- Open access

- Published: 21 September 2023

A systematic review on gender dysphoria in adolescents and young adults: focus on suicidal and self-harming ideation and behaviours

- Elisa Marconi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6722-8390 1 na1 ,

- Laura Monti ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8339-265X 1 na1 ,

- Angelica Marfoli ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0007-7324-577X 2 ,

- Georgios D. Kotzalidis ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0281-6324 3 , 4 , 7 ,

- Delfina Janiri ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2485-6121 4 , 7 ,

- Cecilia Cianfriglia ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0000-6777-7007 2 ,

- Federica Moriconi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1593-0043 1 ,

- Stefano Costa ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0137-2370 5 ,

- Chiara Veredice ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2267-8077 6 ,

- Gabriele Sani ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9767-8752 4 , 7 &

- Daniela Pia Rosaria Chieffo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0130-6584 1 , 8

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health volume 17 , Article number: 110 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

4448 Accesses

1 Citations

17 Altmetric

Metrics details

Introduction

Gender dysphoria (GD) is characterized by the incongruence between one’s experienced and expressed gender and assigned-sex-at-birth; it is associated with clinically significant distress. In recent years, the number of young patients diagnosed with GD has increased considerably. Recent studies reported that GD adolescents present behavioural and emotional problems and internalizing problems. Furthermore, this population shows a prevalence of psychiatric symptoms, like depression and anxiety. Several studies showed high rates of suicidal and non-suicidal self-injurious thoughts and behaviour in GD adolescents. To increase understanding of overall mental health status and potential risks of young people with GD, this systematic review focused on risk of suicide and self-harm gestures.

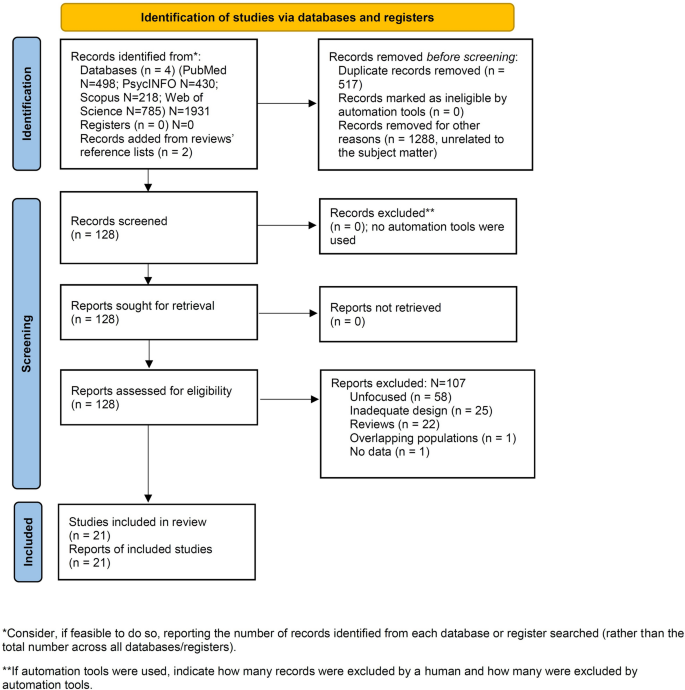

We followed the PRISMA 2020 statement, collecting empirical studies from four electronic databases, i.e., PubMed, Scopus, PsycINFO, and Web of Science.

Twenty-one studies on GD and gender nonconforming identity, suicidality, and self-harm in adolescents and young adults met inclusion criteria. Results showed that GD adolescents have more suicidal ideation, life-threatening behaviour, self-injurious thoughts or self-harm than their cisgender peers. Assessment methods were heterogeneous.

A standardised assessment is needed. Understanding the mental health status of transgender young people could help develop and provide effective clinical pathways and interventions.

Gender dysphoria (GD) is a condition characterized by a marked incongruence between one’s experienced and expressed gender and the one assigned at birth and is often associated with clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning, especially when reported early [ 1 ]. In recent years, the number of young patients diagnosed with GD or and gender-diverse identity—including nonbinary and questioning sexual identities—has considerably increased [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ]. Current studies document that this population may be exposed to a higher risk of adverse events affecting health status and well-being [ 6 , 7 ]. This further impacted this vulnerable population, with the most negative consequences for those who experience a gender not congruent with the one they were assigned at birth [ 8 , 9 , 10 ]. Indeed, children and adolescents with GD and transgender or transgender and gender nonconforming (TGNC) are described as a psychologically and socially vulnerable population, facing a wide range of physical and mental health concerns that could benefit from early intervention [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. GD during adolescence develops in individuals whose brain is still developing to reach full maturity only some years later, hence the need to dedicate special attention to this population.

As a population perceiving gender minority stress [ 14 ], adolescents with GD are likely to lack social acceptance and suffer stigma laid upon them by others [ 15 ], but also tend to internalisation [ 16 ]. A corollary may be that several studies found adolescents with GD, compared to their age-matched cisgender peers, to show more often behavioural and emotional problems and higher levels of individual distress-generating internalising problems, rather than environment-perturbing externalising problems [ 17 , 18 , 19 ]. Consequently, adolescents with GD show a higher prevalence of psychiatric issues, such as depression and anxiety disorders [ 17 , 20 , 21 ], likely due to social stigma.

Adolescents and young adults with GD and gender-diverse identity report higher suicidal thinking, planning, and attempts as well as non-suicidal self-harming thoughts and behaviours (NSSI) than the general population [ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 ]. Suicidality is an umbrella term including suicidal ideation, suicidal behaviours, and suicide attempts and plans which are correlated to the desire to die [ 33 ]; we will use suicidality sparingly in this paper and focus instead upon the above-mentioned specific terms, when possible. Non-suicidal self-harming behaviours and thoughts, however, refer to self-injurious acts without intending to end one’s own life, but involve self-punishment or negative emotion regulation [ 34 ]. In both cases, early age at onset has been identified as an important vulnerability factor, with onset during childhood and adolescence being associated with a poorer prognosis [ 17 ], based on different surveys of high-school students [ 31 ]. For example, in New Zealand, 20% of students with GD reported attempting suicide in the past 12 months, compared to 4% of all students [ 35 ]. Similarly, in the United States, 15% of students with GD reported a suicide attempt requiring medical treatment in the last 12 months, compared to 3% of all students [ 36 , 37 , 38 ]. In another American survey, 41% of students with GD reported having attempted suicide during their lifetime, compared to 14% of all students [ 39 ]. Moreover, Surace and her colleagues [ 40 ] found a mean prevalence of 28.2% for NSSI, 28.0% for suicidal ideation, and 14.8% for suicide attempts in young TGNC clinical populations up to 25 years old.

Besides aspects of GD like body dysmorphic disorder, feeling uncomfortable in one’s own body, and hopelessness about obtaining gender-affirming medical procedures, a possible contribution to elevated suicidal risk and behaviours in the GD population might lie within the social stigma experienced by TGNC adolescents, such as discrimination, prejudice, social stress, and ostracism within the peer group and/or family [ 41 ]. Suicidal ideation and self-injurious behaviours generally relate to significant emotional problems, such as depressive and anxiety symptoms, which in turn trigger psychosocial and biological imbalance, could increase the wish to die [ 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 ], thus adding to the above.

In summary, several studies have shown higher rates of suicidal and non-suicidal self-harming thoughts and behaviours in adolescents and young adults with GD and gender-diverse identity—such as nonbinary and questioning sexual identity—compared to their male and female cisgender peers. However, the evidence heretofore is piecemeal, probably due to social stigma currently associated with GD and the concern of stigmatising individuals suffering from this condition. To better understand the mental state of adolescents and young adults with TGNC, we conducted a systematic review focusing on the risk for suicide and self-harming gestures in the GD population. The aim of this review was to estimate the frequency of suicidal and self-harm behaviour in adolescents and young adults with GD, comparing them with cisgender adolescents where possible.

We performed a systematic review in compliance with the 2020 PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews and meta-analyses [ 46 ] to increase comprehensiveness and transparency of reporting.

Information sources and database search

To systematically collect empirical studies on the possible relation between suicidality/self-harming and GD in adolescents and young adults, several keywords were used to search for appropriate publications in four electronic databases, i.e., PubMed, Scopus, PsycINFO, and Web of Science since their inception and no date or language restriction.

Authors conducted the search separately in each database using the following agreed upon search strategy for PubMed and adapting the search for the other databases: (suicid* OR self-injur* OR self-harm* OR self-inflict* OR self-lesion*) AND (gender dysphori* OR transgender) AND (child* OR adolesc* OR "young adult*" OR youth* OR "school age"). Since the terms GD and transgender are used by many people as synonymous, in our searches we used both terms to identify possible eligible articles.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria were a study published in a peer-reviewed journal, reporting data on suicide and related behaviours (thinking, planning, and attempts) and/or non-suicidal self-harming thoughts and acts (using methods that reliably obtain the desired result) in adolescent and young adult (14–27 years old) samples with GD/transgender status/gender diverse identity.

Exclusion criteria were studies conducted on children or adult samples and those with mixed populations not providing data for adolescents and young adults separately. Also, opinion papers, such as editorials, letters to the editor, and hypotheses without providing data were excluded, as well as case reports or series, reviews/meta-analyses, animal studies, studies with inadequate/poor methodology and inadequate reporting of data, unfocused, or unrelated to the subject matter. All inter- and intra-database duplicates were removed, as well as abstracts, meeting presentations and studies presenting incomplete data.

Although reviews and meta-analyses were not included, their reference lists were screened to identify additional eligible publications. Eligibility for each study was decided with Delphi rounds among all authors until complete consensus was reached.

Data extraction

The analysis was conducted by all authors, who applied the eligibility criteria on each database. Each author conducted the selection process separately from others; at a final step, all authors compared their results in Delphi rounds (either in-person or remotely) aimed at obtaining full consensus.

Data collection and risk of bias assessment

Data collected for each study included country of origin, number of paediatric patients, demographic information (age and biological sex), presence/absence of GD and if present, type of GD, and clinical symptoms focused on self-harm (suicide behaviour, suicidal ideation, suicidal intent and planning, non-suicidal self-harm, and other self-injurious behaviour).

The evaluation of the risk of bias was conducted by a quality index derived from the Qualsyst’ Tool [ 47 ]. The quality of selected studies was assessed independently by all investigators and disagreements were resolved by consensus (results of risk-of-bias for all studies in the Additional file 1 ).

Identified studies

On February 7, 2023, we located 1416 articles (Fig. 1 , PRISMA flowchart) [ 39 ], of which 128 articles were assessed for eligibility. Of these papers, 107 articles were excluded according to eligibility criteria; 21 dealing with the relationship between GD and gender non-conforming identity, and suicidality and self-harm in adolescents and young adults met inclusion criteria.

PRISMA2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews: Search findings and selection with detailed reasons for exclusion

For the purpose of this systematic review, we have focused our analyses on these 21 studies. Figure 1 provides a PRISMA flow diagram showing search results.

Due to the breadth of the topic and the variety of variables included in this systematic review, the subject matter was organized according to the categories of psychopathological symptoms of interest in the study (Tables 1 and 2 ) and a final mixed category (Table 3 ). Of 21 studies meeting the inclusion criteria, there were 2 studies where self-harming behaviours and thoughts was the outcome in TGNC adolescents (Table 1 ), 6 studies where suicide was the outcome (Table 2 ), and 13 studies where the outcome was committing suicide combined to self-injurious attitudes (Table 3 ).

The 21 studies were mainly from the United States, the United Kingdom and Europe. Included studies were also conducted in China, Iran, Turkey, Canada and Australia. Studies were non-interventional and observational, with 17 being cross-sectional or retrospective and 4 longitudinal.

GD and non-suicidal self-harming ideation and behaviours were investigated by two studies [ 48 , 49 ], GD and suicidality by six studies [ 6 , 17 , 24 , 29 , 39 , 51 ], and GD and both suicidality and non-suicidal self-harm by 13 [ 11 , 21 , 22 , 25 , 30 , 50 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 ]; of these studies, four [ 11 , 21 , 55 , 58 ] detected the presence of internalizing problems (depressive and anxiety disorders) in GD adolescents and young adults. Detailed results are provided in the Additional file 1 .

Summary results

Detailed results of each study are shown in Tables 1 – 3 and in the Additional file 1 . We will here summarise results in GD and transgender populations regarding studies of (1) non-suicidal self-harm, (2) suicidal ideation and attempts, and (3) non-suicidal self-harm, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts combined.

- Non-suicidal self-harming was explored in two studies [ 48 , 49 ]; transgender adolescents showed higher tendency toward self-harm ideation than cisgender adolescents, while non-suicidal self-inflicted behaviours were more common in cisgender males and females than among transgender adolescents [ 49 ]. AFAB adolescents showed nominally more lifetime and current NSSI than AMAB, but this did not reach statistical significance [ 48 ] (Table 1 ).

- Suicidal thinking and attempts only were examined in six studies [ 6 , 17 , 24 , 29 , 39 , 51 ] and generally identified a high prevalence in GD/transgender populations of suicide behaviours and attempts, ranging from 14.3% of severe suicidal ideation in Heino et al. [ 29 ] to a cumulative “high risk” of 80.9% in Alizadeh Mohajer et al. [ 6 ]; however, studies used different assessment instruments, so it becomes difficult to draw conclusions as to the real extent of suicidality in our target population. Gender-diverse adolescents displayed high suicidal ideation (Table 2 ). Transgender/GD adolescents displayed more suicidal behaviour than cisgender adolescents, either males or females [ 39 ]. Suicidality did not differ between AMAB and AFAB transgender adolescents/younger adults [ 51 ].

- Suicidality and non-suicidal self-harm combined were explored in thirteen studies [ 11 , 21 , 22 , 25 , 30 , 50 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 ]. Both NSSI and suicidality were higher in transgender/GD youths than in cisgender participants. AMAB and AFAB showed higher NSSI and suicidality rates than cisgender boys and girls [ 11 ] (Table 3 ).

Additional considerations will be detailed further on.

The last decade has seen an increase in cases of GD in adolescents worldwide and our knowledge of the epidemiological and clinical features continues to evolve [ 59 ]. An adequate understanding of the phenomenon and any related symptoms is important for the early management and possible prevention of distress. Indeed, the literature has highlighted the existence of a high association of psychological and psychiatric symptoms in adolescents with GD.

Several studies used different methods to investigate whether transgender identity and clinical outcomes in the general adolescent population are related [ 6 , 17 , 21 , 22 , 24 , 25 , 29 , 30 , 39 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 ]. The present review focused particularly on high-severity psychological symptoms in young people, such as self-harm and suicidal symptomatology. Indeed, the results of the studies underline a statistically significant correlation between youth TGNC—including gender dysphoric, non-binary and questioning adolescents—and prevalence of suicidal thinking and plans/attempts and self-harming thoughts and behaviours compared to cisgender populations [ 20 , 29 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 ]. Currently, there is a dearth of results from population-based samples, hence generalizing current findings is still very premature [ 59 ]. Despite progress and availability of resilience factors to face stigma and discrimination in some societies and social groups, there are considerable anti-LGBT attitudes in some countries and other social groups, ensuing in GD adolescents showing more mental symptoms and distress compared to cisgender peers [ 52 , 66 , 67 ]. Gender dysphoric adolescents show higher rates of depression leading to suicidal risk and engage in more self-injurious behaviours than their cisgender peers, confirming that a significant proportion of this population experience severe suicidal ideation and almost one third attempt suicide [ 4 ]. Other studies highlight that half of transgender youths are diagnosed with depression and anxiety disorders as well as poorer overall health and sleep quality [ 11 , 66 , 68 ]. Furthermore, puberty appears to exacerbate mental health problems in people with GD [ 30 ].

The main theoretical models, such as the gender minority stress model [ 69 ], identify potential risk factors among transgender individuals, link exposure to stigma, discrimination, and lack of social support. Previous research identified sexual minority status as a fundamental risk factor for own life-threatening behaviours [ 70 ]. In fact, adolescents diagnosed with GD experience victimization from their peers, negative parental reactions to their gender-nonconforming expression and identity, and family violence. These exogenous factors often lead transgender individuals to experience personal distress and isolation, which might elicit higher rates of own-life-threatening behaviours, such as suicidal attempts and ideation and self-harm thoughts than their heterosexual peers [ 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 ].

Overall, results of the studies included in this systematic review confirmed that, compared to cisgender adolescents, TGNC adolescents reported a significantly higher frequency of suicidal attempts, suicidal thoughts, making suicide plans, self-harm ideation and deliberately participating in self-harm acts. Higher depressive and anxiety symptoms and lower overall physical health were also positively associated with GD [ 11 , 55 , 57 , 58 , 74 ].

However, results were heterogeneous. Specifically, Wang and colleagues [ 11 ] indicated that among the gender minority groups transgender girls had the greater risk of planning and attempting suicide, transgender boys had the highest risk of performing deliberate self-harm, and questioning youth AFAB had the highest risk of suicidal ideation. Similar results were obtained in another study [ 24 ], with the risk ratios analysis highlighting the greater rate of suicidality among birth-assigned females. This pattern is consistent with many other studies showing that suicidality is more common among AFAB adolescents than it is among AMAB youth [ 75 ]. Some studies found possible gender differences between AFAB and AMAB and possible consequences for their mental health, suggesting that although AMAB might experience more stigmatization and preconceptions, AFAB youth seem to cope differently with distress [ 17 , 25 , 48 ]. Nevertheless, this outcome was different from Toomey and colleagues’ work [ 39 ], which found that transgender boys had a higher rate of attempted suicide than transgender girls.

At any rate, despite these within-group discrepancies, general findings emerging from quantitative studies provide evidence that a large proportion of adolescents referred for GD and other transgender youth, whether “AFAB” or “AMAB”, have a substantial co-occurring history of psychosocial and psychological vulnerability, causing a higher risk for suicidal ideation and life-threatening behaviours, such as self-harm thoughts and self-injurious gestures [ 70 , 76 ].

Since society is becoming increasingly liquid according to Zygmunt Bauman [ 77 ], more cases of transgender states and GD are anticipated to occur; this will mean that we will have more of the general population at enhanced risk for self-harming acts, suicidal thinking, and suicidal behaviour. Under this perspective, it should be important to develop a comprehensive psychological assessment aimed at identifying people at risk of the above behaviours so to enforce preventive programmes [ 78 , 79 , 80 ].

For this reason, results provided by this systematic review may enhance the knowledge of health professionals about adolescents referred for GD. Furthermore, a better understanding of the mental health status of transgender youth and the associated risks could help to develop and provide effective interventions. The need for more knowledge and tools is also a key aspect of supporting each individual properly [ 30 , 81 ]. Finally, increasing social awareness and scientific knowledge can also help target support programs for parents. Indeed, parents could benefit from interventions dedicated to understanding the impact of attitudes, behaviours and decisions, as well as assisting them in the therapeutic paths they take with their children with GD [ 70 ].

Limitations . This review contains heterogeneous data that could not be subjected to a meta-analysis. Heterogeneity regarded the instruments used to assess the populations included and the variables examined. To add to the high heterogeneity, the population under study belonged to multiple categories, such as cisgender males, cisgender females, individuals assigned female at birth whose experienced gender was male (so-called female-to-male transgender), individuals assigned male at birth whose experienced gender was female (so-called male-to-female transgender), and nonbinary. Often studies did not differentiate possible transgender from nonbinary identities. We attempted at focusing on GD only, but had to deal also with other populations as well, since the literature treats these populations as they were one and the same, which of course is not the case. Furthermore, a distinction between self-harm and suicide attempts was not always possible. Moreover, the social stigma laid upon gender diverse populations and current cultural trends may have directly or indirectly affected the writing of this review and its final results and conclusions.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the overall findings emerging from this review provide evidence that a large proportion of adolescents with GD have a substantial concomitant history of psychosocial and psychological vulnerability, with a higher risk of suicidal ideation, life-threatening behaviour, and self-injurious thoughts or self-harm. Understanding the mental health status of transgender young people could help developing and providing effective clinical pathways and interventions. The relatively new issue of suicide in adolescent/young adult populations currently suffers from poor assessment standardization. There is a need for standardized assessment, culturally adapted research, and destigmatisation of this socially vulnerable population to address the issue of increased suicidal thinking and attempts.

Availability of data and materials

American Psychiatric Association. diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition, text revision (DSM-5-TR). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing Inc.; 2022. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 .

Book Google Scholar

Zucker KJ. Epidemiology of gender dysphoria and transgender identity. Sex Health. 2017;14(5):404–11. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH17067 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Indremo M, White R, Frisell T, Cnattingius S, Skalkidou A, Isaksson J, Papadopoulos FC. Validity of the gender dysphoria diagnosis and incidence trends in Sweden: a nationwide register study. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):16168. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-95421-9.4 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Thompson L, Sarovic D, Wilson P, Sämfjord A, Gillberg C. A PRISMA systematic review of adolescent gender dysphoria literature: 1) epidemiology. PLOS Glob Publ Health. 2022;2(3):e0000245. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000426 .

Article Google Scholar

Oshima Y, Matsumoto Y, Terada S, Yamada N. Prevalence of gender dysphoria by gender and age in japan: a population-based internet survey using the utrecht gender dysphoria scale. J Sex Med. 2022;19(7):1185–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2022.03.605 .

Alizadeh Mohajer M, Adibi A, Mozafari AA, Sahebi A, Bakhtiyari A. Suicidal ideation in patients with gender identity disorder in western Iran from March 2019 to March 2020. Int J Med Toxicol Forensic Med. 2020;10(4):31353. https://doi.org/10.32598/ijAMABm.v10i4.31353 .

Shin KE, Baroni A, Gerson RS, Bell KA, Pollak OH, Tezanos K, Spirito A, Cha CB. Using behavioral measures to assess suicide risk in the psychiatric emergency department for youth. Child Psychiatr Hum Dev. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-023-01507-y .

Perl L, Oren A, Klein Z, Shechner T. Effects of the COVID19 pandemic on transgender and gender non-conforming adolescents’ mental health. Psychiatr Res. 2021;302:114042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114042 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Hawke LD, Hayes E, Darnay K, Henderson J. Mental health among transgender and gender diverse youth: an exploration of effects during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2021;8(2):180–7. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000467 .

Mitchell KJ, Ybarra ML, Banyard V, Goodman KL, Jones LM. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on perceptions of health and well-being among sexual and gender minority adolescents and emerging adults. LGBT Health. 2022;9(1):34–42. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2021.0238 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Wang Y, Yu H, Yang Y, Drescher J, Li R, Yin W, Yu R, Wang S, Deng W, Jia Q, Zucker KJ, Chen R. Mental health status of cisgender and gender-diverse secondary school students in China. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(10):e2022796. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.22796 .

Andresen JB, Graugaard C, Andersson M, Bahnsen MK, Frisch M. Adverse childhood experiences and mental health problems in a nationally representative study of heterosexual, homosexual and bisexual danes. World Psychiatr. 2022;21(3):427–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.21008 .

Sun S, Xu S, Guy A, Guigayoma J, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Operaio D, Chen R. Analysis of psychiatric symptoms and suicide risk among younger adults in china by gender identity and sexual orientation. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(3):e232294. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.2294 .

Hunter J, Butler C, Cooper K. Gender minority stress in trans and gender diverse adolescents and young people. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2021;26(4):1182–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591045211033187 .

Joseph AA, Kulshreshtha B, Shabir I, Marumudi E, George TS, Sagar R, Mehta M, Ammini AC. Gender issues and related social stigma affecting patients with a disorder of sex development in India. Arch Sex Behav. 2017;46(2):361–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0841-0 .

Jackman KB, Dolezal C, Bockting WO. Generational differences in internalized transnegativity and psychological distress among feminine spectrum transgender people. LGBT Health. 2018;5(1):54–60. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2017.0034 .

Fisher AD, Ristori J, Castellini G, Sensi C, Cassioli E, Prunas A, Mosconi M, Vitelli R, Dèttore D, Ricca V, Maggi M. Psychological characteristics of Italian gender dysphoric adolescents: a case-control study. J Endocrinol Invest. 2017;40(9):953–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-017-0647-5 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

de Vries AL, Doreleijers TA, Steensma TD, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Psychiatric comorbidity in gender dysphoric adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52(11):1195–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02426.x .

Zucker KJ, Wood H, Singh D, Bradley SJ. A developmental, biopsychosocial model for the treatment of children with gender identity disorder. J Homosex. 2012;59(3):369–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2012.653309 .

Dhejne C, Van Vlerken R, Heylens G, Arcelus J. Mental health and gender dysphoria: a review of the literature. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2016;28(1):44–57. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2015.1115753 .

Kozlowska K, McClure G, Chudleigh C, Maguire AM, Gessler D, Scher S, Ambler GR. Australian children and adolescents with gender dysphoria: clinical presentations and challenges experienced by a multidisciplinary team and gender service. Hum Syst Ther, Cult Attach. 2021;1(1):70–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/26344041211010777 .

Skagerberg E, Parkinson R, Carmichael P. Self-harming thoughts and behaviors in a group of children and adolescents with gender dysphoria. Int J Transgenderism. 2013;14(2):86–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2013.817321 .

Aitken M, VanderLaan DP, Wasserman L, Stojanovski S, Zucker KJ. Self-Harm and suicidality in children referred for gender dysphoria. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55(6):513–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.04.001 .

de Graaf NM, Steensma TD, Carmichael P, VanderLaan DP, Aitken M, Cohen-Kettenis PT, de Vries ALC, Kreukels BPC, Wasserman L, Wood H, Zucker KJ. Suicidality in clinic-referred transgender adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;31(1):67–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01663-9 .

Thoma BC, Salk RH, Choukas-Bradley S, Goldstein TR, Levine MD, Marshal MP. Suicidality disparities between transgender and cisgender adolescents. Pediatrics. 2019;144(5):e20191183. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-1183 .

Mann GE, Taylor A, Wren B, de Graaf N. Review of the literature on self-injurious thoughts and behaviours in gender-diverse children and young people in the United Kingdom. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;24(2):304–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104518812724 .

Dickey LM, Budge SL. Suicide and the transgender experience: a public health crisis. Am Psychol. 2020;75(3):380–90. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000619 .

Hatchel T, Polanin JR, Espelage DL. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among LGBTQ youth: meta-analyses and a systematic review. Arch Suicide Res. 2021;25(1):1–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2019.1663329 .

Heino E, Fröjd S, Marttunen M, Kaltiala R. Transgender identity is associated with severe suicidal ideation among finnish adolescents. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2021-0018 .

Hartig A, Voss C, Herrmann L, Fahrenkrug S, Bindt C, Becker-Hebly I. Suicidal and nonsuicidal self-harming thoughts and behaviors in clinically referred children and adolescents with gender dysphoria. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2022;27(3):716–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591045211073941 .

Biggs M. Suicide by clinic-referred transgender adolescents in the United Kingdom. Arch Sex Behav. 2022;51(2):685–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02287-7 .

Faruki F, Patel A, Jaka S, Kaur M, Sejdiu A, Bajwa A, Patel RS. Gender dysphoria in pediatric and transitional-aged youth hospitalized for suicidal behaviors: a cross-national inpatient study. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2023;25(2):46284. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.22m03352 .

O’Connor RC, Nock MK. The psychology of suicidal behaviour. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(1):73–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70222-6 .

Claes L, Vandereycken W. Self-injurious behavior: differential diagnosis and functional differentiation. Compr Psychiatry. 2007;48(2):137–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.10.009 .

Clark TC, Lucassen MF, Bullen P, Denny SJ, Fleming TM, Robinson EM, Rossen FV. The health and well-being of transgender high school students: results from the New Zealand adolescent health survey (Youth’12). J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(1):93–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.11.008 .

Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Queen B, Lowry R, Chyen D, Whittle L, Thornton J, Lim C, Bradford D, Yamakawa Y, Leon M, Brener N, Ethier KA. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Surveill Summ. 2018;67(8):1–114. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6708a1 .

Johns MM, Lowry R, Andrzejewski J, Barrios LC, Demissie Z, McManus T, Rasberry CN, Robin L, Underwood JM. Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school students—19 states and large urban school districts 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(3):67–71. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6803a3 .

Jackman KB, Caceres BA, Kreuze EJ, Bockting WO. Suicidality among gender minority youth: analysis of 2017 youth risk behavior survey data. Arch Suicide Res. 2021;25(2):208–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2019.1678539 .

Toomey RB, Syvertsen AK, Shramko M. Transgender adolescent suicide behavior. Pediatrics. 2018;142(4):e20174218. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-4218 .

Surace T, Fusar-Poli L, Vozza L, Cavone V, Arcidiacono C, Mammano R, Basile L, Rodolico A, Bisicchia P, Caponnetto P, Signorelli MS, Aguglia E. Lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicidal behaviors in gender non-conforming youths: a meta-analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;30(8):1147–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01508-5 .

Arnold JC, McNamara M. Transgender and gender-diverse youth: an update on standard medical treatments for gender dysphoria and the sociopolitical climate. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000001256 .

Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(5):674–97. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 .

Hendricks ML, Testa RJ. A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: an adaptation of the minority stress model. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2012;43(5):460–7. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029597 .

de Graaf NM, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Carmichael P, de Vries ALC, Dhondt K, Laridaen J, Pauli D, Ball J, Steensma TD. Psychological functioning in adolescents referred to specialist gender identity clinics across Europe: a clinical comparison study between four clinics. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;27(7):909–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-017-1098-4 .

Rotondi NK, Bauer GR, Scanlon K, Kaay M, Travers R, Travers A. Prevalence of and risk and protective factors for depression in female-to-male transgender ontarians: results from the trans PULSE project. Can J Commun Ment Health. 2011;30(2):135–55. https://doi.org/10.7870/cjcmh-2011-0021 .

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br Med J. 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71 .

Kmet LM, Lee RC, Cook LS. Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. HTA Initiative # 13. Edmonton: Alberta Herit Found Med Res. 2004

Arcelus J, Claes L, Witcomb GL, Marshall E, Bouman WP. Risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury among trans youth. J Sex Med. 2016;13(3):402–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.01.003 .

Butler C, Joiner R, Bradley R, Bowles M, Bowes A, Russell C, Roberts V. Self-harm prevalence and ideation in a community sample of cis, trans and other youth. Int J Transgenderism. 2019;20(4):447–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2019.1614130 .

Mak J, Shires DA, Zhang Q, Prieto LR, Ahmedani BK, Kattari L, Becerra-Culqui TA, Bradlyn A, Flanders WD, Getahun D, Giammattei SV, Hunkeler EM, Lash TL, Nash R, Quinn VP, Robinson B, Roblin D, Silverberg MJ, Slovis J, Tangpricha V, Vupputuri S, Goodman M. Suicide attempts among a cohort of transgender and gender diverse people. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59(4):570–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2020.03.026 .

Yüksel Ş, Aslantaş Ertekin B, Öztürk M, Bikmaz PS, Oğlağu Z. A Clinically neglected topic: risk of suicide in transgender individuals. Noro Psikiyatri Arsivi. 2017;54(1):28–32. https://doi.org/10.5152/npa.2016.10075 .

Veale JF, Watson RJ, Peter T, Saewyc EM. Mental health disparities among canadian transgender youth. J Adolesc Health. 2017;60(1):44–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.09.014 .

Becerra-Culqui TA, Liu Y, Nash R, Cromwell L, Flanders WD, Getahun D, Giammattei SV, Hunkeler EM, Lash TL, Millman A, Quinn VP, Robinson B, Roblin D, Sandberg DE, Silverberg MJ, Tangpricha V, Goodman M. Mental health of transgender and gender nonconforming youth compared with their peers. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5):e20173845. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-3845 .

Bechard M, VanderLaan DP, Wood H, Wasserman L, Zucker KJ. Psychosocial and psychological vulnerability in adolescents with gender dysphoria: a “proof of principle” study. J Sex Marital Ther. 2017;43(7):678–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2016.1232325 .

Peterson CM, Matthews A, Copps-Smith E, Conard LA. Suicidality, self-harm, and body dissatisfaction in transgender adolescents and emerging adults with gender dysphoria. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2017;47(4):475–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12289 .

Mitchell HK, Keim G, Apple DE, Lett E, Zisk A, Dowshen NL, Yehya N. Prevalence of gender dysphoria and suicidality and self-harm in a national database of paediatric inpatients in the USA: a population-based, serial cross-sectional study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2022;6(12):876–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00280-2 .

Karvonen M, Karukivi M, Kronström K, Kaltiala R. The nature of co-morbid psychopathology in adolescents with gender dysphoria. Psychiatry Res. 2022;317:114896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114896 .

Tordoff DM, Wanta JW, Collin A, Stepney C, Inwards-Breland DJ, Ahrens K. Mental health outcomes in transgender and nonbinary youths receiving gender-affirming care. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e220978–e220978. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0978 .

Kaltiala-Heino R, Bergman H, Työläjärvi M, Frisén L. Gender dysphoria in adolescence: current perspectives. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2018;9:31–41. https://doi.org/10.2147/AHMT.S135432 .

Connolly MD, Zervos MJ, Barone CJ II, Johnson CC, Joseph CL. The mental health of transgender youth: advances in understanding. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(5):489–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.012 .

Bränström R, van der Star A, Pachankis JE. Untethered lives: barriers to societal integration as predictors of the sexual orientation disparity in suicidality. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2020;55(1):89–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01742-6 .

Garthe RC, Blackburn AM, Kaur A, Sarol JN Jr, Goffnett J, Rieger A, Reinhart C, Smith DC. Suicidal ideation among transgender and gender expansive youth: mechanisms of risk. Transgender Health. 2022;7(5):416–22. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2021.0055 .

Clark KA, Hatzenbuehler ML, Bränström R, Pachankis JE. Sexual orientation-related patterns of 12-month course and severity of suicidality in a longitudinal, population-based cohort of young adults in Sweden. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2022;57(9):1931–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-022-02326-7 .

Bränström R, Stormbom I, Bergendal M, Pachankis JE. Transgender-based disparities in suicidality: a population-based study of key predictions from four theoretical models. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2022;52(3):401–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12830 .

Chang CJ, Feinstein BA, Fulginiti A, Dyar C, Selby EA, Goldbach JT. A longitudinal examination of the interpersonal theory of suicide for predicting suicidal ideation among LGBTQ+ youth who utilize crisis services: the moderating effect of gender. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2021;51(5):1015–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12787 .

Mezzalira S, Scandurra C, Mezza F, Miscioscia M, Innamorati M, Bochicchio V. Gender felt pressure, affective domains, and mental health outcomes among transgender and gender diverse (TGD) children and adolescents: a systematic review with developmental and clinical implications. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2022;20(1):785. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010785 .

Wolford-Clevenger C, Flores LY, Stuart GL. Proximal correlates of suicidal ideation among transgender and gender diverse people: a preliminary test of the three-step theory. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2021;51(6):1077–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12790 .

Lehavot K, Simpson TL, Shipherd JC. Factors associated with suicidality among a national sample of transgender veterans. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2016;46(5):507–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12233 .

Reisner SL, Vetters R, Leclerc M, Zaslow S, Wolfrum S, Shumer D, Mimiaga MJ. Mental health of transgender youth in care at an adolescent urban community health center: a matched retrospective cohort study. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(3):274–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.10.264 .

Grossman AH, D’Augelli AR. Transgender youth and life-threatening behaviors. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2007;37(5):527–37. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2007.37.5.527 .

D’Augelli AR, Grossman AH, Salter NP, Vasey JJ, Starks MT, Sinclair KO. Predicting the suicide attempts of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2005;35(6):646–60. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2005.35.6.646 .

Grossman AH, D’Augelli AR, Howell TJ, Hubbard S. Parent’reactions to transgender youth’gender nonconforming expression and identity. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2005;18(1):3–16. https://doi.org/10.1300/J041v18n01_02 .

Grossman AH, D’augelli AR, Salter NP. Male-to-female transgender youth: gender expression milestones, gender atypicality, victimization, and parents’ responses. J GLBT Fam Stud. 2006;2(1):71–92. https://doi.org/10.1300/J461v02n01_04 .

Randall AB, van der Star A, Pennesi JL, Siegel JA, Blashill AJ. Gender identity-based disparities in self-injurious thoughts and behaviors among pre-teens in the United States. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12937 .

Miranda-Mendizabal A, Castellví P, Parés-Badell O, Alayo I, Almenara J, Alonso I, Alonso J. Gender differences in suicidal behavior in adolescents and young adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Int J Public Health. 2019;64:265–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-018-1196-1 .

Horwitz AG, Berona J, Busby DR, Eisenberg D, Zheng K, Pistorello J, Albucher R, Coryell W, Favorite T, Walloch JC, King CA. Variation in suicide risk among subgroups of sexual and gender minority college students. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2020;50(5):1041–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12637 .

Bauman Z. Liquid modernity. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Polity Press; 2012.

Google Scholar

Adelson SL. & American academy of child and adolescent psychiatry (AACAP) committee on quality issues (CQI): practice parameter on gay, lesbian, or bisexual sexual orientation, gender nonconformity, and gender discordance in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51:957–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2012.07.004 .

Byne W, Bradley SJ, Coleman E, Eyler AE, Green R, Menvielle EJ, Meyer-Bahlburg HFL, Pleak RR, Tompkins DA. Report of the American psychiatric pssociation task force on treatment of gender identity disorder. Arch Sex Behav. 2012;41(4):759–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-9975-x .

Olson-Kennedy J, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Kreukels BPC, Meyer-Bahlburg HFL, Garofalo R, Meyer W, Rosenthal SM. Research priorities for gender nonconforming/transgender youth: gender identity development and biopsychosocial outcomes. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2016;23:172–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/MED.0000000000000236 .

Dunlop BJ, Coleman SE, Hartley S, Carter LA, Taylor PJ. Self-injury in young bisexual people: a microlongitudinal investigation (SIBL) of thwarted belongingness and self-esteem on non-suicidal self-injury. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2022;52(2):317–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12823 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate the help Drs. Alessio Simonetti and Evelina Bernardi provided in statistical issues.

This work has received no funding.

Author information

Elisa Marconi and Laura Monti are first authors as they equally contributed to the manuscript.

Authors and Affiliations

Clinical Psychology Unit, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS, Largo Agostino Gemelli 1, 00168, Rome, Italy

Elisa Marconi, Laura Monti, Federica Moriconi & Daniela Pia Rosaria Chieffo

Catholic University of the Sacred Heart—Rome, Largo Francesco Vito 1, 00168, Rome, Italy

Angelica Marfoli & Cecilia Cianfriglia

NESMOS Department (Neurosciences, Mental Health, and Sensory Organs), University of Rome “La Sapienza”, Via Di Grottarossa1035-1039, 00198, Rome, Italy

Georgios D. Kotzalidis

Department of Psychiatry, Department of Neuroscience, Head, Neck and Thorax, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS, Largo Agostino Gemelli 1, 00168, Rome, Italy

Georgios D. Kotzalidis, Delfina Janiri & Gabriele Sani

UOSD Operative Unit Psychiatry and Psychotherapy for Adolescents, Azienda USL Di Bologna, Ospedale MaggioreLargo Bartolo Nigrisoli, 2, 40133, Bologna, Italy

Stefano Costa

Pediatric Neuropsychiatry Unit, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS, 00168, Rome, Italy

Chiara Veredice

Institute of Psychiatry, Department of Neuroscience, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart—Rome, Largo Francesco Vito 1, 00168, Rome, Italy

Departement of Life Sciences and Public Health Department, Catholic University of Sacred Heart, 00168, Rome, Italy

Daniela Pia Rosaria Chieffo

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

EM, LM, AM, CC, and DPRC. conceived the review. EM, LM, AM, CC, and GDK. organized and collected the material and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AM, EM, GDK, DJ, FM, and SC. performed literature searches. EM, LM, AM, CC and GDK. wrote the Methods and decided eligibility criteria. DPRC, GDK. and GS. supervised the writing of the manuscript. DPRC, CV, AM, GDK. and GS. revised the final version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript, read, and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Elisa Marconi .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

All authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1..

Supplement to Marconi et al. (2023)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Marconi, E., Monti, L., Marfoli, A. et al. A systematic review on gender dysphoria in adolescents and young adults: focus on suicidal and self-harming ideation and behaviours. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 17 , 110 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-023-00654-3

Download citation

Received : 04 April 2023

Accepted : 30 August 2023

Published : 21 September 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-023-00654-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Gender dysphoria

- Transgender

- Suicidal thinking

- Suicidal attempts

- Non-suicidal self-harm

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health

ISSN: 1753-2000

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

Practical Clinical Andrology pp 263–272 Cite as

Gender Dysphoria: Overview and Psychological Interventions

- Elisabetta Lavorato 5 ,

- Antonio Rampino 6 &

- Valentina Giorgelli 6

- Open Access

- First Online: 15 October 2022

8446 Accesses

1 Citations

4 Altmetric

In the DSM V, the condition known as “Gender Identity Disorder” becomes “Gender Dysphoria” in order to avoid the stigma of being labeled as carriers of psychopathology. Gender Dysphoria (GD) refers to mental discomfort deriving by incongruence between the expressed gender and the assigned one. The term Transgender refers to identities or gender expressions that differ from social expectations typically based on the birth assigned sex. Not all people living “Gender Variance” express psychological or physic discomfort. The personal gender identity develops influenced by emotionally significant relationships and by socialeducational environment, based on predisposing biological characteristics. Most of clinical and psycho-social studies agree on multifactorial nature of this process, focusing on the combined action of biological, psychological, social and cultural factors. The first symptoms of gender dysphoria may appear from first years of life and then they may persist in puberty and adulthood. The causes of Gender Dysphoria are still unclear.

Both psychosocial and biological factors have been called into question to explain the onset. The Gender Dysphoria Treatment aims to reduce, or to remove, suffering of person with GD and it is based on teamwork of psychologists, psychiatrists, endocrinologists and surgeons. The cure is, firstly, psychological and is provided by mental health experts. Hormone therapy can be prescribed to all people with persistent and well documented Gender Dysphoria if there are no medical contraindications; lastly, sex reassignment surgery. The formation and definition of transgender and transsexual identity obviously represents a specific complexity, to which is added an environmental, cultural and consequently individual and conditioning stigmatization.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

20.1 Introduction

The nosography of Gender Dysphoria (GD) has recently been object of an important change. In the Statistical and Diagnostic Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM V [ 1 ], this diagnosis was separated from paraphilias and sexual disorders, becoming an independent category. The most important innovative aspect introduced by the DSM V concerns the condition known as “Gender Identity Disorder”, which is now referred to as “Gender Dysphoria”. The new nomenclature emphasizes the salient aspect of distress overcoming the stigmatizing definition of “disorder”, previously used.

Literature reports that Gender Dysphoria (GD)—defined as marked incongruence between one’s expressed gender and her/his assigned gender [ 2 ] (APA 2014)—is associated with psychological suffering characterized by anxiety, depression, impaired relationships, and suicidal ideation. The difference between one’s expressed gender and her/his physical sexual characteristics is expressed by the desire to get rid of them and/or to have the primary and secondary sexual characteristics of the opposite gender. The peculiarity of this disorder is the coexistence of medical aspects (biological sex) and psychological aspects (subjective experience). Previous studies highlight that psychological risk does not derive from the gender inconsistency, but from childhood traumatic experiences in different contexts, such as family, school, and because of non-recognition of psychological and sexual identity [ 3 ]. The community non-acceptance persists in adulthood, magnified by cultural stereotypes.

Therefore, Gender Dysphoria (GD) represents the condition of partial or complete discordance between assigned sex, based on external genitalia, and the gender recognized by the brain. So, it is characterized by suffering, malaise, and stress. This existential state has an intrinsic complexity that deserves as much attention and management as the medical issues related. Therefore, in a service dedicated to GD, it is necessary to create a multidisciplinary team dealing with all aspects of the transition process. Accordingly, an elective modality of “cure” has been proposed: on the one hand, the person carrying GD is supported from a psychological point of view; on the other hand, s/he is allowed to choose how to transform his/her morphological characteristics according to his/her subjective experience of identity, through endocrinological and surgical treatments. Of note, Law number 164 on 14th April 1982 (“ Rules on the rectification of gender attribution ”) establishes the possibility of carrying out a Surgical Sex Reassignment (SSR) and/or a change of sex at registry office even without SSR. In any case, it is permitted only after a clear diagnosis of GD has been formulated by a psychiatrist.

In Italy, the Observatory on Gender Identity (ONIG) has identified the centres able to take care of these cases throughout the national territory. Such centres must meet the criteria of Standards of Care (SOC) of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health [ 4 ], as defined by the Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association. In fact, in all countries of the world, this Association reunited and supported people who, despite different skills, desire to develop the best possible practices and the most useful support to improve the quality of life of this population.

As a general expectation, people born with male sex identify themselves as men, while those born with female sex as women. Nonetheless, this is not what real experience teaches us and can be prejudicial if not detached from reality. In fact, a person, who experiences a so-called “Gender Variance”, does not recognize him/herself in this binary system occurring at birth. He/she does not perceive the gender identity as corresponding to birth assigned sex.

In fact, while there is biological sex depending on differences in chromosome numbers and genital conformation, gender identity is a more intimate feeling of belonging to the male or female gender, or to some combination of them. Therefore, Gender Identity allows people to say: “I am a man”, “I am a woman”, “I am a genderqueer”, regardless of the birth assigned sex.

The term Transgender refers to identities or gender expressions that differ from social expectations typically based on the birth assigned sex. Transgender people can have a binary gender identity (identifying themselves as women if at birth they were men or as men if at birth they were women) or non-binary (identifying themselves with subjective combination of genres). Not all people living “Gender Variance” express psychological or physical discomfort. Most of them find balance between the perception of oneself and the subjective model of relationships. On the other hand, if there is a psychological or physical distress, the so-called Gender Dysphoria, the person could feel the need to adapt the external reality (anatomical and personal data) to his or her emotional inner world. This is possible thanks to different interventions, including intake of feminizing or masculinizing hormones, surgical interventions, and/or modification of personal data. There are currently no data indicating a prevalence of people with gender variance. Nevertheless, there are data on the prevalence of Gender Dysphoria based on people entering specialized centres. Specifically, the World Professional Association for Transgender Health Standards of Care reported a prevalence of 1 in 11,900–45,000 for people assigned at birth to the male gender and 1 in 30,400–200,000 for people assigned at birth to the female gender.

The personal gender identity develops influenced by emotionally significant relationships and by social-educational environment, based on predisposing biological characteristics. Most of clinical and psycho-social studies agree on multifactorial nature of this process, focusing on the combined action of biological, psychological, social, and cultural factors.

20.2 Basic Concepts: Sexual and Gender Identity

To understand the experiences of Transgender people, we refer to behavioural and phenomenological markers of psychosexual development. Most of scholars refer to a tripartite model based on gender identity, gender role, and sexual orientation . Some authors also consider a further construct: gender expression . These components drive and guide the development of sexual identity . There are different definitions of gender identity ; first, it is not a stable construct because it is acquired step by step in the entire existence and it is influenced by different experiences. The sexual identity consists of biological sex (male or female according to certain biological parameters), gender identity (feeling male or female), gender role (adherence to the expectations of social context related to both biological sex and one’s own gender identity experience), and then sexual orientation (the gender towards which the individual feels sexual attraction).

The biological sex is the set of all biological characteristics of being female or male (biological sex): the sex chromosomes (XY for males and XX for females), the gonads (testes for males and ovaries for females), external genitalia, and secondary sexual characteristics (development of breasts, presence of face hair, tone of the voice, etc.) which appear during the sexual development (puberty).

Gender is a more complex construct and refers to characteristics depending on cultural, social, and psychological factors that define typical behaviours for men and women. For most people, biological sex and gender identity match. The term transgender identifies people with gender identity other than biological sex: for example, a person born as male, but feeling female (or vice versa). The condition that gender identity differs from biological sex is known as gender incongruence. The gender incongruence is not a disorder. In the last edition of International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (ICD-11), gender incongruence was declassified from the chapter of mental health and included in the chapter of sexual health . If psychological discomfort of gender incongruence is structured in persistent and specific symptoms with an associated alteration of the global functioning, that is Gender Dysphoria.

Epidemiological data : as previously reported, prevalence data of Gender Dysphoria in adults (>18 years) are collected by specialized centres. Such data are most probably underestimated because not all people with gender incongruence develop Gender Dysphoria, then not all people affected by Gender Dysphoria come to a specialized centre. The estimated prevalence of GD is 0.005–0.014% of people with biological male sex and 0.002–0.003% of people with biological female sex [ 5 ]. Therefore, gender dysphoria is more common in the MtF form with a male/female ratio of approximately 3:1. In children under 12, the male/female ratio ranges from 3:1 to 2:1; while in teenagers, over 12 years, the male/female ratio is about 1:1.7 [ 5 ]. We highlight Gender Dysphoria is independent from sexual preference, which indicates sexual and emotional attraction for a person of the same sex (homosexuality), of opposite sex (heterosexuality), or of both genders (bisexuality). Transgender people can have any sexual and sentimental orientation, for example, they can be heterosexual or lesbian, gay or bisexual.

20.3 Symptoms

Gender Dysphoria appears as malaise and discomfort towards one’s body, felt as a stranger; the same sense of strangeness is experienced towards behaviours and attitudes that are typical of one’s sex, within which the person does not recognize her/himself.

The first symptoms of gender dysphoria may appear from the very early years of life, 2–3 years. In studies on childhood, it was seen gender dysphoria remains until adulthood for 6–23% among males and 12–27% among females. In other words, less than a third of children, in whom gender dysphoria has been diagnosed, will maintain this condition even during adolescence. However, when gender dysphoria persists in the early stage of sexual development (puberty), it rarely disappears over time, and nearly all adolescents with gender dysphoria maintain this condition well into adulthood.

20.3.1 Children

Characteristic behaviours of gender dysphoria among children may include:

Desire to wear clothes, use toys or take part to games typically associated to the other gender, preferring to play with children of opposite biological sex.

Refusal to urinate as other children of the same biological sex do (standing for boys or sitting for girls).

Desire to get rid of their genitals and want to have genitals of the opposite biological sex (for example a boy may say he wants to get rid of his penis and a girl may wish to have a penis).

Extreme discomfort with the changes in the body that occur during puberty.

These behaviours in gender dysphoria are associated with deep suffering and distress at school and in relationships. Rather consistently, in children with gender dysphoria, anxiety and depression are common.

20.3.2 Teenagers and Adults

In teenagers and adults, symptoms may include:

Certainty that one’s true gender is not aligned with one’s body.

Disgust towards one’s own genitals.

Strong desire to get rid of one’s genitals and other characteristics of one’s biological sex.

It is very difficult to have or suppress these feelings, and as a result, people with gender dysphoria may present with anxiety, depression, engage in self-harm, and have suicidal thoughts.

In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5—American Psychiatric Association) details about the diagnostic criteria for gender dysphoria according to age (children, adolescents, and adults) are reported.

20.3.3 DSM 5

20.3.3.1 gender dysphoria criteria in adults.

A marked incongruence between one’s experienced/expressed gender and their assigned gender, lasting at least 6 months , as manifested by at least two of the following:

A marked incongruence between one’s experienced/expressed gender and primary and/or secondary sex characteristics (or in young adolescents, the anticipated secondary sex characteristics).

A strong desire to get rid of one’s primary and/or secondary sex characteristics because of a marked incongruence with one’s experienced/expressed gender (or in young adolescents, a desire to prevent the development of the anticipated secondary sex characteristics).

A strong desire for the primary and/or secondary sex characteristics of the other gender.

A strong desire to be of the other gender (or some alternative gender different from one’s assigned gender).

A strong desire to be treated as the other gender (or some alternative gender different from one’s assigned gender).

A strong conviction that one has the typical feelings and reactions of the other gender (or some alternative gender different from one’s assigned gender).

The condition must also be associated with clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning .

20.3.3.2 Gender Dysphoria Criteria in Children

A marked incongruence between one’s experienced/expressed gender and their assigned gender, lasting at least 6 months, as manifested by at least two of the following (one of which must be the first criterion):

A strong desire to be of the other gender or an insistence that one is the other gender (or some alternative gender different from one’s assigned gender).

In boys (assigned gender), a strong preference for cross-dressing or simulating female attire; or in girls (assigned gender), a strong preference for wearing only typical masculine clothing and a strong resistance to the wearing of typical feminine clothing.

A strong preference for cross-gender roles in make-believe play or fantasy play.

A strong preference for the toys, games, or activities stereotypically used or engaged in by the other gender.

A strong preference for playmates of the other gender.

In boys (assigned gender), a strong rejection of typically masculine toys, games, and activities and a strong avoidance of rough-and-tumble play; or in girls (assigned gender), a strong rejection of typically feminine toys, games, and activities.

A strong dislike of one’s sexual anatomy.

A strong desire for the physical sex characteristics that match one’s experienced gender.

The condition must be associated with clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

Specify whether a Sexual Development Disorder is present.

20.3.3.3 Gender Dysphoria Criteria in Adolescents

A marked incongruence between one’s experienced/expressed gender and their assigned gender, lasting at least 6 months, as manifested by at least two of the following:

After confirming the diagnosis, the person affected by Gender Dysphoria must be informed about all strategies of treatments, as well as about the associated risks and the irreversibility of some of them. The symptoms described above explain the need to provide adequate responses to specific needs, bearing in mind, as we are about to clarify, the multifactorial nature of the condition of gender incongruence and of Gender Dysphoria.

20.4 Causes: Etiological Theories

The causes of Gender Dysphoria are still unclear and both psychosocial and biological factors have been implicated. Currently, the most accepted hypothesis is that both factors contribute to its development [ 6 , 7 ]. Even if social factors, such as education, environment, and events of life, are of great importance in emergence of gender dysphoria, there is still no experimental evidence to support this theory.

Studies carried out on twin populations have shown that in monozygotic twins (i.e. generated by the same egg-cell and, therefore, with the same genetic makeup) the possibility of gender dysphoria occurring in both twins is higher than in heterozygous twins (generated by two distinct egg cells and therefore with 50% of the same genetic makeup). This suggests genetic factors are important in gender dysphoria. There are also numerous theories that consider the influence of sex hormones on the onset of gender dysphoria. As established by animal model experiments, the process of sexual differentiation is not limited to the development of the genitals, but it involves the structures of the central nervous system that regulate sexual behaviours. Since the differentiation of the genitals occurs in the first 2 months of intrauterine life, while that of the central nervous system begins in the second half of pregnancy and becomes manifest in adult life, it has been hypothesized that in subjects with gender dysphoria these two processes occur in a disharmonic way. In this regard, the importance of prenatal male sex hormones, particularly testosterones, in development of male sexual identity was suggested. Indeed, some studies highlighted that low levels of testosterone in male foetuses can be associated with an increased incidence of Gender Dysphoria. Furthermore, a reduced sensitivity to testosterone and, therefore, a defective functioning of this hormone has been evidenced in MtF people.

Other studies focused on brain area differences between male and female population and suggested that cerebral architecture of individuals with Gender Dysphoria resembles the one of individuals with the same gender identity rather than those with the same biological sex, thus suggesting that non-biological factors may play a predominant role in GD genesis. The diagnosis of Gender Dysphoria requires evaluation by a mental health expert (psychologist or psychiatrist). In general, a psychologist or a psychiatrist assesses whether Gender Dysphoria criteria are satisfied, with a focus on the way feelings and behaviours develop over time, and on the family and social context (if it is present and supportive). The team also assesses all condition for differential diagnosis, i.e. a non-compliance to stereotyped gender role behaviours, or a strong desire to belong to another gender than the one assigned and the degree and pervasiveness of activities and interests that vary with respect to gender for reasons inherent to the gender role rather than identity. GD must be distinguished from Transvestic Disorder, a cross-dressing behaviour that generates sexual arousal and causes suffering and/or impairment without questioning one’s primary gender. GD differs from Body Dysmorphism; the focus is on the alteration or removal of a specific part of the body as it is perceived as abnormal and not because it is representative of an assigned gender that is repudiated. It should also be distinguished from psychotic mental disorders, in which gender inconsistency can be underlying a delusional construct.

20.5 Treatment

Treatment of Gender Dysphoria aims to reduce, or remove, suffering based on teamwork of psychologists, psychiatrists, endocrinologists, and surgeons. There are standards of care proposed by the World Professional Association of Transgender Health (WPATH, [ 8 ]) and international guidelines [ 9 ] which health workers refer to. Some people with Gender Dysphoria decide to modify their body to make it more alike to how they feel, through a “ path of affirmation of gender ” that proceeds in successive phases and can include hormonal and/or surgical treatment. Treatments are not always necessary and the treatment process is not the same for all people. Indeed, the procedure is different according to real needs of the individual.

20.5.1 Treatment for Children and Adolescents

First line treatment of GD in children and adolescents is psychological intervention that must be provided by mental health experts (child psychologists and neuropsychiatrists), especially if specialized in issues related to developmental age. Psychological support allows to face current problems and provides help to reduce emotional suffering sometimes allowing for more drastic treatment avoidance.

Non-medical intervention is planned. So far, there is no consensus about the best intervention with children with GD, because the studies on the effectiveness of the different psychological approaches are poor and inconclusive. However, there is expert convergence on the opinion that the aim of a clinical intervention in children with GD must be to reduce discomfort and—if present—the associated emotional difficulties. The goal is the psychological well-being of the child. The better described approach is the so-called watchful waiting , which has the aim to encourage people with GD to explore their gender identity for it to develop in a natural and spontaneous way, while the individual maintains a neutral attitude towards any development outcome. The aim of the clinician (psychologist and/or psychotherapist) is to inform and to train the family about GD and to support it in making decisions following a careful evaluation of costs and benefits. Major associations dealing with developmental age or transgender health, such as the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, condemned all interventions aimed at identity gender modification as unethical or attempts at prevention of a future non-heterosexual orientation.

The approach to Gender Dysphoria in adolescence requires careful evaluation, with particular care in making differential diagnoses with other conditions in order to define individualized paths. For example, it is important to distinguish Gender Dysphoria from internalized homophobia that occurs in some adolescents who, failing to accept their homosexual orientation, may require a medical gender reassignment (GR). Depending on the cultural context, their belief system, or even stereotyped views of social arrangements, some homosexual adolescents may mistake their sexual orientation for gender identity, due to a history of borderline behaviours and cross-gender interests in childhood. First, differential diagnosis needs to exclude the “Transvestic Disorder”. Transvestism mostly characterizes male adolescents who occasionally wear female clothes without a connected sexual motivation; in fact, in adolescence this behavioural manifestation can represent a phase of experimentation. Transvestic Disorder in DSM-5 is among the Paraphilic Disorders and generally occurs in males of hetero- or bisexual orientation who experience sexual arousal in wearing women’s clothing associated with emotional distress. Transvestism disorder is distinguished from Gender Dysphoria because in the first case, gender identity is not in question. Gender Dysphoria must also be distinguished from “Body Dysmorphic Disorder” characterized by pervasive concern for presumed physical defects or imperfections, which are associated with repetitive behaviours in response to worries about such defects. In these cases, the modification or removal of a specific part of the body is required because it is perceived as abnormal or deformed, and not because it is attributable to the gender assigned at birth.

It is important to point out that Gender Dysphoria in adolescence is often accompanied by concomitant psychopathologies. Adolescents with Gender Dysphoria report higher levels of suicidal risk, depression, anxiety, social isolation, and bodily dissatisfaction.

The persistence of Gender Dysphoria in adolescence and the frequency of other associated psychopathologies—reactively to the condition of Gender Dysphoria—supports the importance of early intervention, including medical intervention. The guidelines of the Endocrine Society and the WPATH Standards of Care, together with the recommendations of the main national scientific societies, suggest to interrupt pubertal development with GnRH analogues (GnRHa) in adolescents with GD who meet specific criteria, i.e. an early onset of DG whose symptoms intensified during the early stages of puberty; the absence of psychosocial issues that may have interfered with diagnosis or treatment; a good understanding for the consequences of GR (Gender Reassignment) in one’s existence. In addition to psychological support, the administration of GnRHa is indicated to postpone puberty when Tanner stage 2 has been reached. GnRH analogues, which are prescribed by the endocrinologist, work by suppressing the production of sex hormones, therefore they block the physical changes induced by puberty. Therefore, they allow adolescents for a longer exploration of their gender identity and the mental health experts to observe adolescents’ gender identity while relieving the suffering that can come from contact with a body that develops in an unwanted direction. The effects of therapy with GnRH analogues are completely reversible: if the treatment is interrupted, pubertal development immediately begins in the direction of biological sex. If GD persists and if specific eligibility criteria are met, it is possible to start a first hormonal GR, from 16 years onwards with the intake of cross-sex hormones (CHT). Surgery is also allowed as an extreme strategy, but better after age of 18.

20.5.2 Treatment for Adults

Psychological support if necessary.

Feminizing or masculinizing hormone treatment (cross-sex therapy).

Sex reassignment surgery.