issue 2/2019.

Original Paper

Effectiveness of At-Risk Gamblers’ Temporary Self-Exclusion from Internet Gambling Sites

Review Paper

A Systematic Review of Land-Based Self-Exclusion Programs: Demographics, Gambling Behavior, Gambling Problems, Mental Symptoms, and Mental Health

Can a brief telephone intervention for problem gambling help to reduce co-existing depression a three-year prospective study in new zealand, where’s the bonus in bonus bets assessing sports bettors’ comprehension of their true cost, self-reported negative influence of gambling advertising in a swedish population-based sample, cognitive control and criminogenic cognitions in south asian gamblers.

- Medical Journals

- Webcasts & Webinars

- CME & eLearning

- Newsletters

- ESMO Congress 2023

- 2023 ERS Congress

- ESC Congress 2023

- EHA2023 Hybrid Congress

- 2023 ASCO Annual Meeting Coverage

- Advances in Alzheimer’s

- About Springer Medicine

- Diabetology

- Endocrinology

- Gastroenterology

- Geriatrics and Gerontology

- Gynecology and Obstetrics

- Infectious Disease

- Internal Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine

- Rheumatology

- Share on twitter (New window)

- Share on facebook (New window)

- Share on email (New window)

- Share on linkedin (New window)

- Olympic Studies Center

- Other sites

- Olympic World Library Network

- Go to the menu

- Go to the content

- Go to the search

- OSC Catalogue

- INDERSCIENCE

- Search in all sources

![More info on 'The psychology of esports : a systematic literature review / Fanni Bányai... [et al.]' The psychology of esports : a systematic literature review / Fanni Bányai... [et al.] | Bányai, Fanni](https://library.olympics.com/ui/skins/CIOL/portal/front/images/General/DocType/EXTR_MEDIUM.png)

The psychology of esports : a systematic literature review / Fanni Bányai... [et al.]

- Bányai, Fanni

Recently, the skill involved in playing and mastering video games has led to the professionalization of the activity in the form of ‘esports’ (electronic sports). The aim of the present paper was to review the main topics of psychological interest about esports and then to examine the similarities of esports to professional and problem gambling. As a result of a systematic literature search, eight studies were identified that had investigated three topics: (1) the process of becoming an esport player, (2) the characteristics of esport players such as mental skills and motivations, and (3) the motivations of esport spectators. These findings draw attention to the new research field of professional video game playing and provides some preliminary insight into the psychology of esports players. The paper also examines the similarities between esport players and professional gamblers (and more specifically poker players). It is suggested that future research should focus on esport players’ psychological vulnerability because some studies have begun to investigate the difference between problematic and professional gambling and this might provide insights into whether the playing of esports could also be potentially problematic for some players.

- Description

- IN: Journal of gambling studies, 2019, vol. 35, pp. 351-365.

- Comparative studies

- Sports betting

- Export HTML

- Export RIS (Zotero)

Consult online

Other research, selection : zoom esports and gaming - articles.

"Dear IOC" : considerations for the governance, valuation, and evaluation of trends and developments in eSports

Forging a link between competitive gaming, sport and the Olympics : history and new developments

The esports question for the Olympic Movement

Esports will not be at the Olympics

Inclusion of electronic sports in the Olympic Games for the right (or wrong) reasons

Integration of eSports in the structure of Ifs : disruption or continuity ?

![More info on 'Esports research : a literature review / Jason G. Reitman... [et al.]' Esports research : a literature review / Jason G. Reitman... [et al.] | Reitman, Jason G.](https://library.olympics.com/ui/skins/CIOL/portal/front/images/General/DocType/EXTR_LARGE.png)

Esports research : a literature review

Sports video games participation : what can we learn from esports?

Extending disposition theory of sports spectatorship to esports

![More info on 'Setting the scientific stage for esports psychology : a systematic review / Ismael Pedraza-Ramirez... [et al.]' Setting the scientific stage for esports psychology : a systematic review / Ismael Pedraza-Ramirez... [et al.] | Pedraza-Ramirez, Ismael](https://library.olympics.com/ui/skins/CIOL/portal/front/images/General/DocType/EXTR_LARGE.png)

Setting the scientific stage for esports psychology : a systematic review

![More info on 'Managing the health of the eSport athlete : an integrated health management model / Joanne DiFrancisco-Donoghue... [et al.]' Managing the health of the eSport athlete : an integrated health management model / Joanne DiFrancisco-Donoghue... [et al.] | DiFrancisco-Donoghue, Joanne](https://library.olympics.com/ui/skins/CIOL/portal/front/images/General/DocType/EXTR_LARGE.png)

Managing the health of the eSport athlete : an integrated health management model

The challenges of implementing a governing body for regulating esports

![More info on 'The psychology of esports : a systematic literature review / Fanni Bányai... [et al.]' The psychology of esports : a systematic literature review / Fanni Bányai... [et al.] | Bányai, Fanni](https://library.olympics.com/ui/skins/CIOL/portal/front/images/General/DocType/EXTR_LARGE.png)

The psychology of esports : a systematic literature review

Upholding the integrity of esports to successfully and safely legitimize esports wagering

Virtue(al) games - real drugs

E-sports are not sports

E-sports explosion : the birth of esports law or merely a new trend driving change in traditional sports law?

Esports : competitive sports or recreational activity?

![More info on 'Women's experiences in esports : gendered differences in peer and spectator feedback during competitive video game play / Omar Ruvalcaba... [et al.]' Women's experiences in esports : gendered differences in peer and spectator feedback during competitive video game play / Omar Ruvalcaba... [et al.] | Ruvalcaba, Omar](https://library.olympics.com/ui/skins/CIOL/portal/front/images/General/DocType/EXTR_LARGE.png)

Women's experiences in esports : gendered differences in peer and spectator feedback during competitive video game play

Reconsidering esport : economics and executive ownership

What do you think of this resource give us your opinion.

Fields marked with the symbol * are mandatory.

Export in progress

Change your review, memorise the search.

The search will be preserved in your account and can be re-run at any time.

Your alert is registered

You can manage your alerts directly in your account

Subscribe me to events in the same category

Subscribe to events in the category and receive new items by email.

Frame sharing

Copy this code and paste it on your site to display the frame

Or you can share it on social networks

- Share on twitter(New window)

- Share on facebook(New window)

- Share on email(New window)

- Share on print(New window)

- Share on linkedin(New window)

Confirm your action

Are you sure you want to delete all the documents in the current selection?

Choose the library

You wish to reserve a copy.

Register for an event

Registration cancellation.

Warning! Do you really want to cancel your registration?

Add this event to your calendar

Exhibition reservation.

The Psychology of Esports: A Systematic Literature Review

Summary ( 3 min read), introduction.

- Playing video games has become one of the most popular recreational activities, not just among children and adolescents, but also among adults too (Entertainment Software Association 2017).

- In summary, according to these definitions and descriptions, esports are alternate sports, and a special way of using video games and engaging in gameplay (Adamus 2012) .

- The second criterion concerns institutional stability, which means esport requires centralized rules for regulation and stabilization to be recognized as a sport, and not just viewed as a juvenile recreation activity (Jenny et al. 2016) .

- Many researchers have examined the motivations of gamers, and even if the theoretical basis and the examined video game genres are different, some general and common motivational patterns have been found according to various empirical studies carried out.

- Furthermore, there are no systematic reviews of the psychological literature to date.

- The present study aimed to collate and review all the empirical studies concerning esport from a psychological perspective published between 2000 and 2017.

- Given that competitive gaming only started to occur after videogames could be played online and against other people, the year 2000 was chosen as a start date for the search because the playing of videogames competitively did not exist prior to this date.

- The data collection included all studies published between January 2000 to July 2017.

- The following keywords were used in the respective search engines: 'esport video gam*'; 'professional gam*'; 'pro gam*'; 'competitive video gam*'; 'esport competitive video gam*'; 'sport video gam*' and 'professional video gam*'.

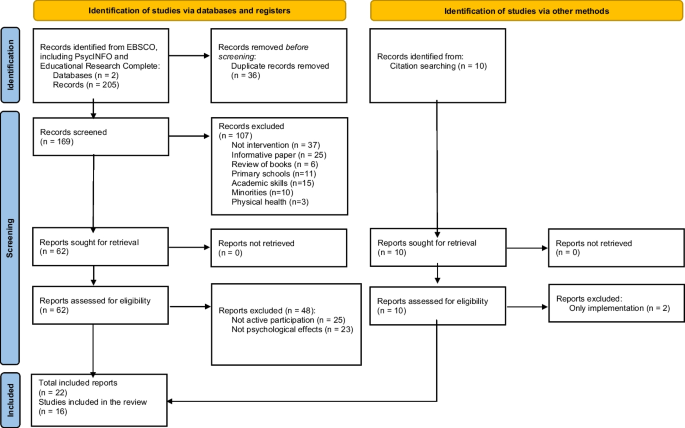

- Based on the inclusion criteria (i.e., an empirical study containing new primary data and published in a peer reviewed journal in the English language), a total of 22 papers were excluded because they were either non-empirical (n=11), were published in conference proceedings or student theses (n=8), or were not specifically focused on esport (n=3).

Becoming an esport player

- In a study by Seo (2016) , the author focused on different perspectives of esport definition, and examined whether esport was fun or work (or neither) by attending esports tournaments in a number of countries and via in-depth interviews with 10 professional eSports players.

- Seo (2016) characterized professional esport playing as a serious leisure activity, following Stebbins' (1982) definition.

- When players gain a more developed competency, they experience the enjoyment of the gaming itself again (achieving stage).

- They 'lose' the glory and satisfaction they experienced earlier (and enter the slumping stage) before having to recover (recovering stage).

- The authors drew attention to the motivational patterns that change during the development of an esport player, highlighting the fact that esport players use these particular video games differently from a casual gamer.

The characteristics of esport players

- A recent study by (Himmelstein et al. 2017 ) interviewing five esport players identified the mental skills and techniques used by esport players in achieving optimal performance in a highly competitive gaming environment.

- The stronger motivations of spending time on esport playing were competition, peer pressure, and skill building for actual playing of sport.

- Compared to traditional sport behavior involvement, the study explored similarities between esport and traditional sport consumption (i.e., game attendance, game participation, sports viewership, sports readership, sports listenership, online usage specific to sports, and purchase of team merchandise).

- The competition, challenge, and escapism motivations were identified as the need gratifications obtained through esport.

Motivations of esport spectators

- As noted above, esport not only includes players, but also includes organizers and sponsors of esport championships, esports commentators, and the viewing esports audience (Adamus 2012; Jenny et al. 2016; Jonasson and Thiborg 2010) .

- Lee, An, and Lee (2014) examined the characteristics of 103 esport spectators, who attended the 2013 League of Legends World Championship Finals.

- Findings demonstrated that esport viewers watched professional gaming because they enjoyed the drama that occurred during esport matches, as well as the recreation, game commentary, and skills displayed by the professional gamers.

- Furthermore, team attachment and game commentary strongly contributed to the satisfaction of esport viewing.

- From a different perspective, Hamari and Sjöblom (2017) surveyed 888 esport viewers and investigated esport consumers' motivations, to better understand how and why they used this type of media to satisfy their needs based on uses and gratifications theory (Katz et al. 1973) .

- The present review aimed to review all empirical studies examining the psychology of esports, and to draw attention to a new field of video game research.

- These studies not only provided data about why professional gamers act in such competitive ways, but also showed that becoming a professional esport player appears to be similar to the process of becoming a professional athlete in any given sport.

- The playing activity becomes a part of working life, and can negatively affect the concept of playing as free activity.

- Borrowing from the perspective of problematic gambling, further esport research could focus on the fact that professional video game players can also be affected by problematic use due to the level of stress they have to face during practices and competitions.

- In addition to the increasing popularity and attraction of esport, and the psychology of video gaming more generally, these phenomena are often framed as problematic, because of the lack of physical activity and its sedentary nature (van Hilvoorde 2016 ; van Hilvoorde and Pot 2016) or the intensive, excessive use (Griffiths 2017) .

- There is a paucity of empirical data and further research is needed before any definitive conclusions can be made concerning the psychology of esports.

- To earn the 'sport-status,' esports need to be accepted as a sport worldwide ( van Hilvoorde and Pot 2016; Witkowski 2012 Witkowski , 2009)) , and is already under consideration in about 40 countries (International e-Sports Federation 2017).

- Examining the phenomenon of esport could reduce the stigma that some professional gamers may face (individuals, teams, and staff, including coaches, managers), and also identify and help overcome any potential difficulties (e.g., the process of becoming a professional player, coping with stress during training and/or matches, problematic video game use).

Did you find this useful? Give us your feedback

Figures ( 1 )

Content maybe subject to copyright Report

513 citations

270 citations

93 citations

75 citations

67 citations

View 5 citation excerpts

Cites background from "The Psychology of Esports: A System..."

... In light of the growing attention among scholars on gamingdisorder, intensive and excessive videogame use among esport gamers raise interesting questions about the nature of addiction [1,16,23,24]. ...

... , money, fame) in becoming esport gamers [1]. ...

... , need of tension, experiencing new, exciting) [1]. ...

... Increasing numbers of gamers now see video game playing as an opportunity to make a financial living that could potentially change players' gaming motivations [1,16]. ...

... Esports as professional (competitive) gaming started to gain prominence in the early 2000s [1]. ...

14,963 citations

View 2 reference excerpts

"The Psychology of Esports: A System..." refers methods in this paper

... …(2017) USA Five esport players Semi-structured interviews with competitive League of Legend players Interview analysis based on the inductive and deductive content analysis (Elo and Kyngäs 2008) To identify the mental skills and possible obstacles of esport players to achieve better performance. ...

... (2017) USA Five esport players Semi-structured interviews with competitive League of Legend players Interview analysis based on the inductive and deductive content analysis (Elo and Kyngäs 2008) To identify the mental skills and possible obstacles of esport players to achieve better performance. ...

13,996 citations

View 1 reference excerpt

"The Psychology of Esports: A System..." refers background in this paper

... Building on the work of Caillois (2001), Brock (2017) argued that esport could lead to the pursuit of extrinsic rewards over intrinsic ones by playing video games (Ryan and Deci 2000; Ryan et al. 2006). ...

2,900 citations

... Similarly to Seo (2016), Kim and Thomas (2015) explored the process how a video game player becomes an esport player utilizing activity theory (Engeström 1993, 1999; Engeström et al. 1999). ...

2,522 citations

2,466 citations

Related Papers (5)

Frequently asked questions (14), q1. what contributions have the authors mentioned in the paper "the psychology of esports: a systematic literature review" .

The aim of the present paper was to review the main topics of psychological interest about esports and then to examine the similarities of esports to professional and problem gambling. These findings draw attention to the new research field of professional video game playing and provides some preliminary insight into the psychology of esports players. The paper also examines the similarities between esport players and professional gamblers ( and more specifically poker players ). It is suggested that future research should focus on esport players ’ psychological vulnerability because some studies have begun to investigate the difference between problematic and professional gambling and this might provide insights into whether the playing of esports could also be potentially problematic for some players.

Q2. What have the authors stated for future works in "The psychology of esports: a systematic literature review" ?

The present review systematically collated all the published peer-reviewed empirical studies concerning the psychology of esport players, to draw attention to the topic to academics and researchers in an emerging field of gaming activity, and to encourage future empirical studies in the field of sport psychology. However, there is a paucity of empirical data and further research is needed before any definitive conclusions can be made concerning the psychology of esports. Regarding future research directions, further comparison and evaluation of sports and esport is needed, developing the similarities and the differences between such activities. Accepting esport as a genuine sport and the emerging popularity of this activity could lead future empirical studies to applying the tools and methodologies of sport psychology in their design.

Q3. What are the main motivations of MMORPG players?

Among the motivations for playing were achievement motivations (advancement, mechanics, competition), social motivations (socializing, relationship, teamwork), and immersion factors (discovery, role-playing, customization, escapism).

Q4. What is the popular genre in esports?

Although the FPS and the RTS genres have retained their popularity, the new MOBA (Multiplayer Online Battle Arena) games have become the most popular genre in esports.

Q5. What are the important elements underlying gaming motivations?

For instance, Vorderer and his colleagues (Vorderer 2000; Vorderer et al. 2003) found that the most essential elements underlying gaming motivations are interactivity and competition.

Q6. What are the common sports consumption elements among esport players?

However in-game participation, radio listenership, and team merchandise purchase were less common among esport players than traditional sport players.

Q7. What is the purpose of the present review?

The present review aimed to review all empirical studies examining the psychology of esports, and to draw attention to a new field of video game research.

Q8. What is the popular recreational activity in video games?

Playing video games has become one of the most popular recreational activities, not just among children and adolescents, but also among adults too (Entertainment Software Association 2017).

Q9. What is the effect of novelty on esport viewing?

novelty (i.e., enjoyment of seeing new players and teams on the sport scene) had a moderate association with esport consumption, but the enjoyment of aggression (i.e., witnessing aggressive/hostile behavior by the players), escapism (i.e., using media to forget/avoid everyday problems), and acquiring the knowledge (i.e., learning about players and teams, collect information, learn new skills) positively influenced the frequency of esport spectating.

Q10. How many papers were excluded from the literature review?

based on the inclusion criteria (i.e., an empirical study containing new primary data and published in a peer reviewed journal in the English language), a total of 22 papers were excluded because they were either non-empirical (n=11), were published in conference proceedings or student theses (n=8), or were not specifically focused on esport (n=3).

Q11. What is the main argument of Brock (2017)?

Building on the work of Caillois (2001), Brock (2017) argued that esport could lead to the pursuit of extrinsic rewards over intrinsic ones by playing video games (Ryan and Deci 2000; Ryan et al. 2006).

Q12. What is the meaning of "Playing video games in the higher stages of this model"?

This means that playing video games in the higher stages of this model are considered as work (extrinsic motivations) rather than leisure (intrinsic motivations).

Q13. What does Caillois cite as the main argument for esport?

According to previous game studies, Caillois (2001) argues that competitive gaming in general has a negative impact on people and society when gaming engaged in as a free activity becomes a work activity.

Q14. What were the main goals of Seo’s study?

Seo’s (2016) research goals were threefold, to explore: (i) the elements of esport consumption that make the activity attractive to a career of a professional esport player, (ii) the reasons why esport players want to pursue such a career opportunity, and (iii) how players progress through the identity transformation to aquire a professional gamer identity.

Trending Questions (1)

The provided paper does not specifically discuss the relationship between esports and problem solving.

Ask Copilot

Related papers

Contributing institutions

Europe PMC requires Javascript to function effectively.

Either your web browser doesn't support Javascript or it is currently turned off. In the latter case, please turn on Javascript support in your web browser and reload this page.

Search life-sciences literature (43,861,927 articles, preprints and more)

- Full text links

- Citations & impact

- Similar Articles

The Psychology of Esports: A Systematic Literature Review.

Author information, affiliations.

- Demetrovics Z 1

- Griffiths MD 2

ORCIDs linked to this article

- Demetrovics Z | 0000-0001-5604-7551

- Bányai F | 0000-0003-4911-2399

Journal of Gambling Studies , 01 Jun 2019 , 35(2): 351-365 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-018-9763-1 PMID: 29508260

Abstract

Full text links .

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-018-9763-1

References

Articles referenced by this article (69)

Adamus, T. (2012). Playing computer games as electronic sport: In search of a theoretical framework for a new research field. In J. Fromme & A. Unger (Eds.), Computer games and new media cultures: A handbook of digital games studies (pp. 477–490). Dordrecht: Springer.

Brock, t. (2017). roger caillois and e-sports: on the problems of treating play as work. games and culture, 12(4), 321–339., caillois, r. (2001). man, play and games. chicago: university of illinois press., campbell, j. (1965). hero with 1000 faces. new york: world., why do you play the development of the motives for online gaming questionnaire (mogq)..

Demetrovics Z , Urban R , Nagygyorgy K , Farkas J , Zilahy D , Mervo B , Reindl A , Agoston C , Kertesz A , Harmath E

Behav Res Methods, (3):814-825 2011

MED: 21487899

The qualitative content analysis process.

Elo S , Kyngas H

J Adv Nurs, (1):107-115 2008

MED: 18352969

Engeström, Y. (1993). Developmental studies of work as a testbench of activity theory: The case of primary care medical practice. In S. Chaiklin & J. Lave (Eds.), Understanding practice: Perspectives on activity and context (pp. 64–103). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Engeström, y. (1999). activity theory and individual and social transformation. in y. engeström, r. miettinen, & r.-l. punamäki (eds.), perspectives on activity theory (pp. 19–38). cambridge: university press., engeström, y., miettinen, r., & punamäki, r.-l. (1999). perspectives on activity theory. cambridge: cambridge university press., entertainment software association. (2017). essential facts about the computer and video game industry. retrieved february 8, 2017, from http://www.theesa.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/ef2017_finaldigital.pdf., citations & impact , impact metrics, citations of article over time, alternative metrics.

Smart citations by scite.ai Smart citations by scite.ai include citation statements extracted from the full text of the citing article. The number of the statements may be higher than the number of citations provided by EuropePMC if one paper cites another multiple times or lower if scite has not yet processed some of the citing articles. Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been supported or disputed. https://scite.ai/reports/10.1007/s10899-018-9763-1

Article citations, esport programs in high school: what's at play.

Lemay A , Dufour M , Goyette M , Berbiche D

Front Psychiatry , 15:1306450, 26 Jan 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38343624 | PMCID: PMC10853400

The Prevalence and Outlook of Doping in Electronic Sports (Esports): An Original Study and Review of the Overlooked Medical Challenges.

Słyk S , Zarzycki M , Grudzień K , Majewski G , Jasny M , Domitrz I

Cureus , 15(11):e48490, 08 Nov 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38074032 | PMCID: PMC10704399

Missed a live match? Determinants of League of Legends Champions Korea highlights viewership.

Ryu Y , Hwang H , Jeong J , Jang W , Lee G , Pyun H

Front Psychol , 14:1213600, 23 Aug 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 37680247 | PMCID: PMC10481709

Understanding Esports-related Betting and Gambling: A Systematic Review of the Literature.

Mangat HS , Griffiths MD , Yu SM , Felvinczi K , Ngetich RK , Demetrovics Z , Czakó A

J Gambl Stud , 22 Sep 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 37740076

What constitutes victims of toxicity - identifying drivers of toxic victimhood in multiplayer online battle arena games.

Kordyaka B , Laato S , Weber S , Niehaves B

Front Psychol , 14:1193172, 16 Jun 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 37397342 | PMCID: PMC10313333

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

Career as a Professional Gamer: Gaming Motives as Predictors of Career Plans to Become a Professional Esport Player.

Bányai F , Zsila Á , Griffiths MD , Demetrovics Z , Király O

Front Psychol , 11:1866, 05 Aug 2020

Cited by: 8 articles | PMID: 32903792 | PMCID: PMC7438909

Safer esports for players, spectators, and bettors: Issues, challenges, and policy recommendations.

Czakó A , Király O , Koncz P , Yu SM , Mangat HS , Glynn JA , Romero P , Griffiths MD , Rumpf HJ , Demetrovics Z

J Behav Addict , 12(1):1-8, 24 Mar 2023

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 36961739 | PMCID: PMC10260215

The mediating effect of motivations between psychiatric distress and gaming disorder among esport gamers and recreational gamers.

Bányai F , Griffiths MD , Demetrovics Z , Király O

Compr Psychiatry , 94:152117, 08 Aug 2019

Cited by: 30 articles | PMID: 31422185

The Gambling Preferences and Behaviors of a Community Sample of Australian Regular Video Game Players.

Forrest CJ , King DL , Delfabbro PH

J Gambl Stud , 32(2):409-420, 01 Jun 2016

Cited by: 9 articles | PMID: 25773869

Will esports result in a higher prevalence of problematic gaming? A review of the global situation.

Chung T , Sum S , Chan M , Lai E , Cheng N

J Behav Addict , 8(3):384-394, 25 Sep 2019

Cited by: 16 articles | PMID: 31553236 | PMCID: PMC7044624

Funding

Funders who supported this work.

Horizon 2020 Framework Programme of the European Union, COST Action (1)

Grant ID: CA16207

1 publication

Hungarian National Research, Development and Innovation Office (2)

Grant ID: K111938

19 publication s

Grant ID: KKP126835

26 publication s

ÚNKP New National Excellence Program of the Ministry of Human Capacities

Europe PMC is part of the ELIXIR infrastructure

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.15(6); 2023 Jun

- PMC10361539

Health Benefits of Esports: A Systematic Review Comparing the Cardiovascular and Mental Health Impacts of Esports

Kofi d seffah.

1 Internal Medicine, California Institute of Behavioral Neurosciences & Psychology, Fairfield, USA

2 Internal Medicine, Piedmont Athens Regional Medical Center, Athens, USA

Korlos Salib

3 General Practice, El Demerdash Hospital, Cairo, EGY

Lana Dardari

Purva dahat.

4 Medicine, St. Martinus University Faculty of Medicine, Willemstad, CUW

Stacy Toriola

5 Pathology, California Institute of Behavioral Neurosciences & Psychology, Fairfield, USA

Travis Satnarine

6 Pediatrics, California Institute of Behavioral Neurosciences & Psychology, Fairfield, USA

Zareen Zohara

Ademiniyi adelekun.

7 Family Medicine, California Institute of Behavioral Neurosciences & Psychology, Fairfield, USA

Areeg Ahmed

8 Internal Medicine, California Institute of Neuroscience, Thousand Oaks, USA

Sai Dheeraj Gutlapalli

9 Internal Medicine, Richmond University Medical Center Affiliated with Mount Sinai Health System and Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, USA

10 Internal Medicine Clinical Research, California Institute of Behavioral Neurosciences & Psychology, Fairfield, USA

Deepkumar Patel

Safeera khan.

Sports all over the world are celebrated and embraced as an indicator of triumph of youth and the human experience. Esports have increasingly come to be associated with an industry likened to traditional sports. Professional gamers who continuously define new standards in the areas of gaming, entertainment, and esports have emerged. This systematic review sought to find out the extent to which these virtual sports affect cardiovascular and mental health, both positively and negatively, and if this is comparable to traditional sports to any degree. Using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses, we reviewed journals and full-text articles that addressed the topic with keywords, such as esports, cardiovascular, mental health, gaming, and virtual reality. Six articles were selected after quality assessment. In summary, rehabilitative medicine currently benefits the most from this entertainment platform, with comparable findings in the positive and negative effects on mental health. Cardiovascular health appears to benefit from esports, with an increase in physical activity with use, but is not at the level of replacing traditional sports. Unlike as seen with traditional sports, addiction to gaming appears to be a steadily emerging issue that mental health practitioners will, in the not-so-distant future, have to lay ground rules for if esports are to be incorporated in everyday affairs.

Introduction and background

Electronic sports (esports) are gamified interactions propelled by electronic modules in which participants interact through a computer intermediary [ 1 ]. These interactions may be collaborative or competitive. When individuals or groups compete against one another, with a defined set of rules, we deem this a game. Games are played, developed, and won with tactics and strategies, which increase cognitive flexibility [ 2 ]. Collaborative sports, such as rowing, hockey, and soccer, on the other hand, provide another unique set of social skills. Typically, concepts, such as fan bases, material rewards, fitness, and training styles, have been associated with traditional sports of all kinds. Today, like many collaborative and competitive endeavors around the world, esports is growing and gaining attention with viewership [ 3 ]. It has, over the years, come to be incorporated into sports festivals around the globe. Between 2018 and 2021, there were over 400 million viewers of esports worldwide, with viewership expected to continuously rise in the coming years. The pandemic is notably an enabler in the rise of this trend. It is predicted that the total earnings of players around the world from esports will exceed US$500 million by the end of 2023 [ 4 ].

Esports are reported to improve reflexes and eye-hand coordination, although data appear mixed [ 5 ]. Memory, attention, and awareness are noted to be enhanced by some of these games [ 6 ]. At the onset of the COVID era, esports provided a sense of community and engagement to players and participants, although this growth was accompanied by increased threat to cybersecurity and intellectual property [ 7 ]. As opposed to traditional sports, esports seem to come with unique drawbacks, with regard to health. Long-term users of video games report eye strain and a higher frequency of refractive errors [ 8 ]. Some games are associated with high stress levels and burnout. Video games may also disrupt sleep patterns [ 9 ].

This article takes note of the above information as it pertains to esports and video games. We note that there is a gap in knowledge with regard to esports and cardiovascular health. While other health modalities can boast of improving cardiovascular indices, it is hard to rule esports in or out in this regard. Do esports cause detriments to the cardiac function in the long run? Are there any benefits or advantages to cardiovascular morbidity or mortality when it comes to esports? Are effects purely user dependent? Moreover, we seek to find out the effects of esports on mental health. Much has been reported that is related to addiction, betting, depression, and anxiety. This paper seeks to find out if these devices are indeed tools that may be channeled to improve mental well-being or if they are a source of impending problems.

Reporting Guideline

This systematic review was written according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines [ 10 ].

Database and Search Strategy

Our search was initiated between February 12, 2023 and February 19, 2023. The following databases were used as a part of our search: PubMed, MedLine, PubMed Medical Subject Heading (MeSH), ResearchGate, ScienceDirect, and Science.gov . Keywords chosen for the search include "eSports," "health," "mental health," "cardiovascular health," "computer games," "video games," "virtual reality," and "exergames." In addition to the above keywords, the following was employed in the search using PubMed MeSH ((((("Health"[Mesh]) AND "Virtual Reality" [Mesh]) AND "Sports"[Mesh]) OR ( "Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy"[Mesh] OR "Exergaming"[Mesh] )) OR ( "Exergaming/injuries"[Mesh] OR "Exergaming/physiology"[Mesh] OR "Exergaming/psychology"[Mesh] )) AND ( "Video Games/adverse effects"[Mesh] OR "Video Games/psychology"[Mesh] ). Searches were conducted with the help of Booleans operators AND, OR, in various search engines of the databases, limiting findings to papers written between 2017 and 2023. Table Table1 1 is a summary of our search strategies.

MeSH: Medical Subject Heading

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We were interested in all individuals, regardless of age, who used a human-computer interface or an electronic game, to achieve both sport and non-sport endpoints. We believe that this also satisfactorily embraces the domain of esports, in being goal-oriented, either collaborative or competitive, with clearly set expectations. All individuals who patronize esports as users of video games or spectators, for any length of time or duration, for any reason, be it professional or recreational, were included in the population study. Studies selected were full texts, regardless of the study style or type. Assessing the extent to which esports can replace traditional sports by way of health benefits was the main outcome of interest. The health outcomes of esports against traditional sports, which generally involves whole-person involvement and more physicality, were investigated. More succinctly, the role of esports on the cardiovascular, mental, and overall health was compared to that of traditional sports. We were not interested in the degree of usage/patronage as much as the experience following usage and the impact on cardiac and mental health. Table Table2 2 further summarizes our criteria.

Screening of Articles

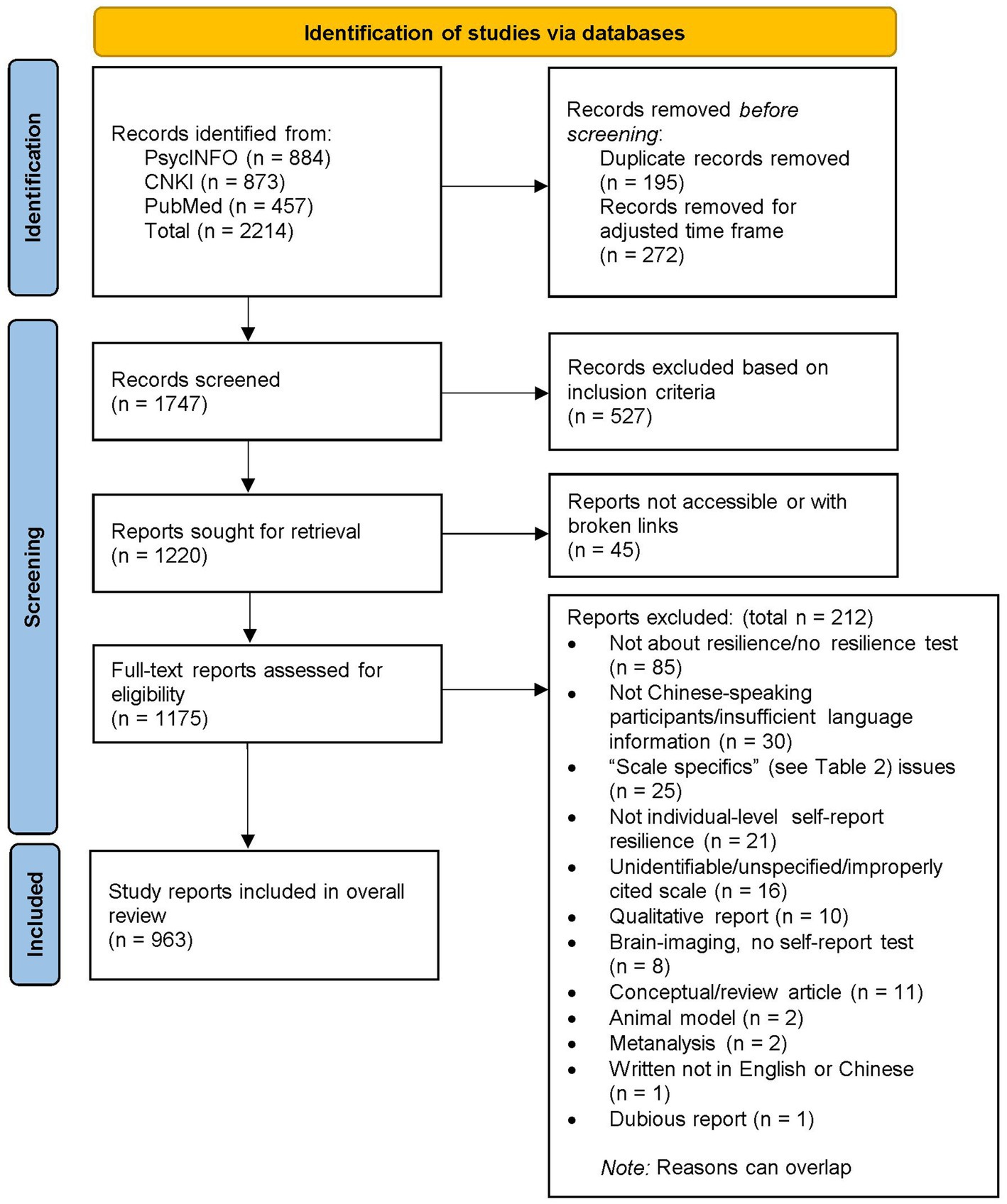

After obtaining articles based on the above criteria, two lead authors further narrowed them down based on the scope of the study. Conclusions, abstracts, titles, and method sections were reviewed at this phase. Duplicates were manually identified and deleted. The resultant selection was then subjected to quality assessment. Figure Figure1 demonstrates 1 demonstrates our screening process.

PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Quality Appraisal

Two independent investigators (the first and second authors) performed article selection, assessment, and analyses in each step. If there was a contradictory result regarding an article’s eligibility, its full text was reassessed by consensus within the group. A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) checklist was used in assessing both systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The Newcastle-Ottawa classification tool was used in assessing cross-sectional studies. The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) checklist was used in assessing case reports. Only studies with a quality appraisal of 60% and above were selected for the final evaluation. Table Table3 3 highlights the quality appraisal tools employed in this study.

AMSTAR: A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews; JBI: Joanna Briggs Institute

As this review was designed to be a mixed-methods study, we found it more pragmatic to work with a purely systematic review, without an additional meta-analysis. Studies in the area are largely observational, with little recourse to blinding, as this was noted by various research groups to be a limiting factor, nearly impossible or even unethical, in administering devices to individuals without at least a partial disclosure. This affected the study designs and outcomes, but this was not unexpected. A total of eight systematic reviews and meta-analyses were sampled in the selection phase. Of these, three were selected following quality assessment [ 11 - 13 ]. Table Table4 4 summarizes the quality appraisal process for the systematic reviews.

AMSTAR: A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews; PICO: population, intervention, control, and outcomes

A total of five cross-sectional studies were brought under review. Following the quality assessment, two articles remained for the review. Table Table5 5 summarizes the appraisal process for the cross-sectional studies.

*Demonstration of degree of approval per guidelines in the Newcastle-Ottawa classification tool

One report was reviewed using the JBI checklist and was accepted [ 16 ]. Table Table6 6 summarizes our findings per the checklist.

Source: Niedermoser et al. [ 16 ]

Table Table7 7 is a summary of articles selected for the final review in this publication. Categories were itemized as areas of interest in this paper, that is, cardiovascular and mental health. Findings were also summarized to reflect the areas of interest, often reflecting conclusions drawn by respective authors.

Esports and Cardiovascular Disease: Benefits

Increasingly, all over the world, esports is gaining popularity and momentum. Going further, some international sports events are introducing virtual tournaments as a part of their content [ 17 ]. A form of these sports, called exergames, aims to increase physical activity and promote cardiometabolic health [ 17 ]. Moreover, the use of wearable electronic devices has been associated with increased motivation for health-seeking behavior and cardiovascular health as a whole [ 18 ]. The awareness provided through electronic media remains vital, as amateur and professional gamers will have to incorporate traditional methods into their daily activities in order to obtain optimal outcomes [ 19 ]. In addition, the platforms that host these games are increasingly being used to promote awareness of healthy habits, including ergonomic tips and campaigns against smoking. Examples of gaming devices associated with improved health include motion sensing controllers, such as mats, boards, and gloves [ 20 ]. In addition, casual video games and even exergames have been identified as stress-reducing activities, overall, when used in the right manner [ 21 ]. Stress reduction is key in preventing adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Our studies show that virtual reality games, an increasingly popular platform for gaming, have the potential to promote physical activity based on the design of the game. Exercise capacity was noted to improve with virtual reality-guided training methods in one study. This was particularly true for those undergoing cardiac rehabilitation. The study went as far as noting improvements in total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein as a benefit of engaging in virtual sports [ 11 ]. The idea of rehabilitation was further buttressed by Sardi et al. [ 12 ], when addressing the role that virtual sports may play in mainstream health. Conclusively, both studies that tackled the domain on cardiovascular health and esports/virtual gaming noted improvement in physical activity as a clear benefit [ 11 , 12 ].

Esports and Cardiovascular Diseases: Harms

We maintain that the effects of gaming are both in-game and after-game. In-game systolic blood pressure and heart rates were considerably higher in gamers during play and could potentially be a trigger for adverse outcomes in patients with borderline or established heart diseases [ 22 ]. In contrast to traditional sports, esports is not associated with the expenditure of energy nor the metabolic benefits derived from the former [ 23 ]. Although, anecdotally, games like chess have been linked with the burning of calories, quoted at up to about 6000 calories a day [ 24 ], it is hard to tell whether the physical demands and long hours of training and decreased calorie intake in preparation for games contribute to these calorie losses or if these losses are purely from the intensity of a single bout. By contrast, sedentary lifestyles and physical inactivity, both associated with chess in particular and esports as a whole, are a leading risk factor for cardiovascular diseases and all-cause mortality [ 25 , 26 ]. Our sampled studies highlighted the role of esports, consoles, and video games in promoting physical activity especially in the area of rehabilitation, including physical and cardiovascular [ 11 - 13 ]. It appears that the intent, design, and execution of these devices and software decide for the most part how far the cardiac gains or harms play out. Highlighting both harms and benefits to the heart, the verdict remains uncertain, as to whether or not to consider esports and virtual games as actual sports [ 27 ]. At this time, it would be premature to consider esports a suitable and complete substitute for traditional sports and exercise. Indeed, it is recommended that professional and amateur gamers incorporate regular physical activity in non-gaming mode/traditional activity in order to enhance their gameplay and promote their overall health [ 25 ].

Esports and Mental Health: Benefits

The virtual platform has been associated with stress relief, skill-building, improved resilience, improved attention and focus, and a reduction in risks of depression, anxiety, and related mental health disorders [ 11 - 13 ]. The role of esports in social connectedness and resilience was highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic, when more engagement was fostered using these platforms worldwide [ 15 ]. However, many of these benefits may be viewed as side benefits while enjoying the game. Its role in rehabilitation, on the other hand, appears to require intentional design [ 12 ]. Moreover, the benefits appear more noticeable in controlled or supervised settings [ 28 ]. We will not discount the role of the Hawthorne effect in this finding. In addition, device use limitation may be associated with better outcomes in terms of the positives outlined above [ 16 , 28 ]. Overall, targeted use of esports for a specific domain of mental health may hold benefits comparable to those of traditional sports [ 29 ]. Other benefits worth highlighting include improved eye-hand coordination, spatial awareness, attention, and focus, depending on the game and in-game competencies [ 30 ]. As things stand, formal training methods are at the inchoate stage for professional gamers [ 30 ].

Esports and Mental Health: Harms

Addiction remains of great concern in the engagement of online sports. Even regular, non-professional gamers are at risk. Non-substance addiction has gained attention in medical circles and is of growing concern [ 16 ]. The elements driving these behaviors may largely be driven by tools incorporated into the software [ 14 ], although addiction in general has heritable features [ 31 ]. There appears to be a relationship between screen time and negative outcomes, such as eye strain, poor posture, sedentary lifestyle, anxiety, and depression [ 29 ]. It goes further. There is a negative correlation between device use and sleep duration, with more screen time yielding poorer sleep quality [ 32 ]. In addition, professional players are exposed to similar amounts of psychological stress as witnessed among traditional sportsmen [ 29 ]. It is interesting to note that the problems created by this new avenue of entertainment are solved by more established, old therapies [ 16 ].

Esports and Other Areas of Health

There is ample evidence to support the notion that esports benefit musculoskeletal health, rehabilitation, and recovery. They may serve as the stopgap in recovery and help stall frailty [ 11 - 13 ]. Cognitive benefits have also been underscored [ 13 ]. A professional esports player must however pay attention to musculoskeletal health, eye health, nutrition, and sleep and has to purposefully maintain social connectedness, lest run the risk of long-term decline with chronic illness [ 16 , 33 ]. Financial health is of great concern to those with addiction, who may have no guidance as to the demands of their ambition and what it takes to achieve the professional status [ 3 , 16 ].

The Future of Esports and Health

For a rapidly emerging international platform, esports may benefit from better regulations, for the sake of player health, cybersecurity, and the protection against marketers [ 4 ]. As more is understood about our behaviors around these sources of entertainment, health warnings and limits may be developed to curb non-substance addiction [ 14 , 16 ]. Beyond therapy and rehabilitation, more entertainment-directed games may be developed, engineered free of craving and addictiveness, as we master and understand the drivers of gambling and addiction that surround these devices [ 14 ].

Limitations

This study is a systematic review of the various components of cardiovascular and mental health importance related to esports. Nonetheless, it has limitations: First, no measurable extents of such findings are provided in this article. For this reason, we are unable to say emphatically to what extent the various findings play a role, what the interplay of these findings yields, and whether there are confounders to these findings. While some findings, such as improvement in physical activity and increased risk of non-substance addiction, have been serially replicated and hence may be deemed credible, other findings, such as effects on depression, share contrasting views that this article is ill equipped to address. Second, our paper did not address other domains of healthcare, besides mental and cardiovascular health. Third, we will not downplay the role of the Hawthorne effect in the few positives recorded in both the cardiovascular and mental health domains. Areas for further studies include the therapeutic role of virtual gaming on pulmonary and neurological health and development.

Conclusions

While producers of esports and gaming tools have the goal of marketing and selling their content, consumers remain exposed to varying degrees of cognitive stimulation, whose effects on other specific domains of health continue to be uncovered. We sought to highlight the role of esports in cardiovascular and mental health. We wanted to find out, objectively, if heart health stood to benefit long term from these devices and their content. We also sought to find out if mental health stood to gain from continued use of gaming devices. Our findings show that there are specific domains of rehabilitation and physical therapy that benefit from such device use. Targeted at recovery, esports serve as excellent tools of engagement in rehabilitative medicine. There appears to be more potential for therapeutics, granted that the right legislature, regulations, and funding are directed at this. Sadly, esports however are not a suitable substitute for traditional sports in the domain of cardiovascular health. Mental health shows comparable benefits from esports as with traditional sports. Professional gamers are exposed to the considerable risk of increased all-cause mortality by engaging in esports. Unfortunately, what constitutes "adequate safety measures" has not been universally agreed upon. Addiction prevention, eye health, hearing health, mental health, and cardiovascular health domains host only arbitrary rules and guidelines from the esports community. In conclusion, these devices are tools, and tools will remain as useful as we decide to make them. Moreover, although these devices and platforms have come to stay, the onus is on proponents and consumers to arm themselves and their dependents from the harms.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge and thank the following individuals and organization for the tremendous support they offered in putting this work together. First, I am grateful to the team supervisor Dr. Safeera Khan, for her patience, guidance, and insightful feedback throughout the process. Her mentorship and expertise have shaped my approach to studies such as this one and have set me on the path of deeper learning. To my colleagues Korlos Salib, Lana Dardari, and Maher Taha, I say a big thank you for sharing your time and experience in this area, helping me overcome barriers that would otherwise have stalled the publication. To Purva Dahat, Stacy Toriola, and Travis Satnarine, I say a big thank you for the collaboration and fruitful discussions that shaped my approach in this paper and my understanding of the overall subject matter. I also would like to thank Zareen Zohara, Ademiniyi Adelekun, and Areeg Ahmed, who contributed to the article by proofreading my work several times and providing additional feedback when it was needed. This endeavor would not have been possible without them. Finally, the organization of countless meetings and beating deadlines may not have been possible without the persistence and patience of Areeg Ahmed, Sai Dheeraj Gutlapalli, and Deepkumar Patel, whom I am deeply grateful. I would also like to thank the NeuroCal Institute for taking the initiative to build this team of researchers, from which this article has been accomplished. I do wish them well in all their endeavors. Humbly, I remain the first author of this publication and will make data readily available upon request through [email protected]. Data are stored as database search findings and quality appraisal tables.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

The Psychology of Esports: A Systematic Literature Review

2018, Journal of gambling studies

Recently, the skill involved in playing and mastering video games has led to the professionalization of the activity in the form of 'esports' (electronic sports). The aim of the present paper was to review the main topics of psychological interest about esports and then to examine the similarities of esports to professional and problem gambling. As a result of a systematic literature search, eight studies were identified that had investigated three topics: (1) the process of becoming an esport player, (2) the characteristics of esport players such as mental skills and motivations, and (3) the motivations of esport spectators. These findings draw attention to the new research field of professional video game playing and provides some preliminary insight into the psychology of esports players. The paper also examines the similarities between esport players and professional gamblers (and more specifically poker players). It is suggested that future research should focus on espo...

Related Papers

Mark D Griffiths

Recently, the skill involved in playing and mastering video games has led to the professionalization of the activity in the form of 'esports' (electronic sports). The aim of the present paper was to review the main topics of psychological interest about esports and then to examine the similarities of esports to professional and problem gambling. As a result of a systematic literature search, eight studies were identified that had investigated three topics: (1) the process of becoming an esport player, (2) the characteristics of esport players such as mental skills and motivations, and (3) the motivations of esport spectators. These findings draw attention to the new research field of professional video game playing and provides some preliminary insight into the psychology of esports players. The paper also examines the similarities between esport players and professional gamblers (and more specifically poker players). It is suggested that future research should focus on esport play-ers' psychological vulnerability because some studies have begun to investigate the difference between problematic and professional gambling and this might provide insights into whether the playing of esports could also be potentially problematic for some players.

Behaviour & Information Technology

Joseph Macey , Henri Pirkkalainen

Contemporary digital technologies have facilitated practices related to games whereby users often produce and consume content for free. To date, research into consumer interactions has largely focused on in-game factors, however, the intention to both play the game and to make in-game purchases are influenced by outside factors, including game streams and game-centred communities. In particular, the growth of competitive gaming, known as esports, offers a new channel for consumer engagement. This research explores the potential for esports to be a significant factor in understanding both intentions to play and spend money on games. Our study draws from Motivations Scale of Sports Consumption to empirically investigate the relationship between esports spectating motivations and game consumption: Watching Intention, Gaming Intention, and Purchasing Intention. This survey uses structural equation modelling (SEM) to analyse data collected from a sample of video game players (n = 194). This research contributes empirical evidence of the relationship between esports spectating and game consumption, with the relationship between Watching Intention and Gaming Intention found to be particularly strong. Finally, while the MSSC is an adequate measure for esports spectating, additional aspects specific to esports require further investigation, consequently, there may be more optimal measures which can be developed. ARTICLE HISTORY

Joseph Macey

An established body of research exists in which playing video games has been associated with potentially problematic behaviours, such as gambling. An issue highlighted by the recent emergence of game-based gambling practices such as loot boxes, social network casinos, free-to-play game mechanics, and gambling using virtual goods and skins. This study investigates relationships between a range of gambling activities and the consumption of video games in general, and the newly emergent phenomenon of esports in particular. In addition, these practices are considered in relation to established measures assessing game addiction and problematic gambling. The study employs Partial Least Squares modelling to investigate data gathered via an international online survey (N = 613). Video game addiction was found to be negatively associated with offline gambling, online gambling, and problem gambling. Video game consumption had only small, positive association with video game-related gambling and problem gambling. Consumption of esports had small to moderate association with video game-related gambling, online gambling, and problem gambling. The primary finding of this study are that contemporary video games are not, in themselves, associated with increased potential for problematic gambling, indeed, the position that problem gaming and problem gambling are fundamentally connected is questioned.

Journal of Emerging Sport Studies

During recent years, while electronic sports (esports) has increasingly become a positive mainstream cultural phenomenon, it also may have several socioeconomic implications, such as the growth of esports betting. Much like betting in sport, betting on esports has become a prominent form of gambling. However, there is still a paucity of knowledge on the demographic characteristics of this gambling cohort, particularly in regard to its relationship to video game play and spectatorship. In the present study, past-year video gamers (N = 1368) completed an online survey. Survey questions inquired about their esports event spectating, video game play, and esports betting behaviours, as well as general demographic questions. Video gamers who bet on esports were a distinct cohort from their counterparts: younger, more likely to be male, lower frequency of video game play, higher frequency of esports spectatorship, and more likely to watch esports in a social setting (e.g., with others). By providing a background on gamers' behaviours this work contributes to the growing body of research into the dynamic profile of esports play, spectatorship, and gambling. Findings are reflective of the growing interrelation of gambling and gaming behaviours, a subject garnering increasing attention from governments, regulatory agencies, public health specialists and clinicians, and the related industries themselves.

New Media and Society

The parallel media related to sports, gaming and gambling are expanding, exemplified by the emergence of esports and game-related gambling (e.g. loot boxes, esports betting). The increasing convergence of these phenomena means it is essential to understand how they interact. Given the expanding consumer base of esports, it is important to know how individuals' backgrounds and consumption of game media may lead to esports betting. This study employs survey data (N = 1368) to investigate how demographics, alongside consumption of video games, esports and gambling can predict esports betting activity. Results reveal that both spectating esports and participation in general forms of gambling are associated with increased esports betting, no direct association was observed between the consumption of video games and esports betting. Findings suggest that while games may act as a vehicle for gambling content, highlighting the convergence of gaming and gambling, there is no intrinsic aspect which directly encourages gambling behaviours.

Giulia Sotero

Purpose-The purpose of this paper is to investigate why do people spectate eSports on the internet. The authors define eSports (electronic sports) as "a form of sports where the primary aspects of the sport are facilitated by electronic systems; the input of players and teams as well as the output of the eSports system are mediated by human-computer interfaces." In more practical terms, eSports refer to competitive video gaming (broadcasted on the internet). Design/methodology/approach-The study employs the motivations scale for sports consumption which is one of the most widely applied measurement instruments for sports consumption in general. The questionnaire was designed and pre-tested before distributing to target respondents (n ¼ 888). The reliability and validity of the instrument both met the commonly accepted guidelines. The model was assessed first by examining its measurement model and then the structural model. Findings-The results indicate that escapism, acquiring knowledge about the games being played, novelty and eSports athlete aggressiveness were found to positively predict eSport spectating frequency. Originality/value-During recent years, eSports (electronic sports) and video game streaming have become rapidly growing forms of new media in the internet driven by the growing provenance of (online) games and online broadcasting technologies. Today, hundreds of millions of people spectate eSports. The present investigation presents a large study on gratification-related determinants of why people spectate eSports on the internet. Moreover, the study proposes a definition for eSports and further discusses how eSports can be seen as a form of sports.

Robin W Streppelhoff

The bibliography is intended to illustrate the state of research on different types of video games (e-sports and serious games) in connection with sport culture. For this purpose, scientific publications from sport-specific databases but also from databse portals of economics and education were put together when they appeared there in connection with "sports" or "e-sports". The data sets stem from the sport information portal SURF, SportDiscus, FIS Education and EconBiz. Due to multiple assignments, the majority of the 369 references included in this collection are "serious games" (192 entries), followed by "E-Sport" (161) and the chapter "Definitions and Influences" (59). In Germany, in 2018 there was a broad public discussion on e-sports and its relation to organized sport. Thus this development is described in more detail in the introduction than the area of serious games. It is intended to provide a brief insight into the scene and the social context with regard to organized sport. For this purpose, the genres of games are outlined and the public debate in the media, politics and organized sports presented.

Internet Research

Joseph Macey , Max Sjöblom

Purpose-Esports (electronic sports) are watched by hundreds of millions of people every year and many esports have overtaken large traditional sports in spectator numbers. The purpose of this paper is to investigate spectating differences between online spectating of esports and live attendance of esports events. This is done in order to further understand attendance behaviour for a cultural phenomenon that is primarily mediated through internet technologies, and to be able to predict behavioural patterns. Design/methodology/approach-This study employs the Motivation Scale for Sports Consumption to investigate the gratifications spectators derive from esports, both from attending tournaments physically and spectating online, in order to explore which factors may explain the esports spectating behaviour. The authors investigate how these gratifications lead into continued spectatorship online and offline, as well as the likelihood of recommending esports to others. The authors employ two data sets, one collected from online spectators (n ¼ 888), the other from live attendees (n ¼ 221). Findings-The results indicate that online spectators rate drama, acquisition of knowledge, appreciation of skill, novelty, aesthetics and enjoyment of aggression higher than live attendees. Correspondingly, social interaction and physical attractiveness were rated higher by live attendees. Vicarious achievement and physical attractiveness positively predicted intention to attend live sports events while vicarious achievement and novelty positively predicted future online consumption of esports. Finally, vicarious achievement and novelty positively predicted recommending esports to others. Originality/value-During the past years, esports has emerged as a new form of culture and entertainment, that is unique in comparison to other forms of entertainment, as it is almost fully reliant on computer-human interaction and the internet. This study offers one of the first attempts to compare online spectating and live attendance, in order to better understand the phenomenon and the consumers involved. As the growth of esports is predicted to continue in the coming years, further understanding of this phenomenon is pivotal for multiple stakeholder groups.

eSports Yearbook 2017/18

Ruth S. Contreras Espinosa , Bruno Duarte Abreu Freitas , Pedro Correia

Carina Assunção

The present study argues against the deterministic view that professional gaming should be constructed as a sport (Taylor, 2012; Voorhees, 2015). The stereotypical male gamer is examined against the user representations created for esports; i.e. athletic masculinity and geek technology user. How does this sit with individuals’ performance of gender, work and sport? Using a framework of game studies and science and technology studies, 10 females and males involved in esports were interviewed. Irrespective of gender, competition was a high motivation to develop skills in professional gaming. Individuals in esports view gaming as fun, first and foremost. They usually refer to their ‘day jobs’ and potential future careers derived from university studies. It was found that in general, those who have a past of practicing organised sports more readily accept the label of athlete. Discussions about the toxic environment in esports were explicit with female gamers but only implicit with male ones. Women in the lower ranks affirmed it is ubiquitous and two strategies to deal with it were mentioned; ignore and mute voice chat to silence toxic players, or confront and retaliate. Men implicitly spoke about hostility between competitors and the need to rapidly obtain skills to surpass them.

RELATED PAPERS

Journal of Applied Sport Management

Seth E Jenny , Margaret C . Keiper , Joey Gawrysiak , R. Douglas Manning, Ph.D. , Patrick M. Tutka

Proceedings of the 2019 Esports Research Conference

Amanda Cullen , Matthew Knutson

Sport Marketing Quarterly

Daniel C Funk , Anthony Pizzo , Bradley Baker , Sangwon Na , Miae Lee

Eduardo Cardoso

International Gambling Studies

Mark R Johnson

Seth E Jenny , R. Douglas Manning, Ph.D. , Tracy W. Olrich , Margaret C . Keiper

Media, Culture and Society

Mark R Johnson , Jamie Woodcock

Stephanie Orme

Veli-Matti Karhulahti , Rune Kristian Lundedal Nielsen

Journal of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics

Jimmy Sanderson

Doç.Dr.Armağan Ebru BOZKURT YÜKSEL

Journal of Medical Internet Research

Róbert Urbán , Csilla Ágoston

Lukasz D Kaczmarek

Nepetoso Lopez

Stanley A. Kaakyire

Transactions of the Digital Games Research Association

Miia Siutila

Proceedings of DiGRA

Tanja Välisalo

Exercise and Quality of Life (1821-3480) 11 (2019), 2; 47-54

Marko Marelic , Dino Vukušić

Journal of Consumer Culture

Clarice Huston , Angela Cruz

Tuomas Kari

Veli-Matti Karhulahti , Tuomas Kari

Jory Deleuze , Maxime Christiaens

IJERD JOURNAL

Universal Access in the Information Society

Zaheer Hussain , Aqdas Malik

Maciej Behnke

Poslovna Izvrsnost

Toni Blažević , Dijana Čičin-Šain

Zaheer Hussain , GA Williams

Mariana Amaro

Veli-Matti Karhulahti

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Esports Psychology: A Systematic Literature Review

- No Comments

- January 4, 2023

Given the significant degree of cognitive skill and emotional regulation involved, esports performance is heavily impacted by psychological states. Esports Psychology research can also reveal valuable information about the motivations of spectators as well as players.

This systematic esports medicine literature review discusses the growing phenomenon of esports and the limited research that has been conducted on the psychology of esports. Esports have gained significant popularity in recent years, with a global audience of 385 million and an esport economy that grew 41.3% to reach $696 million in 2017. The literature on the psychology of esports has focused on three main topics: (1) the process of becoming an esports player, (2) the characteristics of esports players, and (3) the motivations of esports spectators.

Studies on becoming an esports player have explored the elements that make a career in esports attractive to players and have examined the transformation of identity that players go through as they become professionalized gamers. These studies suggest that becoming a professional esports player is similar to the process of becoming a professional athlete in traditional sports, in terms of the requirements and practices such as training, practice, skill acquisition, and dedication to the ‘job’. However, some scholars have argued that considering esports as a sport and gaming as a form of work may have negative impacts on individuals and society.

Studies on the characteristics of esports players have looked at various mental skills and motivational patterns among esports players, as well as differences between esports players and casual gamers. These studies have found that esports players tend to have high levels of motivation, determination, and focus, as well as good problem-solving skills and spatial awareness. They also tend to have a growth mindset, viewing challenges and failures as opportunities for learning and improvement. There are also some differences between esports players and casual gamers in terms of their motivations for playing, with esports players being more driven by competition and achievement and casual gamers being more motivated by relaxation and enjoyment.

Studies on the motivations of esports spectators have investigated why individuals watch esports and the factors that contribute to their satisfaction as spectators. These studies have found that esports viewers are motivated by factors such as the drama and excitement of the matches, the enjoyment of game commentary and skills displayed by the players, and their attachment to teams. Factors such as novelty and acquiring knowledge also influence the frequency of esports viewing, while aesthetics and aggression do not have a significant impact.

Overall, the research on the psychology of esports suggests that esports involve complex and varied psychological processes and motivations, and that further research is needed in this area. These studies provide insight into the motivations and characteristics of esports players and spectators, and highlight the similarities and differences between esports and traditional sports.

Based on the research reviewed in the text provided, there are several unique considerations that coaches or support staff working in esports should take away from this study:

- Esports players tend to have high levels of motivation, determination, and focus, as well as good problem-solving skills and spatial awareness. Coaches and support staff should be aware of these characteristics and consider how they can be fostered and developed in their players.

- Esports players are driven by competition and achievement, and are motivated by the process of becoming a professional player. Coaches and support staff should be aware of these motivations and consider how they can create a competitive and achievement-oriented environment for their players.

- There are some differences between esports players and casual gamers in terms of their motivations for playing, with esports players being more driven by competition and achievement and casual gamers being more motivated by relaxation and enjoyment. Coaches and support staff should be aware of these differences and consider how they can address the unique motivations of their players.

- Esports viewers are motivated by factors such as the drama and excitement of the matches, the enjoyment of game commentary and skills displayed by the players, and their attachment to teams. Coaches and support staff should be aware of these motivations and consider how they can create a viewing experience that meets the needs of their audience.

- Factors such as novelty and acquiring knowledge also influence the frequency of esports viewing. Coaches and support staff should consider how they can incorporate these elements into their players’ and teams’ narratives and storylines to increase viewer engagement.

Bányai F, Griffiths MD, Király O, Demetrovics Z. The Psychology of Esports: A Systematic Literature Review. J Gambl Stud. 2019 Jun;35(2):351-365. doi: 10.1007/s10899-018-9763-1. PMID: 29508260.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29508260/

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- Esports Exercise (1)

- Esports Fitness (6)

- Esports Health and Wellness (9)

- Esports Medicine (33)