Loneliness Essay Example

Loneliness is a feeling that many people experience at one point or another. The impact of it on your life can vary greatly depending on the situation. This sample will explore the different types of loneliness, how to deal with them, and some tips for overcoming loneliness in general.

Essay Example On Loneliness

- Thesis Statement – Loneliness Essay

- Introduction – Loneliness Essay

- Main Body – Loneliness Essay

- Conclusion – Loneliness Essay

Thesis Statement – Loneliness Essay Loneliness is a consequence of being robbed of one’s freedom. It can be due to imprisonment, loss of liberty, or being discriminated against. Introduction – Loneliness Essay Loneliness is a social phenomenon that has been the subject of much research since time immemorial. Yet there still does not exist any solid explanation as to why some people are more prone to loneliness than others. This paper will seek to analyze this potentially debilitating condition from different perspectives. It will cover the relationship between loneliness and incarceration or loss of liberty; then it will proceed into discussing how emotions play a role in making us feel lonely; finally, it will look at how these feelings can affect our mental stability and overall well-being. Get Non-Plagiarized Custom Essay on Loneliness in USA Order Now Main Body – Loneliness Essay Loneliness is a universal feeling which has the ability to create its own culture within different societies. In detention facilities, there is a unique kind of loneliness that prevails between prisoners who are often divided into various categories and population groups. This has been described by Mandela as a consequence of being robbed of one’s freedom. The fact that it can be due to imprisonment, loss of liberty, or being discriminated against makes it even clearer why this isolation from other people occurs so frequently among detainees. In addition, when one spends time incarcerated in solitary confinement, they may become more experienced at coping with feelings of loneliness and despondency; however, these feelings do not tend to dissipate completely because living in an artificial environment cannot be compared with living out in the open. There is also a difference between feeling lonely and actually being alone; many individuals who do not feel social pressure, meaning that they are more than happy spending time on their own without any external stimulation, may still find themselves surrounded by people every day. Yet even this does not guarantee that one will escape feelings of isolation or rejection. Loneliness becomes an issue when it is chronic and experienced frequently, if only fleetingly. It can affect our psychological balance as well as our physical health because it usually initiates stress responses within the body which cause high blood pressure and prompt addiction to drugs or alcohol consumption. All these reasons may lead to decreased productivity and ultimately affect one’s ability to develop or maintain social connections. Buy Customized Essay on Loneliness At Cheapest Price Order Now Conclusion – Loneliness Essay Loneliness is a condition that we can’t always avoid, but it is something we should be aware of and try to limit. Thus, while the effects of loneliness on the individual may not be able to stimulate any significant changes in society, at least there will always remain one person more who understands what you are going through. Ultimately, it all comes down to empathy and sharing our own stories so that more people learn how to cope with this potentially dangerous emotional response. Hire USA Experts for Loneliness Essay Order Now

Need expert writers to help you with your essay writing? Get in touch!

This essay sample has given you some insights into the psychology of loneliness as well as suggestions for how to combat it in your own life.

Many of us find it hard to start writing an essay on general topics like loneliness. The free essay sample on loneliness is given here by the experts of Students Assignment Help to those who are assigned an essay on loneliness by professors. With the help of this sample, many ideas can easily be gathered by the college graduates to write their coursework essays.

Best essay helpers are giving to College students throughout the world through this sample. All types of essays like Argumentative Essays and persuasive essays can be written by following this example can be finished on time by the masters. If you still find it difficult to write a supreme quality essay on any topic then ask for the essay writing services from Students Assignment Help anytime.

Explore More Relevant Posts

- Nike Advertisement Analysis Essay Sample

- Mechanical Engineer Essay Example

- Reflective Essay on Teamwork

- Career Goals Essay Example

- Importance of Family Essay Example

- Causes of Teenage Depression Essay Sample

- Red Box Competitors Essay Sample

- Deontology Essay Example

- Biomedical Model of Health Essay Sample-Strengths and Weaknesses

- Effects Of Discrimination Essay Sample

- Meaning of Freedom Essay Example

- Women’s Rights Essay Sample

- Employment & Labor Law USA Essay Example

- Sonny’s Blues Essay Sample

- COVID 19 (Corona Virus) Essay Sample

- Why Do You Want To Be A Nurse Essay Example

- Family Planning Essay Sample

- Internet Boon or Bane Essay Example

- Does Access to Condoms Prevent Teen Pregnancy Essay Sample

- Child Abuse Essay Example

- Disadvantage of Corporate Social Responsibilities (CSR) Essay Sample

- Essay Sample On Zika Virus

- Wonder Woman Essay Sample

- Teenage Suicide Essay Sample

- Primary Socialization Essay Sample In USA

- Role Of Physics In Daily Life Essay Sample

- Are Law Enforcement Cameras An Invasion of Privacy Essay Sample

- Why Guns Should Not Be Banned

- Neolithic Revolution Essay Sample

- Home Schooling Essay Sample

- Cosmetology Essay Sample

- Sale Promotion Techniques Sample Essay

- How Democratic Was Andrew Jackson Essay Sample

- Baby Boomers Essay Sample

- Veterans Day Essay Sample

- Why Did Japan Attack Pearl Harbor Essay Sample

- Component Of Criminal Justice System In USA Essay Sample

- Self Introduction Essay Example

- Divorce Argumentative Essay Sample

- Bullying Essay Sample

Get Free Assignment Quote

Enter Discount Code If You Have, Else Leave Blank

Home — Essay Samples — Literature — Of Mice and Men — The Theme of Loneliness in Of Mice and Men

Analysis of Characters' Loneliness in of Mice and Men

- Categories: Loneliness Of Mice and Men

About this sample

Words: 1842 |

10 min read

Published: May 5, 2022

Words: 1842 | Pages: 4 | 10 min read

The essay delves into the poignant theme of loneliness depicted in John Steinbeck's novella "Of Mice and Men", notably through the characters of George Milton and Crooks. Loneliness, an emotionally desolate experience, is represented as a complex and potent emotion capable of inducing behavioral outbursts and altering characters' outlooks and behaviors. George, bound by obligation and genuine care for Lennie, experiences a unique solitude, being physically accompanied yet emotionally isolated due to Lennie’s mental condition. Crooks, isolated due to racial discrimination, shelters his vulnerability behind a wall of bitterness and emotional hardness, demonstrating how pervasive loneliness can twist personalities and moral compasses. The essay elucidates how such emotional solitude not only significantly influences the characters’ behaviors and mental states but also spotlights the harsh, discriminative societal backdrop, highlighting the varying, profound impacts loneliness imposes on individuals.

Table of contents

Introduction, loneliness in of mice and men, george milton, curley’s wife.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: Life Literature

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 953 words

1 pages / 396 words

1 pages / 615 words

2 pages / 887 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Of Mice and Men

John Steinbeck’s novel and poignant exploration of friendship, dreams, and the harsh realities of the Great Depression. One of the key literary devices that Steinbeck uses to convey the tragic and inevitable nature of the story [...]

John Steinbeck’s novel, Of Mice and Men, explores the theme of isolation and loneliness through the experiences of its characters. Set during the Great Depression in California, the novel follows the journey of two migrant [...]

Novella Of Mice and Men presents a complex and multifaceted character in the form of Curley's wife. Throughout the story, she is often portrayed as a villainous figure, but a closer analysis reveals a more nuanced [...]

Novella "Of Mice and Men" is a classic piece of literature that delves into the lives of migrant workers during the Great Depression. One of the pivotal characters in the story is Curley's wife, who is often misunderstood and [...]

Of Mice and Men is a classic novel taking place during the 1930s. The main characters are two migrant farmers, George and Lennie. They end up working at a farm out in California where they attempt to make enough cash to buy [...]

George and Lennie, the main characters of the novella "Of Mice and Men", stick with each other even through the hardships and obstacles. One factor that keeps them together is the fact that they are both lonely wanderers, in a [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Theme of Loneliness, Isolation, & Alienation in Literature with Examples

Humans are social creatures. Most of us enjoy communication and try to build relationships with others. It’s no wonder that the inability to be a part of society often leads to emotional turmoil.

Our specialists will write a custom essay specially for you!

World literature has numerous examples of characters who are disconnected from their loved ones or don’t fit into the social norms. Stories featuring themes of isolation and loneliness often describe a quest for happiness or explore the reasons behind these feelings.

In this article by Custom-Writing.org , we will:

- discuss isolation and loneliness in literary works;

- cite many excellent examples;

- provide relevant quotations.

🏝️ Isolation Theme in Literature

- 🏠 Theme of Loneliness

- 👽 Theme of Alienation

- Frankenstein

- The Metamorphosis

- Of Mice and Men

- ✍️ Essay Topics

🔍 References

Isolation is a state of being detached from other people, either physically or emotionally. It may have positive and negative connotations:

- In a positive sense, isolation can be a powerful source of creativity and independence.

- In negative terms , it can cause mental suffering and difficulties with interpersonal relationships.

Theme of Isolation and Loneliness: Difference

As you can see, isolation can be enjoyable in certain situations. That’s how it differs from loneliness : a negative state in which a person feels uncomfortable and emotionally down because of a lack of social interactions . In other words, isolated people are not necessarily lonely.

Isolation Theme Characteristics with Examples

Now, let’s examine isolation as a literary theme. It often appears in stories of different genres and has various shades of meaning. We’ll explain the different uses of this theme and provide examples from literature.

Just in 1 hour! We will write you a plagiarism-free paper in hardly more than 1 hour

Forced vs. Voluntary Isolation in Literature

Isolation can be voluntary or happen for external reasons beyond the person’s control. The main difference lies in the agent who imposes isolation on the person:

- If someone decides to be alone and enjoys this state of solitude, it’s voluntary isolation . The poetry of Emily Dickinson is a prominent example.

- Forced isolation often acts as punishment and leads to detrimental emotional consequences. This form of isolation doesn’t depend on the character’s will, such as in Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter .

Physical vs. Emotional Isolation in Literature

Aside from forced and voluntary, isolation can be physical or emotional:

- Isolation at the physical level makes the character unable to reach out to other people, such as Robinson Crusoe being stranded on an island.

- Emotional isolation is an inner state of separation from other people. It also involves unwillingness or inability to build quality relationships. A great example is Holden Caulfield from The Catcher in the Rye .

These two forms are often interlinked, like in A Rose for Emily . The story’s titular character is isolated from the others both physically and emotionally .

Symbols of Isolation in Literature

In literary works dedicated to emotional isolation, authors often use physical artifacts as symbols. For example, the moors in Wuthering Heights or the room in The Yellow Wallpaper are means of the characters’ physical isolation. They also symbolize a much deeper divide between the protagonists and the people around them.

🏠 Theme of Loneliness in Literature

Loneliness is often used as a theme in stories of people unable to build relationships with others. Their state of mind always comes with sadness and a low self-esteem. Naturally, it causes profound emotional suffering.

Receive a plagiarism-free paper tailored to your instructions. Cut 20% off your first order!

We will examine how the theme of loneliness functions in literature. But first, let’s see how it differs from its positive counterpart: solitude.

Solitude vs. Loneliness: The Difference

Loneliness theme: history & examples.

The modern concept of loneliness is relatively new. It first emerged in the 16 th century and has undergone many transformations since then.

- The first formal mention of loneliness appeared in George Milton’s Paradise Lost in the 17 th century. There are also many references to loneliness in Shakespeare’s works.

- Later on, after the Industrial Revolution , the theme got more popular. During that time, people started moving to large cities. As a result, they were losing bonds with their families and hometowns. Illustrative examples of that period are Gothic novels and the works of Charles Dickens .

- According to The New Yorker , the 20 th century witnessed a broad spread of loneliness due to the rise of Capitalism. Philosophers Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus explored existential loneliness, influencing numerous authors. The absurdist writings of Kafka and Beckett also played an essential role in reflecting the isolation felt by people in Capitalist societies. Sylvia Plath has masterfully explored mental health struggles related to this condition in The Bell Jar (you can learn more about it in our The Bell Jar analysis .)

👽 Theme of Alienation in Literature

Another facet of being alone that is often explored in literature is alienation . Let’s see how this concept differs from those we discussed previously.

Alienation vs. Loneliness: Difference

While loneliness is more about being on your own and lacking connection, alienation means involuntary estrangement and a lack of sympathy from society. In other words, alienated people don’t fit their community, thus lacking a sense of belonging.

Isolation vs. Alienation: The Difference

Theme of alienation vs. identity in literature.

There is a prominent connection between alienation and a loss of identity. It often results from a character’s self-search in a hostile society with alien ideas and values. These characters often differ from the dominant majority, so the community treats them negatively. Such is the case with Mrs. Dalloway from Woolf’s eponymous novel.

Get an originally-written paper according to your instructions!

Writers with unique, non-conforming identity are often alienated during their lifetime. Their distinct mindset sets them apart from their social circle. Naturally, it creates discomfort and relationship problems. These experiences are often reflected in their works, such as in James Joyce’s semi-autobiographical A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man .

Alienation in Modernism

Alienation as a theme is mainly associated with Modernism . It’s not surprising, considering that the 20 th century witnessed fundamental changes in people’s lifestyle. Capitalism and the Industrial Revolution couldn’t help eroding the quality of human bonding and the depth of relationships.

It’s also vital to mention that the two World Wars introduced even greater changes in human relationships. People got more locked up emotionally in order to withstand the war trauma and avoid further turmoil. Consequently, the theme of alienation and comradeship found reflection in the works of Ernest Hemingway , Erich Maria Remarque , Norman Mailer, and Rebecca West, among others.

📚 Books about Loneliness and Isolation: Quotes & Examples

Loneliness and isolation themes are featured prominently in many of the world’s greatest literary works. Here we’ll analyze several well-known examples: Frankenstein, Of Mice and Men, and The Metamorphosis.

Theme of Isolation & Alienation in Frankenstein

Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein is among the earliest depictions of loneliness in modern literature. It shows the depth of emotional suffering that alienation can impose.

Victor Frankenstein , a talented scientist, creates a monster from the human body parts. The monster becomes the loneliest creature in the world. Seeing that his master hates him and wouldn’t become his friend, he ruined everything Victor held dear. He was driven by revenge, trying to drive him into the same despair.

The novel contains many references to emotional and physical alienation. It also explores the distinction between voluntary and involuntary isolation:

- The monster is involuntarily driven into an emotionally devastating state of alienation.

- Victor imposes voluntary isolation on himself after witnessing the crimes of his creature.

To learn more about the representation of loneliness and isolation in the novel, check out our article on themes in Frankenstein .

Frankenstein Quotes about Isolation

Here are a couple of quotes from Frankenstein directly related to the theme of isolation and loneliness:

How slowly the time passes here, encompassed as I am by frost and snow…I have one want which I have never yet been able to satisfy and the absence of the object of which I now feel as a most severe evil. I have no friend. Frankenstein , Letter 2

In this quote, Walton expresses his loneliness and desire for company. He uses frost and snow as symbols to refer to his isolation. Perhaps a heart-warming relationship could melt the ice surrounding him.

I believed myself totally unfitted for the company of strangers. Frankenstein , Chapter 3

This quote is related to Victor’s inability to make friends and function as a regular member of society. He also misses his friends and relatives in Ingolstadt, which causes him further discomfort.

I, who had ever been surrounded by amiable companions, continually engaged in endeavouring to bestow mutual pleasure—I was now alone. Frankenstein , Chapter 3

In this quote, Victor shares his fear of loneliness. As a person who used to spend most of his time in social activity among people, Victor feared the solitude that awaited him in Ingolstadt.

Isolation & Alienation in The Metamorphosis

The Metamorphosis is an enigmatic masterpiece by Franz Kafka, telling a story of a young man Gregor. He is alienated at work and home by his demanding, disrespectful family. He lacks deep, rewarding relationships in his life. As a result, he feels profound loneliness.

Gregor’s family isolates him both as a human and an insect, refusing to recognize his personhood. Gregor’s stay in confinement is also a reflection of his broader alienation from society, resulting from his self-perception as a parasite. To learn more about it, feel free to read our article on themes in The Metamorphosis .

The Metamorphosis: Isolation Quotes

Let’s analyze several quotes from The Metamorphosis to see how Kafka approached the theme of isolation.

The upset of doing business is much worse than the actual business in the home office, and, besides, I’ve got the torture of traveling, worrying about changing trains, eating miserable food at all hours, constantly seeing new faces, no relationships that last or get more intimate. The Metamorphosis , Part 1

In this fragment, Gregor’s lifestyle is described with a couple of strokes. It shows that he lived an empty, superficial life without meaningful relationships.

Well, leaving out the fact that the doors were locked, should he really call for help? In spite of all his miseries, he could not repress a smile at this thought. The Metamorphosis , Part 1

This quote shows how Gregor feels isolated even before anyone else can see him as an insect. He knows that being different will inevitably affect his life and his relationships with his family. So, he prefers to confine himself to voluntary isolation instead of seeking help.

He thought back on his family with deep emotion and love. His conviction that he would have to disappear was, if possible, even firmer than his sister’s. The Metamorphosis , Part 3

This final paragraph of Kafka’s story reveals the human nature of Gregor. It also shows the depth of his suffering in isolation after turning into a vermin. He reconciles with his metamorphosis and agrees to disappear from this world. Eventually, he vanishes from his family’s troubled memories.

Theme of Loneliness in Of Mice and Men

Of Mice and Men is a touching novella by John Steinbeck examining the intricacies of laborers’ relationships on a ranch. It’s a snapshot of class and race relations that delves into the depths of human loneliness. Steinbeck shows how this feeling makes people mean, reckless, and cold.

Many characters in this story suffer from being alienated from the community:

- Crooks is ostracized because of his race, living in a separate shabby house as a misfit.

- George also suffers from forced alienation because he takes care of the mentally disabled Lennie.

- Curley’s wife is another character suffering from loneliness. This feeling drives her to despair. She seeks the warmth of human relationships in the hands of Lennie, which causes her accidental death.

Isolation Quotes: Of Mice and Men

Now, let’s analyze a couple of quotes from Of Mice and Men to see how the author approached the theme of loneliness.

Guys like us who work on ranches are the loneliest guys in the world, they ain’t got no family, they don’t belong no place. Of Mice and Men , Section 1

In this quote, Steinbeck describes several dimensions of isolation suffered by his characters:

- They are physically isolated , working on large farms where they may not meet a single person for weeks.

- They have no chances for social communication and relationship building, thus remaining emotionally isolated without a life partner.

- They can’t develop a sense of belonging to the place where they work; it’s another person’s property.

Candy looked for help from face to face. Of Mice and Men , Section 3

Candy’s loneliness on the ranch becomes highly pronounced during his conflict with Carlson. The reason is that he is an old man afraid of being “disposed of.” The episode is an in-depth look into a society that doesn’t cherish human relationships, focusing only on a person’s practical utility.

I never get to talk to nobody. I get awful lonely. Of Mice and Men , Chapter 5

This quote expresses the depth of Curley’s wife’s loneliness. She doesn’t have anyone with whom she would be able to talk, aside from her husband. Curley is also not an appropriate companion, as he treats his wife rudely and carelessly. As a result of her loneliness, she falls into deeper frustration.

✍️ Essay on Loneliness and Isolation: Topics & Ideas

If you’ve got a task to write an essay about loneliness and isolation, it’s vital to pick the right topic. You can explore how these feelings are covered in literature or focus on their real-life manifestations. Here are some excellent topic suggestions for your inspiration:

- Cross-national comparisons of people’s experience of loneliness and isolation.

- Social isolation , loneliness, and all-cause mortality among the elderly.

- Public health consequences of extended social isolation .

- Impact of social isolation on young people’s mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Connections between social isolation and depression.

- Interventions for reducing social isolation and loneliness among older people.

- Loneliness and social isolation among rural area residents.

- The effect of social distancing rules on perceived loneliness.

- How does social isolation affect older people’s functional status?

- Video calls as a measure for reducing social isolation.

- Isolation, loneliness, and otherness in Frankenstein .

- The unique combination of addiction and isolation in Frankenstein .

- Exploration of solitude in Hernan Diaz’ In the Distance .

- Artificial isolation and voluntary seclusion in Against Nature .

- Different layers of isolation in George Eliot’s Silas Marner .

- Celebration of self-imposed solitude in Emily Dickinson’s works.

- Buddhist aesthetics of solitude in Stephen Batchelor’s The Art of Solitude .

- Loneliness of childhood in Charles Dickens’s works.

- Moby-Dick : Loneliness in the struggle.

- Medieval literature about loneliness and social isolation.

Now you know everything about the themes of isolation, loneliness, and alienation in fiction and can correctly identify and interpret them. What is your favorite literary work focusing on any of these themes? Tell us in the comments!

❓ Themes of Loneliness and Isolation FAQs

Isolation is a popular theme in poetry. The speakers in such poems often reflect on their separation from others or being away from their loved ones. Metaphorically, isolation may mean hiding unshared emotions. The magnitude of the feeling can vary from light blues to depression.

In his masterpiece Of Mice and Men , John Steinbeck presents loneliness in many tragic ways. The most alienated characters in the book are Candy, Crooks, and Curley’s wife. Most of them were eventually destroyed by the negative consequences of their loneliness.

The Catcher in the Rye uses many symbols as manifestations of Holden’s loneliness. One prominent example is an image of his dead brother Allie. He’s the person Holden wants to bond with but can’t because he is gone. Holden also perceives other people as phony or corny, thus separating himself from his peers.

Beloved is a work about the deeply entrenched trauma of slavery that finds its manifestation in later generations. Characters of Beloved prefer self-isolation and alienation from others to avoid emotional pain.

In Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World , all people must conform to society’s rules to be accepted. Those who don’t fit in that established order and feel their individuality are erased from society.

- What Is Solitude?: Psychology Today

- Loneliness in Literature: Springer Link

- What Literature and Language Tell Us about the History of Loneliness: Scroll.in

- On Isolation and Literature: The Millions

- 10 Books About Loneliness: Publishers Weekly

- Alienation: Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Isolation and Revenge: Where Victor Frankenstein Went Wrong: University of Nebraska-Lincoln

- On Isolation: Gale

- Top 10 Books About Loneliness: The Guardian

- Emily Dickinson and the Creative “Solitude of Space:” Psyche

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to LinkedIn

- Share to email

Have you ever loved? Even if you haven’t, you’ve seen it in countless movies, heard about it in songs, and read about it in some of the greatest books in world literature. If you want to find out more about love as a literary theme, you came to the right...

Death is undoubtedly one of the most mysterious events in life. Literature is among the mediums that allow people to explore and gain knowledge of death—a topic that in everyday life is often seen as taboo. This article by Custom-Writing.org will: introduce the topic of death in literature and explain...

Wouldn’t it be great if people of all genders could enjoy equal rights? When reading stories from the past, we can realize how far we’ve made since the dawn of feminism. Books that deal with the theme of gender inspire us to keep fighting for equality. In this article, ourcustom-writing...

What makes a society see some categories of people as less than human? Throughout history, we can see how people divided themselves into groups and used violence to discriminate against each other. When groups of individuals are perceived as monstrous or demonic, it leads to dehumanization. Numerous literary masterpieces explore the meaning of monstrosity and show the dire consequences of dehumanization. This article by Custom-Writing.org will: explore...

Revenge provides relief. Characters in many literary stories believe in this idea. Convinced that they were wronged, they are in the constant pursuit of revenge. But is it really the only way for them to find peace? This article by Custom-Writing.org is going to answer this and other questions related...

Is money really the root of all evil? Many writers and poets have tried to answer this question. Unsurprisingly, the theme of money is very prevalent in literature. It’s also connected to other concepts, such as greed, power, love, and corruption. In this article, our custom writing team will: explore...

Have you ever asked yourself why some books are so compelling that you keep thinking about them even after you have finished reading? Well, of course, it can be because of a unique plotline or complex characters. However, most of the time, it is the theme that compels you. A...

The American Dream theme encompasses crucial values, such as freedom, democracy, equal rights, and personal happiness. The concept’s definition varies from person to person. Yet, books by American authors can help us grasp it better. Many agree that American literature is so distinct from English literature because the concept of...

A fallen leaf, a raven, the color black… What connects all these images? That’s right: they can all symbolize death—one of literature’s most terrifying and mysterious concepts. It has been immensely popular throughout the ages, and it still fascinates readers. Numerous symbols are used to describe it, and if you...

The most ancient text preserved to our days raises more questions than there are answers. When was The Iliad written? What was the purpose of the epic poem? What is the subject of The Iliad? The Iliad Study Guide prepared by Custom-Writing.org experts explores the depths of the historical context...

The epic poem ends in a nostalgic and mournful way. The last book is about a father who lost his son and wishes to make an honorable funeral as the last thing he could give him. The book symbolizes the end of any war when sorrow replaces anger. Book 24,...

The main values glorified in The Iliad and The Odyssey are honor, courage, and eloquence. These three qualities were held as the best characteristics a person could have. Besides, they contributed to the heroic code and made up the Homeric character of a warrior. The Odyssey also promotes hospitality, although...

- Human Editing

- Free AI Essay Writer

- AI Outline Generator

- AI Paragraph Generator

- Paragraph Expander

- Essay Expander

- Literature Review Generator

- Research Paper Generator

- Thesis Generator

- Paraphrasing tool

- AI Rewording Tool

- AI Sentence Rewriter

- AI Rephraser

- AI Paragraph Rewriter

- Summarizing Tool

- AI Content Shortener

- Plagiarism Checker

- AI Detector

- AI Essay Checker

- Citation Generator

- Reference Finder

- Book Citation Generator

- Legal Citation Generator

- Journal Citation Generator

- Reference Citation Generator

- Scientific Citation Generator

- Source Citation Generator

- Website Citation Generator

- URL Citation Generator

- Proofreading Service

- Editing Service

- AI Writing Guides

- AI Detection Guides

- Citation Guides

- Grammar Guides

- Paraphrasing Guides

- Plagiarism Guides

- Summary Writing Guides

- STEM Guides

- Humanities Guides

- Language Learning Guides

- Coding Guides

- Top Lists and Recommendations

- AI Detectors

- AI Writing Services

- Coding Homework Help

- Citation Generators

- Editing Websites

- Essay Writing Websites

- Language Learning Websites

- Math Solvers

- Paraphrasers

- Plagiarism Checkers

- Reference Finders

- Spell Checkers

- Summarizers

- Tutoring Websites

Most Popular

13 days ago

How To Summarize A Research Article

How to cite a blog, why congress cares about media literacy and you should too, how educators can reinvent teaching and learning with ai, plagiarism vs copyright, loneliness and its effects essay sample, example.

Everyone probably knows the feeling of isolation, when the entire world seems to be behind a glass wall: one can see people on the other side, interact and talk to them, live a more or less normal life—but feel alone and forgotten somewhere deep inside. In a world where communication is the new god, where extroverted behaviors are deemed healthy and normal, and where everything calls a person to belong to a certain group, being and feeling alone often seems wrong. There is nothing bad in needing solitude; from time to time, all of us need to spend some time on our own. However, solitude is rather a voluntary choice; when this condition becomes chronic and undesired, when a person feels the impossibility of establishing contact with others, this is already something many people around the world fear strongly: this is loneliness.

What exactly is loneliness? A more narrow definition suggests that loneliness is the condition when a person is not surrounded by other people, spends most of his or her time alone, and maintains little-to-no social contact. However, anyone who had at least once experienced the condition of loneliness knows that it is possible to be surrounded by friends or family, stay in the thick of things, and still feel isolated. In fact, the statistics shows about 60% of people who feel lonely are married, which is a good illustration of the thesis that loneliness does not depend on the environment, that the amount and variety of social connections and\or relationships do not necessarily save us from it. (Psychology Today).

A better understanding of loneliness can be achieved from the analysis of the needs and desires standing behind it—or, to be precise, the impossibility to satisfy these needs. According to Baumeister and Leary, every person has a basic need to belong to a certain group; this need is as significant and natural as the need to eat, to sleep, or to feel safe. However, simply belonging on its own does not satisfy the need: it is important that a person can form strong, close, and stable interpersonal relationships, and maintain them: only in this case the sense of belonging will be full. This makes sense even from the evolutionary point of view: staying together with other people was a guarantee of physical survival in ancient times. Continuing the parallel between emotional and physical (or basic) needs, our bodies are often wiser than our minds: when there is a lack or a surplus of something, our bodies react appropriately. Sensations (such as hunger, heat, and so on) and emotions are the signals our bodies send to our minds in order to alert them about these shortages and surpluses. Respectively, loneliness is an emotion which signals that the need of belonging is not satisfied, or that we are not getting the relationships (or the quality of already existing relationships) that we want (Web of Loneliness). This often seems irrational: for example, a person can have a lot of friends and see them often, he or she can be married and have children, have no problems with colleagues at work—everything is seemingly fine, but the sense of loneliness is still there, and it is important to understand why it is present, what is lacking.

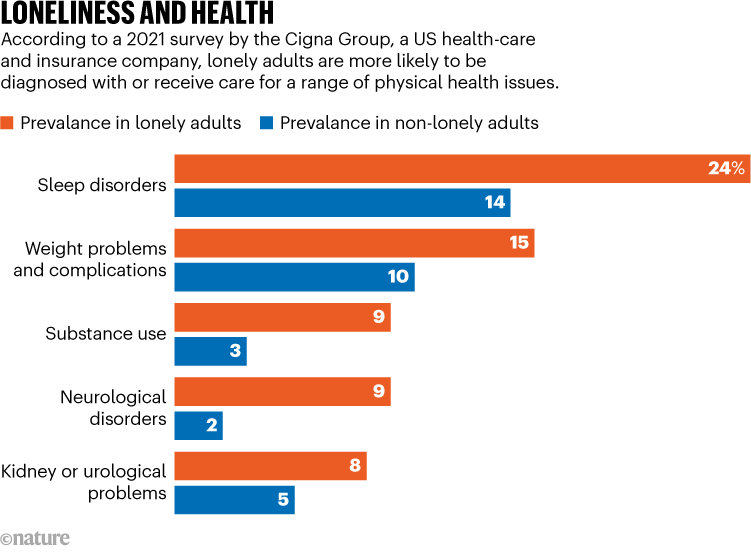

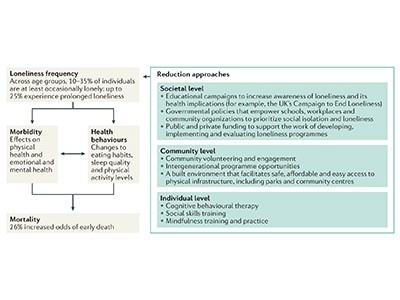

Being in strong and close relationships affects our mental health beneficially; being alone for a long period of time can lead to a number of negative consequences, both on mental and physiological levels. In particular, loneliness can lead to depression (which is a dangerous mental condition on its own), a feeling of hopelessness, low self-esteem, an impaired ability for social interactions and work, suicidal tendencies, poor sleep, the sense of defeat, and helplessness. These sensations form a vicious circle—nurturing each other, they aggravate the situation of a lonely person, preventing him or her from getting out of this span on his or her own. Not only the emotional sphere, but also bodily functions are affected by loneliness. Studies show that lonely people face cardiovascular diseases more frequently than those enjoying strong and stable relationships with other people; other effects include the loss of weight, hormonal imbalances, the inhibition of the immune system, low resistance to infections and inflammations, dementia (in old age), and the degradation of bones and muscle tissue (The Doctor’s Tablet). All this does not mean that a person starts experiencing all these negative effects every time he or she feels lonely; however, these effects accumulate during prolonged isolation, “chronic” loneliness; therefore, it is important to not try to deal with this condition on one’s own, and seek professional help.

In fact, there are many effective ways to treat loneliness. Many people think that it is enough to increase the amount of social contacts, go out more often, and loneliness will be dealt with. However, loneliness is more about a person’s ability to form close relationships and bond with others, rather than about how often one is exposed to other people. Similar to other negative mental conditions, the first important step is to let yourself feel loneliness, and admit that you would like to live differently than you do. People often try to overpower their loneliness; they either tend to not treat it as something significant, considering it to be a weakness, or even deny that they are feeling lonely. When the problem is accepted and defined, it is recommended to start attending local psychotherapy sessions; cognitive-behavioral therapy usually provides solid results in treating loneliness, although other psychology schools, such as gestalt therapy can also be efficient, try finding what suits you the best. If you cannot afford attending a psychotherapist, consider utilizing a variety of relaxation and stress-relief techniques such as meditation, muscle relaxation training, guided mental imagery, or comforting self-talk. Pet therapy can be helpful as well; in fact, many people intuitively feel the need to have a living being nearby, whom they would be able to take care of, so owning a dog, cat, bird, or even a lizard can be a nice way to cope with loneliness (Psychologist Anywhere, Anytime). In many western countries, especially in the United States, it is extremely popular to prescribe medicine in order to deal with mental conditions; however, it is important to remember that loneliness is rather an emotional condition, not a biochemical one, so if you decide to take pills, it might help you inhibit unpleasant and painful feelings, but it will not solve your problem. Pills might be helpful if you are already suffering from depression as a result of loneliness—and even in this case, you should consider going to psychotherapy sessions.

Loneliness is not the same as solitude. The latter is a voluntary act of isolation from a society in order to refresh oneself, sort out one’s thoughts, and take a break from intense social interactions. Loneliness, in its turn, is a chronic and undesired condition when a person is unable (due to a number of reasons) to establish and maintain contact and close, stable relationships with surrounding people. Prolonged loneliness can be dangerous, since it can cause a variety of emotional and physiological problems. However, the good news is that loneliness can be treated effectively, mostly with the help of a professional psychotherapist.

Writing an expository essay is an interesting task. So, don’t skip on the opportunity to take up this challenge. However, be prepared to do some research and analysis of the chosen topic. In case you face some struggles while writing, don’t hesitate to check out assignment writing services . There, you can find assistance that will set you on the right path with your expository essay.

Works Cited

“What is Loneliness?” Web of Loneliness. N.p., n.d. Web. 03 July 2017. <http://www.webofloneliness.com/what-is-loneliness.html>

Winch, Guy. “10 Surprising Facts About Loneliness.” Psychology Today. Sussex Publishers, 21 Oct. 2014. Web. 03 July 2017. <https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/the-squeaky-wheel/201410/10-surprising-facts-about-loneliness>

Kennedy, Gary J. “How Loneliness Affects the Mind and Body.” The Doctor’s Tablet. N.p., 07 May 2015. Web. 03 July 2017. <http://blogs.einstein.yu.edu/how-loneliness-affects-the-mind-and-body/>

“Loneliness and the Fear of Being Alone.” Psychologist Anywhere, Anytime. N.p., n.d. Web. 03 July 2017. <http://www.psychologistanywhereanytime.com/relationships_psychologist/psychologist_loneliness.htm>

Follow us on Reddit for more insights and updates.

Comments (0)

Welcome to A*Help comments!

We’re all about debate and discussion at A*Help.

We value the diverse opinions of users, so you may find points of view that you don’t agree with. And that’s cool. However, there are certain things we’re not OK with: attempts to manipulate our data in any way, for example, or the posting of discriminative, offensive, hateful, or disparaging material.

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

More from Expository Essay Examples and Samples

Nov 23 2023

Why Is Of Mice And Men Banned

Nov 07 2023

Pride and Prejudice Themes

May 10 2023

Remote Collaboration and Evidence Based Care Essay Sample, Example

Related writing guides, writing an expository essay.

Remember Me

What is your profession ? Student Teacher Writer Other

Forgotten Password?

Username or Email

- Open access

- Published: 06 December 2020

Experiences of loneliness: a study protocol for a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative literature

- Phoebe E. McKenna-Plumley ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5627-5730 1 ,

- Jenny M. Groarke 1 ,

- Rhiannon N. Turner 1 &

- Keming Yang 2

Systematic Reviews volume 9 , Article number: 284 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

5337 Accesses

5 Citations

7 Altmetric

Metrics details

Loneliness is a highly prevalent, harmful, and aversive experience which is fundamentally subjective: social isolation alone cannot account for loneliness, and people can experience loneliness even with ample social connections. A number of studies have qualitatively explored experiences of loneliness; however, the research lacks a comprehensive overview of these experiences. We present a protocol for a study that will, for the first time, systematically review and synthesise the qualitative literature on experiences of loneliness in people of all ages from the general, non-clinical population. The aim is to offer a fine-grained look at experiences of loneliness across the lifespan.

We will search multiple electronic databases from their inception onwards: PsycINFO, MEDLINE, Scopus, Child Development & Adolescent Studies, Sociological Abstracts, International Bibliography of the Social Sciences, CINAHL, and the Education Resource Information Center. Sources of grey literature will also be searched. We will include empirical studies published in English including any qualitative study design (e.g. interview, focus group). Studies should focus on individuals from non-clinical populations of any age who describe experiences of loneliness. All citations, abstracts, and full-text articles will be screened by one author with a second author ensuring consistency regarding inclusion. Potential conflicts will be resolved through discussion. Thematic synthesis will be used to synthesise this literature, and study quality will be assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research. The planned review will be reported according to the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) statement.

The growing body of research on loneliness predictors, outcomes, and interventions must be grounded in an understanding of the lived experience of loneliness. This systematic review and thematic synthesis will clarify how loneliness is subjectively experienced across the lifespan in the general population. This will allow for a more holistic understanding of the lived experience of loneliness which can inform clinicians, researchers, and policymakers working in this important area.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42020178105 .

Peer Review reports

Loneliness has become the focus of a wealth of research in recent years. This attention is well placed given that loneliness has been designated as a significant public health issue in the UK [ 1 ] and is associated with poor physical and mental health outcomes [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ] and an increase in risk of death similar to that of smoking [ 6 ]. In light of this, it is concerning that recent research has found that loneliness is highly prevalent across age groups, with young people (under 25 years) and older adults (over 65 years) indicating the highest levels [ 7 , 8 ].

Whilst an ever-increasing body of research is situating loneliness at its centre, there is relatively little work which focuses on the lived experience of loneliness: how loneliness feels and what makes up experiences of loneliness. Phenomena that might appear to describe loneliness, such as social isolation, are distinct from the actual experience of it. Whilst loneliness is generally characterised as the distress one experiences when they perceive their social connections to be lacking in number or quality, social isolation is the objective limitation or absence of connections [ 9 ]. Social isolation does not necessarily beget loneliness, and indeed, Hawkley and Cacioppo [ 3 ] remark on how humans can perceive meaningful social relationships where none objectifiably exist, such as with God, or where reciprocity is not possible, such as with fictional characters. Whilst associations between aloneness and loneliness have been richly demonstrated [ 10 , 11 ], other research has found moderate and low correlations between social isolation and loneliness [ 12 , 13 ]. These findings underline the need to better understand what makes up the subjective experience of loneliness, given that it is clearly not sufficiently captured by the objective experience of being alone. Given the subjective nature of the phenomenon, qualitative methods are particularly suited to research into experiences of loneliness, as they can aim to capture the idiosyncrasies of these experiences.

A number of qualitative studies of loneliness experiences have been carried out. In perhaps the largest study of its type, Rokach [ 14 ] analysed written accounts of 526 adults’ loneliest experience, specifically asking about their thoughts, feelings, and coping strategies. This generated a model with four major elements (self-alienation, interpersonal isolation, distressed reactions, and agony) and twenty-three components such as emptiness, numbness, and missing a specific person or relationship. Although this study offered impressive scale, the vast majority of participants were between 19 and 45 years old, and as a result, the model may underestimate factors experienced across the lifespan. The findings might be usefully integrated with more recent research which qualitatively explores loneliness in other age groups (e.g. [ 15 ]). Harmonising this research by looking closely at how people describe their experiences of loneliness and working from the bottom-up to create a fine-grained view of what makes up these experiences will provide a more holistic understanding of loneliness and how it might best be defined and ameliorated.

There are a number of available definitions of loneliness offered by researchers. The widely accepted description from Perlman and Peplau [ 16 ], for example, states that loneliness is an unpleasant and distressing subjective phenomenon arising when one’s desired level of social relations differs from their actual level. However, research lacks an overarching subjective perspective, by which we mean a description of loneliness which is grounded in accounts of people’s lived experiences. This is a significant gap in the field given that loneliness is, by its nature, a subjective experience. Unlike objective phenomena like blood pressure or age, loneliness can only be definitively measured by asking a person whether they feel lonely. Weiss [ 17 ] argued that whilst available definitions of loneliness may be helpful, they do not sufficiently reflect the real phenomenon of loneliness because they define it in terms of its potential causes rather than the actual experience of being lonely. As such, studies which begin from definitions of loneliness like these may obscure the ways in which it is actually experienced and fail to capture the components and idiosyncrasies of these experiences.

A recent systematic review report [ 18 ] has explored the conceptualisations of loneliness employed in qualitative research, finding that loneliness tended to be defined as social, emotional, or existential types. However, the review covered only studies of adults (16 years and up), including heterogenous clinical populations (e.g. people receiving cancer treatment, people living with specific mental health conditions, and people on long-term sick leave), and placed central importance on the concepts, models, theories, and frameworks of loneliness utilised in research. Studies which did not employ an identified concept, model, framework, or theory of loneliness were excluded. Moreover, rather than synthesising how people describe their loneliness, the authors aimed to assess how research conceptualises loneliness across the adult life course. This leaves a gap with respect to how research participants specifically describe their lived experiences of loneliness, rather than how researchers might conceptualise it. Achterberg and colleagues [ 19 ] recently conducted a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies on experiences of loneliness in young people with depression. As the findings are specific to experiences in this population, they may not reflect those of wider age groups or individuals who do not have depression. Kitzmüller and colleagues [ 20 ] used meta-ethnography to synthesise studies regarding experiences and ways of dealing with loneliness in older adults (60 years and older). However, they synthesised only articles from health care disciplines published in scientific journals from 2001 to 2016 and included studies on clinical populations, such as older women with multiple chronic conditions. Moreover, there has been an increase in research output regarding loneliness in recent years, and relevant studies may have been published since this review was conducted (e.g. [ 15 ]). To the authors’ knowledge, the systematic review report on conceptual frameworks used in loneliness research [ 18 ], the meta-synthesis of loneliness in young people with depression [ 19 ], and the meta-ethnography of older adults’ loneliness [ 20 ] are the only such systematic reviews of qualitative literature regarding experiences of loneliness to date. The current systematic review will instead take a bottom-up approach which focuses on non-clinical populations of all ages to synthesise findings on participants’ experiences of loneliness, rather than the conceptualisations that might be imposed by study authors. This will fill a gap in the literature by synthesising the qualitative evidence focusing on experiences of loneliness across the lifespan. This inductive synthesis of the available subjective descriptions of loneliness will offer a nuanced view of loneliness experiences. It is imperative for research and practice that we deepen the current understanding of these experiences to inform how we approach describing, researching, and attempting to ameliorate loneliness.

The proposed research aims to offer a holistic view of the experience of loneliness across the lifespan through a systematic review and thematic synthesis of the qualitative literature focusing on these experiences. To address this aim, there is one central research question: How do people describe their experiences of loneliness?

This research question concerns aspects of loneliness which participants discuss when describing their lived experiences. Whilst we expect that this would concern emotional, social, and cognitive components of the experience, we understand that these findings may also come to reflect perceived causes or effects of loneliness.

This review will also consider the age groups that have been studied and how experiences of loneliness might vary across the different age groups examined in this literature. Loneliness research is often weighted towards investigations of older adults, despite the fact that the prevalence of loneliness is high across the lifespan; recent UK research found a prevalence of 40% in 16- to 24-year-olds and 27% in people over 75 [ 7 ]. This review will also shed light on the age groups that have been included in qualitative research on loneliness experiences. In doing so, this research may identify age groups which have been understudied and may be underrepresented in this field of research, potentially pointing to life stages where experiences of loneliness might be usefully explored in more detail in the future.

Furthermore, given the relatively small number of qualitative studies into the experience of loneliness compared with quantitative research in this area, this review will also consider the reasons that study authors may offer for the relative shortage of qualitative work. This is an important point given that the review will inherently be constrained by the number of studies that exist and the focus that has primarily been given to quantitative loneliness research thus far.

Protocol registration and reporting

The review protocol has been registered within the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) database from the University of York (registration number: CRD42020178105). This review protocol is being reported in accordance with the reporting guidance provided in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols (PRISMA-P) statement [ 21 ] (see checklist in Additional file 1 ). The proposed systematic review will be reported in accordance with the reporting guidance provided in the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) statement [ 22 ]. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [ 23 ] will inform the process of completing and reporting this planned review.

Eligibility criteria

Due to its suitability for qualitative evidence synthesis, the SPIDER tool [ 24 ] was used to assist in defining the research question and eligibility criteria in line with the following criteria: Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type (see Table 1 for details of these criteria). The exclusion criteria are as follows:

Studies not meeting the inclusion criteria described in Table 1

Studies not published in English

Studies with no qualitative component

Studies of clinical populations

Studies which report solely on objective phenomena such as social isolation rather than the subjectively perceived experience of loneliness

Studies in which the primary focus or one of the primary focuses is not experiences of loneliness

Papers will be deemed to focus sufficiently on experiences of loneliness if studying these experiences is a key aspect of the work rather than simply a part of the output. Accordingly, studies will only be included if authors state a relevant aim, objective, or research question related to investigating experiences of loneliness (i.e. to study experiences of loneliness) or if loneliness experiences are clearly explored and described (e.g. relevant questions are present in an appended interview guide). At the title and abstract screening stage, at least one relevant sentence or information that indicates likely relevance must be present for inclusion. The decision to exclude articles which do not primarily or equally focus on these experiences was made in order to gather meaningful data about loneliness experiences specifically and to capture experiences identified as loneliness by participants as much as possible, rather than related phenomena which may be grouped and labelled retrospectively as loneliness by researchers.

Information sources and search strategy

The primary source of literature will be a structured search of multiple electronic databases (from inception onwards): PsycINFO, MEDLINE, Scopus, Child Development & Adolescent Studies, Sociological Abstracts, International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS), CINAHL, and the Education Resource Information Center (ERIC). The secondary source of potentially relevant material will be a search of the grey or difficult-to-locate literature using Google Scholar. In line with the guidance from Haddaway and colleagues [ 25 ] on using Google Scholar for systematic review, a title-only search using the same search terms will be conducted and the first 1000 results will be screened for eligibility. These searches will be supplemented with hand-searching in reference lists, such that the titles of all articles cited within eligible studies will be checked. When eligibility is unclear from the title, abstracts and full-texts will be checked until eligibility or ineligibility can be ascertained. This process will be repeated with any articles that are found to be eligible at this stage until no new eligible articles are found. Systematic reviews on similar topics will also be searched for potentially eligible studies. Grey literature will be located through searches of Google Scholar, opengrey.eu, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, and websites of specific loneliness organisations such as the Campaign to End Loneliness, managed in collaboration with an information specialist. Efforts will be made to contact authors of completed, ongoing, and in-press studies for information regarding additional studies or relevant material.

The search strategy for our primary database (MEDLINE) was developed in collaboration with an information specialist. In collaboration with a specialist, the strategy will be translated for all of the databases. The search strategy has been peer reviewed using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) checklist [ 26 ]. Strategies will utilise keywords for loneliness and qualitative studies. A draft search strategy for MEDLINE is provided in Additional file 2 . Qualitative search terms were supplemented with relevant and useful subject headings and free-text terms from the Pearl Harvesting Search Framework synonym ring for qualitative research [ 27 ]. The inclusion of search terms related to social isolation specifically and related terms (e.g. “social engagement”) was considered and tested extensively through scoping searches and discussion with an information specialist. Adding these terms (and others such as “Patient Isolation” and “Quarantine”) did not appear to add unique papers that would be included above and beyond subject heading and free-text searching for “Loneliness”. Given the aim to include studies focused on experiences of loneliness specifically, this search strategy was deemed most appropriate. A similar strategy has been employed in other recent systematic review work focusing on loneliness (e.g. [ 28 , 29 ]). Moreover, test searches employing the search strategy retrieved all of seven informally identified likely eligible articles indexed in Scopus, indicating good sensitivity of the strategy. A free-text search to capture “perceived social isolation” was included as this specific term is used by some authors as a direct synonym for loneliness. The completed PRESS checklist is provided in Additional file 3 .

Data collection and analysis

Study selection.

Firstly, the main review author (PMP) will perform the database search and hand-searching and will screen all titles to remove studies which are clearly not relevant. PMP will also undertake abstract screening to exclude any which are found to be irrelevant or inapplicable to the inclusion criteria. A second author (JG) will independently screen 50% of the titles and abstracts. Finally, full-text versions of the remaining articles will be read by PMP to assess whether they are suitable for inclusion in the final review. JG will independently review 50% of these full texts. In cases of disagreement, the two reviewers will discuss the study to reach a decision about inclusion or exclusion. In case agreement cannot be reached after discussion between the two reviewers, a third reviewer will be invited to reconcile their disagreement and make a final decision. The reason for the exclusion at the full-text stage will be recorded. After this screening process, the remaining articles will be included in the review following data extraction, quality appraisal, and analysis. The PRISMA statement will be followed to create a flowchart of the number of studies included and excluded at each stage of this process.

Data management

The articles to be screened will be managed in EndNoteX9, with subsequent EndNote databases used to manage each stage of the screening process.

Data extraction

Data will be extracted from the studies by PMP using a purpose-designed and piloted Microsoft Excel form. Information on author, publication year, geographic location of study, methodological approach, method, population, participant demographics, and main findings will be extracted to understand the basis of each study. JG will check this extracted data for accuracy.

For the thematic synthesis, in line with Thomas and Harden [ 30 ], all text labelled as “results” or “findings” will be extracted and entered into the NVivo software for analysis. This will be done because many factors, including varied reporting styles and misrepresentation of data as findings, can make it difficult to identify the findings in qualitative research [ 31 ]; accordingly, a wide-ranging approach will be used to capture as much relevant data as possible from each included article. The aim is to extract all data in which experiences of loneliness are described.

Quality appraisal

Quality of the included articles will be assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research [ 32 ]. This quality will be considered during the development of the data synthesis. Different authors hold different viewpoints about inclusion versus exclusion of low-quality studies. However, given that they may still add important, authentic accounts of phenomena that have simply been reported inadequately [ 33 ], it is common to include lower-quality studies and consider quality during the synthesis process rather than excluding on the basis of it. Accordingly, this approach will be used in the present research.

Data synthesis

There are various accepted approaches to reviewing and synthesising qualitative research, including meta-ethnography [ 34 ], meta-synthesis [ 35 ], and narrative synthesis [ 36 ]. The current systematic review will utilise thematic synthesis as a methodology to create an overarching understanding of the experiences of loneliness described across studies. In thematic synthesis, descriptive themes which remain close to the primary studies are developed. Next, a new stage of analytical theme development is undertaken wherein the reviewer “goes beyond” the interpretations of the primary studies and develops higher-order constructs or explanations based on these descriptive themes [ 30 ]. The process of thematic synthesis for reviewing is similar to that of grounded theory for primary data, in that a translation and interpretative account of the phenomena of interest is produced. Thematic synthesis has been used to synthesise research on the experience of fatigue in neurological patients with multiple sclerosis [ 37 ], children’s experiences of living with juvenile idiopathic arthritis [ 38 ], and parents’ experiences of parenting a child with chronic illness [ 39 ]. This use of thematic synthesis to consider subjective experiences (rather than, for example, attitudes or motivations) melds well with the present research, which also sets its focus on a subjective experience.

As well as its successful application in similar systematic reviews, thematic synthesis was selected based on its appropriateness to the research question, time frame, resources, expertise, purpose, and potential type of data in line with the RETREAT framework for selecting an approach to qualitative evidence synthesis [ 40 ]. The RETREAT framework considers thematic synthesis to be appropriate for relatively rapid approaches which can be sustained by researchers with primary qualitative experience, unlike approaches such as meta-ethnography in which a researcher with specific familiarity with the method is needed. This is appropriate to the project time frame and background of this research team. The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual [ 41 ] also notes that thematic synthesis is useful when considering shared elements across studies which are otherwise heterogenous, which is likely to be the case in this review given that the common factor (experiences of loneliness) may be present across studies with otherwise diverse populations and methodologies.

Guidance from Thomas and Harden [ 30 ] will be followed to synthesise the data. Firstly, the extracted text will be inductively coded line-by-line according to content and meaning. This inductive creation of codes should allow the content and meaning of each sentence to be captured. Multiple codes may be applied to the same sentence, and codes may be “free” or structured in a tree formation at this stage. Before moving forward, all text referred to by each code will be rechecked to ensure consistency in what is considered a single code or whether more levels of coding are required.

After this stage, similarities and differences between the codes will be examined, and they will begin to be organised into a hierarchy of groups of codes. New codes will be applied to these groups to describe their overall meaning. This will create a tree structure of descriptive themes which should not deviate largely from the original study findings; rather, findings will have been integrated into an organised whole. At this stage, the synthesis should remain close to the findings of the included studies.

At the final stage of analysis, higher-order analytical themes may be inferred from the descriptive themes which will offer a theoretical structure for experiences of loneliness. This inferential process will be carried out through collaboration between the research team (primarily PMP and JG).

Sensitivity analysis

After the synthesis is complete, a sensitivity analysis will be undertaken in which any low-quality studies (as identified through the JBI checklist) are excluded from the analysis to assess whether the synthesis is altered when these studies are removed, in terms of any themes being lost entirely or becoming less rich or thick [ 42 ]. Sensitivity analysis will also be used to assess whether any age group is entirely responsible for a given theme. In this way, the robustness of the synthesis can be appraised and the individual findings can remain grounded in their context whilst also extending into a broader understanding of the experiences of loneliness.

Risk of bias in individual studies

Risk of bias in individual studies will be taken into account through utilisation of the JBI checklist, which includes ten questions to assess whether a study is adequately conceptualised and reported [ 32 ]. PMP will use the checklist to assess the quality of each study. Whilst all eligible studies will be included in the synthesis (as described in the “Quality appraisal” section), any lower-quality studies will be excluded during post-synthesis sensitivity analysis in order to assess whether their inclusion has affected the synthesis in any way as suggested by Carroll and Booth [ 43 ].

Confidence in cumulative evidence

The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation – Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research (GRADE-CERQual) approach [ 44 , 45 ] will be used to assess how much confidence can be placed in the findings of this qualitative evidence synthesis. This will allow a transparent, systematic appraisal of confidence in the findings for researchers, clinicians, and other decision-makers who may utilise the evidence from the planned systematic review. GRADE-CERQual involves assessment in four domains: (1) methodological limitations, (2) coherence, (3) adequacy of data, and (4) relevance. There is also an overall rating of confidence: high, moderate, low, or very low. These findings will be displayed in a Summary of Qualitative Findings table including a summary of each finding, confidence in that finding, and an explanation for the rating. Assessments for each finding will be made through discussion between PMP and JG.

The proposed systematic review will contribute to our knowledge of loneliness by clarifying how it is subjectively experienced across the lifespan. Synthesising the qualitative literature focusing on experiences of loneliness in the general population will offer a fine-grained, subjectively derived understanding of the components of this phenomenon which closely reflects the original descriptions provided by those who have experienced it. By including non-clinical populations of all ages, this research will provide an essential view of loneliness experiences across different life stages. This can be used to inform future research into correlates, consequences, and interventions for loneliness. The use of thematic synthesis will enable us to remain close to the data, offering an account which might also be useful for policy and practice in this area.

There are a number of limitations to the planned research. Primarily, this review will be unable to capture aspects of loneliness experiences which have not been described in the qualitative literature, for example, due to the sensitivity of the topic, given that loneliness can be stigmatising, or aspects that are specific to a given unstudied population. Moreover, by focusing on lifespan non-clinical research, we aim to offer a general synthesis which can in future be informed by insights from clinical groups, rather than subsuming and potentially obscuring the aspects of loneliness which might be unique to them. Whilst primary empirical studies are not themselves extensive sources, with books in particular often offering rich descriptions of loneliness (see, e.g. [ 11 , 46 ]), this research will focus on primary empirical studies of subjective descriptions to offer a manageable level of scope and rigour. As with any systematic review, some studies may also be missing information which would inform the synthesis. Quality appraisal and sensitivity analysis will aim to capture and potentially control for this issue, but it will ultimately be difficult to ascertain how missing information might affect the synthesis.

By providing a thorough overview of how loneliness is experienced, we expect that the findings from the planned review will be informative and useful for researchers, policymakers, and clinicians who work with and for people experiencing loneliness, as well as for these individuals themselves, to better understand this important, prevalent, and often misunderstood phenomenon. Mansfield et al. [ 18 ] have offered an illuminating systematic review covering the conceptual frameworks and models of loneliness included in the existing evidence base (i.e. social, emotional, and existential loneliness). This review will build upon this work by including research with children and adolescents and taking a bottom-up approach similar to grounded theory where the synthesis will remain close to the participants’ subjective descriptions of loneliness experiences within the included studies, rather than reflecting pre-existing themes in the evidence base. As such, this systematic review will offer specific insights into lifespan experiences of loneliness. This synthesis of lived experiences will shed light on the nuances of loneliness which existing definitions and typologies might overlook. It will offer an experience-focused overview of loneliness for people studying and developing measures of this phenomenon. In focusing on qualitative work, the planned review may also identify processes relevant to loneliness which are not expressed by statistical models. In this way, it may also provide a starting point for more nuanced qualitative work with specific populations and circumstances to ascertain components which may be characteristic of certain experiences.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research

Education Resource Information Center

Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation – Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research

International Bibliography of the Social Sciences

Joanna Briggs Institute

Jenny Groarke

Keming Yang

Phoebe McKenna-Plumley

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses – Protocol

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

Review question – Epistemology – Time/Timescale – Resources – Expertise – Audience and purpose – Type of data

Rhiannon Turner

Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type

Department for Digital C, Media and Sport. A connected society: a strategy for tackling loneliness – laying the foundations for change. London; 2018.

Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA. Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychol Aging. 2010;25(2):453–63.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med\. 2010;40(2):218–27.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Lim MH, Rodebaugh TL, Zyphur MJ, Gleeson JF. Loneliness over time: the crucial role of social anxiety. J Abnorm Psychol. 2016;125(5):620–30.

Qualter P, Brown SL, Rotenberg KJ, Vanhalst J, Harris RA, Goossens L, et al. Trajectories of loneliness during childhood and adolescence: predictors and health outcomes. J Adolesc. 2013;36(6):1283–93.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7(7):e1000316.

Hammond C. The surprising truth about loneliness: BBC Future; 2018. Available from: http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20180928-the-surprising-truth-about-loneliness .

Victor CR, Yang K. The prevalence of loneliness among adults: a case study of the United Kingdom. J Psychol. 2012;146(1-2):85–104.